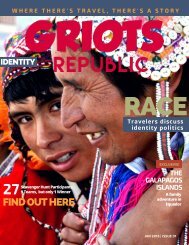

GRIOTS REPUBLIC - AN URBAN BLACK TRAVEL MAG - SEPTEMBER 2016

September's issue is all about GLOBAL FOOD! Black Travel Profiles include Celebrity Chef Ahki, Soul Society's Rondel Holder, Dine Diaspora and Airis The Chef.

September's issue is all about GLOBAL FOOD! Black Travel Profiles include Celebrity Chef Ahki, Soul Society's Rondel Holder, Dine Diaspora and Airis The Chef.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SEED<br />

KEEPERS<br />

NATIVE SEED<br />

CONSERVATION<br />

<strong>BLACK</strong><br />

FOODIE<br />

INTERNATIONAL<br />

CUISINE MEETS<br />

THE <strong>BLACK</strong> LENS<br />

DINE<br />

DIASPORA<br />

ORG<strong>AN</strong>IC<br />

FARMING<br />

THE <strong>BLACK</strong><br />

WWOOF<br />

EXPERIENCE<br />

CHEF<br />

AHKI<br />

HONORING DR. SEBI’S<br />

LEGACY THROUGH FOOD

Welcome to our Global Food issue!<br />

We could have gone sixty different ways with<br />

a food issue, but in true GR style we tried to<br />

bring you as many articles and people reflecting<br />

the varied interests of black travelers<br />

as possible.<br />

From eating at community tables in South<br />

East Asia to beer in Palestine and the dietary<br />

benefits of a traditional African diet,<br />

we’ve covered quite a few continents. We’ve<br />

also snuck in a few fantastic chefs and food<br />

bloggers for you foodie-types. Also, for those<br />

interested in going into the culinary industry,<br />

do not miss Aris The Chef’s honest and<br />

straight forward advice!<br />

Not into food? We’ve still managed to chock<br />

this issue with dope music festivals, travel<br />

conferences, and information on how to<br />

make money while traveling (WWOOF).<br />

As usual, we do hope that you enjoy magazine<br />

and we’d love to hear your feedback.<br />

Visit us at www.GriotsRepublic.com or on<br />

social media and leave us a message!<br />

• Celebrity Chef Ahki<br />

joins us to talk about<br />

the health benefits of<br />

veganism.<br />

• Check out the interview<br />

with Jessica Gordon<br />

Nembhard about<br />

Black Co-Ops.

• If you enjoy everything<br />

about wine from the science<br />

to the taste and<br />

you’re looking for some<br />

girlfriends to travel<br />

and sip with, then absolutely<br />

read the article<br />

on Black Girls Do<br />

Wine and contact them.<br />

• Seed keepers is a concept<br />

that we knew nothing<br />

about until we interviewed<br />

Matika Wilbur<br />

back in January. She<br />

mentioned Sierra Seeds<br />

and the work they are doing<br />

around Native seed<br />

conservation and we’ve<br />

been on the lookout for<br />

their director, Rowen<br />

White, every since. If her<br />

words don’t make you<br />

think twice about your<br />

relationship with your<br />

food, then read it twice!<br />

• Last year, our Editor went<br />

to Oktoberfest in Palestine<br />

and she’s been raving<br />

about Taybeh Beer<br />

ever since. We finally<br />

nailed down an opportunity<br />

to talk to this amazing<br />

family. They’re a very<br />

hardworking and tight<br />

family and their success<br />

is quite inspiring.

OCTOBER<br />

8th & 9th<br />

By Brian Blake<br />

If you like reggae and wine, you will<br />

be sure to love Linganore Winery’s<br />

signature event aptly named the Reggae,<br />

Wine, Music & Art Festival.<br />

Held tri-annually (Spring/Summer/<br />

Fall), this celebration of good vibes will<br />

take place over two fun-filled days on<br />

October 8th and 9th from 10 a.m. to 6<br />

p.m. If the fall edition is anything like<br />

the summer event that Griots Republic<br />

attended on July 16th & 17th, you<br />

are guaranteed a good time minus the<br />

scorching temperatures.<br />

Live reggae music coupled with food

and wine always present a great<br />

time; as the undertone of the bass<br />

guitar to the chords of the piano<br />

and the beat of the drum will always<br />

connect you to the natural<br />

mystic, flowing through the air.<br />

Linganore also provides guests<br />

with complimentary tours and<br />

tastings; learn about the process<br />

of turning a small yet powerful<br />

fruit into a variety of tastes from<br />

merlot (a dry, full bodied red wine)<br />

to dessert wines (sweeter & fruitier).<br />

The wine at Linganore is sweet<br />

and fruitful and has enough bite<br />

for you to relax and enjoy the music.<br />

In addition to the reggae and wine,<br />

there are a variety of vendors to<br />

indulge in a bit of retail therapy.<br />

From arts & crafts, paintings,<br />

clothing, jewelry and good eats;<br />

there is something for everyone.<br />

Remember it doesn’t cost you to<br />

take a look as you may be surprised<br />

what your eyes behold.<br />

The food is delicious and essential<br />

as your body will need a dampening<br />

agent from all the wine you<br />

drink. From jerk chicken to seafood<br />

to barbeque and many offerings<br />

to satisfy a sweet tooth- you<br />

are sure to obtain a belly full!<br />

With that said, if you are in or<br />

around the area or want to plan<br />

a local getaway, then Linganore’s<br />

Fall Reggae Wine Festival is a must.<br />

See you there!

The Nomadness Travel Tribe is well<br />

underway with finalizing plans for their<br />

2nd Annual #NMDN ALTERnative Travel<br />

Conference to be held Saturday, September 24,<br />

<strong>2016</strong>, at Punto Event Space in New York City.<br />

#NMDN is the brainchild of Nomadness Travel<br />

Tribe founder, Evita Turquoise Robinson,<br />

and has been dubbed an ALTERnative Travel<br />

Conference to dispel any ideas that this is just<br />

another travel conference. Rather, #NMDN<br />

is an experience that attendees immerse<br />

themselves into. After recognizing a clear lack<br />

of diversity of all kinds amongst existing travel<br />

conferences and expos, Robinson and her<br />

team sought to integrate a broader definition<br />

and demographic of what the current travel<br />

market looks like. Simply put, Robinson saw<br />

important conversations not being had by<br />

major travel brands and created the space for<br />

these conversations on her own terms. Catering<br />

to more than just the casual vacationer, the<br />

one-day conference brings travelers, nomads,<br />

and aspiring expats alike together to explore<br />

travel on a deeper level within the realms of<br />

international art, music, food, beauty, social<br />

justice, entrepreneurship, and more.<br />

Having successfully sold out last year’s

conference, this year’s theme focuses on getting<br />

“Back to the Future: Of Travel” with a push on<br />

bridging the gap of travel generations in order<br />

to learn from the past while “bracing ourselves<br />

and supporting the movers and shakers of the<br />

travel future.”<br />

#NMDN <strong>2016</strong> features an impressive panelist<br />

of millennials and seasoned travelers who have<br />

established themselves as way makers in their<br />

respective industries like Kellee Edwards, On-Air<br />

Travel Expert for FOX5 San Diego, adventurer,<br />

and pilot.<br />

As is the mission of the conference, panelists<br />

will be speaking on a variety of topics that blend<br />

travel, diversity, and creativity as it relates to<br />

addressing concerns and the current needs<br />

of today’s urban millennial traveler. Whether<br />

you want to learn ways to travel smarter and<br />

safer, or you want first hand perspectives on<br />

living abroad as a person of color in a world<br />

where people are searching for a place where<br />

#BlackLivesMatter, the #NMDN Alternative<br />

Travel Conference will have something for you.<br />

The conference will have panels and workshops<br />

covering various topics such as “Travel 911”,<br />

where panelist will discuss the best ways to<br />

prepare for and deal with emergencies abroad<br />

from the perspectives of medical care providers<br />

and from the first-hand experiences of travelers<br />

that have had emergency situations abroad and<br />

lived to share their story.<br />

Another panel, “LGBTQ Travel” is a much needed<br />

conversation moderated by revolutionary and<br />

anti-oppression trainer YK Hong, that will<br />

address the concerns and nuances of traveling<br />

while lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, and transgender.<br />

