Recognizing Deadly Venomous Snakes from Harmless Snakes of Sri Lanka

Recognizing Deadly Venomous Snakes from Harmless Snakes of Sri Lanka

Recognizing Deadly Venomous Snakes from Harmless Snakes of Sri Lanka

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Declaration <strong>of</strong> Our Core<br />

Commitment to Sustainability<br />

Dilmah owes its success to the quality <strong>of</strong> Ceylon Tea. Our business was founded therefore on an enduring<br />

connection to the land and the communities in which we operate. We have pioneered a comprehensive<br />

commitment to minimising our impact on the planet, fostering respect for the environment and ensuring<br />

its protection by encouraging a harmonious coexistence <strong>of</strong> man and nature. We believe that conservation<br />

is ultimately about people and the future <strong>of</strong> the human race, that efforts in conservation have associated<br />

human well-being and poverty reduction outcomes. These core values allow us to meet and exceed our<br />

customers’ expectations <strong>of</strong> sustainability.<br />

Our Commitment<br />

We reinforce our commitment to the principle <strong>of</strong> making business a matter <strong>of</strong> human service and to<br />

the core values <strong>of</strong> Dilmah, which are embodied in the Six Pillars <strong>of</strong> Dilmah.<br />

We will strive to conduct our activities in accordance with the highest standards <strong>of</strong> corporate best<br />

practice and in compliance with all applicable local and international regulatory requirements and<br />

conventions.<br />

We recognise that conservation <strong>of</strong> the environment is an extension <strong>of</strong> our founding commitment to<br />

human service.<br />

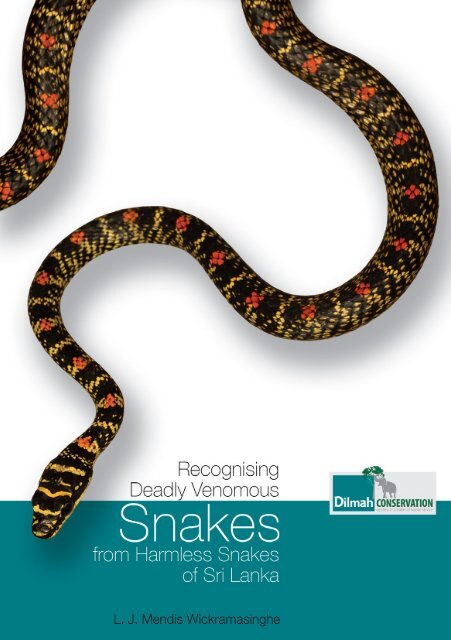

Front Cover:<br />

Chrysopelea ornata (Ornate flying snake (E); Pol mal karawala,<br />

Malsara, Panina karawala (S))<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most vibrantly coloured snakes in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> that<br />

has been aptly named Malsara (u,aird) which in Sinhalese<br />

means ‘cupid’. Unfortunately this harmless snake has become an<br />

innocent victim owing to its colouration (red, black, and yellow),<br />

which symbolise ‘danger’ in the animal world. Commonly found<br />

in the canopy <strong>of</strong> tall trees <strong>of</strong> the wet zone, this is a rare species<br />

in the drier parts <strong>of</strong> the island. Humans living on the periphery<br />

<strong>of</strong> forests are likely to encounter them more <strong>of</strong>ten, as they will<br />

come to feed on geckoes commonly found in human settlements,<br />

and unfortunately when they do, they are <strong>of</strong>ten killed due to<br />

misplaced fears.<br />

Back Cover:<br />

Left to Right Python molurus (Rock python), Echis carinatus<br />

(Saw scaled viper), Eryx conicus (Sand boa)<br />

We will assess and monitor the quality and environmental impact <strong>of</strong> its operations, services and<br />

products whilst striving to include its supply chain partners and customers, where relevant and to<br />

the extent possible.<br />

We are committed to transparency and open communication about our environmental and social<br />

practices.<br />

We promote the same transparency and open communication <strong>from</strong> our partners and customers.<br />

We strive to be an employer <strong>of</strong> choice by providing a safe, secure and non-discriminatory working<br />

environment for its employees whose rights are fully safeguarded and who can have equal<br />

opportunity to realise their full potential.<br />

We promote good relationships with all communities <strong>of</strong> which we are a part and we commit to<br />

enhance their quality <strong>of</strong> life and opportunities whilst respecting their culture, way <strong>of</strong> life and<br />

heritage.

© Ceylon Tea Services PLC<br />

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

This publication may be produced in whole or in part and in any form for<br />

educational or non-pr<strong>of</strong>it purposes without special permission <strong>from</strong> the<br />

copyright holder, provided acknowledgement <strong>of</strong> the source is cited. No use <strong>of</strong><br />

this publication may be made for resale or any commercial purpose whatsoever<br />

without prior permission in writing <strong>from</strong> the copyright holder.<br />

Disclaimer<br />

The contents and views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views<br />

or policies <strong>of</strong> the copyright holder or other companies affiliated to the copyright<br />

holder.<br />

Citation<br />

Wickramasinghe, L. J. Mendis (2014). Recognising <strong>Deadly</strong> <strong>Venomous</strong> <strong>Snakes</strong> <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>Harmless</strong> <strong>Snakes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. Colombo, <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>: Ceylon Tea Services PLC.<br />

Text & Photographs by<br />

L.J. Mendis Wickramasinghe<br />

Assisted by<br />

Nethu Wickramasinghe, Dulan Ranga Vidanapathirana<br />

and Gayan Chathuranga<br />

Design and Layout by<br />

Kasun Pradeepa. Wild Studio<br />

ISBN: 978-955-0081-12-7<br />

Ceylon Tea Services PLC<br />

MJF Group<br />

111, Negombo Road<br />

Peliyagoda<br />

<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong><br />

Contact<br />

info@dilmahconservation.org<br />

January 2014.<br />

Recognising<br />

<strong>Deadly</strong> <strong>Venomous</strong><br />

SNAKES<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>Harmless</strong> <strong>Snakes</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong><br />

Printed and bound<br />

Karunaratne & Sons (Pvt)Ltd.<br />

Authored by<br />

L. J. Mendis Wickramasinghe<br />

Advised by Channa Bambaradeniya, Ph.D.<br />

& Gernot Vogel, Ph.D.<br />

Edited by Devaka Weerakoon Ph.D.

Message <strong>from</strong> the Founder<br />

An unfortunate fear and loathing <strong>of</strong> snakes permeates through our society, and<br />

since childhood, I too have been no exception to this disappointing lapse. It is sadly<br />

commonplace for those who encounter snakes to attempt to kill them, owing to<br />

suspicions they harbour that all snakes are poisonous or deadly.<br />

I have learned that these misconceptions which cause panic and revulsion stems<br />

<strong>from</strong> a poor understanding <strong>of</strong> snakes and their habits, coupled with the inability and<br />

unwillingness to distinguish between different species <strong>of</strong> snakes. This results in the<br />

thoughtless killing <strong>of</strong> snakes, even though many types found in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> are largely<br />

harmless and do not attack unless threatened. I have also observed that this has proved<br />

to be a particular challenge within the plantation sector, and tea estates must be no<br />

exception for efforts in biodiversity conservation.<br />

Mr. L. J. Mendis Wickramasinghe has compiled a comprehensive illustrated field guide<br />

on behalf <strong>of</strong> Dilmah Conservation, which not only seeks to help readers easily identify<br />

snakes so that they will be able to deal with these creatures safely and considerately,<br />

but cultivate an interest and appreciation for the vital ecological role they play in<br />

pest control. It is my wish that this field guide will spark the curiosity <strong>of</strong> students in<br />

particular, and motivates them to pursue further learning and contribute towards the<br />

study and conservation <strong>of</strong> reptiles in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>.<br />

