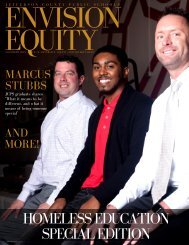

ENVISION EQUITY DECEMBER 2015

Special homeless edition.

Special homeless edition.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1<br />

Photo, Getty Images

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

3<br />

Children and Youth Experiencing Homelessness. An Introduction to the topic.<br />

By Julie McCullough, University of Louisville (UofL) Practicum Student<br />

Family homelessness has challenged the United States<br />

for over thirty years. However many do not visualize<br />

homeless families and children living in our communities.<br />

The reality is that a large number homeless<br />

individuals are under the age of 18. Some of them<br />

are a part of families experiencing homelessness,<br />

while others are on their own.<br />

The first national plan for ending homeless was<br />

release on 2010 and set specific goals with the<br />

purpose of ending chronic and veteran homeless by<br />

<strong>2015</strong> and ending family and children homelessness by<br />

2020. Since the release the number of chronic and<br />

veteran homeless has been reduced but not the<br />

number of homeless families and children.<br />

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (42<br />

U.S.C. § 11431 et seq.) is a federal law that addresses<br />

the needs of homeless people, including the<br />

educational needs of children and youth. This edition<br />

provides basic information about the scope of the<br />

problem, the impact of homelessness on education,<br />

and the rights of children and youth to a public<br />

education. In addition some articles are designed to<br />

provide resources for advocates in how to support<br />

homeless students and their families.<br />

Scope of the Problem<br />

Approximately 2.5 million children are estimated to<br />

experience homelessness each year (National Center<br />

on Family Homelessness, 2014). Of those 1.2 million<br />

are students in the public education system (National<br />

Center for Homeless Education (NCHE), 2014). In<br />

Kentucky alone, this number has grown as high as<br />

almost 28,000 students, and in Jefferson County there<br />

were 6,448 students that experienced homelessness<br />

during the 2014-<strong>2015</strong> school year (Kentucky<br />

Department of Education (KDE) <strong>2015</strong>). These<br />

students will encounter several barriers that will<br />

prevent them from accessing the Kentucky Core<br />

Academic Standards.<br />

According to, Miller<br />

(2009) ten percent of<br />

children whose families<br />

are poor will experience<br />

homelessness in a given<br />

year. Furthermore,<br />

these children will come<br />

from a variety of racial<br />

and ethnic backgrounds and can be found in urban,<br />

suburban, and rural areas throughout the country.<br />

In 2013, approximately forty-eight percent of<br />

homeless families living in shelters were black, twentythree<br />

percent were white, and another twenty-three<br />

percent were Hispanic (Child Trends Data Bank,<br />

<strong>2015</strong>). However, as depicted in figure one, only<br />

sixteen percent of students that are homeless live in<br />

shelters. Seventy-five percent of students<br />

experiencing homelessness are doubled-up living with<br />

relatives or another family. Six percent of students<br />

that are homeless live in hotels or motels, and three<br />

percent of students experiencing homelessness are<br />

unsheltered (National Center for Homeless Education<br />

(NCHE), 2014). Therefore, it can be difficult to<br />

identify homeless students and their specific<br />

backgrounds. In Jefferson County alone seventy<br />

percent of students experiencing homelessness are<br />

living doubled up with family members or friends<br />

often making it difficult to identify students that are<br />

truly in need of support.<br />

Academic effect/impact of Homelessness<br />

Students experiencing homelessness are highly mobile<br />

and face multiple barriers to academic achievement.<br />

Continued on next page

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

According to national data, in one year, forty-one<br />

percent of children experiencing homelessness will<br />

attend two different schools, and twenty-eight percent<br />

of these children will attend three or more different<br />

schools. Unfortunately, each new move can set a<br />

student back four to six months academically. As a<br />

result, students that are homeless are more than twice<br />

as likely to repeat a grade as compared to their nonhomeless<br />

counterparts (Miller, 2009). In addition,<br />

twenty-five percent of homeless students will fail at<br />

least one class, forty-two percent are in jeopardy of<br />

failing classes, and less than twenty-five percent will<br />

graduate high school (Sulkowski & Joyce-Beaulieu,<br />

2014). These numbers are a little better in JCPS,<br />

where approximately sixty-three percent of homeless<br />

students graduated high school in 2014 compared to<br />

seventy-nine percent of their peers. In terms of<br />

academic scores, thirty-three percent of homeless<br />

students in Jefferson County tested proficient or<br />

higher in reading compared to forty-eight percent of<br />

their non-homeless peers. Likewise, twenty-eight<br />

percent of homeless students scored proficient or<br />

higher in math compared to forty percent of their<br />

peers (Figure 2 & 3). These scores are similar to<br />

those experienced by homeless students at the<br />

national and state level as depicted in the graphs<br />

below (Figure 4 & 5).<br />

predominately D’s and F’s (Children’s Defense Fund,<br />

2010). High drop-out rates have also been attributed<br />

to mental illness in children. According to the<br />

National Alliance on Mental Illness (<strong>2015</strong>),<br />

“approximately fifty percent of students age fourteen<br />

and older with mental illness drop out of high<br />

school”. This is a significant problem for students<br />

that are homeless, of which nearly half will<br />

experience depression, anxiety, and aggression<br />

(Biggar, 2001). Due to the mobility, academic<br />

challenges, attendance barriers, trauma, and<br />

emotional challenges these students face it is critical<br />

for schools to not only meet, but exceed the standards<br />

of the McKinney-Vento law. This will help children<br />

by ensuring school is at least one place a child can<br />

obtain security and stability.<br />

Educational Rights under the McKinney-Vento<br />

Homeless Act<br />

The McKinney-Vento Act provides rights and<br />

protections for homeless students. The legislation’s<br />

main theme is to ensure educational stability and<br />

continuity, including allowing homeless children have<br />

the right to remain in one, stable school environment<br />

and provide continuous access to educational support<br />

and services. It provides the right to immediate<br />

enrollment and full participation in school activities<br />

for homeless students.<br />

Students have the right to:<br />

4<br />

Social, Emotional, Behavioral effect of Homelessness<br />

Research indicates that homeless children are twice<br />

as likely to experience social and emotional problems<br />

(Sulkowski, 2014). These emotional and behavioral<br />

disorders can cause a significant barrier to academics.<br />

Nelson et al. (2004), found that eighty-three percent<br />

of students with an emotional or behavioral disorder<br />

scored below average in math, reading, and writing.<br />

Furthermore, twenty-five percent of children with<br />

emotional or behavioral problems have reported<br />

having difficulty in school, and up to fourteen percent<br />

of high school students in this situation receive<br />

Receive a free, appropriate public education.<br />

Enroll in school immediately, even if lacking<br />

documents normally required for enrollment.<br />

Enroll in school and attend classes while the<br />

school gathers needed documents.<br />

Enroll in the local attendance<br />

area school or continue<br />

attending their school of origin<br />

(the school they attended when<br />

permanently housed or the<br />

school in which they were last<br />

enrolled),<br />

Receive transportation to and from the school<br />

of origin, if requested by the parent,<br />

guardian, or unaccompanied youth.<br />

Receive educational services comparable to<br />

those provided to other students.<br />

Get access to due progress and dispute<br />

resolution.<br />

Source: U.S.C. §11432(g)(3)(H).

