archaeology

RSGS-The-Geographer-Spring-2015 RSGS-The-Geographer-Spring-2015

- Page 2: TheGeographerarchaeology2015 is a b

- Page 5 and 6: TheGeographer 14-3SPRING 2015Keep E

- Page 9 and 10: TheGeographer 14-7SPRING 2015traced

- Page 12 and 13: 10SPRING 2015Norse GreenlandProfess

- Page 14 and 15: 12SPRING 2015Radiocarbon revolution

- Page 16 and 17: 14SPRING 2015Scotland’s Finest La

- Page 18 and 19: 16SPRING 2015Scotland’s archaeolo

- Page 20 and 21: 18SPRING 2015Reconstructing late Ne

- Page 22 and 23: 20SPRING 2015PhylogeographyProfesso

- Page 24 and 25: 22SPRING 2015Easter IslandDr Paul G

- Page 26 and 27: 24SPRING 2015Walking with the Maasa

- Page 29 and 30: RSGS Examination SchemeKenny Maclea

- Page 31 and 32: Dr Robert D Ballard, RSGS Livingsto

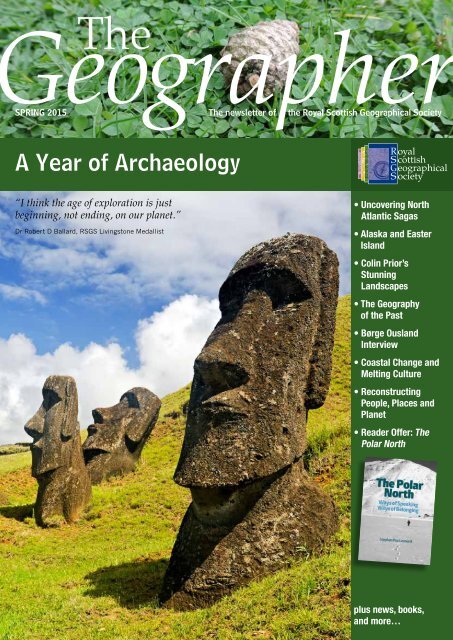

TheGeographer<strong>archaeology</strong>2015 is a busy year. It is designated as a year of<strong>archaeology</strong>, of sheep, of soil, of food and drink,of evaluation, of mud, and of light, amongstother things. 2015 also has a significance in manyareas of current global interest, from the variousnational conflicts and the launch of the EurasianUnion, to the review of Millennium DevelopmentGoals and new negotiations over climate changemitigation.Alongside these geographical issues, 2015 is an importantyear for RSGS. With the support of our members andfunders, we have achieved a great deal over the pastfew years, and I believe we are now in a good positionto achieve a step change in the way we operate and areperceived. We have been gradually closing the gap in theSociety’s operational budget, we have awoken a network ofhundreds of people with an interest in geographical issues,and we have received very positive feedback from a widerange of contacts. So we know that much of what we aredoing is taking RSGS in the right direction.The challenge I took on six years ago was to refresh andmodernise RSGS, and to make the Society financiallysustainable – probably for the first time in its long history.Whilst I like to think that we are achieving the first aim,there is still more to do to achieve the latter. Having putsuch effort into strengthening our credibility (now perhapsat an all-time high) and boosting our profile, 2015 is acritical year for finding new income.I believe we are truly on the verge of transformingRSGS, with its members, its volunteers, its activities, itscommunity, into an even more dynamic, highly-regardedand successful charity. But as Iain Stewart said in the latestannual report, “The‘trick’ of this coming year is to capturethis momentum and channel it towards increasing profile,growing the membership, and finding donations and otherfunding to keep this remarkable small charity running intothe future.”If there is a time to support RSGS and help us continue tooperate at the current level, or to do even more, then 2015is the year we would particularly ask you to help.Mike Robinson, Chief ExecutiveRSGS, Lord John Murray House,15-19 North Port, Perth, PH1 5LUtel: 01738 455050email: enquiries@rsgs.orgwww.rsgs.orgCharity registered in Scotland no SC015599The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the RSGS.Cover image: Easter Island www.shutterstock.comMasthead image: © Mike RobinsonYear of ArchaeologyDig It! 2015 is a year-long celebration of Scottish<strong>archaeology</strong>, co-ordinated by the Society ofAntiquaries of Scotland and Archaeology Scotland.From children taking over museums, and peopleexploring the story of their own local area, to digs,festivals, competitions, hidden relics and lostworlds, there are so many ways for people to get involved. Atits heart, Dig It! 2015 will explore the theme of identities –forged where people, places, the planet and the past meet.See page 19 for more.Fair Maid’s House Visitor CentreThe Fair Maid’s House education and visitor centre is opento the public over the summer months, and all are welcometo come and explore. The normal opening hours this yearwill be 1.00pm to 4.30pm, Tuesdays to Saturdays, 7 April2015 to 24 October 2015; groups can request a specialvisit at other times.Admission is free, butdonations towardsvisitusthe RSGS’s work arealways welcome.The centre is mannedentirely by volunteers,so if you are planninga special journey youmay wish to checkin advance that itwill be open. Emailus or phone us on01738 455050 forfurther informationabout visiting, or toask about being avolunteer guide.Fair Maid’s House Opening Times 20151.00pm to 4.30pm - Tuesday to Saturday - 7 April to 24 OctoberNess of BrodgarOrkney is host to a plethora of archaeological discoveriesof historical artefacts and wonders. In 2014, after 27days of digging at the 5,500-year-old Ness of Brodgar,it came to light that it was most likely a former Neolithictemple, set at the heart of the community, surroundedby Skara Brae, the Ring of Brodgar, the Standing Stonesof Stenness and Maeshowe tomb. The discovery ofbroken weapons (which appeared to have been damageddeliberately) as well as evidence of Neolithic artwork,also suggested that it may have been used as a ‘ritualisticcomplex’ by the people of the island. Work continuesin the area in July and August 2015 and, after a fruitfulsummer last year, there will be high hopes of furtherdiscoveries to come.<strong>archaeology</strong>RSGS: helping to make the connections between people, places & the planet

2SPRING 2015Scotland RocksThe third annual Scotland Rocks Higher Geology and PhysicalGeography conference for pupils and teachers was heldin Perth on 7-8 March. Over 100 people were involved increating a real buzz about all things Geo! Over the weekend,participants pieced together the geological history of thecoastline at St Monans, were inspired by Dr HermioneCockburn (Scientific Director of Our Dynamic Earth) andDallas Campbell (BBC TV presenter), and enthused aboutminerals, tsunamis, soil, climate change, flooding, GIS andstudying geology/geography at university. Teachers also hadopportunities to discuss their experiences of delivering the newNational Qualifications, and to consider the future of Geologyand Earth Sciences in the curriculum.RSGS President, Professor Iain Stewart, prepared a videomessage to welcome everyone to the RSGS’s visitor centreon Saturday evening, and Bruce Gittings and Mike Robinsonpresented Dr Ruth Robinson with an Honorary Fellowship, inrecognition of her outreach work with GeoBus at the Universityof St Andrews. Pupils and teachers alike described the eventas “engaging”, “informative”, “amazing”, “inspiring” and “fun”,and we very much hope to run the event again in 2016.Special thanks go to our volunteers: Lorna Ogilvie, HannahStott, John Simpson, Ben Jackson, Fiona Forbes, JohnLewington, Freda Ross and Peter Buckley.This year’s event was supported by the Mining Institute ofScotland, The Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining,Edinburgh Geological Society, Education Scotland, theUniversity of Dundee and The Open University.RSGS as KE/PE PartnerThe need to determine outstanding research impact onthe economy, society, culture, public policy and services,health, the environment and quality of life – withinthe UK and internationally – is a necessary attributewhen applying for RCUK and wider research funding.Increasingly, pathways to impact are becoming moreprominent in grant-awarding bodies. Universities need todemonstrate productive engagements with a wide rangeof public, private and third-sector organisations, as wellas engagement directly with the public.RSGS can provide a direct conduit to this range ofactivities through designation as a Co-Investigator andResearch Partner, to provide the Knowledge Exchange(KE) and Public Engagement (PE) activity of coreresearch proposals by supporting academics with thisincreasingly key aspect of research grant requirements.RSGS provides a substantial network to disseminateresearch findings to diverse audiences, includingmembers, general public, academics, special interestgroups and decision-makers. We have a cross-sectornetwork of contact with international geographical andrelated societies, universities and schools, nationaland local government, the business community, andthird-sector organisations, throughout Scotland andinternationally, particularly with regard to issuesconcerning climate change.As an education charity, we have expertise in publicisingand popularising scientific research on a wide range ofkey geographical issues:• we have a well-informed membership;• we organise a prestigious national programme of publictalks throughout Scotland;• we produce a high-quality newsletter that tackles someof the more pressing issues in geographical researchdebated today;•we develop curriculum-based activity for schools at alllevels;• we oversee a peer-reviewed academic journal;• we have a well-resourced public visitor and educationcentre located in Perth;• we have a growing following across social mediaplatforms.For further information and to discuss potential projects,please contact Mike Robinson at RSGS HQ.University NewsJohn Martindale (left) from Larbert High, his pupils, and others from Perthand Aberdeen, quizzed BBC TV presenter Dallas Campbell (fourth fromright) about his career, and asked him to sign the atlases in their goodybags, which were kindly donated by HarperCollins publishers.PlacementJohn Simpson, an MSc Water Hazards, Risk and Resiliencestudent from Dundee University, has been working with ourEducation Officer to develop new teaching materials aboutflooding and flood management in Perth. John is now goingback to university full-time to focus on his dissertation, whichwill be about coastal erosion in Portugal. We have enjoyedworking with him, and wish him every success in the future.Tutankhamun’s BeardIn January, reports emerged of a close shave forTutankhamun’s treasured burial mask. It is alleged thatin late 2014 the Pharaoh’s beard was dislodged and wasglued back on using an inadequate adhesive, leaving aclearly visible mark at the join between chin and beard.It was thought that the damage done to the mask mightbe irreversible, but Egyptian authorities have stated that,whilst the repair operation is delicate, the damage is notnecessarily permanent. An investigation into the handlingof some of Egypt’s most treasured artefacts by theMinistry of Antiquities remains ongoing. Hopefully, thecontention surrounding ‘the boy king’ and his beard willnot deliver any further hairy moments.<strong>archaeology</strong>