I firmly believe that it is the duty <strong>of</strong> Dilmah Conservation to strengthen its commitment<br />

to promoting socially and environmentally conscious educational initiatives towards<br />

fostering awareness, appreciation and respect for <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>’s natural wealth. Thus, I<br />

am confident that this publication ‘Recognising <strong>Deadly</strong> <strong>Venomous</strong> <strong>Snakes</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>Harmless</strong><br />

<strong>Snakes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>’ will mark a small but noteworthy contribution by Dilmah<br />

Conservation towards bridging the gaps in knowledge about snakes, minimising<br />

damaging misconceptions and thereby enabling their conservation by helping a broad<br />

audience improve their understanding.<br />

Merrill J. Fernando<br />

Founder – Dilmah Conservation

Recognising<br />

<strong>Deadly</strong> <strong>Venomous</strong><br />

SNAKES<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>Harmless</strong> <strong>Snakes</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong><br />

Authored by<br />

L. J. Mendis Wickramasinghe<br />

Advised by Channa Bambaradeniya, Ph.D.<br />

& Gernot Vogel, Ph.D.<br />

Edited by Devaka Weerakoon Ph.D.

Foreword<br />

Preface<br />

08<br />

<strong>Snakes</strong> are <strong>of</strong>ten considered deadly and dangerous and therefore persecuted<br />

by humans like no other group <strong>of</strong> animals. Yet snakes are an important part<br />

<strong>of</strong> natural and manmade ecosystems as they prey on many species that we<br />

consider as pests and help to keep their populations under control. One <strong>of</strong><br />

the biggest threats to snakes today is inadvertent killing by humans. Much <strong>of</strong><br />

these killings result due to our widespread fear and loathing towards snakes,<br />

as well as great deal <strong>of</strong> misinformation and misconceptions regarding them.<br />

In <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>, as this book clearly indicates, only 21 out <strong>of</strong> the 102 recorded<br />

species <strong>of</strong> snakes are deadly poisonous. Out <strong>of</strong> these only 5 species are<br />

known to cause fatalities in humans. Therefore, most <strong>of</strong> the snakes that we<br />

encounter in life are likely to be harmless. Further, snakes do not ordinarily<br />

attack humans unless provoked, startled or injured. Therefore, we can avoid<br />

the inadvertent killing <strong>of</strong> these useful creatures by becoming more aware<br />

about them. One important aspect <strong>of</strong> awareness is to develop an ability to<br />

identify poisonous snakes. This will not only help save snakes but will also<br />

be useful to save the life <strong>of</strong> a person bitten by a snake, as it is important to<br />

establish the identity <strong>of</strong> the snake before providing treatment to the snake<br />

bite victim. Identification <strong>of</strong> snakes is not a difficult task as most poisonous<br />

snakes show characteristic colour and scale patterns that will enable correct<br />

identification. However, many non poisonous snakes tend to mimic the<br />

colour patterns shown by poisonous species as a form <strong>of</strong> defense <strong>from</strong> their<br />

predators. As this is a trait that has evolved to confuse their predators it is not<br />

surprising that we too would be confused by this, which in this case is not<br />

working towards their favor. This book attempts to educate the reader about<br />

the value <strong>of</strong> snakes as well as how to differentiate poisonous snakes <strong>from</strong> non<br />

poisonous species. I am sure this book will help the reader to lessen their fear<br />

and hatred towards snakes while at the same time develop an appreciation<br />

and respect for their role in our ecosystems.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Devaka Weerakoon<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Zoology,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Colombo<br />

<strong>Snakes</strong> are a group <strong>of</strong> animals which have been especially revered in the <strong>Sri</strong><br />

<strong>Lanka</strong>n context. According to ‘Deepawamsa’, an ancient chronicle <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>,<br />

the ‘Naga (Snake)’ people, one <strong>of</strong> the four powerful tribes in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> who<br />

ruled the Northern and Western parts <strong>of</strong> the Island during the 6th century BC to<br />

3rd century BC, were snake worshippers. King Buddhadasa, the only monarch<br />

known to not only possess the skills <strong>of</strong> a physician and a surgeon, but also those<br />

<strong>of</strong> a veterinarian, was fabled to have treated a sick cobra as far back as 340-<br />

368 AD, revealing how compassionate ancient people were towards snakes. The<br />

ruins <strong>of</strong> the ancient cities also speak <strong>of</strong> the harmony between snakes and the<br />

people <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. These include guard-stones with a cobra-king providing<br />

protection to the premises, and seven hooded cobra statues built to protect the<br />

tanks constructed by the ancient Kings. However, changing times and four<br />

centuries <strong>of</strong> colonization have resulted in these ancient traditions being replaced<br />

by a lack <strong>of</strong> tolerance towards snakes. Like in the rest <strong>of</strong> the world, snakes have<br />

now become a feared group <strong>of</strong> animals in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>.<br />

The feeling <strong>of</strong> fear evoked by snakes coupled with an inherent reaction <strong>of</strong><br />

disgust <strong>of</strong>ten results in attempts to kill snakes. This fear could be justified when<br />

considering the number <strong>of</strong> deaths caused annually by poisonous snakes. Further,<br />

superstitions and misconceptions also play a significant role in vilifying these<br />

creatures.<br />

In reality, only few species <strong>of</strong> snakes can actually<br />

cause harm to people. Further, many snakes play<br />

a beneficial role in both natural and manmade<br />

ecosystems, as the natural enemies <strong>of</strong> many<br />

species who can otherwise undergo a massive<br />

population growth and become pests to man.<br />

Therefore, humans must find a way to co-exist<br />

with snakes on this limited land we have. As such,<br />

we must become aware <strong>of</strong> how to co-exist. This<br />

book intends to provide the reader with a broad<br />

overview about snakes in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>, with special<br />

emphasis on deadly poisonous snakes, and their<br />

identification.<br />

Ruins <strong>of</strong> a seven hooded cobra, protecting the water near<br />

Urusita Wewa, Embilipitiya

Contents<br />

10<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

This book was made possible thanks to Dilmah Conservation, who invited<br />

me to write a simple guide for the general public to identify venomous snakes<br />

in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. The fieldwork was made possible thanks to the Biodiversity<br />

Secretariat <strong>of</strong> the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Environment who provided funds and the<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Wildlife Conservation who provided the permit to conduct<br />

the research work. My heartfelt appreciation goes to Mr. Dulan Ranga<br />

Vidanapathirana and Mr. Gayan Chathuranga for assisting me while<br />

photographing and handling the snakes in the field. I would also like to thank<br />

Dr. Channa Bambaradeniya for his valuable comments and my colleagues at<br />

the Herpetological Foundation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> (HFS), for various courtesies. I<br />

wish to thank Dr. Gernot Vogel whose invaluable comments undoubtedly<br />

improved the quality <strong>of</strong> this book. I would also wish to extend my gratitude<br />

to Pr<strong>of</strong>. Devaka Weerakoon for the valuable time and effort he took to edit<br />

the text to its final form in which it is presented here. Last but not least to my<br />

dear wife Nethu, for her commitment to making this a success!<br />

Foreword .................................................................................................... 8<br />

Preface ........................................................................................................ 9<br />

Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 10<br />

1. <strong>Snakes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> ..................................................................................... 12<br />