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

This story was published in May <strong>2015</strong> by JCPS students Chris Roussell and John Jean-Marie. They earned top awards from the<br />

National Scholastic Press Association (NSPA) for their hard work.<br />

5<br />

Above, JCPS student Giraud Drake, waits for his<br />

school bus. Photo, Erin Waggon<br />

In eighth-grade, thirteen yearold<br />

Giraud Drake (11, HSU)<br />

entered his new home in<br />

Newburg; the third of what<br />

would be five homes since<br />

moving to Kentucky. Upon<br />

entering, goosebumps crept up<br />

on his skin — a reminder of one<br />

of the simple luxuries his<br />

mother had hoped to provide: a<br />

fully-heated home. Because she<br />

was an African American<br />

woman, she was constantly<br />

discriminated against while<br />

working construction, causing<br />

her to make less money than her<br />

male counterparts. The section<br />

eight housing she was able to<br />

secure lacked both adequate<br />

heating and lighting.<br />

Drake, exhausted after the fortyfive<br />

minute long TARC ride<br />

home from football practice,<br />

immediately headed to the<br />

kitchen table to start his<br />

homework. Cloaked in darkness,<br />

Drake squinted to see papers<br />

just a few inches from his face.<br />

The only remaining source of<br />

light, left over from wire<br />

complications, seeped into the<br />

room from upstairs. The<br />

complications from faulty wiring<br />

only allowed one level of the<br />

house to be lit at a time. With<br />

his mother occupying the<br />

upstairs, Drake had to finish his<br />

homework in the near dark.<br />

After finishing his homework,<br />

Drake headed upstairs to his<br />

room. Boxes of clothing lined<br />

the bedroom wall, untouched<br />

from their last move. Drake,<br />

who knew all too well the<br />

likeliness of relocation, saved<br />

himself the pain of packing up<br />

his belongings once again. As he<br />

sat alone in his room, Drake<br />

reflected to himself. ‘Nothing is<br />

right. Nothing is right. Nothing<br />

is right,’ he thought.<br />

Drake is not alone. There are<br />

hundreds of thousands of<br />

students just like him around the<br />

nation.<br />

According to the National<br />

Center on Family Homelessness<br />

(NCFH), 1.6 million children<br />

will experience homelessness<br />

Continued on next page

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

every year in the United States<br />

due to issues including<br />

economic hardship and family<br />

conflict.<br />

Safe Horizon, a national victim<br />

assistance organization, claims<br />

39 percent of the homeless<br />

population are children under<br />

18 years, and 42 percent of<br />

those children are under age<br />

five.<br />

While their peers are busy<br />

thinking about what they’ll<br />

have for dinner, homeless<br />

children wonder it they’ll have<br />

dinner at all. While other<br />

students are pondering whether<br />

or not they should choose the<br />

cerulean crayon or the robin’s<br />

egg blue one, homeless kids sit<br />

with the broken, plain blue, a<br />

hand me down from their<br />

teacher. Being homeless will<br />

affect a person’s entire<br />

childhood and how they<br />

function when they are grown.<br />

NCFH reports that homeless<br />

children are exposed to more<br />

violence than normal children;<br />

therefore, they will become<br />

more aggressive and antisocial,<br />

have higher levels of anxiety<br />

and depression, and have<br />

increased apprehension. In<br />

addition, homeless children are<br />

sick four times more often than<br />

regular children, are four times<br />

as likely to show delayed<br />

development, have three times<br />

the rate of emotional and<br />

behavioral problems, and have<br />

twice the rate of learning<br />

disabilities. An estimated 5,000<br />

homeless kids a year will die<br />

from causes such as assault,<br />

illness, and suicide.<br />

Although child homelessness is<br />

a national issue, some members<br />

of the public are not<br />

completely aware of the<br />

problem.<br />

When Kyla Drozt (12, J&C)<br />

heard that Manual has around<br />

25 homeless students, her jaw<br />

dropped.<br />

“I had no idea that that many<br />

kids were homeless,” Drozt<br />

said.<br />

When Drozt thinks of homeless<br />

students, she immediately<br />

thinks of kids on the street, or<br />

kids who move from shelter to<br />

shelter.<br />

“I don’t really think too much<br />

about those not in a shelter or<br />

not on the street,” Drozt said.<br />

“I know they are there and that<br />

it’s a problem, but the street is<br />

my [mental image] of those<br />

kids.”<br />

Neha Srinivasan (11, MST)<br />

said that she thought child<br />

homelessness was “not having a<br />

stable living residence.”<br />

“It could be moving between<br />

shelters too,” Srinivasan said.<br />

“They have nothing of their<br />

own, and have never been<br />

anywhere that is their own.”<br />

Srinivasan works as a volunteer<br />

with Volunteers of America of<br />

Kentucky (VOA), which is one<br />

of the oldest and most diverse<br />

human service organizations in<br />

the region, according to VOA<br />

of Kentucky’s website.<br />

Because of her volunteerism,<br />

Srinivasan is more aware than<br />

most others about child<br />

homelessness.<br />

“[Child homelessness] is a<br />

problem everywhere, and<br />

although Manual is considered<br />

a place where a lot privileged<br />

people go, it is evident here,”<br />

Srinivasan said.<br />

Most of those interviewed said<br />

that when they thought of<br />

student homelessness, they<br />

thought of adults living on the<br />

streets with no food and no<br />

shelter.<br />

Rachel Mathis, a mother, said<br />

that when she thought about<br />

student homelessness, she<br />

thought of no stable living<br />

situation. Her husband, Robert<br />

Mathis, said he had never really<br />

thought of the issue before.<br />

Robert did say that although he<br />

never thought about it, he does<br />

see the homeless during his job<br />

all the time.<br />

Michelle Leslie (Counselor)<br />

thinks the public’s perception of<br />

child homelessness is distorted.<br />

“Typically when you see the<br />

news media coverage you have<br />

a picture in your mind of<br />

adults,” Leslie said.<br />

Almost nowhere else is this<br />

distortion more evident than in<br />

Kentucky.<br />

America’s Youngest Outcasts, a<br />

organization prepared by<br />

NCFH, reported that in 2013<br />

the state of Kentucky had the<br />

eighth worst child homelessness<br />

composite score in the nation<br />

and was the worst in the nation<br />

for the total amount of<br />

homeless children.<br />

Also according to the NCFH,<br />

in 2013, Kentucky had 95.9<br />

percent of its homeless child<br />

population in alternate<br />

housing, and only 4.1 percent<br />

were truly unsheltered;<br />

therefore, the majority of<br />

Kentucky’s homeless child<br />

population was, and still is, out<br />

of the public eye.<br />

Because of Kentucky’s large<br />

child homeless population, the<br />

6<br />

Continued on next page

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

state’s education system has<br />

suffered.<br />

After comparing the average<br />

2013 ACT score of each state<br />

to each state’s child homeless<br />

composite score in 2013, a<br />

correlation between the extent<br />

of child homelessness and a<br />

state’s average ACT score is<br />

evident. The correlation is 10<br />

