Philadelphia County Natural Heritage Inventory, 2008 (2)

Philadelphia County Natural Heritage Inventory, 2008 (2)

Philadelphia County Natural Heritage Inventory, 2008 (2)

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

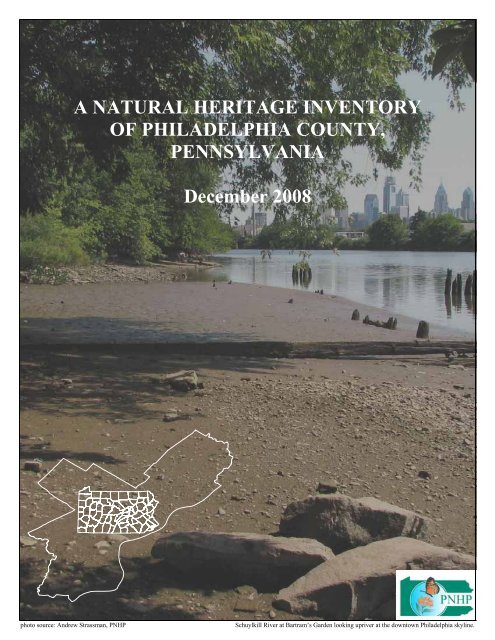

A NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORYOF PHILADELPHIA COUNTY,PENNSYLVANIADecember <strong>2008</strong>photo source: Andrew Strassman, PNHPSchuylkill River at Bartram’s Garden looking upriver at the downtown <strong>Philadelphia</strong> skyline.

A NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORYOF PHILADELPHIA COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIADecember <strong>2008</strong>Submitted to:City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>Prepared by:Pennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> ProgramWestern Pennsylvania ConservancyMiddletown Office208 Airport DriveMiddletown, Pennsylvania 17057Copies of this document may be view at:City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>orfrom the web in electronic format at:http://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/CNAI_Download.aspxThis project was funded through a grant from the William Penn Foundation.The Pennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Program (PNHP) is a partnership between the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC), thePennsylvania Department of Conservation and <strong>Natural</strong> Resources (DCNR), the Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC), and thePennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC). PNHP is a member of NatureServe, which coordinates natural heritage efforts throughan international network of member programs—known as natural heritage programs or conservation data centers—operating in all 50 U.S.states, Canada, Latin America and the Caribbean.

PREFACEThe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong>is a document compiled and written by thePennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Program (PNHP) ofthe Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC). Itcontains information on the general locations of rare,threatened, and endangered species, of the highestquality natural areas in the county, and area in needof restoration to native habitat. It is not an inventoryof all open space and is based on the best availableinformation. It is intended as a conservation tooland should in no way be treated or used as a fieldguide.Accompanying each site description are generalmanagement and restoration recommendations thatwould help to ensure the protection and continuedexistence of these natural communities, rare plants,and animals and enhance the quality of existinggreenspace and open space. The recommendationsare based on the biological needs of these elements(communities and species) and the efforts necessaryto maintain the health of the natural system ingeneral. The recommendations are strictly those ofthe Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and do notnecessarily reflect the policies of the state or thepolicies of the City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, for which thereport was prepared.Managed areas such as federal, state, city lands,private preserves, and conservation easements arealso provided on the maps where that informationwas available to us. This information is useful indetermining where gaps occur in the protection ofland with locally significant habitats, naturalcommunities, and rare species. The mappedboundaries are approximate and our list of managedareas may be incomplete, as new sites are alwaysbeing added.Implementation of the recommendations is up to thediscretion of the landowners. However, cooperativeefforts to protect the highest quality natural featuresthrough the development of site-specificmanagement plans are greatly encouraged.Landowners working on the management of, or siteplans for, specific areas described in this documentare encouraged to contact the Pennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong><strong>Heritage</strong> Program for further information.Although an attempt was made through meetings,research, and informal communications to locate thesites most important to the conservation ofbiodiversity within the county, it is likely that somethings were missed. Anyone with information onsites that may have been overlooked or the locationof species of concern should contact the responsibleagency (see Executive Summary page ix).The results presented in this report represent a snapshot in time, highlighting the sensitive natural areaswithin <strong>Philadelphia</strong> and areas with a high potential for ecological restoration. The sites in the <strong>Philadelphia</strong><strong>County</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> have been identified to help guide wise land use and county planning.The <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> is a planning tool, but is not meant to be used as asubstitute for environmental review, since information is constantly being updated as natural resources areboth destroyed and discovered. Applicants for building permits and Planning Commissions should conductfree, online, environmental reviews to inform them of project-specific potential conflicts with sensitivenatural resources. Environmental reviews can be conducted via a link on the Pennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong><strong>Heritage</strong> Program’s website, at http://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/. If conflicts are noted during theenvironmental review process, the applicant is informed of the steps to take to minimize negative effects oniii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis project was funded by a grant from the WilliamPenn Foundation. Additional in-kind support wasprovided by the Western Pennsylvania Conservancyand the City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>. Thanks to everyonewho provided financial and administrative supportfor the inventory. Without your help, this studywould not have been possible.The species information utilized in the inventorycame from many sources as well as our own fieldsurveys. We wish to acknowledge all of those whocarried out botanical and zoological survey workover the years. Without their contributions, thissurvey would have been far less complete.The report benefited from the help of localnaturalists, conservationists, and institutions whogave generously of their time. Thanks to all the helpand support given by:Academy of <strong>Natural</strong> Sciences, Phila. – Rich HorwitzTim Block – Morris Arboretum, BotanistDelaware River City Corporation – Sarah ThorpeFairmount Park Commission – Tom Witmer, Sarah LowJohn Heinz NWR – Gary Stolz, Brendalee PhillipsPartnership for the Delaware Estuary – Danielle Kreeger<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Industrial Development Corporation<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Water Department – Glen Abrams, LanceButler, Jason Cruz, Debby PajerowskiAnn Rhoads – Morris Arboretum, BotanistKeith Russell – Pennsylvania Audubon Society, Phila.Area CoordinatorSchuylkill Center for Environmental EducationSchuylkill River Development CorporationStephanie Seymour – Seasonal Field EcologistUS Army Corps of Engineers – <strong>Philadelphia</strong> DistrictMany thanks to everyone who participated in theTechnical Advisory Committee, including many ofthe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> GreenPlan Management Group, byreviewing the draft <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong>Report:Robert Allen – Fairmount Park CommissionJoan Blaustein – Phila. FPC Director of Environment,Stewardship, & EducationWilliam Bradley – Phila. Division of TechnologySantiago Burgos – Phila. Commerce DepartmentDavid Burke – DEP, Watershed ManagerLance Butler – Phila. Office of WatershedsJason Cruz – Phila. Office of WatershedsMark Focht – Fairmount Park CommissionEva Gladstein – Phila. Commerce DepartmentDiane Kripas – DCNR, Recreation and Conservation,GreenwaysAlex MacDonald – DCNR, Recreation and Conservation,GreenwaysBarbara McCabe – Phila. Recreation DepartmentHoward Neukrug – Phila. Office of WatershedsAnn Rhoads – Morris Arboretum, BotanistsKeith Russell – PA Audubon Society, Phila. AreaCoordinatorFlavia Rutkosky – US FWS, Regional BiologistDiane Schrauth – William Penn FoundationGary Stolz – John Heinz National Wildlife RefugeCarolyn Wallis – DCNR, Recreation and ConservationTom Witmer – Fairmount Park CommissionAlan Urek – Phila. City Planning CommissionFinally, we especially wish to thank the manylandowners that granted us permission to conductinventories on their lands; they are too numerous tolist. The task of inventorying the natural heritage of<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>County</strong> would have been far moredifficult without this tremendous pool of informationgathered by many people over many years.Sincerely,Andrew StrassmanPennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> ProgramThis reference may be cited as:Pennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Program. <strong>2008</strong>. A <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>County</strong>. WesternPennsylvania Conservancy. Middletown, PA.iv

