The Correspondence of MiChAEL FArAdAy - IET Digital Library

The Correspondence of MiChAEL FArAdAy - IET Digital Library

The Correspondence of MiChAEL FArAdAy - IET Digital Library

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

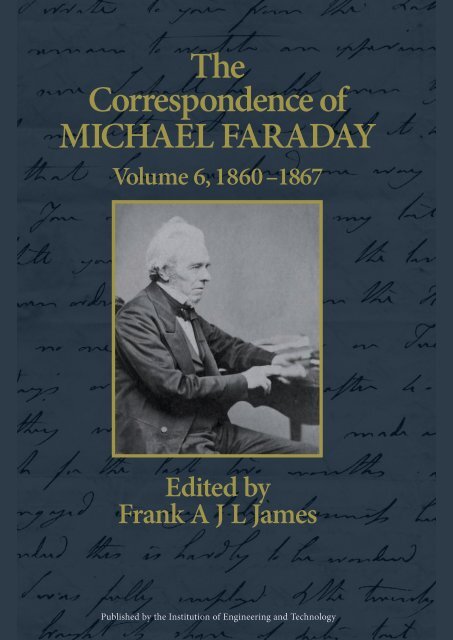

<strong>The</strong><strong>Correspondence</strong> <strong>of</strong>Michael FaradayVolume 6, 1860–1867Edited byFrank A J L JamesPublished by the Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineering and Technology

<strong>The</strong><strong>Correspondence</strong> <strong>of</strong>MICHAEL FARADAYVolume 6

<strong>The</strong><strong>Correspondence</strong> <strong>of</strong>MICHAEL FARADAYVolume 6November 1860–August 1867Undated lettersAdditional letters for volumes 1–5Letters 3874–5053Edited byFrankAJLJamesPublished by the Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineering and Technology

Published by <strong>The</strong> Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineering and Technology, London, United Kingdom<strong>The</strong> Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineering and Technology is registered as a Charity in England & Wales(no. 211014) and Scotland (no. SC038698).© 2012 <strong>The</strong> Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineering and TechnologyFirst published 2012This publication is copyright under the Berne Convention and the Universal CopyrightConvention. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes <strong>of</strong> research orprivate study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means,only with the prior permission in writing <strong>of</strong> the publishers, or in the case <strong>of</strong> reprographicreproduction in accordance with the terms <strong>of</strong> licences issued by the Copyright LicensingAgency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publisherat the undermentioned address:<strong>The</strong> Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineering and TechnologyMichael Faraday HouseSix Hills Way, StevenageHerts, SG1 2AY, United Kingdomwww.theiet.orgWhile the editor and publisher believe that the information and guidance given in this work arecorrect, all parties must rely upon their own skill and judgement when making use <strong>of</strong> them.Neither the author nor publisher assumes any liability to anyone for any loss or damage causedby any error or omission in the work, whether such an error or omission is the result <strong>of</strong>negligence or any other cause. Any and all such liability is disclaimed.<strong>The</strong> moral rights <strong>of</strong> the author to be identified as author <strong>of</strong> this work have been asserted by himin accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.British <strong>Library</strong> Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this product is available from the British <strong>Library</strong>ISBN 978-0-86341-957-7 (hardback)ISBN 978-1-84919-115-9 (PDF)Typeset in India by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd, ChennaiPrinted in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

ContentsPlatesviiConcluding PrefaceixAcknowledgementsxiEditorial Procedures and AbbreviationsxvIntroductionxxvBiographical Registerxlv<strong>The</strong> <strong>Correspondence</strong>1860–1867 1Undated Letters 495Additional letters for volumes 1–5 559Previous Publication <strong>of</strong> Letters 831Bibliography 835Index 857

To Joasia with love

Plates1. Faraday by flashlight, 6 May 1864 Frontispiece2. James Timmins Chance 53. William Crookes 184. Gustav Kirchh<strong>of</strong>f, Robert Bunsen and Henry Roscoe 675. John Hall Gladstone 1986. Edward Frankland 2607. Benjamin Vincent 3248. Henry Bence Jones 4019. John Tyndall 41410. Hampton Court 48411. Jane Barnard 48812. Laying <strong>of</strong> wreaths on Faraday’s grave, 49220 September 1931

Concluding PrefaceI commenced editing Michael Faraday’s correspondence around about 1986with the aim <strong>of</strong> publishing the first volume in time for the bicentenary <strong>of</strong>his birth in 1991 – an aim that was achieved. <strong>The</strong> subsequent four volumesappeared in 1993, 1996, 1999 and 2008. <strong>The</strong> initial research for the project wassupported by a grant from the then Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers administeredthrough their Archives Committee. As time grew closer to publishingvolume one, thought was given at various meetings about how best to do this.It was at one <strong>of</strong> these meetings, at some point in the late 1980s, that I first heardthe term ‘compact disc’, then a relatively new format and restricted to music,as a possible format for publication. Having trained in a department wherethe correspondences <strong>of</strong> Isaac Newton and Henry Oldenburg were publishedin paper volumes by Rupert and Marie Hall, I quickly vetoed that proposal.As a research assistant in the late 1970s to Magda Whitrow, who sadlydied earlier this year, on the project to edit the ISIS Cumulative Bibliography(6 volumes, London, 1971–1984), we were vaguely aware that this wouldprobably be the last major bibliography to be prepared using camera readycards typed with IBM golf ball machines, although such machines at thetime did epitomise the future as portrayed by Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film AClockwork Orange. I don’t think, however, that any <strong>of</strong> us were expecting thetransformation <strong>of</strong> scholarship that has been wrought over the past 30 yearsor so by the development <strong>of</strong> information and communication technology.In my case volume one was produced on an Amstrad with a 20MB harddisc memory (then considered enormous) with the text format coded by symbolssuch as «r», «b», «ni» and many others – a practice that survived downto this volume. <strong>The</strong> text was then handed over to the publisher on ten largefloppy discs, with hard copy photographs <strong>of</strong> the drawings and plates. <strong>The</strong>ncame a Mac laptop and now the Royal Institution’s centralised network whichis PC based. Of course each system had different operating systems whichentailed translation <strong>of</strong> all my files and for which I must acknowledge the good<strong>of</strong>fices <strong>of</strong> David Gooding at the University <strong>of</strong> Bath for doing this. Volume five,by contrast to volume one, was handed over entirely electronically on a CD(!)and this volume on a memory stick.

x<strong>The</strong> development <strong>of</strong> information and communication technology hasnot only altered the mode <strong>of</strong> production <strong>of</strong> the volumes (although not thefinal product) but also how research is conducted. Instead <strong>of</strong> waiting a monthor more for postal correspondence to deliver photocopies <strong>of</strong> manuscripts,email attachments allowed images <strong>of</strong> documents to be sent far more quickly,sometimes within a day. Electronic catalogues <strong>of</strong> archives provided referencesto letters which could not have been located using paper-based catalogues andthis goes a long way to account for many <strong>of</strong> the 306 letters that should havebeen published in earlier volumes. Although carrying out electronic searchesdid slow down the speed <strong>of</strong> editing, I nevertheless felt it incumbent on me thatI should do a thorough electronic check <strong>of</strong> the archives and this did produce anumber <strong>of</strong> letters including some from sources which had already providedletters – on occasion this was due to a paper catalogue only indexing thewriter but not the recipient.But the aspect <strong>of</strong> information technology which really slowed downpublication has been the proliferation <strong>of</strong> high-quality databases which nowprovide practical access to information that even 20 years ago would havebeen inconceivable. At that time it was possible, but prohibitively time consuming,to search through British births, marriage, death and, especially,census records, as well as newspapers, but one needed to have a very goodidea <strong>of</strong> what one was looking for and where. Now all these databases andmany others can be searched. But this does take time and as the accuracy <strong>of</strong>transcriptions and machine-read text can leave much to be desired, locatinginformation at times could be very time consuming. But this process, amongother things, has drastically reduced, compared with earlier volumes, thenumber <strong>of</strong> people referred to as ‘unidentified’.With this volume the project is now complete, though I am sure furtherletters will turn up as soon as the memory stick is handed over!FAJLJRoyal Institution, June 2011