of the 15 states with the<br />

highest average ACT scores<br />

also were part of the 15 states<br />

with the lowest composite<br />

scores for child homelessness.<br />

In addition, 8 of the 15 states<br />

with the lowest average ACT<br />

scores were in the list of the 15<br />

states with the highest<br />

composite scores for child<br />

homelessness.<br />

But, in order to get those<br />

composite scores and reliably<br />

compare and measure rates of<br />

child homelessness,<br />

homelessness needed to be<br />

clearly defined.<br />

The JCPS organization<br />

Homeless Education Program<br />

(HEP) provides advocacy and<br />

awareness for homeless<br />

students within the school<br />

district and defines homeless<br />

students as students living in<br />

any temporary living<br />

arrangements because of the<br />

lack of a fixed, regular, and<br />

adequate nighttime residence.<br />

This definition was a result of<br />

the McKinney-Vento Homeless<br />

Education Assistance Act,<br />

which is a federal law that<br />

ensures immediate enrollment<br />

and educational stability for<br />

homeless youth, according to<br />

the office of the<br />

Superintendent of Public<br />

Instruction.<br />

Compared to other counties in<br />

Kentucky, Jefferson and Harlan<br />

County were the two school<br />

districts with the highest<br />

number of homeless students.<br />

In 2012-2013, the HEP said<br />

JCPS started with about<br />

12,000 homeless children and<br />

then the number decreased to<br />

8,318 later in the year. While<br />

the amount decreased, JCPS<br />

still had a large gap between its<br />

child homeless population and<br />

that of any other district.<br />

Now, in <strong>2015</strong>, Scott Adams of<br />

the HEP estimated that there<br />

are 7,000 homeless students in<br />

Jefferson County which is<br />

about 7 percent of the student<br />

population.<br />

CLOSE TO<br />

HOME<br />

According to Laura<br />

Spiegelhalter (Transition<br />

Teacher), at any given time in<br />

Manual there are anywhere<br />

between 20 and 25 homeless<br />

students, or 1.3 percent of the<br />

student population.<br />

As well as homelessness, an<br />

alarming indicator of<br />

economic struggle in JCPS and<br />

at Manual is the number of<br />

students on the National<br />

School Lunch Program<br />

(NSLP), a program that offers<br />

free or reduced lunches to<br />

children at any participating<br />

school.<br />

According to the United States<br />

Government Publishing, to<br />

qualify for free or reduced<br />

lunches, a child’s family must<br />

have an income that is at or<br />

below certain annually<br />

adjusted poverty lines.<br />

Amy Medley (Counselor) said<br />

that Manual currently has 407<br />

students — 21 percent of the<br />

student population — on free<br />

or reduced lunches.<br />

While 407 students is a drastic<br />

amount of Manual’s student<br />

population, other schools in<br />

JCPS are even worse off.<br />

Hazelwood Elementary School<br />

in the South End has 96<br />

percent of its student<br />

population on free or reduced<br />

lunches, and Frayser<br />

Elementary School near<br />

Churchill Downs has 98<br />

percent of its student<br />

population, or about 371 of its<br />

379 students, on free or<br />

reduced lunches.<br />

JCPS’ large child homeless rate<br />

and NSLP student population<br />

can be attributed to high rates<br />

of poverty, an extreme lack of<br />

affordable housing, continuing<br />

impacts of the 2007-08<br />

recession, and racial and ethnic<br />

disparities according to<br />

America’s Youngest Outcasts.<br />

Such high rates of both<br />

homeless children and children<br />

on the NSLP points to more<br />

than problems within the<br />

system. Homeless children are<br />

forced to focus and thrive in<br />

environments that set them up<br />

to fail from the beginning, yet<br />

some prevail.<br />

Drake is the perfect example of<br />

someone who has been able to<br />

juggle the effects of<br />

homelessness and the<br />

responsibilities of being a<br />

student, despite the<br />

environmental predispositions.<br />

Continued on next page<br />

7

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

8<br />

Being in a military family,<br />

Drake moved around quite a<br />

bit, but that does not mean that<br />

the moves got any easier.<br />

“It was hard to make bonds<br />

with people,” Drake said. “It<br />

was cool being the new kid, but<br />

then again it like you always<br />

have to start over.”<br />

But, start over they did;<br />

especially with the move to<br />

Louisville.<br />

Drake said that they moved to<br />

Louisville because they were<br />

running away from his abusive<br />

father, and since getting to<br />

Louisville, his family has moved<br />

five times.<br />

Drake’s mother worked<br />

construction, but eventually<br />

became unemployed and<br />

dependent upon food stamps;<br />

therefore, Drake then had to<br />

get a job and work to support<br />

his family. Even with his job, he<br />

was not able to pull his family<br />

out of poverty. The family<br />

would live in neighborhoods<br />

where drug dealing was<br />

common. It did not seem as if<br />

Drake would break the chains<br />

of his economic deficiencies,<br />

and this was exemplified in his<br />

social life and school.<br />

“I would go to other people’s<br />

houses and never invite anyone<br />

over to mine,” Drake said.<br />

Drake kept most of his<br />

problems to himself and was<br />

reserved and too distrustful of<br />

anyone to tell of his situation.<br />

This lack of openness led to<br />

problems with his schoolwork.<br />

During his freshman year at<br />

Manual, Drake had around a<br />

1.85 GPA for the semester, and<br />

out of eight teachers, only one<br />

pulled Drake aside and<br />

questioned how he was doing.<br />

That teacher was Connie<br />

Wilcox (Humanities).<br />

“It’s nothing you can even<br />

explain, it’s just a vibe and<br />

when you are around them one<br />

day, you notice something is<br />

off,” Wilcox explained.<br />

Drake had trouble completing<br />

many assignments because he<br />

had no internet access at home<br />

and his mother could not afford<br />

basic school supplies.<br />

“Freshman year, we had a<br />

binder check and I turned in a<br />

notebook instead. She<br />

questioned why I didn’t have a<br />

binder and I told her that I<br />

wasn’t able to buy a binder,”<br />

Drake said.<br />

For Wilcox, Drake’s struggle<br />

with class deadlines was also a<br />

tip off that something was<br />

wrong.<br />

“I do remember that he would<br />

spend more than the average<br />

amount of time completing<br />

assignments,” Wilcox said.<br />

In another instance, Drake<br />

wrote a paper but was not able<br />

to type it himself, so he had to<br />

give it to a friend to type it for<br />

him, which took a toll on him<br />

emotionally.<br />

“I was ashamed because I had<br />

done something myself, but still<br />

had to ask someone for help,”<br />

Drake said. “I had nothing to<br />

call my own.”<br />

Drake even had to write his<br />

entrance essay to Manual on a<br />

piece of paper in pencil.<br />

Similar to Drake, Jessica (10,<br />

MST), who has been given an<br />

alias for her protection, is<br />

constantly on the move.<br />

However, her struggles are due<br />

to an extremely toxic home<br />

environment that all started<br />

with an accident.<br />

During her sixth grade year,<br />

Jessica’s father had an accident<br />

that resulted in massive brain<br />

trauma and permanent brain<br />

