Housing the Future: Six Points

Six Points for Architects and Urbanists to Consider. Article published at the Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Chapter's CPD Event "How to House the Future", 11 April 2016. Text & illustrations by Amelyn Ng.

Six Points for Architects and Urbanists to Consider.

Article published at the Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Chapter's CPD Event "How to House the Future", 11 April 2016.

Text & illustrations by Amelyn Ng.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

HOUSING THE FUTURE:<br />

<strong>Six</strong> <strong>Points</strong> for Architects & Urbanists to Consider<br />

BROADSHEET BY AMELYN NG FOR AIA CPD EVENT, 11 APRIL 2016<br />

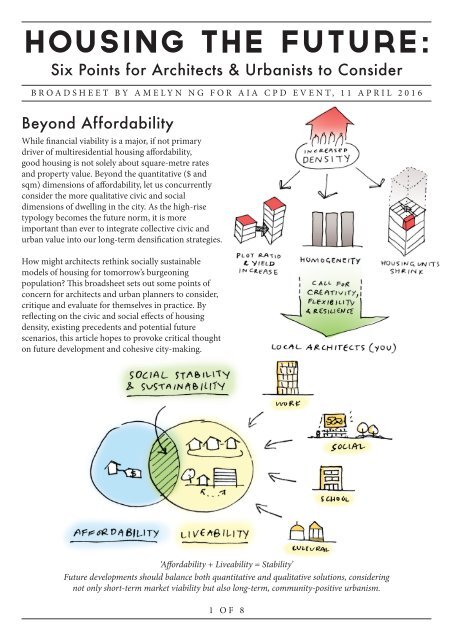

Beyond Affordability<br />

While financial viability is a major, if not primary<br />

driver of multiresidential housing affordability,<br />

good housing is not solely about square-metre rates<br />

and property value. Beyond <strong>the</strong> quantitative ($ and<br />

sqm) dimensions of affordability, let us concurrently<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> more qualitative civic and social<br />

dimensions of dwelling in <strong>the</strong> city. As <strong>the</strong> high-rise<br />

typology becomes <strong>the</strong> future norm, it is more<br />

important than ever to integrate collective civic and<br />

urban value into our long-term densification strategies.<br />

How might architects rethink socially sustainable<br />

models of housing for tomorrow’s burgeoning<br />

population? This broadsheet sets out some points of<br />

concern for architects and urban planners to consider,<br />

critique and evaluate for <strong>the</strong>mselves in practice. By<br />

reflecting on <strong>the</strong> civic and social effects of housing<br />

density, existing precedents and potential future<br />

scenarios, this article hopes to provoke critical thought<br />

on future development and cohesive city-making.<br />

‘Affordability + Liveability = Stability’<br />

<strong>Future</strong> developments should balance both quantitative and qualitative solutions, considering<br />

not only short-term market viability but also long-term, community-positive urbanism.<br />

1 OF 8

1. Common Ground<br />

Every apartment block is not an island.<br />

When designing towers for living in, <strong>the</strong> ground-plane<br />

condition should be addressed with utmost<br />

consideration for <strong>the</strong> wider urban fabric (beyond <strong>the</strong><br />

site’s boundaries).<br />

A typical residential tower has its back to <strong>the</strong><br />

street, often featuring a locked private lobby and<br />

underutilised lounge area. For security reasons it is<br />

made impermeable to <strong>the</strong> public. In this ubiquitous,<br />

default model of high-rise living, <strong>the</strong> resident is<br />

increasingly isolated from <strong>the</strong>ir broader environment.<br />

What if high-rise residential typologies were more<br />

aligned toward urban integration? The notion<br />

of public thoroughfare exists predominantly in<br />

commercial building such as office towers such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> examples below; why not extend this thinking to<br />

residential towers? What if, like mandatory setbacks,<br />

we speculated <strong>the</strong> establishment of a mandatory<br />

‘common-ground’ plane? By respecting <strong>the</strong> existing<br />

grain and civic adjacencies of inner-city plots, cities<br />

may be able to better uphold urban continuity in <strong>the</strong><br />

face of an increasing demand for housing stock.<br />

Conventional multi- residential ground plane:<br />

Impermeability denies public & breeds isolation<br />

Potential to democratise access: Establishing a ‘common<br />

ground’ plane across private developments<br />

HSBC Tower in Hong Kong by Foster + Partners.<br />

Photo by Eldan Goldenberg.<br />

Example of an ‘unlocked’ lobby. A corporate foyer and<br />

public thoroughfare on weekdays, <strong>the</strong> covered open<br />

space is appropriated by Filipina domestic workers every<br />

Sunday for social ga<strong>the</strong>rings and micro-trading.<br />

Urban Workshop in Melbourne CBD<br />

by John Wardle Architects.<br />

Photo by Irwinconsult.<br />

Example of a permeable lobby that ensures <strong>the</strong><br />

continuity of laneway networks in <strong>the</strong> city. It has a cafe<br />

and gallery archiving <strong>the</strong> site’s historical artefacts; and<br />

