The Correspondence of MICHAEL FARADAY - IET Digital Library

The Correspondence of MICHAEL FARADAY - IET Digital Library

The Correspondence of MICHAEL FARADAY - IET Digital Library

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

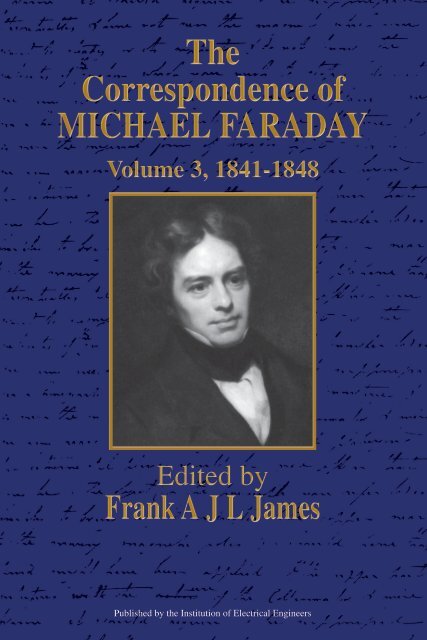

<strong>The</strong><strong>Correspondence</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>MICHAEL</strong> FaradayVolume 3, 1841-1848Edited byFrank A J L JamesPublished by the Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers

<strong>The</strong><strong>Correspondence</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>MICHAEL</strong> <strong>FARADAY</strong>Volume 3

Plate 1: Michael Faraday by Thomas Phillips. See letter 1339

<strong>The</strong><strong>Correspondence</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>MICHAEL</strong> <strong>FARADAY</strong>Volume 31841-December 1848Letters 1334-2145Edited byFrank A J L JamesPublished by the Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers

Published by: <strong>The</strong> Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers, London, United Kingdom© 1996; Selection and editorial material, <strong>The</strong> Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical EngineersThis publication is copyright under the Berne Convention and the UniversalCopyright Convention. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for thepurposes <strong>of</strong> research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted underthe Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may bereproduced, stored or transmitted, in any forms or by any means, only with theprior permission in writing <strong>of</strong> the publishers, or in the case <strong>of</strong> reprographicreproduction in accordance with the terms <strong>of</strong> licences issued by the CopyrightLicensing Agency. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms shouldbe sent to the publishers at the undermentioned address:<strong>The</strong> Institution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers,Michael Faraday House,Six Hills Way, Stevenage,Herts. SG1 2AY, United KingdomWhile the editor and the publishers believe that the information and guidancegiven in this work is correct, all parties must rely upon their own skill andjudgment when making use <strong>of</strong> it. Neither the editor nor the publishers assume anyliability to anyone for any loss or damage caused by any error or omission in thework, whether such error or omission is the result <strong>of</strong> negligence or any othercause. Any and all such liability is disclaimed.<strong>The</strong> moral right <strong>of</strong> the editor to be identified as editor <strong>of</strong> this work has beenasserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and PatentsAct 1988.British <strong>Library</strong> Cataloguing in Publication DataA CIP catalogue record for this bookis available from the British <strong>Library</strong>ISBN 0 86341 250 5Printed in England by Short Run Press Ltd., Exeter

To Marie and Rupert Hall for showing me how

Plates1. Michael Faraday by Thomas Phillips. Dust jacket and frontispiece2. James South. 493. Charles Lyell. 2494. Jean-Baptiste-Andre Dumas. 2905. Justus Liebig. 2996. Photograph <strong>of</strong> John Frederic Daniell and Faraday, with aDaniell Constant Cell. 3367. William Thomson, age 22. 4048. Jane Marcet. 4339. Faraday giving his Friday Evening Discourse on23 January 1846, "Recent researches into the correlatedphenomena <strong>of</strong> magnetism and light". 46910. <strong>The</strong> Chemical Section <strong>of</strong> the British Association at the1846 meeting in Southampton. 55011. George Biddell Airy.12. John Barlow.617729

AcknowledgementsIt is with great pleasure and gratitude that I thank the Institution <strong>of</strong>Electrical Engineers for the financial support without which the project tolocate, copy and edit all extant letters to and from Faraday would nothave been possible. Furthermore, I thank them for the support whichmade possible the publication <strong>of</strong> this volume. I am grateful to the RoyalInstitution for the provision <strong>of</strong> all the essential support they have givenfor this work and to my friends and colleagues there for their unceasingsupport and interest. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge the support <strong>of</strong>the British Academy for a grant to support specific aspects <strong>of</strong> the workfor this volume.I thank the following institutions and individuals for permission topublish the letters to and from Faraday which are in their possession: <strong>The</strong>Director <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution (and for plates 3-6, 8 and 12); theInstitution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers; the Elder Brethren <strong>of</strong> Trinity House forthe letters in the Guildhall <strong>Library</strong>; the Oeffentliche Bibliothek derUniversitat Basle; the Syndics <strong>of</strong> Cambridge University <strong>Library</strong> and, forthe letters in the archives <strong>of</strong> the Royal Greenwich Observatory, theDirector <strong>of</strong> the Royal Greenwich Observatory; the President and Council<strong>of</strong> the Royal Society; the Trustees <strong>of</strong> the Wellcome Trust; the Master andFellows <strong>of</strong> Trinity College Cambridge; Smithsonian Institution Libraries,Washington; the British <strong>Library</strong> Manuscript Department; Mr W.A.F.Burdett-Coutts; the Bodleian <strong>Library</strong>, Oxford, Lady Fairfax-Lucy forletters deposited in the Somerville collection and the Earl <strong>of</strong> Lytton forthe letters deposited in the Lovelace-Byron collection; the Archives <strong>of</strong> theScience Museum <strong>Library</strong>, London; the Archives de l'Academie desSciences de Paris; the Librarian <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> Bristol; the NationalArchives <strong>of</strong> Canada; Mrs Elizabeth M. Milton; Mrs J.M. and Jean Ferguson;the Bibliotheque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva; the AccademiaNazionale delle Scienze, Rome; the American Philosophical Society<strong>Library</strong>, Philadelphia; Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society;Academie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts deBelgique; the Archives, California Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology; the CollegeArchives, Imperial College <strong>of</strong> Science, Technology and Medicine, London;the National <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> New Zealand; the Queen's University <strong>of</strong> Belfast;

Massachusetts Historical Society; Liverpool Record Office; the Houghton<strong>Library</strong>, Harvard University; the Hydrographic Office, Taunton; NationalResearch Council Canada; Buckinghamshire Record Office; the Sutro<strong>Library</strong>, San Francisco; the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst; JohnMurray, Ltd; the Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection in the History <strong>of</strong>Chemistry, Van Pelt <strong>Library</strong>, University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania; the Handskriftsavdelningen,Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek; Heinz Archive and <strong>Library</strong>,National Portrait Gallery (and for plate 1); the Trustees <strong>of</strong> the BritishMuseum; the Sondersammlungen, Deutsches Museum, Munich; theGeological Society; Mr Tom Pasteur; Handskriftafdelingen, Det KongeligeBibliothek, Copenhagen; Edinburgh University <strong>Library</strong>; the Rare Booksand Manuscripts Division, New York Public <strong>Library</strong>; the Burndy <strong>Library</strong>,Massachusetts Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology; the Francis A. Countway <strong>Library</strong><strong>of</strong> Medicine, Boston; the New-York Historical Society; the Director,Biblioteca Estense, Modena; the Historical Society <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania; MrsElizabeth Faraday Baird; St Andrews University <strong>Library</strong>; the State <strong>Library</strong><strong>of</strong> New South Wales; the Royal Swedish Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences for the letterin the Stockholms Universitetsbibliotek; the Trustees <strong>of</strong> the National<strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> Scotland; Special Collections and Archives, Knox College<strong>Library</strong>, Galesburg; the Staats- und Universitatsbibliothek Hamburg; MsJan Reid; Lawes Agricultural Trust, Rothamsted Experimental Station; DrRoy G. Neville <strong>of</strong> the Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical <strong>Library</strong>, California;the President and Fellows <strong>of</strong> Magdalen College, Oxford; Mr Anthony F.P.Morson; University <strong>of</strong> London <strong>Library</strong>; the Director <strong>of</strong> Administration,University <strong>of</strong> London; Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dr Arno Muller; Herr Paul Heier; theLibrarian, Glasgow University <strong>Library</strong>; the <strong>Library</strong>, <strong>The</strong> Academy <strong>of</strong>Natural Sciences <strong>of</strong> Philadelphia; the Spira Collection; UniversitatsbihekLeipzig; the President and Council <strong>of</strong> the Royal College <strong>of</strong> Surgeons <strong>of</strong>England; the late Mr and Mrs S. Aida; the Handschriftenabteilung,Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin; the Sidney M.Edelstein <strong>Library</strong>, the Hebrew University, Jerusalem; the Syndics <strong>of</strong> theFitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Pr<strong>of</strong>essor George W. Platzman; theMuseum Boerhaave, Leiden; the Peirpont Morgan <strong>Library</strong>, New York; theMaddison Collection, Templeman <strong>Library</strong>, University <strong>of</strong> Kent at Canterbury;Mr Roy Deeley; Mr D. Walker; the Rare Book and Manuscript<strong>Library</strong>, Columbia University <strong>Library</strong>; the Corporation <strong>of</strong> London and theGreater London Record Office; the Society <strong>of</strong> Antiquaries <strong>of</strong> Newcastleupon Tyne for the letter in the Northumberland Record Office; the RoyalAstronomical Society (and for plates 3 and 11); the Council <strong>of</strong> the LinneanSociety <strong>of</strong> London; the Royal Society for the encouragement <strong>of</strong> Arts,Manufactures and Commerce; the British Museum (Natural History);Department <strong>of</strong> Geology, National Museum <strong>of</strong> Wales; St Bride Printing<strong>Library</strong>; Strathclyde University Archives; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek;Oesterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Bibliothek; University <strong>of</strong>

