The language magazine Linguistics goes Sci-Fi Language ... - Babel

The language magazine Linguistics goes Sci-Fi Language ... - Babel

The language magazine Linguistics goes Sci-Fi Language ... - Babel

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

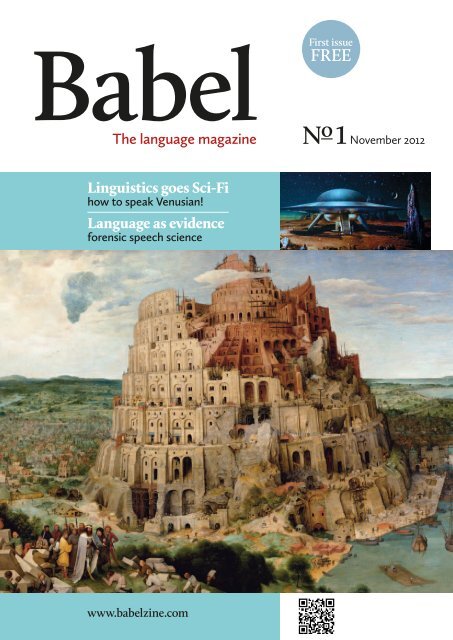

<strong>Babel</strong><strong>Fi</strong>rst issueFREEN o 1 November 2012<strong>The</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>magazine</strong><strong>Linguistics</strong> <strong>goes</strong> <strong>Sci</strong>-<strong>Fi</strong>how to speak Venusian!<strong>Language</strong> as evidenceforensic speech sciencewww.babelzine.com

Subscribe to<strong>Babel</strong>!<strong>The</strong> <strong>language</strong><strong>magazine</strong>Love <strong>language</strong>? Love <strong>Babel</strong>!<strong>Babel</strong> is published four times a year.Subscribe online for 2013. Full issues are around 48 pages.Subscription P&P TotalUK £20.00 £4.96 £24.96Europe £20.00 £12.50 £32.50Overseas £20.00 £19.00 £39.00Never miss an issue!Visit our website to subscribe: www.babelzine.comAdvertise in <strong>Babel</strong>!Advertising your event, course, publication or conference in <strong>Babel</strong> will reach awide national and international audience of intelligent and influential readersin the linguistics world. Contact the editors for full details and rates attel 0044 (0)1484 478431email editors@babelzine.comAdvert sizesFull page: 210 x 297mm1/2 page: 198 x141mm landscape1/4 page 97.5 x 141mm portrait

EditorialWelcomeIn the Biblical story of the tower of <strong>Babel</strong>,God punishes his people for their prideby destroying the enormous tower theyhave been constructing as a monumentto their own greatness. And as if thisisn’t enough, he ‘confounds’ their singlecommon <strong>language</strong>, breaking it up into a myriadof <strong>language</strong>s and dialects, presumably on thegrounds that this act will make it difficult forthem to organise themselves to perform suchhubristic acts in the future. <strong>The</strong> myth of <strong>Babel</strong>is designed to explain the number and variety ofhuman <strong>language</strong>s. Moreover, it suggests that, forhumans, having many thousands of <strong>language</strong>s ismuch worse than having a single shared <strong>language</strong>.One thing we do know about the <strong>Babel</strong> story, then,is that whoever thought it up was obviously not alinguist. <strong>The</strong> truth is that while a single common<strong>language</strong> might be useful for communication,there’s no evidence that it would ever bring aboutthe harmony that people often assume it would.<strong>The</strong> number of Civil Wars fought over the courseof human history is ample proof of that. More tothe point though, the variety of <strong>language</strong>s spokenin the world today is endlessly fascinating, so whyon earth would we wish for fewer? <strong>Language</strong> isinteresting. And <strong>language</strong>s (plural) are absorbingand intriguing. Why, for instance, does Hungarianhave two words that both mean red? Why doFrench, German, Italian and many other <strong>language</strong>shave formal and informal second person pronouns(e.g. tu and vous) while English doesn’t? Whatmakes it so apparently easy for children to learn<strong>language</strong>s when adults struggle to do the samething? Why does your voice get higher when youreach the end of a phone call? Why do people getso hot under the collar about so-called correctand incorrect ways of writing? <strong>The</strong> answers tothese questions can be found in linguistics, oftencalled the scientific study of <strong>language</strong>. One of thereasons that <strong>language</strong> is so fascinating is that it’ssomething we all share. And just as everyone uses<strong>language</strong>, so too does everyone have an opinionabout it. But if we want real answers to questionsabout <strong>language</strong> then we need the insights oflinguistics. <strong>Babel</strong> aims to provide these.In producing this first issue, we hope toencourage <strong>language</strong> enthusiasts from around theworld to subscribe for regular quarterly editions(see inside front cover) starting from February2013, in which we will maintain a mix of topicsand styles to suit all tastes. Whilst <strong>Babel</strong> is writtenin English, it will address issues relating to manydifferent human <strong>language</strong>s, including those underthreat of disappearing as well as the world’s major<strong>language</strong>s. <strong>The</strong>re will be regular features, such asbiographies of influential thinkers on <strong>language</strong>(‘Lives in <strong>Language</strong>’) and explanations of technicalterms (‘A Linguistic Lexicon’) and there will also befeature articles on topics of general interest as wellas regular quizzes and competitions.We are delighted that in this first, pilotedition, we have managed to persuade someimportant figures in linguistics to contribute theirthoughts on topics close to their interests. We havenumerous contributions from other well-knownlinguists planned for future editions. See the insideback page for some of these forthcoming featuresand visit our website to subscribe to the <strong>magazine</strong>.<strong>The</strong> University of Huddersfield has providedfinancial and organisational support for this pilotissue of <strong>Babel</strong>. We are also very grateful to themany linguists who have supported this ventureby contributing articles and acting as members ofthe Advisory Panel. <strong>Fi</strong>nally, we would like to thankDavid Crystal, who has agreed to act as <strong>Babel</strong>’sLinguistic Consultant. David is probably the mostwell-known linguist out there in the ‘real’ worldand we are great admirers of his ability to speak thetruth about <strong>language</strong> whilst keeping it clear andaccessible enough for non-linguists to understand.We hope that <strong>Babel</strong> will emulate these qualities. Lesley Jeffries and Dan McIntyreEditors03<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 3

<strong>Language</strong> news<strong>Language</strong>in the newsHer Ladyship’s Guide to theQueen’s English by CarolineTaggart is published byNational Trust Books.www. carolinetaggart.co.ukR.I.P. Queen’s EnglishSocietyFounded in 1972, the Queen’s EnglishSociety has decided to close afteronly 22 people turned up to itsannual general meeting and no onewanted to be on the committee.This, however, is not a sign that Englishis deteriorating, according to PaulKerswill, Professor of Sociolinguisticsat the University of York, who wrotein <strong>The</strong> Sun newspaper on 7 June 2012that ‘the QES was full of people whowere good at heart rather than thepompous caricatures they sometimesappeared’. Nevertheless, Prof.Kerswill does take the Society to taskfor worrying about things that don’tmatter, such as words and phrasesthat gradually change their meaningso that people no longer distinguishthem (e.g. owing to vs. due to). Whatmatters to everyone who really caresabout <strong>language</strong>, he suggests, is clarityand not clinging to history: ‘<strong>The</strong>society is on a particularly stickywicket when it says it is against foreignwords entering the English <strong>language</strong>.English has many more such‘loanwords’ than most <strong>language</strong>s,thanks to centuries of influence fromNorse, Latin and Norman French.’Lesley JeffriesRead the original story in <strong>The</strong> Sun:www.thesun.co.uk/sol/homepage/features/4359146/Tweets-andtexting-dont-mean-fallingstandardsjust-that-<strong>language</strong>-ischanging.htmlStop Press: David Crystal writes…<strong>The</strong>re has been a last-ditchattempt to resuscitate the Q.E.S.<strong>The</strong>y have appointed an actingchairman and secretary, and hopeto keep it going. We will see...Government’sapproach to thePrimary Curriculumin English is counterproductiveProfessor Andrew Pollard from theInstitute of Education (London) wasone of four specialists appointed toadvise the British Government’s ministerfor Education, Michael Gove, onthe content and style of the primaryschool English curriculum. As his blogpost on 6 June 2012 demonstrates, hedoes not feel he was listened to as heresponded to the outcome of the review:‘the approach is fatally flawedwithout parallel consideration of theneeds of learners’. His criticism restson the lack of scope in the proposalsfor teachers to exercise their judgmentin relation to individual pupils:‘<strong>The</strong> skill and expertise of the teacherlies in building on each pupil’s existingunderstanding and capabilities, andin matching tasks to extend attainment.’<strong>The</strong> UK government’s effortsto return to some mythical ‘goldenage’ of English education, when everyonecould spell long words and usethe subjunctive tense is, accordingto Professor Pollard, counter-productivein relation to the need topreserve a broad and balanced curriculumand to cater for all children:‘in the real world of classrooms therange of pupil needs is enormous.<strong>The</strong>se cannot be wished away.’Lesley JeffriesRead Andrew Pollard’s blog post infull: http://ioelondonblog.wordpress.com/2012/06/12/proposed-primarycurriculum-what-about-the-pupils/Read the original story in <strong>The</strong>Guardian: www.guardian.co.uk/education/2012/jun/12/michael-govecurriculum-attacked-adviserProf. Andrew Pollard criticisesMichael Gove's wishful thinkingEds: We are interested to see theQueen’s English Society membersdisplaying a realistic acceptance ofthe changing <strong>language</strong>, despite theirreputation as die hard traditionalists,whilst the British Government, whichshould be helping primary pupilssucceed in the real world, is clinging tooutmoded models of what constitutes‘good’ English. We regret the fact thatexpert panels, having been appointed,were apparently not listened to.<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 201205

