Estonian Human Development Report

Estonian Human Development Report - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

Estonian Human Development Report - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

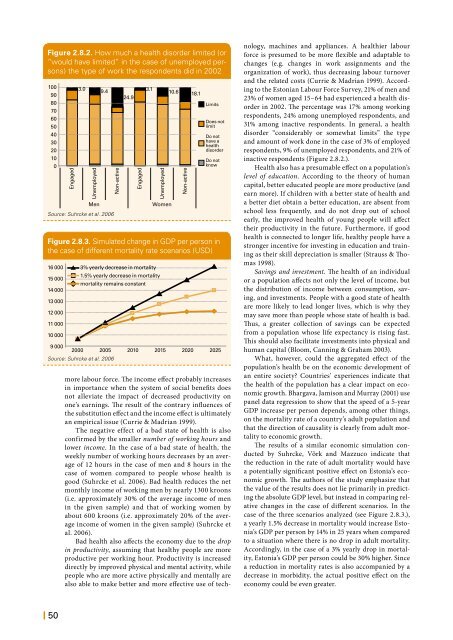

Figure 2.8.2. How much a health disorder limited (or<br />

“would have limited” in the case of unemployed persons)<br />

the type of work the respondents did in 2002<br />

100<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Engaged<br />

3.0<br />

Unemployed<br />

Men<br />

9.4<br />

Source: Suhrcke et al. 2006<br />

Non-active<br />

24.9<br />

Engaged<br />

3.1<br />

more labour force. The income effect probably increases<br />

in importance when the system of social benefits does<br />

not alleviate the impact of decreased productivity on<br />

one’s earnings. The result of the contrary influences of<br />

the substitution effect and the income effect is ultimately<br />

an empirical issue (Currie & Madrian 1999).<br />

The negative effect of a bad state of health is also<br />

confirmed by the smaller number of working hours and<br />

lower income. In the case of a bad state of health, the<br />

weekly number of working hours decreases by an average<br />

of 12 hours in the case of men and 8 hours in the<br />

case of women compared to people whose health is<br />

good (Suhrcke et al. 2006). Bad health reduces the net<br />

monthly income of working men by nearly 1300 kroons<br />

(i.e. approximately 30% of the average income of men<br />

in the given sample) and that of working women by<br />

about 600 kroons (i.e. approximately 20% of the average<br />

income of women in the given sample) (Suhrcke et<br />

al. 2006).<br />

Bad health also affects the economy due to the drop<br />

in productivity, assuming that healthy people are more<br />

productive per working hour. Productivity is increased<br />

directly by improved physical and mental activity, while<br />

people who are more active physically and mentally are<br />

also able to make better and more effective use of tech-<br />

Unemployed<br />

Women<br />

10.6 18.1<br />

Non-active<br />

Limits<br />

Does not<br />

limit<br />

Do not<br />

have a<br />

health<br />

disorder<br />

Do not<br />

know<br />

Figure 2.8.3. Simulated change in GDP per person in<br />

the case of different mortality rate scenarios (USD)<br />

16 000<br />

15 000<br />

14 000<br />

13 000<br />

12 000<br />

11 000<br />

10 000<br />

9 000<br />

3% yearly decrease in mortality<br />

1.5% yearly decrease in mortality<br />

mortality remains constant<br />

2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025<br />

Source: Suhrcke et al. 2006<br />

nology, machines and appliances. A healthier labour<br />

force is presumed to be more flexible and adaptable to<br />

changes (e.g. changes in work assignments and the<br />

organization of work), thus decreasing labour turnover<br />

and the related costs (Currie & Madrian 1999). According<br />

to the <strong>Estonian</strong> Labour Force Survey, 21% of men and<br />

23% of women aged 15–64 had experienced a health disorder<br />

in 2002. The percentage was 17% among working<br />

respondents, 24% among unemployed respondents, and<br />

31% among inactive respondents. In general, a health<br />

disorder “considerably or somewhat limits” the type<br />

and amount of work done in the case of 3% of employed<br />

respondents, 9% of unemployed respondents, and 21% of<br />

inactive respondents (Figure 2.8.2.).<br />

Health also has a presumable effect on a population’s<br />

level of education. According to the theory of human<br />

capital, better educated people are more productive (and<br />

earn more). If children with a better state of health and<br />

a better diet obtain a better education, are absent from<br />

school less frequently, and do not drop out of school<br />

early, the improved health of young people will affect<br />

their productivity in the future. Furthermore, if good<br />

health is connected to longer life, healthy people have a<br />

stronger incentive for investing in education and training<br />

as their skill depreciation is smaller (Strauss & Thomas<br />

1998).<br />

Savings and investment. The health of an individual<br />

or a population affects not only the level of income, but<br />

the distribution of income between consumption, saving,<br />

and investments. People with a good state of health<br />

are more likely to lead longer lives, which is why they<br />

may save more than people whose state of health is bad.<br />

Thus, a greater collection of savings can be expected<br />

from a population whose life expectancy is rising fast.<br />

This should also facilitate investments into physical and<br />

human capital (Bloom, Canning & Graham 2003).<br />

What, however, could the aggregated effect of the<br />

population’s health be on the economic development of<br />

an entire society? Countries’ experiences indicate that<br />

the health of the population has a clear impact on economic<br />

growth. Bhargava, Jamison and Murray (2001) use<br />

panel data regression to show that the speed of a 5-year<br />

GDP increase per person depends, among other things,<br />

on the mortality rate of a country’s adult population and<br />

that the direction of causality is clearly from adult mortality<br />

to economic growth.<br />

The results of a similar economic simulation conducted<br />

by Suhrcke, Võrk and Mazzuco indicate that<br />

the reduction in the rate of adult mortality would have<br />

a potentially significant positive effect on Estonia’s economic<br />

growth. The authors of the study emphasize that<br />

the value of the results does not lie primarily in predicting<br />

the absolute GDP level, but instead in comparing relative<br />

changes in the case of different scenarios. In the<br />

case of the three scenarios analyzed (see Figure 2.8.3.),<br />

a yearly 1.5% decrease in mortality would increase Estonia’s<br />

GDP per person by 14% in 25 years when compared<br />

to a situation where there is no drop in adult mortality.<br />

Accordingly, in the case of a 3% yearly drop in mortality,<br />

Estonia’s GDP per person could be 30% higher. Since<br />

a reduction in mortality rates is also accompanied by a<br />

decrease in morbidity, the actual positive effect on the<br />

economy could be even greater.<br />

| 50