NORRISTOWNLANSDOWNE222210129121311GERMANTOWNFigure 1. Map of sites in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>County</strong> by township and USGS Quadrangle.CAMDENHATBOROFRANKFORD876556411LANGHORNE2BEVERLYThis map displays boththe <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong>Significance Rank and ConservationPriority Rank of each site: SignificanceRank is conveyed by the fill color of thesite and Conservation Priority Rank isconveyed by the outline color of the site. Theranking system is explained in the results section.StreamsUSGS QuadranglesConservation Priority Rank311Figure 1. <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Natural</strong><strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>Significance and ConservationPriority.SiteSite Name#1 Poquessing Creek Greenway2 Poquessing Creek Uplands& Benjamin Rush State Park3 Byberry Creek Upland Forest4 Northeast <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Airport5 Pennypack Park6 Delaware River Shoreline7 Frankford Creek8 Tacony Creek Park9 Wissahickon Valley10 Schuylkill River Uplands11 Fairmount Park12 Tidal Schuylkill River Corridor13 Schuylkill River Oil Lands - North14 Schuylkill River Oil Lands - South15 Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park16 <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Navy Yard17 Army Corps Yard18 Mingo Creek Tidal Area19 Fort Mifflin Shoreline20 Eastwick Property21 John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge& Little Tinicum Island22 Cobbs Creek Park and GreenwayBRISTOL2121BRIDGEPORT19201819171415PHILADELPHIAWOODBURY= 1 / 4 square mile160 acres16ImmediateNear-term<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> Significance RankExceptionalHighEnhancementOpportunisticNotableLocalNone0 1.5 3 6 9 12MilesvMOUNT HOLLY

Site #Table 1.Alphabetical Site Index Numbered Roughly Northeast to Southwest.Site NameUSGSQuadrangle(s)ConservationPriority*<strong>Natural</strong><strong>Heritage</strong>Significance*Page #17 Army Corps Yard <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Opportunistic Notable 903 Byberry Creek Upland ForestHatboro,FrankfordNear-term Local 11622Cobbs Creek Park and Lansdowne,Greenway<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Enhancement Notable 67Beverly, Camden,6 Delaware River Shoreline Frankford, Immediate Notable 133<strong>Philadelphia</strong>,20 Eastwick PropertyLansdowne,<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Immediate Notable 8211 Fairmount ParkGermantown,<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Enhancement Notable 6819 Fort Mifflin ShorelineBridgeport,<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, Near-term High 86Woodbury7 Frankford CreekCamden,FrankfordEnhancement Local 12815 Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Enhancement Notable 6921John Heinz National WildlifeBridgeport,Refuge &LansdowneLittle Tinicum IslandImmediate Exceptional 7618 Mingo Creek Tidal Area <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Immediate Notable 944 Northeast <strong>Philadelphia</strong> AirportBeverly,FrankfordOpportunistic Local 1245 Pennypack Park Frankford Enhancement Notable 6916 <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Navy Yard <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Near-term High 981 Poquessing Creek GreenwayBeverly,Frankford, Immediate Local 70Langhorne,2Poquessing Creek Uplands Beverly,& Benjamin Rush State Park FrankfordImmediate Local 12013Schuylkill River Oil Lands -North<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Opportunistic None 10214Schuylkill River Oil Lands -South<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Opportunistic None 10210 Schuylkill River UplandsGermantown,NorristownNear-term Notable 1128 Tacony Creek Park Frankford Enhancement Local 7212 Tidal Schuylkill River Corridor <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Immediate Notable 1079 Wissahickon Valley Germantown Enhancement Notable 72Table 1. Alphabetical Site Index Numbered Roughly Northeast to Southwest.*For an explanation of ranking see method section page 47vii

