Self-sufficiency or surplus: Conflicting local and national rural ...

Self-sufficiency or surplus: Conflicting local and national rural ...

Self-sufficiency or surplus: Conflicting local and national rural ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Scheidel, A., Giampietro, M., Ramos-Martín, J. (2013):”<strong>Self</strong>-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>: <strong>Conflicting</strong> <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>national</strong> <strong>rural</strong> development goals in Cambodia”, L<strong>and</strong> Use Policy, Vol. 34: 342-352,http://dx.doi.<strong>or</strong>g/10.1016/j.l<strong>and</strong>usepol.2013.04.009<strong>Self</strong>-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>: <strong>Conflicting</strong> <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>national</strong> <strong>rural</strong>development goals in CambodiaArnim Scheidel a,1 , Mario Giampietro a,b , Jesús Ramos-Martin a,ca Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals (ICTA), Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB),Bellaterra, Barcelona 08193, Spainb Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ ats (ICREA), Passeig Lluís Companys, 23, Barcelona08010, Spainc Departament d’Economia i d’Història Econòmica, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB),Bellaterra, Barcelona 08193, SpainAbstractCambodia is currently experiencing profound processes of <strong>rural</strong> change, driven by an emerging trend oflarge-scale l<strong>and</strong> deals. This article discusses potential future pathways by analyzing two contrastingvisions <strong>and</strong> realities of l<strong>and</strong> use: the aim of the governmental elites to foster <strong>surplus</strong>-producing <strong>rural</strong> areasf<strong>or</strong> overall economic growth, employment creation <strong>and</strong> ultimately poverty reduction, <strong>and</strong> the attempts ofsmallholders to maintain <strong>and</strong> create livelihoods based on largely self-sufficient <strong>rural</strong> systems. Based onthe MuSIASEM approach, the <strong>rural</strong> economy of Cambodia <strong>and</strong> different <strong>rural</strong> system types are analyzedby looking at their metabolic pattern in terms of l<strong>and</strong> use, human activity, <strong>and</strong> produced <strong>and</strong> consumedflows. The analysis shows that the pathways of self-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>surplus</strong> production are largely notcompatible in the long term. Cambodia’s <strong>rural</strong> lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce is expected to increase en<strong>or</strong>mously over thenext decades, while available l<strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong> the smallholder sect<strong>or</strong> has become scarce due to the granting ofEconomic L<strong>and</strong> Concessions (ELC). Consequently, acceleration in <strong>rural</strong>–urban migration may beexpected, accompanied by a transition from self-employed smallholders to employment-dependentlab<strong>or</strong>ers. If the ELC system achieves to turn the reserved l<strong>and</strong> into viable agribusinesses, it might enableadded value creation; however, it does not bring substantial amounts of employment opp<strong>or</strong>tunities to <strong>rural</strong>areas. On the contrary, ELC have high opp<strong>or</strong>tunity costs in terms of <strong>rural</strong> livelihoods based onsmallholder l<strong>and</strong> uses <strong>and</strong> thus drive the marginalization of Cambodian smallholders.JEL classification: Q15, Q57, R11, R14, J22Keyw<strong>or</strong>ds: Cambodia, L<strong>and</strong> grabbing, Economic l<strong>and</strong> concessions, Poverty reduction,Rural developmentIntroduction“The government talks about poverty reduction, but what they are really tryingto do is to get rid of the po<strong>or</strong>. They destroy us by taking our f<strong>or</strong>ested l<strong>and</strong>, 70%of the population has to disappear, so that 30% can live on” (Villager, affectedby an Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concession in Cambodia (Licadho, 2009)).Within the recent years, Cambodia has experienced profound processes of <strong>rural</strong> change,associated to the large granting of l<strong>and</strong> concessions f<strong>or</strong> economic purposes. While <strong>rural</strong>smallholders have been striving to achieve <strong>and</strong> maintain livelihoods based on largelyself-sufficient smallholder agriculture (cf. Leuprecht, 2004), the governmental elite isseeking the establishment of large-scale industrialized agriculture capable of providing<strong>surplus</strong> flows f<strong>or</strong> overall economic growth, employment creation <strong>and</strong> ultimately poverty1 C<strong>or</strong>responding auth<strong>or</strong>, Tel.: +34 935868102.1 / 18

eduction (RGC, 2004, 2008). This paper discusses impacts, constraints <strong>and</strong> potentialfuture consequences of these contrasting l<strong>and</strong> use paths in Cambodia.A variety of studies have discussed the recent changes in the <strong>rural</strong> sect<strong>or</strong> of SoutheastAsia (SEA) <strong>and</strong> Cambodia. Hall et al. (2011) identified <strong>and</strong> discussed four powers ofexclusion that have shaped l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> users in SEA. B<strong>or</strong>ras <strong>and</strong> Franco (2011)analyzed the political dynamics of l<strong>and</strong> grabbing in SEA with a particular focus on therole of the European Union. Furtherm<strong>or</strong>e, a number of rep<strong>or</strong>ts from development<strong>or</strong>ganizations (Leuprecht, 2004; OHCHR, 2007) <strong>and</strong> NGOs (e.g., Licadho, 2009),critically discussed the negative impacts of Cambodia’s l<strong>and</strong> management strategy onhuman rights <strong>and</strong> human development in <strong>rural</strong> areas. While these studies have addressedimp<strong>or</strong>tant aspects of the political <strong>and</strong> social dimension of <strong>rural</strong> change in Cambodia <strong>and</strong>Southeast Asia, there is further need f<strong>or</strong> a quantitative assessment of the currentprocesses of <strong>rural</strong> change in <strong>or</strong>der to discuss potential future pathways of l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong><strong>rural</strong> livelihoods in Cambodia.Within this context, this article analyzes, based on the MuSIASEM approach (Multi-Scale Integrated Analysis of Societal <strong>and</strong> Ecosystem Metabolism) applied to <strong>rural</strong>systems (Giampietro, 2003), patterns of l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> human activity of the <strong>rural</strong>economy of Cambodia <strong>and</strong> of different <strong>rural</strong> system types. The constraints, impacts <strong>and</strong>potential future consequences of the governmental Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concession (ELC)system are addressed <strong>and</strong> the incompatibility of different development visions <strong>and</strong>realities, such as expressed by a villager in the introduct<strong>or</strong>y statement, are discussed.Although the geographic focus of this paper is Cambodia, we further contribute to them<strong>or</strong>e general debates on agricultural <strong>and</strong> <strong>rural</strong> development that have recently emergedwith the global l<strong>and</strong> grab (B<strong>or</strong>ras et al., 2011; Scheidel <strong>and</strong> S<strong>or</strong>man, 2012; von Braun<strong>and</strong> Meinzen-Dick, 2009; Zoomers, 2010). Hence, we address currently debated issuesin l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> <strong>rural</strong> development studies, i.e., the potential contribution of large-scalel<strong>and</strong> deals to <strong>rural</strong> employment (Li, 2011; Vermeulen <strong>and</strong> Cotula, 2010); the perceptionthat the global South inhabits large reserves of ‘idle’ agricultural l<strong>and</strong> (B<strong>or</strong>ras <strong>and</strong>Franco, 2010, 2011; Cotula et al., 2009); the role of domestic act<strong>or</strong>s in the l<strong>and</strong> grabphenomenon (Deininger, 2011; Hall, 2011; Siciliano, 2012); <strong>and</strong> the opp<strong>or</strong>tunity costsof large-scale agribusiness in terms of poverty reduction <strong>and</strong> livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunitiesbased on smallholder l<strong>and</strong> use (De Schutter, 2011).The paper proceeds as follows: the next section provides background inf<strong>or</strong>mation onCambodia, its development policy <strong>and</strong> the ELC system. The ‘Methodologicalframew<strong>or</strong>k <strong>and</strong> data’ section introduces the methods <strong>and</strong> data, on which basis the ‘The<strong>rural</strong> economy of Cambodia: l<strong>and</strong> use, demography <strong>and</strong> human activity’ sectionanalyzes potential challenges <strong>and</strong> constraints f<strong>or</strong> ELC in terms of l<strong>and</strong> use, demography<strong>and</strong> human activity. The ‘The employment potential of Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concessions(ELC)’ section discussed <strong>rural</strong> employment issues related to ELC, <strong>and</strong> highlights theopp<strong>or</strong>tunity costs in terms of livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities from smallholder l<strong>and</strong> uses.Finally, the ‘<strong>Self</strong>-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>: conflicting <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>national</strong> <strong>rural</strong>development goals’ section illustrates the fundamental differences between selfsufficient<strong>and</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>-producing <strong>rural</strong> systems <strong>and</strong> the paper concludes in the‘Conclusion’ section on the existence of conflicting development visions <strong>and</strong> realities asdrivers of <strong>rural</strong> change.2 / 18