Wales, Bangor. All Crown copyright material in the Public Record Office,the India Office <strong>Library</strong> and Records, and elsewhere is reproduced bypermission <strong>of</strong> the Controller <strong>of</strong> Her Majesty's Stationery Office.I wish to thank the staff <strong>of</strong> all the institutions listed above for helpingme locate the letters to and from Faraday in their possession and in mostcases providing me with photocopies and answering follow up questions.Particular thanks should go to Mrs Irena McCabe and her staff at theRoyal Institution, Mrs E.D.P. Symons and her staff at the Institution <strong>of</strong>Electrical Engineers, Mrs Sheila Edwards and latterly Ms Mary Nixon andher staff at the Royal Society, Mr Adam Perkins <strong>of</strong> Cambridge University<strong>Library</strong> and Dr Martin L. Levitt <strong>of</strong> the American Philosophical Society.Although the following institutions do not have any Faraday lettersin their archives which are published in this volume, I thank them foranswering queries concerning letters in this volume: the Athenaeum Club,Surrey Record Office, the Royal Society <strong>of</strong> Chemistry, Friends' House,University College, Royal Caledonian Schools, Royal Society <strong>of</strong> Edinburgh,Scottish Record Office, the Archives <strong>of</strong> the Institution <strong>of</strong> Civil Engineers,Scottish Record Office, Durham County Record Office, Lambeth Palace<strong>Library</strong>, the Royal Archives Windsor, the Principal Registry <strong>of</strong> the FamilyDivision <strong>of</strong> the High Court (in Somerset House), the General RegisterOffice (in St Catherine's House) and last, but not least, the NationalRegister <strong>of</strong> Archives whose resources once again directed my attention tothe location <strong>of</strong> many letters.Many friends and colleagues have helped in locating letters and withqueries and I wish to thank the following particularly: Dr Mari E.W.Williams, Dr John Krige, Dr Shigeo Sugiyama and Mr Russell Warhurst fordoing the initial ground work <strong>of</strong> locating Faraday letters in Paris, Geneva,Japan, and the Royal Military Academy respectively. I thank Dr J.V. Field(for help with the Greek and Latin and for answering various art historicaland other queries), Mr J.B. Morrell (for help relating to the BritishAssociation), Dr M.B. Hall (for advice and information on the RoyalSociety), Mr Ge<strong>of</strong>frey King (who placed the almost the entire LondonSandemanian community on his genealogy programme thereby saving meto immense amount <strong>of</strong> tedious work in sorting out manually the relationsbetween individuals), Dr Willem Hackmann (for discussions on nineteenthcentury electricity), Herr Michael Barth (for translating the letterfrom German), Dr Larry J. Schaaf (for discussions on the history <strong>of</strong>photography), Pr<strong>of</strong>essor W.H. Brock (for help with Liebig relatedqueries), Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Michael Collie (for help with Elgin newspapers), DrMuriel Hall (for directing my attention to the sample <strong>of</strong> Faraday's heavyglass in Queen Anne's School, Caversham), Mr John Smyons (for helpwith obscure medical terms), Dr Allan Chapman (for discussions onnineteenth century astronomy), Mr John Thackray (for information onthe history <strong>of</strong> nineteenth century geology), Ms Marysia HermaszewskaXI

XI1(for translating the letter from the Spanish), Mrs Margaret Ray (for lettingme read her excellent dissertation on the Haswell Colliery explosion), DrF.J. Fitzpatrick (for help with indentifying some Latin quotations), DrPeter Nolte and Dr Ulf Bossel (for information about Schoenbein and hisfamily), Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ryan Tweney (for many discussions on Faraday'swork) and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor David Knight (who acted as a court <strong>of</strong> last appeal formany <strong>of</strong> the obscurities occuring in this volume which are thus clearer).Furthermore, it is with great pleasure that 1 acknowledge the helpand hospitality I have received from many members <strong>of</strong> Faraday'sextended family. In particular, Mr Michael A. Faraday (for providing mewith additional information to that contained in his and the late DrJoseph E. Faraday's Faraday genealogy) and Miss Mary Barnard (whoprovided me with a detailed genealogy <strong>of</strong> the Barnard family whosetraditional business <strong>of</strong> gold and silversmithing she continues). I amgrateful to Mr Gerard Sandeman (the last remaining Elder <strong>of</strong> the Glasite /Sandemanian Church) who allowed me access to the nineteenth centuryrecords <strong>of</strong> the Sandemanian Church in London and also provided muchvaluable genealogical information. I also thank Mrs Isobel Blaikley andMrs Molly Spiro for ferreting out material from the rest <strong>of</strong> their family andfor introducing me to various members. <strong>The</strong>se are too numerous tomention fully here, but in this volume I should particularly like to note thegenerosity <strong>of</strong> Mr Martin Conybeare in placing his album <strong>of</strong> Faraday letterson permanent loan in the Royal Institution.I thank Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ge<strong>of</strong>frey Cantor, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Peter Day, Dr SophieForgan and Dr David Gooding for their valuable advice and comments onthe introduction and for many stimulating discussions on Faraday.Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Cantor also informed me <strong>of</strong> many additional places where Icould locate Faraday letters and generously shared much usefulinformation about members <strong>of</strong> the Sandemanian community in thenineteenth century which he gathered in the course <strong>of</strong> writing his bookon Faraday's religion.Last, but not least, I thank my wife, Joasia, who was again able totranslate the letters from the French and the Italian.

Editorial Procedure andAbbreviationsAll letters to and from Faraday which have been located in eithermanuscript or in printed form have been included in chronological order<strong>of</strong> writing. <strong>The</strong> term letter has been broadly construed to include not onlyextracts from letters where only these have survived, but also reports onvarious matters which Faraday submitted to institutions or individuals.What has not been included are scientific papers written in the form <strong>of</strong> aletter, although letters which were deemed worthy <strong>of</strong> publication,subsequent to their writing, are included as are letters to journals,newspapers etc. Letters which exist only in printed paraphrase form havenot been included. Letters between members <strong>of</strong> Faraday's family, <strong>of</strong>which there are relatively few, are included as a matter <strong>of</strong> course. Ofletters between other third parties only those which had a direct effect onFaraday's career or life are included. <strong>The</strong> large number <strong>of</strong> letters whichsimply say what an excellent lecturer, chemist, philosopher, man etcFaraday was, or the very few that are critical <strong>of</strong> him, are not included.<strong>The</strong> aim has been to reproduce, as accurately as the conventions <strong>of</strong>typesetting will allow, the text <strong>of</strong> the letters as they were written. <strong>The</strong>only exceptions are that continuation words from one page to the nexthave not been transcribed and, as it proved impossible to render intoconsistent typeset form the various contractions with which Faraday andhis correspondents tended to terminate their letters, all the endings <strong>of</strong>letters are spelt out in full irrespective <strong>of</strong> whether they were contractedor not. Crossings out have not been transcribed, although majoralterations are given in the notes.It should be stressed that the reliability <strong>of</strong> the texts <strong>of</strong> letters foundonly in printed form leaves a great deal to be desired as a comparison <strong>of</strong>any letter in Bence Jones (1870a, b) with the original manuscript, where ithas been found, will reveal. <strong>The</strong> punctuation and spelling <strong>of</strong> lettersderived from printed sources has been retained.Members <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> Friends and those closely associated withthem had a strong aversion to using the names <strong>of</strong> the months (which theyregarded as pagan) in dating letters. Instead they numbered the months:

XIVthus, for example, 18 6mo 1844 should be read as 18 June 1844. <strong>The</strong> onlyother calendar difference reflects the fact that by the early nineteenthcentury all <strong>of</strong> Europe apart from the Russian Empire had adopted the newstyle calendar. In this volume only letter 1952 is dated in the old stylecalendar (by this time twelve days adrift from the new style) in use inRussia until 1917.Each letter commences with a heading which gives the letternumber, followed by the name <strong>of</strong> the writer and recipient, the date <strong>of</strong> theletter and its source. Following the main text endorsements and theaddress are always given. <strong>The</strong> postmark is only given when it is used todate a letter or to establish that the location <strong>of</strong> the writer was differentfrom that <strong>of</strong> the letter head.<strong>The</strong> following symbols are used in the text <strong>of</strong> the letters:[some text][word illegible][MS torn][sic][blank in MS]indicates that text has been interpolated.indicates that it has not been possible to read aparticular word (or words where indicated).indicates where part <strong>of</strong> the manuscript no longerexists (usually due to the seal <strong>of</strong> the letter beingplaced there) and that it has not been possible toreconstruct the text.reconstructs the text where the manuscript hasbeen torn.indicates that the peculiar spelling or grammar inthe text has been transcribed as it is in themanuscript. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> this has been restricted asmuch as possible to rare cases. Hence, for example,Faraday's frequent spelling <strong>of</strong> "Herschell" is notfollowed by [sic].indicates where part <strong>of</strong> the text was deliberately leftblank.

