Water Quality in the Central Columbia Plateau - USGS

Water Quality in the Central Columbia Plateau - USGS

Water Quality in the Central Columbia Plateau - USGS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

science for a chang<strong>in</strong>g world<br />

<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong><br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton and Idaho, 1992–95<br />

U.S. Department of <strong>the</strong> Interior<br />

U.S. Geological Survey

Coord<strong>in</strong>ation among agencies and organizations is an <strong>in</strong>tegral part of <strong>the</strong> NAWQA program. We thank <strong>the</strong><br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g agencies and organizations who directly participated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> program.<br />

Federal Organizations<br />

Local Agencies<br />

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service<br />

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency<br />

Kittitas County Conservation District<br />

Lake Roosevelt Forum<br />

L<strong>in</strong>coln County Conservation District<br />

Palouse Conservation District<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Palouse-Clearwater Environmental Institute<br />

Yakama Indian Nation<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-<strong>Columbia</strong> Irrigation District<br />

Universities and State Agencies<br />

South <strong>Columbia</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong> Irrigation District<br />

Spokane County Conservation District<br />

University of Idaho<br />

Thurston County Health Department<br />

University of Wash<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton PUD Association<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton State University Cooperative Extension<br />

Idaho Department of Health & Division of Environmental <strong>Quality</strong><br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Agriculture<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Ecology<br />

Whitman County Conservation District<br />

Private Organizations<br />

Battelle-Pacific Northwest Laboratory<br />

Best Test Analytical Services<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong> Institute<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Fisheries<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> Foods, Inc.<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Health<br />

DowElanco<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Natural Resources<br />

Far West Fertilizer & Agrichemical Association<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Transportation<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Wildlife<br />

L<strong>in</strong>coln County Wheat Growers Association<br />

Northwest Food Processor Association<br />

Qualls Agricultural Labs<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton State Conservation Commission<br />

Soiltest Farm Consultants, Inc.<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Farm Bureau<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Toxics Coalition<br />

Much appreciation is extended to <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g U.S. Geological Survey employees:<br />

Martha L. Erw<strong>in</strong>, Technical editor Joseph L. Jones, Ground-water specialist<br />

Moon H. Kim, Hydrologist<br />

Brett A. Smith, O. Gary Holloway, and Jeanette F. O’Neil, Hydrologic technicians<br />

Alan L. Haggland, Computer assistant<br />

Appreciation is also extended to those <strong>in</strong>dividuals and agencies that reviewed this report:<br />

Stuart W. McKenzie, U.S. Geological Survey Karen D<strong>in</strong>icola, U.S. Geological Survey<br />

Phillip Crawford, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton State University (WSU) Coop. Extension John Holmes, Frankl<strong>in</strong> County Conservation District<br />

Scott Downey, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Ground <strong>Water</strong> Div. Cliff Carstens, L<strong>in</strong>coln County Wheat Growers Assoc.<br />

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ON THE<br />

NATIONAL WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT (NAWQA) PROGRAM:<br />

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> Study Unit contact: NAWQA Program contact:<br />

District Chief Chief, NAWQA Program<br />

U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey<br />

<strong>Water</strong> Resources Division <strong>Water</strong> Resources Division<br />

1201 Pacific Ave., Suite 600 12201 Sunrise Valley Drive, M.S. 413<br />

Tacoma WA 98402 Reston VA 20192<br />

Phone: (253) 428-3600<br />

Information on <strong>the</strong> NAWQA Program is also available on <strong>the</strong> Internet via <strong>the</strong> World Wide Web.<br />

The <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> Study Unit’s Home Page is: The NAWQA Program’s Home Page is:<br />

http://water.usgs.gov/lookup/get?wawater/ccpt/ http://water.usgs.gov/lookup/get?nawqa/<br />

Email: nawqa_ccpt_wa@usgs.gov<br />

This circular is also available on <strong>the</strong> Internet via <strong>the</strong> World Wide Web, at URL:<br />

http://water.usgs.gov/lookup/get?circ1144<br />

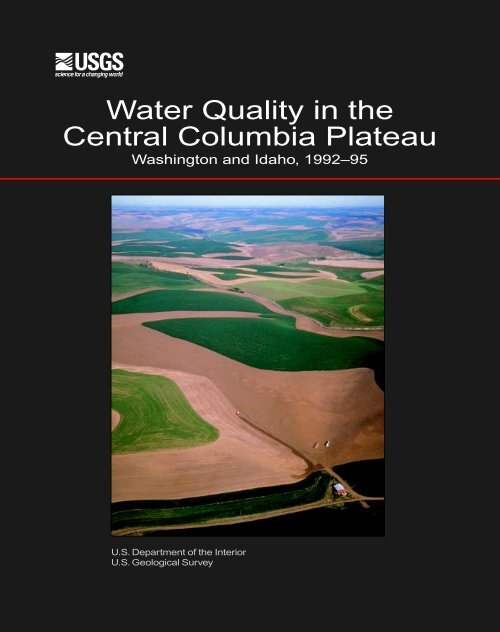

Front cover: Roll<strong>in</strong>g hills near Pullman, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton. The Palouse bas<strong>in</strong> is almost entirely cropped <strong>in</strong> wheat and o<strong>the</strong>r dry-farmed gra<strong>in</strong>s. Strip<br />

cropp<strong>in</strong>g (alternat<strong>in</strong>g bands of different crops or fallow) is a best management practice (BMP) designed to reduce soil erosion. (Photograph<br />

© by Phil Schofield. Used with permission)<br />

Back cover: Front cover photograph and a second photograph, look<strong>in</strong>g south from where I-90 crosses <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> River, show<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> mouth<br />

of Crab Creek, and irrigated circles on both <strong>the</strong> Royal Slope <strong>in</strong> front of <strong>the</strong> Saddle Mounta<strong>in</strong>s and on <strong>the</strong> Wahluke Slope beyond. (Second<br />

photograph by Dennis Cl<strong>in</strong>e, U.S. Geological Survey)

ISBN 0-607-89116-5<br />

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR<br />

BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary<br />

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY<br />

Thomas J. Casadevall, Act<strong>in</strong>g Director<br />

The use of firm, trade, and brand names <strong>in</strong> this report is for identification purposes only and<br />

does not constitute endorsement by <strong>the</strong> U.S. Government<br />

1998<br />

Free on application to <strong>the</strong><br />

U.S. Geological Survey<br />

Information Services<br />

Box 25286 Federal Center<br />

Denver, CO 80225<br />

Library of Congress Catalog<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Publications Date

<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>,<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton and Idaho, 1992–95<br />

By Alex K. Williamson, Mark D. Munn, Sarah J. Ryker,<br />

Richard J. Wagner, James C. Ebbert, and Ann M. Vanderpool<br />

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 1144<br />

A contribution of <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Water</strong>-<strong>Quality</strong> Assessment (NAWQA) Program<br />

CONTENTS<br />

National <strong>Water</strong>-<strong>Quality</strong> Assessment<br />

Program .......................................................... 1<br />

Summary of major issues and f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs ............... 2<br />

Environmental sett<strong>in</strong>g and hydrologic<br />

conditions ........................................................ 4<br />

Major issues and f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs:<br />

Nitrate <strong>in</strong> ground water..................................... 6<br />

Nitrate trends <strong>in</strong> ground water.......................... 9<br />

Pesticides and radon <strong>in</strong> ground water ............... 10<br />

Pesticides <strong>in</strong> surface water................................<br />

The <strong>in</strong>fluence of ground water on<br />

12<br />

surface-water quality..................................... 13<br />

Sediment <strong>in</strong> surface water................................. 14<br />

Nutrients <strong>in</strong> surface water................................. 16<br />

The <strong>in</strong>fluence of land use on aquatic life.......... 18<br />

<strong>Water</strong>-quality conditions <strong>in</strong> a national<br />

context ............................................................. 20<br />

Study design and data collection......................... 24<br />

Summary of compound detections<br />

and concentrations ........................................... 26<br />

References........................................................... 32<br />

Glossary .............................................................. 34<br />

Numbers <strong>in</strong> [ ] refer to References. Words <strong>in</strong> italics are def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Glossary.

