EMILE HIRSCH EWAN MCGREGOR JAVIER BARDEM - Mean

EMILE HIRSCH EWAN MCGREGOR JAVIER BARDEM - Mean

EMILE HIRSCH EWAN MCGREGOR JAVIER BARDEM - Mean

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

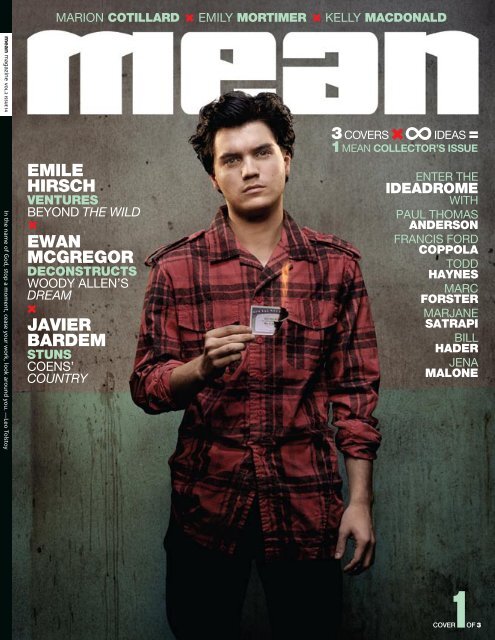

+marion cotillard Emily Mortimer Kelly Macdonald+mean magazine vol.2 issue 14 In the name of God, stop a moment, cease your work, look around you. —Leo Tolstoy++emilehirschVenturesBeyond the WildewanmcgregorDeconstructsWoody Allen’sDreamjavierbardemSTUNSCoens’Country3 ∞Covers Ideas =+1MEAN Collector’s IssueEnter theIdeadromewithPaul ThomasAndersonFrancis FordCoppolaToddHaynesMarcForsterMarjaneSatrapiBillHaderjenamalone1cover of 3

+marion cotillard Emily Mortimer Kelly Macdonald+mean magazine vol.2 issue 14 My one regret in life is that I am not someone else. —Woody Allen++ewanmcgregorDeconstructsWoody Allen’sDreamemilehirschVenturesBeyond theWildjavierbardemSTUNSCoens’Country3 ∞Covers Ideas =+1MEAN Collector’s IssueEnter theIdeadromewithPaul ThomasAndersonFrancis FordCoppolaToddHaynesMarcForsterMarjaneSatrapiBillHaderjenamalone2cover of 3

contentsmean volume 2, issue 1432 The Role LessTraveledGentleman-adventurer Ewan McGregorawakens to Woody Allen’s Cassandra’s Dream42 Buck WildInto the Wild’s Emile Hirsch traverses thepath from youth to young manhood50 Old SoulSpanish actor and No Country for Old Menstar Javier Bardem gives no quarter58 A Lucky ScotThe rising fortunes of Oscar-bound bonnieKelly Macdonald64 Emily Ever AfterShockingly, Oxford-schooled thespianEmily Mortimer loves ice dancing, Russiangirls with gold teeth and just about anythingthat’s ever been on television74 Present, Past& PerfectNot to worry—Jennifer Jason Leigh knowsyou’re still freaked out by her role in SingleWhite Female. She gets that a lot. But whatis she up to these days?And: filmmaker Richard Shepard on hisfavorite J.J.L. performances82 Belle on the BallLa Vie en Rose’s likely Oscar contenderMarion Cotillard is… How you say?A smart cookie.84 Places In The HeartActress-singer-songwriter-wild child JenaMalone shares her poems and journal entries88 Blood From OilPaul Thomas Anderson’s science of alchemy94 Still Knockin’On Heaven’s DoorThe return of Francis Ford Coppola98 Stronger Than FictionThe Kite Runner’s Marc Forster100 Seeing the RealHim, At LastGetting schooled by Dylan biopic directorTodd Haynes102 At Home InThe WorldThe bittersweet wisdom of graphic novelauthor and filmmaker Marjane SatrapiCONTINUED »COVER 1 & THIS PAGE: Emile Hirsch photographed byPatrick Hoelck, COVER 2: Ewan McGregor photographedby Rankin, COVER 3: Javier Bardem photographed byKurt IswarienkoA FILM BY JEAN-LUC GODARD

contentsmean volume 2, issue 14« CONTINUED14 MEAN OPTICThe kaleidoscopic art of RachellSumpter. Also, Q&A’s with cartoonistTravis Millard and stencil art forefatherBlek Le Rat. Plus: Devofrontman Mark Mothersbaugh’slatest home-design venture17 MEAN CHICBoutiques Seven and OpeningCeremony, and fun fall fashionfrom Abigail Lorick, AlbertusSwanepoel and Laura Poretzky23 MEAN BEATJamie T, The Fiery Furnaces,Andrew Bird, DJ MathieuSchreyer, Roberty Wyatt &The Misshapes give good music104 CAPTURINGJennifer Carpenter moves beyondThe Exorcism of Emily Rose while stillkeeping things nice and gory inShowtime’s serial-murderer seriesDexter. Alexandra Maria Laraloves the fact Francis Ford Coppolahand-picked her to star in YouthWithout Youth106 REVIEWSOur customary DVD + CD reviews.Plus, an interview with legendaryincendiary wit George Carlin108 GAMESFreedom of choice: The only choicefor Next-Gen gamers110 MEAN GADGETSThe perfect projector, a helmet cam torecord your latest skydive and thesharpest music mixing software around.111 MEAN WHIPLASHGetting all Mad Max with a slick, newelectric motorcycle and Italian scooter.Also, a way to stay in shape when thebike gang rolls on without you112 MEANSANITYBill Hader and Bob Zmuda debate thepossibly faked death of comedy god AndyKaufman. Also, a chapter from the futurebiography of The Office’s B.J. Novak,and a psycho-therapist’s evaluation ofpresidential contenders Hillary Clintonand Rudy Giuliani120 GET MEAN WITHTODD RASSMUNSENWhen our resident pop culturecolumnist gets imbedded in Hollywood,he develops a mysterious allergicreaction to his environsTHIS PAGE: Javier Bardem photographed byKurt Iswarienko

CHOCOLATE WAXWEAR INDUSTRIAL FIELD BAG $325TRAVEL BAGS, TRENCHCOATS, GENERAL MERCHANDISE56 Greene Street New York City 10012TEL 212.625.1820 JACKSPADE.COM