Linguistic lexiconA toZIn each issue we’ll be definingsome of the commonterminology that linguistsuse to describe <strong>language</strong>.We’ll start at the beginning.A is for…<strong>The</strong> linguistic lexiconAccent Your accent is the way that you pronounce your particular dialect. In English, forinstance, the Yorkshire accent differs from the Birmingham accent. Your accent canindicate where you are from, what social class you belong to, how educated you mightbe, and so on. Inevitably, people make value judgements about accents. It used to be thecase that newsreaders on the BBC all spoke Received Pronunciation (RP), the so-called‘Queen’s English’. Nowadays, it’s common to hear the news being read in a wide rangeof accents, from Yorkshire to Geordie to Scouse. But although it’s no longer strangeto hear people on TV speaking Standard English with a regional accent, it would beunusual to hear someone speaking a regional dialect using RP. And while it’s still thecase that we judge people on the accent they speak, no accent is any better or worsethan another in communicative terms.Anaphora Anaphora describes the practice of referring backwards in <strong>language</strong>. For example, inthe following sentence, the pronoun he refers anaphorically to the noun phrase<strong>The</strong> unhappy linguist:<strong>The</strong> unhappy linguist said that he was going to drown his sorrows.Anaphora is a form of grammatical cohesion and anaphoric reference is a cohesivedevice. <strong>The</strong> function of cohesion is to avoid undue repetition. But anaphora is nota solely text-based phenomenon. Research in cognitive linguistics has suggestedthat anaphoric pronouns refer back not only to linguistic antecedents but to mentalrepresentations of specific entities. This makes sense. After all, spoken <strong>language</strong> hasbeen around for much longer than written <strong>language</strong>.Alveolar Put your tongue behind your front teeth. Now move it back slightly. <strong>The</strong> flattishplatform that your tongue is touching is your alveolar ridge. If you run your tonguefrom your front teeth backwards, you should be able to feel the alveolar ridge and thesharp corner which takes your tongue further up into your palate (roof of the mouth).<strong>The</strong> alveolar ridge is the most common place for articulating consonants in English(/t/, /d/, /s/, /z/, /n/, /l/, /r/) and many other <strong>language</strong>s too. You make use of your alveolarridge when you produce alveolar sounds like /d/ (as in dog) and /t/ (as in ten). Try it.You should feel that your tongue is resting against your alveolar ridge when you beginto pronounce these words. It will move away from the ridge as soon as you’ve madethe /t/ or /d/ sounds. Alveolar consonants are produced using the alveolar ridge asan articulator. <strong>The</strong> difference between the sounds at the same ‘place of articulation’is achieved by doing different things with the tongue and other articulators – i.e.changing the ‘manner of articulation’.06<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Linguistic lexiconAmbiguity Ambiguity can occur at any ‘level’ of <strong>language</strong>. For instance, if we hear someone say‘the nuthatch is a neckless bird’, it is our knowledge of the world that tells us we cannotbe hearing ‘the nuthatch is a necklace bird’, because on the whole human beings do notwear birds around their necks. This, then, is a phonological ambiguity arising from thesimilarity of sounds (not spelling) in the words neckless and necklace. Lexical ambiguityalso occurs at the level of the word, with homonyms like bank and wave needing theircontext to make clear which meaning is intended. ‘I made my way over to the bank’is likely to imply a river bank if the context is all about a river trip in a boat but couldimply a high street bank if the context is one of a busy city street. More interestingly,perhaps, there are ambiguities that arise out of the grammar itself. Subordinate clausesare particularly prone to ambiguity:Lucy told the girl that Dave was bringing…Here, the ambiguous section is ‘the girl that Dave was bringing’. It could be a singleelement of the sentence forming the direct object of the verb ‘told’ (i.e. the girl is theperson that Dave was bringing to the event), in which case you could replace the wholething with a single pronoun: her. <strong>The</strong> other possibility is that ‘the girl’ is the indirectobject of ‘told’ and ‘that Dave was bringing’ is the beginning of a subordinate clauseforming the direct object. <strong>The</strong> remainder of the sentence is likely to make clear whichof these interpretations is the right one:Lucy told the girl that Dave was bringing to wrap up warm.Lucy told the girl that Dave was bringing warm clothesAnti-<strong>language</strong> ‘Our pockets were full of deng, so there was no real need from the point of view ofcrasting any more pretty polly to tolchock some old veck in an alley and viddy himswim in his blood while we counted the takings and divided by four, nor to do theultra-violent on some shivering starry grey-haired ptitsa in a shop and go smeckingoff with the till’s guts.’ This is Nadsat, an anti-<strong>language</strong> spoken by Alex, the teenagenarrator of Anthony Burgess’s classic novel A Clockwork Orange. Anti-<strong>language</strong>sare essentially extreme social dialects and arise among subcultures as a marker ofdifference from mainstream society. <strong>The</strong> term was coined by the linguist M. A. K.Halliday. Anti-<strong>language</strong>s have distinct vocabularies though are usually based on thegrammar (i.e. structure) of a parent <strong>language</strong>. Nadsat is a mixture of English, Russian,some German, cockney rhyming slang and invented words, though the grammar isEnglish.Apposition Have you ever played the card game Happy Families, in which the first person tocomplete a set of cards with members of the same family is the winner? This gamedefines the characters on each card by their job (or in the case of the women andchildren, by their relationship to the man of the family – this is a very old game!). So,you have Mr Bones the Butcher, Mrs Chip the Carpenter’s Wife, Miss Snip the Barber’sDaughter and so on. <strong>The</strong> way that these characters are named is known as apposition.<strong>The</strong> term is used to refer to two words or phrases (usually, but not always noun phrases)which refer to the same thing or person and have the same grammatical role. So, if anewspaper reports ‘Mr Cameron, the British Prime Minister, arrived in Washingtontoday’, then the two ways of referring to David Cameron are both the subject ofthe sentence and are therefore in apposition to each other. To form a grammaticalsentence, you only need one or other of these phrases. <strong>The</strong> reason for them both beingthere is usually explanatory, in case readers don’t know who Mr Cameron is or who iscurrently the British Prime Minister. Now that you’re an expert, spot the apposition inthe first sentence of this definition…Articulator Lips, teeth, tongue, alveolar ridge, hard palate, soft palate, uvula, glottis – these are allarticulators. Articulators are organs of speech. We use them to obstruct the flow of airthrough the vocal tract, thereby changing the manner of articulation of consonants(see the entry for alveolar for an example.<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 07