NATIONAL WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT PROGRAM<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

Began <strong>in</strong> 1991<br />

Began <strong>in</strong> 1994<br />

Began <strong>in</strong> 1997<br />

Not scheduled yet<br />

Knowledge of <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong> Nation’s streams and aquifers is important because<br />

of <strong>the</strong> implications to human and aquatic health and because of <strong>the</strong> significant costs<br />

associated with decisions <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g land and water management, conservation, and<br />

regulation. In 1991, <strong>the</strong> U.S. Congress appropriated funds for <strong>the</strong> U.S. Geological<br />

Survey (<strong>USGS</strong>) to beg<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Water</strong>-<strong>Quality</strong> Assessment (NAWQA) Program<br />

to help meet <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g need for sound, scientific <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>the</strong> areal extent<br />

of <strong>the</strong> water-quality problems, how <strong>the</strong>se problems are chang<strong>in</strong>g with time, and an<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> effects of human actions and natural factors on water quality<br />

conditions.<br />

The NAWQA Program is assess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> water-quality conditions of more than 50 of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Nation’s largest river bas<strong>in</strong>s and aquifers, known as Study Units. Collectively,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se Study Units cover about one-half of <strong>the</strong> United States and <strong>in</strong>clude sources of<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water used by about 70 percent of <strong>the</strong> U.S. population. Comprehensive<br />

assessments of about one-third of <strong>the</strong> Study Units are ongo<strong>in</strong>g at a given time. Each<br />

Study Unit is scheduled to be revisited every decade to evaluate changes <strong>in</strong> waterquality<br />

conditions. NAWQA assessments rely heavily on exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation collected<br />

by <strong>the</strong> <strong>USGS</strong> and many o<strong>the</strong>r agencies as well as <strong>the</strong> use of nationally consistent<br />

study designs and methods of sampl<strong>in</strong>g and analysis. Such consistency simultaneously<br />

provides <strong>in</strong>formation about <strong>the</strong> status and trends <strong>in</strong> water-quality conditions<br />

<strong>in</strong> a particular stream or aquifer and, more importantly, provides <strong>the</strong> basis to make<br />

comparisons among watersheds and improve our understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> factors that<br />

affect water-quality conditions regionally and nationally.<br />

This report is <strong>in</strong>tended to summarize major f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs that emerged between 1992<br />

and 1995 from <strong>the</strong> water-quality assessment of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> Study<br />

Unit and to relate <strong>the</strong>se f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs to water-quality issues of regional and national concern.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>formation is primarily <strong>in</strong>tended for those who are <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> waterresource<br />

management. Indeed, this report addresses many of <strong>the</strong> concerns raised by<br />

regulators, water-utility managers, <strong>in</strong>dustry representatives, and o<strong>the</strong>r scientists, eng<strong>in</strong>eers,<br />

public officials, and members of stakeholder groups who provided advice and<br />

<strong>in</strong>put to <strong>the</strong> <strong>USGS</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g this NAWQA Study-Unit <strong>in</strong>vestigation. Yet, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>ed here may also <strong>in</strong>terest those who simply wish to know more about <strong>the</strong><br />

quality of water <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rivers and aquifers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area where <strong>the</strong>y live.<br />

Robert M. Hirsch, Chief Hydrologist<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1144 1

SUMMARY OF MAJOR ISSUES AND FINDINGS<br />

GROUND WATER: Ground water, <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> source of dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<br />

water, is substantially affected by agricultural practices.<br />

Concentrations of nitrate <strong>in</strong> many wells exceed <strong>the</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water standard (p. 6–8).<br />

• Nitrate concentrations <strong>in</strong> about 20 percent of all wells exceed <strong>the</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water standard,<br />

2 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton and Idaho, 1992–95<br />

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong><br />

study unit<br />

North-<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton <strong>Central</strong><br />

subunit<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-<br />

Pasco<br />

subunit<br />

Palouse<br />

subunit<br />

which is <strong>the</strong> U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maximum contam<strong>in</strong>ant level (MCL). The highest exceedance rates<br />

occur where fertilizer use and irrigation are greatest.<br />

• The primary source of nitrate <strong>in</strong> ground water is agricultural fertilizers. O<strong>the</strong>r sources <strong>in</strong>clude cattle feedlots, food process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

plants, septic tanks, and wastewater discharges.<br />

• Nitrate concentrations are generally highest <strong>in</strong> shallow wells <strong>in</strong> irrigated areas, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g many domestic wells and shallow<br />

public supply wells.<br />

• Nitrate concentrations <strong>in</strong> shallow wells are among <strong>the</strong> highest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nation (p. 22).<br />

Pesticides are frequently detected, although generally at concentrations below dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water criteria (p. 10–11).<br />

• Pesticides were detected <strong>in</strong> 60 percent of shallow wells and 46 percent of deeper public supply wells.<br />

• Concentrations of only three pesticides exceed <strong>the</strong> MCL or a health advisory: dieldr<strong>in</strong>, EDB, and 1,2-dichloropropane.<br />

These pesticides have been discont<strong>in</strong>ued from use, and <strong>the</strong> exceedances occur <strong>in</strong> only 2 percent of <strong>the</strong> wells.<br />

• Herbicides were detected most often, especially atraz<strong>in</strong>e and its breakdown products. However, no concentrations of an herbicide<br />

exceed MCLs or health advisories.<br />

• Shallow wells <strong>in</strong> irrigated agricultural areas of <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit have <strong>the</strong> most pesticide detections and <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

number of different pesticides detected per well. Pesticide detections also correlate with elevated nitrate concentrations.<br />

• In <strong>the</strong> Palouse subunit, none of <strong>the</strong> commonly used pesticides were detected <strong>in</strong> ground water, although 10 were detected <strong>in</strong><br />

surface water.<br />

• Sixty-four percent of public supply wells with detections of pesticides conta<strong>in</strong> more than one detectable pesticide. The<br />

human health significance of very low concentrations of several pesticides is uncerta<strong>in</strong> because dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water standards do<br />

not exist for 40 percent of <strong>the</strong> pesticides detected or for occurrences of multiple pesticides.<br />

• Pesticides were detected more frequently than <strong>the</strong> national average, with <strong>the</strong> exception of those <strong>in</strong> shallow ground water<br />

associated with dryland farm<strong>in</strong>g (p. 22).<br />

Radon, a naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g gas, is not <strong>in</strong>creased by agricultural practices. Nei<strong>the</strong>r radon nor trace elements are a<br />

major concern <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>.<br />

Is ground-water quality improv<strong>in</strong>g?<br />

Improvements from best management practices (BMPs) take decades or longer to be seen.<br />

