ADMIRAL KIMMEL AND PEARL HARBOR - The Filson Historical ...

ADMIRAL KIMMEL AND PEARL HARBOR - The Filson Historical ...

ADMIRAL KIMMEL AND PEARL HARBOR - The Filson Historical ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>ADMIRAL</strong> <strong>KIMMEL</strong> <strong>AND</strong> <strong>PEARL</strong> <strong>HARBOR</strong>:HERITAGE, PERCEPTION, <strong>AND</strong> THE PERILS OF CALCULATIONWar is the province of uncertainty....-Karl yon C1ausewitz, On War (1832}JAMES RUSSELL HARRIS<strong>The</strong> lore of war holds that battles are won or lost in theminds of commanders. Similarly, the Prussian theorist Karl yonClausewitz, in the didactic rhetoric of nineteenth-century romanticism,celebrates the power of intellect over the fog of war:• . . [T]hree-fourths of those things upon which action in Warmust be calculated are hidden more or less in the clouds ofgreat obscurity. Here, then above all a fine and penetratingmlnd is called for, to search out the truth by the tact of itsJudgment. l<strong>The</strong>se pronouncements underscore the importance ofcognition in military command.But neither a folkloric admonitionnor a Prussian pedant here acknowledge the broader influenceson command decision.As the "new" militazy history hasdemonstrated, no such aspect of war can be understood apartfi-om its institutional, social, political, economic, technological, orintellectual context2.Fortunately, such perceptive studies ofJAMES RUSSELL HARRIS, M.A,, spectalizes in Kentucky military history; he isassistant editor at the Kentucky <strong>Historical</strong> Society.1 Karl yon Clausewltz, On War (ed. and trans. Anato] Rapaport; Baltimore,Md., 1968; orig. pub., 1832], 140.2 Richard H. Kohn, -<strong>The</strong> Social History of the American Soldier: A Reviewand Prospectus for Research," Amerfoan Histoclad Review 86 [] 981 ): 253 -67; PeterKarsten, "<strong>The</strong> 'New' Military History: A Map of the Territory Exp}ored andUnexplored," American Quarterly 36 (I 984]: 389-418: Alfan i• Mi[lett, "AmericanMilitary History: Over the Top," in Herbert J. Bass, ed., <strong>The</strong> State of AmericanHistory (Chicago, 1970], 157-82; Renald H. Spector, "Milita• History and theAcademic World," Army History (Summer 1991): l-S; Peter Karsten, So/d/ers andSociety: <strong>The</strong> Effects ofMilitary Servlce and War on American Life •Vestport, Conn.,1978]; Richard A. Preston and Sydney F. Wise, Men in Arms: A History of Walfareand Its Interrelatinnships wiax Western Soctety (rev. ed.; New York, 1970). For aninternational perspective on the multitude of factors which influence militarycommand, see Martin van Creveld, Command • War [Cambridge, Mass., and<strong>The</strong> Fi]son Club History QuarterlyVol. 68, No. 3, JLfly, 1994 379

380 <strong>The</strong> l•Ison Club History Quarterly [JulyAnglo-American participation in the Second World War abound. 3Yet, few works focus exclusively on the ways a World War IIcommander's social and intellectual heritage figured in the calculationsand contingencies of a specific battle.Nevertheless. Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, commanderin chief of the Pacific Fleet. and Pearl Harbor constitute a goodcase study. Fortunately for the historian, the extensive officialinvestigations after the debacle compiled an extraordinarily detailedrecord of the orders, communications, attitudes, and perceptionsof those in command at Pearl Harbor. Without extensiveexamination of the testimony and exhibits, opportunities forhistorical misinterpretation flourish. In Kentucky historiography,for example, Admiral Kimmel has not yet emerged from theresponsibility-for-defeat quagmire, Historians have cast this nativeof Henderson, Kentucky, simply as an example of commandfailure, a scapegoat for national disaster, or as a man strugglingto redeem his reputation. 4Kimmel has not received analysis of his role as a memberof a proud profession or his place in the uncertain world of thesenior officer. Like the other Kentuckians who held senior navalrank in World War II (see appendix), he had to deal with a hostof variables. Consciously or unconsciously, his calculations hadto include the social, intellectual, and political heritage of hisinstitution; current institutional policy; difficulties of planning,London, 1985); John Keegan, 7he Mask of Comnmnd (New York, 1987); and TlmTravers, <strong>The</strong> Kfll•tg Groun• <strong>The</strong> British Army, •tte Western Front, and theEmergence ofModem Warfare, 1900-1918(London. 1987).3 Examples include Lee Kennett, G.I.: <strong>The</strong> Ameraxm Soldier in World War II(New York, 1987); John Ellis. <strong>The</strong> Sharp End: <strong>The</strong> J•ghting Man in World War//(New York, 1980); and Paul F•ssell. W•: Understanding and Behavior in theSecond World War (New York and Oxford, 1989). For a comprehensive survey ofthe Pacific war which employs both traditional and "new" methods of militaryhistory, see Ronald H. Spector, Eog/e Aga•st the Stm: <strong>The</strong> Amerlmn War withJapan (New York, 1985).4 Richard G. Stone, Kenluck•] Fejht•3 Men, 1861-1945 (Lexington, 1985),57758; Lloyd O. Gz-aybar, "Pearl Harbor Scapegoat." Lo•e Cour/er•/oumalMagazine, 3 December 1978, pp.10-18: Bill Weaver, "Kentuckian Under Fh'e:Admiral Klmmel and the Pearl Harbor Controversy," <strong>The</strong> F/tsort aub HistoryQuarterly 57 (1983): 151-74.

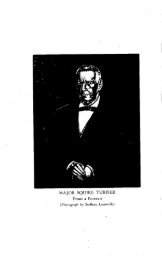

1994] Admiral Kimmel 381Admiral Kimmel in the late 1930sKentucky <strong>Historical</strong> Society

ii II

382 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [Julyintelligence, communication, and command relationships; thelimitations of his own character; the operations of chance; and -not incidentally - the designs of the enemy. With the hindsightof fifty years, it is obvious that Kimmel and many others madeegregious choices. And much ink has been spilled in the attemptto determine Kimmel's share of the blame, s Indeed. an irreduc-5 Kimmel's responsibility for the debacle has been debated since 194 I. Abasic source on Pearl Harbor is U.S. Congress, Pearl Harbor Attack: HearingsBefore the Jo/nt Committee on the Pearl Harbor Attack, 39 vols., 29th Cong., Istand 2d Sess., 1946 [hereafter PHA]. This work's several thousand unindexedpages (compiled by the Joint Congressional Committee which met from November1945 through May 1946) includes the testimonies and exhibits of hundreds ofwitnesses, plus relevant orders and dispatches. Also therein arc the tesUmoniesand exhibits of the previous seven official inquiries. Useful, too, is the Report ofthe Joint Committees on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack. 79th Cong.,2d Sess., 1946. <strong>The</strong> majority of the 1945-46 committee faulted the Hawaiiancommanders, especially Kimmel. for poor judgment and improper use of thesupposedly adequate information avadable to them. Most Washington officialswere not criticized. <strong>The</strong> minority report, however, contended that Washingtonsent neither clear information nor sufficient materiel to Hawaii. This report alsoasserted that blame for army-navy mistakes should go to the Washington officialswho selected the Hawaiian commanders.In December 1941, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox maintained thatKimmel and Major General Walter C. Short, commander of local army forces, hadnot anticipated an air attack on Pearl Harbor. But the most important factor, Knoxclaimed, was the obvious competency of the Japanese, not American derelictions.Later, one of the wartime investigations - the Navy Court of Inqu tiy (July-October1944] - found Kimmel innocent of negigence or dereliction of duty. This panel ofthree senior admirals crIUcized Admiral Harold R. Stark. who was Chief of NavalOperations in 1941, for poor judgment in not communicating some criticalinformation to Hawaii. Also in 1944, wartime Commander in Chief. United StatesFleet and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King, in commenting onthe Naval Court of Inqutiy, criticized Kimmel for not appto•iating the impendingdanger. In 1946 King cited in the official Report many causes for the disaster,among them was the poor exercise ofjudgment by Kimmel and Stark. Some othersenior commanders, however, hesitated to criticize Kirnrnel. Wartime Commanderin Chief, Pacific Fleet. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Fleet Admiral William F."Bull" Halsey held the opinions, respectively, that Pearl Harbor "could havehappened to anyone" and that Kimmel deserved none of the blame, not "any partof it." {E.B. Potter. N/m/tz [New York, 1976], 13; William F. Halsey and J. Bryan,Ill. Admiral Halseg's Story [New York. 1947], 82.1 Kimmel himself did notacknowledge ultimate culpability.Scholarly critics ofKimmel include Samuel Eliot Morison, History ofUnitedStates Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. 3, <strong>The</strong> R/s/r@ Sun/n the PadJ•, 1931-August 1942 (Boston. 1968; orig. pub. 1948) and Robert W. Love, Jr.. History ofthe U.S. Navy, Vol. 1, 1775-1941 (Harrisburg, Penn., 1992}. See also Love,"Fighting a Global War, 1941 - 1945," in Kenneth d. Hagan. ed., In Peoce and War:

