DEVELOPMENT

The pdf-version - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

The pdf-version - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The new trends that are appearing in migration are not<br />

limited to work migration. A new type of migration that<br />

is growing rapidly is related to education. Saar Poll’s<br />

recent survey among the 2012 graduates of upper secondary<br />

schools shows that, especially the graduates of<br />

Russian-language schools do not view higher education<br />

in Estonia attractive, and prefer to continue their studies<br />

elsewhere in Europe. As far as the direction of migration<br />

is concerned, during the last few years, return migration<br />

has increased, in parallel with emigration. It is worth noting<br />

that return migration into Estonia is, currently, larger<br />

than emigration from Estonia was in the early 2000s.<br />

Based on the consideration of the aforementioned<br />

factors, some assumptions can be made about the future<br />

course of migration processes. First, although emigration<br />

from Estonia still continues to increase, the potential for<br />

emigration will presumably start to decrease in the next<br />

few years, as the small generations born in the 1990s<br />

arrive at the prime age of migration. Secondly, alongside,<br />

or instead of, permanent migration, a rapid increase is<br />

occurring in the other forms of spatial mobility, the tendency,<br />

which has been termed the new mobility revolution<br />

(Scheller, Urry 2006). Therefore, one can assume that<br />

ever more people, in the future, will live transnational<br />

lives, with one part connected to Estonia, and another<br />

part to some other country.<br />

In an integrating Europe, working, studying, or<br />

seeking new experiences abroad for a longer or shorter<br />

period will become increasingly common. The evidence<br />

from the European Social Survey shows that<br />

among Estonians the percentage of people who have<br />

experience working abroad is one of the highest in<br />

Europe (Mustrik 2011). This suggests that Estonia is<br />

on the forefront of these new developments. Thus,<br />

in summary, one can probably only agree with those<br />

authors who speak about the arrival of a new era — the<br />

migration era — in contemporary population development<br />

(Castles, Miller 2008) and a new mobility<br />

paradigm (Scheller, Urry 2006). All countries have<br />

to adjust to these new realities, and take into account<br />

the fact that today ever more frequently a person’s life<br />

crosses state borders, the same way it once started to<br />

cross the borders of birthplace and local community.<br />

When assessing the consequences of these changes, the<br />

rapid development of modern means of communication<br />

must not be overlooked – these new means have made<br />

cross-border communicating much simpler and less<br />

expensive, and enable to maintain daily contacts with<br />

one’s country of origin from any distance.<br />

1.2.6<br />

Population ageing<br />

Although population ageing is not included among the<br />

basic demographic processes, it is often regarded as<br />

major challenge for contemporary European societies<br />

(EC 2005). Despite the concerns that usually accompany<br />

any discussion of this phenomenon, population ageing<br />

must be considered to be a legitimate outcome of demographic<br />

modernisation. The cause for population ageing<br />

is the major change in the demographic regime mentioned<br />

at the beginning of the chapter, which, in time,<br />

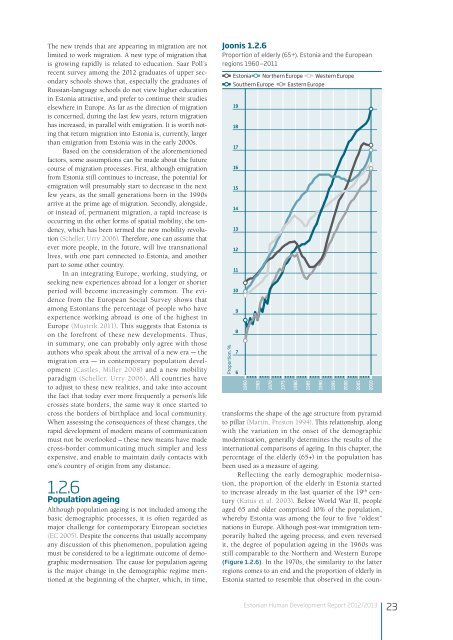

Joonis 1.2.6<br />

Proportion of elderly (65+). Estonia and the European<br />

regions 1960–2011<br />

Proportion, %<br />

Estonia Northern Europe Western Europe<br />

Southern Europe Eastern Europe<br />

19<br />

18<br />

17<br />

16<br />

15<br />

14<br />

13<br />

12<br />

11<br />

10<br />

9<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

1960<br />

1965<br />

1970<br />

1975<br />

1980<br />

transforms the shape of the age structure from pyramid<br />

to pillar (Martin, Preston 1994). This relationship, along<br />

with the variation in the onset of the demographic<br />

modernisation, generally determines the results of the<br />

international comparisons of ageing. In this chapter, the<br />

percentage of the elderly (65+) in the population has<br />

been used as a measure of ageing.<br />

Reflecting the early demographic modernisation,<br />

the proportion of the elderly in Estonia started<br />

to increase already in the last quarter of the 19 th century<br />

(Katus et al. 2003). Before World War II, people<br />

aged 65 and older comprised 10% of the population,<br />

whereby Estonia was among the four to five “oldest”<br />

nations in Europe. Although post-war immigration temporarily<br />

halted the ageing process, and even reversed<br />

it, the degree of population ageing in the 1960s was<br />

still comparable to the Northern and Western Europe<br />

(Figure 1.2.6). In the 1970s, the similarity to the latter<br />

regions comes to an end and the proportion of elderly in<br />

Estonia started to resemble that observed in the coun-<br />

1985<br />

1990<br />

1995<br />

2000<br />

2005<br />

2010<br />

Estonian Human Development Report 2012/2013<br />

23