damage, and that traumatized<br />

her for years to come.<br />

“I basically watched him die,”<br />

Jessica said.<br />

After the accident, Jessica<br />

quickly realized that she would<br />

have to become the adult in the<br />

household.<br />

Living with a disabled mother<br />

and father, Jessica had to<br />

babysit and work from a young<br />

age in order to pay for rent.<br />

She was always secretly trying<br />

to support her parents as well.<br />

“I use to sneak out of the house<br />

when I was 12 or 13, when my<br />

friends would give me money,<br />

and go to the grocery store and<br />

buy chocolate for my parents<br />

and other groceries,” Jessica<br />

said.<br />

Jessica would even take some of<br />

her own profits from<br />

babysitting and discreetly put<br />

the money in her parents’<br />

wallets.<br />

Even with combined income of<br />

Jessica’s work and the added<br />

federal money to compensate<br />

for her parents’ disabilities, it<br />

was not enough to save her first<br />

home.<br />

She had to sell most of her<br />

belongings to make money for<br />

their next destination, and<br />

while moving she lost her most<br />

prized possession, a gift from a<br />

close friend.<br />

“I felt as if my childhood had<br />

been ripped away,” Jessica said.<br />

And if that were not enough,<br />

her parents’ mental illnesses did<br />

away with whatever was left.<br />

Continued on next page

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

“My parents are my parents,<br />

but I’ve never felt safe with just<br />

my mom in the house or alone<br />

with my dad,” Jessica said.<br />

“He’s never been [physically]<br />

abusive, but it’s that paranoia of<br />

he might turn one day because<br />

of his brain injury.”<br />

Along with her fears of<br />

physicality, her father was also<br />

verbally degrading to Jessica.<br />

This, coupled with her mom’s<br />

occasional suicidal actions and<br />

lack of parental guidance,<br />

wrecked Jessica socially.<br />

Jessica said that last year she<br />

didn’t know how to act around<br />

her peers. She made fun of<br />

people and slapped them<br />

because it made her feel better.<br />

Following her social crash came<br />

an academic catastrophe.<br />

Jessica was an A and B student<br />

in middle school, but when she<br />

arrived at Manual and after her<br />

father’s accident and move,<br />

she received her first U.<br />

Soon, her grades spiraled<br />

out of control and she began<br />

receiving straight U’s.<br />

Freshman year she was bullied<br />

everyday because of her low<br />

marks.<br />

“School for me, at first, was not<br />

a number one priority because<br />

I had five bags to my name.<br />

That’s all I had,” Jessica said.<br />

But luckily for her, she had her<br />

best friends to stand by her<br />

through the hardships.<br />

“A lot of people that I get close<br />

to go away because of all my<br />

problems, so I don’t tell anyone<br />

my problems but for these two<br />

people,” Jessica said.<br />

Her two best friends were there<br />

to support Jessica. One even<br />

saved her life after intervening<br />

in Jessica’s suicide attempt<br />

because of her verbal abuse<br />

from her father.<br />

“We are insanely close,” Jessica<br />

said. “I wouldn’t be here<br />

without them.”<br />

After moving five times,<br />

between her grandmother’s<br />

house, apartments, different<br />

houses, and running away to<br />

friends’ houses, Jessica is now<br />

stable and at Safe Place, a<br />

YMCA service that offers teens<br />

and young adults in crisis a safe<br />

place to stay.<br />

“It’s better to be away and have<br />

somewhat of a vacation away<br />

from my parents,” Jessica said.<br />

She is now protected, has<br />

changed her lifestyle, and is<br />

getting good grades.<br />

“Because I lost everything, it<br />

really opened my eyes to<br />

appreciating everything<br />

“For her, I’m her continuity. I’m her<br />

stability, and I think in her world, I’m<br />

her friend.” Finley said<br />

more and taking life one<br />

step at a time,” Jessica said.<br />

Those were Jessica’s personal<br />

steps, but now for a general<br />

theory.<br />

Psychologist Abraham Maslow<br />

developed a theory called the<br />

Hierarchy of Needs. The<br />

Hierarchy of Needs organizes<br />

our motives in life into a<br />

pyramid, and one must<br />

complete the needs for each tier<br />

to move to the next level in the<br />

pyramid. According to the<br />

Myer’s Psychology for AP textbook,<br />

there are six tiers in this order<br />

from bottom to top: the need to<br />

satisfy hunger and thirst, the<br />

need to feel safe, the need to<br />

love and be loved, the need for<br />

self-esteem, achievement, and<br />

respect, the need to live up to<br />

our potential, and the need to<br />

find meaning beyond the self.<br />

The individual is supposed to<br />

move from the first tier all the<br />

way to the last tier.<br />

Although the order of needs is<br />

not universally fixed, which<br />

means we bounce from tier to<br />

tier, the theory still raises an<br />

interesting point: if these<br />

homeless students are not even<br />

reaching the needs of the<br />

bottom most basic tiers, then<br />

they will never be able to get to<br />

the top tiers and develop<br />

correctly.<br />

Helping<br />

Hands<br />

When the final bell<br />

rings at 2:20, Nicole<br />

Finley (English)<br />

drives down to<br />

Hotel Louisville and<br />

continues to live out<br />

her passion for<br />

teaching students.<br />

Hotel Louisville is located<br />

downtown and is as a hotel for<br />

visitors as well as transition<br />

housing for homeless families<br />

struggling to get back on their<br />

feet. Inside the hotel, Finley, or<br />

“Mrs. Nicole” as the kids in the<br />

shelter call her, has her own<br />

hotel room that serves as the<br />

tutoring room for students. One<br />

of whom is Brooke, or<br />

“Brookster” as Finley<br />

affectionately calls her.<br />

Brooke, a spunky, strongly<br />

opinionated, seven-year-old<br />

second-grader at Trunnell<br />

9<br />

Continued on next page

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

Elementary, started attending<br />

tutoring sessions at Hotel<br />

Louisville for assistance in<br />

reading, writing, and math.<br />

She has a country twang and<br />

a contagious energy. But,<br />

unlike most of the students<br />

tutored by Finley, Brooke does<br />

not live in the shelter.<br />

Brooke lives with her<br />

grandmother because she is<br />

unable to live with her<br />

separated parents. Her father<br />

was involved in drugs, and her<br />

mother was in and out of jail.<br />

While her mother now lives in<br />

a halfway house, she does not<br />

want Brooke to be exposed to<br />

that environment.<br />

Prior to attending tutoring<br />

sessions, Brooke was receiving<br />

“Needs Improvement” marks<br />

on her report cards.<br />

“She was doing horribly in<br />

school when I got her,” Finley<br />

admitted.<br />

Finley then joked about<br />

Brooke’s conduct. Trunnell<br />

measures behavior by color —<br />

green for good, red for bad.<br />

“She reached black on the<br />

school’s color chart…I didn’t<br />

even know black was a color<br />

on the chart! She was<br />

completely out of control.”<br />

Slowly the process started.<br />

The door to Finley’s tutoring<br />

service is open four days a<br />

week, and after a while,<br />

Brooke was attending all four<br />

days. This long-term close<br />

proximity allowed a beautiful<br />

friendship to blossom between<br />