1.1 Snake bites in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> ....................................................................... 16<br />

2. What is a Snake? ........................................................................................ 17<br />

3. Identification <strong>of</strong> <strong>Venomous</strong> snakes ............................................................... 20<br />

3.1 Mimicry ........................................................................................... 20<br />

4. Kraits .......................................................................................................... 24<br />

4.1 Bungarus caeruleus (Thel karawala/ Indian krait) ................................. 26<br />

4.2 Non venomous species that mimic the Indian Krait ............................... 28<br />

4.2.1 Lycodon aulicus (Alu radanakaya/ Wolf snake, House snake) .............. 28<br />

4.2.2 Lycodon osmanhilli (Mal radanakaya/ Flowery wolf snake) ................. 30<br />

4.2.3 Lycodon striatus (Kabara radanakaya/ Shaw’s wolf snake) ................... 31<br />

4.3 Bungarus ceylonicus (Mudu karawala/ <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>n krait) ...................... 33<br />

4.4 Non venomous species that mimic the <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>n Krait ...................... 35<br />

4.4.1 Cercaspis carinata (Dhara radanakaya/ <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> wolf snake) ............. 35<br />

4.4.2 Dryocalamus nympha (Geta radanakaya, Geta karawala/ Bridal snake) 37<br />

4.4.3 Dryocalamus gracilis (Meegata radanakaya/ Scarce bridal snake) ......... 38<br />

5. Vipers ........................................................................................................ 39<br />

5.1 Daboia russelii (Thith polanga/ Russell’s viper) ..................................... 40<br />

5.2 Non venomous species that mimic the Russell’s viper ............................ 42<br />

5.2.1 Eryx conicus (Wali pimbura, Kota pimbura / Sand boa) ..................... 42<br />

5.2.2 Python molurus (Dara pimbura, Ran pimbura/ Rock python) ........... 44<br />

5.3. Echis carinatus (Wali polanga/ Saw scaled viper) .................................. 46<br />

5.4. Non venomous species that mimic the Saw scaled viper ......................... 48<br />

5.4.1 Boiga triginata (Garandi mapila, Ran mapila, .................................. 48<br />

Kaeta mapila/ Gamma cat snake)<br />

6. Cobra ......................................................................................................... 50<br />

6.1 Naja naja (Naya or Nagaya/ Indian cobra, Spectacled cobra) ................ 50<br />

Literature cited ................................................................................................. 53

1. <strong>Snakes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong><br />

<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>n snake fauna comprise <strong>of</strong> 102 species belonging to 10 families 1-4 .<br />

Out <strong>of</strong> these 102 species, 87 live on land, 14 live in the ocean, and the<br />

remaining one inhabits brackish water. Nearly 49% (50 species) <strong>of</strong> the<br />

snake species found in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> are endemic to the island, or do not occur<br />

naturally anywhere else in the world 5 .<br />

Trimeresurus trigonocephalus (Green pit viper (E); Pala polanga (S)).<br />

Left: An Enhydrina schistosa (Hook nose sea snake (E); Valakkadiya (S)) killed by fishermen.<br />

Right: A close up image showing the typical flat tail <strong>of</strong> sea snakes.<br />

12<br />

The snakes <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> can be categorized into four groups, depending on<br />

the lethality <strong>of</strong> their venom. Accordingly, 21 species can be considered as<br />

deadly venomous; five species as moderately venomous and 12 species as<br />

mildly venomous. The remaining 64 species are non-venomous 1-4, 6-10 . This<br />

demonstrates that the majority <strong>of</strong> snake species (63%) are in fact, harmless.<br />

Members <strong>of</strong> the genus Boiga (Cat snakes (E); Mapila (S)), one <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

feared snakes, belong to the mildly venomous group, and its bite causes much<br />

less pain than one inflicted by a hypodermic needle. Moderately venomous<br />

snakes include four species <strong>of</strong> the genus Hypnale (Hump-nosed vipers (E);<br />

Kunakatuwa (S)), and Trimeresurus trigonocephalus (Green pit viper (E); Pala<br />

polanga (S)). Their bites will result in harmful effects such as gangrene,<br />

necrosis, tissue damage, kidney failure, blisters etc. Hypnale hypnale, which<br />

was previously known to be a moderately venomous snake 11 has now been<br />

classified as a deadly venomous snake 12-16 .<br />

Left: Hypnale hypnale (Hump nosed viper (E); Kunakatuwa/ Mukalang thelissa (S).<br />

Right: Close-up <strong>of</strong> the head showing the typical posture <strong>of</strong> hump nosed vipers,<br />

keeps their head slightly angled approximately at 45º.

Likewise, Echis carinatus (Saw-scaled viper (E); Vali polonga (S)) is restricted to<br />

the dry and arid zones <strong>of</strong> the island. Moreover, as the snake is very small in size<br />

(30 cm SVL), the amount <strong>of</strong> venom excreted in a single bite is very small 17 .<br />

Left: Hypnale zara (Zara’s hump nosed viper (E); Pahatharata thelissa (S)).<br />

Right: Close-up <strong>of</strong> the head showing its pointed snout/ rostral appendage, which is<br />

the most relible identification character for all hump nosed vipers in common.<br />

Calliophis melanurus (<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> coral snake (E); Depath kaluwa (S)).<br />

A very small snake similar in size to an ink tube <strong>of</strong> a carbon pen.<br />

14<br />

Left: Hypnale nepa (Merrem’s hump-nosed viper (E); Mukalan thelissa/<br />

Mukalang kunakatuwa(S)) Right: Close-up <strong>of</strong> the head.<br />

Out <strong>of</strong> the 21 species <strong>of</strong> snakes considered to be deadly poisonous, fourteen<br />

are sea snakes. These sea snakes are non-aggressive in nature, and since they<br />

are found only in deep waters they hardly interact with humans. Out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

remaining seven deadly poisonous species, two are coral snakes (Calliophis<br />

melanurus and Calliophis haematoetron) incapable <strong>of</strong> inflicting damage to<br />

humans owing to their small size (SVL, 30 cm). Out <strong>of</strong> the five species<br />

remaining, Bungarus ceylonicus (Ceylon krait (E); Mudu karawala (S)), is<br />

non-aggressive in nature and is to some extent an uncommon species.<br />

Therefore in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>, the majority <strong>of</strong> human deaths occur as a result <strong>of</strong> lethal<br />

snake bites caused by the 3 remaining species <strong>of</strong> deadly poisonous snakes:<br />

Bungarus caeruleus, (Indian krait (E); Thel karawala (S)), Naja naja, (Indian<br />

cobra (E); Nagaya (S)), and Daboia russelii (Russell’s viper (E); Thith polanga<br />

(S)) 14, 16, 18-19 .<br />

Due to the lack <strong>of</strong> understanding <strong>of</strong> snakes in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>, they are frequently<br />

killed regardless <strong>of</strong> their identity. Therefore, the ability to identify at least these<br />

three species will save the lives <strong>of</strong> human beings and a vast number <strong>of</strong> innocent<br />

and beneficial snakes. Therefore, the primary aim <strong>of</strong> this book is to help the<br />

reader to correctly identify life-threatening species, and thereby prevent the<br />

futile killing <strong>of</strong> a large proportion <strong>of</strong> harmless snakes.

