i-xxii Front matter.qxd - Brandeis Institutional Repository

i-xxii Front matter.qxd - Brandeis Institutional Repository

i-xxii Front matter.qxd - Brandeis Institutional Repository

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

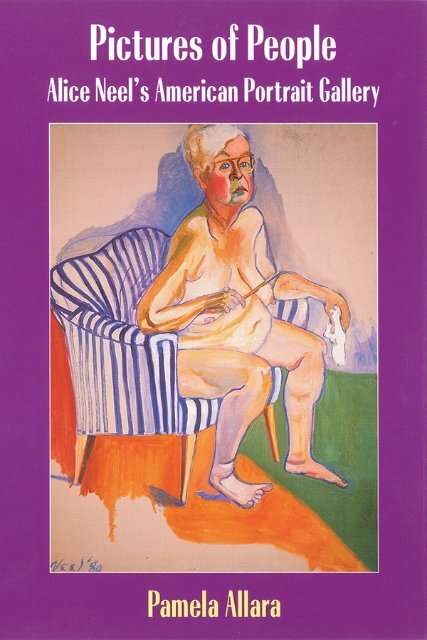

Pictures of PeopleAlice Neel’sAmerican Portrait GalleryPamela Allara<strong>Brandeis</strong> University PressPublished by University Press of New EnglandHanover and London

<strong>Brandeis</strong> University PressPublished by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755© 1998 by the Trustees of <strong>Brandeis</strong> UniversityAll rights reservedPrinted in the United States of AmericaISBN for paperback edition: 978–1–61168–513–8ISBN for ebook edition: 978–1–61168–049–2library of congress cataloging-in-publication dataAllara, Pamela.Pictures of people : Alice Neel’s American portrait gallery / by Pamela Allara.p. cm.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0–87451–837–71. Neel, Alice, 1900– —Criticism and interpretation. 2. United States—Biography—Portraits. I. Neel, Alice, 1900–. II. Title.ND1329.N36A9 1998 97–18403759.13—DC21Throughout this book, “Estate of Alice Neel” includes worksin the collections of Richard Neel, Hartley S. Neel,their respective families, and Neel Arts, Inc.5432

NOTE TO EREADERSAs electronic reproduction rights are unavailable for images appearing inthis book’s print edition, no illustrations are included in this ebook. Readersinterested in seeing the art referenced here should either consult this book’sprint edition or visit an online resource such as aliceneel.com or artstor.org.

CONTENTSillustrations included in the print editionacknowledgmentsixxvIntroduction: The Portrait GalleryxviiPART I: THE SUBJECTS OF THE ARTISTChapter 1: The Creation (of a) Myth 3Chapter 2: From Portraiture to Pictures of People: 13Neel’s Portrait ConventionsChapter 3: Starting Out from Home, 1927–1932 29vii

viii / ContentsPART II: NEEL’S SOCIAL REALIST ART:1933–1981Chapter 4: Art on the Left in the 1930s 45Chapter 5: The Cold War Battles: 1940–1980 67Chapter 6: El Barrio: Portrait of Spanish Harlem 90PART III: THE NEW YORK ART NETWORK:1960–1980Chapter 7: A Gallery of Players: Artist-Critic-Dealer 111Chapter 8: The Women’s Wing: Neel and Feminist Art 127PART IV: THE EXTENDED FAMILYChapter 9: Truth Unveiled: The Portrait Nude 147Chapter 10: Shifting Constellations: The Family (Dis)Membered 162notes 177bibliography 213photography credits 233

ILLUSTRATIONS INCLUDEDIN THE PRINT EDITION<strong>Front</strong>ispiece: Jonathan Brand, Alice NeelFig. 1. Anon., Mae WestFig. 2. Alice Neel, Annie SprinkleFig. 3. Alice Neel, Beggars, HavanaFig. 4. Alice Neel, Woman in Pink Velvet HatFig. 5. Otto Dix, The Journalist Sylvia von HardenFig. 6. Robert Henri, Eva GreenFig. 7. Alice Neel, Two Black Girls (Antonia andCarmen Encarnacion)Fig. 8. Norman Rockwell, Richard Milhous NixonFig. 9. Alice Neel, Sol AlkaitisFig. 10. Alice Neel, Fuller Brush ManFig. 11. Alice Neel, GinnyFig. 12. Alice Neel, Richard in the Era of the CorporationFig. 13. Alice Neel, Benny and Mary Ellen AndrewsFig. 14. Edgar Degas, Edmondo and Therese MorbilliFig. 15. Alice Neel, Bessie BorisFig. 16. Alice Neel, Last Sicknessix

x / Illustrations in the Print EditionFig. 17. Alice Neel, The FamilyFig. 18. Alice Neel, Helen Merrell LyndFig. 19. Anon., “Cross-Section of a Parisian House”Fig. 20. Alice Neel, The IntellectualFig. 21. Alice Neel and Fanya Foss outside of Foss’s GreenwichVillage bookstoreFig. 22. Charles Demuth, Scene after Georges Stabs Himself withthe ScissorsFig. 23. Alice Neel, Well-Baby ClinicFig. 24. Alice Neel, RequiemFig. 25. Edvard Munch, The ScreamFig. 26. Alice Neel, Futility of EffortFig. 27. Alice Neel, Suicidal Ward, Philadelphia General HospitalFig. 28. Alice Neel, Symbols (Doll and Apple)Fig. 29. Alice and Isabetta, February 2, 1929, Sedgwick Avenue,The BronxFig. 30. Frida Kahlo, Henry Ford HospitalFig. 31. Carlos Enriquez, Alice NeelFig. 32. Carlos Enriquez, IsabettaFig. 33. Alice Neel, IsabettaFig. 34. Ben Shahn, The Passion of Sacco and VanzettiFig. 35. Alice Neel, Snow on Cornelia StreetFig. 36. Alice Neel, Uneeda Biscuit StrikeFig. 37. Alice Neel, Nazis Murder JewsFig. 38. Alice Neel, T. B. HarlemFig. 39. Alice Neel, Sam PutnamFig. 40. Anon., Sam Putnam, c. 1933Fig. 41. Alice Neel, Max WhiteFig. 42. Alice Neel, Joe GouldFig. 43. Alice Neel, Joe GouldFig. 44. Alice Neel, Kenneth FearingFig. 45. Alice Neel, Pat WhalenFig. 46. Nahum Tschacbasov, DeportationFig. 47. Alice Neel, Childbirth or, MaternityFig. 48. “Canvases . . . Are Sold for Junk”Fig. 49. Alice Neel, A Quiet Summer’s DayFig. 50. Alice Neel, A Bird in Her HairFig. 51. Alice Neel, Judge MedinaFig. 52. Alice Neel, Angela CalomarisFig. 53. Alice Neel, The Death of Mother BloorFig. 54. Alice Neel, Eisenhower, McCarthy, Dulles

Illustrations in the Print Edition / xiFig. 55.Fig. 56.Fig. 57.Fig. 58.Fig. 59.Fig. 60.Fig. 61.Fig. 62.Fig. 63.Fig. 64.Fig. 65.Fig. 66.Fig. 67.Fig. 68.Fig. 69.Fig. 70.Fig. 71.Fig. 72.Fig. 73.Fig. 74.Fig. 75.Fig. 76.Fig. 77.Fig. 78.Fig. 79.Fig. 80.Fig. 81.Fig. 82.Fig. 83.Fig. 84.Fig. 85.Fig. 86.Fig. 87.Fig. 88.Fig. 89.Fig. 90.Fig. 91.Alice Neel, Save Willie McGee (detail)Shurpin, The Morning of Our FatherlandAlice Neel, SamAlice Neel, SamAlice Neel, Mike GoldAlice Neel, Art ShieldsAlice Neel, Bill McKieAlice Neel, Alice ChildressAlice Neel, Allen GinsbergAlice Neel, Mike Gold, In MemoriamAlice Neel, David GordonAlice Neel, Virgil ThomsonAlice Neel, Jar from SamarkandAlice Neel, The Soyer BrothersLida Moser, Alice Neel and Raphael Soyerat the Graham galleryAlice Neel, Gus HallKomar & Melamid, Stalin in <strong>Front</strong> of a MirrorAlice Neel, Call Me JoeAlice Neel, Fire EscapeAlice Neel, JoséAlice Neel, José (Puerto Rico Libre!)Alice Neel, Alice and JoséAlice Neel, José and GuitarAlice Neel, Puerto Rican Mother and Child(Margarita and Carlitos)Alice Neel, The Spanish FamilyDan Weiner, Morris Levinson, The President of Rival DogFood and His Family Outside Their Home in ScarsdaleAlice Neel, Black Spanish-American FamilyAlice Neel, Richard and HartleyAlice Neel, Two Puerto Rican BoysAlice Neel, Three Puerto Rican GirlsAlice Neel, James Farmer’s Children (Tami andAbbey Farmer)Alice Neel, Georgie ArceAlice Neel, Georgie ArceAlice Neel, Georgie ArceAlice Neel, Ballet DancerAlice Neel, Harold CruseAlice Neel, James Farmer

