ENSA Y OS ENSA Y OS - Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

ENSA Y OS ENSA Y OS - Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

ENSA Y OS ENSA Y OS - Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

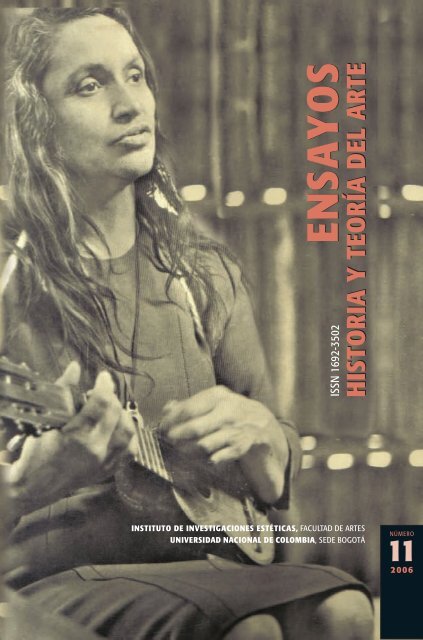

<strong>ENSA</strong>Y<strong>OS</strong>ISSN 1692-3502HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTEINSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES ESTÉTICAS, FACULTAD DE ARTESUNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE COLOMBIA, SEDE BOGOTÁNÚMERO112006

ContenidoEnsayos.Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteNúmero 11, 2006 ISSN 1692-3502ARQUITECTURA7ARTE25536789CINE111MÚSICA133145173187ArtículosFormación integral en Arquitectura:una propuesta <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el patrimonioJorge CaballeroLocalismo y señalamientosen el arte cubano <strong>de</strong> los noventaMiladys ÁlvarezLa imagen <strong>de</strong>l cuerpo fragmentadoSonia Castillo BallénLas exposiciones artísticas e industrialesy las exposiciones nacionales como antece<strong>de</strong>ntes<strong>de</strong>l Salón Nacional <strong>de</strong> ArtistasJuan Ricardo Rey-MárquezHistoria <strong>de</strong> los historiadores, gramáticasurrealista y tiempo transhistórico. Una reflexiónsobre la obra <strong>de</strong> José Alejandro RestrepoSantiago RuedaEl género documental en Colombia. Los cambios ynuevos retos que surgen a partir <strong>de</strong> la década <strong>de</strong>l90 (Primera parte)Carolina PatiñoTimba y tumbao, juntos y/pero no revueltos:estrategias <strong>de</strong> producción musical y gestualida<strong>de</strong>n la actual música popular bailable cubana.Daymí Alegría AlujasAnalysis and Proposed Organizationof the Capoeira Song RepertoireJuan Diego Díaz MenesesMigración amorosa y musical en “Run Run se fuepa’l norte” <strong>de</strong> Violeta ParraJuan Pablo GonzálezReseñasSeñalamientos sobre el arte colombiano. 40 SalónNacional <strong>de</strong> Artistas: “Un lugar en el mundo”.Marta Rodríguez

Juan Diego Díaz Menesesjuanobarano@yahoo.caDíaz meneses, Juan diego. Analysis and ProposedOrganization of the Capoeira Song Repertoire.Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arte, núm. 11, BogotáD. C., Universidad Nacional <strong>de</strong> Colombia, 2006,11 ejemplos musicales, pp. 145-170.ResumenEn este artículo se asume que los contenidos <strong>de</strong> los cantos<strong>de</strong> Capoeira son una fuente confiable <strong>de</strong> informaciónsobre los aspectos más importantes <strong>de</strong> este arte: música,ritual, juego, historia, filosofía y la idiosincrasia <strong>de</strong> suspracticantes. Este artículo explora el universo musical<strong>de</strong> Capoeira a través <strong>de</strong> un análisis sistemático <strong>de</strong> lasletras <strong>de</strong> un grupo seleccionado <strong>de</strong> cantos <strong>de</strong> Capoeira,para los cuales se proponen dos clasificaciones cuyoscriterios son analizados. A<strong>de</strong>más, serán estudiados ciertoselementos estéticos <strong>de</strong> su música para complementardicho análisis.Palabras ClaveJuan Diego Díaz Meneses, Cantos <strong>de</strong> Capoeira, Etnomusicología,Música Afrobrasileña.TítuloAnálisis y propuesta para la organización <strong>de</strong>l repertorio <strong>de</strong>canciones <strong>de</strong> CapoeiraAbstractIn this paper, the lyrics of Capoeira songs are used as areliable source of information about the most importantaspects of this art-form: music, ritual, play, history, philosophyand the idiosyncrasy of its practitioners. Thispaper elucidates the musical universe of Capoeira througha systematic analysis of the lyrics of a selected group ofsongs. The songs are classified using two criteria andboth criteria are analyzed. Furthermore, certain aestheticelements of the music are studied to complement thediscussion of the lyrics.Afiliación institucionalGoldsmiths College Of LondonLondresIngeniero Civil <strong>de</strong> la Universidad Nacional<strong>de</strong> Colombia (1998). Ha practicadoCapoeira continuamente <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> 1998 envarios países, incluyendo el Brasil. Allítomo clases con Mestres Cobra Mansa,Valmir y Moraes. Estudió canto lírico conel profesor cubano Alberto San José ya<strong>de</strong>más participó como tenor coral enel Coro Sinfónico Nacional <strong>de</strong> Costa Ricaen 2001. Des<strong>de</strong> 2001 se ha <strong>de</strong>dicadoa investigar y escribir sobre temasrelacionados con la etnomusicología.En 2005 trabajó como voluntario en elGrupo <strong>de</strong> Investigación Valores MusicalesRegionales <strong>de</strong> la Universidad <strong>de</strong> Antioquia(Me<strong>de</strong>llín), bajo la orientación <strong>de</strong> MaríaEugenia Londoño Fernán<strong>de</strong>z. Actualmentea<strong>de</strong>lanta estudios <strong>de</strong> maestría enetnomusicología en Goldsmiths Collegeen Londres.Key wordsJuan Diego Díaz Meneses, Capoeira songs, Ethnomusicology,Afro-Brazilian Music.Recibido Agosto 16 <strong>de</strong> 2006Aceptado Octubre 20 <strong>de</strong> 2006

ARTÍCUL<strong>OS</strong>MÚSICAAnalysis and Proposed Organization ofthe Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz MenesesEtnomusicólogoIntroduction*Capoeira was born within the constructs of Afro-Brazilian culture and has been anexpression of resistance of the Afro-Brazilian people in Brazil since at least the beginningof the Nineteen Century 1 . Today, swept up by globalization, it is no won<strong>de</strong>r that Capoeirahas become a new symbol of resistance, not only in Brazil but also in the countries whereit has arrived after its first official exit from Brazil in the early 1950s 2 . Its spread throughthe rest of the world has been more noticeable in urban settings where it arrived, primarily,with Brazilian practitioners who went abroad. The media has subsequently played a role*This article is based in a larger work in Spanish by the author named “Una Propuesta <strong>de</strong>Clasificación <strong>de</strong>l Cancionero <strong>de</strong> Capoeira”, unpublished.1Carlos Eugenio Libano Soares. A Capoeira Escrava e Outras Tradições Rebel<strong>de</strong>s no Rio<strong>de</strong> Janeiro (1808-1850). Campinas, São Paulo, Editora da Unicamp, 2001, p. 25. Libano Soarescoined the term Capoeira escrava (enslaved Capoeira) for the practice of Capoeira at the beginningof the 19 th century in the streets of Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro not only by enslaved Afro-<strong>de</strong>scendants,but also by free black men, poor white men, immigrants from other regions of the country andfrom places all around the world (specially sailors).2Bira Almeida (Mestre Acor<strong>de</strong>ón). Capoeira, A Brazilian Art Form. History, Philosophy andPractice. Berkley, California (USA), North Atlantic Books, 1986, p. 56. Mestre Acor<strong>de</strong>on assertsthat Capoeira left Brazil via cultural shows in the 1950´s. One of these first shows was calledSkindo, which featured capoeirists Arthur Emidio and Djalma Ban<strong>de</strong>ira. Later, in 1975 JelonVieira (a stu<strong>de</strong>nt of Bimba’s) pioneered the teaching of Capoeira overseas in USA.[145]