1.1 Snake Bites in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong><br />

16<br />

In <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>, close to 37,000 snakebite cases are reported annually to<br />

hospitals 16 , <strong>of</strong> which about 100 cases will result in the death <strong>of</strong> the victim.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> these deaths occur in rural areas where the patients are brought to<br />

the hospitals at a very late stage due to the lack <strong>of</strong> transportation facilities.<br />

If the patients are given medical attention without delay these deaths can be<br />

avoided.<br />

We are attacked by snakes mostly due to our lack <strong>of</strong> understanding <strong>of</strong> what<br />

their preferred habitats might be. Apart <strong>from</strong> their naturally occurring<br />

habitats like termite mounds and bandicoot tunnels, venomous snakes like<br />

Cobras, Russell’s vipers and Kraits are attracted to places such as piles <strong>of</strong> rock<br />

used for construction work where there are plenty <strong>of</strong> empty spaces for them<br />

to hide, garbage mounds, stacked bricks, piled up coconut leaves, coconut<br />

roots, wood piles etc. In other words, while destroying their natural habitats<br />

we too are unintentionally recreating ideal habitats for them. Additionally,<br />

we also create ideal conditions for their prey, such as rats. Therefore, it is not<br />

a real surprise when snakes, like all other living beings, are attracted to places<br />

where there is plenty <strong>of</strong> food and shelter.<br />

The human-snake conflict is an issue that will continue to escalate due to<br />

the ever increasing human population and the consequent loss <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

habitat. However, the threat <strong>from</strong> snakes to humans remains comparatively<br />

low (approximately 100 deaths per year compared to other hazards such as<br />

accidents involving vehicles which claimed 2,721 lives and injured another<br />

26,847 persons in 2010 alone). Despite this, we are not afraid to travel<br />

on the roads, in a vehicle as we are aware <strong>of</strong> the different risks associated<br />

with modes <strong>of</strong> transportation. However, our fear <strong>of</strong> the unknown (such as<br />

our inability to differentiate a commonly encountered harmless snake <strong>from</strong><br />

a deadly venomous snake or our lack <strong>of</strong> understanding about their ways)<br />

drives us to kill them on sight.<br />

2. What is a Snake ?<br />

Many people fear snakes because they believe that:<br />

• All snakes are venomous and are seeking to kill humans.<br />

• <strong>Snakes</strong> have an unpleasant skin which is either sticky and slimy or scaly;<br />

• <strong>Snakes</strong> are dirty and unclean.<br />

However, it should be noted that many people reach the aforementioned<br />

conclusions without even having touched a snake or closely examining them. In<br />

reality, when a person is given the opportunity to closely inspect a snake, they<br />

become pleasantly surprised when they learn that these assumptions are baseless.<br />

• Majority <strong>of</strong> snakes are non-venomous and attack only if they feel threatened,<br />

in order to catch their prey, and not because they enjoy it. It needs to be<br />

understood that snakes play an important role in maintaining the ecological<br />

balance by controlling the population size <strong>of</strong> many species.<br />

• <strong>Snakes</strong> in fact possess a clean, dry skin.<br />

• Some snakes are in fact very colourful and beautiful.<br />

However, these animals have gained an unpopular reputation due to various<br />

reasons, and as a result they are killed by people who are unaware <strong>of</strong> their ecological<br />

importance. They are an integral part <strong>of</strong> a balanced ecosystem and play a significant<br />

ecological role as predators, thereby controlling populations <strong>of</strong> many species<br />

including pests such as rodents. <strong>Snakes</strong> are also good indicators <strong>of</strong> environmental<br />

pollution. An additional benefit <strong>of</strong> these creatures is that their venom,

which contains proteins, can be extracted<br />

for medicinal purposes, hence possessing<br />

an economic value.<br />

<strong>Snakes</strong> come in a diverse range <strong>of</strong> sizes,<br />

and are entirely carnivorous typically<br />

swallowing their prey whole. Depending<br />

on their size, their prey also varies <strong>from</strong><br />

small insects consumed by small earth<br />

snakes like Typhlops to heavy animals<br />

consumed whole by large pythons.<br />

Left: The scale arrangement <strong>of</strong> Cylindrophis maculate<br />

(<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> pipe snake (E); Depath naya (S)), a<br />

harmless burrowing snake. The image shows its tail<br />

rolled up, mimicking a hood <strong>of</strong> a cobra a typical<br />

defense mechanism against predators.<br />

Above: A Green pit viper, with wide open mouth<br />

showing its fangs.<br />

18<br />

All snakes have razor sharp teeth, which are used to prevent their prey <strong>from</strong><br />

escaping., They do not use their teeth to break their prey into smaller parts or<br />

for chewing since they swallow their prey whole. Fangs are specialized teeth<br />

that are only found in venomous snakes. These fangs are tube-like and makes<br />

it possible for the venom to be introduced efficiently into a wound once the<br />

snake strikes, thus immobilizing the prey in the shortest possible time.<br />

The venom and its delivery system are special tools they have developed<br />

through years <strong>of</strong> evolution, and it must be emphasized that their main<br />

purposes are to aid the capture <strong>of</strong> prey and self-defense (because snakes are<br />

both predators and prey), and are not intended specifically to hurt humans as<br />

many seem to believe. <strong>Snakes</strong> that lack venom resort to constriction in order<br />

to immobilize their prey.<br />

Left: Coeloganthus helena (Trinket snake (E);<br />

Katakaluwa (S)), a slightly venomous snake, with<br />

its mouth wide open showing its teeth. The orange<br />

arrow shows its fangs positioned towards the rear<br />

<strong>of</strong> its mouth, such fangs are known as back fangs.<br />

As mentioned before, not all snakes<br />

are venomous. The composition <strong>of</strong> the<br />

venom and its quantities vary <strong>from</strong><br />

species to species. In general it is a<br />

complex mixture <strong>of</strong> proteins which can<br />

be categorized according to the organs<br />

they attack i.e. neurotoxic (attacks<br />

the nervous system) or haemototoxic<br />

(attacks the circulatory system).<br />

Depending on their ability to kill their<br />

prey and the composition <strong>of</strong> venom they<br />

possess, snakes have been grouped in to<br />

four categories i.e. deadly venomous,<br />

moderately venomous, mildly venomous<br />

and non-venomous.

Can you identify them?<br />

Saw scaled viper and Gamma cat snake<br />

3. Identification <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Venomous</strong> <strong>Snakes</strong><br />

Which one is deadly?<br />

Russell’s viper and Pythons<br />

20<br />

In the animal world, different species use various techniques to survive. These<br />

include their need to find food and defense mechanisms geared to combat<br />

predation. <strong>Snakes</strong> have the ability to do this quite successfully, even to the<br />

extent <strong>of</strong> deceiving us human beings.<br />

3.1 Mimicry<br />

The most common mechanism used by snakes is called mimicry. Where<br />

non-venomous species mimic or superficially look like (casually resemble) a<br />

venomous snake, it serves as a warning to others, especially their predators,<br />

that they are venomous and must be avoided.<br />

Only one <strong>from</strong> these three are deadly venomous, which one is it?

Kraits and<br />

Wolf snakes<br />

15<br />

Although these species look<br />

quite similar, not all <strong>of</strong> them<br />

are venomous because the<br />

non-venomous ones mimic the<br />

venomous ones i.e. harmless<br />

species mimic<br />

the colour<br />

patterns <strong>of</strong><br />

deadly<br />

venomous<br />

snakes.

