moon catalog p60-104.. - University of Virginia

moon catalog p60-104.. - University of Virginia

moon catalog p60-104.. - University of Virginia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

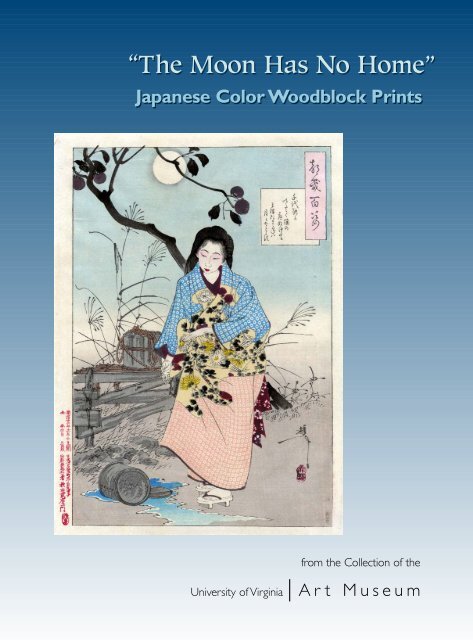

“The Moon Has No Home”Japanese Color Woodblock Printsfrom the Collection <strong>of</strong> the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> | Art Museum

Subverting AuthorityRepetition,Deconstruction andCombinations <strong>of</strong>Words and Images15a15b15Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864No Title (Figures Against Landscape)Signed: Kōchōrō Kunisada gatwo panels <strong>of</strong> a multiple panel set684.110 a, b16Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864Asakusa Kinryūzanc. 1843–45Signed: Kōchōrō Kunisada gaone panel <strong>of</strong> a multiple panel set684.11617Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864Distant View <strong>of</strong> Oji(Oji enken no zu)c. 1810–45Signed: Kōchōrō Kunisada gatriptych16684.123 a, b, c60 “The Moon Has No Home”

17a17b17cThese six prints share the same composition: a single, female figure standsbefore scalloped clouds, above which is a landscape. Kunisada <strong>of</strong>ten usedsuch clouds as a connecting device for a print series. The first two printsform a continuous composition and have the same publisher: Nantembanisaka iriguchi Fujihiko. In addition, a baby boy carried by his motherin one print holds a bamboo pole that continues into the next print. Fromthe pole, dangles a turtle on a string. The third print has a very similarcomposition, but does not match up exactly with them. A different publisheralso published the print: Fujioka-ya Keijirō (Fuji-Kei) Shorindō. Thus, thisprint may come from a different set <strong>of</strong> very similar composition or it andthe previous two may represent parts <strong>of</strong> polyptychs that included morethan three panels. The last three prints form a continuous composition andare all from the same publisher: Ezakiya Tatsukura (E-tatsu) Sankindō.We may identify them as a triptych. The six works together show hownineteenth-century Ukiyo-e repeated compositions, an important point intheir evaluation.S.K.61

1Utagawa Yoshitora1850–70sNo Title (Battle before Mt. Fuji)c. 1849–50Signed: Ichim_sai Yoshitora ga684.258It took three people to make an Ukiyo-e print. An artist (eshi), in this caseYoshitora, designed a composition, which was then copied and pasted to awooden block. A second artisan, the cutter (hori), cut this sketch away tocreate the key or line block from which the color blocks were then produced.A third artisan, the rubber (suri), received the blocks, applied pasteand water, inked them and took the print.The rubber’s art is particularly well represented here. The grain <strong>of</strong> the woodblockis used to suggest the rocky texture <strong>of</strong> Mt. Fuji in the background.The fading sunset was produced by first puddling water on the woodblockand then introducing color, so that capillary action would draw the pigmentto the edge <strong>of</strong> the sky area. As Suzuki Jun has pointed out, such techniquesproduce the edgeless effects one would expect in painting but not in woodcuts.Note also the precision <strong>of</strong> the registration <strong>of</strong> the red and yellow on thegreaves <strong>of</strong> the warrior thrusting a spear and the intensity <strong>of</strong> the red andblack in his cast-<strong>of</strong>f helmet.S.K.15a62 “The Moon Has No Home”

1663

1Utagawa Yoshitora1850–70sNo Title (Battle before Mt. Fuji)c. 1849–50Signed: Ichim_sai Yoshitora ga684.258It took three people to make an Ukiyo-e print. An artist (eshi), in this caseYoshitora, designed a composition, which was then copied and pasted to awooden block. A second artisan, the cutter (hori), cut this sketch away tocreate the key or line block from which the color blocks were then produced.A third artisan, the rubber (suri), received the blocks, applied pasteand water, inked them and took the print.The rubber’s art is particularly well represented here. The grain <strong>of</strong> the woodblockis used to suggest the rocky texture <strong>of</strong> Mt. Fuji in the background.The fading sunset was produced by first puddling water on the woodblockand then introducing color, so that capillary action would draw the pigmentto the edge <strong>of</strong> the sky area. As Suzuki Jun has pointed out, such techniquesproduce the edgeless effects one would expect in painting but not in woodcuts.Note also the precision <strong>of</strong> the registration <strong>of</strong> the red and yellow on thegreaves <strong>of</strong> the warrior thrusting a spear and the intensity <strong>of</strong> the red andblack in his cast-<strong>of</strong>f helmet.S.K.17a64 “The Moon Has No Home”