in introducing Capoeira into new settings. Interestingly, around the world Capoeira practitionershave found in Capoeira a new path of resistance in the face of the rapid changesimposed by globalization and capitalism.With Capoeira being practiced around the world many non-Brazilian nowadays singCapoeira songs (a short search in the web allows one to see that Capoeira is now practicedin countries on all continents). In most of the rodas 3 I have observed, the practitioners singthe ladainhas and corridos 4 in any situation, regardless of what is happening at that particularmoment. A <strong>de</strong>eper un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of Capoeira songs would allow practitioners to usethe songs in specific settings according to the lyrics. The fact that non-Brazilian Capoeirapractitioners do not heed the lyrics of the songs they sing, combined with their general lackof knowledge of Afro-Brazilian culture, <strong>de</strong>monstrate that these practitioners un<strong>de</strong>restimatethe power of Capoeira songs. These songs, when used properly, have great influence on theCapoeira roda and furthermore are a vehicle for un<strong>de</strong>rstanding the history of Capoeira andimportant elements of Afro-Brazilian culture.It is remarkable the importance that Mestre Moraes (a well-known traditional Capoeiramestre) gives to Capoeira music 5 :“The importance of music in the jogo 6 of Capoeira is immeasurable. It creates an atmospherein which its physical expression reaches the highest level of beauty. The music inspires the playersto reach more intensive levels of interaction and calm down the energy of the jogo if it is veryexalted. Through music the lea<strong>de</strong>r of the bateria 7 can not only intervene in or<strong>de</strong>r to mediatethe behavior of the players but can also prevent a haphazard moment. Moreover, he [or she]can provi<strong>de</strong> more energy to enhance the players’ performance. Sometimes the mediation of themusic is explicit: the singers can criticize, joke, praise or challenge the players. The permanentlink between music and the movement of the players creates and maintains the Capoeira roda.”(Translation from Portuguese by the author).A scrutiny of the lyrics of Capoeira songs permits us to see a universe in which themestres (Capoeira masters, or the individuals recognized by the Capoeira community as themost distinguished teachers) are kings of unquestionable power and an infinite source of3Roda is the Portuguese word for the formal Capoeira ritual. A further explanation is givenfarther on in the text.4Ladainhas and corridos are types of songs within the Capoeira repertoire. A further explanationis given farther on in the text.5Mestre Moraes and Grupo De Capoeira Angola Pelourinho (GCAP). Capoeira Angola FromSalvador, Brazil [CD liner notes]. Salvador <strong>de</strong> Bahia, Brazil, 1996.6Jogo is a Portuguese word for the physical aspect of the Capoeira ritual. It means “game” or“play” and it is a more inclusive word than “fight” or “dance” because both may occur withinthe jogo.7Bateria is the Portuguese term for a percussion section or ensemble. In this context it refers to thegroup of percussion instruments used in the Capoeira ritual (there are no melodic instruments).[146] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11

wisdom. Inasmuch, Capoeira music is a perfect place to start a profound exploration of thiscomplex art form.This paper is based on a thematic songbook written by me, in Spanish, containing acompilation of some six hundred Capoeira songs and further, a proposed division of thesongs, based on an analysis of the lyrics and some aesthetic elements 8 . The songs were takenfrom the repertoire used by Capoeira groups in Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Mexicoand the USA as well as from vi<strong>de</strong>os, CD and tape recordings, songbooks and websites, allcollected between 2000 and 2005.In this paper I will discuss my proposed division of the Capoeira song repertoire andanalyze certain aesthetic elements in or<strong>de</strong>r to contribute to a better un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of theCapoeira universe through its music. 9 First of all, I will refer to some historical and musicalelements which will enhance the rea<strong>de</strong>r’s un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of the phenomenon of Capoeira andthe i<strong>de</strong>as proposed here. Second, I will present my proposed division of the Capoeira songrepertoire and explain the criteria for that division with some examples. Third, an analysisof some aesthetic elements of several typical Capoeira songs (corridos) will be un<strong>de</strong>rtakento support or refute the lyrics-based division. Finally, some conclusions will be drawn.Background InformationHistorical Overview of CapoeiraA little history of Capoeira, with a specific focus on events in the 20 th century, will begiven in or<strong>de</strong>r to allow for a better un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of the processes that led to the <strong>de</strong>velopmentof the two main traditions in Capoeira (Capoeira Angola and Capoeira Regional).Although Capoeira is an old art-form no doubt related to the Afro-Brazilian people, itis not clear when Capoeira began to be practiced. Most practitioners claim that Capoeirahas been practiced in Brazil since the arrival of enslaved people from Africa 10 . However,Cavalcanti claims to have found the earliest document that proves the existence of Capoeira8The name of the original work is Una Propuesta <strong>de</strong> División <strong>de</strong>l Cancionero <strong>de</strong> Capoeira (unpublished).9As the musical universe of Capoeira is extensive and I am a Capoeira Angola practitioner, inthis paper the analysis of the aesthetic elements is focused on what I call “traditional songs”.However, some examples of “contemporary songs” will be used to contrast or reinforce the analysisof aesthetic elements of traditional songs in or<strong>de</strong>r to draw general conclusions.10Most Capoeira mestres and authors claim that this art-form has been practiced since thebeginning of the slavery in Brazil (1538). Bira Almeida (1986:15) cites Augusto Ferreira, whoromantically relates Capoeira with the quilombos in the Seventeen century. However, otherimportant researchers like Fre<strong>de</strong>rico Abreu (personal interview, Salvador, April 2006) and Almeidahimself (1986:20), assert that, <strong>de</strong>spite the fact that throughout history Capoeira has beenundoubtedly related to Afro-<strong>de</strong>scendant culture, fights and disor<strong>de</strong>r, there is no documentaryevi<strong>de</strong>nce of the presence of Capoeira in Brazil before the Eighteenth Century.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[147]

(dated in 1789) 11 . Since then, evi<strong>de</strong>nce of Capoeira practice has been found in police recordsalways relating to urban disor<strong>de</strong>rs, gangs, and even street-based political parties in Rio <strong>de</strong>Janeiro 12 . Nevertheless, the fact that Capoeira is an oral tradition allows us to suppose thatbefore the end of the 18 th century, it was practiced mostly as a martial art in rural contexts,probably as a form of resistance against slavery as imposed by the Portuguese colonizers 13 . Atthe beginning of the 19 th century, it appeared in urban contexts and thus began to radicallychange its aesthetic.The practice of Capoeira was banned in Brazil for many years until Mestre Bimba (awell-known figure) opened the first Capoeira aca<strong>de</strong>my in 1932, called Centro De LutaRegional Baiana 14 . Bimba was careful to change certain aspects of Capoeira, such as attire,movements and methods of instruction. He inclu<strong>de</strong>d stu<strong>de</strong>nts from the upper-middle classand called this type of Capoeira, Capoeira Regional. Various other mestres found these changesunacceptable and opened their own aca<strong>de</strong>my, in or<strong>de</strong>r to preserve what they consi<strong>de</strong>red tobe “traditional” Capoeira. The mestre of this aca<strong>de</strong>my, which opened in 1941, was MestrePastinha. Pastinha’s group <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to call their style Capoeira Angola in recognition of theAfrican roots of Capoeira and of the region in Africa that gave the most slaves to Brazil 15 .Both Bimba and Pastinha became, respectively, the fathers of Capoeira Regional and CapoeiraAngola. From this point onwards, Capoeira was split into these two main streams.The Capoeira Regional 16 style became more popular in Brazil (and in the other countriesinto which it has been introduced by Brazilians or local practitioners), whereas the Capoeira11Nireu Calvalcanti. Cronicas do Rio Colonial. O Capoeira. Journal do Brasil. Ca<strong>de</strong>rno B-1ªEdição, Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, 1999, p. 22. He <strong>de</strong>scribes a story of a slave who fled from his master’shouse to fight using Capoeira and who was subsequently punished by the police because thepractice of Capoeira was outlawed. It is not possible to establish from the account if Capoeirawas played in an urban or rural context.12Carlos Eugenio Libano Soares. A Capoeira Escrava e Outras Tradições Rebel<strong>de</strong>s no Rio<strong>de</strong> Janeiro (1808-1850). Campinas, São Paulo, Editora da Unicamp, 2001, p. 23, 229, 412.13John Fredy Zapata. Desarrollo Histórico <strong>de</strong> la Trova Antioqueña. Me<strong>de</strong>llin, unpublished thesis,Universidad <strong>de</strong> Antioquia, 2005, p. 75. According to Zapata, oral poetry is the only means ofcommunication available for farmers, fishermen, miners and illiterate people from the countrysi<strong>de</strong>.Thus, oral traditions (like Capoeira itself) are almost always related to rural contexts.14Bira Almeida (Mestre Acor<strong>de</strong>ón). Capoeira, a Brazilian Art Form. History, Philosophy andPractice. Berkley, California (USA), North Atlantic Books, 1986, p. 32. In 1937 Bimba´s aca<strong>de</strong>mywould receive official recognition by the Brazilian Government.15Eduardo Fonseca Jr. Dicionário Antológico Da Cultura Afro-Brasileira (Portugués, Yorubá,Nagô, Gege, Angola), Incluindo As Ervas Dos Orixás, Doenças, Usos E Fitologia Das Ervas. SãoPaulo, Yorubana do Brasil, Socieda<strong>de</strong> Editora Didática Cultural Ltda, 1995, p. 35.16In this case, the term Regional refers to both Bimba’s Capoeira Regional and other hybrid stylesof Capoeira different than the two main styles. Farther along in the text an exact distinctionwill be ma<strong>de</strong>.[148] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11