4. Kraits<br />

In <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>, there are two species <strong>of</strong> Kraits, the Indian krait and the Ceylon<br />

krait. They are both deadly venomous. Interestingly, there are six harmless<br />

species that mimic these kraits, including wolf snakes and bridal snakes.<br />

The best and the easiest character that can be used to differentiate the venomous<br />

Kraits <strong>from</strong> the non-venomous mimics is the dorsal scale row shown in the<br />

figure below.<br />

<strong>Venomous</strong> Kraits<br />

Large hexagonal scales running<br />

down the spine<br />

Non - venomous mimics<br />

All scales on back identical in size<br />

24<br />

Both snakes shown above display a common form <strong>of</strong> behavior seen among snakes, whereby<br />

they conceal their heads under their bodies as a defense mechanism. Above: Indian krait that is<br />

deadly venomous. Below: <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> wolf snake which is a non venomous species.

Prominent white cross bars in a juvenile.<br />

Simple identification character: Large hexagonal shaped scales running down<br />

its spine. Scales on its back are smooth, with the mid row much larger than all<br />

the other surrounding scales. This feature is the most important characteristic<br />

when identifying the species.<br />

Adult specimen, where the cross bars or white lines have reduced and scattered.<br />

4.1 Bungarus caeruleus<br />

Indian krait (E);Thel karawala (S)<br />

26<br />

Toxicity: <strong>Deadly</strong> venomous<br />

Size: 25 cm- 140 cm<br />

Colouration: Back bluish black to a pale faded bluish grey, with white<br />

cross bars occurring in pairs which become less distinct at the anterior end.<br />

These cross bars are prominent in juveniles or young animals and the lines<br />

gradually disappear or become reduced to scattered cross bars in adults. The<br />

ventral side, or the underside is <strong>of</strong>f-white.<br />

Left: Clear pairs <strong>of</strong> cross bars <strong>of</strong> a juvenile. Right: The cross bars gradually diminishing in adults.<br />

But both show enlarged hexagonal scale rows along the spine.<br />

Distribution: Non-endemic. Distributed in the dry, arid, and intermediate<br />

zones.<br />

Behavior: : It is a nocturnal species that is aggressive at night. Commonly found<br />

in and around human settlements. May attack if threatened but generally nonaggressive<br />

during day time. Will roll into a ball with its head well-concealed<br />

when agitated, and might spring out <strong>from</strong> this position upon further agitation.<br />

Feeds on: Other snakes, geckoes, lizards, rodents etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 10- 16 eggs per clutch.

4.2 Non venomous species that<br />

mimic the Indian Krait<br />

Three harmless Wolf snakes mimic the Indian Krait.<br />

Juvenile specimen.<br />

Scales on the back are all identical, and smooth. The subcaudal scales on the<br />

underside on its tail are all divided.<br />

28<br />

4.2.1 Lycodon aulicus<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Size: 18 cm- 80 cm<br />

Wolf snake, House snake (E); Alu radanakaya (S)<br />

Adult specimen.<br />

Colouration: Back dark brown to blackish brown, with white cross bars that<br />

divide laterally which are prominent in the anterior end. These cross bars<br />

are prominent in juveniles and young, and the lines gradually disappear or<br />

become reduced to scattered cross bars in adults. Lips are prominently white,<br />

while the ventral or underside is <strong>of</strong>f-white.<br />

Distribution: Non-endemic. Distributed in all parts <strong>of</strong> the island up to 2000 m<br />

asl. Commonly found in rural areas close to forests, in houses (especially among<br />

piles <strong>of</strong> wood, piles <strong>of</strong> stone, foundations and walls where there are plenty <strong>of</strong><br />

cracks/crevices), stacked bricks, piled up coconut leaves, and coconut roots etc.<br />

Behavior: : It is a nocturnal species that is aggressive at night and attacks fiercely.<br />

Will roll in to a ball with its head well concealed when agitated, and empty their<br />

bowels with a smell similar to that <strong>of</strong> rotten dead mice (hence the Sinhala name<br />

“Kunu mee karawala”) as a defense mechanism.<br />

Feeds on: Geckoes, lizards, small rodents etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay about 20 eggs.

Distribution: This species is endemic to <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. Distributed in all parts <strong>of</strong><br />

the island up to 2000 m asl. It is commonly found in urbanized and semiurbanized<br />

areas, in houses (especially under flower pots, piles <strong>of</strong> stone, loose<br />

soil, in foundations and walls where there are plenty <strong>of</strong> cracks/crevices), stacked<br />

bricks, piled up coconut leaves, coconut roots, piles <strong>of</strong> wood and in piled up<br />

goods such as clothes, books, boxes etc.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal species that is aggressive at night and attacks- and<br />

bites fiercely. Will roll in to a ball with its head well concealed when agitated,<br />

and empty their bowels with a smell similar to rotten dead mice. Hence, in<br />

Sinhala, it is called “Kunu mee karawala”, owing to the particularity <strong>of</strong> its<br />

defense mechanism.<br />

Feeds on: geckoes, lizards, small rodents etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 8-10 eggs per clutch.<br />

4.2.3 Lycodon striatus<br />

Shaw’s wolf snake (E); Kabara radanakaya (S)<br />

4.2.2 Lycodon osmanhilli<br />

Flowery wolf snake (E); Mal radanakaya (S)<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

30<br />

Size: 15 cm- 60 cm<br />

Colouration: They show two variations in colour. One morph has a light<br />

brown to a yellowish tinge, with divided yellow cross bars throughout its<br />

back. The other has a uniform light brown coloured body with no white<br />

markings on the back. In both cases the head colouration is light brown with<br />

a yellowish tinge. Eyes black and prominently seen because <strong>of</strong> the lighter skin<br />

colour compared to others, with white lips upon which every lip scale has a<br />

brown mark in the center.<br />

Scales on the back are all identical, and smooth. The subcaudal scales on<br />

the underside on its tail are all divided.

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Size: 9 cm- 28 cm<br />

Colouration: The back is dark brown to blackish brown in colour, with white<br />

cross bars which are prominent at the anterior end that divide laterally and<br />

are broken. In some, these cross bars are yellow. Its lips are white, however<br />

not as distinctly as L. aulicus.The ventral or the underside is <strong>of</strong>f-white.<br />

Scales on the back are all identical, and smooth. The subcaudal scales on<br />

the underside on its tail are all divided.<br />

Distribution: Non-endemic. Distributed in all parts <strong>of</strong> the island up to 2000<br />

m asl. Commonly found in houses (especially in piled up goods, in home<br />

gardens, mounds <strong>of</strong> stone, foundations and walls where there are plenty <strong>of</strong><br />

cracks/crevices), stacked bricks, piled up coconut leaves, coconut roots, and<br />

piles <strong>of</strong> timber etc.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal species that is non-aggressive and does not attack.<br />

Will roll in to a ball with its head well concealed when agitated.<br />

Feeds on: Small skink and lizards.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 5-6 eggs per clutch.<br />

An adult specimen showing the typical banding pattern and enlarged scale row on the spine.<br />

4.3 Bungarus ceylonicus<br />

<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>n krait (E); Mudu karawala (S)<br />

Toxicity: <strong>Deadly</strong> venomous<br />

Size: 100- 110 cm<br />

32<br />

Colouration: Back jet black, with white cross bars. These cross bars are prominent<br />

in juveniles/young and the lines gradually disappear or become reduced to<br />

scattered cross bars in adults. Ventral or the underside is black or alternately black<br />

Juvenile specimen with<br />

prominent white cross<br />

bars. The posterior half<br />

<strong>of</strong> the head is white<br />

coloured.

and white. Posterior half <strong>of</strong> the head in juveniles is white. However the white<br />

colour diminishes gradually with age.<br />

Simple identification: Large hexagonal shaped scales running down its spine.<br />

