Islam in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives - Islamic Books ...

Islam in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives - Islamic Books ...

Islam in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives - Islamic Books ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

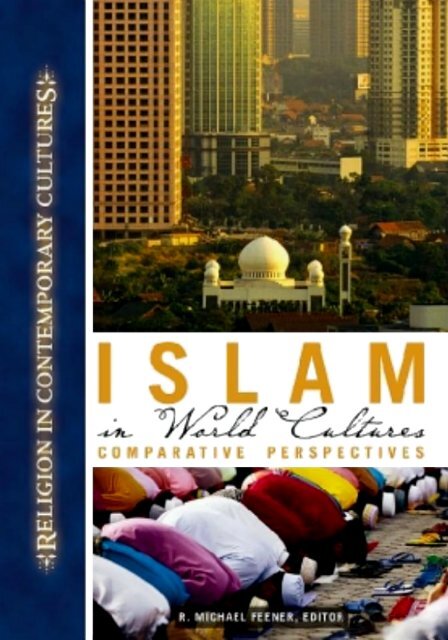

<strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>World</strong> <strong>Cultures</strong>

<strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>World</strong> <strong>Cultures</strong><strong>Comparative</strong> <strong>Perspectives</strong>Edited byR. MICHAEL FEENERSanta Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England

Copyright 2004 by R. Michael FeenerAll rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored <strong>in</strong> a retrieval system, or transmitted, <strong>in</strong> any form or by any means, electronic,mechanical, photocopy<strong>in</strong>g, record<strong>in</strong>g, or otherwise,except for the <strong>in</strong>clusion of brief quotations <strong>in</strong> a review,without prior permission <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g from the publishers.Library of Congress Catalog<strong>in</strong>g-<strong>in</strong>-Publication Data<strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> world cultures : comparative perspectives /R. Michael Feener, editor.p. cm.Includes bibliographical references and <strong>in</strong>dex.ISBN 1-57607-516-8 (hardback : alk. paper)ISBN 1-57607-519-2 (e-book)1. <strong>Islam</strong>—21st century. 2. <strong>Islam</strong> and civil society.3. <strong>Islam</strong> and state—<strong>Islam</strong>ic countries. 4. <strong>Islam</strong>ic countries—Civilization—21st century.I. Feener, R. Michael.BP161.3.I74 2004297’.09—dc22200401739708 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1This book is also available on the <strong>World</strong> Wide Web as an e-book.Visit abc-clio.com for details.ABC-CLIO, Inc.130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911This book is pr<strong>in</strong>ted on acid-free paper.Manufactured <strong>in</strong> the United States of America

For Mom and Dad,with love and gratitude

ContentsC o n t r i bu to r s,ix<strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>World</strong> <strong>Cultures</strong><strong>Comparative</strong> <strong>Perspectives</strong>Chapter One<strong>Islam</strong>: Histo r i cal Introduction and O verv i e wR. Michael Feener, 1Chapter Two<strong>Islam</strong> after Empire: Turkey and the Arab Middle EastGregory Starrett, 41Chapter ThreeShi’ite <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> Contemporary Iran:F rom <strong>Islam</strong>ic Revolution to Moderat<strong>in</strong>g ReformDavid Buchman, 75Chapter FourD e bat<strong>in</strong>g Ort h o d ox y, Contest<strong>in</strong>g Tr a d i t i o n :<strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> Contemporary South AsiaRobert Rozehnal, 103Chapter Five<strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> Contemporary Central AsiaAdeeb Khalid, 133Chapter Six<strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a: Accommodation or Sepa r at i s m ?Dru C. Gladney, 161v i i

v i i iC o n t e n t sChapter SevenMuslim Thought and Practice <strong>in</strong> Contemporary IndonesiaAnna Gade and R. Michael Feener, 183Chapter EightReligion, Language, and Nationalism: Harari Muslims <strong>in</strong>Christian EthiopiaTim Carmichael, 217Chapter N<strong>in</strong>eR ace, Ideology, and <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> Contemporary South AfricaAbdulkader Tayob, 253Chapter TenPeril and Possibility: Muslim Life <strong>in</strong> the United Stat e sEdward E. Curtis IV, 283Chapter ElevenSuggestions for Further Read<strong>in</strong>gand Internet Resourc e s, 309Chapter TwelveKey Te r m s, 337I n d e x, 361

ContributorsDavid Buchman is a cultural anthropologist who has traveled throughoutthe Middle East pursu<strong>in</strong>g the study of Arabic, Persian, <strong>Islam</strong>, and the statusof contemporary Sufism. He is an assistant professor of anthropology andMiddle East studies at Hanover College <strong>in</strong> Indiana, and his publications<strong>in</strong>clude a translation of Abu Hamid al-Ghazali’s (d. 1111) work Mishkat al-Anwar (Niche of the Lights, 1999).Tim Carm i c h a e l teaches African History at the College of Charleston(South Carol<strong>in</strong>a). He is onl<strong>in</strong>e editor of H-Africa, associate editor of NortheastAfrican Studies, and coeditor of Personality and Political Culture <strong>in</strong> ModernA f r i c a (1998). His publications focus on <strong>Islam</strong>, politics, and culture <strong>in</strong>Ethiopia, Kenya, and Yemen.Edward E. Curtis IV is assistant professor of religious studies at the Universityof North Carol<strong>in</strong>a, Chapel Hill, and author of <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> Black America(2002). He offers courses <strong>in</strong> both <strong>Islam</strong>ic studies and African American religionsand is currently at work on a history of religious life <strong>in</strong> ElijahM u h a m m a d ’s Nation of <strong>Islam</strong>. He holds a doctorate <strong>in</strong> religious studiesfrom the University of South Africa.R. Michael Feener teaches religious studies and Southeast Asian studies atthe University of California, Riverside. His research covers aspects of <strong>Islam</strong><strong>in</strong> Southeast Asia and the Middle East from the early modern to the conte m p o r a ry periods. He has published articles on topics rang<strong>in</strong>g fromQur’anic exegesis to Sufi hagiography, and he is currently complet<strong>in</strong>g workon a monograph trac<strong>in</strong>g the development of Muslim legal thought <strong>in</strong> twentieth-centuryIndonesia.Anna M. Gade is assistant professor of religion at Oberl<strong>in</strong> College. She specializes<strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong>ic traditions and religious systems of Southeast Asia and isthe author of P e rfection Makes Practice: Learn<strong>in</strong>g, Emotion, and the RecitedQur’an <strong>in</strong> Indonesia (2004).Dru C. Gladney is professor of Asian studies and anthropology at the Universityof Hawai‘i at Manoa. His books <strong>in</strong>clude Muslim Ch<strong>in</strong>ese: Ethnic Nationalism<strong>in</strong> the People’s Republic (1991); Mak<strong>in</strong>g Majorities: Compos<strong>in</strong>g the Nation<strong>in</strong> Japan, Ch<strong>in</strong>a, Korea, Malaysia, Fiji, Turkey, and the U.S. (1998); Ethnici x

xC o n t r i bu to r sIdentity <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a: The Mak<strong>in</strong>g of a Muslim M<strong>in</strong>ority Nationality (1998); and Dislocat<strong>in</strong>gCh<strong>in</strong>a: Muslims, M<strong>in</strong>orities, and Other Sub-Altern Subjects (<strong>in</strong> press).Adeeb Khalid is associate professor of history at Carleton College. He is theauthor of The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform: Jadidism <strong>in</strong> Central Asia(1998) and is currently work<strong>in</strong>g on a book on the multifaceted transformationof Central Asia <strong>in</strong> the early Soviet period.Robert Rozehnal is assistant professor <strong>in</strong> the Department of Religion Studiesat Lehigh University. He holds a Ph.D. <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong>ic studies from DukeUniversity and an M.A. <strong>in</strong> South Asian studies from the University of Wiscons<strong>in</strong>–Madison.In addition to the history and practice of Sufism <strong>in</strong> SouthAsia, his research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude ritual studies, postcolonial theory, andreligious nationalism.G re g o ry Starrett is associate professor of anthropology at the University ofNorth Carol<strong>in</strong>a at Charlotte. A graduate of Stanford University, he has writtenabout <strong>Islam</strong>ic literature, ritual <strong>in</strong>terpretation, public culture, and religiouscommodities <strong>in</strong> Egypt and the United States. His book Putt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Islam</strong> toWork: Education, Politics, and Religious Tr a n s f o rmation <strong>in</strong> Egypt (1998) exam<strong>in</strong>esthe historical and contemporary use of religious education programs <strong>in</strong>public schools and their connection to <strong>Islam</strong>ist political movements. Currentresearch projects address religious violence, the cultural and symbolicelements of national security, and the globalized production and consumptionof <strong>Islam</strong>ic <strong>in</strong>tellectual goods, focus<strong>in</strong>g on African American Muslims.Abdulkader Tayob has worked on the history of <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> the modern period<strong>in</strong> general and <strong>in</strong> South Africa <strong>in</strong> particular. He has published on theyouth, religion, and politics dur<strong>in</strong>g the apartheid and postapartheid eras.Presently, he is based at the International Institute for the Study of <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong>the Modern <strong>World</strong> and is work<strong>in</strong>g on modern <strong>Islam</strong>ic identity and publiclife <strong>in</strong> Africa. His major publications <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>Islam</strong>ic Resurgence <strong>in</strong> SouthAfrica (1995); <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> South Africa: Mosques, Imams, and Sermons (1999); and<strong>Islam</strong>, a Short Introduction (1999).