XV<strong>The</strong> following abbreviations are used in the texts <strong>of</strong> the letters:CECivil EngineersDCL Doctor <strong>of</strong> Civil Law [also given as LLD occasionally]DVDeo volente [God willing]FEFriday EveningFRSFellow <strong>of</strong> the Royal SocietyGCB Grand Cross <strong>of</strong> the BathHRH His/Her Royal HighnessMPMember <strong>of</strong> ParliamentMRIMember <strong>of</strong> the Royal InstitutionPGSPresident <strong>of</strong> the Geological SocietyPM Philosophical MagazineQED quod erat demonstrandum [which was to be proved]RARoyal ArtilleryRERoyal EngineersRIRoyal InstitutionRMRoyal Military [College]RNRoyal NavyRSRoyal SocietyUSUnited Services [Club]US(A) United States (<strong>of</strong> America)

XVIBritain did not decimalise its currency until 1971 and is still halfheartedlytrying to metricate its weights and measures, although inscientific and technical writings this latter has been largely completed.During the nineteenth century the main unit <strong>of</strong> currency was the pound(£) which was divided into twenty shillings (s) <strong>of</strong> twelve pennies (d) each.<strong>The</strong> penny was further sub-divided into a half and a quarter (called afarthing). A sum such as, for example, one pound, three shillings andsixpence could be written as 1-3-6 with or without the symbols for thecurrency values. Likewise two shillings and six pence could be written as2/6; this particular coin could be called half a crown. <strong>The</strong>re was oneadditional unit <strong>of</strong> currency the guinea which was normally defined astwenty one shillings. <strong>The</strong>re is no agreed figure by which the value <strong>of</strong>money in the nineteenth century can be multiplied to provide anindication <strong>of</strong> what its value would be now and, as this is one <strong>of</strong> the morecontentious areas <strong>of</strong> economic history, no attempt will be made here toprovide such a figure.<strong>The</strong> following give conversion values for the units used in thecorrespondence as well as their value in modern units. For mass only theAvoirdupois system is given as that was most commonly used. But it isimportant to remember that both the Apothecaries' and Troy systemswere also used to measure mass and that units in all these systemsshared some <strong>of</strong> the same names, but different values. For conversionfigures for these latter (and also for other units not given here) seeConnor (1987), 358-60.TemperatureTo convert degrees Fahrenheit (F) to degrees Centigrade (C),subtract 32 and then multiply by 5/9.To convert degrees Reaumur (R) to degrees Centigrade (C),multiply by 1.25.Length1 inch (in or ") = 2.54 cm1 foot (ft or ') = 12 inches = 30.48 cm1 yard (yd) = 3 feet =91.44 cm1 mile = 1760 yards = 1.6 kmVolume1 cubic inch (ci) = 16.38 cc1 pint = .568 litres1 gallon = 8 pints = 4.54 litres

xviiMass1 grain (gr) = .065 gms1 ounce (oz) = 28.3 gms1 pound Ob) = 7000 grains16 ounces = .453 kg1 stone = 14 pounds = 6.3 kg1 hundredweight (cwt) = 112 pounds = 50.8 kg1 ton = 20 cwt = 1.02 tonnePower1 horse power = 746 kw<strong>The</strong> Notes<strong>The</strong> notes aim to identify, as far as has been possible, individuals, papersand books which are mentioned in the letters, and to explicate events towhich reference is made (where this is not evident from the letters). Incorrespondence writers when discussing individuals with titles usedthose titles, but as British biographical dictionaries use the family namethis is given, where necessary, in the notes.<strong>The</strong> biographical register identifies all those individuals who arementioned in three or more letters (in either text or notes). <strong>The</strong> registerprovides a brief biographical description <strong>of</strong> these individuals and anindication <strong>of</strong> where further information may be found. No furtheridentification <strong>of</strong> these individuals is given in the notes. Those who arementioned in one or two letters are identified in the notes. Whileinformation contained in the genealogies <strong>of</strong> various Sandemanian familieshas been invaluable, this information has been checked against thatavailable in the General Register Office (GRO) or Scottish Record Office(SRO). In these cases, and others, where the GRO or SRO is cited, the year<strong>of</strong> death is given followed by the age at death. If this agrees withinformation derived from other sources, then the year <strong>of</strong> birth in given inpreference to the age.References in the notes refer mainly to the bibliography. However,the following abbreviations are used to cite sources <strong>of</strong> information in thenotes:ACADBAuDBBxBDPEAlumni CantabrigiensesAllgemeine Deutsche BiographieAustralian Dictionary <strong>of</strong> BiographyBoase Modern English Biography, volume xBryan Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Painters and Engravers

XV111CPComplete PeerageDABDictionary <strong>of</strong> American BiographyDBFDictionnaire de Biographie FrancaiseDBIDizionario Biografico degli ItalianiDBLDansk Biografisk LeksikonDCBDictionary <strong>of</strong> Canadian BiographyDHBSDictionnaire Historique et Biographique de la SuisseDNBDictionary <strong>of</strong> National Biography (if followed by anumber then it refers to that supplement; mp =missing person supplement)DNZBDictionary <strong>of</strong> New Zealand BiographyDQB Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Quaker Biography (typescript inFriends' House London and Haverford CollegePennsylvania)DSBDictionary <strong>of</strong> Scientific BiographyEUIEncyclopedia Universal IlustradaLUILessico Universale ItalianoNBLNorsk Biografisk LeksikonNBUNouvelle Biographie UniverselleNDBNeue Deutsche BiographieNNBWNieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch WoordenboekOBLOesterreichisches Biographisches LexikonPxPoggendorff Biographisch-LiterarischesHandworterbuch, volume xPODPost Office Directory (see below)RI MMGreenaway (1971-6). This is followed by date <strong>of</strong>meeting, volume and page number.SMOKSvenska Man och Kvinnor Biografisk UppsiagsbokReports <strong>of</strong> lectures and references to plays and poems are givenonly in the notes. References to the Gentlemens'Magazine and the AnnualRegister, as well the daily and weekly press are likewise given only in thenotes. <strong>The</strong> following directories are cited in the notes:Imperial CalendarLaw ListNavy ListPost Office Directory (POD)Citations to these directories, unless otherwise indicated, refer tothe edition <strong>of</strong> the year <strong>of</strong> the letter where the note occurs. All thesedirectories universally make the claim to contain up to date and completeinformation. This was frequently far from the case and this explainsapparent discrepancies which occur.

XIXFaraday's Diary. Being the various philosophical notes <strong>of</strong> experimentalinvestigation made by Michael Faraday, DCL, FRS, during the years 1820-1862 and bequeathed by him to the Royal Institution <strong>of</strong> Great Britain. Now, byorder <strong>of</strong> the Managers, printed and published for the first time, under theeditorial supervision <strong>of</strong> Thomas Martin, 7 volumes and index, London,1932-6 is cited as Faraday, Diary, date <strong>of</strong> entry, volume number andparagraph numbers, unless otherwise indicated.Faraday's "Experimental Researches in Electricity" are cited in thenormal way to the bibliography, but in this case the reference is followedby "ERE" and the series and paragraph numbers, unless otherwiseindicated.Manuscript abbreviations<strong>The</strong> following are used to cite manuscript sources where the primaryabbreviation is used twice or more. (NB Reference to material in privatepossession is always spelt out in full). <strong>The</strong>se abbreviations are used inboth the letter headings and the notes:AC MSANSAPSAS MSBEMBL add MSBM DWAA MSBod MSBPUG MSBRAI ARBBROBrUL MSBuL, MITCITADM HSEUL MSFACLMGL MSGROGS MSAthenaeum Club ManuscriptAccademia Nazionale delle Scienze, RomeAmerican Philosophical SocietyAcademie des Sciences ManuscriptBiblioteca Estense, ModenaBritish <strong>Library</strong> additional ManuscriptBritish Museum Department <strong>of</strong> Western AsiaticAntiquities ManuscriptBodleian <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptBibliotheque Publique et Universitaire de GeneveManuscriptBibliotheque royale Albert Ier, Academie royale deBelgiqueBuckinghamshire Record OfficeBristol University <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptBurndy <strong>Library</strong>, Massachusetts Institute <strong>of</strong>TechnologyCalifornia Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology ArchivesDeutsches Museum HandschriftEdinburgh University <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptFrancis A. Countway <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> MedicineGuildhall <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptGeneral Register Office (see above)Geological Society Manuscript