viii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYIntroductionEXECUTIVE SUMMARYAlthough urban landscapes have drastically alteredtheir natural settings, nature and natural processesabound within even highly developed urban areas.Within <strong>Philadelphia</strong> these processes are exemplifiedby the bald eagles nesting downtown, the millions ofAmerican shad migrating through the Delaware andSchuylkill Rivers each spring northward to theirbreeding habitat, and the white-tailed deer browsingshrubs in people’s backyards. These events, ratherthan accidents or rare occurrences, are an active partof a functioning landscape where the cityscape andthe wildlands not only meet, but integrate.With actions to reduce pollution and betterstewardship of natural resources, these interactionswill occur within the city on a more frequent basis,though there are actions that can be taken toencourage them to occur in a regular and sustainablemanner and in a pattern compatible with urban life.Through changes in how <strong>Philadelphia</strong> and itsresidents perceive development, open space, andgreenspace the cycle of re-development within thecity can produce areas that meet not only the needfor a revitalized cityscape, but the need forintegrated wildlands too. GreenPlan <strong>Philadelphia</strong>(available at www.greenplanphiladelphia.com),through a series of targets and recommendations,will provide the city with the framework to makesome of these changes and to help accomplish someof the recommendations provided in this document.History<strong>Philadelphia</strong> occupies land that has hosted Europeansettlements since the early 1600’s, and NativeAmerican tribes long before then. Starting withsmall farmsteads along the tidal marshes of theDelaware River, Pennsylvania came into existencewith William Penn’s charter in 1681. Shortlyafterwards, William Penn instructed the formation ofthe town of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> with these orders to hiscommissioners:"Let every house be placed, if the personpleases, in the middle of its plat, as to thebreadthway of it, so that there may be ground oneach side for gardens or orchards, or fields, thatit may be a greene country towne, which willnever be burnt & always wholesome."William Penn's Instructions to hisCommissioners, September 30 th , 1681This vision was short lived as the reality ofeconomic and social needs superseded Penn’s ideaof an agrarian utopia. By the time BenjaminFranklin arrived in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> in 1723, a mere 42years after Penn’s instructions, the town was alreadya bustling center of trade in the new world and oneof the largest cities in North America.During the past three centuries the natural landscapeof <strong>Philadelphia</strong> has been heavily modified by humanuse. Starting as a landscape of sweeping tidalmarshes along the Schuylkill and Delaware Riversthat marched up to the start of Penn’s Woods, earlycolonists transformed this into an agriculturallandscape of small farmsteads and woodlots. As<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s population and economy grew,factories, warehouses, a port, and the infrastructureto support them (such as roads, dams, and houses)arouse around the point of Penn’s Landing and theagricultural fields (and forests) were pushed furtheraway. As the population grew and technologyprogressed, the marshes were filled and the riverswere walled in and straightened.Today little of this original natural landscaperemains within the borders of the City of<strong>Philadelphia</strong>. As incorporated in the 1854 Act ofConsolidation, the City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> coversapproximately 170 square-miles. Within that area isapproximately 13 square-miles of parkland managedby the Fairmount Park System of which 7.5 squaremilesis managed as natural area. This park system,while one of the most extensive of any city in thenation, offers challenges to maintaining naturaldiversity in a highly-developed fully urban setting.OverviewAs part of the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> City PlanningCommission’s initiative, Imagine <strong>Philadelphia</strong>:Laying the Foundation, GreenPlan <strong>Philadelphia</strong>aims to assess the City’s needs to establishecologically sustainable infrastructure in respect tothe future vision <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s residents have oftheir city. An important aspect of GreenPlanix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<strong>Philadelphia</strong> is an up-to-date inventory of theirexisting and potential ecological resources.Because of the degree of development within<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, the existing natural resources havebeen well documented. This includes recent workby the Fairmount Park Commission, the <strong>Philadelphia</strong>Water Department, and the Academy of <strong>Natural</strong>Sciences to survey the city’s parklands. In an effortnot to duplicate work already conducted, thePennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Program (PNHP)conducted surveys on public and private lands notincluded in the original Fairmount Park master planand on lands not currently managed as parks. Thisgenerally includes brownfields, lands owned byother city agencies or agents of the city, and privatelands where we secured access permission.Our survey efforts primarily focused on thediscovery of new populations of plants and animalsconsidered rare, threatened, or endangered within theCommonwealth. When these species were found wedocumented the occurrence and noted the conditionsthey were growing under. Often, we found nospecies of concern, but did create a description of thecurrent site conditions for use in site descriptionsand restoration recommendations sections in thefinal report.Overall, twenty-nine sites totaling approximately3,000 acres of land were identified in 2007; only themost promising areas were surveyed within the sites.For each of these sites we include a generaldescription of the current habitat, any rare speciesfound there, conservation recommendation for therare species present, and restorationrecommendations to increase the natural habitatvalue.MethodsSixty of sixty-seven county inventories have beencompleted in Pennsylvania to date. The <strong>Philadelphia</strong><strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> followed similarmethodologies as previous inventories, which areconducted in the following stages:Information GatheringA review of various databases determined wherelocations for special concern species and importantnatural communities were known to exist in<strong>Philadelphia</strong>. Knowledgeable individuals wereconsulted concerning the occurrence of rare plantsand unique natural communities in the county.Geologic maps, United States Geological Survey(USGS) topographical maps, National Wetlands<strong>Inventory</strong> maps, recent aerial imagery, and otherpublished materials were also used to identify areasof potential ecological significance.Field WorkAreas identified as potential inventory sites werescheduled for ground surveys. After obtainingpermission from landowners, sites were examined toevaluate the condition and quality of the habitat andto classify the communities present. The flora, fauna,level of disturbance, approximate age of any naturalcommunity, and local threats were among the datarecorded for each site. Sites were not groundsurveyed in cases where permission to visit a site wasnot granted, when enough information was availablefrom other sources, or when time did not permit.Data AnalysisData obtained during the 2007 and <strong>2008</strong> fieldseasons was combined with prior existing data andsummarized. All sites with species or communitiesof statewide concern, as well as sites with a highrestoration potential will be mapped and described.The boundaries defining each site will be based onphysical and ecological factors, and specificationsfor species protection provided by governmentjurisdictional agencies.ResultsDuring the 2007 and <strong>2008</strong> field seasons PNHP staffand contracted experts conducted surveys around<strong>Philadelphia</strong> (Fig. 1, pg. v, Table 1, pg. vii). Overthis time approximately 52 person days of fieldworkwere conducted in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> at 20 distinctlocations. New occurrences of rare, threatened, andendangered species were found during these surveyswith these finds concentrated along the tidal areas ofthe Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. Among thehigh points was the confirmation of a species knownonly from historic records; this species, Needham’sskimmer dragonfly (Libellula needhami), was foundalong the Delaware River shoreline.x

