download the directory of world cinema: american ... - Intellect

download the directory of world cinema: american ... - Intellect

download the directory of world cinema: american ... - Intellect

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

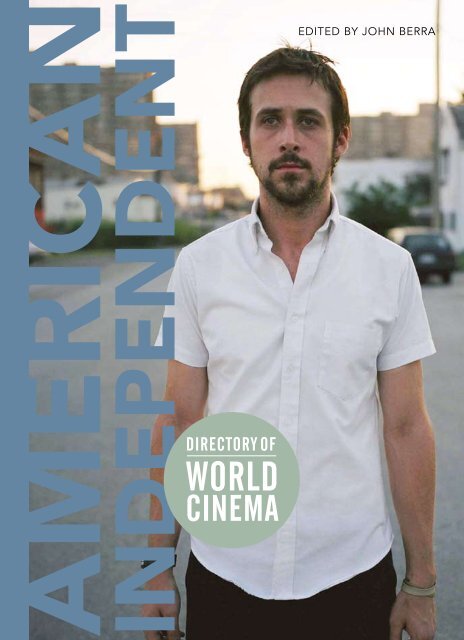

AMERICAN<br />

INDEPENDENT<br />

DIRECTORY OF<br />

WORLD<br />

CINEMA<br />

EDITED BY JOHN BERRA

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

First Published in <strong>the</strong> UK in 2010 by <strong>Intellect</strong> Books, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds,<br />

Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK<br />

First published in <strong>the</strong> USA in 2010 by <strong>Intellect</strong> Books, The University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press,<br />

1427 E. 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA<br />

Copyright © 2010 <strong>Intellect</strong> Ltd<br />

All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval<br />

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,<br />

photocopying, recording, or o<strong>the</strong>rwise, without written permission.<br />

A catalogue record for this book is available from <strong>the</strong> British Library.<br />

Publisher: May Yao<br />

Publishing Assistant: Melanie Marshall<br />

Cover photo: Half Nelson, Journeyman Pictures.<br />

Cover Design: Holly Rose<br />

Copy Editor: Hea<strong>the</strong>r Owen<br />

Typesetting: Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema ISSN 2040-7971<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema eISSN 2040-798X<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema: American Independent ISBN 978-1-84150-368-4<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema: American Independent eISBN 978-1-84150-385-1<br />

2 Japan

ONTENTS<br />

DIRECTORY OF<br />

WORLD CINEMA<br />

AMERICAN INDEPENDENT<br />

Acknowledgements 5<br />

Introduction by <strong>the</strong> Editor 6<br />

Film <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Year 8<br />

The Hurt Locker<br />

Industry Spotlight 12<br />

Interviews with Adam Green<br />

and Wayne Kramer<br />

Cultural Crossover 24<br />

John Waters and Baltimore<br />

Scoring Cinema 28<br />

Mulholland Dr.<br />

Directors 32<br />

Stuart Gordon<br />

Charlie Kaufman<br />

David Lynch<br />

African-American Cinema 42<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

The American Nightmare 62<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Chemical World 84<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Crime 104<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Documentary 126<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Exploitation USA 144<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Familial Dysfunction 162<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Narrative Disorder 180<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

On <strong>the</strong> Road 198<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Queer Cinema 218<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Rural Americana 240<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Slackers 258<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

The Suburbs 276<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Underground USA 296<br />

Essay<br />

Reviews<br />

Recommended Reading 316<br />

American Cinema Online 319<br />

Test Your Knowledge 322<br />

Notes on Contributors 325

CKNOWLEDGENTS<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

This first edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema: American Independent is <strong>the</strong> result<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> commitment <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> committed contributors from <strong>the</strong> fields <strong>of</strong> academia<br />

and film journalism, and I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has<br />

contributed to this volume. Although <strong>the</strong> backgrounds and approaches <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> writers are<br />

quite diverse, <strong>the</strong>ir collective passion for <strong>the</strong> project has yielded an analysis <strong>of</strong> American<br />

Independent Cinema that is both informed and invigorating. The depth and scope <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> entire Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema project is a credit to <strong>the</strong> dedication <strong>of</strong> <strong>Intellect</strong> with<br />

regards to <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> Film Studies, and I would like to thank Masoud Yazdani, May Yao,<br />

Sam King, Melanie Marshall and Jennifer Schivas for <strong>the</strong>ir continued support throughout<br />

what has been an immensely rewarding process.<br />

I would also like to extend special thanks to Dr. Yannis Tzioumakis <strong>of</strong> Liverpool John<br />

Moores University, who organized <strong>the</strong> American Independent Cinema: Past, Present,<br />

Future conference in May, 2009. This was an especially interesting event which encouraged<br />

a wide range <strong>of</strong> approaches towards <strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> American Independent Cinema<br />

and enabled me to make contact with a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contributors who feature in this<br />

volume; <strong>the</strong> essays concerning <strong>the</strong> films <strong>of</strong> Jon Jost, Charlie Kaufman and John Waters,<br />

and also <strong>the</strong> entire section devoted to <strong>the</strong> suburb Film, arose from papers delivered at,<br />

and debate generated by, <strong>the</strong> conference. I also greatly appreciated <strong>the</strong> opportunity<br />

to discuss <strong>the</strong> rich history and ongoing cultural and industrial evolution <strong>of</strong> American<br />

Independent Cinema at such a crucial juncture in <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> this volume. In<br />

addition, I would like to express my gratitude to my fellow contributors to Electric Sheep<br />

magazine for taking on reviews and essays alongside o<strong>the</strong>r commitments, and Adam<br />

Green and Wayne Kramer, two film-makers who took time out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir busy schedules to<br />

candidly discuss <strong>the</strong>ir work and <strong>the</strong>ir navigation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> industrial networks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American<br />

independent sector.<br />

John Berra<br />

Acknowledgements 5

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

6 American Independent<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

BY THE EDITOR<br />

The pressing – and perplexing – question <strong>of</strong> what exactly constitutes an<br />

‘American independent film’ is integral to any account <strong>of</strong> this unique form <strong>of</strong><br />

national <strong>cinema</strong>; even if such studies somehow manage to avoid addressing<br />

<strong>the</strong> question directly, <strong>the</strong>y ultimately <strong>of</strong>fer <strong>the</strong>ir answer through <strong>the</strong> films and<br />

directors which <strong>the</strong>y choose to include or exclude, while arguments centred<br />

around ‘authorship’ or ‘independence <strong>of</strong> spirit’ lead to <strong>the</strong> grey area <strong>of</strong> corporate<br />

sponsorship and <strong>the</strong> suggestion that this sector is simply an <strong>of</strong>fshoot <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Hollywood studios. As with o<strong>the</strong>r volumes in <strong>the</strong> Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

series, this entry does not aim to be a definitive guide to a particular form <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>cinema</strong>; ra<strong>the</strong>r, it covers <strong>the</strong> key genres and <strong>the</strong>matic concerns <strong>of</strong> a still-vital<br />

sector <strong>of</strong> cultural production, focusing on specific films and directors which<br />

exemplify American Independent Cinema at its most socially significant or<br />

aes<strong>the</strong>tically adventurous. While this may not yield a finite definition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> term<br />

‘American independent <strong>cinema</strong>’, it certainly sketches a map <strong>of</strong> its unique industrial<br />

and cultural networks, revealing a <strong>cinema</strong> that balances art with exploitation<br />

and celebrates <strong>the</strong> conventions <strong>of</strong> genre whilst frequently defying <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> writing, media commentary suggests that American independent<br />

<strong>cinema</strong> is in a state <strong>of</strong> emergency, struggling to sustain itself due to<br />

economic crisis; however, reports <strong>of</strong> such industrial issues have referred not<br />

to genuine independents, but to <strong>the</strong> Hollywood sub-divisions which were<br />

established to appeal to <strong>the</strong> niche audiences which turned Steven Soderbergh’s<br />

provocative talk-piece sex, lies and videotape (1989) into a surprise hit<br />

and would later exhibit such enthusiasm for Pulp Fiction (1994) that Quentin<br />