Angola style maintained a low profile 17 . I have witnessed tensions between the practitionersof these two styles in most of the countries to which I have traveled (Colombia, CostaRica, Nicaragua, Mexico and United States). Such disputes are groun<strong>de</strong>d in a struggle forpower and a <strong>de</strong>sire for one style to dominate the other. These practitioners hold the i<strong>de</strong>athat their respective style represents the “authentic tradition”. Clearly, behind this is whatOchoa calls a permanent fight for the re<strong>de</strong>finition of social processes and the i<strong>de</strong>ologiesassociated with them 18 .The Capoeira Roda and the Role of MusicThe principal expression of the Capoeira game is a ritual called the roda, which means“ring” or “circle” in Portuguese. In the roda the practitioners form a closed circle. Somesing, some play music and some play the game. In the rodas that follow Pastinha´s tradition(Capoeira Angola rodas) there are eight instruments that accompany the songs and theevent from beginning to end. The eight instruments belong to the percussion family andare frequently found in several Afro-Brazilian dance-music expressions, especially in thosefrom the Northeast region of the country 19 . This musical ensemble is comprised of threeberimbaus (musical bows) of different sizes known as gunga, meio and viola, two pan<strong>de</strong>iros(samba-like tambourines), one agogô (two belled instrument, not unlike a cow-bell, used inboth Candomblé and samba), one reco-reco (friction instrument) and one atabaque (drumused in Candomblé) 20 . In the rodas where Bimba´s tradition is followed, there are only threeinstruments: one berimbau (normally a meio) and two pan<strong>de</strong>iros. In other rodas, these twoformats may be varied with certain inclusions or exclusions 21 . However, at the very least, one17According to Fre<strong>de</strong>rico Abreu and Mestre Cobra Mansa (personal interview, Salvador, Bahia, April,2006), Capoeira Angola has increased in popularity over the last few years. However, the number ofCapoeira Angola practitioners is still very small when compared with the popularity of other styles.18Ana María Ochoa. Tradición, Género y Nación en el Bambuco. A Contratiempo, #9,Bogota, 1997, p. 43.19The northeastern region of Brazil inclu<strong>de</strong>s the following states: Alagoas, Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão,Paraiba, Pernambuco, Piaui, Rio Gran<strong>de</strong> do Norte and Sergipe. It is within this regionof Brazil that the Afro-<strong>de</strong>scendant culture has the greatest influence. Some of the local dancemusicexpressions related to Capoeira are: Samba <strong>de</strong> roda, Maculele, Maracatu, Candombles daBahia, Tambor <strong>de</strong> Mina, Tambor <strong>de</strong> Crioula and Bumba meu boi, among others.20In candomblé rituals in Bahia three atabaques of three different sizes are used: Rum, Rumpi andLe, being the first one the biggest drum, the second, the medium and the latter one, the smallest.Normally one Rumpi or one Le is used in Capoeira rodas. However, any of these drums are alwaysindistinctly addressed in Capoeira as atabaque.21Mestre Lua Rasta is a well known Mestre who teaches a style called Capoeira Angola da Rua(Street Capoeira Angola). He holds a very famous roda at the Terreiro <strong>de</strong> Jesús in Salvador, Bahia,Brazil every Friday evening. At one of his rodas I observed the use of a corno (the horn of a cowused as a simple trumpet), a two-skinned drum and a friction instrument in the form of a frog(and thus called a sapo).Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[149]

erimbau and one pan<strong>de</strong>iro remain in such ensembles and thus, could be consi<strong>de</strong>red essentialinstruments in a roda regardless the nature of the tradition of the group.A Capoeira Angola roda normally begins with the bateria, led by the gunga (the berimbauwith the lowest tonality). The mestre initiates the roda with a typical cry, “E-YEA!”, andthen sings a ladainha (an introductory song, sung as a solo). The mestre then continues witha responsorial song (the chulas) in which a one-line verse alternates with a one-line chorus(sung by the rest of the participants). Once the chulas have finished, the corridos (songs usedduring play) begin and these are led by the mestre or by one of the members of the bateria.At this point the game starts. Couples pass to the center of the circle to play Capoeira.Throughout the roda each participant assumes different roles: musician, lea<strong>de</strong>r of the songs,chorus or dancer. These roles change over the course of the roda and these changes followcertain rules adopted by the group. After one or two hours of jogos, the roda finishes with afinal cry from the mestre: “YE!”.The standardized ritual <strong>de</strong>scribed above varies from group to group <strong>de</strong>pending on theschool, the mestre and local influences. Many Capoeira Angola groups celebrate their rodaswith a format similar to this one. The types of games, lyrics and general musical aestheticcan vary very little or greatly between groups and the trend is towards the latter case whencomparing groups whose mestres originate from different regions of Brazil. There is a significantdifference between the music in Capoeira Regional (and Capoeira Contemporánea 22 )rodas, as compared to the music in Capoeira Angola rodas. An exhaustive analysis of thesedifferences exceeds the scope of this paper.Division of the Capoeira Song RepertoireThe use of categories is one of the most popular practices when studying complexissues (in our case a specific musical system). Meyer asserts that this is “a consequence ofthe limited capacity of human mind” 23 . Therefore, in many cases, the use of categories is ahelpful tool for the study of musical systems. Conversely, Merriam has greatly contributedto the un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of oral musical systems by proposing a ten-category classification ofsongs based on the social function of the songs 24 . Therefore, it is no won<strong>de</strong>r that many22Capoeira Contemporánea is the most common term used within the Capoeira realm to addresshybrid styles of Capoeira which combines features of Pastinha´s Capoeira Angola and Bimba´sCapoeira Regional.23Leonard B. Meyer. “Un universo <strong>de</strong> universales”, in Francisco Cruces et al. Las CulturasMusicales. Lecturas <strong>de</strong> Etnomusicología. Madrid: Editorial Trotta, 2001. pp. 241-242. Meyer statesthat it is not possible to un<strong>de</strong>rstand the variability within human cultures without un<strong>de</strong>rstandingthe constants implied by its formation. One of those constants is precisely our limited mind.24Alan Merriam. “Usos y funciones”, in Francisco Cruces et al. Las Culturas Musicales. Lecturas<strong>de</strong> Etnomusicología. Madrid: Editorial Trotta, 2001. pp. 285-294. Merriam proposes ten mainfunctions of music applicable to any society: emotional expression, aesthetic joy, entertainment,[150] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11