largest contribut<strong>or</strong> (38.3%), followed by industry with 28% (NIS, 2008b). Inconsideration of a potentially higher contribution of the <strong>rural</strong> sect<strong>or</strong> to economic growth<strong>and</strong> poverty reduction, the Rectangular Strategy f<strong>or</strong> Growth, Employment, Equity <strong>and</strong>Efficiency in Cambodia of the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) has setagriculture as a center stone of its overall development policy:“Indeed it is necessary to enhance <strong>and</strong> broaden the base f<strong>or</strong> economicgrowth by opening <strong>and</strong> utilizing the potentials in other sect<strong>or</strong>s,especially in the high-potential agricultural <strong>and</strong> agroindustrial sect<strong>or</strong>s,so that the nation will obtain larger positive windfall gains in theimprovement of the livelihoods of the <strong>rural</strong> people. The agriculturepolicy of the Royal Government is to improve agricultural productivity<strong>and</strong> diversification, thereby enabling the agriculture sect<strong>or</strong> to serve asthe dynamic driving f<strong>or</strong>ce f<strong>or</strong> economic growth <strong>and</strong> poverty reduction”(RGC, 2004: 13, emphasis added).In <strong>or</strong>der to promote such agricultural development, Cambodia was, <strong>and</strong> still is, in theneed of a proper l<strong>and</strong> administration system that inf<strong>or</strong>ms well about l<strong>and</strong> use, l<strong>and</strong> users<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> use rights (Thiel, 2010). L<strong>and</strong> use governance has experienced fundamentalchanges in Cambodia, ranging from private property rights <strong>and</strong> concession systemsduring the French protect<strong>or</strong>ate (1863–1953) <strong>and</strong> the subsequent regimes, over acomplete collectivization under the Khmer Rouge regime (1975–1979), to thereintroduction of private property <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> concessions in 1989 under the State ofCambodia (Fig. 1). After this, smallholders were encouraged to apply f<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>mal l<strong>and</strong>titles to agricultural <strong>and</strong> residential l<strong>and</strong>, but the l<strong>and</strong> administration was unable to dealwith m<strong>or</strong>e than 4 million applications lodged, resulting that less than 10% of them wereprocessed at the end of 1995 (Russel, 1997). The current l<strong>and</strong>-titling process results in250,000–300,000 new l<strong>and</strong> titles annually; however, at least 12 million parcels remainstill unregistered (Thiel, 2010). In addition to the l<strong>and</strong>-titling system f<strong>or</strong> smallholders, asystem of Social L<strong>and</strong> Concessions (SLC) was established (L<strong>and</strong> Law 2001), aimed atproviding l<strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong> l<strong>and</strong>less, l<strong>and</strong> po<strong>or</strong> people <strong>and</strong> other disadvantaged groups f<strong>or</strong>subsistence <strong>and</strong> family farming (RGC, 2003) (Table 1).However, f<strong>or</strong> the development of agriculture as engine f<strong>or</strong> economic growth, a l<strong>and</strong>concession system was needed that allowed f<strong>or</strong> the generation of large <strong>surplus</strong> flows f<strong>or</strong>the economy; both in terms of commodities produced <strong>and</strong> tax fees. Since 1989,concessional l<strong>and</strong> larger than 5 ha could be granted to private companies f<strong>or</strong> cropproduction “to supp<strong>or</strong>t the <strong>national</strong> economy” (Russel, 1997). Despite of thefundamental lack of inf<strong>or</strong>mation regarding l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> registration, agriculturalconcessions were generously awarded, leading to increasing l<strong>and</strong> conflicts <strong>and</strong> ash<strong>or</strong>tage of arable l<strong>and</strong> at the end of the 1990s (Leuprecht, 2004). The 1992 L<strong>and</strong> Lawfailed to regulate l<strong>and</strong> concession <strong>and</strong> although the new constitution of the Kingdom ofCambodia was promulgated in 1993, it took almost ten years to establish the new 2001L<strong>and</strong> Law that would regulate concessional l<strong>and</strong>. Finally, in 2005, the RGC (2005)4 / 18

issued the current sub-decree on Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concession (ELC) with the finalobjective to determine the procedures <strong>and</strong> criteria of revising concessions pri<strong>or</strong> to the2001 L<strong>and</strong> Law <strong>and</strong> granting new ELC. Acc<strong>or</strong>ding to the sub-decree, among the mainpurposes of ELC is the promotion of agro-industries, large projects investments, thecreation of employment in <strong>rural</strong> areas <strong>and</strong> fiscal revenues 2 . And acc<strong>or</strong>ding to “Invest inCambodia”, a governmentally supp<strong>or</strong>ted invest<strong>or</strong>s magazine: “F<strong>or</strong> invest<strong>or</strong>s looking togrow <strong>and</strong> process crops, Cambodia is an ideal location with plenty of l<strong>and</strong> available f<strong>or</strong>agricultural concessions” 3 . The following sections of this article will provide <strong>and</strong>assessment of the constraints, impacts <strong>and</strong> potential future consequences of this l<strong>and</strong> usepolicy.Methodological framew<strong>or</strong>k <strong>and</strong> dataIn <strong>or</strong>der to assess constraints <strong>and</strong> impacts of the ELC system, it is necessary to get anunderst<strong>and</strong>ing of the current <strong>rural</strong> economy of Cambodia (the ‘The <strong>rural</strong> economy ofCambodia: l<strong>and</strong> use, demography <strong>and</strong> human activity’ section) as well as to analyze theperf<strong>or</strong>mance of the proposed concessions systems, i.e., industrialized large-scaleplantations, in comparison to common current <strong>rural</strong> systems, i.e., smallholderagriculture (‘The employment potential of Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concessions (ELC) <strong>and</strong><strong>Self</strong>-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>: conflicting <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>national</strong> <strong>rural</strong> development goals’sections). To do so, this paper uses c<strong>or</strong>e concepts from the MuSIASEM approach(Multi-Scale Integrated Analysis of Societal <strong>and</strong> Ecosystem Metabolism) applied t<strong>or</strong>ural systems analysis (Giampietro, 2003; Gomiero <strong>and</strong> Giampietro, 2001; Serrano <strong>and</strong>Giampietro, 2009; Siciliano, 2012). In particular, we draw on the concepts of ‘societalmetabolism’, ‘<strong>rural</strong> system types’ <strong>and</strong> ‘impredicative loop analysis’.The societal metabolism approach looks at socio-ecological systems by analyzing theprocesses of material <strong>and</strong> energy transf<strong>or</strong>mation required to sustain a given identity <strong>and</strong>to perf<strong>or</strong>m structural <strong>and</strong> functional activities (Giampietro et al., 2009, 2011). In <strong>or</strong>derto f<strong>or</strong>malize the socio-metabolic process in terms of what the system is <strong>and</strong> what thesystem does, we employ the concepts of ‘funds’ <strong>and</strong> ‘flows’, developed by Ge<strong>or</strong>gescu-Roegen (1971). ‘Funds’ refer to those elements of the system that are maintained <strong>and</strong>unchanged during a production process (hence, the identity of the system), whileproviding crucial services f<strong>or</strong> the process to happen. ‘Flows’, refer to those elementsthat enter but do not exit the production process (i.e., input-flows), <strong>or</strong> exit, but do notenter the production process in the same state (i.e., output-flows). Flows hence aretransf<strong>or</strong>med by the funds during the socio-metabolic process. Following theMuSIASEM approach, we consider l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> human activity among the most crucialfunds of <strong>rural</strong> systems <strong>and</strong> look at flows of commodity production <strong>and</strong> consumption,<strong>and</strong> their monetary value. Thus, we look at patterns of l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> cover t<strong>or</strong>epresent the biophysical identity of <strong>rural</strong> systems <strong>and</strong> analyze patterns of humanactivity (i.e., time allocated to sleeping, eating, on-farm <strong>and</strong> off-farm w<strong>or</strong>k, education<strong>and</strong> leisure) to represent the socio-cultural identity of <strong>rural</strong> systems. Sustainability <strong>and</strong>lasting <strong>rural</strong> poverty alleviation ultimately is about maintaining the integrity of thefunds <strong>and</strong> their transf<strong>or</strong>mative services, in <strong>or</strong>der to sustain a desired socio-ecologicalsystem (Scheidel, 2013). F<strong>or</strong> l<strong>and</strong> in production, this means maintaining the productive2 Concession rental fees range from 0 to 10$/ha/yr, depending on the quality <strong>and</strong> location of concessionl<strong>and</strong> (MAFF, 2011).3 http://www.investincambodia.com/agriculture.htm (accessed on 04.04.2011). These w<strong>or</strong>ds were alsoused by other governmental bodies to promote ELC; e.g., http://www.cambodianembassy.<strong>or</strong>g.uk/(accessed on 01.03.2012).5 / 18