Tarantino’s crime epic grossed over $100 million and became <strong>the</strong> first ‘independent<br />

blockbuster’ – arguably a contradiction in terms, but one which <strong>the</strong><br />

studio system could not afford to ignore. While <strong>the</strong>se boutique operations<br />

have arguably nurtured a number <strong>of</strong> unique film-makers since <strong>the</strong> mid-Nineties<br />

(David O’Russell, Paul Thomas Anderson, Alexander Payne), whilst also investing<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir forerunners (Robert Altman, <strong>the</strong> Coen Bro<strong>the</strong>rs, Jim Jarmusch), <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

aggressive attempt to industrialize independence has ultimately ensured market<br />

saturation, critical cynicism and audience apathy. This retreat from <strong>the</strong> speciality<br />

market by <strong>the</strong> Hollywood majors has been efficiently executed: Warner Independent<br />

and Picturehouse have been closed down, while Miramax and Paramount<br />

Vantage have been severely downsized, despite delivering such cost-efficient<br />

critical and commercial successes as No Country for Old Men (2007) and There<br />

Will Be Blood (2007). However, <strong>the</strong> dependence on prestige to attract audiences<br />

to ‘quality’ product has entailed expensive awards campaigns, promotional exercises<br />

that have brought <strong>the</strong> overall investment in such titles to such a level that<br />

<strong>the</strong> industrial accolades have been undermined by eroding pr<strong>of</strong>it margins.<br />

However, on <strong>the</strong> margins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mainstream, American independent <strong>cinema</strong><br />

remains a vital force, with enterprising directors overcoming budgetary restrictions<br />

to deliver films that are timely and socially relevant, emphasizing characters

over caricatures and psychology over spectacle: both Courtney Hunt’s Frozen<br />

River (2008) and Cary Fukunaga’s Sin Nombre (2009) tackle <strong>the</strong> topic <strong>of</strong> immigration<br />

within <strong>the</strong> confines <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> road movie and succeed in making <strong>the</strong>ir economically-disadvantaged<br />

protagonists fully-formed moral constructs ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

political mouthpieces, <strong>the</strong>reby engaging <strong>the</strong>ir audiences on a humanist level<br />

that transcends genre trappings. Steven Soderbergh continues to surprise, if<br />

only to prove that he still can, alternating between <strong>the</strong> studio project The Informant!<br />

(2009) and <strong>the</strong> The Girlfriend Experience (2009); <strong>the</strong> latter film followed<br />

Soderbergh’s Bubble (2005) in aiming to establish new distribution avenues<br />

for independent <strong>cinema</strong> with The Girlfriend Experience being available as an<br />

Amazon Video on Demand rental title before its <strong>the</strong>atrical release. The subject<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American occupation <strong>of</strong> Iraq, which has been explored by a long line <strong>of</strong><br />

well-meaning but under-performing studio productions, was finally dealt with<br />

in a sufficiently invigorating and incisive manner by Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt<br />

Locker (2009), a taut warzone thriller that largely jettisoned political stance in<br />

favour <strong>of</strong> day-to-day minutiae with occasional bursts <strong>of</strong> life-threatening danger.<br />

The publication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema: American Independent finds<br />

<strong>the</strong> American independent sector coming full circle. 1999 was <strong>the</strong> year that <strong>the</strong><br />

independent sensibility successfully penetrated <strong>the</strong> Hollywood mainstream; films<br />

such as Being John Malkovich, Magnolia and Three Kings utilized studio resources<br />

to fully realize <strong>the</strong> personal visions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir directors, while The Matrix became an<br />

international phenomenon by placing its ground-breaking ‘bullet-time’ effects within<br />

<strong>the</strong> philosophical realms <strong>of</strong> Immanuel Kant and Jean Baudrillard, and <strong>the</strong> microbudget<br />

The Blair Witch Project demonstrated <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> viral marketing, with<br />

an ingenious online advertising campaign, to reach blockbuster status. 2009 found<br />

Hollywood distancing itself from <strong>the</strong> independent sector, concentrating on youthorientated<br />

franchise films, while directors willing to work outside <strong>the</strong> studio system<br />

were able to make politically-engaging and emotionally-challenging projects, which<br />

resonated with audiences on <strong>the</strong> festival circuit and beyond. Of course, <strong>the</strong> ‘next<br />

Blair Witch’ finally emerged in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> Paranormal Activity (2009), but Oren Peli’s<br />

debut feature is already being cited as a triumph <strong>of</strong> marketing strategy ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

individual quality, indicating that <strong>the</strong> American independent sector may be allowed<br />

some creative breathing room before <strong>the</strong> major studios seek to maximize its commercial<br />

potential through in-house development and Oscar acceptance.<br />

Regardless <strong>of</strong> its current industrial importance, <strong>the</strong> cultural diversity <strong>of</strong> American<br />

independent <strong>cinema</strong> is undeniable; from existential road movies, to uncompromising<br />

exploitation, to politicized documentary, to deconstructive genre<br />

<strong>cinema</strong>, to explorations <strong>of</strong> race and sexuality, to depictions <strong>of</strong> dysfunctional<br />

family units, this is a form <strong>of</strong> film-making which thrives on <strong>the</strong> intuitive instincts,<br />

and <strong>of</strong> film-makers who are unafraid to examine <strong>the</strong> social-political fabric <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

nation. Many <strong>of</strong> those films and film-makers are featured in this first edition <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema: American Independent, and <strong>the</strong> essays, reviews<br />

and interviews that follow are indicative <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> American independent<br />

<strong>cinema</strong> and <strong>the</strong> serious critical consideration which its output receives<br />

from cultural commentators; after all, this is a <strong>cinema</strong>tic sector that is home to<br />

both Abel Ferrara and Jon Jost, and has been discussed in depth by both David<br />

Bordwell and Peter Biskind. If American independent <strong>cinema</strong> is synonymous with<br />

<strong>the</strong> open highways <strong>of</strong> Easy Rider (1969), Five Easy Pieces (1970) and Two Lane<br />

Blacktop (1971), <strong>the</strong>n it is hoped that this volume provides <strong>the</strong> appropriate route<br />

map to an unspecified destination.<br />

John Berra<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

Introduction 7

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

The Hurt Locker, First Light Productions/Kingsgatefilms.<br />

FILM OF THE YEAR<br />

THE HURT LOCKER<br />

8 American Independent

The Hurt Locker<br />

Studio/Distributor:<br />

First Light Production<br />

Grosvenor Park Media<br />

Summit Entertainment<br />

Director:<br />

Kathryn Bigelow<br />

Producers:<br />

Kathryn Bigelow<br />

Mark Boal<br />

Nicolas Chartier<br />

Greg Shapiro<br />

Screenwriter:<br />

Mark Boal<br />

Cinematographer:<br />

Barry Ackroyd<br />

Art Director:<br />

David Bryan<br />

Editors:<br />

Chris Innis<br />

Bob Murawski<br />

Composers:<br />

Marco Beltrami<br />

Buck Sanders<br />

Duration:<br />

131 minutes<br />

Cast:<br />

Jeremy Renner<br />

Anthony Mackie<br />

Brian Geraghty<br />

Guy Pearce<br />

Ralph Fiennes<br />

David Morse<br />

Evangeline Lilly<br />

Year:<br />

2009<br />

Synopsis<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

Staff Sergeant William James, a soldier known for his ability to disarm<br />

bombs whilst under fire, joins his latest detail in Iraq and finds he is<br />

an unwelcome presence: his new teammates, Sergeant JT Sandborn<br />

and Specialist Owen Eldridge, are mourning <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir previous<br />

commanding <strong>of</strong>ficer, Sergeant Matt Thompson, whose zen-like<br />

approach to bomb disposal is immediately contrasted by James who,<br />

comparatively, behaves like a bull in <strong>the</strong> proverbial china shop. The<br />

three soldiers gradually bond during <strong>the</strong> remaining month <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

tour, with Sandborn and Eldridge initially infuriated by James’ impulsive<br />

actions in dangerous situations, but eventually respecting his<br />

bravery and <strong>the</strong> efficiency with which he makes life-and-death decisions.<br />