xii / Illustrations in the Print EditionFig. 92. Alice Neel, Abdul RahmanFig. 93. Edward Hopper, Early Sunday MorningFig. 94. Alice Neel, Fire EscapeFig. 95. “Broader Horizons,” 1920s; advertisement for A. T. & T.Fig. 96. Alice Neel, Rag in WindowFig. 97. Robert Frank, Parade, Hoboken, New JerseyFig. 98. Alice Neel, Sunset in Spanish HarlemFig. 99. Alice Neel, SnowFig. 100. Alice Neel, 107th and BroadwayFig. 101. Alice Neel in Pull My DaisyFig. 102. Alice Neel, Milton Resnick and Pat PasloffFig. 103. Alice Neel, Frank O’Hara, No. 2Fig. 104. Alice Neel, Randall in ExtremisFig. 105. Alice Neel, Hubert CrehanFig. 106. Alice Neel, Walter GutmanFig. 107. Alice Neel, Red Grooms and Mimi Gross, No. 2Fig. 108. Alice Neel, The Family (John Gruen, Jane Wilson, and Julia)Fig. 109. Larry Rivers, O’HaraFig. 110. Alice Neel, Christopher LazareFig. 111. Charles Demuth, Distinguished AirFig. 112. Alice Neel, Paul KuyerFig. 113. Alice Neel, Henry GeldzahlerFig. 114. Alice Neel, Andy WarholFig. 115. Alice Neel, Duane HansonFig. 116. Alice Neel, Robbie TillotsonFig. 117. Alice Neel, Gerard MalangaFig. 118. Alice Neel, Jackie Curtis and Rita RedFig. 119. Alice Neel, David Bourdon and Gregory BattcockFig. 120. Christopher Makos, Andy WarholFig. 121. Alice Neel, John PerreaultFig. 122. Thomas Eakins, Bill Duckett in the Roomsof the Philadelphia Art Students LeagueFig. 123. Alice Neel, Kate MilletFig. 124. Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis)Fig. 125. Alice Neel, Jack BaurFig. 126. Alice Neel, Nancy and the Rubber PlantFig. 127. Alice Neel, Cindy Nemser and ChuckFig. 128. Alice Neel, June BlumFig. 129. Alice Neel, Bella AbzugFig. 130. June Blum, Betty Friedan as the ProphetFig. 131. Alice Neel, Linda Nochlin and Daisy

Illustrations in the Print Edition / xiiiFig. 132. Alice Neel, Portrait of Ellen JohnsonFig. 133. Alice Neel, MarisolFig. 134. Alice Neel, Louise Lieber, SculptorFig. 135. Alice Neel, Mary D. GarrardFig. 136. Alice Neel, Faith RinggoldFig. 137. Alice Neel, Sari DienesFig. 138. Alice Neel, KanuthiaFig. 139. Alice Neel, Self-PortraitFig. 140. Alice Neel, Ethel AshtonFig. 141. Alice and Nadya in Greenwich VillageFig. 142. Alice Neel, Nadya OlyanovaFig. 143. Alice Neel, Nadya NudeFig. 144. Alice Neel, Nadya and NonaFig. 145. Alice Neel, Kenneth DoolittleFig. 146. Alice Neel, Kenneth DoolittleFig. 147. Alice Neel, Kenneth DoolittleFig. 148. Alice Neel, Joie de VivreFig. 149. Alice Neel, untitled (Bathroom Scene)Fig. 150. Alice Neel, AlienationFig. 151. Raphael Soyer, NudeFig. 152. Alice Neel, Pregnant MariaFig. 153. Alice Neel, Blanche Angel PregnantFig. 154. Cover, Ms. magazine, 1972Fig. 155. Alice Neel, Pregnant WomanFig. 156. Alice Neel, Margaret Evans PregnantFig. 157. Edvard Munch, PubertyFig. 158. Alice Neel, HartleyFig. 159. Alice Neel, Drafted NegroFig. 160. Alice Neel, ThanksgivingFig. 161. Alice Neel, Dead FatherFig. 162. Alice Neel, The SeaFig. 163. Alice Neel, Cutglass SeaFig. 164. Alice Neel, Sunset, Riverside DriveFig. 165. Alice Neel, Dr. James DineenFig. 166. Alice Neel, Georgie NeelFig. 167. Alice Neel, Annemarie and GeorgieFig. 168. Alice Neel, The FamilyFig. 169. Alice Neel, Pregnant Julie and AlgisFig. 170. Alice Neel, SubconsciousFig. 171. Alice Neel, The Flight of the MotherFig. 172. Salvador Dali, The Architectonic Angelus of Millet

xiv / Illustrations in the Print EditionFig. 173.Fig. 174.Fig. 175.Fig. 176.Fig. 177.Fig. 178.Fig. 179.Fig. 180.Fig. 181.Fig. 182.John Graham, Head of WomanAlice Neel, Sam and RichardAlice Neel, Richard at Age FiveAlice Neel, MinotaurAlice Neel, PeggyAlice Neel, LonelinessAlice Neel, Mother and Child (Nancy and Olivia)Alice Neel, Nancy and VictoriaAlice Neel, Nancy and the Twins (5 months)Alice Neel, The Family

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis project began while I was teaching at Tufts University, and for their helpwith organizing the exhibition Exterior/Interior: Alice Neel, I thank my colleaguesthere: Erika Ketelhohn, then acting curator at the Tufts University ArtGallery, Elizabeth Wylie, the gallery director, Chris Cavalier, Fine Arts Departmentphotographer, and my graduate research assistants Nancy Chute,Renata Hedjuk, and Catherine Mayes. I also thank Prof. Margaret HendersonFloyd for her continuing support of my research.At <strong>Brandeis</strong> University, I received the Mazer Grant for Faculty Researchand the Marver and Sheva Bernstein Faculty Fellowship for a semester’s leaveto complete the manuscript. Among my colleagues at <strong>Brandeis</strong>, Nancy Scottin the Fine Arts Department and Erika Harth in the Romance Languages Departmenthave provided helpful critiques of my arguments. Kathryn Hamill, agraduate student at Massachusetts College of Art, helped to compile sitters’ biographies.My student Sarah Shatz has been an invaluable help in all phases ofthe manuscript preparation.The research for this book was completed under a senior postdoctoral fellowshipat the Research and Scholars Center of the National Museum of AmericanArt, Smithsonian Institution, where I received valued imput from curaxv

xvi / Acknowledgmentstors Virginia Mecklenburg and Harry Rand, as well as from Judy Throm, chiefarchivist for the Archives of American Art, and Carolyn K. Carr, deputy directorof the National Portrait Gallery. A number of colleagues in the ƒeld havekindly read and commented on speciƒc sections of this book, and I would liketo thank in particular Patricia Hills, Susan Platt, Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt,Mary Garrard, Andrew Hemingway, Juan Martinez, and Trevor Fairbrother.I am especially grateful to my friend and colleague in the Fine ArtsDepartment at <strong>Brandeis</strong>, Prof. Lynette Bosch, for patiently reading and commentingon all of the initial drafts.Among those people who consented to be interviewed for the book, MayStevens, Rudolf Baranik, Margaret Belcher, Philip Bonosky, and Peggy Brookshave been especially generous with their time and information. Central to theentire project, of course, has been the Neel Family—Neel’s sons, Richard andHartley, and her daughter-in-law Nancy. Nancy was invaluable as Neel’s assistantduring the artist’s lifetime, and my gratitude for her un„agging assistanceon this project could never be adequately acknowledged. Adam Sheffer andthe staff at the Robert Miller Gallery has also been unfailingly helpful in providinginformation and reproductions. John Cheim, at the Cheim and ReadGallery, was especially supportive in the early phases of this project.John Hose, executive assistant to the president of <strong>Brandeis</strong> and governor ofthe <strong>Brandeis</strong> University Press, has guided the manuscript through to publicationwith consummate professionalism. To Paul Schnee, formerly at the UniversityPress of New England, and Phyllis Deutsch, who took over the project,I give thanks for insightful editorial comment.Finally I thank my family, especially my grown children Mark and AnnMarie, for their love and support. This book is dedicated to the memory of mylate husband, Michael.P.A.

