LABOULBENIALES - Agentschap voor Natuur en Bos

LABOULBENIALES - Agentschap voor Natuur en Bos

LABOULBENIALES - Agentschap voor Natuur en Bos

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

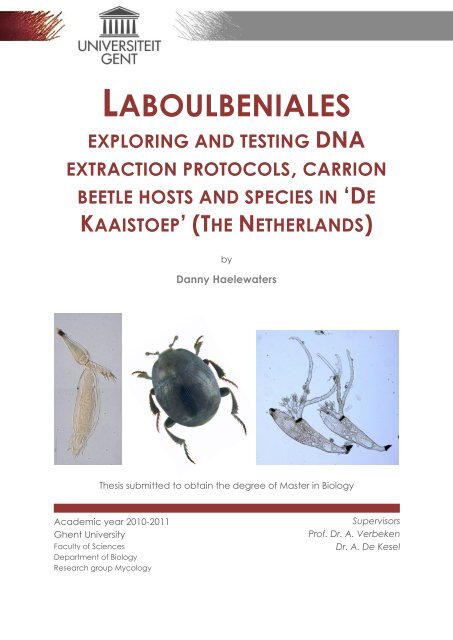

<strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>EXPLORING AND TESTING DNAEXTRACTION PROTOCOLS, CARRIONBEETLE HOSTS AND SPECIES IN „DEKAAISTOEP‟ (THE NETHERLANDS)byDanny Haelewaters© February 2011, Faculty of Sci<strong>en</strong>ces – Research group MycologyAll rights reserved. This master thesis contains confid<strong>en</strong>tial information andconfid<strong>en</strong>tial research results that are property to the UG<strong>en</strong>t. The cont<strong>en</strong>ts ofthis master thesis may under no circumstances be made public, nor completeor partial, without the explicit and preceding permission of the UG<strong>en</strong>trepres<strong>en</strong>tative, i.e. the supervisor. The thesis may under no circumstances becopied or duplicated in any form, unless permission granted in writt<strong>en</strong> form.Any violation of the confid<strong>en</strong>tial nature of this thesis may impose irreparabledamage to the UG<strong>en</strong>t. In case of a dispute that may arise within the contextof this declaration, the Judicial Court of G<strong>en</strong>t only is compet<strong>en</strong>t to be notified.Pictures front page: (from left to right) Hesperomyces viresc<strong>en</strong>s from Harmoniaaxyridis (specim<strong>en</strong> 1c, thallus 1) collected in „De Kaaistoep‟ (Tilburg, TheNetherlands), new for the mycoflora of The Netherlands; picture by DannyHaelewaters (2010). Carrion beetle Saprinus semistriatus; picture by UdoSchmidt (2008). Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata from Agonum assimile (specim<strong>en</strong> DH4,thalli G and H) collected at Schellandpolderdijk (Hing<strong>en</strong>e, Belgium); picture byDanny Haelewaters (2009).

PART II<strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>: EXPLORING AND TESTINGDNA EXTRACTION PROTOCOLS311. INTRODUCTION 321.1. DIFFICULTIES FOR DNA EXTRACTION OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> 321.2. GENBANK 321.2.1. THE GENBANK SEQUENCE DATABASE 321.2.2. THE SEARCH FOR SEQUENCES OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>/LABOULBENIOMYCETES INGENBANK 322. MATERIALS & METHODS 342.1. FUNGUS, HOST AND ORIGIN 342.2. MORPHOLOGICAL PROTOCOL AND DNA EXTRACTION 342.2.1. INTRODUCTION 342.2.2. PROTOCOL I (BASED ON WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001b) 342.2.3. PROTOCOL II (BASED ON WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001a) 352.2.4. PROTOCOL III: PUREGENE KIT A 352.2.5. PROTOCOL IV: DNEASY EXTRACTION KIT 352.2.6. PROTOCOL V: DIRECT PCR 362.3. PCR AMPLIFICATION 362.3.1. ITS 362.3.2. POST PCR 372.4. SEQUENCING AND SEQUENCE ANALYSIS 372.4.1 SEQUENCING 372.4.2 SEQUENCE ANALYSIS 373. RESULTS 393.1. DNA EXTRACTION 393.2. AMPLIFICATION 393.2.1. PRIMER PAIR ITS5/ITS4-A 393.2.2. PRIMER PAIR ITS5/ITS2 404. DISCUSSION 415. CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS 44PART III<strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> OF CARRION BEETLES:A PRELIMINARY STUDY451. INTRODUCTION 461.1. FORENSIC ENTOMOLOGY 461.2. ANIMAL CADAVERS 461.2.1. SOURCES OF BIODIVERSITY 461.2.2. THE „ROTTING‟ OF A CADAVER 461.2.2.1. The fresh stage 471.2.2.2. The bloat stage 471.2.2.3. The early decomposition 47P a g e | 2

PART IVPRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> IN„DE KAAISTOEP‟771. INTRODUCTION 781.1. NATURAL LANDSCAPE DE KAAISTOEP 781.1.1. DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE 781.1.2. BIODIVERSITY IN DE KAAISTOEP 781.1.2.1. Plants and fungi in De Kaaistoep 791.1.2.2. Animals in De Kaaistoep 791.2. <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> IN THE NETHERLANDS 791.2.1. CONTRIBUTIONS OF MIDDELHOEK 791.2.2. CONTRIBUTIONS OF BOEDIJN 812. MATERIALS & METHODS 822.1. HOSTS 822.1.1. COLLECTION OF HOSTS 822.1.1.1. Pitfall traps 822.1.1.2. Window traps 822.1.1.3. Bands and rings 822.1.1.4. Malaise trap 832.1.1.5. Light traps 832.1.2. IDENTIFICATION OF HOSTS 832.2. <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> 832.2.1. SCREENING FOR AND IMBEDDING OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> 832.2.2. IDENTIFICATION OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> 842.3. PRESENTING RESULTS 843. RESULTS 863.1. PARASITE-HOST LIST 863.2. HOST- PARASITE LIST 864. DESCRIPTION OF THE SPECIES AND DISCUSSIONS 874.1. LABOULBENIA CALATHI T. MAJEWSKI 874.2. LABOULBENIA EUBRADYCELLI HULDÉN 884.3. LABOULBENIA PEDICELLATA THAXT. 894.4. LABOULBENIA VULGARIS PEYR. 914.5. HAPLOMYCES TEXANUS THAXT. 924.6. HESPEROMYCES VIRESCENS THAXT. 934.7. RHACHOMYCES LASIOPHORUS (THAXT.) THAXT. 944.8. STICHOMYCES CONOSOMATIS THAXT. 954.9. STIGMATOMYCES MAJEWSKII H.L. DAINAT, MANIER & BALAZUC 965. CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS 98PART VREFERENCES99P a g e | 4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe work pres<strong>en</strong>ted in this master thesis is the result of many years of biologicalinterest, not just the few that constituted my studies.I am very grateful to my supervisor, Annemieke Verbek<strong>en</strong>, for what she hastaught me throughout my studies. Her <strong>en</strong>thusiasm and interest for mycologyplayed a huge role in me choosing my study path. Her expertise andknowledge have taught me more than I could ever have expected.I would also like to thank my second supervisor, André De Kesel, for teachingme all about the fascinating Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales. His passion has inspired me tofinish this work and ev<strong>en</strong> start new chapters.My thanks go out to Paul Van Wielink and <strong>Natuur</strong>museum Brabant (Tilburg) forgiving me the chance to work in a group of professional <strong>en</strong>tomologists. Theid<strong>en</strong>tification of carrion beetles would not have be<strong>en</strong> so pleasant at any otherplace. Special thanks for involving me in the project of „De Kaaistoep‟.I wish to thank Dirk Raes (<strong>Ag<strong>en</strong>tschap</strong> <strong>voor</strong> <strong>Natuur</strong> <strong>en</strong> <strong>Bos</strong>) and Yves Braet andSofie Vanpoucke (National Institue for Criminalistics and Criminology) forinvolving me in the project Dood doet Lev<strong>en</strong> and for the possibility to work atthe laboratories of the National Institute for Criminalistics and Criminology.I have to thank Jorinde Nuytinck, Kobeke Van de Putte, Luc Crêvecoeur, MarcDelbol, Jan Willem van Zuijl<strong>en</strong>, Hans Huijbregts, Pedro Crous, Walter Rossi andMeredith Blackwell for sharing their expertise with me. More than once, onlysmall issues were bothering me. However, without their help I was naught.I cannot forget my fri<strong>en</strong>ds who have supported me throughout difficult times,who were always there wh<strong>en</strong> I needed a word. Special thanks to Stev<strong>en</strong>“Sev<strong>en</strong>less” Haes<strong>en</strong>donckx (doing my very best to see you becoming doctor),Evelyn Theuninck (we will meet again in Chantemerle-lès-Grignan), LiesbethVerlind<strong>en</strong> (for some Mazurka distraction), Lindsay De Decker (loving you, in anasexual way, although… ^^), Frederik Byttebier (you gave me inspiration and –rec<strong>en</strong>tly – a new dream to live for), Annemieke Krammer (dreaming aboutcandles, reincarnation, and lots – LOTS – of paper), Merel Van D<strong>en</strong> Broucke(my best witch fri<strong>en</strong>d), Eveli<strong>en</strong> De Wilde (for giving me a home) and all fri<strong>en</strong>dsof the G<strong>en</strong>tse Biologische Kring (I will never forget you).I will always be indebted to my par<strong>en</strong>ts, who have supported me at all times.Thanks dad;-) And mum, I hope that – wherever you are – you can be proud.Your belief in me, ev<strong>en</strong> now, was the outstanding factor always helping me toget through.P a g e | 5

SAMENVATTINGINLEIDINGLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales zijn obligaat ectoparasitaire ascomycet<strong>en</strong> die <strong>voor</strong>kom<strong>en</strong> opArthropoda, meestal insect<strong>en</strong>. Er zijn meer dan 2000 soort<strong>en</strong> beschrev<strong>en</strong> in141 g<strong>en</strong>era. Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales hebb<strong>en</strong> ge<strong>en</strong> mycelium; ze vorm<strong>en</strong> kleine thalli,opgebouwd uit e<strong>en</strong> receptaculum met perithecia, aanhangsels <strong>en</strong> antheridia.Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales zijn gastheerspecifiek. Het parasiter<strong>en</strong> van e<strong>en</strong> bepaaldegastheersoort is afhankelijk van zowel de eig<strong>en</strong>schapp<strong>en</strong> van het integum<strong>en</strong>t,het microklimaat ter hoogte van het oppervlak van de gastheer <strong>en</strong> debeschikbaarheid van nutriënt<strong>en</strong> als de eig<strong>en</strong> <strong>voor</strong>keur<strong>en</strong> <strong>voor</strong> e<strong>en</strong> bepaaldmilieu. Er zijn ge<strong>en</strong> vrijlev<strong>en</strong>de lev<strong>en</strong>sstadia. Enkel seksuele reproductie isgek<strong>en</strong>d. Aandacht wordt besteed aan de morfologie, de classificatie <strong>en</strong> deecologie, met bijzondere aandacht <strong>voor</strong> de verschill<strong>en</strong>de vorm<strong>en</strong> vanspecificiteit van Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales.BESTUDEERDE ONDERWERPEN EN CONCLUSIESSpecies-gerelateerde taxonomische problem<strong>en</strong> bij Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales kunn<strong>en</strong><strong>en</strong>kel sluit<strong>en</strong>d bestudeerd word<strong>en</strong> door het combiner<strong>en</strong> van klassiekemorfologische method<strong>en</strong> <strong>en</strong> moleculaire protocoll<strong>en</strong>. Vier DNAextractieprotocoll<strong>en</strong>werd<strong>en</strong> getest; WEIR & BLACKWELL (2001a) <strong>en</strong> WEIR &BLACKWELL (2001b) vormd<strong>en</strong> de basis <strong>voor</strong> twee protocoll<strong>en</strong>, de ander<strong>en</strong> war<strong>en</strong>gebaseerd op de Qiag<strong>en</strong> Pureg<strong>en</strong>e Kit A <strong>en</strong> de Qiag<strong>en</strong> Dneasy Plant Mini Kit.Bij het vijfde extractieprotocol werd<strong>en</strong> thalli zonder <strong>en</strong>ige modificatiegeamplificeerd.Er werd<strong>en</strong> ge<strong>en</strong> sequ<strong>en</strong>ties van Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales gevond<strong>en</strong>; we kreg<strong>en</strong> <strong>en</strong>kel temak<strong>en</strong> met contaminant<strong>en</strong> uit verschill<strong>en</strong>de klass<strong>en</strong>. Één contaminant waszelfs e<strong>en</strong> basidiomyceet. Op basis van deze resultat<strong>en</strong> kan word<strong>en</strong>geconcludeerd dat de beschrijving<strong>en</strong> in de reeds vermelde refer<strong>en</strong>ties (WEIR &BLACKWELL 2001a, 2001b) volledig noch betrouwbaar zijn.Suggesties <strong>voor</strong> verder onderzoek word<strong>en</strong> gegev<strong>en</strong>.Gericht onderzoek naar Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales op kadaverkevers werd tot op hed<strong>en</strong>nog niet verricht. In dit werk werd<strong>en</strong> in het Zoniënwoud (België) kevers(Coleoptera) bemonsterd in de directe omgeving van kadavers; dit gebeurdein het kader van het project Dood doet Lev<strong>en</strong> (<strong>Ag<strong>en</strong>tschap</strong> <strong>voor</strong> <strong>Natuur</strong> <strong>en</strong><strong>Bos</strong>). Additioneel materiaal werd bezorgd door het Nationaal Instituut <strong>voor</strong>Criminalistiek <strong>en</strong> Criminologie. Alle kevers werd<strong>en</strong> geïd<strong>en</strong>tificeerd <strong>en</strong>gescre<strong>en</strong>d op de aanwezigheid van Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales.In deze studie werd<strong>en</strong> ge<strong>en</strong> Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales gevond<strong>en</strong>. Mogelijkerwijs hebb<strong>en</strong>Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales door hun eig<strong>en</strong> milieu<strong>voor</strong>keur<strong>en</strong> moeilijkhed<strong>en</strong> om zich opkadaverkevers te ontwikkel<strong>en</strong>. Kadaverkevers beschikk<strong>en</strong> namelijk oververschill<strong>en</strong>de soort<strong>en</strong> habitats.P a g e | 6

Voorlopig is Asaphomyces tubanticus (Middelh. & Boel<strong>en</strong>s) Scheloske de <strong>en</strong>igebek<strong>en</strong>de soort van Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales die systematisch <strong>voor</strong>komt opkadaverkevers. Deze soort werd al waarg<strong>en</strong>om<strong>en</strong> in België (RAMMELOO, 1986;DE KESEL & RAMMELOO, 1992; DE KESEL, 1997). Rhadinomyces pallidus Thaxt. werdook reeds geobserveerd op kadaverkevers (MAJEWSKI, 2003), maar is nog nietbek<strong>en</strong>d in België.Suggesties <strong>voor</strong> verder onderzoek word<strong>en</strong> gegev<strong>en</strong>.In Nederland is er sinds de jar<strong>en</strong> ‟40 (BOEDIJN, 1923; MIDDELHOEK, 1941, 1942,1943a, 1943b, 1943c, 1943d, 1945, 1947a, 1947b, 1949) ge<strong>en</strong> onderzoek meerverricht naar Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales. „De Kaaistoep‟ wordt beschouwd als e<strong>en</strong>hotspot van biodiversiteit in Nederland <strong>en</strong> le<strong>en</strong>t zich dan ook uitstek<strong>en</strong>d <strong>voor</strong>gericht onderzoek naar Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales. In dit werk werd<strong>en</strong> insect<strong>en</strong> uit decollectie van het <strong>Natuur</strong>museum Brabant (Tilburg, Nederland), verzameld inDe Kaaistoep, gescre<strong>en</strong>d op de aanwezigheid van Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales.Deze bijdrage resulteerde in neg<strong>en</strong> soort<strong>en</strong> Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales, waarvan zessoort<strong>en</strong> nieuw zijn <strong>voor</strong> Nederland. Het gaat om Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia calathi T.Majewski, Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia eubradicelli Huldén, Hesperomyces viresc<strong>en</strong>s Thaxt.,Rhachomyces lasiophorus (Thaxt.) Thaxt., Stichomyces conosomatis Thaxt. <strong>en</strong>Stigmatomyces majewskii H.L. Dainat, Manier & Balazuc.We verwacht<strong>en</strong> dat er nog meer nieuwe soort<strong>en</strong> <strong>voor</strong> Nederland zull<strong>en</strong>word<strong>en</strong> ontdekt in De Kaaistoep, naarmate het onderzoek zich meer opLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales zal richt<strong>en</strong>.P a g e | 7

PART IGENERAL INTRODUCTIONTHESIS OUTLINEAIMSP a g e | 8

1. <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>1.1. DEFINITION OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales include over 2000 species in 141 g<strong>en</strong>era (SANTAMARIA, 1998; KIRKet al., 2001; WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2005) of obligate, ectoparasitic fungi, which liveassociated with arthropods, mostly true insects. Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales have nomycelium; their thalli are small and of determinate growth, bearing antheridiaand perithecia on a receptacle with app<strong>en</strong>dages (TAVARES, 1985). Only sexualstages are known. Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales are host-specific (THAXTER, 1896; SCHELOSKE,1969; TAVARES, 1985; MAJEWSKI, 1994; DE KESEL, 1996, 1997).The knowledge on Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales is rather rec<strong>en</strong>t and has increased slowly.Large parts of their biodiversity are still unknown and many questions stillunresolved.1.2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDIn the 1840s, two Fr<strong>en</strong>ch <strong>en</strong>tomologists, Joseph Alexandre Laboulbéne andAuguste Rouget, did the earliest observations on Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales resulting in afirst publication on the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales (ROUGET, 1850, ref. in TAVARES, 1985). Atfirst, the structures on Brachinus (Coleoptera, Carabidae) were thought to besupernumerary ant<strong>en</strong>nal segm<strong>en</strong>ts. ROUGET (1850, ref. in TAVARES, 1985)suggested that they were living organisms. The recognition as fungi came in1852 and the g<strong>en</strong>us Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia was raised within the Pyr<strong>en</strong>omycetes – anext<strong>en</strong>sive group of Ascomycetes (ROBIN, 1853). Later on, specim<strong>en</strong>s onwingless dipteran parasites of bats were still mistak<strong>en</strong>ly described asArthrorhynchus, an acanthocephalan worm, by KOLENATI (1857).MAYR (1853) thought that the „hairlike structures‟ on Nebria (Coleoptera,Carabidae) were chitinous. Suggesting that they were outgrowths of theinsect‟s integum<strong>en</strong>t, he noticed differ<strong>en</strong>ces betwe<strong>en</strong> those structures onyounger and older beetles. On older individuals, there was always a variableswelling on the hair, whereas no such swelling was pres<strong>en</strong>t on the hair ofyounger beetles.PEYRITSCH (1871) made ext<strong>en</strong>sive observations on the structure anddevelopm<strong>en</strong>t of the housefly Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia (L. muscae Peyr.). PEYRITSCH (1871)redescribed Arthrorhynchus as Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia nycteribiae Peyr. He laterestablished the family Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae in the Ascomycetes (PEYRITSCH, 1873)and laid a solid foundation for our understanding of the biology ofLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales (PEYRITSCH, 1875), based on observations of laboratory coloniesof houseflies and studies of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales in the field.A systematic study of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae was begun by Roland Thaxter in1890, wh<strong>en</strong> he published his first in a series of papers describing hundreds ofnew species. In 1896, THAXTER‟S first monographic volume on theLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae appeared. It was particularly a summary upon all previouswork (TAVARES, 1985). The monograph of Thaxter – five volumes, published in1896, 1908, 1924, 1926 and 1931 – constituted the basis for later studies of thegroup. Unfortunately Thaxter died only one year after the publication of theP a g e | 9