They dismantle a bomb in a crowded public area, evade sniper<br />

fire in <strong>the</strong> open desert, and become involved with a local boy who<br />

makes a living selling pirate DVDs. James attends sessions with <strong>the</strong><br />

base <strong>the</strong>rapist, but prefers to relieve stress by playing violent video<br />

games and knocking back alcohol. Back home in <strong>the</strong> States, James<br />

is unable to fully adjust to family life, and returns for ano<strong>the</strong>r tour <strong>of</strong><br />

duty in Iraq.<br />

Critique<br />

The post-9/11 era has led to <strong>the</strong> political engagement <strong>of</strong> filmmakers<br />

working both within <strong>the</strong> studio system and on its industrial margins,<br />

resulting in a series <strong>of</strong> films that examine <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> American<br />

military presence on foreign soil, both in <strong>the</strong> field and back in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States. Studio investment has led to such films as Paul Haggis’<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Valley <strong>of</strong> Elah (2007), Kimberley Peirce’s Stop-Loss (2008) and<br />

Ridley Scott’s Body <strong>of</strong> Lies (2008), while <strong>the</strong> independent sector has<br />

delivered David Ayer’s Harsh Times (2005), Brian De Palma’s Redacted<br />

(2007) and James. C. Strouse’s Grace is Gone (2007). Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

projects have received critical respect for <strong>the</strong>ir worthy intentions but<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have all failed commercially, with audiences unwilling to visit <strong>the</strong><br />

multiplex to see a Hollywood version <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> combat footage, or <strong>the</strong><br />

grief <strong>of</strong> bereaved families that has become a fixture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> evening<br />

news. An Academy-Award-nominated performance by Tommy Lee<br />

Jones could not generate interest In <strong>the</strong> Valley <strong>of</strong> Elah, while a positive<br />

Sundance reception for <strong>the</strong> John Cusack vehicle Grace is Gone<br />

did not lead to wide distribution. Even <strong>the</strong> cross-generational star<br />

power <strong>of</strong> Leonardo DiCaprio and Russell Crowe could not carry <strong>the</strong><br />

$70 million Body <strong>of</strong> Lies beyond a disappointing $39 million at <strong>the</strong><br />

domestic box <strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

By comparison with those films, Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker<br />

arrived ‘under <strong>the</strong> radar’, much like <strong>the</strong> insurgent IEDs (improvised<br />

explosive devices) that her mismatched team <strong>of</strong> soldiers must dismantle<br />

if <strong>the</strong>y are to make it through <strong>the</strong>ir tour <strong>of</strong> duty largely unsca<strong>the</strong>d.<br />

Unlike <strong>the</strong> aforementioned films, The Hurt Locker does not weigh<br />

in on <strong>the</strong> political arguments surrounding <strong>the</strong> Iraq conflict, ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

it details <strong>the</strong> activities, both on duty and <strong>of</strong>f duty, <strong>of</strong> three soldiers,<br />

paying particular attention to <strong>the</strong> character <strong>of</strong> Staff Sergeant William<br />

Film <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Year 9

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

10 American Independent<br />

James, and examines <strong>the</strong> male psyche in situations <strong>of</strong> extreme physical<br />

and emotion duress. Ra<strong>the</strong>r than relying on a traditional three-act<br />

structure, and <strong>the</strong> mentor-student conflict that is characteristic <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

American military movie, or <strong>the</strong> fatalistic relationships that provide<br />

<strong>the</strong> dramatic friction in Bigelow’s own work – such as <strong>the</strong> fetishistic<br />

cop thriller Blue Steel (1989) or her cyberpunk excursion Strange Days<br />

(1995) – The Hurt Locker opts for an episodic narrative, one that probably<br />

stems from screenwriter Mark Boal’s prior experience as a war<br />

correspondent. Bigelow’s film follows James, Sandborn and Eldridge<br />

from mission to mission, taking in <strong>the</strong>ir downtime and interaction with<br />

<strong>the</strong> local community. Almost as if she is working with <strong>the</strong> virtual-reality<br />

technology that was integral to Strange Days (video units which<br />

allow users to experience <strong>the</strong> extreme activities <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, in <strong>the</strong> first<br />

person), Bigelow takes to <strong>the</strong> mean streets <strong>of</strong> Iraq (<strong>the</strong> film was shot in<br />

Jordan) and captures much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> action from <strong>the</strong> perspective <strong>of</strong> her<br />

protagonists. Establishing overhead shots and sweeping pans are not<br />

part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic; much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> suspense <strong>of</strong> The Hurt Locker stems<br />

from <strong>the</strong> unknown, <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> enemy – or friendly – fire, which could<br />

be waiting on <strong>the</strong> next patrol, around <strong>the</strong> next corner, or beyond <strong>the</strong><br />

next road block.<br />

The title refers to <strong>the</strong> place deep inside where <strong>the</strong>se men put away<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir pain, frustration and fear, and Bigelow expertly conveys James’<br />

ability to substitute emotion with adrenaline; an unlikely ‘hero’ and<br />

team leader, James (portrayed brilliantly by Jeremy Renner) is not a<br />

typical ‘action man’ and Renner’s somewhat pudgy features and short<br />

stature would usually find him lost amidst an ensemble in a Hollywood<br />

war epic ra<strong>the</strong>r than taking centre stage. Bigelow has, <strong>of</strong> course,<br />

made two earlier films about groups with charismatic leaders: <strong>the</strong><br />

vampire thriller Near Dark (1987) with Lance Henriksen as <strong>the</strong> head<br />

<strong>of</strong> a makeshift family <strong>of</strong> bloodsuckers is an enduring cult item; and<br />

Point Break (1991), with Patrick Swayze as <strong>the</strong> sky-diving mastermind<br />

<strong>of</strong> a gang <strong>of</strong> bank robbers who mix crime with extreme sports, has<br />

become something <strong>of</strong> a pop-culture classic. However, while those<br />

films were undeniably exciting and technically pr<strong>of</strong>icient, <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

firmly rooted within Hollywood genre and <strong>the</strong> folklore <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American<br />

outlaw, <strong>the</strong>ir moments <strong>of</strong> psychological insight occasionally at<br />

odds with <strong>the</strong> mythic sensibility applied to main protagonists. The<br />

Hurt Locker strips away such iconography to capture ordinary people<br />

undertaking day-to-day duties in a morally-questionable international<br />

conflict. The action sequences are excellent, but it is <strong>the</strong> small, telling,<br />

explorations <strong>of</strong> character that linger: a heavy after-hours drinking session<br />

which lurches uncomfortably from joking to a dark night <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

soul; James opening a juice box for his fellow soldier whilst pinned<br />

down by sniper fire in <strong>the</strong> desert; Sandborn breaking down in <strong>the</strong> final<br />

days <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tour and demanding that James explain how he keeps his<br />

sanity amidst <strong>the</strong> chaos.<br />

The character <strong>of</strong> James is something <strong>of</strong> an enigma throughout, as<br />

perpetually in motion as Bigelow’s hand-held camera, but <strong>the</strong> final ten<br />

minutes find him back with his family in <strong>the</strong> United States and bring<br />

his seemingly-contradictory nature (careless yet caring, impetuous<br />

yet informed) into focus: in a suburban supermarket, James stares at<br />

an entire isle <strong>of</strong> cereal, defeated by having to make a decision about

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r to go with <strong>the</strong> Cheerios or <strong>the</strong> Captain Crunch. Eventually<br />

selecting one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> varieties on <strong>of</strong>fer, he meets up with his wife<br />

(Evangeline Lilly), who has already loaded up her trolley. James can<br />

only function amidst chaos, and can only make a decision when it is<br />

a life-or-death choice that has a definitive outcome. His love for his<br />

son is evident in <strong>the</strong> tender manner in which he cradles <strong>the</strong> child, but<br />

as he talks to his family about his experiences in <strong>the</strong> field in a manner<br />

