The Case of a Science Journalism Writing Project - National Council ...

The Case of a Science Journalism Writing Project - National Council ...

The Case of a Science Journalism Writing Project - National Council ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

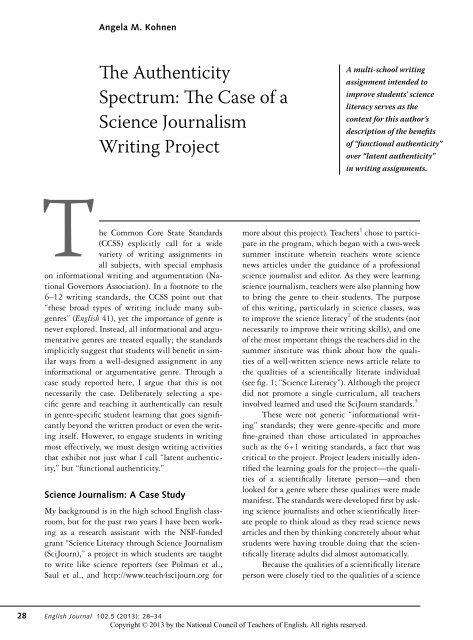

Angela M. Kohnen<strong>The</strong> AuthenticitySpectrum: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>of</strong> a<strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong><strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Project</strong>A multi-school writingassignment intended toimprove students’ scienceliteracy serves as thecontext for this author’sdescription <strong>of</strong> the benefits<strong>of</strong> “functional authenticity”over “latent authenticity”in writing assignments.<strong>The</strong> Common Core State Standards(CCSS) explicitly call for a widevariety <strong>of</strong> writing assignments inall subjects, with special emphasison informational writing and argumentation (<strong>National</strong>Governors Association). In a footnote to the6–12 writing standards, the CCSS point out that“these broad types <strong>of</strong> writing include many subgenres”(En glish 41), yet the importance <strong>of</strong> genre isnever explored. Instead, all informational and argumentativegenres are treated equally; the standardsimplicitly suggest that students will benefit in similarways from a well-designed assignment in anyinformational or argumentative genre. Through acase study reported here, I argue that this is notnecessarily the case. Deliberately selecting a specificgenre and teaching it authentically can resultin genre-specific student learning that goes significantlybeyond the written product or even the writingitself. However, to engage students in writingmost effectively, we must design writing activitiesthat exhibit not just what I call “latent authenticity,”but “functional authenticity.”<strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong>: A <strong>Case</strong> StudyMy background is in the high school En glish classroom,but for the past two years I have been workingas a research assistant with the NSF-fundedgrant “<strong>Science</strong> Literacy through <strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong>(SciJourn),” a project in which students are taughtto write like science reporters (see Polman et al.,Saul et al., and http://www.teach4scijourn.org formore about this project). Teachers 1 chose to participatein the program, which began with a two-weeksummer institute wherein teachers wrote sciencenews articles under the guidance <strong>of</strong> a pr<strong>of</strong>essionalscience journalist and editor. As they were learningscience journalism, teachers were also planning howto bring the genre to their students. <strong>The</strong> purpose<strong>of</strong> this writing, particularly in science classes, wasto improve the science literacy 2 <strong>of</strong> the students (notnecessarily to improve their writing skills), and one<strong>of</strong> the most important things the teachers did in thesummer institute was think about how the qualities<strong>of</strong> a well-written science news article relate tothe qualities <strong>of</strong> a scientifically literate individual(see fig. 1; “<strong>Science</strong> Literacy”). Although the projectdid not promote a single curriculum, all teachersinvolved learned and used the SciJourn standards. 3<strong>The</strong>se were not generic “informational writing”standards; they were genre-specific and morefine-grained than those articulated in approachessuch as the 6+1 writing standards, a fact that wascritical to the project. <strong>Project</strong> leaders initially identifiedthe learning goals for the project—the qualities<strong>of</strong> a scientifically literate person—and thenlooked for a genre where these qualities were mademanifest. <strong>The</strong> standards were developed first by askingscience journalists and other scientifically literatepeople to think aloud as they read science newsarticles and then by thinking concretely about whatstudents were having trouble doing that the scientificallyliterate adults did almost automatically.Because the qualities <strong>of</strong> a scientifically literateperson were closely tied to the qualities <strong>of</strong> a science28 En glish Journal 102.5 (2013): 28–34