fifth volume, therefore the sixth volume – which was meant to be a synthesis –was never prepared. More than 40 years study resulted in the description of103 g<strong>en</strong>era, approximately 1260 species and 13 varieties (BENJAMIN, 1971). Upto now, about two thirds of all the known species have be<strong>en</strong> described byThaxter (HULDÉN, 1983).THAXTER (1896) first separated the family of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae into two„groups‟ (Table I below): the Endog<strong>en</strong>ae and the Exog<strong>en</strong>ae (based on thedevelopm<strong>en</strong>t of spermatia in the antheridia). The Endog<strong>en</strong>ae included twoorders: the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ieae (with simple antheridia; 15 g<strong>en</strong>era) and thePeyritschielleae (with compound antheridia; 11 g<strong>en</strong>era). Those orders wouldcorrespond to tribes in modern classification systems. In the second volumeTHAXTER (1908) replaced the terms Endog<strong>en</strong>ae and Exog<strong>en</strong>ae by the subordinalnames Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iinae and Ceratomycetinae (Table I below); the majorsubdivisions from the former group Endog<strong>en</strong>ae were substituted by families,Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae and Peyritschiellaceae. Thaxter did not recognize aseparate family within the Ceratomycetinae. The name Ceratomycetaceae –now universally accepted – first has be<strong>en</strong> introduced by MAIRE in 1916.Volume I Family Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceaeTable I: Classification in Thaxter‟s monographs I and II„Group‟ Endog<strong>en</strong>ae Exog<strong>en</strong>aeOrder Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ieae PeyritschielleaeVolume II Order Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ialesSuborder Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iinae CeratomycetinaeFamily Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae PeyritschiellaceaeP a g e | 10After Thaxter‟s death in 1932, various authors contributed to the knowledge bypublishing some short papers and/or describing new species and g<strong>en</strong>era:Spegazzini, Picard, Maire, Chatton, Cépède, Giard and Istvánffi. The majorityof the numerous publications that have appeared were regional studies,collection reports and rather short (TAVARES, 1985; DE KESEL, 1997). However,wh<strong>en</strong> considered together, they have added ext<strong>en</strong>sive data on thedistribution of these fungi.Some researchers suggested a relationship betwe<strong>en</strong> red algae andLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales and thought that Dikaryomycota derived from red algae, withthe Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales as an intermediate step KARSTEN, 1869; SACHS, 1874). Sexualreproductive structures, including a highly differ<strong>en</strong>tiated trichogyne and theabs<strong>en</strong>ce of mycelium, are unusual ascomycete characteristics andsuperficially resemble floridean algal features (BLACKWELL, 1994). CÉPÈDE (1914)believed the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales as a whole occupied a special place among thefungi; he placed them in the Phycascomycetes, a name he proposedbecause of the superficial similarities both to the Ascomycetes and to theRhodophyta (red algae). Until g<strong>en</strong>eticists unquestionably proved thatAscomycetes derived from Chytridiomycetes-like ancestors, this “Red Algal (orFloridean) Hypothesis” persisted (JAMES et al., 2006). The analysis of JAMES et al.(2006) suggests that several clades of the Chytridiomycota (true fungi, stillproducing zoospores) form a paraphyletic assemblage at the base of the

Fungi, consist<strong>en</strong>t with the view that the pres<strong>en</strong>ce of flagella is an ancestralcharacter state in the Fungi.The first observation of a member of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales in Belgium took place by Cépède andBondroit, in October 1910. It concerned a Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia rougetii Mont. & C.P. Robin, parasitizingBrachynus crepitans (COLLART, 1947).1.3. MORPHOLOGY OF THE THALLUS (TA VA R E S, 1985; MA J EWSKI, 1994)Figure I: Thallus of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia calathi (from Calathus melanocephalus, specim<strong>en</strong> 3a, thallus 1).Abbreviations: f foot, I + II + III cells of primary axis of the receptacle, IV + V additional cells of thereceptacle, andr androstichum (complex of cells III-V), cell e insertion cell, ia inner app<strong>en</strong>dage, oaouter app<strong>en</strong>dage, VI stalk cell of the perithecium, VII secondary stalk cell, s stalk, p perithecium.Scale bar = 50 µm. Picture by Danny Haelewaters (2010).1.3.1. INTRODUCTIONThe thallus of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales develops from a bicellular ascospore, by arestricted number of mitotic divisions, therefore resulting in a thallus with arestricted number of cells. The primary septum separates the larger andsmaller cell of the ascospore. It is oft<strong>en</strong> detected by its thickness and colour(slightly dark<strong>en</strong>ed).The main axis of the thallus is formed by the receptacle, which is attached atthe host‟s integum<strong>en</strong>t by means of a foot. Both the receptacle and the footoriginate from the larger – lower – cell of the ascospore. Additional divisions ofsome receptacle cells account for the perithecia, the only spore formingstructures within the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales (no asexual spore formation pres<strong>en</strong>t). Thesmaller cell of the ascospore produces the primary app<strong>en</strong>dage system – this isa prolongation of the receptacle axis. On the primary app<strong>en</strong>dage, or on itsbranches, there is formation of antheridia, which produce spermatia.Thalli have a bilateral symmetry. This kind of symmetry occurs in many groupsof animals, but only exceptionally in plants and fungi.P a g e | 11

1.3.3. THE PERITHECI UMAscospores originate in the perithecium. TAVARES (1967, 1985) used peritheciumdevelopm<strong>en</strong>t and external structure of the perithecial wall to describe highertaxa. The perithecium is formed by divisions of one of the primary orsecondary receptacle cells. This gives at once the differ<strong>en</strong>tiation betwe<strong>en</strong>primary and secondary perithecium. In species without secondarily dividedreceptacle cells, the perithecium arises by divisions of cell II.We can distinguish the stalk and the perithecium:The stalk comprises two cells, the stalk cell (cell VI) and the secondary stalkcell (cell VII). The stalk cell is usually clearly visible; it subt<strong>en</strong>ds the basalcells of the perithecium (m, n and n’). Cell VII is directly derived from thestalk cell and is situated abaxially.The perithecium is more or less elongated and narrowed distally.Sometimes it is clearly differ<strong>en</strong>tiated into a rounded v<strong>en</strong>ter and a narrowneck (apex), terminating in an ostiole. The apex can rarely beasymmetric, so that the ostiole is situated subapical. The perithecial wallcells surrounding the ostiole oft<strong>en</strong> form distinct lips.The perithecium always consists of a well determined number of cells.Exceptions on this are g<strong>en</strong>era in Herpomycetidae and Ceratomycetidae. Thelowest cells of the perithecium, just above the stalk cell and secondary stalkcell, are the basal cells. Usually, there are three such cells: the cell m is formedfrom cell VI, the cells n and n’ originate from cell VII. Divisions of cells n and n’result in three vertical rows of perithecial wall cells. The fourth row is formed bydivisions of cell m.The perithecial wall is double, i.e. composed of an interior and exterior part.The number and shape of the external wall cells plays an important role intaxonomy. The cells of the external wall are arranged in four vertical rows. Inprimitive g<strong>en</strong>era, the number of cells in each of these rows is large; in othergroups, such as the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae, the vertical rows are composed of 4-5superposed cells. In contrast to the primitive g<strong>en</strong>era, the cells in theLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae are usually unequal in height, with the lower ones beingelongated and the apical ones being short<strong>en</strong>ed.The basal part of the interior part of the perithecium contains the ascogonium.After fertilization through the trichogyne, it undergoes divisions resulting in oneto numerous ascog<strong>en</strong>ous cells. The ascog<strong>en</strong>ous cells give rise to new ascicontaining ascospores. The ascus wall is very thin; it disintegrates while still inthe perithecium during spore maturation.The trichogyne is an external thin app<strong>en</strong>dage-like outgrowth of the youngperithecium. It is the place through which fertilization proceeds, a process inwhich differ<strong>en</strong>t steps are recognized. At first, the trichophoric cell connectsthe trichogyne with the ascogonium within the perithecium. At an early stageof developm<strong>en</strong>t, the perithecium is equipped with a trichogyne that receivesspermatia from the antheridia (TAVARES, 1985; DE KESEL, 1997). The next step inthe fertilization process is the fusion betwe<strong>en</strong> the nuclei of the spermatium andthe ascogonium. The trichogyne deteriorates early after fertilization, except forthe basal part which oft<strong>en</strong> remains as a more or less promin<strong>en</strong>t scar on thesurface of the mature perithecium.P a g e | 13

Figure II: Thallus of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia calathi (from Calathus melanocephalus, specim<strong>en</strong> 3c, thallus 1),showing the trygogyne (arrow). Scale bar = 50 µm. Picture by Danny Haelewaters (2010).1.3.4. THE APPENDAGESThe upper – smaller – cell of the germinating ascospore produces the primaryapp<strong>en</strong>dage system only. The primary app<strong>en</strong>dage is usually a directcontinuation of the receptacle axis. Its upper part sometimes carries a spine,the remains of the pointed spore apex. Ext<strong>en</strong>sion of cytoplasma intoapp<strong>en</strong>dage branches takes place just below the spore apex, which is spinose.The failure of the spore apex to elongate directly upwards suggests that thespinose tip has a wall incapable of expansion. In Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia andStichomyces, on the contrary, no trace of the spore apex remains at maturity.The upper cell of the ascospore elongates directly upwards in these twog<strong>en</strong>era.Primary app<strong>en</strong>dages pres<strong>en</strong>t differ<strong>en</strong>t ways of appearance. In some g<strong>en</strong>erathey consist of only one or two cells. Ext<strong>en</strong>sive primary app<strong>en</strong>dage systemsoccur in Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia and some other g<strong>en</strong>era. In Dipodomyces monstruosusand – probably – Chaetarthriomyces flexatus the primary app<strong>en</strong>dagebecomes aborted.The basal cell of the primary app<strong>en</strong>dage of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia, also called theinsertion cell (cell e), is dark<strong>en</strong>ed and flatt<strong>en</strong>ed. This insertion cell gives rise toand supports the outer and inner app<strong>en</strong>dages. The outer (abaxial)app<strong>en</strong>dage is simple or branched but usually sterile, whereas the inner(adaxial) app<strong>en</strong>dage is shorter and bears flask shaped antheridia. The outerapp<strong>en</strong>dage may break off as the thallus develops.Little is known about the function of the sterile app<strong>en</strong>dages. It is suggestedthat they play a role in water balance of the thallus (DE KESEL, 1996). However,no specific research has yet be<strong>en</strong> done in this direction.The secondary app<strong>en</strong>dages are less diverse. They include all app<strong>en</strong>dages,derived from the lower spore cell. Secondary app<strong>en</strong>dages can be simple orbranched, and sterile or bearing antheridia. In some g<strong>en</strong>era, the secondaryapp<strong>en</strong>dage is two-celled. The distal cell is separated from the basal one by ablack septum and oft<strong>en</strong> breaks off.P a g e | 14