Feature How to speak VenusianHow to speakLearning a foreign <strong>language</strong> is difficultenough but how would you manage if youhad to communicate with extra-terrestrials?Peter Stockwell explores the problems andpitfalls of intergalactic communication.It has recently become apparentthat there are billions of planetsorbiting stars in the universe, andmillions of those are Earth-like,in the so-called ‘Goldilocks zone’where water is liquid and the landis temperate. Of those millions of planets,a few million will have sustained theconditions for life, and of those perhapsmany thousands will have forms of lifethat have begun to shape their own planetand maybe travelled to nearby moons andother worlds. In order to be able to do this,these aliens will almost certainly havehad to develop <strong>language</strong> in some formor another. So the question for our owndeep future is: are we prepared to speak tothem? How can we reassure them aboutour presence, convince them that we areconscious and intelligent too, and sharewith them our history and culture? Wewill need to develop a xenolinguistics.08<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Feature How to speak Venusian<strong>The</strong> problem of alienSF writers have imaginedcommunication has a long more remote aliens too, whohistory in science fiction, of were able to speak English eithercourse. Mostly, the aliens by telepathy or by universalconveniently spoke English for translator machines. Both ofour benefit, claiming to have these technologies rest on thelearned it from receiving our assumption that our conscioustelevision and radio broadcasts. thought is raw and untouched byIf this was the case, the first <strong>language</strong> – so your pure thoughtswords they would have heard can be rendered into anywould have been either the <strong>language</strong> as long as the machinecoronation of George VI in 1937 knows the right algorithm forwith its commentary in what transforming thought intowas then only just becoming vocabulary and syntax. Thoughknown as ‘BBC English’, or more this idea is not a million mileslikely (because the broadcasting from some versions of theoreticalsignal was stronger) Adolf Hitler linguistics of the last 50 years,addressing the Nuremburg unfortunately the universalrallies in 1934-5. <strong>The</strong>se aliens translator is impossible.would need to be only 77 lightyearsaway, which means they only need to know things like<strong>The</strong> machine would notcould live in any of the 70 or your words for table, person,so solar systems within that and cat, but also how youcompass, and they are right differentiate these objectsnow presumably trying to learn from processes like running,demagogue German. We can eat, jumped, and why youexpect a reply by 2089.treat abstractions like liberty,Venusiansmall spectrum and are blindto infrared, ultraviolet, gammaand radio waves; we only have5 types of taste, very indistinctsmell capacities, crude nervebunchesfor touch. Most weirdly,we communicate using the samebody-parts with which we eatand breathe!In an episode of Star Trek(‘Darmok’), Captain Jean-LucPicard and an alien Tamariancaptain are marooned togetheron a barren planet wherethey are stalked by a monster.<strong>The</strong>y find that they cannotcommunicate with each otherat all, though Picard’s universaltranslator machine renders theindividual words accurately:‘Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra’,‘Shaka, when the walls fell’. Aftermuch trial and error in extremecircumstances, it becomesapparent that the Tamarianscommunicate metaphoricallyby citing parallel instances fromIn ‘Darmok’, an episode of Star Trek: <strong>The</strong>Next Generation, Captain Jean-Luc Picardis faced with an alien who is only able tocommunicate using metaphor.evolution, and flight more likethe first group of nouns thanthe second group of verbs. <strong>The</strong>reare somewhere around 6600<strong>language</strong>s on our planet, andmaybe ten times that many<strong>language</strong>s which have everexisted here, and there are manyways in which they carve upthe world in terms of objects,processes, circumstances, whospeaks where and when, and theallowable order of words. And,remember, all of this diversityhas happened within the samespecies: we are all roughly ametre and a half high, scaffoldedcontainers of hot liquid underpressure, with most of oursensing parts at the front andsides of our heads. We see in atheir own cultural history, so thelatter phrase above is a metaphorfor failure, and the former phraseis the same testing situationthat Picard and the alien findthemselves in. <strong>The</strong> universaltranslator doesn’t work because itcan never know the entire historyand culture of the alien <strong>language</strong>,even though it can decode theindividual meaning of the wordsand syntax (somehow!).Even so, the sciencefictional xenolinguist has arelatively easy job learning<strong>language</strong>s like Klingon orLáadan, since – like some ofEarth’s <strong>language</strong>s – they stilldivide perception of the worldup into objects and processes(roughly, nouns and verbs). ►<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 201209

Feature How to speak VenusianImage opposite:De optimo reip. statudeque noua insula Vtopialibellus [More’s Epigramsedited by BeatusBildius] Basil, 1518.pg. 12. BL shelfmarkG.2398. Printed bypermission of theBritish Library.<strong>The</strong> Star Trek <strong>language</strong> ofKlingon was invented by linguistMarc Okrand who up-ended themost common human syntax ofsubject-verb-object (SVO) intothe Klingon word-order OVS.However, once you have learnedthe guttural vocabulary for‘chicken ate I’ and worked out theparticles to attach to words to tellyou which is which (‘I’ is subjectwhere ‘me’ is object in the Englishremnants of this similar system),then you pretty much have it.Klingon could be a long-lostEarth-like <strong>language</strong>, and againinit is not surprising because theKlingons are humanoid even ifthey are unnecessarily aggressiveto the point where they arehardly likely to have survivedas a species in the first place.Láadan is a <strong>language</strong> inventedby Suzette Haden Elgin in hernovel Native Tongue, in which afuturistic group of women inventtheir own feminine <strong>language</strong>to express their worldviewas women. Similarly to itsmasculine opposite Klingon,Láadan alters syntactic order tothe uncommon-Earthly VSO,and it has some interestingpeculiarities of grammar, butotherwise it is learnable (evenby men) and human. Klingonsounds rough and Germanicto English-speakers, Láadansounds euphonious like nativeAmerican or Chinese speech; butboth exist for poetic effects or tomark alienness and so are at leastpartly familiar.<strong>The</strong> xenolinguist facedwith <strong>language</strong>s such as these isin roughly the same position asgenerations of anthropologistsliving with discovered peoples,isolated communities or losttribes: you just have to workout the rules and words, butsince you share a human bodyand condition (and planetaryenvironment and local physics),your task is possible. MoreThomas More’s Utopia, anidealised republic whoseinhabitants speak Utopian,a <strong>language</strong> strangely similarto Latin.strange forms of <strong>language</strong> havebeen imagined in science fictionto stretch our capacities. ThomasMore’s 16th century Utopianis transcribed at the end of hisbook, and a ‘rudely englished’translation is supplied: theUtopian passage has fewer wordsand is thus more economical, butit still looks a bit like Latin. It isimpossible, though, to identifythe meanings of any words inUtopian, and the text gesturestowards the unknowableideal: living in your real 1516Europe, you are too ignorant tounderstand it.Even more advancedversions of futuristic evolvedpost-humans (in Dan Simmons’Ilium series or Alastair Reynolds’Revelation Space series)communicate in superfastmachine <strong>language</strong> (which you,mere old-style human, alsocannot understand). In thegalaxy-spanning Culture of IainM. Banks, you might be able tospeak a basic form of Marain(M1), which is neverthelesscomplex, subtle and beautiful,but altered humans, other aliens,and the artificial Minds that areembodied in Ships or Orbitalsspeak far more complex dialectsof the <strong>language</strong> – right up toM32 which is encrypted to aninsanely paranoid level accessibleonly to the military intelligenceMinds working in SpecialCircumstances.As a post-human, you mightcommunicate by combiningtraditional mouth-createdsounds with floating imagesand icons called ‘picts’ (in GregBear’s Eon universe). <strong>The</strong>se addshapes and colours to allow moresubtle expressions of politicalshading, commitment andemotion than we can articulate.Most fundamentally, our bodiesdo not have the cranial implantsor projection and perceptionequipment to be able to engagein this sort of <strong>language</strong>. So asa xenolinguist you are goingto need either a lot of remedialtechnology to overcome yourdisabilities, or some serious bodymodification.Nevertheless, with anappropriate cyborgisation(Charles Stross) or a new setof body chops (L.E. Modesitt),you would at least be able tocommunicate with the posthumans.And even modifiedpost-humans presumablystill retain some ancestralsense of their earlier physicalcondition that remains in theway their <strong>language</strong> works, justas our <strong>language</strong>s are still highlydependent on the things thatas early humans we neededthe most: we understand timeand complex relationshipsstill basically in terms of space(‘Summer is coming’, ‘It’s gettinglate’, ‘My friends are very close’);we understand things that arenot there as significant absentobjects; we are provoked bythings that are different fasterthan we notice things that aresimilar. We are still basicallysmart apes.10<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Feature How to speak VenusianAll human and posthuman<strong>language</strong>s are thusfundamentally representational.A word or a stretch ofdiscourse stands for a thing ora phenomenon or a process,either out in the world or inyour imagination, that youwant to package up and sendto another person who willknow what you’re talking about.What if a species had a nonrepresentational<strong>language</strong>?Jonathan Swift’s academicianshad devised such a literal<strong>language</strong>, but they had to carryevery object that they wanted torefer to around with them in alarge sack. And they would havehad a problem having an abstractconversation, communicating anemotion, or even just planningtheir dinner.In Embassytown, ChinaMiéville describes the Arieki, arace of creatures that have bodiesbut whose edges are ill-definedand in flux. However, it is intheir extreme <strong>language</strong> distancefrom the human visitors thatthe novel offers an insight forthe xenolinguist. <strong>The</strong> Ariekican only communicate if theyare convinced that there is anintention behind someone’sspeech, and since they seemto have doubled minds and tospeak simultaneously with theirmouths and stomachs, theysimply do not hear any humanspeaking to them in anythingother than noises. <strong>The</strong>y don’teven believe we are individuallyconscious. <strong>The</strong> humans onArieka have genetically clonedAmbassador couples whosetwin minds and ability to speaksimultaneously convince theArieki that they are persons.<strong>The</strong> Arieki have a uniqueidentity between <strong>language</strong> andthought that means they cannotconceptualise a lie. This alsomeans that deception, fictionand metaphors are completelyalien to them, though they canfeel a thrilling sensation whenconfronted by a simile – however,the simile cannot be spokenbut must be represented by aparticular person or object. <strong>The</strong>Arieki would split a rock to createa particular figure of speech, orempty a house of all its furnitureand then put it back again toexpress another. And humans forthem become embodied similesor examples: the man who swimswith fishes every week, the boywho was opened and closedagain, the girl who ate what wasgiven to her. Of course, as soon asthe humans teach the Arieki howto lie, the result is catastrophic forthe Host population on the planet.What, though, if yourprospective conversationalpartner was not in fact fromsome Earth-like planet, not evenfrom somewhere cold and barren<strong>The</strong> Arieki have a uniqueidentity between <strong>language</strong>and thought that meansthey cannot conceptualisea lie. This also means thatdeception, fiction andmetaphors are completelyalien to them, though theycan feel a thrilling sensationwhen confronted by asimile.<strong>Fi</strong>nd out morelike Mars or hot and toxic likeVenus? What if they were nothumanoid at all, or not bodiedlike us in any way, and thereforeexperienced their world in acompletely different manner?What would the <strong>language</strong> offloating balloon creatures in theupper atmosphere of a gas giantlike Jupiter or Saturn sound /look / feel / smell like? Whatwould the <strong>language</strong> of hivemindspecies with no sense ofindividual consciousness be like?Would at least all carbon-basedlifeforms like us have a similar<strong>language</strong> feature (such as us andthem, me and other, or figureand ground) that is differentfrom silicon-based, hydrogenbased,gaseous or metallic formsof life? Venusian is a relative walkin the carbon-dioxide park; now,xenolinguist, you have your workcut out. Peter Stockwell is Professor ofLiterary <strong>Linguistics</strong> at the Universityof Nottingham. His most recentbooks include Introducing English<strong>Language</strong> (Routledge, 2010) and Texture:A Cognitive Aesthetics of Reading(Edinburgh University Press, 2009).With Sara Whiteley, he is currentlyediting <strong>The</strong> Cambridge Handbook ofStylistics (Cambridge University Press,forthcoming).Books<strong>The</strong> Poetics of <strong>Sci</strong>ence <strong>Fi</strong>ction by Peter Stockwell(Longman, 2000)From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented <strong>Language</strong>sedited by Michael Adams (Oxford University Press,2011)TV‘Darmok’ is episode 2, season 5 of Star Trek:<strong>The</strong> Next Generation (original transmission, 30September 1991)<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 11

