Adolescent Brain Development - the Youth Advocacy Division

Adolescent Brain Development - the Youth Advocacy Division Adolescent Brain Development - the Youth Advocacy Division

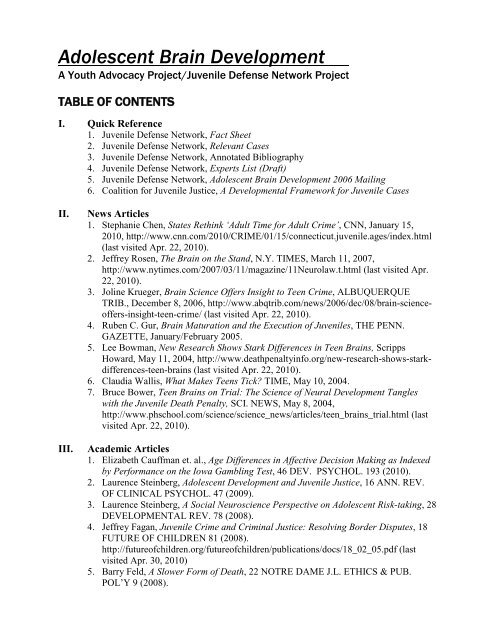

Adolescent Brain Development A Youth Advocacy Project/Juvenile Defense Network Project TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Quick Reference 1. Juvenile Defense Network, Fact Sheet 2. Juvenile Defense Network, Relevant Cases 3. Juvenile Defense Network, Annotated Bibliography 4. Juvenile Defense Network, Experts List (Draft) 5. Juvenile Defense Network, Adolescent Brain Development 2006 Mailing 6. Coalition for Juvenile Justice, A Developmental Framework for Juvenile Cases II. News Articles 1. Stephanie Chen, States Rethink ‘Adult Time for Adult Crime’, CNN, January 15, 2010, http://www.cnn.com/2010/CRIME/01/15/connecticut.juvenile.ages/index.html (last visited Apr. 22, 2010). 2. Jeffrey Rosen, The Brain on the Stand, N.Y. TIMES, March 11, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/11/magazine/11Neurolaw.t.html (last visited Apr. 22, 2010). 3. Joline Krueger, Brain Science Offers Insight to Teen Crime, ALBUQUERQUE TRIB., December 8, 2006, http://www.abqtrib.com/news/2006/dec/08/brain-scienceoffers-insight-teen-crime/ (last visited Apr. 22, 2010). 4. Ruben C. Gur, Brain Maturation and the Execution of Juveniles, THE PENN. GAZETTE, January/February 2005. 5. Lee Bowman, New Research Shows Stark Differences in Teen Brains, Scripps Howard, May 11, 2004, http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/new-research-shows-starkdifferences-teen-brains (last visited Apr. 22, 2010). 6. Claudia Wallis, What Makes Teens Tick? TIME, May 10, 2004. 7. Bruce Bower, Teen Brains on Trial: The Science of Neural Development Tangles with the Juvenile Death Penalty, SCI. NEWS, May 8, 2004, http://www.phschool.com/science/science_news/articles/teen_brains_trial.html (last visited Apr. 22, 2010). III. Academic Articles 1. Elizabeth Cauffman et. al., Age Differences in Affective Decision Making as Indexed by Performance on the Iowa Gambling Test, 46 DEV. PSYCHOL. 193 (2010). 2. Laurence Steinberg, Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice, 16 ANN. REV. OF CLINICAL PSYCHOL. 47 (2009). 3. Laurence Steinberg, A Social Neuroscience Perspective on Adolescent Risk-taking, 28 DEVELOPMENTAL REV. 78 (2008). 4. Jeffrey Fagan, Juvenile Crime and Criminal Justice: Resolving Border Disputes, 18 FUTURE OF CHILDREN 81 (2008). http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/18_02_05.pdf (last visited Apr. 30, 2010) 5. Barry Feld, A Slower Form of Death, 22 NOTRE DAME J.L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 9 (2008).

- Page 2 and 3: 6. Hillary Massey, 8 th Amendment a

- Page 4 and 5: Adolescent Brain Development Quick

- Page 6 and 7: Adolescent Brain Development Quick

- Page 8 and 9: Joline Krueger, Brain Science Offer

- Page 10 and 11: • “Although states may hold you

- Page 12 and 13: HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, THE REST OF THE

- Page 14 and 15: VII. Legal Motions from MA Motion t

- Page 16 and 17: Adolescent Brain Development Quick

- Page 18 and 19: SCOTT, ELIZABETH, J.D. Professor -

- Page 20 and 21: Footnotes: ________________________

- Page 22: Footnotes: ________________________

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

A <strong>Youth</strong> <strong>Advocacy</strong> Project/Juvenile Defense Network Project<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

I. Quick Reference<br />

1. Juvenile Defense Network, Fact Sheet<br />

2. Juvenile Defense Network, Relevant Cases<br />

3. Juvenile Defense Network, Annotated Bibliography<br />

4. Juvenile Defense Network, Experts List (Draft)<br />

5. Juvenile Defense Network, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> 2006 Mailing<br />

6. Coalition for Juvenile Justice, A <strong>Development</strong>al Framework for Juvenile Cases<br />

II. News Articles<br />

1. Stephanie Chen, States Rethink ‘Adult Time for Adult Crime’, CNN, January 15,<br />

2010, http://www.cnn.com/2010/CRIME/01/15/connecticut.juvenile.ages/index.html<br />

(last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

2. Jeffrey Rosen, The <strong>Brain</strong> on <strong>the</strong> Stand, N.Y. TIMES, March 11, 2007,<br />

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/11/magazine/11Neurolaw.t.html (last visited Apr.<br />

22, 2010).<br />

3. Joline Krueger, <strong>Brain</strong> Science Offers Insight to Teen Crime, ALBUQUERQUE<br />

TRIB., December 8, 2006, http://www.abqtrib.com/news/2006/dec/08/brain-scienceoffers-insight-teen-crime/<br />

(last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

4. Ruben C. Gur, <strong>Brain</strong> Maturation and <strong>the</strong> Execution of Juveniles, THE PENN.<br />

GAZETTE, January/February 2005.<br />

5. Lee Bowman, New Research Shows Stark Differences in Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s, Scripps<br />

Howard, May 11, 2004, http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/new-research-shows-starkdifferences-teen-brains<br />

(last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

6. Claudia Wallis, What Makes Teens Tick? TIME, May 10, 2004.<br />

7. Bruce Bower, Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s on Trial: The Science of Neural <strong>Development</strong> Tangles<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death Penalty, SCI. NEWS, May 8, 2004,<br />

http://www.phschool.com/science/science_news/articles/teen_brains_trial.html (last<br />

visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

III. Academic Articles<br />

1. Elizabeth Cauffman et. al., Age Differences in Affective Decision Making as Indexed<br />

by Performance on <strong>the</strong> Iowa Gambling Test, 46 DEV. PSYCHOL. 193 (2010).<br />

2. Laurence Steinberg, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice, 16 ANN. REV.<br />

OF CLINICAL PSYCHOL. 47 (2009).<br />

3. Laurence Steinberg, A Social Neuroscience Perspective on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Risk-taking, 28<br />

DEVELOPMENTAL REV. 78 (2008).<br />

4. Jeffrey Fagan, Juvenile Crime and Criminal Justice: Resolving Border Disputes, 18<br />

FUTURE OF CHILDREN 81 (2008).<br />

http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/18_02_05.pdf (last<br />

visited Apr. 30, 2010)<br />

5. Barry Feld, A Slower Form of Death, 22 NOTRE DAME J.L. ETHICS & PUB.<br />

POL’Y 9 (2008).

