Interim Stabilization Balancing Security and Development in Post ...

Interim Stabilization Balancing Security and Development in Post ...

Interim Stabilization Balancing Security and Development in Post ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

AcknowledgementsThis study on <strong>Interim</strong> Stabilisation was commissioned by the Folke BernadotteAcademy, f<strong>in</strong>anced by the M<strong>in</strong>istry for Foreign Affairs of Sweden <strong>and</strong> undertakenby Nat J. Colletta, Hannes Berts <strong>and</strong> Jens Samuelsson Schjörlien of the Sthlm(Stockholm) Policy Group. The authors take sole responsibility for the analysis,f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> recommendations there<strong>in</strong>. The report does not necessarily representthe views of the FBA or the MFA as such.A special thank you is directed to the partners that prepared country casestudies as well as contributed to the conclud<strong>in</strong>g discussions on f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong>recommendations: Colombia, Alex<strong>and</strong>ra Guáqueta <strong>and</strong> Gerson Arias of theFundación Ideas para la Paz (www.ideaspaz.org); Cambodia, S<strong>in</strong>thay Neb <strong>and</strong>Sven Edquist of the Advocacy Policy Institute (www.api<strong>in</strong>stitute.org); <strong>and</strong>Ug<strong>and</strong>a, Justice Peter Onega <strong>and</strong> Fred Mugisha of the Amnesty Commission(www.amnestycom.go.ug). For the review of literature <strong>and</strong> relevant cases, thefollow<strong>in</strong>g persons have provided assistance: Calder Yates <strong>and</strong> Paolo Mastrangelo ofthe New College <strong>in</strong> Sarasota, Florida; Francis Musoni of the Rw<strong>and</strong>a Commissionfor Re<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> their personal capacity; Rebecka Lundgren, JohanRutgersson, Fiona Rotberg <strong>and</strong> Anna Valve.The luxury of hav<strong>in</strong>g access to a competent <strong>and</strong> experienced network ofpractitio ners <strong>and</strong> academics with<strong>in</strong> the Stockholm Initiative of DDR has provento be an <strong>in</strong>valuable asset when discuss<strong>in</strong>g, writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> modify<strong>in</strong>g results <strong>and</strong>recommendations: Pablo de Greiff, International Center for Transitional Justice;Nita Yawanarajah, UN DPA; Kelv<strong>in</strong> Ong, UN DPKO; Sofie da Camara <strong>and</strong>Cornelis Steenken, UNDP BCRP; Hans Thorgren, Swedish National DefenceCollege; Inger Buxton, EU Commission <strong>and</strong> researcher Pierre-Anto<strong>in</strong>e Braud.The Chairs of the two additional SIDDR work<strong>in</strong>g groups, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia Gamba <strong>and</strong>Ambassador Jan Cedergren, deserves special mention for their ideas <strong>and</strong> guidance.The Folke Bernadotte Academy, which is a Swedish Governmental organizationwith a m<strong>and</strong>ate on tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> method development on <strong>in</strong>ternational conflict<strong>and</strong> crisis management, has served as a platform on which to present the ideas<strong>and</strong> recommendations of the study. The authors would like to recognize theconstructive collaboration with the Academy. In particular for the purpose of thisstudy: its conflict prevention unit, led by Ambassador Ragnar Ängeby <strong>and</strong> its SSRunit,led by Michaela Friberg-Storey. The Director General, Henrik L<strong>and</strong>erholm,<strong>and</strong> deputy Director General, Jonas Alberoth, have been <strong>in</strong>strumental, not onlyfor the realization of this project, but also for general Swedish efforts seek<strong>in</strong>g tomobilize the capacity of the <strong>in</strong>ternational community to collectively support peace<strong>and</strong> security.Lastly, we would be remiss if we did not especially acknowledge Ambassador

Lena Sundh at the MFA. Without her pioneer<strong>in</strong>g leadership <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g the<strong>in</strong>ternational knowledge base <strong>and</strong> experiences with<strong>in</strong> the field of peace, security<strong>and</strong> development this study would have never come to fruition. As Chairwomanof the Stockholm Initiative on DDR, she performed a balanced role as facilitatorof discussions, <strong>and</strong> at times moderator of contentious debates. We owe her ourthanks <strong>and</strong> admiration.Nat J. Colletta, Jens Samuelsson Schjørlien <strong>and</strong> Hannes BertsSthlm Policy GroupStockholm <strong>and</strong> Sarasota, December 2008

Table of ContentsAcronyms ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4.Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 111. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 13The Stockholm Initiative on Disarmament Demobilization Re<strong>in</strong>tegration ........................ 14Generative Dialogues <strong>in</strong> Promot<strong>in</strong>g Peace Processes ........................................................................................................... 16Rationale for a Study of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> (or “Hold<strong>in</strong>g Patterns”) ......................................... 162. Sett<strong>in</strong>g the Stage: Challenges <strong>in</strong> Early Transition <strong>and</strong> Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g .......................................... 19Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the Key Contextual Factors .................................................................................................................................................. 19<strong>Balanc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Security</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Development</strong> – Stability <strong>and</strong> Change ............................................................................ 20L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g SSR <strong>and</strong> DDR <strong>in</strong> <strong>Post</strong> Conflict Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g ............................................................................................................. 223. Conceptualiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> ....................................................................................................................................................................... 23Clarify<strong>in</strong>g the Term<strong>in</strong>ology ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 23Creat<strong>in</strong>g Space <strong>and</strong> Buy<strong>in</strong>g Time for Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g ..................................................................................................................... 24Strengthen<strong>in</strong>g Prospects for Durable Peace ................................................................................................................................................ 254. Study Objectives <strong>and</strong> Methodology ............................................................................................................................................................................... 27<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> as a Strategic Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Measure ....................................................................................... 27The Methodology: From Desk Review to Fieldwork .............................................................................................................. 275. Review of Select <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> Approaches ............................................................................................................... 29Civil Service Corps ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 30South African Service Corps ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 30The Kosovo Protection Corps .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 33Military Integration ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 36

The DRC Brassage Process .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 36Angolan Ownership of the Military Integration Process ............................................................................40Nepal – Explor<strong>in</strong>g Opportunities for <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> ............................................................................ 43Transitional <strong>Security</strong> Forces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 45The Transitional Afghan Militia Forces – a Necessary Initial Step ................................................... 45The Sunni Awaken<strong>in</strong>g ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 48Transitional Autonomy ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 49The Peshmerga <strong>in</strong> Kurdish Iraq – Autonomy <strong>in</strong> the Mak<strong>in</strong>g .......................................................................... 49Dialogue <strong>and</strong> Sensitization (Halfway-House arrangements) .............................................................................. 49The Rw<strong>and</strong>an Ing<strong>and</strong>o-process .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 496. Selected Country Fieldwork: Cambodia, Colombia <strong>and</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a ..................................................... 55Cambodia ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 55Background <strong>and</strong> Rationale .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 55The Demise of the Khmer Rouge .................................................................................................................................................................................. 56The W<strong>in</strong>-W<strong>in</strong> Policy: Pragmatism Prevails <strong>in</strong> the Short Run ...................................................................... 58<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> Through Defacto Autonomy ............................................................................................................. 58Challenges, Issues <strong>and</strong> Key Lessons ........................................................................................................................................................................... 59Colombia .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 61Background <strong>and</strong> Rationale .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 61The Paramilitary (AUC) ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 62Corporación Democracia – a Transitional Institutional Arrangement ............................. 63Shareholder Agro Bus<strong>in</strong>ess as an <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> Measure ..................................................... 64Individual DDR: Cooptation of Combatants .................................................................................................................................... 66The “Soft Polic<strong>in</strong>g” Track .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 67Challenges, Issues <strong>and</strong> Key Lessons ........................................................................................................................................................................... 67Ug<strong>and</strong>a ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 69Background <strong>and</strong> Rationale .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 69The Labora Farm Experiment – a Halfway-House Arrangement ................................................ 70Strategic Military Integration .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 72Ug<strong>and</strong>a National Rescue Front II ................................................................................................................................................................................... 72Challenges, Issues <strong>and</strong> Key Lessons ........................................................................................................................................................................... 73