AcknowledgementsIt is with great pleasure and gratitude that I again thank the Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineeringand Technology (formerly the Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers) forthe financial support without which the project to locate, copy and edit allextant letters to and from Faraday would not have been possible. Furthermore,I thank them for the support which made possible the publication <strong>of</strong>this volume. I am grateful to the Royal Institution for the provision <strong>of</strong> allthe essential support they have given for this work and to my friends andcolleagues there for their unceasing support and interest. It is also a pleasureto acknowledge the British Academy for a grant which supported MsMarysia Hermaszewska to make the initial transcriptions <strong>of</strong> most <strong>of</strong> the letterspublished here.I thank the following institutions and individuals for permission topublish the letters to and from Faraday which are in their possession: <strong>The</strong>Royal Institution (and for plates 1 to 11); the Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineeringand Technology (and for plate 12); the Elder Brethren <strong>of</strong> Trinity Housefor the letters in the London Metropolitan Archives; the British <strong>Library</strong>Manuscript Department; the Syndics <strong>of</strong> Cambridge University <strong>Library</strong> and,for the letters in the archives <strong>of</strong> the Royal Greenwich Observatory, theDirector <strong>of</strong> the Royal Greenwich Observatory; the Trustees <strong>of</strong> the WellcomeTrust; Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington; the President andCouncil <strong>of</strong> the Royal Society; the Houghton <strong>Library</strong>, Harvard University;the Oeffentliche Bibliothek der Universität Basle; the American PhilosophicalSociety <strong>Library</strong>, Philadelphia; the Bodleian <strong>Library</strong>, Oxford, and LadyFairfax-Lucy for letters deposited in the Somerville collection; the PierpontMorgan <strong>Library</strong>, New York; <strong>Library</strong> and Information Centre, Royal Society<strong>of</strong> Chemistry; the Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University <strong>Library</strong>;Mr Dennis Embleton: the Archives de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris;Glasgow City Archives; Mr Herbert Obodda; the John Rylands University<strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> Manchester; the Archives <strong>of</strong> the Science Museum <strong>Library</strong>, London;the Wordsworth Trust, Dove Cottage; Mrs Elizabeth M. Milton; the CollegeArchives, Imperial College <strong>of</strong> Science, Technology and Medicine, London; theTrustees <strong>of</strong> the National <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> Scotland; the Athenaeum Club, London;Biblioteca Panizzi, Reggio Emilia; Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript

xii<strong>Library</strong>, University <strong>of</strong> Georgia Libraries; the Huntington <strong>Library</strong>, California;King’s College, London; Lehigh University; Natural History Museum,London; Mrs Rosalind Brennand; the Royal Society <strong>of</strong> Arts; the Society <strong>of</strong>Antiquaries; Somerset Record Office; the Harry Ransom Humanities ResearchCenter, University <strong>of</strong> Texas at Austin; Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei;Aberdeen University <strong>Library</strong>; Brunel Institute, SS Great Britain Trust; theTrustees <strong>of</strong> the British Museum; the Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire,Geneva; Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts deBelgique; Chemical Heritage Foundation; Chicago University <strong>Library</strong>; EdinburghUniversity <strong>Library</strong>; the Francis A. Countway <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medicine,Boston; the Syndics <strong>of</strong> the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Mr George W.Platzman; Miss Jan Reid; Mr Keith Stait-Gardner; the National Art <strong>Library</strong>;the National Research Council Canada; University <strong>of</strong> Newcastle upon Tyne<strong>Library</strong>; Mr Peter Michael Giles; Russian Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences; the Director<strong>of</strong> the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; the Royal College <strong>of</strong> Surgeons; the RoyalHumane Society; Heinz Archive and <strong>Library</strong>, National Portrait Gallery; StAndrews University <strong>Library</strong>; Herr K.W. Vincentz; the late Mr and Mrs S.Aida; the Handschriftenabteilung, Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz,Berlin; University <strong>of</strong> Kentucky, Lexington; Birmingham University<strong>Library</strong>; William Salt <strong>Library</strong>; Dr Y. Watanabe; Dr Anthony Turner; AmericanUniversity; the British Astronomical Association; the Bavarian Academy <strong>of</strong>Sciences; Berlin-Brandenburgischen Ackdemie der Wissenschaften; the BerkshireRecord Office; Boston Public <strong>Library</strong>; California Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology;Mr Chris O’Brien; the Cornwall Record Office; the College <strong>of</strong> Physicians <strong>of</strong>Philadelphia; Cornell University; Columbia University <strong>Library</strong>; D.H. Weinglassand M. Carbonell; Mr Donald K. Wilson; Mr David N. Holt; DukeUniversity Medical <strong>Library</strong>; Durham County Record Office; Exeter University<strong>Library</strong>; <strong>The</strong> Garrick Club; Mr Hal Kass; the Geological Society; Håndskriftafdelingen,Det Kongelige Bibliothek, Copenhagen; Mr Herbert Pratt;Hampshire Record Office; Harvard University Archives; Mr John Herschel-Shorland; Mr Jeff Weber; Liebig Museum, Giessen; Lambeth Palace <strong>Library</strong>;Ms Markella Pervanas-Aktar; the National Archives <strong>of</strong> Scotland; the NielsBohr <strong>Library</strong>; the National <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> Australia; Northumberland RecordOffice; New York Botanical Garden <strong>Library</strong>; Philadelphia College <strong>of</strong> Pharmacyand Science; Mr Paul Heier; <strong>The</strong> Royal Astronomical Society; RensselaerPolytechnic Institute; the Royal Pharmaceutical Society <strong>of</strong> Great Britain; Pr<strong>of</strong>essorRyan Tweney; Salford Archives Centre; Mrs Sheila Elliott; SignaturesGallery; Seeley G. Mudd <strong>Library</strong>; the Surrey Record Office; the State <strong>Library</strong><strong>of</strong> New South Wales, Mitchell <strong>Library</strong>; the Master and Fellows <strong>of</strong> TrinityCollege Cambridge; Mr Timothy Giles; Torquay Natural History Society; UniversitätsbibliothekLeipzig; University College, London; Swansea University;University <strong>of</strong> East Anglia; University <strong>of</strong> North Carolina; University <strong>of</strong> Tennessee,Knoxville; Wigan Archives; Mr William Craig Willan; Herr WolfgangKlose; Worcester Polytechnic Institute. All Crown copyright material in

xiii<strong>The</strong> National Archives and elsewhere is reproduced by permission <strong>of</strong> theController <strong>of</strong> Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.I wish to thank the staff <strong>of</strong> all the institutions listed above for helpingme locate the letters to and from Faraday in their possession and in mostcases providing me with photocopies and answering follow-up questions.Particular thanks should go the Collections and Heritage Team at the RoyalInstitution, Ms Anne Locker and her staff at the Institution <strong>of</strong> Engineeringand Technology, Mr Keith Moore and his staff at the Royal Society and MrAdam Perkins <strong>of</strong> Cambridge University <strong>Library</strong>.Although the following institutions do not have any Faraday lettersin their archives published in this volume, I thank them for answeringqueries concerning this volume: Dundee University Archives, RedbridgeLocal Studies and Archives, the Institution <strong>of</strong> Civil Engineers, Friends’ House,Freemason’s Hall, the Scottish Register Office, the Principal Registry <strong>of</strong> theFamily Division <strong>of</strong> the High Court (in High Holborn), the General RegisterOffice, the London <strong>Library</strong>, the National Gallery, Camden Local Studies andArchives Centre, the Public Record Office <strong>of</strong> Northern Ireland, and the City<strong>of</strong> Westminster Archives Centre.Many friends and colleagues have helped in locating letters and dealingwith queries and I wish to thank the following particularly: Dr MariE.W. Williams, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor John Krige, Dr Shigeo Sugiyama and Pr<strong>of</strong>essorSharon Ruston for doing the initial ground work <strong>of</strong> locating Faradayletters in Paris, Geneva, Japan and Grasmere respectively. I thank DrJ.V. Field (for general help with the Greek and Latin (for which I alsothank Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Vivian Nutton) and for answering various art, historicaland other queries), Mr J.B. Morrell (for help relating to the BritishAssociation and John Phillips), Dr Gloria Clifton (for information on thescientific instrument trade), M. François Mousnier-Lompré (for informationon his ancestor Armand Masselin), Herr Michael Barth (for discussionson the reception <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s work in the German-speaking countries),Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Larry J. Schaaf (for discussions on the history <strong>of</strong> photography),Pr<strong>of</strong>essor W.H. Brock (for help with Liebig and Crookes related queries), MrMichael Harrison and Mr Stephen Rigden (for obtaining Charles Anderson’srecords from the Royal Hospital Chelsea), Mr Dave Padley (for informationon London water companies), Dr Kai Torsten Kanz (for informationon German chemistry), Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Alice Jenkins (for discussionson nineteenth century science and literature), Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Michael Hunter(for Boyle-related queries), Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Peter Bowler (for help with materialin Belfast), Dr R.G.W. Anderson (for help with material in Edinburgh),and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor David Knight (who acted as a court <strong>of</strong> final appeal forobscurities).I thank Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ge<strong>of</strong>frey Cantor and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ryan Tweney fortheir valuable advice over the years, for many stimulating discussions onFaraday and for searching out many Faraday letters which might otherwise