6. Hillary Massey, 8 th Amendment and Juvenile Life Without Parole after Roper, 47 B.<br />

C. L. REV. 1083 (2006).<br />

7. Staci Gruber & Deborah Yurgelun-Todd, Neurobiology and <strong>the</strong> Law: A Role in<br />

Juvenile Justice? 3 OHIO ST. J. OF CRIM. L. 321 (2006).<br />

8. Margo Gardner & Laurence Steinberg, Peer Influence on Risk Taking, Risk<br />

Preference, and Risky Decision-Making in Adolescence and Adulthood: An<br />

Experimental Study, 41 DEV. PSYCHOL. 625 (2005).<br />

9. Press Release, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, <strong>Adolescent</strong><br />

<strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation, (Feb. 25, 2004).<br />

10. Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth Scott, Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence:<br />

<strong>Development</strong>al Immaturity, Diminished Responsibility, and <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death<br />

Penalty, 58 AMER. PSYCHOL. 1009 (2003).<br />

IV. Reports and O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Advocacy</strong> Resources<br />

1. CHILD. LAW CTR. OF MASS., UNTIL THEY DIE A NATURAL DEATH:<br />

YOUTH SENTENCED TO LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE IN MASSACHUSETTS<br />

(2009).<br />

2. Wendy Paget Henderson, Life After Roper: Using <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> in<br />

Court, 11 A.B.A. CHILD. RTS 1, 1 (2009).<br />

3. Connie de la Vega & Michelle Leighton, Sentencing Our Children to Die in Prison:<br />

Global Law and Practice, 42 U.S.F.L. REV. 983 (2008).<br />

4. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, THE REST OF THEIR LIVES: LIFE WITHOUT<br />

PAROLE FOR YOUTH IN THE UNITED STATES IN 2008 (2008).<br />

5. A.B.A. RECOMMENDATION 105C, Mitigating Circumstances in Sentencing<br />

<strong>Youth</strong>ful Offenders (2008).<br />

6. Allstate Advertisement, WALL STREET JOURNAL, May 17, 2007.<br />

7. Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence, Issue Brief (MacArthur Found. Res. Network<br />

on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Dev. & Juv. Just., 2006.<br />

http://www.adjj.org/downloads/6093issue_brief_3.pdf (last visited May 19, 2010)<br />

8. National Institute of Mental Health, Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress, 2001.<br />

V. Expert Testimonies/Briefs Addressing Expert Evidence<br />

1. Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association, et al.,<br />

Graham v. Florida and Sullivan v. Florida (2009)<br />

2. Affidavit of Dr. Staci A. Gruber (2009)<br />

3. Declaration of Ruben C. Gur, Ph.D., Patterson v. Texas (2002)<br />

4. Testimony of Ruben C. Gur, Ph. D., People v. Clark, (Illinois)<br />

5. Testimony of David Fassler, M.D., New Hampshire State Legislature (2004)<br />

6. Interview with Deborah Yurgelun-Todd, PBS Frontline (2002)<br />

VI. Supreme Court Opinions<br />

1. Graham v. Florida – Majority opinion given by Justice Kennedy. Full opinion<br />

available at http://eji.org/eji/files/Decision%20in%20Graham.pdf.<br />

2. Graham v. Florida Quotes<br />

3. Roper v. Simmons – Majority opinion given by Justice Kennedy<br />

4. Atkins v. Virginia – Majority opinion given by Justice Stevens<br />

5. Thompson v. Oklahoma – Majority opinion given by Justice Stevens

VII. Legal Motions from MA<br />

1. Motion to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2009<br />

2. Memo of law to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2009<br />

3. Motion to Dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

4. Massachusetts Exhibit Appendix (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

5. Memo of Law to Dismiss (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

6. Motion to Dismiss YO (Ken King) – 2007<br />

7. Memo to Dismiss (Ken King) – 2007<br />

8. Motion for Evidentiary Hearing (Ken King) – 2007<br />

9. Motion to Dismiss (Patricia Downey) – 2005<br />

VIII. Legal Motions from O<strong>the</strong>r States<br />

1. Petitioner Brief, Sullivan v. Florida (2009)<br />

2. Petitioner Brief, Graham v. Florida (2009)<br />

3. Pennsylvania – Amici Brief<br />

4. Pennsylvania – Cover Sheet<br />

5. Alabama – Juvenile LWOP Brief<br />

6. Alabama – Sentencing Transcript<br />

7. Colorado – Flakes v. People<br />

8. Colorado – Apprendi Motion<br />

9. Colorado – Cert Petition<br />

10. Illinois – Motion Transfer Unconstitutional<br />

11. Illinois – Reply Brief<br />

12. Illinois – Appellant Brief<br />

13. New Mexico – Motion to Dismiss<br />

14. Washington, D.C. – Motion to Dismiss<br />

15. Washington, D.C. – Reply Letter<br />

16. Washington, D.C. – 2 nd Reply Letter<br />

IX. State Statutes<br />

1. 50 State Chart of JLWOP Law (National Conference of State Legislators)<br />

X. Helpful Websites<br />

1. List of helpful websites

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Quick Reference Fact Sheet<br />

Background<br />

• With <strong>the</strong> recent cases of Graham v. Florida (2010), Roper v. Simmons (2005), Atkins v. Virginia (2002), and<br />

Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), <strong>the</strong> topics of adolescent brain development and juvenile culpability have come to<br />

<strong>the</strong> forefront of juvenile criminal law. In Graham, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional to sentence<br />

juveniles convicted of non-homicide offenses to life without <strong>the</strong> possibility of parole. In Thompson and Roper, <strong>the</strong><br />

Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional to give <strong>the</strong> death penalty to juveniles (Thompson set <strong>the</strong> age limit to<br />

16, Roper to 18). In each of <strong>the</strong>se cases, <strong>the</strong> underlying rationale was that juvenile offenders tend to lack maturity<br />

(both socially and biologically), are more reckless, are more susceptible to peer pressure, and are more vulnerable<br />

to <strong>the</strong>ir surroundings than adults. In both Graham and Atkins, <strong>the</strong> topic of brain development played a crucial role<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Court determining that <strong>the</strong> sentence in question was not appropriate in light of <strong>the</strong> lessened culpability of<br />

<strong>the</strong> category of offenders challenging <strong>the</strong> sentence (juveniles in Graham, mentally retarded individuals in Atkins).<br />

Indeed, <strong>the</strong> Graham decision went as far as stating that “An offender’s age is relevant to <strong>the</strong> 8 th amendment, and<br />

criminal procedure laws that fail to take defendants’ youthfulness into account at all would be flawed.” Graham v.<br />

Florida, No. 08-7412, slip. op at 25, 560 U.S. __ (2010)<br />

• <strong>Adolescent</strong> brain development has become an increasingly accurate field of research in recent years due to <strong>the</strong><br />

development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedures. Prior to <strong>the</strong> use of MRI technology, <strong>the</strong> only<br />

major studies that had been performed involved post-mortem (cadaver) tissue, since X-rays and o<strong>the</strong>r means of<br />

testing were deemed potentially harmful to youth. MRI technology allows for <strong>the</strong> same subject to be tracked from<br />

infancy into adulthood. 1<br />

• States and <strong>the</strong> federal government generally do not recognize youth as being mature enough to handle many<br />

situations. For example, youth cannot drive until age 16 (varies by state, w/ most adopting restrictions on under 18<br />

drivers), or see rated R movies without adult supervision until <strong>the</strong>y are 17. They cannot vote, smoke, sign<br />

contracts, enter military services, or get married (varies by state) until age 18. And lastly, <strong>the</strong>y cannot drink until<br />

age 21. The implications of <strong>the</strong>se social norms indicates that society does not fully trust youth with many<br />

privileges, and thus do not consider <strong>the</strong>m as responsible as adults. 2<br />

Implications<br />

• As compared to adults, juveniles have a “‘lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility’”; <strong>the</strong>y<br />

“are more vulnerable or susceptible to negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure”; and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir characters are “not as well formed.” 3<br />

• “The evidence is strong that <strong>the</strong> brain does not cease to mature until <strong>the</strong> early 20s in those relevant parts that<br />

govern impulsivity, judgment, planning for <strong>the</strong> future, foresight of consequences, and o<strong>the</strong>r characteristics that<br />

make people morally culpable.” 4<br />

• “Neuroscientists have been able to demonstrate conclusively that mental maturation follows closely <strong>the</strong> time<br />

course of brain maturation. Thus, juveniles have to rely on <strong>the</strong> abilities of <strong>the</strong>ir still immature brains, and no<br />

amount of social intervention or self-motivation can appreciably influence <strong>the</strong> biological processes involved in<br />

brain maturation.” 5<br />

• “The cortical regions that are last to mature… are involved in behavioral facets germane to many aspects of<br />

criminal culpability. Perhaps most relevant is <strong>the</strong> involvement of <strong>the</strong>se brain regions in <strong>the</strong> control of aggression<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r impulses, <strong>the</strong> process of planning for long-range goals, organization of sequential behavior,<br />

consideration of alternatives and consequences, <strong>the</strong> process of abstraction and mental flexibility, and aspects of<br />

memory including ‘working memory.’… If <strong>the</strong> neural substrates of <strong>the</strong>se behaviors have not reached maturity<br />

before adulthood, it is unreasonable to expect <strong>the</strong> behaviors <strong>the</strong>mselves to reflect mature thought processes.”<br />