XXHKBC Handskriftafdelingen, Det Kongelige Bibliothek,Copenhagen;HLHUHoughton <strong>Library</strong>, Harvard UniversityHO MSHydrographic Office ManuscriptHSPHistorical Society <strong>of</strong> PennsylvaniaFDCFerdinand Dreer CollectionIC MSImperial College ManuscriptsCRoyal College <strong>of</strong> Chemistry papersLPLyon Playfair papersICE MSInstitution <strong>of</strong> Civil Engineers ManuscriptOCOriginal CommunicationsIEE MSInstitution <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineers ManuscriptSCSpecial Collection2 David James Blaikley Collection3 S.P. Thompson CollectionIOLR MSIndia Office <strong>Library</strong> and Records ManuscriptJMAArchives <strong>of</strong> John Murray LtdLROLiverpool Record OfficeMHSMassachusetts Historical SocietyNACNational Archives <strong>of</strong> CanadaNLNZ MSNational <strong>Library</strong> <strong>of</strong> New Zealand ManuscriptNPGANational Portrait Gallery ArchivesNRCC ISTINational Research Council Canada Institute forScientific and Technology InformationNYHS MSNew-York Historical Society ManuscriptNYPLNew York Public <strong>Library</strong>PROPublic Record Office, KewADM 12Admiralty DigestBJ3Sabine papersFO610Passport registersHO43Home Office out lettersHO45Home Office registered papersLC6Records <strong>of</strong> LeveesSUPP5Ordnance establishment recordsWO44Ordnance Office in lettersWO45Ordnance Office registersWO46Ordnance Office out lettersQUB MSQueen's University Belfast ManuscriptRGORoyal Greenwich Observatory6 Airy papersRI MSRoyal Institution ManuscriptFlFaraday CollectionA-GLetters from FaradayH-KFaraday's portrait albums

XXIF4GGBGMHDJBRIRMAWO150RSMSRSAMSSI241APBuCertCMCMB90CHSMCPTRRThAD MSSLSMMSSROSuROTCC MSUB MS NSULCAdd MS 7342Add MS 7656UPCHOC MSUUEWWIHM MSFALFWLPS MSFaraday s notes <strong>of</strong> lecturesPapers <strong>of</strong> W.R. GroveGuard BookMinutes <strong>of</strong> General MeetingPapers <strong>of</strong> Humphry DavyPapers <strong>of</strong> John BarlowAdministrative papersRoyal Military AcademyRoyal Military Academy incoming lettersRoyal Society ManuscriptFaraday's Diploma bookArchived PapersBuckland PapersCertificate <strong>of</strong> Fellow ElectedCouncil Minutes (printed)Committee Minute BooksMinutes <strong>of</strong> Committee <strong>of</strong> papers, 1828-1852Herschel PapersMiscellaneous <strong>Correspondence</strong>Manuscript <strong>of</strong> PhilTrans. papersReferees ReportsThorpe PapersRoyal Society <strong>of</strong> Arts ManuscriptSmithsonian Institution <strong>Library</strong>ArchivesDibner CollectionSutro <strong>Library</strong>Science Museum <strong>Library</strong> ManuscriptScottish Record Office (see above)Surrey Record OfficeTrinity College Cambridge ManuscriptUniversitat Basle Manuscript Nachlass SchoenbeinUniversity <strong>Library</strong> CambridgeThomson PapersStokes PapersUniversity <strong>of</strong> PennsylvaniaCenter for History <strong>of</strong> Chemistry ManuscriptUppsala University HandskriftsavdelningenErik Waller's Collection <strong>of</strong> AutographsWellcome Institute for the History <strong>of</strong> MedicineManuscriptFaraday autograph letter fileWhitby Literary and Philosophical SocietyManuscript

Note on SourcesIn the British <strong>Library</strong> there is a set <strong>of</strong> six letters (BL add MS 46404, f.3-9)written by Angela Georgina Burdett Coutts between 1846 and 1848 whichare catalogued, albeit with a query, as being to Faraday. <strong>The</strong>se letterswere clearly written in a Royal Institution context. However, there is noevidence from any <strong>of</strong> the letters published in this volume that theseBritish <strong>Library</strong> letters were to Faraday and they have thus been omitted.

Trinity House ArchiveIn 1836 Faraday was appointed "Scientific adviser to this Corporation [<strong>of</strong>Trinity House] in experiments on Light" 1 , a post that he held until 1865.<strong>The</strong> Elder Brethren <strong>of</strong> Trinity House have been responsible since 1514 forsafe navigation round the shores <strong>of</strong> England and Wales and are thus incharge <strong>of</strong> lighthouses, buoys and pilotage. It was known through variousnineteenth century biographies <strong>of</strong> Faraday that he had undertaken aconsiderable amount <strong>of</strong> work for the Corporation. Until recently it wasthought that the "nineteen large portfolios full <strong>of</strong> manuscripts" 2 relatingto his work for Trinity House and presented to them by Sarah Faraday in1867 3 , had been destroyed by bombing during the 1939-1945 war 4 .However, on the transfer <strong>of</strong> the Trinity House archive to the Guildhall<strong>Library</strong> and its cataloguing and opening in April 1994, it was found thatthe majority <strong>of</strong> Faraday's papers had survived and now form GL MS30108.In all Faraday created 150 files in the course <strong>of</strong> his work for TrinityHouse, though files 1-22, dealing with his work in the late 1830s have notbeen found. In the files that have survived are more than 500 lettersbetween Faraday and Trinity House together with notes made by Faradayon the matters dealt with by the files. Some indication <strong>of</strong> his work for theCorporation between 1836 and 1840 can be gained from copies (made byTrinity House) <strong>of</strong> fourteen letters written by Faraday during this period .<strong>The</strong>se letters, which should have been included in volume two, will bepublished in the addenda in the final volume.According to Bence Jones, who had access to the whole collection,Faraday's first tasks for Trinity House in 1836 were to construct aphotometer and experiment on the preparation <strong>of</strong> oxygen 6 . In 1837 and1838 he was mainly concerned with comparing different types <strong>of</strong> lamps 7 .Bence Jones does not discuss what occupied Faraday's attention during1839 and 1840 8 , but it is clear from the letters in the Trinity House archivethat Faraday worked on the optical adjustment <strong>of</strong> lighthouse lenses 9 .<strong>The</strong> Corporation was and is run by the Deputy Master 10 and by theElder Brethren who are mostly, though not exclusively, drawn from themerchant navy. Most <strong>of</strong> the correspondence between Faraday and TrinityHouse was handled by the Secretary, who for the period covered by this

XXVIvolume, was Jacob Herbert. Herbert received instructions from theDeputy Master and Elder Brethren through a number <strong>of</strong> committeeswithin the Corporation made up by various combinations <strong>of</strong> ElderBrethren 11 . <strong>The</strong> Committee for Lights, which was responsible forlighthouses and beacons, was the committee most closely connectedwith Faraday's work. But Faraday's advice also concerned the Court (thegoverning body <strong>of</strong> the Corporation), the By Board (which removedvarious mundane administrative tasks from the direct consideration <strong>of</strong>the Court) and the Committee <strong>of</strong> Wardens (which was responsible forfinancial matters). Unfortunately, the minutes <strong>of</strong> the Committee for Lightswere destroyed by bombing 12 . However, the minutes <strong>of</strong> the Court, ByBoard and Committee <strong>of</strong> Wardens have survived and give a goodindication <strong>of</strong> how Faraday's advice was received and acted upon byTrinity House.Faraday's papers in the archive and the administrative records <strong>of</strong>Trinity House show the crucial role that Faraday played in thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> the lighthouse service in the middle third <strong>of</strong> thenineteenth century. This is already apparent in the letters published inthis volume, but will become even more so in later volumes 13 .1. Herbert to Faraday, 5 February 1836, letter 885, volume 2.2. Thompson (1898), 68.3. See Trinity House By Board Minutes, 1, 8, 24 October 1867, GL MS 30010/46, pp.275-6,281, 358 respectively. See also Bence Jones (1870a), 2: 91.4. See, for instance, Cantor et al. (1991), 42.5. <strong>The</strong>se letters are in a bound volume which forms GL MS 30108A/1.6. See also Bence Jones (1870a), 2: 87.7. Ibid.8. Ibid, 99.9. See also Gladstone (1874), 135.10. In the period covered by this volume this position was occupied by John Henry Pelly.<strong>The</strong> Master was the Duke <strong>of</strong> Wellington.11. Arrow (1868), 18-26 contains a useful discussion <strong>of</strong> the committee structure <strong>of</strong> theCorporation.12. <strong>The</strong> minutes <strong>of</strong> this committee commence in 1941 with volume 102. GL MS 30076/102.13. For brief overviews <strong>of</strong> Faraday's role in Trinity House see Frank A.J.L. James, "<strong>The</strong> manwho cast a new light on science", New Scientist, 17 September 1994, pp.45-6 and "TrinityHouse move unearths major cache <strong>of</strong> Faraday letters", 1EE News, 1 December 1994, p.2.