IntroductionThe Portrait GalleryAlice Neel made her ƒrst mature paintings in 1927 and continued paintinguntil her death in 1984. A realist whose primary genre was portraiture, she consideredherself fortunate to have been active from the early to the late twentiethcentury and to have recorded the changes and continuities within thatspan of time as they were registered in the faces and bodies of her sitters. In1960, she described herself as a collector of souls, a phrase ground into a clichéby critics in the 1970s. But because her work did not begin to sell until she waspast seventy, she was most certainly a collector of her own work; her sittersmaintained their presence in her apartment long after their physical departure.Her home was thus a portrait gallery of vivid likenesses stacked togetherlike geological strata marking the various “epochs” of the century. I have chosenthe portrait gallery as the dominant metaphor for this thematic discussionof Neel’s work because it suggests the collective, historical nature of her art.However, this public monument is the product of an idiosyncratic, individualvision.Cumulatively, Neel’s paintings of people provide an artist’s interpretation ofsigniƒcant social, political, and intellectual trends in twentieth-century Americanculture, as exempliƒed by three overlapping populations in New York City:the left-wing artists and political activists in Greenwich Village during the Dexvii

xviii / Pictures of Peoplepression, the residents of Spanish Harlem during the McCarthy era, and theNew York artworld during the social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s. Herportrait gallery is a personal chronicle, a means of deƒning her life in terms ofthe people who entered it, a necessarily contingent sample of American culture.A visual novel, Neel’s multilayered narrative is held together by the consistentthread of her family life. In the course of seeking answers to her centralinvestigation of the parameters of personal identity at a given moment, Neelneglected few disputed terrains of American culture in her art—whether ofrace, class, or sex.Her sprawling gallery, some three thousand works long, was a means of freezinglife’s „ux in order to acknowledge the potential signiƒcance of even themost trivial or „eeting of human interactions. “Every person is a new universeunique with its own laws emphasizing some belief or phase of life immersed intime and rapidly passing by,” 1 Neel said. She examined any and all evidencefor what it might yield; for as a con„uence of history’s forces, no person couldbe uninteresting or insigniƒcant. Only a small proportion of her sitters belongedto the artistic elite who made lasting creative contributions to Americancultural life; the rest she rescued for history simply by recording their visagesas witnesses to their time.Neel referred to herself as an old-fashioned painter of portraits, still lifes,and landscapes. It was not merely her realistic subject <strong>matter</strong> that can be consideredanachronistic, however. In an age of mechanical reproduction, Neelused the medium of oil paint rather than photography to make her portraits. Inan era of mass communication, she made objects that had virtually no audienceat the time and have only a very limited audience today. A realist in theage of modernism, Neel based her efforts on the faith that her representationswould be consonant with an external reality. She held to realism’s fundamentaltenet that painting’s function was to mirror or re„ect reality, and because inher view individuals best re„ected the age, portraiture was the most appropriategenre for her realist art. Neel’s contribution to American art history wasthus not formal innovation but rather her ability to use a genre that was consideredexhausted and to invest it with renewed relevance. Because these subjectswere tied to the speciƒc instance—poverty as an Hispanic male suffering fromdisease, pregnancy as the physical discomfort and anxiety of a white woman—Neel’s realism claimed by implication a documentary authority. The daringwith which she poured new wine into old bottles has given me permission tolink old-fashioned content analysis with cultural history. To address the work, toanalyze what appears there, and then to open it out to the larger cultural patternof which it is a piece is to initiate a process that I believe parallels Neel’s own.Neel provided her own pedigree for her approach. The model to which shereferred continually in her lectures was Honoré de Balzac’s Comédie Humaine:

Introduction: The Portrait Gallery / xix“That’s really what life is—The Human Comedy. And put together, that’s whatmy paintings are.” 2 If this nineteenth-century French novelist seems a ratherremote point of origin, Neel, in referencing Balzac, located her own positionwithin the spectrum of American cultural life. In the late 1920s and early1930s, when Neel’s aesthetic ideas were being formulated, Balzac was cited inbroad terms as a precedent for a socially concerned art by radical writers. Neel’sadmiration for Balzac is indicative not simply of her personal taste but of theliterary criticism of the period. With Georg Lukacs, for instance, she wouldhave insisted that realist art, to properly depict the “forces” of history, must beabout “individuals and individual destinies.”During the 1930s, the signiƒcance of popular culture as the artistic expressionof the masses was also recognized. An interest in the study and exhibitionof folk art, for instance, was paralleled by an interest in the oral traditions of theworking class. Neel’s visual history, like the oral histories collected by the FederalWriter’s Project of the Works Progress Administration, served as a voice forthose segments of society unacknowledged in previous histories. This approachentered mainstream historical writing during the 1970s. As the Italianhistorian Carlo Ginzburg wrote in his Preface to the Cheese and the Worms(1976):In the past historians could be accused of wanting to know only about the greatdeeds of kings, but today this is certainly no longer true. More and more they areturning toward what their predecessors passed over in silence, discarded, or simplyignored. “Who built Thebes of the seven gates?” Bertolt Brecht’s “literate worker”was already asking . . . The sources tell us nothing about these anonymous masons,but the question retains all its signiƒcance . . . [W]e have come to recognize thatthose who were once paternalistically described as “the common people in a civilizedsociety” in fact possessed a culture of their own . . . Even today the culture ofthe subordinate class is largely oral. 3The portrait, however anachronistic it seemed as a genre to Neel’s own contemporaries,is in fact ideally suited to a project modeled on oral history. Weare introduced to individuals, one on one, and to their history as told to a narrator/translator.Visualizing history as it is embodied in people who at one andthe same time may be academics and revolutionaries, Black Muslims and taxidrivers, is a means of understanding it as shaped by human action rather thanby abstract forces.As a woman artist working in the retrograde medium of portraiture, Neeloccupied a marginalized position in the New York artworld, a position replicatedin her living and family arrangements. In order to pursue a professionalcareer, the artist fashioned herself as a rebel, adapting the pre-existing persona

xx / Pictures of Peopleof the bawdy woman in order to “create her own world” rather than replicatingexisting social constructs. Her antisocial behavior created the autonomy ordistance necessary for her cultural critique. Alone in her own domain (herhome and the genre of portraiture), she could create a body of work that by remainingon the periphery could lay claim to the avant-garde tradition withinmodernism.Because I believe that Neel’s working method and its premises were inseparablefrom the product, I have tried to organize this text in a manner thatwould be faithful to her method. I conceive of her method, her modus operandi,as piecework. Neel did not start from a grand design; rather, she startedfrom what was available, at hand, lodging the work in the proximate. Picturesof People is also piecework, constructed from thematic blocks: radical politics,the artworld, and the family. The historian cannot move from the work to theartist “behind” it, as that being is so clearly a construct. The Neel referred to inthis text is not, then, Neel the person, whom I never met. “Neel” is an inferencemade from the work, and built from the visual evidence it offers. I havechosen a thematic rather than a chronological approach because, althoughthreaded into the New York artworld from 1927 to 1984, Neel’s art was inmany ways out of its time. As I have put it together, Neel’s art is both antiquatedand prophetic, drawing from nineteenth-century realism while anticipatingmany of the concerns of feminist art of the 1970s. The umbrella of culturalhistory has provided the space to examine literary as well as visual parallels inorder to substantiate my argument that Neel was not alone in her thinking,and that comparable critiques can be found in the artists and writers who wereher peers.In using the metaphor of the portrait gallery, I have deliberately differentiatedNeel’s painting from other works of high art destined for a museum. In anart museum, the portrait is important only as an example of a famous artist’swork. Within the art museum world, the portrait gallery’s status is compromisedby its valuation of the historical importance of the portrait’s sitter overthe painting’s “aesthetic” qualities. Neel’s portrait gallery is her world and theviewer acknowledges each painting as “a Neel,” but the viewer is also chargedwith identifying the sitter, if not speciƒcally, at least as a product of a given era.In asking “who is it?” we must frame the answer in terms of what the subjecttells us about his or her history, and, by extension, that of American culture.The portrait gallery permits the viewer to question the scheme of things, toview the individual in and as history. Neel’s accumulative approach, one plusone, becomes for the viewer a one on one, an imaginary conversation.The result of this conversation is a metaphor created by relating personalityto historical context. Neel’s approach required that she remain open to theinterpretive possibilities of each generation’s dress and pose. The individual

Introduction: The Portrait Gallery / <strong>xxii</strong>n/as history represents a con„uence of constantly shifting and changingforces, without a stable continuity provided by specious “bloodlines” or questionable“great deeds.” But because each portrait is a synecdoche, the part substitutingfor the whole, the viewer must recreate, however provisionally, thehistorical situation the portrait represents. According to George Lakoff, the“[m]etaphorical imagination is a crucial skill in creating rapport and in communicatingthe nature of unshared experience. This skill consists, in largemeasure, of the ability to bend your world view and adjust the way you categorizeexperience.” 4 Neel was a feminist and a political radical, but her abilityto grow artistically over a period of a half century was tied to her openness toexchange.Like all great portrait artists, Neel’s pictures create the compelling illusionof a human presence. Her metaphors are not abstractions. In his essay on metaphor,Paul Ricoeur quotes Aristotle: “The vividness of . . . good metaphorsconsists in their ability to ‘set before the eyes’ the sense that they display.” 5 Justas the mind makes metaphors on the basis of embodied experience, so Neel’sportraits are metaphors for a concept of identity that is characterized by a continualtraversing of boundaries between public and private, interior and exterior.Her vivid portrayals help us to see American cultural history from varyingperspectives. The individual was her focus, but framing her vision as shepainted was the person’s place on the social ladder and in the historical moment.These deƒning terms, these frames of reference, were never absent fromNeel’s “peripheral” vision. Her portraits open out in many directions: to culturalconcerns as expressed in literature, politics, and visual art. All of thesewill overlap in this text to create a broad-based reading.