xivhave escaped my attention, especially Tweney who regularly reported whenFaraday letters appeared on the internet. Together with Dr Sophie Forgan, Ialso thank them for their many helpful comments on the introduction.Furthermore, it is with great pleasure that I acknowledge the help andhospitality I have received from many members <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s extended family.In particular, Mr Michael A. Faraday (for providing me with additional informationto that contained in his and the late Dr Joseph E. Faraday’s Faradaygenealogy) and Miss Mary Barnard (who provided me with a detailedgenealogy <strong>of</strong> the Barnard family whose traditional business <strong>of</strong> gold and silversmithingshe continues). I also thank Mrs Isobel Blaikley for continuingto ferret out material from the rest <strong>of</strong> her family and for introducing me tovarious members. <strong>The</strong>se are too numerous to mention fully here, but in thisvolume I should particularly like to note the generosity <strong>of</strong> Mr Martin Conybearein securing the donation to the Royal Institution <strong>of</strong> the album <strong>of</strong> Faradayletters and images that belonged to his family.At this point I would usually thank Pr<strong>of</strong>essor David Gooding for allhis advice, help, inspiration and friendship over the very many years that Ihave been working on Faraday. Unfortunately, after a long and painful illness,he died in December 2009 (Cantor and James (2010); Tweney (2010)). It is amatter <strong>of</strong> huge regret to me that he did not live to see the completion <strong>of</strong> thefinal volume <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s correspondence, a project in part inspired by himand on which he provided me with enormous encouragement and help overthe years.Finally, but not least, I thank my son Christopher (not yet born when theproject began) for translating the letters from the French and my wife, Joasia,for checking those translations and once again translating the letters from theItalian.

Editorial Procedure andAbbreviationsAll letters to and from Faraday which have been located in either manuscriptor in printed form have been included in chronological order <strong>of</strong> writing. <strong>The</strong>term letter has been broadly construed to include not only extracts from letterswhere only these have survived but also reports on various matters whichFaraday submitted to institutions or individuals. What has not been includedare scientific papers written in the form <strong>of</strong> a letter, although letters which weredeemed worthy <strong>of</strong> publication, subsequent to their writing, are included as areletters to journals, newspapers etc. Letters which exist only in printed paraphraseform have not been included. Letters between members <strong>of</strong> Faraday’sfamily, <strong>of</strong> which there are relatively few, are included as a matter <strong>of</strong> course.Of letters between other third parties only those which had a direct effect onFaraday’s career or life are included; the large number <strong>of</strong> letters which simplysay what an excellent lecturer, chemist, philosopher, man, etc, Faraday was,or the letters that are critical <strong>of</strong> him, are not included.<strong>The</strong> aim has been to reproduce, as accurately as the conventions <strong>of</strong>typesetting will allow, the text <strong>of</strong> the letters as they were written. <strong>The</strong> onlyexceptions are that continuation words from one page to the next have notbeen transcribed and, as it proved impossible to render into consistent typesetform the various contractions with which Faraday and his correspondentstended to terminate their letters, all the endings <strong>of</strong> letters are spelt out in fullirrespective <strong>of</strong> whether they were contracted or not. Crossings out have notbeen transcribed, although major alterations are given in the notes.It should be stressed that the reliability <strong>of</strong> the texts <strong>of</strong> letters found onlyin printed form leaves a great deal to be desired as a comparison <strong>of</strong> anyletter in Bence Jones (1870a, b) with the original manuscript, where it hasbeen found, will reveal. <strong>The</strong> punctuation and spelling <strong>of</strong> letters derived fromprinted sources has been retained.As with volumes four and five, this volume contains a number <strong>of</strong> lettersbetween Faraday and John Tyndall. Most <strong>of</strong> these letters now only exist inthe form <strong>of</strong> typescripts prepared by Tyndall’s widow, Louise, as part <strong>of</strong> herproject to write a life <strong>of</strong> her husband that was never completed. Only a very

xvifew original manuscripts <strong>of</strong> these letters have been found. Obvious minortypographical errors (for instance ‘thw’ for ‘the’) have been silently corrected.Otherwise the same editorial policy has been adopted for these typescripts asfor the rest <strong>of</strong> the correspondence.Many <strong>of</strong> the letters that Faraday received from the Board <strong>of</strong> Trade havebeen found only in the form <strong>of</strong> press copies retained by the Board which arenow in <strong>The</strong> National Archives. <strong>The</strong> original letters would have included aprinted heading (giving the address <strong>of</strong> the Board), salutation and a phrase forthe opening sentence. Judging by other letters found in the Board’s papers,the opening sentence would have begun with something to the effect ‘I amcommanded by my Lords <strong>of</strong> the Board <strong>of</strong> Trade to’. Since there was somevariation in the printed texts <strong>of</strong> these letters, no attempt has been made tosuggest what the precise wording for any <strong>of</strong> the letters published here mighthave been.Each letter commences with a heading which gives the letter number,followed by the name <strong>of</strong> the writer and recipient, the date <strong>of</strong> the letter and itssource. <strong>The</strong>re is, occasionally, a fifth line in the heading in which is given thenumber that Faraday allotted to a letter. He only numbered letters to providehimself with a reminder <strong>of</strong> the order <strong>of</strong> a particular series <strong>of</strong> letters whichusually referred to some matter <strong>of</strong> controversy; in this volume Faraday onlynumbered those letters between him and the table turner Thomas Sherratt.<strong>The</strong> postmark is only given when it is used to date a letter or to establish thatthe location <strong>of</strong> the writer was different from that <strong>of</strong> the letterhead.<strong>The</strong> following symbols are used in the text <strong>of</strong> the letters:[some text] indicates that text has been interpolated.[word illegible] indicates that it has not been possible to read a particularword (or words where indicated).[MS torn] indicates where part <strong>of</strong> the manuscript no longer exists(usually due to the seal <strong>of</strong> the letter being placed there)and that it has not been possible to reconstruct the text.[sic]reconstructs the text where the manuscript has been torn.indicates that the peculiar spelling or grammar in the texthas been transcribed as it is in the manuscript. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong>this has been restricted as much as possible to rare cases.Hence, for example, the spellings <strong>of</strong> ‘untill’ is not followedby [sic].[blank in MS] indicates where part <strong>of</strong> the text was deliberately left blank.<strong>The</strong> following abbreviations are used in the texts <strong>of</strong> the letters:BABDCBDCLBachelor <strong>of</strong> ArtsBachelor <strong>of</strong> DivinityCompanion <strong>of</strong> the Order <strong>of</strong> the BathDoctor <strong>of</strong> Civil Law [also given as LLD occasionally]

xviiDMFEFMFRSHCHMCHRHKGKHLHMAMDMEMPMSNBNLPRSPSCRRARHRIRMRNRSSASCTBTHUS(A)USNDeputy Master [<strong>of</strong> Trinity House]Friday EveningForeign Member [<strong>of</strong> the Royal Society]Fellow <strong>of</strong> the Royal SocietyHampton CourtHer Majesty’s CommissionersHer or His Royal HighnessKnight <strong>of</strong> the GarterKnight <strong>of</strong> the Royal Guelphic OrderLighthouseMaster <strong>of</strong> ArtsMedical DoctorMagneto-ElectricMember <strong>of</strong> ParliamentManuscriptNorth Britain [i.e. Scotland]Northern Lighthouse [Commissioners]President <strong>of</strong> the Royal SocietyPublic Schools CommissionRoyalRoyal AcademyRoyal HighnessRoyal InstitutionRoyal Military [Academy]Royal NavyRoyal SocietySociety <strong>of</strong> ArtsSub-committee [for the glass project]Trinity BoardTrinity HouseUnited States (<strong>of</strong> America)United States NavyPostcodes, based on compass points such as W, SW as well as EC (EastCentral) etc, were used in London by the Post Office.Britain did not decimalise its currency until 1971 and is still halfheartedlytrying to metricate its weights and measures, although in scientificand technical writings this latter has been largely completed. During the nineteenthcentury the main unit <strong>of</strong> currency was the pound (£) which was dividedinto twenty shillings (s) <strong>of</strong> twelve pennies (d) each. <strong>The</strong> penny was furthersub-divided into a half (halfpenny) and a quarter (called a farthing). A sumsuch as, for example, one pound, three shillings and sixpence could be written