• However, as a result of fertilizer use level<strong>in</strong>g off s<strong>in</strong>ce 1985, nitrate concentrations may be beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g to level off <strong>in</strong> some<br />

areas. In many areas, concentrations cont<strong>in</strong>ue to rise.<br />

It is difficult to determ<strong>in</strong>e trends for pesticides because <strong>the</strong>re are not enough data, but <strong>the</strong> patterns of detection may<br />

give some clues (p. 10).<br />

• The newer pesticides, which are less persistent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment than <strong>the</strong> discont<strong>in</strong>ued ones, were not detected at concentrations<br />

above MCLs or health advisories. EDB, discont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> late 1970s, was detected more frequently <strong>in</strong> deeper<br />

wells, possibly <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that it is mov<strong>in</strong>g down <strong>in</strong>to deeper ground water. This is ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dication that ground-water<br />

quality improvements take decades or longer.<br />

• Concentrations of nitrate and pesticides are generally similar <strong>in</strong> shallow ground water and <strong>in</strong> surface water at base flow,<br />

which occurs <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter. Trends <strong>in</strong> pesticides <strong>in</strong> ground water are most cost effectively monitored by sampl<strong>in</strong>g surface water<br />

at base flow, though sampl<strong>in</strong>g very shallow wells gives <strong>the</strong> most current picture of ground-water quality (p. 13).<br />

Idaho

SURFACE WATER: The health of <strong>the</strong> aquatic ecosystems is substantially affected by<br />

agricultural practices and, <strong>in</strong> a few streams, by wastewater discharges.<br />

Eutrophication, caused by high concentrations of nutrients, is degrad<strong>in</strong>g streams (p. 17, 18).<br />

• Eutrophication results <strong>in</strong> excessive plant growth, sometimes reduc<strong>in</strong>g dissolved oxygen below levels that some fish species<br />

require.<br />

• Improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> health of aquatic ecosystems may require reduc<strong>in</strong>g nitrate concentrations <strong>in</strong> ground water. At one site <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit, over 60 percent of <strong>the</strong> nitrogen comes from ground water (p. 13).<br />

Sediment erosion and runoff are degrad<strong>in</strong>g streams (p. 14–15, 19).<br />

• In most streams, sediment load<strong>in</strong>g has reduced <strong>in</strong>stream habitat needed by fish and o<strong>the</strong>r aquatic life (p. 19). Moreover,<br />

eroded soil particles carry pesticides that accumulate <strong>in</strong> streambeds and also <strong>in</strong> fish tissue.<br />

• Concentrations of some long-banned but persistent organochlor<strong>in</strong>e pesticides (such as DDT) or total PCBs exceed environmental<br />

guidel<strong>in</strong>es for streambed sediment at 22 percent of <strong>the</strong> sites sampled.<br />

• However, concentrations of trace elements are not elevated above naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g levels <strong>in</strong> soils.<br />

Riparian (streamside) habitat has been seriously reduced, and present-day agricultural practices limit natural<br />

recovery of <strong>the</strong> vegetation (p. 19).<br />

• Loss of riparian habitat causes stream temperatures to <strong>in</strong>crease and stream banks to become more unstable, and thus more<br />

likely to erode. Increased temperatures and sediment <strong>in</strong> streams can alter resident fish communities.<br />

• Graz<strong>in</strong>g practices also contribute to erosion of destabilized stream banks.<br />

Concentrations of agricultural pesticides occasionally exceed criteria for <strong>the</strong> protection of aquatic life <strong>in</strong> several<br />

streams (p. 12).<br />

• Highest concentrations and exceedances of freshwater-chronic criteria generally occur with<strong>in</strong> a month or two of pesticide<br />

application.<br />

• Most exceedances of freshwater-chronic criteria are for currently used organophosphate <strong>in</strong>secticides.<br />

• Carp <strong>in</strong> a small lake <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit showed nervous system abnormalities, possibly <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g exposure to<br />

organophosphate <strong>in</strong>secticides; long-term effects are uncerta<strong>in</strong> (p. 19).<br />

Is surface-water quality improv<strong>in</strong>g?<br />

Soil erosion is decreas<strong>in</strong>g as a result of best management practices (BMPs) (p. 14–15).<br />

• Chang<strong>in</strong>g from furrow to spr<strong>in</strong>kler irrigation is reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> loss of soil from irrigated cropland <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy- Pasco subunit.<br />

• Soil erosion from irrigated cropland and DDT concentrations <strong>in</strong> sediment and fish correlate with <strong>the</strong> percentage of furrowirrigated<br />

land, so chang<strong>in</strong>g to spr<strong>in</strong>klers also improves sediment quality.<br />

• Improved farm<strong>in</strong>g practices may have reduced soil erosion from dry-farmed cropland <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palouse subunit.<br />

Although concentrations of nutrients are commonly still <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g, at some sites <strong>the</strong>y have decreased slightly or begun<br />

to level off (p. 9, 17).<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1144 3

ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING AND HYDROLOGIC CONDITIONS<br />

Rich grasslands and forested canyons <strong>in</strong>spired 19th-century cattle ranchers to make <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

home. As overgraz<strong>in</strong>g devalued <strong>the</strong> land for ranch<strong>in</strong>g, farm<strong>in</strong>g became more important. Today it is an area of national agricultural<br />

importance and home to about 300,000 people. The region is one of <strong>the</strong> Nation’s top two producers of potatoes and<br />

wheat, is a significant producer of apples and many o<strong>the</strong>r crops, and supports much rangeland graz<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The Study Unit was divided <strong>in</strong>to three subunits on <strong>the</strong> basis of hydrologic and geologic differences affect<strong>in</strong>g land and water<br />

use (see p. 24–25). Thick loess and moderate precipitation allow for dryland farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palouse subunit, while <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

Bas<strong>in</strong> Irrigation Project has made <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit also productive for farm<strong>in</strong>g. The North-<strong>Central</strong> subunit supports<br />

rangeland graz<strong>in</strong>g and, where conditions allow, irrigated and dryland farm<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

48<br />

120<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> River<br />

DOUGLAS<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy<br />

Crab Creek<br />

Beverly<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco<br />

subunit<br />

(<strong>Columbia</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong><br />

Irrigation Project)<br />

GRANT<br />

Moses<br />

Lake<br />

46 30’<br />

Banks<br />

Lake<br />

Coulee<br />

City<br />

Potholes<br />

Reservoir<br />

O<strong>the</strong>llo<br />

FRANKLIN<br />

Pasco<br />

North-<strong>Central</strong><br />

subunit<br />

LINCOLN<br />

ADAMS<br />

Snake River<br />

Ritzville<br />

Figure 1. Most of <strong>the</strong> land <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> is used for agriculture.<br />

4 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton and Idaho, 1992–95<br />

Cow Creek<br />

118<br />

Hooper<br />

0 20 40 mi<br />

0 20 40 km<br />

Table 1. Summary of subunit characteristics [mi 2 , square mile; %, percent]<br />

Total cropland a<br />

Major crops b<br />

(approximate percentage<br />

of total cropland)<br />

Hydrology<br />

Major po<strong>in</strong>t and<br />

localized nonpo<strong>in</strong>t<br />

sources of pollutants<br />

Surficial geology<br />

Topography<br />

<strong>Water</strong> table change,<br />

1950 to present<br />

a b [1]; [2, 3]<br />

SPOKANE<br />

Rock Lake<br />

Palouse River<br />

WHITMAN<br />

Pullman<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

Nonirrigated (dryland)<br />

agriculture<br />

Surface-water<br />

irrigated agriculture<br />

Ground-water<br />

irrigated agriculture<br />

Barren or rangeland<br />

Forest<br />

Subunit boundary<br />

County boundary<br />

State boundary<br />

Palouse<br />

Moscow<br />

WASHINGTON<br />

IDAHO<br />

Palouse<br />

subunit<br />

LATAH<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit (2,500 mi2 ) North-<strong>Central</strong> subunit (8,100 mi2 ) Palouse subunit (2,500 mi2 )<br />