Chapter One<strong>Islam</strong>Historical Introduction and OverviewR. MI C H A E L F E E N E RFor many people <strong>in</strong> the United States, the dramatic and tragic events of andfollow<strong>in</strong>g September 11, 2001, seem to have exploded <strong>in</strong>to the world fromout of nowhere. Over the weeks and months that followed, a new awarenessof the roles of <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> countries rang<strong>in</strong>g from Afghanistan to the Philipp<strong>in</strong>esbegan to emerge. However, <strong>in</strong> the process, phenomena that have only recentlycome <strong>in</strong>to ma<strong>in</strong>stream American public consciousness via mass mediacoverage are often presented there without the k<strong>in</strong>d of background materialsthat are helpful <strong>in</strong> analyz<strong>in</strong>g and understand<strong>in</strong>g such developments. Popularmedia reportage can only go so far <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g contexts for understand<strong>in</strong>gcurrent events <strong>in</strong> different societies around the world. The chapters <strong>in</strong> thisbook attempt to provide a deeper ground<strong>in</strong>g for discussions of contemporaryMuslim societies.This short volume can provide only a critical selection of studies rather thancomprehensive coverage of all Muslim societies. Thus we have been unable to<strong>in</strong>clude, for example, chapters on western Africa or eastern Europe. Nevertheless,the <strong>in</strong>-depth explorations of the societies that are discussed here can serv eas <strong>in</strong>troductions to the complexities of contemporary <strong>Islam</strong> as it is lived byMuslims <strong>in</strong> local as well as global contexts. In their discussions of race, language,politics, and piety <strong>in</strong> diverse Muslim societies, these chapters br<strong>in</strong>g tolight some of the most consequential issues affect<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>terpretations of <strong>Islam</strong>and the experiences of Muslims <strong>in</strong> the modern world. In this <strong>in</strong>troductionI will present an overview of <strong>Islam</strong> that highlights earlier historical developmentsthat have shaped the tradition for centuries and that cont<strong>in</strong>ue to <strong>in</strong>formdebates and discussions <strong>in</strong> many Muslim societies today.1

2<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e sMuhammad and the Rise of <strong>Islam</strong><strong>Islam</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> the Mediterranean region <strong>in</strong> late antiquity (circa 250–700C.E.). Its found<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> seventh-century Arabia took place <strong>in</strong> a society that wascom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g contact with elements of Greek culture as well as withreligious ideas from Judaism, Christianity, and other faiths. Though <strong>Islam</strong>shares much with the cultural legacy of the West, it has spread far beyond itsregion of orig<strong>in</strong>. As it spread, it carried with it not only the idea of monotheismbut also Aristotelian philosophy and tales of Alexander the Great far <strong>in</strong>toAfrica and Asia. To d a y, <strong>Islam</strong> is a religion with over a billion adherents, andMuslims constitute major segments of the population <strong>in</strong> countries rang<strong>in</strong>gfrom Mali to Malaysia. It is also one of the three monotheistic religious traditionsthat are sometimes collectively referred to as the “Abrahamic” religions.Like Judaism and Christianity, <strong>Islam</strong> acknowledges a spiritual l<strong>in</strong>eage throughAbraham and teaches that one God has communicated to humanity through asuccession of prophets.Muhammad, the Prophet of <strong>Islam</strong>, lived <strong>in</strong> the Arabian pen<strong>in</strong>sula, mostly <strong>in</strong>the two towns of Mecca and Med<strong>in</strong>a, from approximately 570 to 632 C.E. F o rthe last 1,400 years, he has been regarded by his followers as the last and greatestof God’s prophets <strong>in</strong> a l<strong>in</strong>e that stretches back through Jesus and Moses toAdam. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Muslim tradition, Muhammad was orphaned at an earlyage and raised under the protection of one of his uncles. As a young man, hedeveloped a reputation for s<strong>in</strong>cerity and trustworth<strong>in</strong>ess while work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> thecamel-caravan trade based <strong>in</strong> Mecca. He eventually attracted the attention ofand married Khadija, a wealthy woman some fifteen years his senior. Until shedied, Muhammad married no other woman, and Khadija served as a source oftremendous support for him, even <strong>in</strong> the most try<strong>in</strong>g of times.It was Khadija who comforted and reassured Muhammad after he returnedhome <strong>in</strong> a frantic state from one of his visits to a cave outside Mecca where hewas accustomed to seek solitude and meditate. On that day, Muslims believe,Muhammad was visited by the angel Jibril (Gabriel), who revealed to him thefirst verses of the Qur’an. As the div<strong>in</strong>ely chosen recipient of this prophecy,Muhammad came to speak the very word of God. However, Muhammad is notdeified <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong>, and he is not worshipped by Muslims. The <strong>Islam</strong>ic traditioncomb<strong>in</strong>es an <strong>in</strong>tense love, respect, and desire to emulate Muhammad’s behaviorwith an acknowledgment of the Prophet’s humanity. Fitt<strong>in</strong>gly, Muhammadhimself is believed to have said that the only miracle God granted him was therevelation of the Qur’an.Muslims hold the Qur’an to be the word of God, revealed progressively <strong>in</strong>human history <strong>in</strong> verses that responded to the chang<strong>in</strong>g contexts of Muhammad’sprophetic mission over the course of twenty-two years. S<strong>in</strong>ce the earliestdays of <strong>Islam</strong>, although theological debates have been waged over the “un-

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 3created” nature of the Qur’an, many Muslims have acknowledged some aspectsof the historicity of their sacred text. One of the major arenas for thisdiscussion was the traditional practice of Qur’anic <strong>in</strong>terpretation that exam<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>in</strong>dividual verses <strong>in</strong> relation to specific events recorded <strong>in</strong> the biographyof Muhammad (asbab al-nuzul). Traditional Muslim scholars have also ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>edthat the current written text of the Qur’an was not set before the deathof the Prophet. Muslim tradition ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s that the verses recited by Muhammadwere written down only after his death by his companion Zayd ibnThabit and that they were not arranged <strong>in</strong>to what became their standard orderuntil the caliphate of Uthman (644–656). Even after that, variant read<strong>in</strong>gspersisted and have been regarded as acceptable by the communitythroughout the subsequent centuries of Muslim history. Thus, throughoutthe ages, Muslims have not been averse to an acknowledgment of changewith<strong>in</strong> the tradition, even at its very core. In fact, it could be argued that untilthe modern period, such issues have been less problematic for <strong>Islam</strong> than forsome other religions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Christianity. In the twentieth century, a numberof Muslim scholars began revisit<strong>in</strong>g these traditional models of contextualQur’anic <strong>in</strong>terpretation us<strong>in</strong>g modern historical methodology to developread<strong>in</strong>gs of the Qur’an resonant with the needs of Muslims liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> contemporarysocieties.Moslems believe that the complete text of the Qur’an that we have today ismade up of collected materials revealed piecemeal over twenty-two years ofM u h a m m a d ’s life (610–632). Its verses deal with law and salvation history, andthey conta<strong>in</strong> narrative material, apocalyptic imagery, and passages of great poeticbeauty, all strung together <strong>in</strong> a way that has tended to seem jumbled, confused,and even unreadable to many Western readers—but not to Muslims oreven to many non-Muslims undergo<strong>in</strong>g processes of <strong>Islam</strong>ization. In fact, <strong>in</strong>many conversion narratives preserved <strong>in</strong> the classical texts of the Arabic traditionas well as <strong>in</strong> a myriad of local cultures of Africa and Asia that have embraced<strong>Islam</strong>, the sublime beauty of the Qur’anic text <strong>in</strong> Arabic has been citedas a primary motivation to conversion.In Muhammad’s day, however, not everyone <strong>in</strong> Mecca was <strong>in</strong>stantly wonover to the new faith by the beauty of the revealed verses. Muhammad’sprophetic challenge to the prevail<strong>in</strong>g norms of polytheistic Arabian society wasviewed as threaten<strong>in</strong>g by many, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Quraysh tribe, who were custodiansof the polytheistic shr<strong>in</strong>e that made Mecca a widely recognized religiouss a n c t u a ry. As Muhammad cont<strong>in</strong>ued to preach and to call for the abandonmentof this traditional cult, he faced <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g pressure from the QurayshiMeccan establishment. In 622, Muhammad moved from Mecca to the agriculturaloasis of Yathrib, later to be renamed Med<strong>in</strong>a, “city [of the Prophet].”There he was welcomed as the new leader of the community for his ability tomediate <strong>in</strong> disputes between feud<strong>in</strong>g tribes. This move, called the h i j r a <strong>in</strong> Ara-