TheGeographer 14-3SPRING 2015Keep Exploring…Legacies and donations remain one of the most importantways of supporting the RSGS’s work. Many of ourachievements over the past 130 years have only been possiblebecause of money received from RSGS supporters in theirWills, in memory of loved ones, or in donations. Perhaps mostnotably, the Livingstone Medal, one of our most prestigiousawards with which we have recognised a glittering list ofrecipients, was endowed in 1901 by Dr David Livingstone’sfamily in his honour.But you don’t need to be related to a famous explorer to makea difference. Legacy gifts have kept the RSGS going throughlean times in the past, allowing us to continue, to developand to grow. We still receive occasional gifts of maps, books,artefacts and images. But they all require money to preserve,protect and exhibit.Please consider leaving a legacy or giving a donation to helpus continue our work. Contact Mike or Susan at RSGS HQ ifyou would like to discuss this in more detail.Adopt-an-InternWe are delighted to have some extrahelp in the office this spring fromChristopher Mann, who has beenappointed as Events &Media Assistant forthree months, fundedby the ScottishGovernment’s Adoptan-Internscheme.Chris, a recentgraduate, has beenworking particularlyon supportingmembership events and raising publicprofile, and we are sure that he has agreat career ahead of him.WS Bruce MedalWe are calling for nominationsfor the WS Bruce Medal, awardedevery five years for first-handdevelopment of polar science.The recipient should haveadded to an area of researchrelating to a wide spectrum ofwork: Zoology, Botany, Geology,Meteorology, Oceanography or Geography.The award is made by the RSGS ResearchCommittee, and jointly awarded with the RoyalSociety of Edinburgh and the Royal PhysicalSociety. It was first presented in 1926 to JM Wordiefor his oceanographical and geological work in bothpolar regions, and was last presented in 2010 to DrAlison Cook for her work on coastal changes in theAntarctic Peninsula.RSGS GrantsThe RSGS grantsprogramme, which haspart-funded hundreds ofexpeditions and researchprojects over many years,is currently being revisedby the RSGS ResearchCommittee, and weare not inviting newapplications for the timebeing. Grant guidancenotes and an applicationform will be posted onour website as soon asthey are available.University NewsOS Photofit CompetitionOrdnance Survey has launched a photography competition for 2015, looking forthe best photographs of Great Britain to feature on the covers of over 600 papermap titles – the OS Explorer, OS Landranger, and OS Tour series.Nick Giles, Managing Director of Ordnance Survey Leisure, said “We’re reallyexcited about the launch of the photography competition and expect to receivea great selection of images that capture the beauty of Great Britain’s rural and urbanlandscapes. This is a ‘money can’t buy opportunity’ and a chance for your photo to featureon the shelves of high street retailers.”For over 223 years OS has been mapping Great Britain and producing maps which havebecome the envy of the world. In 2014, nearly two million paper maps were printed, seeingan increase in sales for the first time in a decade.OS Photofit will run during 2015, with closing dates staggered for different map bundles.See os.uk/photofit for full details of the competition.

4SPRING 2015Robin Hanbury-Tenison:8 things for 80In 2001, explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison received theRSGS Mungo Park Medal in recognition of his outstandingcontribution to exploration, campaigning for the rights oftribal people, and the creation of a greater understandingof the wider world. Now he is undertaking a series of eightchallenges ahead of his 80th birthday – one for each decade.His first challenge will be the London Marathon on 26 April.Following this he will be climbing the four highest mountainsin the British Isles; skydiving; cave abseiling down the Titanshaft, the deepest pitch in Britain, and out of Peak Cavern,England’s deepest cave; and water-skiing across the EnglishChannel. Clearly you are never too old for adventure.EDINA recognisedThe BartholomewGlobe is awardedfor excellence in theassembly, deliveryor applicationof geographicalinformation throughcartography, GIS andrelated techniques.In February, RSGSBoard Member Margaret Wilkes presented the Globe to PeterBurnhill and the staff of EDINA, for their work in providingonline resources for UK schools and universities.If you would like to nominate somebody for one of ourmedals or awards, then please use the form on our websiteand return it to us here at RSGS HQ.Meet the explorer!Sixteen lucky P1/2 pupils from Forgandenny Primary Schoolcame to visit us to speak to our explorer-in-residence, CraigMathieson. They tried on old and new kit, and saw lots ofphotos from Craig’s adventures in the Arctic and Antarctica.He also told them about the Polar Academy, and hispreparations for his expedition to Greenland in April.“The children have been very enthused with what they heardin this session. When asked in assembly what their dreamsare for the future, many of them answered that they wantedto be an explorer or ‘go to the North Pole’. Brilliant! We arenow doing a whole school ‘dreams for the future’ displayboard.” said teacher Mel Duffy.New UHI Geography DegreeThe University of the Highlands and Islands is offeringa new BSc (Hons) Geography degree course, based inInverness and Stornoway, starting in September 2015.Not only is this a new geography degree in two newlocations in Scotland, it is also an accelerated degreewhich will allow students to graduate in three yearsrather than four. The degree will be delivered throughonline and face-to-face learning, and fieldwork willbe a major component, with residential fieldtrips tothe Cairngorms and the Swiss Alps, as well as localdaytrips. See www.uhi.ac.uk/geography for details.Doug Allan FRSGSAnybody who has enjoyed BBC seriessuch as Ocean Giants and HumanPlanet will have seen the quality ofwildlife cameraman Doug Allan’swork. From scenes shot on thedizzying heights of Mount Everestto close-ups of killer whales huntingin Antarctica, Doug has providedsome of the most memorablewildlife images ever captured. So, hearing the stories behindthese awesome images, from the man described by DavidAttenborough as “the toughest in the business”, was trulyinspirational, and we were thrilled to award Doug (right ofpicture) an Honorary Fellowship of the RSGS, which waspresented to him by RSGS Chairman, Roger Crofts.Doug perfectly embodies our Inspiring People series. We hopethat his achievements can inspire the latest generation ofScotland’s graduates to use their passion and knowledge ofthe natural world to raise awareness of the geographical andenvironmental issues which affect us all.Lewis Pugh’s record-breaking swimsIn February, UN Patron of the Oceans, pioneer swimmer and RSGSFellow Lewis Pugh took on an extreme challenge – five recordbreakingswims in the freezing waters of Antarctica –to gain global support for his campaign to make the Ross Sea aMarine Protected Area. He said, “My hope is that these symbolicswims in this Polar Garden of Eden will bring the beauty andwonder of Antarctica into the hearts and homes of people aroundthe world, so they will urge their governments to protect this uniqueecosystem.”The five swims formed the most challenging and dangerousswimming effort ever undertaken. Donning only Speedo trunks,Lewis broke the world record for the most southerly swim in threeof his five swims. As well as the obvious dangers of subjecting hisbody to the stresses of sub-zero water, Lewis was swimming inseas patrolled by killer whales and leopard seals.130th anniversary appealTo celebrate the RSGS’s 130th anniversary, we hope to createan engaging promotional resource that can be used by RSGSLocal Groups, universities and other partners to explainsomething of our extraordinary heritage, to champion thecause of geography in Scotland, and to inspire more people toget involved in the subject and in the RSGS.We are sending a fundraising appeal to ask our members tohelp us with this project. Please support the appeal if you can.University News