Angela M. KohnenFigure 1. Qualities <strong>of</strong> a Scientifically Literate Person Compared to Qualities <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Science</strong> News ArticleA scientifically literate person is able to . . . A high-quality science news article . . .. . . identify personal and civic concerns that benefitfrom scientific and technological understanding.. . . effectively search for and recognize relevant, credibleinformation.. . . digest, present, and properly attribute informationfrom multiple, credible sources.. . . contextualize technologies and discoveries, differentiatingbetween those that are widely accepted andemergent; attending to the nature, limits, and risks <strong>of</strong> adiscovery; and integrating information into broader policyand lifestyle choices.. . . has most or all <strong>of</strong> the following elements: is local, narrow,timely, and presents a unique angle.. . . uses information from relevant, credible sourcesincluding the Internet and interviews.. . . is based on multiple, credible, attributed sources froma variety <strong>of</strong> stakeholders.. . . contextualizes information by telling why it is importantas well as which ideas are accepted and which arepreliminary.. . . fact check both big ideas and scientific details. . . . is factually accurate and foregrounds importantinformation.news article, assigning writing using the SciJournstandards was not “a stretch” for the teachers seekingto meet other complementary learning goals.Teachers involved in the project could respondto student writing by attending to this subset <strong>of</strong>pr<strong>of</strong>essional standards, something that made thiswriting different from what had gone on in theseclassrooms before where writing assignments wereschool-specific and formulaic and for which teachers<strong>of</strong>ten responded using a generic rubric (e.g., labreports or research papers).Classroom Implementation StrategiesAlthough the project looked different in each classroom,many teachers followed a similar pattern<strong>of</strong> implementation. <strong>Science</strong> journalism was introducedto the students, <strong>of</strong>ten at the beginning <strong>of</strong>the semester, through a 5–10 minute Read-Aloud/Think-Aloud (RATA) 4 protocol:• the teacher finds an interesting science newsstory and projects it on the overhead for theclass to see;• the teacher reads the article, stopping tothink aloud at various intervals;• students are invited to comment or askquestions.In addition to comments about the subjectmatter <strong>of</strong> the article, teachers also ask questions inspiredby the SciJourn standards (see http://www.teach4scijourn.org for further instructions andideas for using a RATA with science news articles).Many science teachers conducted RATAs for severalmonths before even introducing the studentwriting assignment, gradually adding more kinds<strong>of</strong> questions. En glish teachers <strong>of</strong>ten incorporatedscience journalism as a single unit in their courseand only did science news RATAs during that unit.RATAs established a foundation for student writingeven though most <strong>of</strong> the teacher’s questions andcomments had nothing to do with writing. Instead,the teachers were slowly uncovering the essentialand relevant qualities <strong>of</strong> the genre for the students.By listening to RATAs, students began to see thatreaders (and writers) <strong>of</strong> science news are skeptical,that they value corroborating information, and thatthey demand that science information be madeclear, timely, and engaging.Not all SciJourn science teachers asked theirstudents to write science news articles, 5 but forthose who did, at this point students moved fromlistening to science news to “becoming” sciencejournalists. By beginning with topic selection,like pr<strong>of</strong>essional science journalists, students realizedthat a scientifically literate person is someonewho sees unusual, entertaining, or important sciencestories all around. Likewise, a scientifically literateperson is someone who recognizes that manyconsumer, personal, political, or social issues havea scientific component. Students, many <strong>of</strong> whompreviously claimed to find science “boring,” becameEnglish Journal29

<strong>The</strong> Authenticity Spectrum: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Project</strong>excited about the prospect <strong>of</strong> learning more abouttheir favorite sports or hobbies. More seriously,some students chose to report about health topicsthat affected themselves or a loved one; some<strong>of</strong> these topics had never been discussed openlyin the family before. As they brainstormed topics,student-journalists had to carefully consider theiraudience, 6 as well as the size and scope <strong>of</strong> the assignment(generally around 500 words).Once students began gathering information,they had to work on two important skills: performingInternet research and conducting an interview.Much has been written about students’ Internetresearch skills (e.g., Ostenson), but <strong>of</strong>ten theseapproaches are limited to encouraging studentsto conduct academic research and do not provideadequate context for suggested assignments. <strong>The</strong>Students, many <strong>of</strong> whompreviously claimed to findscience “boring,” becameexcited about the prospect<strong>of</strong> learning more abouttheir favorite sports