[Emphasis Added]. 6

Scientific Backing<br />

• Myelination is <strong>the</strong> main index by which brain maturity is measured. Myelin implies more mature, efficient<br />

connections, within <strong>the</strong> brain’s ‘gray matter.’ UCLA researchers performed a study comparing myelination of<br />

young adults aged 23-30 with adolescents aged 12-16. They found that <strong>the</strong>re was a stark contrast in <strong>the</strong><br />

myelination, especially in <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe and frontal cortex, <strong>the</strong> areas that relate to <strong>the</strong> maturation of cognitive<br />

processing and o<strong>the</strong>r ‘executive functions.’ 7<br />

• According to studies using advances in MRI technology, <strong>the</strong> area of <strong>the</strong> brain (frontal lobe) that is most related to<br />

decision making, planning, risk-assessment, judgment, and o<strong>the</strong>r factors generally associated with criminal<br />

culpability is also one of <strong>the</strong> last to fully mature. 8<br />

• According to research conducted by Lawrence Steinberg, a noted Professor of Psychology at Temple University,<br />

“risky behavior in adolescence is <strong>the</strong> product of <strong>the</strong> interaction between changes in two distinct neurobiological<br />

systems: a socioemotional system [which includes <strong>the</strong> amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex]. . . and a cognitive<br />

control system.” 9 Steinberg has noted that “changes in <strong>the</strong> socioemotional system at puberty may promote<br />

reckless, sensation-seeking behavior in early and middle adolescence, while <strong>the</strong> regions of <strong>the</strong> prefrontal cortex<br />

that govern cognitive control continue to mature over <strong>the</strong> course of adolescence and into young adulthood. This<br />

temporal gap between <strong>the</strong> increase in sensation seeking around puberty and <strong>the</strong> later development of mature selfregulatory<br />

competence may combine to make adolescence a time of inherently immature judgment. Thus, despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that in many ways adolescents may appear to be as intelligent as adults (at least as indexed by<br />

performance on tests of information processing and logical reasoning), <strong>the</strong>ir ability to regulate <strong>the</strong>ir behavior in<br />

accord with <strong>the</strong>se advanced intellectual abilities is more limited.” 10<br />

• According to a study at Harvard’s McLean Hospital, young teens tend to rely more on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain<br />

(amygdala) responsible for fear and o<strong>the</strong>r ‘gut reactions’ when responding to o<strong>the</strong>r people’s emotions. Adults in<br />

contrast, more often utilize <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe, <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain which yields more reasoned perceptions. 11<br />

• According to a study performed by researches using MRI technology at <strong>the</strong> National Institute on Alcohol Abuse<br />

and Alcoholism, adolescents use lower activation of <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain that is “crucial for motivating behavior<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> prospect of rewards.” The study concludes that youth differ significantly in <strong>the</strong>ir responses to “rewarddirected<br />

behavior.” 12<br />

• The production of testosterone, a hormone that is closely associated with aggression, increases approximately<br />

tenfold in adolescent boys. 13<br />

1<br />

American Bar Association (ABA): Juvenile Justice Center. Adolescence, <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Legal Culpability. 2004.<br />

2<br />

Fagan, Jeffrey. “<strong>Adolescent</strong>s, Maturity, and <strong>the</strong> Law. The American Prospect. August, 2005.<br />

3<br />

Graham v. Florida, No. 08-7412, slip. op. at 17, 560 U.S. __ (2010) (quoted from Roper v. Simmons 543 U.S. at 569-570 (2005)).<br />

4<br />

Gur, Ruben C., Ph.D. Declaration of Ruben C. Gur. Patterson v. Texas. Petition for Writ of Certiorari to US Supreme Court, J. Gary<br />

Hart, Counsel. (2002).<br />

5<br />

Gur, op. cit.<br />

6<br />

Gur, op. cit.<br />

7<br />

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress. A brief overview of research into brain<br />

development during adolescence. 2001. See also: Sowell, Elizabeth, et al. In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in<br />

frontal and striatal regions. Nature Neuroscience, 1999; 2(10): 859-861.<br />

8<br />

Fagan, op, cit. See also: Goldberg, Elkhonon. The Executive <strong>Brain</strong>, Frontal Lobes and <strong>the</strong> Civilized Mind, (2001).<br />

9<br />

Lawrence Steinberg, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice, ANNU. REV. CLIN. PSYCHOL. 2009. 5:47–73 at 54.<br />

10<br />

Id. at 55.<br />

11<br />

NIMH, op cit. See also: Baird, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of facial affect recognition in children and adolescents.<br />

Journal of <strong>the</strong> American Academy of Child and <strong>Adolescent</strong> Psychiatry, 1999; 38(2): 195-9.<br />

12<br />

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation, 2004.<br />

13<br />

See Adams, Gerald R., Montemayor, Raymond, and Gullota, Thomas P., eds. Psychosocial <strong>Development</strong> during Adolescence. Sage<br />

Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. (1996).

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Quick Reference Relevant Cases<br />

GRAHAM v. FLORIDA (2010)<br />

In Graham, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court declared life without parole sentences for nonhomicide offenders under age 18<br />

unconstitutional. This decision marked <strong>the</strong> first time that <strong>the</strong> court declared a non-capital punishment to be cruel and<br />

unusual for an entire category of offenders. Although <strong>the</strong> holding of Graham arguably does not apply directly in<br />

Massachusetts, much of <strong>the</strong> language is broad enough that it can apply to juveniles who committed homicides as well as<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r offenses. Notably, <strong>the</strong>re is language indicating that life without parole sentences may not be appropriate for<br />

juveniles who “did not kill or intend to kill”, Graham v. Florida, No. 08-7412, slip. op. at 18, 560 U.S. __ (2010), as well<br />

as o<strong>the</strong>r language noting that “juvenile offenders cannot with reliability be classified among <strong>the</strong> worst offender” Id. at 17<br />

(quoting Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 853 (1988)) and that “[a]n offender’s age is relevant to <strong>the</strong> 8 th amendment, and<br />

criminal procedure laws that fail to take defendants’ youthfulness into account at all would be flawed.” Id. at 25. The<br />

court also noted that “[b]ecause ‘[t]he age of 18 is <strong>the</strong> point where society draws <strong>the</strong> line for many purposes between<br />

childhood and adulthood,’ those who were below that age when <strong>the</strong> offense was committed may not be sentenced to life<br />

without parole for a nonhomicide crime.” Id. at 24 (quoting Roper v. Simmons 543 U.S. at 574 (2005))<br />

ROPER v SIMMONS (2005)<br />

The March 2005 Supreme Court ruling in Roper finally outlawed <strong>the</strong> death penalty for juvenile offenders. Though <strong>the</strong><br />

majority opinion did not specifically mention recent scientific studies regarding differences between <strong>the</strong> adolescent brain<br />

and <strong>the</strong> adult brain, <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association (APA) submitted a brief to <strong>the</strong> court in regards to <strong>the</strong> recent<br />

developments. Significantly, <strong>the</strong> scientific evidence presented by <strong>the</strong> APA was not challenged by ei<strong>the</strong>r side, something<br />

that had been done in prior decisions regarding <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty.<br />

ATKINS v VIRGINIA (2002)<br />

Atkins was <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court case that outlawed <strong>the</strong> death penalty for mentally retarded offenders, and set in motion <strong>the</strong><br />

ruling that was decided in Roper. Atkins is perhaps <strong>the</strong> most relevant case toward adolescent brain development<br />

specifically, as it <strong>the</strong> practice of executing mentally retarded offenders was declared unconstitutional under <strong>the</strong> Eighth<br />

Amendment (Cruel & Unusual Punishment). Justice Stevens delivered <strong>the</strong> Court’s Opinion, specifically noting that<br />

“because of [mentally retarded persons’] disabilities in areas of reasoning, judgment, and control of <strong>the</strong>ir impulses,<br />

however, <strong>the</strong>y do not act with <strong>the</strong> level of moral culpability that characterizes <strong>the</strong> most serious adult criminal conduct.”<br />

With adolescent brain development studies demonstrating that most adolescents do not fully develop <strong>the</strong> parts of <strong>the</strong> brain<br />

that deal specifically with reasoning, weighing of long-term goals, and instead tend to use <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain responsible<br />

for making “gut reactions,” <strong>the</strong> Atkins case has significant implications.<br />

PATTERSON v TEXAS (2002)<br />

In <strong>the</strong> case of Patterson v Texas, <strong>the</strong> Declaration of Ruben C. Gur, Ph.D. was submitted in appeals to bolster <strong>the</strong> argument<br />

that <strong>the</strong> defendant, a juvenile at <strong>the</strong> time of <strong>the</strong> accused crime, did not have a fully developed brain, and <strong>the</strong>refore was less<br />

culpable. The decision stated in part that “<strong>the</strong> evidence is strong that <strong>the</strong> brain does not cease to mature until <strong>the</strong> early 20s<br />

in those relevant parts that govern impulsivity, judgment, planning for <strong>the</strong> future, foresight of consequences, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

characteristics that make people morally culpable.” Dr. Gur’s findings were reiterated in <strong>the</strong> petition for writ of certiorari.<br />

The ruling on Patterson was held however, and <strong>the</strong> accused was executed by <strong>the</strong> State of Texas in August, 2002.<br />

THOMPSON v OKLAHOMA (1988)<br />

Thompson was <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court case where <strong>the</strong> age limit for <strong>the</strong> death penalty was officially moved up to 16. Although<br />

MRI technology was unavailable to demonstrate scientific reasoning for different brain development, <strong>the</strong> Thompson case<br />

is still vital as <strong>the</strong> court differentiated <strong>the</strong> culpability of a 15-year old from that of an adult in <strong>the</strong> context of a “heinous<br />

crime.” The decision on Thompson played a critical role as precedent for <strong>the</strong> findings in Roper.