Scales smooth on back. They are much larger than all the other surrounding<br />

scales.<br />

4.4 Non venomous species that<br />

mimic the <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>n Krait<br />

There are three harmless snakes (<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>n wolf snake and two bridal snakes)<br />

that mimic the <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>n krait.<br />

Left: Faded white cross bars in an adult. Right: Prominent white cross bars in a juvenile.<br />

34<br />

Distribution: Wet, intermediate and rarely seen in the dry zone.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal species that is aggressive at night. Commonly<br />

found in and around human settlements. Potentially non-aggressive in<br />

nature, but may attack if provoked or threatened. Will roll in to a ball with its<br />

head well concealed when agitated, and will remain still until the perceived<br />

danger passes. They display this behavior much better than the Indian Krait.<br />

Feeds on: Other snakes, geckoes, lizards and rodents etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 6-10 eggs per clutch.<br />

4.4.1 Cercaspis carinata<br />

<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> wolf snake (E); Dhara radankaya (S)<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Size: 65 cm<br />

An adult specimen.<br />

Colouration: Head jet black and shiny, the body is black with white cross bars.<br />

These cross bars are prominent in juveniles/young and as they become adults the<br />

lines gradually disappear or become reduced to scattered cross bars. Ventral or<br />

the underside is black or alternately black and white. Posterior half <strong>of</strong> the head<br />

in juveniles is white and gradually diminishes with age.

A Juvenile specimen showing prominent cross bars and the<br />

posterior part <strong>of</strong> the head is white coloured.<br />

36<br />

Simple identification: Scales on the back are deeply ridged, keeled or rough,<br />

a character evident only in this species out <strong>of</strong> those that mimic kraits.<br />

Scales on its back are all identical, and deeply ridged. scales on the underside<br />

on its tail or subcaudal scales are all single or undivided.<br />

Distribution: Found only in the wet zone.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal species that is aggressive at night. Commonly<br />

found under leaf litter <strong>of</strong> the forest floor and in home gardens close to forests.<br />

May attack if provoked or threatened. Will roll in to a ball with its head well<br />

concealed when agitated, and will remain the same till the perceived danger<br />

passes.<br />

Feeds on: Geckoes, lizards, skinks, small rodents and rarely on other snakes<br />

etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 8-12 eggs per clutch.<br />

4.4.2 Dryocalamus nympha<br />

Bridal snake (E); Geta radankaya, Geta karawala (S)<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Size: 70 cm<br />

Colouration: The back <strong>of</strong> the animal is black with white cross bars which may<br />

be yellowish in juveniles. These cross bars are prominent in juveniles/young and<br />

the lines gradually disappear or become reduced to scattered cross bars in adults.<br />

Posterior cross bands are connected laterally. Ventral or the underside is white.<br />

Simple identification: Possesses a comparatively larger head with a slimmer<br />

neck area. Its body is adapted to climb trees, with a long tail and prominent<br />

ventral ridges on either side.<br />

Scales on the back are all identical and smooth. Underside scales on tail or the<br />

subcaudal scales are all divided.<br />

Distribution: Found in the dry and intermediate zones.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal non-aggressive species. Commonly found in large tree<br />

trunks and under debris, in and around home gardens or human settlements.<br />

Will roll in to a ball with its head well concealed when agitated.

Feeds on: Skinks and eggs <strong>of</strong> geckoes etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay eggs. But the number is not known, but a gravid<br />

female specimen with 5 eggs (upon external observation) has once been<br />

recorded.<br />

4.4.3 Dryocalamus gracilis<br />

Scarce bridal snake (E); Meegata radankaya (S)<br />

5. Vipers<br />

<strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> has two species <strong>of</strong> true vipers (Russell’s viper and Saw scaled viper).<br />

They are both deadly venomous, but very <strong>of</strong>ten people get these confused with<br />

non-venomous pythons.<br />

The best and the easiest characters to discriminate the venomous Russell’s viper<br />

<strong>from</strong> the two non-venomous pythons (Rock python/ Indian python and Sand<br />

Boa) are listed in the table below.<br />

Distinguishing characters Russell’s viper Rock Python Sand Boa<br />

Markings on back<br />

Regular, oval<br />

Irregular, cloud shaped<br />

Irregular, cloud shaped<br />

Distribution <strong>of</strong> scales on head<br />

Large number <strong>of</strong><br />

small sized scales<br />

Both large and<br />

small sized<br />

Small sized, large<br />

number<br />

Head scales<br />

Rough<br />

Smooth<br />

Rough<br />

A preserved museum specimen <strong>of</strong> Scarce bridal snake which was used to describe the species<br />

scientifically, deposited at the Natural History Museum London.<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Snout shape <strong>from</strong> top<br />

Labial pits<br />

Comparatively pointed<br />

Absent<br />

Blunt<br />

Present<br />

Blunt<br />

Absent<br />

38<br />

Size: 50 cm<br />

Remarks: A very rare species, only known <strong>from</strong> a single record.<br />

Colouration: Back, black with white cross bars. Similar to Dryocalamus<br />

nympha.<br />

Simple identification: Can only be separated by Dryocalamus nympha, by<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> costal scales. Where D. nympha, has 13 scales and D. gracilis<br />

has 15 scales.<br />

Distribution: Single record <strong>from</strong> Colombo, wet zone.<br />

Mid body scales on back<br />

Tail scales on back<br />

Sub-caudal/under side <strong>of</strong><br />

tail scales<br />

Vestigial hind limbs<br />

Distribution<br />

Rough/keeled<br />

Rough/keeled<br />

Divided<br />

Absent<br />

< 2000 m asl<br />

Smooth<br />

Smooth<br />

Single<br />

Present<br />

< 2000 m asl<br />

Smooth<br />

Rough/keeled<br />

Single<br />

Present<br />

Arid zone and coastal<br />

dry zone<br />

Behavior: Unknown Feeds on: Unknown Reproduction: Unknown

The row <strong>of</strong> spots on back <strong>of</strong> a Russell’s viper which are comparatively large and oval<br />

shaped outlined with a black line, with its outer border whitish.<br />

Simple identification: From the large oval spots that run down the body, and<br />

the keeled costal scales. The pair <strong>of</strong> scales over the eye or the supra ocular, and the<br />

supra nasal scales are large. This species can be identified <strong>from</strong> its loud hissing<br />

noise.<br />

5.1 Daboia russelii<br />

Russell’s viper (E); Thith polanga (S)<br />

Toxicity: <strong>Deadly</strong> venomous<br />

40<br />

Size: 120-130 cm<br />

Colouration: Earthy brown with three rows <strong>of</strong> dark brown spots on the back,<br />

one running down the spine and the other two on the sides <strong>of</strong> body. The row<br />

<strong>of</strong> spots on its back are comparatively large and oval shaped, outlined with<br />

a black line, with its outer border whitish, while those found on the lateral<br />

body are small and somewhat oval. On its head a pair <strong>of</strong> dark brown patches<br />

forms a light brown ‘V’ pointing toward the snout. Ventral or the underside<br />

is <strong>of</strong>f white with black or dark brown blotches.<br />

Head close up <strong>of</strong> Russell’s viper showing a pair <strong>of</strong> dark brown patches, which forms<br />

a light brown ‘V’ pointing toward the snout.<br />

Distribution: Found both in the wet and the dry zones < 2000 m asl.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal species that is aggressive at night. Commonly found<br />

in forests, in and around human settlements, paddy fields, under piled-up goods,<br />

and coconut husks etc. If provoked or threatened, it will coil and raise a third<br />

<strong>of</strong> its body and produce a loud hissing noise which is the loudest <strong>of</strong> all snakes.