7. Comparative Analysis:Contextual Factors Shap<strong>in</strong>g the Choice of IS Measures ........................................................................................... 75The Importance of Contextual Factors ................................................................................................................................................................... 751. The Nature <strong>and</strong> Duration of the Conflict ....................................................................................................................................... 76II. The Nature of the Peace .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 77III. Governance Capacity <strong>and</strong> Reach of the State .................................................................................................................... 79IV. The State of the Economy: Labor Absorption <strong>and</strong> Property Rights .......................... 79V. The Character of Communities <strong>and</strong> Combatants .................................................................................................... 80Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Social Cohesion <strong>and</strong> Control Structures ............................................................................................................ 81The Importance of Agency, Livelihood, <strong>and</strong> Legitimacy .................................................................................................. 81Establish<strong>in</strong>g Incentives through Transitional Institutional Arrangements .............................. 82Convert<strong>in</strong>g Potential Spoilers to Stakeholders ...................................................................................................................................... 83Manag<strong>in</strong>g Risks ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 848. Conclusions <strong>and</strong> Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................................................ 87Buy<strong>in</strong>g Time <strong>and</strong> Space Dur<strong>in</strong>g Early Transition .................................................................................................................................. 8 7Gett<strong>in</strong>g the Transitional Incentives<strong>and</strong> Institutional Arrangements Right .......................................................................................................................................................................... 88Key Recommendations to Negotiators, Mediators,<strong>and</strong> DDR-SSR Program Planners .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 89ANNEX 1Def<strong>in</strong>itions of DDR term<strong>in</strong>ology established by the UN ............................................................................................... 91ANNEX 2Methodology: Interview Guide <strong>and</strong> Sample Thematic Questionaire .......................................... 93ANNEX 3Select Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 99

Executive SummaryIn the early phase of a transition from war to peace, numerous political aspirations<strong>and</strong> concerns of <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> groups must be carefully balanced. Mov<strong>in</strong>gfrom military conflict to susta<strong>in</strong>able peace requires a gradual adjustment by theconflict<strong>in</strong>g parties from a dependence on military sources of power to an abilityto operate as civilian actors <strong>in</strong> a peacetime society. Many DDR <strong>and</strong> SSR processesfail because the political environment (i.e. primarily the trust <strong>and</strong> confidence thateach party will stick to what have been agreed) are not ripe at the time of sign<strong>in</strong>gan agreement. Mediation efforts, program plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> even term<strong>in</strong>ology mustbe sensitive to cultural, economic, social <strong>and</strong> historical circumstances, allow<strong>in</strong>g forownership of a peace process, by its relevant stakeholders.The Stockholm Initiative on DDR recommended that “In order to avoidgaps between the short-term <strong>and</strong> the long-term focus, consideration might be given totemporarily ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ex-combatants, who are designated for a DDR programme, <strong>in</strong> amilitary structure, i.e. ‘hold<strong>in</strong>g pattern’. Such an <strong>in</strong>terim solution would provide the time<strong>and</strong> space for debrief<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> demilitarisation of the m<strong>in</strong>dset of ex-combatants.” (F<strong>in</strong>alReport, 2006). Further studies were recommended on “transitional mechanisms thatwould allow control over armed groups while await<strong>in</strong>g political solutions” (Test<strong>in</strong>g thePr<strong>in</strong>ciples, 2007).To better underst<strong>and</strong> such transitional mechanisms for balanc<strong>in</strong>g security <strong>and</strong>development, this study has been conducted by the Folke Bernadotte Academy<strong>and</strong> Sthlm Policy Group dur<strong>in</strong>g 2007/08. It elaborates on the idea of “hold<strong>in</strong>gpatterns”, as a possible means of deal<strong>in</strong>g with some of the obstacles to peace. Thestudy develops the concept of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> (IS), def<strong>in</strong>ed as measures thatMAY be used to keep former combatants’ cohesiveness <strong>in</strong>tact with<strong>in</strong> a military or civilianstructure, creat<strong>in</strong>g space for a political dialogue <strong>and</strong> the formation of an environmentconducive to social <strong>and</strong> economic re<strong>in</strong>tegration.In addition to a review of available literature, the study <strong>in</strong>cludes three <strong>in</strong>-countrycase studies where <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> measures have been put to the test:In Cambodia, we have studied the process <strong>in</strong> which former Khmer Rouge (KR)comm<strong>and</strong>ers were “de facto” provided an autonomous region with<strong>in</strong> the state11

<strong>in</strong> which <strong>in</strong>ternal re<strong>in</strong>tegration could be h<strong>and</strong>led without external <strong>in</strong>terference.(Study carried out by the Advocacy Policy Institute).In Colombia, our case study exam<strong>in</strong>es the processes of collective re<strong>in</strong>tegrationof paramilitaries, with comm<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> control structures kept <strong>in</strong>tact, <strong>and</strong>simultaneous <strong>in</strong>dividual re<strong>in</strong>tegration of FARC <strong>and</strong> ELN rebels <strong>in</strong> civil-militaryroles dur<strong>in</strong>g ongo<strong>in</strong>g conflict/negotiations. (Study carried out by Fundación Ideaspara la Paz).In Ug<strong>and</strong>a, we have studied the example of the Labora farm, where LRA(Lord’s Resistance Army) troops were offered civilian alternatives <strong>in</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>gfor themselves <strong>and</strong> their families, with their military organization partly <strong>in</strong>tact.(Study carried out by the Kampala International School of Ethics <strong>and</strong> the Ug<strong>and</strong>aAmnesty Commission).The ma<strong>in</strong> rationale for IS-measures, common to all the cases exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> thisstudy, has been to help put an end to a situation of spiral<strong>in</strong>g violence <strong>and</strong> reducethe risk of resumption of hostilities by hold<strong>in</strong>g former combatants <strong>in</strong> formalstructures, thereby ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a critical level of security. We have identified atypology of five categories of arrangements that fall with<strong>in</strong> the IS-def<strong>in</strong>ition:1) creation of civilian service corps; 2) military <strong>in</strong>tegration arrangements; 3) creationof transitional security forces; 4) dialogue <strong>and</strong> sensitization programs <strong>and</strong> halfwayhousearrangements; 5) different forms of transitional autonomy. These categories arenot precise or mutually exclusive. In fact, <strong>in</strong> many cases <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>measures conta<strong>in</strong> elements resembl<strong>in</strong>g the characteristics of two or more of thesecategories.The objectives of <strong>in</strong>terim stabilization relate to the state level (to solveoutst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g issues relat<strong>in</strong>g to powers-shar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional frameworks) as wellas to community- (to allow for <strong>in</strong>itial sensitization prepar<strong>in</strong>g for the return ofex-combatants, <strong>and</strong> a thorough analysis of transitional justice <strong>and</strong> reconciliationneeds) <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividual level (guarantee security through the ma<strong>in</strong>tenance ofcohesion through familiar structures, the sense of agency <strong>and</strong> legitimacy throughtransitional livelihood, <strong>and</strong>/or room for life skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> psycho-socialsupport).It is important to note that the concept of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> is not proposedas a m<strong>and</strong>atory first step <strong>in</strong> peace build<strong>in</strong>g, nor should it necessarily be conceivedas a new component of a DDR-SSR process. In fact, it may be considered a pre-DDR programme to manage security risks of premature demobilization. Theunderly<strong>in</strong>g assumption of the study, however, is that sometimes, conventionaltools are not sufficient to deal with security concerns <strong>in</strong> the immediate aftermathof violent conflicts. In such situations <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> could be <strong>in</strong>troduced toallow for other enabl<strong>in</strong>g factors to fall <strong>in</strong>to place.12