1994] Admiral Kimmel 383ible fact of military life is command responsibility. But thenatural tendency to fix blame for failure can obscure as much asit reveals. Focus on one or more culprits - or even on a conspiracyof malefactors - covers up the interrelationships of individuals,institutions, and contingency. If historians view the matter inways more analytical than judgmental, other questions emerge.How did the heritage of the U.S. Navy affect Kimmel's perceptions?In the months and years before the surprise attack, whatproblems of command, strategy, and communication vexed him?Finally, what elements of contingency and chance, the storied"friction" of war, helped form or confound his calculations?IHusband E. Kimmel was heir to a formidable tradition.Since Revolutionary times, the American Navy had underwrittenU.S. International ties by guarding sea communications. Thismeasure of security enhanced peacetime commerce and growth.And from about 1850 naval officers sought eagerly to use burgeoningnational strength in expansionist ways, although somedoubt exists about the war-maklng capacity of the nineteenthcenturynavy. In times of peace an officer's aggressiveness tookform in fierce devotion to the state, the navy, or his own statusin the eloistered world of commissioned ranks. As the nineteenthcentury ended, many officers imbued themselves with a doctrineof sea power which, reinforced more by endless incantation thanby critical study, would give their profession a worldview withintellectual power and a bellicose perspective, sInterpretat•ns ofA•n Naval History, 1775-1978 (Westport, Conn., 1978). Astaunch defender of Admiral Stark, Love was, at the writing, preparing abook-length manuscript tentatively i•tled "Passage to Pearl Harbor." Also cri•ealof Kimmel is the typically simplistic analysis ofColonel T.N. Dupuy, *pearl Harbor:Who Blundered?" in Stephen W. Sears, ed., World War II: <strong>The</strong> Best of AmericanH•e (Boston, 1991), 28-59 [originally published in Amer•an Herltage,Febln•a i•- 1962]. Cataloging Kimmel's mistakes is Gordon W. Prange [with DonaldM. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon] in At Dawn We Slept: <strong>The</strong> Untold Swry ofpearl Harbor {New York, 198 I), Pearl Harbor: Verdict of History {New York, 1985)[unless otherwise noted, all references are to the paperback edition], and Dec. 7:<strong>The</strong> Day the Japanese Attacked pearI Harbor {New York, 1988).S Millet, "American Military Histo•," 161; Peter Karsten, <strong>The</strong> Naval

384 <strong>The</strong> F'•Ison Club History Quarterly [JulyLectures in 1886 by an obscure officer at the Navy WarCollege began the process. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan espouseda "new" conception of American sea power. America'splace in the coming age of global colonialism, commerce, andprojection of power was to be insured by command of the sea.His principle treatises included <strong>The</strong> Influence ofSea Power uponHistory, 1660-1783 (1890), <strong>The</strong> Influence of Sea Power on theFrench Revolution and Empire, 1793-1812 (1892), and Sea Powerand lts Relation to the War of1812 (1905}. He extolled a controlof the sea which would cut the enemy's communications, exhausthis resources, and close his ports. Indeed, the first object of anavy, Mahan wrote, was "to preponderate over the enemy's navyand so control the sea, then [thus] the enemy's ships and fleetsare the true objects to be assailed on all occasions. "7Of more immediate importance, however, was the appealMahan's ideas held for politicians. Secretary of the Navy B.F.Tracy's 1889 call for a force of twenty battleships which couldconduct offensive war, the Navy Policy Board's near-contemporaneousrecommendation for two hundred vessels capable ofcoastal defense and offensive operaUons, and the Naval Act of1890, which provided for three battleships, indicated politicalinclinations to put Mahan's ideas into practice. By 1898, ninebattleships had been authorized, and four were ready for the warwith Spain.s<strong>The</strong> aftermath of this "splendid little war" foreshadowedthe future of conflicts in the Pacific. <strong>The</strong> brief struggle be-Aristocracy: <strong>The</strong> Golden Age ofAnnapolis and the Emergence ofModern Amer6canNavaIism (New York and London, 1972), 267, 358.7 A.T. Mahan, <strong>The</strong>lnfluenceofSeaPoweruponHistory, 1660-17830]oston,1890), 288, in Russell F, Weig|ey, <strong>The</strong> Amertcan Way of War. A History of UnltedStates Military Strategy c•nd Policy (New York. 1973), 167-91,293. Presldent ofthe Naval War College for two terms, Mahan retlmd in 1896 as a rear admiral.served on the Naval War Board in 1898, and authored more than one hundredarticles and seventeen books on naval warfare. His reputation in contemporarynaval and poliucal circles grew to legendary status. See Robert Seager, II, A/fredThcvder Mahan: <strong>The</strong> Man and His Letters {Armapolis, Md., 1977).8 Edward Meade Earle, od., Makers of Modern Strategy: Military 7boughtfrom Matrhlavelll to Hitler (Princeton, 1944), 417-18. 429, 432, 436-37, 450;Weigley, A• Way of War, 178, 182-83.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 385queathed the Philippines, confirmed U.S. presence in locationslike Hawaii and Samoa, encouraged a naval presence in the FarEast, and inclined the Roosevelt and Taft administrations towardpro-Navy politics. For the U.S. Navy and for young EnsignKimmel, commissioned in 1906, a bright future beckoned. 9Butthe massive and rapid building program approved in the NavalAct of 1916, itself a reaction to the Great War in Europe, wascorrectly interpreted by the Japanese as a signal the UnitedStates would eventually challenge it for Pachqc hegemony.<strong>The</strong>concept of war with Japan began seriously to concern U.S.stratagists, lOplanners.Events, however, resisted the smooth scripting of naval<strong>The</strong> startling political and economic upheavals of the1920s and 1930s rearranged the naval world Mahan had envisioned.For Commander Kimmel, now progressing in rank andresponsibility, such broad influences helped define his mindset,For years, battleships had been regarded as the highest expressionof military technology and as fundamental units of measurein calculating relative national naval power,But the antiwaratmosphere after World War I produced the international WashingtonConference on the Limitation of Armaments (1921-1922),nine treaties, and twelve resolutions, all of which restricted armsdevelopment.Especially relevant to Kimmel's future were thenaval institution's response to treaty limitations and the U.S.pledge not to fortify bases west of Hawaii. 119 Thaddeus V. Tuleja, StatesmenandAdmirals: <strong>The</strong>QuestforaFarEasternNaval Policy (New York, 1963), 23; Edward S. Miller, War• Orange: <strong>The</strong> U.S.Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945 (Annapolis, Md., 1991], 25: "Rear AdmiralHusband E. Kimmel, U.S. Navy (Deceased)," Naval HistorlcaICenter, Washington,D.C. (hereafter "RADM Kimmel'); Clark G. Reynolds, Famous American Admirals(NewYork, 1978), 175-76.I0 Weig[ey, American Way of War, 243-44; Tulega, Statesmen andAdmirals,22-23.11 "RADM Kimmel'; Reynolds, Famous Admirals, 175-76; Robert O. Dulin,Jr,, and William H. Garzke, Jr., Battlesh•s--United States Battlesh•s tn WorldWarll•mapolis, Md., 1976), v; Stephen E. Pelz, Race to PearI Harbor: <strong>The</strong> Fa•ureof the Second London Naval Conference and the Onset of World War II [Cambridge,Mass., 1974], I; Love, History ofU.S. Navy, I : 526-27, 530; Stephen Roskfll, NatrdPolicy Between •te Wars, Vol. I, <strong>The</strong> Period of Anglo-Amerlt•n Antogonlsm,