Feeds on: Adults feed on rodents and birds, while juveniles may feed on<br />

geckoes, lizards, frogs etc.<br />

Reproduction: They give birth to 30-35 live young.<br />

5.2 Non venomous species that<br />

mimic the Russell’s viper<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Size: Female-100 cm, males-60 cm<br />

Colouration: Earthy brown with large dark brown blotches on back which are<br />

connected but may be separated. Much smaller blotches are found on the side<br />

<strong>of</strong> its body, which are randomly distributed. Ventral or the underside is pinkish<br />

in colour.<br />

The two non-venomous pythons (rock python and sand boa) superficially<br />

look a lot like a Russell’s viper. Out <strong>of</strong> which the sand boa is more similar but<br />

is less commonly found.<br />

5.2.1 Eryx conicus<br />

Sand boa (E); Wali pimbura, Kota pimbura (S)<br />

Mid body colour pattern <strong>of</strong> a Sand Boa.<br />

Simple identification: Smooth mid body scales, and the blotches on its back.<br />

Scales on the back <strong>of</strong> its tail are deeply ridged (keeled/rough) The subcaudal<br />

scales on the underside <strong>of</strong> its tail are single or undivided.<br />

43<br />

A close up view <strong>of</strong> the head <strong>of</strong> a Sand boa showing its<br />

rough and small even sized scales.

Distribution: Found only in the coastal dry zone and arid zone.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal species that moves slowly and is lethargic. It is<br />

rare but can be found burrowed within soil in dry and arid parts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

island. They constrict their prey to immobilize them.<br />

Feeds on: small mammals, geckoes, lizards, skinks, frogs etc.<br />

Reproduction: They give birth to live young.<br />

5.2.2 Python molurus<br />

Rock python (E); Dara pimbura, Ran pimbura (S)<br />

Large sized blotches on mid body.<br />

Simple identification: The pattern <strong>of</strong> blotches on its body. The subcaudal scales<br />

on the underside <strong>of</strong> its tail are single or undivided.<br />

44<br />

Close up <strong>of</strong> head showing the markings <strong>of</strong> an arrow pointing towards head, and<br />

scales <strong>of</strong> different sizes.<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Size: 600 cm<br />

Colouration: Whitish or yellowish with three rows <strong>of</strong> large sized blotches<br />

on back. Colours vary <strong>from</strong> a light brownish tinge to a dark brown. The row<br />

<strong>of</strong> blotches on the back is much larger than the rows on the side <strong>of</strong> body.<br />

Ventral or the underside is cream with small dark brown or black spots.<br />

Distribution: < 2000 m asl<br />

Behavior: A slow moving nocturnal species, but if threatened will move fast to<br />

hide. If threatened they will also coil and warn by hissing several times before<br />

attempting to bite. It is a highly camouflaged species that lives amongst leaf<br />

litter, and well-adapted as an ambush predator. Uncommon but can be found in<br />

forests, and in semi-aquatic environments. It is also well-adapted to climb trees.<br />

They constrict their prey to immobilize them.

Toxicity: <strong>Deadly</strong> venomous<br />

Size: 30-40 cm<br />

Colouration: Light brown or pale earthy brown with a series <strong>of</strong> dark brown<br />

spots outlined with whitish lines on back. On its head there is a distinct <strong>of</strong>f-white<br />

marking which may look like an arrow, or the foot print <strong>of</strong> a bird, or a crucifix.<br />

Ventral or the underside is <strong>of</strong>f white to light brown, with small dark brown spots.<br />

The vestigial<br />

hind limbs <strong>of</strong><br />

Python mollurus<br />

(Rock Python).<br />

Feeds on: Large to small mammals (except those that are carnivorous and<br />

very large species), flying mammals, small sized crocodiles, land monitors,<br />

birds etc. They constrict their prey to immobilize them.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 12- 40 eggs, and are the only snakes in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong><br />

that protect and incubate their eggs.<br />

5.3 Echis carinatus<br />

Saw scaled viper (E); Wali polanga (S)<br />

Distinct marking on the head <strong>of</strong> Saw scaled Viper, which may look like an arrow, a<br />

foot print <strong>of</strong> a bird or a crucifix.<br />

Simple identification: The <strong>of</strong>f-white distinct marking on the head.<br />

Costal scales are keeled/rough and identical in size except for the pair just above<br />

the eye (supra ocular) and inter-nasals, which are smooth and larger in size. The<br />

subcaudal scales on the underside <strong>of</strong> its tail are single or undivided.<br />

46<br />

Distribution: Found in the arid and the coastal dry zone.<br />

Behavior: It is an aggressive nocturnal species that is rarely diurnal. When<br />

threatened they coil and make a small warning noise by rubbing their body coils<br />

against each other. It is a highly camouflaged species in its natural habitat which<br />

is sand-mixed dry leaf litter. Potentially aggressive and will attack if provoked.<br />

Has limited distribution, hence uncommon but commonly found in its preferred<br />

habitat, the sand dune forests and surrounding home gardens. During the dry<br />

season, they are commonly seen under palmyrah leaves (Borassus flabellifer),<br />

which have fallen close to wells and places where there is water.<br />

Feeds on: Geckoes, lizards, frogs, small rodents etc.<br />

Reproduction: They give birth to live <strong>of</strong>f spring.

5.4 Non venomous species that<br />

mimic the Saw scaled viper<br />

5.4.1 Boiga triginata<br />

Gamma cat snake (E); Garandi mapila, Ran mapila,<br />

Kaeta mapila (S)<br />

Toxicity: Non venomous<br />

Size: 70-100 cm<br />

Colouration: Light brown or pale earthy brown with a series <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>f white ‘V’<br />

shaped markings outlined in dark brown or black running down its spine. On its<br />

head there is a distinct <strong>of</strong>f whitish ‘Y’ shaped marking. Ventral or the underside<br />

is light yellow, with small dark brown spots on either side.<br />

Distinct ‘Y’ shaped marking on the head <strong>of</strong> a Gamma cat snake.<br />

48<br />

Simple identification: The <strong>of</strong>f whitish distinct ‘Y’ shaped marking on head.<br />

Underside scales on tail or subcaudal scales are divided.<br />

Distribution: Found in the arid, dry and intermediate zones.<br />

Behavior: It is a nocturnal species. When threatened they make a warning noise<br />

by patting its tail on to a surface. Non aggressive, and can be commonly found<br />

on trees, piled up goods, and in and around human settlements etc.<br />

Feeds on: geckoes, lizards, skinks, small birds, small sized bird’s eggs, small<br />

rodents etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 8-12 eggs per clutch.