<strong>of</strong> almost winsome longing: it is obvious that he would ra<strong>the</strong>r be<br />

somewhere else. In <strong>the</strong> closing moments, back in Iraq for ano<strong>the</strong>r tour<br />

<strong>of</strong> duty, James strides towards yet ano<strong>the</strong>r unexploded IED, calmly<br />

composed and clad in his metal suit. A loud blast <strong>of</strong> rock music plays<br />

on <strong>the</strong> soundtrack, and it is clear that this is how James sees himself<br />

when he is putting his life on <strong>the</strong> line on foreign soil: a rock star<br />

amongst soldiers, always aiming to top <strong>the</strong> previous ‘performance’.<br />

The opening quote states, ‘War is a drug’, and <strong>the</strong> final image <strong>of</strong><br />

James back in <strong>the</strong> thick <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> action brings that statement full circle.<br />

Incisive and invigorating, The Hurt Locker eschews politics for sheer<br />

experience, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten inexplicable allure <strong>of</strong> mortal danger, and<br />

delivers an uncompromising depiction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern battlefield.<br />

John Berra<br />

Film <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Year 11

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> AireScope Pictures.<br />

INDUSTRY SPOTLIGHT:<br />

INTERVIEWS WITH ADAM GREEN<br />

AND WAYNE KRAMER<br />

12 American Independent

Interview with Adam Green<br />

A cursory perusal <strong>of</strong> two chapters in this volume (The American Nightmare and<br />

Exploitation USA) will reaffirm <strong>the</strong> assertion that horror is <strong>the</strong> genre <strong>of</strong> choice for<br />

first-time film-makers seeking to make a movie which will both <strong>the</strong> attract attention<br />

<strong>of</strong> a core audience, and deliver <strong>the</strong> required return on investment to endear <strong>the</strong>m<br />

to financiers in <strong>the</strong> future. Unfortunately, since <strong>the</strong> low-budget horror heyday <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> 1970s, which gave birth to such cult classics as Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain<br />

Saw Massacre (1974) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), many independent<br />

horror films have felt more like cynical positioning exercises than exciting excursions<br />

into genre territory. Such comments, however, do not apply to Adam Green,<br />

whose swamp-bound slasher Hatchet delivers shocks and laughs in equal measure<br />

without ever descending into <strong>the</strong> sheer nastiness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> current ‘torture porn’<br />

craze, or <strong>the</strong> postmodern parody <strong>of</strong> Scream (1996) and its imitators. Harry Knowles<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ain’t it Cool News.com insisted that, ‘Adam Green is <strong>the</strong> real deal – and Victor<br />

Crowley is a friggin’ fantastic horror icon waiting to be unleashed on y’all’, later<br />

including Hatchet in his Top Ten Films <strong>of</strong> 2007. A limited <strong>cinema</strong> release courtesy<br />

<strong>of</strong> independent distributor Anchor Bay yielded impressive returns on a per-screen<br />

basis, and Hatchet found more fans on DVD. Adam took time out <strong>of</strong> post-production<br />

work for his latest thriller Frozen (2010) to discuss his career to date, his influences,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> inherent challenges in making low-budget genre movies.<br />

You are most widely known as <strong>the</strong> director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> horror film Hatchet (2006.<br />

How did you develop an interest in <strong>the</strong> horror genre, and which film-makers<br />

have had a particular influence on you with regards to ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ir films or<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir working methods?<br />

Horror has always been my first love in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> films I choose to go out <strong>of</strong> my<br />

way to see. When I was just 7 years old, my older bro<strong>the</strong>r showed me Friday <strong>the</strong><br />

13th Part 2 (1981) The Thing (1981) and Halloween (1978). It was love at first sight.<br />

I was not so much scared by <strong>the</strong>m as I was challenged to figure out how <strong>the</strong>y<br />

pulled <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong>ir effects, and also inspired by how ‘cool’ <strong>the</strong> villains were. I was only<br />

8 years old when I first invented Victor Crowley, so in many ways Hatchet was over<br />

20 years in <strong>the</strong> making. In terms <strong>of</strong> film-makers who have inspired me, I’d have to<br />

say it still comes down to Steven Spielberg. E.T. – The Extra Terrestrial (1982) will<br />

always be my favourite film <strong>of</strong> all time and I know that may not get me much credit<br />

with <strong>the</strong> horror fans, but it’s <strong>the</strong> truth. Spielberg will always be that unreachable<br />

shining star that I will strive to reach as both an artist and a human being. O<strong>the</strong>r<br />

favourites include John Carpenter, Guillermo del Toro, and I rip <strong>of</strong>f John Landis in<br />

almost everything I do. I always find it funny when critics compare Hatchet directly<br />

to Friday <strong>the</strong> 13 th, (1980) when An American Werewolf in London (1981) was my<br />

inspiration in terms <strong>of</strong> comedic tone, shooting style, and composition.<br />

How did you raise <strong>the</strong> $1.5 million budget for Hatchet, and how did you<br />

secure cameo appearances from such genre icons as Robert Englund, Kane<br />

Hodder and Tony Todd?<br />

My team and I were able to raise <strong>the</strong> money for Hatchet by having a proposal<br />

package that spelled everything out. Ano<strong>the</strong>r important device was a mock<br />

trailer that told <strong>the</strong> story <strong>of</strong> Victor Crowley and got people excited about seeing<br />

<strong>the</strong> film. In fact, that mock trailer was <strong>the</strong> template for <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atrical trailer when<br />

Hatchet was released in 2007. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> producers, Sarah Elbert, had recently<br />

produced <strong>the</strong> special features for <strong>the</strong> Friday <strong>the</strong> 13TH DVD box set and was able<br />

to get <strong>the</strong> script for Hatchet in front <strong>of</strong> FX wizard John Carl Buechler. He helped<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

Industry Spotlight 13

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

14 American Independent<br />

me create <strong>the</strong> make-up job <strong>of</strong> ‘Young Victor Crowley’ for <strong>the</strong> mock trailer. He<br />

also slipped <strong>the</strong> script to Kane Hodder, who signed on almost instantly. Fate<br />

found me at <strong>the</strong> same party as Robert Englund one night, and though I didn’t<br />

have <strong>the</strong> audacity to approach him about my project, he instead approached me<br />

and asked where I got <strong>the</strong> Marilyn Manson Suicide King Shit T-shirt that I was<br />

wearing. Tony Todd was already working with Buechler on ano<strong>the</strong>r project and I<br />

met him on his set. Again, I didn’t bring up Hatchet at first, but once I knew him<br />

a little more, he asked me about it. These guys are all legends in <strong>the</strong> genre and I<br />

think what <strong>the</strong>y responded to was <strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong> Hatchet and how it was a celebration<br />

<strong>of</strong> what horror movies used to be.<br />

There is a fine line between comedy and horror, one that Hatchet treads skilfully<br />

and knowingly. How did you achieve <strong>the</strong> balance between <strong>the</strong> laughs and<br />

<strong>the</strong> shocks, and to what extent did you ‘find’ <strong>the</strong> film in <strong>the</strong> editing room?<br />

I was making my living as a comedy writer at <strong>the</strong> time, so it was a style that I was<br />

very comfortable with. With my biggest inspiration being An American Werewolf<br />

in London, I could see that <strong>the</strong> key was to keep <strong>the</strong> comedy out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> horror.<br />

In Hatchet, <strong>the</strong> villain was never presented in a light manner, unlike <strong>the</strong> cast<br />

<strong>of</strong> characters that were trying to survive <strong>the</strong> situation. I also find that comedy<br />

is <strong>the</strong> quickest and easiest way to make characters likeable, endearing and<br />

three-dimensional. I wrote <strong>the</strong> ‘victims’ in Hatchet in a humorous way and it was<br />