authors studying Capoeira have attempted to classify Capoeira songs. Among them Rego isremarkable 25 as his book inclu<strong>de</strong>s the first significant Capoeira songbook and uses a thematicclassification of Capoeira songs based on diverse criteria.This paper uses several levels of division in or<strong>de</strong>r to organize and make sense of theCapoeira song repertoire. First, the songs are discussed along their lines of function. TheCapoeira universe generally recognizes three different types of songs used at different momentsin the roda. These are ladainhas (a non-responsorial song sung by a soloist; it initiates theritual), chulas (one-line responsorial songs that follow the ladainha) and corridos (the songsused during play). Being able to recognize and differentiate between these three types ofsongs is necessary for a basic un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of the Capoeira song repertoire. Note that thispaper, for the sake of brevity, tends to focus on corridos in all discussions.Second, I introduce two overarching categories for Capoeira songs: “traditional” and“contemporary”. These two categories can be used to analyze both ladainhas and corridos;however, in this paper only corridos are discussed in this manner.Third, a thematic division of the corridos is introduced. This portion is somewhat relatedto Rego´s classification 26 ; however, some of his categories are rejected due to inconsistenciesin his criteria. I propose thirteen categories for the “traditional” corridos and fifteen for the“contemporary” corridos. The division by function proposed by Merriam will be used solelyas a theoretical base.Creating the initial compilation of songs was very complex given that information isdispersed, that sources are not always trustworthy and that songs exist in many versions.Given that Capoeira is an oral tradition that has been significantly impacted by the media, itis important to choose a hierarchy of musical sources. The three levels of orality that Zapatadistinguishes were taken into account in this paper: pure orality (such as live performances),mediated orality (such as recordings of live performances) and compound orality (whenoral material is influenced by written material) 27 . Thus, with regards to Capoeira music ascommunication, symbolic representation, physical response, reinforcing social rules, reinforcingsocial institutions and religious rites, contributing to the continuing stability of a culture andcontributing to the integration of society.25Wal<strong>de</strong>loir Rego. Ensaio Socio-etnografico <strong>de</strong> Capoeira. Salvador, Bahia, Editora Itapoa,1968: 235-255. In his book Rego inclu<strong>de</strong>s 139 Capoeira songs and proposes a division of theminto twelve categories: Diverse themes, songs of superstition, songs to insult, songs of women,cradle songs, <strong>de</strong>votion songs, religious songs, geographic songs, songs of praise, songs of challenge,children’s songs and beggars’ songs. Some of these categories were used in this work, but thein general the division criteria used by Rego is not very clear. At times it is very refined as inthe religious topics but vague and very general about issues relating to the roda itself. It is alsonoticeable that Rego does not distinguish between ladainhas, chulas or corridos.26Ibíd, pp. 235-255.27For a complete analysis of the subject of orality see John Fredy Zapata. Desarrollo Histórico <strong>de</strong>la Trova Antioqueña. Me<strong>de</strong>llín, unpublished thesis, Universidad <strong>de</strong> Antioquia, 2005: 37-57.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[151]

THEME 1The ladainhaYê!Tava em minha casaSem pensar nem imaginarQuando ouvi bater na portaMan<strong>de</strong>i minha mulher olharEla então me respon<strong>de</strong>uSalomão veio te buscarPara ajudar a vencerA guerra do ParanáMinha mãe então falouMeu filho você não váA batalha é perigosaEles po<strong>de</strong>m te matarA marinha é <strong>de</strong> guerraO exército <strong>de</strong> campanhaTodo mundo vai a guerraTodo mundo é quem apanhaCamará...!(Source: Bola Sete, 1997)YE-AAAA!I was in my houseNot thinking about anythingWhen I heard knocking at the doorI sent my woman to seeThen she answered meSalomon came looking for youTo help <strong>de</strong>fendIn the Paraná WarMy mom then spokeMy son you are not goingThe battle is dangerousThey might kill youThe navy is for warThe army leads a campaignEveryone goes to warEveryone gets hurtCamará...!(Translation by the author)a source of knowledge, the following or<strong>de</strong>r of importancewas <strong>de</strong>termined and adhered to: the rodas themselves, vi<strong>de</strong>orecordings of rodas, audio recordings of songs, writtendocuments and group websites.The differences betweem the versions of Capoeira songsrepresented a significant obstacle, as it is hard to <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>which version is more “authoritative”. Initially, I attemptedto unify the diverging versions, but as the research continued,it became clear that this was not possible or even useful. Arecognition of each version, with its differing lyrics (sometimessubject to minor spelling differences with significantinfluence on possible meanings), structure, melody andrhythm, was the first big achievement of this research: anexposition of the microcosm in each version of the songsthat could be studied not only on its own, but also as partof a family of songs.Division of the Songs intoLadainhas, Chulas and CorridosIt is wi<strong>de</strong>ly accepted in all Capoeira groups, regardlessthe ten<strong>de</strong>ncy or tradition, that there are three types of songs:ladainhas, chulas and corridos. With few exceptions, all thegroups use the songs in the same moment in the roda 28 .Therefore, there were no conflicts when dividing these songsalong these lines. We will first explore the most commonform of these three types of songs.The ladainha is the song that initiates the roda (exceptin cases where groups have not properly been initiated intothe Capoeira ritual by a formal mestre). It is generally a longsolo song in which the mestre tells stories and gives advice.In the groups that follow Pastinha’s tradition, the ladainhanormally starts with a call “E-YEAAAA!” and finishes upwith the word “Camará!” (see theme 1).28Although the ladainhas, corridos and chulas appear in theroda in specific moments and have certain forms, some ofthe groups (especially Capoeira Regional groups) have incorporatednew forms of singing by changing the responsorialnature of the songs.[152] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11

In most rodas, only one ladainha is sung, however, sometimes, when the mestre is goingto play (partway through the roda), he (or she) kneels at the foot of the gunga and sings aladainha, as if he/she were reinitiating the roda. The roda may be reinitiated in this way forother reasons, such as when an important visitor has arrived.The chulas are short responsorial songs that follow the ladainha and prepare for the firstjogo. They have a standardized size of four bars and the melodies generally go as follows:Chulas are barely consi<strong>de</strong>red as songs themselves. Rather, they are often seen as thenatural end of the ladainha or the mere transition between the “mystical ladainha” and the“bright corridos” 29 . Nonetheless, the chulas have a standardized form and they hold the mostuniform musical and poetic form among the three types of Capoeira songs. The chorus echoesthe chula sung by the soloist adding the word “camará!” at the end. In a standard roda thenumber of chulas may vary, but normally mestres do not spend more than one or two minutessinging them. The themes of the chula are often related to the ladainha sung previously.The corridos have many different sizes and forms but they are characterized –as are chulas–by their responsorial nature. They are the songs used when the physical game is played.Their primary function is to <strong>de</strong>scribe and mediate the jogo, though some lyrics are relatedto other themes. Further along I will give examples of corridos, as all further organization ofCapoeira songs <strong>de</strong>als specifically with corridos.Since Capoeira practitioners from both Brazil and other countries are influenced by localand popular musical genres, their interpretation of the ladainhas and corridos has changed.For example Mestre Acor<strong>de</strong>on has recor<strong>de</strong>d a responsorial ladainha called “Vamos pedir oaxé 30 ” (see theme 2).29In many occasions mestres sing their ladainhas as if they were praying, in several cases closingtheir eyes. Moreover, during the ladainha many mestres kneel on the foot of the berimbau andperform various religious gestures. In contrast, while singing corridos, mestres often laugh andjoke.30Axé is an African concept in the nagô which <strong>de</strong>signates the magical-sacred force inherent inevery divinity and being of nature. In Capoeira, axé is the energy that all the participants sharein the roda and is seen as being sustained by the music.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[153]

In or<strong>de</strong>r to organize Capoeira songs as “traditional” or “contemporary”, one must <strong>de</strong>finethese two terms. The transformation of traditions has always caused controversy, as Ochoamentions 35 . Moreover, the continuation of a tradition implies its capacity to manage atransformation process that allows it to adapt to new contexts and thus, logically, not remainexactly the same through time 36 . This sort of un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of tradition is greatly importantin our times of accelerated changes in society.Capoeira is not immune to the controversy over tradition. There is one group of practitioners,the angoleiros (those who play Capoeira Angola), who believe they are the keepersof tradition, while there is another group, the regionales/contemporáneos (those who playCapoeira Regional and/or Capoeira contemporánea), who, in general, believe that Capoeiramust evolve. Of course, both have their own “tradition”, but the angoleiros claim that theirsis ol<strong>de</strong>r and thus, more authentic.Before analyzing this controversial issue, it is necessary to state that most of the actualCapoeira mestres follow a tradition that can be traced back through time to Mestre Pastinha(in the case of the Capoeira Angola mestres) or to Mestre Bimba (in the case of the CapoeiraRegional mestres). Were one to use this criterion, two main genealogies would be found: thefollowers of Mestre Pastinha and the followers of Mestre Bimba 37 . This two-pronged genealogicaldivision is part of an overarching discourse within Capoeira today.Although every group that I have visited followed one of the two main traditionsmentioned above, the division remains problematic. There are certain groups which donot follow a unique tradition like the “purist” angoleiros or the regionales. They have a moreopen range of influences and tend to practice both styles and hence will be addressed in thispaper as Capoeira Contemporanea groups 38 . Moreover, most of the Capoeira Contemporáneagroups recognize Capoeira Angola as the ol<strong>de</strong>r tradition and begin their rodas with songsinclu<strong>de</strong>: Navío negreiro (famous MPB song recor<strong>de</strong>d by Caetano Veloso), Magalenha (famoussamba recor<strong>de</strong>d by Chico Men<strong>de</strong>s), Chico Parauera (famous samba from Bahia) Xo-xua (famousMPB song recor<strong>de</strong>d by Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso) and Na praia da Amaralina (popularSamba <strong>de</strong> roda from Bahia recor<strong>de</strong>d by Carolina Soares).35Ana María Ochoa. Tradición, Género y Nación en el Bambuco. A Contratiempo, #9,Bogotá, 1997, p. 35.36Ibid, p. 35-36.37Although most of the groups fit well in these categories, there are other groups that follow adifferent tradition, such as the groups affiliated with the Associação Brasileira Cultural <strong>de</strong> CapoeiraPalmares whose master is Mestre Nô. Although he is an angoleiro, he was taught by Mestre Pirró,who was not a follower of any of Pastinha’s groups. There are also many well known CapoeiraAngola mestres who actually were taught by mestres who did not learn with Mestre Pastinha, butwere nonetheless greatly influenced by him. This is the case of mestres like Lua <strong>de</strong> Bobó, Noronha,Espinho Remoso, Cobrinha Ver<strong>de</strong>, Bom Cabrito and Boa Gente.38This is the case of the Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Longe do Mar in Mexico City, visited by the authorin 2002.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[155]