operates like a through public laneway.<br />

2 OF 8

2. Flexible Programming<br />

What if <strong>the</strong> choice to live in a high-rise city apartment<br />

did not necessarily mean having to give up<br />

neighbourliness, community and civic interaction?<br />

One concern with <strong>the</strong> locked-lobby approach (a<br />

feature of <strong>the</strong> prevailing high-rise residential model) is<br />

<strong>the</strong> perpetuation of gated vertical communities. While<br />

not immediately perceptible, <strong>the</strong> anti-social condition<br />

is already manifest in areas such as Southbank where<br />

chronic impermeability has resulted in insular living<br />

and street inactivity. This has a long-term impact on<br />

liveability and suburb desirability.<br />

and exchange will only grow more scarce. By<br />

encouraging space-sharing, space-adapting and<br />

space-letting we effectively multiply <strong>the</strong>se urban<br />

spaces. Ground-level vacancy may in turn be<br />

reduced, over time restoring street life and mitigating<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘ghost-streetscape’ effect that currently haunts<br />

tower-suburbs such as Southbank and <strong>the</strong> Docklands.<br />

The progressive reevaluation of our living norms will<br />

undoubtedly come with challenges, particularly in<br />

operational planning, security and body-corporate<br />

maintenance and overall financial viability. However<br />

<strong>the</strong>se recalibrations should be seen as “growing pains”<br />

<strong>Future</strong> apartment towers should provide a robust and<br />

adaptable interface between public and private realms,<br />

embracing moments of overlap instead of wholly<br />

segregating private from public zones.<br />

The potential to transform static resident-only spaces<br />

(e.g. foyers, receptions, privatised landscaping) into<br />

dynamic, active platforms exists across <strong>the</strong> various<br />

stages of a building’s life: from pre-construction<br />

temporary site activations to post-occupancy<br />

operations and management. Time-sensitive<br />

programming might be seen as a parallel to <strong>the</strong><br />

‘open-plan’ model of <strong>the</strong> last century: radical in its<br />

programmatic flexibility at <strong>the</strong> time of proposal, but<br />

upon refinement large-scale adoption, it has become<br />

<strong>the</strong> modus operandi for architects globally.<br />

Assemble, an emerging residential developer focused<br />

on small-footprint living, has based <strong>the</strong>ir current office<br />

on Roseneath Street, Clifton Hill- <strong>the</strong> site of <strong>the</strong>ir first<br />

multi-residential project in partnership with Wulff<br />

Projects and Icon Co. O<strong>the</strong>r parts of <strong>the</strong> private site are<br />

leased out to creative enterprises such as local clothing<br />

label Kloke, while its vast ground-level warehouse<br />

space is regularly activated by design presentations,<br />

exhibitions and public events such as <strong>the</strong> up-coming<br />

Brutalist Block Party in collaboration with Open<br />

House Melbourne. Even before any construction has<br />

begun, community is already being created upfront<br />

and on-site, where future occupants of <strong>the</strong> new project<br />

get to meet potential neighbours and familiarise<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves with <strong>the</strong> location. This is one such example<br />

of flexible cross-programming being used to establish<br />

resilience and social capital.<br />

In light of our city’s projected residential growth,<br />

public greenspace as well as areas for civic ga<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

3 OF 8

3. Demographic- &<br />

Income-Mixed <strong>Housing</strong><br />

Developed cities across <strong>the</strong> globe should be pressed to<br />

reassess <strong>the</strong>ir priorities: on one hand to accommodate<br />

<strong>the</strong> displaced and marginalised, or on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

continue to advance market-driven economic<br />

interests. In many cases <strong>the</strong> latter has been prioritised,<br />

amplifiying disparities in its population’s wealth, race,<br />

class and religion, and heightening political and social<br />

tensions.<br />

While <strong>the</strong>re are no easy answers to <strong>the</strong>se questions,<br />