The conference will wrap up with a keynote<br />

panel entitled “Life & Lessons” featuring the<br />

travel wisdom of some of Nomadness’ 50+<br />

aged members who have lived, loved, and<br />

traveled.<br />

All ticket purchases and conference<br />

information can be found on the #NMDN<br />

website, www.nmdnconference.com. Follow @<br />

NMDNconference on twitter to stay up to date<br />

on available workshops and featured panelists.<br />

THE P<strong>AN</strong>ELS<br />

Here’s a taste of some of the panels at the<br />

<strong>2016</strong> NMDN conference.<br />

LGBTQ <strong>TRAVEL</strong><br />

In 2015, nomadness facilitated its first LGBTQ<br />

Nomadnessx trip. We learned that there are so<br />

many nuances to traveling while being apart of<br />

this community. Here we are creating an honest<br />

dialogue on traveling while gay, bisexual, and<br />

transgender.<br />

HACKERS<br />

What are all the travel hacks that you need to<br />

know. From where to secretly store your money<br />

on the beach, to using all the credit card points you<br />

have to your advantage.<br />

THE FORUM<br />

A conversation on black lives, both domestic and<br />

abroad - in the aftermath of numerous police<br />

shootings of Black Americans, and the unique<br />

safety concerns of black travelers, we are featuring<br />

this panel as a forum to facilitate an open, nonjudgmental,<br />

necessary dialogue on the state of<br />

black travelers while home and abroad.<br />

LIFE & LESSONS<br />

Travel wisdom from our 50+ aged travelers -<br />

it’s not the age. It’s the energy. Nomadness<br />

reveres the wisdom it has from it’s older<br />

traveling members. This panel is a feel good,<br />

no stone unturned, real life conversation with<br />

our ‘tribe wisdom’ as we call them. This panel<br />

is not to be missed

Nestled at the busy intersection of<br />

Constitution Ave and 14th Street in NW<br />

Washington, D.C., there’s a new neighbor<br />

to the variety of Smithsonian museums waiting<br />

to open its doors.<br />

The National Museum of African American<br />

History & Culture (NMAAHC) will take guests on<br />

a journey throughout the nation’s history and<br />

how it shaped Black culture as we recognize it<br />

today. Congress passed legislation during the<br />

Bush administration to establish the museum in<br />

2003. It was originally slated to open in 2015,<br />

but the dedication was delayed until this year.<br />

The museum features an ‘Oprah Winfrey<br />

Theater’ that will host museum programs, a<br />

robust exhibition from Essence Magazine and<br />

contributions from well-known artists and<br />

celebrities including Michael Jackson, Prince,<br />

Nat King Cole, Quincy Jones, Duke Ellington,<br />

Ray Charles, Paul Robeson and more. Visitors<br />

will also get to see the countless contributions<br />

members of the black community have made to<br />

Hollywood and American film. If it all becomes<br />

too overwhelming, guests can take a break<br />

and gaze out of the museum windows at the<br />

Washington Monument and the Smithsonian<br />

Museum campus from the Concourse level.<br />

The museum’s director, Lonnie Bunch, was<br />

inspired to start the museum by his experiences<br />

as a young black boy in a predominately<br />

white neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey,<br />

the state’s largest city. Bunch spent nearly<br />

11 years traveling the country fundraising for<br />

the museum that will have the largest display<br />

of artifacts and contributions from America’s<br />

Black community. When the museum opens<br />

33,000 items will be on display out of about<br />

37,000 collected so far.<br />

As Bunch observed photographs, pictures and<br />

other types of memorabilia to assemble the<br />

museum’s collection, he says he often compared<br />

his own experiences with the racial anxieties he<br />

felt in his less than diverse neighborhood. In his<br />

reflective moods he would often wonder what it

was like for African Americans to live in America<br />

at that time in history, if they were happy and if<br />

they were treated fairly.<br />

Bunch is also hoping that the nascent museum<br />

will be received fairly by the public but knows<br />

that some of its exhibits will be controversial.<br />

Comedian and actor Bill Cosby will have an<br />

exhibit there without detailing his recent<br />

sexual abuse allegations scandal. The museum<br />

will show highlights of President Obama’s<br />

presidency and chronicle the Black Lives Matter<br />

movement into the country’s sociopolitical<br />

narrative. One of the touchier subjects that’s<br />

sure to cause some visitor reaction is how<br />

the museum treats slavery. Bunch says he<br />

documented the experience in a balanced way<br />

that honors those who’ve made sacrifices, yet<br />

does not exploit the often gruesome institution.<br />

Yet, the museum is grounded by slavery,<br />

literally. Guests start their visit below ground<br />

in an exhibit called “Slavery and Freedom.”<br />

Artifacts include an auction block where for<br />

many, was the start of their journey during the<br />

transatlantic slave trade.<br />

The museum has also published a series of<br />

companion books with some of the exhibits<br />

called “Double Exposure” that’s being sold<br />

online. The visually captivating series highlights<br />

some of the challenges and dynamics of<br />

African-American life through photography<br />

while highlighting some of the most prominent<br />

activists, writers, historians and photographers<br />

in modern history. The photographs span from<br />

portraits taken from the pre-Civil War epoch<br />

to modern digital prints. The images capture<br />

scenes from the religious and oral traditions<br />

emanating from Shiloh Baptist Church in<br />

Washington to the Alabama march from Selma<br />

to Montgomery in 1965. The showcased<br />

photographers captured pieces of history that<br />

shaped so much of American culture.<br />

The NMAAHC is the 19th and newest museum<br />

of the Smithsonian family. It officially opens to<br />

the public on September 24th.

DINE D<br />

PORA

IAS-<br />

Dine Diaspora is a contemporary lifestyle<br />

and events company that creates dynamic<br />

experiences around food, culture, and heritage.<br />

Through intimate gatherings, their<br />

Signature Dinners connect African diaspora<br />

leaders, entrepreneurs, and innovators<br />

to grow their networks with like-minded<br />

peers across various sectors while celebrating<br />

the diverse culinary expressions<br />

of the African Diaspora.<br />

Dine Diaspora also offers a speaker series,<br />

Dish and Sip, that provides a platform for<br />

discussion and insight into the lives, experiences,<br />

and impact of global leaders<br />

while enriching connections through food,<br />

culture, and heritage.<br />

The company also provides corporate<br />

event planning services to various companies.<br />

Whether you are hosting a social<br />

event or your next fundraiser, they will work<br />

with you to develop and execute an event<br />

strategy that is tailored to your needs. For<br />

more information, visit www.DineDiaspora.com<br />

(Bio Taken From Their Website)

Taybeh Brewing Company is a family<br />

owned and operated brewery In Palestine.<br />

Yes, you read that correctly,<br />

Palestine. Taybeh Brewing Company was<br />

created in 1994 in the last Christian village<br />

in the west bank of Palestine. The<br />

founders of the brewery, David Khoury<br />

and Nadim Khoury, were inspired to create<br />

a business in their home village of<br />

Taybeh after living in the United States for<br />

over 20 years. The business they established<br />

is the first brewery in the Middle<br />

East. Their goal was to build and create a<br />

substantial boost to the local economy by<br />

following the German standard of brewing<br />

hand-crafted beers with no preservatives<br />

while creating a nationalistic feeling<br />

of pride in their home land of Palestine. I<br />

had the distinct pleasure of interviewing<br />

one of the trailblazing founders, Nadim<br />

Khoury.<br />

GR: How did the Taybeh Brewing Company<br />

start for you?<br />

NK: I developed a love and interest for<br />

home brewing back in Boston, MA. It was<br />

a hobby that I truly enjoyed and had a passion<br />

for. My brother and I would go back<br />

home to Palestine every year to renew our<br />

Identification and my father wanted us to<br />

come back home permanently. He spoke<br />

about building something here in Palestine<br />

and that was where the idea first<br />

started.<br />

There were no breweries in 1994 when we<br />

started. Not just in Palestine, but nothing<br />

like this in the entire Middle East. We<br />

began brewing and selling dark, amber<br />

and white beers. We also brewed a non-alcoholic<br />

brew for the Muslim population,<br />

since many Muslims don’t drink alcohol<br />

for religious reasons.