xviiias 1-3-6 with or without the symbols for the currency values. Likewise twoshillings and six pence could be written as 2/6; this particular coin could becalled half a crown. <strong>The</strong>re was one additional unit <strong>of</strong> currency, the guinea,which was normally defined as twenty one shillings. <strong>The</strong>re is no agreed figureby which the value <strong>of</strong> money in the nineteenth century can be multipliedto provide a modern equivalent, but in 1861 £50 would secure the services<strong>of</strong> a good cook for a year, <strong>The</strong> Times cost 4d, entry to Madame Tussauds 1s,and it was possible to secure a second-class steam ship passage to New Yorkfor £14.<strong>The</strong> following table provides conversion values for the units used inthe correspondence and their value in modern units. For mass only theAvoirdupois system is given as that was most commonly used. But it is importantto remember that both the Apothecaries’and Troy systems were also usedto measure mass and that units in all these systems shared some <strong>of</strong> the samenames, but different values. For conversion figures for these latter (and als<strong>of</strong>or other units not given here) see Darton and Clark (1994).TemperatureTo convert degrees Fahrenheit (F) to degrees Centigrade (C),subtract 32 and then multiply by 5/9.Length1 inch (in or ") = 2.54 cm1 foot (ft or ’) = 12 inches = 30.48 cm1 yard (yd) = 3 feet = 91.44 cm1 fathom = 2 yards = 1.83m1 mile = 1760 yards = 1.6 kmVolume1 cubic inch (ci) = 16.38 cc1 pint = 4 gills = 0.568 litre1 gallon = 8 pints = 4.54 litre1 cubic foot (cf) = 28.32 litre1 bushel = 8 gallons = 36.3 litre1 chaldron = 36 bushels = 1306.8 litreMass1 grain (gr) = 0.065 g1 ounce (oz) = 28.3 g1 pound (lb) = 7000 grains= 16 ounces = 0.453 kg1 stone = 14 pounds = 6.3 kg1 hundredweight (cwt) = 112 pounds = 50.8 kg1 ton = 20 cwt = 1.02 tonne

xix<strong>The</strong> Notes<strong>The</strong> notes aim to identify, as far as has been possible, individuals, papers andbooks which are mentioned in the letters, and to explicate events to whichreference is made (where this is not evident from the letters). In correspondence,writers when discussing individuals with titles used those titles, butas British biographical dictionaries use the family name this is given, wherenecessary, in the notes.<strong>The</strong> biographical register identifies all those individuals who are mentionedin three or more letters (in either text or notes). <strong>The</strong> register provides abrief biographical description <strong>of</strong> these individuals and an indication <strong>of</strong> wherefurther information may be found. No further identification <strong>of</strong> these individualsis given in the notes. Those who are mentioned in one or two lettersare identified in the notes. While information contained in the genealogies<strong>of</strong> various Sandemanian families has been invaluable, this information hasbeen checked against that available in the General Register Office (GRO) andScottish Register Office (SRO). In these cases, and others, where the GRO orSRO is cited, the year <strong>of</strong> death is given followed by the age at death. If thisagrees with information derived from other sources, then the year <strong>of</strong> birth isgiven in preference to the age.References in the notes in the form <strong>of</strong> Faraday (1861c) refer to thebibliography; the following abbreviations are used to cite other sources <strong>of</strong>information:ACACABADBAlKLANBAOBxCPDABDBFDBIDHBSDQBDSBEIERGDAGDMMGROAlumini CantabrigiensesAppletons’ Cyclopedia <strong>of</strong> American BiographyAllgemeine Deutsche BiographieAllgemeines Künster-LexikonAmerican National BiographyAlumni OxoniensesBoase Modern English Biography, volume xComplete PeerageDictionary <strong>of</strong> American BiographyDictionnaire de Biographie FrançaiseDizionario Biografico degli ItalianiDictionnaire Historique et Biographique de la SuisseDictionary <strong>of</strong> Quaker Biography (typescript in Friends’House London and Haverford College Pennsylvania)Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Scientific BiographyEnciclopedia ItalianaEncyclopedia <strong>of</strong> the RenaissanceGrove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> ArtGrove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Music and MusiciansGeneral Register Office

xxHPLUINBUNDBNNBWNRAxODNBPODPxRI MMRNLSROVBMDWWWxHistory <strong>of</strong> ParliamentLessico Universale ItalianoNouvelle Biographie UniverselleNeue Deutsche BiographieNieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch WoordenboekNational Register <strong>of</strong> Archives, report number xOxford Dictionary <strong>of</strong> National BiographyPost Office Directory (see below)Poggendorff Biographisch-Literarisches Handwörterbuch,volume xGreenaway et al. (1971–6). This is followed by date <strong>of</strong> meeting,volume and page numberRévai Nagy LexikonaScottish Register OfficeVictoria Births, Deaths and MarriagesWho Was Who, volume xReports <strong>of</strong> lectures in the daily and weekly newspaper press and referencesto plays, poems and pieces <strong>of</strong> music are given only in the notes.From 1851 the Royal Institution published accounts <strong>of</strong> the Friday EveningDiscourses in its Proceedings. <strong>The</strong>se reports are listed in the bibliography andwhen cited in notes, indication is made that these were Discourses. Referencesto the Gentlemens’ Magazine and the Annual Register (which has novolume number after 1863) are likewise given only in the notes. <strong>The</strong> followingdirectories are cited in the notes:Crockford Clerical Directory (Crockford)Medical DirectoryNavy ListImperial CalendarPost Office Directory (POD)Royal KalendarCitations to these directories, unless otherwise indicated, refer to theedition <strong>of</strong> the year <strong>of</strong> the letter where the note occurs. <strong>The</strong>se directories universallymake the claim to contain up-to-date and complete information. Thiswas frequently far from the case and this explains apparent discrepancieswhich may occur.Faraday’s Diary. Being the various philosophical notes <strong>of</strong> experimental investigationmade by Michael Faraday, DCL, FRS, during the years 1820–1862 andbequeathed by him to the Royal Institution <strong>of</strong> Great Britain. Now, by order <strong>of</strong>the Managers, printed and published for the first time, under the editorial supervision<strong>of</strong> Thomas Martin, 7 volumes and index, London, 1932–6 is cited asFaraday, Diary, date <strong>of</strong> entry, volume number and paragraph numbers, unlessotherwise indicated.

xxiFaraday’s ‘Experimental Researches in Electricity’ are cited in the normalway to the bibliography, but in this case the reference is followed by‘ERE’ and the series and paragraph numbers, unless otherwise indicated.Two <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s papers (1852b, 1855a) were published in the PhilosophicalMagazine, as he regarded them as ‘<strong>of</strong> a speculative and hypothetical nature’(1852b, p.401), but in them he continued the paragraph numbering <strong>of</strong> his‘Experimental Researches’ published in the Philosophical Transactions. To helplocate references within these papers, I have allocated them the series numbers29a and 29b respectively and they are thus cited in the notes in squarebrackets.John Tyndall’s manuscript diary, in the Archives <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution(RI MS JT/2/1-12), is cited as Tyndall, Diary, followed by date and reference.<strong>The</strong> typescript <strong>of</strong> the diary <strong>of</strong> Thomas Archer Hirst, in the Archives <strong>of</strong>the Royal Institution (RI MS JT/2/32/a-e), is cited as Hirst, Diary, followedby date and reference.<strong>The</strong> diary <strong>of</strong> Herbert McLeod, published as James (1987), is cited asMcLeod Diary, followed by the date <strong>of</strong> entry.Manuscript abbreviations<strong>The</strong> following are used to cite manuscript sources where the primary abbreviationis used twice or more. (NB Reference to material in private possessionis always spelt out in full.) <strong>The</strong>se abbreviations are used in both the letterheadings and the notes:AC MSANLAPSAS MSAUL MSBI MSBLBMBod MSBPRE MSBPUG MSBRAI ARBCHFChULadd MSMS EgAthenaeum Club ManuscriptAccademia Nazionale dei LinceiAmerican Philosophical SocietyAcadémie des Sciences ManuscriptAberdeen University <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptBrunel Institute, SS Great Britain Trust, ManuscriptBritish <strong>Library</strong>additional ManuscriptEgerton ManuscriptBritish MuseumBodleian <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptBiblioteca Panizzi, Reggio EmiliaBibliothèque Publique et Universitaire de GenèveManuscriptBibliothèque royale Albert Ier, Académie royalede BelgiqueChemical Heritage FoundationChicago University <strong>Library</strong>