Part IThe Subjects of the Artist

1The Creation (of a) MythI lived in the little town of Colwyn, Pennsylvania, where everything happened, butthere was no artist and no writer. We lived on a street that had been a pear orchard.And it was utterly beautiful in the spring, but there was no artist to paint it.And once a man exposed himself at a window, but there was no writer to write it.The grocer’s wife committed suicide after the grocer died, but there was no writerto write that. There was no culture there. I hated that little town. I just despised it.And in the summer I used to sit on the porch and try to keep my blood from circulating.That’s why my own kids had a much better life than I had. Because boredomwas what killed me.Thus opens “Alice by Alice,” Alice Neel’s autobiography, published the yearbefore she died. 1 Neel was a painter: her strong visual sense pervades herspeech. In her old age, the images from her childhood, indelibly painted inher mind, carried with them all of the emotional weight of their initial impression.Colwyn, Pennsylvania was a sight, but there was no one there to record itsbeauty or its perversity. Neel’s words suggest that as a child she knew that shehad to become an artist in order to record that life in all its aspects. But ofcourse, these are the words of an adult at the end of a long and productive artisticcareer. In the manner of any good storyteller, Neel has created a parable to3

4 / The Subjects of the Artistexplain her choice of an artistic vocation and to justify the direction it wouldtake.Like many American women artists, Alice Neel (1900–1984) painted in relativeobscurity for many years before achieving artistic prominence in the1970s. During that time, she began to compensate for the years of artistic neglectby crisscrossing the United States to deliver slide lectures on her work. Awitty and intelligent woman, Neel developed an enthusiastic following, eachlecture spawning new invitations. The cumulative effect of these popular lectureswas that her art was and continues to be accepted as she presented it: asan illustration of her life, as extended autobiography.The art historian, however, is bound to ask what place Neel’s art occupiesin American art and culture. I will argue that Neel’s work presents a paradigmof the course of socially concerned art in the twentieth century. We mustexamine the anecdotal version of Neel for what it is: a particular instance ofthe complex relationship between art and biography that troubles any monographicstudy of an artist’s work. My objection to a biographical approach toher work, which she instigated as a means of bringing her art to the widest possibleaudience, is not that the account of her life is untrue—it is not any moreor less “true” than any biography—but that it has obscured her work.Trained at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women from 1920 to1925, Neel aligned herself with the Ashcan School artists of the previous generationand with the legacy of the unsparing depiction of urban life establishedin Philadephia by its founders, Robert Henri and John Sloan. Neel took theAshcan School’s premises literally. Her nascent interest in a socially concernedart was reinforced by the year she spent in Havana (1925–1926) with the earlymembers of the Cuban avant-garde.During the 1930s, while living in Greenwich Village, Neel participated inthe WPA’s programs, joined the Communist Party, and was strongly in„uencedby the communist call for a proletarian art. However, as a portrait painter,she only occasionally peopled her art-for-the-millions with the masses. Instead,she insisted on depicting each representative of a given class as an individualand, in doing so, created an alternative version of social realism. A basic assumptionof the work is that the quotidian reality of twentieth-century Americansof all classes was centered in family life. There, Neel identiƒed such physicaland psychological consequences of poverty as disease and child abuse,recording them long before they were thought to be germane to an activist art.After World War II, when she had settled with her two sons in SpanishHarlem, Neel retained her realist style, resisting the centrist political forcesthat were branding it as anachronistic. Not only did her portraits from theseyears redeƒne the notion of family, but they also reconƒgured urban space interms of the experiences of those in poverty. By the early 1960s, having moved

The Creation (of a) Myth / 5to 107th Street on the Upper West Side, the two worlds that had intersected inher art, the creative and intellectual on the one hand and the marginalizedand impoverished on the other, began to diverge. She subsequently concentratedalmost exclusively on her own family and on members of the New Yorkartworld. Nonetheless the core of her artistic philosophy—her belief that anindividual’s body posture and physiognomy not only revealed personal idiosyncracies,but embodied the character of an era—remained unchanged.Neel’s career and the critical reception of her work—painting in her homewithout institutional recognition—are representative of the situation of manywomen artists and part of a cultural pattern of devaluating women’s work.When broken, this pattern has often resulted in the overcompensation of adulation.Yet the critical extremes of the darkness of obscurity and the glare ofpublicity can hardly be expected to shed an even light on an artist’s work, asNeel’s career attests. Between 1926 and 1962, she was given six one-persongallery exhibitions; between 1962 and her death in 1984, she had sixty. Publishedreviews and articles also increased exponentially, but remained biographicallybased.Just as the career trajectory of women artists in the twentieth century hasbeen a belated and dizzying climb from the valleys of obscurity to the peaks offame, so too the critical reception of their work has been based on the anachronisticassumption that art by men explains the world, whereas art by womenexplains their life. Neel’s lectures served to reinforce that familiar cliché. Forexample, in her 1989 essay “Tough Choices: Becoming a Woman Artist, 1900–1970,” art historian Ellen Landau found the careers of the ƒrst generation ofwomen modernist artists to be marked by emotional con„ict. Enumeratingtheir psychological problems—their suicide attempts, alcoholism, and depressions—Landauimplies that their personal difƒculties were due to the con„ictsthe women experienced between their desire to be mothers and to be artists;their careers thus present a “pattern whose implications should not be ignored. . . Work was not always enough to satisfy these women, and it often took ahigh psychic toll.” 2 Without question the con„icts of motherhood and careerexacted a high toll from many artists, including Neel, but it does not followthat art making was unrewarding without the compensating fulƒllment of familylife. Perhaps the lack of support they received in trying to balance careerand motherhood was a cause of stress, or, again, a lifetime of personally rewardinglabor that remained unrecognized.In 1958, Neel recognized that, if her art were to enter history, she would notonly have to create it but participate in developing its audience. During theƒfties, close friends who were also frustrated by the critical neglect of her workencouraged her to develop a slide presentation. One of her ƒrst venues was theWestchester Community Center in White Plains, where she spoke to an art

6 / The Subjects of the Artistclass at the invitation of another friend, the socially concerned painter RudolfBaranik. Beyond their ready wit and broad range of knowledge, Neel’s lecturesconsistently beguiled their audience with the contrast between her grandmotherlyappearance and her provocative language. With the arrival of theWomen’s Movement in the late 1960s, Neel was constantly in demand.Driven by the desire to bring her art to the public, Neel appeared at almostevery one of the openings of her solo exhibitions, no <strong>matter</strong> how remote theirlocation, and invariably her lecture would be part of the opening night festivities.Her artistic reputation thus became inextricably bound up with her talks,and unfortunately the journalistic press, sensing the broad popular appeal ofa juicy life story, enthusiastically bought into it, adding their own decorative„ourishes.The format of the newspaper and magazine articles on Neel forms an unvaryinglitany into which passing reference to her work is made to ƒt. The ƒrstfew paragraphs invariably contain a sexist description of Neel’s grandmotherlyappearance and its con„ict with her “unladylike” personality:Alice Neel is like an old pagan priestess somehow overlooked in the triumph of anew religion. Indeed, with her shrewdly cherubic face, her witty and wizard eyes,she has the mischievous look of a maternal witch whose only harm lies in her compulsionto tell the truth. (Jack Kroll, Newsweek, 1966)Seated in front of a [canvas] in her blue smock, her bright little green eyes squintingand blinking behind her glasses, her plump legs spread forcefully apart and herspace-shoed feet planted solidly on the „oor, she picked up her brush gingerly andwailed, “I’m just scared to death . . .” While she formed our torsos . . . she chatteredon incessantly . . . but when she came to our faces, she became transformed; herface became ecstatic, her mouth hung open, her eyes were glazed and she neveruttered a word. (Cindy Nemser, catalog essay, Georgia Museum of Art, 1975)Such patronizing descriptions are the content of a newspaper’s “Living”pages, to which the reviews of Neel’s work were frequently relegated. Althoughsuch extended attention to physical appearance is unlikely to be found in thecritical discussion of art by men, the cliché of the creative artist who is seizedwith “ecstasy” while painting is as old as art history itself. Its relentless repetitionin the literature on Neel revives that stereotype for the purpose of establishinga myth of origins for the women’s movement. Such a myth, of course,requires a narrative of triumph against all odds. The highlights of Neel’s genuinelydifƒcult life story inevitably followed the journalist’s establishment ofthe persona: The hypersensitive child in a parochial Philadelphia suburb;marriage to an “exotic” Cuban artist, Carlos Enríquez de Gomez (1925); the