properties <strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong> l<strong>and</strong> not in production, it means maintaining critical ecosystemfunctions that serve as ecological overhead. F<strong>or</strong> human activity, it means to guaranteesurvival (i.e., maintaining the physiological overhead in terms of sleeping, eating,personal care, care of elderly <strong>and</strong> children) as well as maintaining a valued socioculturalidentity (i.e., the social overhead: patterns of leisure, education, socialinstitutions) (Giampietro, 2003). F<strong>or</strong> the assessment of the current situation of <strong>rural</strong>Cambodia in ‘The <strong>rural</strong> economy of Cambodia: l<strong>and</strong> use, demography <strong>and</strong> humanactivity’ section, we thus account f<strong>or</strong> both productive <strong>and</strong> non-productive activities ofthe population, as well as f<strong>or</strong> productive <strong>and</strong> non-productive l<strong>and</strong> uses.In <strong>or</strong>der to be able to compare the perf<strong>or</strong>mance of a <strong>rural</strong> system operated underconcessions to those operated by smallholders (‘The employment potential of EconomicL<strong>and</strong> Concessions (ELC) <strong>and</strong> <strong>Self</strong>-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>: conflicting <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>national</strong><strong>rural</strong> development goals’ sections), the complexity <strong>and</strong> diversity of <strong>rural</strong> life needs to besimplified in acc<strong>or</strong>dance with the purpose of analysis. We use the concept of <strong>rural</strong>system types in <strong>or</strong>der to deal with <strong>rural</strong> complexity (Giampietro, 2003). With ‘type’, werefer to a general set of expected relations of funds <strong>and</strong> flows of <strong>rural</strong> systems, whichprovides relevant inf<strong>or</strong>mation to underst<strong>and</strong> the particular ‘instances’ (i.e., realizations)of such types in real life. A simple example illustrates the type concept well: thetransp<strong>or</strong>t types ‘bicycle’ <strong>and</strong> ‘car’ have millions of different realizations each, but therealizations share enough commonalities that allow discussing general aspects, i.e.,what you can do with cars, <strong>and</strong> what you can do with bicycles. Based on the purpose ofthis paper, we define a simple typology that consists of two <strong>rural</strong> systems types: (a) theaverage Cambodian smallholder village, which represents a general pattern of thecurrent <strong>rural</strong> Cambodia <strong>and</strong> (b) industrialized, large-scale agribusiness as pursued to bedeveloped with the ELC system. The perf<strong>or</strong>mance of both systems in terms ofproduction <strong>and</strong> reproduction patterns will be compared using an impredicative loopanalysis (ILA) (see Giampietro, 2003 f<strong>or</strong> a detailed description). Briefly, an ILA is amethodological tool to provide a representation of the linkages between selected fund<strong>and</strong> flow elements. We use an ILA in ‘<strong>Self</strong>-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>: conflicting <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>national</strong> <strong>rural</strong> development goals’ section to analyze the relations between the l<strong>and</strong> inproduction, the flows produced, the required lab<strong>or</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the total amount of humanactivity (lab<strong>or</strong> plus dependent part) that is associated to <strong>and</strong> sustained by each <strong>rural</strong>system type. The smallholder system type will be used to discuss the generalperf<strong>or</strong>mance of the current <strong>rural</strong> reality, while the ELC system type is used to discussthe urban <strong>and</strong> governmental vision of <strong>rural</strong> systems.All data employed in the paper come from various secondary sources. Statistical dataare generally taken from the Cambodian National Institute of Statistics (NIS) <strong>and</strong>include the Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey 2009 (NIS, 2010), the GeneralPopulation Census (NIS, 2008a), the Statistical Yearbook of Cambodia (NIS, 2008b)<strong>and</strong> the Time Use Survey (NIS, 2007). Currently, no <strong>national</strong> agricultural census isavailable that inf<strong>or</strong>ms coherently about l<strong>and</strong> holdings, l<strong>and</strong> uses <strong>and</strong> production data;hence they need to be integrated from various sources. While we take ELC data fromthe Ministry of Agriculture, F<strong>or</strong>estry <strong>and</strong> Fisheries (MAFF, 2011), we use theCambodian Agrarian Structure Study (ACI, 2005) as source f<strong>or</strong> average industrialproduction data <strong>and</strong> average smallholder production data. The average smallholdervillage type is calculated based on average statistical data on demography, humanactivity, l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> production f<strong>or</strong> <strong>rural</strong> villages in Cambodia. Finally, although thedata come from secondary sources, the presented research is inspired by a three months6 / 18