MEnOpticblek le rat& travis millardon “world” tour BY JESSICA JARDINEisland lifethe explorations of rachell sumpter BY VALERIE PALMERArtist Rachell Sumpter likes a goodadventure. Living without running water orelectricity in a cabin on an island in PugetSound’s San Juan Archipelago, as she currentlydoes, seems to qualify as one. “Weactually get our water from a well,” shenotes matter-of-factly. She also hikes outto a specific spot on her island in order toget a signal on her cell phone or tap intothe wireless connection from one of thenearby islands, so if you get an email fromher, keep in mind that she might have hadto sit on a rock in the rain while pecking ather laptop. “It’s sort of like daily entertainment,”she says of her attempts to communicatewith the outside world.It wasn’t always like this. Sumpter spentmost of her 20s in places like the Bay Area,where she grew up, and Los Angeles,where she studied art. There were someuncertain, wavering years in the interim;years of trial and error. Her initial plan tostudy neuroscience went awry, and heridea to be a graphic designer lost its lusterwhen she enrolled in art school and foundherself surrounded by other arty types forthe first time. “I think that was the bigthing for me because I didn’t know anyartists except for my grandma, who gaveup making art to be a mother,” Sumptersays. “I didn’t really know anyone who wasmaking art, so it was kind of hard for me. Ididn’t want to be Van Gogh, cutting off myear and going crazy.”Once she realized that desperation andhardship weren’t prerequisites for being anartist, Sumpter re-focused her attention onbecoming one. After receiving a BFA fromPasadena’s Art Center in 2003, she beganshowing in Los Angeles galleries and designingbook covers to pay the bills. Amongher most recent accomplishments: Shecontributed the cover artwork for Dave Eggers’newest novel, What Is the What, anda pictorial of gloomy illustrations, inspiredby Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, to the latestissue of McSweeney’s Quarterly.Sumpter’s current body of work dealsexclusively with people living in arcticconditions, whom she defines not as anyone particular cultural group, but as anarchetype: “People who survive in cold climatesor need the cold climates to continuetheir lifestyle.” In Sumpter’s fascinationwith this dying breed there’s an implicitawareness that environmental erosion inevitablyleads to the demise of peoples andcultures. “The [need for the] preservationof things—or their lack of being able topreserve things—is intrinsic to my interestin their lifestyle,” she says.After the vernissage of her latest showat Boston’s Allston Skirt Gallery in early fall,Sumpter returned back to her little island,where she’s now getting ready for winter.Chopping firewood is part of her preparation.“Otherwise, you know, I don’t getshowers,” she says. “Warm showers arereally nice and something I don’t want tolive without.”Clearly, there are some limits to her thirstfor adventure. She may paint arctic natives,but she’s still a California girl at heart.More Rachell Sumpter atrachellsumpter.comThese days, urban art strugglesless for display space in tony galleriesand respectable museums,but exhibits like the ongoing ScionInstallation Art Tour still provide awelcome platform for grassrootsartists to showcase their work.On its current, fourth, go-around,the Tour rolls through nine cities,includes a pit stop at Miami’sArt Basel art fair this winter, andconcludes in Los Angeles next year.Over 150 contemporary artistsworking in various media (photography,painting, collage) took theshow’s current theme—“A BeautifulWorld”—as an inspiration pointfor their contributions, all of whichare to be auctioned off for charityafter the tour winds down. Wepicked two favorite heavy hittersinvolved in this present round—legendary French painter/stencilistBlek Le Rat and L.A.–based collage/comic-bookartist Travis Millard—andblitz-interviewed them.Blek Le RatHow did you choose to interpret “A Beautiful World”?“It’s a Beautiful World” can be interpreted in two senses: Oneis that life and nature and people are beautiful. But on theother hand, I wanted to talk, and not in cynical terms, abouthow sometimes the worst situation in life, for example, in warthe death of a little girl can bring a human reaction from asoldier and he cries. In my opinion there is beauty in an imageof humanity in the horror of the war.You began using stencils as graffiti art in Paris in the early’80s and have gone on to inspire everyone from ShepardFairey to Banksy.You mention Shepard Fairey who, in my humble opinion, is oneof the two stencil artists I respect most. Shepard and Banksyboth use stencils, but in a very different way, and they havetheir own eccentricity. Although Banksy’s stencils are similar tomine, he has found his proper way to get the message across,while Shepard has generated a very new style aesthetically. Hisconcept of the propaganda of his art is something that I havenever seen before, and is a really strong one.You’ve expressed a desire to stencil the Great Wall ofChina. Has that happened yet?Unfortunately, not yet. But I can’t wait to make this dreamcome true. I love to work in places soaked with history, wherethe stones [retain] the memory of what happened before. Forexample, last summer I worked in Nevada on the ruins of an ancientsilver mine. I pasted three images of a family of pioneersfrom the 19th century. This kind of work is my favorite action,and as inspiring as the walls of the city.Travis MillardTell us a bit about your company, Fudge FactoryComics, as well as your new book, Hey Fudge.Goodness gracious! Well, it’s a company alright—let’snot mistake that. There’s lots of paper-shuffling,staple-clacking, pencil-sharpening, phones doing theirthing… a water cooler, many other things. Recently,Narrow Books released Hey Fudge, a 240-page bookcollecting the last few years’ worth of my mini-zinecomics, photos and drawings.There’s a lot of talk these days about the vibrant,burgeoning contemporary art scene in Los Angeles,especially in East L.A. and Downtown. As anL.A. artist, what are your thoughts about this?My satellite gab scanner has been on the fritz for a fewweeks, but the last thing I picked up was somethingabout “the keg running low” and “going out forcheeseburgers.” There’s been great art coming out ofLos Angeles for decades, and it seems like now, morethan ever, there are opportunities for artists to get theirwork on the wall.Besides participating in this Scion Installation ArtTour and putting out Hey Fudge, what else is onthe horizon for you?Two hard-boiled eggs.14 november-december opticmean

wa lteria livingHOME SPACE ODDITIES BY VALERIE PALMER“It’s not like we’re out to change the bottle openers ofthe world—we’re just having fun,” Mark Mothersbaughquips about his latest venture, Walteria Living, a designcompany run by himself, his wife Anita and designerKathleen Walsh. The ethos of the line—a blend of humor,high design and kitsch—is evident in curios like Walsh’sporcelain Chihuahua nightlight and a series of (otherwise)traditional plates and vases adorned with Mothersbaugh’sdrawings and manipulated designs. As you’d expect fromany project concocted by the Devo frontman, there’s a littleironic twist to each piece, a dash of gleeful irreverence—maybe even some mischief.Mothersbaugh has always had an art habit. “Somepeople play tennis every day. Some people have a martinievery afternoon,” he explains. “I draw.” So what beganas small, postcard-size drawings sent home to friendsand family during worldwide Devo tours has been resurrected,postmarks and all, for a “Postcard Diaries” series ofdesigns transferred to plates, vases and even carpets producedunder the Walteria Living moniker. “They’re called‘postcard diaries’ because I used to do them on postcardsexclusively,” Mothersbaugh says. “I got into it during a timewhen mail art was a big thing.”Many of his sketches were never intended for publicconsumption; he simply doodled in response to the worldaround him. Whether it was the VP of a record companyoverfilled with self-importance or some guy raising a fuss inthe next aisle on the airplane, Mothersbaugh got it all downon paper. Even now, with two small daughters and a steadystream of film and TV scores to hammer out, he still finds thespare time to scribble something every day.To the multi-talented artist, creative expression is agiven. What renders this project particularly worthwhile,he insists, is the thought of people eating off platesembellished with his diary entries, or the possibility thatsmall children might inadvertently smash the vases he codesigned.“The idea of invading people’s homes with yourimagery—there’s something satisfying about that,” Mothersbaughsays. “Everything is art first, function second,” hiswife Anita chimes in, adding that the images do really drivethe product, in keeping with the Walteria Living mantra: “Alittle bit of art in everything you do.”The kitschy pièce de résistance in the current collection isa cuckoo clock, cast in porcelain and adorned with Mothersbaugh’smanipulated Black Forest design. He also composedthe clock’s chime: six seconds of a celeste, pizzicato, celloand electric organ that will remind you every hour on thehour—with a wink and a mischievous grin—that time isindeed passing.More cuckoo clocks & other charming curios atwalterialiving.comOPENING CEREMONY PHOTOGRAPHS BY ISABEL ASHA PENZLIENMEnchicstanding on ceremonyL.A. ARM OF NYC BOUTIQUE MAKES A SPLASH BY CHLOE POPESCUOpening Ceremony is the kind of store you want tostay a secret forever. But hip Angelenos (the kind who wearRay-Bans and don’t brush their hair) have already ferretedout the tiny gem tucked between a diner and a car washon L.A.’s La Cienega Boulevard. And by the sight of franticfashionistas running back and forth collecting plaid shirtsand ink-washed skinny jeans, you can tell that stylists havealready claimed it as their turf, too.Housed in a building that used to serve as CharlieChaplin’s dance studio, Opening Ceremony is the WestCoast counterpart to the New York boutique Carol Lim andHumberto Leon launched in September 2002. Opened justseveral months ago, the L.A. space embraces you from themoment you pass through the vintage-looking wood-andfrostedglass door. The space itself feels less like a storeand more like a home. Walking through the more than 10rooms, closets and nooks is akin to strolling through anestate sale where you get to check out both trendy threadsand trendy folk. The door knobs and windows in the storeare all original hardware, as are the two huge walk-in safeson the premises.The front room displays the latest collection of OpeningCeremony’s eponymous line, designed in-house. Atthe back of the boutique one stumbles over a men’sarea equipped with everything from Cheap Monday andAcne Jeans to tighty-whities hanging on a clothesline.There is also a small book-selling nook, where one canperuse coffee table tomes on Mexican architecture, aswell as CDs.A narrow hallway lined with cases displaying neon-huedvintage sunglasses and antique jewelry leads the visitor tothe Brazilian Room—devoted to South American designers—and,farther down, into the Swedish Room. OpeningCeremony also stocks an impressive array of items fromBritain’s cherished Topshop label: the entire Kate MossTopshop collection, as well as linen dresses, silk shorts, totebags, and Celia Birtwell for Topshop lingerie—the latterdisplayed in a vintage suitcase.The overall vibe is classic chic/urban urchin—thinkAnna Karina and Cory Kennedy. Established labels likePeter Jensen, Proenza Schouler and Mayle rub shoulderswith upstart hipster faves Alexander Wang, Rodarte andKaty Rodriguez. Further funking up the scene are leggingofferings from Jeremy Scot, and metallic trench coats byL’Wren Scott.Everything from the music (when this writer visited thestore, it was the funky beats of M.I.A.) to the décor feelsspecial and one-of-a-kind. Every year, Opening Ceremonyspotlights a different country’s underground and high-enddesigners. In the past, this has meant that Sweden andJapan got their due, but this year, to celebrate the openingof the very first West Coast location, the theme hasshifted to highlight an L.A. vs. NYC rivalry. Swing by to seehow the Southland-bred lines hold up against (supposedly)more fashion-savvy NYC ones.Visit openingceremony.us16 november-december meanchic