896,000 acres<br />

alfalfa (30%) wheat (20%)<br />

3,210,000 acres<br />

1,260,000 acres<br />

field crops (15%) corn (11%)<br />

cereal gra<strong>in</strong>s (wheat, barley, oats) cereal gra<strong>in</strong>s (78%)<br />

potatoes (10%) orchard (7%)<br />

(93%)<br />

field crops (19%)<br />

Controlled dur<strong>in</strong>g irrigation season (Mar.–Oct.) Intermittent streams with few Perennial streams <strong>in</strong> larger<br />

Nearly all surface water is canals and agricultural disconnected perennial stream bas<strong>in</strong>s<br />

dra<strong>in</strong>s<br />

Storm runoff is rare<br />

segments<br />

Feedlots, pesticide handl<strong>in</strong>g areas<br />

Some feedlots Wastewater-treatment effluent<br />

Land-applied food-process<strong>in</strong>g effluent<br />

Land-applied wastewater-treatment effluent<br />

discharged to streams<br />

Varied thickness of sediments over basalt 0-20 feet of loess over basalt 5-100 feet of loess over basalt<br />

Nearly flat bas<strong>in</strong>s between bluffs<br />

Channeled scablands<br />

Roll<strong>in</strong>g hills<br />

Rise of 50 to 500 feet Decl<strong>in</strong>e of more than 150 feet <strong>in</strong><br />

some locations<br />

Slightly decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g

The climate is arid to<br />

semiarid<br />

The arid to semiarid climate is evident<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> hydrology. Only <strong>the</strong> Palouse<br />

subunit receives enough ra<strong>in</strong>fall<br />

(fig. 2) to support perennial streams<br />

that have high flows <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wetter w<strong>in</strong>ter<br />

months and low base flows <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

dry, hot summer months (fig. 3).<br />

Before <strong>in</strong>creased irrigation, <strong>the</strong><br />

rema<strong>in</strong>der of <strong>the</strong> Study Unit mostly<br />

supported <strong>in</strong>termittent streams that<br />

only had substantial streamflows follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

storms; this is still true for most<br />

of <strong>the</strong> North-<strong>Central</strong> subunit.<br />

Streamflow, <strong>in</strong> cubic feet per second<br />

Streamflow, <strong>in</strong> cubic feet per second<br />

8,000<br />

7,000<br />

6,000<br />

5,000<br />

4,000<br />

3,000<br />

2,000<br />

1,000<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

0<br />

1995 (wet)<br />

Palouse River at Hooper<br />

Crab Creek at Beverly<br />

1993<br />

Interquartile range of daily<br />

streamflow, water years 1961-64<br />

O N D J F M A M J J A S<br />

<strong>Water</strong> year (Oct. - Sept.)<br />

Interquartile range (middle<br />

50 percent of <strong>the</strong> values)<br />

of daily streamflow, water<br />

years 1952-95<br />

O N D J F M A M J J A S<br />

<strong>Water</strong> year (Oct. - Sept.)<br />

1994<br />

1993<br />

1994 (dry)<br />

Figure 3. Conditions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palouse subunit were<br />

typical dur<strong>in</strong>g 1993–95, <strong>the</strong> sampl<strong>in</strong>g period, with<br />

variable streamflows <strong>in</strong> dry, average, and wet years.<br />

1995<br />

Interquartile range (middle<br />

50 percent of <strong>the</strong> values)<br />

of daily streamflow, water<br />

years 1970-95<br />

Figure 4. In <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit, irrigation has<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased and stabilized streamflows throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

year.<br />

48˚<br />

11<br />

46˚<br />

30’<br />

120˚<br />

7<br />

8<br />

8<br />

8<br />

Irrigation has greatly altered <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit<br />

Irrigation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit <strong>in</strong>creased significantly<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g 1955–75 as <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong> Irrigation Project made<br />

more water available. <strong>Water</strong> diverted from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> River,<br />

conveyed through irrigation canals, and applied to agricultural<br />

lands has raised <strong>the</strong> water table tens to hundreds of feet, creat<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g base flow to many of <strong>the</strong> streams and wasteways. The<br />

result is an overall annual <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> streamflow, controlled mostly<br />

by irrigation, with base flow <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter and high flows <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

summer (fig. 4).<br />

Most water withdrawals are for irrigation<br />

About 94 percent of comb<strong>in</strong>ed ground- and surface-water withdrawals<br />

are for irrigation [5]. Eighty-four percent of public and<br />

domestic supplies comes from ground water (fig. 5).<br />

<strong>Water</strong> withdrawals,<br />

<strong>in</strong> millions of gallons per day<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Figure 2. Average annual precipitation is highest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palouse subunit;<br />

average monthly figures for Pullman, Wash., show that precipitation mostly<br />

occurs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter (years of record 1956–77). Modified from [4].<br />

3,000<br />

2,000<br />

1,000<br />

11<br />

0<br />

12<br />

TOTAL<br />

118˚<br />

13 14<br />

15<br />

Irrigation<br />

16<br />

18<br />

20<br />

18<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

25<br />

0 40 mi<br />

0 40 km<br />

WA<br />

ID<br />

Public<br />

supply<br />

(234)<br />

Domestic<br />

supply<br />

Food<br />

process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

Ground<br />

water<br />

Surface<br />

water<br />

(234) Population<br />

served, <strong>in</strong><br />

thousands<br />

Figure 5. Most of <strong>the</strong> water <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong><br />

is used for irrigation. Ground water is <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> source of<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water (1990 data shown; graphs have different<br />

vertical scales) [5].<br />

8<br />

Precipitation,<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ches<br />

(58)<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

L<strong>in</strong>e of equal average<br />

annual precipitation,<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ches. Contour<br />

<strong>in</strong>terval is variable<br />

Subunit boundary<br />

State boundary<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

Pullman<br />

0<br />

JFMAMJJASOND<br />

Month<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1144 5

MAJOR ISSUES AND FINDINGS -<br />

NITRATE IN GROUND WATER<br />

Nitrate concentrations <strong>in</strong><br />

many dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water<br />

wells exceed <strong>the</strong><br />

maximum contam<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

level (MCL).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>,<br />

84 percent of dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water comes<br />

from ground water. Both public<br />

supply and domestic water systems<br />

depend largely on ground water [5,<br />

6] (fig. 5). Current nitrate data are<br />

generally available for public supply<br />

wells, which must be sampled<br />

regularly. Domestic wells, however,<br />

are generally sampled only for<br />

special studies. About 20 percent of<br />

wells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Study Unit exceed <strong>the</strong><br />

MCL for nitrate <strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water<br />

[1, 7]; <strong>the</strong> MCL is set by <strong>the</strong> U.S.<br />

Environmental Protection Agency<br />

at 10 milligrams per liter (mg/L)<br />

[8]. Reduc<strong>in</strong>g nitrate <strong>in</strong> ground<br />

water has been <strong>the</strong> focus of cooperative<br />

efforts between Federal, State,<br />

and local agencies.<br />

Nitrate concentration has been<br />

suggested as an <strong>in</strong>dicator of overall<br />

ground-water quality [9, 10], and<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water with high nitrate<br />

concentrations is a potential health<br />

risk, particularly for <strong>in</strong>fants [7, 8,<br />

11].<br />

The Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit has<br />

<strong>the</strong> highest percentage of wells<br />

exceed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> MCL<br />

The <strong>Columbia</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong> Irrigation<br />