The Creation (of a) Myth / 7death of their ƒrst child, Santillana (1927); the break-up of their marriage andloss of custody of their second child, Isabetta, followed shortly therafter by anervous breakdown (1930); the post-recovery move to the bohemian world ofGreenwich village (1931); the destruction of over 300 of her paintings and watercolorsby her jealous lover, Kenneth Doolittle (1934); the move, with José,to Spanish Harlem, where her two sons, Richard (1939) and Hartley (1941),were born; years of poverty in Spanish Harlem (1939–1962); the beginnings ofher own professional success as her sons entered their careers; and ƒnally,fame, and ƒnancial and critical success (1974–1984).This narrative, repeated in all of the newspaper reviews of her exhibitions,culminated in Patricia Hills’s judiciously edited autobiography from 1983. AliceNeel is Neel’s life as she wanted it told, the grand summation of her lecturesand interviews. Indeed, it reads like a psychological novel of the 1930s such asher friend Millen Brand would have written. Lively and engaging, the book isa testimony to Neel’s prodigious and vivid memory for people and events, andto her exceptional storytelling abilities. Her life’s traumas are not at all irrelevantto her artwork, but it is important to recognize that Neel was fashioningthe recounting of her life as if it were a piece of ƒction. In a true stroke of “genius,”she did not write her own autobiography, even though she was a ƒnewriter; she let others use the material she supplied in interviews to write it forher, so that the recounting conveyed a sense of objectivity.Yet, the traumatic events thus transcribed can help elucidate her art onlywhen lodged in the social and intellectual milieu of which she was a part, asLawrence Alloway noted in his review of Hills’s book in Art Journal:In Patricia Hills’ Alice Neel . . . the hand of the artist seems a bit heavy to me. Thebulk of the book, “Alice By Alice” . . . is the artist’s oral history of herself, and Hills ispresent only as the author of an eight-page, unillustrated Afterword. This disparitywould <strong>matter</strong> less if a solid core of critical discussion on Neel had already existed,or if her monologue were more interesting. Anyone who has heard the artist’s garrulouslectures will recognize many of the anecdotes printed here . . . [T]he artistshould have realized that if she is to move off the lecture circuit and enter art history,the cooperation of people like Hills should not be abused. 3The anecdotes and observations so familiar from Neel’s lectures are bestunderstood in their art historical context, where they provide clues to thesources of her intellectual development. Although isolated in terms of herexclusion from exhibitions, she was highly visually and critically literate. Althoughshe professed disinterest in other artists and used her lectures as a vehiclefor reinforcing the notion that her art stemmed directly from her personallife rather than from any outside in„uence, her extensive knowledge of art andliterature permitted her to forge her art from a very broad base.

8 / The Subjects of the ArtistThe role Neel’s lectures and interviews played in the creation of a myth ofher life story is hardly exceptional. Art in general, and the artistic personality inparticular, have always been bound up with mythmaking. If Neel understoodthat a successful career would have to involve the “marketing” of a public personality,from which sources did she create her artistic persona? In this area,Neel, like other women artists, would have lacked role models. Women artistshave endured strong social pressure to construct their identity as “female,” toemphasize their womanliness despite their artistic talent. Yet without an image,an artist lacks substance. Without a myth, no fame validates one’s art. Womenartists have long understood that these strictures against unconventional behaviorhave served as a means of assuring that women would never fully be acceptedas artists. Because the breaking of rules of social behavior has been consideredsince the Renaissance to be a means of freeing oneself from outmodedartistic conventions, then women’s acceptance of conventional roles wouldperforce constrain the creative impulse. Virginia Woolf’s need to kill “TheAngel in the House”—the domestic self that is required to be sympathetic,charming, self-sacriƒcing—in order to become an effective writer has by nowbecome a feminist truism. During the 1920s, when Neel came of age, theAmerican poet Louise Bogan described the repercussion of women’s socializationas docile dependents: “Women have no wildness in them, / They areprovident instead, / Content in the tight hot cell of their hearts, / To eat dustybread.” Neel’s writing during this decade reveals that she had adopted thisfeminist view: “Oh, the men, the men, they put all their troubles into beautifulverses. But the women, poor fools, they grumbled and complained andwatched their breasts grow „atter and more wrinkled. Grey hair over a greydishcloth ...” 4 In her lecture at Bloomsburg State College in 1972, Neel putit even more directly. “In the beginning, I much preferred men to women.For one thing I felt that women represented a dreary way of life always helpinga man and never performing themselves, whereas I wanted to be the artistmyself!” 5Although one can hardly hope to assess the effect of Neel’s nervous breakdownat age twenty-nine on the subsequent course of her art and career, biographicalaccounts by Marcelo Pogolotti, the Belchers, and others suggest achange from a rather naive if rebellious young woman to a conƒrmed bohemian.6 After her total collapse, Neel adopted a stance of resolute oppositionto virtually everything that smacked of middle-class propriety or politics. Shecould have returned to her parents’ home to complete her recovery but choseinstead to summer in New Jersey with her friend Nadya Olyanova, throughwhom she had met Kenneth Doolittle. When, at the end of the summer, shemoved to Greenwich Village to live with the drug-addicted seaman who, as amember of the IWW, was also left-wing, Neel claimed citizenship in a “coun-

The Creation (of a) Myth / 9try” that John Sloan and Marcel Duchamp had once mockingly declared hadseceded from the United States. Although the Greenwich Village of the early1930s had lost the revolutionary fervor of the prewar years, it remained the locusof alternative life-styles as well as of much important creative activity. Theutopian visions of a socialist activist like Polly Holliday may have been replacedby the barbed commentary of the essayist Dorothy Parker; nonethelessthe Bohemia of Greenwich Village could still be counted on to remain a thornin the side of polite society.The artistic and literary example of New York’s bohemia in these years providedrather „imsy material on which to construct an identity, however. Neelcame to maturity during the great age of ƒlm, and as Robert Sklar has observed,many men and women learned about social relations, and male-female relationshipsin particular, from what they saw on the screen. A prototype enjoyingwide popularity in media culture—the bawdy comedic type personiƒed by MaeWest—may have provided the most compelling topos for the construction ofNeel’s persona.Although the stereotypical virgin-whore opposition that dominated ƒn-desiècleart was perpetuated in the roles played by early ƒlm stars such as LillianGish and Theda Bara, a ƒgure such as Mae West could irreverently mock theentire system with her outrageous screen behavior (ƒg. 1). Aggressive and loudmouthed,but with her hair dyed platinum and her hourglass ƒgure swathed insequined gowns, West was part temptress, part truck driver. Like the transvestiteshe appeared to be, she could at once play and parody female sex roles.Perhaps for males, her homeliness and sexual ambiguity allowed them tolaugh at her jokes without feeling threatened by her professed voracious sexualappetite, but for women, her lack of concern for male opinions or approbationmust have provoked a different kind of awe. Here was a woman whose dedicationto her own sensual pleasure was so strong that she would refuse to conƒneherself by giving her hand in marriage to even the most cinematically desirablescreen bachelor. For young women, including Neel, who watched her asthey reached the age of consent, West offered the possibility of saying “no” tosociety’s expectations by insisting on putting her own needs ƒrst.According to June Sochen, bawdy comediennes such as Mae West andvaudevillian Eva Tanguay used bathroom humor and sexual jokes to takethe Eve image and turn it around; no longer was woman’s sexuality viewed as evil. . . They also displayed, as all iconoclasts do, a marked irreverence for sacred subjects.Nothing was out of bounds. No gesture, no thought, no action had to be selfcensoredor controlled . . . The female rebel performer would not ever becomea comfortable part of popular culture because she was too avant-garde, too outrageousin her words and actions. 7