THEME 3Foi, com gran<strong>de</strong> tristezaQue meu berimbauAnunciou sua partidaHá que coisa mais sofridaHá mais quanta dorEncerra uma <strong>de</strong>spedidaMe <strong>de</strong>ixó tanta sauda<strong>de</strong>Me <strong>de</strong>ixó tanta lembrançaQuando foi me feiz chorarComo nos tempos <strong>de</strong> criançaQuanta tristeza me-dáMe-lembrar que todo tinhaQue acabar assimQuando você me pi<strong>de</strong>uPara eu largar a capoeiraMas você não enten<strong>de</strong>uQue ela fais parte <strong>de</strong> mimEu que sempre lhe-pedíNão me faza escolherEntre você e a capoeiraPoque você é quem vai per<strong>de</strong>rHoje eu choro <strong>de</strong> sauda<strong>de</strong>Mas prefiro a <strong>de</strong>spedidaPois largar a capoeiraÉ o mesmo que largar a vidaO sereiaO minha sereiaEu vou jogando a capoeiraPra tristeza eu espantarO sereiaO minha sereia(Heard in roda of the group Longedo Mar, México, D.F., June 2002)It was with a lot of painThat my berimbauAnnounced her leavingAy! what a thing to sufferAy! How much painIs in a farewellIt left me so nostalgicIt left me such remembrancesWhen she left I criedLike when I was a childHow big is the sadnessRemembering that everythingHas to end like thatWhen you asked meTo leave CapoeiraYou did not un<strong>de</strong>rstandThat it is part of me[156]I always Ensayos. beg you Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDo not make Diciembre me choose 2006, No. 11frequently used in the most purist Capoeira Angola groupsand ostensibly change their style of play for that portion oftheir ritual. However, significant changes not only in thelyrics, but also in the musical aesthetic remain. Searchingfor authoritative origins in this mix is difficult.Given these consi<strong>de</strong>rations, it appears difficult to findwell-based criteria for the division between “traditional” and“contemporary” songs. Nonetheless, I propose a division ofCapoeira songs into two groups: a) the songs used by thegroups that exclusively follow Pastinha’s tradition, whichI will call “traditional”, and b) the songs used by the othergroups (Capoeira Regional and Contemporánea), which, ofcourse, have their own tradition but will be referred to as“contemporary” for the purposes of differentiation.Although this criterion seems arbitrary, it emerged asthe least refutable option. It was observed that the groupsthat follow Pastinha’s tradition maintain a close relationshipamong themselves. In fact, it seems as if they function like abig family whose center spins towards Salvador 39 . This mightbe explained by many reasons: first, Capoeira Angola groupsand mestres are relatively few when compared to CapoeiraRegional/Contemporánea groups, which enhances their relationship.Second, Capoeira Angola mestres and practicionersare very marked by Pastinha’s philosophy which is veryfocused onin preserving their tradition. This aspect doesnot seem very strong in Capoeira Regional/Contemporáneamestres and groups.By using this criterion it was possible to find importantdifferences in rhythm, melody, and musical form betweenthe “traditional” and “contemporary” songs, although a furtheranalysis will show that they maintain several common39According to Mestre Cobra Mansa (personal interview,Costa Rica, 2005), all Capoeira Angola groups, whetherlocated in Brazil or overseas, have received direct or indirectinfluence of the Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Angola Pelourinho andAca<strong>de</strong>mia <strong>de</strong> João Pequeno <strong>de</strong> Pastinha. These two importantgroups hea<strong>de</strong>d by Mestre Moraes and Mestre João Pequeno areresponsible to a great extent for the popularity that CapoeiraAngola enjoys today.

elements, such as the purpose of the songs in the roda, many lyrics and certain musical andpoetic forms.Let me <strong>de</strong>scribe some of the significant differences that can be observed in the use ofCapoeira songs between Capoeira Angola and Capoeira Regional/Contemporánea groups.The corrido “Aidê” distinctly shows some of the differences (and consistencies) in lyrics,melody and rhythm.Transcription by the author based on a song heard in a roda at the Capoeira Angola Center ofMestre João Gran<strong>de</strong>, N.Y, USA, Sept. 2003.Transcription by the author based on a song heard in a roda by Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Longe do Mar,Mexico City, May, 2002.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[157]

Between you and CapoeiraBecause you will loseToday I cry with nostalgiaBut I prefer your farewellBecause leaving CapoeiraIs like leaving my own lifeOh mermaidOh my mermaidI am playing CapoeiraTo scare away my sadnessOh mermaidOh my mermaid(Translated by the author)THEME 4Eu sou angoleiroAngoleiro sim SinhôEu sou angoleiroAngoleiro <strong>de</strong> valorEu sou angoleiroAngoleiro é que eu souEu sou angoleiroAngoleiro jogadorI am an angoleiroAngoleiro, yes SirI am an angoleiroA brave angoleiroI am an angoleiroAngoleiro is what I amI am an angoleiroAn Angola player(Translation by the author)THEME 5Capoeira pra estrangeiroMeu irmãoÉ mato!Capoeira brasileiraMeu compadreÉ <strong>de</strong> matar!Berimbau tá chamandoOlha a roda formandoVai se benzendoPra entrarO toque é <strong>de</strong> AngolaSão Bento PequenoCavalaria e Iúna[158] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11The version shown above is probably the most commonlyheard in both the Capoeira Angola and Regional/Contemporánea groups. One can see that the soloist’s partsuperimposes triplets over the binary time played by thepercussion. The chorus alternates with the verses every twobars with “Ai, Ai Ai<strong>de</strong>ee!”.Now let us look at a second version of this same corrido.This latter version of the corrido “Aidê”, which was heardin one of the groups that practices Capoeira Contemporánea,is quite different than the first one. Although they are versionsof the same song, a question emerges: which of themshould be consi<strong>de</strong>red “traditional”? The first one is sung inthe group of Mestre João Gran<strong>de</strong>, one of the ol<strong>de</strong>st CapoeiraAngola mestres and a former stu<strong>de</strong>nt of Mestre Pastinha. Thesecond one is sung by a group in México, where Capoeiraarrived some fourteen years ago and which lacks the permanentpresence of a Brazilian mestre (at least in mid-2002) 40 .Clearly the first version might be traced back to an ol<strong>de</strong>r andpresumably more formal tradition and the second one couldbe seen as a further alteration (but this is not reason enoughto say that it does not imply a tradition in itself).A further difference is that, in some cases, angoleiroschoose to sing particular songs and regionales/contemporáneos,others. There are a great number of songs specifically i<strong>de</strong>ntifiedwith the Pastinha’s angoleiros or with regionales/contemporaneos.An example of the former is the corrido “Eu sou angoleiro”,consi<strong>de</strong>red an anthem by the angoleiros (theme 4).An example for the latter is “Capoeira pra estrangeiro”,which was recor<strong>de</strong>d by the Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Cordão <strong>de</strong>Ouro and is very frequently used in Capoeira Regional/Contemporánearodas (e.g. Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Abolição, Me<strong>de</strong>llín,Colombia, see theme 5).40In personal interview with Ian Night (one of the most experiencedMexican Capoeira Angola practitioners) in MéxicoCity, May, 2002, he asserted that Capoeira was brought toMexico by the Argentine Mariano Andra<strong>de</strong> in 1992. ThisCapoeira pioneer in Mexico is now a stu<strong>de</strong>nt of Mestre Curió(a well-known Capoeira mestre from Salvador who was stu<strong>de</strong>ntof Pastinha) and ostensibly holds the titleof contramestre (onestep below mestre).