17b65

Subverting Authority18Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864No Title (Figure Against Landscape)c. 1804–06Signed: Gototei Kunisada ga684.101The composition <strong>of</strong> this and the following print, a woman tying her obi (sash)on her back, are almost the same, although the patterns <strong>of</strong> the kimono andthe backgrounds are different. Kunisada, who was Toyokuni III, created alarge number <strong>of</strong> series <strong>of</strong> beauties, especially after the Kōka Era (1844–1847).Some series consist <strong>of</strong> as many as one hundred prints.The print has no inscriptions. It might be one <strong>of</strong> a polyptych since singleprints usually have titles. Most <strong>of</strong> Kunisada’s polyptychs have the title onlyon the print at the right <strong>of</strong> the group.T.A.66“The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority19Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864The Kannon Temple at Asakusa (Asakusa Kannon)from the series Famous Places in Edo(Edo meisho no uchi)c. 1800–50Signed: Kōchōrō Toyokuni ga684.130This print has the title Asakusa Kannon in a red rectangle on the upper right.The landscape behind the woman is framed. The print can be identified asone in the series Famous Places in Edo because the Hagi Museum <strong>of</strong> Art inYamaguchi Prefecture has a print with the same composition and framedesign but with text on the print stating that the view is One <strong>of</strong> the FamousViews <strong>of</strong> Edo: Takanawa. Kunisada preferred the combination <strong>of</strong> a beautyand a landscape after the success <strong>of</strong> the Tōkaidō series. Asakusa in Edohas been a famous temple town surrounding the Asakusa Kannon templesince the seventeenth century. For further analysis <strong>of</strong> this print, see theessay “The Enigma <strong>of</strong> Allure.”An example <strong>of</strong> Kunisada’s prints that repeat a figure, occasionally withdifferent backgrounds, includes a seated woman combing her hair. Kunisadaused this design in Pride <strong>of</strong> Edo (Edo jiman) <strong>of</strong> 1818, Hundred Beauties inEdo’s Famous Places (Edo meisho hyakunin bijin) <strong>of</strong> 1857–1858, and FamousWomen <strong>of</strong> Then and Now (Kokon meifu den) <strong>of</strong> 1862. The designs are almostall the same. Another example is a woman putting charcoal in a lantern.Kunisada applied this design to Twelve Hours <strong>of</strong> the Clock <strong>of</strong> Present Day(Imayō tokei jūni koki) <strong>of</strong> c. 1820, Frost <strong>of</strong> Stars: Current Manners (Hoshi noshimo tōsei fuzoku) <strong>of</strong> c. 1819, Secret Meeting by Moonlight (Tsuki no kageshinobiau yo) <strong>of</strong> c.1836, One Hundred Poems (Hyakkunin isshu eshō) <strong>of</strong> c. 1844,and One Hundred Beauties in Famous Places in Edo (Edo meisho hyakuninbijo) <strong>of</strong> 1858. In the case <strong>of</strong> this design, Kunisada changed compositionsslightly case by case.T.A.68“The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority20Utagawa Kuniyoshi1797–1861Kabuki Actor Iwai Shijaku as Kojorōc. 1830–42Signed: Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi ga684.203This portrait <strong>of</strong> female impersonator Iwai Shijaku is an excellent example <strong>of</strong>how words and images could be combined in Ukiyo-e. The print bears anextensive inscription reading:Aha! Even if I accept that it is my fate to have a greedybrother, considering the transitoriness <strong>of</strong> life, I can at leastdepend on that Shinbei. Relying on the kindness [heshowed me in] our past friendship, I could, when he disagreedand said no to me, insist and make him promise.Why then did my brother accuse poor me <strong>of</strong> inhumanconduct and adultery in this, and why did he hit me?When I think <strong>of</strong> things up to now, Shinbei has sufferedmuch because <strong>of</strong> you. But, you do not think <strong>of</strong> that at all.No matter how much he was once your retainer, if youthink <strong>of</strong> him as nothing, how can it be that heaven will notpunish you? How would it be if you think back a bit <strong>of</strong>your father living at home...and please change your mind?You are cruel indeed.Dialogue from a Kabuki play, the words <strong>of</strong> the inscription act on the vieweras strongly as the image. Thus, the image does not illustrate the inscription,as much as function in tandem with it.S.K.70“The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority21Utagawa Kunichika1835–1900No Title(Sakamoto Mitsugorō as Mikuniya kojorō andSeki Sanjurō as Oshimono no hahafrom the Kabuki play Tomimoto Buzen Daiū)1864684.97The print shows two figures, a young courtesan and an old woman holdingsome sheaves <strong>of</strong> corn. The intensity <strong>of</strong> the old woman’s gaze and thedelicate way in which the younger woman touches her hair and tucks a handin her sash suggest a clash <strong>of</strong> emotions. The long inscription clarifies themeaning <strong>of</strong> the scene.The old lady looked closely at the form <strong>of</strong> the youngprostitute who seemed most attractive.… (meaning unclear)She took out her bag, seeing which the girl, not expecting it,was most surprised. To this action, the old lady said, slidingup slowly alongside the young prostitute: “Even if yourhusband’s feelings change, you should not be jealous.”[The girl] replied: “Hatred and hostility are like the dew.I do not speak <strong>of</strong> them. However, because I am a woman,I do feel that they are unbearable. Like a disease whosecause is not known, day by day I grow thinner. Sad. I amnot even twenty in body but am now a widow and will beso all my life. I am a girl made widow. For duty’s sake,I accept this unreasonable request.” With that, the youngprostitute felt in her heart a feeling like waves splashing ona rock.Knowing the text clarifies the meaning <strong>of</strong> the scene. And yet, just from theimage itself, much <strong>of</strong> its emotional content can be grasped. Translating thedifficult Japanese inscription contributes to our understanding <strong>of</strong> the print,but such translation is not absolutely necessary for the appreciation <strong>of</strong> thisprint as a work <strong>of</strong> art.S.K.72“The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority22Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864No Title(Ichikawa Danzaburō as a Woodcutter,Ichikawa Danjurō as a Monkey andIchikawa Shinnosuke as a Child Monkey)c. 1805–42Signed: Gototei Kunisada gatwo panels <strong>of</strong> a multiple panel set684.126 a, bThese two prints show actors <strong>of</strong> the Ichikawa family. Inscriptions identify theman bearing sticks on his back and the large man-monkey as IchikawaDanzaburō and Danjurō respectively. The third inscription reads “IchikawaShinnosuke as the child monkey.” The monkey presents a strong imagein Japanese art and literature, ranging from positive religious significance tobeing thought <strong>of</strong> as clever but duplicitous.Both adult Ichikawa wear jackets with a crest <strong>of</strong> squares in squares, a crestadopted by the Ichikawa family <strong>of</strong> actors after the Shogun gave them a gift <strong>of</strong>square wooden drinking boxes nested in one another.Kunisada drew every hair on the bodies <strong>of</strong> the two monkeys, portrayed theclothing with meticulous care, and took pains to show every detail <strong>of</strong> the treebranch, staff, and belt. And yet, this print is finally not about reportage onreality but about playing with what is real, as noted in my <strong>catalog</strong>ue essay.S.K.74“The Moon Has No Home”