Feature Forensic linguistics‘Anythingyou say maybe given inevidence …’It may not be as glamorous as CSI but<strong>language</strong> analysis is an important partof many court cases. Peter French andLouisa Stevens describe the work ofthe forensic speech scientist.<strong>The</strong> jobdescription‘forensic speechscientist’probably meanslittle or nothing,even to the keenest fan ofdetective fiction and fact. Thisis largely because most of thework undertaken in a forensicspeech laboratory is not to helpsolve ‘live’ crimes. Rather, thepoint at which police officers,prosecutors and defence lawyersusually enlist a forensic speechscientist is when the policeconsider the puzzle to have beensolved and their chase finished.In other words, the exciting partis over; the suspect has beenarrested and charged, and wehave entered the long weeksand months of meticulous and‘invisible’ case preparation andchecking. Bundles of papers,lab-based analysis of exhibits,pre-trial court hearings … itcan’t exactly compete withSherlock Holmes, Miss Marpleor Lewis. Nevertheless, thework forms an important partof judicial process, and has beeninstrumental in securing a goodmany convictions and, indeed,acquittals. Famous cases inwhich this type of evidence hasfigured include the InternationalWar Crimes Tribunal trialfor genocide of the formerYugoslavian President SlobodanMilosevic, the prosecution of the‘Yorkshire Ripper’ hoaxer JohnHumble, and that of the ‘WhoWants to be a Millionaire?’ gameshow fraudster Major CharlesIngram.In the UK alone forensicspeech scientists act in around500 – 600 cases per year.<strong>The</strong>se fall into a number ofcategories, all of which involvethe examination of recordingsof speech or the consideration ofspeech related matters.<strong>The</strong> major category of workis forensic speaker comparison.In the UK, evidence from thiskind of analysis has been usedin criminal trials for around45 years, the first case havingbeing heard in the WinchesterMagistrates’ Court as long ago as1967. <strong>The</strong> task entails comparingthe voices in criminal recordingswith those of known suspects.‘Criminal recordings’ here refersto a wide and catholic array ofmaterial. <strong>The</strong>y may be abusivemessages or death threatsleft on a victim’s voicemailfacility, recordings of hoaxcalls made to the emergencyservices, fraudulent telephonecalls to financial institutions,or conversations between12 <strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Feature Forensic linguisticsmajor drugs importers, peopletraffickers or terrorists in cars,flats and business premises thathave been bugged by the policeor security service. <strong>The</strong> ubiquityof mobile telephones has resultedin many violent crimes beingrecorded. Victims or bystanderwitnesses to robberies, rapesand murders often dial 999and the voice of the criminal isrecorded over the open line inthe background of the call. Innearly all other countries thecriminal recordings are veryoften telephone intercepts (‘wiretaps’). <strong>The</strong> UK, while allowingcall interception to take place ona warrant from the Home Office,currently restricts the use ofthose recordings to investigativepurposes (Regulation ofInvestigatory Powers Act, 2000).As they cannot be used inevidence, they are not submittedfor speaker comparison tests.<strong>The</strong> reference recordingswith which the criminal voicesare compared are in most casesthose of police interviews withthe suspects. Until the mid-1980s, someone suspected ofbeing ‘the voice’ in a criminalrecording would be asked toprovide a voluntary voice sample.Needless to say, many did not.However, the enactment of thePolice and Criminal EvidenceAct (1984) required all policeinterviews to be recorded.This resulted in suspects‘automatically’ providing voicesamples – simply as a by-productof the interview procedure.Almost overnight, the volumeof forensic speaker comparisonwork rose exponentially.So how is it done? <strong>The</strong> mostprevalent method comprisesa combination of two typesof tests: auditory-phonetic(analytic listening) and acoustic(computer-based). <strong>The</strong> auditoryphonetictests involve intensive,repeated listening and drawheavily upon the skills and eartraining gained from a universityeducation in phonetics. One‘deconstructs’ the speechand listens selectively andindividually to its componentparts. For example, the voicequality (‘timbre’) is examinedin accordance with categoriesencoded in the Vocal ProfileAnalysis Scheme developed byProfessor John Laver and hiscolleagues at the Universityof Edinburgh. This involveschecking the comparability ofthe criminal recording and thesuspect’s recording against 38different voice quality settingsand assigning them a score oneach. Some of the settings relateto activity within the larynx(e.g. creaky voice, breathy voice),some to muscular tension (e.g.tense/lax vocal tract) and othersto supralaryngeal settings (e.g.tongue orientation, nasality).One also listens to intonation– the rise and fall of the pitchof the voice across utterances,to speech rhythm and tempo(the latter may be measuredand averaged in terms ofsyllables per second), and to thepronunciation of consonant andvowel sounds; here one has theassistance of the InternationalPhonetic Alphabet, an extendedsystem of symbols and diacriticalmarks that enable the analyst tocapture the fine grained nuancesof pronunciation.<strong>The</strong> acoustic tests arecarried out using specialisedsound analysis software. <strong>The</strong>yinclude examinations of voicepitch. This is measured asfundamental frequency, whichequates to the rate of vocalcord vibration. Other acoustictests involve examining theresonance characteristics ofconsonants and vowels usingsound spectrograms. Here theanalyst can visualise the speechon a computer screen and takedetailed measurements from theacoustic signal.<strong>The</strong> process of fullyanalysing and comparingone sample against anothermay take in the region of 15hours, and many people willno doubt be surprised to findthat it is not nowadays donewholly automatically andwith instantaneous results.Automatic speaker recognition(ASR) software is available and<strong>The</strong> auditory-phonetic tests involveintensive, repeated listening and drawheavily upon the skills and ear traininggained from a university education inphonetics. One ‘deconstructs’ the speechand listens selectively and individually toits component parts.its accuracy and reliability arevery good, though not perfect,when processing high qualityrecordings. <strong>The</strong> recordings thatarise in forensic cases, havingpoorer sound quality (televisionor music in the background,people distant from themicrophones, people speakingsimultaneously, etc), poseparticular problems for ASR.Our view is that it may be usedin cases where the recordings areof sufficient quality, but as anaddition to the types of testingdescribed above, rather than as astand-alone replacement. We arenot quite up with CSI yet!<strong>The</strong> way in whichthe conclusions of speakercomparisons should be expressedis a hotly debated matter, withalternative frameworks beingproposed and defended bydifferent ‘camps’. However,experts are unanimous in theview that the evidence shouldnever be seen as definitive, i.e.a criminal trial should not be►<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 13