ha. In fact, other calculations indicate a total of 2 million ha of ELC l<strong>and</strong> (Vrieze <strong>and</strong>Naren, 2012), which is substantially higher. Based on the MAFF data, the maj<strong>or</strong>ity of 5the projects are dedicated to f<strong>or</strong>estry (46%); followed by rubber (19%), oil palm (9%)<strong>and</strong> other crops such as sugarcane, jathropha <strong>and</strong> grains. Companies with Cambodianhead offices dominate the sect<strong>or</strong>, representing 61% of all concession l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> 41% ofall companies. This confirms that domestic act<strong>or</strong>s play an imp<strong>or</strong>tant role in the recentl<strong>and</strong> grab phenomenon (Deininger, 2011; Hall, 2011). Chinese companies are thesecond most imp<strong>or</strong>tant act<strong>or</strong>s, accounting f<strong>or</strong> 22% of total l<strong>and</strong> size. The remaining17% of concession l<strong>and</strong> is divided between Vietnamese, American, Thai <strong>and</strong> otherAsian companies (own calculations, based on MAFF, 2011).On an aggregated level (Fig. 3), we can see that the current amount of concession l<strong>and</strong>could only be granted due to the small l<strong>and</strong> holdings of the <strong>rural</strong> population. L<strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong>further ELC could currently only come from unprotected f<strong>or</strong>ests <strong>and</strong> shrub l<strong>and</strong>,protected areas, <strong>or</strong> from (unregistered) smallholder l<strong>and</strong>. However, total f<strong>or</strong>est coverwas already in 2008 with 10.5 million ha (NIS, 2008b) m<strong>or</strong>e than 2% below theCambodian target of maintaining 60% (FA, 2010) <strong>and</strong> both ELC <strong>and</strong> miningconcessions have already penetrated large parts of protected areas as well as unprotectedf<strong>or</strong>ests (ODC, 2012). In addition to the quantity of available l<strong>and</strong>, also certain qualities,such as productivity, suitability f<strong>or</strong> large-scale agriculture <strong>and</strong> access to markets whichusually characterize lowl<strong>and</strong>s, matter <strong>and</strong> may drive invest<strong>or</strong>s’ operations into areasalready cultivated by smallholders (Cotula et al., 2009). In fact, the granting of ELC haswidely affected Cambodian smallholders because of substantial problems regarding theallocation of concession l<strong>and</strong> (Licadho, 2009). Due to the unfinished l<strong>and</strong>-titlingprocess, inf<strong>or</strong>mation on smallholder l<strong>and</strong> is largely missing, resulting in problems ofweak l<strong>and</strong> governance (Thiel, 2010). It was estimated that since 2003, no less than400,000 people have been affected by l<strong>and</strong> disputes <strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ced evictions in only 12 outof 23 provinces (Vrieze <strong>and</strong> Naren, 2012).Regarding the current l<strong>and</strong> grab debate, the perception of vast available reserves of‘idle’ <strong>or</strong> ‘underutilized’ l<strong>and</strong> in the global South gained prominence amonggovernments trying to attract invest<strong>or</strong>s as well as among invest<strong>or</strong>s seeking f<strong>or</strong>opp<strong>or</strong>tunities <strong>and</strong> partly has its roots in technical l<strong>and</strong> mapping based on satelliteimagery (B<strong>or</strong>ras <strong>and</strong> Franco, 2010, 2011; Cotula et al., 2009). However, it is not clear towhich extend such ‘idle’ l<strong>and</strong> accounts f<strong>or</strong> the above mentioned qualities; to whichdegree it has been undervalued because production is not marketed (von Braun <strong>and</strong>Meinzen-Dick, 2009); if fallow l<strong>and</strong> is included (Cotula et al., 2009); <strong>and</strong> to whichdegree l<strong>and</strong> use fragmentation due to peasant settlements would interfere with largescaleconcessions. As seen above, the large granting of ELC in Cambodia was onlypossible due to small l<strong>and</strong> holdings of the <strong>rural</strong> population; through increasing l<strong>and</strong>conflicts due an overlap of concessions <strong>and</strong> smallholder l<strong>and</strong>; <strong>and</strong> through thepenetration of concessions into (protected) ecosystems. All this supp<strong>or</strong>ts that theperception of “plenty of l<strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong> agricultural concessions” needs to be reconsidered bythe Cambodian government as well as within the l<strong>and</strong> grab debate.Demography <strong>and</strong> human activity in CambodiaThe long-term consequences of the rapidly declining l<strong>and</strong> availability f<strong>or</strong> thesmallholder sect<strong>or</strong> can be well understood by looking at demographics <strong>and</strong> humanactivity in Cambodia. Fig. 4 shows the demographic structure <strong>and</strong> patterns of humanactivity f<strong>or</strong> the Cambodian population. While the population pyramid on the left of Fig.9 / 18

4 shows the population decomposed in economically active <strong>and</strong> inactive persons, thepyramid on the right represents hours of human activity in terms of monetary incomegenerating w<strong>or</strong>k, other productive w<strong>or</strong>k <strong>and</strong> non-productive w<strong>or</strong>k, calculated on thebasis of NIS data (NIS, 2007, 2008a). Income generating activities were calculated bysumming up w<strong>or</strong>k as employed, own business w<strong>or</strong>k, <strong>and</strong> the share of agricultural w<strong>or</strong>kinvested in crops sold on the market. This share was calculated based on the prop<strong>or</strong>tionof agricultural output f<strong>or</strong> household consumption (65%) <strong>and</strong> agricultural output f<strong>or</strong>selling (35%) (Mund <strong>and</strong> Ngo, 2005). Other productive activities include agriculturew<strong>or</strong>k f<strong>or</strong> household consumption (tending rice, tending other crops, tending animals,hunting, fishing), household w<strong>or</strong>k (fetching water, collecting firewood, construction,weaving, sewing, textile care, h<strong>and</strong>icraft (not textile)) <strong>and</strong> housew<strong>or</strong>k (buying, cooking,washing, cleaning, care of children <strong>and</strong> elderly). Non-productive activities include allother activities, in particular education, sleeping, eating <strong>and</strong> drinking, personal care,travels <strong>and</strong> leisure time.What becomes visible from both population pyramids is that Cambodia has anextremely young population. This relates back to the devastating rule of the KhmerRouge regime during the 1970s, in which an estimated number of 2.2–2.8 millionpeople lost their life (Heuveline, 1998). While the associated socio-demographicimpacts are far-reaching (De Walque, 2006), particularly the coh<strong>or</strong>ts aged above 30years – that is b<strong>or</strong>n bef<strong>or</strong>e the genocide – are vastly diminished. However, the coh<strong>or</strong>tsbelow 30 years are rapidly growing, implying that an extremely high number of youngpeople enter each year the lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce. Acc<strong>or</strong>ding to NIS (2010), during 2004–2009around 1.3 million persons entered the lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce, of which 1 million were located in<strong>rural</strong> areas. This c<strong>or</strong>responds to an overall increase in the lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce of 20% on the<strong>national</strong> level, <strong>and</strong> 22% in <strong>rural</strong> areas. Although such a rapid growing lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce hasled to a low dependency ratio of merely 55 dependents per 100 w<strong>or</strong>kers (W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank,2010a) <strong>and</strong> a large share (60%) of economically active population (Fig. 4, left pyramid),it represents a severe challenge f<strong>or</strong> Cambodia to provide sufficient livelihoodsopp<strong>or</strong>tunities.The official unemployment rate of merely 0.7%, with 1.8% in Phnom Penh, 2.2% inother urban areas <strong>and</strong> 0.35% in <strong>rural</strong> areas (NIS, 2010) would suggest that Cambodia isdoing well in terms of employed people (defined as all persons that w<strong>or</strong>ked at least one10 / 18

hour during the survey-reference-period of seven days, including unpaid familyw<strong>or</strong>kers, NIS, 2010). However, a deeper analysis is required to reveal employmentquality (i.e., underemployment) <strong>and</strong> employment source (i.e., self-employed subsistencew<strong>or</strong>k versus employment from other sect<strong>or</strong>s). Regarding underemployment, manyw<strong>or</strong>kers, especially from <strong>rural</strong> areas, are seeking additional employments in spite oflong w<strong>or</strong>king hours, reflecting the low <strong>and</strong> seasonal earnings from agriculture (M<strong>or</strong>ris,2007). Regarding the employment source, an analysis of human activity, as proposed bythe MuSIASEM approach, helps to get a m<strong>or</strong>e detailed underst<strong>and</strong>ing about the sourcesof livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities in Cambodia. While the pyramid on the left of Fig. 4 showsa graphical representation of human activity in terms of monetary income generating,other productive <strong>and</strong> non-productive activities, Fig. 5 provides an aggregatedapproximation to human activity in the economy of Cambodia.Cambodia’s Total Human Activity (THA) is composed of a total time budget of 117.3billion hrs (population × 24 h × 365days), of which a generous share of 57% isdedicated as physiological overhead in terms of sleeping, eating <strong>and</strong> personal care.From the remaining potentially active time, around 21% of THA is dedicated toproductive activities, which are further split into subsistence activities (11.3% of THA),employed w<strong>or</strong>k (4.7% of THA), own business w<strong>or</strong>k (3.3%) <strong>and</strong> farm w<strong>or</strong>k f<strong>or</strong> themarket (2.1% of THA) (Fig. 5). A l<strong>and</strong>-time-budget-analysis from neighb<strong>or</strong>ing LaoPDR (Grünbühel <strong>and</strong> Sch<strong>and</strong>l, 2005) shows a similar pattern, however with a largershare of subsistence activities (25% of THA). Such a pattern of human activity can beunderstood as a pattern of a largely agrarian, non-industrialized economy, in which alarge share of productive activity is dedicated to the agricultural sect<strong>or</strong>, in particular tosubsistence activities. On an aggregated <strong>national</strong> level, such as presented in Fig. 5,subsistence activities together with farm w<strong>or</strong>k f<strong>or</strong> the market account f<strong>or</strong> 63% of allproductive activities (in terms of hours of w<strong>or</strong>k). This implies that livelihood activitiesoutside the agricultural sect<strong>or</strong>, including urban areas such as Phnom Penh, account onlyf<strong>or</strong> 37% of total livelihood activities in Cambodia. If we account only f<strong>or</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas,subsistence activities together with farm w<strong>or</strong>k f<strong>or</strong> the market, make up 68% of alllivelihood activities (calculations based on NIS, 2007, 2008a).11 / 18