we should be cognizant of <strong>the</strong>se urban dilemmas and<br />

think laterally about more amenable, intelligent pieces<br />

inserted into <strong>the</strong> urban tapestry- adjusting with <strong>the</strong><br />

city ra<strong>the</strong>r than divorcing itself- where inhabitants may<br />

productively engage with and contribute to trade and<br />

social capital of society as a whole.<br />

Large-scale single-stage developments that aim to<br />

provide social housing en-masse pose <strong>the</strong> danger of<br />

fragmentation. One is reminded of our commission<br />

flats, Brutalist social-housing blocks of <strong>the</strong> sixties, and<br />

in more extreme cases, <strong>the</strong> ‘ghetttoisation’ of uniformly<br />

developed residential zones that pepper remote<br />

areas around <strong>the</strong> world; Modernist slum-suburbs<br />

with increased work travel distances and heightened<br />

segregation between higher and lower income groups.<br />

Quick-fix ‘out-of-sight’ developments are contributing<br />

significantly to stigmatisation and ‘o<strong>the</strong>ring’.<br />

This raises not just a sociopolitical problem but also an<br />

architectural and urban one. Cross-cultural tolerance<br />

and integration are not simply <strong>the</strong> concern of <strong>the</strong><br />

socio-economic or policymakers, but exists also in <strong>the</strong><br />

domain of <strong>the</strong> architect and urban professional.<br />

Beyond social and indigenous housing initiatives, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

also is <strong>the</strong> contentious case of refugee housing- an area<br />

of great public debate in contemporary politics and<br />

social work but not so much in architectural circles.<br />

This also forms a touch-point of residential affordability<br />

and housing for <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

4 OF 8

4. Communal Living<br />

Current models of inner-city living should continue<br />

to diversify <strong>the</strong>ir offerings and evolve in accordance<br />

with future living and working lifestyles. Ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

a one-size-fits-all approach, <strong>the</strong> residential property<br />

market and its associated housing policies should aim<br />

to be more flexible, responsive and inclusive overall.<br />

The resurgence in co-housing initiatives such as<br />

Melbourne’s Urban Coup reflects an increasing desire<br />

for community-centric owner-occupier housing<br />

that is still amenable and close to <strong>the</strong> city centre. An<br />

increasing number of prospective purchasers are<br />

hoping to have more say in <strong>the</strong> design of <strong>the</strong>ir property<br />

if <strong>the</strong>y will be living <strong>the</strong>re long-term: that is, <strong>the</strong>y wish<br />

to invest not just for short-term financial gains but<br />

also qualitative returns that will see <strong>the</strong>m through <strong>the</strong><br />

various phases of life. Committed owner-developer<br />

groups such as Urban Coup allows such choices to be<br />

made.<br />

Perhaps more architects should be having <strong>the</strong>se<br />

open-ended, nebulous conversations: is it currently<br />

feasible, for example, to raise a family or age-in-place<br />

in an apartment tower? How can we future-proof<br />

vertical communities from demographic stratification,<br />

and ensure yields don’t all skew towards 1-bedroom<br />

student shoebox apartments?<br />

The decision to live communally or ‘grow old<br />

with your apartment’ should not be a reluctant<br />

compromise on location, access, tenure type, price or<br />

choice. Alternative models should be embraced and<br />

investigated to avoid homogenous development or<br />

income-bracket favouritism.<br />

This apartment-and-townhouse project champions<br />

housing diversity in an o<strong>the</strong>rwise cookie-cutter<br />

multi-residential development climate.<br />

The “assemble your home” concept gives purchasers <strong>the</strong><br />

ability to tailor <strong>the</strong>ir dwelling to financial and functinal<br />

needs, providing a choice of standard or premium<br />

options for <strong>the</strong>ir kitchen, bathroom and flooring, and a<br />

range of extras such as a dog door, flexi-room, fold-down<br />

bed or kid’s bath. There is a more nuanced palette of<br />

choice on how individuals wish to live than traditional<br />

models, while balancing construction efficiency, site<br />

density and overall financial viability.<br />

WestWyck Ecovillage, Brunswick.<br />

Stage 1 by Peter Mills & Michael McKenna.<br />

Stage 2 by Multiplicity.<br />

Image by ArchitectureAU.<br />

Westwyck comprises a cluster of 30 apartments<br />

and townhouses around and within <strong>the</strong> former<br />

Brunswick West Primary School. The units have<br />

been developed in stages over a decade and are fitted<br />

with solar panels, rainwater harvesting, grey-water<br />

recycling and above-standard insulation, as well as<br />

common landscaping areas and vegetable gardens. Its<br />

affordable, ecological and community focus has drawn<br />

much interest by like-minded locals and continues to<br />

outperform itself in <strong>the</strong> housing market.<br />

With a mission to repurpose <strong>the</strong> vacant schoolhouse,<br />

developers Lorna Pitt & Mike Hill (also committed<br />

owner-occupiers) have taken a long-term view on<br />

<strong>the</strong> housing project and are personally invested in<br />

community building. Recognising <strong>the</strong> importance of<br />

122 Roseneath St, Clifton Hill by Icon Co, Wulff Projects good design, <strong>the</strong>y also partnered with similarly-aligned<br />