Hatchet’s sense <strong>of</strong> humour that really won over <strong>the</strong> crowds. That experience can<br />

never be replicated on DVD at home, no matter how many rowdy, gore-loving<br />

friends you cram into your living room. Nothing about Hatchet was found in <strong>the</strong><br />

editing room as <strong>the</strong> budget limitations meant that I could rarely get more than<br />

a few takes. In fact, Hatchet’s running time is technically under 80 minutes if you<br />

don’t include <strong>the</strong> credits – that’s how lean <strong>the</strong> script and <strong>the</strong> shoot had to be.<br />

The trend in independently-produced horror <strong>cinema</strong> since <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong><br />

The Blair Witch Project (1999) has been to utilize lo-fi production methods,<br />

or to approach <strong>the</strong> genre from a psychological perspective, yet Hatchet is<br />

an unapologetic throwback to <strong>the</strong> studio-financed body-count horror films<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1980s. What do you particularly like about that period <strong>of</strong> horror<br />

<strong>cinema</strong>, and to what extent do you think Hatchet imbues that material with<br />

an independent sensibility?<br />

In my opinion, <strong>the</strong> lo-fi production gimmick only works if it is a story point. The<br />

Blair Witch Project was a brilliantly innovative piece <strong>of</strong> storytelling that spawned<br />

a whole new genre <strong>of</strong> ‘found footage’ films but, more <strong>of</strong>ten than not, <strong>the</strong> lo-fi<br />

thing is a cop out. You’ll hear film-makers give a laundry list <strong>of</strong> why <strong>the</strong>y chose<br />

to shoot a film with low-fi gear but <strong>the</strong> truth is really that <strong>the</strong>y just couldn’t get<br />

a bigger budget toge<strong>the</strong>r. When I wrote Hatchet, I merely wrote <strong>the</strong> type <strong>of</strong><br />

movie that I grew up on and wanted to see again. The goal was never to make<br />

<strong>the</strong> 80s’ ‘slasher’ formula hip again but to remind people what horror used to be<br />

like and give people that <strong>the</strong>atrical communal experience <strong>of</strong> laughing, cheering,<br />

and screaming toge<strong>the</strong>r. The independent sensibility really comes down to <strong>the</strong><br />

script and <strong>the</strong> fact that I was making a movie that brought <strong>the</strong> old formula back<br />

in a modern way. No Hollywood studio would have ever touched a movie that’s<br />

got comedy in one scene and <strong>the</strong>n a woman having her head torn <strong>of</strong>f in <strong>the</strong><br />

next. We had a very limited budget, but we also had a lot <strong>of</strong> good people and<br />

close friends that cashed in every favour <strong>the</strong>y had. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> best things about<br />

Hatchet is that, when you watch it, you can almost feel <strong>the</strong> crew scrambling<br />

around, covered in fake blood, doing whatever <strong>the</strong>y could to get it done.

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> AireScope Pictures.<br />

Despite support from critics, particularly Harry Knowles <strong>of</strong> Ain’t it Cool<br />

News, Hatchet grossed a disappointing $155,873 domestically before finding<br />

a wider audience on DVD. Do you think <strong>the</strong> genre has become dominated by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Hollywood majors to <strong>the</strong> point that even commercially-orientated independent<br />

productions have trouble breaking through <strong>the</strong>atrically?<br />

Something to keep in mind is that Hatchet opened on only 80 screens and<br />

through Anchor Bay, a distributor that, up until <strong>the</strong>n, had only been a DVD<br />

catalogue company. The person in charge at <strong>the</strong> time seemed to feel that, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> buzz, audiences would just ‘find’ it, but most people had no idea it was out,<br />

or <strong>the</strong>y lived two states away from a <strong>the</strong>atre playing it. In fact, unless you were<br />

a frequent reader <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> horror websites, <strong>the</strong>re was no way <strong>of</strong> knowing <strong>the</strong> film<br />

existed. A great example is how in San Diego <strong>the</strong>re wasn’t even a poster or a<br />

listing on <strong>the</strong> marquee <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre that was playing Hatchet. It was essentially<br />

an experiment to see if online buzz and my MySpace page alone could open a<br />

movie, and it was devastating to watch it go down like that. Yet, when Hatchet<br />

opened, it actually did surprisingly well. Shows sold out [in] Los Angeles,<br />

Baltimore, Boston, Austin, and New York. In fact, Hatchet grossed $17,000 on<br />

one screen in Los Angeles alone, beating <strong>the</strong> studio film 3:10 to Yuma (2007)<br />

that weekend. At <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day, though, <strong>the</strong> only horror films that are really<br />

shining at <strong>the</strong> box <strong>of</strong>fice have outrageous budgets behind <strong>the</strong>ir campaigns and<br />

usually sport pre-packaged titles that bring even <strong>the</strong> most passive fans out in<br />

droves. A tiny film like Hatchet had no chance <strong>of</strong> standing up to <strong>the</strong> remake <strong>of</strong><br />

Halloween (2007). At <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day, though, <strong>the</strong> fact that Hatchet went from<br />

passion project to a <strong>the</strong>atrical run was something to be grateful for and, on DVD,<br />

it has been a monster hit for Anchor Bay. It is far and away <strong>the</strong> biggest success<br />

<strong>the</strong>y’ve ever had with an original genre title and a sequel is now in <strong>the</strong> works. So,<br />

while some may consider $155,000 on 80 unadvertised screens disappointing,<br />

for everyone who was actually involved it was really quite a feat.<br />

Industry Spotlight 15

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

16 American Independent<br />

Hatchet was swiftly followed by Spiral (2007), <strong>the</strong> story <strong>of</strong> a socially-awkward<br />

telemarketing agent haunted by his past which was marketed as a horror<br />

film, but plays more successful as a dark character study. How challenging<br />

was it to shift from a gross-out horror film to something more psychological?<br />

Spiral was shot before Hatchet had finished post-production. Joel David Moore<br />

and I had such an exceptional time working toge<strong>the</strong>r on Hatchet that we just didn’t<br />

want it to end, so when he showed me his script for Spiral, it was a no-brainer to<br />

sign on. What I loved about it was that, although it was a small arthouse film, it was<br />

a project where I could flex a completely different creative and artistic side <strong>of</strong> myself.<br />

Knowing how Hollywood works, I knew that Hatchet was going to define me around<br />

town and I didn’t want to be put in that ‘box’. Shifting gears was really not difficult<br />

at all, though having <strong>the</strong> film come out right on Hatchet’s heels was a bit scary. At<br />

Fantasia in Montreal that summer, Hatchet played on Friday night to an 800 seat<br />

sold-out crowd that was on <strong>the</strong>ir feet cheering, and <strong>the</strong>n Spiral played <strong>the</strong> next night<br />

to a crowd <strong>of</strong> 100. When I introduced <strong>the</strong> film, and looked out at <strong>the</strong> fans in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

Hatchet T-shirts, all I remember thinking was, ‘Oh no, <strong>the</strong>y’re gonna hate this.’ But<br />

many said <strong>the</strong>y liked Spiral more than Hatchet. For me, Spiral is <strong>the</strong> movie that much<br />

better illustrates what I am made <strong>of</strong> as a director.<br />

You co-directed Spiral with Joel Moore, who also played <strong>the</strong> lead role. How did<br />

you collaborate, and do you think that this is a working method that would be<br />

more characteristic <strong>of</strong> an independent production than a studio feature?<br />

Co-directing with Joel Moore really couldn’t have gone better. When he first<br />

asked me to come onboard, it was because he was already wearing <strong>the</strong> hat <strong>of</strong><br />

producer, writer, and lead actor, and he wanted to make sure that nothing fell<br />

through <strong>the</strong> cracks. We sat down and created a bible <strong>of</strong> shot lists and visual concepts<br />

so that <strong>the</strong>re was never <strong>the</strong> chance <strong>of</strong> not seeing eye-to-eye when making<br />

decisions on set. Once we began production, I took on <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> ‘leader’,<br />

though Joel was still involved with every choice. Co-directing is not something I<br />

would encourage, although I had a great experience doing it. Joel is one <strong>of</strong> my<br />

closest friends, and <strong>the</strong>re was complete trust on both sides. It would be naïve to<br />

think that it would always work that way. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cases I’ve heard <strong>of</strong> usually<br />

involve a first-time director who could not be removed from directing <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

script but was forced to agree to have an experienced director come onboard in<br />

order to secure financing. No one ever wants to admit it, but it happens a lot.<br />

