Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Mainland 12 Monday, March 21, 2016<br />

The San Juan Daily <strong>Star</strong><br />

Where Merrick Garland Stands: A<br />

Close Look at His Judicial Record<br />

By ADAM LIPTAK<br />

Judge Merrick B. Garland, President Obama’s<br />

Supreme Court nominee, has achieved a<br />

rare distinction in a polarized era. He has<br />

sat on a prominent appeals court for almost<br />

two decades, participated in thousands of<br />

cases, and yet earned praise from across the<br />

political spectrum.<br />

A look at a substantial sample of his opinions<br />

starts to supply some answers about<br />

how he managed this unlikely feat. His writings<br />

reflect an able and modest judge with<br />

a limited conception of his role working on a<br />

docket largely lacking in cases on controversial<br />

social issues.<br />

His most charged cases, involving national<br />

security and campaign finance, were as<br />

likely to disappoint liberals as to please them.<br />

He has repeatedly voted against detainees at<br />

Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and he joined the Citizens<br />

United decision that gave rise to “super<br />

PACs.”<br />

In more run-of-the-mill cases, he was apt<br />

to side with workers claiming employment<br />

discrimination and against criminal defendants<br />

who said their rights had been violated.<br />

Throughout, Judge Garland’s opinions<br />

were models of judicial craftsmanship — unflashy,<br />

methodically reasoned, attentive to<br />

precedent and tightly rooted in the language<br />

of the governing statutes and regulations. He<br />

appears to apply Supreme Court precedents<br />

with punctilious fidelity even if there is reason<br />

to think he would have preferred a different<br />

outcome and even where other judges<br />

might have found room to maneuver.<br />

“He’s been a lower-court judge and acted<br />

like one for these past 19 years,” said Neal K.<br />

Katyal, a former acting United States solicitor<br />

general.<br />

But that also means that Judge Garland’s<br />

opinions provide only glimpses of how he<br />

would vote and write if he overcomes Republican<br />

objections to fill the seat left vacant by<br />

the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.<br />

Judge Garland’s court, the United States<br />

Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia<br />

Circuit, is prestigious but has a limited and<br />

idiosyncratic docket tilting toward administrative<br />

law. The court seldom confronts the volatile<br />

controversies that routinely engage the<br />

justices, like abortion, affirmative action, gay<br />

rights and the death penalty.<br />

The D.C. Circuit does get a steady diet of<br />

cases on efforts to combat terrorism and on<br />

the role of money in politics, and they illustrate<br />

Judge Garland’s moderate, case-by-case<br />

approach.<br />

He has given mixed signals in cases concerning<br />

detainees held at Guantánamo. In<br />

2003, he joined a unanimous three-judge panel<br />

in Al Odah v. United States, which ruled<br />

that men held at the prison could not challenge<br />

their detentions in federal court based on a<br />

1950 Supreme Court precedent. The Supreme<br />

Court later rejected the appeals court’s reasoning.<br />

In 2008, Judge Garland wrote an opinion<br />

for a unanimous three-judge panel concluding<br />

that a military tribunal had wrongly classified<br />

Huzaifa Parhat, a Chinese Uighur, as an enemy<br />

combatant. In the process, Judge Garland<br />

rejected an intelligence assessment.<br />

“The government suggests that several of<br />

the assertions in the intelligence documents<br />

are reliable because they are made in at least<br />

three different documents,” he wrote. “We are<br />

not persuaded. Lewis Carroll notwithstanding,<br />

the fact that the government has ‘said it<br />

thrice’ does not make an allegation true.”<br />

In 2014, Judge Garland joined a decision<br />

upholding a policy at Guantánamo that<br />

allowed guards to probe the genitals of detainees<br />

seeking to meet with their lawyers.<br />

Supreme Court precedent required great deference<br />

to prison officials’ assessments of security<br />

protocols, the court said.<br />

“The new search procedures promote the<br />

safety of the guards and inmates by more<br />

effectively preventing the hoarding of medication<br />

and the smuggling of dangerous contraband,”<br />

the opinion concluded.<br />

In campaign finance cases, too, Judge Garland<br />

followed Supreme Court precedent in<br />

ways that sometimes frustrated liberals and<br />

sometimes cheered them.<br />

He joined a unanimous opinion in SpeechNow.org<br />

v. Federal Election Commission,<br />

a 2010 ruling from a nine-judge panel that<br />

allowed unlimited contributions to “super<br />