4<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e sbic, is such an important event <strong>in</strong> the history of the Muslim community thatthe <strong>Islam</strong>ic lunar calendar starts its year one from this po<strong>in</strong>t.From his new position <strong>in</strong> Med<strong>in</strong>a, Muhammad began to spread his messageof belief <strong>in</strong> one God and the moral obligations it implied to a religious communitythat by the time of his death <strong>in</strong> 632 <strong>in</strong>cluded almost all of the Arabianpen<strong>in</strong>sula. The <strong>in</strong>itial community that Muhammad formed at Med<strong>in</strong>a compriseda confederation of Arab tribes, new Muslim converts, and Jewishgroups, all of whom had agreed to accept Muhammad’s leadership <strong>in</strong> the arbitrationof disputes among themselves and with any outside parties. This agreementwas formalized with the sign<strong>in</strong>g of the Constitution of Med<strong>in</strong>a. This remarkabletext from the lifetime of the Prophet <strong>in</strong>cludes such provisions as thisone: “The Jews of the clan of Awf are one community with the Believers (theJews have their religion and the Muslims have theirs)” (Ibn Ishaq 1997,231–233). Similar stipulations were also made for the Jews affiliated with otherlocal Arab clans.These statements are preserved <strong>in</strong> the oldest surviv<strong>in</strong>g biography ofMuhammad, that of Ibn Hisham (d. 833). As will become clear from the chaptersof this volume, discussions of such formative texts cont<strong>in</strong>ue to play importantroles <strong>in</strong> the religious lives of contemporary Muslims. For example, <strong>in</strong> a recentbook published <strong>in</strong> Jakarta, the Indonesian Muslim scholar J. SuyuthiPulungan argued that exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the relationship between the various Jewishtribes of Med<strong>in</strong>a and the Muslim community requires a renewed <strong>in</strong>vestigationof the mean<strong>in</strong>g of u m m a , “ c o m m u n i t y.” To reconcile this statement with later<strong>Islam</strong>ic tradition’s generally accepted def<strong>in</strong>ition of the u m m a as a communitybounded by religious affiliation, Pulungan makes it clear that the term u m m acan be used on two different levels simultaneously, one general and one specific,and then shows that both these understand<strong>in</strong>gs of the term have a solidfoundation <strong>in</strong> the Qur’an itself (Pulungan 1994).S<strong>in</strong>ce the late twentieth century, the Constitution of Med<strong>in</strong>a has becomethe subject of other studies around the world, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g one by the contempora ry Turkish <strong>in</strong>tellectual Ali Bulaç. He has argued that this first treaty negotiatedby the Prophet sets forth a model of <strong>in</strong>tercommunal relations based on apr<strong>in</strong>ciple of participation rather than dom<strong>in</strong>ation, “because a totalitarian orunitarian political structure cannot allow for diversities” (Quoted <strong>in</strong> Kurzman1998, 174). As the chapters that follow show, diversity is a vital issue for Muslimsnot only <strong>in</strong> their <strong>in</strong>teractions with other religious traditions but also <strong>in</strong>their management of differences with<strong>in</strong> the community of believers. Forthroughout the fourteen centuries of <strong>Islam</strong>ic history, the multiformity of <strong>in</strong>terpretationsof the Prophet’s legacy has been the central dynamic for the growthand development of the tradition. Nevertheless, most Muslims have agreedthat to a certa<strong>in</strong> extent, <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong>, the politics of communal identity are notcompletely separated from religious concerns. Muhammad comb<strong>in</strong>ed the

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 5roles of religious prophet and political leader, judg<strong>in</strong>g cases through a comb<strong>in</strong>ationof a charismatic sense of div<strong>in</strong>e guidance and an astute recognition ofthe needs and conditions of the society <strong>in</strong> which he lived.The Five Pillars of <strong>Islam</strong>Many writers, both Muslim and non-Muslim, discuss the foundational religiousduties established by <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> terms of “Five Pillars.” However, <strong>in</strong> a recent essay,Ahmet Karamustafa has called <strong>in</strong>to question the accuracy and usefulness ofthis standard model of def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>Islam</strong>. In an attempt to move beyond staticand essentializ<strong>in</strong>g formulations of <strong>Islam</strong>, he argues thatthere is utility <strong>in</strong> this formulaic def<strong>in</strong>ition, but only if it is embedded with<strong>in</strong> a civilizationalframework and used with care and caution. <strong>Islam</strong> d o e s revolve aroundcerta<strong>in</strong> key ideas and practices, but it is imperative to catch the dynamic spirit <strong>in</strong>which these core ideas and practices are constantly negotiated by Muslims <strong>in</strong>concrete historical circumstances and not to reify them <strong>in</strong>to a rigid formula thatis at once ahistorical and idealistic. (Karamustafa 2003, 108)This warn<strong>in</strong>g is important and useful and should be kept <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d as one readsboth this historical <strong>in</strong>troduction and the contextualized studies of local Muslimcommunities <strong>in</strong> the era of globalization <strong>in</strong> the chapters that follow.The first of the Five Pillars is s h a h a d a , or “witness<strong>in</strong>g” to the faith. The s h a-h a d a is more than simply a statement of belief; it also marks communal identificationthrough a ritualized speech act. The text of the s h a h a d a , spoken withproper <strong>in</strong>tention, determ<strong>in</strong>es one’s position as a member of the Muslim commu n i t y. One becomes a Muslim simply by pronounc<strong>in</strong>g, with the proper <strong>in</strong>tention,the words of an Arabic formula that translates as “There is no god butGod, and Muhammad is his messenger.” Conversion to <strong>Islam</strong> is thus rathere a s y, requir<strong>in</strong>g neither elaborate rituals nor any formal <strong>in</strong>stitutional acknowledgment.But this “simple” act of embrac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Islam</strong> implies an open-ended entry <strong>in</strong>to ongo<strong>in</strong>g processes of <strong>Islam</strong>ization that lead to the other rights and responsibilitiesoutl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g four “pillars” and <strong>in</strong> their extensiveelaborations <strong>in</strong> the development of <strong>Islam</strong>ic law over the past fourteen centuries.In the brief overview that follows, the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g four pillars are discussed<strong>in</strong> general terms, sometimes with illustrative examples from a variety ofcultural sett<strong>in</strong>gs. However, these discussions are not <strong>in</strong>tended as tests for determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g“how <strong>Islam</strong>ic” a given person or society is. Rather, they are <strong>in</strong>tendedonly as an <strong>in</strong>troduction to some of the areas of doctr<strong>in</strong>e and practice <strong>in</strong> whichMuslims have come to both def<strong>in</strong>e and debate the tradition <strong>in</strong> discussionsamong themselves and with others.