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYAdditionally, our surveys indicate that restorationefforts within the tidal area have a high potential forsuccess given the abundant local seed sources in theJohn Heinz National Wildlife Refuge and along theNew Jersey shoreline. This is evident through thetidal wetland restoration project at Pennypack on theDelaware Park where the wetland and uplandsupport several Pennsylvania species of concern.However, our surveys found that non-native invasivespecies may be the greatest threat to natural areaswithin <strong>Philadelphia</strong> and the greatest impediment tonatural-land restoration projects. These species havetaken over extensive areas of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> displacingthe native plants and the animals they support,decreasing the overall ecological (native) diversityand values.Other issues affecting the habitat value of several ofthe sites we visited are illegal dumping of garbage,construction materials, and abandoned cars, andATV use within the sites. These actions have causedmoderate to extensive damage at several sites andwill need to be mitigated through enforcement ofexisting ordinances.General Conservation Recommendations<strong>Philadelphia</strong> has a number of groups and institutionspursuing the protection and restoration of naturalareas within the city. The following are generalrecommendations for protecting the biological healthof the City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.1. Consider conservation initiatives and toolsfor natural areas on private land2. Orient management and restoration plans toaddress species of special concern andnatural communities as targets ofconservation (not simply open or multi-usespace) through the active maintenance ofexisting high quality natural area andrestoration of more degraded spaces3. Protect bodies of water with adequatenatural buffers4. Provide for buffers around natural areas5. Increase the connectivity of the city’s greenspace with surrounding landscapes6. Encourage and utilize existing grassrootsorganizations interested in preserving andrestoring the city’s natural areas7. Manage for control of known invasivespecies and early detection of new invasivespecies in key natural area8. Promote community education on theimportance of ecological health in urbanenvironments9. Incorporate <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong>information into city planning effortsDiscussion and <strong>County</strong>-specificRecommendationsPlan for biodiversity and ecological health:Provisioning for the future health of ecologicalresources in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> will require action onmany fronts. Special consideration should be givento steward specific sites that host unique species andcommunities. Broadscale planning efforts shouldendeavor to create contiguity of natural habitats.Restoration efforts to alleviate water pollution andrestore ecological function to damaged landscapesand waterways should be undertaken with specialattention given to riparian and tidal habitatrestoration.Two problems needing special attention within<strong>Philadelphia</strong> are the prevalence of non-nativeinvasive species and white-tailed deer. Theseproblems are interrelated in that deer prefer to eatnative plants and thus promote the spread of nonnativeplant species. Without active, coordinated,and targeted control of deer and non-native plantspecies followed by restoration and maintenance ofreestablished native species the existing natural areaswithin the city will continue to deteriorate. Whiledaunting, this can be achieved by the use of deerfences and control programs and the encouragementand mobilization of private citizens and publicgroups. Facilitating “weed warriors” groups withinthe city and providing for the replanting of nativespecies in maintained areas will work towards thegoal of preserving the biological health of thelandscape.Wetland/Aquatic Communities: <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’saquatic systems have undergone substantialmodification over the past 300 years. Oncesupporting extensive lowland and floodplain forestsand 10 to 20 square-miles of tidal marsh, todaymany of the rivers are confined by armored banks,xi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYhave extensively urbanized headwaters, and lessthan ¼ square-mile of tidal marsh remains within thecity proper. To restore water quality within the citythese issues need to be addressed through large-scaleplanning initiatives. This can occur throughreconnecting the 100-year floodplain to rivers andcreeks throughout the city, actively restoring thetidal marsh on the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers,and initiating a concerted effort to reduce combinedsewage outflows and stormwater discharge.Stewardship or restoration of native forestcommunities in and beyond riparian buffers alongwaterways will greatly improve water quality andenhance the habitat value for various aquatic andsemi-aquatic species. Attending to the basicecological functions of streams and wetlands willincrease human welfare by ensuring the continuedavailability of quality water for human communities,enabling the restoration of healthy fisheries, andenhancing the quality of life for city residents.One suggested project to meet these goals would beestablishing a public greenway along the Delawareand Schuylkill Rivers that incorporates reconnectionof the floodplain and reestablishment of tidal marshas a component. This would create a green corridoralong the city’s shore in a flood-prone area and actas a connector between the existing parks along thePennypack, Wissahickon, and Frankford Creekswith potential connection to Poquessing Creek andeventually Neshaminy State Park.Forest Communities: In the forested landscapes,objectives for large-scale planning should includemaintaining and increasing contiguity andconnectivity of forested land. Contiguity isimportant for the enhanced habitat values; however,for many species, it is equally critical that naturalcorridors are maintained, which connect forests,wetlands, and waterways. For example, manyamphibians and dragonflies use an aquatic orwetland habitat in one phase of their life thenmigrate to an upland or forested habitat for theiradult life. Either habitat alone cannot be utilizedunless a corridor exists between them.In areas where these connections have been severed“reforestry” activities can help to restore contiguous,usable habitat. In conjunction with the reforestationof riparian areas within <strong>Philadelphia</strong> throughprojects such as Treevitalize, reconnection of uplandforests can be achieved. Projects to replant nativetrees along streets lacking tree cover and in areas ofunder- and unutilized land can quickly increase treecover within <strong>Philadelphia</strong>. Planting projects providenot only the benefits of reducing the urban “heatisland” effect, but act as natural habitat steppingstones through the urban environment.Evaluating proposed activity within sites: A veryimportant part of encouraging conservation of thesites identified within the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Natural</strong><strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> is the careful review of proposedland use changes or development activities thatoverlap with or abut <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas. This isespecially important when examining the large areasof open land along the Schuylkill and DelawareRivers. These flood-prone areas are affectivelywithin the river during times of flooding and shouldbe consider unfit for major building projects.Conversion of these areas, especially the portionswithin the 100-year floodplain, to greenspace shouldbe a priority as the redevelopment of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’swaterfront is undertaken. The following overviewshould provide guidance in the review of theseprojects or activities.• Always contact the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> City PlanningCommission.The City Planning Commission should be aware ofall activities that may occur within <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>Areas in the city so that they may interact with theother necessary organizations or agencies to betterunderstand the implications of proposed activities.They can also provide guidance to the landowners,developers, or project managers as to possibleconflicts and courses of action.• Conduct free online preliminary environmentalreviewsApplicants for building permits should conduct free,online, environmental reviews to inform them ofproject-specific potential conflicts with sensitivenatural resources. Environmental reviews can beconducted by visiting the Pennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong><strong>Heritage</strong> Program’s website, athttp://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/. If conflictsxii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYare noted during the environmental review process,the applicant is informed of the steps to take tominimize negative effects on the county’s sensitivenatural resources.Depending upon the resources contained within the<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Area, the agencies/entitiesresponsible for the resource will then be contacted.The points of contact and arrangements for thatcontact will be determined on a case-by-case basisby the city and the Department of EnvironmentalProtection. In general, the responsibility forreviewing natural resources is partitioned amongagencies in the following manner:• U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for all federallylisted plants and animals.• Pennsylvania Game Commission for all state andfederally listed terrestrial vertebrate animals.• Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission for allstate and federally listed reptiles, amphibians, andaquatic vertebrate and invertebrate animals.• Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry for all state andfederally listed plants.• Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and<strong>Natural</strong> Resources for all natural communities,terrestrial invertebrates, and species not fallingunder the above jurisdictions.PNHP and agency biologists can provide moredetailed information with regard to the location ofnatural resources of concern in a project area whenthis information is available for public distribution,the needs of the particular resources in question, andthe potential impacts of the project on thoseresources.• Plan aheadIf a ground survey is necessary to determine whethersignificant natural resources are present in the areaof the project, the agency biologist reviewing theproject will recommend a survey be conducted.PNHP, through the Western PennsylvaniaConservancy, or other knowledgeable contractorscan be retained for this purpose. Early considerationof natural resource impacts is recommended to allowsufficient time for thorough evaluation. Given thatsome species are only observable or identifiableduring certain phases of their life cycle (i.e., theflowering season of a plant or the flight period of abutterfly), a survey may need to be scheduled for aparticular time of year.• Work to minimize environmental degradationIf the decision is made to move forward with aproject in a sensitive area, PNHP can work withmunicipal officials and project personnel during thedesign process to develop strategies for minimizingthe project’s ecological impact while meeting theproject’s objectives. The resource agencies in thestate may do likewise.Conclusion<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s natural landscape is fragmented anddegraded by three centuries of urban development,but maintains aspects of the original pre-settlementhabitats. As the City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> moves forwardwith urban infill plans and redevelopment ofabandoned industrial areas, greenspace and naturalareas should be a serious consideration. Significantand substantial opportunities exist for thefortification of rare species populations, therestoration of native habitat, and the reconnection ofisolated patches of existing native habitat to formcontiguous corridors of green space throughout thecity. These green spaces can help expand thealready impressive public park system into areasunderserved by these amenities to help make<strong>Philadelphia</strong> a more attractive place to live andwork. However, these opportunities are transient atbest and if they are not utilized now the vision ofWilliam Penn for his City of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> will fadefurther into the past. GreenPlan <strong>Philadelphia</strong> offersthe opportunity to establish a framework forecologically sustainable infrastructure developmentwith the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong>providing a roadmap to the areas of greatestecological potential.xiii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYTable 2.The sites of significance for the protection of biological diversity in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>County</strong> categorized by naturalheritage significance rank. More in-depth information on each site including detailed site descriptions andmanagement recommendations where appropriate can be found in the text of the report following the maps foreach site. Quality ranks, legal status, and last observation dates for species of special concern and naturalcommunities are located in the table that precedes each map page. Appendix IV gives an explanation of the PA<strong>Heritage</strong> and Global vulnerability ranks. Note that “Species of Special Concern” denotes a species not named at therequest of the agency overseeing its protection.Site #Site NameUSGS Quadrangle(s)Exceptional Significance Sites21John Heinz National WildlifeRefuge & Little Tinicum IslandBridgeport, LansdowneHigh Significance Sites1916Fort Mifflin ShorelineBridgeport, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, Woodbury<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Navy Yard<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Notable Significance Sites17226Army Corps Yard<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Cobbs Creek GreenwayLansdowne, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>Delaware River ShorelineBeverly, Camden, Frankford,<strong>Philadelphia</strong>DescriptionTable 2. Ranking of Sites of <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong> Significance.The Tinicum Marsh system hosts a suite of species found only along the tidalDelaware River in Pennsylvania. These species are limited to the marsh and a fewnearby locations because this is the limit of tidal influence within theCommonwealth. These species break out into four general groups: plants withfifteen listed species; birds with nine listed species, herptiles with three listedspecies and two listed communities.Fort Mifflin and the surrounding shoreline remain biologically important becausethey maintain aspects of the original tidal marsh that composed the area. Thesetidally influenced areas dot the shoreline from the fort downriver to the mouth ofDarby Creek and include seven plant, two insect, and one bird species of concernalong with one community of concern. Additionally, the Delaware River adjacentto this site hosts extensive beds of floating aquatic vegetation.Large areas of the Navy Yard were reverting to natural cover opening them up tocolonization by grassland species with the lower, wetter areas supporting wetlandspecies. The site supports 72 native plant species with an additional 46 non-nativeplant species recorded at the site. Of these plant species five are listed as speciesof concern in the Commonwealth. An additional two bird species of concern arefound utilizing the Navy Yard.This site provides excellent hunting habitat for adult dragonflies and damselflieswith two species of concern noted at the site feeding on the extensive aggregationof insects over the ponds. One of the local peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus)has also been observed feeding at this location. It seems likely that these speciesof concern are reproducing surrounding landscape and simply refueling andmaturing here.This site supports several different populations of a single species of concern,elephant's foot (Elephantopus carolinianus). This plant, typically found muchfurther south in the United States, is found in a few of the southern counties of theCommonwealth.This extensive site along the Delaware River shoreline is tidally influenced alongits length and has the ability to support tidal species of concern throughout the site.The species of concern noted within this site are only found in specific areas wheretidal habitat remains protected and in a few of the more naturally managed park.Pages7686989067133xiv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYTable 2: continuedSite #Site NameUSGS Quadrangle(s)DescriptionPage(s)Notable Significance Sites cont.2011151851012Eastwick PropertyLansdowne, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>Fairmount ParkGermantown, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Mingo Creek Tidal Area<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Pennypack ParkFrankfordSchuylkill River UplandsGermantown, NorristownTidal Schuylkill River Corridor<strong>Philadelphia</strong>This property has reverted to a wild, if weedy, landscape that is supporting twoplant species of concern: field dodder (Cuscuta pentagona) and forked rush(Juncus dichotomus). These are both residents of disturbed areas and do well inthis environment and likely originated in the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge,which the property abuts on both its south and west sides.This park once supported populations of species of concern, but the level ofmanagement and development within the park has reduced the amount of naturalhabitat to a very small area. While these areas have the potential to maintainpopulations of species of concern, only one is current known. Pied-billed grebes(Podilymbus podiceps) occasionally nest on the East Park Reservoir and fledgedyoung in 2007. This park offers a significant island of green for many nativewildlife species in the urban environment.This park, part of the Fairmount Park System, still maintains limited tidalconnectivity and some of the tidal species associated with it. Within the site aretwo plant species of concern associated with tidal areas: multiflowered mudplantain(Heteranthera multiflora) and Walter's barnyard-grass (Echinochloawalteri). Additionally, the park contains an extensive array of odonates supportedby the lagoons.This area, which has been only partially surveyed, contains habitat that supportsNeedham’s Skimmer (Libellula needhami), a species of dragonfly last recorded inthe Commonwealth in 1945 and found again at this site in 2007. The extensiveareas of wetland-like habitat on this site are the likely source of this occurrence.This park, built around a forested riparian corridor running from the DelawareRiver up Pennypack Creek into Montgomery <strong>County</strong>, supports nesting osprey(Pandion haliaetus) in its upper reaches and two wetland species towards its tidalmouth. The small, tidal wetland at the mouth of the creek was created as amitigation project and maintains two species of concern, the Halloween pennantdragonfly (Celithemis eponina) and the marsh wren (Cistothorus palustris).This large, amazingly intact patch of land offers upland forest, meadow, and highgradientfirst-order streams that support three plant species of concern and offerhabitat to many other species rare in the area. Found in the more open meadowlikeareas oblique milkvine (Matelea obliqua) and round-leaved thoroughwort(Eupatorium rotundifolium) are residents of early-successional habitat whilereflexed flatsedge (Cyperus refractus) is a species noted on this site only along thefloodplain of the Schuylkill River.Acting as a nesting and foraging area for a pair of Peregrine Falcons (Falcoperegrinus), the northern portion of this reach of the Schuylkill River is otherwisefully urbanized and not noted for any other species of concern. Furtherdownstream the tidal Schuylkill River helps support three plant species of concernat this site. Two, river bulrush (Schoenoplectus fluviatilis) and salt-marsh waterhemp(Amaranthus cannabinus), are known from a created wetland while theother, annual wild rice (Zizania aquatica), is known from the tidal mudflats foundalong the river banks. Because of safety concerns, a majority of this area has notbeen surveyed including the forest and wetland patches that have aerialphotography signatures comparable to areas known to harbor species of concern.For this reason we believe this site will be found to host species concern andwarrant a higher NHI significance ranking.8268699469112107xv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYTable 2: continuedSite #Site NameUSGS Quadrangle(s)DescriptionPage(s)Notable Significance Sites cont.9Wissahickon ValleyGermantown, NorristownWhile this park is known for its forested streams and uplands, two of the species ofconcern noted within the park are plants generally found in open, earlysuccessionalhabitats. Within the Houston Meadows restoration site arepopulations of forked rush (Juncus dichotomus) and round-leaved thoroughwort(Eupatorium rotundifolium). Another species, autumn bluegrass (Poa autumnalis),is a plant of moist woods and is found within the park.72Locally Significant Sites3Byberry Creek Upland ForestFrankford, HatboroWhile no tracked species have yet been discovered within these woods, they offeran example of some of the forest that once covered this region. Dominated byAmerican beech (Fagus americana), red oak (Quercus rubra), and tulip poplar(Liriodendron tulipifera) this forest also supports 127 native species of plant alongwith numerous other insects, birds, and mammals.While this site currently offers little possibility of providing habitat for species ofconcern, if restored and managed it would offer a forested riparian corridor fromthe Delaware River through urban <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.Given the current management of this are as an active airport there is littlepotential for this site to host species of concern. However, the large grassy openareas within the site offer habitat known to support Lepidoptera species of concernwithin the city, which PNHP was not able to survey for given safety concerns.Currently, no species of concern are known from this site, but this is possibly dueto incomplete survey of the area. Acting as a natural forested riparian corridorfrom the tidal Delaware River north into both Bucks and Montgomery Countiesthis site offers the potential to host species of concern.This area of open upland meadow likely hosts plant species of concern that hassimply been missed. Additionally, the site hosts species that, while not trackedwithin the Commonwealth, are uncommon within <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.Tacony Park is not known to host any species of concern. Acting as an importantwildlife corridor up until the Frankford Creek site border, the wildlife value of thissite could be significantly improve with the completion of the corridor to theDelaware River.1167Frankford CreekCamden, Frankford1284Northeast <strong>Philadelphia</strong> AirportBeverly, Frankford1241Poquessing Creek GreenwayBeverly, Frankford, Langhorne702Poquessing Creek Uplands andBenjamin Rush State ParkBeverly, Frankford1208Tacony ParkFrankford72No <strong>Heritage</strong>-significance Sites1416Schuylkill River Oil Lands –North & South<strong>Philadelphia</strong>These sites are still actively used for the processing of petroleum products.Additionally, the area has experienced sustained industrial activity for over 150years and is highly disturbed and degraded with only a few small, highly isolatedareas maintaining any natural cover. For this reason these sites warrant no NHIsignificance rank.102xvi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYTable 3: continuedSite #Site NameUSGS Quadrangle(s)DescriptionPagesNear-term Preservation Need3Byberry Creek Upland ForestFrankford, HatboroThis large patch of woods with connecting forest to the headwaters of PoquessingCreek is currently owned by the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Industrial Development Corporation.As such it is not in immediate danger of development, but it is effective slated foreventual conversion to a more intensive land use. As one of the last large forestblocks not protected by public ownership in this area it is very important that thisproperty be protected as a natural area and not reduced to concrete and asphalt.Primarily composed of shoreline with direct tidal influence, this site is probablylittle threatened by development in the near term. Over the long term the site isthreatened by the continued expansion of the airport, degradation by the everincreasingwake size from shipping traffic, and the spraying of existing wetlandswith herbicides to prevent their continued expansion.Managed by the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Industrial Development Corporation, the remains ofthe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Navy Yard are slated for redevelopment. However, this processhas been slowed by the costs associated with the project. As redevelopment plansare created for the currently undeveloped areas it will be important to assess theenvironmental impacts of developing a site that host numerous species of concern,that used to be an island, and is almost entirely within the 100-year FEMAfloodplain.While a significant portion of this site is owned, managed, and protected by theSchuylkill Center for Environmental Education, other important parts of thisextensive block of open space remain unprotected from development.Additionally, the fate of the retired Roxborough Reservoir, an important areaacting as a wetland, remains undecided. Finally, this site acts as a significantgreenway along the Schuylkill River.11619Fort Mifflin ShorelineBridgeport, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, Woodbury8616<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Navy Yard<strong>Philadelphia</strong>9810Schuylkill River UplandsGermantown, Norristown112Enhancement Opportunities22Cobbs Creek Park & GreenwayLansdowne, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>The Cobbs Creek Greenway offers amazing opportunities for the expansion andimprovement of natural habitat along its length from the county line to John HeinzNational Wildlife Refuge. There are already efforts to remove non-native invasivespecies and replant native vegetation along the creek’s length with project ongoingthroughout the site. An additional goal should be to reestablish Cobbs Creek as ahealthy, free-flowing waterway through the removal of fish passage barriers andthrough active stormwater runoff management.An important example of fully-integrated mixed land use in a highly urbanizedsetting, Fairmount Park is also one of the older parks in the nation. Because of theparks history it is important to work to maintain the health of the natural systemsfound within the site including several small watersheds completely contained bythe park. These small watersheds support scenic first order streams that have beennegatively affected by stormwater runoff, which is entirely within the purview ofpark management to control.This site abounds with enhancement opportunities. From stormwater runoffcontrol, to riparian habitat protection and restoration, to trash clean-up, to damremoval and full-scale channel reconstruction this reach of Frankford Creek haspossible projects to accommodate any budget or number of volunteers.6711Fairmount ParkGermantown, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>687Frankford CreekCamden, Frankford128xviii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYTable 3: continuedSite #Site NameUSGS Quadrangle(s)DescriptionPagesEnhancement Opportunities cont.15Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Containing huge swaths of grass, abandoned athletic fields, and an extensive areaof land dominated by non-native invasive plant species, this park should beexamined for opportunities to expand and restore freshwater intertidal wetland.Additionally, the lagoons in the park appear to be subject to combined seweroverflows (CSO) during rain events leading to their highly eutrophied andbiologically degraded states, though no known permitted CSOs exist on the site.Cessation of these inflows along with the removal of accumulated nutrient andincreased tidal exchange could lead to a significant increase in the ecologicalfunctionality of this parkPennypack Creek Park offers an extensive area of greenspace and functions as acontiguous natural corridor from the Delaware River through <strong>Philadelphia</strong> intoMontgomery <strong>County</strong>. Enhancement of this system is already underway throughthe replanting of the floodplain with native species and removal of fish passagebarriers along the main stem. Continuation of existing project with an expansioninto upland forest restoration will increase the natural habitat quality.Management of stormwater runoff and out-fall areas within this park are of specialconcern. This small creek is being used to drain an artificially expanded“watershed” composed of an overwhelming quantity of impermeable surface.Additionally, inputs from the numerous golf courses within the watershed need tobe examined and, if they are found to be adversely impacting water quality andstream health, addressed.This park contains the largest area of natural habitat within <strong>Philadelphia</strong> andsignificant efforts need to be made to ensure that it remains this way. Ongoingrestoration needs to be supported and expanded to include the full suite ofecosystems found within the park with the intention of indefinitely sustaining theparks environmental health. Additionally, free-flowing access from the mouth ofWissahickon Creek on the Schuylkill River upstream to the headwaters inMontgomery <strong>County</strong> should be a stated goal.695Pennypack ParkFrankford698Tacony Creek ParkFrankford729Wissahickon ValleyGermantown, Norristown72Opportunistic Acquisition1741314Army Corps Yard<strong>Philadelphia</strong>Northeast <strong>Philadelphia</strong> AirportBeverly, FrankfordSchuylkill River Oil Lands –North & South<strong>Philadelphia</strong>This site is still used by the Army Corps for maintenance of the Delaware Rivershipping channel. However, if the site were to become available for otherpurposes restoration to a freshwater tidal community should be examined.Still an active airport, this site offers an extensive area of mead and wetland-likehabitat with significant habitat improvement opportunities where they do notconflict with the maintenance of airport safety.This land is still actively used for the refining of oil. Given the over 150 years ofindustrial activity on the site its conversion to any other use may be costly, but ifalternative uses are proposed then conversion to greenspace must be considered.90124102xix