TheGeographer 14-7SPRING 2015traced to a specific eruption. Archaeological and palaeoenvironmentalevidence for Norse settlement in Icelandis placed immediately above one such horizon, the socalledLandnám Ash, dated via ice cores to AD 871 ±2.The presence of stumps and pollen grains of birch treespreserved in peat reveals that the pre-settlement landscapewas much different to that of today. Landnám resulted in animmediate and substantial clearance of birch woodland tocreate hayfields, and this was often accompanied by markedsoil erosion.In many respects, theenvironmental impact ofsettlement on Greenland,beginning with the arrivalof perhaps 14 ships ledby Erik the Red in AD 985,shares many commonalitieswith Iceland. Oneinteresting aspect of recentinvestigations around theruins of the Greenlandicfarms has been the useof pollen and the remainsof insects in tracing theintroduction (accidental orotherwise) and the spreadof ‘unwanted passengers’as a consequence of thesettlement process. Forexample, the appearanceof pollen of sheep’s sorrel(Rumex acetosella) at or soonArtificially-cut irrigation channel at Sandhavn, Greenland,lined with an impermeable clay-rich material. Charcoal withinthe basal lining produced a date of AD 1260-1390.after landnám is such a regular occurrence, thatthis can be widely used as a biological markerfor the onset and spread of settlement. Equallyexciting are demonstrations of irrigationsystems within the pastorally-dominatedfarmlands of the newcomers. The demise ofthe Norse settlements in Greenland duringthe late 14th and early 15th centuries continues to attractdebate, and pollen-based reconstructions of vegetationchange continue to help refine the chronologyof abandonment for individualfarms as part of this process.The material presented hereis just a small sample ofa considerable volume ofresearch. The fossil archivesare nature’s time capsules,capable of being opened bytechniques which are relativelyinexpensive compared tobig science, yet elegant in their power andcomprehensiveness. As investigators workingwithin the spheres of both environmental andcultural history, we continue to be excited byfindings of relevance to both the past and thefuture activities of human communities.“The fossilarchives arenature’s timecapsules.”Á Sondum, Sandoy, Faroe Islands, is located beneath the grass-roofedbuilding at the bottom right of the picture. © K Edwards

8SPRING 2015Tides of changeDr Richard Bates, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of St AndrewsFor most geographers, investigation of past sea level is aimed atunderstanding global climate and associated changes in (palaeo)environment, but for archaeologists there is the“…aroundScotland, keyareas of theselandscapesare todayflooded andlost beneaththe waves.”added dimension of trying to understand therelationship between environmental change andpast human activity. The archaeological elementincludes mapping population distribution,interpreting activity in the landscape at any onetime (eg, settlement, specialized sites such asbutchery or resource procurement, hunting,fishing, gathering and later farming, burial, traveland transport) and, across a wider chronologicalframework, quantifying environmental changeand trying to understand the impact on humanbehaviour.At Last Glacial Maximum, the UK was connectedto the continent by a landmass now submergedbeneath the North Sea, andthere is evidence that thislandscape, coined Doggerlandafter the infamous shallowbanks off the Norfolk coast,was made use of by highlymobile Late Glacial huntergatherers.Furthermore, itremained available to the EarlyHolocene population, even with the changes inrelative sea level and improving climate thatfollowed ice retreat.The settlers of the Early Holocene, known today as Mesolithic,were hunter-gatherers who still practised a mobile lifestylethat made sophisticated use of the different ecological nichesavailable to them. Along the coastal margins, they developeda highly specialized maritime culture, using newly developedseagoing technology in order to harvest marine and littoralresources; further inland, a Mesolithic footprint comprisingassemblages of characteristic flaked stone tools has long beenattested along river valleys such as the Tweed and the Dee, and isnow recognised into high upland areas such as the Cairngorms.The lifestyle of these early hunter-gatherers, however, left littleimpact on the environment, and this can pose a problem forarchaeologists trying to find evidence oftheir presence in the palaeolandscapes, aproblem made worse by the fact that aroundScotland, key areas of these landscapes aretoday flooded and lost beneath the waves.To help address the difficult problems ofreconstructing the inundated landscapeand locating archaeological sites, multidisciplinaryresearch teams involvingarchaeologists, geographers, geologists,FURTHER READINGBicket A (2013), Audit of Current State of Knowledge ofSubmerged Palaeolandscapes and sites (Wessex Archaeology:English Heritage Project no 6231)Coles B (1998), Doggerland: a speculative survey (Proceedings ofthe Prehistoric Society, v64)Fraser SM, Knecht R, Milek K, Noble G, Ovenden S, WarrenG, Wickham-Jones CR (2014), Upper Dee Tributaries Project(Discovery and Excavation in Scotland 2013)geophysicists and computer modellers are necessary. One suchteam, comprising members of the Universities of St Andrews,Aberdeen, Dundee, Trinity Wales and Bradford, has beenattempting to reconstruct lost landscapes across Doggerland,in key locations and at different time slices, and to identifyspecific areas of high archaeological potential within that greaterlandscape.The approach follows two paths. Firstly, the palaeolandscapemust be reconstructed; this usually involves a combination ofgeophysical survey followed by direct sampling to gain corematerial to analyse for specific palaeoenvironmental information.Secondly, the inundation history of sea level rise must bemeasured.For the largest areas, data has been re-processed from seismicsurveys donated by the oil and gas industry to show large andcomplex river valley systems, lakes and estuaries leading intohighly convoluted coastlines. Following the regional approach, itis possible to identify focus areas withgreater potential for finding signatures ofhuman activity. Here, surveys in greaterdetail include new seismic sub-bottomsurvey data together with multibeamsonar data for bathymetry in order toidentify the submerged land surfaces.In Scotland, a programme of researchhas targeted areas around the Orkneyarchipelago. These areas were chosenbecause of their great abundance oflater <strong>archaeology</strong>, in particular from the period immediatelypost-dating the Mesolithic – the Neolithic, when agriculture wasfirst developed in the islands. In Orkney, the record of this timeis exceptionally complete and comprises settlements (suchas Skara Brae), tombs and ritual sites, including the complexof ceremonial monuments at the Heart of Neolithic Orkney(the stone circles of Brodgar and Stenness, and the tomb ofMaeshowe, all assigned World Heritage status). Today thiscomplex is sited in a notable location along the thin isthmus ofland that lies between the waters of the Lochs of Stenness andHarray. Our work has shown a very different picture at the timeof occupation, however. The geophysics, palaeoenvironmentalinformation and sea level record all indicate a true ‘landscape’of gently undulating land, with restricted stretches of freshwater,and marshland that was gradually flooded long after themonuments were built.What did the early farmers make of the inundation of thissacred landscape? How did they react to the changes in resourcelocations around the islands as the relative sea level reachedpresent height? We will never know exactly, but only by recreatingthe lost lands can we start to consider their reactions – reactionsthat have a definite resonance to our own concerns today and intothe future.Gaffney V, Fitch S, Smith D (2009), Europe’s Lost World, TheRediscovery of Doggerland (CBA Research Report 160)Wickham-Jones CR (2014), Prehistoric hunter-gathererinnovations: coastal adaptions. In Cummings V, Jordan P,Zvelebil M (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology andAnthropology of Hunter-gatherers (Oxford University Press)ScARF, Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (www.scottishheritagehub.com)