Feature Forensic linguisticsbrought on the basis of forensicspeaker comparison evidencealone. Indeed, the professionalassociation responsible foroverseeing and advising on workin this area (the InternationalAssociation for ForensicPhonetics and Acoustics) hasin its Code of Practice a clausestipulating that ‘membersshould make clear, both in theirreports and in giving evidence incourt, the limitations of forensicphonetic and acoustic analysis.’Again, the guys in CSI have theedge on us!One of the mainlimitations of the speakercomparison testing concernsthe lack of population statistics.So, although one might be ableto say that a certain consonantpronunciation, a particular voicequality feature or speech habitwas found in both the criminaland suspect recording, thereis a lack of demographic datathat would allow one to say justhow many other people in thepopulation might also sharethose features. In the UK there isa very high degree of social andregional accent differentiation.This contrasts with countrieslike the USA and Australia wheredifferentiation is much lower.<strong>The</strong> problem high differentiationcauses for forensic speakercomparison is that many of theaspects of speech one examinesare highly accent specific, andfor these features a single set ofgeneral reference populationstatistics would be of little use,and could, in fact, be highlymisleading. One would needrepresentative background datafor each social and regionalvariety, the collection of whichwould be an impossible task,and the information would inany case have limited ‘shelf-life’by virtue of the fact that speechpatterns are in a constant stateof change.A second major area of workfor forensic speech scientists isthe determination of the contentof evidential recordings (‘whatwas said?’ as opposed to ‘who saidit?’). Sometimes the task is verygeneral and comprehensive andinvolves the transcription of anentire recording. Many poorquality recordings are initiallysubmitted for enhancement, i.e.digital sound processing toremove noise interference orraise the level of the conversationrelative to background sound.Police officers and lawyers oftenhave very high expectations ofenhancement technology (we’reback to CSI again!). However, inreality, the improvements it canbring to speech intelligibility aregenerally rather limited. Ondiscovering this, the instructingparty will often ask that atranscript is prepared by theforensic speech scientist, who hasadvantages over the layperson.<strong>Fi</strong>rst, s/he can make a study fromthe clearer areas of the recordingof the pronunciation patterns ofthe people involved. This mayassist with resolving what wassaid in the less clear areas.Second, s/he has available highquality replay and listeningfacilities. <strong>The</strong> speech analysissoftware from which thematerial is played back allows thetranscriber to delineate and‘zoom in’ on small sections ofspeech – single words, syllables orjust individual consonants andvowels – for multiple repetition.Third, s/he has time andpatience, the importance ofwhich cannot be underestimated.For a good, clear qualityrecording (which we would beunlikely to be asked totranscribe) one can estimate aratio of 8:1 transcription time torecording time, i.e. one minute ofspeech will take eight minutes totranscribe. For the poorestquality recordings we are askedto deal with, the ratio may be ashigh as 180:1. This is not work forthose who need high levels ofstimulation.In other cases, thedetermination of content ismuch more localised and highlyfocussed. This task is referredto as ‘questioned’ or ‘disputedutterance’ analysis. Here oneis examining perhaps just anunclear phrase or even a singleword, which potentially hashigh evidential significance forthe case. It may be subject tocompeting interpretations byprosecution and defence. Pastcases of this kind include oneinvolving a covertly recordedconsultation of a doctor whohad a heavy Greek accent. <strong>The</strong>issue was whether he said to adrug addict to whom he wasprescribing synthetic codeinetablets ‘you can inject thosethings’ or ‘you can’t inject thosethings’. In another case, a speakerof Urdu/Punjabi accentedEnglish had been interviewedby police on tape about theunexpected death of his gaylover. He initially insisted that nosexual activity had taken placebetween them immediately priorto the death (the police fearedsado-masochistic activitiesthat may have gone too far) butthen, at a later point, appearedto say that the man had gone tosleep and died after ‘wank off’.If correct, this signalled a highlysignificant change of story. Wewere asked to verify this hearingof the words. At first it appearedcorrect, but after very close anddetailed analysis they transpiredto be ‘one cough’, and thereforeof no evidential significanceat all. In cases such as theseone seeks clear and relevantreference speech from the personconcerned. This is analysedphonetically and acoustically toestablish, for example, how theypronounce particular vowels14<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Feature Forensic linguisticsLouisa Stevens and Professor Peter Frenchand consonants. <strong>The</strong> patternsfound are brought to bear ininterpreting the questionedutterance and determiningwhich of the competingalternative hearings is likely to becorrect.Not all the work involvesrecorded speech. In a minority ofcases we are asked to evaluate theearwitness evidence of lay people.<strong>The</strong>se may involve crimes wherethe witness or victim did notseen the perpetrator’s face butclaims to have recognised him/her by voice. Masked robberiesand rapes are cases in point. Herethe work involves assisting thepolice with setting up a voiceline-up, the auditory equivalentof a visual identification parade,which must be constructed inaccordance with Home Officeguidelines. In other cases,it may involve establishingwhether a witness’s claim to haverecognised a voice is a realisticone, given the prevailing acousticconditions (e.g. echoey subwaywith traffic passing overhead),and in the light of what is knownfrom relevant experimentalresearch studies. It may alsoinvolve carrying out soundpropagation tests at a crime scenein order to asses the credibility ofa witness’s claim to have heard arelevant event (‘Could Mrs X inher sitting room have heard thewords she claims to have heardscreamed through the wall fromthe flat next door?’).<strong>Fi</strong>nally, one has toremember that the examinationsand testing, whatever theirnature, are only part of the job.<strong>The</strong> other part involves goingto court to give expert evidence.This happens in around 5% of thecases in which one acts, and theskills required are very differentfrom the lab-based ones. Oneneeds to be able to express in aclear way – and without cuttingtoo many corners – what areoften highly complex linguisticand acoustic findings to a panelof jurors who have had noprevious exposure to the subjects.We shall always remember asenior forensic scientist who,when asked about where he haddeveloped his renowned skillsat communicating with juries,replied that it was during hisexperience in a previous career.He had been a schoolteacher. <strong>Fi</strong>nd out moreForensic speech science is one branch of the widerarea of forensic linguistics. <strong>Fi</strong>nd out more aboutthese areas through the following resources:BooksForensic Phonetics by John Baldwin and PeterFrench (Pinter, 1990)<strong>The</strong> Routledge Handbook of Forensic <strong>Linguistics</strong>edited by Malcolm Coulthard and Alison Johnson(Routledge, 2010)Online<strong>The</strong> website of J P French Associates is atwww.jpfrench.com<strong>The</strong> website of the University of York’s forensicspeech science research group (linked to J P FrenchAssociates) includes details of numerous researchprojects: www.york.ac.uk/<strong>language</strong>/research/forensic-speechDetails of the University of York’s MSc course inforensic speech science can be found atwww.york.ac.uk/<strong>language</strong>/prospective/postgraduate/taught/forensic-speech-scienceVisit the website of the International Associationfor Forensic Phonetics and Acoustics to find outmore about this subject: www.iafpa.net/index.htmAston University’s Centre for Forensic <strong>Linguistics</strong>combines research and investigative practiceas well as offering training courses in forensiclinguistic analysis: www.forensiclinguistics.netWatch Dr Tim Grant (Aston University) talk aboutforensic linguistics generally:www.youtube.com/watch?v=Foqk1uJz31IProfessor Peter French is Chairman of JP French AssociatesForensic Speech and Acoustics Laboratory, York, andHonorary Professor in the Department of <strong>Language</strong>and Linguistic <strong>Sci</strong>ence at the University of York wherehe undertakes postgraduate teaching and supervisesPhD research. He has analysed recordings in more than5,000 police investigations and legal cases from countriesthroughout the world.Email: jpf@jpfrench.comLouisa Stevens is a Director of JP French Associates ForensicSpeech and Acoustics Laboratory, York, and a TeachingFellow in the Department of <strong>Language</strong> and Linguistic<strong>Sci</strong>ence at the University of York where she lectures on theMSc course in Forensic Speech <strong>Sci</strong>ence. She undertakesresearch on anatomical, perceptual and acoustic aspects ofvoice quality and appears as an expert witness on voice andspeech matters in major criminal trials.Email: lcs@jpfrench.com<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 15