orhobbies. More seriously,some students chose toreport about health topicsthat affected themselvesor a loved one.resulting advice usually includesa list <strong>of</strong> dos and don’ts(don’t go to Wikipedia; dogo to .govs and .edus) anda generic set <strong>of</strong> guidelinesfor evaluating websites. Butwhen students are acting asscience journalists, Internetsearching becomes different.Students who don’t knowmuch about their topic areencouraged to go to Wikipedia,not as a source to quotein the final story but as a placeto gather background information on the topic, tolearn more technical terms for use in a search engine,and to find additional, more credible, sources(usually linked at the bottom <strong>of</strong> the article). Many.coms are perfectly acceptable for science journalism:if a story is about a new technology, thecompany’s website will have to be consulted, andpeer-reviewed articles on WebMD are a crediblesource <strong>of</strong> health information. On the other hand, astory that only includes .gov sources is not givinga complete picture, nor is a story that only citesthe educational institution where research tookplace (even though that institution is probably an.edu). By acting like a science journalist, a studentis taught to think about each source in the context<strong>of</strong> the whole article—for example, a blogger withbreast cancer may add to a story about reactions toa new treatment, although an article would neveronly include blogs as sources. This kind <strong>of</strong> thinkingis much more like what we as educated adults dowhen we search online: we don’t avoid all .comsnor do we pull out an old worksheet from the library.But students are rarely asked to practice thistype <strong>of</strong> searching and thinking in schools.Classroom assignments also rarely requirestudents to interview adults, but learning to askquestions and listen carefully to answers is an essentialpart <strong>of</strong> being a science journalist (and <strong>of</strong>being an educated adult, particularly in the doctor’s<strong>of</strong>fice). Many SciJourn teachers required thattheir students interview an adult; students learnedto compose appropriate questions and to locate experts,which sometimes was as simple as walkingdown the school’s hallways (interview sources includedcoaches, other teachers, the student’s doctor,family friends, as well as experts found online).Putting all this information into a sciencenews article was a challenge. In a range <strong>of</strong> settings,from low-performing schools with high povertyto affluent, private schools, classroom teachers raninto similar problems: students struggled to letgo <strong>of</strong> the five-paragraph essay formula; studentsfailed to include appropriate attribution to theirsources within the article; students “buried thelede” by holding the personal connection or angleto the end <strong>of</strong> the article; and students struggledto determine how much contextual informationto include. For science teachers, addressing thesewriting issues was <strong>of</strong>ten new territory, but becausethey had been taught to focus on the SciJourn standardsin their teaching and feedback, many wereable to prioritize their responses. Teachers learnedto consider missing attributions a major problemand many made “attribution to multiple, crediblesources” the most important aspect <strong>of</strong> the assignment.In a number <strong>of</strong> science classes, studentscould earn passing grades even if they failed tobreak out <strong>of</strong> the five-paragraph essay formula, aslong as the SciJourn standards were met. In general,students wrote at least two drafts, with someteachers requiring or encouraging many more.Teachers also involved the project’s science editorin varying ways, with one teacher sending nearlyevery student article to the editor for feedback andothers sending none.30 May 2013

Angela M. KohnenJack Hollingsworth/ThinkstockStudent Reactions<strong>The</strong> SciJourn science teachers said that the sciencejournalism project was one <strong>of</strong> the few writing assignmentsthat made sense in their classes: thegenre-specific priorities and values articulated inthe SciJourn standards resonated with their owngoals (Kohnen). SciJourn students were also affectedby their experience playing the role <strong>of</strong> sciencejournalist as we heard in our observational andinterview data. 7Brittany, for instance, was a senior in an Environmental<strong>Science</strong> class who saw the sciencejournalism assignment as markedly different fromher other science work—for the first time, she waslearning something she wanted to learn, not memorizingsomething from a textbook. But it wasn’tjust the choice <strong>of</strong> topic that Brittany found important;she also sounded like a tough reporter whenshe described how she managed to get an interviewwith a doctor after repeatedly being ignored: “Youneed