1.I. IntroductionThe necessity to <strong>in</strong>terl<strong>in</strong>k security <strong>and</strong> development oriented activities formsthe basis for contemporary <strong>in</strong>ternational peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g efforts. A number ofpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g tools are available to facilitate the war to peace transition. Theconcepts of Disarmament, Demobilization <strong>and</strong> Re<strong>in</strong>tegration (DDR) <strong>and</strong><strong>Security</strong> Sector Reform (SSR) are two such tools. They can be employed tofacilitate the transfer of control over the security <strong>and</strong> military apparatus tocivilian authorities (i.e. break<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g comm<strong>and</strong> structures) while cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>gthe political dialogue <strong>and</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g confidence between former rivals throughpower shar<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms. The concept of Transitional Justice (TJ), deal<strong>in</strong>gwith crimes committed by one or both sides to a conflict, is another key concept<strong>in</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g processes. Although TJ modalities are not the primary focusof this study, it is important to recognize <strong>and</strong> address justice concerns whenimplement<strong>in</strong>g DDR <strong>and</strong> SSR programs to ensure legitimacy <strong>and</strong> accountability,especially through the application of transparent vett<strong>in</strong>g processes.The successful employment of these peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g tools is dependent on acerta<strong>in</strong> level of stability, often lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the immediate aftermath of a violentconflict. This study sets out to explore ways <strong>in</strong> which m<strong>in</strong>imum levels of security<strong>and</strong> stability can be atta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the early phase after a peace agreement has beennegotiated <strong>and</strong> signed or when a cessation of hostilities is agreed. The work<strong>in</strong>ghypothesis is that political processes to build susta<strong>in</strong>able peace take time –often more than is available <strong>in</strong> the fragile period follow<strong>in</strong>g a peace agreement.Lack of quick results on the ground <strong>and</strong> impatience on both sides are oftenserious challenges. A rush to declare peace (<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the case of the <strong>in</strong>ternationalcommunity – to mark an exit strategy), <strong>in</strong> the absence of stability <strong>and</strong>opportunities for successful implementation of peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiatives, is onemajor risk factor for relapse <strong>in</strong>to violence.This race aga<strong>in</strong>st time <strong>in</strong> early peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g is at the heart of the topic of thisstudy. The tool – or menu of options – that is proposed can be described as a time-13

out or a “hold<strong>in</strong>g pattern”, <strong>in</strong> order to allow for cont<strong>in</strong>ued political dialogue <strong>and</strong>measures to prepare <strong>in</strong>stitutions, communities <strong>and</strong> combatants for long-termpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegration efforts. The term <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>(IS) is usedto conceptualize this phase of prepar<strong>in</strong>g for a susta<strong>in</strong>able transition. Unlike otherpeacebuild<strong>in</strong>g tools <strong>and</strong> concepts, <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> aims to describe a typeof measure def<strong>in</strong>ed by its tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> purpose, rather than a concrete measuredef<strong>in</strong>ed by its design. Hopefully this concept (<strong>and</strong> an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the keycontextual factors shap<strong>in</strong>g its use) can help broaden the range of options availableto negotiat<strong>in</strong>g parties, mediators <strong>and</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g program designers <strong>in</strong> thefield. Throughout the study, we will go through a number of possible designs ofIS-measures <strong>and</strong> analyze their respective strengths <strong>and</strong> weaknesses. The aim is todraw general lessons <strong>and</strong> conclusions from relevant cases <strong>and</strong> experiences whilema<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g that no bluepr<strong>in</strong>t can be established that is universally applicable.The research stems from the Stockholm Initiative on DisarmamentDemobilization Re<strong>in</strong>tegration (SIDDR), <strong>and</strong> has been commissioned by theSwedish Government through the Folke Bernadotte Academy <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>anced by theSwedish M<strong>in</strong>istry for Foreign Affairs. In the follow<strong>in</strong>g section, the background<strong>and</strong> purpose of the research project is outl<strong>in</strong>ed.The Stockholm Initiative on DisarmamentDemobilization Re<strong>in</strong>tegrationIn recent years, processes of Disarmament, Demobilization <strong>and</strong> Re<strong>in</strong>tegration(DDR) of former combatants have been placed at the center of the <strong>in</strong>ternationalcommunity’s support for peace processes (See for example SIDDR; UN IDDRS;the OECD/DAC CPDC-network; EU concept for support to Disarmament,Demobilization <strong>and</strong> Re<strong>in</strong>tegration; the AU Framework Document for <strong>Post</strong>Conflict Recovery <strong>Development</strong> – web pages provided <strong>in</strong> references). The DDRconcepthas gradually emerged from the lesson that a peace agreement <strong>and</strong>deployment of peacekeep<strong>in</strong>g operations does not automatically lead to long-termstability. It has become clear that <strong>in</strong> order to consolidate peace, these efforts mustbe coupled with longer-term peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiatives. DDR l<strong>in</strong>ks the <strong>in</strong>itial postconflictphase of stabilization, disarmament <strong>and</strong> demobilization with programsfor more long-term social <strong>and</strong> economic re<strong>in</strong>tegration of combatants.However, <strong>in</strong> spite of this approach where the security <strong>and</strong> development nexus istaken <strong>in</strong>to account, many DDR-processes fail to susta<strong>in</strong> a peaceful development.Still, almost half of all conflicts that end through negotiated agreement relapse<strong>in</strong>to violence with<strong>in</strong> five years (see Uppsala University, Department of Peace <strong>and</strong>14