386 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [July<strong>The</strong> treaty system's ballyhooed ten-year freeze on newcapital shipbuilding and U.S.-British parity in total tonnagecontained loopholes. (Japan received 6/10 of Anglo-Americantonnage and other nations even less.) <strong>The</strong>se international agreementsstill permitted vast latitude in battleship modernizationand the design of aircraft carriers and other weapons. Treatyrestrictions even spurred international construction of cruisers.destroyers, and submarines. Thus. the overarching lesson of the1920s for naval professionals like Kimmel was clear: politicaldirectives could modify, but not eliminate, the navy's mission.Indeed, the world of international politics and diplomacy couldnot even preclude the navy from aggressive pursuit of its petprograms. 12<strong>The</strong> U.S. Navy also continued to evolve its worldview, itssense of naval destiny transmitted to succeeding generations ofits personnel - especially to its officers. A central part of thatvision was the strategy for war against Japan, the most likelyopponent in any future conflict. Sophisticated plans for war withOrange (Japan in the color code assigned to schemes for hostilitieswith various nations) had begun early in the century. <strong>The</strong>plans had been formulated in 1911 by the Naval War College andofficially adopted in 1914 by the Navy's General Board, advisoryagency for war plans and army-navy relations. <strong>The</strong>y were henceforthdebated by naval officers until 7 December 1941. (A formof the Orange plan was revived during World War If.)i3Significant in the transmission of such concems to mid-1919-1929 (London, 1968). 328-30; Weigley, American Way of War, 245; GeraldE. Wheeler, Prelude to pearl Harbor: <strong>The</strong> United States Navy and fi•e Far East,1921-1931 (Columbia. Mo.. 1974), xii, 24, 56-57.12 Roskill, Anglo-A•nAna2gonisrr• 31 I. 328-30, 543; Pelz, Race to pear/Harbor. 1; Dulin and Garzke, Battleships, v. 3, 197; Philip T. Rosen, "<strong>The</strong> TreatyNavy, 1919-1937," in Hagan, ed., In Peace and War, 223-26; Thomas C. Hone,"Battleships vs. Aircraft Carriers: <strong>The</strong> Patterns of U.S. Navy OperatingExpenditures, 1932-1941 ," Military Affairs 41 (October 1977): 134-41; Wheeler.Prelude to Pearl Harbor, 60, 79.. 13 MiehaelVlahos. <strong>The</strong> Blue Sword: <strong>The</strong>Nat•WarCollegeandtheAmerk•nMission, 1919-1941 •lewport. R.I., 1980), 16; Miller, War Plz•n Orange, 2.5, 116;Louis Morton, Strategy and Command: <strong>The</strong> First• Years, United States Armyin World War//(Washington. 1962), 21-44, 67-91. 434-53.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 387level officers like Commander Kimmel was the Naval War College.In contrast to the more rudimentary instruction at the UnitedStates Naval Academy at Annapolis, the War College, in Newport.Rhode Island, served as the advanced school for the U.S. Navy'sbest and brightest. Selection to attend the senior course enhancedchances for entry into the command elite, the few whomade strategy and policy and co•ntested with each other fordominance. 14 But Kimmel's sojourn at the college narrowed,instead of broadened, his mind. Beginning in 1919, the presidentof the War College, Admiral william S. Sims, had reorientedthe school from Mahanian contemplation of the art ofwar. Sims'scollege, and the college of the next two decades, focused insteadon how officers should design war plans, make decisions, andissue orders. Is <strong>The</strong> college thus became almost a ritual forcareerists instead of an educational institution. In fairness, thestaff and students of this era truly did lack the challenge facedby Mahan and his colleagues. <strong>The</strong>ir fm-de-siecle struggle hadbeen to transform the U.S, Navy's traditional strategy of coastaldefense and commerce raiding.By the time Commander Kimmel arrived in Newport,Rhode Island, for the senior course in September 1925, the U.S.Navy possessed an offensive, worldwide mission and had beenreassured by the recent demonstration that political currents,like public antiwar sentiment and treaty restrictions, would notsink the navy. Logically, it was a small step to the inference thatnational policies deserved less than rapt attention and instantcompliance. Additionally, the naval collegians of the 1920s and1930s had little reason to challenge the by-then-hallowed conceptsof battleship primacy and the big, decisive sea battle. 1614 See V1ahos. Blue Sword. iii, iv, 28, 56. Historian Ronald H. Speetor holdsa Jaded view of the U.S. Naval Academy in the years between the world wars:"Successful midshipmen were expected to develop qualities of reliability,leadership, integrity, good judgment, loyalty to the service and to each other. Itwas this last that was especially stressed. Midshipmen left Annapolis with a livelyregard for the reputation of their service---and even more concern for their ownreputation #t the service." Ronaid H. Specinr, Eagle Against the Sun, 18.15 Ronald H. Spector, Professors of War: <strong>The</strong> Naval War College ar• theDevelopment of the Naval Profess•n (Newport, R.I., 1977), 145.

388 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [JulyEqually critical to the mindset of future naval commodores wasthe near obsession about war with Japan. <strong>The</strong> theses of officerslater prominent in World War II form almost a paean to historicaldeterminism. And in keeping with this context was the 1925observation of Commander Husband E. Kimmel. "History shows."Kimmel wrote. "that it generally takes a generation to get over'war weariness".... We will come into conflict with Japan ff shepursues an imperialist policy. "17Fleet exercises of the period more clearly demonstratedthe naval establishment's traditionalist predilections. For example,in Fleet Problem IX of 1929 a surprise air attack on thePanama Canal was successful, but the carriers were ruled sunkwhen they came within range of the "enemy" battleships. As aresult, conservative battleship admirals harped on this perceivedcarrier weakness as confirmation of battleship superiority. Yet.at this time, the conservatives truly did have reason to doubtaircraft usefulness at sea. Planes and carriers were then limitedin number by international treaties; thus, air operations wereseen at best as experimental. Also. darkness and bad weatherrendered the planes of these years ineffective. <strong>The</strong>re simply wasnot yet enough evidence to change minds. (Nevertheless,throughout the 1920s and 1930s naval leaders increasinglyrecognized the potential of air power for the defense or recaptureof the Philippines.) 18 Consequently, the fleet of battleships -despite the portents of fleet exercises and advancing technology- was still considered the navy's heart. To date. Kimmel'sextensive battleship and gunnery experience, rewarded officiallyby steady promotions and prestigious billets, reflected the endur-16 "RADM KimmeF; Spector, Professors of War, 150-51; Vlahos, Blue Sword.148, 150.17 Cdr. H.E. Kimmel. *<strong>The</strong>sis on Policy," 5 December 1925, Record GroupXIII, Naval <strong>Historical</strong> Collection, Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island. 17,in Vlahos, Blue Sword, 128.18 Waldo H. Heinriehs. Jr.. "<strong>The</strong> Role of the United States Navy," in Borg andOkamoin. eds.. Pearl HarborAs History, 204; Clark G. Reynolds, <strong>The</strong> Fast Carriers:<strong>The</strong> Forging of an Air Arm (New York, 1968), 17; Charles M. Melhorn, Two-BlockFox: <strong>The</strong> Rise of the Aircraft Carrier, 1911-1929(Annapolis, 1974). 3-23;Wheeler,Prelude to Pearl Harbor, 96-97.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 389ance of naval orthodoxy, Even as late as Fleet Problem XX {20-27February 1939). the game success of battleships - and theapparent ineffectiveness of planes and subs - reinforced the battlefleet concept for many senior commanders.19<strong>The</strong> dissonance between such placid traditionalism andthe upheavals of the 1930s is dramatic.During this decade.neither Captain Kimmel. now a rising star in the bureaucracy,nor the U.S. Navy could ignore the implications of a series ofominous diplomatic gatherings. <strong>The</strong> 1930 London Naval Conference.the London naval talks of 1934, and the Second LondonNaval Conference of 1936 in part revealed increasing Japanesemilitarism and impatience with treaties. Moreover. the deepeninginternational economic depression and Franklin DelanoRoosevelt's election as U.S. president supplied additional signsof unstable days ahead.FDR favored a big navy. as rising navalexpenditures throughout the 1930s showed,Pacific policies were inherently contradictory.but his naval andHe endorsed thenaval limitation treaty system, yet he vacillated on Japaneseexpansionism.His hopes for discouraging such expansionismwhile supporting the treaty restrictions kept the navy's roleunclear. 2o<strong>The</strong> uncertainty endured and the danger increasedafter Japan's January 1936 withdrawal from the naval treaties.Within months the U.S. announced plans to build twenty vessels.including its first two new battleships in twenty years.internal Japanese pressure to arm increased,Soon.Two battleshipswere reported under construction, and others were rumored tobe in the planning stages. A new arms race had begun. 2•19 Stephen Roskill, <strong>The</strong> Pet-lt• of Reluctant React, 1930-1939, vol 2 ofNaval Policy Between the Wars (London, 1968}, 475; Love, History of U.S. Navy,1:612-13.20 "RADM Klmmel'; Roskill, Anglo-AmericanAntagonism. 62, 67, 588; Love,History of U.S. Navy, I : 584, 598; Heinrichs, "Role of U.S. Navy," 199, 206, 208,210-Ii.21 Pelz, Race to Pearl Harbor, 198-99; Love. History of U.S. Navy. i: 59,593-95,606; Dulin and Garzke, Battleships, 34; Heinttchs, "Role of U.S. Navy,"215; Morison, Ris/ng Sun /n the Pac/f•, 30-31. For Japan's response tointernational naval treaties and its later war preparations, see Asada Sadao,"Japanese Admirals and the Policies of Naval Limitation: Kato Tomosaburo vs.Kato KanJ|," in Gerald O. Jordon, ed., Naval Warfare In the Twent•th Century