Introduction<strong>The</strong> 812 letters in this volume, <strong>of</strong> which nearly three quarters arepublished for the first time, reflect both change and continuity inFaraday's life from 1841 to 1848, that is between the ages <strong>of</strong> 49 and 57.Faraday continued to be a member <strong>of</strong> the Sandemanian Church and towork for the Royal Institution, but his role changed in both institutions.<strong>The</strong> consequences <strong>of</strong> the illness which he had suffered in 1839 remainedwith him during the whole <strong>of</strong> the 1840s. In his science, the quantity <strong>of</strong> hisoriginal research was markedly lower between 1841 and 1844 comparedto what it had been in the 1830s. Yet following his discoveries <strong>of</strong> themagneto-optical effect and <strong>of</strong> diamagnetism in late 1845, he was able toresume his scientific investigations with almost as much energy as he haddisplayed in the previous decade. He continued working for the state andits agencies, including the East India Company. He may have evendevoted more time to this, especially in the early 1840s, than he hadspent during the 1830s. Among other activities he conducted the inquiryinto the Haswell Colliery explosion for the Home Office, and continued toprovide a great deal <strong>of</strong> scientific advice to Trinity House.Although there appears to be a slight increase in the averagenumber <strong>of</strong> letters per year from 90 in volume two to 101 in this volume,this statistic hides a wide variation in the number <strong>of</strong> letters written eachyear which are given below:1841 1842 1843 1844 1845 1846 1847 184845 79 86 123 148 129 102 100Far fewer letters than the average were written in the early part <strong>of</strong>the period, far more than the average in the middle and about average atthe end. This distribution reflects quite accurately the state <strong>of</strong> Faraday'sscientific activities during these years and also suggests that theproportion <strong>of</strong> letters that have survived might be roughly constant overthe years.Most <strong>of</strong> Faraday's major correspondents during the 1830smaintained their exchange <strong>of</strong> letters with him throughout the 1840s .Only a few ceased corresponding with him or drastically reduced the

XXV111number <strong>of</strong> letters they wrote 2 . Furthermore, John Gage 3 , Jons JacobBerzelius, Percy Drummond 4 and John Frederic Daniell (with whomFaraday seldom exchanged letters because <strong>of</strong> their close geographicalproximity) were perhaps the only major correspondents Faraday lost onaccount <strong>of</strong> their deaths. <strong>The</strong>se losses were compensated for by a number<strong>of</strong> new additions to Faraday's circle <strong>of</strong> correspondents. <strong>The</strong>y include theIrish chemist Thomas Andrews, the Governor General <strong>of</strong> Canada CharlesBagot (over the appointment <strong>of</strong> the Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Chemistry at Toronto),the chemist Lyon Playfair, the geologist Gideon Algernon Mantell, theengineer James Nasmyth, the metallurgist John Percy, the physicist JuliusPliicker and the very young natural philosopher William Thomson.Faraday also resumed correspondence with John Frederick WilliamHerschel who had spent most <strong>of</strong> the 1830s at the Cape <strong>of</strong> Good Hope.By any indicator, whether <strong>of</strong> lectures delivered, letters written orpapers published, Faraday's scientific work declined sharply during thefirst half <strong>of</strong> the 1840s compared to what it had been in the 1830s. Nodoubt the after effects <strong>of</strong> the illness which he had suffered in late 1839 5played a major role in this decline. For instance at the end <strong>of</strong> 1840 theManagers <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution resolved that Faraday should considerhimself "totally exonerated from all duties connected with the RoyalInstitution till his health should be completely re-established" 6 . AlthoughFaraday attended the following meeting <strong>of</strong> the Managers 7 , it is clear fromhis letters that his health was never really "completely re-established". Aglance at the index under "Faraday, Health <strong>of</strong>" reveal the large number <strong>of</strong>references in this volume to the state <strong>of</strong> his memory, his giddiness andother illnesses. Faraday's loss <strong>of</strong> memory was not simply a matter <strong>of</strong>perception along the lines that 'Faraday's bad memory is my goodmemory', but a genuine loss. This loss is evinced, for example, by hisconfusing Manchester and Birmingham 8 and by forgetting that he hadreceived a letter from Moritz Hermann Jacobi and, indeed, had sent it tothe Royal Society 9 . Caroline Fox 10 noted in her diary on 30 May 1842,following a conversation with Richard Owen, that "Faraday is better, butgreatly annoyed by his change <strong>of</strong> memory. He remembers distinctlythings that happened long ago, but the details <strong>of</strong> present life his friends'Christian names, &c, he forgets" 11 .Though Faraday was able to continue performing manyadministrative functions for the Royal Institution, particularly in hiscapacity as Superintendent <strong>of</strong> the House, other duties were transferredelsewhere and Faraday considerably slackened <strong>of</strong>f his lecturingthere. He gave no Friday Evening Discourses in 1841, two in 1842, threein 1843, two in 1844 before returning to a pattern similar to that <strong>of</strong>the 1830s <strong>of</strong> delivering three or four Discourses each year. He gavethe Christmas lectures in 1841-2 and again in 1843-4, a series <strong>of</strong> eightlectures on electricity after Easter 1843 and a series on heat after

XXIXEaster 1844. To put it slightly differently Faraday at most only gavetwo lectures in the Royal Institution in 1841. His illness seems not onlyto have prevented him giving his accustomed number <strong>of</strong> lectures,but even extended to preventing him from taking part in the formalitythat had grown up around the Discourses. In its report on JohnBarlow's Discourse on 13 May 1842 the Literary Gazette concluded "Werejoiced to see Faraday once again occupying his old place on theend <strong>of</strong> the bench to the right <strong>of</strong> the illustrator" 12 .<strong>The</strong> position <strong>of</strong> Secretary to the committee for the ''Weekly EveningMeetings" passed at some point from Faraday to Barlow 13 . In 1843 Barlowalso took over as Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution following EdmundRobert Daniell's resignation 14 . During his period as Secretary, whichlasted until 1860, Barlow was one <strong>of</strong> the dominant figures in the RoyalInstitution. Not only did he run the lecture programme, but wasinstrumental in electing Prince Albert to membership <strong>of</strong> the RoyalInstitution 15 and in exposing the fraud <strong>of</strong> the Assistant Secretary, JosephFincher, in 1846 16 . Faraday from the mid 1840s onwards was able to helpBarlow run the Royal Institution. Thus he played a crucial role in 1848 inthe appointment <strong>of</strong> a fellow Sandemanian, Benjamin Vincent, as Fincher'sreplacement 17 . Faraday secured the agreement <strong>of</strong> eminent men <strong>of</strong>science, such as Whewell, to give Friday Evening Discourses 18 . He wasalso instrumental in securing the election <strong>of</strong> ladies to membership <strong>of</strong> theRoyal Institution through his support <strong>of</strong> Burdett Coutts and the Duchess<strong>of</strong> Northumberland 19 , though it was not until the following year thatladies were allowed in the lecture theatre on the same basis asgentlemen 20 . From such examples throughout this volume, it is apparentthat Barlow and Faraday had a good working relationship and betweenthem were responsible for the day to day running <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution.But by 1845, Faraday believed that the Royal Institution could continuewithout him if necessary 21 .Though the state <strong>of</strong> his health contributed to the reduction <strong>of</strong> hisactivities at the Royal Institution, it did not prevent him from continuingto discharge his duties as one <strong>of</strong> the three Elders <strong>of</strong> the SandemanianChurch in London. Few letters in this volume shed light on Faraday'sactivities as an Elder, a position he held from 1840 22 to 1844. <strong>The</strong> onlyletter in this period which deals with religion is to his sister in law JaneBarnard written from Switzerland in 1841 23 . But this lack <strong>of</strong> evidenceshould not disguise the fact that Faraday would have undoubtedlyattended Church every Sunday (when in London) and preached therefrequently. Furthermore, his 1842 visit to Newcastle, a city with a strongSandemanian congregation, was possibly undertaken as part <strong>of</strong> hisduties 24 . Even the most serious event that could befall a Sandemanian, hisExclusion (for reasons that are not clear) from the Church between 31March and 5 May 1844, draws only two references in his letters 25 . Though