MEnchicto the manners bornABIGAIL LORICK’S POLITE DEBUT BY ERIN SKRYPEKNot just another model-turned-designer, Abigail Lorickis someone who aims to refine fashion. Sickened by thelack of good manners in today’s harried world, Miss Lorickis imposing propriety through her clothes. The looks sheproposes might be covered-up and ladylike, but they alsofit like a glove, hugging a woman’s curves and celebratingthe inherent sexiness of her figure. Speaking of gloves,Lorick’s making those, too. And while an underlying senseof decorum and well-mannered charm will set any collectionof clothes apart these days, what’s truly unique aboutLorick’s eponymous startup label is that it has a starring rolein the series Gossip Girl— a sort of Beverly Hills: 90210 forGeneration Y debuting on the CW network this fall.We asked Lorick to give us a behind-the-scenes glimpseat her new venture.Describe this new collection of yours.It’s about a modern-day lady, a Lorick Lady. She has thefabulous jacket, the great scarves and, of course, properetiquette.Spring/Summer 2008 is your debut season, yet LorickLady is already pretty famous.Well… my clothes are featured in Gossip Girl, a newfashion-driven television series that just launched this fallon the CW network. Eric Daman, who also worked onSex and the City, is heading the wardrobe department.There is a character in the show, Eleanor Waldorf, whois a fashion designer and has her line picked up by HenriBendel. Lorick is the collection behind The Eleanor Waldorfcollection—I’m the person who really designs all theclothes. It is pretty exciting that the collection is going tobe seen all over the world. They thought it would be funnyto put me in the show as Eleanor’s assistant. I had fun beingon set and playing with the clothes, pretending like Iwas indeed a fashion assistant. There is one scene wherethe girls actually steal one of my jackets…Where are you from?I am originally from Amelia Island, which is the northernpart of Florida, just below Georgia. [Over there] we stillindulge ourselves with grits, bourbon and hospitality.Ah… fabled Southern charm! Where does yourknowledge of proper etiquette come from?More from my grandmother than my mother. When Iwas younger I found the manners [I had been taught] tooconstricting, but as I began to travel, I learned that everyculture has its own manners and customs, and that this isa beautiful aspect of life. “When a Lorick Lady travels, sheknows it is her duty to study local traditions and values;thus she will never make another feel uncomfortableeven in foreign lands”—that’s one of the written rulesof a Lorick Lady.What were you doing before you started designingthe line?I was modeling for many years and then I began designingfor a small label known as T.S. Dixin.Your future plans for the new line are…?I want it to grow and mature from season to season, as ourladies do. I wish for the Lorick collection clothes to becomestaples in every woman’s closet, always accentuating feelingsof liveliness by inspiring their owners to dress and feeltheir best. There are fun pieces that can work for a 20-yearold,as well as more sophisticated pieces that can work fora 32-year-old. We encourage the Lorick Lady to step out ofthe box and mix and match them.PHOTOGRAPH BY STEVE SANGAs Old Navy and H&M have increasingly swept asidethe Art Nouveau galleries in NYC’s SoHo neighborhood,the most recent outpost of the Seven New York boutiquenestled itself quietly on Mercer Street in a bid to promotean aesthetic, forward-focused vibe in the area. With thechange of locale, the concept store that over the pastseven years has been generating its own Factory-esquescene for the island’s truest fashionistas, has entered a newgrowth phase.“We’re a gallery-like machine of fashion, designed tonot only sell clothes, but inform the clientele about themost inventive collections,” Seven NYC founder and buyerJoseph Quartana says proudly. “Many of our clients spendtwo hours looking at each piece in the store before tryingsomething on!”Quartana originally opened shop with college comradesSteve Sang and John Demas in 2000, in the then-emergingLower East Side. In December of last year, he shiftedground to SoHo and introduced the ‘hood to the broodof progressive designers Seven routinely stocks, whichinclude Bernard Wilhelm, Raf Simons, Jeremy Scott, Preenand ThreeAsFour.MEnchicseven 2.oAN NYC CONCEPT BOUTIQUE, MOVING FORWARD BY IAN DREW”We’re a home for edgy designers who create newworlds with their collections,” Quartana notes. “Of course,there are certain commercial restrictions, but, more importantly,[every line we carry] has to be visionary, consistentlystrong for at least two or three seasons.” Quartana (whocarries an economics degree from Rutgers and is unafraidto admit that his passion for pushing the fashion buttonwas triggered by early, life-changing experiences withpsychedelic drugs) quickly established Seven as an arbiterof style through a strict selection process.He routinely monitors 20 to 25 designers at a time—fresh new talents whose names are first whispered in hisear by respected editors and other tastemakers in his innercircle. His insistence on spotlighting the crème of avantgardedesigner talent has inevitably brought on chargesthat Seven retails laughably unwearable clothes. Quartanadefends his curatorial approach: “A lot of our designers justaren’t for everyone. Pieces are misunderstood. But I haveto create a story with each designer’s world, and it has toextend across each of my designers in the shop, as well.What we have is the best of what’s out there and everypiece is essential to the whole picture.”Equally essential to the trademark Seven experience isthe way the retail space itself is organized—like a minimuseumin which every piece is carefully displayed formaximum effect. The Mercer Street store design is basedon a circular, clockwise pattern, in which the clothing isallowed to breathe. Faceless mannequins sport signaturelooks favored by Seven’s elite clientele, which range fromWest Village pier queens to celebrity trendsetters likeChloë Sevigny, the Olsen twins and Björk. “We wantedto [deliver] a pure experience and eliminate any distraction.The store is an homage to our creative policy,”Quartana says.While it seems natural that a trend architect like hewould have a five-year plan firmly locked in place, Quartanainsists that he hasn’t mapped out any further expansion forhis concept boutique. “The way we’ve grown over the lastfive years has been organic, so I have no idea what’s next.Except that I will continue to make Seven the most interestingfashion retailer on the planet.”Visit the SoHo outpost of Seven New York at 110 MercerStreet, or check it out online at sevennewyork.com.18 november-december meanchic

MEnchicrad hatterMEET MILLINER EXTRAORDINAIRE ALBERTUS SWANEPOEL BY ERIN SKRYPEKWe live in a time when, for the most part, only Britishroyalty, quirky movie stars, Japanese women terrified ofthe sun and any wise person who rides a ski lift dare don aproper hat. Gone are the days of men who never went fartherthan the front door without flipping on a felt fedora;the quaint age of ladies who wouldn’t dream of departingfor daily errands without a pillbox hat pinned precisely totheir heads. But hats are beginning to make a comeback,especially on the runways, and the man leading the chargeis Albertus Swanepoel.Recently singled out by Style.com as “fashion’s new favoritemilliner” for his work at the Proenza Schouler Spring/Summer 2008 show, Mr. Swanepoel is swiftly morphinginto the American counterpart to famed British millinerPhilip Treacy—no small feat, seeing as the United States is afar less hat-centric society than the United Kingdom.The 48-year-old hatter—a Dutch Afrikaner who movedto Manhattan two decades ago—properly graduated tothe world of American couture (if there truly is such athing) a few years back, crafting head gear for Marc Jacobs,Proenza Schouler, Paul Smith and Tuleh. He recently addedErin Fetherston, Rodarte, Thakoon and Zac Posen to hisrepertoire; not to mention an exclusive collection of hatsunder his own name, for Barneys New York.“He’s a hat genius,” piped Erin Fetherston afterher Spring/Summer 2008 show in September, whereSwanepoel created a whimsical array of headpieces thatmirrored chunks of snow-white coral or dove wings, andwhite satin turbans with a little bird peeking out of arosette of folds in the front. “He made all my millinerydreams come true!”We asked Swanepoel about his choice of métier,whom he’d like to hat and what it’s like to sit atop thefashion pile.How did you become a milliner?By chance. I always liked accessories, so when clothingdesign did not happen for me here in New York, my thenwifeand I started a glove company that developed intoa hat-making venture during the summer season, whengloves weren’t in demand.You strike me as an old-school gentleman: well-manneredand soft-spoken. Have the mores and chivalryof past hat-wearing eras infiltrated your life becauseof what you do?I had a very strict upbringing; good manners were ofutmost importance. I think wearing a hat is a ladylike, orALBERTUS SWANEPOEL PORTRAIT BY SEAN DONNOLAgentlemanly, thing to do. My father used to wear a hat almostdaily and my mom wore one to church on Sundays.You collaborate with so many designers: How doesthat work?It works in various ways. Some designers give me a sketchto interpret or realize. Sometimes I have to copy somethingexactly from a vintage hat or photo. I sort of make it realfor them; I give it a form. I have some say in proportionand color, or I make suggestions for materials and [advisethem on] technical matters. Some hats are very challengingtechnically. I hope to reach the stage where I can actuallydesign for a label like Stephen Jones does for Dior.If you could collaborate with any designer—alive ornot—who would it be?Christian Lacroix Couture would top my list. I’m a hugeadmirer! Also, Hussein Chalayan and Alexander McQueen.As for the designers who joined the choir invisible: Adrian,Elsa Schiaparelli, Cristobal Balenciaga and Monsieur Dior.And if you could collaborate with any artist, whowould it be?Cecil Beaton, Oliver Messel, Marcel Vertes, Christian Berard,Jean Cocteau… I guess I should have lived in the ’30s!What is the most fashionable style of hat to wearright now?The fedora is the new shape, I think. I’m already seeing alot of cool girls on the street wearing one.Whose head would you most like to see one of yourhats on?Queen Elizabeth. Also, José Cura—the opera singer; JoseManuel Carreño—the ballet dancer; Inès de la Fressangeand Charlotte Gainsbourg.What’s your favorite fabric to work with?Duchess satin. I love the richness and structure of thematerial. I also love straw cloth, which is difficult to find,and silk organza.If you weren’t making hats, what would you be doing?I think I’d be a game ranger in the Serengeti, wearing khakiPrada and driving a vintage Rolls! Or maybe a fashion illustrator.Or an opera singer.Have you gone mad yet?Mmmm, I don’t think so! I have my quirks. I love whatI do but my passion sometimes comes in the way ofthings.20 november-december meanchic

