DEVELOPMENT

The pdf-version - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

The pdf-version - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

of Estonia, and the other post-Communist countries.<br />

Although the low private contributions in the post-Communist<br />

cases have path-dependent historical consequences,<br />

it is still the lowest in Estonia (private voluntary and<br />

mandatory contributions in Estonia are 0.02%; 0.04% in<br />

Poland; 0.2% in Hungary; 0.9% in Slovakia; and 1.2%<br />

of GDP in Slovenia). As an illustration, Figure 3.1.6 also<br />

includes some liberal, or Anglo-American, welfare regimes,<br />

in order to emphasize the differences from the continental<br />

European model. In Japan, Canada, England, but especially<br />

the U.S., the private social spending comprises a large part<br />

of the total social expenditures (4%, 5%, 6% and 11% of<br />

GDP, respectively). Despite of the differences in private contributions<br />

Estonia and the Anglo-American countries are<br />

similar in terms of total expenditures – which stay below<br />

20% of the GDP. Acknowledging the fact that the Estonian<br />

social policy simultaneously has low public and still<br />

non-existent current private contributions leads us to the<br />

conceptualising of welfare regimes typologies for realising<br />

future social policy alternatives. Although, during the last<br />

decade, social policy has been directed at increasing private<br />

share in social spending, moving toward Anglo-American<br />

social model has not been transparent and publicly recognized<br />

policy agenda.<br />

3.1.3<br />

Types of welfare states and their future<br />

The fundamental dilemma of a welfare state is the<br />

relationship between the market and the state. Public<br />

assistance and insurance are not the only objectives of<br />

the welfare state – it is rather the trade-off between efficiency<br />

and equity that is at the heart of many discussions<br />

addressing the attempts to classify welfare states. There<br />

is no single theoretical framework that gives justification<br />

to state intervention and its dimensions. . Without being<br />

exhaustive, one explanation for this is the concept of<br />

Table 3.1.2<br />

Classification of welfare states<br />

Commodification<br />

Stratification<br />

Reference<br />

countries<br />

Liberal<br />

Conservative<br />

High Medium Low<br />

Dual:<br />

policies<br />

targeted at<br />

supporting<br />

markets<br />

USA,<br />

Great Britain,<br />

New Zealand,<br />

Ireland<br />

High:<br />

opportunities<br />

depend on<br />

status<br />

Germany,<br />

Switzerland,<br />

France,<br />

Austria<br />

Social<br />

Democratic<br />

Low:<br />

policies<br />

targeted<br />

at equality<br />

Sweden,<br />

Finland,<br />

Norway,<br />

Denmark<br />

Source: Table constructed by the authors, based on Esping-Andersen<br />

1990<br />

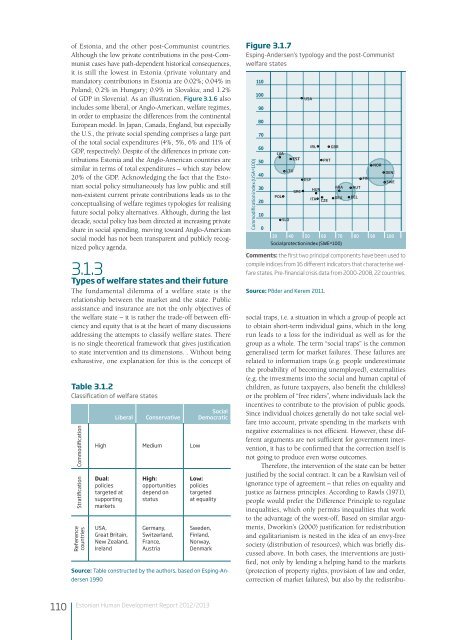

Figure 3.1.7<br />

Esping-Andersen’s typology and the post-Communist<br />

welfare states<br />

Commodification index (USA=100)<br />

110<br />

100<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

LVA<br />

POL<br />

SLO<br />

LTU<br />

EST<br />

GRC<br />

USA<br />

ESP<br />

IRL<br />

HUN<br />

ITA<br />

PRT<br />

CZE<br />

social traps, i.e. a situation in which a group of people act<br />

to obtain short-term individual gains, which in the long<br />

run leads to a loss for the individual as well as for the<br />

group as a whole. The term “social traps” is the common<br />

generalised term for market failures. These failures are<br />

related to information traps (e.g. people underestimate<br />

the probability of becoming unemployed), externalities<br />

(e.g. the investments into the social and human capital of<br />

children, as future taxpayers, also benefit the childless)<br />

or the problem of “free riders”, where individuals lack the<br />

incentives to contribute to the provision of public goods.<br />

Since individual choices generally do not take social welfare<br />

into account, private spending in the markets with<br />

negative externalities is not efficient. However, these different<br />

arguments are not sufficient for government intervention,<br />

it has to be confirmed that the correction itself is<br />

not going to produce even worse outcomes.<br />

Therefore, the intervention of the state can be better<br />

justified by the social contract. It can be a Rawlsian veil of<br />

ignorance type of agreement – that relies on equality and<br />

justice as fairness principles. According to Rawls (1971),<br />

people would prefer the Difference Principle to regulate<br />

inequalities, which only permits inequalities that work<br />

to the advantage of the worst-off. Based on similar arguments,<br />

Dworkin’s (2000) justification for redistribution<br />

and egalitarianism is nested in the idea of an envy-free<br />

society (distribution of resources), which was briefly discussed<br />

above. In both cases, the interventions are justified,<br />

not only by lending a helping hand to the markets<br />

(protection of property rights, provision of law and order,<br />

correction of market failures), but also by the redistribu-<br />

GBR<br />

FRA<br />

DEU<br />

AUT<br />

BEL<br />

FIN<br />

NOR<br />

DEN<br />

SWE<br />

30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100<br />

Social protection index (SWE=100)<br />

Comments: the first two principal components have been used to<br />

compile indices from 16 different indicators that characterise welfare<br />

states. Pre-financial crisis data from 2000-2008, 22 countries.<br />

Source: Põder and Kerem 2011.<br />

110<br />

Estonian Human Development Report 2012/2013