xxiiDUAEUL MSFACLMFM MSGCA MSHL HUHL UGHunt MSIC MS<strong>IET</strong> MSJRULMKCLLMALUNALNHMNLS MSNRCC ISTINULPMLRASARBGKRCSRGORHSRI MSDundee University ArchivesEdinburgh University <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptFrancis A. Countway <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> MedicineFitzwilliam Museum ManuscriptGlasgow City Archives ManuscriptHoughton <strong>Library</strong>, Harvard UniversityHargrett <strong>Library</strong>, University <strong>of</strong> GeorgiaHuntington <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptImperial College ManuscriptHPHuxley PapersInstitution <strong>of</strong> Engineering and Technology(formerly the Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers)ManuscriptSCSpecial Collection2 David James Blaikley Collection3 S.P. Thompson CollectionJohn Rylands University <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> ManchesterKing’s College, LondonLondon Metropolitan ArchivesLehigh UniversityNational Art <strong>Library</strong>Natural History MuseumNational <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> Scotland ManuscriptNational Research Council Canada Institute forScientific and Technology InformationNewcastle University <strong>Library</strong>Pierpont Morgan <strong>Library</strong>, New YorkRussian Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences ArchivesRoyal Botanic Gardens, KewRoyal College <strong>of</strong> SurgeonsRoyal Greenwich Observatory6 Airy papersRoyal Humane SocietyRoyal Institution ManuscriptF1Faraday lettersA, D, E, F, G Letters from FaradayH, I, K Faraday’s portrait albumsL, N Miscellaneous letters to and fromFaradayF2 Faraday’s experimental notebooksF4 Faraday’s notes <strong>of</strong> lecturesF5 Apparatus booksF Petty cash bookF8 Faraday’s copy <strong>of</strong> Davy’s biography

xxiiiRLSARS MSRSARSC MSSAL MSSISM MSSoROSPKSuROTNAGGBGMHDJTLeRI 4RI CGPapers <strong>of</strong> W.R. GroveGuard BookMinutes <strong>of</strong> General MeetingPapers <strong>of</strong> Humphry DavyPapers <strong>of</strong> John TyndallTS Typescript volumes/1 <strong>Correspondence</strong>/2 Tyndall’s diary/3 Tyndall’s notebooksLecture recordsMinutes <strong>of</strong> the Journal Committee<strong>Correspondence</strong>, GeneralRedbridge Local Studies and ArchivesRoyal Society Manuscript241 Faraday’s diploma book364 Glass Committee bookBaCertCMCMB 71CMB 90dHSMCMMD MSDDBJ7HO73HO107MTPRO30Barrett PapersCertificate <strong>of</strong> Fellow electedCouncil Minutes (printed)Glass Committee bookMinutes <strong>of</strong> Committee <strong>of</strong> PapersHerschel papersMiscellaneous <strong>Correspondence</strong>Miscellaneous ManuscriptsRoyal Society <strong>of</strong> ArtsRoyal Society <strong>of</strong> Chemistry ManuscriptSociety <strong>of</strong> Antiquaries <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptSmithsonian Institution <strong>Library</strong>Dibner CollectionScience Museum <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptSomerset Record OfficeStaatsbibliothek Preussischer KulturbesitzDokumentensammlung DarmstaedterF 1 e 1831(2). Autograph I/1478/23Surrey Record Office<strong>The</strong> National Archives, Kew(formerly the Public Record Office)Fitzroy papersRecords <strong>of</strong> the Royal Commission onPublic Schools1841 and 1851 CensusMarine Department <strong>of</strong> the Board <strong>of</strong>Trade recordsPapers deposited in <strong>The</strong> National Archives

xxivUB MSUKLULBULCUP VPLUTAWIHM MSWSLWTDCYULPROB11 Wills granted probate between 1384 and 1858RG4 and 5 Registers <strong>of</strong> dissenting churchesRG91861 CensusRG10 1871 CensusRG11 1881 CensusRG12 1891 CensusRG13 1901 CensusWO97 Records <strong>of</strong> the Royal Hospital ChelseaUniversität Basle ManuscriptNSNachlass SchoenbeinUniversity <strong>of</strong> Kentucky, LexingtonUniversity <strong>Library</strong>, BirminghamUniversity <strong>Library</strong>, CambridgeAdd MS 7655 Maxwell PapersAdd MS 7656 Stokes PapersUniversity <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania Van Pelt <strong>Library</strong>Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center,<strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Texas at AustinWellcome Institute for the History <strong>of</strong>Medicine ManuscriptWilliam Salt <strong>Library</strong>Wordsworth Trust, Dove CottageYale University <strong>Library</strong>

IntroductionThis volume includes 731 letters to and from Michael Faraday (and his immediatefamily) written between November 1860 and his death nearly sevenyears later on 25 August 1867, just under a month short <strong>of</strong> his seventy-sixthbirthday. It also contains 143 letters that have proved impossible to date and306 letters from the period covered in volumes one to five, but which had notbeen located when those volumes were published. In total 82.5% <strong>of</strong> the lettersin this volume are previously unpublished.Despite lacking information about dates, some <strong>of</strong> the undated lettersnevertheless do provide helpful insights into Faraday’s life and work. Forexample, in a letter to Hopwood, Faraday explicitly dealt with the importantissue <strong>of</strong> his opposition to the atomic theory 1 whilst in a letter to EdwardHawkins he intriguingly referred to the chemical treatment <strong>of</strong> the Lewis chesspieces purchased by the British Museum in the 1830s 2 . Moreover, many <strong>of</strong>the letters that relate to the period covered in earlier volumes are <strong>of</strong> greatinterest in casting additional light on the development <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s career.Most important, perhaps, is an 1836 letter to a friend from his youth, BenjaminAbbott which helps to identify many, but not all, <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s early circle <strong>of</strong>friends 3 as does an 1818 letter to John Huxtable 4 . A couple <strong>of</strong> letters writtenthe previous year to Thomas Winkworth 5 provide further information onFaraday’s activities in the 1810s. Other insights into his life during that decadeare contained in correspondence with Edward Daniel Clarke about the latter’spaper on his work with the blowpipe published in the Quarterly Journal <strong>of</strong>Science that Faraday edited while William Thomas Brande was away 6 .<strong>Correspondence</strong> from the 1820s sheds fresh light on Faraday’s role inestablishing the Athenaeum Club, where he served as its first secretary, andconfirms the enormous amount <strong>of</strong> work which this entailed 7 . Although hequickly passed this position onto his friend Edward Magrath, he continuedhis connection with the club, including an 1841 letter in which he gave hisopinion on the poor quality <strong>of</strong> leather for bookbinding compared to ‘formeryears’ 8 – presumably a very rare reference to his own apprenticeship. Other1820s letters deal with his practical work on the Millbank Penitentiary 9 , theoptical glass project 10 and various engineering projects connected with MarcBrunel and his son Isambard 11 .

xxvi<strong>The</strong>re are also letters that provide background to Faraday’s course <strong>of</strong>lectures on ‘Chemical Manipulation’ delivered during the first half <strong>of</strong> 1827 atthe London Institution 12 and which he turned into his only book conceived assuch 13 ; moreover, there is a letter about later editions and translations 14 . Thislecture course at the London Institution was unique and thereafter, due topressure <strong>of</strong> time, he lectured only at the Royal Institution and to the cadets atthe Royal Military Academy, Woolwich (which does not figure greatly here 15 ).Thus throughout the 1830s and beyond he declined invitations to lecture atplaces such as the Manchester Royal Institution 16 , the Belgrave Literary andScientific Institution 17 and elsewhere 18 . Faraday similarly did not accept aninvitation to contribute an article to the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana 19 .Several letters pertain to the evolution <strong>of</strong> Friday Evening Discoursesat the Royal Institution, including one to Marc Brunel written very shortlyafter their establishment in which Faraday described them as ‘a sort <strong>of</strong> sociallecture’ 20 . However, most <strong>of</strong> these letters dealt with mundane administrativematters relating to the Discourses, including the exhibitions in thelibrary 21 .Although by the end <strong>of</strong> the 1820s Faraday had ceased his involvementwith the project for improving optical glass 22 , his time was, nevertheless,fully occupied and he continued, for instance, to undertake routine chemicalanalyses, until the mid-1830s 23 . His financial situation improved followinghis appointment as the first Fullerian Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Chemistry at the RoyalInstitution in 1833 24 and as scientific adviser to Trinity House, the English andWelsh lighthouse authority, in 1836. He was thus able to cease undertakingpaid pr<strong>of</strong>essional miscellaneous chemical analyses, although he would lateroccasionally undertake this kind <strong>of</strong> work for public benefit 25 or for friends 26 ,but not for payment.<strong>The</strong> 1830s was, above all, a decade <strong>of</strong> remarkable productivity in his scientificresearch, starting with his discovery <strong>of</strong> electro-magnetic induction on29 August 1831. Indeed, so committed was he to pursuing his programme <strong>of</strong>research that in 1836 he instructed the porters at the Royal Institution that hewould see no one on Tuesday, Thursday or Saturday or after four in the afternoonon other days <strong>of</strong> the week, a rule which could on occasion be a source <strong>of</strong>embarrassment 27 . Following a period in the early 1840s when he reflectedon how best to achieve his research aims, he recommenced an extendedperiod <strong>of</strong> experimentation and theorising following his discovery in 1845<strong>of</strong> the magneto-optical effect and diamagnetism, phenomena that Faradaydemonstrated to the Council <strong>of</strong> the Royal Society 28 and also to friends andcolleagues in the Royal Institution 29 .By 1860, with his fundamental scientific discoveries, his enormousattractiveness and popularity as a lecturer and his work for the state, Faradaywas widely acknowledged as one <strong>of</strong> the most famous men <strong>of</strong> the day,a reputation which continued to grow after his death and indeed downto the present 30 . During the 1860s his fame continued to be recognised