The id<strong>en</strong>tity of app<strong>en</strong>dages, together with the way of reg<strong>en</strong>erating in maturethalli, is very important wh<strong>en</strong> describing species.1.3.5. THE ANTHERIDIAIn the primitive repres<strong>en</strong>tatives of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales, spermatia areg<strong>en</strong>erated exog<strong>en</strong>ously. However, for many primitive species, the manner offormation of spermatia has not yet be<strong>en</strong> observed. Exog<strong>en</strong>ous spermatialproduction is found mainly in species associated with aquatic hosts (WEIR &BLACKWELL, 2005).In the major part of the order, spermatia are <strong>en</strong>dog<strong>en</strong>ously formed within thespecialized antheridial cells. Antheridia can be found on both the primary andsecondary app<strong>en</strong>dages. They oft<strong>en</strong> occur as an individual cell, usually with asl<strong>en</strong>der neck functioning as a discharge tube. In Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia,Stigmatomyces, and many other g<strong>en</strong>era, the antheridia are rather short andstout, with slightly narrowed necks. Herpomyces has very sl<strong>en</strong>der antheridia,which are taller than those in Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia and others. In some g<strong>en</strong>era theapp<strong>en</strong>dage cells function as antheridia, with only the discharge tube beingfree (e.g. Chaetarthriomyces).In some species, old antheridia proliferate into sterile branchlets.frequ<strong>en</strong>tly happ<strong>en</strong>s in many members of the g<strong>en</strong>us Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia.ThisCompound antheridia only occur in repres<strong>en</strong>tatives of the subfamiliesPeyritschielloideae and Monoicomycetoideae. Antheridial cells are arrangedso that the spermatia are released into a „chamber‟ (an intercellular space)with only one common exit. In the Monoicomycetoideae, the antheridia arerounded distally, with an indistinguishable pore. Compound antheridia with anelongated neck occur in the Peyritschielloideae. This shows that compoundantheridia originated more than once, as suggested by FAULL (1911).BENJAMIN (1971) wrote that of the 115 g<strong>en</strong>era of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales th<strong>en</strong>recognized, 25 g<strong>en</strong>era had no known male sexual structures. Somedescriptions „with reservation‟ have be<strong>en</strong> made.These three ways of spermatia formation – exog<strong>en</strong>ously, <strong>en</strong>dog<strong>en</strong>ously insimple antheridia, <strong>en</strong>dog<strong>en</strong>ously in compound antheridia – were used byTHAXTER (1896, 1908) as main criterion in the classification of the orderLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales.1.3.6. THE ASCOSPORESCharacteristics are: hyaline, elongate, spindle-shaped, surrounded by a thinmucilaginous <strong>en</strong>velope which makes them adhesive, immobile and relativelylarge (20-80 μm). The ascospores of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales are exclusively spread bythe activities of the host (DE KESEL, 1993; DE KESEL, 1996; DE KESEL, 1997) andtransmitted directly or indirectly (cfr. 1.6.1. TRANSMISSION OF SPORES).Ascospores are formed in the perithecium in such way that their larger cell isdirected upwards, and thus the first to be released from the ostiole.P a g e | 15

Figure III: Detail of thallus ofLaboulb<strong>en</strong>ia pedicellata (fromBembidion guttula, specim<strong>en</strong> 12a,thallus 2), showing the peritheciumwith ascospores. Scale bar = 20µm. Picture by Danny Haelewaters(2010).Adher<strong>en</strong>ce to the host surface is beingfacilitated by the sticky <strong>en</strong>velope. Sporesalways consist of two unequal parts. Thelarger cell initiates the parasitic contactby forming the foot (also the receptacleoriginates from this cell). A septumseparates the basal cell from the smallerapical one. As m<strong>en</strong>tioned before, thesmaller cell produces the app<strong>en</strong>dagesystem.[For detailed information about the ontog<strong>en</strong>y of theLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales, one is referred to TAVARES (1985), DEKESEL (1989) and WEIR & BEAKES (1996), whoext<strong>en</strong>sively described the <strong>en</strong>tire developm<strong>en</strong>t (fromascospore to mature thallus).]1.4. CLASSIFICATION OF THE <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>1.4.1. POSI TION AMONG THE FUNGIThere has be<strong>en</strong> much debate about the group the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales belong to.They have be<strong>en</strong> considered to be acanthocephalans, basidiomycetes,zygomycetes, as well as ascomycetes. However, molecular analysis by WEIR &BLACKWELL (2001b) strongly supports the hypothesis that the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales-Pyxidiophora clade belongs within the Ascomycota. Dep<strong>en</strong>ding on theauthor, this Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales-Pyxidiophora clade is treated as a separate class(Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iomycetes) or as a subclass (Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iomycetidae) (cfr. Table IIbelow). Within the Ascomycota, the order of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales can becharacterized by the abs<strong>en</strong>ce of mycelium, abs<strong>en</strong>ce of anamorphic stage,obligate parasitism on Arthropoda and individualized thick-walled thalliproducing only two-celled ascospores (BARR, 1983). Since their discovery, thereis agreem<strong>en</strong>t that these fungi form a separate group within the phylog<strong>en</strong>etictree. Especially the nearly invariable spore morphology suggests that thegroup is monophyletic (BENJAMIN, 1973); this monophyly is confirmed byphylog<strong>en</strong>etic analysis (WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001b) (cfr. Figure IV below).Table II: Classification of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales among the Fungi, according to KIRK et al. (2001) versusHIBBETT et al. (2007) and LUMBSCH & HUHNDORF (2007).Kingdom FungiKingdom FungiSubkingdom DikaryaPhylum AscomycotaPhylum AscomycotaSubphylum PezizomycotinaClass Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iomycetesClass AscomycetesSubclass Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iomycetidaeOrder Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ialesOrder PyxidiophoralesOrder Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ialesOrder PyxidiophoralesKIRK et al., 2001 HIBBETT et al., 2007; LUMBSCH & HUHNDORF, 2007P a g e | 16

Figure IV: Position of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iomycetes among the Fungi, from The Tree of Life Web Project(SPATAFORA, 2007).1.4.2. CLASSIFICATI ON OF THE <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>“The structure of the perithecium and the relatively greater complication inthe g<strong>en</strong>eral structure of both sexes (of Herpomyces) might be assumed toplace it higher in the scale than either Amorphomyces or Dioicomyces,although the occurr<strong>en</strong>ce of a series of forms on Blattidae, which are supposedto be repres<strong>en</strong>tatives of one of the most anci<strong>en</strong>t types of true insects, mightperhaps have be<strong>en</strong> expected to be correlated with a more primitive type inthe parasite. But although the unisexual forms with simple antheridia might forsome reasons be assumed to be the more primitive, the pres<strong>en</strong>t g<strong>en</strong>us isdistinguished by a far more complicated structure than the other unisexualforms of the same type, and Amorphomyces still remains… by far the simplestin structure of all the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales.”– Roland Thaxter, 1908The order of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales pres<strong>en</strong>tly comprises over 2000 species in 143g<strong>en</strong>era (SANTAMARIA, 1998; KIRK et al., 2001; WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2005; LUMBSCH &HUHNDORF, 2007), and it is expected that this number will increase by futurestudies. THAXTER (1896, 1908) used the differ<strong>en</strong>t ways of spermatia formation –exog<strong>en</strong>ously, <strong>en</strong>dog<strong>en</strong>ously in simple antheridia, <strong>en</strong>dog<strong>en</strong>ously in compoundantheridia – as main criterion in the classification.P a g e | 17

Table III: Classification of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales, comparison betwe<strong>en</strong> THAXTER (1908) and TAVARES (1985).THAXTER‟S classification (1908) TAVARES‟ classification (1985)Suborder Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iineae (Endog<strong>en</strong>ae)Suborder HerpomycetinaeFamily Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceaeTribe HerpomyceteaeTribe AmorphomyceteaeTribe StigmatomyceteaeTribe IdiomyceteaeTribe TeratomyceteaeTribe CorethromyceteaeTribe Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ieaeTribe RhachomyceteaeTribe ClematomyceteaeTribe CompsomyceteaeTribe ChaetomyceteaeTribe EcteinomyceteaeTribe MisgomyceteaeFamily PeyritschiellaceaeTribe DimorphomyceteaeTribe RickieaeTribe PeyritschielleaeTribe EnarthromyceteaeTribe HaplomyceteaeSuborder Ceratomycetineae (Exog<strong>en</strong>ae)Tribe CeratomyceteaeTribe ZodiomyceteaeFamily HerpomycetaceaeTribe HerpomyceteaeSuborder Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iinaeFamily CeratomycetaceaeSubfamily TettigomycetoideaeSubfamily CeratomycetoideaeTribe ThaumasiomyceteaeTribe CeratomyceteaeSubtribe HelodiomycetinaeSubtribe CeratomycetinaeTribe DrepanomyceteaeFamily EuceratomycetaceaeFamily Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceaeSubfamily ZodiomycetoideaeSubfamily Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ioideaeTribe CompsomyceteaeSubtribe CompsomycetinaeSubtribe KainomycetinaeTribe HydrophilomycetaeTribe CoreomyceteaeTribe TeratomyceteaeSubtribe TeratomycetinaeSubtribe RhachomycetinaeSubtribe ChaetomycetinaeSubtribe FilariomycetinaeSubtribe SmeringomycetinaeSubtribe ScelophoromycetinaeSubtribe HisteridomycetinaeSubtribe RhipidiomycetinaeSubtribe AmphimycetinaeSubtribe AsaphomycetinaeTribe Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ieaeSubtribe Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iinaeSubtribe MisgomycetinaeSubtribe ChitonomycetinaeSubtribe ChaetarthriomycetinaeSubtribe StigmatomycetinaeSubtribe AmorphomycetinaeTribe EuphoriomyceteaeSubtribe EuphoriomycetinaeSubtribe AporomycetinaeSubfamily PeyritschielloideaeTribe PeyritschielleaeSubtribe PeyritschiellinaeSubtribe MimeomycetinaeSubtribe EnarthromycetinaeSubtribe DiandromycetinaeTribe DimorphomyceteaeTribe HaplomyceteaeSubtribe HaplomycetinaeSubtribe KleidiomycetinaeSubfamily MonoicomycetoideaeP a g e | 18This way of separating groups in the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales was universally accepted,until TAVARES (1967, 1985) applied a new way for classification using peritheciumdevelopm<strong>en</strong>t and perithecial wall structure as characteristics. Table III pres<strong>en</strong>tsthe comparison betwe<strong>en</strong> THAXTER (1908) and TAVARES (1985).