TABLE OF CONTENTSPREFACE ...........................................................................................................................................................................................iiiACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................................... ivEXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ ixTABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................................. xxiINTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1NATURAL HISTORY OVERVIEW OF PHILADELPHIA........................................................................................................... 3PHYSIOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY...............................................................................................................................................................................3BEDROCK AND SOILS ...............................................................................................................................................................................................4WATERSHEDS ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................5NATURAL COMMUNITIES OF PHILADELPHIA....................................................................................................................... 7TERRESTRIAL COMMUNITIES..................................................................................................................................................................................7WETLAND COMMUNITIES......................................................................................................................................................................................10DISTURBANCES IN PHILADELPHIA......................................................................................................................................... 13DAMS .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................14INVASIVE SPECIES .................................................................................................................................................................................................15ECOLOGICAL REHABILITATION, RESTORATION, AND RE-CREATION IN PHILADELPHIA ................................. 21MAMMALS OF PHILADELPHIA ................................................................................................................................................. 23BIRDS OF PHILADELPHIA........................................................................................................................................................... 27REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS OF PHILADELPHIA............................................................................................................... 33FISHERIES OF PHILADELPHIA.................................................................................................................................................. 38INSECTS OF PHILADELPHIA...................................................................................................................................................... 43BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS ....................................................................................................................................................................................43DRAGONFLIES AND DAMSELFLIES.........................................................................................................................................................................44METHODS......................................................................................................................................................................................... 47PNHP DATA SYSTEM ............................................................................................................................................................................................47INFORMATION GATHERING ...................................................................................................................................................................................48MAP AND AIR PHOTO INTERPRETATION ...............................................................................................................................................................48FIELD WORK .........................................................................................................................................................................................................49DATA ANALYSIS.....................................................................................................................................................................................................49PECIES RANKING....................................................................................................................................................................................................51SITE MAPPING AND RANKING ...............................................................................................................................................................................51RESULTS........................................................................................................................................................................................... 53PRIORITIES FOR PROTECTION ...............................................................................................................................................................................53CONSERVATION PRIORITY AND SITE RANKING.....................................................................................................................................................53POTENTIAL GREENSPACE QUALITY RANKING......................................................................................................................................................53SITE DESCRIPTIONS ..................................................................................................................................................................... 57FAIRMOUNT PARK SYSTEM ...................................................................................................................................................................................58JOHN HEINZ NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE – TINICUM MARSH ..........................................................................................................................74EASTWICK PROPERTY ...........................................................................................................................................................................................80FORT MIFFLIN SHORELINE ...................................................................................................................................................................................84U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS YARD ..............................................................................................................................................................88MINGO CREEK TIDAL AREA .................................................................................................................................................................................92PHILADELPHIA NAVY YARD ..................................................................................................................................................................................96SCHUYLKILL RIVER OIL LANDS – NORTH & SOUTH ..........................................................................................................................................100TIDAL SCHUYLKILL RIVER CORRIDOR ...............................................................................................................................................................104SCHUYLKILL RIVER UPLANDS.............................................................................................................................................................................110BYBERRY CREEK UPLAND FOREST .....................................................................................................................................................................114xxi