22b75

Subverting Authority23Ikeda Eisen1790–1848Yōkyō from the seriesTwenty-four Ukiyo-e Favorites(Ukiyo-e nijūshikō:Yōkyō)Signed: Eisen ga684.42The inscription states:Seeing the tiger-cat stalk the nightingale under the eaves,hearing daughter “sho-sho” him away, [I] feel the filialpiety <strong>of</strong> Yōkyō, as she flies towards the ro<strong>of</strong>. Stretching thepoint to see the cat as tiger, here is a play between the 24Favorites <strong>of</strong> Ukiyo-e and the 24 Paragons <strong>of</strong> Filial Piety.Mention <strong>of</strong> the figure <strong>of</strong> Yōkyō shows that Eisen’s intent was a playbetween the 24 favorite interests (or pastimes) <strong>of</strong> Ukiyo-e and the ChineseConfucian “24 Filial Exemplars.” Compiled by Fuo Jūjing <strong>of</strong> the YuanDynasty, the latter consisted <strong>of</strong> 24 stories <strong>of</strong> filial piety, a crucial elementin human relationships in Confucian society.The story <strong>of</strong> Yōkyō (Chinese: Yang Xiang) tells how this fourteen-year-oldboy rescued his father when the latter, out harvesting, was attacked bya particularly ferocious tiger. The tiger, which had a white forehead, issupposed to have eaten one hundred people before he attacked Yōkyō’sfather. Yōkyō beat the tiger <strong>of</strong>f bare-handed.In Eisen’s portrayal <strong>of</strong> the scene, a pet cat replaces the tiger. The cat is stillstalking its prey—in this case a bird. A baby girl carried by her mother,like the brave young Yōkyō, scares the cat away by brandishing a stick.The picture wittily modifies the perilous situation in the Chinese story intoa parody <strong>of</strong> a feminized and residential scene.J.L.76“The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority24Utagawa Hiroshige1797–1858Kogane Plain in Shim<strong>of</strong>usa Province(Shim<strong>of</strong>usa: Koganehara)from the series Thirty-six Views <strong>of</strong> Mt. Fuji(Fuji sanjūrokkei)1858Signed: Hiroshige gaMuseum Purchase with funds from theE. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation2002.23This work is print number 33 <strong>of</strong> Hiroshige’s version <strong>of</strong> Thirty-six Views <strong>of</strong>Mt. Fuji, issued around 1858–1859 by the publishing house Tsutaya inresponse to the more famous set by Hokusai that the Eijudō issued around1829–1833. The volcano Mt. Fuji, some 12,385 feet high and shaped like aninverted fan, was by then dormant, having last erupted around 1708.The mountain is one <strong>of</strong> the great beauty spots <strong>of</strong> Japan and is pictured byHiroshige from an unusual viewpoint. For further analysis <strong>of</strong> this print,see the essay “The Enigma <strong>of</strong> Allure.”S.K.78 “The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority25Utagawa Toyokuni1769–1825No Title from the series Five Beauties (Gonin bijo)c. 1780–1825Signed:Toyokuni684.235This print features a beauty seated at a kotatsu (a low table with a quiltcover and a brazier below for keeping the lower half <strong>of</strong> the body warm inwinter). The woman is lifting the quilt to place hot coals from the brazierat her side into the brazier at her feet.Prior to the Tenmei era (1781) depictions <strong>of</strong> women seated at a kotatsuwere classified as abuna-e, “revealing pictures” that showed the female formeither naked or partially clothed and clearly erotic, but at the time thisparticular print was made, the distinction between abuna-e and bijinga(portraits <strong>of</strong> beauties) was fading.Nonetheless, there is a distinctly erotic quality to this print, due to the action<strong>of</strong> “revealing” what has been hidden—the woman’s feet and lower body.The focal point <strong>of</strong> the print is clearly on the woman’s bare foot, madevisible by her everyday action <strong>of</strong> lifting the quilt. In Japan bare feet are eroticin and <strong>of</strong> themselves. (Geisha were not allowed to wear tabi, or socks, asmost people did.) Modern Japanese author Tanizaki Jun’ichiro (1886–1965)dramatically demonstrates this in his 1919 novella Fumiko no ashi(Fumiko’s Feet, untranslated), in which the chief love interest, an Edo-stylebeauty and the mistress <strong>of</strong> a pawnbroker, is first seen seated at a brazier,as in this excerpt:When I came into the room, a woman was leaning on oneelbow at the kotatsu. Her knees were slightly askew, whileher neck and body were twisted in my direction. WhenI say that her “neck” and “body” were twisted, it seemedthat each were entirely separate things, and I wasimpressed by the beauty <strong>of</strong> both. In other words, thatsupple, streamlined neck moved together with that s<strong>of</strong>t,slim, almost too-thin body, as though sending <strong>of</strong>f ripples,one wave after another. Even after she faced me straighton, it seemed that those ripples remained, slowly driftingtoward me from somewhere in her body, perhaps fromthe place where her shoulders emerged from her kimonothat was slightly pulled open at the nape <strong>of</strong> her neck.In many ways, Tanizaki’s description could be <strong>of</strong> this Toyokuni print. Thewoman in the print is in an awkward, even impossible pose. The wave-likedesign on the woman’s kimono reminds one <strong>of</strong> ripples on the water, andthe shoulders <strong>of</strong> the kimono droop down, revealing the neck. In boththe story and the print, however, it is ultimately the woman’s foot to whichthe eye is inextricably drawn, as it embodies the woman’s sensuality.G.J.80 “The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority26Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864No. 22 from the seriesTale <strong>of</strong> the Life Story <strong>of</strong> Loyal Ōboshi(Seichū Ōbohsi ichidai banashi)c. 1847–48Signed: Kōchōrō Kunisada ga684.138The title bar identifies the print as the twenty-second in the series Tale <strong>of</strong>the Life Story <strong>of</strong> Loyal Ōboshi (Seichū Ōboshi ichidai banashi). The shavedforehead and double-comma crest <strong>of</strong> the figure identify him as ŌboshiYuranosuke, leader <strong>of</strong> the forty-seven masterless samurai (rōnin) <strong>of</strong>The Treasury <strong>of</strong> the Loyal Retainers (Kanadehon Chūshingura), who avengetheir dead lord. This Kabuki drama, popular since 1748, was based onan actual incident. The inscription reads:Ōishi Rikiya (Chikara), age 15.After the death <strong>of</strong> the Lord <strong>of</strong> Ako, his [retainers] scattered.They idled their time away in Yamashina Kyoto. [Rikiya’s]father Yuranosuke lost himself in play, doing nothing butbad things. This, Rikiya deeply regretted. One day, heremonstrated with his father. Using every word that hecould, he admonished his father. Yuranosuke got angry.With a fan, he beat Rikiya. Downtrodden, Rikiya went tohis room. Writing a letter, he would have killed himself.Yuranosuke ran there and stopped him. He then said:“Because you are so young, I did not tell you, but there isa secret plan. You are so brave, so I should tell you whatis in my heart. We camouflage [our intent] by seeming tolose ourselves in pleasure, but the loyal ones are pledged[to take revenge].” Thus he explained himself in detail andRikiya cried with happiness.Signed: Ippitsu-An (Katsushika Hokusai)Ukiyo-e <strong>of</strong>ten did not just illustrate Kabuki plays but served as a kind <strong>of</strong>parallel art, showing what the theater could not. Consider the appearance<strong>of</strong> Yuranosuke. His powerful resolution comes through clearly and hisfirmness contrasts strongly with the feeble shadow seen in the window.Is the scene a metaphorical representation <strong>of</strong> Yuranosuke’s intent asexpressed in act nine <strong>of</strong> The Treasury <strong>of</strong> the Loyal Retainers? There, thedrunken Yuranosuke made a snowball and explained its significance toRikiya, saying “As snow will not melt in shade, so the rōnin, living undera shadow, will survive.” Is the faint shadow in back the false image thatYuranosuke’s enemies see and the clear figure in front what he truly is?Assuming so, the print literally visualizes a metaphor, doing what the actoron stage cannot.J.L.82 “The Moon Has No Home”