390 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [JulyAnother pressing consideration for the U.S. Navy was itsown growth. One hundred and fifty-six vessels and about thirtypercent more personnel had entered service between FDR's inaugurationand 1940. In that year. 592 vessels were afloat and138 were under construction. Plans called for two hundred morenew ships and many additional aircraft. 22 By the end of 1941.revised U.S. war plans accommodated various national coalitions,and ships under construction included eleven new carriersand two more battleships; ten new battleships were afloat. Significantnaval forces had by then moved from the Pacific to theAtlantic, and the Pacific Fleet was permanently based at PearlHarbor. Just as worrisome as these war preparations was theabsence of completed U.S. naval bases west of Hawaii. <strong>The</strong>Philippines were deemed likely to fall quickly to Japan. and theirrecapture was considered problematical. 23 <strong>The</strong> probable courseof events in the western Pacific would prove a major concern forthe Hawaiian command along with the long-established unreadinessof the Pacific Fleet. 24In sum. the years had produced a troubled harvest. Forthe U.S. Navy. the traditions of mission, battleship strategy.narrow education of its leaders, institutional distance from nationalpolicy, low combat readiness of its rapidly expanding force.and the probable early loss of the western Pacific together composeda dark vineyard. And at Pearl Harbor Rear Admiral Kimmel,from 1939 to 1941 the fleet's chief cruiser commander, was aboutto gather the bitter fruit. 2s(London. 1978), 141• I: Sadao Seno, "Chess Game with No Checkmate: Admirallnoue and the Pacific War," Naval War College Review, January-Februaly, 1974,pp. 26-39; Ito Masanourl and Roger Pineau, End of the Japanese Navy (trans.Andrew Y. Kuroda and Roger Pineau; Westport, Corm., 1956}, esp. Ch. I. Seealso John Toland, <strong>The</strong> Rising Sun: <strong>The</strong> Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire,193•1945 [2 vols.; New York, 1970}, esp. Vol. I.22 RoskiI]. Reluctant Rearmament, 472. 479; John Major, "<strong>The</strong> Navy Plansfor War." in Hagan. ed., In Peace and War, 251; RoskiU, Ang/o-Amerk:anAn•janism. 588, 593-95.23 Major. "Navy Plans for War." 247, 250, 257-58; Heinrlehs, "Role of U.S.Navy," 208-209, 216, 218-19, 223.24 PHA 14: 954-59. 963-70.25 "RADM Kimmel"

1994] Admiral Kirnmel 391IIOn 7 December 1941, the naval base at Pearl Harbor,Hawaii, became the nexus of tragedies.<strong>The</strong>re, conflicts of thepresent suddenly and disastrously collided with those of the past.Since World War I, during the years Husband E. Kimmel had risento high rank and the country had denied military realities, thenavy had been in a bloodless war. Battles with other institutionsover appropriations competed with plans for actual war againstprojected enemies.over turf.Units within the naval bureaucracy foughtAnd, ominously, the power to make decisions wasdistributed among many agents. Paramount concems remained,as in any peacetime navy, the appearance of organizational unity,tradition, and a cautious regard for new technology.To this mix of conflicting interests, the procedures ofAmerican strategic planning added great potential for confusion,contention, misunderstanding, and miscalculation. Almost collegialin tone, policy formation consisted of a dialogue betweencompeting theses in a small group of officers.Normally, aboutone hundred of thls command elite received copies of war plans.And much correspondence between these select commanderspreceded adoption of any formal design.Competing schemesclashed and coexisted, and factions or individuals identified witha plan did not coordinate immediately. 26By 1938, shiftingpotentials for international wartime coalitions, unsatisfactoryfleet exercises, and Japan's likely fortification of central Pacificislands compelled the retirement of War Plan Orange.Morecautious strategies began to replace the all-out thrust against thesingle Japanese enemy.By 1940, Plan Dog Ioption four inmilitary jargon) had evolved and gained approval at the highestmilitary-polltlcal levels.This brainchild of Admiral Harold I•Stark, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and Annapolis contempo-26 Heinrlchs, *RoIeofU.S. Navy" 197-98; Miller, War Plan Orange. 2. 9. Seealso Maurice Mafloff, "<strong>The</strong> Amerlcan Approach to War, 1919-1945)' in MichaelHoward, ed., <strong>The</strong> <strong>The</strong>ory anti Practice of War: Essays Presented to Captain B.H.LiddelIHart... [New York, 19661, 229-33, 241.

392 <strong>The</strong> l•ilson Club History Quarterly [Julyrary of Kimmel, incorporated coalitions of European allies andshifted American weight to the Atlantic. Thus. naval plans forPacific war were ordained defensive. But in the tradition ofAmerican strategic planning, Kimmel resisted the spirit of this"Europe first" strategy. 27Ironically, the exercise of command dissent - which wouldbring Kimmel to grief - had initially cleared his way to the top jobinthe Pacific. In the spring of 1940, the fleet had been sent fromits Califom|a base to Hawaii for maneuvers. But PresidentRoosevelt believed that German aggression in Norway and theLow Countries as well as the British retreat from Dunkirk requireda U.S. response on the international chessboard. Supposedlyto deter Japan from capitalizing on U.S., British, and Frenchconfusion, the United States Fleet received orders to retain Hawaiias a base of operations. Admiral James O. Richardson, commanderin chief of the fleet, loudly objected. Hawaiian facilities,he maintained, were inadequate for a modem fleet. Thus. beforetaking the offensive, the fleet would have to return to Califomiafor more men and supplies, and morale suffered at a base so farfrom the families of the crews. In short, the fleet was hampered,and the Japanese, who were fully aware of the weaknesses of theU. S. fleet, were not intimidated. Moreover, Richardson contended,depleting the scant fuel supply for extended Hawaiianoperations was unwise at a time of increased war tensions. Evenworse, the crews lacked full training. At the time of Kimmel'scommand, no main battery practice had taken place for a year. 2a27 Heinrlchs, "Role of U.S, Navy." 197-98; Miller, War Plan Orange, 2, 9; Pelz,Race to Pearl Harbor, 198-99; Love, History of U.S. Navy, l: 606-607; 629; Potter,N/m/tz, 52: Specter, E•jleAgalnst the Sun, 18, 65-67; Mark R. Lowenthal, "<strong>The</strong>Stark Memorandum and American National Security Process, 1940," in RobertW, Love, Jr., Changing Interpretations and New Sources in Naval History: Papersfor be Third Annual United States Naval Academy Naval Symposium fl•,ew York,1980), 352-59. See also Louis Morton, "Germany First: <strong>The</strong> Basic Concept ofAllied Strate•, in World War II," in Kent Roberts Greenfield, Command Decis/ons[Washington, D.C., 1960), 11-48.28 PHA 14: 954-59, 963-70; Potter, N/m/m, 4; Morison, Rising Sun in thePacific, 46-47; George C. Dyer, On the Troadmill to Pearl Harbor: <strong>The</strong> Memoirs ofAdmlraI James O. Richardson [Washington, 1973), 330; Pnlnge, At Dawn We Slept•37-38; PHA 6: 2569, 2498-99. Captain Vincent R. Murphy, Kimmers assistant

1994] Admiral Kimmel 393Throughout the summer and fail, Richardson proposederratic operations plans and continued to protest in increasinglyless tactful communications with Washington. Summoned to anOctober meeting at the White House, the admiral bluntly questionedRoosevelt's ability to direct military policy. Two days later.Richardson vehemently objected to a Roosevelt order for deployingembargo patrols westward from Hawaii and Samoa. Soonaller Richardson's histrionics, a search for his replacement began.This personnel problem fit neatly into CNO Stark's plans.For some time Stark had sought to remove Rear Admiral HayneEllis. lackluster head of the Atlantic Neutrality Patrol. Stark alsowanted, in accordance with the "Europe first" strategy, to upgradethat organization to fleet status and to increase its size. Inaddition, Stark approved of Richardson's removal; he had listenedto the complaints for months. President Roosevelt acquiescedto Stark's wishes, and, apparently aware of the need forwartime toughness in naval leaders, told him to replace theunsatisfactory admirals with *the meanest S.O.B.'s in the Navy."Rear Admiral Kimmel. commander of cruisers at Pearl Harbor,and Vice Admiral Ernest J. King of the navy's General Board*fitted the requirements to perfection. "29Noted within the navy for his professionalism, drive, andtact with superiors, Kimmel seemed to have qualities Richardsonlacked; Kimmel was also Stark's friend and protege. Richardsonhad enjoyed a similar position with the immediate past CNO.Admiral William D. Leahy. Thus meeting the perceived requirementsfor the job. Kimmel officially relieved Richardson on 1February 1941. He also took on Richardson's dual title, commanderin chief, Pacific fleet (CinCPAC) and commander in chief.United States fleet (CinCUS). <strong>The</strong> latter position alternated bewar-plansofficer, later echoed Richardson: "We could not have materially affected[Japanese] control [of the Pacific] whether or not the battleships were sunk atPearl Harbor. [<strong>The</strong> U.S. fleet could not attack effectlvely.] until. , . the rr•terialcondition of the ships was improved [with more antiaircrall weapons andreinforcements]. PHA 26: 207.29 Dyer. 7Yeacln•l to PearI Harbor. 435-36; Major. "Navy Progress for War."252-53; Love. History of U.S. Navy. I: 627-28.