MEnbETHe w a s b a l d, I w a s p l a y in g, s h e h a d a c a m e r a…I c a m e, I s a w, I w a s horrifiedTh e y p u t u s u p in lovely a c c o m m o d a t io n s—v e r y “open p l a n”I c a n’t remember w h a t t h e t u n e w a s , b u t I o b v io u s l y l ik e d it a l o tAb o u t a s u s e f u l a s a n a s h t r a y o n a m o t o r c y c l eTh is w a s t h e set list f o r t h e n i gh tMEnchichello, good buyABAETÉ’S LOW-COST HIGH STYLE BY ERIN SKRYPEKGo d Bless a l b u m s re c o rd e d in m o n o !It’s a rare occurrence these days when a woman canactually go out and buy a dress she sees highlighted ina fashion mag. The prices of designer duds are sky-high.We can blame inflation, the power of the euro (or theweakness of the dollar, depending on how you look at it)or the designers themselves for supposedly using the mostluxurious materials French and Italian mills have to offer.Yet somehow, we remain convinced that swell-looking,well-made clothes that don’t skimp on quality or break thebank are not a pipe dream.That’s exactly why we love Laura Poretzky and her line,Abaeté. Poretzky’s is truly a designer collection—it evengoes down the runway at Bryant Park each season—butowning one of her simple, modern, feminine dresses willonly knock you back $400 at most. And that’s a bargain,considering how much style Miss Poretzky—soon to beMrs., by the way—pours into each piece she designs.The attractive, strawberry-blond designer was born inFrance to a Russian father and a very chic Brazilian mother,who has inspired many an Abaeté look; actually, “Abaeté”is her mother’s family name. After graduating from RhodeIsland School of Design, Poretzky began her career designingswimwear in 2003. Her bathing suits weren’t the typicallyteeny bikinis you see on the beaches of Rio, thoughshe had become well acquainted with “barely there”swimwear while spending time in her mother’s native land.Rather, they were elaborate, Old Hollywood–style bathinggarments, the kind you’d imagine Grace Kelly slipping into.The kind you could add a few inches to the bottom of andend up with an Alaïa-like mini-dress.But when Poretzky transitioned from swimwear to anentire range of ready-to-wear, she did not end up sendingdown the runway stretchy, Hervé Léger/Alaïa/ChristopherKane–style looks. While she continues to show her bathingcostumes on the runway, the rest of her current collection isentirely Lycra-free. Like the designer herself, the clothes areelegant, but understatedly sexy. Poretzky always seems tobe aware of female curves, but never puts them on blatantdisplay. Even her bathing suits are more covered up thanyou’d expect. And her dresses are prim enough for theoffice, but whimsical and elegant enough to wear out todinner, with a quick change of shoes.Speaking of shoes—Poretzky also designs a shoe andhandbag collection for Payless, so you can basically geta pair of Abaeté shoes for about $20. And who needs todrop $900 on a pair of Italian stilettos when you can get anequally well-designed version for less than you’d pay for adecent lipstick?jamie t the visual brooklyn diaries photographs BY paul g. maziarJamie T’s had a big year. The 21-year-old Wimbledon native saw his debut record, Panic Prevention, recognized with aMercury Prize nomination for the Album of the Year. His incantatory, poetic rhymes set to acoustic guitar hooks and reggaebeats place him in an exciting continuum of British singer-storytellers who have been able to fold hip-hop conventions intotheir own, original brand of songwriting. Think The Streets aka Mike Skinner. Think Plan B. In fact, don’t think at all and letMr. T (né James Treays) do the thinking for you. Revel instead, like we are, in the broken charm of his observant ditties like“Sheila” (“Her lingo went from the cockney to the gringo/Any time she sing a song”)—a hit last year in Britain—and hismouthy couplets about the plight of working-class stiffs, drunks and bored young men with no real prospects or directionin life and only the next pub brawl to look forward to. (For the latter, he has one bit of cheeky advice: “Take your problemsto United Nations/Tell old Kofi about the situation.”)This fall, the U.S. release of Panic, coupled with vigorous stateside touring, is bound to bring yet more recognition for thisapple-cheeked bard of the streets. Visiting Brooklyn over the summer, Jamie checked out the hallowed turf of his heroes,the Beastie Boys, gigged about and recorded some impressions exclusively for <strong>Mean</strong> in a mini visual diary.22 november-december meanchic

obert wyatta master soundsmith on the divine comedy of imponderable thingsBY john payne + photograph by alfreda benge“I have my loyalties, you know. I believe in Charles Mingus.I don’t apologize to him or thank him or pray to himfor rain. I’m glad he’s here, that’s all.”Thus spake Robert Wyatt, one of the great creakyrock/jazz/pop/avant whatsits of the English music scenewho, like Mingus, is a famously non-genre-bound composer/multi-instrumentalistwho smears the tedious oldlines between “serious” music and pop effluvia. Wyatt’ssweetly crooned and decidedly English voice (‘e drops ‘isaitches) comes in service of idiosyncratically drawn musicalshapes, which can be arcane free-jazz- or bop-splashedor kinda ’60s psychedelic or straight-ahead pop or NuevaCanción-inspired, though often as not, it’s all and none ofthe above and far the better off for it.’Tis no small wonder, then, that the speckled likes of JoannaNewsom, Elvis Costello and Alexis Taylor of Hot Chiphave all chorused loudly at one time or another in praise ofWyatt’s uniquely shaped soundscapes disguised as pop music.They might know of him from his drumming/singing inthe late-’60s early-’70s avant-jazz-rock band Soft Machine,or his whimsically modernist jazzy-pop combo MatchingMole (from the French machine molle, or “soft machine”),or perhaps recall his numerous plaintive-choirboy appearanceson recordings by the cream of the ’70s English artrockcrowd such as Henry Cow and Hatfield and the North;most assuredly they’ll know Wyatt’s wrenchingly beautiful1974 solo album Rock Bottom, written shortly followinghis spine-shattering fall from a second-story window; althoughit could be that their lives were changed by Wyatt’ssubsequent English chart-topper of the ’70s—the definitivecover of Neil Diamond’s “I’m a Believer.”While the above “career trajectory” of such an artistdoesn’t make a lot of typical showbiz sense, there’s nodoubt that it’s uncommonly inspiring, as is just one listen toWyatt’s new Comicopera (Domino), whose appeal involvesthe very ambition of its undertaking in the ADS Year ofOur Lord 2007.Well… an opera? Hold up: Wyatt is anything but grandiose;in fact, he’s the very definition of the wrongly self-effacingartist. His “opera,” he says, is merely a way of tellingstories of everyday life, and about the people he meets. Theancient Athenians had it right, he thinks.“Greek theater was divided into comic and tragic,”he points out, “and comic didn’t necessarily mean funny;comedy is much more about human foibles and failuresand mischief and madness.”Mischief, slight madness and a touch of melancholyare the key tones of Comicopera, in which Wyatt employsseveral different characters (mostly sung by himself) to tellthe story, and ultimately foregoes his native tongue entirelyto sing in Spanish and Italian. “Sometimes,” he says, “youlisten to a singer-songwriter and you think, ‘This is just oneperson crying aloud against the wilderness’ or whatever.But some of the people on Comicopera are people tellingme off; another part is somebody saying how wonderful itis dropping bombs on a sunny day.”Accompanied by a fortuitously assembled group of playersand singers such as ex-Roxy Music members Brian Enoand Phil Manzanera, and the wonderfully straight-tonedBrazilian chanteuse Monica Vasconcelos, Wyatt’s dramaset to music is an openly drawn frame that accommodatestouching tales of love gone stale (and how to push thereset button), misplaced faith, the uses of nostalgia, whitelies, and the dark truth about war’s often hazy moral lessons—plussome choice bits about his hunger for a cultureother than his own moribund English one.Unlike the Greeks, Wyatt does not concern himselfdirectly with tragedy as such, or religion and destiny andthe big sort of imponderable eternal things. What he doesaddress is “various sorts of strategies that humans employwhen life itself needs some kind of dealing with in thehead. I have no knowledge of anybody who’s got a generalanswer, but I do know of people who had interesting andrewarding lives exploring different ways of having a mentallife co-existent with their daily life.”Wyatt’s own scheme is to draw on things and peoplethat have inspired him in the past, such as surrealism,avant-garde jazz, mysticism and revolution. Both the distinctivelydifferent symmetry and dryly humored gravitasof Wyatt’s new music was inspired in various measure bythe assorted likes of Duke Ellington, Ornette Coleman,Federico García Lorca and Che Guevara, all of whom, likeWyatt, felt powerful incentive for change.“These are all people who were totally exasperated withthe trajectory of history,” he says. “And they thought, well,one thing we’ll do is just completely change art, break therules, get back to the subconscious; just start again, helpthe workers—never mind shaving. It’s [a view] I’ve alwaysempathized with. I haven’t really seen much of it that getsyou out of the morass, but somebody lives in hope.”The humble Wyatt doesn’t seem to realize how, forsome of us, hearing such specially sculpted music does infact lift the listener way, way out and above the mire.“In the end,” he says, “I’m not a politician or philosopher;I’m simply a person who makes records. I try and useall the skill I’ve acquired to make some kind of listenableseries of things happen to the ears. For now, that’s thechallenge, and even if nobody understands a word.”24 august-september meanbeat