27Utagawa Kunisada1786–1864Investigator <strong>of</strong> Boats Kingorō,The Geisha Kozan,The Dealer in Used Goods Jinzō(Funa aratame Kingorō, Geisha no Kozan, Furuteya Jinzō)1856Signed:Toyokuni gatriptych684.172 a, b, cKabuki stage sets could create the image <strong>of</strong> boats at sea. A solid structureresembling a boat was constructed on stage or cut-outs (kiridashi) were used.Alternatively, the shuttered rooms <strong>of</strong> Edo pleasure boats could be reproducedon stage rather than the whole ship. When scenes at sea were portrayed,the cloth covering the stage floor, called a jigasuri or dorogire, would bepainted blue rather than brown to suggest water. In this case, the coveringwas sometimes called a mizu nuno. The stage assistants would also dress inblue rather than black, and their water-colored clothing was called nami-ko.A label in the print identifies one <strong>of</strong> the struggling figures as the owner <strong>of</strong>a furuteya or furugiya, a shop specializing in the sale <strong>of</strong> used clothing, books,and other things. A highly lucrative business, furuteya grew so prosperousthat the government eventually licensed the trade in an effort to control it.S.K.84 “The Moon Has No Home”

27a85

Subverting Authority28Kitagawa Utamaroc. 1753–1806The Courtesan Chozan from Chōjiya(Chōjiyanai Chozan)c. 1800Signed: Utamaro hitsuMuseum Purchase with funds from theE. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation2003.4.1Like Hiroshige and Hokusai, Utamaro is a quintessential and even emblematicUkiyo-e artist who had a major influence on European Impressionists<strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century. Although <strong>of</strong>ten admired for his elegant serenityand Classical beauty and restraint (in supposed contrast to later and wilderUkiyo-e artists), Utamaro has at times been accused <strong>of</strong> having an obsessionwith the high-class courtesans <strong>of</strong> the Yoshiwara district. His lyrical anddeeply affecting observations <strong>of</strong> the everyday detail <strong>of</strong> the lives <strong>of</strong> thesewomen may have opened the eyes <strong>of</strong> Western artists but also exposed himto accusations <strong>of</strong> “decadence” and voyeurism. The elongated loveliness <strong>of</strong>his women, whose kimonos have wave-like rhythms, has been calledmannered by some and by others, indicative <strong>of</strong> the spiritual or idealisticnature <strong>of</strong> his “obsession.” Utamaro was, however, capable <strong>of</strong> makingequally lovely, observant, and moving pictures <strong>of</strong> mothers and children.Like other Ukiyo-e artists, he was persecuted by the government authorities<strong>of</strong> the oppressive and feudalistic Tokugawa regime in the days beforeJapan was opened to the West.This print is actually an image <strong>of</strong> a picture within a picture and, like otherprints in The Moon Has No Home, possesses a magical quality, which notonly erases the distance between art and reality or fact and imagination,but also subtly allows the image to rise into the viewer’s mind. At the sametime, like many <strong>of</strong> those other prints, it acknowledges its own artifice whilesustaining the poetry <strong>of</strong> its effects. For further analysis <strong>of</strong> this importantprint, see the essay “The Enigma <strong>of</strong> Allure.”S.M.86 “The Moon Has No Home”

Subverting Authority29Utagawa Kuniyoshi1797–1861Onoe Kikugorō (as Nagata no Tarō Nagamune)c. 1841Signed: Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi ga684.194Another image <strong>of</strong> Nagata no Tarō Nagamune by Kuniyoshi can be found inthe Library <strong>of</strong> Congress, where the figure wears the same unusual tasseledrobe. This clothing and the rats appearing in the print identify it as anillustration <strong>of</strong> the Kabuki play Raigō ajari kaisoden, an adaptation <strong>of</strong>Kyokutei Bakin’s (1767–1848) novel <strong>of</strong> 1808.Bakin was the fifth son <strong>of</strong> a low-ranking samurai who gave up warriorstatus to become a chōnin. Like his teacher, Santo Kyōden (1761–1816),a writer and Ukiyo-e artist who was jailed once for his burlesque <strong>of</strong>Confucianism, Bakin became an important figure in popular fiction(yomihon), dominating the field between 1803–13. In this time, he producedmore than thirty titles. He later turned to historical romance, writingthe famous Biographies <strong>of</strong> Eight Dogs (Nansō satomi hakkenden) in periodicinstallments between 1814–42. Bakin went blind before the project wascompleted, and he finished it only with the aid <strong>of</strong> his daughter.Robert Hegel has remarked on how the rise <strong>of</strong> popular fiction in Chinaaided the development <strong>of</strong> the print industry there by providing literaryworks that lent themselves easily to illustration. Unlike earlier writings,whose images, if refined, were difficult to draw, popular prose producedsimple, graphic descriptions <strong>of</strong> things that could be easily transformed intoprinted images. We may see a similar process at work here.S.K.88 “The Moon Has No Home”