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Annotated Bibliography<br />

I. Quick Reference<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Fact Sheet<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Relevant Cases<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Annotated Bibliography<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, Experts List (Draft)<br />

Juvenile Defense Network, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> 2006 Mailing<br />

Coalition for Juvenile Justice, A <strong>Development</strong>al Framework for Juvenile Cases<br />

II. News Articles<br />

Stephanie Chen, States Rethink ‘Adult Time for Adult Crime’, CNN, January 15, 2010,<br />

http://www.cnn.com/2010/CRIME/01/15/connecticut.juvenile.ages/index.html (last visited Apr. 22,<br />

2010).<br />

• Discusses state efforts to raise age of automatic adult court jurisdiction, focusing on Connecticut,<br />

which changed age from 16 to 17. Also quotes psychologist Laurence Steinberg comparing <strong>the</strong><br />

teenage brain to “a car with a good accelerator but a weak brake.”<br />

Jeffrey Rosen, The <strong>Brain</strong> on <strong>the</strong> Stand, N.Y. TIMES, March 11, 2007,<br />

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/11/magazine/11Neurolaw.t.html (last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

• Discusses <strong>the</strong> use of neuroscience in criminal law generally and explores debate over <strong>the</strong><br />

relevance of neuroscience to law. Includes interviews with a lot of <strong>the</strong> experts who are at <strong>the</strong><br />

forefront of brain science as it applies to juvenile justice. Pages 3-4 of Section III include<br />

discussion of psychologist Ruben Gur’s expert testimony and <strong>the</strong> use of “neurolaw” in Roper.<br />

Ruben C. Gur, <strong>Brain</strong> Maturation and <strong>the</strong> Execution of Juveniles, THE PENN. GAZETTE,<br />

January/February 2005.<br />

• Article written by a psychiatrist describing <strong>the</strong> use of brain research in advocating against<br />

imposition of <strong>the</strong> death penalty on older adolescents.<br />

• “The evidence now is strong that <strong>the</strong> brain does not cease to mature until <strong>the</strong> early 20s in those<br />

relevant parts that govern impulsivity, judgment, planning for <strong>the</strong> future, foresight of<br />

consequences, and o<strong>the</strong>r characteristics that make people morally culpable. Therefore, from <strong>the</strong><br />

perspective of neural development, someone under 20 should be considered to have an<br />

underdeveloped brain. Additionally, since brain development in <strong>the</strong> relevant areas goes in phases<br />

that vary in rate and is usually not complete before <strong>the</strong> early to mid-20s, <strong>the</strong>re is no way to state<br />

with any scientific reliability that an individual 17-year-old has a fully matured brain (and should<br />

be eligible for <strong>the</strong> most severe punishment), no matter how many o<strong>the</strong>rwise accurate tests and<br />

measures might be applied to him at <strong>the</strong> time of his trial for capital murder.” (*4)

Joline Krueger, <strong>Brain</strong> Science Offers Insight to Teen Crime, ALBUQUERQUE TRIB., December 8,<br />

2006, http://www.abqtrib.com/news/2006/dec/08/brain-science-offers-insight-teen-crime/ (last visited<br />

Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

• Brief article discussing brain development and question of why adolescents act without thinking.<br />

“Cerebral construction is not complete until around ages 20 to 25, most scientists agree. The<br />

frontal lobe is one of <strong>the</strong> last areas of <strong>the</strong> brain to develop. In <strong>the</strong> adolescent brain, it's barely<br />

firing at all. Without <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe on board, it becomes physiologically harder for a teen to<br />

completely understand <strong>the</strong> future consequences of his or her emotional or impulsive actions,<br />

scientists contend.”<br />

Lee Bowman, New Research Shows Differences in Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s, Scripps Howard, May 11, 2004,<br />

http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/new-research-shows-stark-differences-teen-brains (last visited Apr. 22,<br />

2010).<br />

• Explains how while teens’ bodies maybe fully developed, <strong>the</strong>ir brains are nowhere near full<br />

maturity, especially in <strong>the</strong> areas related to culpability.<br />

• “Deborah Yurgelun-Todd of Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital in Boston has studied<br />

how teenagers and adults respond differently to <strong>the</strong> same images. Shown a set of photos of<br />

people's faces contorted in fear, adults named <strong>the</strong> right emotion, but teens seldom did, often<br />

saying <strong>the</strong> person was angry. … Adults used both <strong>the</strong> advanced prefrontal cortex and <strong>the</strong> more<br />

basic amygdala to evaluate what <strong>the</strong>y had seen; younger teens relied entirely on <strong>the</strong> amygdala,<br />

while older teens (top age in <strong>the</strong> group was 17) showed a progressive shift toward using <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal area of <strong>the</strong> brain. ‘Just because teens are physically mature, <strong>the</strong>y may not appreciate <strong>the</strong><br />

consequences or weigh information <strong>the</strong> same way as adults do,’ Yurgelun-Todd said. ‘Good<br />

judgment is learned, but you can't learn it if you don't have <strong>the</strong> necessary hardware.’”<br />

Claudia Wallis, What Makes Teens Tick? TIME, May 10, 2004,<br />

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,994126,00.html (last visited Apr. 22, 2010).<br />

• Discusses <strong>the</strong> new technology, processes, and findings relating to brain development (as of 2004).<br />

Cites many of <strong>the</strong> leading brain researchers in <strong>the</strong> field.<br />

• “The very last part of <strong>the</strong> brain to be pruned and shaped to its adult dimensions is <strong>the</strong> prefrontal<br />

cortex, home of <strong>the</strong> so-called executive functions--planning, setting priorities, organizing<br />

thoughts, suppressing impulses, weighing <strong>the</strong> consequences of one's actions. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong><br />

final part of <strong>the</strong> brain to grow up is <strong>the</strong> part capable of deciding, I'll finish my homework and take<br />

out <strong>the</strong> garbage, and <strong>the</strong>n I'll IM my friends about seeing a movie.” (4)<br />

Bruce Bower, Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s on Trial: The Science of Neural <strong>Development</strong> Tangles with <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death<br />

Penalty, SCIENCE NEWS, May 8, 2004,<br />

http://www.phschool.com/science/science_news/articles/teen_brains_trial.html (last visited Apr. 22,<br />

2010).<br />

• A good overview of <strong>the</strong> science involved and its application to <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty.<br />

• “‘Our objection to <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty is rooted in <strong>the</strong> fact that adolescents' brains function<br />

in fundamentally different ways than adults' brains do,’ says David Fassler, a psychiatrist at <strong>the</strong><br />

University of Vermont in Burlington and a leader of <strong>the</strong> effort to infuse capital-crime laws with<br />

brain science.<br />

Age-related brain differences pack a real-world wallop, in his view. ‘From a biological<br />

perspective,’ Fassler asserts, ‘an anxious adolescent with a gun in a convenience store is more<br />

likely to perceive a threat and pull <strong>the</strong> trigger than is an anxious adult with a gun in <strong>the</strong> same<br />

store.’” (1)

III. Academic Articles<br />

Elizabeth Cauffman et. al., Age Differences in Affective Decision Making as Indexed by Performance on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Iowa Gambling Test, DEV. PSYCHOL., 193 (2010).<br />

• Study showing that adolescents perform more poorly than adults in decision-making tasks where<br />

affective processing is involved and respond differently to rewards.<br />

• “[D]ecision making, which frequently precedes engaging in risk-taking behavior, indeed<br />

improves throughout adolescence and into young adulthood … this improvement may be due not<br />

to cognitive maturation but to changes in affective processing. Whereas adolescents may attend<br />

more to <strong>the</strong> potential rewards of a risky decision than to <strong>the</strong> potential costs, adults tend to<br />

consider both, even weighing costs more than rewards.<br />

This higher level of approach behavior during adolescence coupled with <strong>the</strong> lesser inclination<br />

toward harm avoidance may help explain increased novelty-seeking in adolescence, which can<br />

lead to various types of risk taking, including experimentation with drugs, unprotected sex, and<br />

delinquent activity.” (206)<br />

Laurence Steinberg, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice, 16 ANN. REV. OF CLINICAL<br />