Conflict Research Database). All too often, DDR has been approached from aprimarily technical perspective, neglect<strong>in</strong>g the importance of the surround<strong>in</strong>gpolitical <strong>and</strong> social environment.1.In 2004, the Swedish M<strong>in</strong>istry for Foreign Affairs <strong>in</strong>itiated the StockholmInitiative on Disarmament Demobilization Re<strong>in</strong>tegration (see SIDDR BackgroundStudies, F<strong>in</strong>al Report <strong>and</strong> Test<strong>in</strong>g the Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples). Aware of the challenges<strong>and</strong> opportunities of DDR <strong>in</strong> post conflict peace processes, the aim was to createpredictable frameworks for successful implementation of such programs. TheSIDDR was organized as an <strong>in</strong>ternational work<strong>in</strong>g process, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g nongovernmental(NGO) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter-governmental (IGO) organizations as wellas government representatives. In 2006, a F<strong>in</strong>al Report was presented to theSecretary General of the United Nations. The Report states that the primary aimof DDR is to contribute to a secure <strong>and</strong> stable environment <strong>in</strong> which an overallpeace process <strong>and</strong> transition to susta<strong>in</strong>able development can be achieved. It is only<strong>in</strong> this k<strong>in</strong>d of ‘enabl<strong>in</strong>g’ environment that political <strong>and</strong> security oriented reforms,as well as social <strong>and</strong> economic reconstruction <strong>and</strong> longer-term development, cantake root.The Stockholm Initiative on DDR elaborated on the early phase of post-conflictsituations, where there might be a peace agreement signed at the high politicallevel, but where the options <strong>and</strong> opportunities for <strong>in</strong>dividual soldiers are oftenvery scarce. The SIDDR unbundled the concept of re<strong>in</strong>tegration, propos<strong>in</strong>g animmediate short-term focus on transitional re<strong>in</strong>tegration of former combatantsaimed at primarily stabiliz<strong>in</strong>g a fragile peace. This early re<strong>in</strong>tegration was referredto as Re<strong>in</strong>sertion, us<strong>in</strong>g the term<strong>in</strong>ology of the United Nations (see reference tothe UN IDDRS below). In fact, the term<strong>in</strong>ology <strong>and</strong> concept of “Re<strong>in</strong>sertion” was<strong>in</strong>itially <strong>in</strong>troduced as a “transitional safety net phase” <strong>in</strong> the 1996 multi-countrystudy on demobilization <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegration programs undertaken by the WorldBank (Colletta, Kostner <strong>and</strong> Wiederhofer, 1996). Although the primary focuswould be to guarantee that former combatants do not need to return to violenceto make a liv<strong>in</strong>g, all <strong>in</strong>itiatives must be tied to a long-term plan for susta<strong>in</strong>ableeconomic <strong>and</strong> social development.In 2006, work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> parallel with the SIDDR process, the United Nations’<strong>in</strong>ter-agency work<strong>in</strong>g group on DDR established the Integrated DDR St<strong>and</strong>ards(IDDRS) as guidance for technical support, f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> implementation ofDDR programs. Through the IDDRS, common def<strong>in</strong>itions of the term<strong>in</strong>ology:Disarmament, Demobilization, Re<strong>in</strong>sertion <strong>and</strong> Re<strong>in</strong>tegration, were established(See www.unddr.org or Annex 1 for def<strong>in</strong>itions).15

Generative Dialogues <strong>in</strong> Promot<strong>in</strong>g Peace ProcessesThe SIDDR work<strong>in</strong>g process identified a need to further explore the relationshipbetween the DDR concept <strong>and</strong> the context <strong>in</strong> which DDR-programs wereimplemented. The Swedish Government Agency, Folke Bernadotte Academy,was m<strong>and</strong>ated to run a follow-up project; test<strong>in</strong>g the recommendations <strong>and</strong>conclusions of the SIDDR F<strong>in</strong>al Report. Whereas the SIDDR report focused onthe concept of DDR <strong>and</strong> its role <strong>in</strong> relation to parallel peace build<strong>in</strong>g concerns(e.g. SSR, justice, governance, <strong>and</strong> socio-economic recovery) the follow-up projectelaborated further on the political dynamics of the DDR-SSR <strong>in</strong>terface. Thef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the SIDDR were brought to the field <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduced to parties <strong>and</strong>negotiators <strong>in</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g peace talks.The SIDDR had asserted that mediation efforts, program plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> eventerm<strong>in</strong>ology must be sensitive to cultural, economic, social <strong>and</strong> historicalcircumstances, allow<strong>in</strong>g for real ownership of the DDR-process by its relevantstakeholders. Experiences from the follow-up project suggest that deal<strong>in</strong>gwith disarmament <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegration of former combatants under an adaptedterm<strong>in</strong>ology, such as ‘demilitarization <strong>and</strong> economic ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g’ (as <strong>in</strong>M<strong>in</strong>danao) or ‘management of armies <strong>and</strong> arms’ (as <strong>in</strong> Nepal), can help establishthe trust <strong>and</strong> confidence necessary to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a process of dialogue. For the sakeof consistency, this report will use the concept DDR as def<strong>in</strong>ed by the SIDDR<strong>and</strong> IDDRS, underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g that the determ<strong>in</strong>ants of successful DDR, especiallyre<strong>in</strong>tegration, must be identified <strong>and</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ed with<strong>in</strong> the context of each particularpeace process.Rationale for a Study of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>(or “Hold<strong>in</strong>g Patterns”)While the vast majority of available literature advocates that DDR programsshould be designed <strong>and</strong> implemented with<strong>in</strong> an overall peace strategy, there islittle precise guidance to be found on the topic. The determ<strong>in</strong>ants of effectivere<strong>in</strong>tegration among <strong>in</strong>dividual combatants are often difficult to p<strong>in</strong> down(Humphreys <strong>and</strong> We<strong>in</strong>ste<strong>in</strong>, 2005). This is particularly apparent <strong>in</strong> relation to theearly phase where the conditions might not yet be optimal for a DDR process.From an implementation po<strong>in</strong>t of view, the knowledge-gap regard<strong>in</strong>g theformative <strong>in</strong>itial stages of DDR program design <strong>and</strong> implementation leaves anumber of urgent questions unanswered. For example: How to deal with largenumbers of poorly educated <strong>and</strong> unskilled former combatants, <strong>and</strong> mid- <strong>and</strong>16