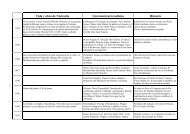

In summary, what we can see is that two thirds of the livelihood activities come fromsubsistence activities <strong>and</strong> ‘self-employed’ farm w<strong>or</strong>k f<strong>or</strong> the market. These livelihoodactivities are however based on very small l<strong>and</strong> holdings (see the ‘L<strong>and</strong> use inCambodia’ section) that generally do not allow f<strong>or</strong> large incomes <strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong> sharing with thenext generation. Hence, in <strong>or</strong>der to provide livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities f<strong>or</strong> the growing<strong>rural</strong> population, people that enter the lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce will need either l<strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong> subsistence,<strong>or</strong> jobs outside the ‘self-employed’ smallholder sect<strong>or</strong>. Yet, while the <strong>rural</strong> lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce isgrowing rapidly, l<strong>and</strong> availability has declined drastically due to ELCs. This is puttingen<strong>or</strong>mous pressure on the subsistence economy <strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong>cing young Cambodians to seeklivelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities outside the smallholder sect<strong>or</strong>. Thus, it can be expected thatwithin the next decades, Cambodia’s <strong>rural</strong> sect<strong>or</strong> will experience a fundamental changefrom an economy based on a ‘self-employed’ peasantry, toward an economy based onemployment-dependent lab<strong>or</strong>ers, suggesting acceleration in <strong>rural</strong>–urban migration. Sucha transition happened in many industrialized countries; however, there is a crucialdifference in the underlying driving f<strong>or</strong>ces. In many industrialized countries of theglobal N<strong>or</strong>th, l<strong>and</strong> was left without farmers due to the availability of other livelihoodopp<strong>or</strong>tunities in other sect<strong>or</strong>s. In Cambodia, farmers are left without l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> thus aref<strong>or</strong>ced to seek jobs in other sect<strong>or</strong>s.The employment potential of Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concessions (ELC)We turn now to discuss if the ELC system can provide the promised <strong>and</strong> neededemployment in <strong>rural</strong> areas. Acc<strong>or</strong>ding to article 3 of the ELC sub-decree, among themain purposes f<strong>or</strong> which ELC can be granted is: “To increase employment in <strong>rural</strong>areas within a framew<strong>or</strong>k of intensification <strong>and</strong> diversification of livelihoodopp<strong>or</strong>tunities <strong>and</strong> within a framew<strong>or</strong>k of natural resource management based onappropriate ecological system” (sic, RGC, 2005).The maj<strong>or</strong>ity of the ELC projects have not yet entered in a productive state <strong>and</strong> onlysome started with preparative activities such as l<strong>and</strong> clearing, while even less started toactually plant crops (MAFF, 2011). Thus, rather than to assess the actual employmentprovided, it makes m<strong>or</strong>e sense to provide a discussion on the employment potential ofthe ELC system f<strong>or</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas as well as to point out potential problems that will needto be addressed by Cambodian policy makers. It is imp<strong>or</strong>tant to note that along the lifecycleof the obtained products from both smallholder <strong>and</strong> ELC systems also further jobsare associated in urban areas, such as through the processing, trade <strong>and</strong> retail sect<strong>or</strong>.Since the ELC policy focuses on employment in <strong>rural</strong> areas, we limit our quantitativeassessment to the job opp<strong>or</strong>tunities in <strong>rural</strong> areas that are directly related to the proposedagribusinesses.To do so, we use general estimates on jobs/ha f<strong>or</strong> different industrial crops from therecent W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank (2010b) rep<strong>or</strong>t ‘Rising global interest in farml<strong>and</strong>’ in <strong>or</strong>der to comeup with a rough assessment of the employment potential of ELC (Table 2). Table 2indicates that although f<strong>or</strong>estry accounts f<strong>or</strong> most ELC projects in terms of area, it hasquite a low job potential. ELC projects f<strong>or</strong> rubber plantations are the second largestgroup in terms of areal expansion <strong>and</strong>, being lab<strong>or</strong>-intensive, have the highest jobpotential of 420 jobs/1000 ha This is consistent with data from private rubberplantations in Kampong Chan province, that suggest 400/jobs/ha during the most lab<strong>or</strong>intensiveproduction phase (year 6–29 of production; calculations based on ACI (2005),considering 300 w<strong>or</strong>kdays/year as one ‘job’). The total potential jobs estimated f<strong>or</strong> all12 / 18

egistered ELC projects amount to around 235,000 f<strong>or</strong> 1.1 million ha of concessionl<strong>and</strong>.While around 235,000 new jobs in <strong>rural</strong> areas sound promising, the picture changesrapidly if this number is put into context. First of all, this number is in fact lower thanthe amount of people (400,000) that have been rep<strong>or</strong>ted to be negatively affected byl<strong>and</strong> conflicts <strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ced evictions due to the granting of ELCs (Vrieze <strong>and</strong> Naren,2012). Secondly, in <strong>rural</strong> Cambodia yearly 220,000 persons enter the lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce(average of 2004–2009, NIS, 2010). Based on the optimistic assumption that all ELCprojects would materialize soon <strong>and</strong> would further be managed during the 70 years ofcontract time, they would have the potential to provide enough long-term jobs (50 yearsof w<strong>or</strong>k, from age 15 to 65) f<strong>or</strong> the lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce coh<strong>or</strong>t of one year. However, the personsthat enter the lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce during the following 49 years would not have any benefits interms of direct employment in ELC agribusinesses; but rather will encounter thecountryside with little l<strong>and</strong> available f<strong>or</strong> their own smallholder enterprise.Hence, the ELC system bears the severe risk of triggering <strong>rural</strong>–urban migrationmotivated by a vast number of job-seekers from <strong>rural</strong> areas. Whether the indirectlycreated jobs in urban areas such as in the retail <strong>and</strong> trade sect<strong>or</strong> can abs<strong>or</strong>b the rapidlygrowing <strong>rural</strong> lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce, remains questionable; however, it becomes clear that thepotential of ELCs f<strong>or</strong> direct employment creation in <strong>rural</strong> areas, as pursued by the 2005ELC sub-decree, is limited. M<strong>or</strong>eover, this pathway of <strong>rural</strong> change, based on a visionof <strong>surplus</strong> providing <strong>rural</strong> systems fostered by the urban elites, has large opp<strong>or</strong>tunitycosts in terms of alternative l<strong>and</strong> uses (cf. De Schutter, 2011) f<strong>or</strong> <strong>rural</strong> poverty reduction<strong>and</strong> self-<strong>sufficiency</strong>. On the basis of 2 ha/household (a value which is above theCambodian average of 1.7 ha (ACI, 2005) <strong>and</strong> which represents twice as much l<strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong>about half of all Cambodian households (NIS, 2010)), the opp<strong>or</strong>tunity costs in terms oflivelihoods based on smallholder farming amount to 575,000 households, c<strong>or</strong>respondingto no less than 2.7 million Cambodians.<strong>Self</strong>-<strong>sufficiency</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>surplus</strong>: conflicting <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>national</strong> <strong>rural</strong> development goalsWhat could be seen so far is that the ELC system, in terms of livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities,does currently not serve as ‘dynamic driving f<strong>or</strong>ce of poverty reduction’ but rather bearsthe risk to act as maj<strong>or</strong> driver of <strong>rural</strong> change, manifesting itself in a shift from a selfemployedsmallholder sect<strong>or</strong> toward employment-dependent lab<strong>or</strong>ers. Weak l<strong>and</strong>governance, l<strong>and</strong> speculation, c<strong>or</strong>ruption <strong>and</strong> other fact<strong>or</strong>s certainly play an imp<strong>or</strong>tantrole regarding the issue of why large-scale l<strong>and</strong> deals do not necessarily benefit ‘thepo<strong>or</strong>’ (cf. Leuprecht, 2004). However, we aim to add another argument to the debate:there is a fundamental conflict between the urban elite’s vision of <strong>rural</strong> development<strong>and</strong> poverty reduction based on industrialized l<strong>and</strong> use, <strong>and</strong> the visions <strong>and</strong> realities of<strong>rural</strong> communities themselves, who see their livelihoods fundamentally dependent onaccess to l<strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong> smallholder agriculture (Ballard et al., 2007).13 / 18