Feature <strong>The</strong> two faces of the dragonPoliteness in everyday terms can be assimple as holding a door open for someoneor saying ‘please’ and ‘thank you’. But inlinguistics the term ’politeness’ refers tothe <strong>language</strong> techniques involved inmaintaining relationships,achieving goals and conveyingand negotiating identity.Here, Dániel Z. Kádárdiscusses and challengesthe common view thatpoliteness practices inChinese are different fromthe strategies used in other<strong>language</strong>s.Politeness in ChinesePoliteness in East Asiaby Dániel Z. Kádárand Sara Mills.Althoughlinguisticpoliteness itselfis a source ofambiguity,perhaps oneof the most confusing areaswithin the field of politenessresearch is linguistic politenessin Chinese. When foreignersstudy the Chinese <strong>language</strong>they often find themselves in asomewhat awkward situationas the Chinese are represented,and often represent themselves,in two entirely differentstereotypical ways: either‘traditionally polite’ or ‘direct andpragmatic’. And there is a certaintruth behind this stereotype.In certain contexts the Chineseapply self-denigrating and otherelevatinghonorific expressions(see box), which look akin tothe more renowned Japanesehonorifics, as well as stronglyritualised and formal <strong>language</strong>.However, in the vast majority ofeveryday interactions ChineseWhen Obama hosted HuJintao in 2011, he bowedsolemnly as he shookhands with the leader ofthe Chinese State. <strong>The</strong> USPresident probably imaginedthat he was being progressiveby accommodating himselfto what he imagined as‘traditionally Chinese’behaviour, but he hadblundered badly.<strong>language</strong> usage is not onlyvoid of old-fashioned honorificexpressions and other traditionalforms, which might be familiarto many readers from historicaland martial art films, but alsolacks communication strategiesthat westerners would defineas the basic norms of politenessbehaviour. In a restaurant,especially when one is part of agroup of guests who are frequentvisitors to the place, one is likelyto be served as royalty. But whenbuying food in the street, thevendor may resort to an abrupt“What do you want?”. And thisambiguity is not confined to nonnativespeakers: both foreignersand natives may be treated withextreme deference in certainsituations and practically ignoredas ‘faceless’ entities in others.While it is tempting to brushaside Chinese <strong>language</strong> usageas simply ‘exotic’, the increasingglobal importance of Chinameans that understandingChinese <strong>language</strong> usage andbehaviour is a must, especially16<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Feature <strong>The</strong> two faces of the dragonif one wants to avoid blunders of‘exoticising’ East Asian people, ashappened with the US President,Barack Obama recently.When Obama hosted HuJintao in 2011, he bowed solemnlyas he shook hands with theleader of the Chinese State. <strong>The</strong>US President probably imaginedthat he was being progressive byaccommodating himself to whathe imagined as ‘traditionallyChinese’ behaviour, but hehad blundered badly. Far fromfeeling flattered by Obama’shumble bow, the Chinese leaderis more likely to have felt ameasure of contempt because incontemporary Chinese culture, inthis specific setting where leadersrepresent the ‘faces’ of theirnations, a bow is potentially not asign of ‘neutral’ politeness but isa non-verbal communication ofweakness.So how can we give areliable picture of the twofaces of Dragon, withoutfalling into the trap of makingovergeneralisations? A recentresearch project by Yuling Panand I has revealed, that norms ofpoliteness – or normative ‘politic’behaviour as linguistic politenessresearchers would put it – donot apply to every interactionalcontext in Chinese society. Inorder to avoid representing theChinese in an exotic light, it isimportant to clarify that this isa tendency, which is subject togeographical and social variation,rather than being a rule. Perhapseven more importantly, it isnot so much the case that theChinese are polite in somecontexts and rude in others.Instead, as the analysis of a largeresearch database has revealed,there are at least two majortypes of normative behaviourin Chinese society. <strong>The</strong> firsttype can be described as themode of ‘deference’. <strong>The</strong> secondcan be labeled as a normative‘lack of politeness’ mode, whichis somewhat unusual froma western perspective. <strong>The</strong>lack of politeness in certainsettings should therefore notbe interpreted as a breach ofnorms. Such behavior is not‘impoliteness’, as we mightinitially think, for the simplereason that it is the norm.This duality originatesin an important gap betweenthe way in which ‘in-group’and ‘out-group’ relationshipsare traditionally perceived bymany Chinese. In-group (nei inChinese) settings necessitatethe observance of the norms of‘proper’ <strong>language</strong> usage becausein-group relationships arelasting ones in Chinese minds.As anthropological research hasillustrated, in Chinese societythe building of ‘networks’(guanxi) has prevalence overindividualism: obtaining alucrative job, getting into a goodschool or being elected into aleading role all tend to happenthrough networking abilitiesrather than on the basis of purelyindividual skills. Out-group (wai)contexts, on the other hand,do not usually necessitate anyattempt to form interpersonalrelationships, and consequently… it does not make much sense toapologise for stepping on someone’s footon a crowded bus in which everyone stepson each other’s feet.►<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 17

Feature <strong>The</strong> two faces of the dragonnormative politeness does notapply in such settings. This is notsurprising if one considers thelarge density of population, andconsequently the vast numberof out-group encounters, inChinese society. To illustratethis with a simple but authenticexample, it does not make muchsense to apologise for stepping onsomeone’s foot on a crowded busin which everyone steps on eachother’s feet.What makes the dualityof Chinese linguistic politenessand its lack even more complexfrom a western perspectiveis that even within in-grouprelationships, where the normsof polite <strong>language</strong> usage apply,these norms tend to differ fromtheir western counterparts. Inwestern cultures polite <strong>language</strong>usage is generally associated withthe value of equality. However,this is not the case in Chinesesociety, which traditionallyperceives human relationshipsas predominantly hierarchicalones. Because of this perception,in conversations in which thereis a power difference betweenthe interactants, the powerfulparty can usually afford to ignorepolite behaviour without beinginterpreted as ‘impolite’ in astrict sense.<strong>The</strong> two faces of the Dragonraise plenty of challenges forfuture research. Inquiries intoChinese politeness are not only<strong>Fi</strong>nd out moredifficult due to the large numberof native speakers of Chinese,but also because Chinesepoliteness and impoliteness arein a complex state of ideologicaland linguistic transition. Afterthe opening of the country inthe 1970s, the state ideologyof Communism has in recentdecades intermingled withrevived Neo-Confucian ideals,as well as contemporary westernideologies which have been‘imported’ into China. Thisideological mixture not onlyresults in a large social andgeographical diversity in theways in which individuals andgroups perceive ‘proper’ Chinesepoliteness, but also influencesactual <strong>language</strong> usage.<strong>The</strong> aim for future researchis to bring us closer to theintriguing (non-)polite aspectsof Chinese <strong>language</strong> use, hencemaking Chinese communicationmore understandable for thewestern spectator. Dániel Z. Kádár is Professor of English<strong>Language</strong> and <strong>Linguistics</strong> at theUniversity of Huddersfield. His recentresearch on East Asian politenessincludes the co-authored bookPoliteness in Historical and ContemporaryChinese (Continuum, 2011) and theedited volume Politeness in East Asia(Cambridge University Press, 2011).BooksPoliteness in Historical and Contemporary Chinese by Yuling Pan andDániel Z. Kádár (Continuum, 2011)Politeness in East Asia edited by Dániel Z. Kádár and Sara Mills(Cambridge University Press, 2011OnlineExplore the study of linguistic politeness through the website of theinternational Linguistic Politeness Research Group:http://research.shu.ac.uk/politenessHonorifics are words or expressions used toconvey esteem when addressing or referringto someone. <strong>The</strong>y can be as simple as ‘Mr’ or‘Mrs’ or as complex as ‘Your Imperial and RoyalMajesty’. In Monty Python’s ‘RefreshmentRoom at Bletchley’ sketch, the compère, KennyLust, <strong>goes</strong> somewhat overboard with thehonorifics when introducing the entertainmentfor the evening:You know, once in a while it is my pleasure, andmy privilege, to welcome here at the refreshmentroom, some of the truly great internationalartists of our time. And tonight we have one suchartist. Ladies and gentlemen, someone whomI’ve always personally admired, perhaps moredeeply, more strongly, more abjectly than everbefore. A man, well more than a man, a god, agreat god, whose personality is so totally andutterly wonderful my feeble words of welcomesound wretchedly and pathetically inadequate.Someone whose boots I would gladly lick cleanuntil holes wore through my tongue, a man whois so totally and utterly wonderful, that I wouldrather be sealed in a pit of my own filth, thandare tread on the same stage with him. Ladiesand gentlemen the incomparably superiorhuman being, Harry <strong>Fi</strong>nk!Honorifics work mainly by elevating thestatus of the person addressed (as in ‘MyRight Honorable Friend’) or by denigrating thestatus of the speaker (as in the Monty Pythonexample above). What is particularly interestingabout Chinese is that the honorific system issocially diverse. This means that, historically,a commoner would denigrate himself using adifferent honorific than a high ranking person.For example, a commoner might use xiaoren(‘this worthless person) while an officialmight use xiaoguan (‘this worthless official).And a Buddhist monk might choose pinseng(‘poor monk’). <strong>The</strong>se would not only indicatehumbleness but would also display the differentsocial ranks of their speakers. Because of this, inhistorical hierarchical Chinese communication,speakers could not use the honorific vocabularyof other social classes.18<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Feature Circles of EnglishCircles of EnglishAs the English<strong>language</strong>continues itsglobal spread,Marcus Bridleconsiders howthe norms ofEnglish areshifting.English is frequentlydescribed as aglobal <strong>language</strong>,but perhaps weshould use theplural ‘Englishes’rather than the singular noun. Ifyou travel from region to regionin the USA, UK and Australia,you can hear shifts in accentand changes in dialect which,whilst still being identifiablyEnglish, can sound like a foreign<strong>language</strong>. Now that Englishhas spread around the world,there are ever more varieties –Englishes – to be heard.One of the most influentialways of describing the globalspread of English was putforward in 1990 by Braj Kachru,now Jubilee Professor ofLiberal Arts and <strong>Sci</strong>ences at theUniversity of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Kachru’s modeldescribes the global developmentof English using a series of everexpanding concentric circles.<strong>The</strong> inner circle comprisesthose countries where Englishis the native <strong>language</strong> (ENL)and includes the UK, Australia,Canada, New Zealand and theUSA. <strong>The</strong>se countries map thespread of the original diasporasof English speakers, taking the<strong>language</strong> to new lands as a resultof an expanding British Empire.<strong>The</strong> inner circle is seen as ‘normproviding’,setting the boundariesof what counts as ‘English’. <strong>The</strong>reare, of course, variations inEnglish across these countries. Inthe USA, for example, you mightwell embarrass yourself if youturned up dressed as Supermanfor a party described as ‘fancydress’. Fancy dress in Americasimply means formal clothes –with underpants most definitelyunderneath the trousers. Andwhile we’re on the subject ofpants, in the UK, walking aroundwearing nothing else would mostlikely be greeted with gasps ofhorror. In America, where pantsare trousers, you have nothingto worry about. But despitesuch minor lexical and syntacticdifferences between thesevarieties there is, a large amountof overlap. British English andAmerican English are not nearlyas different as is often claimed.<strong>The</strong> second or outer circlecomprises those countries, likeNigeria, India and Singapore,where English is widely spoken asa second <strong>language</strong> (ESL). A quick<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 19►