Project br<strong>in</strong>gs more than 2,500,000<br />

acre-feet (800 billion gallons) of<br />

water per year from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

River to <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit,<br />

enabl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tensive irrigated agriculture.<br />

In much of <strong>the</strong> North-<strong>Central</strong><br />

subunit, deep ground water is <strong>the</strong><br />

only source of water. Most of this<br />

subunit’s high nitrate concentrations<br />

are <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> shallower wells border<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit.<br />

The Palouse subunit, dom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

by nonirrigated agriculture, has<br />

generally lower nitrate concentrations<br />

than <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> Study Unit.<br />

Table 2. Percentage of dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water wells sampled <strong>in</strong> 1985–96 with nitrate<br />

concentrations a exceed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maximum<br />

contam<strong>in</strong>ant level of 10 milligrams per liter [--, <strong>in</strong>sufficient data; %, percent]<br />

Figure 6. Most public supply wells [13] and domestic wells that exceed <strong>the</strong> maximum<br />

contam<strong>in</strong>ant level (MCL) for nitrate are <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit. (Wells were<br />

sampled from 1985 to 1996; for wells sampled more than once, <strong>the</strong> most recent value<br />

was used.)<br />

6 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton and Idaho, 1992–95<br />

48<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> River<br />

120<br />

DOUGLAS<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy Moses<br />

Lake<br />

GRANT<br />

CrabCreek<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco<br />

subunit<br />

46 30’<br />

Banks<br />

Lake<br />

Potholes<br />

Reservoir<br />

FRANKLIN<br />

Pasco<br />

Class A public<br />

supply<br />

wells b<br />

LINCOLN<br />

Snake River<br />

North-<strong>Central</strong><br />

subunit<br />

ADAMS<br />

CowCreek<br />

118<br />

Class B public<br />

supply<br />

wells c<br />

a For wells sampled more than once, <strong>the</strong> most recent value was used. b 411 public water systems with at<br />

least 15 hook-ups; average depth 270 feet [9]. c 270 public water systems with less than 15 hook-ups; average<br />

depth 210 feet. d 67 domestic wells sampled for <strong>the</strong> NAWQA Land Use Study component (p. 24); average<br />

depth 140 feet [3]. e Percentages were not calculated for counties that fall partly outside <strong>the</strong> study area.<br />

f Most wells are deep, averag<strong>in</strong>g 500 feet (see Moses Lake area, fig. 6).<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

Nitrate concentration, <strong>in</strong> milligrams per liter<br />

(mg/L) as nitrogen<br />

0 - 2.5 mg/L Naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g<br />

[12]<br />

2.6 - 5.0 mg/L<br />

Elevated<br />

5.1 - 9.9 mg/L<br />

Greater than or At or above <strong>the</strong> MCL<br />

equal to 10.0 mg/L<br />

SPOKANE<br />

Rock<br />

Lake<br />

WHITMAN<br />

PalouseRiver<br />

Pullman<br />

0 20 40 mi<br />

0 20 40 km<br />

Shallow<br />

domestic<br />

wells d<br />

County e Adams 3% 25% - -<br />

Douglas 7% - - - -<br />

Frankl<strong>in</strong> 28% 29% 33%<br />

Grant 1% f 3% 35%<br />

Whitman 7% 4% 6%<br />

Subunit Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco 9% 15% 35%<br />

North-<strong>Central</strong> 3% 5% - -<br />

Palouse 7% 5% 5%<br />

Study Unit 6% 12% - -<br />

Palouse<br />

subunit<br />

LATAH<br />

NEZ PERCE

Intensive application of<br />

fertilizers and irrigation<br />

water causes high nitrate<br />

concentrations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit<br />

Syn<strong>the</strong>tic fertilizers became widely<br />

available after World War II. Fertilizers<br />

are <strong>the</strong> source of 84 percent of<br />

nitrate <strong>in</strong>puts to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

<strong>Plateau</strong> [16]. O<strong>the</strong>r sources of nitrate<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude cattle feedlots, food process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

plants, septic tanks, and treated wastewater;<br />

<strong>the</strong>se are local and thus less<br />

important sources <strong>in</strong> most of <strong>the</strong> Study<br />

Unit.<br />

Agricultural acreage cont<strong>in</strong>ues to<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateau, but nationally<br />

recommended application rates for fertilizer<br />

have been lowered <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> last<br />

Nitrogen fertilizer sales,<br />

<strong>in</strong> millions of tons per year<br />

Irrigation water, <strong>in</strong><br />

millions of acre-feet<br />

12<br />

10<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

Nitrogen<br />

fertilizer<br />

0<br />

1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995<br />

Figure 7. Sales of nitrogen fertilizer <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> United States have leveled off [14,<br />

15]. Graph modified from [12].<br />

Irrigation<br />

water<br />

0<br />

1945 1955 1965 1975 1985<br />

1995<br />

Figure 8. The amount of irrigation<br />

water diverted from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> River<br />

has steadily <strong>in</strong>creased [16].<br />

few years. As a result, fertilizer sales<br />

(fig. 7) and application have leveled<br />

off [12]. Irrigation, however, cont<strong>in</strong>ues<br />

to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateau [fig. 8].<br />

Two primary factors contribute to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit’s high<br />

nitrate concentrations: high rates of<br />

fertilizer application [fig. 9] and irrigation<br />

water. N<strong>in</strong>ety-four percent of all<br />

<strong>the</strong> water used <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateau supports<br />

agricultural irrigation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> arid<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit [5]. This extensive<br />

irrigation has greatly <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

rates of recharge (fig. 10), which is<br />

water mov<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> land surface to<br />

ground water. Recharge, especially at<br />

higher rates, moves nitrate <strong>in</strong>to shallow<br />

ground water.<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> River<br />

Wenatchee<br />

140<br />

lb/acre<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco<br />

subunit<br />

Pasco<br />

50<br />

lb/acre<br />

Snake River<br />

Spokane<br />

55<br />

lb/acre<br />

Pullman<br />

Figure 9. Annual application rates of<br />

nitrogen fertilizer are highest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit (rates are <strong>in</strong><br />

pounds per acre (lb/acre)), (1991 data<br />

shown) [16].<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> River<br />

Wenatchee<br />

12<br />

<strong>in</strong>/yr<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong><br />

Irrigation Project<br />

area<br />

Pasco<br />

2 <strong>in</strong>/yr<br />

Snake River<br />

4 <strong>in</strong>/yr<br />

Spokane<br />

Pullman<br />

Figure 10. Average rates of recharge<br />

are highest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco<br />

subunit (rates are <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ches per year<br />

(<strong>in</strong>/yr)) [17].<br />

Trends <strong>in</strong> nitrate<br />

concentrations vary<br />

across <strong>the</strong> Study Unit<br />

Nitrate concentrations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong><br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>’s ground water have<br />

generally <strong>in</strong>creased s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1950s.<br />

Although fertilizer application leveled<br />

off <strong>in</strong> about 1985, it is too early to be<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> of any correspond<strong>in</strong>g level<strong>in</strong>g<br />

off or decrease <strong>in</strong> nitrate concentrations<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> regional ground-water system.<br />