LUMBSCH & HUHNDORF (2007) distinguish four families within the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales, asalready recognized by TAVARES (1985):Ceratomycetaceae 12 g<strong>en</strong>era;Euceratomycetaceae 5 g<strong>en</strong>era;Herpomycetaceae 1 g<strong>en</strong>us;Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iaceae 125 g<strong>en</strong>era.1.5. HOSTS1.5.1. GENERALLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales are found on theintegum<strong>en</strong>t of living arthropods,mostly true insects. Table IV shows thedistribution of arthropod hosts beingparasitized by Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales. Themajority of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ialesparasitize repres<strong>en</strong>tatives of thesubphylum Hexapoda, oft<strong>en</strong>Coleoptera (beetles). About 80% ofthe described species ofLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales parasitize beetles(WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2005).The vast majority of the beetle hostsare repres<strong>en</strong>tatives of the twofamilies Carabidae (ground beetles)and Staphylinidae (rove beetles).Also other coleopteran families arebeing parasitized in minor degree,among them Alexiidae, Anthicidae,Apotomidae, Byrrhidae, Catopidae,Cerambycidae, Chrysomelidae,Ciidae, Clambidae, Cleridae,Coccinellidae, Corylophidae, Cryptophagidae,Cucujidae, Dryopidae,Table IV: Distribution of arthropod hostsparasitized by Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales, persubphylum.Phylum ArthropodaSubphylum CheliceriformesClass ChelicerataSubclass ArachnidaOrder AcariSubphylum MyriapodaClass DiplopodaSubclass ChilognathaOrder CallipodidaOrder JulidaOrder SphaerotheriidaOrder SpirostriptidaSubphylum HexapodaClass PterygotaSubclass ExopterygotaOrder HemipteraOrder MallophagaOrder ThysanopteraOrder DictyopteraOrder OrthopteraOrder DermapteraOrder IsopteraSubclass EndopterygotaOrder Hym<strong>en</strong>opteraOrder DipteraOrder ColeopteraDytiscidae, Elateridae, Endomychidae, Erotylidae, Gyrinidae, Haliplidae,Heteroceridae, Histeridae, Hydra<strong>en</strong>idae, Hydrophilidae, Lathridiidae,Leiodidae, Limnichidae, Microsporidae, Mycetophagidae, Nitidulidae,Passalidae, Phalacridae, Ptiliidae, Scarabaeidae, Scydma<strong>en</strong>idae, Silphidae,Silvanidae and T<strong>en</strong>ebrionidae and Zopheridae (HINCKS, 1960; SCHELOSKE, 1969;MAJEWSKI, 1994, 2003; SANTAMARÍA et al., 1991; DE KESEL, 1997).[Name changes and updates on taxonomy were reviewed using VORST (2010). For example, manylaboulb<strong>en</strong>ialean species have be<strong>en</strong> recorded on members of the former family Pselaphidae,nowadays regarded as a subfamily Pselaphinae within the Staphylinidae.]P a g e | 19

Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales only occur on adult hosts. BENJAMIN (1971) reports a fewcontrary studies, in which has be<strong>en</strong> observed that repres<strong>en</strong>tatives of theLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales can grow also on immature stages. Herpomyces stilopygae,for example, grows on nymphs as well as on adults of their host (Blattaori<strong>en</strong>talis, suborder Blattodea, order Dictyoptera). However, infection is lessint<strong>en</strong>se on nymphs and disappears completely with the molt (RICHARDS & SMITH,1955).1.5.2. ORDER COLEOPTERAThe Coleoptera form the most diverse group of extant Metazoa. Beetles arevirtually everywhere; they show an extreme diversity both ecologically andmorphologically. Their size ranges from tiny animals of nearby 0,3 mm(Ptiliidae) to „giants‟ of almost 18 cm (Titanus giganteus, the giant Amazonianlonghorn beetle) (PONS et al., 2010). The order consists of 370.000 speciesspread over 166 families (BURNIE, 2001), and is the largest of all insect orders. InWest-Europe, 5.000 species have be<strong>en</strong> described.Coleopterans have two pairs of wings, of which the first pair is hard or leathery.The first wings – called elytra – touch each other dorsally. The second pair ofwings is membranous and lies folded up underneath the elytra. Sometimes thesecond pair of wings is not pres<strong>en</strong>t or reduced (brachypterous); some speciesev<strong>en</strong> have no wings at all (apterous).Mouth parts of coleopterans are always biting. This is a physical constraint;beetles, however, have invaded all available biotopes (including the sea) andop<strong>en</strong>ed up all possible food sources. The order comprises herbivores,detritivores, predators and parasites. Many species play a negative role forman: cockshafers and many other species harm our crops. Beetles, on theother hand, can be very useful allies in the battle against other threat<strong>en</strong>inginsects. In particular lady birds, that eat gre<strong>en</strong>flies, are important. All mouthparts, including the biting mandibles, are well developed. However, thisdoesn‟t mean that beetles are restricted to solid food; many species soak theirfood with digestive fluid before taking it up. Other species lick nectar, whilelarvae of ev<strong>en</strong> other species suck liquid food with their tube-like mandibles.The order of the Coleoptera consists of three suborders: Adephaga,Polyphaga and Archostemmata. The latter is not repres<strong>en</strong>ted in Europe. Thesuborder of the Adephaga is the more primitive suborder and consists ofcarnivorous species. The name Adephaga refers to the habit to run after food(Latin ad = [go] to). The suborder of the Polyphaga is the larger one, and – ascan be expected (Polyphaga means „eating lots of things‟) comprises manyincoher<strong>en</strong>t repres<strong>en</strong>tatives. The phylog<strong>en</strong>y of this group is far from beingelucidated. Ev<strong>en</strong> after 20 years of research, there still are large and ratherheterog<strong>en</strong>eous superfamilies in the suborder Polyphaga.The family of the Staphylinidae (suborder Polyphaga) is parasitized by thegreatest number of g<strong>en</strong>era of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales (49 g<strong>en</strong>era; TAVARES, 1979).The family of the Carabidae (suborder Adephaga) is parasitized by 15 g<strong>en</strong>era(TAVARES, 1979). Also the family of the Hydrophilidae is parasitized by 15g<strong>en</strong>era, but by a much smaller number of species (TAVARES, 1979).P a g e | 20

Substrate is the intermediate factor in the case of indirect (self-)transmission(cfr. Figure V below, right). The indirect transmission of L. slack<strong>en</strong>sis is stronglyaffected by the age of the spores (DE KESEL, 1995b).It has be<strong>en</strong> experim<strong>en</strong>tally prov<strong>en</strong> by DE KESEL (1995b) that the differ<strong>en</strong>cebetwe<strong>en</strong> direct and (lower) indirect transmission with L. slack<strong>en</strong>sis is due to thelow output of ascospores towards the <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t. Spores ooze out of theperithecium and form adher<strong>en</strong>t thread-like structures, favouring the return tothe host (direct self-transmission) or a co-habitant with whom contact wasmade (direct transmission).Also the biology of the host is of great significance: Clivina fossor, host forLaboulb<strong>en</strong>ia clivinalis Thaxt., leads a mainly subterranean way of life. Thereforethe importance of indirect transmission must not be underestimated (DE KESEL,1995a).1.6.2. MODEL OF ISLAND BIOGEOGRAPHY (MACA R T H U R & WI L S O N, 1967)The host populations of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales are probably similar to islands in themodel of Island Biogeography (DE KESEL, 1996, 1997): the diverg<strong>en</strong>ce of hostpopulations will lead to diverg<strong>en</strong>ce of the parasites by isolation of g<strong>en</strong>e pools(reinforced ecological isolation).The great diversity in ecological adaptations of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales within thefamily of the Carabidae is probably closely related to the differ<strong>en</strong>t modes ofbehavior, habitat prefer<strong>en</strong>ces and physiological requirem<strong>en</strong>ts of the carabidhosts. Specialization of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales is the result of 1/ obligateectoparasitism, 2/ host specificity and 3/ dep<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>ce on a specific<strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t.1.6.3. DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS (D E K E S E L, 1997)There are two distribution patters of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales:One specific host group parasitized by a large number of unrelatedparasite g<strong>en</strong>era Staphylinidae;Many related parasite taxa parasitizing a single host family Carabidae.The adaptive radiation of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia g<strong>en</strong>us within each tribe of thefamily of the Carabidae is indicated by the significant relationship betwe<strong>en</strong>the number of host species in each Carabidae-tribe and the number ofLaboulb<strong>en</strong>ia species parasitizing hosts of that tribe.In g<strong>en</strong>eral, it is likely that most epidemiological traits of host-parasiterelationships are controlled by complex interactions betwe<strong>en</strong> the bothg<strong>en</strong>otypes (GHxGP interactions; VALE et al., 2008). Moreover, ev<strong>en</strong>phylog<strong>en</strong>etic correspond<strong>en</strong>ce betwe<strong>en</strong> parasite and host can be important.A history of parallel diversification betwe<strong>en</strong> parasite and host has tak<strong>en</strong> careof concordant (~ congru<strong>en</strong>t) phylog<strong>en</strong>ies betwe<strong>en</strong> the both (as suggested byFUTUYAMA, 2005). Although no study has yet be<strong>en</strong> conducted in whichspecifically phylog<strong>en</strong>ies were compared, the above seems obvious: adaptiveradiation of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales dep<strong>en</strong>ds upon the number of available hosts inthe host taxon.P a g e | 22