POQUESSING CREEK UPLANDS & BENJAMIN RUSH STATE PARK....................................................................................................................... 118NORTHEAST PHILADELPHIA AIRPORT ................................................................................................................................................................ 122FRANKFORD CREEK ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 126DELAWARE RIVER SHORE................................................................................................................................................................................... 130GENERAL CONSERVATION RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION ..................................................................... 142GLOSSARY...................................................................................................................................................................................... 150REFERENCES AND LITERATURE CITED .............................................................................................................................. 154GIS DATA SOURCES..................................................................................................................................................................... 159APPENDICES .................................................................................................................................................................................. 161APPENDIX I: SITE SURVEY FORM....................................................................................................................................................................... 162APPENDIX II: COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION...................................................................................................................................................... 163APPENDIX III: FEDERAL AND STATE STATUS, AND PNHP PROGRAM RANKS...................................................................................................... 166APPENDIX IV: PENNSYLVANIA ELEMENT OCCURRENCE QUALITY RANKS ......................................................................................................... 169APPENDIX V: PLANTS, ANIMALS AND NATURAL COMMUNITIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN IN PHILADELPHIA COUNTY............................................. 170APPENDIX VI: LEPIDOPTERA (BUTTERFLIES) COLLECTED DURING FIELD SURVEYS OR KNOWN FROM PHILADELPHIA COUNTY ............................. 171APPENDIX VII: ODONATES COLLECTED DURING PHILADELPHIA COUNTY FIELD SURVEYS OR OTHER COLLECTIONS ............................................. 173APPENDIX IIX: FACTS SHEETS FOR SPECIES AND COMMUNITIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN IN PHILADELPHIA COUNTY ............................................ 174TABLE OF TABLESTABLE 1. ALPHABETICAL SITE INDEX NUMBERED ROUGHLY NORTHEAST TO SOUTHWEST...................................viiTABLE 2. RANKING OF SITES OF NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY SIGNIFICANCE. .................................................xivTABLE 3. RANKING OF SITES OF CONSERVATION PRIORITY RANK. ..............................................................................xviiTABLE 4. PHILADELPHIA BEDROCK FORMATIONS. ................................................................................................................4TABLE 5. SIGNIFICANT INVASIVE PLANT SPECIES................................................................................................................16TABLE 6. SIGNIFICANT INVASIVE ANIMAL SPECIES.............................................................................................................17TABLE 7. PENNSYLVANIA NOXIOUS SPECIES LIST................................................................................................................19TABLE 8. FAIRMOUNT DAM FISH PASSAGE COUNT. .............................................................................................................41TABLE 9. STATE STATUS OF SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN IN PHILADELPHIA COUNTY.......................................143TABLE OF FIGURESFIGURE 1. MAP OF SITES IN PHILADELPHIA COUNTY BY TOWNSHIP AND USGS QUADRANGLE. ..............................vFIGURE 2. PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF PHILADELPHIA AND SURROUNDING AREA. ............................................3FIGURE 3. ROCK TYPES OF PHILADELPHIA. ..............................................................................................................................4FIGURE 4. BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF PHILADELPHIA. ...............................................................................................................4FIGURE 5. WATERSHEDS OF PHILADELPHIA.............................................................................................................................5FIGURE 6. EXISTING AND HISTORIC STREAMS OF PHILADELPHIA. ....................................................................................5FIGURE 7. HISTORICAL ECOSYSTEMS OF PHILADELPHIA. ....................................................................................................7FIGURE 8. IMPORTANT BIRD AND MAMMAL AREAS IN AND AROUND PHILADELPHIA COUNTY. ...........................26FIGURE 9. POTENTIAL GREENSPACE QUALITY AND SURVEY PRIORITY IN PHILADELPHIA......................................55FIGURE 10: DISTRIBUTION OF RARE, THREATENED, AND ENDANGERED SPECIES BY MUNICIPALITY .................142xxii