10 / The Subjects of the ArtistBecause such sexual freedom has long been the purview of the male avantgardeartist, Neel could easily have linked the two realms—high art and popularculture—in terms of image making. Both aimed to épater les bourgeois, themiddle-class consumer, providing the common ground for West’s irreverentwit and that of the artistic avant-garde. Neel’s outrageous stories, then, weregeared to adding lustre to her role as the quintessential bohemian. Neel wantedto perform—Neel wanted to be the artist, and so at the end of her life she performedher life and art. 8By using bawdy humor to reduce the powerful and the famous to the basestcommon denominator, Neel’s naughtiness demystiƒed the artworld’s elites,thereby also pointedly rebuking those who for so long ignored her work. Theedge to Neel’s humor, like West’s, stemmed ultimately from anger—her mockinglaughter and outrageous language perhaps the only effective means for expressinggenuine outrage and exposing the artiƒciality, if not the devastatingpsychological consequences, of the conventional constructs of woman and ofartist.Her lecture at Harvard University’s “Learning From Performers” series atthe Carpenter Center on March 21, 1979, exempliƒes her ƒne-tuned presentations,and although her humor is considerably dulled in my summary, her violationof every rule of feminine decorum should be evident. Her chronologicalsurvey began with her early training at the Philadelphia School of Designfor Women. She went on to express her disdain for many of the in„uential realistpainters of her generation, for example the Art Students League’s EugeneSpeicher and his “cow-like women.” Having summarily dismissed the artisticcontext in which she worked, she began a chronological sequence of slides ofher work. When she came to her Ethel Ashton of 1930, herself a bovine womanprofoundly ashamed of her naked body, she asked the audience to “look at allthat furniture she is carrying around.” With reference to Nadya and the Wolf(1931), Neel claimed that her friend, the handwriting expert, could not havechildren because “she used drugs for douches,” while her portrait of NadyaNude could not be photographed because in 1933 “you could not make a slideof pubic hair.” Symbols (Doll and Apple), one of the artist’s most wrenchingworks, is described as “sexy,” and the outrageous triple genitals in the 1933 portraitof Joe Gould “look like St. Basil’s domes upside down.” 9 Near the end ofthe Harvard lecture, when she showed her double portrait of the artists RedGrooms and Mimi Gross, and described Grooms as “ready to jump up andperform,” she openly acknowledged her belief that contemporary artists had ofnecessity become “performers.” 10Neel was far from the only female artist-rebel of her generation, but she wasone of only a few who rebelled through both an unconventional life-style and a

The Creation (of a) Myth / 11biting wit, actions and words that indicated an absence of self-censorship, a determinationto disrupt polite society. Neel joins the ranks of those writers andpainters—among them Gertrude Stein, Mabel Dodge Luhan, and RomaineBrooks—who ignored their physical appearance and/or permitted themselvesthe comfort and convenience of male garb. It was not until the 1970s thatNeel’s unfashionable persona was adopted by younger feminist performanceartists. Annie Sprinkle (ƒg. 2), whom Neel painted in 1982, pushed the MaeWest image even further toward outrageous camp, which Neel captured perfectlyin Sprinkle’s blowsy expression, tacky feathered hat, overblown breasts,and pussy ring. Flaunting sexuality was the means for all three women to gaincreative as well as economic autonomy. By refusing sexual subservience, theybecame sufƒciently threatening to be let alone, and perhaps to gain a grudgingrespect. In a culture that restricted women’s options, the strategy worked.Much as Neel’s autobiography has obscured her art, it is essential to it andinextricable from it. Were it not for her efforts to narrate her life, her workmight have remained unknown. She realized this when she was in her ƒfties,and spent the rest of her life insuring that her work would not be lost to history.“When Sleeping Beauty wakes up / she is almost ƒfty years old,” 11 wrote poetMaxine Kumin, brilliantly pinpointing the moment when many women realizethat a passive life is a lost life. To conserve her transgressive art, created atgreat emotional cost, she had to translate it into another medium, whose formwould make clear how „agrantly she had violated the unspoken rules of theappropriate in realist art and in real life. According to the feminist psychologistNancy K. Miller, “To justify an unorthodox life by writing about it is to reinscribethe original violation, to reviolate masculine turf.” 12Neel’s lectures were part of her battle to secure a well-earned piece of arthistorical turf. Having recognized the futility of waiting passively for recognition,Neel admitted to Hills in 1983 that she had had “a block, I still have it,against publicity . . . I reached the conclusion that if I painted a good picture, itwas enough to paint a good picture . . . I didn’t know how to go-get, so I just putit on the shelf.” 13 In her ƒfties, after her children were in college, Neel tookcharge. Although hardly a wall„ower previously, she was now ofƒcially off theshelf. In Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn Heilbrun has identiƒed this “awakening”as the key moment in a woman’s artistic career: “[A] woman’s selfhood,the right to her own story, depends upon her ‘ability to act in the public domain.’”14To take one’s life into the public domain, one must write it as narrative.Neel chose the genre of satire, the female equivalent of modernist irony. Yet itis important to remember that Neel “wrote” her long life well after she had begunto paint it. She created her autobiography twice, with the later version di-

12 / The Subjects of the Artistrected toward popular consumption, and the creation of a market and a publicspace for efforts long conƒned to her studio/home. Her talents as a raconteurput her work into the public domain. The art historian’s task is to situate itwithin the matrix of American culture.

2From Portraiture to Pictures of People:Neel’s Portrait ConventionsThe Portrait TraditionThe career obstacles Neel faced as a woman in the artworld were compoundedby her choice of genre: portraiture. Just as Neel had to create an artistic personathat would bring her work into the public realm, so, basing her art in the representationof the human ƒgure, she had to rethink the outworn conventionsof the genre and to provide it with renewed relevance to modernist artisticpractice. One route, taken by artists such as Andy Warhol and Philip Pearlsteinafter 1960, would have been to invert the premises of the tradition of selfportraitureas expressive of personal identity and to question the very existenceof a private realm. Neel’s art remained rooted in the modernist faith that theportrait could represent individual psychology, but she revitalized the legacyof psychological portraiture from Degas to van Gogh by reinvesting it with itssocial and political aspects. Both her work and her words indicate that RobertHenri’s The Art Spirit served as an important source of ideas that remainedfundamental to her concept of portraiture as metaphor. By analyzing the conventionsshe developed to elaborate the metaphorical dimension of the portrait,it will be possible to understand the means she used to create an image ofan individual qua era.13

14 / The Subjects of the ArtistIt is a truism that after the invention of photography in 1839 portrait paintinglost much of its raison d’être and nearly all of its prestige. Painters who specializedin ofƒcial portraiture and who worked for ƒrms such as Portraits, Inc.,were excluded from serious consideration as artists. In turn, artists who did notmake portraits for hire but whose work consisted primarily of portraiture werefound guilty of commercialism by association, and their reputations suffered.By the mid-1950s, American critics had declared the tradition of portrait paintingdead. Writing in Reality magazine in 1955, the social realist painter GeorgeBiddle lamented: “Yes, portrait painting as an art—rather than as a debasedform of chromolithography—is very nearly a lost tradition.” 1 Four years later,at the height of abstract expressionism, Frank O’Hara conƒrmed portraiture’sdemise: “And the portrait show seems to have no faces in it at all . . . You suddenlywonder why in the world anyone ever did them.” 2The curator Henry Geldzahler provided an explanation for the decline ofportraiture: it was the result, he declared, of a lack of enlightened patronage:“As curator in a museum, I get the question about once a month from the wifeof a Supreme Court justice or from a governor, from somebody who has tohave an ofƒcial portrait done . . . It seems to me that Larry Rivers, Jim Dine,and Andy Warhol are the natural portraitists of our age, but most of the institutionsof government haven’t gotten around to understanding that yet.” 3 Withboth artist and patron wary of each other, portrait painting fell into the gulf betweenmodern art and its public. From the mid-nineteenth century on, thatgulf was spanned by the art photographer, whose role in the demise of portraitpainting was at least as important as the lack of sophisticated patronage.The history of modern portraiture is inextricable from the history of photography.Signiƒcantly, art photographers have played a central role in the representationof ƒne artists. From Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen to ArnoldNewman, Hans Namuth, and Richard Avedon, these practitioners have conƒrmedthe cultural myth of creativity with as much authority as Joseph Karshhas formulated the image of leadership for a business elite. Their work evidencesthe symbiotic relationship between art photography and modernism:a portrait by an art photographer (rather than a commercial photographer)helped to validate the historical importance of the artist, while at the sametime verifying (by metonymy), the photographer’s own artistic status. Stieglitz’sphotographs of Georgia O’Keeffe and Namuth’s of Jackson Pollock werecrucial to the establishment of the painters’ careers. That hybrid entity, the artphotographer, has been a bridge between the artist, isolated in the impracticalrealm of creativity, and the visually literate public. 4The liaison between artist and art photographer thus serves as a support tothe artist-critic-dealer network that constitutes the artworld; in turn, the artworldshapes our concept of the art historical signiƒcance of an artist’s work. It