An all-inclusive discussion on the parallels betwe<strong>en</strong> host phylog<strong>en</strong>y andLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales phylog<strong>en</strong>y based alone on the host-parasite list is unrealistic.DE KESEL (1997) suggests that that the latter can be used in host cladistics, ifcombined with morphological, physiological, etc. data from the hosts.1.6.4. DETERMINING FACTORSAll factors with some influ<strong>en</strong>ce on the occurr<strong>en</strong>ce and growth of thalli can besummarized in two groups: the host (1) and the (host‟s) <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t. The lattercategory can be classified once more into abiotic (2) and biotic (3)<strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>tal factors (DE KESEL, 1991; DE KESEL, 1993).Abiotic factors can be temperature, day l<strong>en</strong>gth, humidity, substratecharacteristics, … Among biotic factors are beetle behavior (reproduction,activity), population d<strong>en</strong>sity and population structure. Abiotic factors alwaysstrongly influ<strong>en</strong>ce biotic factors.Observations of Clivina fossor during a complete year-cycle (DE KESEL, 1995a)suggest that the increasing temperature, host activity and the specificmicrohabitat selection of the host in spring <strong>en</strong>hances the thallus d<strong>en</strong>sity ofparasitizing Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia clivinalis. DE KESEL (1995b, 1996) proved forLaboulb<strong>en</strong>ia slack<strong>en</strong>sis that the indirect transmission (1.6.1. TRANSMISSION OFSPORES) is not affected by the substrate.Artificial infections with L. slack<strong>en</strong>sis showed that the parasite is pot<strong>en</strong>tiallyplurivorous on Carabidae (cfr. 1.7.3.2. Host specificity). The involvem<strong>en</strong>t of L.slack<strong>en</strong>sis in an intimate association is determined by several factors, includingits own <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>tal prefer<strong>en</strong>ces, characteristics of the host integum<strong>en</strong>t, themicroclimate in the host‟s surface and the availability of nutri<strong>en</strong>ts (DE KESEL,1996). Successful establishm<strong>en</strong>t of the parasite requires both the pres<strong>en</strong>ce of apot<strong>en</strong>tial host and favorable <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>tal conditions for the fungus.[More detailed information on the ecology of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales can be found in SCHELOSKE, 1969 andDE KESEL, 1997.]1.7. PATHOGENICITYP a g e | 231.7.1. ARE <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong> REAL P ARASITES?Undoubtedly, the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales are obligate ectoparasites of their arthropodhosts (SCHELOSKE, 1969; BENJAMIN, 1971; MAJEWSKI, 1994). In nature, they neveroccur apart from hosts, and attempts to grow members of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ialesin ax<strong>en</strong>ic culture failed at early stages (BENJAMIN, 1971; WEIR & BLACKWELL,2001a). WHISLER (1967) did succeed in early developm<strong>en</strong>t of the thalli to the 20-cell stage. To this <strong>en</strong>d, ascospores from Fanniomyces ceratophorus (Whisler) T.Majewski were placed on a medium consisting mainly of brain-heart infusionagar. However, no developm<strong>en</strong>t of the perithecial phase was initiated.Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales cannot survive without nutri<strong>en</strong>ts of their host; there is noevid<strong>en</strong>ce of the host receiving something in exchange. Thus, most probably,they are parasites. However, since no precise experim<strong>en</strong>tal data on th<strong>en</strong>utrition of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales is available (BENJAMIN, 1971; DE KESEL, 1997),things remain unclear. It could be a comm<strong>en</strong>sal or mutualistic relationship(dep<strong>en</strong>ding on how much the host would attain in return).

CAVARA (1899, ref. in BENJAMIN, 1971) suggested that Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales was ableto retrieve nutri<strong>en</strong>ts from the <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t by means of the trigogyne or sterileapp<strong>en</strong>dages. SPEGAZZINI (1917), inspired by the abs<strong>en</strong>ce of visible damage onthe host cuticle, suggested nearly the same idea: the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales retrievingtheir food from the <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t, ev<strong>en</strong> without app<strong>en</strong>dages, as there aremany species. However, these are hypotheses; more research is needed in thisarea. DE KESEL (1996) assumes that the app<strong>en</strong>dages play a role in the waterbalance of the thallus.1.7.2. ATTA CHMENT TO THE HOS TFigure VI: Detail of thallus ofLaboulb<strong>en</strong>ia calathi (from Calathusmelanocephalus, specim<strong>en</strong> 3a,thallus 1), showing the foot (arrow).Scale bar = 20 µm. Picture by DannyHaelewaters (2010).Thalli of nearly all species of theLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iales are attached to theirhost through the modified lowermostpart of the basal cell of the receptacle,the foot (cfr. Figure VI). In most species,the foot is black. The developm<strong>en</strong>t ofthe foot occurs very early in thallusontog<strong>en</strong>y, starting with a thick<strong>en</strong>ingmucilaginous sheath at one side of theascospore, probably as the firstdiffer<strong>en</strong>tiation of the basal cell;observed by TAVARES (1985) and DE KESEL(1989).Most Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales do not p<strong>en</strong>etrateinto living tissue of their host, but make contact through integum<strong>en</strong>t pores(TAVARES, 1985).In a few g<strong>en</strong>era (e.g. Arthrorhynchus), the foot is abs<strong>en</strong>t and the basal cellp<strong>en</strong>etrates into the host hemocoel through well developed haustoria(MAJEWSKI, 1994). Herpomyces species make contact with the host by manyhaustoria of the secondary receptacle, p<strong>en</strong>etrating only into the epidermalcell layer. Also the species without any visible haustoria probably take upnutri<strong>en</strong>ts from the host hemolymph (SCHELOSKE, 1969).P a g e | 241.7.3. SPECIFICITY OF THE <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>1.7.3.1. Position specificityLaboulb<strong>en</strong>ia truncata Thaxt. and L. perp<strong>en</strong>dicularis Thaxt. are located onrestricted areas of the body of their host, Bembidion picipes (= positionspecificity): L. truncata on the tarsi of the forelegs of males, L. perp<strong>en</strong>dicularisbetwe<strong>en</strong> the coxae of the forelegs of female beetles. Both species alsodisplay a marked similarity of structure (BENJAMIN & SHANNOR, 1952). Whetherboth species are two differ<strong>en</strong>t taxa or growth forms of one species will have tobe studied by using both morphological and molecular methods.Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales can exhibit great ph<strong>en</strong>otypic plasticity. Growth position oft<strong>en</strong>leads to the developm<strong>en</strong>t of totally differ<strong>en</strong>t morphs on one host (BENJAMIN &SHANOR, 1952; BENJAMIN, 1971; SCHELOSKE, 1976; HULDÉN, 1985, ref. in DE KESEL, 1997;MAJEWSKI, 1994; DE KESEL & VAN DEN NEUCKER, 2005; DE KESEL & WERBROUCK, 2008).Many of these morphs have be<strong>en</strong> considered as differ<strong>en</strong>t taxa. BENJAMIN &SHANOR (1952) suggest that position specificity may be the result of particular

PART II<strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>:EXPLORINGANDTESTINGDNA EXTRACTION PROTOCOLSP a g e | 31

1. INTRODUCTION1.1. DIFFICULTIES FOR DNA EXTRACTION OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>Molecular studies of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales are chall<strong>en</strong>ging for the following reasons(WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001a):The microscopic size of the thalli (l<strong>en</strong>gth range [35 μm – 2 mm], on average200-300 μm) (SCHELOSKE, 1969; HULDÉN, 1983; SANTAMARÍA, 1998);Thalli require micromanipulation techniques in order to remove them fromtheir hosts;Thalli are heavily melanized and difficult to break op<strong>en</strong>;The outer <strong>en</strong>velope comprises an adhesive mucilaginous compon<strong>en</strong>tinterfering with c<strong>en</strong>trifugation;Recalcitrance to ax<strong>en</strong>ic culture.Many differ<strong>en</strong>t approaches did not succeed in releasing DNA. Differ<strong>en</strong>tapproaches were used, most without any success: prolonged boiling of thalli(HANSON, 1992), microwave treatm<strong>en</strong>t (GOODWIN & LEE, 1993) and immersion inliquid nitrog<strong>en</strong> (HAUGLAND et al., 1999). Also direct addition of intact thalli toPCR mastermix was unsuccessful (e.g. pers. comm. DE KESEL, 2009).Beyond this, extra problems arose wh<strong>en</strong> working with hosts that are dried orpreserved in ethanol (95 %) (WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001a).1.2. GENBANK1.2.1. THE GENBANK SEQUENCE DATABAS EDatabases form the basis for most applications in bioinformatics. The G<strong>en</strong>Banksequ<strong>en</strong>ce database is an op<strong>en</strong> access, annotated collection of all publiclyavailable DNA sequ<strong>en</strong>ces. G<strong>en</strong>Bank continues to grow at an expon<strong>en</strong>tial rate– in February 2008, there were approximately 82.853.685 sequ<strong>en</strong>ces inG<strong>en</strong>Bank; in October 2010 this number was already increased to 125.764.384(GENBANK RELEASE NOTES, 2010). This database is part of the InternationalNucleotide Sequ<strong>en</strong>ce Database Collaboration, which comprises the DDBJ, theEMBL, and G<strong>en</strong>Bank at the National C<strong>en</strong>ter for Biotechnology Information(NCBI). These three institutes exchange data on a daily basis.1.2.2. THE SEARCH FOR SEQUEN CES OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>/LABOUL-BENIOMYCETES IN GENBANKG<strong>en</strong>Bank only includes 21 repres<strong>en</strong>tatives of the order of the Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales,shown in Table VII below.Of the 27 sequ<strong>en</strong>ces in G<strong>en</strong>Bank, categorized within the classLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iomycetes, 19 are the same as with the „Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales‟ search.This could be the result of wrongly classified species. However, thisinconsist<strong>en</strong>cy can also be the consequ<strong>en</strong>ce of the two differ<strong>en</strong>t ways ofclassifying Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales. The remaining 8 sequ<strong>en</strong>ces are shown in Table VIIbelow.P a g e | 32