6<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e sThe second pillar of <strong>Islam</strong>, s a l a t , is the obligatory daily prayers that Muslimsp e rform at five set times each day: dawn, midday, mid-afternoon, sunset, andnight. S a l a t may be performed alone or together with others, although accord<strong>in</strong>gto Muslim tradition communal prayer is held to be more meritorious than<strong>in</strong>dividual prayer. The prayers consist of a standard set of verbal formulas recited<strong>in</strong> Arabic to which are added short read<strong>in</strong>gs from the Qur’an. TheQur’anic verses recited <strong>in</strong> the formal prayers of s a l a t are chosen either by the<strong>in</strong>dividual, if he or she is pray<strong>in</strong>g alone, or by the leader of the group at prayer.This prayer leader is often referred to as an imam, and <strong>in</strong> this sense an imam isnot an officer of any organized clergy. In fact, <strong>in</strong> many Muslim communitiesthe leadership of communal prayer rotates among different <strong>in</strong>dividuals withoutany of them hav<strong>in</strong>g any officially orda<strong>in</strong>ed status. Furthermore, <strong>in</strong> groupsspontaneously formed by Muslims who just happen to f<strong>in</strong>d themselves togetherat prayer time, polite arguments can arise as each tries to persuade anotherto take up the honor of lead<strong>in</strong>g the prayer. However, the position ofimam can take on more <strong>in</strong>stitutional associations, particularly <strong>in</strong> North America,where Muslim communities have been organiz<strong>in</strong>g themselves <strong>in</strong> waysthat—largely un<strong>in</strong>tentionally—follow the models of parishes and congregationsthat exist <strong>in</strong> this particular cultural sett<strong>in</strong>g.H o w e v e r, beyond such local contexts, salat can also function to create asense of unity across the global Muslim community, bridg<strong>in</strong>g space and shap<strong>in</strong>gtime <strong>in</strong> the day-to-day lived experience of <strong>Islam</strong>. At each prayer time, Muslimswho do pray face Mecca, each look<strong>in</strong>g toward the same reference po<strong>in</strong>tregardless of whether they are to the west, east, north, or south of Arabia. Furthermore,wherever they are, Muslims around the world often break up theirday accord<strong>in</strong>g to the rhythms of prayer. And <strong>in</strong> some places, such as Yemen, <strong>in</strong>formalappo<strong>in</strong>tments and meet<strong>in</strong>gs with friends are often scheduled not bythe hours of the clock, such as “for 4:00 P.M.” but, rather, by the times of thedaily prayers, such as “after mid-afternoon prayers, God will<strong>in</strong>g.”The ultimate reliance on God’s will expressed <strong>in</strong> such statements shouldnot, however, lead us to th<strong>in</strong>k that Muslims are passive recipients of div<strong>in</strong>elydecreed fate. For the sense of moral responsibility and the requirement to act<strong>in</strong> this world are crucial aspects of Muslim religious life. Indeed, the third pillarof <strong>Islam</strong>, z a k a t (almsgiv<strong>in</strong>g), is l<strong>in</strong>ked explicitly to the performance of s a l a t<strong>in</strong> the Qur’an and is centrally concerned with Muslims’ real-world responsibilitiesfor the welfare of their communities. Zakat <strong>in</strong>volves the redistribution ofthe material resources of Muslim communities for the physical and social benefitof the public at large.Muslims who have more than they need for basic subsistence are obliged togive a portion of their surplus for the good of their neighbors. Thus, z a k a tmight be seen as form<strong>in</strong>g a complementary, “horizontal” axis of Muslim pietyto the “vertical” orientation of salat. This metaphor reflects a traditional Mus-

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 7lim paradigm of view<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Islam</strong> <strong>in</strong> terms of two related sets of obligations:those to God (hablun m<strong>in</strong> Allah) and those to one’s fellow human be<strong>in</strong>gs(hablun m<strong>in</strong> al-nas). It is <strong>in</strong> the latter that one can most clearly recognize someth<strong>in</strong>gof the potential social import of zakat for Muslim societies. In fact, s<strong>in</strong>cethe 1990s, progressive re<strong>in</strong>terpretations of zakat have been advanced by suchMuslim th<strong>in</strong>kers as the Indonesian Masdar F. Mas’udi <strong>in</strong> attempts to realizethe potential of this third pillar of <strong>Islam</strong> as an <strong>in</strong>strument of social justice(Mas’udi 1993).The actual transferal of resources associated with z a k a t are guided by a complexof <strong>Islam</strong>ic legal rul<strong>in</strong>gs and also vary accord<strong>in</strong>g to local practice across differentMuslim societies. In many communities, however, Muslims make a paymentof z a k a t dur<strong>in</strong>g the last days of the <strong>Islam</strong>ic lunar month of Ramadhan.That month is also the annual occasion for observ<strong>in</strong>g the fourth pillar of <strong>Islam</strong>,s a w m . At a m<strong>in</strong>imum, s a w m entails absta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g from all food, dr<strong>in</strong>k, andother physical pleasures such as smok<strong>in</strong>g and sex from sunrise to sunset eachday of the month of Ramadhan. Beyond this, however, most Muslims stress the<strong>in</strong>terior dimensions of the fast as be<strong>in</strong>g just as important as the physical discipl<strong>in</strong>e.For example, one will often hear Muslim sermons dur<strong>in</strong>g Ramadhanthat expound upon the need to control one’s emotive states as much as one’ssensual appetites—especially s<strong>in</strong>ce some people may be a bit crankier thanusual due to hunger or caffe<strong>in</strong>e deprivation.Despite such restrictions, however, Ramadhan is a very special time <strong>in</strong> Muslimcommunities, an occasion for both pious devotion and pleasant camaraderie.After sunset each day, people gather <strong>in</strong> homes and mosques to breakthe fast together. These nightly communal meals are often followed by prayers,read<strong>in</strong>gs from the Qur’an, and discussions of religious and other topics, althoughthe foods eaten and the nature of conversations vary considerablyacross Muslim communities. The end of Ramadhan is marked with great celebration,with round after round of visits and feast<strong>in</strong>g with family and friendsbeg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g immediately after prayers on the first morn<strong>in</strong>g of the next month.These end-of-Ramadhan celebrations are one of the two major annual festivalsof the <strong>Islam</strong>ic lunar calendar. The other is observed at the culm<strong>in</strong>ation of theformal rites of the h a j j .H a j j , the fifth pillar, is the annual pilgrimage to Mecca dur<strong>in</strong>g the lunarmonth Dhu’l-Hijja. Muslims consider it a good th<strong>in</strong>g to visit Mecca at any timeof the year, but only a pilgrimage dur<strong>in</strong>g the appo<strong>in</strong>ted season is recognized ash a j j . For more than fourteen centuries, the annual rites of the h a j j h a v ebrought Muslims from different regions to Mecca to worship together as ac o m m u n i t y. Over the centuries, as <strong>Islam</strong> expanded beyond the Arabian pen<strong>in</strong>sulaand out of the Middle East, the pilgrimage brought together Muslimsfrom widely diverse regions and cultures, help<strong>in</strong>g foster ties between geographicallyfar-flung areas of the Muslim world and cultivat<strong>in</strong>g a sense of com-

Hundreds of thousands of Muslims bow<strong>in</strong>g their heads toward the Holy Kaaba <strong>in</strong> prayer on thestreets of Mecca, March 1, 2001. More than 2 million pilgrims were expected to perform the annualhajj that year. (Reuters/CORBIS/Adrees A. Latif)

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 9munity <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong> that ideally transcends differences of language, race, or ethni c i t y. When the African American Muslim Malcolm X performed the h a j j i n1962, he perceived it <strong>in</strong> this way. As he relates the experience <strong>in</strong> his autobiogra p h y, on his journey to Mecca he was powerfully impressed to see that his fellowpilgrims were “white, black, brown, red, and yellow people, blue eyes andblond hair, and my k<strong>in</strong>ky red hair—all together brothers! All honor<strong>in</strong>g thesame God Allah, and <strong>in</strong> turn giv<strong>in</strong>g equal honor to each other” (Malcolm X1964, 323). However, other accounts of the modern hajj stress not <strong>Islam</strong>’s universalitybut, rather, the marked differences between the different groups ofMuslims gathered there, such as <strong>in</strong> the published Letters and Memories from theHajj by the Indonesian author A. A. Navis: 1Look<strong>in</strong>g at the women from various countries here on the h a j j , one sees thateach nation has its own style of dress. In general, they cover almost their entirebody except for their faces. When they don their special pilgrim’s garb, thewomen cover their entire bodies except for their faces and the palms of theirhands. However, even <strong>in</strong> this they do not all look the same. Some wear socks, andsome do not. City girls, especially those from the chic Jakarta set, really pay attentionto their looks. Their clothes are always someth<strong>in</strong>g special, even whenthey are dressed as “humble” pilgrims. They wear special gloves that cover theirwrists, while the palms of their hands are bare, and these gloves can be lacy.Young women from other countries, even Arabs, just wear simple clothes, whichare not lacy or fancily decorated. Turkish or Iranian women wear cream-coloredblouses with long sleeves, and they also wear a triangular scarf as a form-fitt<strong>in</strong>ghead-cover<strong>in</strong>g so that no hair can become exposed. Women from central Africatend to wear colorful cloth<strong>in</strong>g. (Navis 1996, 40–41)Mecca is a sacred place for all Muslims, regardless of where they comefrom or what they are wear<strong>in</strong>g. It is the place toward which they direct thedaily prayers of s a l a t and the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad. Moreover,the rituals of the hajj po<strong>in</strong>t to even more ancient associations betweenthis Arabian town and the missions of God’s prophets, for most of the majorrites of the hajj serve as reenactments of the drama of Muslim sacred historiesof Abraham and his family, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g and near-sacrifice of his sonand the banishment of Hagar and Ishmael. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Muslim tradition,the proper performance of the rituals associated with these prophetic narrativeswere “re<strong>in</strong>stated” by Muhammad after he purified Mecca of its pagan religiouspractices from the pre-<strong>Islam</strong>ic “Age of Ignorance” (Jahiliyya). As will bediscussed below, the sense of difference constructed between Jahiliyya and <strong>Islam</strong>has become a powerful rhetorical device wielded by some modern Muslimreformists.