On the other hand, Capoeira Angola groups have presumably taken songs from the Regionalrepertoire, as in the case of the corrido “Nhem, nhem, nhem”, which Capoeira Regionalpractitioners claim to be a personal composition of Mestre Bimba. The following version washeard in a roda with the professor Minhoca 41 in Mexico City (see theme 6).Versions of this corrido heard in Capoeira Regional/Contemporánea groups are very similarto versions heard in Capoeira Angola groups.Division of the Corridos by ThemeIn Capoeira, the corridos have two primary functions: to <strong>de</strong>scribe and to mediate theroda. Beyond this, there are historical, romantic, and religious songs as well as songs thatchallenge and songs that exalt one’s condition. The analysis gets complicated as some songsfit into more than one category. This is the case of the corrido “Marimbondo”. The chorusmentions the way in which Catholics cross themselves, “Pelo sinal”, and implies superstitionsaround this; however, the line “marimbondo me mor<strong>de</strong>u” will <strong>de</strong>scribe the way in which aplayer took a hit in the roda (see theme 7).It is clear that “traditional” corridos use popular poetry in the lyrics. Thus, words relatingto nature (rivers, seas, animals, forests, trees, rain, etc.) were an obvious basis for the constructionof Capoeira songs in the past. Many songs mention animals of the Brazilian forestsand draw parallels with players. The animals most mentioned by the angoleiro poets are snakesand birds, although monkeys, dogs, crocodiles, oxen, felines and fish are also mentioned.Another element of nature often used by angoleiros is the plants of the Northeast region ofBrazil. For example, they mention trees such as baraúna, gameleira, pau-brasil, maçaranduba,jacarandá and beriba (this last tree provi<strong>de</strong>s the wood used to make berimbaus). They alsomention typical fruits, vegetables and dishes from the Northeast region of Brazil, such as<strong>de</strong>ndê 42 , quiabo (okra), limão (lime), abobora (squash), mamão (papaya), farinha <strong>de</strong> mandioca(yucca flour), caruru and acarajé 43 .The musical content of the Capoeira Angola songs was divi<strong>de</strong>d by theme in thirteencategories during my original investigation (presented below with an example).41Minhoca is a Brazilian stu<strong>de</strong>nt of the Aca<strong>de</strong>mia <strong>de</strong> João Pequeno <strong>de</strong> Pastinha who spent one yearin México teaching Capoeira Angola in 2002. He has already received the title of contramestre byhis mestre and brother Mestre Pé <strong>de</strong> Chumbo, who is also a stu<strong>de</strong>nt of Mestre João Pequeno.42Dendê is the fruit from a palm tree that secretes a red oil used in cooking in the Northeast ofBrazil. Dendê also signifies, in Capoeira, the special way in which experienced capoeiristas performin the roda, whether playing instruments, singing or playing the game.43Caruru and acarajé are two typical foods from Bahia and easily found in Salvador. The formeris a food ma<strong>de</strong> from okra, onion, shrimp, palm oil and toasted nuts and the latter is a food ma<strong>de</strong>with shrimp, chili peppers and bean flour.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[159]

A mandinga do jogoO cuidado com a gingaÉ pra não vacilarCapoeira é ligeiraEla é brasileiraEla é <strong>de</strong> matarCapoeira é ligeiraEla é BrasileiraEla é <strong>de</strong> matarGrupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira AboliçãoCapoeira isfor foreignersMy brotherIt’s a forest!Brazilian CapoeiraMy comra<strong>de</strong>It kills!The berimbau is callingThe roda is formingStart blessing yourselfSo you may enterThe rhythm is AngolaSão Bento PequenoCavalaria and IúnaThe mandinga of the gameWatch your gingaDo not hesitateCapoeira is fastIt is BrazilianIt killsCapoeira is fastIt is BrazilianIt kills(Translation by the author)THEME 6NHEM, NHEM, NHEMOlha chora o meninoNhem, nhem, nhemO menino chorouNhem, nhem, nhemÉ porque não mamouNhem, nhem, nhemCale a boca meninoCapoeira Angola groupsWHAA,WHAA,WHAALook the child criesWhaa, whaaa, whaa[160] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11Categories for “traditional” corridosTHEMEDescriptive songs used assalutation, used for startingthe roda or for when anangoleiro arrives.Descriptive songs usedas farewell, for finishingup the roda, or when anangoleiro leaves.Descriptive songs for aplayer who takes a hit or is<strong>de</strong>cieved in the game.Descriptive songs forintrinsic elements suchas the instruments andphilosophy.Mediating songs thatincite a stronger game.Mediating songs thatincite a slower game.Mediating songs thatinciting the music toplay in an specific way.ExampleCamungerêComo vai como está?CamungerêComo vai vos-mecê?CamungerêEu vou bem <strong>de</strong> saú<strong>de</strong>CamungerêA<strong>de</strong>us corina, dão, dãoVou-me embora, vou me emboraA<strong>de</strong>us corina, dão, dãoComo já disse que vouA<strong>de</strong>us corina, dão, dãoMas prossegue o berimbauMas meu facão bateu embaixoA bananeira caiuMas meu facão bateu embaixoA bananeira caiuCai, cai bananeiraBeriba é pauPra fazer berimbauMas beriba é pauPra fazer berimbauBeriba é pauPra fazer berimbauQuebra, quebra gerebaVou quebrar tudo hojeAmanhá nada quebraQuebra, quebra gerebaVou quebrar tudo hojeAmanhá quem é que quebraQuebra, quebra gerebaAi ai, AidêJoga bonito que eu quero verAi, Ai, AidêOlha, jogo uma coisa que eu queroapren<strong>de</strong>rAi, Ai, AidêAidê, Aidê, Aidê, AidêChora violaChoraOi chora violaChoráOi viola mentiraChorá

Categories for “traditional” corridosTHEMEMediating songs that incite achallenge among players.Historical songsSongs that mention women.Superstitious songs that askfor protection from gods andsaints, both African andCatholic.Songs that exalt Capoeira asa practice and as cultureExampleJogue comigoCom muito cuidadoCom muito cuidadoCom muito cuidadoJogue comigoCon muito cuidadoCom muito cuidadoQue eu sou <strong>de</strong>licadoQuando o nêgo fugia no matoO Sinhô mandou lhe buscarO nêgo então sacaricavaBatendo o homem que vinha pegarQuem é esse homemCapitão do matoQuem era esse homemCapitão do matoA mulher mata o homemÉ <strong>de</strong>baixo da saiaA mulher mata o homemÉ <strong>de</strong>baixo da saiaA mulher mata o homemÔ Santa Barbara que relampuêÔ Santa Barbara que relampuáÔ Santa Barbara que relampuêQue relampuê, que relampuáÔ Santa Barbara que relampuêÉ legal, é legalJogar capoeira é um negocio legalÉ legal, é legalJogar capoeira e não levar pauÉ legal, é legalOi! tocar berimbau é um negócio legalThe child criedWhaa, whaaa, whaaIt is because he did not suckleWhaa, whaaa, whaaShut up boy(Translation by the author)THEME 7MarimbondoMarimbondo, marimbondoPelo sinalMarimbondo me mor<strong>de</strong>uPelo sinalOi me mor<strong>de</strong>u foi no umbigoPelo sinalMas se fosse mais pra baixoPelo sinalO meu caso estava perdido(Heard in the recording “Capoeira”by Mestres Wal<strong>de</strong>mar y Canjiquinha)MarimbondoMarimbondo, marimbondoBy the sign of the Holy CrossMarimbondo bit meBy the sign of the Holy CrossIt bit my bellybuttonBy the sign of the Holy CrossHad it bit me any lowerBy the sign of the Holy CrossMy case was over(Translated by the author)Songs of free themeQuem não po<strong>de</strong> com mandinga, ParanáNão carrega patuá, ParanáParanaue, Paranaue, ParanáQuem não po<strong>de</strong> com Besouro, ParanáNão assanha Mangangá, ParanáParanaue, Paranaue, ParanáAnalisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[161]

