Gold, Silver and Silk

Gold, Silver and Silk

Gold, Silver and Silk

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

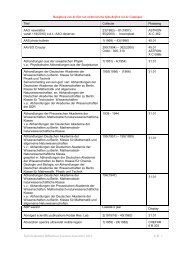

<strong>Gold</strong>, <strong>Silver</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Silk</strong>. Church Textiles in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s 1830–1965<br />

The Beginnings of the Manufacture of Church Textiles in Holl<strong>and</strong>, 1800-1860<br />

At the beginning of the nineteenth century liturgical textiles in Holl<strong>and</strong> were usually made in<br />

one’s own parish from silk that was not specifically intended for ecclesiastical use. New<br />

silken <strong>and</strong> embroidered cloths were imported. The city of Lyons was the most important<br />

supplier of silks for ecclesiastical use. As for gold embroidery, Holl<strong>and</strong> turned mainly to<br />

Belgium. The workshops of J.A.A. van Halle in Antwerp <strong>and</strong> the Grossé family in Bruges<br />

supplied the most precious pieces of embroidery.<br />

The first workshops of any significance in Holl<strong>and</strong> were founded in 1838 – in Oirschot by<br />

Daniël van Kalken, a merchant from Antwerp, <strong>and</strong> in Roermond by François Stoltzenberg, the<br />

son of a German textile merchant. In the 1840s <strong>and</strong> 1850s the workshops of T.A. Rietstap &<br />

Son <strong>and</strong> Van Gennip & Huysmans were founded in The Hague <strong>and</strong> Amsterdam respectively.<br />

Rietstap was solely concerned with the production <strong>and</strong> processing of gold thread. Van Gennip<br />

<strong>and</strong> Huijsman were textile merchants. The first gold embroiderers may have come from<br />

Belgium. Rietstap’s employees were probably trained in Holl<strong>and</strong> – in the production of gold<br />

embroidery for uniforms.<br />

Due to the import of textiles <strong>and</strong> the absence of a native tradition, the influence of France <strong>and</strong><br />

Belgium on the design of church paraments – the generic term for liturgical hangings, cloths<br />

<strong>and</strong> vestments – was overwhelmingly predominant. Until around 1870 the opulent designs of<br />

the Baroque style were extremely popular. In the woven ornamental work colourful <strong>and</strong><br />

luxuriant flower motifs alternated with gold or silver details. The embroidery was worked<br />

entirely in gold or silver thread in high relief. Heavy foliated work, combined with flowers<br />

<strong>and</strong> fruit in relief, covered the orphreys of the paraments. Too little is known of the work of<br />

the early embroidery workshops to say anything definite about the individual styles of the<br />

workshops. We only know of a few pieces of gold embroidery by Stoltzenberg, which are<br />

distinctive for their highly sculptural appearance <strong>and</strong> fine quality.<br />

The Neo-Gothic Style <strong>and</strong> the Production of Church Textiles, 1900-1930<br />

The nineteenth century was an age of increasing self-awareness for Catholics in Western<br />

Europe. In Holl<strong>and</strong> in particular, where they had suffered discrimination since the<br />

Reformation, a great need was felt for self-definition <strong>and</strong> a distinct style. The art of the<br />

Middle Ages, which Catholics saw as an untarnished period, was taken as the model. From<br />

the 1840s onward it prevailed everywhere.<br />

The neo-Gothic style initially had hardly any influence on parament design. Very little was<br />

known about the history of this manufacture <strong>and</strong> the old vestments <strong>and</strong> articles of embroidery<br />

had not yet been rediscovered. The earliest <strong>and</strong> most important publications on the subject<br />

were those of A.W.N. Pugin (Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament <strong>and</strong> Costume, 1844), <strong>and</strong><br />

the French authors Prosper Guéranger (L’année liturgiques, 1841-1866), Victor Gay<br />

(‘Vêtements sacerdotaux’, in: Annales archéologiques, 1844-1848), Arthur Martin (Mélanges<br />

d’archeologie, d’histoire et de littérature, 1848-1868) <strong>and</strong> Charles de Linas (Anciens<br />

vêtements sacerdotaux et anciens tissus conservés en France, 1860-1863) <strong>and</strong> the German<br />

priest Franz Bock (Geschichte der liturgischen Gewänder des Mittelalters, 1859-1871). In the<br />

second half of the nineteenth century the foundations were laid for many textile collections.<br />

The most important collector, Franz Bock, did not hesitate at cutting out pieces of found

textiles for his own collection. His intentions were idealistic; the scattered pieces were worthy<br />

of study <strong>and</strong> imitation. In Holl<strong>and</strong> similar collections were created.<br />

The writer Joseph Alberdingk Thijm was the central figure in the neo-Gothic movement in<br />