10SPRING 2015Norse GreenlandProfessor Andrew J Dugmore, Institute of Geography, University of EdinburghArchaeology is known to yield spectacular, prosaic,curious or just plain baffling details of the past.Perhaps surprisingly, in modern <strong>archaeology</strong> thereis a general lack of concern with the earliest, thelargest, and the otherwise unique, as the academicdrive is usually to tackle major questions aboutpeople in the past; to better understand issuessuch as the emergence, organisation, resilience,persistence, transformation and collapse ofsocieties; or to better understand identity,migration and human-environmental interactions.Archaeology has both great synergy with geographyand great potential relevance for today, because the pastprovides us with ‘completed experiments’ and these can helpus to understand the consequences of particular choicesand sets of circumstance. A long-term perspective allows usto track what happened next, often in quite chilling detail,enabling us to understandThe collaborative research brought more about how eventstogether under the umbrella of the unfold and the processesNorth Atlantic Biocultural Organisation which may drive them.(NABO) nicely illustrates bothGiven the rich archivecontemporary trends at the interface presented by the myriadof <strong>archaeology</strong> and geography and of different completedthe evolving story of the Scandinavian experiments of everysettlement of the North Atlantic. See culture there has ever been,www.nabohome.org to find out more. even the partial recordsthat have survived enableus to explore processes of change that can resonate withthe challenges faced by today’s societies. We are not Vikingsor Neolithic farmers (and never willbe), but understanding the choicesopen to them, what they did and theconsequences of those decisions, helpsus to understand processes of changeand the implications of differentoptions. We are almost certainlymoving into times of unprecedentedglobal transformations that will affectthe whole planet. Geographical scalesof change in the past may not havebeen as great as the global scales ofchange we will have to face, but wehave many cases to consider in thepast where profound change rockedentire societies to their very core,affecting their entire world. Given thechallenge of an unknowable future,we can, with the benefit of hindsight, usefully delve into thearchives of the past to understand how people met (or failedto meet) challenges such as climate change, economic stressand culture conflict, and for evidence of any warning signalsthat change was imminent before it actually happened.The Norse settlement of Greenland, with its epic beginningand enigmatic ending, is a well-known but widelymisunderstood story that illustrates key trends in modern<strong>archaeology</strong>, the questions it seeks to answer, its modernrelevance, and its close interactions with geography.Towards the end of the tenth century, the westward pulseof the Scandinavian Viking Age migrations, catalysed by“Archaeologyhas both greatsynergy withgeography andgreat potentialrelevance fortoday.”developments in seafaring, brought hundredsof settlers from Iceland to the south-westernfiords of Greenland. Why they ventured into thedangerous, iceberg-strewn and stormy watersaround Greenland has long been debated. Itmight have been a desperate quest for landto settle at the very edge of the known world.It was, however, more likely to have been amarket-driven economic strategy applied to thesub-Arctic, where the goal was to harness theriches represented by ivory, furs, hides and otherArctic exotica. To secure a suitable base withinGreenland, the Norse established permanent settlementssupported by pastoralism and fodder production, withintroduced sheep, goats, cattle, horses and pigs, and a wellintegratedlarge-scale use of wild resources. A generation laterthese peoples ventured westwards to Newfoundland, but didnot establish a lasting foothold in North America.The Norse colonies in Greenland endured for well over fourhundred years, but why they came to an end some timein the mid-15th century AD has long been debated. It hasbeen seen as a tragic morality tale; of an ill-conceivedEuropean expansion into the sub-Arctic, boosted by arather fanciful naming, buoyed along by anomalously warmmedieval climates, but founded on a misguided attemptto build a very remote farming economy across pockets ofmarginally-viable agricultural land huddled between thegreat inland ice sheet and the seasonally frozen sea. Theidea of an increasingly isolated society, led to its doom by acomplacent and oppressive elite who wilfully failed to respondto changing climate, createsa poignant story. Sad, but notfundamentally threatening,because we may think we are somuch more knowledgeable, havemany more options, and canrespond and adapt and so avoidtheir fate.In recent years however, adifferent, more challengingand disturbing narrativehas developed. We havecome to realise the scaleand effectiveness of Norseadaptations to Greenland, torecognise their communalapproaches, and to identifytheir long-term successes inresource management and conservation. In Greenland, theNorse first encountered mass spring migrations of seals.They successfully switched from the winter cod fishing usedin Iceland to a communal seal hunt, probably inspired byother Norse communal marine mammal hunts of the FaroeIslands and Northern Isles. Faunal evidence from acrossthe Greenland settlements shows that they developed awell-integrated provisioning system that utilised a widerange of wild resources to supplement pastoral production.Animal populations vulnerable to overhunting, such as thenon-migratory harbour seals and caribou, were hunted, yetconserved, over multi-century timescales. A highly specialisedThe long, low grassy mound marks the site of turf-built Norse longhouseØ69. The Scandinavians first established hayfields here; some 500 yearsafter they were abandoned, Inuit farmers have reclaimed them to growfodder for their sheep.

TheGeographer 14- 11SPRING 2015Some Norse ruins are still very well-preserved over 500 yearsafter they were abandoned.exploitationof walrus wasmaintainedfor more thanfour centuries,despite the epic distances involved from the settlements in thesouthwest of Greenland, in both the journeys to the huntinggrounds some 600-900km to the north, and then onwardswith Atlantic traders for the long eastwards journey across theAtlantic to the markets of Europe.The comparatively benign climates that favoured the initialNorse settlement of Greenland deteriorated through the13th century, with a series of abrupt cold spells triggeredby volcanic activity that peaked in 1258-9 AD. In southwestGreenland the summer, vital for nurturing the livestock andgrowing fodder to keep them through the long sub-Arcticwinter, would have been desperately short. Snow would havepersisted around the farms into June and begun building upagain in August. This would have had a devastating impacton the domestic animals which were crucial in underpinningthe Norse subsistence system. But the colonies survived, andisotopic data on human remains and the faunal assemblagesof middens shows how: the Norse responded in perhaps theonly way they could, by moving deeper into the marine foodweb and hunting many more migrating seals. The adaptationwas effective and the settlement endured, but as dependenceon the annual seal migration grew, human populationsdwindled and the farmed areas contracted.By this time the Icelanders had developed trade in bulkycommodities (woollen cloth and dried fish), but the Greenlandeconomy, although intensified, remained specialised andunchanging. Ivory was still the vital product exported toEurope. Greenland cloth production remained limited anddiverse, and did not follow the route of standardisationand mass production adopted across Iceland. And then theworld changed. Plague devastated Norway; theold Royal Norwegian interest in trading withGreenland waned and was not replaced by anyinterest from the newly powerful Hanseaticmerchants. Walrus ivory, once prized for art,ornaments, and most famously the LewisChessmen, fell out of fashion or was replaced bysuperior African elephant ivory. Greenland didnot produce the wool and dried fish they desired.Climate became ever more unfavourable, furtherimpacting pastoral farming and compromisingany efforts to generate wool surplus for export.With the cold came an increasing reliance onmarine mammals, and with the storminesscame increasing risks on the long journey tothe distant walrus hunting grounds. Despitethis, the Norse identified a seemingly elegantsolution to the challenges they faced, tackledthem as an interdependent community, andstuck to a formula that had seen them throughdifficult times in the past. We do not know howthe Norse handled culture contact with theincoming Thule Inuit, but we do know that Thulelifestyles were not adopted by the Norse, asperhaps the solutions that had worked throughthe 13th and 14thcenturies were tooingrained to change.The last recordedcontact with NorseGreenlanders was inthe early 15th century,though archaeologicaldata shows that thecommunity enduredfor several decadesmore. Ultimately,it is likely that thevulnerabilities of theirdwindling populationto changing climate,to the economictransformationssweeping their distantmarkets, and to thechallenges of culturecontact proved toogreat. Despite, orperhaps becauseof their communalintegration andsuccessful priorSurveying a Norse bathhouse.At the site of the old Bishopric at Gardar, only the most massive stoneshave been left behind by the later builders of the modern village.Arctic adaptations, their settlement seems to have been toospecialised, too small and too remote to be able to cope withthe conjunctures of the 15th century. Many questions are stillunresolved, but worth pursuing, as a better understanding ofthe fate of Norse Greenland holds important lessons for ustoday as we grapple on a far larger scale with similar problemsof unprecedented climate changes, economic transformationsand migration.A reconstruction of the small Norse church at Brattahlíð - the modern Greenland settlement of Qassiarsuk.