The Palestinian Central Bureau<br />

of Statistics estimated that<br />

the Palestinian population of<br />

Muslims makes up approx. 80–<br />

85% (predominantly Sunni).<br />

Consumption of any intoxicants<br />

(specifically, alcoholic beverages)<br />

is strictly forbidden in the Muslim<br />

teachings of the Qur’an.<br />

GR: With all these predominantly religious<br />

factors opposing alcohol consumption,<br />

were you fearfull of the reaction of<br />

other Palestinians?<br />

NK: It wasn’t very easy and we faced many<br />

obstacles, but our goal was always to make<br />

a change. A change in our community, to<br />

build tourism, to build a sustainable business<br />

and to change the world’s perception<br />

of Palestine and its people. People don’t<br />

believe that Taybeh beer, brewed in Palestine,<br />

could be as good or better than other<br />

beers of the world, due to people only seeing<br />

negative images, violence, bombings<br />

and uprisings when the news reports on<br />

Palestine. We are trying to change this and<br />

show the world we live in peace with our<br />

neighbors. We are humans, we have the<br />

right to enjoy life, supply our needs and<br />

celebrate the freedom of Palestine.<br />

GR: To what do you owe the credit or motivation<br />

to do what most people thought<br />

was an impossible undertaking of building<br />

a brewery in Palestine?<br />

NK: I credit my father. He worked in the<br />

travel and tourism industry. In Palestine,<br />

it’s customary for a son to follow the father’s<br />

trade - like if your father was a carpenter<br />

you would become a carpenter to<br />

continue his business and maintain his clients.<br />

When I decided to open a brewery<br />

and brew beer, my father supported me<br />

because in his years in the travel industry,<br />

he had seen business travelers and other<br />

types of tourist partake in drinking at<br />

meetings and for recreation. He saw it as<br />

a way to bring interest and boost tourism<br />

here in Palestine. My father had a strong<br />

work ethic and I run a tight ship because<br />

of his example. I hope my children pass<br />

that on to their families.<br />

GR: There have been a number of breweries<br />

that have been created in your region<br />

and followed the path that you have laid.<br />

How do you feel about these new breweries?<br />

NK: I feel that it is great for our company<br />

and the beer culture of Palestine as<br />

a whole. More consumers are becoming<br />

educated in what beer can be. I support<br />

healthy competition in business and if<br />

people can be successful creating a larger<br />

group of tastemakers and craft beer enthusiasts,<br />

I feel that it can only benefit us<br />

all.<br />

GR: Many of the ingredients common to

eer production are not indigenous to Palestine.<br />

How do you obtain the ingredients<br />

necessary to make Taybeh Beer?<br />

NK: Many of the ingredients that we use<br />

in our beer brewing are imported from<br />

Europe. We only want and use the best<br />

ingredients available to us to create the<br />

best beers possible. We take pride in using<br />

Palestinian wheat and many natural Palestinian<br />

ingredients from the surrounding<br />

areas, which give Taybeh Beer its distinct<br />

flavor and notes.<br />

GR: Taybeh is a family owned and operated<br />

business. How does working closely<br />

with your family differ from working for<br />

someone else?<br />

NK: It can be hard at times, but they care<br />

more about the company because it is truly<br />

ours. I am so very proud of my children.<br />

My daughter, Madees Khoury, is the first<br />

and only female brewer in Palestine and<br />

my son, Canaan Khoury, manages the boutique<br />

winery division of Taybeh. My brother’s<br />

daughter manages our green, energy<br />

efficient hotel which is the first of its kind<br />

in Palestine and we are very proud of it.<br />

We work hard and we work together as a<br />

family.<br />

GR; Why is Taybeh branching into such a<br />

different market like wine production?<br />

NK: The demand for wine is very high and<br />

we answered this demand with creating<br />

the first boutique winery in Palestine. Palestine<br />

is home to 21 different varieties of<br />

grapes that have never been used in mass<br />

wine production, so the decision to start<br />

this market was clear. Building the identity<br />

of Palestine’s wine and beer culture, using<br />

quality ingredients that are natural to our<br />

region, was something that was undeniable<br />

and had to be done.<br />

GR: Taybeh also hosts a large beer festival.<br />

Why did you bring Oktoberfest to Palestine?<br />

NK: Oktoberfest is celebrated all over the<br />

world, so why not in Palestine? I worked<br />

with my brother who was the mayor of Ty-

ee, to put together a true Oktoberfest for<br />

the people to enjoy and celebrate beer and<br />

beer culture.<br />

Two years ago we had to cancel due to a<br />

number of issues, but the festival is back<br />

and bigger than ever. We have a goal and<br />

will not be deterred from it. Oktoberfest<br />

is the #1 festival in Palestine. This year<br />

the festival will be held September 24th<br />

through the 25th, but will still be an amazing<br />

Oktoberfest.<br />

GR: What are the core goals of Taybeh as<br />

a brand?<br />

NK: To continue to increase tourism to Palestine<br />

and the Taybeh area. To continue to<br />

educate consumers worldwide. To make<br />

great beer in many varieties like our very<br />

popular brew created with oranges from<br />

the world’s oldest city, Jericho. To ultimately<br />

share products all over for the world to<br />

enjoy.<br />

GR: What is something you would like the<br />

world to know or take away from Taybeh,<br />

whether it be drinking one of your beers<br />

or visiting your location?<br />

NK: Palestinians are normal people. We<br />

make our own way. We make good beer. We<br />

celebrate our freedom and share peace in<br />

developing the entire country.<br />

GR: What’s next for Taybeh Brewing?<br />

NK: We are enthusiastic to continue creating<br />

quality products that represent Palestine<br />

and its people in a positive manner. We<br />

are looking into opening Palestine’s first liquor<br />

distillery, adding to the Taybeh portfolio<br />

and producing many different types<br />

of spirts like vodka, rum and whiskey to<br />

name a few.<br />

Taybeh Brewing is an exceptional company.<br />

The fine quality of beer and wine that<br />

they create is something that should not<br />

be overlooked. It is definitely a must try<br />

for the novice enthusiast to connoisseurs<br />

alike. The only thing that can over shadow<br />

the quality of the extensive line of Taybeh<br />

products they create, is the true emotional<br />

connection and philanthropic drive they<br />

have to do better and build more, leaving<br />

a lasting legacy for the people of Palestine<br />

and the world.<br />

For more information about the Brewery,<br />

check out their website at taybehbeer.<br />

com.<br />

Bruce “Blue” Rivera, The Urban Mixologist,<br />

is an accomplished mixologist with over<br />

16 years of bartending, wine and spirits<br />

experience. Boasting an impressive resume<br />

that spans across 12 countries with many<br />

award winning cocktail recipes to his credit,<br />

Bruce “Blue” Rivera teaches the history and<br />

cultural application of bartending and has<br />

been featured on Spike TV’s Bar Rescue and<br />

the Wendy Williams Show, to name a few.<br />

To learn more about The Urban Mixologist<br />

check out www.TheUrbanMixologist.com

As a teenager, Rowen White accidentally<br />

stumbled onto a job that would light a<br />

fire in her powerful enough to brighten<br />

any room she stepped into.<br />

On an organic farm at 17, she was shocked to<br />

learn that heirloom tomatoes came in multiple<br />

varieties; she found it even more profound<br />

that each variety could be traced to a particular<br />

tribe of people, a lineage of caretakers,<br />

and the stories of deep relationships between<br />

these seed keepers and the Earth over generations.<br />

Today, Rowen is the Director and Founder of<br />

Sierra Seeds where she focuses on reviving<br />