Feature Circles of English<strong>The</strong> second or outer circlecomprises those countries, likeNigeria, India and Singapore,where English is widely spoken asa second <strong>language</strong> (ESL). A quickcross reference between a mapdated around 1920 and a list of ESLcountries shows that the majorityof these were once part of theBritain’s global empire.cross reference between a map dated around 1920and a list of ESL countries shows that the majorityof these were once part of Britain’s global empire.<strong>The</strong>se are the territories in which English wasintroduced as the official <strong>language</strong> by the rulingpowers of the time. In these ‘norm-developing’countries, non-native speakers adopted (or wereforced to adopt) English in order to becomeinvolved with the trade and infrastructure of thecolonies. <strong>The</strong>se are the countries where, today,English is firmly entrenched in the cultural,political and social systems of the nation. <strong>The</strong>reare upwards of 300 million ESL speakers and theymay soon outnumber ENL speakers. It is in thesecountries where English diverged and developed.It was a two way process: just as Standard BritishEnglish may have undergone several localmodifications in ESL countries, so was it enrichedby imported words – khaki, pajamas, bungalow,bogus, jumbo, okay and zebra – as well as bychanges in accent and syntax.<strong>Fi</strong>nally, there is the expanding circle. Thisis by far the largest of the three and currentlyincludes almost all the places which aren’t alreadyin the first two circles. <strong>The</strong>se are the EFL countries,the countries where English is a foreign <strong>language</strong>but is increasingly seen as essential not just forsurvival but also for prospering in the world village.Europe. Japan. South Korea. Latin America. <strong>The</strong>Middle East. North Africa. China. Up and downthese countries and continents, in cities and inremote villages, there are thousands of EFL classesin progress. As you read this article, someone,somewhere is getting to grips with English for thefirst time. <strong>The</strong>re are Chinese three years olds beingsent to ‘English Club’ before they have begun tocomprehend the basics of Mandarin. <strong>The</strong>re areKurdish scientists, statisticians and engineersdeveloping their English in order to begin thedevelopment of their newly autonomous nation.Somewhere in Tokyo, there is a salary man orwoman sitting, possibly against their will, in abusiness English class trying to prepare for an 18month branch management placement on theother side of the world. <strong>The</strong>re are more of theseexpanding circle English speakers than thereare of the inner and outer circles combined. A20<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

Feature Circles of Englishconservative estimate wouldplace the figure at about 1 billion.<strong>The</strong>se expanding circlecountries are described as ‘normdependent’, using the innerand outer circles to provide theso-called ‘correct’ models ofEnglish. From these circles therules are laid out, the text bookswritten and the teachers sent.It is from these countries thatthe pop music blares, the moviesroll and the advertising flashes.<strong>The</strong> expanding circle looks tothe inner and outer circles as itsframe of reference for what good,proper English is. At least, it did.Pants or trousers? In the US “pants” are what the UK would call “trousers”.Could the hip hop style of wearing low slung trousers revealing underwearbe making a linguistic as well as a fashion statement?<strong>The</strong> ‘norm’ as laid downby the inner and outer circlesis becoming increasingly lessnormal. <strong>The</strong> linguist H. G.Widdowson pointed to a latetwentieth century shift fromthe ‘distribution’ of English tothe ‘spread’. He saw the originaldistribution of the <strong>language</strong> asone which was controlled. <strong>The</strong>inner circle handed down Englishto the outer circle, insistingthat the grammar remaineduntampered with and the correctlexicon was studied slavishly.Marcus Bridleis a tutor in theEnglish <strong>Language</strong>Teaching Centreat the Universityof Sheffield anda PhD student atthe University ofHuddersfield. Hehas taught Englishin Spain and Japanand is currentlyresearching theapplication ofcorpus linguistictechniques in EFLteaching.‘Spread’, on theother hand, isuncontrolled. Itis English shapedby contact withdifferent cultures,<strong>language</strong>s and users.It is word of mouth,digital, of the moment.It is not the <strong>language</strong> of thetext book and is beyond thepedantic clutches of even themost zealous prescriptivist. AsEnglish spreads ever outwards,so the centre loses its controland we find the <strong>language</strong>multiplying into a range of‘Englishes’. <strong>The</strong>se are not creoleswith strictly developed rules, butimprovisations on a theme.Consider Japan. Here,Jenglish, or more properly Eigo-Wasei, has been developing fora long time. English words areborrowed and manipulated intothe Japanese <strong>language</strong>. <strong>The</strong>semutated loanwords are thenused by the Japanese when theycome to speak English. Japanesespeakers might say bed-town forsuburb, healthmeter for weighingscales, free-size meaning onesize fits all, and the particularlydescriptive new-half whendescribing a transexual. WhilstJenglish, Chinglish, Spanglishand the like are often the butt ofpejorative remarks, they work.<strong>The</strong>y have meaning for theirusers. Wrong as they might seemto those from the ‘inner circle’,they are adopted wholeheartedlyby the expanding circle and,these days, spread exponentially<strong>Fi</strong>nd out morethroughsocial medianetworks.Which English, then,should have authority in the EFLclassroom? Is EFL the guardianof some kind of ‘authenticity’in English? Should Japanesestudents be informed thatwhen they say baby car theyare wrong and that they mustuse pram instead? Surely, babycar is just as good, if not better?In the future, will the role ofthe English teacher be entirelyredundant as these divergentEnglishes harmonise into one,homogenous global English?Or will English teachers findthemselves in a classroommediating between a babbleof mutually unintelligibleEnglishes? Perhaps the future ofEnglish lies somewhere betweenthe two, where a convenientglobal standard is underpinnedby a range of local forms andwhere ‘Konglish’ and IndianEnglish have as much authorityas ‘norms’ as British andAmerican English. BooksWorld Englishes: A Resource Book for Students by Jennifer Jenkins(Routledge, 2009)<strong>The</strong> Alchemy of English: <strong>The</strong> Spread, Functions and Models of NonnativeEnglishes by Braj Kachru (University of Illinois Press, 1990)<strong>The</strong> Handbook of World Englishes edited by Braj Kachru, YamunaKachru and Cecil Nelson (Blackwell, 2009)<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 21