the tutor and student.<br />

“For her, I’m her continuity.<br />

I’m her stability. And, I think<br />

in her world, I’m her friend,”<br />

Finley said.<br />

Another reason why their<br />

friendship works is the<br />

constant laughter shared<br />

between the two.<br />

“Even when you are getting<br />

on her butt she makes you<br />

laugh.” Finley said.<br />

During the five month period<br />

Brooke has been attending<br />

tutoring, she has experienced<br />

a radical transformation in her<br />

school performance and<br />

conduct.<br />

“One morning, I received a<br />

phone call from Brooke’s<br />

grandmother telling me<br />

Brooke didn’t want to go to<br />

school,” Finley said.<br />

It turned out that Brooke was<br />

sad because she didn’t see<br />

Finley the night before at<br />

tutoring and got worried.<br />

“[Brooke] started balling on<br />

the phone, and [Brooke]<br />

started screaming, ‘I was<br />

worried about you! You didn’t<br />

call me or talk to me!’” Finley<br />

said.<br />

Little did Finley know, Brooke<br />

had planned a little surprise<br />

for her beloved tutor.<br />

“She comes into the hotel and<br />

she sees me and runs down<br />

the hallway to me, and what<br />

does she have in her hand? A<br />

report card.” Finley said. She<br />

smiled and laughed to herself<br />

as she recollected this.<br />

“Brooke had gotten all O’s<br />

and a few S’s!” Finley<br />

exclaimed.<br />

Those grades are nearly the<br />

best Brooke can do for her<br />

grade level.<br />

“That’s the whole thing: she<br />

wanted me to see the report<br />

card,” Finley said. “I feel like<br />

we accomplished it together.”<br />

Then, Finley had a sudden<br />

realization.<br />

“I didn’t realize how<br />

important I was to her. I didn’t<br />

realize, but I knew how<br />

important she was to me,”<br />

Finley said.<br />

In one swift motion, the<br />

person who typically inspires<br />

had become inspired. And by<br />

a seven year old with a bit of<br />

sass.<br />

“She gives me hope. I admire<br />

her and her perseverance to<br />

not give up, because so many<br />

kids do,” Finley said. “That<br />

little girl is my baby. I would<br />

take her! She’s mine!”<br />

In addition to Finley, another<br />

individual has made a huge<br />

impact on Hotel Louisville:<br />

Maureen Boyd.<br />

After someone stole her<br />

possessions while she was<br />

attempting to travel home to<br />

Boston in 1990, Boyd found<br />

herself stranded and homeless<br />

in Louisville. Boyd went to<br />

Wayside Christian Mission for<br />

assistance and after two years<br />

there, the shelter offered her a<br />

job. She is now the Family<br />

Shelter Coordinator for Hotel<br />

Louisville.<br />

“I love helping people. I really<br />

do,” Boyd said. “That’s my<br />

passion: to see people succeed<br />

and make it in this world. I<br />

want them to see the best<br />

there is out there. I want them<br />

to know the sky is yours. You<br />

gotta reach for it…you gotta<br />

earn it,” Boyd said.<br />

And Boyd practices what she<br />

preaches.<br />

She is warm, but firm; critical,<br />

but constructive; continually<br />

offering advice and motivation<br />

for all of those around her to<br />

10<br />

Continued on next page

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

succeed; the epitome of an<br />

authoritative figure. Although<br />

her love for the kids in the<br />

shelter is unconditional, her<br />

roots in a no-nonsense family<br />

means she does not hesitate<br />

when it comes to discipline.<br />

No matter what trouble the<br />

kids give her, she’s always<br />

going to give love to them, be<br />

kind to them, and guide them.<br />

Even though her discipline is<br />

handed out swiftly and often,<br />

kids know it is out of love.<br />

Boyd has seen thousands of<br />

children throughout her 23<br />

years at Hotel Louisville, and<br />

said that when some of the<br />

kids arrive, they are very angry.<br />

“They are embarrassed to be<br />

here because they can be<br />

teased and bullied,” Boyd said,<br />

and in the case of Ty and La-<br />

Shawn, that is exactly what<br />

happened.<br />

One boy squirmed in his chair,<br />

restless, while the other stared<br />

blankly at the floor; head filled<br />

with thoughts of candy. Both<br />

of them could not care less<br />

about what they were doing.<br />

They cared about where they<br />

were and why they were there.<br />

During their interview, the<br />

juxtaposition between the<br />

brothers became clear. Ty, the<br />

younger of the two brothers,<br />

was extremely outgoing and,<br />

for lack of a better term, silly;<br />

La-Shawn was more reserved<br />

and shy, only occasionally<br />

making eye contact mumbling<br />

back half an answer to a<br />

question.<br />

Ty usually exerts all of his<br />

spunk and energy by playing<br />

with remote control cars (the<br />

ones that the other child<br />

residents hadn’t broken) and<br />

practicing football, which he’s<br />

most likely passionate about<br />

because of his love for<br />

University of Louisville sports.<br />

On the other hand, La-Shawn<br />

would much rather spend his<br />

time thinking about someday<br />

owning a Ford Mustang and<br />

playing with his transformers.<br />

But, besides being so different<br />

in personality, the brothers had<br />

plenty in common. Both loved<br />

to play games on tablets, both<br />

hated to share, both loved<br />

candy (too much), and, most<br />

importantly, both were<br />

homeless and lived in the<br />

shelter on the fourth floor of<br />

Hotel Louisville.<br />

As the interview continued,<br />

La-Shawn continued to<br />

complain about the lack of<br />

candy in his hands, and Ty<br />

persisted with a barrage of<br />

random noises and<br />

movements. All was normal, or<br />

as normal as it could get. Each<br />

question was routinely<br />

answered with boisterous<br />

responses from Ty, soft<br />

murmurs from La-Shawn, and<br />

the occasional interruption or<br />

playful remark. But, as soon as<br />

their father was mentioned,<br />

both boys fell silent, their heads<br />

and eyes glued to the floor.<br />

Seconds passed as if they were<br />

years and the pair shifted<br />

uncomfortably in their chairs.<br />

Then, only one brother spoke,<br />

and it only took him four<br />

words — a little over a second<br />

— to express the brothers’<br />

combined pain.<br />

“He messed us over,” Ty<br />

whispered.<br />

And that was it.<br />

Tywan, or Ty, and La-Shawn<br />

are two of three brothers in<br />

their family. They live in the<br />

shelter with their mother and<br />

baby brother, Junior.<br />

Ty, a third grader, and La-<br />

Shawn, a fifth grader, both<br />

attend King Elementary.<br />

Before they came into the<br />

stability of Hotel Louisville, Ty<br />

and La-Shawn were on the<br />

move, first at their cousins’<br />

house.<br />

“We were over at our cousins<br />

house, and they treated us<br />

wrong,” La-Shawn said.<br />

La-Shawn and Ty both said<br />

that while they were there,<br />

their cousins’ family punished<br />

them and treated them harshly.<br />

In addition to being treated<br />

poorly by family members, La-<br />

Shawn and Ty were bullied by<br />

kids at school, and even kids in<br />

the shelter because of their<br />

situation with their father,<br />

whom they left after he<br />

continually stole money that<br />

was for family necessities.<br />

“It just upset me because we<br />

are both here and we didn’t do<br />

anything wrong,” La-Shawn<br />

said.<br />