indigenous agricultural practices among communities<br />

affected by long histories of displacement,<br />

colonization, and forced acculturation.<br />

“Every bite we eat traces back to a seed.” You<br />

might be familiar with the term ‘farm to table’,<br />

but Rowen is dedicating her life’s work to<br />

rediscovering the journeys of seed(s) to table.<br />

Cultivating seeds requires able bodied hands,<br />

a deep knowledge of what conditions are<br />

needed to optimally grow the plant, and then<br />

a tender tilling and gathering process before<br />

the food is ready for preparation and consumption.<br />

Cultivating foods is not easy even<br />

with the industrial agricultural methods of<br />

our time. For Rowen, to know the ways her<br />

food comes to be is to know her people. “People<br />

from all over descended from people who<br />

were seed keepers at some point. Seeds are<br />

an intimate part of everyday life.”<br />

Growing up, her parents bought food from the<br />

grocery store like everyone else on the reservation<br />

where she grew up. With no awareness<br />

about where food came from, nor an understanding<br />

of the ways in which food and agricultural<br />

traditions embodied the wisdom of<br />

her people, Rowen was aggrieved to find she<br />

was a Mohawk woman without a connection<br />

to this “cultural bundle of knowledge” as she<br />

called it.<br />

Discovering these foodways for herself and<br />

then creating immersive educational pro-

gramming for others to do the same is one<br />

way that Sierra Seeds is helping to accelerate<br />

the movement for food sovereignty across Indian<br />

country.<br />

By reclaiming ancestral ways of connecting<br />

with food, Mother Earth, and community, Rowen’s<br />

work is a kind of radical protest against<br />

generations of whitewashing that have separated<br />

many Native American communities<br />

from the ways of their ancestors. “When you<br />

consider what’s happening across the globe<br />

with multi-national corporations and patenting,<br />

planting and growing your own seed is a<br />

form of activism.” She’s referring to the industrialization<br />

of our entire food system, including<br />

the patenting of genetically modified<br />

seed varieties that farmers all over the world<br />

have taken to cultivating and subsequently<br />

abandoning organic and naturally occurring<br />

varieties.<br />

Some of these varieties have cultural and spiritual<br />

significance to indigenous people like<br />

Rowen’s who utilize several types of corn for<br />

different ceremonies and rituals for example.<br />

“To many indigenous communities, seeds are<br />

a relative. Certain corn for certain ceremonies.<br />

If we lose them and the ability to steward and<br />

care for them, we lose part of ourselves.” By<br />

conserving various seed varieties and continuing<br />

to harvest them outside of the industrial<br />

food system, tribal communities can ensure<br />

the survival of crops that play a central role in<br />

their lives.<br />

“Every seed you plant is a tiny prayer of love,<br />

action, and hope for the future.” Rowen speaks<br />

about the relationship between humans and<br />

the places we inhabit with such compelling<br />

depth and seriousness that you are likely to<br />

ponder about your own ancestors’ ways of relating<br />

to food and the life-source that is Earth.<br />

Rowen is assertive in her conviction that today’s<br />

seeds hold the wisdom of the past, of

the struggle for growth, and the gift of life.<br />

To her, seeds represent a profound and resilient<br />

hope. In a world of war, oppression, and<br />

Trump, gardening is both a coping mechanism<br />

and an act of resilience. “It is a way to connect<br />

with the benevolence of Mother Earth who is<br />

always giving to us time and time again.”<br />

It is indeed remarkable that indigenous communities<br />

all over the world have been cultivating<br />

food on the same lands as their ancestors,<br />

utilizing methods passed down for generations.<br />

This sustained stewardship of natural<br />

resources over time requires resilience in the<br />

face of shifting weather and climate conditions.<br />

“The wisdom those traditional communities<br />

have to offer us about cultivating in climate<br />

change is a gift to the planet in the face<br />

of extreme weather shift. We’re going to need<br />

to look to the indigenous communities of the<br />

world.”<br />

Rowen is currently writing a book about her<br />

journey to discover the seed songs of her people.<br />

Her story is not unlike many others who<br />

have ever wondered about the ways and traditions<br />

of our ancestors. For many Americans of<br />

color, we would not know where to begin the<br />

journey of finding answers. To that she would<br />

advise that you begin with thinking about the<br />

foods your ancestors would have eaten. Think<br />

about the pervasive health problems we have<br />

in this country and reflect on how your diet is<br />

a departure from what was normal to eat hundreds<br />

of years ago.<br />

Think about where you live and the access you<br />

have or lack to staple ancestral foods. Find opportunities<br />

to connect with the source of your<br />

food as it will undoubtedly give you a deeper<br />

appreciation for what it took for that food to<br />

arrive on your plate. And finally, when you’re<br />

short on hope and inspiration, find time to<br />

plant and be among the abundant gifts of life<br />

sprouting from the ground all around you.

Tiffany Em is a trained dancer<br />

currently studying international<br />

urban planning and development<br />

at the Massachusetts Institute<br />

of Technology. To combine her<br />

love for travel, culture, and social<br />

justice she began writing about<br />

urban development, curiosity, and<br />

tourism on her personal blog www.<br />

theroadlessinquired.com. She<br />

hopes to one-day work with artists,<br />

businesses, and local residents<br />

to develop sustainable tourism<br />

enterprises around the world, but<br />

especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The idea that you can dig a hole in<br />

the earth and make it to the other<br />

side has been theorized by many,<br />

but what if you found out that that was<br />

actually possible? No, you can’t tunnel<br />

your way to your destination, but you<br />

can dig, pull weeds, sow seeds, plant,<br />

garden, and more in exchange for a<br />

place to stay, meals, and a knowledgeable<br />

guide to all of the best kept secrets<br />

in your dream travel destination.<br />

This was possible for Brie Johnson,<br />

who was able to work and live in three<br />

countries through her involvement in a<br />

program called, “World Wide Opportunities<br />

On Organic Farms” also known<br />

as WWOOF. The organization which<br />

was originally called “Working Weekends<br />

On Organic Farms,” was started<br />

in 1971 by Sue Coppard, a secretary<br />

in London who was looking for a way<br />

to see the countryside and participate<br />

in the organic movement. She was able<br />

to find a farm willing to host her in<br />

exchange for labor. Soon, the organic<br />

farmers became interested in the concept<br />

of providing accommodations to<br />

others in exchange for a few hours of<br />

work during their stay.<br />

The organization has grown into farmers<br />

in several countries all over the<br />

world. WWOOF allows for farmers,<br />

and perspective volunteers (WWOOFers)<br />

to connect. The length of a volunteer’s<br />

stay on a farm is determined<br />

by the volunteer and the farmer, and<br />

can last a few days or several months.<br />

Though the cost of living is provided<br />

by the host, volunteers are responsible<br />

for a small membership fee, their<br />

visas as needed, and travel expenses<br />

to and from the host country. Many,<br />

consider it a small price to pay for the<br />

experience, the chance to learn new<br />

skills, and be of assistance to those<br />

who are committed to producing organic<br />

foods. In addition to traditional<br />

farms, WWOOFers can also choose to<br />

volunteer at locations that make wine,<br />

cheese, and bread.