XXXFaraday was soon readmitted as a member, he did not return to the post<strong>of</strong> Elder until 1860.Though death did not deprive Faraday <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> his correspondentsduring the 1840s, it did take many close members <strong>of</strong> his family,most <strong>of</strong> whom were also members <strong>of</strong> the Sandemanian Church. His sistersin law, Jane Barnard and Mary Reid 26 , died in 1842 and 1845 respectively,while his mother in law, Mary Barnard 27 , and his elder sister, ElizabethGray 28 , both died in 1847. But most distressing for Faraday was the death,on 13 August 1846, <strong>of</strong> his brother, Robert, following a carriage accidenttwo days earlier 29 .While some <strong>of</strong> Faraday's biblical references and discussion <strong>of</strong>religion in this volume occur in letters relating to the deaths <strong>of</strong> hisrelations 30 , most occur in letters written after his exclusion from andreadmission to the Sandemanian Church. This includes his well knownletter to Ada Lovelace in October 1844 in which he asserted '<strong>The</strong>re is nophilosophy in my religion[.] I am <strong>of</strong> a very small & despised sect <strong>of</strong>Christians known, if known at all, as Sandemanians and our hope isfounded on the faith that is in Christ" 31 . Faraday's statement that "<strong>The</strong>reis no philosophy in my religion" is misleading since it could be taken toimply that Faraday separated his science and religion into unconnectedcompartments. Yet in a lecture in 1846 Faraday told an audience at theRoyal Institution that the properties <strong>of</strong> matter "depend upon the powerwith which the Creator has gifted such matter" 32 ; religion did indeed playa crucial role in Faraday's natural philosophy, that is his science 33 .Neither his Eldership nor his health prevented Faraday fromundertaking a considerable number <strong>of</strong> commissions for the state andits agencies. In this area <strong>of</strong> Faraday's life there were also strong elements<strong>of</strong> continuity and change. For instance he continued to give his chemistrylectures to the cadets at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. Butwhereas in the 1830s he seems to have accepted most <strong>of</strong> the tasks thatthe state had asked him to do, in the 1840s he felt that he could nowchoose what he would or would not undertake. Thus in 1844 he refused todo some work for the Hydrographic Office 34 , while in 1847 he refused veryfirmly in a letter to the First Lord <strong>of</strong> the Admiralty, Lord Auckland, tocarry out research on disinfectants for the Admiralty 35 . Nevertheless, thestate's own experts acknowledged Faraday's value; as the AstronomerRoyal, George Biddell Airy, put it: "We trouble you as a universal refereeor character-counsel on all matters <strong>of</strong> science" 36 . Despite the fact thatFaraday, on occasion, was willing to turn downs commissions from thestate, the letters published in this volume are testimony to the quantityand range <strong>of</strong> scientific advice that Faraday willingly gave to the state andits agencies during the 1840s 37 .Two <strong>of</strong> the most significant pieces <strong>of</strong> work that Faraday did for thegovernment was in conducting two inquiries in 1843 and 1844. <strong>The</strong>se

XXXIwere into the explosions at the Waltham Abbey gunpowder factory and atHaswell Colliery. <strong>The</strong> gunpowder factory, run by the Ordnance Office, wasdestroyed on 13 April 1843. Faraday, who was employed by the Office atthe Royal Military Academy, was asked to report on its cause. Thisappears to have been an internal Ordnance Office inquiry. Faraday sent inhis report, published here 38 , on 20 June 1843, but it is not clear whataction, if any, was taken subsequently 39 .No such cosy arrangement was possible with the inquiry into theexplosion at Haswell Colliery carried out by Faraday, Charles Lyell andSamuel Stutchbury 40 . On the afternoon <strong>of</strong> Saturday 28 September 1844 anexplosion occurred in Haswell Colliery in the Durham coalfield whichresulted in the deaths <strong>of</strong> 95 men and boys, the youngest being three boysaged ten. <strong>The</strong> inquest was convened by the Durham coroner, ThomasChristopher Maynard, at the Railway Tavern in Haswell on 30 September.<strong>The</strong> well known Chartist, trade union leader and lawyer William ProwtingRoberts represented the families <strong>of</strong> the deceased. Roberts, who had beenactive in the miners strike in the Northumberland and Durham coalfieldswhich had lasted from April to August 1844, was described by FriedrichEngels 41 as "a terror to the mine owners" 42 .It was expected that the inquest would follow the standard patternwith the jury <strong>of</strong> farmers and shopkeepers, who were closely connectedwith the mineowners, returning verdicts <strong>of</strong> accidental death and thusexonerating the mineowners from any responsibility. Although this wasindeed the outcome, two factors forced the inquest away from such astraightforward path. First, Haswell Colliery was a relatively new minehaving opened in 1835 and was widely regarded as safe. If such a disastercould occur here what about other mines which de facto were consideredless safe? 43 . Second, the strike in the coalfield had come to an end only amonth or so before the explosion at Haswell. <strong>The</strong>se two factors gaveRoberts sufficient leverage to upset the routine <strong>of</strong> the inquest.At the end <strong>of</strong> the first day, Roberts applied for an adjournment sothat the mine could be inspected by a viewer on behalf <strong>of</strong> the bereavedfamilies 44 ). When this was declined, he made a further application foradjournment so that representatives <strong>of</strong> the government could be sent toobserve the proceedings 45 . This also was refused by the coroner.However, at the end <strong>of</strong> the third day the inquest was adjourned so thattwo mine viewers could inspect the mine. Taking advantage <strong>of</strong> thisbreak, Roberts travelled to London and thence to Brighton where hepetitioned the Tory Prime Minister Robert Peel 47 that governmentrepresentatives be sent to the inquest. This request was based on therecommendation <strong>of</strong> the 1835 report <strong>of</strong> the Commons Committee intomining disasters which suggested that the Home Secretary shouldappoint suitable experts to assist the coroner and jury at the inquestsinto fatal mining explosions 48 . Peel assented to Roberts's request and

XXX11initially suggested that Faraday and Charles Babbage be appointed 49 . <strong>The</strong>permanent Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Home Office, Samuel March Phillipps, visitedBabbage on Sunday 6 October, but Babbage evidently declined and laterwrote to Phillipps suggesting Lyell. On the seventh, Phillipps, aftershowing Babbage's letter to Peel, called on Lyell who after somepersuasion agreed to attend the inquest 50 . Presumably Phillipps alsocalled on Faraday, though there is no evidence for this.According to Lyell's recollection, over twenty years later, Faradayaccepted the task with considerable reluctance 51 . Although there is nocontemporary evidence for this reluctance, it would not have been toosurprising in view <strong>of</strong> the state <strong>of</strong> his health and his recent return from anarduous trip to York (where he had attended the meeting <strong>of</strong> the BritishAssociation at the end <strong>of</strong> September). However, by Monday 7 October,Faraday had agreed to the commission. On that day Phillipps wrote tothem jointly expressing the satisfaction <strong>of</strong> the Home Secretary, JamesGraham, that they had agreed to go 52 . He also enclosed a copy <strong>of</strong> theletter he had written to Maynard outlining the reasons for their attendingthe inquest 53 . In this letter Phillipps more than somewhat anticipated theoutcome <strong>of</strong> the inquest by referring to the explosion as an "accident".Furthermore, he made it clear to Maynard that one <strong>of</strong> the functions <strong>of</strong> thepresence <strong>of</strong> Faraday and Lyell was to ensure that the "verdict would bedelivered under the best possible recommendation and with the highestsanction".On Tuesday 8 October Faraday and Lyell travelled by train toHaswell and were joined by Stutchbury, who was a mine viewer from theDuchy <strong>of</strong> Cornwall. Stutchbury's presence was due to Lyell's insistencethat he and Faraday must have a practical man to help them with theirwork 54 . After the week long adjournment, the inquest resumed on 9October with Faraday and Lyell present. Maynard announced thatFaraday and Lyell "had been sent down by the government to assist inthe investigation" 55 . Lyell, who had originally trained as a lawyer, laterrecounted that "Faraday began, after a few minutes, being seated next thecoroner, to cross-examine the witnesses with as much tact, skill, and selfpossessionas if he had been an old practitioner at the Bar" 56 . Thisrecollection is supported by contemporary accounts <strong>of</strong> the inquest whereFaraday, and to a lesser extent Lyell, played a major role in theproceedings 57 . On 10 October Faraday, Lyell and Stutchbury spent sevenor eight hours examining the mine. <strong>The</strong>re they investigated the air flow inthe mine and identified some laxity in the safety procedures. Thus, muchto his consternation, Faraday found that he was sitting on a bag <strong>of</strong>gunpowder while a naked candle was in use: "He sprung up on his feet,and, in a most animated and expressive style, expostulated with them fortheir carelessness" 58 .On the final day <strong>of</strong> the inquest Stutchbury gave his account <strong>of</strong> the