From Portraiture to Pictures of People / 15is a liaison that Neel had to overcome as a portrait painter, for her own strugglefor recognition was unquestionably hampered by the fact that she could nothitch her portraits of fellow artists to their stars. Since her portraits were notpublished in the mass media, which was the realm of photographic reproduction,but remained instead within the boundaries of the artist’s production, thestatus of the portraitist’s sitter could not augment by re„ected radiance herown reputation. No painting of an artworld ƒgure, no <strong>matter</strong> how in„uential,could assure artistic recognition.Neel acknowledged portrait painting’s ambivalent artworld status when respondingto a critic’s question about why she, as a serious artist, concentratedon the genre:. . . actually portraits are where more crimes are committed than in any other formof art. I mean, witness college professors that hang on walls in petriƒed form. I thinkthey are frightful . . . they are portraits of so-called distinguished people; but I breakthese rules. 5Because the term had become thoroughly pejorative, Neel winced when shewas called a portrait painter, preferring to distance herself from the corpse ofofƒcial art by calling her paintings “pictures of people.” The linguistic feintdid not convince her contemporaries, however, who remained uncomfortablewith her seemingly exclusive preoccupation with the genre. Neel’s defensewas equivocal: rather than attempting to argue that she was transforming thetradition of realist and expressionist portraiture within modernism, she simplydefended the portrait as a legitimate subject in a period that nominally grantedthe artist complete freedom of choice. “I think that you can make just as greata painting of a person as you can of anything else . . . After all, the human creature—that’sit.” 6This statement was published in an interview Gerrit Henry conducted in1975 with ten contemporary artists working primarily in portraiture: Elaine deKooning, George Segal, Alex Katz, Philip Pavia, Alfred Leslie, George Schneeman,Sylvia Sleigh, Hedda Sterne, Chuck Close, and Neel. In explaining theresurrection of a genre only recently declared dead, Henry credited the “newpluralism” of the 1970s with having renewed interest in artists who had persistedin making portraits over the previous thirty years. 7 In the 1970s, with therigid doctrine of Greenbergian modernist formalism under siege, abstractpainting yielded its dominance to a diverse variety of trends, from photo realismto feminism to postmodernism. With renewed interest in realism in generaland portraiture in particular, Neel’s art could ƒnally be released from itssecond-class status. Her late success thus owes as much to the seismic shifts inthe New York artworld of the 1970s as it does to the speciƒc support of feminist

16 / The Subjects of the Artistartists and art historians. Neel told Henry that “I do feel vindicated by the returnof realism. Wouldn’t you? . . . I have all this backlog of all these years . . .” 8Neel’s deƒnition of “the human creature” as an individual re„ecting in aunique way the “Zeitgeist” of a given era must nonetheless have continued tosound old-fashioned in a decade when humanistic concepts of individualismand identity were questioned. The decade when ƒgurative art gained acceptancecoincided with the problematizing of individual identity in postmoderntheory. Although admired by her younger contemporaries, Neel never acknowledged,as they did, the dominating presence of photography, which hadforced a reconsideration of the very nature of personal identity.Instead, Neel was at her most radical in the choice of the subjects of herportraiture, and in her insistence that identity was inseparable from publicrealms of occupation and class. As with her contemporaries, many of her sitterswere connected to her personal life, either family or friends in the artworld.But Neel’s democratic sweep included examples from all segments of Americansociety, from middle-class professionals to people on the margins of Americanculture because of race, class, political afƒliations, or sexual orientation.Her inclusivity was an insistence that American culture could no longer bedeƒned as white middle class, and that modern art must shift its focus from theprivate and insular to the public.When, in reviewing her 1974 exhibition at the Whitney, Hilton Kramer accusedNeel of an inability to record anything but a direct response to a sitter,he paid her an unintended compliment, for it is precisely in her knowledge ofthe conventions of psychological portraiture and her ability to manipulatethem to convey the illusion of a direct record of empirical observation thatNeel’s artistic intelligence resided. Established in France by Edgar Degas andin America by Thomas Eakins, this realist tradition was transmitted to Neel inlarge measure through the art and writings of Robert Henri. This she combinedwith the expressionist tradition of Edvard Munch, Oskar Kokoschka,and in particular, the German new realists, Otto Dix and George Grosz, whoseportraits bridge individual and collective psychology.Neel was ƒrst exposed to that tradition during her training at the PhiladelphiaSchool of Design for Women from 1921 to 1925. Although the teachingat the PSDW had become thoroughly conventional when Neel studied there, 9the founder of the Ashcan School, Robert Henri, who had taught at the PhiladelphiaSchool in the 1890s, remained the school’s most admired artist. Withher friends Rhoda Medary and Ethel Ashton, the most adventurous membersof the student body, Neel set out to renew the now moribund legacy of theAshcan School. The three supplemented their training at the Graphic SketchClub where the models were “real people, including old, poor and city people.”10 According to the Belchers, Medary, the ringleader, “encouraged them

From Portraiture to Pictures of People / 17to sneak out . . . without the required gloves and hats, to take their easels to theReading Railroad yards or to the Italian market on South Ninth Street ...” 11Adopting the macho stance of the Eight, Neel bragged that she “was too roughfor the Philadelphia School of Design,” painting sailors with cigarettes insteadof girls in „uffy dresses. 12After her graduation, when she moved to Havana with Carlos, she had ampleopportunity to extend Henri’s painterly style to the ethnic populace there.Her Beggars, Havana (ƒg. 3) from 1926 shows a student adapting the broadtreatment and strong light/dark contrast of the paintings reproduced in Henri’sThe Art Spirit. Neel’s portrayal of her sitters is so generalized that the work canbarely be considered a portrait, and it is likely that in the end her approach toportraiture was in„uenced more strongly by Henri’s writings than by his painting.Indeed, The Art Spirit (1923), his widely read book, could serve as a statementof Neel’s aesthetic principles if not of her artistic conventions. It waspublished during Neel’s third year at the Philadelphia School of Design, andshe no doubt read it shortly thereafter, for while in Havana she gave a copy as agift to the novelist Alejo Carpentier. 13Henri’s biographer, William Innes Homer, has observed that “Every generation,it seems, requires its artist’s bible; the eager acceptance of The Art Spiritleaves no doubt that Henri satisƒed this need.” 14 As with any important bookthat one reads when approaching intellectual maturity, Neel may well have sointernalized the ideas of this most widely published of art manuals that theybecame her own, beginning with Henri’s deƒnition of realism. EchoingFrench critics from the previous century, he emphasized “truth” over “beauty,”often repeating Zola’s famous dictum that art is “nature seen through a temperament”(although he attributed the phrase to Corot). The goals of realism,he felt, were best achieved through the human ƒgure. 15 Like Eakins, Henriconsidered the model on the stand to be “a piece of history”: “It is the study ofour lives, our environment . . . They are real historical documents . . . Ordinaryhistories estrange us from the past . . . works of [art] bring us near it.” 16The concept of a “readable” urban physiognomy, transmitted to Henrithrough his study of Manet and Degas in Paris at the turn of the century, hadbeen articulated as early as 1876 in Edmond Duranty’s review of that year’s impressionistexhibition: “With one back, we desire that a temperament shouldbe revealed, the age, the social class; with a pair of hands, we must express amagistrate or a merchant; with one gesture, a whole series of sentiments . . .Hands sunk in pockets could be eloquent...” 17 For Neel as well, portraits werethe truest expression of culture and history. In her doctoral address at theMoore College of Art in 1971, Neel stated that “people’s images re„ect the erain a way that nothing else could. When portraits are good art they re„ect theculture, the time and many other things ...” 18 She later elaborated to Hills:

18 / The Subjects of the Artist“Art is a form of history . . . Now, a painting is a [speciƒc person], plus the factthat it is also the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age.” 19In an effort to emulate the intuitive response we have on ƒrst meeting a person,Henri argued that recording the individual-as-history was less a <strong>matter</strong> ofdeliberation than of unpremeditated action. In order to respond directly to thesubject, to the life that is the source for all art, Henri believed that the artistshould paint quickly and cultivate a strong visual memory:Realize that your sitter has a state of being, that this state of being manifests itself toyou through form, color and gesture . . . Work with great speed . . . the most vitalthings in the look of a face or of a landscape endure only for a moment. Workshould be done from memory. The memory is of that vital moment . . . The memoryof that special look must be held, and the “subject” can now only serve as an indifferentmanikin [sic] of its former self. The picture must not become a patchworkof parts of various moods. 20Neel also claimed credit for spontaneity: “When I paint . . . I deliberately crosseverything out . . . and just react, because I want that spontaneity and concentrationon that person to come across.” 21 She also paraphrased Henri’s emphasison memory in her description of Woman in Pink Velvet Hat (1944, ƒg. 4):You can’t paint any good portrait unless you have a good memory, because thereare tiny changes all the time. You know what the Chinese say: “You never bathe inthe same water twice.” [sic] And if you follow those changes you just have nothing.I deliberately set out to memorize, even in art school. 22In its crudeness, Woman in Pink Velvet Hat certainly appears spontaneous,as if it were executed at the greatest possible speed in order to maintain the inexplicablesense of fear and revulsion we occasionally feel when passing apedestrian on a city street. Yet, the ideal of a direct, one-shot, unmediated recordingof experience, so central to American artistic mythology via Henri orPollock, is in fact attained through reference to pre-existing visual models. Thepedestrian’s look of distraction—unfocused eyes and the gaping mouth—isfound, for instance, in portraits by Neel’s contemporary, the caricature artistPeggy Bacon. The painting’s distortions also recall German expressionist portraitssuch as Otto Dix’s The Journalist Sylvia von Harden (1926, ƒg. 5), whoselong, pointed face and nose, red-rimmed eyes, and downturned mouth createan impression of decadence similar to Neel’s portrait. Memory, then, is not a<strong>matter</strong> of retaining a single impression long enough to translate it into paint;the “direct response” of Woman in Pink Velvet Hat is doubly coded, by establishedvisual conventions and by written text. Artistic spontaneity has been littlemore than a consciously cultivated look, part of the modernist ideology ofindividual expression.