Brie’s first WWOOFing experience allowed<br />

her to assist organic farmers in Japan. Her<br />

decision to become a WWOOFer came from<br />

her interest in being more fluent in Japanese.<br />

The icing on the cake was that she<br />

would be able to make a positive impact on<br />

the country while immersing herself in the<br />

culture. After three months in Japan volunteering<br />

on a rice farm, a strawberry farm,<br />

and a bathhouse, Brie was able to communicate<br />

with Japanese natives without the help<br />

of a translator.<br />

After Japan, Brie spent time WWOOFing on<br />

a traditional farm for three weeks in France,<br />

and a garden for two weeks in a temple in<br />

India. In France, her tasks included tending<br />

to the animals. She milked cows, collected<br />

eggs, groomed the horses, and “chased<br />

down chickens.” In India, Brie worked in a<br />

small garden that was used to support the<br />

hosts, the temple, and was also a source for<br />

their personal food. Her host family helped<br />

her to turn her self-described “black thumb,”<br />

a tad bit greener.<br />

Brie returned back to the states after volunteering<br />

with more than just a firmer grasp<br />

on a language she was interested in. Her experience<br />

allowed for growth in both her personality,<br />

and her palate and cooking skills.<br />

As a “terrible cook,” she made a conscious<br />

effort to learn her way around the kitchen.<br />

Her host in India made it a personal mission<br />

to teach her how to cook in order to “get a<br />

husband.” Of course she was happy for the<br />

lessons for the purpose of being able to feed<br />

herself better home cooked meals, but she<br />

now proudly lists on her dating profile that

she can cook. Her skills came in handy on<br />

a recent date, though according to Brie, the<br />

Indian spices may have been a bit much for<br />

him.<br />

The opportunity to grow her own food<br />

changed her eating habits and naturally, her<br />

shopping habits as well. Brie now frequents<br />

farmer’s markets for her food, only visiting<br />

grocery stores for items she can’t find at the<br />

market. An international market she loves<br />

to visit, allows her to continue to make the<br />

foods she grew to love abroad, which include<br />

almost every variation of rice due to her time<br />

in Japan, and spicy food recipes she learned<br />

in India. “You learn the impact of shopping<br />

with smaller farmers as most of them are<br />

struggling and being pushed out by bigger<br />

farms that may use other unknown methods<br />

to grow their food.” She goes on to say, “It<br />

makes me feel good knowing that I’m buying<br />

food from people who feed the same things<br />

to their families.”<br />

She recalled that her own experience accompanying<br />

her host in India to the farmer’s<br />

market to sell the extra vegetables they<br />

grew at the temple, helped her understand<br />

the industry, but also helped her to understand<br />

more about herself. “It was quite competitive.<br />

We had to get in people’s faces in<br />

order for them to buy the food, which was<br />

the opposite of my personality.” Also, being<br />

an African American in another country with<br />

a “curly afro” meant that she couldn’t necessarily<br />

hide as she could do more easily at<br />

home. In many of the small areas where she<br />

stayed the people have not met many people<br />

who looked like her. Not being able to hide<br />

helped her to assert herself more at home.

Though WWOOFing allows travelers to<br />

stay in non-traditional spaces while<br />

they visit other countries, it is not<br />

to be confused with Airbnb or similar<br />

companies. As Brie explains, “If<br />

you are looking to get into it, make<br />

sure your letter to prospective hosts<br />

describes who you are, your skills,<br />

highlights why you want to WWOOF,<br />

and states that you are a hard worker.”<br />

Brie goes on to stress that “they<br />

are looking for someone who is hardworking,<br />

and not just looking for a vacation.”<br />

WWOOFing is ideal for those that<br />

would like to become a part of the<br />

culture in the countries they visit.<br />

They can literally get their hands<br />

dirty, and get knee deep into the<br />

foundation of each land they choose<br />

to visit. For foodies, the opportunity<br />

to help cultivate food takes the term<br />

“organic food” to another level. Brie’s<br />

future plans to WWOOF may include<br />

visits to New Zealand, Australia, and<br />

some countries in Africa including<br />

Cameroon.<br />

Also, learning how to communicate in places<br />

where she spoke little of the language<br />

helped her to be able to better express her<br />

needs.<br />

To get more information on WWOOFing,<br />

visit www.wwoof.net and follow them on<br />

Instagram at @wwoof.<br />

Simone Waugh is a writer prone to wanderlust.<br />

A city girl with Brooklyn in her<br />

heart and Paris on the brain. Crossing<br />

potholes, puddles, and ponds while planning<br />

to cross more oceans. You can find<br />

her riding shotgun on frequent road<br />

trips ignoring the GPS and hogging the<br />

radio. Follow her adventures across the<br />

keyboard and the eventually the world<br />

on Instagram and Twitter @MoniWaugh.

“Chef Ahki”, CEO of Delicious Indigenous<br />

Foods is a celebrity chef, natural foods activist<br />

and nutritional counselor. Raised by four<br />

generations of medicine women in her native<br />

Oklahoma, Ahki uses seasonal, organic,<br />

fresh (non-hybrid) fruits and vegetables<br />

to create living, healthy recipes designed to<br />

heal bodies and enhance lives. From vegans<br />

to health nuts and budget moms to foodies,<br />

her message of non-hybrid and electric<br />

foods is a way of life.<br />

Her brand is the new voice of the young generation<br />

who is f’n pissed at big agricultue<br />

and its mono-cropping frenzy, science lab<br />

food and GMO corporate food tyranny all<br />

resulting in an obese, sick and nearly dead<br />

generation of parents who outlive their own<br />

children.<br />

Chef Ahki’s latest cook book, “Electric!,<br />

A Modern Guide to Non-Hybrid and Wild<br />

Foods” is why celebrities like Lenny Kravitz,<br />

Bradley Cooper, Curtis Martin, COMMON,<br />

Waka Flocka, and Lee Daniels fell in love<br />

with Ahki’s cooking. For more information<br />

visit www.gochefahki.com.<br />

(Bio taken from her website and Facebook<br />

page)