xxxiiiprevious day's visit to the mine 59 . This was enough for the jury to say thatthey had heard sufficient evidence for them to come to a verdict. Afterretiring for ten minutes the jury returned verdicts <strong>of</strong> accidental deathwhich Faraday noted with the comment "fully agree with them" 60 .Faraday and Lyell expressed this view in their initial report to Phillipps 61 .After generously contributing to the subscription fund for the widowsand orphans 62 , Faraday and Lyell returned to London the following day,Saturday 12 October. By agreeing immediately to Roberts's request toappoint experts to attend the Haswell inquest, Peel was able to silenceany potential trade union opposition to the coroner's verdict; thegovernment had, after all, done what Roberts had requested. This pointwas made explicitly by Graham in a letter to Lord Londonderry 63 : "Mr.Roberts cannot urge a single complaint against the impartiality andprocess <strong>of</strong> this investigation. <strong>The</strong> most able and scientific Assistantsaided the Coroner and his Jury in this Enquiry" 64 . <strong>The</strong>re the matter mighthave rested, except that in their letter to Phillipps, Faraday and Lyell saidthey would draw up a report dealing the cause <strong>of</strong> such accidents.While they were writing this report, it became apparent that thepossibilities <strong>of</strong> using legislation to improve safety were severely limited.On 19 October 1844 Lyell reported a conversation with Francis Baring,who had been Chancellor <strong>of</strong> the Exchequer in the Whig government from1839 to 1841, in which he had expressed his horror at legislativeinterference in the mining industry 65 . Nevertheless, on 21 October 1844,Faraday and Lyell submitted their report. <strong>The</strong> government initiallyreacted favourably to the report which they published as a pamphlet 66and distributed widely 67 . <strong>The</strong> report made a number <strong>of</strong> recommendationsand contained the novel observation that coal dust had played a majorrole in the explosion 68 . <strong>The</strong> recommendations were mainly concernedwith fire damp (methane) and included the suggestion that the fire dampshould be drawn away from the mine by specially made conduits 69 . <strong>The</strong>yalso recommended, and this seems to be Lyell's contribution to thereport, that miners should be better educated 70By March 1845 following the publication <strong>of</strong> the unfavourablereactions <strong>of</strong> the mineowners to Faraday and Lyell's report, in which, forinstance, they claimed it would cost £21,000 to ventilate the mineaccording to the methods suggested by Lyell and Faraday 71 , thegovernment was asked in Parliament whether it was intended toimplement the recommendations contained in the report 72 . <strong>The</strong>government initially played for time and asked Faraday and Lyell fortheir response to the mineowners. <strong>The</strong>y commented that ventilation suchas they proposed would cost about S136 73 .<strong>The</strong> government clearly wished to avoid explicitly answering thequestion about the implementation <strong>of</strong> the report. To have supported themineowners by rejecting the report would have antagonised a

XXXIVconsiderable section <strong>of</strong> public opinion concerned about conditions in themines. To have supported the miners would have annoyed themineowners, such as Londonderry, who carried considerable politicalweight within Parliament 74 . <strong>The</strong> result was a piece <strong>of</strong> finesse by thegovernment who tabled the report in the House <strong>of</strong> Commons onThursday 17 April 1845 75 during the debate on second reading <strong>of</strong> thehighly contentious Maynooth Endowment Bill 76 . This manoeuvre ensuredthat no further notice was paid to the contents <strong>of</strong> the report, includingthe discovery that coal dust was an explosive agent, which wasrediscovered later in the century 77 . Whatever the rights and wrongs <strong>of</strong>this complex story, its ending did not bear out the hopes <strong>of</strong> Roberts,though Engels was unaware <strong>of</strong> this 78 . Whether Faraday and Lyell wereaware <strong>of</strong> the political implications and manoeuvrings surrounding theirreport is not clear. However, they appear not to have held any grievanceagainst Peel for they both presented him with copies <strong>of</strong> their next majorpublications with suitably flattering letters 79 .As with his direct work for government departments, the state <strong>of</strong>Faraday's health did not prevent him from continuing to provideextensive advice to Trinity House 80 . Some <strong>of</strong> this entailed analysingwater from various lighthouses 81 . Less mundanely, Faraday considered aproposal to use electricity to light buoys, but dismissed this proposal asimpractical 82 . However, during the 1840s most <strong>of</strong> Faraday's efforts forTrinity House were directed towards the problem <strong>of</strong> ventilation. Hecommenced investigating this in February 1841 following his visit to StCatherine's Lighthouse on the Isle <strong>of</strong> Wight. <strong>The</strong> problem facing Faradaywas how to remove from the lighthouse lanthorn the products <strong>of</strong>combustion that condensed on the outer glass which thus reduced theamount <strong>of</strong> light emitted. Faraday worked on developing a chimney whichwould carry away these products without at the same time interferingwith the light emitted by the flame. He had a chimney installed in StCatherine's Lighthouse which, judging by the graphic descriptionprovided by the keeper two years later, proved very successful. ButFaraday realised that there were other sources <strong>of</strong> moisture in thelighthouse which he was also able to eliminate 85 . His continuedinvestigation <strong>of</strong> ventilation systems required him to visit the SouthForeland Lighthouse on the Kent coast on several occasions 86 . In thisprocess he developed a new design <strong>of</strong> chimney, which he made over, in1842, to his brother, Robert, who patented it the following year 87 ; the onlyinvention <strong>of</strong> Faraday's to be patented. This chimney was quite successfuland it was installed in buildings other than lighthouses including theAthenaeum 88 and Buckingham Palace where, as the Times noted,Faraday's lamp illuminated Princess Helena's christening 89 .<strong>The</strong> tasks that Faraday undertook for the state reduced, as he wasperfectly well aware, the amount <strong>of</strong> time he could devote to research.

XXXVThis was a point he made explicitly to Francis Beaufort in 1844: "I havebeen so long delayed from my own researches by investigations &inquiries not my own that I must now resume the former" 90 . During theearly 1840s Faraday was clearly capable <strong>of</strong> working, but not on science.Since Faraday was able to work and yet produce little original research,this suggests that he did not have a strategy by which he could pursuehis scientific work.By the end <strong>of</strong> the 1830s, Faraday had completed the researchprogramme that he had set out in his 1822 Notebook 91 . He knew thathe wanted to make magnetism a universal force <strong>of</strong> nature rather thanone specific to two substances (iron and nickel) and he wanted todevelop and sustain experimentally an alternative theory <strong>of</strong> matterto Daltonian atoms 92 . In 1840 he did not know how he would solvethese problems, and indeed throughout the first half <strong>of</strong> the 1840s heseems to have doubted if he would make any useful contribution toscience again 93 . This probably accounts for his bringing out the secondvolume <strong>of</strong> Experimental Researches in Electricity 94 in late 1844 95 . Thisvolume reprinted series 15 to 18 and about thirty <strong>of</strong> his other papersand thus lacks the coherence <strong>of</strong> volume one 96 . Since Faraday clearlybelieved that his scientific career was over, the production <strong>of</strong> sucha volume was an entirely appropriate thing to do. He did not then havea research strategy which would allow him to make the furtherscientific discoveries he wanted. Thus one could argue that Faradayallowed himself to undertake the work he did for the state becausehe did not know which path <strong>of</strong> scientific experimentation would leadto the results he desired. In this context it is significant that hiscomment to Beaufort in 1844 about wishing do research rather thanwork for the government 97 occurred just as he was beginning toresume sustained experimentation.Faraday's resumption <strong>of</strong> experimentation and the commencement <strong>of</strong>feeling his way towards resolving his problems in science began in aFriday Evening Discourse he gave on 20 January 1843 when he posed thefollowing paradox: In metals, space was a conductor <strong>of</strong> electricity,whereas it behaved as an insulator in non conductors 98 . This wasprecisely the question which Faraday proposed a year later in his FridayEvening Discourse <strong>of</strong> 19 January 1844 "A Speculation touching ElectricConduction and the Nature <strong>of</strong> Matter" which was quickly published in thePhilosophical Magazine". In both the Discourse and in the paper Faradayargued that the question could not be resolved in terms <strong>of</strong> Dalton'satomic theory. Instead he proposed point atoms where lines <strong>of</strong> forcewould meet. <strong>The</strong> physical properties <strong>of</strong> chemical elements would be theresult particular combinations <strong>of</strong> lines <strong>of</strong> force meeting at a point. Hecontinued his thoughts on the topic semi-privately the following month ina memorandum on "Matter" 100 .