12SPRING 2015Radiocarbon revolutions and reservoirsDr Philippa Ascough, Scottish Universities Environmental Research CentreArchaeological research is ruled by theconcept of time. Knowing the timing ofevents lets us determine cause from effect,and investigate how human societies havegrown, interacted, evolved, and decayedover the vast span of prehistory. Yet tellingthe time in <strong>archaeology</strong> is not straightforward; we need to putsamples of unknown age on a calendar timescale. Radiocarbon( 14 C) dating provides a key to this problem.Devised in the 1940s by Willard ‘WildBill’ Libby, the method uses the fact thatliving material contains a tiny quantityof radiocarbon, a radioactive carbonisotope. Radiocarbon levels are constantlytopped up during life, but after deaththey start to decay away. This gives us aradiocarbon ‘stopwatch’; by measuring theamount of radiocarbon left in a sample,we can calculate its radiocarbon age.The method was literally a revolution in“...a revolutionin archaeologicalunderstanding...”archaeological understanding when it wasintroduced. Since then there have beenfurther ‘revolutions’; the use of intricatecalibration curves to convert radiocarbon ages to calendar dates,and the use of Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, opening the doorto ever-decreasing sample sizes (eg, individual amino acids fromcooking residues on pottery).One key issue in archaeological research is that of radiocarbon‘reservoir effects’. Carbon atoms circulate quickly in theatmosphere and terrestrial biosphere, yet this is not the case forother carbon reservoirs, particularly the oceans, where a carbonatom may spend thousands of years before being incorporatedinto the samples we analyse. During this time, radioactivedecay occurs, meaning that marine samples appear ‘older’in radiocarbon years than terrestrial samples, even when thetwo are of the same actual calendar age. This is a problem forarchaeological research in regions like Scotland. Here, a wealthof coastal settlements and extensive use of marine resourcesmean that material for dating is often marine; shells, fishbone,or even terrestrial animals fed on marine resources such asseaweed. The solution is to compare radiocarbon dates ofmarine and terrestrial material of the same actual calendar age.The difference between the two gives us acorrection factor to bring marine materialinto line with its terrestrial counterpart.Middens, or prehistoric rubbish dumps,come in handy here, as ancient daily dumpsof material can be identified that containexactly the type of samples needed. Anextensive programme of these measurementshas revealed that the radiocarbon content ofScottish coastal waters has fluctuated by over200 radiocarbon years over the past 8,000years. This knowledge is crucial in properlycalibrating radiocarbon dates on marinesamples from this fascinating zone of NorthAtlantic settlement, but has also highlightedshifts in ocean and climate, providing a toolto investigate these shifts through time, andeven to gain an insight into how they mayhave impacted archaeological communities.Reservoir effects can also complicate datingin freshwater systems (rivers and lakes).Mývatn lake in north Iceland, where ancient carbon flows in tothe water via geothermal activity.Here, ancient carbon can dilute the amount of radiocarbon in thewater if it contains dissolved carbonates (eg, limestone geology),or stored terrestrial carbon (eg, peats, or glacier meltwater).In regions such as Iceland, there is another culprit: geothermalactivity. The conventionally accepted age for the settlementof Iceland is AD 871 ±2, marked by the landnám volcanic ashlayer. Yet an extensive archaeological research programmein the north of Iceland revealed much earlier dates of up toc2000 BC on human and pig bones.The reason was that high geothermaltemperatures released ancient carbonto the freshwater systems from whicharchaeological communities hadobtained fish, waterfowl and theireggs, giving them a very old ‘apparent’radiocarbon age. This was dramaticallydemonstrated by measuring livingmodern fish from a lake in the region,which were found to have ‘apparent’radiocarbon ages of c5,000 years!Studying radiocarbon dynamics inthis environment has enabled us notonly to accurately date some of theearliest inland settlements in Iceland, but also to unravel dietand subsistence patterns of settlers in this pristine landscape,particularly the extent to which they relied upon wild resourcesfor survival.The application of radiocarbon in archaeological researchnow firmly intersects with the palaeoenvironmental andpalaeoecological sciences, particularly the cycling of carbonwithin terrestrial, oceanic and freshwater systems, and theexploitation of these systems by human communities. As thetechnological envelope of radiocarbon dating is continuallypushed, the resolution to which we can interrogate the past isconstantly improving. In modern <strong>archaeology</strong>, the science ofradiocarbon dating has a bright future as both a tracer and atimekeeper in the Earth system.Shell midden on the Western Isles of Scotland: heavy prehistoric use of marine resources. © Dr Mike Church, Durham University

Tree-rings, climate and <strong>archaeology</strong> in ScotlandDr Rob Wilson, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of St Andrews; Dr Coralie Mills, Department ofEarth & Environmental Sciences, University of St Andrews; Miloš Rydval, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences,University of St AndrewsTheGeographer 14- 13SPRING 2015Dendrochronology is the science ofdating growth rings in trees and gleaningenvironmental information from them.Understanding how different environmentalprocesses influence tree growth allowsthe discipline of dendrochronology to beexpanded to a myriad of sub-fields, allowing the assessment ofcurrent and past changes in climate, woodland dynamics and avariety of ecological and environmental issues.“Tree-ring dating has hada profound impact on thearchaeological sciences.”Tree-ring dating has had a profound impact on the archaeologicalsciences, not only by direct dating of wood from buildings andarchaeological material, but also through the calibration of theradiocarbon curve. By sampling many living trees and extendingdatasets back in time using preserved wood of the same species(samples from historical or archaeological and sub-fossilsources), long continuous tree-ring chronologies, greater than4,000 years in length, have been developed for several locationsaround the planet, including Ireland, Scandinavia, central Europeand the Alps, western US, Tasmania and Chile.In Scotland, only around 1% of semi-natural woodland(deciduous and coniferous) remains today, compared to thetheoretical maximum extent during the early/mid Holoceneclimatic optimum around 7,000-8,000 years ago. No currentwoodland stand is truly natural, and all semi-natural woodlandsare in a state of recovery from significant past managementand exploitation. Focusing on Scots pine, it is evident that theCaledonian pine forest has been in decline since 5,000-7,000years ago. This is due to both natural processes and humanclearance, with overall woodland extent hitting an all-time lowin the early 19th century. Such broad-scale observationshave been gleaned mainly from pollen records, butdendrochronological studies since the early 1970s have soughtto add detail. The radiocarbon (rather than tree-ring) datingof preserved sub-fossil pine material found in peat bogs fromareas such as Rannoch Moor, the Cairngorms, Glen Affric andthe Flow Country has been in general agreement with the pollenrecord. However, owing to the irregular growth forms of so-calledbog pines, no dendrochronological dating of such samples waspossible – until recently.Dendrochronology using pine in Scotland is currently undergoinga renaissance. This is in large part due to activities co-ordinatedby the tree-ring laboratory at the University of St Andrews overthe last ten years with colleagues from AOC Archaeology andthe Universities of Swansea and Stockholm. We have developedliving tree chronologies from almost all surviving pine woodlandsaround Scotland. Most trees started growing in the 18thand 19th centuries, but a few rare sites have living trees thatgerminated in the 16th and 15th centuries. Utilising preservedpine material from loch sediments, we have been able to extendliving chronologies in the northern Cairngorms and Glen Affric.The current pine chronology from the northern Cairngorms isnow continuous back to AD 1154, with several radiocarbon dated‘floating’ chronologies showing potential for a continuous 2,000-year record. In fact, preserved pine material has been foundfrom lochs in Rothiemurchus representing most periods overthe last 8,000 years. These new extended tree-ring chronologieshave allowed the development of a well-calibrated climatereconstruction of past summer temperatures for Scotland backto AD 1200, which clearly shows periods substantially cooler thanpresent coinciding with known periods of famine and societaldisruption (eg, the late 17th century).Finally, the dating of historic buildingsconstructed using pine in Scotland hadalso not been possible until recently. Theexpansion of the pine chronology networkin time and space (including sites inScandinavia), alongside the development ofnew analytical techniques, is now changing this situation. As anexample, we can now date a number of pine cruck frame cottagesacross the Highlands, with ages clustering in the late 18th andearly 19th centuries. Many timbers from other historic buildingsand archaeologicalsites are inthe process ofbeing sampledand analysed,with anticipateddates in the latemedieval period.Besides providingprecise dates forour built heritage,their analysis,along with thedating of theloch sedimentsub-fossilmaterial, will alsocontribute to ourunderstanding ofpast woodlanduse andmanagement.This is an excitingtime for Scottishdendrochronologyand we thankfullyacknowledgesupport from theCarnegie Trust,Leverhulme Trust,and the NaturalEnvironmentResearchCouncil. Seewww.st-andrews.ac.uk/~rjsw/ScottishPine formore informationabout the ScottishPine Project.Black dots = Network of sampled living tree pine sites.Red dots = Locations where loch sub-fossil samples have been taken.Comrie Woods. © RSGS / M Robinson