By Lincoln Park Coast Cultural District

Lincoln Park Music Festival’s organizer,<br />

world traveler, and “house-head”<br />

extraordinaire Anthony Smith makes<br />

sure it is no secret that Lincoln Park is<br />

the mother of all music festivals in New<br />

Jersey and it has spawned other festivals<br />

not only across Jersey but, across the<br />

world.<br />

Having worked in the trenches of the<br />

then budding Essence Music Festival<br />

years ago, Anthony took his learnings and<br />

experience and began to formulate a plan<br />

not only to bring the music to a revitalized<br />

Newark, New Jersey crowd, but to create<br />

an event that would drive people to travel<br />

from across the globe to visit, stay, shop<br />

and of course party in the city where he<br />

grew up, went to school, partied and still<br />

calls home.<br />

Anthony cant help but take pride in seeing<br />

his model emulated, even duplicated in<br />

sister events in Mexico and Florida (and<br />

even Europe).There is the annual Miami<br />

House Music Festival, which has grown to<br />

a week-long event, and now there is the<br />

ever growing Mi Casa in Playa del Carmen.<br />

He knows he is on to something and also<br />

knows the best is yet to come.<br />

Funny enough, the very first Lincoln Park<br />

Music Festival looked nothing like it does<br />

today. In 2006, Newark hosted it’s first Hip<br />

Hop/Punk Rock Festival in Lincoln Park .<br />

Today, it has become a three-day music<br />

festival consisting of jazz, gospel, and<br />

house. While a fan of all genres of music,

The history of<br />

Lincoln Park Music<br />

Festival’s iconic<br />

House Music Day<br />

[...] cannot be told<br />

without talking about<br />

the lendenary Club<br />

Zanzibar.<br />

house is where his heart is. Of the average<br />

60,000 attendees that congregate over a<br />

3-day weekend, nearly half descend on<br />

the South end of downtown’s Newark’s<br />

Broad Street for House Music Day.<br />

The history of Lincoln Park Music<br />

Festival’s iconic House Music Day,<br />

typically held on the last Saturday in July,<br />

cannot be told without talking about the<br />

lendenary Club Zanzibar. Most recently,<br />

at a pop up photography exhibit entitled<br />

“Lincoln Park Music Festival: Decade<br />

One” at City Without Walls Gallery, it was<br />

imperative that a section was dedicated<br />

to this iconic venue for house music.<br />

In the 2nd year, the festival opened with<br />

a reception and photo exhibition entitled<br />

“Music Speaks: A Celebration of Spirit and<br />

Dance”, which documented performances<br />

featured at Newark’s legendary Club<br />

Zanzibar. Photographs included Phyllis

Hyman, Eddie Kendrick’s, Grace Jones<br />

with Loleatta Holloway, Sylvester and<br />

numerous others photographed by<br />

Vincent Bryant, author of Unforgiveable<br />

Moments - A Journey Through the House:<br />

Photo Memoirs of Club Zanzibar.<br />

“It was great to collaborate with Lincoln<br />

Park Coast Cultural District on this<br />

great exhibit which accurately depicts<br />

the origins of House Music Day. It<br />

was without question that we added a<br />

section entitled ‘Where It All Began: Club<br />

Zanzibar’. We are always excited to bring<br />

more art and culture to the community,<br />

and be historically accurate.” states Malik<br />

Whitaker, Interim Gallery Director at City<br />

Without Walls.<br />

Club Zanzibar, which closed in the early<br />

90’s, was known for their impeccable<br />

Richard Long sound system and as a<br />

place where the who’s who in the NJ scene<br />

and metropolitan area would flock to hear<br />

the latest sounds and groundbreaking<br />

artists in an unplugged atmosphere. The<br />

luminaries who attended the club each<br />

week were social change agents using the<br />

mediums of music, art and fashion to<br />

shape popular culture.<br />

Dubbed the “New Jersey version” or<br />

“sister club” to NYC’s Paradise Garage<br />

where the resident and legendary DJ<br />

Larry Levan played and was featured on<br />

selected Wednesday nights, it had one of<br />

the best DJ rosters in the region including<br />

DJ Tony Humphries, Larry Patterson,<br />

T-Scott, Hippie Torrales, Françios K. and<br />

more. The pulse of Club Zanzibar runs

straight into Lincoln Park with many of<br />

the DJs, performers, record producers<br />

and attendees who bless the Lincoln Park<br />

Music Festival’s outdoor sanctuary on<br />

House Day.<br />

In fact, Miles Berger, the former owner of<br />

Club Zanzibar, is still a supporter of LPMF<br />

as was the late Shelton Hayes, former<br />

manager at the club and the original host<br />

of the House Music day in Lincoln Park.<br />

There are so many griots still around<br />

like Larky Rucker, Carolyn Byrd, Abigail<br />

Adams, Gerald T, Merlon Bob and Darryl<br />

Rochester, to name a few, who can share<br />

their experience of this incredible time in<br />

the history of Newark. This is just a snap<br />

shot of the evolving rich story that helped<br />

shape and mold the culture of Newark<br />

today.<br />

The main stage on Festival Saturday<br />

has become the “Holy Mecca” for house<br />

music. With so many DJs clamoring to<br />

rock the 30,000+ crowd, festival executive<br />

producer Anthony Smith says its makes<br />

decisions very difficult.<br />

“We look to book local, regional and<br />

internationally known artists and DJs<br />

who are a direct reflection of the artistry<br />

that graced the stage and played at

the club during its tenure as an iconic,<br />

transformative place that launched many<br />

careers in music, fashion and the arts,”<br />

states Smith.<br />

Additionally, the legendary Lincoln Park<br />

Music Festival House Music Day has been<br />

captured in the documentary “Hands To<br />

The Sky” by Domingo Canate, which is a<br />

film about the DJs, musicians, fans and<br />

feelings inspired by outdoor house music<br />

dance parties.<br />

“With so many looking at our festival and<br />

House Day as great content, LPCCD is<br />

taking the lead and will be producing its<br />

own documentary project that will capture<br />

not only House Music Day, but the entire<br />

festival to include jazz, gospel, hip-hop<br />

and the history of Lincoln Park within the<br />

context of Newark, New Jersey’s history,”<br />

states Smith.<br />

“Moreover, we will use our now iconic<br />

stage as a vehicle to showcase artists,<br />

DJs and live musicians that represent the<br />

entire African Diaspora and this creative<br />

placemaking tool to shape the historical<br />

Lincoln Park area and the future of arts<br />

and culture in Newark.”

We daresay that adventure and not variety<br />

is the spice of life. In other words,<br />

adventure; that feeling of doing the<br />

unusual and the daring, is the special ingredient<br />

with the potential to enrich our overall<br />

quality of life. Adventure is to life what spice<br />

is to food.<br />

The willingness to experience life’s adventures<br />

does not always translate into openness towards<br />

trying new foods. There are people who<br />

would happily go bungee jumping but whose<br />

culinary experiences remain restricted to the<br />

safety of what they are used to. There is one<br />

potential solution to this unenthusiastic attitude<br />

towards food adventurism. Spices! Spices<br />

have the ability to open the mind (as well<br />

as the palate of course) to new culinary experiences.<br />

In a sense, learning to use spices (fresh or<br />

dried) in cooking helps to challenge and expand<br />

our cultural boundaries while providing<br />

a richer culinary experience. A savory meal of<br />

pulao rice cooked with cinnamon sticks, cumin,<br />

cloves, and black cardamom will transport<br />

even the most hesitant to the vast tea plantations<br />

of Nuwara Eliya or the windy beaches of<br />

Negombo, Sri Lanka.<br />

The ability of spices to extend and expand cultural<br />

and culinary boundaries dates back to<br />

the origins of the spice trade itself. The global<br />

spice trade was once a backdrop for many<br />

historical encounters including the revelation<br />

of many ancient civilizations to Europeans by<br />

Portuguese explorers such as Vasco da Gama<br />

and Ferdinand Magellan. At different points in<br />

history, the utility of spices for flavouring, food<br />

preservation, medicine and fashion increased<br />

their commodity value beyond that of gold.<br />

From the overland Silk Road to the Ocean Spice<br />

Trade routes, the struggle for their control was<br />

often a key driver for changes in the balance in<br />

world trade and a factor in the establishment<br />

and decimation of empires. It was once said<br />

that “He who is lord of Malacca (an ancient<br />

Malaysian spice trade hub) has his hand on<br />

the throat of Venice.”

With many of the world’s most famous spices<br />

long associated with nations and territories<br />

around Africa, Asia and the Middle East, the<br />

very mention of spices conjures the image of<br />

the exotic. For example Zanzibar, an island<br />

state off the coast of East Africa, was once the<br />

world’s leading producer of cloves. Other examples<br />

include nutmeg (Banda Islands, Indonesia),<br />

saffron (Iran) and black pepper (Malabar,<br />

South India).<br />

There are many islands in the world that bear<br />

the title ‘Spice Island’. Of particular interest<br />

is Sri Lanka. Until recently, Sri Lanka was little<br />

more than a transit stop for travellers to the luxurious<br />

islands of the Maldives. Formerly known<br />

as Ceylon and located in South Asia, this Indian<br />

Ocean island nation has for many generations<br />

lived in the shadow of India, her economically<br />

stronger, north westerly neighbor.<br />

Now peaceful, after emerging from a thirty year<br />

civil war that ended in 2009, the government<br />

of Sri Lanka is looking to rebuild and modernize<br />

the economy. However, with technology,<br />

tourism and large infrastructure development<br />

projects being the main economic policy focus<br />

of the current government in Colombo, Sri<br />

Lanka’s spice industry, the tenth largest in the<br />

world, has somewhat taken a backseat.<br />

Notwithstanding, Sri Lanka remains a significant<br />

contributor to the global spice market.<br />

Her rich soil and agreeable climate allow spices<br />

such as cinnamon, pepper, cloves, cardamoms,<br />

nutmeg, mace and vanilla to thrive across the<br />

island. According to the Sri Lanka Export Development<br />

Board, as of <strong>2016</strong>, approximately<br />

56% of Sri Lankan agricultural exports consist<br />

of spices with cinnamon being the largest.<br />

Regardless of the debatable contribution of<br />

spices to Sri Lanka’s export economy, the more<br />

significant discussion surrounds their impact<br />

to Sri Lankan cuisine and food adventurism.<br />

Apart from the surfing, wildlife and history, no<br />

visit to Sri Lanka is complete without a visit to<br />

a local spice farm. As she rebuilds her economy,<br />

Sri Lanka is proving to be the place where<br />

food and adventure collide to provide a sensory<br />

experience.