XXXVIFaraday had thus made some progress with a theory <strong>of</strong> matter, butnot with the problem <strong>of</strong> raising magnetism to the status <strong>of</strong> a universalforce <strong>of</strong> nature. Indeed these two problems were now linked in Faraday'smind. <strong>The</strong> atoms that he had proposed must be structurally similar toeach other; it would therefore be peculiar if only iron and nickel evincedmagnetic properties. Thus during 1845 Faraday set about trying to obtainmagnetic effects from a wide range <strong>of</strong> materials, but he only succeededwith cobalt 101 . This work included cooling about forty materials to -166°Fto see if they became magnetic, but none did 102 . In June Faraday attendedthe annual meeting <strong>of</strong> the British Association in Cambridge where he metWilliam Thomson, just then coming <strong>of</strong> age, and who had earlier dismissedFaraday's approach to science. In March 1843 the eighteen year oldThomson noted "I have been reading Daniell's book & the account hegives <strong>of</strong> Faraday's researches. I have been very much disgusted with hisway <strong>of</strong> speaking <strong>of</strong> the phenomena, for his theory can be called nothingelse" 103 . However, it is evident from their letters that following theirmeeting in Cambridge that they got on very well 104 . In August 1845, a fewmonths after they had met, Thomson wrote asking Faraday what effect atransparent dielectric would have on polarised light 105 . Faraday repliedthat he had tried the experiment, but had found no result; referringThomson to the relevant publication he added that he proposed toreinvestigate the topic 106 .<strong>The</strong> opportunity to repeat these experiments occurred at the end <strong>of</strong>August when he was asked by Trinity House to test four argand lamps 107 .By 30 August Faraday was using an argand lamp to repeat his experimentson passing light through electrolytes 108 . He continued his experimentsinto the beginning <strong>of</strong> September but with the same negative result 109 .However, in this set <strong>of</strong> experiments Faraday used a piece <strong>of</strong> heavy opticallead borate glass that he had made in the late 1820s . When he was nextin the laboratory, on 13 September, he decided to examine the effect <strong>of</strong> apowerful electro-magnet on polarised light through various media. Whenhe passed the light through the heavy glass he observed that its state <strong>of</strong>polarisation was changed: "thus magnetic force and light were proved tohave relation to each other" 111 . Faraday was fortunate in using a piece <strong>of</strong>glass with a high lead content since this produced a high specificmagnetic rotation 112 . Thus Faraday's discovery <strong>of</strong> the magneto-opticaleffect was contingent on his earlier work in making optical glass and onhis work for Trinity House 113 .<strong>The</strong> transparent bodies which he found displayed this property hecalled "dimagnetics" 114 ) in analogy with dielectrics 1 . Faraday had madetwo discoveries. First that somehow light and magnetism were connectedand, second, that glass was susceptible to magnetic force. <strong>The</strong> latter was<strong>of</strong> greater interest to him since he soon turned his attention to showingthat the glass was directly susceptible to magnetic force. He failed to find

xxxvnany effect on 6 October 116 . However, on 4 November when he hung thepiece <strong>of</strong> heavy glass between the poles <strong>of</strong> an electro-magnet, he observed,when he turned the magnet on that the glass aligned equatoriallybetween the poles: "I found I could affect it by the Magnetic forces andgive it position; thus touching dimagnetics by magnetic curves andobserving a property quite independent <strong>of</strong> light, by which also we mayprobably trace these forces into opaque and other bodies" 117 . Within aweek Faraday had taken full advantage <strong>of</strong> this discovery and had foundthat more than fifty substances were susceptible to magnetic force andexhibited the behaviour <strong>of</strong> either iron or heavy glass 118 ; however, gaseseluded him. It was in this context that Faraday introduced the term"magnetic field" into natural philosophy 119 , although he did not use it inhis correspondence until 1848 120 .Faraday realised very early on that with magneto-optics anddiamagnetism 121 he had made discoveries <strong>of</strong> fundamental physicalimportance. In his letter to Schoenbein where he gave a very briefaccount <strong>of</strong> his work he remarked on its significance: u You can hardlyimagine how I am struggling to exert my poetical ideas just now for thediscovery <strong>of</strong> analogies - & remote figures respecting the earth Sun & allsorts <strong>of</strong> things" 122 . <strong>The</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> this discovery merited Faradaypursuing a similar epistemological strategy to the one he had adopted in1822 for displaying the reality <strong>of</strong> his 1821 discovery <strong>of</strong> electro-magneticrotations 123 . In that case he distributed to several men <strong>of</strong> science 'pocket'electro-magnetic rotation devices that readily displayed the phenomenon.Though news <strong>of</strong> his discoveries <strong>of</strong> the magneto-optical effect anddiamagnetism quickly and widely spread 124 , these phenomena weresubjected to interpretations different from those proposed by Faraday 125 .But, his discoveries <strong>of</strong> 1845 required much more apparatus, which wasnot readily available, than electro-magnetic rotations had done. Faradaytackled this problem in two ways in 1846. First by sending out samples <strong>of</strong>the heavy glass to a number <strong>of</strong> savants throughout Europe 12 and,second, by inviting a small number <strong>of</strong> people into his basementlaboratory to view the magneto-optical experiments 127 and later thediamagnetic experiments 128 .By making magnetism a universal force <strong>of</strong> nature, Faraday hadplaced himself in a position to argue strongly for his view <strong>of</strong> the nature <strong>of</strong>matter. This he proceeded to do in his Friday Evening Discourse <strong>of</strong> 3 April1846 which included his "Thoughts on Ray-vibrations" 129 . Instead <strong>of</strong>Daltonian atoms immersed in a luminiferous aether, Faraday proposedhis notion <strong>of</strong> points distributed throughout space where lines <strong>of</strong> forcemet as chemical atoms and where the vibrations <strong>of</strong> the lines <strong>of</strong> forceproduced light: "<strong>The</strong> view which I am so bold as to put forth considers,therefore, radiation as a high species <strong>of</strong> vibration in the lines <strong>of</strong> forcewhich are known to connect particles and also masses <strong>of</strong> matter together.

XXXV111It endeavours to dismiss the aether, but not the vibrations" 130 , InFaraday's view "<strong>The</strong> smallest atom <strong>of</strong> matter on the earth acts directly onthe smallest atom on matter in the sun" 131 . Such views, especially thosequestioning the existence <strong>of</strong> the aether, did not go unchallenged 132 andwere not accepted until after the period covered by this volume 133 .Another consequence <strong>of</strong> Faraday's discoveries was that he attractedthe attention <strong>of</strong> several mesmerisers. Following the publication <strong>of</strong> hiswork 134 , he received a number <strong>of</strong> letters which discussed mesmericphenomena in great detail. Thus John Battishill Parker explicitly linkedFaraday's discovery <strong>of</strong> diamagnetism with mesmerism: "On perusing the21st Series <strong>of</strong> the Philosophical Transactions containing your ExperimentalResearches on Electricity, I am delighted to think that you areapproaching to a solution <strong>of</strong> the true <strong>The</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> Mesmerism" 135 . Althoughthis is the only letter which makes the link explicit, it cannot be acoincidence that all but one 136 <strong>of</strong> these letters 1 were sent after thepublication <strong>of</strong> Faraday's work on diamagnetism. Walter White 138 noted inhis diary a conversation with Faraday on 14 March 1846 in which Faradaysaid that he was "not disposed to place faith in the magnetic experiments<strong>of</strong> Reichenbach, and says that, as <strong>of</strong> mesmerism, so he cannot believe inthem until their law is found to be <strong>of</strong> invariable application, until they canmesmerise inorganic matter or a baby, who cannot be supposed to be aconfederate. He has lost much time in the enquiry without anysatisfactory results" 139 . Before then Faraday had not taken much interestin mesmerism 140 . <strong>The</strong> views he expressed to White on the subject coherewith his dismissive endorsement <strong>of</strong> "Mesmeric stuff" on Jane Jennings'sfirst letter to him 141 . However, it should be remembered that hepreserved these letters, but perhaps the reasons were the same asthose that prompted him to keep other letters which expressedheterodox views on physical and chemical subjects 142 .Despite the various problems which Faraday experienced during the1840s, he retained the respect and admiration <strong>of</strong> his peers, both inscience and in the service <strong>of</strong> the state. This was made clear throughnumerous letters and in frequent enquiries about health, in urgings not toovertax himself and in invitations to Levees 143 . Admiration for Faradaywas also made clear in two tangible actions by the scientific community,one public and the other fairly private. <strong>The</strong> first was his election in 1844(that is before his discoveries <strong>of</strong> the magneto-optical effect anddiamagnetism) as one <strong>of</strong> the eight associe etranger <strong>of</strong> the Academie desSciences in Paris. <strong>The</strong> vacancy had occurred following the death <strong>of</strong>Dalton. <strong>The</strong> campaign to replace him with Faraday was led by Dumas withthe support <strong>of</strong> Dominique Francois Jean Arago, Antoine-Cesar Becquereland Michel Eugene Chevreul and others. Dumas wrote to Faraday inDecember 1844 saying that he had been nominated, but that he was onthe second line <strong>of</strong> the ballot paper because the mathematicians wanted