Yoshitoshi Group30Tsukioka Yoshitoshi1839–1892The Moon at High Tide (Ideshio no tsuki) from the seriesOne Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi)1886Signed: YoshitoshiGift <strong>of</strong> Kendon and Patricia Stubbs1998.24This print depicts an old couple sweeping pine needles in the <strong>moon</strong>light.They are figures from the Noh play Takasago, written by Zeami Motokiyo inthe early fifteenth century. Takasago is a “god play” in which a Shinto priesttraveling from the Aso shrine in Kyushu to Kyoto passes by a pine-forestedbeach at Takasago in Harima Province (modern day Hyogo Prefecture).As the <strong>moon</strong> rises, the figures <strong>of</strong> an old man, Jō, and an old woman, Uba,appear beneath the pines. They are the spirits <strong>of</strong> the pine at Harima and atSumiyoshi (near Osaka). Although separated by space, their hearts are one.Together in their humble waraji (straw sandals), the pair sweep the fallenneedles <strong>of</strong> their spiritual home until the dawn when they vanish aboard aboat singing “together with the <strong>moon</strong> and the rising tide” (Tsuki morotomoniideshio no nami), which gives the print its title.As spirits <strong>of</strong> the pine tree, the old couple represent vigor and long life (evergreensdo not change and die with the seasons and so represent immortality).Pine trees are one <strong>of</strong> the three auspicious symbols <strong>of</strong> Japan, along withbamboo and plum blossoms. The trees themselves suggest an umbrella-likeform over the aged couple, a holy space over which the spirit <strong>of</strong> the tree canexercise strong power.The figures <strong>of</strong> the two spirits borrow imagery from Noh masks and costumes.The male figure’s face resembles the Noh mask for an old man, or Jō,a human manifestation <strong>of</strong> an aged Japanese kami, or god. His expressionderives from Shinto sculptures <strong>of</strong> old men whose long suffering shows in thedeep wrinkles <strong>of</strong> the brow. Traditionally, the Jō wears the large culotte-likepants called hakama over a kimono with an outer robe called a haori andcarries a rake. His wife’s face is that <strong>of</strong> another Noh mask, the old woman,or Uba, which is a manifestation <strong>of</strong> a female god come to earth. She alwaysappears with a hachimaki headband and a broom made <strong>of</strong> branches. Thegreen lines in her robe evoke the needles <strong>of</strong> the pine tree that she inhabits.The evergreen pine, the masks, and the old couple are major symbols atmodern Japanese weddings. Most hotels and wedding halls have largeimages <strong>of</strong> the pair, complete with their pine tree, painted on an entry wall,or used as a stage backdrop during receptions. Older Japanese may beasked to sing the utai, or song from Takasago, to a newly married coupleas a reminder <strong>of</strong> the real meaning <strong>of</strong> marriage.T.K.90 “The Moon Has No Home”

Yoshitoshi Group31Tsukioka Yoshitoshi1839–1892The Story <strong>of</strong> Jirōzaemon <strong>of</strong> Sano(Sano Jirōzaemon no hanashi)from the seriesA New Selection <strong>of</strong> Eastern Brocade Pictures(Shinsen azuma nishiki-e)1886Signed:YoshitoshidiptychMuseum Purchase with funds from theE. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation1997.27.3 a, bIn this image, Yoshitoshi depicts a scene from a Kabuki play. Kabuki andUkiyo-e were <strong>of</strong>ten inspired by what today might be called material fortabloids. The artist makes a very strong contrast between the stately andsplendid courtesan and the ugly country bumpkin (Jirōzaemon) who ismurdering her out <strong>of</strong> resentment for being rejected. Although the slaughteredgrand courtesan Yatsuhashi is drawn in a somewhat traditional idealizedUkiyo-e style, the bumpkin is drawn with Western realism in a manner thatemphasizes his maddened cruelty. The bloody, lurid light <strong>of</strong> the bumpkin’slantern is used with a sense <strong>of</strong> drama and aesthetic self-awareness worthy<strong>of</strong> Alfred Hitchcock. We see in the light <strong>of</strong> the artist, whose handiworkis observable in the bloody handprint on the bumpkin’s leg (the handprintwas probably made by poor Yatsuhashi, but reminds us that handprintscould serve as a kind <strong>of</strong> signature in Japan). The plover design on thecourtesan’s kimono seems to metamorphose into the tissue papers thathave scattered into flight like birds. Is her soul flying away from this tragicstage? High-class courtesans were sometimes viewed as heroic or almostsaintly, at least in Kabuki or Ukiyo-e, because they were thought to haveentered their pr<strong>of</strong>ession for reasons <strong>of</strong> self-sacrifice. Uninked passagesin this richly “brocaded” print may remind us <strong>of</strong> the possibility <strong>of</strong> purity andpeace. Once condemned as vulgar, the boldness <strong>of</strong> color, design andpsychology exemplified by Yoshitoshi, his teacher, Kuniyoshi, and Kunisadanow seem prophetic <strong>of</strong> Modernist sensibility. For further analysis <strong>of</strong> thisprint, see the essay “The Enigma <strong>of</strong> Allure.”S.M.92 “The Moon Has No Home”