INTRODUCTION<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, founded by William Penn in 1682, beganas a pastoral farming village with the vision ofreligious tolerance. The area supported villages of theSusquehannock people long before initial Europeansettlement in 1644 as part of the colony of NewSweden. Given its strategic position as a protectedport in the developing New World, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>quickly became an economic powerhouse ofproduction and trade. This trend continued throughthe centuries with the population growing from around6,000 in the 1720’s to over 2,000,000 by the 1950’s.However, from 1960 to the present, <strong>Philadelphia</strong>,along with almost every urban area in the UnitedStates, has experienced a significant decline in botheconomy and population. Over that time the city’spopulation has decreased by over 500,000 individuals,with the majority of these residents moving to thesuburbs around the city.One aspect that has greatly facilitated the movementof people out of the city is the ease of travel around thearea. In 1723 Benjamin Franklin traveled from<strong>Philadelphia</strong> to Boston in a journey that took twoweeks by sailing ship. Today, that same journey canbe accomplished in only a few hours using moderntransportation, joining together the NortheastCorridor’s 55,000,000 inhabitants. This same patternof travel ease exists between the city center and thesuburban areas with travel that would have taken twodays to a week accomplished in mere minutes today.This ease of travel has allowed <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’smetropolitan area to expand to over 5,800,000residents over 1,800 square miles.This level of population and development would bebeyond the imagination of William Penn. In hisoriginal idea for <strong>Philadelphia</strong> he envisioned a pastoraltown with a single house on each lot surrounded byorchards, pastures, and fields that sustained theresident, with each lot connected by treed lanes to thetown center. Economic demands and opportunitiesquickly superseded Penn’s vision and the pattern ofdevelopment quickly turned the pastoral landscapeinto that of a growing urban center. This developmentcontinued with the conversion of the forestedlandscape around the town into pastures and fieldsalong with the channelization and damming of thestreams and rivers to provide drinking water andpower mills. As the easily built-upon lands were usedup, more difficult or dangerous areas such asfloodplains, wetlands, and tidal marshes were utilized.The utilization of these spaces was primarilyaccomplished by infilling with material from othersites, such as dirt, rocks, or garbage, until it was stableenough to build upon. This has resulted in asignificant gain of dry land around the city at theexpense of the natural systems that the land supported.At the time of colonization, the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> areacontained between 10 and 20 square miles of tidalmarshland. Today, this area, primarily along theSchuylkill and Delaware Rivers, is utilized forindustrial purposes, public works, and the <strong>Philadelphia</strong>International Airport. This transformation hasseverely affected the aquatic systems that depended onthe tidal marsh for containing floodwaters, filteringwater, and providing habitat for hundreds of species ofbirds, mammals, fish, and herptiles along with anuntold number of plants, insects, and otherinvertebrates. What remains of this system is withinthe John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge, whichmaintains a 200-acre (

