COD E R E D

Download - Code Red: The Critical Condition of Health in Texas

Download - Code Red: The Critical Condition of Health in Texas

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

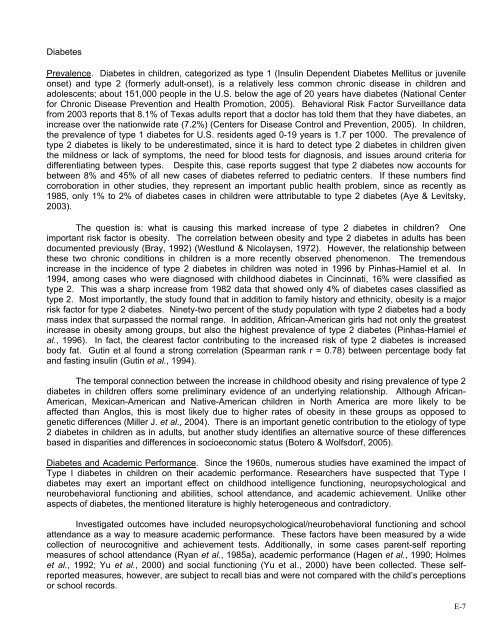

DiabetesPrevalence. Diabetes in children, categorized as type 1 (Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus or juvenileonset) and type 2 (formerly adult-onset), is a relatively less common chronic disease in children andadolescents; about 151,000 people in the U.S. below the age of 20 years have diabetes (National Centerfor Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2005). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance datafrom 2003 reports that 8.1% of Texas adults report that a doctor has told them that they have diabetes, anincrease over the nationwide rate (7.2%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005). In children,the prevalence of type 1 diabetes for U.S. residents aged 0-19 years is 1.7 per 1000. The prevalence oftype 2 diabetes is likely to be underestimated, since it is hard to detect type 2 diabetes in children giventhe mildness or lack of symptoms, the need for blood tests for diagnosis, and issues around criteria fordifferentiating between types. Despite this, case reports suggest that type 2 diabetes now accounts forbetween 8% and 45% of all new cases of diabetes referred to pediatric centers. If these numbers findcorroboration in other studies, they represent an important public health problem, since as recently as1985, only 1% to 2% of diabetes cases in children were attributable to type 2 diabetes (Aye & Levitsky,2003).The question is: what is causing this marked increase of type 2 diabetes in children? Oneimportant risk factor is obesity. The correlation between obesity and type 2 diabetes in adults has beendocumented previously (Bray, 1992) (Westlund & Nicolaysen, 1972). However, the relationship betweenthese two chronic conditions in children is a more recently observed phenomenon. The tremendousincrease in the incidence of type 2 diabetes in children was noted in 1996 by Pinhas-Hamiel et al. In1994, among cases who were diagnosed with childhood diabetes in Cincinnati, 16% were classified astype 2. This was a sharp increase from 1982 data that showed only 4% of diabetes cases classified astype 2. Most importantly, the study found that in addition to family history and ethnicity, obesity is a majorrisk factor for type 2 diabetes. Ninety-two percent of the study population with type 2 diabetes had a bodymass index that surpassed the normal range. In addition, African-American girls had not only the greatestincrease in obesity among groups, but also the highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes (Pinhas-Hamiel etal., 1996). In fact, the clearest factor contributing to the increased risk of type 2 diabetes is increasedbody fat. Gutin et al found a strong correlation (Spearman rank r = 0.78) between percentage body fatand fasting insulin (Gutin et al., 1994).The temporal connection between the increase in childhood obesity and rising prevalence of type 2diabetes in children offers some preliminary evidence of an underlying relationship. Although African-American, Mexican-American and Native-American children in North America are more likely to beaffected than Anglos, this is most likely due to higher rates of obesity in these groups as opposed togenetic differences (Miller J. et al., 2004). There is an important genetic contribution to the etiology of type2 diabetes in children as in adults, but another study identifies an alternative source of these differencesbased in disparities and differences in socioeconomic status (Botero & Wolfsdorf, 2005).Diabetes and Academic Performance. Since the 1960s, numerous studies have examined the impact ofType I diabetes in children on their academic performance. Researchers have suspected that Type Idiabetes may exert an important effect on childhood intelligence functioning, neuropsychological andneurobehavioral functioning and abilities, school attendance, and academic achievement. Unlike otheraspects of diabetes, the mentioned literature is highly heterogeneous and contradictory.Investigated outcomes have included neuropsychological/neurobehavioral functioning and schoolattendance as a way to measure academic performance. These factors have been measured by a widecollection of neurocognitive and achievement tests. Additionally, in some cases parent-self reportingmeasures of school attendance (Ryan et al., 1985a), academic performance (Hagen et al., 1990; Holmeset al., 1992; Yu et al., 2000) and social functioning (Yu et al., 2000) have been collected. These selfreportedmeasures, however, are subject to recall bias and were not compared with the child’s perceptionsor school records.E-7