PSYCHOL. 47 (2008).<br />

• Excellent overview of adolescent development research. Outlines <strong>the</strong> implications of adolescent<br />

brain, cognitive, and psychosocial development on culpability, competence to stand trial, and<br />

impact of sanctions on adolescents.<br />

Laurence Steinberg, A Social Neuroscience Perspective on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Risk-taking, 28<br />

DEVELOPMENTAL REV. 78 (2008).<br />

• Summarizes brain development research and discusses why risk-taking behavior increases from<br />

childhood to adolescence and decreases from adolescence to adulthood.<br />

• “As a consequence of [neural transformations], relative to prepubertal individuals, adolescents<br />

who have gone through puberty are more inclined to take risks in order to gain rewards, an<br />

inclination that is exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> presence of peers. This increase in reward-seeking … has<br />

its onset around <strong>the</strong> onset of puberty, and likely peaks sometime around age 15, after which it<br />

begins to decline. Behavioral manifestations of <strong>the</strong>se changes are evident in a wide range of<br />

experimental and correlational studies using a diverse array of tasks and self-report instruments<br />

… and are logically linked to well-documented structural and functional changes in <strong>the</strong> brain.”<br />

(92)<br />

Jeffrey Fagan, Juvenile Crime and Criminal Justice: Resolving Border Disputes, 18 FUTURE OF<br />

CHILDREN 81 (2008). http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/18_02_05.pdf (last<br />

visited Apr. 30, 2010)<br />

• “Without exception <strong>the</strong> research evidence shows that policies promoting transfer of adolescents<br />

from juvenile to criminal court fail to deter crime among sanctioned juveniles and may even<br />

worsen public safety risks. The weight of empirical evidence strongly suggests that increasing<br />

<strong>the</strong> scope of transfer has no general deterrent effects on <strong>the</strong> incidence of serious juvenile crime or<br />

specific deterrent effects on <strong>the</strong> re-offending rates of transferred youth. In fact, compared with<br />

youth retained in juvenile court, youth prosecuted as adults had higher rates of rearrest for serious<br />

felony crimes such as robbery and assault. They were also rearrested more quickly and were<br />

more often returned to incarceration.” (105)<br />

Barry Feld, A Slower Form of Death, 22 NOTRE DAME J.L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 9 (2008).<br />

• Argues that <strong>the</strong> diminished responsibility rationale in Roper should be extended by state<br />

legislatures to recognize youthfulness as a categorical mitigating factor in sentencing.

• “Although states may hold youths accountable for <strong>the</strong> harms <strong>the</strong>y cause, Roper explicitly limited<br />

<strong>the</strong> severity of <strong>the</strong> sentence a state could impose on <strong>the</strong>m because of <strong>the</strong>ir diminished<br />

responsibility. Even after youths develop <strong>the</strong> nominal ability to distinguish right from wrong,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir bad decisions lack <strong>the</strong> same degree of moral blameworthiness as those of adults and warrant<br />

less severe punishment.” (3)<br />

• “The court [in Roper] recognized that youths are more impulsive, seek exciting and dangerous<br />

experiences, and prefer immediate rewards to delayed gratification. They misperceive and<br />

miscalculate risks and discount <strong>the</strong> likelihood of bad consequences. They succumb to negative<br />

peer and adverse environmental influences. All of <strong>the</strong>se normal characteristics increase <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

likelihood of causing devastating injuries to <strong>the</strong>mselves and to o<strong>the</strong>rs. Although <strong>the</strong>y are just as<br />

capable as adults of causing great harm, <strong>the</strong>ir immature judgment and lack of self-control reduces<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir culpability and warrants less-severe punishment.” (6)<br />

• “Roper’s diminished responsibility rationale provides a broader foundation to formally recognize<br />

youthfulness as a categorical mitigating factor in sentencing. Because adolescents lack <strong>the</strong><br />

judgment, appreciation of consequences, and self-control of adults, <strong>the</strong>y deserve shorter sentences<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y cause <strong>the</strong> same harms. <strong>Adolescent</strong>s’ personalities are in transition, and it is unjust and<br />

irrational to continue harshly punishing a fifty- or sixty-year-old person for <strong>the</strong> crime that an<br />

irresponsible child committed several decades earlier.” (10)<br />

Hillary Massey, 8 th Amendment and Juvenile Life Without Parole after Roper, 47 B. C. L. REV. 1083<br />

(2006).<br />

• Argues for elimination or limitation of JLWOP based on proportionality review and diminished<br />

culpability of juveniles.<br />

• “The psychosocial research shows strong differences between adolescents and adults that<br />

implicate assessments of culpability. Researchers have identified four psychosocial factors that<br />

affect <strong>the</strong> way adolescents make decisions, including whe<strong>the</strong>r to commit a crime or an antisocial<br />

act: peer influence, attitude toward risk, future orientation, and capacity for self-management. In<br />

one study, adolescents on average scored significantly lower than adults on <strong>the</strong>se factors and<br />

displayed less sophistication in decision making. Although individual levels of <strong>the</strong>se factors are<br />

more predictive of antisocial decision making than chronological age alone, researchers found<br />

that <strong>the</strong> period between ages sixteen and nineteen is an important transition point in psychosocial<br />

development.” (1090)<br />

Staci Gruber & Deborah Yurgelun-Todd, Neurobiology and <strong>the</strong> Law: A Role in Juvenile Justice? 3 OHIO<br />

ST. J. OF CRIM. L. 321 (2006).<br />

• Summarizes adolescent neurobiology research and argues that brain differences due to immature<br />

development, like brain differences due to disease, be taken into account in justice system.<br />

• “[N]eurobiological studies … indicate that <strong>the</strong> cerebral cortex undergoes a dynamic course of<br />

metabolic maturation that persists at least until <strong>the</strong> age of eighteen. … Younger, less cortically<br />

mature adolescents may be more at risk for engaging in impulsive behavior than <strong>the</strong>ir older peers<br />

for two reasons. First, <strong>the</strong>ir developing brains are more susceptible to <strong>the</strong> neurological effects of<br />

external influences such as peer pressure. Second, <strong>the</strong>y may make poor decisions because <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

cognitively less able to select behavioral strategies associated with self-regulation, judgment, and<br />

planning that would reduce <strong>the</strong> effects of environmental risk factors for engaging in such<br />

behaviors.” (330)<br />

• Steps for defense attorneys to take to understand a client’s state of mind and baseline levels of<br />

functioning are listed on p. 332.

Margo Gardner & Laurence Steinberg, Peer Influence on Risk Taking, Risk Preference, and Risky<br />

Decision-Making in Adolescence and Adulthood: An Experimental Study, 41 DEV. PSYCHOL. 625<br />

(2005).<br />

• Study finding that exposure to peers during a risk taking task doubled <strong>the</strong> amount of risky<br />

behavior among mid-adolescents (with a mean age of 14), increased it by 50 percent among<br />

college undergraduates (with a mean age of 19), and had no impact at all among young adults.<br />

• “[T]he presence of peers makes adolescents and youth, but not adults, more likely to take risks<br />

and more likely to make risky decisions.” (634)<br />

Press Release, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced<br />

Reward Anticipation, (Feb. 25, 2004). http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/feb2004/niaaa-25.htm (last visited<br />

May 19, 2010)<br />

• Discusses how adolescents’ brains respond differently to incentives (risk/reward). Cites MRI<br />

study conducted on 12-17 year old and 22-28 year old subjects.<br />

• “<strong>Adolescent</strong>s show less activity than adults in brain regions that motivate behavior to obtain<br />

rewards, according to results from <strong>the</strong> first magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study to examine<br />

real-time adolescent response to incentives.” (1)<br />

Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth Scott, Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence: <strong>Development</strong>al Immaturity,<br />

Diminished Responsibility, and <strong>the</strong> Juvenile Death Penalty, 58 AMER. PSYCHOL. 1009 (2003).<br />

• Explains from a medical standpoint how adolescent brain development affects culpability<br />

• “In general, adolescents use a risk-reward calculus that places relatively less weight on risk, in<br />

relation to reward, than that used by adults.” (1012)<br />

• “The vast majority of adolescents who engage in criminal or delinquent behavior desist from<br />

crime as <strong>the</strong>y mature.” (note 13, at 1015)<br />

IV. Reports and O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Advocacy</strong> Resources<br />

CHILDREN’S LAW CTR. OF MASS., UNTIL THEY DIE A NATURAL DEATH: YOUTH<br />

SENTENCED TO LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE IN MASSACHUSETTS (2009).<br />