& Assemble. (currently in design documentation phase). local architects (named above) for creative heritage work<br />

Image by Assemble.<br />

using cost-effective, sustainably sourced materials.<br />

5 OF 8

5. “Amenity-pooling”<br />

A key factor in housing liveability and affordability<br />

is <strong>the</strong> access to civic services: be it physical access<br />

to shops, parks and schools, or financial access<br />

an apartment’s body corporate fees. In a future of<br />

increasingly privatised superblocks and towers,<br />

designers and developers should to democratise<br />

spaces where possible, through <strong>the</strong> localised sharing of<br />

amenities between adjacent residential blocks and with<br />

its broader community.<br />

Consider <strong>the</strong> notion of car-pooling. When a resource<br />

is shared by actively coordinating schedules with each<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r, utility and social benefits are maximised while<br />

energy expenditure is minimised. In <strong>the</strong> same vein,<br />

high-rise “amenity-pooling” could streamline <strong>the</strong><br />

unnecessary number of identical programs such as<br />

pools, gyms and function rooms (refer diagram below;<br />

<strong>the</strong>se are typically energy-intensive), reduce <strong>the</strong> overall<br />

ecological footprint and streng<strong>the</strong>n neighbourly<br />

relations between tower residents.<br />

Scenarios where “amenity-pooling” could occur in<br />

high-rise apartments:<br />

(a) At ground level, to restore <strong>the</strong>se traditionally public<br />

programs to full public access.<br />

(b) At intermediate levels, with residential bridges<br />

linking ‘actively coordinated’ towers in series or<br />

parallel. Stephen Holl’s Linked Hybrid buildings in<br />

Beijing come to mind.<br />

Current situation: Private-access-only amenity<br />

(inaccessible and insular) that exists as duplicates from<br />

tower to tower (unsustainable).<br />

6 OF 8<br />

Linked Hybrid Mixed-Use Complex in Beijing by Steven<br />

Holl. Image above by Dezeen.<br />

Sketch below by Steven Holl.

5. “Amenity-pooling”<br />

Continued<br />

(c) At rooftop level, where <strong>the</strong> best views and light<br />

in <strong>the</strong> building could be reserved for communal<br />

activities, instead of plant room or penthouse decks.<br />

While this proposal seems a huge stretch from our<br />

current ways of doing housing, <strong>the</strong> topic certainly<br />

warrants fur<strong>the</strong>r research attention, particularly since<br />

<strong>the</strong> surge in housing density wtihin already built-up<br />

areas such as <strong>the</strong> CBD will place immense pressures on<br />

existing civic infrastructure.<br />

As land becomes scarcer and more subservient to<br />

yield, <strong>the</strong>re will be fewer parks, sports courts and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r public open spaces at ground level. Can we<br />

rethink engineering and functional standards so that<br />

<strong>the</strong> valuable roof plane can be appropraited for civic<br />

advantage?<br />

To illustrate, let us consider a public school which<br />

admits students on proximity-based acceptance. If<br />

<strong>the</strong> neighbourhood is gentrified to accommodate<br />

population growth and its residents double, <strong>the</strong> same<br />

school will not have enough places and support<br />

services, and unless it upgrades, expands or hires more<br />

staff, its admissions has to be more selective.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong>se residential ‘amenities’ in<br />

question need not only be limited to <strong>the</strong> luxury<br />

triumvirate of gym-pool-sauna. Why not consider <strong>the</strong><br />

“amenity-pooling” of primary schools, childcare, aged<br />

care services, bookable meeting rooms, doctor’s clinics,<br />

home-office consultancies and so forth?<br />

7 OF 8<br />

Would families <strong>the</strong>n be discouraged from living in<br />

<strong>the</strong>se denser areas simply because <strong>the</strong>ir children have<br />