Yoshitoshi Group32Tsukioka Yoshitoshi1839–1892Reflected Moonlight from the seriesOne Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> the Moon(Tsuki hyakushi)1886Signed:YoshitoshiMuseum Purchase with funds from Kendon and Patricia Stubbs1997.27.1Lady Ariko, the subject depicted, wrote the poem inscribed on the print(translated in John Stevenson’s Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> theMoon). This print is <strong>of</strong>ten referred to as Reflected Moonlight, but that is notthe title. The inscribed poem on the upper right is as follows:How hopeless it isit would be better for me to sink beneath the wavesperhaps there I could see my man from Moon CapitalThe print is one <strong>of</strong> a highly regarded series that ranges widely in Japanesehistory and legend and that attains a subtle serenity and humanity incontrast to the cruelty and explosive violence sometimes apparent inYoshitoshi’s work. The <strong>moon</strong>, symbol <strong>of</strong> both purity and change, plays arole in each image. In fact, the Moon Series may represent a high point inthe art <strong>of</strong> the Meiji period and a successful fusion <strong>of</strong> traditional Japanesestyle and belief with considerable innovation and Western stylistic influence.Ariko no Naishi was a lady-in-waiting at the highly refined Heian Court <strong>of</strong>classic Japan, whose suicide over unrequited love inspired a Noh play.In this image, Lady Ariko holds her lute while weeping and covering herface. She seems about to drown herself in the very brilliance <strong>of</strong> <strong>moon</strong>lightreflected on the waters <strong>of</strong> Lake Biwa. In a sense, she is going to enter thenaked sheet <strong>of</strong> paper, since the <strong>moon</strong>light effect is created by not inkinga portion <strong>of</strong> the woodblock. Her kimono, burnished, shines. She willparadoxically sink only to rise to the sky through the <strong>moon</strong>light. The motifon her kimono, called the half-wheel pattern, was used to symbolize awoman who has been abandoned by her lover, although it may, for somepeople, also recall the Buddhist Wheel <strong>of</strong> Life. “Moon Capital” refers toKyoto, the Heian capital, according to Stevenson. For further analysis <strong>of</strong>this print, see the essay “The Enigma <strong>of</strong> Allure.”S.M.94 “The Moon Has No Home”

Yoshitoshi Group33Tsukioka Yoshitoshi1839–1892Gravemarker Moon(Sotōba no tsuki)from the seriesOne Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> the Moon(Tsuki hyakushi)1886Signed:YoshitoshiGift <strong>of</strong> Kendon and Patricia Stubbs1998.1In the Noh play that is the inspiration for Yoshitoshi’s print, the famousninth-century poet Ono no Komachi is sympathetically portrayed asachieving wisdom and salvation, despite the former beauty being “punished”in old age by poverty and decreptitude. She badly ill-treated a suitor,whose ghost occasionally takes possession <strong>of</strong> her. The play, entitled SotōbaKomachi (Gravemarker Komachi), is by Kwanami (or Kan´ami) and has beentranslated by Arthur Waley in his The Nō Plays <strong>of</strong> Japan (London, 1954).In Yoshitoshi’s image, Komachi sits on a fallen gravemarker. In the Nohplay, two priests will rebuke her for dishonoring Buddha by sitting on asacred Stūpa. Bested by her in what amounts to a theological dispute overletter versus spirit, they end by acclaiming her as a saint in spite <strong>of</strong> heroutcast status. They seem convinced by her argument that salvation arisesin the heart no matter what one sits upon. In Waley’s translation, Komachisays <strong>of</strong> her hope in Buddha: “For the welfare <strong>of</strong> the humble, the ill-instructed,/Whom he has vowed to save,/Sin itself may be a ladder <strong>of</strong> salvation.”Yoshitoshi depicts Komachi as radiating benevolence and serenity in herloneliness. He is even more sympathetic to her than is the play. Her tatteredstraw hat, emblem <strong>of</strong> poverty and abandonment, almost looks like a pair <strong>of</strong>wings on her back. Her costume reminds us <strong>of</strong> her gorgeous and l<strong>of</strong>ty pastbut its uninked embossed area, together with her white hair and palefeatures, make her seem angelic or ghostly, especially in contrast with thenight scene around her. The pampas grass in back <strong>of</strong> Komachi emphasizesthe wing-like nature <strong>of</strong> her straw hat while the meandering stream remindsus <strong>of</strong> the Floating World and <strong>of</strong> a poem by Komachi herself, translated inJohn Stevenson: “I’m so lonely that I’d break <strong>of</strong>f this sad body from itsroots/and drift away like a floating reed—if the current were to beckon.”S.M.96 “The Moon Has No Home”

Yoshitoshi Group34Tsukioka Yoshitoshi1839–1892Lunacy—Unrolling Letters(Tsuki no monogurui-fumihiroge)from the seriesOne Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> the Moon(Tsuki hyakushi)1889Signed:YoshitoshiMuseum Purchase with funds from theE. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation1997.27.2The woman standing on the bridge, Ochiyo, is the servant <strong>of</strong> a lady in thecourt <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the most renowned warriors in Japanese history, ToyotomiHideyoshi, who in the sixteenth century played a major role in the unification<strong>of</strong> Japan. Ochiyo, however, is going mad over the death <strong>of</strong> her lover. In hisMoon Series, Yoshitoshi, like Shakespeare, shows sympathy for women andfor breaking hearts, as well as for traditional heroism. She is unrolling thelove letter scrolls <strong>of</strong> her lover, which she has read to tatters. (There wasa special time <strong>of</strong> the year for letters to be unrolled and aired out.) The letterseems to unroll <strong>of</strong> its own accord and rise in twists and curls far up into thesky, where it reaches the sliver <strong>of</strong> a <strong>moon</strong> half-hidden behind dark clouds.The twisting folds <strong>of</strong> Ochiyo’s kimono and its design <strong>of</strong> a winding streammake the servant woman herself look like a rolled up scroll ready to unwind.Is she herself about to unwind and rise up to Heaven? As in other Ukiyo-eprints, the uninked passages—in this case, areas <strong>of</strong> the letter—add a note<strong>of</strong> purity or eerie spirituality to the image, at the same time possessinga Postmodern touch <strong>of</strong> exposing the reality <strong>of</strong> naked paper. John Stevenson,in his book on the Moon Series, points out that the lunacy <strong>of</strong> the titlespecifically refers to the fetishistic obsessiveness <strong>of</strong> Ochiyo’s thinking.The bridge she stands on, famous in heroic legend, is shadowy and remindsone <strong>of</strong> a Buddhist concept also found in The Tale <strong>of</strong> Genji—that this lifeis a “bridge <strong>of</strong> dreams” only linking one dream or illusion to another.Bridges in Ukiyo-e had a strong influence on similar bridges that appear inthe works <strong>of</strong> European Impressionists, such as American expatriate artistJames A. M. Whistler.S.M.98 “The Moon Has No Home”