14SPRING 2015Scotland’s Finest Landscapes:The Collector’s EditionColin Prior is one of the finest landscape photographers,matching an eye for natural beauty with the instincts ofa mountaineer, capturing the most magical qualities of alandscape, and communicating something beyond words.“I’m motivated to create imagery that will inspire people,because I believe if I inspire people, I can take them on ajourney,” he says.From his early days, Colin has been intrigued by the waylight plays at dusk and dawn, and he goes to great lengthsto capture this; for example, climbing through the night withthe light of a head torch, carrying a 23.5kg pack, to be at thesummit before dawn. “Light turns a landscape from ordinary,to extraordinary. The idea that I could arrange the elements ofa landscape within the viewfinder of my camera to anticipatethe convergence of light and land excited me from the start.The results can transcend the landscape and transport theviewer to another state of mind.”His first significant shot taken from a Scottish mountainsummit was on a cold day in November 1990, with his fatherHugh. It was of the peaks of Glencoe as the sun set over BenStarav at the head of Loch Etive, and this image is the oneColin considers to be his ‘signature’. “It really awakened me tothe potential of shooting at elevation at dusk and dawn.”Colin often climbs alone, but many times he is accompaniedby his father, to whom he dedicates this collection of his work.Scotland’s Finest Landscapes is an edition of 200 of the verybest of Colin’s Scottish landscape panoramas, arrangedby region, and complemented by maps that pinpoint thelocations of every shot, insights into Colin’s methods, personalstories and anecdotes, and interviews with conservationists.It is a large landscape-format cloth-covered hardback in aclamshell box, an ideal present for armchair travellers andphotographers, and available from leading independentbookshops, specialist outdoor shops, and direct from www.colinprior.co.uk for only £75.00.Top right - Traigh Scarasta, Sound of Taransay, Isle of Harris, Western Isles.Middle right - River North Esk, Glen Esk, Angus. Below - Marsco and Garbh-bheinn, Red Cuillin, from Blaven, Skye, Highland.

TheGeographer 14- 15SPRING 2015

16SPRING 2015Scotland’s archaeological heritageDiana Murray, Joint Chief Executive, RCAHMSJames Hepher, Adam Welfare and Ian Parker ofRCAHMS, on Hirta, St Kilda. © RCAHMS“…millions ofphotographs, maps,drawings anddocuments aboutarchaeologicalsites, buildings andlandscapes…”For over 100 years the RoyalCommission on the Ancient andHistorical Monuments of Scotland(RCAHMS) has been surveying andrecording the nation’s heritage.Its archaeological programmeincludes specialist surveys coveringphotography, measured drawings,aerial photography, airborne laserscanning, and 3D models.The modern survey programme feedsdirectly into the internationally significant RCAHMS archivewhich includes millions of photographs, maps, drawingsand documents about archaeological sites, buildings andlandscapes, from prehistory to the present day. Some of theoldest material comes from the Society of Antiquaries ofScotland Collection, with unparalleled records by antiquarians,photographers and excavators.We make these records available to the public through ourSearch Room, through publications and exhibitions, andthrough our continually developing online resources. Amongstthese resources, our Canmore database gives access to imagesand information on over 300,000 sites across Scotland, whilethe online mapping service PastMap provides a single gatewayinto every aspect of the historic environment in Scotland, from<strong>archaeology</strong> and historic buildings, to industrial heritage anddesigned landscapes.Surveys and ResearchRCAHMS is working on a range of inspiring projects which seekto reveal more about Scotland’s <strong>archaeology</strong> to the wider publicand professionals alike.The results of extensive fieldwork in the Uists with Comhairlenan Eilean Siar (Western Isles Council) have just beenpublished, which discovered a Neolithic chambered cairn andseveral later-Iron Age houses. A further project with ForestryCommission Scotland cast new light on the Iron Age fort on thesummit of Craig Phadrig, overlooking Inverness. RCAHMS isalso working with universities across the UK on a series of PhDsfunded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council, includingresearch on Early Castles and into Post-medieval Settlements.And we look forward to publishing a new book on our researchinto the archaeological sites on St Kilda later this year.Meanwhile, the Discovering the Clyde programme will engagewith local community groups, academic institutions andinterested individuals to combine research and fieldwork todocument how people have interacted with the River Clydethrough time. Part of this includes the Connected with theClyde project, which is currently investigating heritage sites andmonuments directly connected with the river, and enhancingonline data to improve its capacity for further professionalresearch.Community EngagementWorking with communities forms an integral part of our activeeducation and outreach programme. As well as participating inannual events such as Scottish Archaeology Month, Doors OpenDay, Highland Archaeology Fortnight, and Perth and KinrossArchaeology Month, this year is Dig It! 2015, a year-longcelebration of Scottish <strong>archaeology</strong>. A wide variety of events,from the Orkney Islands to the Scottish Borders, will give youngpeople and adults the chance to discover and tell Scotland’sstories through <strong>archaeology</strong>.With a range of national partners, we will also be participatingin the European Association of Archaeologists Conferencetaking place at the University of Glasgow in September. Held forthe first time in Scotland, this will be an excellent opportunityto share the country’s rich, diverse and unique cultural heritagewith an international audience.This year the Scotland’s Urban Past project, supported by theHeritage Lottery Fund, will work with communities across thenation to explore the rich architectural, social and personalhistories of Scotland’s towns and cities. Andthe Scottish Heritage Angel Awards will launchlater this year, supported by the AndrewLloyd Webber Foundation, to celebrate thecontribution of volunteers across Scotlandwho work to protect, understand and value thehistoric environment.Historic Environment ScotlandThis is an exciting year: in October, HistoricEnvironment Scotland (HES) will be formallyestablished, bringing together RCAHMS andHistoric Scotland to form a new lead publicbody for Scotland’s historic environment.Using the unique skills, experience, knowledgeand expertise of staff, HES will help deliverScotland’s first ever Historic EnvironmentStrategy – Our Place in Time. This will producea resilient, sustainable and effective heritageorganisation, streamlining and improvingcurrent functions to deliver an enhancedservice for the historic environment now andin years to come.General view from the north of Village Bay, Hirta, St Kilda, with a cleit in the foreground, the Ministry of Defenceestablishment, the radar station on Mullach Sgar, and Dun beyond. © RCAHMS