Holl<strong>and</strong>. His magazine, Dietsche War<strong>and</strong>e. Tijdschrift voor Nederl<strong>and</strong>sche oudheden, en<br />

nieuwere kunst en letteren (1855-1899), was widely read. The architect Pierre Cuypers<br />

became the most important representative of the neo-Gothic style in Holl<strong>and</strong>. Cuypers<br />

however was associated with Stoltzenberg <strong>and</strong> left the manufacture of church cloths to his<br />

business partner. The priest Gerard van Heukelum was of greater influence. Van Heukelum<br />

was a great admirer of the German priest Franz Bock. In the 1860s he started collecting<br />

fragments of medieval textiles <strong>and</strong> paraments. They formed the basis for the museum of the<br />

Archdiocese of Utrecht, founded in 1872. In 1869 Van Heukelum founded the Guild of Saint<br />

Bernulphus, for devotees of the neo-Gothic style. The most important artists of the Utrecht<br />

neo-Gothic school were the architect Alfred Tepe, the gold <strong>and</strong> silversmith Gerard Brom <strong>and</strong><br />

the sculptor Friedrich Wilhelm Mengelberg. Their ideas were proclaimed in Het Gildeboek<br />

(1873-1881) <strong>and</strong> in the annual reports of the Guild of Saint Bernulphus (1886-1916).<br />

Stoltzenberg <strong>and</strong> Van Gennip & Huijsman were already producing work in the neo-Gothic<br />

style in the 1850s, although their initial output was limited. In the 1870s <strong>and</strong> 1880s however a<br />

new generation emerged on the scene. J. van Hove <strong>and</strong> J. Laumen, who began producing<br />

work in 1863, had both been active for many years in Stoltzenberg’s firm. The same was<br />

probably the case with M. Kluijtmans, who set up shop in Den Bosch in the mid-1860s. At the<br />

end of the 1860s G. Funnekotter began to work as Stoltzenberg’s representative in Utrecht.<br />

The founders of the first Dutch parament firms were succeeded by their sons. François<br />

Stoltzenberg took over from his father in 1875. The youngest son <strong>and</strong> namesake of Daniël van<br />

Kalken took over his firm in Oirschot, while the older sons <strong>and</strong> son-in-law Janssen set up<br />

companies in Breda (1864), Tilburg (1864), Mechelen (1870) <strong>and</strong> Weert (c.1877). C.H. de<br />

Vries who set up business in 1874 in Amsterdam probably received his training with an<br />

existing company. The same was also the case with the third generation of suppliers. Highly<br />

significant were the firms of H. Funnekotter, a nephew of G. Funnekotter, <strong>and</strong> his brother-inlaw<br />

H. Fermin. Both of them started off in Delft, in 1883 <strong>and</strong> 1888 respectively, but soon left<br />

for Rotterdam <strong>and</strong> The Hague.<br />

Convent embroidery workrooms in Holl<strong>and</strong> emerged very late. In 1879 the Sisters of the Poor<br />

Child Jesus, originally based in Aachen, took up residence in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, bringing with<br />

them their workroom, originally founded in 1848. The Kulturkampf in Germany, a policy of<br />

discrimination against Catholics initiated by Bismarck, the Chancellor of the newly united<br />

Germany, had made their existence impossible. Their workroom flourished thanks to the<br />

support they received from Franz Bock. From the 1880s onwards the convent of the<br />

Franciscan sisters of Eemnes produced stylish embroidery, perhaps on Van Heukelum’s<br />

encouragement. While the output of these convents was limited, they were highly influential<br />

in the development of neo-Gothic embroidery.<br />

At the end of the nineteenth century the neo-Gothic was the predominant style. Two types of<br />

ornament can be discerned. First of all there were textiles decorated with foliage. The design<br />

was initially very close to that of the neo-Baroque. Symbolic motifs such as roses, lilies <strong>and</strong><br />

passion flowers were the most common. Their design however gradually became increasingly<br />

influenced by that of medieval decorative work, deriving from illuminated manuscripts <strong>and</strong><br />

gold <strong>and</strong> silver work. In the course of time colourful silk embroidery began to prevail over the<br />

more simple gold <strong>and</strong> silver embroidery.