upper-level comm<strong>and</strong>ers <strong>in</strong> an economy with very limited labor absorptioncapacity? How to restructure a security sector while simultaneously absorb<strong>in</strong>gcombatants <strong>in</strong>to that sector? How to guarantee that a “security vacuum” is not<strong>in</strong>advertently created? Unsettled issues of political power shar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> position<strong>in</strong>goften further complicate the situation.1.The follow-up project noted that many DDR processes fail because the politicalcircumstances are not ripe at the time of sign<strong>in</strong>g an agreement. Often, what isprimarily lack<strong>in</strong>g is mutual trust <strong>and</strong> confidence between the parties. Furtherstudies were therefore recommended on “transitional mechanisms that would allowcontrol over armed groups while await<strong>in</strong>g political solutions” (SIDDR Test<strong>in</strong>g thePr<strong>in</strong>ciples p 35). This was <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with the SIDDR F<strong>in</strong>al Report’s statement that“In order to avoid gaps between the short-term <strong>and</strong> the long-term focus, considerationmight be given to temporarily ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ex-combatants, who are designated for a DDRprogramme, <strong>in</strong> a military (or civil) 1 structure, i.e. ‘hold<strong>in</strong>g pattern’. Such an <strong>in</strong>terimsolution would provide the time <strong>and</strong> space for debrief<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> demilitarisation of the m<strong>in</strong>dsetof ex-combatants” (SIDDR F<strong>in</strong>al Report p 25).In light of these challenges <strong>in</strong> the early phase of war to peace transitions, thisstudy seeks to elaborate on the idea of “hold<strong>in</strong>g patterns”, referred to <strong>in</strong> this studyas <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>, as a possible means of deal<strong>in</strong>g with some of the obstaclesto peace outl<strong>in</strong>ed above. The work<strong>in</strong>g hypothesis is that reshap<strong>in</strong>g “comm<strong>and</strong>”structures, but keep<strong>in</strong>g former combatants <strong>in</strong> their exist<strong>in</strong>g organizational“control” structures (i.e. ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g their social cohesion) for a limited periodof time, before <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong>to the (reformed) security apparatus <strong>and</strong>/orre<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong>to productive civilian lives, might be a more effective <strong>in</strong>terimstabiliz<strong>in</strong>g strategy than poorly planned demobilization <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegrationprograms or premature <strong>Security</strong> Sector Reform.1. Author’s parenthesis added17

2.2. Sett<strong>in</strong>g the Stage:Challenges <strong>in</strong> Early Transition<strong>and</strong> Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>gUnderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the Key Contextual FactorsIn the early phase of a transition from war to peace, numerous political aspirations<strong>and</strong> concerns of <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> groups must be carefully balanced. Mov<strong>in</strong>gfrom military conflict to susta<strong>in</strong>able peace requires a gradual adjustment by theconflict<strong>in</strong>g parties from a dependence on military sources of power to an abilityto operate as civilian actors <strong>in</strong> a peacetime society. While adjust<strong>in</strong>g to a civilianpolitical arena may be imperative for the leadership level, a war to peace transitionoften entails serious implications for <strong>in</strong>dividual combatants as well. In a civiliansociety, they must f<strong>in</strong>d realistic alternative livelihoods, without the use of militaryforce. With an average implementation timeframe of 3–5 years, as suggested <strong>in</strong>a recent analysis from Escola de cultura de pau (Caramés, Fisas <strong>and</strong> Sanz, 2007),look<strong>in</strong>g at all active DDR programmes 2006; the rapid launch of a programmedoes not guarantee a shortened disarmament <strong>and</strong> demobilization period.Generally, peace-agreements cannot reflect the concerns <strong>and</strong> aspirations of everystakeholder <strong>in</strong> a war-torn society. Many stakeholders may not even have a seat atthe negotiat<strong>in</strong>g table. For the sake of long-term stability, it is crucial that peaceagreementsare formulated so that they create an environment <strong>and</strong> a platform forcont<strong>in</strong>ued political dialogue <strong>and</strong> a framework for a long-term augmented processtowards last<strong>in</strong>g peace.Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the key contextual factors that shape war to peace transitions helpsprepare the ground for a successful long-term peace process. Such factors are:19

1. Nature <strong>and</strong> duration of the conflict:› Underly<strong>in</strong>g causes of conflict <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>and</strong> agenda of the fight<strong>in</strong>gparties (i.e. ideological, cultural <strong>and</strong>/or economic etc.).› The level of trust <strong>and</strong> confidence <strong>in</strong> political commitments betweenconflict<strong>in</strong>g parties <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> society at large (is there a tradition to stick toagreements? Is there a war fatigue with<strong>in</strong> the communities etc.).II. Nature of the peace:› Manner <strong>in</strong> which the conflict ended (i.e. imposed, negotiated, or third partymediated peace);› Framework for deal<strong>in</strong>g with war-time trauma, reconciliation <strong>and</strong>accountability (Transitional Justice).III. Governance capacity <strong>and</strong> reach of the state:› Ability to provide security for communities <strong>and</strong> return<strong>in</strong>g combatants;› Possibilities for alternative livelihoods <strong>in</strong> the military services <strong>and</strong> other partsof the security sector;› Capacity to organize transitional employment such as labor <strong>in</strong>tensive publicworks <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the long run, to create opportunities for economic development.IV. The state of the economy:› The base of the economy <strong>and</strong> market opportunities (access to l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>/orproperty rights, capital, technology, natural resources etc.);› Capacity of the economy to absorb unskilled labour.V. Character <strong>and</strong> cohesiveness of communities <strong>and</strong> combatants:› Level of ethnic homogeneity <strong>in</strong> the country <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> communities (i.e. both <strong>in</strong>relation to the causes of the conflict <strong>and</strong> the opportunities of communities towork towards socio-economic development for all ethnic groups);› Local cultural norms toward arms bear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> use;› Human capital of combatants (vocational <strong>and</strong> life skills);› Aspiration amongst the combatants <strong>and</strong> of their political <strong>and</strong> militaryleaderships as well as level of psychological capacity <strong>in</strong> the communities toabsorb <strong>and</strong> accept return<strong>in</strong>g combatants;› Nature of social cohesion among the combatants <strong>and</strong> the conflict affectedcommunities.<strong>Balanc<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Security</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Development</strong> – Stability <strong>and</strong> ChangeThere seems to be a general consensus amongst researchers <strong>and</strong> practitioners thatpost-conflict peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g is ideally to be seen as a multidimensional process,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g security, political <strong>and</strong> socio-economic aspects that re<strong>in</strong>force <strong>and</strong>strengthen each other (see for example UN Secretary General’s High Level PanelReport, 2004). These dimensions are not l<strong>in</strong>ear. They must be balanced at each20