Yoshitoshi Group35Tsukioka Yoshitoshi1839–1892Lady Chiyo from the seriesOne Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> the Moon(Tsuki hyakushi)1889Signed:YoshitoshiMuseum Purchase with funds fromKendon and Patricia Stubbs2002.22In his Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> the Moon, John Stevensongives the translation <strong>of</strong> the poem inscribed on this print. It is <strong>of</strong>ten referredto as Lady Chiyo, but that is not the title. The poem on the upper right isas follows:The bottom <strong>of</strong> the bucketwhich Lady Chiyo filled has fallen outthe <strong>moon</strong> has no home in the waterEighteenth-century painter, calligrapher, haiku poet, and nun, Chiyo wrotea famous poem describing how morning glories growing in the night hadtaken over her well-bucket, which caused her, in her delicacy, to borrowwater from her neighbor rather than injure the flowers. The poem inscribedon the print may be a Zen poem composed by Chiyo and slightly revisedby Yoshitoshi. It is a somewhat startling variation on the more famous poem,as is the image itself. In fact, Chiyo wrote many poems about water andmorning glories, some <strong>of</strong> which are lovely in their purity and some <strong>of</strong> whichare skeptical, witty, and even self-deprecating. Like Yoshitoshi, Chiyoassociated with courtesans. They shared with her a love <strong>of</strong> poetry and aneed to be apart from the ordinary role <strong>of</strong> women in Japanese society. Chiyoacknowledges the seemingly contradictory meanings <strong>of</strong> water and <strong>of</strong> theFloating World—purity, instability, freedom, sensual immediacy, capacity forcleansing, heartbreaking ephemerality, clear reflector <strong>of</strong> truth. This key print,whose inscribed poem provides the title for The Moon Has No Home, is morefully discussed in the essay “The Enigma <strong>of</strong> Allure” in this <strong>catalog</strong>ue.S.M.100 “The Moon Has No Home”

101

Selected BibliographyBaudelaire, Charles. The Painter <strong>of</strong> Modern Life and Other Essays. Translated and edited by JonathanMayne. New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1964.Carter, Angela. Fireworks: Nine Pr<strong>of</strong>ane Pieces. New York: Penguin Books, 1974.Clark, Timothy. Ukiyo-e Paintings in the British Museum. Washington, DC: Smithsonian InstitutionPress, 1992.Donegan, Patricia and Yoshie Ishibashi. Chiyo-ni: Woman Haiku Master. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Co.,1998.Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988.Floyd, Phyllis. “Documenting Evidence for the Availability <strong>of</strong> Japanese Imagery in Europe in 19th c.Public Collections.” In Art Bulletin 68 (March 1986): 105–141.Freud, Sigmund. Collected Papers. Authorized translation under the supervision <strong>of</strong> Joan Riviere.Vol. 4, Papers on Metapsychology; Papers on Applied Psycho-Analysis. New York: Basic Books, 1959.Gunji, Masakatsu. Kabuki. Translated by John Bester with photographs by Chiaki Yoshida and introductionby Donald Keene. Tokyo, New York, and San Francisco: Kodansha International, Ltd., 1978.Hanley, Susan B. Everyday Things in Pre-Modern Japan: The Hidden Legacy <strong>of</strong> Material Culture.Berkeley and Los Angeles: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> California Press, 1997.Hass, Robert, trans. and ed. The Essential Haiku: Versions <strong>of</strong> Bashō, Buson, and Issa. Hopewell,New Jersey: The Ecco Press, 1994.Hillier, Jack. The Japanese Print: A New Approach. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1975.Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study <strong>of</strong> the Play Element in Culture. Boston: BeaconPress, 1955.Hur, Nam-lin. Prayer and Play in Late Tokugawa Japan: Asakusa Sensō-ji and Edo Society. Cambridge,Massachusetts: Harvard <strong>University</strong> Asia Center, 2000.Ishiguro, Kazuo. An Artist <strong>of</strong> the Floating World. London: Faber, 1986.Izzard, Sebastian. Kunisada’s World. New York: Japan Society, 1993.Johnson, Deborah. “Confluence and Influence: Photography and the Japanese Print in the 1850’s.”In Readings in Nineteenth Century Art. Edited by Janis Tomlinson. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey:Prentice Hall, 1974, pp. 83–107.Keene, Donald. “Characteristic Responses to Confucianism in Tokugawa Literature.” In Confucianismand Tokugawa Culture. Edited by Peter Nosco. Honolulu: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Hawaii Press, 1997,pp. 120–137.Keyes, Roger. Courage and Silence: A Study <strong>of</strong> the Life and Color Woodblock Prints <strong>of</strong> TsukiokaYoshitoshi, 1839–1892. Ann Arbor, Michigan: <strong>University</strong> Micr<strong>of</strong>ilms International, 1983.______. The Edward Burr Van Vleck Collection <strong>of</strong> Japanese Prints. Madison: Elvehjem Museum <strong>of</strong> Art,<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin, 1990.Kita, Sandy. “The Elvehjem Museum Yanone Goro: A Late Example <strong>of</strong> the Torii Tradition.”In Oriental Art 34 (Summer 1988): 106–116.______. A Hidden Treasure: Japanese Woodblock Prints from the Carnegie Museum <strong>of</strong> Art. Pittsburgh:Carnegie Institute, 1996._______. “Kaikoku michi no ki: A Seventeenth Century Travelogue by Iwasa Matabei.”In Monumenta Serica 45 (1997): 309–352.______. The Last Tosa: Iwasa Katsumochi Matabei, A Bridge to Ukiyo-e. Honolulu: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>Hawaii Press, 1999.102 “The Moon Has No Home”

