DEVELOPMENT

The pdf-version - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

The pdf-version - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

118<br />

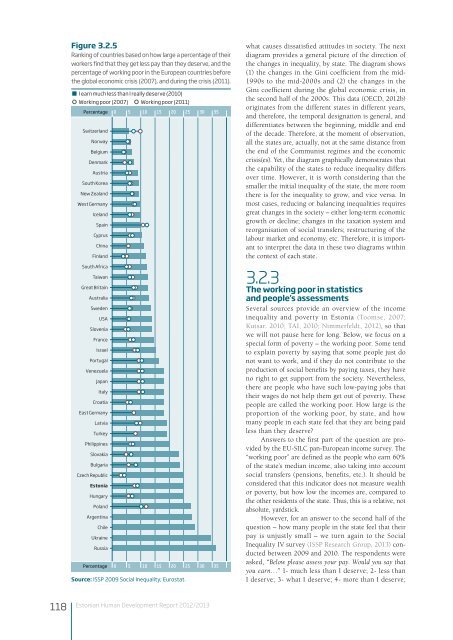

Figure 3.2.5<br />

Ranking of countries based on how large a percentage of their<br />

workers find that they get less pay than they deserve, and the<br />

percentage of working poor in the European countries before<br />

the global economic crisis (2007), and during the crisis (2011).<br />

I earn much less than I really deserve (2010)<br />

Working poor (2007) Working poor (2011)<br />

Percentage 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35<br />

Switzerland<br />

Norway<br />

Belgium<br />

Denmark<br />

Austria<br />

South Korea<br />

New Zealand<br />

West Germany<br />

Iceland<br />

Spain<br />

Cyprus<br />

China<br />

Finland<br />

South Africa<br />

Taiwan<br />

Great Britain<br />

Australia<br />

Sweden<br />

USA<br />

Slovenia<br />

France<br />

Israel<br />

Portugal<br />

Venezuela<br />

Japan<br />

Italy<br />

Croatia<br />

East Germany<br />

Latvia<br />

Turkey<br />

Philippines<br />

Slovakia<br />

Bulgaria<br />

Czech Republic<br />

Estonia<br />

Hungary<br />

Poland<br />

Argentina<br />

Chile<br />

Ukraine<br />

Russia<br />

Percentage 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35<br />

Source: ISSP 2009 Social Inequality; Eurostat.<br />

Estonian Human Development Report 2012/2013 what causes dissatisfied attitudes in society. The next<br />

diagram provides a general picture of the direction of<br />

the changes in inequality, by state. The diagram shows<br />

(1) the changes in the Gini coefficient from the mid-<br />

1990s to the mid-2000s and (2) the changes in the<br />

Gini coefficient during the global economic crisis, in<br />

the second half of the 2000s. This data (OECD, 2012b)<br />

originates from the different states in different years,<br />

and therefore, the temporal designation is general, and<br />

differentiates between the beginning, middle and end<br />

of the decade. Therefore, at the moment of observation,<br />

all the states are, actually, not at the same distance from<br />

the end of the Communist regimes and the economic<br />

crisis(es). Yet, the diagram graphically demonstrates that<br />

the capability of the states to reduce inequality differs<br />

over time. However, it is worth considering that the<br />

smaller the initial inequality of the state, the more room<br />

there is for the inequality to grow, and vice versa. In<br />

most cases, reducing or balancing inequalities requires<br />

great changes in the society – either long-term economic<br />

growth or decline; changes in the taxation system and<br />

reorganisation of social transfers; restructuring of the<br />

labour market and economy, etc. Therefore, it is important<br />

to interpret the data in these two diagrams within<br />

the context of each state.<br />

3.2.3<br />

The working poor in statistics<br />

and people’s assessments<br />

Several sources provide an overview of the income<br />

inequality and poverty in Estonia (Toomse, 2007;<br />

Kutsar. 2010; TAI, 2010; Nimmerfeldt, 2012), so that<br />

we will not pause here for long. Below, we focus on a<br />

special form of poverty – the working poor. Some tend<br />

to explain poverty by saying that some people just do<br />

not want to work, and if they do not contribute to the<br />

production of social benefits by paying taxes, they have<br />

no right to get support from the society. Nevertheless,<br />

there are people who have such low-paying jobs that<br />

their wages do not help them get out of poverty. These<br />

people are called the working poor. How large is the<br />

proportion of the working poor, by state, and how<br />

many people in each state feel that they are being paid<br />

less than they deserve?<br />

Answers to the first part of the question are provided<br />

by the EU-SILC pan-European income survey. The<br />

“working poor” are defined as the people who earn 60%<br />

of the state’s median income, also taking into account<br />

social transfers (pensions, benefits, etc.). It should be<br />

considered that this indicator does not measure wealth<br />

or poverty, but how low the incomes are, compared to<br />

the other residents of the state. Thus, this is a relative, not<br />

absolute, yardstick.<br />

However, for an answer to the second half of the<br />

question – how many people in the state feel that their<br />

pay is unjustly small – we turn again to the Social<br />

Inequality IV survey (ISSP Research Group, 2013) conducted<br />

between 2009 and 2010. The respondents were<br />

asked, “Below please assess your pay. Would you say that<br />

you earn…” 1- much less than I deserve; 2- less than<br />

I deserve; 3- what I deserve; 4- more than I deserve;