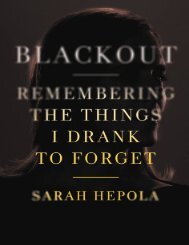

Blackout_ Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget - Sarah Hepola

I’m in Paris on a magazine assignment, which is exactly as great as it sounds. I eat dinner at a restaurant so fancy I have to keep resisting the urge to drop my fork just to see how fast someone will pick it up. I’m drinking cognac—the booze of kings and rap stars—and I love how the snifter sinks between the crooks of my fingers, amber liquid sloshing up the sides as I move it in a figure eight. Like swirling the ocean in the palm of my hand.

I’m in Paris on a magazine assignment, which is exactly as great as it sounds. I eat dinner at a

restaurant so fancy I have to keep resisting the urge to drop my fork just to see how fast someone will

pick it up. I’m drinking cognac—the booze of kings and rap stars—and I love how the snifter sinks

between the crooks of my fingers, amber liquid sloshing up the sides as I move it in a figure eight.

Like swirling the ocean in the palm of my hand.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

passed. “Have you met my new boyfriend?” I asked, one hand in his and ano<strong>the</strong>r around a cup of<br />

wine. “He’s cuuuuuute.”<br />

I made it <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> stage soon after, and people asked <strong>the</strong>ir questions. But <strong>the</strong> only part I remember is<br />

telling a very disjointed s<strong>to</strong>ry about Winnie-<strong>the</strong>-Pooh.<br />

When I woke <strong>the</strong> next morning, I felt shattered. I’d spent <strong>the</strong> past two years on a path of evolution<br />

—but here I was, crawling back under <strong>the</strong> same old rock. Lindsay and I walked <strong>to</strong> a coffee shop,<br />

where a guy on <strong>the</strong> patio recognized me. “Hey, you’re <strong>the</strong> drunk girl from last night,” he said, and my<br />

s<strong>to</strong>mach dipped. “You were hilarious!”<br />

I’ve heard s<strong>to</strong>ries of pilots who fly planes in a blackout, or people operating complicated<br />

machinery. And somehow, in this empty state, I had s<strong>to</strong>od on a stage, opened my subconscious, and<br />

hilarity fell out.<br />

I turned <strong>to</strong> my new boyfriend, <strong>to</strong> gauge his response. He was beaming. “You’re famous now,” he<br />

said, and squeezed my hand.<br />

I moved <strong>to</strong> Dallas <strong>to</strong> live with Lindsay and became <strong>the</strong> music critic at <strong>the</strong> Dallas Observer.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r stint on <strong>the</strong> good-times van. Club owners floated my tab, label owners bought me drinks. I<br />

was barely qualified for <strong>the</strong> job, and I faked my way through half my conversations, but <strong>the</strong> alcohol<br />

cushioned my mistakes. So did my boyfriend. Lindsay was a closet artist, who spent his evenings<br />

fiddling with song mixes and his days building databases. My new gig was an all-access pass <strong>to</strong> a<br />

world he’d only seen from a middle row. “I feel like <strong>the</strong> president’s wife,” he <strong>to</strong>ld me one night, after<br />

we spent <strong>the</strong> evening drinking with musicians. It didn’t even occur <strong>to</strong> me that might be a bad thing.<br />

My s<strong>to</strong>ries were gaining traction. I began writing in a persona that was like me, only drunker,<br />

more of a comedic mess. I made jokes about never listening <strong>to</strong> albums sent by aspiring bands, which<br />

was nei<strong>the</strong>r that funny nor that much of a joke. But people <strong>to</strong>ld me I was a riot. Maybe <strong>the</strong>y liked<br />

being reminded we were all screwed up, that behind every smile lurked a disaster s<strong>to</strong>ry. I began<br />

contributing <strong>to</strong> a scrappy online literary magazine called The Morning News. And in this tuckedaway<br />

corner of <strong>the</strong> Internet, where I could pretend no one was watching, I began <strong>to</strong> write s<strong>to</strong>ries that<br />

sounded an awful lot like <strong>the</strong> real me.<br />

People were watching, though. An edi<strong>to</strong>r at <strong>the</strong> New York Times sent me an email out of nowhere.<br />

She wondered if I’d like <strong>to</strong> contribute a piece sometime. They were looking for writers with voice.<br />

LINDSAY AND I made a good pair. He cooked elaborate dinners—lamb souvlaki, Thai lemongrass<br />

soup—as I dangled my feet from <strong>the</strong> kitchen counter, sipping wine from balloon glasses that were like<br />

fishbowls on a stick. He liked taking care of me, although we both liked not taking care of ourselves.<br />

Our lives felt like a Wilco song: The ashtray says you were up all night. Our lives felt like an Old<br />

97’s song: Will you sober up and let me down? Those were <strong>the</strong> songs we listened <strong>to</strong> while chainsmoking<br />

out a window, songs assuring us if you’re hurting and hungover, <strong>the</strong>n you’re doing it right.<br />

On Saturdays, we would heal ourselves with a greasy Mexican breakfast. Eggs, cheese, chorizo.<br />

Sometimes we wondered aloud if ours was <strong>the</strong> right path. Weren’t we supposed <strong>to</strong> be building<br />

something of meaning? We were 29 years old, <strong>the</strong> same age my mo<strong>the</strong>r was when she had me.<br />

Lindsay talked about his fa<strong>the</strong>r, who had moved all <strong>the</strong> way from Australia and started his own<br />

business. What had we done?<br />

But <strong>the</strong>n we’d go <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> bar and just repeat what we’d done <strong>the</strong> night before. The bartender poured