This decoration genuinely derived from Dutch embroidery, like that which adorned the<br />

paraments of the fifteenth <strong>and</strong> sixteenth centuries. Colourful figures of saints <strong>and</strong> picturesque<br />

Biblical scenes are placed in an architectural setting. By around 1900 the knowledge <strong>and</strong><br />

technical skills of the workshops had become prodigious. Medieval compositions <strong>and</strong><br />

embroidery techniques could be reproduced exactly. The lessons that had been learned from<br />

studying medieval textiles were extremely favourable for the development of embroidery.<br />

From the 1870s onwards the mechanisation of the silk industry had a considerable impact on<br />

the output. The German city of Krefeld in particular became a centre for the supply of church<br />

textiles <strong>and</strong> ready-made ornamental work. From 1859 onwards Franz Bock supplied<br />

fragments of cloth from his own collection for manufacturers to copy. These were mainly<br />

medieval Italian damask silks of Moslem origin, decorated with fabulous animals <strong>and</strong> hunting<br />

scenes. The ‘deer’ cloth <strong>and</strong> the ‘lion’ cloth in particular were enormously popular. At the end<br />

of the century they were followed by heavy late-medieval brocades with pomegranate motifs.<br />

Besides copies of original textiles, a number of patterns were devised based on the formal<br />

idiom of the Middle Ages. Component parts with a neo-Gothic design were also produced in<br />

the weaving mills – crosses for chasubles, gold friezes <strong>and</strong> copes.<br />

New embroidery techniques were devised that achieved a luxurious effect with little effort.<br />

Finely woven textiles <strong>and</strong> painted satin served as a basis for cruder work. The embroidery<br />

machine made it possible to make lines <strong>and</strong> fill whole areas of cloth rapidly. These<br />

specialized techniques meant that the production of some firms exp<strong>and</strong>ed by leaps <strong>and</strong><br />

bounds. Both Belgian <strong>and</strong> German firms produced decorative embroidered items that were<br />

mass-produced <strong>and</strong> which could be purchased separately. In theory the supplier only had to<br />

assemble the cloth <strong>and</strong> embroidery. Extremely cheap products flooded the Dutch market. For<br />

the first time merchants who had no knowledge of the craft of embroidery set up shop in<br />

Holl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

The Neo-Gothic Style <strong>and</strong> Art Nouveau, 1900-1930<br />

In the 1890s a new generation of Catholic artists rebelled against the neo-Gothic style <strong>and</strong><br />

against the factory-produced work that was flooding the market. It was a long while before<br />

the church opened its doors to new styles, such as Art Nouveau, Expressionism <strong>and</strong> abstract<br />

art. People did however increasingly embrace the essence of the art of the Middle Ages,<br />

instead of its outward features. The Beuroner Schule was typical of this approach. This artistic<br />

trend emerged in the late 1860s in the Benedictine monastery of Beuron, but its influence only<br />

began to spread after 1900. Strict geometry <strong>and</strong> the shunning of perspective became departure<br />

points for painting. The outward features of the Beuroner Schule are especially evident in<br />

German church textiles. Some damask articles in the Beuron style were produced by<br />

companies in Krefeld. Watered-down features of the Beuroner Schule can be seen well into<br />

the 1920s in the work of some German firms, such as Krieg <strong>and</strong> Schwarzer in Mainz. From<br />

1910 onwards this firm supplied two new Dutch companies – P.P. Rietfort in Haarlem <strong>and</strong> H.<br />

Verbunt-Van Dijk of Tilburg.<br />

Dutch religious artists also turned to austere geometric work as a source of innovation. Total<br />

abstraction <strong>and</strong> expressionism were still rejected within the church, but the sobriety of the<br />

decorative artists led to a style that was typical of Holl<strong>and</strong> – monumentalism. The decoration<br />

of textiles became more sober <strong>and</strong> abstract.

In the surrounding countries there was less resistance to modern artistic trends. Leo Peters, a<br />

Dutch artist who had settled in Kevelaer, was one of the most important representatives of the<br />

geometrical Art Nouveau style. In Holl<strong>and</strong> this style was influential only in the decoration of<br />

banners; the typical spiral motifs of this style can be found in virtually all the banners of the<br />

second half of the 1910s. Of the most important producers of banners from this epoch – C.M.<br />

van Diemen from Dordrecht, the Van Oven brothers in The Hague <strong>and</strong> G.M.R. Werson from<br />

Rotterdam – none were Catholics. New fashions were therefore more acceptable in this field<br />

than they were in the parament workshops. In Belgium the Art Deco style had a great<br />

influence on design. Starting in the 1920s, the Bruges firm of Grossé exported a vast number<br />

of sober textiles, decorated with appliqué work, to a number of countries including Holl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Representatives of the new generation of Dutch Catholic artists such as Joseph Cuypers, Jan<br />

Dunselman <strong>and</strong> Theo Molkenboer sent their designs for manufacture to H. Fermin’s<br />

workshop in The Hague, one of the best in the country. Their work consisted of fine<br />

embroidery, which, while still including figurative work, was set against a golden ground,<br />

surrounded with modern floral motifs <strong>and</strong> soberly framed. With other firms, such as that of H.<br />