Kids at school and at the<br />

shelter would call them poor,<br />

make fun of their mother, and<br />

occasionally physically bully<br />

them.<br />

“This morning a kid kicked me<br />

as I was getting on the bus,” Ty<br />

said.<br />

The bullying is not just a<br />

recent occurrence either.<br />

Continued on next page<br />

11

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

“I’ve been bullied since<br />

kindergarten,” La-Shawn said.<br />

And although grateful for<br />

Hotel Louisville, La-Shawn<br />

quietly whispered “No” when<br />

asked if he liked living there.<br />

“We want our own place,” La-<br />

Shawn said determinedly.<br />

“Yeah! So that we can play<br />

football in the yard!” Ty<br />

added.<br />

Their only hope of getting<br />

their own home is if their<br />

mom gets a job within Hotel<br />

Louisville’s six month window.<br />

For the time being, she is able<br />

to use the benefits of the hotel<br />

to save up for a living space.<br />

But, until she gets a job and a<br />

home, the brothers will just<br />

have to stick to playing football<br />

on the tablet.<br />

Knowing that families come<br />

and go every six months, Boyd<br />

does what she can to provide<br />

for the children in the shelter,<br />

but what happens outside of<br />

the shelter it is out of her<br />

hands.<br />

With that said, schools are one<br />

of the largest places where<br />

enrolled homeless children<br />

spend their time, and schools<br />

are responsible for the<br />

development of the children<br />

within their walls.<br />

Under the McKinney-Vento<br />

Act, school districts are<br />

required to designate a<br />

homeless liaison to ensure that<br />

homeless children and youth<br />

are identified and served. The<br />

liaison must provide public<br />

notice to homeless families (in<br />

the community and at school),<br />

and facilitate access to school<br />

services including<br />

transportation. School districts<br />

are also required to track their<br />

homeless students and report<br />

that data annually to OSPI.<br />

According to Leslie, the job of<br />

the counselors is to find<br />

resources.<br />

“It depends on what the needs<br />

are. If it’s a need of clothing, if<br />

it’s a need of supplies, or if it’s<br />

a need for food, we have some<br />

resources that we can give to<br />

students,” Leslie said.<br />

Such resources include inschool<br />

fundraising and outside<br />

organizations, such as Meals<br />

on Wheels, Coat Closet,<br />

Blessings in a Backpack, and<br />

the Home of the Innocents.<br />

Regarding more personal<br />

matters, Leslie said that the<br />

school cannot actively pursue a<br />

case unless they have some<br />

indication that a student is in a<br />

situation that might call for<br />

intervention.<br />

“We have to get some type of<br />

lead that a student is<br />

struggling,” Leslie said, and<br />

one of the very few ways for a<br />

school to find out is from the<br />

homeless kids themselves, but<br />

these kids are not always able<br />

or willing to confide their<br />

situation to a school official.<br />

“They constantly have a chip<br />

on their shoulder: distrust. ‘I<br />

don’t know you, I don’t like<br />

you’,” Finley said. And this<br />

distrust can create a<br />

misleading sense of rebellion,<br />

which perhaps unfairly,<br />

teachers need to be able to see<br />

through.<br />

“Teachers see students more<br />

awake than their parents do!”<br />

Finley exclaimed.<br />

Therefore, teachers have to be<br />

as in tune to their kids as they<br />

can be, and teachers need to<br />

go outside of of their personal<br />

allotment of time and make<br />

time to invest in the personal<br />

lives of their students and<br />

make them feel as if they are<br />

cared for and belong to<br />

something.<br />

“Just give each child 5 minutes.<br />

You’d be surprised. It makes a<br />

difference. Sit down with each<br />

one of them by yourself. If you<br />

don’t say anything, then they<br />

think you don’t care,” Boyd<br />

said.<br />

Homeless kids want “to feel<br />

like you notice,” Finley said,<br />

and with a good teacher, these<br />

kids do not feel alone. Finley<br />

also said that this sense of<br />

togetherness will cause these<br />

kids to not feel the pain of<br />

ostracism, which could make<br />

homeless kids violent, act<br />

out,or do things like stealing.<br />

Although children in all<br />

schools, especially homeless<br />

children, need that care, it is<br />

difficult for teachers, especially<br />

at an academically rigorous<br />

school such as Manual.<br />

John Paul Schuster (Math) said<br />

that while these healthy<br />

teacher-student relationships<br />

are essential, people must keep<br />

in mind that with certain<br />

courses, for example math, the<br />

personal connection that may<br />

more easily occur in English is<br />

difficult to come by, and that<br />

the teachers’ rigid system of<br />

content deadlines makes it<br />

Continued on next page<br />

12

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

difficult for in-class personal<br />

connection.<br />

In class, there also needs to be a<br />

line between friend and<br />

teaching professional<br />

“You can’t be their friends but<br />

you certainly should be friendly<br />

and be part of the support<br />

system,” Wilcox said. “There<br />

always has to be an adult in the<br />

classroom and whether we like<br />

it or not, it has to be us<br />

teachers”<br />

Nonetheless, Finley said<br />

teachers may indirectly assume<br />

important parental roles for<br />

homeless children. “I think we<br />

forget who we are to the kids [as<br />

teachers.] We forget who we<br />

are,” Finley said.<br />

Therefore, Wilcox structures<br />

her class in a way that makes<br />

the students comfortable with<br />

their peers<br />

and the<br />

teacher.<br />

“One of my<br />

first goals in this<br />

class was to create community<br />

and create an atmosphere of<br />

trust because especially in here,<br />

I can’t expect people who have<br />

never danced in their lives to<br />

get up in the hall and dance if<br />

they think everyone including<br />

me is going to be laughing at<br />

them.”<br />

Wilcox made it a point this year<br />

to give students that she wished<br />

she had connected better with<br />

to call them by name, to display<br />

their work in the room, to call<br />

on them when she know they<br />

had the right answer, to try to<br />

give them immediate attention,<br />

“I can’t imagine why anyone would be<br />

in this profession if he or she didn’t<br />

care about kids.” Wilcox said<br />

and to foster a better<br />

relationship between her and<br />

the student.<br />

Wilcox also loves the support<br />

from teachers at Manual and<br />

said, “We’re a network, and if<br />

something goes on in one class,<br />

we usually hear about it and we<br />

work together to take care of<br />

our kids.”<br />

Finley’s class structure is similar<br />

to Wilcox’s in the respect that<br />

both put emphasis on healthy<br />

student-teacher relationships<br />

and what it means to their<br />

students.<br />

“The hope for these kids is that<br />

they rise above their<br />

circumstances and don’t let<br />

their circumstance define who<br />

they are,” Finley said.<br />

“These homeless kids, when<br />

they go to school lots of times,<br />

that is their home. It can be any<br />

school. Whatever school they’re<br />

assigned to, that’s their home.<br />

That’s where<br />

they’re going to<br />

unfortunately<br />

get a lot of<br />