to get mean sometimes, you know?” Like agood journalist, Brittany didn’t give up when severaldoctors’ <strong>of</strong>fices failed to answer her questionsand she finally found someone who would explain amedical condition to her.For Kim, a student in a journalism coursewho had never written about science before, credibilitytook on a new meaning. Her previous articleshad been mostly about “stuff happening aroundschool” so credible sources weren’t hard to find;however, for an article on a science topic, the issue<strong>of</strong> credibility was more challenging. She explainedthat websites need to be scrutinized carefully forexpertise and that all information needs to be corroboratedby several sources “’cause you don’t wantsome just some random stuff thrown in your articleand then find out it’s not real.” An aspiring journalist,Kim seemed very worried about the publication’s(and reporter’s) reputation. In terms <strong>of</strong> careergoals, Kim couldn’t have been more different fromher classmate Trevor, who did not see himself writingmuch at all after high school, and yet the twospoke in similar terms about credibility. Trevor toldme, “If you’re looking for something that mattersmake sure you go find out who’s actually a crediblesource. You don’t want to just go to some randomwebsite and try to find good information, becauseit could be false.” For Trevor, an avid weightlifter,the “something that matter[ed]” to him was informationon steroids. <strong>The</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> playing therole <strong>of</strong> a science journalist seems to have helpedhim think about online searching in a nuanced way;some searches “matter” in ways that others don’t.Erika and Heather, whose articles were publishedin SciJourner (http://www.scijourner.org), seemedto see themselves as “translators” <strong>of</strong> science information,a key component <strong>of</strong> the way pr<strong>of</strong>essionalscience journalists talk about their work (Blum,Knudson, and Henig; Dukes). Erika described herselfas needing “to understand the material to makeit possible for other people who maybe have not hadas much science experience or science education tounderstand it too,” while Heather said, “I need toexplain it to other people so they can know about,as much about the topic too.”Why did the project have such an impact? Inthe beginning, we thought it had to do with the“authentic” experience <strong>of</strong> writing in an “authentic”genre for an “authentic” audience; however,the concept <strong>of</strong> authenticity is more complicated.English Journal31

Angela M. Kohnenhas latent authenticity it may be fine for studentengagement or other teacher purposes, but it doesnot represent “real world writing,” defined in aprevious issue <strong>of</strong> this journal as writing for a specificaudience and for a particular purpose (Lindblom,“Editor”; Wiggins). But “real world writing”includes a great many genres; what the notion <strong>of</strong>functional authenticity also forces us to consider isthe differences between these genres—both in ourinstruction and in our assessment. Really teachinggenres, and determining how to assess them, requiresthat we think about more than just what thegenre looks like on the page (or screen), but alsowhat the genre requires <strong>of</strong> the writer. In a thoughtprovokingarticle, Charles Bazerman <strong>of</strong>fers a “view<strong>of</strong> how genre might interact with both learningand development, using a Vygotskian lens, consideringgenres as tools <strong>of</strong> cognition” (283). Basedon Vygotsky’s position that learning precedes development,Bazerman argues that new genres arefirst learned—<strong>of</strong>ten with difficulty—and only later,with repeated use, do the genres transform a person’sway <strong>of</strong> thinking and seeing the world: “wethen learn not just to talk but to learn the forms <strong>of</strong>attention and reasoning which the language pointsus toward. <strong>The</strong> words <strong>of</strong> the field become associatedwith practices and perceptions, changing our systems<strong>of</strong> operating within the world” (290).Bazerman’s examples are drawn primarilyfrom the college level, but the ideas are intriguingfor high school teachers. By choosing certaingenres, and using them in a functionally authenticway in the classroom, we can move our studentstoward different “forms <strong>of</strong> attention and reasoning.”