a lower chance of getting accepted into a school? These<br />

are <strong>the</strong> everyday scenarios and flow-on-effects we have<br />

to be conscious of.<br />

If nothing is done to improve and expand <strong>the</strong>se<br />

civic programs to meet <strong>the</strong> needs of a burgeoning<br />

population, residential liveability and affordability for<br />

each of those occupants will naturally suffer.<br />

As design professionals we are responsible not just<br />

for our allotted site for <strong>the</strong> duration of our services,<br />

but also for <strong>the</strong> shaping of our urban domain as<br />

an accretive whole. The civic condition of a city<br />

has a direct feedback loop into its housing market.<br />

Let us continue to push <strong>the</strong> boundaries of creative<br />

programming, democratic accessibility and civic<br />

amenity in each project, over time incrementally<br />

benefitting urban life and its symbiotic relationship<br />

with private residential life.

6. Self-Governance<br />

Security is one of <strong>the</strong> key factors in choosing one<br />

place to live over ano<strong>the</strong>r. It is inextricable from<br />

<strong>the</strong> liveability-affordability-stability venn diagram;<br />

a suburb that rates lower on residential security<br />

typically reflects lower property prices than <strong>the</strong>ir safer<br />

counterparts. If a percieved threat to one’s security<br />

is sustained and unsolved, <strong>the</strong> public perception of a<br />

that neighbourhood can quickly plummet along with<br />

property desirability. From <strong>the</strong>n on <strong>the</strong> stigma is often<br />

difficult to remediate, even with <strong>the</strong> promise of new<br />

building stock.<br />

Is <strong>the</strong> self-governed model scaleable ? How might<br />

such thinking apply not just to medium-density but<br />

high-density dwellings? What is <strong>the</strong> (fine) line between<br />

passive surveillance and overlooking?<br />

However difficult <strong>the</strong> questions are on housing <strong>the</strong><br />

future, <strong>the</strong>y will not go away with quick-fixes nor by<br />

turning a blind eye to <strong>the</strong> civic condition. <strong>Housing</strong><br />

is being developed at an unprecedented pace before<br />

our eyes, and this generation of architects have <strong>the</strong><br />

requisite creative and professional skills to rethink and<br />

reshape its effects on tomorrow, one dwelling at a time.<br />

Fundamentally, residents want to feel safe and<br />

protected in <strong>the</strong>ir home. To a degree architecture and<br />

urbanism can reduce <strong>the</strong> risk of dangerous situations<br />

by designing safe and resilient neighbourhoods from<br />

<strong>the</strong> outset.<br />

Urbanist Jane Jacobs’ ‘eyes on <strong>the</strong> street’ still holds true<br />

today; architects should adopt passive surveillance as<br />

first principles in <strong>the</strong> design of housing, before relying<br />

on surveillance technologies and heavily policed<br />

reception areas (refer diagrams below).<br />

In many ways, self-governed ‘common security’<br />

imbues a sense of collective responsibility that passive<br />

‘private security’ system is unable to offer.<br />

Heller Street Park & Residences in Brunswick by <strong>Six</strong><br />

Degrees Architects. Photo by Patrick Rodriguez.<br />

Example of passive surveillance, neighbour security<br />

and effective public-to-private gradient via shared<br />

greenspace. This urban gesture extends beyond <strong>the</strong> site,<br />

stitching dwellings back into <strong>the</strong> local fabric.<br />

Amelyn is a design-focused researcher from Melbourne,<br />

with a deep interest in civic agency and socially responsive<br />

infrastructures. She believes architecture is at once a physical<br />

practice, critical discourse and catalyst for social change.<br />

She recently presented a speculative paper on refugee housing<br />

at <strong>the</strong> AMPS housing conference in Nicosia, Cyprus 2016;<br />

<strong>the</strong> project has also been exhibited in Melbourne and in<br />

Madrid as part of Archiprix International 2015. Her M.Arch<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis, a critique of laissez-faire privatisation and consumer<br />

behaviours in Southbank, was awarded <strong>the</strong> 2014 Edward &<br />

Penelope Billson Prize and Ernest Fooks Memorial Award.<br />

Her writing has been recently published by <strong>the</strong> Australian<br />

Design Review, Architect Victoria, Assemble Papers,<br />

Architecture & Design, FLOG and Inflection Journal.<br />

While working towards her architect’s registration at<br />

Fieldwork and Assemble, she hopes to examine <strong>the</strong> potentials<br />

of opportunistic urbanism through ongoing research and<br />

regular contributions to architectural publication.<br />

8 OF 8