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 1 1ities document<strong>in</strong>g the transmission of that <strong>in</strong>formation across the generations( i s n a d ) . Dur<strong>in</strong>g the n<strong>in</strong>th century, the myriad h a d i t h that Muslims had come totransmit and discuss—a vast amount of oral material convey<strong>in</strong>g both the i s n a dand the m a t n—were written down and compiled <strong>in</strong>to a number of collections.Six of these compilations have s<strong>in</strong>ce come to be regarded as especially authoritativeby Sunni Muslims.Although some of these six books boast titles that <strong>in</strong>clude the words“sound” or “authoritative” ( s a h i h ) , throughout the centuries Muslims have cont<strong>in</strong>uedto energetically discuss this material, how the authentication of varioush a d i t h is to be evaluated, and how they are to be applied to govern<strong>in</strong>g the livesof <strong>in</strong>dividuals and the community. The early twentieth century saw a resurgenceof activity <strong>in</strong> the field of hadith criticism, especially <strong>in</strong> debates over thecriteria for determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the authenticity of hadith texts through critical exam<strong>in</strong>ationsof their cha<strong>in</strong>s of transmission (Juynboll 1969). S<strong>in</strong>ce the 1970s, howev e r, such debates on the authentication of h a d i t h have become more marg<strong>in</strong>alized<strong>in</strong> Muslim discourses. Increas<strong>in</strong>gly today, critical approaches to theauthentication of h a d i t h are met with hostility by those who adhere to modernunderstand<strong>in</strong>gs of the sunna that uncritically assert the collective “soundness”and authority of all the <strong>in</strong>dividual h a d i t h <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> collections. This phenomenonis evidenced, for example, <strong>in</strong> the grow<strong>in</strong>g number of modern Muslimpublications <strong>in</strong> Arabic and other languages that relate h a d i t h by reproduc<strong>in</strong>gm a t n while at the same time omitt<strong>in</strong>g the accompany<strong>in</strong>g i s n a d . Such texts excisethe very part of the h a d i t h that has traditionally been the focus of most activity<strong>in</strong> the field of Muslim h a d i t h criticism. The use of such publications byc o n t e m p o r a ry Muslims has contributed to important changes <strong>in</strong> popular understand<strong>in</strong>gsof the sources of the tradition and <strong>in</strong> the way the Prophet’s teach<strong>in</strong>gsare understood and <strong>in</strong>terpreted <strong>in</strong> many parts of the world today.<strong>Islam</strong> after Muhammad: Political Succession andthe Formation of TraditionM u h a m m a d ’s charismatic career of religious, social, political, and militaryleadership was so remarkable that when he died, it is said, some of his followerscould not believe he was mortal. The tradition records, however, that whenhis oldest companion, Abu Bakr, publicly announced the pass<strong>in</strong>g of theProphet, he said, “Oh people, those who worshipped Muhammad [must knowthat] Muhammad is dead; those who worshipped God [must know that] Godis alive [and] immortal” (al-Tabari 1990, 185). In this, we have a crystall<strong>in</strong>e expressionof what was undoubtedly the resolution of a much larger and moreambiguous dilemma centered on how, if at all, the movement was to cont<strong>in</strong>ueafter the Prophet’s death and who would lead the Muslim community as his

1 2<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e ss u c c e s s o r. Most Muslims were conv<strong>in</strong>ced that Muhammad had died not onlywithout leav<strong>in</strong>g sons but also without mak<strong>in</strong>g any clear and undisputed statementon who was to succeed him or how the community was to be governed.Some, however, contended that <strong>in</strong> fact Muhammad had appo<strong>in</strong>ted a successor<strong>in</strong> a statement he made at Ghadir Khumm. This group claimed that theProphet had designated his cous<strong>in</strong> and son-<strong>in</strong>-law Ali ibn Abi Talib to take hisplace as leader of the community. Those who argued for Ali as successor wereto become known as the Shi’a (“partisans [of Ali]”), who have rema<strong>in</strong>ed a m<strong>in</strong>ority<strong>in</strong> the broader Muslim population to this day.Most Muslims, however, rejected these arguments for determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Muhamma d ’s successor, contend<strong>in</strong>g that they had not been present at Ghadir Khummand that they did not believe the event even took place. Thus they saw no reasonto submit to Ali’s leadership and <strong>in</strong>stead were left to f<strong>in</strong>d other ways to determ<strong>in</strong>ethe succession to Muhammad. Furthermore, some who had <strong>in</strong>itiallysupported Ali’s leadership of the community became disillusioned and split toform their own community, and they have come to be known as the Kharijites.The divisions between these various groups did not disappear when the immediatepolitical struggles were resolved. Instead, the groups cont<strong>in</strong>ued alongparallel historical tracts, develop<strong>in</strong>g complex elaborations of ideas on the religiousimplications of their political histories and sometimes divid<strong>in</strong>g even furtheramong themselves over variant <strong>in</strong>terpretations of these developments.To d a y, Shi’ites form a rul<strong>in</strong>g majority <strong>in</strong> Iran, and their place <strong>in</strong> the adm<strong>in</strong>istrationof a post–Saddam Husse<strong>in</strong> Iraq—where they also form a demographicmajority—is yet to be determ<strong>in</strong>ed. Most Shi’ites <strong>in</strong> both of those countriesare of the Ithna’ashirite sect, which acknowledges a succession of twelvespiritual leaders (also referred to as imams) <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>in</strong>e of Ali. This group comprisesthe largest number of Shi’ites <strong>in</strong> the world today. However, there arealso a number of other Shi’ite groups, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Zaydis and variousbranches of the Isma’ilis, who comprise significant (but mostly m<strong>in</strong>ority) segmentsof the Muslim populations of Yemen, Pakistan, India, and a number ofcountries <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa. In East Africa, one f<strong>in</strong>ds populations of Ibadisas well, latter-day followers of the Kharijites who also form a rul<strong>in</strong>g majority <strong>in</strong>c o n t e m p o r a ry Oman.H o w e v e r, throughout the history of <strong>Islam</strong>, the majority of Muslims were notKharijites or Shi’ites of any type. Rather, they were of the orientation that latercame to refer to itself as “Sunni,” or more properly, the ahl al-sunna wa’l-jama’a,“people of the way [of the Prophet] and the community.” The Sunnis determ<strong>in</strong>edsuccession to leadership of the community not through familial descentbut through a consensus of the leaders of the community. The first foursuccessors chosen <strong>in</strong> this way were all personal friends and companions ofMuhammad, and with<strong>in</strong> the tradition, they came to be referred to collectivelyas the four “rightly guided caliphs.”