<strong>Writing</strong> as science journalists demanded thatBrittany, Trevor, and Kim think in certain waysabout gathering information; Erika and Heatherthought more carefully about audience and clarity.Had their teachers used a different genre in afunctionally authentic way—blogging for youngerstudents, for example, or writing letters to actuallysend to specific individuals—the students wouldhave undoubtedly emphasized different characteristics<strong>of</strong> the writing, ones that may not have alignedas well with their teachers’ classroom goals. Whenfunctional authenticity is taken into account, differentgenres—and their associated “forms <strong>of</strong> attentionand reasoning”—make sense for differentpurposes and in different disciplines.Implications for Other Work<strong>The</strong> SciJourn case, although described extensively, ismeant only to serve as an example <strong>of</strong> what can happenwhen we consider functional authenticity in ourassignments and our teaching. All teachers, whetheror not they are part <strong>of</strong> a defined project or learningcommunity, can start thinking about the role<strong>of</strong> various “real world” writing assignments in theirclasses. Designing writing assignments with functionalauthenticity in mind can make our classroomsinto places where students experience the differentroles different genres invite them to play. But forthis to happen we must first come to know the genreand its values ourselves; determine standards or valuesthat are authentic to the genre and our learninggoals; and, finally, assess student learning accordingto those standards and values. <strong>The</strong> CCSS may requirethat we assign more informational writing andargumentation, but not all genres are created equal.<strong>The</strong> CCSS assert that “students must take task, purpose,and audience into careful consideration” (English41). By considering functional authenticity we,as writing teachers, can do the same.Notes1. <strong>The</strong> grant ran for three summers; 45 classroomteachers participated. Most (35) were high school scienceteachers; 4 were high school ELA/journalism teachers; theremaining teachers taught agriculture, psychology, andmiddle school science. Teachers came from 28 differentschools, representing a diverse range <strong>of</strong> contexts.2. <strong>The</strong> definition <strong>of</strong> science literacy is a contestedone (see Roberts for a discussion <strong>of</strong> the issue); SciJourndefined “science literacy” as the skills students will need todeal with the science-related issues they are likely to face 15years after high school graduation.3. <strong>The</strong> SciJourn standards were developed over aperiod <strong>of</strong> years using an iterative process. <strong>The</strong> original version,developed in conversation with Alan Newman, LauraPearce, Wendy Saul, Nancy Singer, and Eric Turley, was first<strong>of</strong>fered in 2010. An elaborated description <strong>of</strong> the currentstandards can be found at http://www.teach4scijourn.org.4. <strong>The</strong> CCSS warn that “reading aloud to students inthe upper grades should not, however, be used as a substitutefor independent reading by students; read-alouds atthis level should supplement and enrich what students areable to read by themselves” (<strong>National</strong> Governors Association,“Appendix A” 27). However, our work finds that eventhe most accomplished students, capable <strong>of</strong> comprehendingthe content <strong>of</strong> science news articles independently, benefitfrom RATAs in terms <strong>of</strong> engagement, content knowledge,and enhanced understanding <strong>of</strong> the genre.5. In the second and third years <strong>of</strong> the project, a portion<strong>of</strong> each teacher’s stipend was dependent on requiringstudents to write an article.English Journal33

<strong>The</strong> Authenticity Spectrum: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Project</strong>6. Teachers had the opportunity to submit their students’writing to the grant’s science editor for possible publicationin SciJourner, although not all teachers chose to doso. <strong>The</strong> editor accepted approximately 10% <strong>of</strong> submissions,none without revision. Yet even teachers who did not submitwork to the editor asked their students to write for ateenage audience.7. All research described in this article was conductedunder approval <strong>of</strong> the sponsoring university’s InternalReview Board. Student names are pseudonyms.8. Genre and education has been the subject <strong>of</strong> muchresearch over the past several decades. See Bawarshi andReiff; Dean; Fleischer and Andrew-Vaughan; Lattimer; andRomano for texts that have influenced this article.Works CitedBawarshi, Anis S., and Mary Jo Reiff. Genre: An Introductionto History, <strong>The</strong>ory, Research, and Pedagogy. ReferenceGuides to Rhetoric and Composition. Ed. CharlesBazerman. Fort Collins: WAC Clearinghouse, 2010.Print.Bazerman, Charles. “Genre and Cognitive Development:Beyond <strong>Writing</strong> to Learn.” Genre in a ChangingWorld. Ed. Charles Bazerman, Adair Bonini, andDébora Fifueiredo. Fort Collins: WAC Clearinghouse,2009. Print.Blum, Deborah, Mary Knudson, and Robin Marantz Henig,eds. A Field Guide for <strong>Science</strong> Writers: <strong>The</strong> Official Guide<strong>of</strong> the <strong>National</strong> Association <strong>of</strong> <strong>Science</strong> Writers. 