Your o<strong>the</strong>r pr<strong>of</strong>essional activities have ranged from stand-up comedy to<br />

fronting <strong>the</strong> heavy metal band Haddonfield. Do <strong>the</strong>se activities complement<br />

each o<strong>the</strong>r in some way, or do <strong>the</strong>y represent distinctly different outlets for<br />

your creativity?<br />

I suppose it all comes down to that childhood thing <strong>of</strong> wanting to entertain and<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that I needed <strong>the</strong> attention and that rush <strong>of</strong> adrenaline. The first time I did<br />

stand-up it was simply to prove to myself that I could do it. It’s <strong>the</strong> scariest thing in<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>, and any stand-up who tells you that <strong>the</strong>y are comfortable up <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

liar. But I conquered my fear, did it for a few years as a hobby, and learned whatever<br />

I could about timing, word choice, and how to get <strong>the</strong> reactions I want. There’s just<br />

something in performing live that really feels good. The instant gratification <strong>of</strong> hearing<br />

a large crowd laugh at a joke, or <strong>the</strong> relaxed high I get after screaming myself<br />

into <strong>the</strong> stage with a band. Film-making is <strong>the</strong> only thing I consider a pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

activity though. I’m not serious or good enough at any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r pastimes to<br />

make a good living at <strong>the</strong>m. I guess I never outgrew <strong>the</strong> whole ‘Hey, Mom look at<br />

me’ thing. And thankfully, I also have a mo<strong>the</strong>r who never outgrew wanting to look.<br />

John Berra

Interview with Wayne Kramer<br />

Although born in Johannesburg-Kew, South Africa, <strong>the</strong> writer-director Wayne<br />

Kramer always aspired to work in <strong>the</strong> American film industry, and has succeeded<br />

in establishing a career within <strong>the</strong> independent sector. After toiling away as a<br />

screenwriter for many years, and suffering <strong>the</strong> setback <strong>of</strong> struggling to complete<br />

a directorial debut which never saw <strong>the</strong> light <strong>of</strong> day, Kramer finally enjoyed critical<br />

success with The Cooler (2003), a dark comedy set in Las Vegas which showcased<br />

superb performances from William H Macy as a perpetually-unlucky former<br />

gambler in debt to Alec Baldwin’s volatile yet strangely-loyal casino boss. Kramer<br />

followed his breakthrough with Running Scared (2006), a violent crime thriller that<br />

was released by New Line Cinema and became a cult sensation on DVD. This<br />

interview was conducted following <strong>the</strong> release <strong>of</strong> Crossing Over (2009), Kramer’s<br />

controversial immigration drama which, despite coaxing Hollywood superstar<br />

Harrison Ford into a rare excursion into independent territory, was effectively<br />

discarded by financier and distributor, The Weinstein Company. Although <strong>the</strong><br />

studio-sanctioned version <strong>of</strong> Crossing Over that was eventually released deviates<br />

dramatically from Kramer’s original vision, it remains a brave attempt to tackle a<br />

difficult issue within <strong>the</strong> confines <strong>of</strong> narrative <strong>cinema</strong>. Kramer discussed his career<br />

to date and elaborated on <strong>the</strong> behind-<strong>the</strong>-scenes battles <strong>of</strong> Crossing Over.<br />

The Cooler (2003) is <strong>of</strong>ten referred to as your directorial debut but, according<br />

to IMDB, your first directing credit is actually Blazeland (1992), which<br />

apparently deals with a dead rock star returning from <strong>the</strong> grave to promote<br />

a new band. What has happened to this movie?<br />

Technically, The Cooler is actually my directorial debut since Blazeland was<br />

never completed and no one has seen <strong>the</strong> film – and I’d like to keep it that way!<br />

Blazeland was an absolute nightmare from beginning to end; an investor who<br />

thought I might amount to something decided to invest about a hundred grand<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Wayne Kramer.<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

18 American Independent<br />

in a low-budget feature. It was about a Jim-Morrison-type rock star whose vocal<br />

chords are severed by windshield glass during a car wreck and he loses <strong>the</strong> ability<br />

to sing. His manager and his groupies plot his comeback from <strong>the</strong> rock star’s<br />

gothic mansion. They’ve been convinced by a crackpot scientist that, if <strong>the</strong>y can<br />

find <strong>the</strong> right vocal chord match for <strong>the</strong> rock star’s voice, he can perform <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>world</strong>’s first vocal-chord transplant. So, this crazy group keeps luring wannabe<br />

bands to <strong>the</strong> mansion and <strong>of</strong>fing <strong>the</strong>m, until <strong>the</strong>y find <strong>the</strong> right candidates for<br />

his transplant. I was completely inexperienced with regards to production and<br />

I brought onboard a very sweet guy named Russell Droullard to produce <strong>the</strong><br />

film for me – neglecting <strong>the</strong> fact that he had zero experience, o<strong>the</strong>r than having<br />

been a production assistant. It only got worse from <strong>the</strong>re. We hired a DP based<br />

on his having shot one documentary – <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> which was that <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

first week <strong>of</strong> photography turned out over-exposed and out <strong>of</strong> focus. We had to<br />

reshoot, as well as hire an entirely new crew. We had rented a warehouse down<br />

in Fullerton, Orange County and were shooting <strong>the</strong>re without any permits. Of<br />

course, <strong>the</strong> police turned up within a week or two and suddenly we were paying<br />

out <strong>of</strong> our eyeballs for permits and insurance and everything else that goes with<br />

that. I was broke and homeless and living <strong>of</strong>f production catering.<br />

Did you complete Blazeland and does it still exist in any form?<br />

I spent <strong>the</strong> next two years saving every cent I could and begging and borrowing<br />

money from my family to complete production – which I did for $7,000. During that<br />

time, I had gone down on hands and knees and begged a post-production house<br />

in LA to let me rent an editing room. Since I was homeless, I basically slept in <strong>the</strong><br />

cutting room for about three months – until <strong>the</strong>y got wise to me and told me to<br />

rent an apartment or lose <strong>the</strong> cutting room, which I was barely paying for in <strong>the</strong> first<br />

place. As far out on a limb as I was, I remember my cutting-room experience quite<br />

fondly. Oliver Stone had ten editing rooms down <strong>the</strong> hall from me and was cutting<br />

The Doors, which was really cool. Anyway, after I finished cutting <strong>the</strong> new footage<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r, I tried to find a distributor. One day, some fly-by-night producer turned<br />

me onto this so-called distributor operating out <strong>of</strong> Orlando, Florida – who, if I had<br />

done my homework, I would have found out was a thief and a fraud and was already<br />

being sued by a dozen film-makers and investors. He managed to convince me to<br />

release <strong>the</strong> negative to him and that he would finish posting <strong>the</strong> film in Florida and<br />

provide us with home-video distribution. Two years later, <strong>the</strong> guy still had not delivered<br />

<strong>the</strong> film – and wouldn’t even show us what he had done! Russell and I spent<br />

thousands <strong>of</strong> dollars on lawyers and eventually a private investigator to track this guy<br />

down. When his wife realized a PI was sniffing around, she contacted us and <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

to ship <strong>the</strong> negative back to <strong>the</strong> lab. We agreed, and that’s <strong>the</strong> last I saw <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> film.<br />

I seriously doubt that <strong>the</strong> lab has kept <strong>the</strong> negative all <strong>the</strong>se years. All that exists <strong>of</strong><br />

Blazeland is a work print in my garage.<br />

What kind <strong>of</strong> career path did you take between <strong>the</strong> Blazeland experience<br />

and The Cooler?<br />

I always intended to use screenwriting as a means to arrive at a directing career<br />

so, all throughout that period, I was writing away. I was also doing any job I<br />

could to survive. Finally, I was able to sell a script I wrote called Mindhunters to<br />