ReviewsReviewsFor me, themajor issuewith this bookis summed up inthe title. Despitewhat thedefinite articlesuggests, thereis no one ‘story’of the English<strong>language</strong>.<strong>The</strong> Story of English:How the English<strong>Language</strong> Conqueredthe Globeby Philip GoodenQuercus, 297 pages, RRP £8.99Dan McIntyre on a contentiousaccount of the history of EnglishAconventionalhistory ofEnglish <strong>goes</strong>something likethis: Germanicdialects broughtto the British Isles by the Angles,Saxons and Jutes are theninfluenced by the Scandinaviandialects spoken by the laterViking invaders. Followingthe Norman Conquest, thisfledgling English <strong>language</strong> isthen influenced by French, the<strong>language</strong> of the new nobility,and Latin, the <strong>language</strong> of thechurch. <strong>The</strong>re follows a periodduring which English declinesin prestige, only to rise again asa result of war with France andthe loss of Normandy. During the15th century, the <strong>language</strong> is thenfixed as a direct consequence ofthe introduction of the printingpress. Early Modern English, orthe <strong>language</strong> of Shakespeare,then becomes the basis of aneventual global English onceit is transferred to the NewWorld and beyond by Britishcolonists and Empire builders.In his 2005 book, <strong>The</strong> Stories ofEnglish, David Crystal beginswith this standard history beforeproceeding to demolish it onthe grounds that it is manifestlybiased in favour of Standardwritten English; by contrast,regional dialects and spoken<strong>language</strong> don’t get a look in.Given that Crystal’s book is oneof the few referenced in PhilipGooden’s <strong>The</strong> Story of English, itis surprising that Gooden sticksso rigidly to the conventionalhistory. <strong>The</strong> result is a fairlylacklustre retelling of thestandard series of events deemedto have affected the developmentof English. It is not so much thatGooden is wrong in what hesays, more that his inability tolook beyond the conventionalstory results in some grosssimplifications and misleadingimpressions. So, for instance,Middle English is covered inthe chapter called ‘Chaucer’sEnglish’ while Early ModernEnglish, predictably enough, isdealt with in a chapter called‘<strong>The</strong> Age of Shakespeare’. <strong>The</strong>setwo writers may well be themost famous exponents of theEnglish of their respective timesbut to describe Middle Englishand Early Modern English solelythrough their work gives a highlyincomplete picture of how the<strong>language</strong> was developing in theseperiods. To be fair, the chapter on‘Chaucer’s English’ does brieflycover the work of Caxton and theGawain poet. However, readingthe chapter on Shakespeare, onecould be forgiven for thinkingthat Early Modern English wasalmost entirely his creation.Elsewhere, Gooden suggeststhat the Norman Conquestwas the event that led to theintroduction of French intoEngland (it wasn’t: French hadbeen used in the Royal Courtduring the reign of Edward theConfessor). And when discussingEnglish overseas, Gooden givesthe highly misleading impressionthat there is a <strong>language</strong> varietycalled ‘Pidgin English’ thatwas then ‘spread around theworld’ (p.176). Perhaps the mostproblematic claim, though, isthat the pattern of English’sdevelopment over time hasbeen one of simplification.While it is true that English hasbecome a <strong>language</strong> where wordorder rather than inflections isresponsible for meaning, thisis a process of regularisation.Whether this means the<strong>language</strong> is becoming simpler isvery much a matter of point ofview. No doubt the Anglo-Saxonswould have seen this process verydifferently! For me, the majorissue with this book is summedup in the title. Despite what thedefinite article suggests, thereis no one ‘story’ of the English<strong>language</strong>. English is far toointeresting for that. Dan McIntyre is Professor of English<strong>Language</strong> and <strong>Linguistics</strong> at theUniversity of Huddersfield.22<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012

ReviewsHow to Talk Like aLocalby Susie DentArrow Books, 244 pages, RRP£7.99Ella Jeffries on a lively accountof contemporary variation inBritish English.Effective as areference bookor simply to flickthrough, How toTalk Like a Localis a collection anddescription of regional wordsand phrases that have been orstill are in use around the UKtoday. <strong>The</strong>se include words wemay consider to be old-fashioned,such as the endearment ‘chuck’,and also words that bear themarkings of a 21st century fadfor cultural phenomena such as‘chav’ (“a young person in trendyclothes and flashy jewellery”)and ‘minging’ (“ugly”). Howeverthe addition of some descriptionof the history and etymology ofthe words shows that even theapparently modern dialect wordshave been around longer thanwe think (‘chav’, derived from aRomany word, has been aroundfor over 150 years). I was struckby how many words I had notheard of throughout the book, atestimony to both the regionaldiversity evidently still existentand the depth of the researchthat has gone into the findingand choosing of these words.A useful feature of this book isfound in the links between thewords which mean roughly thesame thing in different dialects;underneath each word is a listof other similar regional wordswhich can in turn be lookedup in the book. Also, scatteredthroughout are lengthierdescriptions of some commonslang names for processes, suchas the many different ways teamaking, brewing and pouringare described throughout Britain(‘brew’, ‘wet’, ‘steep’, ‘mash’, ‘teem’,‘bide and draw’). <strong>The</strong>re are alsolonger descriptions of some ofthe specific phonetic features ofcertain accents, with two-pagesections on ‘How to talk like a…’ which ranges from Cockneyto Geordie to Scot (being fromYorkshire I felt a section onthis region was lacking!). <strong>The</strong>sesections are user-friendly fornon-specialists, providingsounded out letter examples ofthe way in which we distinguishthese accents and they includesome words and phrases specificto the region.This book explores anduncovers the dialect variationthat some people believe is dyingout but is evidently still in usethroughout the UK. Personally Iwas particularly drawn to wordsfrom my native Yorkshire andfound some that I have neverheard before (e.g. ‘gobslotch’; anidle fellow), words that I hadn’tpreviously known were dialectspecific (e.g. ‘ginnel’; alleyway)and words that I recognise butwhose meanings I wouldn’thave been able to pin down(e.g. ‘blethered’; tired out). Inthe introduction to the bookthe point is nicely made thatalthough many words have diedout, the constantly changing<strong>language</strong> reflects the constantdevelopment of lifestyle andsociety over the years. With thissentiment in mind, I expectedmore terms reflecting youngpeople’s interests and concerns.In order to reflect the diversityand constant development of<strong>language</strong>, it would have beenuseful to document some ofthose words currently in voguetoday which may well becomeestablished dialect words infuture. In a similar vein (this maybe the sociolinguist in me), somereference to which particularages/sexes/social groups usethese words would have made aninteresting addition. Ella Jeffries is a PhD student studyingsociophonetics at the University of York.In order toreflect thediversity andconstantdevelopmentof <strong>language</strong>,it would havebeen useful todocument someof those wordscurrently invogue todaywhich maywell becomeestablisheddialect words infuture.<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012 23

Ludic <strong>Linguistics</strong><strong>The</strong> <strong>Linguistics</strong> OlympiadSuffering withdrawal symptoms from London 2012?<strong>The</strong>n why not try a different kind of Olympics? <strong>The</strong><strong>Linguistics</strong> Olympiad movement has branches aroundthe world and also holds an international Olympiadeach year: you can find out more atwww.ioling.org. <strong>The</strong> puzzles set for these competitionsprovide fascinating examples of the combination oflogic and linguistic sensitivity that are required to besuccessful as a linguist. Here’s one that comes from theFoundation Level test of the UK’s Olympiad in 2012:Mwamni sileng.Nutsu mwatbo mwamni sileng.Nutsu mwegau.Nutsu mwatbo mwegalgal.Mworob mwabma.Mwerava Mabontare mwisib.Mabontare mwisib.Mweselkani tela mwesak.Mwelebte sileng mwabma.Mabontare mworob mwesak.Sileng mworob.Now, after that crash course, translate the followingsentences into Abma:1. <strong>The</strong> teacher carries the water down.2. <strong>The</strong> child keeps eating.3. Mabontare eats taro.4. <strong>The</strong> child crawls here.5. <strong>The</strong> teacher walks downhill.6. <strong>The</strong> palm-tree keeps growing upwards.7. He <strong>goes</strong> up.Say it in AbmaAbma is an Austronesian <strong>language</strong> spoken in parts ofthe South Pacific island nation of Vanuatu by around8,000 people. Carefully study these Abma sentencesthen answer the questions below. Note that thereis no separate word for ‘the’ or ‘he’ in these Abmasentences:Here are some new words in Abma: sesesrakan(teacher), mwegani (eat), bwet (taro, a kind of sweetpotato), muhural (walk), butsukul (palm-tree).He drinks water.<strong>The</strong> child keeps drinking water.<strong>The</strong> child grows.<strong>The</strong> child keeps crawling.He runs here.He pulls Mabontare down.Mabontare <strong>goes</strong> down.He carries the axe up.He brings water.Mabontare runs up.<strong>The</strong> water runs.Done it? Now try translating these Abma sentencesinto English:8. Sesesrakan mweselkani bwet mwabma.9. Sileng mworob mwisib.10. Mwelebte bwet mwesak.Easy? Check your answers on page 25 oppoosite.24<strong>Babel</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Language</strong> Magazine | November 2012