Fig. 6 shows an impredicative loop analysis (ILA) of two <strong>rural</strong> systems: the averagesmallholder system of agriculture <strong>and</strong> livestock production (i.e., the average Cambodianvillage) versus a model of private rubber plantation with 30 years rotation duringproduction phase (year 6–29). We use the average smallholder system to represent a<strong>rural</strong> system type that largely reflects the current <strong>rural</strong> reality in Cambodia <strong>and</strong> take theprivate rubber plantation as an example of the urban elite’s vision of agricultural <strong>and</strong><strong>rural</strong> development within the ELC scheme. The ILA illustrates the following relationsf<strong>or</strong> the two <strong>rural</strong> system types (see Fig. 5: explanation): (a) the cash value of the goodsproduced f<strong>or</strong> a fixed amount of l<strong>and</strong> in production (1000 ha); (b) the amount of lab<strong>or</strong>hours required f<strong>or</strong> the cultivation of the l<strong>and</strong>; (c) the total human activity associatedwith the w<strong>or</strong>kers (lab<strong>or</strong> hours plus dependent part such as family); <strong>and</strong> (d) the value ofgoods consumed within the production system. Again, the compared two systems are‘types’ based on average values. Hence, realizations of such types differ in practice,acc<strong>or</strong>ding to the particular socio-ecological context. Nevertheless, the differencesbetween the compared systems are large enough to discuss some general trends ofcontrasting l<strong>and</strong> uses regarding value added (as an imp<strong>or</strong>tant feature f<strong>or</strong> the urbanelite’s) <strong>and</strong> <strong>rural</strong> livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities (as an imp<strong>or</strong>tant feature f<strong>or</strong> the <strong>rural</strong>population).What can be seen clearly from Fig. 6 is that the two systems have different identities<strong>and</strong> functions regarding their socio-metabolic patterns of production <strong>and</strong> reproduction.Looking at the smallholder system (full gray lines in Fig. 6), we can see that the mainfunction consists of its own reproduction. Most of the flows, produced at a limited rate,are fed back to maintain the funds of the system, i.e., patterns of l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> humanactivity. Although often operated at low yields, smallholder agriculture has the potentialto maintain l<strong>and</strong> productivity <strong>and</strong> biodiverse agro-ecosystems in the long-term (Altieriet al., 2011). As these systems operate largely outside the market economy (e.g., lab<strong>or</strong>14 / 18

exchange, production f<strong>or</strong> household consumption), total income is generallyunderestimated in official statistics (NIS, 2010), fostering the perception of ‘po<strong>or</strong>’ <strong>rural</strong>areas, when using income as proxy f<strong>or</strong> poverty evaluation (Scheidel, 2013). However,this <strong>rural</strong> system type can provide livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities f<strong>or</strong> a comparatively largepopulation (see Fig. 6: THA), thus resulting in a high carrying capacity in terms ofpersons/ hectare. Regarding the function of such a <strong>rural</strong> system from a governmentalperspective, little <strong>surplus</strong> is left f<strong>or</strong> trade <strong>and</strong> the remaining Cambodian society in urbanareas. However, although the <strong>surplus</strong> flows are limited, they consist mostly of food (i.e.,rice), thus bearing benefits f<strong>or</strong> the Cambodian society in terms of food security. Thelarge-scale private rubber plantation system, as a relevant <strong>and</strong> job-intensive example ofthe ELC l<strong>and</strong> use scheme, clearly has a different function, <strong>or</strong>iented to economic <strong>surplus</strong>production (Fig. 6, dashed lines). The funds that produce the flows are largely modified<strong>and</strong> decreased; industrial l<strong>and</strong> use, such as rubber plantations, has generally severeenvironmental impacts in the long-term (Ziegler et al., 2009) <strong>and</strong> the identity of theassociated social system changes to employment-dependent lab<strong>or</strong>ers. A smaller fractionof lab<strong>or</strong> is required that sustains with the generated incomes a disprop<strong>or</strong>tionally smalleramount of total human activity. Hence, the carrying capacity of such <strong>rural</strong> systems isreduced in <strong>or</strong>der to produce <strong>surplus</strong> flows that, rather than self-consumed, are passed onto other sect<strong>or</strong>s.Currently, most ELC projects have not yet materialized (MAFF, 2011) <strong>and</strong> the questionremains open whether the potential future benefits <strong>and</strong> tax revenues that may beobtained will be re-invested in Cambodia <strong>and</strong> particularly in <strong>rural</strong> areas. Justified by thegovernmental discourse of poverty reduction based on overall economic growth, ELCshowever have currently led to the exclusion of other potential l<strong>and</strong> users <strong>and</strong> thus tolarge opp<strong>or</strong>tunity costs in terms of livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities f<strong>or</strong> smallholders. Thus, tounderst<strong>and</strong> current processes of <strong>rural</strong> change in Cambodia, the existence offundamentally conflicting <strong>local</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>national</strong> realities <strong>and</strong> visions of l<strong>and</strong> use, <strong>rural</strong>development <strong>and</strong> poverty reduction need to be considered. Such different visions of<strong>rural</strong> development might have less conflict potential under conditions of lowdemographic pressure, which however do not apply to Cambodia, an even less in thefuture in which productive l<strong>and</strong> resources may become scarce globally (Scheidel <strong>and</strong>S<strong>or</strong>man, 2012). Under the conditions of l<strong>and</strong> scarcity, such conflicting visions of <strong>rural</strong>development are not compatible in the long-term, driving the <strong>local</strong> population into asituation in which “their l<strong>and</strong> is needed but their lab<strong>or</strong> not” (Li, 2011: 286).The<strong>or</strong>etically, this can be understood as a drastic trade-off between different visions,scales <strong>and</strong> dimensions of <strong>rural</strong> development. In development practice however, it mayunf<strong>or</strong>tunately imply – as stated by the villager (introduction) – “to get rid of the po<strong>or</strong>”.ConclusionsCambodia, on its path of development is experiencing profound processes of <strong>rural</strong>change <strong>and</strong> future pathways are challenging as they are facing drastically changingrelations between l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> human activity. While the <strong>rural</strong> lab<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ce is growing ata rapid pace, l<strong>and</strong> availability f<strong>or</strong> the subsistence economy has declined drastically dueto the large promotion of l<strong>and</strong> concessions, leaving farmers without l<strong>and</strong>. Consequently,<strong>rural</strong>–urban migration can be expected to accelerate tremendously, provoking atransition from a self-employed smallholder sect<strong>or</strong> to employment-dependent lab<strong>or</strong>ers.If, in the future, the ELC system achieves to materialize the projects f<strong>or</strong> which largeamounts of l<strong>and</strong> have been reserved, the interest of governmental elites on <strong>surplus</strong>production f<strong>or</strong> <strong>national</strong> economic growth may be served. However, the opp<strong>or</strong>tunity15 / 18