Other streams have been locked into undergroundpipes where they cease to function.A similar degradation of most other terrestrial systemsin the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> area has occurred over the lastthree centuries. The forests of the area were veryquickly removed to allow for agriculture, with thelumber used as building material and fuel. And whileno old-growth forest is known within <strong>Philadelphia</strong>,some trees may date from just after the first cutover,with an age in excess of 250 years. The “natural”meadows of the area were also quickly converted toagricultural practices. These environments were mostlikely the result of active management from NativeAmerican tribes burning them on a regular basis toprevent succession to a forested environment. A fewremnant grasslands remain in the city and plans arebeing made to actively manage them to restore theircharacteristic appearance and suite of species.The process of degradation of the natural systemsacross the county has been accelerated by theintroduction of a large variety of non-native invasivespecies. These species, native to other parts of thecontinent or world, were either introducedpurposefully or accidentally, often lack resident peststhat control them, and are not the preferred choice fornative herbivores or predators. This release fromnormal controls allows them to reproduce and spreadat amazingly high rates. The resulting domination ofthe landscape by non-native invasive species reducesoverall biodiversity and the habitat available to nativeplants and animals. This non-native domination isespecially apparent in tracts of unmanaged abandonedlands within the city that are completely dominated bynon-native invasive species.Today, however, the city is presented with unforeseenecological opportunities. The decrease in populationwithin the city, while causing significant economichardship, has made available significant areas of landalong both the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers foreither redevelopment or retirement to parkland or evennative landscapes. This opportunity should not belooked at as an either/or choice. Redevelopment ofthese areas can be accomplished in an economicallyadvantageous and ecologically informed manner,resulting in benefits to the city, the public, thedeveloper, and the environment all at once. Locallyaccessible greenspace is well known to increaseproperty values, and by placing greenspace in areasthat will be the most difficult to develop, developmentcosts and impediment down-time can be reduced.Additionally, greenspaces and natural areas provideeconomic benefits to the community. Tree coverprovides shade, cooling the ground during the heat ofthe summer. This shade reduces the heat island effectcaused by city infrastructure and reduces the energyneeded to cool buildings and people. Plant respiration(especially from trees) cleans the air of pollution andgreenhouse gases, resulting in health benefits foreveryone. The reconnection and reforestation offloodplains can mitigate flooding events and theeconomic costs associated with them, while helping tocool streams and naturally stabilize river banks at thesame time.There are also many social benefits associated withincreased urban greenspace and natural areas.Community greenspace can act as a focal point forcommunity involvement and congregation.Greenspace allows for outdoor recreation andexercise, and greenways can act as transportationcorridors for walkers, joggers, and bikers.An especially important benefit of urban natural areasis the exposure of children to nature. Nature deficitdisorder is a growing area of concern among educatorsand results from children growing up without theopportunity to interact with nature and the outdoors.While the extent and consequences of nature deficitdisorder is still an area of active discussion, providingurban populations with nearby opportunities toexperience nature should be looked at as an importantrequirement for intellectual development and creativegrowth.These opportunities for urban re-greening will befleeting at best. The trend of urban population declineappears to be reversing as economic pressures andopportunities make urban living more and moreattractive. While a population and cultural renaissancein <strong>Philadelphia</strong> can happen on the existinginfrastructure, a green renaissance within <strong>Philadelphia</strong>will need the creation and restoration of new “greeninfrastructure” to provide a natural base to build upon.Questions regarding potential conflicts betweenproposed projects and species of concern mentionedin this report should be directed to an environmentalreview specialist at the Pennsylvania <strong>Natural</strong><strong>Heritage</strong> Program (PNHP) Office in Harrisburg(717) 772-0258.2

NATURAL HISTORY OVERVIEW OF PHILADELPHIAPhysiography and Geology<strong>Philadelphia</strong> lies within three distinct physiographicprovinces (Fig. 2). Different provinces generallysupport different suites of species because of thecharacteristics of the landscape. Thesecharacteristics are based upon the topography andgeologic structure and history of the landscape witha province containing a set of characteristicssignificantly different from the characteristics ofadjacent provinces.of the most productive non-irrigated farmland in theworld. The area around the Morris Arboretum onthe grounds of the University of Pennsylvaniaprovides good examples of what this area lookedlike prior to settlement.Piedmont UplandThe Piedmont Upland province is similar to thePiedmont Lowland in appearance, but very differentin origin. The landscape is still composed of rollinghills around wide valleys, but the hills are somewhattaller and steeper with the streams tending to wanderless in their valleys, such as the area aroundWissahickon Creek. The greatest difference comesin the geologic structure, which is primarily ametamorphic rock called schist that does not havethe absorptive properties or mineral content oflimestone karst. The lowlands of this area alsocontain deep soils that provide excellentopportunities for agriculture, though to a lesserdegree than the Piedmont Lowlands. Thisphysiographic province stretches from near theDelaware River in Bucks <strong>County</strong> to the Adams-YorkCounties line.Atlantic Coastal PlainPiedmont LowlandPhsyiographic ProvincePiedmont LowlandPiedmont UplandAtlantic Coastal PlainFigure 2. Physiographic provinces of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>and surrounding area.Lying on calcareous bedrock, the Piedmont Lowlandis a gently rolling country of low hills and widevalleys that is primarily centered in northernLancaster <strong>County</strong> with arms that extend out to Yorkand Montgomery Counties. The streams of theprovince meander through the broad valleys, but insome areas are completely subterranean because ofthe very porous bedrock (called karst formation).This province contains rich, deep soils that remainmoist throughout most of the year, making it someReferred to as the Lowland and Intermediate UplandSection of the Atlantic Coastal Plain Province, thisarea is characterized by two distinct areas: an upperflat terrace composed of sand and gravel derivedfrom weathered metamorphic rocks, and thefloodplain of the Delaware River, composed of deepalluvial sediments. The sand and gravel of this areaallow for quick drainage to the water table in areasthat are not covered with impermeable surfaces,though a large portion of this province has beendeveloped. This province is dissected by numerousshort, narrow, steep-walled stream valleys in theterrace area that widen out as they enter theDelaware River floodplain. Pennypack Creek is agood example of this, with a much narrower valleyupstream widening out as it approaches theDelaware River. A large portion of this province isnear or at sea level.3