• Study examining <strong>the</strong> imposition of juvenile life without parole in Massachusetts. Includes<br />

discussion of MA law, adolescent brain and developmental research, statistics and vignettes about<br />

<strong>the</strong> youth sentenced to LWOP in MA, discussion of <strong>the</strong> experiences of youth in adult prisons,<br />

analysis of economic costs of <strong>the</strong> sentencing practice, and a summary of global sentencing<br />

practices with respect to juvenile life without parole.<br />

Wendy Paget Henderson, Life After Roper: Using <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> in Court, 11 CHILD.<br />

RTS 1, 1 (2009).<br />

• <strong>Advocacy</strong> guide for using adolescent brain research in litigation prepared by A.B.A. Children’s<br />

Rights Litigation Committee. Issues addressed include competence, sentencing mitigation,<br />

duress and coercion, differences in assessing reasonableness and recklessness for juveniles, and<br />

mental responsibility.<br />

Connie de la Vega & Michelle Leighton, Sentencing Our Children to Die in Prison: Global Law and<br />

Practice, 42 U.S.F.L. REV. 983 (2008).<br />

• Examines international norms and practices regarding juvenile life without parole.<br />

• “The United States is <strong>the</strong> only violator of <strong>the</strong> international human rights standard prohibiting<br />

juvenile LWOP sentences. With thousands of juveniles serving LWOP sentences, and none<br />

serving such sentences in <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong> United States is <strong>the</strong> only country now violating<br />

this standard” (990)

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, THE REST OF THEIR LIVES: LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE FOR YOUTH<br />

IN THE UNITED STATES IN 2008 (2008).<br />

• Executive Summary of report examining juvenile life without parole in <strong>the</strong> U.S. Discusses<br />

crimes that can lead to LWOP, sentencing practices across <strong>the</strong> states, racially discriminatory<br />

sentencing, violent experiences that youth have had in prison, international standards regarding<br />

JLWOP, and recommendations for legislatures. Updated in 2008.<br />

A.B.A. RECOMMENDATION 105C, Mitigating Circumstances in Sentencing <strong>Youth</strong>ful Offenders<br />

(2008).<br />

• ABA Recommendation calling for less punitive sentences for children under 18, recognition of<br />

youth as a mitigating factor in sentencing, and parole or early release eligibility for youthful<br />

offenders.<br />

• “The American Bar Association has a long history of recognizing that youth under 18 who are<br />

involved with <strong>the</strong> justice system should be treated differently than those who are 18 or older.<br />

• The ABA’s overall approach to juvenile justice policies has been and continues to be to strongly<br />

protect <strong>the</strong> rights of youthful offenders within all legal processes while insuring public safety.<br />

Central to this ABA premise is <strong>the</strong> understanding that youthful offenders have lesser culpability<br />

than adult offenders due to <strong>the</strong> typical behavioral characteristics inherent in adolescence. It is<br />

understood that <strong>the</strong>y can and do commit delinquent and criminal acts that have an impact on<br />

public safety, but <strong>the</strong>se actors none<strong>the</strong>less are developmentally different. They are not adults and<br />

do not have fully-formed adult characteristics.” (Introduction)<br />

Allstate Advertisement, WALL STREET JOURNAL, May 17, 2007.<br />

• Insurance ad advocating for graduated driver licensing laws on <strong>the</strong> basis of adolescent brain<br />

development. The ad pictures an image of a brain with a car-shaped hole and reads, “Why do<br />

most 16-year-olds drive like <strong>the</strong>y’re missing a part of <strong>the</strong>ir brain? BECAUSE THEY ARE.”<br />

• “Even bright, mature teenagers sometimes do things that are ‘stupid.’<br />

But when that happens, it’s not really <strong>the</strong>ir fault. It’s because <strong>the</strong>ir brain hasn’t finished<br />

developing. The underdeveloped area is called <strong>the</strong> dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex. It plays a<br />

critical role in decision making, problem solving and understanding future consequences of<br />

today’s actions. Problem is, it won’t be fully mature until <strong>the</strong>y’re into <strong>the</strong>ir 20s.”<br />

Less Guilty By Reason of Adolescence, Issue Brief (MacArthur Found. Res. Network on <strong>Adolescent</strong> Dev.<br />

& Juv. Just., 2006. http://www.adjj.org/downloads/6093issue_brief_3.pdf (last visited May 19, 2010)<br />

- Explains “immaturity gap” in adolescents who are intellectually mature but more impulsive,<br />

short-sighted, and susceptible to peer influence than adults, and argues that juveniles are less<br />

culpable than adults because of <strong>the</strong>ir immaturity. Advocates for a separate system for juvenile<br />

offenders.<br />

ABA Online: Adolescence, <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Legal Culpability, (2004)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/Adolescence.pdf (.pdf. format)<br />

• Concise overview of <strong>the</strong> implications of adolescent brain development science on <strong>the</strong> juvenile<br />

justice system<br />

National Institute of Mental Health, Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress (2001).<br />

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/teenbrain.cfm<br />

• Brief article summarizing some of <strong>the</strong> teenage brain studies performed by 2001.<br />

• “Using functional MRI (fMRI), a team led by Dr. Deborah Yurgelun-Todd at Harvard's McLean<br />

Hospital scanned subjects' brain activity while <strong>the</strong>y identified emotions on pictures of faces<br />

displayed on a computer screen. Young teens, who characteristically perform poorly on <strong>the</strong> task,

activated <strong>the</strong> amygdala, a brain center that mediates fear and o<strong>the</strong>r "gut" reactions, more than <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal lobe. As teens grow older, <strong>the</strong>ir brain activity during this task tends to shift to <strong>the</strong> frontal<br />

lobe, leading to more reasoned perceptions and improved performance. Similarly, <strong>the</strong> researchers<br />

saw a shift in activation from <strong>the</strong> temporal lobe to <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe during a language skills task,<br />

as teens got older.” (2)<br />

V. Expert Testimony/Briefs<br />

Petitioner Brief, Graham v. Florida (2010)<br />

Successful Supreme Court brief arguing against juvenile life without parole for non-homicide offenses<br />

committed by juveniles under 18. Cites Roper and adolescent brain research extensively.<br />

Petitioner Brief, Sullivan v. Florida (2009)<br />

Brief arguing against juvenile life without parole for non-homicide offense committed by 13-year-old.<br />

Cites Roper and adolescent brain research extensively.<br />

Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association, et al., Sullivan and Graham (2009)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/publiced/preview/briefs/pdfs/07-08/08-7412_PetitionerAmCu4HealthOrgs.pdf<br />

The APA and o<strong>the</strong>rs’ amicus brief in Sullivan and Graham that cites heavily to new brain science<br />

Testimony of David Fassler, M.D., New Hampshire State Legislature (2004)<br />

http://ccjr.policy.net/relatives/22020.pdf (.pdf format)<br />

Testimony given to <strong>the</strong> State Legislature of New Hampshire in efforts to outlaw <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty<br />

in <strong>the</strong> state (relies heavily on brain development arguments)<br />

Declaration of Ruben C. Gur, Ph.D., Patterson v. Texas (2002)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/Gur%20affidavit.pdf (.pdf format)<br />

Declaration in Patterson v. Texas (juvenile death penalty case) citing heavily upon recent science<br />

regarding adolescent brain development<br />

VI. Supreme Court Opinions<br />

Graham v. Florida – 560 U.S. ____ (2010)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared life without parole unconstitutional for juvenile offenders under 18<br />

convicted of nonhomicide crimes.<br />

Quotes from Graham v. Florida<br />

Potentially useful language from <strong>the</strong> Graham decision.<br />

Roper v. Simmons – 543 U.S. 551 (2005)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared <strong>the</strong> juvenile death penalty unconstitutional and discusses <strong>the</strong><br />

developmental differences between juveniles under age 18 and adults.<br />

Atkins v. Virginia – 536 U.S. 304 (2002)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared <strong>the</strong> death penalty for mentally retarded persons unconstitutional (uses<br />

arguments of brain development)<br />

Thompson v. Oklahoma – 487 U.S. 815 (1988)<br />

Supreme Court case that declared <strong>the</strong> death penalty illegal for youth under <strong>the</strong> age of 16.