po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> time. A ma<strong>in</strong> objective of peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g should be to improve the Human<strong>Security</strong> situation. Although it is still debated whether the Human <strong>Security</strong> conceptshould encompasses anyth<strong>in</strong>g beyond mere physical security, i.e. livelihoods<strong>and</strong> “social security” (Tadjbakhsh, 2005), the <strong>in</strong>troduction of the concept hasfacilitated the merger of the security <strong>and</strong> development agendas. The notion ofsecurity has been extended to <strong>in</strong>clude not only the security of state <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>and</strong>power structures, but also the security of <strong>in</strong>dividual citizens (see Human <strong>Security</strong>Report, 2005). This study rest upon this underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g.2.Downsiz<strong>in</strong>g the security apparatus too quickly, without f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g realisticalternatives, may threaten the peace process <strong>and</strong> the progress made <strong>in</strong> the politicalsphere. Ex-combatants cannot be re<strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to communities lack<strong>in</strong>g sufficientcapacity for labor absorption without risk<strong>in</strong>g that these combatants return toviolence to secure their livelihoods. Likewise, attempt<strong>in</strong>g to establish DDRprograms without deal<strong>in</strong>g with issues of justice <strong>and</strong> reconciliation could lead tostigmatization <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> the worst cases, persecution. Indeed, <strong>in</strong> the aftermath ofa peace agreement, overcom<strong>in</strong>g fear, mistrust <strong>and</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty amongst formercombatants is one of the most difficult challenges (Walter, 1997).Once the leaders agree to disarm <strong>and</strong> demobilize their troops they essentiallylose the barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g power they have <strong>in</strong> the peace process. Should the other partyrenege on its agreements they can suffer grave consequences. Warr<strong>in</strong>g partiescan thus f<strong>in</strong>d themselves <strong>in</strong> the classical “prisoner’s dilemma”, where <strong>in</strong>dividualrationality trumps collective good. The parties have no way of overcom<strong>in</strong>gfundamental distrust <strong>and</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. The risk – or perceived risk – of tak<strong>in</strong>g thefirst step is often simply too large.DDR-programs have a symbolic as well as a functional value. They can signal acessation of hostilities, thereby severely undercutt<strong>in</strong>g the legitimacy of warr<strong>in</strong>gmilitia, <strong>and</strong> re-establish a state monopoly over the use of force under a reasonablylegitimate government. They can also, if the potential of Transitional Justice <strong>and</strong>dialogue are properly <strong>in</strong>tegrated, contribute to a sensitization process <strong>in</strong> whichcombatants’ m<strong>in</strong>dsets are shifted towards a civilian life <strong>and</strong> the communities aresupported to deal with atrocities committed dur<strong>in</strong>g the conflict. However, thereare still gaps <strong>in</strong> our underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of exactly what factors can create environmentsconducive to successful transitions. Establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g trust betweenformer rival<strong>in</strong>g parties rema<strong>in</strong>s one of the key challenges.21

L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g SSR <strong>and</strong> DDR <strong>in</strong> <strong>Post</strong> Conflict Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Security</strong> is often the number one concern <strong>in</strong> the immediate aftermath of a violentconflict. Even <strong>in</strong> cases where an <strong>in</strong>ternational peacekeep<strong>in</strong>g force is present, safety<strong>and</strong> security can rarely be provided <strong>and</strong> guaranteed for all groups <strong>and</strong> stakeholders.A premature disarmament <strong>and</strong> demobilization of a rebel group or militia, whichmay be the only provider of security <strong>in</strong> a community, risks creat<strong>in</strong>g a securityvacuum <strong>in</strong> which crim<strong>in</strong>al groups take over (Schnabel <strong>and</strong> Ehrhart, 2005).Crime waves may underm<strong>in</strong>e popular faith <strong>in</strong> the peace process <strong>and</strong> empowerauthoritarian actors (Call <strong>and</strong> Stanley, 2001). The dilemma becomes even morecomplicated <strong>in</strong> situations where the parties to a peace process are controll<strong>in</strong>gdifferent parts of a country. With a Human <strong>Security</strong> approach, there may be reasonsfor postpon<strong>in</strong>g a DDR process, <strong>and</strong> rely<strong>in</strong>g on exist<strong>in</strong>g security forces with paid<strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>dividuals for the provision of transitional security. Gradually giv<strong>in</strong>gformer rebels a share <strong>in</strong> the state-monopoly over the provision of security couldfurther be a valuable strategic <strong>in</strong>strument <strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>able peace.A thorough analysis of the entire security system – i.e. military <strong>and</strong> paramilitaryforces, <strong>in</strong>telligence services, security management <strong>and</strong> oversight bodies, justice <strong>and</strong>law enforcement <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>and</strong> various civil <strong>and</strong> military <strong>in</strong>stitutions (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gboth civil society organizations <strong>and</strong> non-statutory security forces) – providesimportant <strong>in</strong>formation on the general security situation, the possibilities of thestate to provide security to its citizens <strong>and</strong> the capacity to absorb former irregularcombatants <strong>in</strong>to the national security apparatus. The concept of <strong>Security</strong> SystemReform (SSR), as def<strong>in</strong>ed by OECD/DAC, does not only aim at reconstruct<strong>in</strong>g thestate security <strong>and</strong> justice apparatus, but to achieve stability <strong>and</strong> security for boththe state <strong>and</strong> its citizens. This often entails <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g non-statutory securityforces <strong>and</strong> civil society groups as non-state oversight mechanisms with<strong>in</strong> theoverall reform framework. (OECD/DAC 2005).While conceptually different, DDR <strong>and</strong> SSR are synergistic (Brzoska, 2006)<strong>and</strong> can help us with at least two components of peace build<strong>in</strong>g; underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gthe macro determ<strong>in</strong>ants of demilitarization <strong>and</strong>; overcom<strong>in</strong>g obstacles tosuccessful long-term social <strong>and</strong> economic re<strong>in</strong>tegration. While the decision toreform the security system can sometimes be taken without a parallel process ofdemobilization <strong>and</strong> disarmament, the decision to undertake re<strong>in</strong>tegration of alarge number of ex combatants requires some clarity on the shape <strong>and</strong> size of thefuture security sector. DDR is normally dependent upon a function<strong>in</strong>g securitysystem – for general stability but also for capacity to absorb ex-combatants <strong>in</strong>to theregular security apparatus. Similarly, weaknesses <strong>in</strong> DDR-programs can often beexpla<strong>in</strong>ed by identify<strong>in</strong>g flaws <strong>in</strong> the exist<strong>in</strong>g security system.22

3.3. Conceptualiz<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>Clarify<strong>in</strong>g the Term<strong>in</strong>ologyFor the purposes of this study the concept of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> (IS) is def<strong>in</strong>ed as:› <strong>Stabilization</strong> measures that may be used to keep former combatants’ cohesiveness<strong>in</strong>tact with<strong>in</strong> a military or civilian structure, creat<strong>in</strong>g space <strong>and</strong> buy<strong>in</strong>g time fora political dialogue <strong>and</strong> the formation of an environment conducive to social <strong>and</strong>economic re<strong>in</strong>tegration.In study<strong>in</strong>g the potential of such measures as a means of ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>imumlevels of security <strong>in</strong> the immediate post-conflict period, it is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to takenote of a study by Hoddie <strong>and</strong> Hartzell (2003) show<strong>in</strong>g that one third of all peaceprocesses s<strong>in</strong>ce 1990 have <strong>in</strong>cluded components of Military Integration (MI),i.e. <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g former rebels <strong>in</strong>to the national army. They go on to argue thatsuccessful MI <strong>in</strong>creases the chances for susta<strong>in</strong>able peace.Military <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> redeployment of armed groups as transitional securityforces (as mentioned above), present two options that may be suitable <strong>in</strong> somepost-conflict sett<strong>in</strong>gs. However, an <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> measure, as def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>this study, could also be shaped as a civilian program where <strong>in</strong>tact groups of formercombatants are given civilian duties or simply provided with life-skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong>/or socio-psychological support. An <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> measure could thusbe employed as a military-, civilian-, or civil-military program. These choices areheavily dependent on the specific context <strong>and</strong> needs of each particular situation(see section on key contextual factors above).23