394 <strong>The</strong> FIlson Club History Quarterly [Julytween commanders of the Atlantic. Pacific. and Asiatic fleets andwould insure Kimmel's overall superiority if two or more of thefleets operated together.However, this titulary concern, significantbecause of its typicality in a massive bureaucracy, wassomewhat academic. <strong>The</strong> three fleets never operated together. 3°Kimmel had suddenly jumped to the temporary rank offull admiral, an advance over forty-six senior officers.Althoughhe has been described as a workaholic and a perfectionist, hispersonal qualities probably had less bearing on his selection asCinCPAC than his contrast to Richardson.Professionally. Kimreelhad a "can do" attitude and an eagerness to confront Japan.In strategy, his thinking apparently reflected the recent, conservativeatmosphere of the Naval War College.troubling qualities as well.But Kimmel hadIn contrast to many senior officers.his command experience had been narrow. Before his CinCPACdays, Kimmel had served on seven battleships, as a gunneryadvisor to the British navy in World War I, as assistant directorof target practice and engineering ordnance, and as productionofficer at the Naval Gun Factory. 31Long experience with big shipsand big guns, the traditional themes of the early twentleth-centuryAmerican navy, solldiiied Kimmel's identification with navalorthodoxy.But no more important influences affected Kimmel's conductas CinCPAC than the navy's bureaucratic wars of the 1920sand 1930s.Throughout the 1920s the navy's Bureau of theBudget clashed with the Naval Subcommittee of the House AppropriationsCommittee.Limitations on funding and thus on30 Rear Admiral Arthur H. McCollum, "Unheeded Warnings," in PaulSttllwell, ed., Air Rald: Pead Harbor!: Recollections ofa Day oflrtfamy (Annapolis.1981}. 81 ; Vice Admiral W. R. Smedberg, III, to Gordon W. Prange, 27 July 1977,in Pearl Harbor. Verdict of History, 464; Donald Brownlow. <strong>The</strong> Accused.. <strong>The</strong>Ordeal of Rear Admlral Husband KimmeL U.S.N. (New York, 1968}, 38; Graybar,*Scapegoat." 14-15; Michael Slackman, Target: Pead Harbor (Honolulu. 1990), 8;Love. HtstoryofU.S. Navy. i: 626; Potter, Ntmitz. 5. Also on I February 1941 ViceAdmiral King, already commander of the Atlantic Neutrality Patrol, becamecommander in chief. Atlantic Fleet.31 Prange, Pear/Harbor: Verdict of History, 419-22 and At Dawn We S•ept.63; Miller, War P/an Ocunge, 272-73; Graybar, *Scapegoat." 13-14; "RADMKimmel," Reynolds. Famous Admirols, 175-76.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 395fleet effectiveness resulted. Such deleterious budget restrictionsapparently were not lost on Klmmel. His duties as Naval GunFactory director and destroyer division commander depended oncongressional appropriations. But governmental parsimony didnot paralyze him. Admiral W.R. Smedberg, Ill, a Kimmel subordinatein 1928, later recalled the slxteen-hour days and restrictionsto shipboard duty Klmmel imposed. He was determined.according to Smedberg, that "ships under his command be asready as he could make them." regardless of budgetary limitations.His men respected Kimmel, "understood his rationale,"and "thought he was an S.O.B. of the first order." Equallyinfluential on Kimmel's behavior were his terms as war collegestudent and staffer in the Policy and Liaison Division ofthe CNO'soffice. Evidently, neither taught him the interconnectlons ofmilitary affairs and politics. Instead. they added personal resonancesto the generally cloudy relation of the decade's politicalexigencies and the navy's ongoing mission. In later years, Klmmelcontinued to push his men and perceived mission in the absenceof adequate funding. Also, he apparently lacked a clear understandingof the connection between national policy and militarymatters. He failed to discern an imminent peril in the diplomaticconvolutions of 1941. 32During the 1930s Kimmel hlmself served as Navy BudgetOfficer (1935-1938), in addition to more battleship and somecruiser duty. As Budget Officer, he worked closely with congressmen,cabinet officers, and navy financial personnel. Such exposureto the civilian, bureaucratic side of the naval world generallyproduced officers with a smooth shrewdness who were adept atmaneuvering the seas of bureaucracy without drawing publicattention to internal divisions. Admiral RichardSon had servedin the judge advocate general's office and until 1940 had enjoyedsteady success.- Admiral William D. Leahy, renowned as a savvyplayer, had long served in upper bureaucratic levels. So had CNOStark. And so had Klmmel. Significantly, Klmmel's fitness re-32 *RADM Kimmel'; Reynolds. Famous Admituls. 175-76; Wheeler. Preludeto Pearl Harbor. 107-8.

396 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [Julyports for these years cite, in addition to the usual virtues ofdiligence and leadership, his capacity for independent thought. 33Thus. Kimmel entered his job as CinCPAC with a dangerousmix of institutional heritage and personal experience. At atime of increasingly complex, amorphous, and potentially explosivedevelopments, he was an example of naval convention:narrowly educated and trained, wedded to aggressive battleshipstrategy, habituated to the informal evolution of naval war plans,and practiced in the wriggling and rationalization of the militarybureaucrat.Although the new strategy for worldwide conflict, Rainbow-5,dictated a defensive role for the navy in the Pacific. Kimmelsteadily thought in terms of offense. And, in the tradition ofstrategic debate and his own inclination for independent thinking,he tried to advance his own thesis. <strong>The</strong> U.S. Navy's war plan,WPL-46, and the Pacific Fleet's own war plans, WPPac-46,' hadoutlined only raids on the Marshall Islands within six months ofthe war's beginning, (Offensive moves toward the Carolines, amore distant Japanese possession, existed in the plans but wereconsidered impractical by the Hawaiian command.) Kimmel'sfleet had been reduced by the transfer of numerous ships to theAtlantic. and his fleet's amphibious capability was extremelydoubtful. But the strikes against the Marshalls retained significance,at least on paper• Supposedly, these strikes would divertJapanese efforts and disrupt their lines of communication tosoutheast Asia. the projected seat of conflict. But, even as lateas 26 November 1941, Kimmel sought appmval of an immediateattack in case of war. At that time he informed Stark that thePacific Fleet's carriers would hit the Marshalls a mere two weeksafter war began. And this raid might have been the least ofKimmel's ambitions. His hopes to ambush the enemy near WakeIsland are well known. Indeed, he maintained that a well-defendedWake Island "would serve as bait to catch detachments•.. of the Japanese fleet." Here the conventional doctrine of the33 Heinrlchs. "Role of U.S. Navy." 200-201; Graybar. "Scapegoat." 14-15;"RADM Kimmel."

1994] Admiral Kimmel 397decisive surface battle loomed large. On 18 April 1941 Kimmeltold Stark that "extended operations of [Japanese] naval force[s]in the area where we might be able to get at them [would offer]an opportunity to get at naval forces with naval forces." Accordingly,considerable efforts had been expended to increase Wake'sdefences before the Pearl Harbor attack.34 And the only offensiveever begun under Kimmel's authority was directed against Wake.Speculation even exists that Kimmel and his aggressive war plansofficer. Captain Charles H. "Soc" McMorris, harbored secret plansto fight the war's decisive engagement near Wake with battleshipssoon after war began. 35 Grandiose as such a vision appears inhindsight, Kimmel was not its sole inspiration.Injunctions for aggressive action had bombarded Kimmelsince the early months of his tenure as CinCPAC. AdmiralThomas C. Hart, commander in chief of the Asiatic fleet, hadpleaded for help to stave off Japan's threat to the Philippines.Captain W. W. "Savvy" Cooke, Kimmel's chief of staff, told himAmerican aggressiveness would undermine Japanese morale.Consistent with this belligerent tone, Kimmel vowed "to damageJapan as situations present themselves or can be created."Finally, when Kimmel asked Stark whether "bold aggressiveaction" should be his method, Kimmel received the reply "concurredin." Moreover, only a few days after he became CincPAC,Kimmel was told by Stark that even "severe losses" should berisked by the Pacific Fleet ff the gains appeared commensurate.In addition, Stark's message contained a broad admonitionequally dangerous to Kimmel's misunderstanding of the situation."A properly vigorous offensive," Stark told Kimmel, couldprovide opportunities to strike "an important section" of enemyships. 36 Perhaps Stark intended only to salve Kimmel's ego by34 PHA 26: 459-60; Love, History of U.S. Navy. I : 655-56; PHA 22: 397-98;453-55; 6: 2572; Morison, Rising Sun in the Pacific, 226-27.35 William D. McPail, "<strong>The</strong> Development and Defense of Wake Island,1934-1941." Pro/ogue 23 (Winter 1991}: 361439; Lloyd J. Graybar, "AmericanPacific Strategy After Pearl Harbor:. <strong>The</strong> ReliefofWake Island." Pro/ogue, 12 (Fall1980): 134-50; See Miller. War Plan Orange. esp, Ch. 25.36 CinCAF to CinCUS, 18 January 1941; CinCUS to CNO. WPL•41. 28