Individual wells may show trends<br />

that reflect only local conditions. For<br />

example, at R<strong>in</strong>gold Spr<strong>in</strong>gs, one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> largest spr<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Study Unit,<br />

nitrate concentrations may have leveled<br />

off. However, <strong>the</strong> improvement is<br />

probably not as dramatic as is suggested<br />

by <strong>the</strong> decrease shown <strong>in</strong><br />

figure 11.<br />

Across <strong>the</strong> plateau, nitrate concentrations<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> most<br />

areas. Examples of vary<strong>in</strong>g nitrate<br />

trends <strong>in</strong> ground- and surface-water<br />

systems are discussed on page 9.<br />

Nitrate as nitrogen,<br />

<strong>in</strong> milligrams per liter<br />

10<br />

9<br />

Nitrate<br />

concentration<br />

MCL<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995<br />

Figure 11. Nitrate concentrations may<br />

have leveled off at R<strong>in</strong>gold Spr<strong>in</strong>gs, a<br />

large spr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Study Unit (site A,<br />

fig. 14), from 1957 to 1994 [18].<br />

However, data are limited and <strong>the</strong><br />

peak concentration <strong>in</strong> 1986 may have<br />

been unusual.<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1144 7

Irrigation <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>the</strong> variability<br />

of nitrate concentrations<br />

Trends <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual wells may not<br />

reliably represent trends for a large<br />

area. In <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit,<br />

samples from spr<strong>in</strong>gs and surfacewater<br />

sites can give fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to<br />

trends and variability of nitrate <strong>in</strong><br />

ground water.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit, nitrate<br />

concentrations <strong>in</strong> ground water can be<br />

much higher dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> irrigation<br />

season (fig. 12). In some parts of <strong>the</strong><br />

subunit, however, low-nitrate water<br />

leak<strong>in</strong>g from irrigation canals may<br />

dilute nitrate <strong>in</strong> ground water, so that<br />

summer concentrations are close to<br />

naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g levels (2–3 mg/L)<br />

[12].<br />

Nitrate as nitrogen,<br />

<strong>in</strong> milligrams per liter<br />

22<br />

20<br />

18<br />

16<br />

14<br />

July<br />

1986<br />

summer w<strong>in</strong>ter<br />

Nitrate<br />

concentration<br />

Jan. July Jan. June<br />

1987<br />

1988<br />

Date of sample<br />

Figure 12. In a well <strong>in</strong> western Frankl<strong>in</strong><br />

County (site B, fig. 14), nitrate<br />

concentrations are higher dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

peak irrigation season (Mar.–Oct.)<br />

[18].<br />

The average nitrate concentration <strong>in</strong><br />

regional shallow ground water is<br />

6 mg/L or more. In fresh water<br />

diverted from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> River for<br />

irrigation, nitrate concentrations are<br />

1 mg/L or lower. As shown <strong>in</strong><br />

figure 13, some wells close to canals<br />

have below-average nitrate concentrations<br />

due to dilution by water leak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

from canals [18].<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

Canal lateral<br />

Well<br />

0.5 Nitrate concentration, <strong>in</strong><br />

milligrams per liter as nitrogen<br />

Figure 13. In an irrigated area <strong>in</strong><br />

western Frankl<strong>in</strong> County (area C,<br />

fig. 14), PE 59.4 Lateral has a nitrate<br />

concentration of 1.3 milligrams per<br />

liter. Most wells close to <strong>the</strong> canal<br />

have lower nitrate concentrations [18].<br />

8 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton and Idaho, 1992–95<br />

1.3<br />

0.5<br />

PE 59.4D<br />

PE 59.4<br />

20<br />

13<br />

16<br />

14<br />

2.4<br />

2.4<br />

0.6<br />

6.8<br />

Deeper ground water, which is far<strong>the</strong>r<br />

from sources of nitrate applied on<br />

<strong>the</strong> land surface, is less susceptible to<br />

contam<strong>in</strong>ation. Also, when irrigation<br />

raises <strong>the</strong> water table significantly, as<br />

has occurred <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit,<br />

recently recharged ground water<br />

flows rapidly to surface waters <strong>in</strong>stead<br />

of to deeper ground water. This prevents<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> nitrate present <strong>in</strong><br />

recently recharged ground water from<br />

mov<strong>in</strong>g to deeper ground water.<br />

Figure 15 shows that nitrate concentrations<br />

are generally lower at greater<br />

depths. Many public supply wells are<br />

relatively deep, so have lower nitrate<br />

concentrations and exceed <strong>the</strong> MCL<br />

less frequently than do <strong>the</strong> shallower<br />

domestic wells (table 2).<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> River<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

Irrigated areas<br />

<strong>Water</strong>ways<br />

A R<strong>in</strong>gold Spr<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

B Well, fig. 12<br />

C Area, fig. 13<br />

D EL68D Wasteway<br />

E Frenchman Hills Wasteway<br />

F Crab Creek at Beverly<br />

G Crab Creek Lateral<br />

0<br />

0<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy<br />

F<br />

20<br />

20<br />

E G<br />

40 km<br />

Moses<br />

Lake<br />

C<br />

B<br />

Pasco<br />

40 mi<br />

Figure 14. Sites <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco<br />

subunit (also <strong>the</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> Bas<strong>in</strong><br />

Irrigation Project area) used to describe<br />

trends <strong>in</strong> nitrate concentrations.<br />

Nitrate as nitrogen,<br />

<strong>in</strong> milligrams per liter<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

>30<br />

0<br />

0 250 500 750 1,000 1,250 1,500<br />

Depth to sample, <strong>in</strong> feet<br />

Figure 15. Nitrate concentrations are<br />

lower at greater depths; however, <strong>in</strong><br />

irrigated areas (see fig. 14) some deep<br />

wells have elevated nitrate<br />

concentrations.<br />

A<br />

D

Sampl<strong>in</strong>g surface water at<br />

base flow is a cost-effective<br />

way to monitor trends <strong>in</strong><br />

ground-water quality<br />

Nitrate concentrations vary considerably<br />

<strong>in</strong> wells, requir<strong>in</strong>g many samples<br />

to determ<strong>in</strong>e trends. However, <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit many irrigation<br />

wasteways and o<strong>the</strong>r surface dra<strong>in</strong>s<br />

receive large contributions from<br />

ground-water discharge. For example,<br />

about 60 percent of total nitrogen discharged<br />

annually by EL68D Wasteway<br />

(site D, fig. 14) comes from groundwater<br />

discharges to <strong>the</strong> wasteway.<br />

From November to February, irrigation<br />

water is not delivered and storms large<br />

enough to produce runoff are rare. Dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

this time, streamflow is low and<br />

ground water is <strong>the</strong> predom<strong>in</strong>ant source<br />

of nitrate <strong>in</strong> surface water conveyed by<br />

wasteways (fig. 16). Therefore, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit, samples of surface<br />

water dur<strong>in</strong>g w<strong>in</strong>ter can be used to<br />

monitor nitrate trends <strong>in</strong> ground water<br />

for a large area. Base-flow surfacewater<br />

sampl<strong>in</strong>g can also be used to<br />

track occurrence and trends <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

dissolved constituents <strong>in</strong> ground water,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pesticides such as atraz<strong>in</strong>e<br />