times the most<br />

love,” Finley said.<br />

And that is exactly where Jessica<br />

gets her love.<br />

“I don’t necessarily have a life<br />

of my own,” Jessica said. Jessica<br />

said she feels as if her life is all<br />

about her parents, their<br />

illnesses, and the constant<br />

moving; but not while in school.<br />

“A home away from home is<br />

school or friends’ houses,”<br />

Jessica said.<br />

At school, Jessica can focus on<br />

herself and work to improve her<br />

life, and for six hours she is able<br />

to forget about all of her<br />

problems at home and escape<br />

the pain. “At school, I don’t<br />

have to worry about my<br />

parents. I’m doing work and<br />

being with my friends,” Jessica<br />

said.<br />

Along with an escape, means to<br />

see friends, and the opportunity<br />

to improve her livelihood,<br />

Manual has also given Jessica<br />

consistency. Every day it is a<br />

place where she can find<br />

confidence in herself and safety<br />

from the harshness of reality<br />

outside of the classroom.<br />

Although she lost all of what<br />

she cherished with the loss of<br />

her first home, Jessica found the<br />

welcoming halls of duPont<br />

Manual and the people inside<br />

who care for her. Happiness<br />

awaits her, it’s within reach, and<br />

she is loving every second of the<br />

ride.<br />

Manual has also given Drake a<br />

reason to be successful, but the<br />

reason came from outside of<br />

Manual’s academic rigor.<br />

“My outlet was probably<br />

football,” Drake said. The<br />

whole time while I was moving,<br />

I was going from place to<br />

place…but everyday I’m out on<br />

that same field and coming to<br />

the same school. That hasn’t<br />

changed at all,” Drake said.<br />

Having a football family and<br />

extra support helped increase<br />

Drake’s confidence, and he<br />

finally felt like something was<br />

stable in his life. Drake<br />

described this part of his life as<br />

his ‘come up’. And a large part<br />

of his new family was Dr.<br />

Oliver Lucas (Biology).<br />

“Coach Lucas, that’s my man,”<br />

Drake said. Dr. Lucas is the<br />

football coach for Manual,<br />

13<br />

Continued on next page

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

14<br />

whom Drake has known since he<br />

played middle school football at<br />

Noe.<br />

“I met him eighth grade year,<br />

and he used to always come to<br />

our practices and sometimes<br />

we’d talk,” Drake said.<br />

Drake also said Lucas would give<br />

him things, and although Drake<br />

never told him, he suspected<br />

Lucas knew of his situation.<br />

“There were times when he<br />

would give me TARC tickets,”<br />

Drake said. Drake also said that<br />

Lucas paid for his lunch during<br />

two-a-days, a period when a<br />

team practices twice a day, his<br />

freshman year.<br />

Then, when Drake could not<br />

afford to attend College<br />

Weekend, a recruitment trip that<br />

the football team takes every<br />

summer, Lucas offered to pay for<br />

his trip. Although Drake ended<br />

up unable to go he still feels like<br />

he owes Lucas.<br />

“He’s a father figure,” Drake<br />

said.<br />

The father Drake never had.<br />

Drake was on his bus home from<br />

school after six hours of a tiring<br />

middle school day. The eighthgrader<br />

was<br />

extremely<br />

anxious,<br />

because today<br />

would be the<br />

day when he<br />

would find<br />

out whether<br />

or not he<br />

would get<br />

into Manual.<br />

As he writhed<br />

in anxiety, the<br />

hard bus seat<br />

not adding<br />

any extra<br />

comfort,<br />

thoughts of acceptance and<br />

rejection swirled<br />

throughout his<br />

mind. The rumors<br />

the older kids told<br />

were not helping<br />

either. All week<br />

long, the Manual<br />

students had been<br />

saying that<br />

everyone gets<br />

accepted on one<br />

day and rejected<br />

the next. So,<br />

apparently, his<br />

acceptance<br />

depended on whether or not<br />

there would be anything in the<br />

mail for him today.<br />

After he arrived home, Drake<br />

did what had become almost<br />

routine lately: he checked the<br />

mailbox. He knew that a<br />

rejection letter would be thin,<br />

and an acceptance letter would<br />

be thick; however, when he<br />

opened the mailbox, there was<br />

nothing. The world stopped<br />

around him. ‘The rumors must<br />

be true. I’ve been rejected,’ he<br />

thought to himself. Drake, with<br />

the weight of his heart on his<br />

sleeve, walked inside and sat on<br />

the stairway leading upstairs. He<br />

would now have to attend his<br />

home school, Southern. The<br />

sudden realization that his<br />

dream of playing football<br />

at Manual sunk him<br />

further into his depressive<br />

state.<br />

Then, the pitter-patter of<br />

rain on the roof grabbed<br />

his attention, and Drake<br />

decided that the sad state<br />

of the weather might make<br />

him feel better. ‘I just want<br />

to feel something,’ he said<br />

to himself as he sat on his<br />

stairs outside. But, soon the<br />

rain became too harsh,<br />

and he trudged back inside<br />

the house, immediately going to<br />

the nearest window. He<br />

watched droplets of rain<br />

stream down the<br />

window, accompanied<br />

by his own. All of a<br />

sudden, the rain<br />

stopped, he heard a<br />

thump, and then<br />

footsteps walking away<br />

from his front door.<br />

Drake rushed to the<br />

door to see a large<br />

packet on the floor. With<br />

a careful excitement, he<br />

opened the packet to see<br />

a letter. At the top, was the name<br />

“duPont Manual.” He stared at<br />

the letter for at least 60 seconds;<br />

just rubbing the sides of the<br />

packet. He wanted to take it all<br />

in, in one moment. Drake<br />

snapped out of his shock and<br />

excitedly opened the packet.<br />

Unfortunately, he opened it the<br />

wrong way, and his beautiful<br />

confetti fell to the floor with a<br />

thump. He didn’t even care; he<br />

had gotten in. He called his<br />

mom to tell her the good news,<br />

never picking up the contents of<br />

the packet from the floor. He<br />

wanted<br />

to leave it just the way it had<br />

been for when his mom would<br />

get home. Drake, at last, had an<br />

event he could say went exactly<br />

like he wanted it to. He, at last,<br />

had done something with the<br />

little he had. He, at last, had<br />

found himself a home.

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

Photos, Diversity, Equity, and Poverty Programs<br />

Homeless Education Conference Creates Awareness & Change!<br />

By Natalie Harris, Executive Director, Coalition for the Homeless<br />

I feel so<br />

fortunate to<br />

have been<br />

asked to be<br />

part of the<br />

very<br />

successful<br />

Above, Natalie Harris speaks at the <strong>2015</strong> Homeless Education Conference. Homeless<br />

Education Regional Conference coordinated by<br />

Jefferson County Public School’s Homeless<br />

Education Office on November 2, <strong>2015</strong>. It was<br />

thrilling to see over 150 attendees that included<br />

teachers, administrators and providers who care<br />

about every student in their classroom, school and<br />

program including those who have no place to go<br />

when they<br />

leave school<br />

each day. But,<br />

it is also sad to<br />

think that<br />

homelessness<br />

among our<br />

community’s<br />

Above, JCPS staff attend the <strong>2015</strong> Homeless Education Conference.<br />