Table VII: Overview of all sequ<strong>en</strong>ces in G<strong>en</strong>Bank, found with both the „Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales‟ search (first 21sequ<strong>en</strong>ces) and the „Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iomycetes‟ search (last 8 sequ<strong>en</strong>ces). Abbreviations: bp number ofbase pairs, rRNA ribosomal RNA, SSU small subunit, LSU large subunit, TEF1- translation elongationfactor-1 , RPB2 RNA polymerase II second largest subunit.Sequnce l<strong>en</strong>gthSpeciesLocusAccession Publication[bp]Laboulb<strong>en</strong>iales sp. LM68 18S rRNA 1022 EF060444.1 (a)Rickia passalina 18S rRNA 490 AF432129.1 bCeratomyces mirabilis 18S rRNA 515 AF431764.1 bRhadinomyces pallidus 18S rRNA 515 AF431763.1 bCorethromyces bicolor 18S rRNA 502 AF431762.1 bCorethromyces sp. AW-2001 18S rRNA 515 AF431761.1 bBotryandromyces ornatus 18S rRNA 516 AF431760.1 bStigmatomyces rugosus 18S rRNA 514 AF431759.1 bStigmatomyces scaptomyzae 18S rRNA 518 AF431759.1 bStigmatomyces hydreliae 18S rRNA 516 AF431757.1 bRhachomyces philonthinus 18S rRNA 513 AF431756.1 bZodiomyces vorticellarius SSU rRNA 1083 AF407577.1 cStigmatomyces limnophorae SSU rRNA 1028 AF407576.1 cHesperomyces coccinelloides SSU rRNA 1038 AF407575.1 cHesperomyces viresc<strong>en</strong>s LSU rRNA 409 AF298235.1 dStigmatomyces protrud<strong>en</strong>s LSU rRNA 401 AF298234.1 dHesperomyces viresc<strong>en</strong>s SSU rRNA 1085 AF298233.1 dStigmatomyces protrud<strong>en</strong>s SSU rRNA 1081 AF298232.1 dPyxidiophora sp. IMI-1989 SSU rRNA 1103 AF313769.1 (e)Kathistes calyculata SSU rRNA 1089 AF313768.1 (e)Kathistes analemnoides SSU rRNA 1096 AF313767.1 (e)Pyxidiophora arvern<strong>en</strong>sis is. AFTOL-ID 2197 TEF-1 678 FJ238412.1 (f)Pyxidiophora arvern<strong>en</strong>sis is. AFTOL-ID 2197 RPB2 857 FJ238377.1 (f)Pyxidiophora arvern<strong>en</strong>sis is. AFTOL-ID 2197 28S rRNA 1080 FJ176894.1 (f)Pyxidiophora arvern<strong>en</strong>sis is. AFTOL-ID 2197 18S rRNA 1478 FJ176839.1 (f)Termitaria snyderi is. DAH 14 18S rRNA 1046 AY212812.1 gLaboulb<strong>en</strong>iopsis termitarius is. DAH 18 18S rRNA 998 AY212810.1 gPyxidiophora sp. 03 18S rRNA 1064 AY212811.1 gPyxidiophora arvern<strong>en</strong>sis18S rRNA +type I intron424 U43339.1 (h)[(a) MAHDI & DONACHIE, 2006 – unpublished; b WEIR & HUGHES, 2002; c WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001b; d WEIR & BLACKWELL,2001a; (e) WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2000 – unpublished; (f) SCHOCH, 2008 – unpublished; g HENK, WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2003; (h)Jones & Blackwell, 1995 – unpublished.]P a g e | 33

2. MATERIALS & METHODS2.1. FUNGUS, HOST AND ORIGINCarabid hosts of Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia species were collected in November 2008 and2009 (July – December) by means of hand capturing. All collecting sites aresituated in Hing<strong>en</strong>e (Belgium, Prov. Antwerp<strong>en</strong>, N51°06‟ – E4°12‟), atSchellandpolderdijk along the river Schelde.The collecting sites can be categorized as alluvial areas (polders). These areasare not flooded daily, being protected by dykes; they have fine alluvial soilsthat can become relatively dry in summer. The sampled alluvial areas consistmostly of poplar plantations or mixed forests with mainly Alnus, Fraxinus,Quercus and Acer.2.2. MORPHOLOGICAL PROTOCOL AND DNA EXTRACTION2.2.1. INTRODUCTIONThe hosts were narcotized in a pot filled with chloroform gas (insects had nocontact with liquid chloroform). Scre<strong>en</strong>ing of the hosts was done by using bothbinocular and stereomicroscope (50x). Separation of infected and uninfectedhosts had to be done with precision. Carabid hosts were id<strong>en</strong>tified to specieslevel, using the id<strong>en</strong>tification key of BOEKEN (1987).From this point, differ<strong>en</strong>t strategies were tried out, in order to improve themethodology. The protocols will be discussed below, in chronological order.2.2.2. PROTOCOL I (BASED ON WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001b)Thalli were aseptically removed from each host using a sterile micropin andtransferred to a 2 µL drop of Milli-Q H2O on a sterile microscope slide. An 18 x18 mm coverslip was placed over the thallus. Hosts were observed using aNikon SMZ800 stereoscopic zoom microscope (binocular); a Nikon Eclipse E600research microscope was used for visual inspection of the thalli. Thalli wereid<strong>en</strong>tified to species level using MAJEWSKI (1994), and photographed with NikonDigital Camera DXM1200. After photographing, the thalli were crushedbetwe<strong>en</strong> the two slides. A razor blade was used to remove the coverslip.Visual inspection was needed in order to find the thalli on the coverslip or themicroscopic slide. The crushed material was hydrated in 20 μL of extractsolution (cfr. Figure VIII for composition).99 µL Milli-Q H2O + 1 µL Triton (100%) 100 µL 1% Triton deterg<strong>en</strong>t1 µL 1% Triton + 19 µL Milli-Q H2O 20 µL extract solutionFigure VIII: Composition of extract solution.P a g e | 34The thalli were transferred into 2mL tubes using a sterile micropin. Glass beads(0,25-0,50 mm in diameter) were added to the tube. The cont<strong>en</strong>t of the tubewas additionally crushed in a bead beater (3 x 90 sec; 30x/s) (RETSCH Mixer MillMM200, Haan, Germany). C<strong>en</strong>trifugation took place for 2 minutes at 14.000rcf. 30 µL Milli-Q H2O was added to the tube, whereupon the tube was placed

in a heating block for 5 minutes at 100° C. Storage for short periods took placeat 2 – 7° C; for longer periods at -20° C.2.2.3. PROTOCOL II (BASED ON WEIR & BLACKWELL, 2001a)One thallus or a group of thalli inserted at the same place (two to nine) wereaseptically removed from each host using a sterile micropin and transferred toa 2 µL drop of 0.1xTE buffer (10 mM Tris.Cl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) on a sterilemicroscope slide. An 18 x 18 mm coverslip was placed over the thallus/thalli.Hosts were observed using a Nikon SMZ800 stereoscopic zoom microscope(binocular); a Nikon Eclipse E600 research microscope was used for visualinspection of the thalli. Thalli were id<strong>en</strong>tified to species level using MAJEWSKI(1994), and photographed with Nikon Digital Camera DXM1200. Afterphotographing, the thalli were crushed betwe<strong>en</strong> the two slides. The slide wasimmediately placed on a bed of dry ice (Ice Man BVBA, Bottelare, Belgium)and allowed to freeze. A razor blade was used to remove the coverslip. Visualinspection was needed in order to find the thalli on the coverslip or themicroscopic slide. 2 μL of the extract solution (cfr. Figure IX for composition)was pipetted on top of the crushed material.99 µL Milli-Q H2O + 1 µL Triton (100%) 100 µL 1% Triton deterg<strong>en</strong>t2 µL 1% Triton + 18 µL 0.1xTE buffer 20 µL extract solutionFigure IX: Composition of extract solution.This material was again allowed to freeze on the bed of dry ice. Wh<strong>en</strong> theextraction solution started to defrost, after removal from the dry ice, thethallus/thalli were transferred into a 2 mL tube, together with the remaining 18μL of extract solution. An additional 30 μL of 0.1xTE buffer was added,whereupon the tube was placed in a heating block for 15 minutes at 60° C.Storage took place at -20° C.2.2.4. PROTOCOL III: PUREGENE KIT ADNA was extracted using Qiag<strong>en</strong>‟s Pureg<strong>en</strong>e Kit A (Qiag<strong>en</strong>, The Netherlands)and the provided docum<strong>en</strong>ts at Gh<strong>en</strong>t University, research group Mycology.Qiag<strong>en</strong>, G<strong>en</strong>tra Pureg<strong>en</strong>e Handbook (2007).2.2.5. PROTOCOL IV: DNEASY EXTRACTION KITDNA was extracted using Qiag<strong>en</strong>‟s DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiag<strong>en</strong>, TheNetherlands) and the provided docum<strong>en</strong>ts at Gh<strong>en</strong>t University, research groupMycology. The elution of DNA for all specim<strong>en</strong>s was performed in duplicatewith 100 µL AE buffer. For every specim<strong>en</strong>, two elutions were carried out.In order to overcome ev<strong>en</strong>tual contaminations, single hosts were preced<strong>en</strong>tlyplaced in a ultrasonic bath for 5 minutes.Qiag<strong>en</strong>, DNeasy Plant Mini and DNeasy Plant Maxi Handbook (2004).P a g e | 35