Sri Lankan food itself consists of staples such<br />

as curry powder, rice, rice flour, flatbreads and<br />

coconut milk and draws influences from Sri<br />

Lanka’s historical South Indian, Portuguese,<br />

Dutch, Arabic and British interactions. Compared<br />

to the more globally famous North Indian<br />

cuisine, Sri Lankan cuisine is lighter and<br />

combines complex yet complementary flavors<br />

thanks to the generous use of herbs and spices.<br />

British author, traveller and Chef Jon Lewin in<br />

his extraordinary book titled: The Locals Cookbook,<br />

features vibrant recipes which he learned<br />

and developed during his extensive travels<br />

across Sri Lanka. He says that at first, he found<br />

the sheer amount of spices in the dishes to be<br />

an assault on the senses but soon, his taste<br />

buds adapted. That process of adaptation<br />

birthed his love affair with Sri Lankan cuisine, a<br />

passion exemplified in his do it yourself, twelve<br />

spice roasted curry powder recipe. This recipe<br />

is an adventurous and hedonistic mix which<br />

includes ground coriander, cumin, fennel, fenugreek,<br />

cardamom, mustard, peppercorns,<br />

cloves, cinnamon, chillies, dried curry leaves<br />

and lemongrass!<br />

When it comes to food, our tastes and preferences<br />

are shaped by what we know and what<br />

society conditions us to accept as ‘normal’.<br />

However, true adventurers constantly test their<br />

limits. Spices provide a platform for creative<br />

expression through food. In the process, our<br />

senses are applied and indulged, and instinct<br />

is called upon.<br />

Perhaps through spices and food adventurism,<br />

we can not only build bridges between cultures<br />

but also push our self imposed limits and in the<br />

process, add variety to our lives. Indeed what<br />

would life be without adventure, and what would<br />

food be without spice?

Eulanda & Omo Osagiede are London<br />

based freelance writers, photographers<br />

and content creators. They run the UK<br />

award-winning travel, food, and lifestyle<br />

blog HDYTI (Hey! Dip your toes in).<br />

Their life experience combines careers<br />

in technology, education and dance with<br />

their personal experience of living and<br />

working across three continents: Africa,<br />

America and Europe. In their spare<br />

time, they enjoy spending time with<br />

family and feeding their curiosity with<br />

culture, music, art and soul food.

Seeing the headlines demonize<br />

‘soul food,’ I am on a mission<br />

that reclaims the health and<br />

spirit of our culture of the ‘original<br />

soul food’, which is the African heritage<br />

diet. The western or standard<br />

American diet has failed the African<br />

diaspora community resulting in diet-related<br />

diseases and premature<br />

death, which is now robbing our youth<br />

of vitality. For example, the U. S. Office<br />

of Minority Health reports the death<br />

rate for African Americans was higher<br />

than Whites for diet-related diseases<br />

in 2009. Heart disease over homicide<br />

is the number one killer of African<br />

American women. Oldways Preservation<br />

Trust reports people live better<br />

with traditional foods and culture.<br />

By growing up in an African diasporan<br />

household, I recognized that the<br />

African American community, like its<br />

food, is not monolithic. I met a woman<br />

from Cameroon who shared how a<br />

caucasian dietitian didn’t know how<br />

to educate her grandmother on how<br />

to modify her African foods to become<br />

compliant with a diabetic diet. That’s<br />

why since 2012 NativSol has offered<br />

community based nutrition and cooking<br />

classes, Pan African catering, lectures<br />

and workshops in America and<br />

Africa for more than 2,000 people.<br />

Since taking the African Ancestry DNA<br />

test in 2010, I began my journey to<br />

trace my African heritage through<br />

food and travel. This summer I returned<br />

from Nigeria where I lectured<br />

and learned about my Fulani heritage<br />

and its foodways of northern Nigeria.<br />

The foods I share, such as the baobab<br />

and hibiscus, can be found in northern<br />

Nigeria and are part of contemporary<br />

life in Africa.

HIBISCUS<br />

Travel to any open-air market from west,<br />

north to east Africa and you are sure to<br />

find dried or fresh roselle (a hibiscus<br />

flower) ready to prepare a classic tropical<br />

sipping sensation, hibiscus tea.<br />

Quenching the thirst of many Africans,<br />

the West African native roselle is a show<br />

stopper compared to the market’s newcomer—soda.<br />

range of flavors from garlic, ginger to<br />

cloves to this healing elixir.<br />

Beyond beverage brewing, the flower,<br />

its stems and leaves are used for salad<br />

making among Nigeria’s Hausa community.<br />

Also in some parts of Africa,<br />

the oil-containing seeds are eaten.<br />

In Nigeria, it’s called Zobo. In Ghana, it’s<br />

called Sobolo. In the Gambia, it’s called<br />

wanjo. It’s known as Dabileni in Mali. In<br />

Cote d’Ivoire, it’s known as Bissap and<br />

in Egypt and Sudan, it’s known as Karkade<br />

and in the Caribbean, it’s known as<br />

Sorrel or agua de flor de Jamaica. How<br />

did the roselle (known as sorrel in the<br />

Caribbean) get to the Caribbean and<br />

South America? Historians believe the<br />

seeds may have been brought by slaves<br />

taken from Africa.<br />

Called by many names, this delicious<br />

drink from the ruby red roselle’s color<br />

gives a clue to the heart health benefit<br />

it shares with other naturally red plants.<br />

Drinking hibiscus tea daily has been<br />

found to lower blood pressure in people<br />

with hypertension, according to a U.S.<br />

research study. The beautiful dark red<br />

colorful hibiscus is packed with anthocyanins<br />

(a type of flavonoid) which have<br />

many health benefits like fighting colds<br />

and flus.<br />

Packed with the cancer-fighting antioxidants,<br />

Vitamin C and other minerals,<br />

the hibiscus drink can be sweetened<br />

naturally with fruits like pineapple, watermelon<br />

or strawberries. Want to make<br />

a symphony in your mouth? Then add a<br />

Whether it’s a hot day in Cairo or a chill<br />

day in Accra, you can drink hibiscus tea<br />

hot or cold. Unlike hibiscus, dehydrating<br />

soft drinks have no nutritional value<br />

to offer while robbing calcium from<br />

your bones. So in countries already<br />

facing malnutrition, soft drinks are the<br />

last thing to reach for in hydrating your<br />

body.

BABA<br />

BAOBAB TREE<br />

Calling Africa its native home, the baobab<br />

is the ‘baba’ of trees giving life to<br />

all and can be found in 32 African countries.<br />

Like an old healer, the baobab<br />

is at the heart of traditional remedies.<br />

Also it can live long in age, up to 5,000<br />

years; so we call it ‘baba.’<br />

From South Africa, Madagascar, Nigeria,<br />

to Burkina Faso, the sacred tree<br />

stretches across Africa’s sub-Saharan<br />

arid savanna. Serving as a meeting<br />

place in villages, it holds a spiritual<br />

reverence among the people; therefore<br />

many people and animals choose to<br />

live near the tree. Beyond that, did you<br />

know the baobab tree is a high quality<br />

source of nutrition?<br />

The raw ‘monkey bread fruit’ of the baobab<br />

is incredibly good for you and is an<br />

excellent source of vitamin C, calcium,<br />

potassium, thiamin, fiber and vitamin<br />

B6. The fruit has one of the highest antioxidant<br />

capacities of any in the world,<br />

with more than double the antioxidants<br />

per gram of goji berries and more than<br />

blueberries and pomegranates combined.<br />

The many uses of baobab range from<br />

sprinkling it in your oatmeal and yogurt<br />

to all manner of tasty treats. From<br />

sauces, smoothies to seltzers, baobab<br />

is the go-to super fruit for flavor filled<br />

nutrition. Want a little flavor to your<br />

sparkling water? Swap out sugar for<br />

a teaspoon of baobab powder in your<br />

next cup.<br />

No lemon or vinegar? That’s fine, we got<br />

baobab. For tangy flavor in your sauces,<br />

a scoop of baobab better adds a citrus<br />

kick. For smoothie season, blend mango<br />

and pineapple with two scoops of<br />

baobab powder with coconut water.<br />

Honored as the 2014 “National Geographic<br />

Traveler Magazine’s Traveler of the Year” and<br />

“Nutrition Hero” by Food & Nutrition Magazine,<br />

Tambra Raye Stevenson is an inspiring speaker<br />

and nutrition justice advocate leading a new<br />

initiative called W<strong>AN</strong>DA: Women Advancing<br />

Nutrition Dietetics and Agriculture to inspire<br />

a new generation of women and girls to lead<br />

the farm to fork movement in Africa and<br />

the Diaspora. Before W<strong>AN</strong>DA, she founded<br />

NativSol Kitchen with a mission of reclaiming<br />

our health through African heritage foods.<br />

Learn more at nativsol.com and iamwanda.<br />

org. Facebook\Twitter: @iamwandaorg @<br />

nativsol @tambraraye

SOUL SOC<br />

A marketing executive who has worked<br />

at notable media companies for over<br />

10 years, such as Pandora Radio, ES-<br />

SENCE Magazine, Complex, VIBE and<br />

AllHipHop.com.<br />

Rondel is currently Co-CEO of Creative<br />

Genius Branding, a boutique marketing<br />

and branding firm that specializes<br />

in non-profit, small business and entertainment<br />

clients.<br />

Business and pleasure have provided<br />

Rondel the opportunity to travel frequently<br />

both domestically and internationally,<br />

often dining out and opting for<br />

the “local” approach to travel versus<br />

being a tourist – making many friends<br />

along the way.<br />

In 2012, Rondel started sharing his<br />

travel and foodie experiences on his<br />

blog, Soul Society 101, and continues<br />

to travel, try new recipes at home and<br />

taste new cuisines and cocktails while<br />

dining out. For more information, visit<br />

www.soulsociety101.com.<br />

(Bio taken from website)