A simple count the number of collected songs in each category led to the conclusionthat the favorite themes in “traditional” corridos are: a) the <strong>de</strong>scriptive songs for intrinsicaspects, b) the superstition mediating, and c) the songs that incite challenges. On the otherhand, the repertoire contains few <strong>de</strong>scriptive salutation songs and few free theme songs 44 .It is also interesting that in “traditional” corridos the preferred animals are snakes, birdsand dogs, the fruit most mentioned is coconut and the preferred plant is <strong>de</strong>ndê. The mostpopular characters are Pastinha and Besouro 45 . Bahia and Angola are the most commonlymentioned places. The musical instrument most mentioned is the berimbau, but there isalmost no mention of the rhythms played by the berimbau. Finally, the most frequentlyreferred to movements are ginga and rasteira.It is remarkable that, although the groups of each stream often make a special effortto mark the differences with respect to the groups of the other stream, they share almostall of the same themes in their songs. The contemporary Capoeira groups have introduceda couple of new themes in their songs: romantic songs whose exaggerated lyricism can berelated to other Brazilian genres like bossanova or certain types of samba, and anthem songsthat function as i<strong>de</strong>ntifiers for certain groups or schools 46 . The last category <strong>de</strong>monstratesthe ten<strong>de</strong>ncy to mark the differences between groups by creating their own repertory ofsongs, including a song that exalts the group and its members (see Additional Categories forcontemporary Songs).In accordance to my simple counting system, the favorite themes in contemporarycorridos are: a) the <strong>de</strong>scriptive songs for intrinsic aspects, b) the historic songs and c) thechallenge songs. On the other hand, the repertoire contains few <strong>de</strong>scriptive songs for aplayer who takes a hit and few <strong>de</strong>scriptive farewell songs.44In the original work by the author, among a total of 174 traditional corridos, 34 were classifiedas <strong>de</strong>scriptive songs for intrinsic aspects, 18 as superstition songs, 17 as songs that encourage challenges,16 as <strong>de</strong>scriptive songs for a player who takes a hit, 16 as songs that mention women, 15 asmediating songs that incitate slower game, 11 as historical songs, 11 as farewell songs, 9 as songsthat condition the way to play music, 8 as songs that encourage strong play, 7 as songs that exaltCapoeira as a practice and as a culture, 6 as songs for salutation and 6 as free theme songs.45Besouro Mangangá is one of the most celebrated characters in the songs of Capoeira and byfar, the greatest legend. The myth is easily pieced together using the information supplied by theCapoeira song repertoire. It is said that he was a black slave and a brave man who <strong>de</strong>fen<strong>de</strong>d hispeople and fought against the Portuguese and the police. It is also said that he had corpo fechado,meaning that he could not be killed with a weapon. It is also said that he was killed at the Engenho <strong>de</strong>Maracangalha (sugar cane production and processing farm) with a faca <strong>de</strong> tucum (a knife ma<strong>de</strong> froma specific type of wood), the only thing able to break the enchantment that protected him.46Some Capoeira Angola groups have anthems too, but they are barely heard in public rodas. Thatis why this category was not inclu<strong>de</strong>d in traditional songs. One example of this type of songs isthe corrido “O quilombo da FICA”, that mentions the name of the International Foundation ofCapoeira Angola (“FICA” is the abbreviation in Portuguese). This is one of the biggest CapoeiraAngola groups worldwi<strong>de</strong> with its main aca<strong>de</strong>my in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. The FICA (or ICAFin English) is hea<strong>de</strong>d by Mestres Valmir, Cobra Mansa and Jurandir.[162] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11

ADITIONAL Categoriesfor “CONTEMPORARY” SONGSTHEMERomanticsongsAnthemsExampleRomantic songsMeu berimbauMeu amante verda<strong>de</strong>iroNa tristeza e na alegriaSempre foi meu companheiroNa volta do mundo que eu douNa volta do mundo que dáNa volta do mundo que eu douNa volta do mundo que dáJá tocou pra seu PastinhaPra seu Bimba e ParanáJá rodou por esse mundoNão sei on<strong>de</strong> vai pararHoje tem roda no morroOuvi berimbau tocarÉ o Grupo Axé CapoeiraQue acaba <strong>de</strong> chegarHoje tem roda no morroOuvi berimbau tocarÉ o Grupo Axé CapoeiraQue acaba <strong>de</strong> chegarOlha o Grupo Axé CapoeiraTem raiz e também tradiçãoTodos jogam capoeiraCom amor no coraçãoHoje tem roda no morroOuvi berimbau tocarÉ o Grupo Axé CapoeiraQue acaba <strong>de</strong> chegarOlha o Grupo Axé CapoeiraNasceu no Brasil foi para muito lugarJá foi na Itália, SuíçaEstados Unidos e também Canadá(Mestre Barrão, mestre of theGrupo Axe Capoeira)It is also interesting that in “contemporary”songs the preferred animals are oxenand monkeys, the plants most mentionedare the sugar cane and the beriba and themost popular characters are Bimba, Pastinhaand Besouro. The places most mentioned areBahia and Luanda. The musical instrumentmost mentioned is, as before, the berimbau.Contemporary corridos frequently mentionthe rhythms of the berimbau, most commonlymentioning the São Bento, Angola, Benguelaand Iúna rhythms. Finally, the movementsin Capoeira that are most mentioned arealso ginga and rasteira, as well as meia-luaand armada.It is noticeable that in the repertoires ofboth styles, Pastinha and Besouro appear asthe most popular characters, only superse<strong>de</strong>din contemporary corridos by the mentionof Bimba. The mention by contemporarygroups of Pastinha can be perhaps interpretedas recognition to an “ol<strong>de</strong>r tradition”.A reciprocal recognition of Bimba and hiscontribution to Capoeira is inexistent in thesongs of the traditional groups.Analysis of Differences in Lyrics andPoetic Structure of the CorridosThe next paragraphs discuss some of thetypical differences among corridos. There areillustrative examples from both the traditionaland contemporary songs.Minor Spelling DifferencesSometimes the differences between twoversions of one song may look very small, butare significant, nonetheless. For example,while the corrido “O Dendê, o Dendê” is sung

THEME 8Vou dizer a <strong>de</strong>ndêSou homen, não sou mulherManda dizer a <strong>de</strong>ndêSou homen, não sou mulher(From the CD “Capoeira Angola”,Mestre Jogo <strong>de</strong> Dentro, 1999)I am going to tell DendêI am a man not a womanGo tell DendêI am a man not a woman(Translated by the author)THEME 9Vou dizer a <strong>de</strong>ndêSou homen, não sou molequeManda dizer a <strong>de</strong>ndêSou homen, não sou moleque(Version sung by Mestre CobraMansa in a Capoeira workshop inManagua, Nicaragua, 2005)I am going to tell DendêI am a man not a boyGo tell DendêI am a man not a boy(Translated by the author)THEME 10: quadraCaminando pela ruaUma cobra me mor<strong>de</strong>uMeu veneno era mais forteE foi a cobra quem morreuAi ai ai aiSão Bento me chamaAi ai ai aiSão Bento chamouAi ai ai ai(Version heard in roda of “CapoeiraAngola Center Of MestreJoão Gran<strong>de</strong>”, New York, 2003)Walking down the streetA snake bit meMy venom was strongerAnd it was the snake who diedAy ay ay aySaint Benedict is calling meAy ay ay aySaint Benedict called meAy ay ay ayby Mestre Jogo <strong>de</strong> Dentro (a young Capoeira Angola master)as shown in theme 8. Nontheless Mestre Cobra Mansa saysthat this corrido was previously sung as shown in theme 9.Although the one-word difference here is minor at firstglance, the implication is remarkable. Whereas the firstversion of this corrido shows a sexist stance, the second onepresents age-based discrimination.Differences in Poetic Structure of the VersesAnother important difference in the various versionsof the corridos is the poetic structure of the verses. The basicstructure for the verses of a Capoeira Angola corrido is one, twoor four lines, sung by the soloist, and echoed by the chorus(whose response is of equal length). This structure is alteredat times by including one (or sometimes more) quadra 47 atthe beginning of the corrido. The quadra is a four-line verse,which could prece<strong>de</strong> virtually any corrido. Quadras used inthese circumstances are never echoed by the chorus. Whilethese quadras are most often improvised or taken fromladainhas and used to <strong>de</strong>scribe what is happening in oneparticular moment in the roda, some of these quadras havebeen associated with specific corridos and adopted by manygroups, both Angola and Regional/Contemporánea.The quadra that appears in the four first verses of theme10 is a specific combination of lyrics commonly heard.Note however, that some groups (e.g. Mestre Bimba’sgroup, as heard on the album Curso <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Regional)sing this corrido but do not inclu<strong>de</strong> the quadra.47Quadra is a four-line verse with rhyming pairs. It is wi<strong>de</strong>lyused both in literature and songs in Portuguese. Perhaps thecorrect English word is quatrain. The general use of the termin this paper must be distinguished from the quadras <strong>de</strong> MestreBimba, which are also four-line verses, but used specificallyas introductory songs in Capoeira Regional groups that followBimba’s tradition strictly. These particular quadras are notdiscussed in this paper.(Translation by the author)