A small tweak makesa big difference.The tC has been tweaked for 2008._A redesigned front-end grille_Projector headlamps and new taillights_New exterior colors and updated interior fabric_Standard seat-mounted side airbags and side curtain airbags *_Under-cargo subwoofer_iPod connectivity*The tC comes equipped with driver's side front airbag, passenger's side front airbag, seat-mounted side airbags,side curtain airbags, and driver's side knee airbag. iPod ® is a registered trademark of Apple Computers, Inc.

the misshapesdedicated followers of fashionBY adam sherrett“I totally forgot about this interview,” says the softvoice on the phone. “I hope you don’t mind that I’m inmy pajamas.”Under normal circumstances, such a comment wouldmean little to an interviewer. However, when it leaks fromthe lips of one of the three asymmetrically coiffed Misshapesat 6 p.m. on a Saturday, it seems to carry a bit moreweight: I suddenly feel overdressed in jeans and a T-shirt.I sit down with the nonchalantly disheveled GeordonNicol in his Manhattan apartment’s pseudo-courtyard totalk about his DJ trio’s fame and their new collection offashion portraits, Misshapes (powerHouse/MTV Press).His getup—all-black combo gym shorts and tank top andbed-head perfect hair—begs for questioning, and I, like atrue inquisitor, demand that he define his own sense ofstyle. “I really don’t know how anyone can define a style,”he retorts. “I mean, I’m wearing gym shorts, a wife-beater,and slip-on Vans that my friends drew on! When I go out,I’m not consciously thinking about what I’m gonna wear;it’s a natural thing.”After all, personal style and a Warholian grasp of theZeitgeist—more so than beat-matching and scratchingskills—have powered the meteoric rise of Nicol and histwo Misshapes cohorts, Leigh Lezark and Greg Krelenstein.Over the course of only a few years, the twentysomethingthreesome have become New York nightlife ringleaders,evolving from underage partiers to underage party hoststo in-demand DJs/fashion icons. Nicol surveys their accomplishmentswith a sense of fatalism: “We’ve beenreally lucky. We’ve had a lot of opportunities presentedto us—putting together a book, soundtrack-ing fashionshows, traveling all over the world. In that sense, our liveshave changed a lot.” What about the street recognitionfactor? “I guess there’s more of that too. What’s funny iswhen the middle-age Vogue readers who have nothing todo with the party recognize your face,” he adds. “It’s notbad—just kind of funny.” All the same, Vogue editor SallySinger contributed a foreword to the Misshapes book, agesture sure to further enhance the trio’s reputation asstyle catalysts.Anyone in the know is by now familiar not just with theMisshapes’ parties and the hosts’ faces, but also with thesignature “wall photos” at their weekly events, which havenow been collected into a photo album. Like a typical party,the book’s stark cover reveals nothing. Oh, and don’t evenbother looking for a glossary. “It’s kind of like a Where’sWaldo,” Nicol says. “A glossary would be almost impossible—andtacky.” However, he reassures, “The notablesare in here, but you have to go through the book to findthem.” Inside the tome, images of celebrated hipster icons(Madonna, Bloc Party, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Chloë Sevigny,etc.) are methodically blended with photographs of partyregulars like Sophia Lamar and Jackson Pollis, who’ve beenMisshapes devotees since the beginning. Former Dior Hommedesigner Hedi Slimane, Visionaire magazine co-founderCecilia Dean and photographer Nan Goldin also figure inthe lineup. “I started with close to 300,000 photos and gotit down to just under 3,000 for the book,” Nicol says. “Ifthis book does well, I’m sure there’ll be a second.”All sequels aside, lack of confidence has never beenan issue with these three trendsetters. And the attendeesto their Saturday night extravaganzas at East Village clubDon Hill’s don’t seem too timid either. Like it or not, they’reunafraid and completely indifferent to the opinions ofthe uninitiated. “I think that people on the outside lookin and say, ‘Look at these assholes trying so hard,’” Nicolsays. “But in reality, the people that come to the party arejust coming to have fun. What matters most, he adds, isthe all-inclusive acceptance of individuals from a myriadbackgrounds, looking to have fun in their own way. “I thinkthe word ‘Misshapes’ means something eclectic,” Nicolconcludes. “It’s all these individual styles coming together[in one place]. That doesn’t necessarily mean the Misshapesparty or New York City—it could be anywhere.”2008 SCION tCMEnbET© 2007 Scion is a marque of Toyota Motor Sales, USA, Inc.