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 1 3When the third of these caliphs, Uthman, was murdered while at prayer,some members of his clan sought to <strong>in</strong>stitutionalize their position by creat<strong>in</strong>gthe first hereditary rul<strong>in</strong>g dynasty of Muslim history, the Umayyad Caliphate.The Umayyads cont<strong>in</strong>ued the expansionist military campaigns of the earliercaliphs, and by the centennial anniversary of the Prophet’s death, <strong>Islam</strong>icarmies had extended their territorial control from what is today Pakistan tothe neighborhood of Paris. We should, however, be aware that these militarycampaigns were not primarily about convert<strong>in</strong>g the populations of the conqueredterritories to <strong>Islam</strong>. In fact, some of the adm<strong>in</strong>istrative and fiscal structuresof the early empire were predicated upon ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g divisions betweenthe Arab Muslim military elite and the local populations. In this situation, thenotion of preach<strong>in</strong>g the Prophet’s message as a vehicle for universal salvationseems to have been set aside, and <strong>in</strong> some places the conversion of conqueredpopulations to <strong>Islam</strong> was frankly discouraged. Under this system, theUmayyads and their associates accumulated wealth and luxury undreamed of<strong>in</strong> the Bedou<strong>in</strong> Arabia of Muhammad’s day. In this atmosphere, Muslims <strong>in</strong>their new courts and palaces sought out both the sophisticated <strong>in</strong>tellectual culturesand the more worldly luxuries of the civilizations they overran aroundthe shores of the Mediterranean.Although some enjoyed the prosperity of the caliphal empire and thewealth and power it brought, other members of the community began to voicedissatisfaction with what they viewed as corruption. In search of alternatives tothe excessive and decadent worldl<strong>in</strong>ess of the new <strong>Islam</strong>ic order under theUmayyads, some pious Muslims turned to new appreciations of <strong>Islam</strong>’s religiousheritage, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g to forms of religious asceticism. The term z u h d w a sused to refer to a range of ascetic physical discipl<strong>in</strong>es and ritual practices thatwere pursued by various groups with<strong>in</strong> the Muslim community and <strong>in</strong> particularby groups <strong>in</strong> Iraq from the early eighth century onward. Practitioners ofz u h d imag<strong>in</strong>ed that by deny<strong>in</strong>g themselves some of the physical luxuries thathad proliferated with the expansion of the <strong>Islam</strong>ic empire, they could rega<strong>in</strong>the prist<strong>in</strong>e spiritual relationship between God and humank<strong>in</strong>d that had beenrevealed through Muhammad <strong>in</strong> the Qur’an.SufismThe rise of Muslim ascetics can be viewed <strong>in</strong> relation to the development of abroader movement comprised of various traditionalist <strong>Islam</strong>ic religious groupsthat have been referred to collectively by some historians as the “pietym<strong>in</strong>ded”(Hodgson 1974, 252–256). The religious orientations represented bythese groups together formed the basis for developments <strong>in</strong> almost every fieldof <strong>Islam</strong>ic religious expression, from h a d i t h and law to Sufism, or Muslim mys-

1 4<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e sticism. Recogniz<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>terrelatedness and the overlapp<strong>in</strong>g methods of h a-d i t h s t u d y, law, and Sufism, we should be skeptical of the polemics of those whowould set up Sufis as a group separate from and <strong>in</strong> opposition to the u l a m awho specialized <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong>ic law. More often than not <strong>in</strong> the histories of Muslimsocieties, not only <strong>in</strong> the earliest days of the piety-m<strong>in</strong>ded but also <strong>in</strong> later centuries,an <strong>in</strong>dividual could be actively affiliated with both approaches to <strong>Islam</strong>s i m u l t a n e o u s l y. For example, many modern-era Muslims, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Wa h-habis of contemporary Saudi Arabia, characterize the fourteenth-century Hanbalijurist Ibn Taymiyya as the model “anti-Sufi.” However, <strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g so, theydeny much of the historical legacy of Ibn Ta y m i y y a ’s religious experience, forhe himself was a member of the Qadiriyya Sufi order, and his thought drawsconsiderably on ideas developed with<strong>in</strong> Sufi tradition (Makdisi 1974).Early Sufism can also be seen as a complex of ways Muslims have attemptedto create spaces for religion, culture, and community that would facilitate liv<strong>in</strong>gaccord<strong>in</strong>g to their understand<strong>in</strong>gs of the spirit of the Qur’an and the sunna o fthe Prophet. However, many early Western scholars of <strong>Islam</strong>—and the modernMuslim reformists with whom they sometimes have much <strong>in</strong> common—havetended to focus <strong>in</strong> their discussions of Sufism on the ideas of major Sufi authorsor ritual practices associated with organized Sufi orders. The term “Sufism” itselfthus presents some problems of <strong>in</strong>terpretation, for it has all too often beenused <strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>ately to refer to phenomena rang<strong>in</strong>g from mystical poetry andphilosophical cosmology to the folk practices of shr<strong>in</strong>e veneration.One way to beg<strong>in</strong> to understand the complexity of Sufism <strong>in</strong> Muslim societiesis through a historical approach to the growth and development of Sufism’s varioustraditions. Over the course of the n<strong>in</strong>th and tenth centuries, Sufism experiencedrapid developments that dist<strong>in</strong>guished it from the z u h d movement. In theprocess, Sufi teach<strong>in</strong>gs came to be def<strong>in</strong>ed accord<strong>in</strong>g to certa<strong>in</strong> schemes of systematization.This occurred first on a textual level as various Muslim writers triedto arrange their thoughts on mystical experience and a deepen<strong>in</strong>g relationshipto God <strong>in</strong> coherent, codified writ<strong>in</strong>gs. The <strong>in</strong>stitutional level eventually developedanalogously, as the transmission of various ways (t a r i q as) of teachers(s h a y k hs) more advanced on the spiritual path of Sufism became <strong>in</strong>stitutionalizedfor the <strong>in</strong>struction and benefit of their pupils and spiritual descendants.In some Sufi traditions, these cha<strong>in</strong>s of successive teachers and students <strong>in</strong>cludewomen as well as men. Wo m e n ’s place <strong>in</strong> this history is recorded <strong>in</strong> medievalbiographical dictionaries that conta<strong>in</strong> entries on women such as Fatimab<strong>in</strong>t Abbas, a fourteenth-century scholar who was described by Abd al-Ra’uf al-Munawi (d. 1621) aslearned <strong>in</strong> the recondite <strong>in</strong>tricacies and most vex<strong>in</strong>g questions of f i q h . I b nTaymiyya and others were impressed with her knowledge and unst<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> theirpraise of her brilliance, [and] her humility. . . . The swells of the ocean of her

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 1 5learn<strong>in</strong>g roiled and surged. Her be<strong>in</strong>g a woman stood out <strong>in</strong> [people’s] mentionof her, but awareness of [that fact] was no detriment to her reputation. (Quoted<strong>in</strong> Renard 1998, 288)The <strong>in</strong>stitutional forms and sets of ritual practices transmitted across some networksof Sufi students and teachers eventually took on the form of organizedorders—also referred to <strong>in</strong> Arabic as t a r i q as and often named after the purportedfound<strong>in</strong>g s h a y k h . From the twelfth century on, various t a r i q as createdcommunities of Muslims centered on forms of association and ritual practicethat <strong>in</strong>stitutionalized the teach<strong>in</strong>gs of particular s h a y k hs. The number of organizedSufi orders grew steadily, and many spread far from their local po<strong>in</strong>tsof orig<strong>in</strong> to establish branches throughout the Muslim world from NorthAfrica to Southeast Asia.In addition to the organized orders, there were also less-<strong>in</strong>stitutionalizedSufi schools of thought cover<strong>in</strong>g ritual practices and devotional exercises, andthere were complex <strong>in</strong>tellectual formulations by figures such as the thirteenthce n t u ry scholar of Muslim Spa<strong>in</strong>, Ibn Arabi. Ibn Arabi is one of the most controversialfigures <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong>ic history, and debates over his legacy often extendbeyond the polemics of Sufism to <strong>in</strong>corporate aspects of theology and philosoph y. Many of Ibn Arabi’s later Muslim detractors attacked him for espous<strong>in</strong>g amodel of the relationship between God and humank<strong>in</strong>d that they saw as dangerous,potentially lead<strong>in</strong>g to the improper effacement of the dist<strong>in</strong>ction betweencreation and its Creator. Despite such criticisms, the thought of IbnArabi was never universally condemned by all Muslims. Even <strong>in</strong> the modernperiod, there was a renaissance of <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> his work among scholars such asthose associated with the Akbariyya of late n<strong>in</strong>eteenth-century Damascus. Abdal-Qadir al-Jaza’iri, a major figure <strong>in</strong> those circles, found <strong>in</strong> Ibn Arabi’s thoughttools for deal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> dynamic ways with the challenges of rationalism andmodernity posed by the grow<strong>in</strong>g cultural and political hegemony of the We s t( Weismann 2001, 141–224).<strong>Islam</strong>ic PhilosophyThe orig<strong>in</strong>s of <strong>Islam</strong>ic philosophy can be traced to the vibrant and cosmopolitan<strong>in</strong>tellectual atmosphere of the early Abbassid Caliphate at Baghdad(750–991), when the Arabic translation movement was <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g texts fromclassical Greek, Christian, and other “foreign” literatures <strong>in</strong>to the conversationsof educated Muslims. This material was selectively <strong>in</strong>terpreted and represented<strong>in</strong> ways that seemed to address the concerns and <strong>in</strong>terests of variousgroups of Muslims at that time. In the n<strong>in</strong>th century, Muslim “free th<strong>in</strong>kers,”such as Ibn al-Rawandi and Abu Bakr al-Razi, dove <strong>in</strong>to the pre-Christian phi-