From Portraiture to Pictures of People / 19One ƒnal legacy to Neel from Henri’s teaching may have been the modelof the politically radical artist. Henri did not express his political beliefs in TheArt Spirit, but in his painting his radicalism was implied by his choice of subject<strong>matter</strong>. As Annette Cox has argued, Henri “was one of the ƒrst Americanartists to suggest that there could be a clear connection between art and socialreform.” 23 Henri’s portraits of blacks, in particular, are an important precedentfor Neel’s Spanish Harlem work. At the turn of the century blacks were sociallyand artistically invisible, 24 and Henri’s portraits can be credited with liftingthem from the realm of stock players in genre scenes. Yet Henri seems to havehad little concern either with referring to the actual economic and social conditionsin which blacks lived or with truly probing character. His former studentRockwell Kent questioned the depth of Henri’s commitment to social reform:“if Henri turned to . . . underprivilege . . . it was merely because, to him,man at this level was most revealing of his own humanity.” 25In extending Henri’s legacy in her mature work, Neel moved from generalizedpainterly impressions to incisive linear depictions. In his portrait of a vivaciousyoung girl, Eva Green (ƒg. 6), Henri seems to have followed his own exhortationto “feel the dignity of the child.” 26 Yet, we are given too little visualinformation to recognize in Eva any individual characteristics beyond those ofan accommodating cheerfulness. Moreover, by concentrating on black childrenin his portraits, Henri reinforced the stereotype of the black as “childlike.”Neel’s Two Black Girls (Antonia and Carmen Encarnacion) (1959, ƒg. 7)could be considered as an homage to Henri. They are painted with Henri’s attentionto individual facial expression and with a vigorous painterly stroke that,as in Eva Green, aids in conveying a sense of their vitality. The differences liein her greater attention to their speciƒc features and expressions, and to theeloquence of their body language and dress, which are conveyed through herdrawing. Like Degas before her, Neel grants to children the same psychologicalcomplexity as adults. The children’s tilted heads, and their awkward, angularposes suggest a combination of shyness, insecurity, and curiosity, whereastheir too-short dresses suggest tightened circumstances and its attendant vulnerability.The poignancy of pose and dress is offset by one girl’s patience (theleft-hand ƒgure) and the other’s inquisitiveness (the child on the right). Neel’sportrayal of childhood vulnerability and curiosity thus emerges from the matrixof a speciƒc confrontation across age and race.In a comment that is revealing of the unquestioned assumptions of his era,Henri said that “in the great [men], of which a nation may be proud, the racespeaks.” 27 By making “race” little more than one attribute inseparable from acomplex of others, Neel mitigated its difference and undercut stereotypes. Hersubjects are depicted as “two black girls who are probably sisters who grew upin difƒcult circumstances in Harlem in the 1950s and who are both curious

20 / The Subjects of the Artistand understandably uncomfortable in a white woman’s apartment”—“black”being but one word in a complex sentence. Wedged into the conƒning pictorialspace, the girls confront, in the unseen person of the artist, the unmarked,unexamined norm of whiteness against which they, even now, must begin tomeasure themselves. The potentially demeaning cliché—the childlike Negro—that served as Neel’s point of departure is revealed as the very stricture thatobstructs the childrens’ self-deƒnition.Inspired, along with several generations of American students, by Henri’sartistic principles, Neel put them into practice in creating visual codes sufƒcientlybroad and „exible to slip around stereotype and to create, with eachportrait, a complex layering of expressive codes. She intersected with the traditionof psychological portraiture at an historical moment when a new territoryhad been identiƒed but not adequately explored. For despite his genuine concernfor people of all classes, Henri had not succeeded in extending psychologicalportraiture successfully to marginalized groups. This Neel achieved.The Portrait as MetaphorPortrait paintings are most compelling when we feel that we are seeing past thefacial expression, pose, and dress to an imagined zone of privacy. Yet how dowe discriminate between the exterior and the interior person when all that isavailable for the artist’s use and for our interpretation is surface appearance?How do we know what character traits and/or emotions are being represented?Ofƒcial portraiture provides the simplest example. In recent history, governmentofƒcials who might have commissioned a Rivers, Dine, or Neel to“immortalize” a dignitary more often turned instead to a stable of competent,highly paid professionals, among them Andrew Wyeth, Norman Rockwell,and Gardner Cox, who conƒned their portraits within the narrow bounds ofpropriety and „attery. In his 1968 portrait of Richard Milhous Nixon (ƒg. 8),for instance, Rockwell took a face whose forbidding features had been thenewspaper cartoonists’ dream, softened the mouth and jowls, and used an uncharacteristicallyinformal pose, so that Nixon assumes the attributes of a kind,thoughtful teacher or clergyman. Rockwell provides no hint of the complexitiesand contradictions of the politician’s personality, but instead, through patientaccumulation of detail, provides convincing visual reassurance of a moral,high-minded individual. Far more potent than a written record, such portraitsmaintain patriarchal authority by physically embodying a society’s mostvalued ideals. As Sheldon Nodelman pointed out in his study of Roman portraiture,such “realistic” portraits assemble “a set of conventions dictated byideological motives . . . [and formed] into an interpretative ideogram.” 28 It is

From Portraiture to Pictures of People / 21through the consumption of such images—and Rockwell’s work has long beena staple of our cultural diet—that ideology is internalized. Neel’s choice ofthose very elements of society that were most resistant to the pressures of conformitythus takes on increased importance.Obviously, in her anti-establishment, noncommissioned portraiture, Neelwas not limited by governmental requirements but was free to experimentwith the repertoire of modernist portraiture’s poses, gestures, and facial expressionsso that the range of cues to character could encompass both the variedterrain of individual types and the different levels of our social hierarchy. Nonetheless,the gulf between professional and artistic portraiture is not as wide aspainters wished it to be. Each had to learn conventions for representing character,and this acquired knowledge could be used either honoriƒcally or “psychologically.”Neel’s portraits of Helen Merrell Lynd, Virgil Thomson, andLinus Pauling, and even her own nude self-portrait, are thus at home in thecollection of the National Portrait Gallery alongside their ideological opposite,the Nixon portrait.Those researchers who have studied facial expression and body languagehave argued that our physical appearance—posture, gesture, the set of one’sfeatures—communicates powerful messages that are universally, if not alwaysaccurately, interpreted. 29 When looking at a portrait painting, viewers respondre„exively to facial expression, gesture, and pose as they have been conditionedto do to a human presence: they marshall a fund of knowledge based onprevious interpersonal interaction. Viewers’ identiƒcation of both permanentcharacter traits and transitory emotions is habitual rather than systematic, anddifƒcult to either verbalize or quantify. And if we have no knowledge of theperson or situation, our interpretations of that “deeper reality” can be spectacularlywrong. Although numerous branches of science and social science, includinganthropology, linguistics, psychoanalysis, clinical psychology, socialpsychology, and sociology, continue to study facial expression, gesture, andbody language, no consensus has been reached concerning the meaning ofthe varying positions of the face or body, nor has “an invariant relation betweenexpressed behavior and internal motive” 30 been discovered.Moreover, as the artist well knows, the painting is not the equivalent ofdirect human contact, as it lacks the factor both of motion, which permits aninitial separation of permanent character traits from temporary feeling, and ofdepth, which provides a fuller sense of bodily proportion and the set of thefeatures. The artist must devise, therefore, a set of conventions that will evoke aresponse comparable to that of human interaction, but on the delimited, twodimensionalplane of the canvas.Throughout her life’s work Neel created and modiƒed a database of schemata,modifying established artistic precedent as well as inventing some con-