2.2.6. PROTOCOL V: DIRECT PCROne thallus or a group of thalli inserted at the same place (two to nine) wereaseptically removed from each host using a sterile micropin, crushed andwithout any modification transferred into a 2 mL tube and used directly in PCRamplification.This protocol, however, provides more risk for contamination. Therefore, singlehosts were placed in a ultrasonic bath for 5 minutes.2.3. PCR AMPLIFICATION2.3.1. ITSThe internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the nuclear rRNA was amplifiedby PCR using the primer sets ITS5/ITS4A and ITS5/ITS2.Table VIII: Characteristics of primers used in this study: F forward, R reverse, Tm melting temperature (in°C), Ta optimal annealing temperature (in °C), #bp number of base pairs, GC perc<strong>en</strong>tage of GC bases, Rrefer<strong>en</strong>ce).Primer name Sequ<strong>en</strong>ce F/R Tm Ta #bp GC RITS5 5‟-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3‟ F 63 58 22 40,9 aITS4-A 5‟-CGCCGTTACTGGGGCAATCCCTG-3‟ R 68 63 23 65,2 bITS2 5‟-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3‟ R 62 57 20 55,0 a[a WHITE et al., 1990; b LARENA et al., 1999.]PCR micture (cfr. Table IX) consisted of CoralLoad PCR Buffer II (10x), MgCl2 (25mM), dNTP (10 mM), forward + reverse primer (10 µM), Taq polymerase (5 u/µL),H2O MilliQ and DNA extract. The total volume was 50 µL. All PCR reactionscontained 5 µl DNA extract. The next protocol was applied:Table IX: Overview of PCR compon<strong>en</strong>ts, amplification protocol.Chemical Refer<strong>en</strong>ce Conc<strong>en</strong>tration Volume/reaction [µl]PCR buffer II Qiag<strong>en</strong> Hild<strong>en</strong>, Germany 10x 5MgCl2 Qiag<strong>en</strong> Hild<strong>en</strong>, Germany 25 mM 0,5dNTP Epp<strong>en</strong>dorf Hamburg, Germany 10 mM 1Forward primer Invitrog<strong>en</strong> TM Merelbeke, Belgium 10 µM 1Reverse primer Invitrog<strong>en</strong> TM Merelbeke, Belgium 10 µM 1Taq polymerase Qiag<strong>en</strong> Hild<strong>en</strong>, Germany 5 u/µL 0,3H2O MilliQ / 36,2DNA extract / 5TOTAL 50The amplification was conducted un der the following conditions: an initiald<strong>en</strong>aturation step at 94° C for 10 minutes, 35 cycli of d<strong>en</strong>aturation (at 94° C for30 seconds), primer annealing (at 55° C for 30 seconds) and ext<strong>en</strong>sion (at 70°C for 45 seconds), and a final ext<strong>en</strong>sion step at 70° C for 10 minutes. Hereafter,the temperature was held constant at 20° C until PCR products were tak<strong>en</strong> outof the thermocycler.Only with the direct PCR protocol (2.2.7. PROTOCOL V: DIRECT PCR), the thallus ora group of thalli inserted at the same place were directly added to the PCRreaction.P a g e | 36

2.3.2. POST PCRPCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels in 1xTAEbuffer (Qiag<strong>en</strong>, The Netherlands). PCR products were run by 120 mV forapproximately 30 minutes using a 50 to 2000 bp molecular weight marker(Merck NV, Overijse, Belgium). After electrophoresis, gels were stained withethidium bromide (EtBr) and viewed under UV light (254-365 nm).2.4. SEQUENCING AND SEQUENCE ANALYSIS2.4.1 SEQUENCI NGThe obtained PCR products were purified using ExoSAP (USB ® , USA). The DNAsequ<strong>en</strong>cing reactions were performed with the ABI PRISM ® BigDyeTMTerminators v3.1 Cycle Sequ<strong>en</strong>cing Kit using the same primers on an ABI PRISM ®3130xl DNA Sequ<strong>en</strong>cer.2.4.2 SEQUENCE ANALYSISThe g<strong>en</strong>erated chromatograms were visualized using the programSequ<strong>en</strong>cher ® 4.9 (G<strong>en</strong>e Codes Corporation, Michigan, USA). These peak plotswere controlled and modifications were submitted manually.The modified sequ<strong>en</strong>ces were compared with DNA databank G<strong>en</strong>Bank. Theaim was to consider similarities with species already pres<strong>en</strong>t in G<strong>en</strong>Bank (1.2.2.THE SEARCH FOR SEQUENCES OF <strong>LABOULBENIALES</strong>/LABOUL-BENIOMYCETES IN GENBANK).Therefore, the program BLAST (Basic Local Alignm<strong>en</strong>t Search Tool) wasdeveloped. BLAST is supported by the National C<strong>en</strong>ter for BiotechnologyInformation (NCBI) and can be found at the following link:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST.The BLASTn search <strong>en</strong>ging was used, which is suitable for queries of 3000 or lessnucleotides in particular. All default algorithm parameters have be<strong>en</strong> used,except the “low complexity regions”. With this filter working, sequ<strong>en</strong>ces withlong series of A‟s or T‟s or repeating sequ<strong>en</strong>ces – such as GTGTGTGT – will berecognized and deleted. This function is used to exclude false similarities, butalso “real” similarities are deleted, leading to a false top 50 of similarsequ<strong>en</strong>ces in G<strong>en</strong>Bank.Each matching sequ<strong>en</strong>ce resulting from the BLASTn search is proved with:Accession number;Description;Max score;Total score;Query coverage;E value;Max id<strong>en</strong>tity.The accession number contains the link to view the <strong>en</strong>tire sequ<strong>en</strong>ce. The (max+ total) score is a number that counts for both the id<strong>en</strong>tities and gaps of thecompared sequ<strong>en</strong>ces. The query coverage is the perc<strong>en</strong>tage of the queryl<strong>en</strong>gth that is included in the aligned sequ<strong>en</strong>ces. The E(xpect) value describesthe number of matches a particular sequ<strong>en</strong>ce would be having by randomP a g e | 37

P a g e | 38chance. Thus, the lower the E value, the more significant the similarity of thequery sequ<strong>en</strong>ce to another. The max id<strong>en</strong>tity is the highest perc<strong>en</strong>tageid<strong>en</strong>tity for an aligned sequ<strong>en</strong>ce to the query sequ<strong>en</strong>ce (oft<strong>en</strong> referred to as„% similarity‟).

3. RESULTS3.1. DNA EXTRACTIONDNA was extracted from 48 specim<strong>en</strong>s. Hereafter, DNA was used for PCRreaction; except for the direct PCR protocol in which the thallus or groups ofthalli directly were transferred into the 2 mL tubes. With every DNA extractionprotocol, a negative control was included to check for contaminations duringthe extraction. The negative controls were included in the PCR reactions.3.2. AMPLIFICATION3.2.1. PRIMER PAIR ITS5/ITS4-AThe adapted ITS sequ<strong>en</strong>ces of specim<strong>en</strong>s labo1111 [immature thallus, DH 3B],flag1126 [thallus DH5A], flag1129 [thallus DH 5E], flag1131 [immature thalli, DH11A + 11B], labo1132 [thallus DH 11E], coll1133 [thallus DH 11F], labo1136[immature thallus, DH 12A], flag1137 [two thalli, DH 13A + 13B] and flag1141[thallus DH 13J] match for 99% with Davidiella macrospora and for 98% withDavidiella tassiana. Davidiella is classified within the class of theDothideomycetes (Ascomycota).The adapted ITS sequ<strong>en</strong>ce of specim<strong>en</strong> flag1115 [two thalli, DH 3H + 3I)matches for 99% with Cladosporium, a member of the Dothideomycetes(Ascomycota).The adapted ITS sequ<strong>en</strong>ce of specim<strong>en</strong> flag1146 [two thalli, DH 15A + 15B]matches with several organisms for 97 to 99%: Cladosporium (Ascomycota,Dothideomycetes), Davidiella (Ascomycota, Dothideomycetes), Choiromyces(Ascomycota, Pezizomycetes) and Dioscorea (Spermatophyta).The adapted ITS sequ<strong>en</strong>ce of specim<strong>en</strong> flag1152 [thallus DH 16C] matches for99% with Pichia sp., for 93% with Pichia castillae and media and for 90% withPichia stipitis (but with query coverage of 100%). Furthermore, the sequ<strong>en</strong>cematches for 91% with Candida ferm<strong>en</strong>ticar<strong>en</strong>s and for 90-92% withDebaryomyces. All hits – Pichia, Candida, Debaryomyces – belong to theSaccharomycetes (Ascomycota).Table X: Top matches with G<strong>en</strong>Bank for specim<strong>en</strong>s amplified using primers ITS5 andITS4-A. Specim<strong>en</strong>s id<strong>en</strong>tified only to g<strong>en</strong>us level were immature.Specim<strong>en</strong> Species Protocol L<strong>en</strong>gth Comparison G<strong>en</strong>Bank Refer<strong>en</strong>celabo1111 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia sp. I 595flag1115 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata I 598flag1126 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata III 608flag1129 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata III 608labo1131 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia sp. IV 608labo1132 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia sp. IV 607Davidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaCladosporium sp.Cladosporium cladosporioidesDavidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaDavidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaDavidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaDavidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassiana-a-b-a-a-a-aP a g e | 39

coll1133 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia collae IV 608labo1136 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia sp. V 608flag1137 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata V 608flag1141 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata V 609flag1146 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata II 505flag1152 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata II 691Davidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaDavidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaDavidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaDavidiella macrosporaDavidiella tassianaCladosporium cladoporioidesCladosporium sp.Choiromyces v<strong>en</strong>osusDavidiella tassianaDioscorea polystachyaCladosporium ossifragaPichia sp.Pichia castillaePichia mediaPichia stipitisCandida ferm<strong>en</strong>ticar<strong>en</strong>sDebaryomyces hans<strong>en</strong>iiDebaryomyces pseudopolymorphus-a-a-a-a-cde-f-ggh-i-[a SIMON & WEISS, 2008; b BRAUN et al, 2003; c WIRSEL et al., 2002; d FERDMAN et al., 2005; e BUKOVSKA et al., 2010; fSCHUBERT et al., 2007; g VILLA-CARVAJAL et al., 2006; h JEFFRIES et al., 2007; i ARTEAU et al., 2010.]3.2.2. PRIMER PAIR ITS5/ITS2The adapted ITS sequ<strong>en</strong>ce of specim<strong>en</strong> flag1151 [thallus, DH 16B) matches for92% with Myc<strong>en</strong>a amabilissima (Basidiomycota, Agaricomycetes).Table XI: Top matches with G<strong>en</strong>Bank for specim<strong>en</strong>s amplified using primers ITS5 and ITS2Specim<strong>en</strong> Species Protocol L<strong>en</strong>gth Comparison G<strong>en</strong>Bank Refer<strong>en</strong>ceflag1151 Laboulb<strong>en</strong>ia flagellata II 359 Myc<strong>en</strong>a amabilissima a[a MATHENY et al., 2006.]P a g e | 40