Analysis of Differences in Musical Aesthetic of the CorridosIt can be said that Capoeira corridos are responsorial and monophonic, as the chorus respondsin unison; however, one may hear thirds or even false intonations in the chorus responsedue to individuals’ vocal capacities. There are no rules for intonation in the group, as thereare no harmonic or melodic instruments in the bateria to support harmony. A song in whichparallel thirds are often sung is the corrido Paranaué.Transcription by the author based on roda of the group Banda do Saci, in Mexico City, in March2002The melody of traditional corridos is very simple. The melodic periods of the “traditional”corridos almost always bear two phrases: the antece<strong>de</strong>nt phrase which conclu<strong>de</strong>s with adominant ca<strong>de</strong>nce and the consequent phrase which conclu<strong>de</strong>s with a tonic ca<strong>de</strong>nce. Themost common use of this structure is as follows: the soloist introduces the unique melodicperiod, then he/she leaves the antece<strong>de</strong>nt phrase of the melodic period to the chorus and he/she sings the consequent phrase completing the melodic period. The soloist and the chorusalternate these two phrases during the whole corrido. In general, the soloist improvises versesin his/her part, while the chorus sings a fixed verse.Transcription by the author based on a roda by the Grupo <strong>de</strong> Estudio <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Angola Raiz inSan Jose, Costa Rica, January 2003.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[165]

Although the structure <strong>de</strong>picted above is one of the most frequently seen in “traditional”corridos, there are other uses of this structure in which the soloist’s and the chorus’parts are shorter, splitting the melodic period into four. A good example is the corrido“Camungere”.Transcription by the author based on a roda by the Grupo <strong>de</strong> Estudio <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Angola <strong>de</strong>Nicaragua in Managua, April 2005.On the other hand there are corridos whose melodic period is not divi<strong>de</strong>d and thus, thesoloist’s and chorus’ parts alternate over whole melodic periods. One example would be thecorrido “Quem vem la sou eu”.Transcription by the author based on a roda by the Capoeira Angola Center of Mestre JoãoGran<strong>de</strong> in New York, September 2003.[166] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11

Even though many contemporary corridos share the structure <strong>de</strong>scribed above, they alsoexhibit many other uses of the structure. While an exhaustive explanation is beyond thebreadth of this paper, in brief, the role of the chorus is more active, as its part is not alwaysfixed, neither in melody nor in lyrics. Sometimes, the length of the chorus’ part might evenchange within the same corrido. To <strong>de</strong>monstrate this sort of variation, the next exampleof a song heard in a roda by the Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Abolicão in San José, Costa Rica, showsalternating melodic periods sung by the soloist and the chorus that differ both in melodyand lyrics.Transcription by the author based on a roda by the Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Abolicão in San José,Costa Rica, March 2003.An important thing to keep in mind when analyzing musical aesthetics of corridos inCapoeira is that most of the mestres <strong>de</strong>velop a particular style of singing the Capoeira repertoire.That is why the melodies for different corridos frequently vary from group to group.Several examples might be provi<strong>de</strong>d, but I will center my attention on Mestre Moraes, whohas a distinctive and well-known style.According to Mestre Otavio Brazil 48 , some mestres, such as Moraes, have a special wayof singing, “cantam pra <strong>de</strong>ntro”, which means that as they sing, the songs go into their bodies.Such concepts contribute to or perhaps result from the mystical discourse that continues tosurround Capoeira. Based on vi<strong>de</strong>os and other recordings, the noteworthy technical aspects48Personal interview with Mestre Otavio Brazil San Jose, Costa Rica, 2001.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[167]

of Mestre Moraes’s singing style are: a) he interjects the melody with calls before and afterhis part (the soloist’s part) in the corridos that he is leading, b) he overlaps tertiary melodicrhythms with the binary percussion base and c) his voice is very nasal.Below are two transcribed versions of the corrido “Paranaué”. The first one was takenfrom a recording that features Mestre Moraes and illustrates aspects of his melodic style.The second one was taken from another recording and shows a more standardized version,which is generally found in Capoeira rodas outsi<strong>de</strong> of Brazil.Transcription based on the version recor<strong>de</strong>d by Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Angola Pelourinho “CapoeiraAngola From Salvador” (1996).Transcription based on the version recor<strong>de</strong>d by Grupo <strong>de</strong> Capoeira Baraka, “Capoeira Baraka”(date unknown).[168] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11

While the first version exhibits a more intricate rhythm combining binary and tertiarymusical forms, the second one shows the repeated use of the following rhythmic pattern 49 :As Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro is not only the birthplace of Bossanova but also an important centrethat influenced the early <strong>de</strong>velopment of Capoeira, further investigation of the relationshipbetween these rhythms could prove interesting.ConclusionIn this paper, I proposed a division of the Capoeira song repertoire using specific criteria.Furthermore, I analyzed some poetic and musical elements of Capoeira songs in or<strong>de</strong>r tobetter un<strong>de</strong>rstand the intricacy of Capoeira. There are different versions of Capoeira songsthat are, simultaneously, unique and representative of differing microcosms within the realmof Capoeira, and part of a larger family of songs.This work proves that it is possible to approach the universe of Capoeira through itsmusic. This type of approach is indispensable given that Capoeira is an oral tradition wherethe mestres pass down their knowledge through stories most often in the form of songs. Froma didactic point of view, the study of the song repertoire is important for the attainment of abetter un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of Capoeira. This is advisable for all Capoeira practitioners and especiallyfor those not native to Brazil. The division of these songs by theme allows one to seehow Capoeira songs are integrated into the ritual. Finally, the study of these songs makes itclear that they are a fertile source of historical, philosophical and technical information.An analysis of the lyrics, poetic structure and musical aesthetic shows that althoughboth “traditional” and “contemporary” styles have significant differences, the corridos ofboth styles still share a great number of elements in common. The styles diverge in theuse of tertiary melodic rhythms that overlap a binary percussion base (“traditionalists”)compared to more syncopated melodic rhythms (“contemporaries”) 50 ; however, the stylesparallel each other in such elements as the common themes, the responsorial nature ofthe songs, the alternation of melodic periods (or fractions of them), and the improvisationexhibited by the soloist.49This rhythmic pattern is similar to the rhythm of many Bossanova songs, such as “Berimbau”by Vinicius <strong>de</strong> Moraes and Ba<strong>de</strong>n Powell, “Gema” by Caetano Veloso or “Samba <strong>de</strong> Uma notaSó” by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Newton Mendoça.50Not that contemporary songs do not use tertiary melodic rhythms, but this musical figureappears very infrequently. Traditional songs are also syncopated but to a lesser extent thancontemporary songs.Analisys and Proposed Organization of the Capoeira Song RepertoireaJuan Diego Díaz[169]

The tensions between Capoeira groups for the recognition as “authentic” and/or “traditional”represents a <strong>de</strong>sire for reaffirmation as individuals and as groups in societies thatsuffer rapid change. Taking up and <strong>de</strong>fending a tradition as one’s own can be seen as a way ofresisting such change. Often overlooked and misun<strong>de</strong>rstood is the fact that the roots of theentire ritual, including the music, are i<strong>de</strong>ntical. As both si<strong>de</strong>s are involved in the same fightfor recognition, it is not surprising that the changes that they have incorporated into theirpractice go in the same direction. This has been <strong>de</strong>picted through a study of their music.[170] Ensayos. Historia y teoría <strong>de</strong>l arteDiciembre 2006, No. 11