MEnbETThere are some things Eleanor and Matt Friedberger, thesister-brother duo Fiery Furnaces, agree on: Bob Dylan. TheSopranos. And who played Ouija board with Grandma. Butthen there are some things they don’t exactly see eye to eyeon—like whether Eleanor had any game time with Grampson the old backgammon board, or where the concept of“Restorative Beer,” a track from their new album WidowCity, came from.The two talk at the same time and answer questions inone breath. They seem like close, old friends but displaytypical brother/sister animosity where needed. “We gotcloser when I started playing music,” Eleanor admits. “I’msure even during the biggest fight we ever had,” the elderMatt explains, “no one said, ‘I’m sorry.’ That’s a privilege offighting with a sibling: You don’t really have to make up.”The one thing they seem to agree on most during ourinterview is poking fun at my poignant Chicaaaaago accent.The Friedbergers themselves are Chicago natives. And althoughMatt has shed his long “A” Chicago pronunciationssince his move to New York, Eleanor slips from time to time,and blurts forth words like Indiaaana. The transplants don’tmiss their home. “We go there so much,” Matt acknowledges.“You should always leave,” he advises. “If you don’t leavefiery furnacessibling secretsBY charlene rogulewski + portrait by amy giuntawhere you are from, then you don’t get to go home.”The siblings recorded most of their latest record, WidowCity, in and around the Chicagoland area. Their studio sessionswere done across Lake Michigan in Benton Harbor,Michigan, and the mixing was accomplished at Chicago’sSoma Studios.It’s not exactly simple following the elder Friedberger’sthought processes, although Matt begs to differ, and pointsout it’s a simple task. “I had some fake method involvingimaginary Ouijas for myself,” he says of the lyrical inspirationsfor Widow City. In his “imaginary Ouija board” sessions,he would ask the game board what lyrics his sistermight want to sing and wait for the board to answer. ImaginaryOuija sessions weren’t the only convoluted methodsthe duo used. Knick-knacks and mouse-masticated magazinesalso heavily influenced Widow City’s lyrics.For the most part, the Fiery Furnaces’ music comes froma made-up world. “We just think of it as the real world,”Matt explains. “But we just make up stories about it.”“I was planning my dream house,” Eleanor tries to explainbefore Matt chimes in and pokes fun: “Eleanor wasplaaaning her dreaaam house with aaads aaaand picturesfrom maaagazines...” Yes, she’d cut ideas for her dreamhouse out of vintage magazines in their beloved GrandmaOlga Sarantos’ basement in Forest Park, Illinois, just westof the Chicago skyline. This is the same grandmother whoappeared on their 2005 album Rehearsing My Choir, andnarrated stories about her life over the Friedbergers’ punchyand charmingly manic music. These magazines and sundryother curios contributed to the sibs’ Widow City.Widow City is the duo’s first for Chicago label Thrill Jockey.In 2002, the Friedbergers got their break when RoughTrade signed them on for their debut, Gallowsbird’s Bark.“I had moved to New York and I was trying to play music,”Eleanor remembers. “And then Matt moved shortlyafter, so it just made sense for him to help me.”The band released two more albums, Blueberry Boatand Rehearsing My Choir on Rough Trade. In 2006 theyput out Rehearsing My Choir’s companion album, BitterTea, on Fat Possum Records before signing on with ThrillJockey for Widow City.The record takes its name from the “city of disappointeddreams that we all live in,” Matt says.Not necessarily true for the duo. They have grown frombeing a small stage act at Brooklyn’s now defunct NorthSixvenue to having their name up on the marquee at RadioCity Music Hall. But it’s their playful take on their dismalsurroundings that has inspired them throughout theirhumble beginnings.“There’s this mini school, where I used to live, out byKennedy Airport.” Matt says. “It’s the most depressing thingyou can imagine. I use to work in schools when I was young.I was an aide.”“I used to work in Elmhurst, Queens at an insurancecompany. It was not fun,” Eleanor says.These days, the younger Friedberger spends most of herdays walking through Socrates Sculpture Park in Greenpoint.“The Greenpoint skyline is going to look so different10 years from now,” she imagines.“In 15 years we’re not going to even believe that itlooked the way it does now,” Matt chimes in.“My neighborhood has already changed a lot,” Eleanorsays with a sigh.“…But that’s nothing like what it’s going to be in 15years,” Matt proposes.Widow City is cohesive and sometimes chugs alongpowered by a Tropicalia rhythm. “It was mostly drumsand early ’70s keyboards,” Matt explains. While WidowCity is more accessible than their previous albums, it stillevidences the duo’s trademark dissonance and unfocusedmethods—Eleanor singing over a different melody thanwhat her brother punches out. “We were going to havethe album be this narrative… that we decided not to do,”Eleanor divulges. “It told a story from beginning to end.So we only kept a couple of the songs.”“Matt’s the music man,” she says. While he contributesmost of the instrumentation for their albums, Eleanor is incharge of all singing duties, although she’ll step up to write atwo-chord song here and there. “Eleanor wrote ‘Tropical Ice-Land,’” Matt admits, “and that’s our most famous song.”Their back-and-forth is almost as static and quick as theirmusic’s focus. Take “Ex-Guru,” the band’s catchiest tune offthe new album. “That song’s based on two people,” Mattexplains, “but we can’t say who they are.”“They’re both top secret,” Eleanor interrupts.“…And both are very real,” Matt adds.“We know someone who has a guru,” Eleanor continues.“They go to conventions where the guru is…”“…It will often be a Doubletree Hotel by an airport,”Matt says, but the actual specifics are a secret that remainsbetween the Friedbergers.a window intotheir widow cityfiery furnaces documenttheir habitual haunts &favorite points of inspirationin new yorkphotographs by eleanor& matt friedberger(1st c o l u m n, t o p to b o t t o m)Eleanor: 91-31 Queens Blvd. in Elmhurst, Queens—where I worked in an insurance claims office for 2years; Eleanor: My favorite park—Socrates SculpturePark, Long Island City; Eleanor: Five cop cars inLong Island City; Matt: Stables in Howard Beach(2n d c o l u m n, t o p to b o t t o m)Eleanor: View from my bedroom window; Eleanor:Dancing at Stuyvesant Cove on a Sunday afternoon;Eleanor: Giglio Feast at Our Lady of Mt.Carmel, Williamsburg, Brooklyn; Matt: P.S. 213 MiniSchool, Brooklyn(3rd c o l u m n, t o p to b o t t o m)Eleanor: The Greenpoint waterfront (my neighborhoodfor the past 7 1/2 years), as seen fromStuyvesant Cove; Eleanor: Queens Blvd., Queens;Matt: Stables in Howard Beach; Matt: “The spirit oflearning” on Linden Blvd., Brooklyn(4th c o l u m n, t o p to b o t t o m)Eleanor: More feasting at Our Lady of Mt. Carmel inWilliamsburg; Matt: Kings Co. Hospital, Brooklyn26 november-december meanbeat

mathieu schreyerl.a. soul manBY jenifer rosero + photograph by brent bolthouseANDREW BIRDsolidarity troubadourBY A.D. amorosi + photograph by cameron wittigMeeting DJ Mathieu Schreyer, aka Mr. French—a manwho still spins vinyl and carts his own 45’s to his weeklyDJ residencies at L.A. boîte Hyde—is refreshing. Just likeCoca-Cola tastes better out of a bottle, listening to him spintracks from his massive collection of reggae, dub, salsa,samba, Afro-beat, soul, funk and broken beat records,complete with the sound of scratches and little imperfections,feels more wholesome and pleasurable than groovingto a laptop-engineered set.The French-born Schreyer, who settled in the U.S. in1995, got his own show on influential Los Angeles radiostation KCRW last winter. He’s now able to reach more earsand share his gospel—a passion for old-school turntablismand what he calls “soul music from all over the world.”What led you to the music?I had been into music from an early age. The first thing Iever bought myself was a tape, when I was 5 or 6. Havinglots of siblings, I used to take their records and play themall the time for my friends at after-school parties. When Iwas a teenager, my sister used to go out with this guy whohad a huge record collection, and he turned me on to jazz,soul—the kind of stuff I’m spinning now. It kind of openedmy eyes and educated me about all sorts of different music.Then I started buying records, and the next thing you know,a restaurant [in my neighborhood] asked me to DJ, so itkind of all came naturally.How did you get your own show on KCRW?I befriended [KCRW’s] DJ Garth Trinidad. We startedhanging out and DJing together at Zanzibar in 2002. LastChristmas he came to me and was like, “There may be anopening at the station. Would you like to do a show?” andI was like, “Fuck yeah!” So he took me there, and I hookedup with Anne Litt, who is also a DJ at the station, and I didone demo. The music was fine and they liked my programming,but I was a bit shy—and that was a problem. So Irecorded the demo a second time, and three weeks afterthat, they [asked me], “Can you start next Friday?” It allhappened really fast.Your show happens on Friday nights, between midnightand 3 a.m., and it’s called On the Corner. Whydid you pick this moniker?I really wanted something that was reminiscent of thestreets, because all the music I play is so street-oriented—the music of people in the streets just having a good time,whether it’s in Cuba, Senegal or Japan. And I was playingthis On the Corner record that Miles Davis did in 1972.I went to [KCRW general manager Ruth Seymour] withthe name and Ruth, who’s from New York, said, “On theCorner is very New York. I love it.”If you had to categorize the kind of music you play,what would you call it?Soul music, but not as in only Marvin Gaye–type soul music.Soul music from all over the world. When I play Latinmusic, it’s their rendition of soul music. When I play SergeGainsbourg—that’s our soul music from France. If I play ATribe Called Quest, that’s some soulful hip-hop. What I’mlooking for in music is a feel. And that feel comes from anartist who is expressing themselves from a purely non-businessstandpoint. Put it this way: The music I like is not madeto be sold. It’s people’s expression recorded on tape, andeventually someone likes it and they try to sell it. But theway it was made was completely from the soul. Whetherit’s soulful electronica, or soulful hip-hop—it’s music thattouches you. You listen to this music, man, and you don’tneed to go to church!Many DJs use vinyl emulation software, and a Seratosetup is de rigueur these days, it seems. You’re still goingat it old-school—you use only vinyl. Why?I’ve been buying records for the past 17 years. I want to usethem. I don’t want my records to sit on a shelf, nor do I wantto sell them. It’s my passion. I lived for that all my life, and Idon’t want to let go of it. Serato makes much more sensetechnologically; it’s more practical and all. But I’m taking mytime to get into that. I’ll get an iPhone before I get a Serato.That way I feel more like an artist as opposed to a robot oranother DJ with a laptop.What other kinds of things do you do, and what doyou ultimately want to do?I definitely want to help expose more of the music I liketo a wider crowd; movies would be a great medium [toaccomplish that]. So I want to get into music supervisionand soundtracks. I have a couple projects comingup with Michel Gondry, who is a friend of mine. I’vebeen doing production since ’99—I just make beatsand work with different artists. I’ve worked with Tricky,N’Dea Davenport of the Brand New Heavies; old-schoolMotown artists like Syreeta— Stevie Wonder’s wife.I worked with Leon Ware, and a bunch of hip-hopartists like Chali 2na from Jurassic 5 and Tre Hardsonof the Pharcyde. Who knows, maybe I’ll get the opportunityto start a label and get some of these greatartists better exposure. I’ll just keep going and try totouch as many people as possible.No one wants to be alone—it’s doubtful that evenGreta Garbo truly did. But if you’re going to do it, do itwith the panache that Andrew Bird sings of in “Imitosis,”one of the debonair tracks from his recent record ArmchairApocrypha.At 34, Bird—an instrumentalist known for his splendidprowess on violin and glockenspiel— has penned one ofthe most eloquent songs about the joys of loneliness. “Thesong was based on a revelation I had when I was 19,” Birdreveals. “I understood that no matter how much we surroundourselves with other people, we’re still trapped inour own bodies.”Bird’s work is sprinkled with eye-openers about wars,animal innards and blissful paranoia, in addition to wittydiscourses on his distrust of the psychological elite, educationalpathways and pop science. He has been recordingwith the likes of Squirrel Nut Zippers and his own brittleBowl of Fire since 1996, though he only relatively recentlybegan recording on his own, issuing Weather Systems(2003) and The Mysterious Production of Eggs (2005). Yetit is only his third effort, Armchair Apocrypha, that finallyhas the heart and the aggressive heft of a record worthy ofhis name below the title. To say nothing of some damnablygrouchy guitars.“A band is just symbolic really,” Bird says. “Eventhough I held onto the name Bowl of Fire longer than Iwanted, I managed to tour all around solo for the longesttime.” It was just him, his fiddles, his guitars and variouslooping pedals. “There’s something serene about it,”he adds. These days, when he collaborates with othermusicians, he chooses them based not only on whatthey can do for him, but also on what he can do with,and for, them. They have his back; he has theirs. “Atthe end of the night, these are the guys you’re leavingwith,” Bird comments about the symbiotic band-budconnections that fuel his work. Take Martin Dosh—anequally solitary producer, sequencer and lo-fi electronicmusic-maker. Bird collaborated with Dosh on some ofArmchair Apocrypha’s spookiest moments (tracks like“Simple X”), and toted him on tour. “I never, ever questionhis taste and am always totally amused by what he’splaying,” Bird observes. “Plus, I don’t like stock footagein music, ideas by rote. I always trust that he’s not evergoing to be unengaging.”Bird’s evolution from pint-size student of the Suzukimethod (a nurturing approach to music-learningfor children) to hyperactive, jittery sound-maker withthe swingin’ Squirrel Nut Zippers reaches full fruitionMEnbETwith Apocrypha. Even though his previous solo recordsdisplayed a mad eclecticism (German lieder, gypsy music,jazz, soul and folk) in tiny doses, his latest work internalizesall of his influences and regurgitates them in a moreorganic and focused fashion. “Before, I couldn’t let all themusic I was enamored with seep through. A lot of thoseother records were more deliberate. If I felt myself [including]inflections from other eras or other genres of music,I would take them away.”Now Bird takes nothing away, and opts instead to playwith people who bring their whole record collection tothe party—as evidenced by songs like “Spare-Ohs” and“Yawn at the Apocalypse,” bright, resonant testimoniesto his skill at stripping down the essence of musical genresand rejiggering it into organic new compounds. “I like tothink of that playing process as sounding asexual,” Birdnotes. Yet he can’t help but bring a plump lushness to allthat he beholds.While some blame the aggression of its guitars and thewordy whimsy of its lyrics for the fact that Apocrypha isturning out to be the most popular album of Bird’s career,he himself refuses to puzzle out the mystery.“There are no answers,” he says. “There’s just lookingat things from different angles.”28 november-december meanbeat