VII. Legal Motions from MA<br />

Motion to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2009<br />

Memo of law to dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) –<br />

2009<br />

Motion to Dismiss YO (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

Massachusetts Exhibit Appendix (Jack Cunha) –<br />

2007<br />

VIII. Legal Motions from O<strong>the</strong>r States<br />

Petitioner Brief – Sullivan v. Florida<br />

Petitioner Brief – Graham v. Florida<br />

Pennsylvania – Amici Brief<br />

Pennsylvania – Cover Sheet<br />

Alabama – Juvenile LWOP Brief<br />

Alabama – Sentencing Transcript<br />

Colorado – Flakes v. People<br />

Colorado – Apprendi Motion<br />

IX. State Statutes<br />

Memo of Law to Dismiss (Jack Cunha) – 2007<br />

Motion to Dismiss YO (Ken King) – 2007<br />

Memo to Dismiss (Ken King) – 2007<br />

Motion for Evidentiary Hearing (Ken King) –<br />

2007<br />

Motion to Dismiss (Patricia Downey) – 2005<br />

Colorado – Cert Petition<br />

Illinois – Motion Transfer Unconstitutional<br />

Illinois – Reply Brief<br />

Illinois – Appellant Brief<br />

New Mexico – Motion to Dismiss<br />

Washington, D.C. – Motion to Dismiss<br />

Washington, D.C. – Reply Letter<br />

Washington, D.C. – 2 nd Reply Letter<br />

Chart showing how and where juvenile life without parole is imposed across 50 states (National<br />

Conference of State Legislatures)<br />

Regularly updated state-by-state statistics on juvenile life without parole:<br />

http://www.law.usfca.edu/jlwop/resourceguide.html<br />

X. Helpful Websites<br />

Laurence Steinberg Publications (Website)<br />

http://www.temple.edu/psychology/lds/publications.htm<br />

Laurence Steinberg is a professor of Psychology at Temple University and a leading authority on<br />

psychological development during adolescence. Pdf versions of his publications are available on this site.<br />

Campaign for <strong>the</strong> Fair Sentencing of <strong>Youth</strong> (Website)<br />

http://www.endjlwop.org/<br />

The national campaign to end juvenile life without parole includes information about state sentencing<br />

practices and an extensive advocacy resource bank, including a section on adolescent brain research.

Most of <strong>the</strong> materials for Sullivan and Graham are available on <strong>the</strong> site, and <strong>the</strong> site is updated regularly<br />

with new resources.<br />

American Bar Association: Juvenile Justice Committee (Website)<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/<br />

The ABA’s Juvenile Justice website has a myriad of resources regarding adolescent brain development,<br />

and simple searches of brain development will yield current articles as well as information about <strong>the</strong><br />

Graham, Roper, and Atkins cases. The best way to navigate this site is by using <strong>the</strong> search function.<br />

PBS Frontline: Inside <strong>the</strong> Teenage <strong>Brain</strong> (Website/Program)<br />

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/teenbrain/<br />

This 2002 PBS Frontline specifically dealt with recent technology in <strong>the</strong> field of neuroimaging as it<br />

relates to adolescent brain development. The show gives an in-depth overview of <strong>the</strong> science and<br />

technology involved, includes interviews, and discusses some of <strong>the</strong> implications of <strong>the</strong> findings. Watch<br />

<strong>the</strong> entire show online, read <strong>the</strong> transcript, and read interviews w/ experts.<br />

MacArthur Foundation on <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Juvenile Justice (Website)<br />

http://www.adjj.org/content/index.php<br />

The MacArthur Foundation’s website has numerous documents, briefs, and PowerPoint presentations all<br />

discussing adolescent development (immaturity, cognitive abilities, risk-assessment, etc). The Foundation<br />

consists of some of <strong>the</strong> leading researches in <strong>the</strong> field of adolescent development as it relates to <strong>the</strong><br />

juvenile justice system.<br />

National Juvenile Justice Network (Website)<br />

http://njjn.org/<br />

The National Juvenile Justice Network website posts a wealth of resources, including its own research<br />

publications, legislative material, and publications on a variety of issues in juvenile justice.

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Quick Reference Experts List (DRAFT)<br />

BAIRD, ABIGAIL, Ph.D.<br />

Neuroscientist – Dartmouth College<br />

Phone: (603) 646-9022 Fax: Email: abigail.a.baird@dartmouth.edu<br />

Website: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~psych/people/faculty/a-baird.html<br />

Worked with Deborah Yurgelun-Todd (below) on <strong>the</strong> 1999 study involving teens’ identification of<br />

emotions. In subsequent experiments, Dr. Baird learned that teens’ correct recognition of emotional<br />

responses significantly improved when <strong>the</strong> faces were those of people <strong>the</strong>y knew, suggesting that<br />

adolescents are more prone to pay attention to things that are more closely related to <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

BJORK, JAMES, Ph.D.<br />

Researcher – National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.<br />

Phone:<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

Researcher at <strong>the</strong> National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism who used MRI technology to scan<br />

brains of 12 adolescents (aged 12-17) and 12 adults (aged 22-28) comparing <strong>the</strong>ir responses to simulated<br />

situations involving risks and rewards. The study found that youth tend to use lower activation of <strong>the</strong> part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> brain associated with motivating behavior toward <strong>the</strong> prospect of rewards. Dr. Bjork notes that <strong>the</strong><br />

study “may help to explain why so many young people have difficulty achieving long-term goals.”<br />

FASSLER, DAVID, M.D.<br />

Clinical Associate Professor – UVM Medical School, Psychiatry Dept.<br />

Phone: (802) 865-3450<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email: David.Fassler@uvm.edu<br />

<strong>Adolescent</strong> psychiatrist who testified on behalf of <strong>the</strong> American Psychiatric Association in Nevada in<br />

2003 and New Hampshire in 2004 to try and persuade <strong>the</strong> state legislatures to abolish <strong>the</strong> death penalty<br />

for juveniles. Both states abolished <strong>the</strong> practice after Dr. Fassler’s testimony, which used studies<br />

regarding <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> adolescent brain as part of <strong>the</strong> basis of his argument.<br />

GIEDD, JAY, M.D.<br />

Neuroscientist – National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)<br />

Phone: (301) 435-4517<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email: GieddJ@intra.nimh.nih.gov<br />

Has performed extensive research involving almost 2,000 kids and adolescents using MRI technology<br />

that demonstrates that adolescent brains are still developing and are different from fully-developed adult<br />

brains. Dr. Giedd has created records of each of <strong>the</strong> youth he has scanned, taking MRI every two years,<br />

showing <strong>the</strong> growth and development of <strong>the</strong> brain over <strong>the</strong> years. His research shows that especially in<br />

early adolescence, <strong>the</strong> brain is undergoing drastic changes.

GOLDBERG, ELKHONON Ph.D.<br />

Clinical Professor – NYU Medical School<br />

Phone: (212) 541 6412 Fax: (212) 765 7158 Email: eg@elkhonongoldberg.com<br />

Website: http://www.elkhonongoldberg.com/<br />

Authored The Executive <strong>Brain</strong>, Frontal Lobes and <strong>the</strong> Civilized Mind, (2001), which contends that <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal lobe is responsible for decision making, planning, cognition, judgment, and o<strong>the</strong>r behavior skills<br />

associated with criminal culpability. While Dr. Goldberg is not juvenile specific, his findings are<br />

extremely important when combined with work that proves that <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe is still undergoing<br />

significant changes during adolescence.<br />

GOGTAY, NITIN M.D.<br />

Psychiatrist - NIMH<br />

Phone: (301) 443-4513<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

Led a team that used MRI technology to study youth ages 4 to 21 to prove that <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe is one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> last areas of <strong>the</strong> brain to fully mature. The frontal lobe is thought to be <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain most<br />

closely associated to factors related to criminal culpability such as decision making, risk assessment, etc.<br />

GRISSO, THOMAS, Ph.D.<br />

Professor – UMASS Medical School, Psychiatry Dept.<br />

Phone: (508)-856-3625 Fax: (508)-856-6426 Email: Thomas.Grisso@umassmed.edu<br />

Website: http://www.umassmed.edu/cmhsr/faculty/Grisso.cfm<br />

Nationally known juvenile forensics expert and co-editor of <strong>Youth</strong> on Trial, (2000), which argues in part<br />

that <strong>the</strong> psychological development of adolescents affects <strong>the</strong>ir abilities to comprehend <strong>the</strong> juvenile<br />

justice process, and also makes <strong>the</strong>m less morally culpable. The book specifically takes on <strong>the</strong> issue of<br />

“Adult Time for Adult Crime.”<br />

GRUBER, STACI, Ph.D.<br />

Neuropsychologist – McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA<br />

Phone: (617)-855-3238<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

GUR, RUBEN, Ph.D.<br />

Neuropsychologist – University of Pennsylvania Hospital<br />

Phone: (215) 662-2915 Fax: Email: gur@bbl.med.upenn.edu<br />

Website: http://www.med.upenn.edu/ins/faculty/gur.htm<br />

Submitted declaration in Patterson v. Texas (2002), stressing that adolescents were less culpable than<br />

adults. Discusses how <strong>the</strong> parts of <strong>the</strong> brain most related to criminal culpability are also <strong>the</strong> latest parts to<br />

develop.