children has<br />

become such a large issue that it is affecting not only<br />

our students and families but their teachers and<br />

fellow students.<br />

In 2014, 1,362<br />

children under<br />

18 lived on the<br />

streets or in an<br />

emergency<br />

shelter for<br />

Photo, google images.<br />

some period of<br />

time. Another 499 young adults between 18 and 24<br />

were also homeless during that year. And, this does<br />

not include over 5,000 JCPS students who lost<br />

housing and were forced to live doubled up with<br />

family or friends. Research shows that all of these<br />

children struggle to balance the stress of their<br />

situation with the need to study and learn and you<br />

see that borne out in your classrooms daily.<br />

Jefferson County Public Schools are working to<br />

address this issue on the systemic level by making<br />

sure students get appropriate transportation, after<br />

school opportunities and tutors but there are still<br />

important ways that only teachers and<br />

administrators can have an impact.<br />

15

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

First, when children and young adults were asked in<br />

a local Coalition Supporting Young Adults study<br />

about the one most effective thing that made a<br />

difference in their education and future, they<br />

consistently said at least one adult who listened and<br />

cared about what they had to say. Asking, checking<br />

in and most important, listening, really do make a<br />

difference. Second, there are lots of opportunities in<br />

school to discuss homelessness so that children know<br />

it does not make you different and so that when new<br />

children become homeless they can talk about it<br />

with their teachers and fellow students. To aid in<br />

this, you can find lots of fact sheets (including this<br />

one from the National Coalition) - http://<br />

www.nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/Fact<br />

%20Sheet%20and%20LessonPlan-K-2.pdf and<br />

lesson plans - http://learningtogive.org/lessons/<br />

unit119/lesson3.html specifically for children.<br />

Libraries also now have many books on the topic<br />

which can be helpful. Discussion about the issue<br />

should not just talk about homelessness but give<br />

students ways that they can help address the issue.<br />

You can make cards for homeless kids, collect items<br />

needed at homeless shelters or do a service project<br />

from your school.<br />

And, finally,<br />

we cannot<br />

talk about or<br />

address youth<br />

homelessness<br />

without<br />

talking about<br />

their families.<br />

The JCPS<br />

Family<br />

Resource<br />

Centers are<br />

fabulous<br />

Photo, JCPS communications.<br />

resources for<br />

these families. You can also make referrals to the<br />

Photo, Louisville Metro<br />

local Neighborhood Place or contact 2-1-1 for local<br />

resources to prevent homelessness, find clothing,<br />

food or address other needs. And, newly homeless<br />

families can contact the Bed One-Stop at 637-BEDS<br />

seven days a week beginning at 10:00 a.m. to make a<br />

reservation in a local homeless shelter. If you need<br />

help with any of this, Jefferson County Public<br />

Schools has a fabulous Homeless Education Office<br />

that can help you make these referrals or get<br />

resources to insure a family is stabilized and the<br />

child can stay in school. In a better world, children<br />

would not be homeless and the issue would not<br />

affect our schools, teachers and students. But, until<br />

that can be addressed, I am happy to be part of a<br />

community that cares and that is working to wrap<br />

appropriate services around our children and their<br />

families.<br />

16

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

Photo, Abdul Sharif<br />

Left, Chrystal Hawkins embraces a student at King Elementary.<br />

Say Hello to Chrystal Hawkins:<br />

Homeless Education Resource<br />

Teacher<br />

Who:<br />

Chrystal<br />

Hawkins,<br />

former King<br />

Elementary<br />

School<br />

teacher, past<br />

nonprofit<br />

education<br />

program<br />

Above, Chrystal Hawkins facilitates a Literacy & Confidence session<br />

coordinator,<br />

and recent Spalding University Teacher Leader<br />

graduate<br />

My vision:<br />

To remove all barriers to student achievement and<br />

empower students to advocate for their education and<br />

success<br />

Some of my immediate goals as a Homeless<br />

Education resource teacher:<br />

• To design and implement academic<br />

intervention programs (in school and after<br />

school) for homeless students<br />

• To provide instructional resources to schools<br />

serving homeless students<br />

• To collaborate and partner with schools,<br />

district leaders, and community organizations<br />

17<br />

to remove barriers to the academic<br />

achievement of homeless students<br />

Why this is more than a job:<br />

As a JCPS student, I experienced homelessness and<br />

can relate to the anxiety, fear, and stress that students<br />

encounter as families try to transition to a permanent<br />

living situation. The uncertainty of housing, the loss<br />

of possessions, and the shame are just a few of the<br />

things that homeless students may focus on rather<br />

than academics. While I can’t eliminate<br />

homelessness, I can ensure that there are academic<br />

opportunities and supports for homeless students to<br />

bridge the gap between worry, loss, and fear and the<br />

academic goals we want all students to reach.<br />

Current projects:<br />

“Literacy &”—In partnership with Diversity, Equity,<br />

and Poverty Programs, we’ve developed and<br />

implemented “Literacy &” Programs dedicated to<br />

serving homeless and socioeconomically<br />

disadvantaged students by linking standards-based<br />

literacy instruction and interventions to characterbuilding<br />

activities, such as karate, chess, photography,<br />

yoga, dance, and more.<br />

In closing:<br />

I look forward to working with other dedicated<br />

school, district, and community leaders who are<br />

passionate about making sure all students can and will<br />

achieve!

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

How I Overcame Homelessness<br />

Through Confidence Building and<br />

Community Service<br />

By Tonya Clinkscales, JCPS Employee<br />

In 1997, I found myself in<br />

the process of a divorce<br />

with two small children to<br />

support. During the<br />

process, I lost my<br />

apartment, my car, and a<br />

great deal of selfconfidence<br />

as I struggled,<br />

too embarrassed to ask for<br />

help and too proud to<br />

allow my family to see my<br />

failures. I moved around, living with different<br />

friends from time to time, until finally deciding to<br />

move back into my mother’s home in order to<br />

provide some type of stability for my children.<br />

Things were very difficult, and I had no idea how to<br />

remedy my situation. After seeing an advertisement,<br />

I decided to apply for a job with Jefferson County<br />

Public Schools as a school bus driver. It wasn’t easy<br />

starting over; I was at my all-time low. Depression<br />

was knocking at my door. I wasn’t sure I could do it,<br />

and many times, I just wanted to give up and give<br />

in, but I didn’t. I realized during all of my struggles<br />

that there was a higher power giving me the<br />

strength to continue on my journey. I remember my<br />

mother saying, “There is no limit to success as long<br />

as you have faith.” I am so thankful and so blessed<br />

in so many ways.<br />

As time progressed, I was able to find permanent<br />

housing for my little family, and I found myself<br />

feeling alive again. It wasn’t a cure-all, but it was a<br />

starting point. I was taking control of my life again.<br />

While I now had some stability and direction, I was<br />

still a single mother who faced the same difficulties<br />

as all other single mothers. I began my tenure at<br />

JCPS in 1997 as a school bus driver. In 1999, I was<br />

named Bus Driver of the Year in Jefferson County.<br />

In 2000 came a promotion to assistant coordinator.<br />

In 2004, I opened a new compound as the new<br />

coordinator, which eventually led to my current<br />

position as manager of operations in<br />

Transportation Services. In 2008, I was assigned the<br />

task of providing transportation to all homeless<br />

students in Jefferson County. No one knew that 11<br />

years prior, my own children were homeless<br />

students. Receiving this assignment allowed me to<br />

connect my career path with my personal path,<br />

providing me the opportunity to help students at a<br />

critical point in their lives.<br />

I take so much pride in working with each family, as<br />

I search high and low for a bus for each of my<br />

students, to give them stability, comfort, and some<br />

consistency during their time of hardship. When<br />

working for my students, I am diligent in making<br />

certain that they receive the attention and support I<br />

would have hoped for my own children to receive<br />

when we were in the same situation. I spend time<br />

searching each route individually to provide the<br />

best, most effective services to my students. Their<br />

education is important regardless of their status or<br />

where they live.<br />

As one who has faced challenges and continues to<br />

strive for my personal best, I understand the<br />

importance of community guidance and<br />

partnership. Therefore, I am committed to serving<br />

my community through services, such as providing<br />

motivational conversations with single mothers and<br />

young ladies, organizing job fairs in the community,<br />

contributing business clothing for young ladies<br />

seeking employment, working with the Center for<br />

Women and Families to provide necessary items for<br />

families starting over, and providing transportation<br />

for community events as well as transportation for<br />

after-school activities for disadvantaged children.<br />

I believe that my life experiences were fated to allow<br />

me the personal challenge and growth necessary to<br />

be able to go forward and share with my<br />

community, helping others who face the same<br />

adversity and giving them the necessary tools to<br />

turn their obstacles into opportunities. After all,<br />

everyone deserves an opportunity.<br />

18

<strong>ENVISION</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>DECEMBER</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

Homeless Students Learn About Resiliency, Perseverance, and Competition<br />

Through the Literacy and Chess Program at St. Vincent de Paul<br />

Photo, Abdul Sharif<br />

By King Elementary School Staff<br />

When<br />

many<br />

students<br />

arrived on<br />

the first day<br />

of the<br />

Literacy<br />

and Chess<br />

Program at<br />

Above, a student ponders her next chess move.<br />

St. Vincent<br />

de Paul, teachers heard questions from students like,<br />

“What’s for breakfast?” or “What’s chess?” Fortunately,<br />

by the end of the first day, students were able to<br />

answer both questions with the same answer,<br />

“something that will nourish you and help you grow!”<br />

Understanding<br />

that breakfast<br />

is nourishment<br />

and needed for<br />

growth and<br />

development<br />

was not as<br />

much of a<br />

Above, students finish up an important project.<br />

shock as it was<br />

understanding that chess can do the same thing. When<br />

we threw literacy in the equation as part of a<br />

balanced, healthy diet for muscle building (brain<br />

muscles, that is), students were intrigued.<br />

The Literacy and Chess Program is a standards-based<br />

program designed to expose at-risk students to<br />

character-building activities while they receive<br />

connected literacy instruction from certified JCPS<br />

teachers, instructional assistants, and activity-related<br />

instructors (like chess coaches). Each day, the program<br />

begins with written reflection and discussion of goals,<br />

competition, perseverance, and other characterdevelopment<br />

themes. Students then learn and practice<br />

a standards-based skill while reading the program’s<br />

anchor text. Afterward, students receive instruction<br />

from a master coach connected with the program’s<br />