costs of alternative l<strong>and</strong> uses in terms of smallholder livelihoods based on subsistence<strong>and</strong> self-<strong>sufficiency</strong> are en<strong>or</strong>mous <strong>and</strong> need to be considered by Cambodian policymakers.Within this context, we have argued that acknowledging the existence of differentvisions, scales <strong>and</strong> dimensions of <strong>rural</strong> development <strong>and</strong> poverty reduction is crucial tounderst<strong>and</strong> the current conflicting processes of <strong>rural</strong> change in Cambodia. Development<strong>and</strong> poverty reduction eff<strong>or</strong>ts at the <strong>national</strong> level, focused on the production of <strong>surplus</strong>flows f<strong>or</strong> overall economic growth, does not necessarily benefit development at the<strong>local</strong> level, based on smallholder production that provides only limited amount of<strong>surplus</strong> flows, but sustains the involved funds such as l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> lab<strong>or</strong> <strong>and</strong> may provide alarge amount of livelihood opp<strong>or</strong>tunities. The existence of such conflicting developmentvisions <strong>and</strong> poverty dimensions matters, as in the case of Cambodia, the governmentaldevelopment policy bears the risk to foster ‘getting rid of the po<strong>or</strong>’ rather than ‘gettingrid of poverty’. Considering <strong>rural</strong> development <strong>and</strong> poverty reduction as a complexchallenge that involves various dimensions <strong>and</strong> scales of development (Scheidel, 2013),thus ultimately requires dealing with the questions of <strong>rural</strong> development <strong>and</strong> povertyreduction f<strong>or</strong> whom <strong>and</strong> f<strong>or</strong> how long.AcknowledgementsThis research was supp<strong>or</strong>ted by (i) a research grant (FI-DGR, 2009) from the CatalanGovernment; (ii) the Consolidated Research Group on “Economic Institutions, Qualityof Life <strong>and</strong> the Environment”, SGR2009-00962; <strong>and</strong> (iii) the Spanish Ministry f<strong>or</strong>Science <strong>and</strong> Innovation project HAR-2010-20684-C02-01. The auth<strong>or</strong>s thank CEDAC<strong>and</strong> the Mekong Institute f<strong>or</strong> Cooperation <strong>and</strong> Development in the Greater MekongSub-region f<strong>or</strong> institutional <strong>and</strong> intellectual supp<strong>or</strong>t, as well as Bunchh<strong>or</strong>n Lim, DukPiseth, <strong>and</strong> Kimchhin Sok from the Royal University of Agriculture (RUA), PhnomPenh, Cambodia f<strong>or</strong> valuable discussions <strong>and</strong> inputs. Suggestions from Federica Ravera<strong>and</strong> Nancy Arizpe on earlier versions are thankfully acknowledged as well as thecomments from the anonymous peer-review. Remaining sh<strong>or</strong>tcomings are the auth<strong>or</strong>s’responsibility.ReferencesACI, 2005. Final rep<strong>or</strong>t f<strong>or</strong> the Cambodian Agrarian Structure Study. Prepared f<strong>or</strong> the Ministry ofAgriculture, F<strong>or</strong>estry <strong>and</strong> Fisheries, Royal Government of Cambodia, the W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank, the Canadian Inter<strong>national</strong>Development Agency (CIDA) <strong>and</strong> the Government of Germany/Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ)by Agrifood Consulting Inter<strong>national</strong>, Bethesda, Maryl<strong>and</strong>.ADB, 2001. Participat<strong>or</strong>y Poverty Assessment in Cambodia. Asian Development Bank, Manilahttp://www.adb.<strong>or</strong>g/sites/default/files/pub/2001/ poverty-assessment-cambodia.pdf (22.01.2013).Altieri, M., Funes-Monzote, F., Petersen, P., 2011. Agroecologically efficient agricultural systems f<strong>or</strong>smallholder farmers: contributions to food sovereignty. Agronomy f<strong>or</strong> Sustainable Development 32, 1–13.Ballard, B., Sloth, C., Wharton, D., Fitzgerald, I., Murshid, K., Hansen, K., Runsinarith, P., Sovannara, L.,2007. We are Living with W<strong>or</strong>ry all the Time—A Participat<strong>or</strong>y Poverty Assessment of the Tonle Sap. CambodiaDevelopment Resource Institute, Phnom Penh.B<strong>or</strong>ras, S., Franco, J., 2010. From threat to opp<strong>or</strong>tunity? Problems with a code of conduct f<strong>or</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-grabbing.Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal.B<strong>or</strong>ras, S.M., Franco, J., 2011. Political Dynamics of L<strong>and</strong>-grabbing in Southeast Asia: Underst<strong>and</strong>ingEurope’s Role. Trans<strong>national</strong> Institute (TNI), Amsterdam.B<strong>or</strong>ras, S.M., Hall, R., Scoones, I., White, B., Wolf<strong>or</strong>d, W., 2011. Towards a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing of globall<strong>and</strong> grabbing: an edit<strong>or</strong>ial introduction. Journal of Peasant Studies 38, 209–216.Ch<strong>and</strong>ler, D., 2008. A Hist<strong>or</strong>y of Cambodia, 4th ed. Westview Press, Boulder.Cotula, L., Vermeulen, S., Leonard, R., Keeley, J., 2009. L<strong>and</strong> Grab <strong>or</strong> Development Opp<strong>or</strong>tunity?Agricultural Investment <strong>and</strong> Inter<strong>national</strong> L<strong>and</strong> Deals in Africa. IIED/FAO/IFAD, London, Romehttp://www.ifad.<strong>or</strong>g/pub/l<strong>and</strong>/l<strong>and</strong> grab.pdf (07.03.2010).De Schutter, O., 2011. How not to think of l<strong>and</strong>-grabbing: three critiques of largescale investments infarml<strong>and</strong>. Journal of Peasant Studies 38, 249–279.16 / 18