______, et. al. The Floating World <strong>of</strong> Ukiyo-e: Shadows, Dreams, and Substance. New York: Harry N.Abrams, Inc. in association with The Library <strong>of</strong> Congress, 2000.Kobayashi Tadashi. “Mitate in the Art <strong>of</strong> Ukiyo-e Artist Suzuki Harunobu.” In The Floating WorldRevisited. Edited by Donald Jenkins. Portland, Oregon: Portland Art Museum, 1993, pp. 85–91.Kominz, Laurence. “Ichikawa DanjūrōV and Kabuki’s Golden Age.” In The Floating World Revisited.Edited by Donald Jenkins. Portland, Oregon: Portland Art Museum, 1993, pp. 63–83.Lane, Richard. Images from the Floating World: The Japanese Print. New York: Dorset Press, 1978.Luke, Timothy W. Museum Politics. Minneapolis: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Minnesota Press, 2002.McClain, James L., John M. Merriman, and Ugawa Kaoru. Edo and Paris. Ithaca, New York andLondon: Cornell <strong>University</strong> Press, 1994.Matsunosuke, Nishiyama. Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600–1868.Translated and edited by Gerald Groemer. Honolulu: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Hawaii Press, 1997.Meech, Julia. The Matsukata Collection <strong>of</strong> Ukiyo-e Prints. New Brunswick: The Jane Vorhees ZimmerliArt Museum, Rutgers, State <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> New Jersey, 1988.Michener, James A. The Floating World. New York: Random House, 1954._______. Japanese Prints: From the Early Masters to the Moderns. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. TuttleCo., 1959.Mishima,Yukio. Death in Midsummer and Other Stories. Translated by Donald Keene, et al. NewYork: New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1966.Mitford, A. B. (Lord Redesdale). Tales <strong>of</strong> Old Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966.Nakamachi Keiko. “Ukiyo-e Memories <strong>of</strong> Ise monogatari.” In Impressions 22 (2000). Translated byHenry Smith and Miriam Wattles, 55–85.Noguchi, Yone. Selected English Writings <strong>of</strong> Yone Noguchi: An East-West Literary Assimilation. Editedby Yoshinobu Hakutani. Vol. 2, Prose. Rutherford, New Jersey: Farleigh Dickinson <strong>University</strong> Press,1992.Neuer, Roni and Herbert Libertson. Ukiyo-e: 250 Years <strong>of</strong> Japanese Art. New York: Gallery Books, 1979.Ooms, Herman. “Forms and Norms in Edo Arts and Society.” In Edo: Arts in Japan 1615–1868.Edited by Robert T. Singer. Washington, DC: National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Art, 1998, pp. 23–47.Oshima, Mark. “The Keisei as a Meeting Point <strong>of</strong> Different Worlds: Courtesan and KabukiOnnagata.” In Women <strong>of</strong> the Pleasure Quarter: Japanese Paintings and Prints <strong>of</strong> the Floating World.Edited and with contributions by Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, et al. New York: Hudson Hills Press,1995, 87–105.Perrucchi-Petri, Ursula. “Japonisme in Bonnard’s Early and Late Work.” In Pierre Bonnard: Early andLate. Edited by Elizabeth Hutton Turner. Washington, DC: Philip Wilson Publishers in collaborationwith the Phillips Collection, 2002, pp. 190–203.Reps, Paul, and Nyogen Senzaki, eds. Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection <strong>of</strong> Zen and Pre-Zen Writings.Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1998.Robinson, B. W. Kuniyoshi. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1961.Screech, Timon. The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan: The Lens withinthe Heart. Cambridge, England: Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press, 1996.______. The Shogun’s Painted Culture: Fear and Creativity in the Japanese States, 1760–1829. London:Reaktion Books, Ltd., 2000.Segalen, Victor. Oeuvres Complètes. Edited by Henry Bouillier. Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 1995.103

ColophonDesignAnne ChesnutTypeHiroshige, Gill Sans,MinchoPaperMcCoy 80# coverPrintingColormarkSeigle, Cecilia Segawa. Yoshiwara: The Glittering World <strong>of</strong> the Japanese Courtesan. Honolulu:<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Hawaii Press, 1993.Shen Fu. Six Records <strong>of</strong> a Floating Life. Translated by Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui. London:Penguin Books, 1983.Spate, <strong>Virginia</strong> and David Bromfield. “A New and Strange Beauty: Monet and Japanese Art.”In Monet and Japan. Washington, DC: National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Art, 2001, pp. 1–63.Stern, Harold P. Master Prints <strong>of</strong> Japan: Ukiyo-e hanga. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1969.Stevenson, John. Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects <strong>of</strong> the Moon. Redmond, Washington:San Francisco Graphic Society, 1992.Suzuki, Juzō and Isaburō Oka. The Decadents: Masterworks <strong>of</strong> Ukiyo-e. Translated by John Bester.New York: Kodansha International, 1969.Tanizaki, Jun’ichirō. In Praise <strong>of</strong> Shadows. Translated by Thomas J. Harper and Edward G.Seidensticker. New Haven, Connecticut: Leete’s Island Books, 1977.Turner, Elizabeth Hutton. “The Imaginary Cinema <strong>of</strong> Pierre Bonnard.” In Pierre Bonnard, Earlyand Late. Edited and with contributions by Elizabeth Hutton Turner, et al. Washington, DC: PhillipWilson Publishers in collaboration with the Phillips Collection, 2002, pp. 52–73.van den Ing, Eric and Robert Schaap. Beauty and Violence: Japanese Prints by Yoshitoshi 1839–1892.Bergyk, The Netherlands: Society for Japanese Arts, 1992.Wilde, Oscar. The Picture <strong>of</strong> Dorian Gray. Edited by Peter Ackroyd. Harmondsworth, Middlesex,England: Penguin Books, 1985.Wood, Gillen D’Arcy. The Shock <strong>of</strong> the Real: Romanticism and Visual Culture, 1760–1860. New York:Palgrave, 2001.Yiengpruksawan, Mimi Hall. “Japanese Art History, 2001: The State and Stakes <strong>of</strong> Research.”In Art Bulletin 83 (March 2001): 105–122.Catalogue Index by Artist<strong>catalog</strong>ue number/page numberIkeda Eisen, 23/76Kitagawa Eishi, 12/54Utagawa Hiroshige, 24/78Utagawa Kunichika, 21/72Utagawa Kunisada, 3/36, 4/38, 11/52, 14/58, 15/60, 16/60, 17/60, 18/66, 19/68, 22/74, 26/82, 27/84Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 5/40, 8/46, 9/48, 10/50, 13/56, 20/70, 29/88Shunpūsha?, 7/44Katsukawa Shunsen, 6/42Utagawa Toyokuni, 25/80Kitagawa Utamaro, 2/34, 28/86Utagawa Yoshitora, 1/32Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 30/90, 31/92, 32/94, 33/96, 34/98, 35/100104“The Moon Has No Home”

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> Art Museum