xxviiinstitutionally by, for example, the University <strong>of</strong> Cambridge conferring anhonorary doctorate on him on 9 June 1862 31 and shortly afterwards, at theinstigation <strong>of</strong> his old friend Carlo Matteucci, now Minister <strong>of</strong> Public Instruction<strong>of</strong> the newly unified Italy, King Victor Emanuel II conferred a Knighthood<strong>of</strong> St Maurice and Lazarus on Faraday 32 . In 1866 the Society <strong>of</strong> Arts awardedits Gold Albert Medal to him. By that time Faraday was too unwell to beable to attend an award ceremony at the Society and so a group <strong>of</strong> Councilmembers visited him on 16 June 1866 in order to make the presentation 33 .Faraday’s inability to attend the presentation is indicative <strong>of</strong> the predominanttone <strong>of</strong> his letters during the 1860s, with aging, his withdrawalfrom duties and ultimately with impending death. Yet he remained remarkablyactive for much <strong>of</strong> this period, lecturing and experimenting until 1862(albeit at a much diminished level), undertaking the duties <strong>of</strong> Elder <strong>of</strong> theLondon Sandemanian Church until 1864 and <strong>of</strong> Scientific Adviser on lighthousesto Trinity House and the Board <strong>of</strong> Trade, and continuing to work forthe Royal Institution which despite Faraday’s best efforts, retained him untilthe end.His decline in health and the shedding <strong>of</strong> his responsibilities are reflectedin the steady reduction <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> letters each year:1861 1831862 1661863 1371864 981865 551866 23 (<strong>of</strong> which only six were from Faraday)1867 10 (<strong>of</strong> which none were from Faraday)During these years around 270 letters (or 37% <strong>of</strong> the total) dealt with lighthousematters including correspondence with the Birmingham glassmaker,James Chance, the Deputy Master <strong>of</strong> Trinity House, William Pigott, and itsSecretary and Assistant Secretary, Peter Berthon and George Herbert and theAssistant Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Board <strong>of</strong> Trade, Thomas Farrer. At the Royal Institution,Faraday’s main correspondents remained Henry Bence Jones, JohnBarlow (and his wife Cecilia), Edward Frankland, John Tyndall and BenjaminVincent. Faraday continued corresponding with a number <strong>of</strong> figuresoutside these two areas, but <strong>of</strong> course some <strong>of</strong> these letters dealt with RoyalInstitution and lighthouse service matters. <strong>The</strong>se correspondents included:George Airy, Angela Burdett Coutts, Auguste De La Rive, Warren De LaRue, J.B.A. Dumas, William Snow Harris, John Herschel, Justus Liebig,Carlo Matteucci, James Clerk Maxwell, Harriet Moore, John Percy, JuliusPlücker, L.J.A. Quetelet, Henry Enfield Roscoe, Edward Sabine, ChristianSchoenbein, James South and William Thomson. But most <strong>of</strong> these exchangestailed <strong>of</strong>f rapidly in the 1860s due either to Faraday’s decline or that <strong>of</strong> thecorrespondent.

xxviiiDuring the 1860s and the six years following Faraday’s death many<strong>of</strong> his long-standing friends, colleagues and correspondents died includingEdward Magrath (1861), Benjamin Collins Brodie (1862), Samuel HunterChristie (1865), William Whewell (1866), William Thomas Brande (1866), hislong-term assistant Charles Anderson (1866), William Snow Harris (1867),James South (1867), Cecilia Barlow (1868), Julius Plücker (1868), ChristianSchoenbein (1868), Carlo Matteucci (1868), David Brewster (1868), John Barlow(1869), John Herschel (1871), Charles Babbage (1871), William VernonHarcourt (1871), Auguste De La Rive (1873), Justus Liebig (1873) and HenryBence Jones (1873).Two other deaths particularly affected Faraday. <strong>The</strong> first, which distressedthe entire nation, was the very unexpected demise <strong>of</strong> Prince Albert on14 December 1861 at the age <strong>of</strong> forty-two. Faraday had taken the lead in drawingthe Prince into the Royal Institution and the Prince had been instrumentalin securing for him the Grace and Favour House at Hampton Court whereFaraday lived for much <strong>of</strong> the 1860s 34 . Faraday immediately instructed thehousekeeper for the lower windows <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution to be closed as amark <strong>of</strong> respect ‘upon this sad death <strong>of</strong> our Prince’ 35 . Writing, on black-edgedpaper, at the beginning <strong>of</strong> 1862 to Ernst Becker, the Prince’s German secretary,Faraday commented ‘We remember him more as a man than a Prince.He exalted his rank far more than it exalted him’ 36 . Such expressions <strong>of</strong> sympathydoubtless lay behind Queen Victoria ensuring that Faraday was sent acopy <strong>of</strong> Albert’s Principal Speeches at the start <strong>of</strong> 1863 37 . <strong>The</strong> second death thatespecially affected Faraday was that <strong>of</strong> his younger sister Margaret Barnard,his last surviving sibling, and fellow member <strong>of</strong> the Sandemanian Church, on14 October 1862, just a month short <strong>of</strong> her sixtieth birthday 38 . Faraday, elevenyears older, had played a role in her upbringing, helped with her educationby teaching her to read and write 39 , and she was the mother <strong>of</strong> Faraday andSarah Faraday’s favourite joint niece, Jane Barnard, who had been living permanentlywith them since at least 1851. Faraday entered an unusually longperiod <strong>of</strong> mourning for his sister and used black-edged paper for his lettersuntil March 1863 40 .As in the previous volumes there are several letters which refer toFaraday’s roles in the Sandemanian Church, although their quantity doesnot adequately reflect the importance <strong>of</strong> the church in his life. On 21 October1860 he had been elected, for the second time, an Elder <strong>of</strong> the LondonChurch 41 . As a consequence, Faraday had some responsibility in overseeingthe move <strong>of</strong> the church from Paul’s Alley in September 1862, where it had beenlocated since 1785, to Barnsbury, a move regretted by Sarah 42 . As an Elder,Faraday <strong>of</strong>ficiated at the church, delivered exhortations, baptised infants andvisited other Sandemanian meeting houses. <strong>The</strong>se included Newcastle (inAugust 1861, which had just acquired a new building 43 , and the followingspring 44 ), Old Buckenham in Norfolk (August and September 1862 and againin 1864 45 ) and Glasgow and Dundee during the first half <strong>of</strong> August 1863 46 .

xxixIn Dundee on 9 August he preached the only exhortation <strong>of</strong> his that we havein its entirety 47 .As well as providing biblical references and advice for those about tomake their Confession <strong>of</strong> Faith 48 and general comments about the spiritualstate <strong>of</strong> the church 49 , Faraday also commented on the deaths <strong>of</strong> fellow Sandemaniansand members <strong>of</strong> the broader community associated with the church,many <strong>of</strong> whom were related in some way to him, including, <strong>of</strong> course, his sister.Jemima Hornblower and William Giles both died towards the end <strong>of</strong> 1861,Sarah Barker in 1865 whilst her husband Thomas (a Sandemanian Deacon)and Faraday’s sister-in-law, Charlotte Buchanan, both died the following year.<strong>The</strong> death <strong>of</strong> William Giles (a double cousin <strong>of</strong> the artist Samuel Palmer 50 )was <strong>of</strong> particular concern as this continued the tragedy <strong>of</strong> the Giles family 51 .His widow Ellen, a niece <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s, had been left with nine children, theyoungest under one. Faraday found work for the oldest, William BrantinghamGiles, in Frankland’s laboratory 52 and he subsequently made a career asan analytical chemist. William Giles’s brother, John (who was one <strong>of</strong> Palmer’smajor supporters), stepped in to assist other members <strong>of</strong> the family 53 .Faraday’s commitment to Sandemanianism informed his responses tothe discussions that were just beginning to take place during the 1860s onthe relationship between science and religion as well as his continuing irritationwith spiritualism. As noted at the end <strong>of</strong> the introduction to volumefive, Faraday was not present at the public discussion, held in Oxford on 30June 1860, between Samuel Wilberforce, Thomas Huxley and Joseph Hookerover the theological implications <strong>of</strong> the theory <strong>of</strong> organic evolution by naturalselection that Charles Darwin 54 had proposed. Although Faraday’s absencecan perhaps be seen as indicative that his scientific practice had become oldfashioned in approach and to some extent in content, nevertheless evolutiondoes not appear to have a been a major issue for him. And his onlyexplicit comment on the subject was that the evidence supporting evolutionwas ‘weak & feeble’ 55 , a view based as much on science as on his religiousbeliefs.During the early 1860s it was not Darwinism that brought the relation<strong>of</strong> science and religion into contention, but the various rows that rocked theAnglican church, especially the heresy trials stemming from the publication<strong>of</strong> Essays and Reviews in 1860 56 . Such events prompted a group <strong>of</strong> junior staffand students at the Royal College <strong>of</strong> Chemistry to write their ‘Declaration <strong>of</strong>the Students <strong>of</strong> the Natural and Physical Sciences’ which they circulated forsignature by members <strong>of</strong> the scientific community. <strong>The</strong> ‘Declaration’ arguedthat, in the final analysis, the word <strong>of</strong> God written in the Bible would notbe found to conflict with the word <strong>of</strong> God written in the natural world. Thisdocument provoked considerable controversy for a number <strong>of</strong> reasons, thecauses <strong>of</strong> which can, in the main, be attributed to the youthful inexperience<strong>of</strong> those who drafted and propagated the ‘Declaration’. For example, the factthat it was addressed to the Convocation <strong>of</strong> the Anglican Church prompted