2nd ed.New York: Oxford UP, 2006. Print.Dean, Deborah. Genre <strong>The</strong>ory: Teaching, <strong>Writing</strong>, and Being.Urbana: NCTE, 2008. Print.Dukes, Tyler. “<strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong>: A Job for Translators.”Communication: <strong>Journalism</strong> and Education Today (Summer2008): 16–21. Print.Fleischer, Cathy, and Sarah Andrew-Vaughan. <strong>Writing</strong> OutsideYour Comfort Zone: Helping Students Navigate UnfamiliarGenres. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2009. Print.Kixmiller, Lori A. “Standards without Sacrifice: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Case</strong>for Authentic <strong>Writing</strong>.” En glish Journal 94.1 (2004):29–33. Print.Kohnen, Angela M. “A New Look at Genre and Authenticity:Making Sense <strong>of</strong> Reading and <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Science</strong>News in High School Classrooms.” Diss. University<strong>of</strong> Missouri–St. Louis, 2012. Print.Lattimer, Heather. Thinking through Genre: Units <strong>of</strong> Study inReading and <strong>Writing</strong> Workshop 4–12. Portland: Stenhouse,2003. Print.Lindblom, Ken. “From the Editor.” En glish Journal 98.5(2009): 13–14. Print.Lindblom, Kenneth. “Teaching En glish in the World:<strong>Writing</strong> for Real.” En glish Journal 94.1 (2004):104–08. Print.<strong>National</strong> Governors Association Center for Best Practices,<strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chief State School Officers. “Appendix A:Research Supporting Key Elements <strong>of</strong> the Standards,Glossary <strong>of</strong> Key Terms.” Common Core State Standardsfor En glish Language Arts & Literacy in History/SocialStudies, <strong>Science</strong>, and Technical Subjects. Washington:<strong>National</strong> Governors Association Center for BestPractices, <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chief State School Officers,2010. Web. 2 Feb. 2013. .———. Common Core State Standards for En glish LanguageArts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, <strong>Science</strong>, andTechnical Subjects. Washington: <strong>National</strong> GovernorsAssociation Center for Best Practices, <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong>Chief State School Officers, 2010. Web. 2 Feb. 2013..Ostenson, Jonathan. “Skeptics on the Internet: TeachingStudents to Read Critically.” En glish Journal 98.5(2009): 54–59. Print.Parsons, Seth A., and Allison E. Ward. “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Case</strong> forAuthentic Tasks in Content Literacy.” <strong>The</strong> ReadingTeacher 64.6 (2011): 462–65. Print.Polman, Joseph L., et al. “<strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong>: StudentsLearn Lifelong <strong>Science</strong> Literacy Skills by Reportingthe News.” <strong>The</strong> <strong>Science</strong> Teacher (January 2012): 44–47.Print.Roberts, Douglas A. “Scientific Literacy/<strong>Science</strong> Literacy.”Handbook <strong>of</strong> Research on <strong>Science</strong> Education. Ed. SandraK. Abell and Norman G. Lederman. Mahwah: Erlbaum,2007. 729–80. Print.Romano, Tom. Blending Genre, Altering Style: <strong>Writing</strong> MultigenrePapers. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2000. Print.Saul, Wendy, et al. Front Page <strong>Science</strong>: Engaging Teens in <strong>Science</strong>Literacy. Arlington: <strong>National</strong> <strong>Science</strong> TeachersAssn., 2012. Print.“<strong>Science</strong> Literacy through <strong>Science</strong> <strong>Journalism</strong>.” Teach4Sci-Journ. Web 2 Feb. 2013. .Whitney, Anne Elrod. “In Search <strong>of</strong> the Authentic En glishClassroom: Facing the Schoolishness <strong>of</strong> School.”En glish Education 44.1 (2011): 51–62. Print.Wiggins, Grant. “Real-World <strong>Writing</strong>: Making Purposeand Audience Matter.” En glish Journal 98.5 (2009):29–37. Print.Angela Kohnen taught secondary En glish for five years. Currently, she is assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor in the En glish department at MissouriState University and co-director <strong>of</strong> the Ozarks <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Project</strong>. Email her at Akohnen@missouristate.edu.READWRITETHINK CONNECTIONLisa Storm Fink, RWTInterviewing family members or friends can be a valuable way for teens and preteens to learn about themselves andtheir families. <strong>The</strong>se interviews need not be formal, but a little time spent in preparation will result in a more positive,productive experience for everyone involved as described in this Tip and How To from ReadWriteThink.org.http://www.readwritethink.org/parent-afterschool-resources/tips-howtos/helping-teen-plan-conduct-30113.html34 May 2013