Presently, little literature exists on this type of military <strong>and</strong> similar civilian orcivil-military programs <strong>and</strong> the contextual factors, <strong>in</strong>centives <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutionalarrangements condition<strong>in</strong>g their use <strong>and</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g their success orfailure. Similarly, there is no documented knowledge as to their organization,management <strong>and</strong> implementation arrangements, vett<strong>in</strong>g procedures, specificprogram activities, costs <strong>and</strong> degree of effectiveness. A recent work by Glassmyer<strong>and</strong> Sambanis (2007) h<strong>in</strong>t at some of the potential condition<strong>in</strong>g factors whichmay <strong>in</strong>form the strategic use of military <strong>in</strong>tegration or transitional civil/militarymechanisms, for example, economic opportunity; clear military victory ornegotiated peace settlement; <strong>and</strong> the existence of a broad multi-dimensional peaceprocess. The subject of the present study is broader <strong>in</strong> focus, aim<strong>in</strong>g to fill a gap <strong>in</strong>documentation <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of contextual factors, <strong>in</strong>stitutional modalities<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>centives shap<strong>in</strong>g the formative early post-conflict period.Creat<strong>in</strong>g Space <strong>and</strong> Buy<strong>in</strong>g Time for Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>gThe ma<strong>in</strong> objective, common to all variations of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> measures,is to help put an end to the violence <strong>and</strong> reduce the risk of resumption of hostilitiesby hold<strong>in</strong>g former combatants <strong>in</strong> formal cohesive structures; ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a criticallevel of security <strong>and</strong> social support <strong>in</strong> order to “buy time” <strong>and</strong> create a space for:› Cont<strong>in</strong>ued political dialogue <strong>and</strong> a settlement of outst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g issues relat<strong>in</strong>gprimarily to the security sector <strong>and</strong> political power-shar<strong>in</strong>g;› Trust <strong>and</strong> confidence to emerge allow<strong>in</strong>g for political dialogue;› Formation of provisional bureaucratic structures <strong>and</strong> legal <strong>in</strong>struments;› Proper assessment of absorption capacity <strong>in</strong> different sectors of society <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>itial economic reconstruction (i.e. alterative options available for demobilizedcombatants);› Sensitization of communities, <strong>and</strong>;› Socio-psychological adjustment of combatants.This list <strong>in</strong>dicates that the primary objective of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>s – allow<strong>in</strong>gfor an environment conducive to social <strong>and</strong> economic re<strong>in</strong>tegration to emerge –relates to the state level as well as to community- <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual levels.At the state level a w<strong>in</strong>dow could be created to resolve outst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g political issuesrelat<strong>in</strong>g to powers-shar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional frameworks. This is central for theability to establish a susta<strong>in</strong>able post-peace-agreement process towards susta<strong>in</strong>ablepeace. Through ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a critical level of security, IS measures could also buytime for thorough needs-assessments <strong>and</strong> careful plann<strong>in</strong>g of SSR <strong>in</strong>itiatives (if24

needed) <strong>and</strong> DDR-programs. Unilateral defection by <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> groups fromthe peace process would also be made more costly as the benefits <strong>in</strong>herent already<strong>in</strong> the IS phase would be foregone.3.At community level, space is created for <strong>in</strong>itial sensitization prepar<strong>in</strong>g for thereturn of ex-combatants <strong>and</strong> a thorough analysis of Transitional Justice (especiallyvett<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>and</strong> reconciliation needs. The postponed return of combatants also givesprogram planners room for a careful assessment of the absorption capacity of localeconomies <strong>and</strong> labor markets as well as prepar<strong>in</strong>g community based programs <strong>and</strong>strategies for socio-economic re<strong>in</strong>tegration.From the <strong>in</strong>dividual’s po<strong>in</strong>t of view, an IS-phase could guarantee security throughthe ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of familiar group structures (even if the comm<strong>and</strong> is broken)<strong>and</strong> social cohesion, the sense of agency <strong>and</strong> legitimacy through transitionalemployment as a soldier on a wage <strong>and</strong>/or life skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> psycho-socialsupport prepar<strong>in</strong>g ex-combatants for life <strong>in</strong> a peace-time society <strong>and</strong> economy.More often than not ex-combatants feel excluded <strong>and</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>alized fromsociety. Their only bonds <strong>and</strong> support are their comrades <strong>in</strong> conflict <strong>and</strong> theircomm<strong>and</strong>ers. They often lack: a) An underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of a civilian economy;b) Hope <strong>and</strong> a sense of opportunity; c) The feel<strong>in</strong>g of agency through new foundeconomic <strong>and</strong> social skills <strong>and</strong>; d) Legitimacy <strong>and</strong> positive recognition to counternegative sterotypes .If carefully balanced, a period of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> could provide <strong>in</strong>dividualcombatants with the crucial basic elements of a successful long-term re<strong>in</strong>tegration;a sense of agency, transitional livelihoods, <strong>and</strong> the comfort of civic legitimacy <strong>and</strong>social acceptance.Strengthen<strong>in</strong>g Prospects for Durable PeaceIt is important to note that the concept of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> is not proposedas a m<strong>and</strong>atory first step <strong>in</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g; nor should it be conceived a necessaryelement of a DDR-SSR processes. The purpose of this study is not to offer a newprogram to be implemented <strong>in</strong> the peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g process; rather to conceptualize<strong>and</strong> learn more about the menu of stabiliz<strong>in</strong>g options available <strong>in</strong> the period oftransition between a peace agreement <strong>and</strong> its implementation. If the context ofa post-conflict situation allows for successful re<strong>in</strong>sertion packages or extendedperiods of encampment with<strong>in</strong> a conventional DDR-framework, there may notbe a need for additional mechanisms. The underly<strong>in</strong>g assumption of the study,however, is that sometimes, conventional tools are not sufficient to deal with25