398 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [Julyputting a bellicose face on the relatively insignificant MarshaUsinitiative. But Kimmel's somewhat ambiguous instructions - takelimited action but be aggressive and risk much if conditionswarrant - did nothing to alter the inclinations of professionalnaval officers to operate on the basis of the aggressive War PlanOrange.Instead, the statements of Stark, Hart, and Cooke onlyreinforced traditional impulses. Ominously, the ambiguity offleet mission statements also led to diverse interpretations amongother influential officers. For example, Vice Admiral William S.Pye, the Pacific Fleet's chief battleship commander, later claimedthat the mission was "rather indefinite" but that the fleet was,nevertheless, to start offensive operations immediately after warbegan. And Director of War Plans Captain Richard Kelly Turnerof the CNO's oiT1ce contended that the fleet mission was basicallydefensive except for the diversionary MarshaUs raid. a7 Becauseof ambiguity and disagreement over mission, the fires of ambitionfor offensive action continued to burn brightly in Kimmel and inother commanders. But the glare of such flames was but onefactor which obscured Kimmel's perspective.<strong>The</strong> frequent and chummy messages between Kimmel andStark further misled the new CinCPAC. In January 1941, Starkwrote to "Dear Mustapha" [Stark's nickname for Kimmel] concerningthe proper focus of an officer's attention. In this missiveStark criticized a contemporary who concentrated on an upcomingassignment and tended to neglect his present, day-to-dayresponsibilities. Stark wrote. "It sort of hits me with a thud whenpeople are planning ahead and looking for something in advancerather than giving aU they can to the job at hand." In the subtlerhetoric of command politics, did this mean that Kimmel shouldJanuary 1941; CNO-CinCUS-CinCAF, WPL-44 Correspondence, January-February 1941; CNO to CinCUS, lO February 1941; Cooke Memo to CinCUS. 7April 1941, Cooke Papers. Naval <strong>Historical</strong> Center, Washington, D.C.; CinCUS toCNO, Plan Dog, 25 January 1941, all in MiNer, War Plan Orange, 286-87, 293.37 PHA26: 157, Iso, 459-60.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 399emphasize everyday training of the fleet for combat rather thanundertake programs like long-range air reconnaissance? Or didit mean that Kimmel should patrol extensively and thus protectPearl Harbor rather than ready the fleet for a future war plan?Or did it mean that the often chatty and deceptively cheery Starkwas simply engaging in household gossip?38Added to this, another ambiguity from Stark, were theofficial voices outside Pearl Harbor.<strong>The</strong>se seemed to reinforcethe idea that security from threats to Pearl Harbor or the fleetwere not prominent concerns.In January. army intelligencediscounted rumors of a Japanese plan to attack Pearl Harbor.On 1February Stark gave Kimmel another reason to feel secure:Intelligence<strong>The</strong> Division of Naval Intelligence places no credence in theserumors. Purthermore, based on known data regarding thepresent disposition and employment of Japan's naval and airforces, no move against Pear] Harbor appears imminent orplanned in the foreseeable future.(<strong>The</strong>n-Commander Arthur H. McCollum, Office of Navalstaffer who drafted the message for Stark, latermaintained "foreseeable future" meant no longer than a month.)Nevertheless, the rumor had contained no time frame at all.Consequently. Kimmel - and Army Intelligence - doubted itsreliability. 39Another disastrous conclusion by Kimmel wasalso apparentlyderived from a message from Stark. A 11 November1940 raid on the Italian fleet at Taranto by British torpedo aircraftsank three battleships.Subsequently. U.S. concern over suchattacks increased. On 15 February 1941, Stark assured Kimmelthat Pearl Harbor's shallowness - the average was thirty feet, fortyfeet in the channel - limited the danger.Referring to Americantorpedoes, Stark believed the minimum required depth of six•yfourfeet (150 feet was preferred) obviated the need for anti-tor-38 PHAS: 2146.39 Slackman, Target." Pearl Harbor, 25; prange, At Dawn We Slept. 33-34;PHA 2: 815; 14: 1044; Rear Admiral Arthur H. McCollum Interviews, 2 vols.,December 1970 and March 1971, United States Naval Institute Oral HistoryCoUeclJon, Annapolis, Maryland, {copy}, I: 429-30.

400 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [Julypedo nets, the U.S. versions of which were not practical forcongested areas like Pearl Harbor. Stark emphasized that Taranto'sdepth was eighty-four to ninety feet. 4° In practical effectStark and the navy were reasoning in a closed circle; Americantorpedoes were not suited to attack a fleet like that at PearlHarbor. <strong>The</strong>refore, the threat of such an attack could safely beconsidered minor. Stark did not report that the British torpedoeshad gone under the Italian nets (which extended only to the ships'maximum draft) and exploded beneath the hulls. 41 <strong>The</strong> possibilitythat attackers might similarly operate outside conventionallimits - that torpedoes might function inside Pearl Harbor - seemsnot to have been taken seriously until after the attack. (Indeed,Admiral Richardson in November 1940 had assured Stark thatPearl Harbor was too shallow for torpedoes, and Admiral CharlesC. Bloch, commandant of the Fourteenth Naval District [PearlHarbor], had similarly dismissed torpedo attack as improbable.)Kimmel, too, locked himself into conventional thought, He considered"a massed submarine attack" on the fleet at sea "as aprobability. • But the unorthodox scenario of aerial torpedo andbomb attack inside Pearl Harbor seems to have been excludedfrom his calculations. Kimmel said the command "considered anair attack on Pearl Harbor a remote possibility. "42Air attack had been written about, talked about, andworried about for years - as a theory. One of the most thoroughstudies of this contingency came on 31 March 1941. This "JointEstimate" of the army-navy response to air attack on the fleet oron Oahu painted a grim but accurate picture. Rear AdmiralPatrick N.L. Bellinger, whose principal commands included theNaval Base Defense Force and Patrol Wing Two, and MajorGeneral Frederick L. Martin, commander of the army's HawaiianAir Force, were exhaustive in their analysis. <strong>The</strong> most fateful oftheir conclusions was that a 360° aircraft search pattern around40 PHA 26: 36; 6: 2508-9.41 Thomas Parrish, ed., <strong>The</strong> Simon and Schuster Encyclopedia of World War//(New York. 1970). 621: B. H. Liddell Hart, History of the Second World War (NewYork, 1970). 213-14.42 PHA 1: 275, 278-79; 6: 2577; 22: 325.

1994] Admirol Kimmel 401Oahu could be maintained only for a "very short period" beforemechanical problems would drastically reduce the number ofeffective planes.With chilling precision the report asserted:In a dawn attack there is a high probability that it could bedelivered as a complete surprise in spite of any air patrols wemight be using and that it might find us in a condition ofreadiness under which pursuit would be slow to start... 43For adequate reconnaissance Bellinger and Martin recommended180 more B-17s than they had. Significantly, this numberexceeded the total then available on the U.S. mainland.Such groups of planes were not, of course, forthcoming.<strong>The</strong>refore. Bellinger -with the approval of Kimmel and Bloch-concentrated on expansion training. This emphasis on preparingflight crews for detachment to the mainland as cadres for newsquadrons was a double burden for the Hawaiian command.First, it anticipated imminent U.S. involvement in a massive war;necessity bred haste•reconnaissance. 44Second. its large scope disrupted routineHard training and incessant drill extended to the rest ofthe fleet as well. Rear Admiral Harold F. Pullen, then commanderof the destroyer Reid, later recalled 1941 as "one of the mostconcentrated periods of training" in his career•never went ashore." he remembered."We practicallyFleet gunnery officer RearAdmiral William A. Kitts, Ill, later rated "the general efficiency ofships and gunnery" on 7 December 1941, as "the highest state..• ever reached in... peace in the history of the Fleet." All airgroups - fighters as well as Bellinger's patrol planes - practicedrelentlessly, and twelve trained flight crews transferred to themainland each month. Moreover. all ships" crews partially riggedtheir vessels for combat.And large numbers of newly trainedsurface personnel rotated stateside, only to be replaced by morerecruits. But Kimmel's schedules were predictable. Major taskforces entered and departed Pearl Harbor with a regularity knownto the Japanese. Many ofthe largest vessels were riding at anchor43 PHA 22:349-5344 PHA 32: 494.