SCOTT, ELIZABETH, J.D.<br />

Professor – University of Virginia Law School<br />

Phone: (434) 924-3217 Fax: (804) 924-7536 Email: es@virginia.edu<br />

Website: http://www.law.virginia.edu/lawweb/faculty.nsf/FHPbI/5417<br />

Co-director and founder of <strong>the</strong> Center for Children, Families and Law and law professor at University of<br />

Virginia who specializes in juvenile and family law. Author of “Blaming <strong>Youth</strong>,” (2002), an essay which<br />

uses scientific research to demonstrate why juveniles are not as culpable from a legal perspective.<br />

SOWELL, ELIZABETH, Ph.D.<br />

Professor – UCLA Medical School, Neurology Dept.<br />

Phone: (310) 206-2101 Fax: Email: esowell@loni.ucla.edu<br />

Website: http://www.neurology.ucla.edu/faculty/SowellE.htm<br />

Led studies of brain development from adolescence to adulthood. Found that during adolescence, <strong>the</strong><br />

frontal lobe of <strong>the</strong> brain (<strong>the</strong> part that relates to <strong>the</strong> maturation of cognitive processing and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

‘executive functions), undergoes <strong>the</strong> most significant changes. The study found that <strong>the</strong> frontal lobe was<br />

<strong>the</strong> last part of <strong>the</strong> brain to fully develop, and thus while adolescent brains may be similar to adults, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

differ in <strong>the</strong>ir abilities to reason.<br />

TOGA, ARTHUR, Ph.D.<br />

Professor – UCLA Medical School, Neurology Dept.<br />

Phone: (310)206-2101 Fax: (310)206-5518 Email: toga@loni.ucla.edu<br />

Website: http://www.neurology.ucla.edu/faculty/TogaA.htm<br />

Neuroimaging specialist who worked with NIMH to render MRI scans into a 4-D time-lapse model<br />

demonstrating <strong>the</strong> evolution of a child’s brain into adulthood (<strong>the</strong> 4 th dimension is rate of change). The<br />

model demonstrates <strong>the</strong> growth and movement of different brain matter as children grow into adults.<br />

YURGELUN-TODD, DEBORAH Ph.D.<br />

Neuropsychologist – McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA<br />

Phone: (617)-855-3238<br />

Website:<br />

Fax: Email:<br />

Performed a study comparing what parts of <strong>the</strong> brain adolescents and adults use when responding to<br />

emotions. The study concluded that adolescents tend to rely on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain responsible for “gut<br />

reactions,” in contrast to adults who more often use <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain responsible for more rational (not<br />

based on emotional responses) decisions.

Limbic System<br />

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Understanding <strong>the</strong> Parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong><br />

Amygdala<br />

The Adult <strong>Brain</strong><br />

The Frontal Lobe, often called <strong>the</strong> “command center” of <strong>the</strong> brain, is <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> brain<br />

that controls <strong>the</strong> decision making process for adults, including long-term planning, riskassessment,<br />

impulse control, and o<strong>the</strong>r behaviors associated with criminal culpability. It is<br />

also one of <strong>the</strong> last parts of <strong>the</strong> brain to fully mature (in <strong>the</strong> early 20s). 1 This late maturation<br />

process suggests that adolescents are not as capable as adults of weighing long-term<br />

consequences, and evaluating risk-assessment.<br />

The Prefrontal Cortex is responsible for cognitive processing, problem solving, and<br />

emotional control in adults. There is a stark contrast in brain maturation (Myelination)<br />

between youth aged 12-16 and young adults (23-30), especially in <strong>the</strong> Frontal Lobe and<br />

Prefrontal Cortex. 2 This difference suggests that adults are more capable of controlling <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

emotions and making more rational decisions than adolescents.<br />

The <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong><br />

The Limbic System regulates hormonal processing, which is overly active in adolescents, 3<br />

and also is responsible for handling emotional reactions. <strong>Adolescent</strong>s tend to use <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

Limbic System more often in <strong>the</strong> decision making process, since <strong>the</strong>ir Frontal Lobes are<br />

not fully developed, which results in adolescents making more decisions based on<br />

emotional reactions ra<strong>the</strong>r than reasoning, weighing of long term consequences, or<br />

planning. 4<br />

The Amygdala, part of <strong>the</strong> Limbic System, is responsible for impulse reactions, emotional<br />

reactions, fear, and is also used in <strong>the</strong> decision-making process of adolescents.<br />

Developing adolescents tend to use <strong>the</strong>ir Amygdala when responding to o<strong>the</strong>r people’s<br />

emotions, yielding more reactionary, less reasoned perceptions of situations than adults. 5<br />

Juvenile Defense Network ~ Lawyers Helping Lawyers Helping Kids

Footnotes:<br />

_______________________________________________________________________<br />

1. Fagan, Jeffrey. “Adoescents, Maturity, and <strong>the</strong> Law.” The American Prospect. August, 2005.<br />

2. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Teenage <strong>Brain</strong>: A Work in Progress. 2001.<br />

3. <strong>Adolescent</strong>s going through puberty experience increased hormone levels. For example, <strong>the</strong> production of testosterone, a<br />

hormone closely associated with aggression, increases approximately tenfold in boys. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse<br />

and Alcoholism (NIAAA). <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation. 2004.<br />

4. McNamee, Rebecca. An Overview of <strong>the</strong> Science of <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong>. Presented at <strong>the</strong> Coalition for<br />

Juvenile Justice Annual Conference. 2006.<br />

5. NIMH. Id.<br />

Images Adapted From:<br />

_______________________________________________________________________<br />

1. PBS: The Secret Life of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/brain/<br />

2. Amygdala/Limbic System: http://www.memorylossonline.com/glossary/amygdala.html<br />

Online Resources:<br />

_______________________________________________________________________<br />

1. ABA: Adolescence, <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong> and Legal Culpability<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/Adolescence.pdf<br />

2. American Psychologist: Less Guilty by Reasons of Adolescence<br />

http://ccjr.policy.net/cjedfund/resourcekit/Psychology_Less_Guilty.pdf<br />

3. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong>s Show Reduced Reward Anticipation.<br />

http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/feb2004/niaaa-25.htm<br />

4. National Institute of Mental Health: Imaging Study Shows <strong>Brain</strong> Maturing.<br />

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/press/prbrainmaturing.cfm<br />

5. PBS Frontline: Inside <strong>the</strong> Teenage <strong>Brain</strong><br />

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/teenbrain/<br />

6. Roper v. Simmons: Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Bar Association, et al.<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/simmons/aba.pdf<br />

7. Roper v. Simmons: Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Medical Association, et al.<br />

http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/simmons/ama.pdf<br />

8. Roper v. Simmons: Amici Curiae Brief of <strong>the</strong> American Psychological Association, et al.<br />

http://www.apa.org/psyclaw/roper-v-simmons.pdf<br />

9. Science Magazine: Crime, Culpability, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong><br />

http://www.wpic.pitt.edu/research/lncd/papers/ScienceLunaOct2004.pdf<br />

10. Science News: Teen <strong>Brain</strong>s on Trial.<br />

http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20040508/bob9.asp<br />

11. Juvenile Defense Network: Roper v. Simmons and ways to incorporate it into your practice.<br />

http://www.youthadvocacyproject.org/pdfs/Roper%20fact%20sheet.pdf<br />

This project is supported by Grant # 2005 JF-FX 0055 awarded by <strong>the</strong> Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U.S.<br />

Department of Justice to <strong>the</strong> Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety Programs <strong>Division</strong> and subgranted to <strong>the</strong> Committee for Public Counsel Services.<br />

Points of view in this document are those of <strong>the</strong> author(s) and do not necessarily represent <strong>the</strong> official position or policies of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Department of Justice or <strong>the</strong><br />

Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety Programs <strong>Division</strong>.<br />

Juvenile Defense Network<br />

<strong>Youth</strong> <strong>Advocacy</strong> Project/CPCS<br />

Ten Malcolm X Blvd.<br />

Roxbury, MA 02119<br />

Tel: (617) 445-5640<br />

http://www.youthadvocacyproject.org/jdn.htm

<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Brain</strong> <strong>Development</strong><br />

Implications in <strong>the</strong> Courtroom<br />

Adolescence has long been known as a time of significant psychosocial development. Recent advances in<br />

fMRI (functional MRI) technology have been critical in understanding adolescence as a crucial period of brain<br />