(p. 13).<br />

Nitrate as nitrogen,<br />

<strong>in</strong> milligrams per liter<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Nitrate<br />

concentration<br />

Streamflow<br />

O N D J F M A M J J A S<br />

1993 1994<br />

400<br />

200<br />

Figure 16. Nitrate concentrations at<br />

EL68D Wasteway (site D, fig. 14) are<br />

highest dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter when <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong><br />

source is ground-water discharge and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is little dilution by canals or return<br />

flows [2].<br />

0<br />

Daily average streamflow,<br />

<strong>in</strong> cubic feet per second<br />

Base-flow sampl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Palouse subunit<br />

streams is less <strong>in</strong>dicative of<br />

ground water for several reasons. Base<br />

flow <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palouse subunit occurs dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> summer when plant growth is<br />

high; uptake of nitrogen by aquatic<br />

plants can greatly decrease nitrate concentrations<br />

<strong>in</strong> surface water. In addition,<br />

a substantial percentage of<br />

Palouse River flow <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> summer is<br />

high-nitrate discharge from wastewater-treatment<br />

plants.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit, nitrate<br />

concentrations are generally<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g . . .<br />

In most parts of <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco<br />

subunit, base-flow concentrations of<br />

nitrate <strong>in</strong> wasteways and o<strong>the</strong>r surface<br />

dra<strong>in</strong>s have <strong>in</strong>creased s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1960s<br />

— <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> nitrate<br />

concentrations <strong>in</strong> ground water. Best<br />

management practices (BMPs) <strong>in</strong> use<br />

<strong>in</strong> parts of <strong>the</strong> subunit may <strong>in</strong> time<br />

decrease <strong>the</strong>se concentrations. However,<br />

changes <strong>in</strong> ground-water quality<br />

may not be apparent for decades or<br />

longer.<br />

. . . but trends vary.<br />

In Frenchman Hills Wasteway,<br />

base-flow nitrate concentrations dou-<br />

Nitrate as nitrogen,<br />

<strong>in</strong> milligrams per liter<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

Frenchman Hills<br />

Wasteway<br />

(E)<br />

bled from about 3 to about 6 mg/L<br />

between 1966 and 1990 and appear<br />

still to be <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g (fig. 17). Ground<br />

water is <strong>the</strong> source of nearly 100 percent<br />

of base flow <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wasteway, so<br />

nitrate concentrations <strong>in</strong> nearby<br />

ground water have likely followed <strong>the</strong><br />

same trend.<br />

Base-flow nitrate concentrations are<br />

still <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Crab Creek at Beverly,<br />

but <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease has slowed s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

1980. This trend is similar to trends<br />

that occurred <strong>in</strong> fertilizer sales (fig. 7)<br />

and irrigation (fig. 8) <strong>in</strong> much of <strong>the</strong><br />

dra<strong>in</strong>age bas<strong>in</strong>. In addition, concentrations<br />

may be level<strong>in</strong>g off at this site<br />

because of contributions from <strong>the</strong> Crab<br />

Creek Lateral subbas<strong>in</strong>, where concentrations<br />

are decreas<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

In Crab Creek Lateral, base-flow<br />

concentrations of nitrate decreased<br />

from about 8 mg/L <strong>in</strong> 1966 to about<br />

6 mg/L <strong>in</strong> 1991. This decrease may be<br />

partially expla<strong>in</strong>ed by chang<strong>in</strong>g farm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

practices. For example, although<br />

<strong>the</strong> total amount of irrigated cropland<br />

dra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to Crab Creek Lateral has not<br />

decreased, from 1974 to 1990 <strong>the</strong> proportion<br />

of this land used for orchards<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased from 9 to 29 percent.<br />

Orchards require less applied nitrogen<br />

than do many of <strong>the</strong> row crops that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y replaced [16].<br />

Crab Creek Lateral (G)<br />

MAJOR ISSUES AND FINDINGS -<br />

NITRATE TRENDS IN GROUND WATER<br />

Crab Creek<br />

at Beverly<br />

(F)<br />

0<br />

1955 1965 1975 1985 1995<br />

Figure 17. Three sites <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit show vary<strong>in</strong>g<br />

trends <strong>in</strong> nitrate concentrations at base flow (Nov.-Feb.) from 1960–91.<br />

In Frenchman Hills Wasteway (site E, fig. 14), concentrations doubled.<br />

At Crab Creek at Beverly (site F), <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease has slowed s<strong>in</strong>ce 1980.<br />

In Crab Creek Lateral (site G), <strong>the</strong>re has been a decrease.<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1144 9

MAJOR ISSUES AND FINDINGS -<br />

PESTICIDES AND RADON IN GROUND WATER<br />

Samples from 255 wells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong><br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> were analyzed<br />

for 145 pesticides and volatile organic<br />

compounds (figs. 18, 20). Volatile<br />

organic compounds (VOCs) are used<br />

as solvents or metal degreasers and as<br />

pesticides (as <strong>in</strong>ert <strong>in</strong>gredients or<br />

active <strong>in</strong>gredients to kill nematodes,<br />

<strong>in</strong>sects, bacteria, or rodents). There<br />

were 24 pesticides and 15 VOCs<br />

detected; concentrations were mostly<br />

well below dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water standards,<br />

rang<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> method detection<br />

limit (as low as 0.001 microgram per<br />

liter) to a maximum of 7.3 micrograms<br />

per liter for 1,2-dichloropropane (see<br />

p. 26). The significance of such low<br />

concentrations <strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water is not<br />

clear; and <strong>in</strong> addition, no dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<br />

water standards or guidel<strong>in</strong>es have<br />

been established for 40 percent of <strong>the</strong><br />

pesticides or VOCs analyzed. In <strong>the</strong><br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit, four of <strong>the</strong><br />

commonly used pesticides (herbicides<br />

or <strong>in</strong>secticides) were detected <strong>in</strong><br />

ground water [19, 20]. In <strong>the</strong> Palouse<br />

subunit, none of <strong>the</strong> commonly used<br />

pesticides were detected <strong>in</strong> ground<br />

water [21].<br />

Only discont<strong>in</strong>ued<br />

compounds exceed<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water standards<br />

Only concentrations of 1,2-dichloropropane<br />

<strong>in</strong> one well and 1,2-dibromoethane<br />

(EDB) <strong>in</strong> two wells exceed<br />

<strong>the</strong> MCL. Both of <strong>the</strong>se compounds<br />

are VOCs used as soil fumigants that<br />

were phased out <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> late 1970s and<br />

1980s, respectively. Herbicides,<br />

though applied <strong>in</strong> greater amounts and<br />

detected more frequently than o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

types of pesticides, were not detected<br />

at concentrations that exceed MCLs.<br />

Most of <strong>the</strong> newer pesticides break<br />

down more rapidly and thus are less<br />

persistent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment than <strong>the</strong><br />

discont<strong>in</strong>ued ones; <strong>the</strong>y were not<br />

detected at concentrations above<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water standards or guidel<strong>in</strong>es<br />

[19, 20, 45].<br />

Beverly<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco<br />

subunit<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>cy<br />

DOUGLAS<br />

GRANT<br />

FRANKLIN<br />

North-<strong>Central</strong><br />

subunit<br />

LINCOLN<br />

ADAMS<br />

Figure 18. Locations of wells sampled for pesticides and volatile organic<br />

compounds <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>.<br />

10 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong>, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton and Idaho, 1992–95<br />