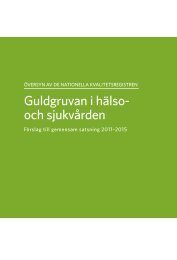

security concerns <strong>in</strong> the immediate aftermath of violent conflicts; especially wherethere is no clear victor <strong>in</strong> the conflict, weak local governance persists (especially <strong>in</strong>the provision of security), <strong>and</strong> the labor absorption is limited. In such situationsa phase of <strong>Interim</strong> DRAFT <strong>Stabilization</strong> – NOT could FOR be <strong>in</strong>troduced CIRCULATION to the negotiat<strong>in</strong>g parties,with the purpose of prevent<strong>in</strong>g the recurrence of violent conflict <strong>and</strong> allow<strong>in</strong>g forconditions <strong>and</strong> necessary the labor absorption for a susta<strong>in</strong>able is limited. In peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g such situations a phase process of <strong>Interim</strong> to fall <strong>in</strong>to place.<strong>Stabilization</strong> could be <strong>in</strong>troduced to the negotiat<strong>in</strong>g parties, with the purpose ofprevent<strong>in</strong>g the recurrence of violent conflict <strong>and</strong> allow<strong>in</strong>g for conditions necessaryfor a susta<strong>in</strong>able peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g process to fall <strong>in</strong>to place.Figure 1 – <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> <strong>in</strong> ContextFigure 1 – <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> <strong>in</strong> ContextIntroduc<strong>in</strong>g a phase of<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>(Individual level)- Serious security concerns- Lack of trust & confidence- Low labor absorption- Weak state <strong>in</strong>stitutions –<strong>in</strong>sufficient SSR- Situation premature forDDR-programsIntroduc<strong>in</strong>g a phase of<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>(State- <strong>and</strong> Communitylevels)Ex-combatantstemporarilyabsorbedPositive <strong>in</strong>centive- Initial crediblelivelihood forex-combatants- Space for lifeskills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g- Conditions conducive to succeedwith both SSR <strong>and</strong> DDR are created- Communities sensitized- Individual ex-combatants prepared forre<strong>in</strong>tegrationRemov<strong>in</strong>g negative<strong>in</strong>centiveSpace forcont<strong>in</strong>uedpoliticalprocess <strong>and</strong>plann<strong>in</strong>gBasis for long-termalternativelivelihood <strong>and</strong>re<strong>in</strong>tegration forex- combatantsRelativestability isma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed orachievedCommunitysensitization<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>itialeconomicreconstructionPositive <strong>in</strong>centiveThe figure 37. illustrates The figure illustrates how this how type this of <strong>Interim</strong> type of <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong>, or “hold<strong>in</strong>g or pattern”, pattern, could stabilizestabilize a fragile post-conflict situation, provide space for political dialogue <strong>and</strong>a fragile post-conflict program plann<strong>in</strong>g, situation, <strong>and</strong> remove provide negative space for <strong>in</strong>centive political thus dialogue turn<strong>in</strong>g potential <strong>and</strong> program spoilers plann<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>to <strong>and</strong>stakeholdersremove negative <strong>in</strong>centive thus turn<strong>in</strong>g potential spoilers <strong>in</strong>to stakeholdersIV. Study Objectives <strong>and</strong> Methodology<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> as a Strategic DDR-SSR Measure38. This study aims to identify, analyze, document <strong>and</strong> dissem<strong>in</strong>ate best practice <strong>and</strong>lessons learned <strong>in</strong> early post-conflict stabilization efforts to balance security <strong>in</strong> thenear term with medium- to long-term Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g under vary<strong>in</strong>g conditions. Acentral study objective has been to better underst<strong>and</strong> the underly<strong>in</strong>g, contextualfactors that strategically shape the choice, tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> sequenc<strong>in</strong>g of re<strong>in</strong>tegration2615

4.4. Study Objectives<strong>and</strong> Methodology<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> as a Strategic Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g MeasureThis study aims to identify, analyze, document <strong>and</strong> dissem<strong>in</strong>ate best practice <strong>and</strong>lessons learned <strong>in</strong> early post-conflict stabilization efforts to balance security <strong>in</strong> thenear term with medium- to long-term peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g under vary<strong>in</strong>g conditions.A central study objective has been to better underst<strong>and</strong> the underly<strong>in</strong>g contextualfactors that strategically shape the choice, tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> sequenc<strong>in</strong>g of re<strong>in</strong>tegrationprograms, which conta<strong>in</strong> military <strong>and</strong> civilian dimensions.The conceptual framework <strong>and</strong> lessons that have emerged from this study shouldbe of value to peace negotiators, mediators, <strong>and</strong> DDR-program designers. Theultimate objective is to provide peace negotiators (negotiat<strong>in</strong>g parties, mediators<strong>and</strong> facilitators) <strong>and</strong> DDR program design teams with lessons <strong>and</strong> best practices<strong>in</strong> order to impact negotiations as well as the design, outcome <strong>and</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>abilityof peace-mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> peace-build<strong>in</strong>g efforts. The report thereby also enforces theoverarch<strong>in</strong>g SIDDR recommendation that technical expertise on DDR, SSR orthe “management of arms <strong>and</strong> armies” as such, should be made available at earlystages of peace negotiations.The Methodology: From Desk Review to FieldworkThe work of this report is based on a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary desk study of select post-conflictcountries <strong>and</strong> programs resembl<strong>in</strong>g the type of IS measures described <strong>in</strong> previouschapters. Through the desk study, presented <strong>in</strong> summary fashion <strong>in</strong> this report,three particularly <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g cases were identified for deeper <strong>in</strong>-country fieldresearch: Cambodia, Colombia <strong>and</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a.27

The fundamental aim of the field research was to underst<strong>and</strong>, evaluate <strong>and</strong>hopefully contribute to fill<strong>in</strong>g the knowledge-gap <strong>in</strong> relation to “Hold<strong>in</strong>gPatterns” <strong>and</strong> similar <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Stabilization</strong> programs. Teams of consultants<strong>and</strong> local lead researchers have carried out field studies focus<strong>in</strong>g on a numberof ongo<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> past re<strong>in</strong>tegration programs that followed or <strong>in</strong>volved a visibletransitional element – thereby fall<strong>in</strong>g under the study-def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>Interim</strong><strong>Stabilization</strong>. For the sake of sav<strong>in</strong>g space <strong>in</strong> this study report, the case studieshave been modified from their orig<strong>in</strong>al versions by the editors (full versions of thestudies can be downloaded at the Folke Bernadotte Academy’s web page;www.folkebernadotteacademy.se). One of the overarch<strong>in</strong>g aims has been toidentify gaps <strong>and</strong> obstacles <strong>in</strong> theses programs <strong>and</strong> to garner an <strong>in</strong>dication of howto address future cases. Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary best practices has been extracted <strong>and</strong> outl<strong>in</strong>ed.Primarily through <strong>in</strong>-depth <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>and</strong> focal group <strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>g, the fieldresearch has aimed at develop<strong>in</strong>g a deeper underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the key elements <strong>and</strong>issues underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g the programs studied (see Annex 2). The selection process of<strong>in</strong>terviewees has been ‘purposive’ rather than necessarily ‘scientific’ (r<strong>and</strong>omized).A broad spectrum of <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>and</strong> op<strong>in</strong>ions on the selected cases has beensurveyed – <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, whenever possible <strong>and</strong> of substantive <strong>in</strong>terest, governmentofficials, army staff as well as representatives of paramilitary <strong>and</strong> rebel groups,representatives from bilateral <strong>and</strong> multilateral organizations, local <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>ternational civil-society actors (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g media), ex-combatants themselves <strong>and</strong>local community leaders. The use of multiple sources of <strong>in</strong>formation from vary<strong>in</strong>gprogrammatic perspectives has allowed for ‘triangulat<strong>in</strong>g’ <strong>and</strong> cross verify<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> the pursuit of relevant <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>and</strong> patterns of response.In February 2008, a sem<strong>in</strong>ar was held <strong>in</strong> Stockholm; discuss<strong>in</strong>g the prelim<strong>in</strong>aryf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the study <strong>and</strong> the conceptual framework on which it is build.Participants <strong>in</strong>cluded key members of the SIDDR-network, the UN IDDRS <strong>and</strong>other practitioners, policymakers <strong>and</strong> academics. Comments <strong>and</strong> contributionsfrom this sem<strong>in</strong>ar have been <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to this study report.28