6. Cobra<br />

There is only one species <strong>of</strong> cobra (Indian cobra or Spectacled cobra) found<br />

in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. It is a deadly venomous species, and is the most commonly<br />

known venomous snake, amongst people in the island.<br />

6.1 Naja naja<br />

Indian cobra, Spectacled cobra (E); Naya, Nagaya (S)<br />

Toxicity: <strong>Deadly</strong> venomous<br />

Size: 180 cm<br />

Colouration: The colour on its back varies <strong>from</strong> dark brown to dark reddish<br />

brown or dark grey to grayish black with white or light yellow cross bars. These<br />

cross bars are either incomplete or complete with sets <strong>of</strong> four to six bands<br />

grouped at times. Hood contains a large usually white-coloured spectacle shaped<br />

marking, and the surrounding area is reddish. The ventral or the underside may<br />

vary <strong>from</strong> white to pale yellow to light brown, while some may have a single<br />

colouration, others may have cross bars or blotching.<br />

50<br />

The prominent, large<br />

spectacle shaped marking<br />

on the hood <strong>of</strong> a cobra<br />

which is commonly<br />

white.<br />

Simple identification: It forms a distinctive hood, raising its body and displaying<br />

the prominent spectacle shaped marking on the head. When the hood has not<br />

expanded, the easiest way to identify this snake is by the observing its rostral<br />

scale, the area below the eye which is outlined in black.<br />

The subcaudal scales on the underside <strong>of</strong> its tail are divided.

Distribution: < 2000 m asl.<br />

Behavior: It is a diurnal species that is rarely nocturnal (but large sized cobras<br />

may be encountered at night very rarely). Commonly found in and around<br />

human settlements, paddy fields, under piled-up goods, piled-up coconut<br />

husks etc. A potentially non-aggressive species, but if threatened or provoked<br />

will expand its hood and warns by its fake attacks.<br />

Feeds on: Small mammals, frogs, lizards, monitors, other snakes, birds and<br />

their eggs etc. Juveniles may consume skinks, geckoes etc.<br />

Reproduction: They lay 20-40 eggs per clutch.<br />

Remarks: Juvenile cobras could be confused with juvenile rat snakes.<br />

Literature cited<br />

1. Smith, E., Manamendra-Arachchi, K. and Somaweera, R. (2008). A new<br />

species <strong>of</strong> coralsnake <strong>of</strong> the genus Calliophis (Squamata: Elapidae) <strong>from</strong><br />

the Central Province <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. Zootaxa. 1847:19–33.<br />

2. Wickramasinghe, L.J.M., Vidanapathirana, D.R., Wickramasinghe,<br />

N. and Ranwella, P.N. (2009). A New Species <strong>of</strong> Rhinophis Hemprich,<br />

1820 (Reptilia: Serpentes: Uropeltidae) <strong>from</strong> Rakwana massif, <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>.<br />

Zootaxa. 2044: 1–22.<br />

52<br />

People <strong>of</strong>ten get confused between the more widespread and harmless Rat snakes<br />

with cobras. The rat snake plays a very important role as a pest controller.<br />

A close-up view <strong>of</strong> the head <strong>of</strong> a Rat Snake showing black lines outlined on scales<br />

bordering the lip, which is the simplest feature that can be used for identification<br />

<strong>of</strong> rat snakes.<br />

3. Maduwage K., Silva A., Manamendra-Arachchi K. and Pethiyagoda R.<br />

(2009). A taxonomic revision <strong>of</strong> the South Asian hump-nosed pit vipers<br />

(Squamata: Viperidae: Hypnale). Zootaxa. 2232:1–28.<br />

4. Gower, D.J. and Maduwage, K. (2011). Two new species <strong>of</strong> Rhinophis<br />

Hemprich (Serpentes: Uropeltidae) <strong>from</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. Zootaxa. 2881:<br />

51–68.<br />

5. Wickramasinghe, L.J.M., Conservation Status <strong>of</strong> the Reptile Fauna <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong><br />

<strong>Lanka</strong>. The 2012 Red List <strong>of</strong> Threatened Fauna and Flora <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. (Un<br />

der review)<br />

6. de Silva, P.H.D.H. (1980). Snake Fauna <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> – with special<br />

reference to skull, dentition and venom in snakes. National Museums <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong><br />

<strong>Lanka</strong>. Colombo. xi + 472 pp.<br />

7. Das, I. and de Silva, A. (2005) A photographic guide to snakes and other<br />

reptiles <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. New Holland publishers (UK). 144 pp.<br />

8. Somaweera, R. (2006) <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>we Sarpayin [in Sinhalese; “<strong>Snakes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sri</strong><br />

<strong>Lanka</strong>”]. WHT Publications, Colombo, <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong> x + 297 pp.<br />

9. Rooijen, J.V. and Vogel, G. (2008). An investigation into the taxonomy<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dendrelaphis tristis (Daudin, 1803): revalidation <strong>of</strong> Dipsas schokari<br />

(Kuhl, 1820) (Serpentes, Colubridae). Contributions to Zoology. 77(1):<br />

29–39.<br />

10. Vogel, G. and Rooijen, J.V. (2011). A new species <strong>of</strong> Dendrelaphis (Ser<br />

pentes: Colubridae) <strong>from</strong> the Western Ghats – India. Taprobanica.<br />

3(2):77–85.

11. De Silva, A., Wijekoon, A.S.B., Jayasena, L., Abeysekera, C.K., Bao,<br />

C.-D., Hutton, R.A. and Warrel, D.A. (1994). Haemostatic dysfunction<br />

and acute renal failure following envenoming by Merrem’s hump-nosed<br />

viper (Hypnale hypnale) in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>: first authenticated case. Transactions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Royal Society <strong>of</strong> tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 88: 209–12.<br />

12. Premawardena, A..P., Gunathilake, S.B. and de Silva, H.J. (1996).<br />

Haemostatic dysfunction following Hypnale hypnale bites. X1V<br />

International congress for Tropical Medicine and Malaria,Nagasaki, Japan.<br />

17– 22.<br />

13. Sellahewa, K. (1997). Lessons <strong>from</strong> four studies on the management <strong>of</strong><br />

snake bite in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. Ceylon Medical Journal. 42: 8–15.<br />

14. Kularatne, S.A.M. and Ratnatunge, N. (1999). Severe systemic effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> Merrem’s hump nosed viper bite. The Ceylon Medical Journal. 44(4):<br />

169–170.<br />

15. Ariaratnam C.A., Thuraisingam, V., Kularatne, S.A.M., Sheriff, M.H.R.,<br />

Theakston, R.D.G., de Silva, A. and Warrell, D.A. (2008). Frequent and<br />

potentially fatal envenoming by hump-nosed pit vipers (Hypnale hypnale<br />

and H. nepa) in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>: lack <strong>of</strong> effective antivenom. The Royal Society<br />

<strong>of</strong> Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 102: 1120–1126.<br />

16. de Silva H.J., Fonseka M.M.D., Gunatilake S.B., Kularatne S.A.M. and<br />

Sellahewa K.H. (2002). Anti-venom for snakebite in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. The<br />

Ceylon Medical Journal. 47(2): 43–45.<br />

17. Whitehall, J.S., Yarlini., Arunthathy., Varan., Kaanthan., Isaivanan. and<br />

Vanprasath. (2007). Snake bites in north east <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. Rural and<br />

Remote Health. 7: 751 1–6.<br />

54<br />

18. de Silva, A. and Ranasinghe, L. (1983). Epidemiology <strong>of</strong> snakebite in <strong>Sri</strong><br />

<strong>Lanka</strong>. Ceylon Medical Journal. 28:144–54.<br />

19. Seneviratne, U. and Dissanayake, S. (2002). Neurological Manifestations<br />

<strong>of</strong> Snake Bite in <strong>Sri</strong> <strong>Lanka</strong>. Journal <strong>of</strong> Postgraduate Medicine. 48: 275–279.<br />

20. Rajapakse, L., (2012) ‘Alarming increase in road accident, deaths,<br />

Island, 9 April (Online). Available at: http://www.island.lk/index.<br />

php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=49371<br />

(Accessed: 6 December 2012).