402 <strong>The</strong> P//son Club History Quarterly [Julyeach weekend.In November, for reasons which remain unclear,the rotation of divisions in and out of the anchorage stopped.Eighty-six ships were there on 7 December. 4S<strong>The</strong> risks of air or submarine attacks to this large forcewere generally recognized and accepted as part of the job.Butprofessionals like Martin and Bellinger - as well as Kimmel andStark - figured the probability of carrier-based air attack into theircalculations.If such an attack ever arrived over Pearl Harbor, itlikely would succeed. Martin. Bellinger, and numerous fleetexercises had established that.But the technical difficulties ofmounting a carrier strike from Japan to the central Pacific -mechanical attrition and risks of detection -made such a moveseem irrational to the professionals in Hawaii. Captain McMorris,Kimmel's war plans officer, and Commander Joseph J. Rochefort,the chief of the naval district's communications intelligence unit,and many other well-informed, responsible officers later testifiedthat they too believed a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor wasunlikely. 46Captain J. B. Earle, chief of staff for the commandantof the Fourteenth Naval District, put it succinctly:"[W]e consideredthe point, but we always felt 'it couldn't happen here.'" Asin the command's flawed reasoning about torpedo threats, hereagain ambiguity and uncertainty let wishfulness and dependenceon probability prevail. 47Shared loyalties, social ties, and questionableassumptions also fostered miscalculation.Kimmel andhis officers thus focused narrowly on comfortable, traditionalconcepts like instant offensive, decisive surface battle, and rigoroustraining.As Rear Admiral H. Fairfax Leafy, commander ofthe fleet's cruisers, later testified, "I'he prevalent opinion in theFleet among the high command . . . was that the situationpermitted of emphas•ing training at the expense of security."<strong>The</strong> "contingency" of Japanese attack was "remote . . . and [the]45 Prange, pearl Harbor: Verdict of History, 467, 471; Halsey and Bryan.Admiral Halsey's Story. 71-72; Prange, At Dawn We Slept, 76. 336. 390. 731-33.Morison. Rising Sun in the Pacific, 86; Love. History of U.S. Navy. 1 : 664-65.46 PHA 6: 2639; 22: 457; 26: 248,207.47 PHA 26: 412; Richard K. Betts, Suryrlse Attack: Lessons for DefensivePtanning [Washington. 1982), 103.

1994] Admiral Ktmmel 403<strong>The</strong> Price of Miscalculation: Battleship Row, 7 December 1941Kentucky <strong>Historical</strong> Societyfeeling strongly existed that the Fleet would have adequate warningof any chance of air attack. .48On 13 June 1941, Stark wrote to the commandants of allnaval districts, including Bloch at Pearl Harbor. Recent tests haddemonstrated, Stark explained, that U.S. and British aerial torpedoescould indeed operate at depths less than seventy-five feet.<strong>The</strong>refore, "it cannot be assumed that any capital ship.., is safewhen at anchor from this type of attack.... [Furthermore,] nominimum depth of water in which Naval vessels may be anchoredcan arbitrarily be assumed to provide safety from torpedo planeattack.... " Unfortunately, Stark added a loophole through whichKimmel, Bloch, and associates leaped. He wrote that an attack48 Irving L. Janis, Victims of Gmupthlnk: A Psychological Study of Fore@nPolicy Decisions and P'•scoes (Boston, 1972}, 81 •82; PHA 26: 398-99. See alsoLeslie A. Zebrovitz, Soc•d Percept/on, (Mapping Social Psycholo•, Series; Pacific, Orove,Calff., 1990).

v,::•J•'lili6:-•[l,,TIL, i!' ,:•::•:I, :llil;•[ Ih, 'I,• I 4,•'q,ilJ,:j ]]L•'I',' i•:l,:',:lll;!!•' •,iF[i:;I]•!! iI!i ¸ ;ilnv ch;]il;:,:l ¸ i;,J ;iliF ;t!l:,:l [•; •I•,[il,]l ]•!,,]ii]•t• ii'•i{] SIi]r]• •:•r,:•i• "1•,1h,' i,iii:li•;i::{]•l]il•i i,I ;illi,,ii,•ii•i]>:•:l¸j•t•,!]i• ]lil:ii::•]!;],,• ]i•il !',:•l[i]] Irt)l• Ii;!•,;:,lll I• !•:]>,]::ii:!iiJ :': •!1• le • i, i i ] l(J •] iq: i,: q 'I] [ll]i'[ ; i 1 i, i I i i i, i :ll i :•, lt'• >i, I i i; •1] i !•i • q,] i I ,• I i• i• LI!',L I]i:]•t'l/!•,: "J/ •:]Ill, I>i, :!¢•:•,ll]]:t,l:ltii;•: L•I],,, ¸ •'•i!J! if •,]::ii:, i•-,ii!, ¸,,•!]•:'li ;iI ;•l],:l:ii,! ¸ Ir•;,]ii I!•i• Ii•']ll, ,::! •ll:ii,:k . Ii :F:•]I•Ill],::,]•'} li,::,I]l::]]J]l]•!::!]l ,:]!•il[ll l],l •,;J{eF ill i,•]l],: il •":;l•r;I] •':S!•l i•'i ]11•1', ' I•le ,!l]l•'L]I:,[':,::iI:•l]:i ;ill]•lil:l•iFi]'• ¸ Ilt' ;•-•;ll]]]•'d II: ]>3::"iJ•!i': '¸ •h'l• I]'/i[I] I::,•pl'(]l] il!;l:i:,l ¸;•1I,•, 1-,• .... " [•lii!,::]'l :]];!:•']•, r, •t;]:r•;i•l,•t'll;i i::,,::i:,i:]::,i: ¸]ii],:l ,;:L!:: ',',]I;,: i]•li]•!]il•,], ]•]•)(!], ;i::!l:l. ;l•!•l,,: :;ii,:,•, ]¸:¸;¸Lip¸:¸¸:¸]¸ ii1• •::•:,1• ¸ I]]•t ;i:: •]tlii,: k

404 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [Julylaunched "in relatively deep water (ten fathoms or more) is muchmore likely.... "Kimmel and his staff reviewed the communication,and, as Kimmel later said, they all "considered the torpedodanger negligible after reading this letter."After all, Kimmeladded, the message nowhere specified that torpedoes could operatein less than ten fathoms of water; Pearl Harbor's averagedepth was five fathoms, or thirty feet. 49Given a broad policydirective, Kimmel and company assumed away the specific andimprobable.In early September, Stark inadvertently complicated mattersfurther at the formal approval of WPPac-46.This war planfor the Pacific Fleet, in place in Hawaii since July, encouragedKimmel's inclinations for an instant offensive in case of war.Unfortunately. it also allowed him to make another grave miscalculation.<strong>The</strong> plan provided that as many patrol planes aspossible be established on Wake, Midway. and Johnston islandsby the operation's fifth day.role<strong>The</strong> enshrinement of the importantof the planes in the plan led Kimmel to regard them as"indispensable features of the entire operation." In the followingmonths, Kimmel and other commanders consistently valued theplanes too highly to wear them out in peacetime searches, s° <strong>The</strong>ywere too precious to use even in dangerous times when war cloudswere clearly gathering.Kimmel was indeed aware of such ominous developmentson the international scene.His "Pacific Fleet Confidential LetterNo. 2CL-41 (Revisedl" of 14 October outlined fleet security measuresagainst sabotage, submarines, and surprise attack before adeclaration of war.Yet because "2CL" supposedly formalizednavy-army security responsibilities, Kimmel purposely remainedignorant of army alert procedures and the capabilities and limitationsof the army-operated Alr Warning System (radar). stKim-49 PHA 6: 2509. 2592-93. In Pearl Harbor:. Verdict of History (clothboundedition. 1986). Gordon W. Prange quotes Stark's message. 424, but omits thequalifying phrase Stark included abou t a more likely attack occu rrlng in "relativelydeep water (I0 fathoms or more)." Prange's account pictures Kimmel asmisrepresenting the facts in his later testimony concerning Stark's dispatch.50 PHA 6: 2529-30. 2534-35; 22: 487.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 405mel later charged that critical informaUon regarding the Japanesethreat was withheld by Washington. He clalmed that the absenceof this information precluded adequate warning. "2CL" indicates.however, awareness of peril from the world outside Pearl Harbor.And the numerous alerts and messages from Washington addedto Kimmel's store of data.Fumbling and factionalism withinStark's office in Washington did indeed impede and distort informationthe Hawaiian command needed, especially regardingKimmel's accessibility to MAGIC (decrypts ofJapanese diplomaticdata}. 52But Kimmel had many indications that the affairs of1941 exceeded the danger of peacetime routine. More warningscame in November.A24 November communication warned of a surpriseJapanese attack on the Philippines or Guam.Before the next,and famous, message, negotiations were broken off; a Japaneseconvoy was sighted off Formosa. <strong>The</strong> next three communicationsto Kimmel were perhaps also sent with more gravity than usual,but they were received with complacency.message, the controversial "war warning." read:Stark's 27 NovemberThis dispatch is to be considered a war warning. Negotiationswith Japan loolcing toward stabilization of conditions in thePacific have ceased and an aggressive move by Japan isexpected within the next few days. <strong>The</strong> number and equipmentof Japanese troops and the organization of naval task forcesindicate an amphibious expedition against the Phihppines.Thal, or K• Peninsula. [isthmus linking Thailand and Malay51 PHA 22: 340-45; Morison, R/sing Sun in the Pac/f/c, 134; Prange. Pear/Harbor: Verdict of History, xxix; PHA 6: 2582-84. 2586. For the byzantine linesof communication between army and navy officers at pearl Harbor. see RobertaWohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision (Stanford, Calif., 1962), 38.52 McCollum, "Unheeded Warnings," in stJnweU, ed., Air Raid: Pearl Harbor,85; pHA 4: 3388; George C. Dyer, <strong>The</strong> Amphibians Came to Conquer:. <strong>The</strong> Story ofAdmiral Richmond Kelly Turner (2 vols.; Washington, 1972), I: 187, 189-90,193-95; Rear Admiral Edwin T. Layton, *Admiral Kimmel Deserved a Better Fate,"in StiUwelI. ed., Air RalcL. Pearl Harbor. 280; Rear Admiral Edwin T. LaytonInterview. No. I. May 1970, United States Navy Institute Oral HistoW Collection,Annapolis, Maryland [copy), 47-48, 53, 68-69, 71-72, 76-77. 80. 82; Prange, AtDawn We Slept, 87-88 and pear[ Harbor:. Verdict of History, 237; S[ackman,Target: Pearl Harbor, 27. See also Husband E. Kimmel, Admb'a/Kirnmel's Story,esp. Ch. 4. For the best analysis of Pearl Harbor and intelligence communicatlons,see Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor:. Warning and DecLston. esp. Chs. 2 and 3.