48<br />

120<br />

46 30’<br />

Pasco<br />

Most dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water is from<br />

deeper wells, which are<br />

somewhat less susceptible<br />

to contam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

Shallower wells have a greater number<br />

and percentage of pesticide detections<br />

[44]. Most people <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Central</strong><br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>Plateau</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k water from<br />

public supply wells (fig. 5), which are<br />

generally deeper than domestic wells<br />

(and deeper than this study’s monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

wells), and <strong>the</strong>refore conta<strong>in</strong> water<br />

that is less susceptible to contam<strong>in</strong>ation.<br />

However, similar pesticides at<br />

similar concentrations have been<br />

detected <strong>in</strong> public supply wells, shallow<br />

domestic wells, and very shallow<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g wells (fig. 20), <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that some contam<strong>in</strong>ation does reach<br />

deeper wells. This could be due to<br />

faulty well construction, high pumpage<br />

rates, or local ground-water pathways<br />

(relatively common <strong>in</strong> fractured basalt<br />

aquifers) that allow water to move<br />

quickly to greater depths.<br />

Samples from five public supply<br />

wells conta<strong>in</strong>ed only p,p′-DDE, a<br />

breakdown product of DDT, which<br />

was discont<strong>in</strong>ued for sale <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

United States <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 1970s. More<br />

modern pesticides were not detected,<br />

suggest<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>se deeper wells are<br />

Ritzville<br />

118<br />

Hooper<br />

0 20 40 mi<br />

0 20 40 km<br />

EXPLANATION<br />

Without With<br />

detection detection<br />

Monitor<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

domestic well<br />

Public supply well<br />

Subunit boundary<br />

SPOKANE<br />

County boundary<br />

WHITMAN<br />

Pullman<br />

Moscow<br />

Palouse<br />

subunit<br />

probably withdraw<strong>in</strong>g older ground<br />

water that predates <strong>the</strong> use of newer<br />

pesticides.<br />

Low concentrations of pesticides<br />

and VOCs were detected <strong>in</strong> 60 percent<br />

of samples from 117 shallow domestic<br />

and monitor<strong>in</strong>g wells and <strong>in</strong> 46 percent<br />

of samples from 138 deeper public supply<br />

wells. Modern pesticides may get<br />

to shallow ground water before <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have had time to break down; <strong>the</strong>refore,<br />

shallow wells tend to have a<br />

higher rate of detections. Thirty-one<br />

pesticides and VOCs were detected <strong>in</strong><br />

samples from shallow domestic and<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g wells, whereas 18 pesticides<br />

and VOCs were detected <strong>in</strong> samples<br />

from public supply wells.<br />

Percentage of wells<br />

with pesticide detections<br />

100<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

0-25<br />

Percentage<br />

Number<br />

25-50<br />

50-100<br />

100-200<br />

>200<br />

Well depth, <strong>in</strong> feet<br />

Figure 19. Shallow wells have a<br />

greater number and percentage of<br />

pesticide detections.<br />

4<br />

Average number of pesticide<br />

detections per well<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0

Younger ground water<br />

Public supply<br />

well<br />

Older ground water<br />

Monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

well<br />

Irrigation canal<br />

Multiple pesticides were detected <strong>in</strong><br />

some wells, especially shallow wells<br />

Of samples with detections, 66 percent<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>ed more than one pesticide.<br />

Generally, <strong>the</strong> highest frequency<br />

of multiple detections occurred <strong>in</strong> samples<br />

from very shallow monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

wells (fig. 21). Current dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<br />

water standards or guidel<strong>in</strong>es are<br />

only for <strong>in</strong>dividual compounds; no<br />

standards or guidel<strong>in</strong>es have been<br />

established for multiple pesticides <strong>in</strong><br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water. Health effects of<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ations of pesticides <strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<br />

water are not clearly understood.<br />

Pesticides were frequently detected<br />

<strong>in</strong> wells with elevated nitrate<br />

Many chemicals, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g nitrate<br />

and pesticides, can leach through <strong>the</strong><br />

soil to ground water. Pesticides are<br />

present <strong>in</strong> more than one-half of wells<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateau that conta<strong>in</strong> elevated<br />

nitrate concentrations (above <strong>the</strong> “natural”<br />

or background level of 2-3 mg/L<br />

[12]). Indeed, <strong>the</strong> higher <strong>the</strong> nitrate<br />

concentration, <strong>the</strong> greater <strong>the</strong> percentage<br />

of wells with pesticides (fig. 22).<br />

Because of this consistent correlation,<br />

sampl<strong>in</strong>g for nitrate may be cost effective<br />

for identify<strong>in</strong>g wells that may be<br />

at risk of pesticide contam<strong>in</strong>ation.<br />

Nitrate test<strong>in</strong>g is far less expensive<br />

than pesticide test<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>the</strong> latter<br />

could <strong>the</strong>n be targeted more carefully.<br />

Percentage of wells<br />

with pesticide detections<br />

Percentage of well type<br />

100<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Domestic<br />

well<br />

0-2.5<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>kler irrigation fields<br />

Wasteway / dra<strong>in</strong><br />

2.5-5<br />

5-7.5<br />

7.5-10<br />

>10<br />

Nitrate concentration, <strong>in</strong> milligrams per liter<br />

Figure 22. Pesticide detections<br />

correlate with nitrate concentrations.<br />

<strong>Water</strong> table<br />

Figure 20. Idealized cross section of groundwater<br />

system <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>cy-Pasco subunit.<br />

Three types of wells were sampled for<br />

pesticides and VOCs: very shallow monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

wells <strong>in</strong>stalled for sampl<strong>in</strong>g purposes near <strong>the</strong><br />

water table, shallow domestic wells, and<br />

deeper public supply wells. Median depths of<br />

<strong>the</strong> wells were 36 feet, 119 feet, and 197 feet,<br />

respectively.<br />

Very shallow monitor<strong>in</strong>g wells<br />

Shallow domestic wells<br />

Deeper public supply wells<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7<br />

Number of pesticides per well<br />

Figure 21. Most detections of more than one pesticide occurred <strong>in</strong><br />

samples from very shallow monitor<strong>in</strong>g wells.<br />

Radon, a naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

radioactive decay product of radium,<br />

is a water-soluble gas from bedrock<br />

that emits high-energy alpha particles<br />

that can damage lung tissue.<br />

The primary health risk from radon<br />

and its decay products appears to be<br />

from <strong>in</strong>halation of <strong>the</strong> gas, although<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is an <strong>in</strong>creased health risk from<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water with high concentrations<br />

of radon. Dissolved radon is<br />

easily released <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> air when<br />

water is used for shower<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r purposes. In 151 ground-water<br />

samples, radon concentrations<br />

ranged from 110 to 4,100 picocuries<br />

per liter (pCi/L); <strong>the</strong> median concentration<br />

was 530 pCi/L, similar to <strong>the</strong><br />

median <strong>in</strong> many parts of <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States (p. 23).<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1144 11

MAJOR ISSUES AND FINDINGS -<br />

PESTICIDES IN SURFACE WATER<br />

Pesticides were detected <strong>in</strong><br />

streams all over <strong>the</strong> plateau<br />

Thirty-one surface-water sites represent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

agricultural land use with different<br />

crops, irrigation methods, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

agricultural practices were sampled for<br />

pesticides. Pesticides were detected <strong>in</strong><br />

samples from all sites except for Palouse<br />

River at Laird Park, a headwaters<br />

site <strong>in</strong> a forested area (see map, p. 24).<br />

Pesticide detections are usually related<br />

to pesticide applications (fig. 23) but are<br />

also <strong>in</strong>fluenced by agricultural practices,<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> rate of application, <strong>the</strong><br />

rate at which <strong>the</strong> pesticide breaks down<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> soil and water, and <strong>the</strong> ability of<br />

<strong>the</strong> pesticide to dissolve and be transported<br />

by water (fig. 24).<br />

Concentrations of some<br />

pesticides may be harmful<br />

to aquatic life<br />

Many pesticides were detected <strong>in</strong> surface<br />