xxxthe Irish mathematician and astronomer William Rowan Hamilton to referto it as a fortieth article <strong>of</strong> faith exclusively for scientific men. Moreover,some scientific figures, such as John Herschel, rejected the implied notionthat science encouraged infidelity. Hence many in the scientific community,including Faraday, who might have been expected to sign, declined, althoughDavid Brewster and more than 10% <strong>of</strong> the Fellowship <strong>of</strong> the Royal Societydid 57 .<strong>The</strong> initial strategy followed by the authors <strong>of</strong> the ‘Declaration’ was totry to secure the signature <strong>of</strong> prominent members <strong>of</strong> the scientific community,so as to encourage others to support it. Thus in mid-April 1864 the AssistantChemist at the College, Herbert McLeod (who frequently attended Discoursesat the Royal Institution), visited Faraday to invite him to sign: ‘He said thathe could not being a dissenter and as he did not think that the clergy <strong>of</strong> the[Anglican] church had any right to interfere in the matter. He said that ashe had once given his opinion on the matter in his lectures on education hedid not wish to take any more steps in the matter. He was very kind’ 58 .Hedeclined once more to sign the ‘Declaration’ when he was invited for a secondtime, this time by letter, and again he cited his 1854 lecture on education 59 , butadded ‘I am glad to see the names <strong>of</strong> so many who are to a certain degree likeminded’ 60 ; he had given a similar response the previous year to an enquiryfrom the Swiss theologian Jules Naville 61 .What did continue, however, to be a major issue for Faraday was spiritualism.In 1861 the Scottish-born American medium Daniel Home attractedfashionable audiences in London. <strong>The</strong>se included James Emerson Tennentwho, as Secretary to the Board <strong>of</strong> Trade, Faraday knew quite well, and heinvited Faraday to attend one <strong>of</strong> Home’s séances. Usually when Faradayreceived such invitations, his reply was quite brusque as exemplified by hisresponses to Thomas Sherratt and the brothers Davenport 62 . But with Tennent,Faraday was much more polite and asked a series <strong>of</strong> searching questions.<strong>The</strong> séance did not however take place, which Tennent, possibly tactfully,attributed to the illness <strong>of</strong> Home’s wife 63 . Faraday was also restrained inhis criticisms <strong>of</strong> spiritualism when writing to Robert Cooper, the son <strong>of</strong> hisold friend, the chemist John Thomas Cooper 64 . Nevertheless, despite beingmore moderate in tone with those whom he knew, Faraday remained implacablyopposed to spiritualism and his feelings were perhaps most trenchantlyexpressed at the end <strong>of</strong> the letter declining the invitation to the Davenports’séance: ‘If Spirit communications not utterly worthless should happen to startinto activity I will leave the Spirits to find out for themselves how they canmove my attention. I am tired <strong>of</strong> them’ 65 .This feeling <strong>of</strong> weariness was not restricted just to spiritualism, but waspart <strong>of</strong> the more general tone <strong>of</strong> decline which was reflected in all <strong>of</strong> Faraday’sactivities during these years and can be seen in the complex relationship whichdeveloped between him and the Royal Institution. This change was contingentnot only on Faraday’s declining powers but also on the Royal Institution

xxxias it altered direction and Faraday sought to disengage himself from hisemployers, though with the fiftieth anniversary <strong>of</strong> his first appointment therefalling in 1863, this was emotionally difficult for both sides 66 .His appointment as a Sandemanian Elder in October 1860 entailed additionalwork and this may help explain why he and Sarah did not wish him todeliver the Royal Institution’s Christmas Lectures <strong>of</strong> 1860–1861. Because <strong>of</strong>his poor health, he had twice postponed the opening lecture <strong>of</strong> the previousseries 67 . But, as Sarah wrote to a nephew in mid-November 1860, because, forreasons <strong>of</strong> ill health, Barlow had resigned the Secretaryship <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution,‘it was thought not good for your Uncle to give up any thing he couldkeep at the same time’ 68 . Presumably because he had not been expecting todeliver this series, Faraday, like all good lecturers, recycled his material fromearlier Christmas Lectures. At the start <strong>of</strong> his notebook for this series are thelecture cards from his Christmas Lectures <strong>of</strong> 1848–1849 and 1854–1855 as wellas the 1860–1861 series 69 . He gave permission for William Crookes to publishthe lectures first in the weekly Chemical News, which Crookes edited, and thenasabook–arepeat <strong>of</strong> the process that Crookes had undertaken for Faraday’s1859–1860 series on <strong>The</strong> Various Forces <strong>of</strong> Matter 70 . Thus was published <strong>The</strong>Chemical History <strong>of</strong> a Candle 71 , which is, arguably, the most popular sciencebook ever published; it has never subsequently been out <strong>of</strong> print in Englishand thus far has been translated into at least fifteen languages 72 .However, this was his final series <strong>of</strong> Christmas Lectures and to prevent arecurrence <strong>of</strong> the circumstances for the 1861–1862 series, Faraday, shortly afterturning seventy, wrote an explicit letter to the Managers resigning them 73 .Atthe same time he also took the opportunity to <strong>of</strong>fer his resignation from allhis roles at the Royal Institution, but left that for the Managers to decidethe outcome. Bence Jones, the new Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution, seemsto have raised an issue relating to Faraday’s <strong>of</strong>fer which caused him someanxiety 74 . Quite what this was is not known, but it would not be the last timethan Bence Jones would create difficulties for Faraday. Indeed Tyndall in adiary entry written around the time <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s death commented ‘BenceJones is a man <strong>of</strong> warm affections; but they are strangely easily deflectedand converted into something very different from affection – <strong>The</strong>y were soin the case <strong>of</strong> Faraday’ 75 . Whatever the problem, the Managers, nevertheless,accepted Faraday’s decision on the lectures but hoped that he would retainhis other roles 76 which he did. Tyndall immediately grasped the opportunityto take on the Christmas Lectures (although for the remainder <strong>of</strong> Faraday’slife he alternated with Frankland in their delivery). But, like the Managers,Tyndall was also concerned to retain Faraday’s close connection with theRoyal Institution and threatened his own resignation, especially if Faradayresigned in order to facilitate his promotion 77 .In this period Faraday played only a minor role in Friday Evening Discourses.When he ceased attending them is not clear and he continued to bean active participant until at least 6 May 1864 when he was photographed