IETY

A<br />

good deal of my travels in<br />

Southeast Asia involved eating<br />

with strangers. Often times<br />

there were two to three people who<br />

came to sit or I came to sit with at<br />

tables in various eating arenas. This<br />

concept does not seem bizarre, until<br />

you think about how the US and<br />

many other Western countries tend<br />

to isolate ourselves in individualism<br />

or take up a table for three with one<br />

person. Southeast Asia has no guidelines<br />

in that sense. Instead, eating<br />

becomes a community event in which<br />

anyone can partake in and meet a<br />

new friend.<br />

Within the tourism baby of Myanmar,<br />

I was able to have a seat at a variety<br />

of food market stalls that had random<br />

people already eating at them.<br />

One of these instances, I sat down<br />

for a bowl of mohinga with the serving<br />

lady and a stranger. I didn’t know<br />

any Burmese and no one knew any<br />

English, but the stranger, the lady<br />

chef and I all knew mohinga.<br />

As I began to eat, the stranger gesticulated<br />

how to eat the delicious mohinga<br />

and the chef knew what to do<br />

for payment when I was done with my<br />

meal. Thismoment of community eating<br />

would occur in Vietnam, Cambodia,<br />

Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong,<br />

Thailand and Indonesia.<br />

I began to relish having a meal with<br />

people I didn’t know. Sometimes they<br />

had conversations with me or simply<br />

educated me on the manners of eating<br />

in their countries. For instance,<br />

the Malays would demonstrate how<br />

to eat food with your hands instead<br />

of utensils. They discussed how this<br />

enabled sharing amongst families,<br />

friends and communities who could<br />

all enjoy each other’s food.<br />

In the case of Cambodia, students<br />

would go home to enjoy their lunches<br />

with their families instead of having<br />

a quick cafeteria meal. Even people<br />

who were visiting from another country<br />

in the region would be welcoming<br />

and inviting. This was most apparent<br />

when two Hong Kong women had<br />

zero issues sitting with me in Chiang<br />

Mai for a bowl of khao soi. As such,<br />

my Blackness was not seen as fearful<br />

to the people of this region, it was a<br />

non-entity<br />

How can<br />

we have a<br />

culture<br />

of food if<br />

we don’t<br />

even take<br />

the time to<br />

enjoy it?<br />

and their<br />

curiosity<br />

came from<br />

me being a<br />

solo traveler.<br />

People had<br />

no qualms<br />

over this<br />

racial difference<br />

and sat<br />

next to me<br />

because<br />

there was a<br />

free seat or<br />

ignored me because they had to get<br />

somewhere. Southeast Asia is a community<br />

and that means you follow the<br />

ebb and flow of it whether you are<br />

from their culture or not.<br />

By the time I got to Hong Kong, this<br />

phenomenon began to push me to eat<br />

slower and enjoy my food as well. We<br />

frequently rush to have quick lunches<br />

or eat our food while walking instead

of sitting and talking with the community<br />

around us as we enjoy a good<br />

meal. There were even occasions<br />

where I ate with languor on purpose,<br />

as being in the community mattered<br />

more than the rest of my agenda.<br />

These moments enhanced my immersion<br />

in Southeast Asian culture, as<br />

eventually someone would say “hello”<br />

whether they knew English or not.<br />

The idea of eating as a community is<br />

lost in America. We all want our slices<br />

of the pie instead of sharing. This<br />

ends up highlighting the culture of<br />

our country, in how we often want to<br />

always do our own work without help.<br />

By contrast, Southeast Asia’s culture<br />

of enjoying the people who are breaking<br />

bread with you harkens back to an<br />

American past that has been long lost<br />

in our haste to Instagram a picture of<br />

our meal before we eat it. How can<br />

we have a culture of food if we don’t<br />

even take the time to enjoy it?<br />

As with many of the lessons I learned<br />

on this Southeast Asia trip, I hope<br />

that those of us in the US can take<br />

the time to truly respect food and be<br />

comfortable in letting new people sit<br />

at our table who want to enjoy eating<br />

as much as we do.

Mike Haynes-Pitts is<br />

the writer and blogger<br />

behind multiethnicmastery.com<br />

a blog<br />

providing education<br />

in financial literacy,<br />

mentorship, tutoring,<br />

cinematography, and<br />

solo travel.<br />

Follow him and his<br />

travels on instagram<br />

@mhptonyc.

<strong>BLACK</strong><br />

CO-OPS

An interview with Jessica Gordon Nembhard<br />

By Beverly Bell and Natalie Miller<br />

Interview Originally Published by Otherworldsarepossible.org

<strong>BLACK</strong> COOPERATIVE<br />

ECONOMICS DURING<br />

ENSLAVEMENT<br />

Black cooperative history closely parallels the<br />

larger African-American civil rights and Black<br />

Liberation movements. After more than 10<br />

years of research, I’ve found that in pretty much<br />

all of the places where Blacks were trying to assert<br />

their civil rights, their independence, their human<br />

rights, they also were either practicing or talking<br />

about the need to utilize cooperative economics in<br />

one form or another.<br />

Asa Philip<br />

Randolph<br />

I’ve put together a continuous record of collective<br />

economics and economic cooperation [practiced<br />

by U.S. Black people] from the 1600s to the 21st<br />

century. They span informal pooling of money to<br />

more formalized mutual aid societies and other<br />

kinds of economic collective relationships, to what<br />

we would now call actual cooperative businesses.<br />

Initially, people pooled resources to buy each other’s<br />

freedom when we were enslaved. This was simple,<br />

but meaningful, as we didn’t own ourselves.<br />

Most people didn’t have a way to earn money, but<br />

sometimes there were skilled laborers who were<br />

allowed to earn a little extra money on a Sunday.<br />

We have some records and some testimony of African-Americans<br />

who talk about saving that money<br />

– first buying themselves, then buying other family<br />

members, or contributing to helping someone buy<br />

themselves. Enslaved African Americans also gardened<br />

together on small plots of land in the slave<br />

quarters to add fresh vegetables to their meager<br />

rations.<br />

Booker T.<br />

Washington<br />

After this, we became much more formal with mutual<br />

aid societies, which are some of the earliest<br />

independent Black organizations. The first Black<br />

mutual aid society started in Newport, Rhode Island<br />

in 1780. Then, the Free African Society in<br />

Philadelphia – the same group that started the African<br />

Methodist Episcopal Church – was formed in<br />

1787 as a mutual aid society.<br />

The earliest cases usually started with burial mutual<br />

aid. Enslaved, even freed people, can’t often

afford to bury their dead. The African American<br />

community revered their dead as joining the<br />

ancestors, and needed to properly bury them.<br />

With a mutual aid society everybody puts in a<br />

small amount per year and then there is a pool<br />

of money. When somebody died in your family,<br />

you could go to your mutual aid society and<br />

they would cover the burial. The second type<br />

of beneficiaries of mutual aid societies were<br />