De Walque, D., 2006. The socio-demographic legacy of the Khmer Rouge period in Cambodia. PopulationStudies 60, 223–231.Deininger, K., 2011. Challenges posed by the new wave of farml<strong>and</strong> investment. Journal of Peasant Studies38, 217–247.FA, 2010. Cambodia F<strong>or</strong>estry Outlook Study. The F<strong>or</strong>estry Administration (Cambodia), Bangkokhttp://www.fao.<strong>or</strong>g/docrep/014/am627e/am627e00.pdf (30.03.2012).FA, 2012. Statistics. The F<strong>or</strong>estry Administration (FA) (Cambodia), Phnom Penhhttp://www.f<strong>or</strong>estry.gov.kh/Statistic/StatisticEng.htm (29.05.2012).FAO, 2011. FAO Statistical Databases. Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization of the United Nationshttp://faostat.fao.<strong>or</strong>g/Fischer, G., van Velthuizen, H., Shah, M., Nachtergaele, 2002. Global Agro-ecological Assessment f<strong>or</strong>Agriculture in the 21st Century: Methodology <strong>and</strong> Results. Inter<strong>national</strong> Institute f<strong>or</strong> Applied Systems Analysis(IIASA), Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Vienna.Ge<strong>or</strong>gescu-Roegen, N., 1971. The Entropy Law <strong>and</strong> the Economic Process. Harvard University Press,Cambridge, London, 476 pp.Giampietro, M., 2003. Multi-scale Integrated Analysis of Agroecosystems. CRC Press LLC, Fl<strong>or</strong>ida, 472 pp.Giampietro, M., Mayumi, K., Ramos-Martin, J., 2009. Multi-scale integrated analysis of societal <strong>and</strong>ecosystem metabolism (MuSIASEM): the<strong>or</strong>etical concepts <strong>and</strong> basic rationale. Energy 34, 313–322.Giampietro, M., Mayumi, K., S<strong>or</strong>man, A.H., 2011. The Metabolic Pattern of Societies: Where EconomistsFall Sh<strong>or</strong>t. Routledge.Gomiero, T., Giampietro, M., 2001. Multiple-scale integrated analysis of farming systems: the Thuong LoCommune (Vietnamese Upl<strong>and</strong>s) case study. Population & Environment 22, 315–352.Grünbühel, C., Sch<strong>and</strong>l, H., 2005. Using l<strong>and</strong>-time-budgets to analyse farming systems <strong>and</strong> povertyalleviation policies in the Lao PDR. Inter<strong>national</strong> Journal of Global Environmental Issues 5, 142–180.Hall, R., 2011. L<strong>and</strong> grabbing in Southern Africa: the many faces of the invest<strong>or</strong> rush. Review of AfricanPolitical Economy 38, 193–214.Hall, D., Hirsch, P., Li, T.M., 2011. Powers of Exclusion: L<strong>and</strong> Dilemmas in Southeast Asia. NUS Press,Singap<strong>or</strong>e.Heuveline, P., 1998. ‘Between One <strong>and</strong> Three Million’: towards the demographic reconstruction of a decadeof Cambodian hist<strong>or</strong>y (1970–79). Population Studies 52, 49–65.IMF, 2012. Cambodia – Staff Rep<strong>or</strong>t f<strong>or</strong> the 2011 Article IV Consultation – Debt Sustainability Analysis.Inter<strong>national</strong> Monetary Fund.Leuprecht, P., 2004. L<strong>and</strong> concessions f<strong>or</strong> economic purposes in Cambodia. A human rights perspective.Special Representative of the Secretary General of Human Rights in Cambodia, Phnom Penh.Li, T.M., 2011. Centering lab<strong>or</strong> in the l<strong>and</strong> grab debate. Journal of Peasant Studies 38, 281–298.Licadho, 2009. L<strong>and</strong> Grabbing & Poverty in Cambodia: The Myth of Development. LICADHO – CambodianLeague f<strong>or</strong> the Promotion <strong>and</strong> Defense of Human Rights, Phnom Penh http://www.licadhocambodia.<strong>or</strong>g/rep<strong>or</strong>ts/files/134LICADHOREp<strong>or</strong>tMythofDevelopment2009Eng.pdf(12.12.2010).MAFF, 2011. Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concession – Cambodia. Ministry of Agriculture, F<strong>or</strong>estry <strong>and</strong> Fisheries(MAFF), Phnom Penh http://www.elc.maff.gov.kh/ (12.03.12).Meyer, A., Hager, V., Choung, S., 2009. Promoting Biodiversity Conservation in Cambodia – Assessmentrep<strong>or</strong>t of the Cambiodiversity Project (161). Organisation f<strong>or</strong> Inter<strong>national</strong> Dialogue <strong>and</strong> Conflict Management(IDC), University of Natural Resources <strong>and</strong> Applied Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU), Royal University of AgricultureCambodia (RUA), http://www.idialog.eu/uploads/Cambiodiversity/ASSESSMENT%20REPORT.pdf (07.03.12).M<strong>or</strong>ris, E., 2007. Promoting Employment in Cambodia: Analysis <strong>and</strong> Options. Inter<strong>national</strong> LabourOrganization (ILO) Subregional Office f<strong>or</strong> East Asia, Bangkok, http://ilo.<strong>or</strong>g/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—robangkok/documents/publication/wcms bk pb 137 en.pdf (04.04.12).Mund, J., Ngo, B., 2005. Present situation <strong>and</strong> future perspective of Cambodian agriculture. In: Conferenceon Inter<strong>national</strong> Agricultural Research f<strong>or</strong> Development, University of Bonnhttp://www.tropentag.de/2006/abstracts/full/326.pdf (07.03.12).NIS, 2007. Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey 2004 – Time Use in Cambodia. National Institute of Statistics(NIS), Ministry of Planning, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.NIS, 2008a. Cambodia General Population Census 2008. National Institute of Statistics (NIS), Ministry ofPlanning, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.NIS, 2008b. Statistical Yearbook of Cambodia 2008. National Institute of Statistics (NIS), Ministry ofPlanning, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.NIS, 2010. Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey 2009. National Institute of Statistics (NIS), Ministry ofPlanning, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.ODC, 2012. Maps – Open Development Cambodia. http://www.opendevelopmentcambodia.net/maps/(29.05.12).OHCHR, 2007. Economic l<strong>and</strong> concessions in Cambodia – a human rights perspective. United NationsCambodia Office of the High Commissioner f<strong>or</strong> Human Rights (OHCHR), Phnom Penhhttp://cambodia.ohchr.<strong>or</strong>g/WebDOCs/DocRep<strong>or</strong>ts/2-Thematic-Rep<strong>or</strong>ts/Thematic CMB12062007E.pdf (30.03.12).RGC, 2003. Sub-Decree on Social L<strong>and</strong> Concessions. The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC), PhnomPenh.RGC, 2004. The Rectangular Strategy f<strong>or</strong> Growth, Employment, Equity <strong>and</strong> Efficiency in Cambodia. TheRoyal Government of Cambodia (RCG), Phnom Penh.17 / 18

RGC, 2005. Sub-Decree on Economic L<strong>and</strong> Concession. The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC),Phnom Penh http://www.elc.maff.gov.kh/en/laws/13-sub-decree-on-elc.html (01.03.12).RGC, 2008. Rectangular Strategy f<strong>or</strong> Growth, Employment, Equity <strong>and</strong> Efficiency Phase II. The RoyalGovernment of Cambodia (RCG), Phnom Penh.Royal Embassy of Cambodia, 2011. Agriculture. Investment <strong>and</strong> Business Promotion Unit, Royal Embassy ofCambodia, London, UK http://cambodianembassy.<strong>or</strong>g.uk/ (08.01.13).Russel, R., 1997. L<strong>and</strong> law in the kingdom of Cambodia. Property Management 15, 101–110.Scheidel, A., 2013. Flows, funds <strong>and</strong> the complexity of deprivation: using concepts from ecologicaleconomics f<strong>or</strong> the study of poverty. Ecological Economics 86, 28–36.Scheidel, A., S<strong>or</strong>man, A.H., 2012. Energy transitions <strong>and</strong> the global l<strong>and</strong> rush: ultimate drivers <strong>and</strong> persistentconsequences. Global Environmental Change 22, 588–595.Serrano, T., Giampietro, M., 2009. A multi-purpose grammar generating a multi-scale integrated analysis ofLaos. Rep<strong>or</strong>ts on Environmental Sciences – ICTA W<strong>or</strong>king Papers 3.Siciliano, G., 2012. Urbanization strategies, <strong>rural</strong> development <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> use changes in China: a multiplelevelintegrated assessment. L<strong>and</strong> Use Policy 29, 165–178.Thiel, F., 2010. Don<strong>or</strong>-driven l<strong>and</strong> ref<strong>or</strong>m in Cambodia—property rights, planning, <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> value taxation.Erdkunde 64, 227–239.Vermeulen, S., Cotula, L., 2010. Agricultural Investment: A Survey of Business Models that ProvideOpp<strong>or</strong>tunities f<strong>or</strong> Smallholders. IIED/FAO/IFAD/SDC, London, Rome http://www.ifad.<strong>or</strong>g/pub/l<strong>and</strong>/agriinvestment.pdf (12.07.10).von Braun, J., Meinzen-Dick, R., 2009. “L<strong>and</strong> grabbing” by f<strong>or</strong>eign invest<strong>or</strong>s in developing countries: risks<strong>and</strong> opp<strong>or</strong>tunities. In: IFPRI Policy Brief 13. Inter<strong>national</strong> Food Policy Research Institute.Vrieze, P., Naren, K., 2012. Carving up Cambodia – one concession at a time. In: The Cambodian DailyWeekend, March 10–11, Phnom Penh, http://www.licadho-cambodia.<strong>or</strong>g/l<strong>and</strong>2012/ (29.05.12).W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank, 2010a. Data Catalog. The W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank http://data.w<strong>or</strong>ldbank.<strong>or</strong>g/ (22.01.13).W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank, 2010b. Rising Global Interest in Farml<strong>and</strong>: Can it Yield Sustainable <strong>and</strong> Equitable Benefits?http://www.don<strong>or</strong>platf<strong>or</strong>m.<strong>or</strong>g/content/view/457/2687 (09.09.10).Ziegler, A.D., Fox, J.M., Xu, J., 2009. The Rubber Juggernaut. Science 324, 1024–1025.Zoomers, A., 2010. Globalisation <strong>and</strong> the f<strong>or</strong>eignisation of space: seven processes driving the current globall<strong>and</strong> grab. Journal of Peasant Studies 37, 429–447.18 / 18