Aerial survey and photographs in <strong>archaeology</strong>Dave Cowley, Aerial Survey Projects Manager, RCAHMSTheGeographer 14- 17SPRING 2015The bird’s-eye view, whether obtained from aerial imageryor by an airborne observer, has made a fundamentalcontribution to <strong>archaeology</strong> over the last 100 years, and forsome landscapes and types of remains the aerial perspectiveis the main basis for understanding the past. And as theoriginal form of remote sensing it continues to do so, even asnew approaches to recording the landscape, such as AirborneLaser Scanning and hyper-spectral imaging, emerge.Finding stuff and recording the landscapeKnowing where the material remains of the past are, andtheir character, is a keystone of archaeological investigationand heritage management. In some landscapes, aerialreconnaissance has generated most of the knowndistributions of past settlement and land use patterns,especially in lowland areas where centuries of agriculturehave progressively levelled and buried the remains of earlieractivities such as digging ditches around settlements orlaying out field systems. Here, prospection during summermonths, most effective in dry years and over well-drainedsoils when differential crop development (‘cropmarks’) canreveal the presence of features such as ditches under theplough soil, has revolutionised knowledge of past landscapes.‘Cropmark’ reconnaissance is a cumulative process, withthe quality and extent of returns very dependent on weather,but in many areas of the UK, forexample, routinely over 75% ofknown site distributions have beenrecorded in this way. The same istrue for ongoing surveys along theheavily indented western seaboard ofScotland, where the majority of intertidalfeatures such as fish traps, kelp grids and slipways havebeen put on record through aerial reconnaissance.“These historic viewscan provide rich andtextured informationnot available on maps”where time-lapsed series are available. Serendipitously,these images may record sites and monuments that havesince been destroyed and ‘reconnaissance’ in the archivesroutinely proves its worth. Indeed, the many tens of millionsof images in national and international archives (eg, ncap.org.uk) and online are a barely explored gold mine for<strong>archaeology</strong> and landscape studies. Beyond these generalapplications, such images may be privileged sources, forexample in the emerging field of conflict <strong>archaeology</strong> wherewartime aerial photographs provide unique information andperspectives.Putting it all togetherWhile putting ‘dotson maps’ is animportant foundationfor knowledge,it is the processof interpretativemapping that buildsunderstandingof patterns andprocesses. Thisis when oftendisarticulated andfragmentarybits ofevidence, collected piecemeal over many years, arecompiled and broader patterns emerge. Mappingensures that features are in the right place and at acommon scale, underpinning studies of settlementand land use patterns across space and throughtime. The use of Geographical Information Systems (GIS)to articulate digital data, both imagery and line work, isnow routine, facilitating straightforward data analysis andmanagement.Mapping of the Roman fort, temporary camps and other featuresat Castledykes near Lanark combines cropmarked evidencecollected over many decades. © Crown copyright and databaseright 2015. All rights reserved. OS Licence No 100020548.Aerial reconnaissance routinely makes major contributions to knowledge. The discoveryof a previously unknown cursus monument visible as cropmarking in southeast Scotlandon 8 July 2013 is a significant addition to the corpus of these Neolithic enclosures.© RCAHMS (Aerial Photography Collection). Licensor www.rcahms.gov.ukRecovering lost landscapesExtensive aerial photographic coverage is fairly routinelyavailable dating back to the 1940s, and this ‘archival’imagery (including satellite) affords views of landscapes thathave often been comprehensively altered. Mechanisation ofagriculture, afforestation, urban sprawl and construction ofinfrastructure have all destroyed or obscured large areas ofour landmass, and these historic views can provide rich andtextured information not available on maps. This perspectivehas an enormous importance in informing historic landscapecharacterisation and other broad-brush mapping, in particularPutting it in contextAerial photographs have played an important role in thedevelopment of Landscape Archaeology, providing multiscaledviews of landscapes and sites and making oftenunique contributions to site discovery and documentation.At the heart of a variety of approaches to landscape<strong>archaeology</strong> is a holistic philosophy, and this is where theaerial contribution works best, sometimes providing uniqueinsights, or complementing data such as Airborne LaserScanning (or LiDAR) and multi- and hyperspectral imaging.This is also a world where development in software (so-calledStructure-from-Motion, or soft-bench photogrammetry)is now allowing routine extraction of 3D data from aerialimages that have otherwise been used as 2D wallpaper.Aerial photography demonstrated its utility for <strong>archaeology</strong>in the 19th century, and its contribution grew during the20th century. Now, in the 21st century the contribution ofthe aerial perspective is undiminished, still a very costeffectivemeans of reconnaissance, still a source of uniqueinformation, and still a fascinating medium from which tostudy our surroundings.

18SPRING 2015Reconstructing late Neolithic cultural landscapes in ArgyllDr Richard Tipping, Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling; Dr Aaron Watson, Monumental CreativeHeritage Interpretation; Dr Andrew Jones, Department of Archaeology, University of SouthamptonKilmartin has the most extraordinaryassemblage of Neolithic and Bronze Agearchaeological sites in mainland Scotland.The first image is of a small valley, that ofthe River Add in Argyll, just before it flowsinto the Kilmartin Glen and out to sea. Thesecond image is from the same hillsidesome 4,400 years ago.The reconstruction of prehistoriclandscapes from scientific techniquesis rarely so spatially precise as to berecreated in this way, but such was theneed in trying to understand how peoplein the late Neolithic regarded, livedalongside, and experienced the rockart – beautiful cup-&-ring carvings – beingmade on isolated rock knolls on thevalley floor, the lower-right of the secondimage. No-one has successfully definedthe landscape context of this art, oraddressed questions about who the artwas for. Was it hidden, for example, orshared by all?To begin to answer such questions in anArts & Humanities Research Council grantto Andrew Jones and Richard Tipping,we applied quite standard scientifictechniques but very intensively acrossonly a few square kilometres of ground.So what are you looking at? First, pollenanalysis was used to understand the plantcommunities, but pollen analysis with atwist. We sought two types of pollen site:one that would receive pollen from thehills in general, and a second that wouldgive us the local, fine detail. The uplandsabove the valley floor were wooded, an oakhazel-birchforest that was barely alteredby people from its natural state. There isa sense of herders passing lightly throughthe wood, but no more. The valley floor andsides were, on the other hand, given overentirely to mixed farming. The late Neolithic(some might say the Copper Age) was thefirst time that agriculture of this scale andorderliness appeared in the valley.The pollen site that described this farmedlandscape is very small: you can almoststep over it. It’s marked in the secondimage in the middle-right by alder andwillow bushes around an old river channel.The pollen site is in amongst the fieldsand the meadow. The valley floor was grazed, more likelyby cattle than by sheep from the herb assemblage (Aaron,who made the second image, made them the distinctiveChillingham white cattle), sufficient to open up bare,trampled ground. You can’t quite see the River Add. Therewere many abandoned channels, and radiocarbon dating thepeat that filled them upon abandonment allowed us to positionthe active channel tucked in against the valley side; today ithas shifted to the opposite side of the valley. The river wasshallow and was easily fordable, allowing the procession ofpeople to the rock art.

Society of Antiquariesof ScotlandTheGeographer 14- 19SPRING 2015At around 2400 BC the river was beginningto flood more frequently: overbank sandsare recorded in the peat of the abandonedchannel on the valley floor. This may havebeen a response to changing climate,but may also have been because the riverbegan to receive lots of sediment fromthe valley sides. The lower slopes in thevalley are glacio-fluvial terraces, level ontheir formation but by the late Neolithicmuch degraded. In the second image thesesurfaces have classic round-houses on them.These are a conceit. We didn’t find these,one reason being, perhaps, that traces ofthem were lost by soil erosion. We recordeda metre or two of colluvial sediment in threetransects of boreholes running up this slope,inter-bedded between in situ peat, whichwe couldradiocarbondate. Thisis probablythe bestlong-termrecord of soilerosion in“There is a senseof herders passinglightly through thewood, but no more.”Scotland, and the late Neolithic is one periodof major erosion in the valley. We knewfrom our pollen analyses that farmers weregrowing wheat and probably barley, but wedon’t know where the fields were. We placedthem on this slope, first because the valleyfloor was frequently flooded at this time,and second because we had to explain theamount of soil erosion. However, move tothe right of the last round-houses and you’llsee deep gullies being ripped into an alluvialfan, itself inter-bedded with peat, whichoriginates above the lower slope. Maybeincreasing rainfall was starting to aggravatewhat damage farmers made.So: all this to understand that rock art herein the Add Valley was made in full view offarming communities who walked past itevery day. The acts of carving may have beenspecial occasions, but the art belonged toeveryone.FURTHER READINGJones AM, Freedman D, O’Connor B, Lamdin-Whymark H,Tipping R, Watson A (2011), An Animate Landscape: Rock Artand the Prehistory of Kilmartin, Argyll, Scotland (Macclesfield:Windgather Press)Vina OberlanderFounded in 1780 to study the antiquities and history of Scotland,the Society has provided a forum for debate, discussion and sharingof knowledge. Many of the key objects in the National MuseumsScotland were collected by our members (called Fellows) duringthe 18th and 19th centuries. Today, the Society continues to be animportant player in Scotland’s heritage sector.The Society:• promotes lectures by leading researchers;• publishes current research and books covering all periods ofScotland’s history;• supports archaeological and historical research through grantsand prizes;• responds to Government and other consultations with relevance tothe historic environment of Scotland;• presents regional and international conferences;• delivers initiatives like Dig It! 2015 (see below), and ScARF (ScottishArchaeological Research Framework), a collaboration bringingtogether experts to provide an overview of research in Scotland.Our Fellows (nearly 3,000 worldwide) are a diverse group of people withone common passion – the past. They might be emerging researchers,established academics, heritage experts, or talented lay people with adeep interest in Scotland’s history. See www.socantscot.org for moreinformation.Dig It! 2015Julianne McGrawDig It! 2015, the yearlongcelebration ofScottish <strong>archaeology</strong>, isencouraging everyoneto discover Scotland’sstories! Over a hundredevents are available onthe website, rangingfrom Iron Age cookingand Land Rover safaristo Pictish lecturesand internationalconferences. TheseTraditional <strong>archaeology</strong> is an important part of the Dig It!2015 programme, with lots of opportunities to get involved.© Stuart Vanceevents are happening throughout Scotland and most are free orinexpensive, and open to everyone. Hundreds more will be addedthroughout the year, so keep checking back in!Dig It! 2015 have also been busy promoting collaboration acrossand beyond the sector, leading to some very exciting projects. Apartnership with Immersive Minds, for example, will result in thecreation of an <strong>archaeology</strong>-packed, digital Scotland within the populargame of Minecraft. An upcoming art competition, in partnership withForestry Commission Scotland, will invite members of the public,and professionals, to help us visualise Scotland’sstunning <strong>archaeology</strong>.Visit our website or sign up for our e-newsletter(www.digit2015.com/contact-us) which includesupcoming events, volunteer opportunities, exclusiveproject news and more!