1 6<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e sMuslim mystics <strong>in</strong> the modern world; at a Sufi shr<strong>in</strong>e outside Cape Town, South Africa.(R. Michael Feener)losophy of the ancient Greeks, sometimes plac<strong>in</strong>g themselves <strong>in</strong> open conflictwith the central conceptions of the religious authority <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong> (Stroumsa1999). Others, such as the eleventh-century philosopher Ibn S<strong>in</strong>a (d. 1037;known <strong>in</strong> the West by the Lat<strong>in</strong>ate name Avicenna), worked to <strong>in</strong>tegrate certa<strong>in</strong>aspects of Greek philosophical method <strong>in</strong>to complex systems of <strong>Islam</strong>ic

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 1 7religious thought. With the work of the <strong>Islam</strong>ic philosophers, new issues cameto the fore <strong>in</strong> debates over the relative authority of human reason and div<strong>in</strong>erevelation <strong>in</strong> human knowledge. These discussions cont<strong>in</strong>ued to develop overthe centuries under the leadership of Muslim th<strong>in</strong>kers such as Ibn Rushd (d.1198; known <strong>in</strong> the West as Av e r r o ë s ) .Many Western histories have appreciated the medieval Muslim philosophersfor their role <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g and transmitt<strong>in</strong>g to late-medieval and RenaissanceEurope the thought of Aristotle and other Greek philosophers,whose <strong>in</strong>tellectual heritage had largely been lost to Europe dur<strong>in</strong>g the darkdays of the Middle Ages. However, the medieval Muslim philosophers are alsoimportant <strong>in</strong> their own right for their role <strong>in</strong> the history of <strong>Islam</strong>. Withouttheir valuable contributions to knowledge, the famed accomplishments of medievalMuslims <strong>in</strong> science, medic<strong>in</strong>e, ethics, and political thought would nothave been possible. S<strong>in</strong>ce the 1980s, the Moroccan Muslim philosopher MohammedAbed al-Jabri has called for a radical reappraisal of this rich tradition—notas a historical legacy to be transmitted as an <strong>in</strong>ert artifact but, rather,as a spirit of rationality and realism that he identifies with the work of IbnRushd. Al-Jabri sees such a reappraisal as the best way to reanimate <strong>Islam</strong>ic <strong>in</strong>tellectualism<strong>in</strong> order to meet the new challenges and opportunities of life <strong>in</strong>the contemporary world (Al-Jabri 1999).<strong>Islam</strong>ic TheologyIn the <strong>in</strong>tellectual history of <strong>Islam</strong>, not all Muslims have been prepared to goas far <strong>in</strong> the application of human reason to religious issues as the philosophers.However, over the centuries, some Muslim th<strong>in</strong>kers became <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>glyprepared to accept certa<strong>in</strong> aspects of the methodology of the philosophers<strong>in</strong> their studies of religious subjects, provided there was anunderstand<strong>in</strong>g that reason would, <strong>in</strong> this ve<strong>in</strong>, rema<strong>in</strong> subservient to revelation.These developments contributed to the further evolution of <strong>Islam</strong>ic theol o g y, which had begun <strong>in</strong> the eighth century with Muslim attempts to addressissues of Qur’anic <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>in</strong> debates over the relationship between theCreator (that is, God) and the created world. In the medieval period, Muslimtheologians began to address not only other Muslims but also different groupsof Christian th<strong>in</strong>kers. By this time, Christian theologians had an extensively developedtheological enterprise, which was marshaled to advance sectarian argumentsaga<strong>in</strong>st both “pagan” philosophers and Christians belong<strong>in</strong>g to other,rival churches. Muslims, <strong>in</strong> the process of develop<strong>in</strong>g their arguments—both<strong>in</strong>ternal and external—evolved their own schools of theological thought. Thefield of these debates of <strong>Islam</strong>ic theology is referred to <strong>in</strong> Arabic as k a l a m .S<strong>in</strong>ce the earliest developments of k a l a m , theological debates were often <strong>in</strong>-

1 8<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e stertw<strong>in</strong>ed with important political power plays. The most often discussed <strong>in</strong>stanceof such entanglement is the m i h n a , p e rhaps the closest parallel to theChristian Inquisition that one can f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> medieval <strong>Islam</strong>. The mihna began <strong>in</strong>the early n<strong>in</strong>th century when the caliph reign<strong>in</strong>g at Baghdad attempted to imposeone <strong>in</strong>terpretation of <strong>Islam</strong>ic theology—that of the rationalist schoolknown as the Mu’tazila—as the official doctr<strong>in</strong>e of his <strong>Islam</strong>ic empire. In attempt<strong>in</strong>gto assert his authority to determ<strong>in</strong>e religious orthodoxy, he orderedthat scholars who opposed him be stripped of their positions as teachers orjudges, and he sometimes even had the recalcitrant imprisoned and tortured(Zaman 1997, 106–118). These policies were abandoned after about twodecades, and the appeal of Mu’tazilite rationalism among Muslims was drasticallydim<strong>in</strong>ished. Subsequently, other schools of k a l a m arose, most of themplac<strong>in</strong>g more reliance on revealed knowledge than on human reason <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>Islam</strong>ic religious doctr<strong>in</strong>e. Nevertheless, <strong>in</strong> the centuries follow<strong>in</strong>g them i h n a , kalam was rarely, if ever, the primary concern of most Muslim scholars,s<strong>in</strong>ce for most of the medieval and early modern periods, theology was not asprom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong> as it was <strong>in</strong> Christianity.The relative importance of k a l a m to other areas of Muslim thought andpractice is evidenced <strong>in</strong> the work of many medieval Muslim theologians, suchas that of the fourteenth-century Central Asian scholar Sa’d al-D<strong>in</strong> al-Ta f t a z a n i ,who spoke of k a l a m as “beneficial for this world <strong>in</strong>sofar as it regulates the life[of humans] by preserv<strong>in</strong>g justice and proper conduct, both of which are essentialfor the survival of the species <strong>in</strong> ways that do not result <strong>in</strong> corruption”(quoted <strong>in</strong> Knysh 1999, 146).Thus, like Judaism, <strong>Islam</strong> has generally tended to place greater emphasis onproper conduct regulated by religious law than on the abstract formulation oforthodox dogma as the central arena of religious and <strong>in</strong>tellectual activity. Only<strong>in</strong> the twentieth century has <strong>Islam</strong>ic theology once aga<strong>in</strong> come to the fore <strong>in</strong>public debates, both <strong>in</strong>ternally between different groups of Muslims and externally<strong>in</strong> the form of apologetics explicitly or implicitly argu<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st the foilof modern Western thought.<strong>Islam</strong>ic LawAlongside Sufism, <strong>Islam</strong>ic philosophy, and k a l a m , another sphere of <strong>Islam</strong>ic religiousexpression that has been central to the historical traditions of Muslimlearn<strong>in</strong>g is law. Although the caliphates of the classical period claimed theirauthority to rule was based on succession from Muhammad, governance <strong>in</strong>their territories tended to be a cont<strong>in</strong>uation of practices long established bythe absolutist empires of the pre-<strong>Islam</strong>ic Middle East, especially Byzantiumand Sasanid Persia. Feel<strong>in</strong>g that such absolutist models of monarchy were con-