PACs,” nominally independent groups that<br />

support political candidates. The logic of the<br />

Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United<br />

required the move, the appeals court’s opinion<br />

said, transforming the political landscape.<br />

Citizens United concerned only independent<br />

spending by corporations and unions,<br />

not rich people. But it said that there was only<br />

one justification for restricting political spending:<br />

quid pro quo corruption akin to bribery.<br />

It added that independent spending could never<br />

satisfy that standard.<br />

While Judge Garland unhesitatingly extended<br />

Citizens United when he believed its logic<br />

compelled him to do so, he was unwilling to<br />

push further than it required. In July, writing<br />

for a unanimous 11-member panel in Wagner<br />

v. Federal Election Commission, Judge Garland<br />

upheld a ban on campaign contributions<br />

from federal contractors, saying the interest in<br />

preventing corruption that survived Citizens<br />

United warranted the move.<br />

That both cases were unanimous suggests<br />

that the D.C. Circuit works hard to achieve<br />

consensus and confirms findings by political<br />

scientists that ideological voting is less common<br />

on federal appeals courts than on the Supreme<br />

Court.<br />

Judge Garland’s voice is most vivid in his<br />

infrequent dissents. In 2009, for instance, in<br />

Saleh v. Titan Corp., he said the majority had<br />

gone badly astray in barring a suit against<br />

American military contractors by victims of<br />

abuse at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.<br />

“The plaintiffs in these cases allege that<br />

they were beaten, electrocuted, raped, subjected<br />

to attacks by dogs and otherwise abused<br />

by private contractors working as interpreters<br />

and interrogators,” he wrote, adding that both<br />

the Bush and Obama administrations, along<br />

with Congress, “have repeatedly and vociferously<br />

condemned the conduct at Abu Ghraib<br />

as contrary to the values and interests of the<br />

United States.”<br />

The majority, Judge Garland wrote, had<br />

to ignore all of that to fashion “the protective<br />

cloak it has cast over the activities of private<br />

contractors.”<br />

Laurence H. Tribe, a law professor at Harvard,<br />

said Judge Garland’s dissenting opinion<br />

was “particularly admirable.”<br />

“That dissent is a fine example of an opinion<br />

that combines impeccable legal analysis<br />

with a deep sense of humanity,” he said.<br />

Judge Garland served as a law clerk in<br />

1978 and 1979 to Justice William J. Brennan Jr.,<br />

the liberal icon. But there is little in his own<br />

opinions to suggest that he would bring a<br />

similarly strong liberal voice to the Supreme<br />

Court.<br />

Even assuming Judge Garland’s appellate<br />

decisions are a good indication of how he<br />

would vote on the Supreme Court, the key<br />

question is not where he stands in some abstract<br />

sense but where he would fit into the<br />

ideological array on the current court.<br />

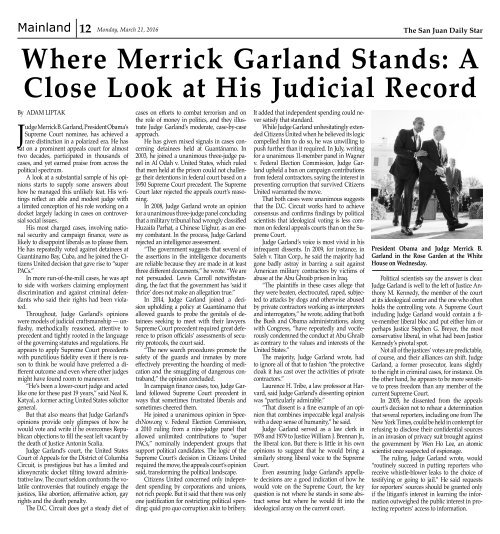

President Obama and Judge Merrick B.<br />

Garland in the Rose Garden at the White<br />

House on Wednesday.<br />

Political scientists say the answer is clear.<br />

Judge Garland is well to the left of Justice Anthony<br />

M. Kennedy, the member of the court<br />

at its ideological center and the one who often<br />

holds the controlling vote. A Supreme Court<br />

including Judge Garland would contain a five-member<br />

liberal bloc and put either him or<br />

perhaps Justice Stephen G. Breyer, the most<br />

conservative liberal, in what had been Justice<br />

Kennedy’s pivotal spot.<br />

Not all of the justices’ votes are predictable,<br />

of course, and their alliances can shift. Judge<br />

Garland, a former prosecutor, leans slightly<br />

to the right in criminal cases, for instance. On<br />

the other hand, he appears to be more sensitive<br />

to press freedom than any member of the<br />

current Supreme Court.<br />

In 2005, he dissented from the appeals<br />

court’s decision not to rehear a determination<br />

that several reporters, including one from The<br />

New York Times, could be held in contempt for<br />

refusing to disclose their confidential sources<br />

in an invasion of privacy suit brought against<br />

the government by Wen Ho Lee, an atomic<br />

scientist once suspected of espionage.<br />

The ruling, Judge Garland wrote, would<br />

“routinely succeed in putting reporters who<br />

receive whistle-blower leaks to the choice of<br />

testifying or going to jail.” He said requests<br />

for reporters’ sources should be granted only<br />

if the litigant’s interest in learning the information<br />

outweighed the public interest in protecting<br />

reporters’ access to information.