xxxiiusing flash light 78 . As well as stepping down from the Christmas lectures, hewas also thinking <strong>of</strong> giving up delivering Discourses. At ‘On Platinum’ (22February 1861) he talked about retiring but ‘was very much cheered’ 79 , whichsuggests that he may well have intended this to be his last appearance at theRoyal Institution’s lecture bench. But because he failed to persuade either Airyor De La Rue to deliver a Discourse on the important subject <strong>of</strong> the total solareclipse that was visible from Spain on 18 July 1860 80 , in the end he deliveredit himself on 3 May 1861 81 using material provided by De La Rue 82 . His finalDiscourse, seems to come about following a pressing invitation from BenceJones 83 . For his final performance in the theatre <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution on 20June 1862 84 , Faraday lectured on the gas furnace invented by Carl Siemenswhich he had seen working at Chance’s glass factory in Birmingham 85 .Since Faraday had not been able to retire from his administrative rolesat the Royal Institution, various high-level tasks continued to fall to him. <strong>The</strong>death <strong>of</strong> the Prince Consort meant that there was a vacancy for the role <strong>of</strong>Vice-Patron <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution, the obvious candidate being the Prince<strong>of</strong> Wales. Faraday sounded out Becker as to the feasibility <strong>of</strong> this idea in July1862, but the matter was not raised again until December, presumably because<strong>of</strong> the need to observe a full period <strong>of</strong> mourning before anything should beproposed <strong>of</strong>ficially 86 . In December the Managers deputed Faraday to raisethe matter again with Becker 87 who tried to see Faraday but he was then atBrighton. When they did finally meet, on 19 December, Faraday noted that ‘Heencouraged me’ 88 . Faraday then tried to pass the task <strong>of</strong> making the formalapproach to the President, the Duke <strong>of</strong> Northumberland, who declined onthe grounds that he would be at Alnwick for some weeks. He suggested thatFaraday do it himself 89 which he did on 5 January 1863 90 . <strong>The</strong> Comptroller<strong>of</strong> the Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales’s household, William Knollys, replied on behalf <strong>of</strong> thePrince accepting the proposal, adding that it would give the Prince pleasureto ‘meet you again where he has listened to you before and derived so muchinstruction from your lectures’ 91 .That the Royal Institution was trying to retain the same personal linkwith the Royal Family that it had forged through Prince Albert is clear fromthe first visit <strong>of</strong> the Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales as Vice-Patron. At midday on 21 May 1863,the Prince, together with the Princess <strong>of</strong> Wales 92 , the Prince and Princess Louis<strong>of</strong> Hesse 93 and members <strong>of</strong> their household, came to the Royal Institution 94to hear Tyndall lecture on spectrum analysis and to sign the Register <strong>of</strong> Members.Faraday commented that ‘It will be a meeting like that first one we hadwith the Prince Consort’ 95 . This seems to have been a case <strong>of</strong> Faraday’s memoryletting him down since Tyndall’s lecture was a private one for the Prince<strong>of</strong> Wales and his party, not a Discourse, albeit special, for Members <strong>of</strong> theRoyal Institution which Prince Albert had attended in February 1849 96 . Nevertheless,Faraday couching the visit <strong>of</strong> the Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales in terms <strong>of</strong> PrinceAlbert’s first visit seems to be an attempt to retain the link with the past. <strong>The</strong>Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales, though not as active as his father in the Royal Institution

xxxiiior indeed as interested in science, nevertheless undertook a limited number<strong>of</strong> duties and wrote a kind letter <strong>of</strong> condolence to Sarah after Faraday’sdeath 97 .<strong>The</strong> striking element in all this was the crucial role that Faraday playedwhich suggests that the President and Managers had come to regard himas the leading, if not the dominant, figure at the Royal Institution, despitebeing an employee. Faraday even used his influence and the fact that he hadremained as Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, as Director <strong>of</strong> the Laboratory and as Superintendent<strong>of</strong> the House to dissuade successfully, for the second time 98 , the Duke <strong>of</strong>Northumberland from resigning as President 99 , an <strong>of</strong>fice he had held since1842. By May 1864, however, it was clear that the Duke’s health was declining(he died on 12 February the following year) and this prompted Bence Jones tothink <strong>of</strong> Faraday as his successor, an idea that appalled Faraday. Bence Jonesfirst seems to have proposed this to Faraday at the Friday Evening Discourseon 27 May 1864. Writing to Bence Jones the following Tuesday, Sarah, clearlydistressed, described vividly the anxious mental state into which Faradayhad been thrown by the proposal; indeed they had calculated how they couldlive without his income from the Royal Institution (around £450 annually orjust under half his total earnings) ‘if we had to leave’ 100 . Such was Faraday’sanxiety and Sarah’s concern that she wrote to the other Elders <strong>of</strong> the LondonSandemanian Church asking for something to be done to relieve Faraday’s‘over anxious mind from pressure’ 101 . <strong>The</strong> outcome was that Faraday laiddown his Elder’s <strong>of</strong>fice on Sunday 5 June 1864 102 . Although both Sarah andJane Barnard would have had ‘great gratification … to have seen him in thePresident’s chair’ 103 , it was, as they knew, ‘quite inconsistent with all my[Faraday’s] life & views’ 104 . A number <strong>of</strong> issues were in play here: Faraday’sreluctance to take <strong>of</strong>fices with significant power because <strong>of</strong> their corruptingnature, best illustrated by his declining the Presidency <strong>of</strong> the Royal Societytwice 105 ; second his belief that he was a servant <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution andcould never be its master 106 ; and finally he no longer had the energy to continueto undertake his current duties, let alone take on new ones. This wouldalso account for his decision to resign the <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> Elder in the SandemanianChurch at the same time.In the following months he sought to disengage himself from otheractivities, having already resigned from the not very onerous task <strong>of</strong> being amember <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> London Senate in April 1863 107 . In particular heturned his attention to his lighthouse duties, but encountered the same kind<strong>of</strong> problems as he had at the Royal Institution since both Trinity House andthe Board <strong>of</strong> Trade wished to retain their association with one <strong>of</strong> the mostfamous figures <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century for as long as possible.In 1836 Faraday had been appointed ‘Scientific adviser in experimentson Lights to the Corporation [<strong>of</strong> Trinity House]’ 108 . During the ensuing yearshe had undertaken an enormous quantity <strong>of</strong> work for them as evinced bythe letters published in volumes three to five and also by letters from the

xxxiv1830s and 1840 published in this volume relating to his first researches onphotometry, lamps and the quality control <strong>of</strong> lighthouse optics 109 .<strong>The</strong> first half <strong>of</strong> the 1860s was no different and much <strong>of</strong> the work Faradayundertook was a continuation <strong>of</strong> his lighthouse work <strong>of</strong> the 1850s. For exampleTrinity House asked for further advice on the limelight that had beendeveloped by William Fitzmaurice. Faraday was irritated with this workbecause he had to go over ground that he had previously covered 110 , butafter much effort he eventually advised that there was no need for TrinityHouse to undertake a final testing <strong>of</strong> Fitzmaurice’s system in a lighthouse,which they accepted 111 . On the other hand the limelight proposed by WilliamProsser was tested at the South Foreland lighthouse which Faraday visited. Inhis long report on the lamp 112 Faraday suggested that it should be observedfrom the sea – advice that Trinity House, once again, followed 113 .So far as electric light was concerned, where Faraday had been instrumentalin its installation and testing at South Foreland from late 1858 untilearly 1860 114 , it was installed in Dungeness lighthouse in early 1862 whichFaraday inspected on 12 and 13 February. On this visit he sailed out as faras the Varne lightship to make his observations. His subsequent report washighly complimentary: ‘when the Electric Light was restored, the glory roseto its first high condition’ 115 . Trinity House decided to retain the electric lightat Dungeness, but only there, and only to operate it if suitably qualified andtrained staff could be appointed. This, including the employment <strong>of</strong> a dedicatedengineer at an annual salary <strong>of</strong> £180 116 , had been done by May, andFaraday again visited Dungeness, examined the new keepers, and concludedthat everything was now ready ‘to establish the fitness or the contrary <strong>of</strong> Magnetoelectric light for lighthouse purposes’ 117 . Although it is not clear whenelectric light ceased to be used at Dungeness, its evident success during thefirst half <strong>of</strong> the 1860s prompted other inventors and manufacturers in bothBritain and France to propose other types <strong>of</strong> electric light, many <strong>of</strong> whichFaraday assessed for Trinity House 118 . This included discussing with LucyHoward de Walden the electrification <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the lighthouses at PortlandBill 119 .<strong>The</strong>re were, however, some novel aspects to Faraday’s work for TrinityHouse. For example he visited Birmingham several times to help the glassmakingbusiness <strong>of</strong> Chance Brothers develop a capability for manufacturinglighthouse quality glass and optical systems 120 and he struck up a close workingfriendship with James Chance. <strong>The</strong> other major addition to his lighthousework was on fog signals. <strong>The</strong> key figures here were the American inventorCeladon Daboll and the Irish astronomer Thomas Romney Robinson.<strong>The</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> fog horns became pressing during 1863 following the sinkingon 27 April <strong>of</strong> the SS Anglo Saxon <strong>of</strong>f Cape Race (on the south-east coast<strong>of</strong> Newfoundland) with the loss <strong>of</strong> nearly 250 lives. <strong>The</strong> lighthouse therehad been built in 1856, without a fog signal, by the Board <strong>of</strong> Trade, whowere responsible for colonial lighthouses. <strong>The</strong> Associated Press (an American