20th Century Fox. For <strong>the</strong> first time in my life I had made some real money and<br />

had a small cushion to make <strong>the</strong> right choices for myself. I had wanted to direct<br />

Mindhunters, but I was essentially told that, if I tried to attach myself, <strong>the</strong> deal<br />

would fall apart, so I took <strong>the</strong> money and walked away. Fox put <strong>the</strong> project into<br />

turnaround about a year later and Intermedia bought it from <strong>the</strong>m and set it up<br />

with Dimension Films. They brought on about ten different writers. At no point did

<strong>the</strong>y ever come back to me and say, ‘have ano<strong>the</strong>r shot at it.’ They turned it from a<br />

taut suspense thriller into a full-on action film and <strong>the</strong>re are plot holes that you can<br />

drive ten trucks through. Nothing makes sense – <strong>the</strong> characters are all supposed<br />

to be <strong>the</strong> best <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> best in <strong>the</strong> FBI Academy and every one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m makes <strong>the</strong><br />

stupidest decisions. People mistakenly think I wrote Mindhunters after The Cooler<br />

but it was written in 1997 and shot in 2002. Dimension kept it on <strong>the</strong> shelf for<br />

about two and a half years. The money and residuals have been good over <strong>the</strong><br />

years, so I don’t entirely regret <strong>the</strong> experience.<br />

Did you have a particular interest in, or experience <strong>of</strong>, Las Vegas before you<br />

wrote and directed The Cooler? The film presents a fairly balanced view<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city in that it revels in some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> glamour and nostalgia associated<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Strip, yet does not shy away from <strong>the</strong> tragedy and violence that<br />

occurs <strong>the</strong>re on a daily basis, especially around <strong>the</strong> casino business.<br />

I always had more <strong>of</strong> a <strong>cinema</strong>tic interest in Vegas than a hardcore gambler’s<br />

interest. I loved <strong>the</strong> Fellini-esque <strong>world</strong> <strong>of</strong> downtown Las Vegas – <strong>the</strong> section<br />

that attracted <strong>the</strong> more old school, hard luck cases than <strong>the</strong> Strip. I’ve always<br />

been a sucker for film noir and damaged-character studies and <strong>the</strong> seedy, yet<br />

glamorous <strong>world</strong> <strong>of</strong> Vegas really spoke to me. To me, <strong>the</strong> film was always more<br />

about <strong>the</strong> interaction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> characters – <strong>the</strong> weird triangle <strong>of</strong> relationships – than<br />

any real fascination with gambling, o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> superstitious nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

entire enterprise that lent itself perfectly to telling an old-fashioned love story<br />

with a contemporary, high-concept spin. The project came about when my friend<br />

Frank Hannah pitched <strong>the</strong> idea to me. I fell in love with it immediately and asked<br />

him if he wanted to write it with me – and I would do everything in my power to<br />

get it made. Frank is <strong>the</strong> real deal when it comes to gambling. He is obsessed<br />

with <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong> and makes religious trips to Vegas to hit <strong>the</strong> tables. He basically<br />

served as our technical director on <strong>the</strong> film. Right from Frank’s first pitch, I knew I<br />

could write those characters and put flesh on <strong>the</strong>ir bones.<br />

There was some controversy over <strong>the</strong> scene in which Alec Baldwin’s oldschool<br />

casino boss kicks a ‘pregnant’ woman in <strong>the</strong> stomach. Although it is<br />

made clear that he knows that she is faking her pregnancy, some viewers<br />

found it hard to get past <strong>the</strong> brutality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moment. Were <strong>the</strong>re any particular<br />

challenges to executing or editing that scene, and were your worried<br />

that it might repel members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience who had been enjoying <strong>the</strong><br />

usual love story?<br />

Right from <strong>the</strong> moment that we wrote that scene in <strong>the</strong> script, I knew it was going<br />

to blow people’s minds. The challenge was how to pull it <strong>of</strong>f and milk it just long<br />

enough before <strong>the</strong> reveal, without having <strong>the</strong> audience rushing from <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre.<br />

We literally had to time <strong>the</strong> editing so that if someone got up to leave <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre,<br />

he/she would hear a gasp from <strong>the</strong> audience before <strong>the</strong>y could get to <strong>the</strong> door –<br />

and would realize that it was a fake pregnancy. And true to our calculations, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

were always some audience members who couldn’t handle it and decided to<br />

walk out until <strong>the</strong>y heard laughter or clapping from <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience. They<br />

always returned sheepishly to <strong>the</strong>ir seats. Alec Baldwin tells <strong>the</strong> story that when he<br />

first read <strong>the</strong> script, he got to that scene and threw it down, declaring <strong>the</strong>re was<br />

no way he was doing this movie. When his agent called him to see what his reaction<br />

was, he told his agent he’s not going to do a movie where he kicks a pregnant<br />

woman in <strong>the</strong> stomach. His agent asked him if he read <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> scene. Alec<br />

told him he hadn’t bo<strong>the</strong>red. His agent told him to finish reading it. I guess that<br />

from that moment Alec was pulled into it.<br />

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

Industry Spotlight 19

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

20 American Independent<br />

Alec Baldwin once quipped that <strong>the</strong> budget for chewing gum on <strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong><br />

Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbour (2001) was equivalent to <strong>the</strong> entire cost <strong>of</strong> The<br />

Cooler. How did you manage to deliver such a stylish first feature, with a<br />

cast <strong>of</strong> well-known actors, on such a limited budget and schedule?<br />

With regards to <strong>the</strong> actors, we were able to attract <strong>the</strong>m due to <strong>the</strong> material –<br />

and most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m wanted to work with William H Macy. Everybody loves Bill and<br />

he proved to be a big talent magnet. He was <strong>the</strong> first to come onto <strong>the</strong> film – we<br />

wrote it for him, but it took him a long time to come around. He was tired <strong>of</strong><br />

playing ‘lovable losers’ and was looking to do more studio films. But producer<br />

Ed Pressman and I dogged Bill and his agent on a weekly basis, and wore <strong>the</strong>m<br />

down. I think Bill recognized <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>of</strong> doing <strong>the</strong> role and basically said, ‘If<br />

I’m going to never play ano<strong>the</strong>r loser again, let me at least play <strong>the</strong> Super Hero<br />

<strong>of</strong> losers.’ I knew that I didn’t have a great resumé when it came to directing<br />

before The Cooler so I meticulously storyboarded <strong>the</strong> entire film to be able to<br />

show <strong>the</strong> producers my vision for it. We were also helped enormously by <strong>the</strong><br />

location. Our line producer, Elliot Rosenblatt, found a casino in Reno, Nevada,<br />

that was undergoing renovations and made a deal with <strong>the</strong>m for us to shoot,<br />

and house our cast and crew in <strong>the</strong> hotel, while <strong>the</strong>y were tearing <strong>the</strong> place up.<br />

You made <strong>the</strong> crime thriller Running Scared for New Line Cinema. However,<br />

<strong>the</strong> film was shot on location in Prague to keep <strong>the</strong> costs down. When you<br />

are dealing with adult material that is <strong>of</strong>ten violent and potentially divisive,<br />

are than any significant differences between working with a Hollywood<br />

studio or an independent financier?<br />

Running Scared was as much an independent film as The Cooler. We were<br />

completely independently financed, and only sold <strong>the</strong> film to New Line in <strong>the</strong><br />

homestretch <strong>of</strong> post-production. Once New Line got involved, I feared that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

would inflict huge changes upon <strong>the</strong> film in terms <strong>of</strong> toning down <strong>the</strong> content.<br />