Funnekotter in Rotterdam <strong>and</strong> Cox <strong>and</strong> Charles in Utrecht, the innovation consisted mainly of<br />

a greater sobriety in the design of the vestments. They still produced the neo-Gothic style<br />

damasks <strong>and</strong> woven borders, but used them to make wide, flowing vestments with hardly any<br />

ornament. The Sint-Bernulphushuis in Amsterdam, founded in 1925 by the brothers Jan Eloy<br />

<strong>and</strong> Leo Brom,represented this approach.<br />

Monumentalism <strong>and</strong> the German School, 1925-1955<br />

From the end of the 1920s onwards, two trends in Holl<strong>and</strong> reinforced each other –<br />

monumentalism, the typical Dutch style, which was particularly influential in painting, <strong>and</strong><br />

the German School, which had a great influence on embroidery. Monumentalism adhered to<br />

the principles introduced by the Beuroner Schule. Among the most important representatives<br />

of this style were Wally Kraemer <strong>and</strong> Alex Asperslagh. In the second half of the 1920s this<br />

style became more personal, expressive <strong>and</strong> colourful. The artists, of whom the most<br />

important were Humbert R<strong>and</strong>ag <strong>and</strong> Willem Wiegmans, were interested in all art forms <strong>and</strong><br />

did not have any specialized acquaintance with embroidery techniques.<br />

From 1910 onwards there were numerous craft schools in Germany where religious art was<br />

taught. The basic approach was to maintain a unity of material, technique <strong>and</strong> design.<br />

Medieval linen embroidery with figures depicted in a somewhat primitive fashion became the<br />

most important source of inspiration for religious art. In the second half of the 1920s several<br />

German women artists of the primitive school brought this style to Holl<strong>and</strong>, among them<br />

Joanna Wichmann, Hildegard Fischer, Hildegard Michaelis <strong>and</strong> Trude Benning. Dutch<br />

women artists such as Jeanne Nijsten, Gerda Blankenheym <strong>and</strong> Johanna Klijn used a very<br />

similar style. Their output was relatively small, because they were responsible for both design<br />

<strong>and</strong> execution. The founding of two new firms brought about a change. A.W. Stadelmaier <strong>and</strong><br />

his wife Magdalena Glässner, both from Germany, set up an independent workshop in<br />

Nijmegen in 1930, while a textile dealer from Hilversum, J.L. Sträter, founded an embroidery<br />

workshop in the mid-1930s. They became the most important manufacturers of paraments for<br />

Holl<strong>and</strong>. The reigning styles of the 1930s – monumentalism <strong>and</strong> the German School – were<br />

converted into an expressive art form that was typically Dutch. From the second half of the<br />

1930s it was the artist Wim van Woerkom who set the trend in Stadelmaier’s production. In<br />

Sträter’s workshop the monumental artist Wim Nijs was succeeded by Jacques de Wit. The<br />

principles of the German school were enthusiastically seized on <strong>and</strong> transformed in his

colourful designs. These two workshops set the tone for the whole industry until well into the<br />

1950s.<br />

The Benedictine order also made a name for itself. From the 1850s onwards the order had<br />

propagated the return to the original, extremely sober, flowing vestments , but it was well into<br />

the twentieth century before these reforms were accepted. The architect <strong>and</strong> Benedictine<br />

monk Hans van der Laan played a major role here. From 1933 onwards he was in charge of<br />

the parament workroom of the monastery of Saint Paul in Oosterhout. In the early years of the<br />

workroom a great deal of experiment was carried out, both with regards to the models <strong>and</strong> to<br />

the materials <strong>and</strong> ornament. In 1948 Van der Laan began publishing articles about paraments<br />

in Benedictine periodicals. He described the original models in some detail <strong>and</strong> provided<br />

patterns <strong>and</strong> instructions for use. In the 1950s the monastery’s market exp<strong>and</strong>ed. Other<br />

workshops started imitating its models, although in most cases these were in adapted, easierto-wear<br />

versions.<br />

Decline <strong>and</strong> Fall, 1945-1962<br />

In the course of the 1940s <strong>and</strong> 1950s laypeople felt an increasing need to participate in the<br />

liturgy. During Mass priests now faced their congregations, so that decorative work on the<br />

back of their vestments lost their function. The strict control of art from Rome gradually<br />

became more relaxed. Illustrative art vanished <strong>and</strong> a sober, purely abstract design became<br />

increasingly accepted. All this led to great unease <strong>and</strong> stagnation in the world of parament<br />

manufacture. The Second Vatican Council gave the seal of authority to these changes. The art<br />

of embroidery disappeared <strong>and</strong>, with it, the raison d’être of most of the workshops. A few<br />

survived the changes, but they too ran into difficulties due to the decline in church attendance.