20SPRING 2015PhylogeographyProfessor Keith Dobney, Department of Archaeology, University of Aberdeen“…a unique andextremely rapidevolutionaryprocess that weare still trying tounderstand.”The fossil record allows us to ask manyquestions about organisms in the past;what they looked like, and how theyevolved, adapted and changed throughdeep geological time. The remains ofanimals excavated from archaeologicalsites provide direct insights of morerecent timescales, and specifically allowus to explore the increasingly complexinteractions of animals with humans.One of the most important bio-cultural transitions of the last10,000 years was the shift from huntingand gathering to farming, which saw thedomestication of economically importantplants (eg, wheat, barley, rice) and animals(eg, sheep, goat, cattle, pig). In addition,new ecological niches were created which,in turn, attracted other organisms (eg,small mammals) to human settlementsand fields, some of which became someof our most important pests and diseasevectors.The impact of all this on human societywas profound, major consequences beingrapid population growth, an explosion ofcultural diversity, and significant changesin human health. The domesticationprocess itself also radically changed theanimals involved, creating a unique andextremely rapid evolutionary process thatwe are still trying to understand.Those animals that became the mainstayof human subsistence societies (orindeed the principal pests of, for example,stored grain) dispersed around the globewith new farming cultures. With newscientific techniques, we can explore theprocess of domestication and track the spread of earlyfarming communities through space and time. Applyingphylogeographic principles (linking patterns in the data withplace and time) to genetic information (for example) hasprovided novel insights into where, and how many times,certain wild animals were domesticated, as well as allowingus to track the spread of early farmers across the globe.Our own research on extant Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa)in 2005 revealed a very clear phlyogeographic structure intheir mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), with a clear westwardcline observable from Island South East Asia (ISEA) towestern Europe. These data support the species’ ‘origin’ inISEA and subsequent natural dispersal westward across theold world, which the sparse fossil record suggests is duringthe middle Pleistocene (1,000,000-500,000 years ago).However, assigning modern-day domestic pig mtDNA lineagesto the framework shows multiple matches with wild boarpopulations (at least five) across the Old World, from the FarEast to Europe. This tells us that geographically disparate,and discrete, wild boar populations contributed mtDNA tomodern domestic pigs at some point in the past, somethingthat has been confirmed through recent analyses of ancientDNA from pig remains from archaeological sites.One particular mtDNA clade (circled and arrowed on thediagram), however, shows a clear mismatch between itsgeographic location and its position on the phylogenetic tree,telling us that modern wild boar and domestic pigs fromISEA and the Pacific share a specific mtDNA signature thathad its origin somewhere on continental mainland East Asia.This pattern clearly points to a human-mediated dispersalevent involving wild boar or, more likely, domestic pigs fromcontinental East Asia into ISEA and the Pacific.Human colonisation of the Pacific involved the eastwardspread from mainland East Asia of a series of Austronesianspeakingmaritime cultures, one of the most important (andenigmatic) being that of the Lapita cultural complex. Settlingfor the first time the numerous remote island archipelagosMap of wild boar mtDNA showing phylogeographic structure.of west (and later east) Polynesia, these and later ancestorsof today’s Polynesians carried their domesticated andcommensal plants and animals with them in boats. Theoriesabout their mainland continental origins and subsequentvoyaging routes into the Pacific have largely been dominatedby modern linguistic and rather sparse archaeologicalevidence, all of which have been used to argue for an origin inTaiwan some 6,500 years ago.Our genetic study of both modern and archaeologicalremains of one of the principal domestic animals carried byearly voyagers (the pig) into the Pacific revealed the presenceof a specific mainland Eurasian wild boar mtDNA lineage,likely from Thailand, Vietnam or South West China. Thislineage was incorporated into domestic pig herds in SouthEast Asia during the Neolithic, then dispersed south and theneast with early farming cultures through the Malay peninsula,the Indonesian island chain (crossing the great biogeographicdivide known as the Wallace line), on into Wallacea, NewGuinea and then the western Pacific.Contradicting the long-held ‘out-of-Taiwan’ model, thesedata provide evidence that one of the most importantdomestic animals of past and present Pacific cultures thattravelled into the Pacific with the human colonisers had acompletely different origin and dispersal trajectory thantraditionally thought.

PalaeoentomologyDr Eva Panagiotakopulu, Institute of Geography, University of EdinburghTheGeographer 14- 21SPRING 2015Fossil insect research can provide detailed information aboutenvironmental change and human impact. In the case of theeastern Mediterranean, where there is appropriate preservation,the insects can give fascinating images of past life, includinglandscape clearance, the spread of agriculture, origins ofinsect-borne diseases, and even forensic information forcatastrophic events.One of the best examples for the latter comes from thesettlement of Akrotiri, colloquially the Pompeii of the Aegeanworld, on the island of Santorini, where the Plinian volcaniceruption which destroyed the site in the early 17th century BChas also preserved its ruins under the tephra, including twostoreybuildings, wall paintings, and a range of organic remains.The insect material from the site allows an understanding ofthe development of the fauna from the beginning to the endof the settlement, and the biogeographic information providedshowcases the dynamic nature of interconnections in theeastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age.Some interesting snapshots of past life wereanother outcome of the insect research. Thefaunas from the house of Akhenaten’s Master ofHorses, Ranefer, are typically urban, with flies andother pests, and provide details about an affluentpart of the city. They illustrate typically urbanenvironments, with little evidence for plants or treesand where piles of garbage, including spoilt grainand associated insect faunas, did not seem to beout of place. In terms of information about disease from thesesites, there is evidence for rich relevant faunas and early recordsof several insects which may have played a role in the spread ofinfectious disease; the early urban centres around the Nile mayprovide the key for the origins of insect-borne diseases such asbubonic plague.“Insectscan givefascinatingimages ofpast life.“Further away from the Nile, the Workmen’s Village, accordingto the insect remains, relied on commodities brought fromthe main city, and the faunas include a range of pests ofstored products similar to Amarna, but also indicate ruralenvironments. Two thousand years later, during the Byzantineperiod, insect remains from the monastery at Kom el Nana,built over part of the city at Amarna, give information for achanging environment; the landscape included fruit treesand water around the monastery. The use of irrigation by themonks, either by drawing water from a well or by channels fromthe Nile, is indicated by the palaeoecological evidence.The information acquired from fossil insects about past climateand environments, and the extent of changes in biodiversityover the longer time-frame, are critical for understanding thepast and also provide a window into what lies ahead. Sadly inseveral parts of the eastern Mediterranean, modern agriculture,irrigation and changes in water level are threatening bothnatural deposits and archaeological sites, and with them ourchance to obtain these unique records.A view of the West House at Akrotiri, excavated by C Doumas.Fossil insects may also give forensic insights in terms ofreconstructing unique details about the last moments of thesite. Based on the information from the charred bean weevilswhich were recovered from the large storage jars of the WestHouse in large numbers infesting beans, we were able toassign a season for the volcanic eruption which destroyedthe settlement. The bean weevils are exclusively field pests,which have only one annual cycle and do not reproduce inthe storeroom. The death assemblage in question consists oflarvae, pupae and adults, and it pointed to a single event, adirect result of the eruption. Considering the life cycle of boththe bean weevils and the cultivated peas, the eruption hadprobably taken place some time in June to early July.Further afield, the desiccating environment of the Egyptiandesert also leads to excellent preservation of organic material,fossil insects included. Palaeoenvironmental work on the 14thcentury BC New Kingdom site of Tell el Amarna, which wasAkhenaten’s and Tutankhamun’s capital during their short reign,and the contemporary Workmen’s Village, where the artisansfor the Pharaohs’ tombs lived, has provided new insights intoboth environmental change and human impact in the area.Aggradation of the Nile has significantly reduced the stepbetween the entrenched floodplain and the edge of the city,yet results from fossil insect research show that the areas ofAmarna next to the Nile were green as opposed to desert.Charred bean weevil elytra from theWest House at Akrotiri.Insect pest assemblages from Amarna.Excavations of Ranefer’s house at Amarna, directed by Barry Kemp.