the role less traveledEwan McGregor Suits Up for as Woody AllenBY JOHN PAYNE + PHOTOGRAPHS BY RANKIN

One of life’s most horrific pleasuresin recent times has been replaying inone’s head that legendary scene in1996’s Trainspotting where the franticyoung junkie played by Ewan Mc-Gregor evacuates his precious dopesuppository into one particularly gruesomepublic toilet, then dives into themuck after it, whereupon wondrous,liberating fresh vistas are revealed tohim and us.McGregor made it seem fun, even,diving headfirst into a grimy bog. Thefact is, his charming on-camera easeand loose-limbed athleticism are theproduct of a lot of serious dramatictraining that has served him well in arather bizarrely varied film and stagecareer which has seen him assayingsuch far-flung roles as the Jedi knightObi-Wan Kenobi in the Star Wars prequelsThe Phantom Menace and Attackof the Clones, a lunatic rock star inVelvet Goldmine, a song-and-danceman in Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge!and London productions of Othello andGuys and Dolls.All of which is the merest tip ofthe polar cap for the prodigiouslyprolific McGregor, who at age 36 hasracked up 30-plus stage, televisionand film performances, the latest ofwhich is his starring role alongsideColin Farrell in Woody Allen’s just-outCassandra’s Dream.And while McGregor enjoys discussingthe art of acting, the veneratedmotivations and inner hells of the charactershe plays are, he feels, best leftunprobed. By himself, at least.“I’m not particularly conscious ofthe methods I use to come up withcharacters,” he tells me by phone fromhis home in North London. “SomehowI think that it’s instinctual. I like to talkabout the films, though, except thethings I find the most interesting are thethings the tabloid press is, of course,least interested in. They want to knowwhat happened last night with JudeLaw.” He laughs. “It’s not as if I’m goingto tell them.”It’s that plucky fuck-it ‘tude combinedwith a down-to-earth good humorof McGregor’s that tends to bothlure in and captivate audiences. Hecombines the earthy rogue appeal ofthe young Albert Finney in Tom Joneswith something slightly more hightoned,but only just. Growing up ina small farming town in Scotland, hewas addicted at a young age to films,especially black-and-white ones, andfelt the acting bug especially when hisuncle, the actor Denis Lawson (LocalHero), came up from London in hissheepskin waistcoat and no shoes.“He didn’t look like anyone else‘round about me,” McGregor says.“We would go and see him in theshows and stuff. Back in the ’70s therewas something on British televisioncalled Armchair Theater: half-hourdramas that were like one-act plays,and he was often in those. And itwas like an event—everyone wouldget ‘round the telly and sit down andwatch Uncle Denis. And so I was like,‘Fuck, I wanna do that.’”Thus McGregor left school at 16 andgot a job in a repertory theater a fewmiles from his house, working there fora few months as one of the stage crew.“We’d put up scenery and take downscenery, and then occasionally they’dgive me little walk-up parts. I startedlearning my job then.”As for Uncle Denis, “He’s still absolutelymy inspiration,” McGregor says.“It’s embarrassing how much I act likehim in some things I do. I phone himup all the time from the set and say,‘Den, I’ve really done you today in thisscene.’ And I was thrilled the first timehe phoned me up and he went, ‘Ewan,I’ve just done you in a scene.’ The piècede résistance will be when we endup sharing the screen in something. Idon’t know when that will happen, butsomething fantastic will come alongthat we can act in together.”Following his six-month repertoryexperience, McGregor did a one-yearacting course at Scotland’s Perth RepertoryTheatre and eventually movedto London, where he attended theGuildhall School of Music and Drama.“It kind of got me into the industry because,you know, you do the shows atthe end of your final year that everyonecomes to see, and through that I endedup working.”Still, he thinks it’s difficult to teachsomebody how to act. “You can’t, really,”he says. “But what you can do isput people in an environment wherethey can feel safe to try things out, andyou can put them through differentclasses and ideas about acting techniques—youhad people who taughtyour method acting classes, and otherpeople who use emotional memoryrecall and that sort of thing. But it’s difficultto say what you learn. I suppose Icall on it all the time. I don’t know that Ido, but I suppose that I must do.”McGregor’s role as the strung-outRenton in Danny Boyle’s Trainspottinghad come a year after his smash filmdebut in Boyle’s Shallow Grave, in whichhe played a callow young Londoner whoplots the dismemberment of his deaddrug-dealer flatmate. One might wonderwhat motivated him to choose theseoften borderline-crazy or at least, well,intense types of roles that he undertakeswith such gleeful abandon.“A good story,” he says—end ofstory. “I sit down with the script andif I get that feeling like you get whenyou’re reading a good book and youdon’t want it to end, and if by the endof the script you’re seeing yourselfwhen you’re imagining the story, thenit’s something I’ll want to do.”As for the refreshingly weird varietyin his choice of roles—ultimately hisown decisions, though his managersmust tear their hair out from time totime—he says, “I think it’s excitingthat way. I’m quite easily pleased,and as I’m reading something, I canoftentimes see the good film in a scriptwhere maybe others don’t—and I’moften not right.”In McGregor’s view, a film’s artisticsuccess has next to nothing to do withwhether it’s helmed by the best directorin the world or is played by the best actors,has the best composer and editor“we had absolute freedom to improvise,but we didn’t feel the need to changeanything. there’s a reason why woodyallen is considered a great writerand i’m not.”34 november-december mr.mean