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 1 9t r a ry to the messages of humility and equality proclaimed by Muhammad,many Muslims sought rules to live by <strong>in</strong> the words of the Qur’anic revelationand the precedent of prophetic practice ( s u n n a ) . These sources were thusbrought to bear on contemporary issues <strong>in</strong> a chang<strong>in</strong>g world, and the foundationsof Muslim jurisprudence ( f i q h ) were constructed. Methodologies of legalreason<strong>in</strong>g were systematized both for <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g the legal <strong>in</strong>junctions conta<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>in</strong> scripture and for discover<strong>in</strong>g ways of arriv<strong>in</strong>g at legal decisions <strong>in</strong> themany cases for which neither the Qur’an nor the s u n n a provides a clear rul<strong>in</strong>g.By the end of the n<strong>in</strong>th century, <strong>Islam</strong>ic law was the queen of the sciences <strong>in</strong>the Muslim curriculum. By that time, a number of prom<strong>in</strong>ent teachers of Muslimjurisprudence had come to be viewed as especially authoritative, and theirteach<strong>in</strong>gs formed the bases for diverse schools of <strong>Islam</strong>ic legal thought. Eachschool ( m a d h h a b ) conceived of itself as possess<strong>in</strong>g a particularly effective modeof <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g the primary sources of <strong>Islam</strong>—the Qur’an and h a d i t h—<strong>in</strong> orderto determ<strong>in</strong>e proper human understand<strong>in</strong>g of God’s law. After the tenth centu ry, four of these schools eclipsed the others, and these four have s<strong>in</strong>ce coexistedas equally authoritative approaches to jurisprudence <strong>in</strong> Sunni <strong>Islam</strong>.Teachers of <strong>Islam</strong>ic law belong<strong>in</strong>g to one of these four schools—the Hanafi,Shafi’i, Maliki, and Hanbali—make up the u l a m a , the scholars of <strong>Islam</strong> whoare central to the transmission and development of <strong>Islam</strong>ic learn<strong>in</strong>g.For most of <strong>Islam</strong>ic history, these scholarly processes of determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the lawwere the special preserve of the u l a m a as traditionally tra<strong>in</strong>ed religious scholars.In the modern period, however, the u l a m a’s monopoly on such discussionshas been broken. In the process, many new groups and <strong>in</strong>dividuals have takenit upon themselves to write on <strong>Islam</strong>ic legal issues and even to issue their ownlegal op<strong>in</strong>ions ( f a t w a ) , whether or not they have the specialized religious tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gand traditional authority to do so. Contemporary examples of such challengesto the u l a m a’s authority run the gamut from the support for a progressiveagenda for women’s rights produced by the Malaysian group Sisters <strong>in</strong><strong>Islam</strong> to Osama b<strong>in</strong> Laden’s militant proclamations of global j i h a d .In the early centuries of <strong>Islam</strong>ic history, the law developed by the u l a m a f o rregulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual and social practice grew <strong>in</strong> popularity, and Muslim statesgranted a degree of respect and recognition to the system. However, the law of<strong>Islam</strong>—the s h a r i ’ a—was rarely the sole legal standard <strong>in</strong> <strong>Islam</strong>ic lands, and itwas applied at best selectively by most of the major Muslim empires andsmaller states. Most medieval Muslim rulers, even if they had the will to do so,were unable to establish themselves as the sole authorities and arbiters of <strong>Islam</strong>iclaw (Gerber 1999, 43–54). This situation was exacerbated by the fact thatthe <strong>in</strong>terpretation and application of <strong>Islam</strong>ic law was <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly be<strong>in</strong>g developed<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions that were outside direct state control and whose jurisdictionssometimes complemented those of civil courts, address<strong>in</strong>g different issues,and sometimes, when both venues had significant claims on a case,

2 0<strong>Islam</strong> i n <strong>World</strong> Cult u r e sconflicted with them. Consequently, for generations of <strong>in</strong>dependent Muslimreligious scholars, <strong>Islam</strong>ic law has been a powerful potential source of alternativeauthority and opposition to rul<strong>in</strong>g regimes. In the early modern period,h o w e v e r, some Muslim states (such as the Ottoman Empire) began to br<strong>in</strong>g togetherthe adm<strong>in</strong>istration of the s h a r i ’ a and the offices of the state <strong>in</strong> new ways,forg<strong>in</strong>g paths that have been further pursued <strong>in</strong> a number of Muslim societiesto this day.Religious Scholars and Institutions of Learn<strong>in</strong>gThe histories of the u l a m a have been dynamic and complex across many Muslimsocieties throughout the medieval and modern periods. Some Muslim governmentsattempted to make the u l a m a s u b s e rvient to state <strong>in</strong>terests. In otherMuslim states, the u l a m a policed their own ranks, react<strong>in</strong>g to perceived <strong>in</strong>ternaland external threats to <strong>Islam</strong>. Yet the space for <strong>in</strong>dependent thought andaction by the u l a m a never completely disappeared. This fact was remarkedupon, for example, by the eighteenth-century h a d i t h scholar Shah Wali Allahal-Dihlawi, who had studied <strong>in</strong> both India and Mecca. In a critique of what hesaw as the grow<strong>in</strong>g narrow-m<strong>in</strong>dedness of some of his fellow u l a m a , a l - D i h l a w idescribed the typical scholar of his day as “a prattler and w<strong>in</strong>d-bag who <strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>atelymemorized the op<strong>in</strong>ions of the jurists whether these were strongor weak and related them <strong>in</strong> a loud-mouthed harangue.” However, he was alsoquick to add, “I don’t say that this is so <strong>in</strong> all cases, for God has a group of Hisworshippers unharmed by their failure, who are God’s proof on earth even ifthey have become few” (quoted <strong>in</strong> Hermansen 1996, 455).A generation later, <strong>in</strong> Yemen, at least one of those “few” surviv<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>dependent-m<strong>in</strong>dedscholars whom al-Dihlawi might have thought worthy wasable not only to survive but to flourish. When Muhammad ibn Ali al-Shawkaniwas asked to accept the position of overseer of judges for the Qasimi state, heagreed to do so only when assured by the ruler that his judgments would beexecuted “whatever they may be and whomever [they concern], even if theimam himself was implicated” (quoted <strong>in</strong> Haykel 2003, 69). The cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>gpolitical and social importance of the ulama <strong>in</strong> many parts of the contempora ry Muslim world has been persuasively argued <strong>in</strong> the recent work ofMuhammad Qasim Zaman, who has noted that, for example, the number ofstudents enrolled <strong>in</strong> madrasas <strong>in</strong> the Punjab region of India has <strong>in</strong>creased bymore than a factor of ten over the past four decades (Zaman 2002, 2). This,he contends, speaks for the <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g relevance of the ulama as spokesmenfor <strong>Islam</strong>ic traditions <strong>in</strong> a world where notions of cultural authenticity havebecome global concerns.S<strong>in</strong>ce the eleventh century, u l a m a teach<strong>in</strong>g law accord<strong>in</strong>g to one of the es-

H i s to r i cal Introduction and Overv i e w 2 1Public well <strong>in</strong> the Wadi Hadhramawt, Yemen. In many parts of the Muslim world, waqf havetraditionally funded such public wells and water founta<strong>in</strong>s. (R. Michael Feener)tablished schools had come to occupy the highest positions <strong>in</strong> a new k<strong>in</strong>d ofeducational <strong>in</strong>stitution that was to spread from Baghdad throughout the Muslimworld—the m a d r a s a . The earliest m a d r a s as were established for the teach<strong>in</strong>gof <strong>Islam</strong>ic law accord<strong>in</strong>g to one of the established Sunni schools (Makdisi1961). By the fourteenth century, under the rule of the Mamluk dynasty <strong>in</strong>Syria and Egypt, many of the most prom<strong>in</strong>ent m a d r a s as were be<strong>in</strong>g built <strong>in</strong> acruciform style <strong>in</strong> order to house teachers from all four of the schools simultane o u s l y, one <strong>in</strong> each of the four w<strong>in</strong>gs of the build<strong>in</strong>g. The accommodation ofall four schools with<strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>stitution is a remarkable testament to theopenness to religious op<strong>in</strong>ions and the complex dynamics of Muslim unityand diversity <strong>in</strong> the premodern period.M a d r a s a <strong>in</strong>stitutions stood largely outside direct state control, for they wereprivately founded and funded through w a q f , a special type of religious endowmentthrough which a person could set aside a portion of his wealth to fundmosques, schools, hospitals, or other <strong>in</strong>stitutions of social welfare. Once a Muslimhad formally established a w a q f , he or she could not impose any furtherconditions on the use of the funds, a stipulation that ensured a considerableamount of freedom—academic and otherwise—to the teachers attached tothe m a d r a s as. Wa q f were also important <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g one of the major avenuesfor women’s participation <strong>in</strong> public religious and political life <strong>in</strong> some Muslim

A modern permutation of the public founta<strong>in</strong> waqf, street-side charity <strong>in</strong> Istanbul, Turkey.(R. Michael Feener)