But Toby Emmerich and Bob Shaye were very respectful <strong>of</strong> what <strong>the</strong> film was,<br />

and I ended up only having to tweak a few moments for pacing issues. With<br />

regard to <strong>the</strong> budget and having to shoot <strong>the</strong> film in Prague, <strong>the</strong>re was just no<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r way to make <strong>the</strong> film with <strong>the</strong> limited budget we had. It would have cost<br />

us twice as much to shoot <strong>the</strong> film in New Jersey, where it’s actually set. We did<br />

shoot about a week in New Jersey and it cost a fortune – but I insisted on getting<br />

those shots to tie <strong>the</strong> film toge<strong>the</strong>r. I didn’t think a film set in New Jersey<br />

could be effectively pulled <strong>of</strong>f by shooting in Prague, but Toby Corbett, who<br />

has worked on all my films, designed some great sets and found <strong>the</strong> appropriate<br />

locations. But it wasn’t without its immense challenges and we spent a lot <strong>of</strong><br />

time keeping Prague out <strong>of</strong> our field <strong>of</strong> view.<br />

Running Scared is an extremely violent film, yet it received <strong>the</strong> R rating<br />

when submitted to <strong>the</strong> MPAA, whereas The Cooler was slapped with an<br />

NC-17 due to a few seconds <strong>of</strong> pubic hair. Do you see this as a reflection <strong>of</strong><br />

American society’s acceptance <strong>of</strong> violence as opposed to its almost puritanical<br />

attitude towards sex?<br />

I definitely agree that <strong>the</strong> MPAA is way more lenient when it comes to violence<br />

versus sexual situations. But if you’ll recall, <strong>the</strong>re were some pretty explicit fullfrontal<br />

shots in <strong>the</strong> strip club and <strong>the</strong> MPAA had no problem with <strong>the</strong>m. I had<br />

always feared that <strong>the</strong> MPAA might rate us NC-17 on The Cooler but I would have<br />

thought it was for <strong>the</strong> first sex scene, where Maria Bello puts her hands on Billy<br />

Macy’s goods after <strong>the</strong>y’ve just had sex. I never imagined it would have been for<br />

a two-second glimpse <strong>of</strong> pubic hair. Their explanation was that Macy’s head was<br />

right next to her pubic hair and that was a no-no – as in <strong>the</strong>y slam you for nudity

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Wayne Kramer.<br />

only when seen in context <strong>of</strong> performing a sexual act, ra<strong>the</strong>r than just strippers<br />

cavorting in a nightclub. The burden on receiving an NC-17 was that we had<br />

already completely finished <strong>the</strong> film and had already screened at a number <strong>of</strong> festivals.<br />

Usually, as in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> Running Scared, you present <strong>the</strong> MPAA with a work<br />

in progress and try to gauge if you’re going to have any rating’s issues, so that<br />

you can address <strong>the</strong>m without having to re-open <strong>the</strong> film once it’s already been<br />

mixed and <strong>the</strong> negative has been cut or, as is more likely <strong>the</strong>se days, once <strong>the</strong> film<br />

has already gone through <strong>the</strong> digital intermediate process. We had to reopen <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>fending reel in The Cooler, which cost Lions Gate quite a bit <strong>of</strong> money.<br />

Your most recent feature, Crossing Over, deals with <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> immigration<br />

in <strong>the</strong> USA. As you became a naturalized US citizen in 2000, how much<br />

<strong>of</strong> your own experiences are reflected in <strong>the</strong> film, and was <strong>the</strong> naturalization<br />

process simply a pr<strong>of</strong>essional necessity for you, as it is for <strong>the</strong> Alice<br />

Eve character in Crossing Over, or did it hold deeper meaning and personal<br />

significance?<br />

I pretty much identified with all <strong>the</strong> immigrant characters because, having been<br />

through <strong>the</strong> bureaucracy <strong>of</strong> legalization, I know how challenging – and arbitrary – it<br />

is. More specifically, as an artist trying to make his mark in <strong>the</strong> United States, it’s<br />

so important that you have access to working and raising financing in America.<br />

Speaking for myself, I always wanted to live in America and I always wanted to be<br />

an American. I grew up on American culture and felt spiritually connected to <strong>the</strong><br />

country and <strong>the</strong> opportunities that it promised, or should I say, advertised, to <strong>the</strong><br />

rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>. I have come close to achieving <strong>the</strong> ‘American dream’ and have <strong>the</strong><br />

privilege <strong>of</strong> making films that get seen all around <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>, as opposed to being<br />

just a ‘South African’ film-maker whose work is perceived as ‘foreign’. My attitude<br />

was always: why be a big fish in a small pond when you can be a big fish in <strong>the</strong><br />

biggest pond. I applied for naturalization <strong>the</strong> first day I became eligible because it<br />

Industry Spotlight 21

Directory <strong>of</strong> World Cinema<br />

22 American Independent<br />

was something I very much wanted and as an immigrant it’s <strong>the</strong> smart thing to do.<br />

I only travel on my US passport and don’t maintain a South African one at all. In<br />

fact, when I travel to South Africa I use my US passport and <strong>the</strong>y stamp me in with<br />

a tourist visa – which is pretty surreal. My intent with Crossing Over was to make a<br />

movie that wasn’t trying to solve America’s immigration problems but to give an<br />

honest portrayal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> diversity in <strong>the</strong> immigrant struggle to achieve legalization or<br />

naturalization – and <strong>the</strong> differences in each immigrant’s struggle.<br />

Your original cut reportedly featured a story strand involving Sean Penn<br />

which book-ended <strong>the</strong> film. Can you explain more about how <strong>the</strong>se scenes<br />

function alongside <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r narrative elements, and has removing this<br />

footage significantly altered <strong>the</strong> overall impact <strong>of</strong> Crossing Over?<br />

For me, this was <strong>the</strong> most damaging cut that Harvey Weinstein made to <strong>the</strong> film<br />

and <strong>the</strong> one I can least live with. The film originally opened with Sean Penn, playing<br />

a border patrol agent, driving his truck through a heavy storm on <strong>the</strong> eve <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Mexican holiday, Day <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dead. A young Mexican woman steps in front <strong>of</strong><br />

his truck, causing him to swerve into a ravine and total his truck. When he comes<br />

around, he finds her standing <strong>the</strong>re at his window. He climbs out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> truck and<br />

detains her. They both end up having to share <strong>the</strong> back <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> totalled border<br />

patrol truck because <strong>the</strong> rain is coming through <strong>the</strong> shattered front windshield.<br />

He warms to her over <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> night and <strong>the</strong>y end up showing photos<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir respective families. It appears that she has a young son who is waiting for<br />

her in Los Angeles. She keeps telling him, ‘You’re <strong>the</strong> one who’s going to help me<br />

cross over.’ He keeps insisting he’s a border patrol agent and he has a job to do.<br />

She just smiles at him and appears to fall asleep. He realizes that she’s not going<br />

anywhere in <strong>the</strong> storm and drifts <strong>of</strong>f to sleep as well. On screen it <strong>the</strong>n said: One<br />

week earlier. So now, <strong>the</strong> audience knows that whatever transpired in <strong>the</strong> border<br />

patrol truck between Penn and Braga was happening one week later. Toward <strong>the</strong><br />

end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> film, when <strong>the</strong> timeline has caught up with <strong>the</strong> events in <strong>the</strong> prologue,<br />

we find Sean Penn waking up <strong>the</strong> next morning to find Mireya missing from <strong>the</strong><br />

back <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> truck. He climbs <strong>the</strong> ravine looking for her, but she’s nowhere around<br />

and he just assumes he’s been played. He returns to <strong>the</strong> truck and slumps down,<br />

exhausted, against <strong>the</strong> back wheel, where he notices a piece <strong>of</strong> blanket sticking<br />

up from under <strong>the</strong> tire. He starts digging at it, revealing a decomposed human<br />

arm. The big reveal is that Mireya is buried underneath his truck and it was her<br />

ghost that he encountered <strong>the</strong> previous night on <strong>the</strong> Day <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dead (where it’s<br />

mythologized that <strong>the</strong> dead get to commune with <strong>the</strong> living). The storyline breaks<br />

with <strong>the</strong> tone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> film and adds a metaphysical component – and a<br />

transcendent quality to a sad storyline, which I felt was badly needed.<br />