58 august-september mr.meanand DP, etc., etc. “If your story is notvery interesting,” he says, “then yourfilm is not very interesting.”Whereas, he thinks, if a movie depictsa ripping good yarn, that canmake up for other things, even ifthey’re simply shot, as is the case withWoody Allen’s films.“They’re very pure in the way heshoots,” says McGregor. “But becausehis stories are very good, I think that’sone of the great lessons about workingwith him. The performance is generallyenough without 15 takes. I mean, he’scompletely unique in how little coveragehe does. You just shoot a master, awide shot, and that’s it, really. And it’sjust absolutely lovely, because for theactors the performance is everything,and nothing gets stale or old becauseyou’re going through it so quickly.”Cassandra’s Dream is Allen’s latestmurder-melodrama concerning twomiddle-class London brothers, played byMcGregor and Farrell, who take part in ahigh-risk and ultimately soul-destroyingscheme to finance their wildly differingaspirations toward a better life. The filmboasts a veritable feast of great English,Scottish and Irish actors savoring thechance to bring out the best in Allen’sdevilishly plotted and immaculatelycrafted script—or to toss it out the windowand improvise if need be.“We had absolute freedom to dothat,” McGregor says, admiringly.“He’d start almost every scene and say,‘You know, look, these are just wordsthat I wrote; just say whatever you like,and just as long as you hit the beat,put it in your own words, don’t worryabout it.’ But, I’m sure Colin feels thesame way, we didn’t really feel the needto change anything because it was sobeautifully written. There’s a reasonwhy Woody Allen is considered a greatwriter and I’m not, so why should Ichange it?”The affably forthright McGregorrecently took on the role of Iago in aLondon stage production of Othello,by some extension a bit similar to thebrother he plays in Cassandra: a backstabbingfigure who must ensure audienceempathy by somehow comingoff if not entirely sympathetic, then atminimum perversely likable. McGregorhandles that tricky job with such finetuning in Cassandra that one mightquestion how much it has to do withsuperb acting technique versus theequally formidable task of just beingyourself in front of a camera.“Well, Woody was always quitekeen that the story was about ‘twonice boys,’ says McGregor. “He’d say,‘This is a film about two nice boys,and just because of their flaws andtheir faults and the situation, they endup doing a terrible thing.’ But he wasalways quite adamant that they weregood lads; just working guys whowere struggling along.”McGregor felt sympathy for his characterIan, the ruthless would-be hotelierbrother to Farrell’s sweetly loutishmechanic.

“I suppose I could understand Ian,”he says, “because bad characters… Idon’t know how bad they think they arethemselves, you know? It’s easy to playa kind of two-toned villain, but I don’tthink people are really like that. Peoplethat do terrible things still think they’reprobably all right.” To him, it’s not terriblyexciting to play someone who’s justpurely evil. “I mean, there’s no shortageof British bad guys in American movies,you know what I mean?”In Cassandra, the bond between Mc-Gregor’s grasping yuppie fuck andFarrell’s heavy-drinking/gambling-addictschlub is played with touchingcredibility. The two actors come off sobelievably brotherly, in fact—so completelyfamiliar with each other’s tics,vanities and fatal flaws—that it’s hardto believe that McGregor and Farrellonly became acquainted when bothwere cast in the film.“I’d never met Colin,” McGregorsays. “The process of getting the filmtogether was very quick. Woody wasgoing to shoot a film in Paris and thenat the last minute changed his mind.He pulled this script off the shelf andI went and flew over to New York tomeet him, and Colin went to New Yorkto meet him. Literally, I met Woody forabout 30 to 40 seconds. I’d fallen inlove with the script, and then I foundout Colin was playing the other brotherand I thought, ‘This is just great.’ So Igave him a call and he came over andmet my family—we sat down and hadsomething to eat and just got on immediatelywell.”McGregor is effusive in his praisefor the skills of the feral Farrell. “I justthink he’s brilliant. There are a few actorsaround that you hope your pathsmight cross with one day, and he’s certainlysomebody I’d hoped for.” And hereports that it came as a relief that thepair got on so well. “I don’t think youcan create chemistry or manufacturea brotherly relationship onscreen. Youknow you’re both playing brothers, soyou sort of instinctively relate to eachother in a certain fashion.”According to McGregor, WoodyAllen’s style of quick-shooting hisfilms—usually setting up just one shotand grabbing the scene in two or threetakes—is, for actors like Farrell andhimself, the only way to go. “It’s veryoften that you’re discovering things forthe first time as you’re saying them andthe cameras are rolling, and there’s nosense of repetition because you’re nottrying to re-create anything; it’s brandnew.And if it’s not the best take, it’sgenerally one of the most exciting.”And, he believes, there’s a stake init. “As Woody would always say, ‘Youcan’t fuck this up. You just have to stayin character and keep talking.’” Although,he recalls, if an actor did muffhis lines, “You’d see Woody rubbinghis hands together, looking delighted,thinking, ‘I’m gonna put that in.’ Andhe did. He likes putting in all your flubsand stammers. Human beings flub and38 november-december mr.mean

“Woody Allen said to me, ‘Critics canlove us or they can hate us. Either way,it makes no difference.’ and he’s right.”STYLING: Alix Waterhouse,alixwaterhouse.comGROOMING: Liz Martins, nakedartists.com,using Origins productsFIRST SPREAD: T-shirt, FolkSECOND & THIRD SPREAD: T-shirt, H&M;Shirt, C.P. Company; Vest, Paul & Joe;Pants, Create Your Own; Glasses,Ray-Ban WayfarerFOURTH SPREAD: T-shirt, H&M; Shirt,Aertex; Jacket, Hardy Amies; Glasses,Ray-Ban WayfarerFIFTH SPREAD: T-shirt, H&M; Cardigan,Guess; Jacket, Marc Jacobs; Jeans, NudieON THE COVER: Shirt and jacket, Gucci;Vest, Acne Jeans; Pants, Trovata;Glasses, Ray-Ban Wayfarerstammer when they work, know whatI mean?”The image of the Infallibly GreatActor is easier to pull off on-screen, ofcourse, as McGregor found out duringa long run of stage performances inGuys and Dolls two years ago.“…There was a moment where Iforgot the words in the middle of asong one night,” he says, chortling. “Inthe middle of a song! And the orchestrakeeps going, and there’s nothingyou can do. So I was just making shitup.” He starts singing the lyrics he hadimprovised on the spot: “‘I like to lookat your face. I like it a lot…’ That wasterrifying. I felt like I’d been in a car accident.And that’s when you realize whatlive theater is all about. The danger ofit is brilliant.”Yet he requires the pure energy of doinghis stuff in front of an audience fromtime to time. Unlike performing in frontof a blue screen for one second-unit director,there’s a full house of people, andthey’re watching, and listening.“It’s exciting, because you’re maneuveringa group of people’s emotionsfrom one place to another, andit’s quite a powerful feeling.”Apparently, exciting his own imaginationis still of primary importance to ourEwan McGregor, the former party boywho’s now a devoted family man with awife and three daughters, the youngestof whom is a Mongolian adoptee. Youmight’ve seen him blow off steam in a2002 PBS documentary that found himwatching polar bears migrate in remotenorthern Canada, or watched the 2004Bravo channel series that documentedhis round-the-world motorbike trekwith pal Charley Boorman.Ultimately, the thing that strikes youabout McGregor is his restlessness,which in his case isn’t the desperate,empty, Hollywood-needy searching wehear a little bit too much about, buta healthier, more swashbuckling kindof world-conquering that can inspireeven the most jaded film fan to wantto heartily slap him on the back andcheer him on. It’s a vicarious thrill sortof thing.Like the late Klaus Kinski, Mc-Gregor just craves the work, andit doesn’t matter whether the criticsconsidered his choice of filmshigh, fine art or something trashyand cheap. True, Kinski needed themoney. For McGregor, however, actingis, simply stated, something hejust loves to do.And if it makes critics grumble andgroan on occasion—so be it. “Youcan’t please them, you know?” Mc-Gregor laughs again. “This is somethingI learned from Woody. He said tome before we went into the screeningof Cassandra’s Dream in Venice, “Theycan love us or they can hate us. Eitherway, it doesn’t matter. They’ve lovedme in the past. They’ve hated me in thepast. It doesn’t make any difference.’And he’s right.”Extraordinarily refreshing, isn’t it, towitness the excitement of an excellentactor doing it for thrills and laughs,and who couldn’t give a toss aboutthe hoary old bores of career arc orbox office.“I just don’t care!” McGregor cackles.“I’m happy if people see it and likeit, but sometimes it’s quite cool to watchthe dog that slipped through the net.“I just got this feeling cominghome in the car at the end of thenight from the film set, feeling likeI’ve done my best shot, I’ve givenmy best work, and feeling I did thebest job I could. And I felt satisfied.If you’re looking to be the most famous,you’ll never get there. I love theidea of someone waking up going,‘That’s it! I’m famous enough! I canbe happy now!”40 november-december mr.mean

uckwildEmile Hirsch’sRites of PassageBY PETER RELICPHOTOGRAPHS BY PATRICK HOELCK