406 <strong>The</strong> FIlson Club History Quarterly [julyPeninsula] or possibly Borneo. Execute an appropriate defensivedeployment preparatory to carrying out the tasks assignedin WPL-46. Inform District and Army authorlt•es. A similarwarning is being sent by War Department...53But other dispatches fmm Washington had reached Kimmelon 27 November. Two messages, sent 26 November, informedhim that the army had agreed to send infantryreinforcements and twenty-flve of Oahu's planes each to Wakeand Midway. (<strong>The</strong>se moves were in addition to already scheduledtransit of army bombers to the Philippines.) Kimmel interpretedthe transfer of half of Oahu's air-defense planes as an indicationWashington did not consider an air attack on Hawaii, as he said.either "imminent or probable." Since aircraft carriers, majorcomponents of the fleet, would have to deliver the planes, theirprojected absence from Pearl Harbor evidently led Klmmel toreinforce his basic belief that no immediate threat to his fleet andbase existed. Consequently, he devalued the "war warning" andmade only a token response. Patrol planes were thus ordered toleave Midway on 1 December and proceed, scouting along theway, to Wake. <strong>The</strong>re they would search a complete arc aroundthe island. On 30 November a patrol squadron had flown fmmPearl Harbor to Midway and made a similar search. <strong>The</strong> shortrangeplanes of the Enterpr/se, on the way since 28 November todeliver fighters to Wake, made reconnaissance flights of dubioususefulness. Those of the Le.x•gtor• which on 5 December leftPearl Harbor caiTying scout bombers to Midway, did likewise.<strong>The</strong> sector north and northwest of Oahu was left uncovered.Generally acknowledged, according to Rear Admiral Bellinger(head of reconnaissance squadrons), as "the most vital" areabecause of its prevailing north winds, this was the region fleetexercises had shown the best for air attack on Oahu.54 (<strong>The</strong> northwas the sector from which the Japanese attack eventually came.)Clearly, Kimmel perceived no threat. More importantly, he apparentlysaw no reason to risk more patrol planes. Otherwise,53 PHA 14:140654 PHA 8:34S3

1994] Admiral Kinwlel 407the northwest sector would have been searched. As Kimmel latersaid, "In these circumstances . . . no responsible man in myposition would consider the 'war warning' message was intendedto suggest the likelihood of attack in the Hawaii area.'S•Thus Kirnmel's actions after receipt of the "war warning"indicate that he perceived Stark's message as merely a cautionarynote. He and his staff considered it a reminder not to antagonizethe Japanese with any threatening deployment which mightimperil the negotiations. Other senior commanders concurred. 56After the late November warnings, Kimmel apparently valuedpress reports more than earlier, official communications.Accountsof the resumption of U.S.-Japanese negotiations in Washingtonand the absence of what Kimmel called "authoritative"word from the military *suggestedwhich had stimulated the warning messages.a lessening" of the danger(Kimmel was notinformed that American authorities knew, from decoded Japanesediplomatic traffic, that the continued talks were a ruse.) s7On 29 November Washington sent a message to Kimmelwhich, he recalled, included the admonition to "undertake nooffensive action until Japan committed the first overt act." Thiswas how Kimmel and McMorris had interpreted the dispatch of27 November. But a portion of the latest signal did not confirmKimmel's earlier, easy acceptance of calming reports by the press.Kimmel nevertheless remained apparently unmoved by the NavyDepartment's estimation that "[n]egotiations with Japan appearto have terminated with only the barest possibilities of resumption.'SaFor Kimmel, the traditionally vague relation of diplomacyarid military affairs held firm. No emergency existed. No emergencymaneuvers were instituted.<strong>The</strong> routine for long-range air reconnaissance after 1December reflected a similar dissociation between Pearl Harborand emergency.Daffy patrols, Monday through Thursday, ex-55 PHA 6: 2518-20.56 PHA 6: 2630; 26: 259, 430, 205. 76.57 PHA 6: 2524.58 Zb•L

408 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [Julytended four hundred miles north and northwest of Oahu; a dailydawn patrol reached out three hundred miles. (An eight-hundred-mile,360° pattern was generally acknowledged as the requisitefor security, but material shortages made this impractical.)<strong>The</strong> projected mission to raid the Marshalls, Kimmel later explained,precluded wearing out the planes with more extensivesearches. In concurrence were Rear Admiral Bellinger and LieutenantCommander Logan Ramsey, commander and executiveofficer of Patrol Wing Two. <strong>The</strong> lack of spare parts limited theoperational effectiveness of the precious scouts to two or threeweeks. Also regarded as a more-or-less routine occurrence duringthis week was the change of call signals by the Japanese fleet.Thus the location of numerous ships, including aircraft carriers,was lost. Neither Kimmel nor his officers saw this as unusual;Japanese call signals had already changed twice since April. AsKimmel later correctly observed, the radio silence of the carriersduring this period did not necessarily mean they were engaged inwar operations. <strong>The</strong>y could have been in home waters and notsending long-range coded signals. After all, no disaster hadfollowed in previous months when the Japanese battleships andcarriers had "disappeared. "59Nevertheless, Kimmel should have reacted uncomfortablyto a Stark commentary received on 3 December. Stark wrote, "Iwon't go into the pros and cons of what the United States maydo. I will be damned if I know." He added that he "rather Iook[ed]"for a Japanese advance into southeast Asia. <strong>The</strong>refore, in general,Kimmel saw no imminent attack on his station. From theso-called "war warning" to the day of the attack, all informationreceived was in his estimation "consistent with the Japanesemovement in southeast Asia described in the dispatch of November27." Navy Department messages to Admiral Hart in thePhilippines - which Kimmel read - on 30 November and 1 Decemberindicated Japanese intentions to strike near Malaya orThailand. Indeed, Kimmel also had Hart's 6 December report of59 PHA6: 2S34-35, 2522-23.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 409a large Japanese force headed south from French Indochina. AsKimmel later commented "alI indications" of Japanese movement"confirmed the information" of the 27 November dispatch - "thatthe Japanese were on the move against Thailand or at the KraPeninsula of Southeast Asia."6° In fact, a 1 December messagefrom Washington had stated that, "Major [Japanese] capitalstrength remains in home waters as well as the greatest portionof the carriers." On 7 December aircraft and submarine contactsfailed to wam the American military. A warning message fromthe War Department arrived too late. 6] But these and othermight-have-beens of that terrible Sunday serve merely as footnotesto the elements of long-range contingencies which figuredin the events of that day.Had less restrictive limits been placed on battleship constructionin the 1920s and 1930s, would so much attention andmoney have gone to developing naval aircraft, aircraft carriers,aerial torpedoes, submarines, and cruisers? Each was by 1941a major factor in Kimmel's calculations. Had the pro-NavyRoosevelt not been president, would there have been an Americannaval presence in Hawaii considered worth attacking?.Had the European war not spurred U.S. military expansionbefore and during Kimmel's term as CinCPAC, would he haveemphasized training over security? Worse yet, increasingly profoundAmerican misunderstanding of Japan and its willingnessto fight coincided with ambiguity over Pacific Fleet mission andimpeded U.S. intelligence communication. Critical as well werethe desensitizing effects offalse alarms and the frequent, detailed,and emphatic - but ambiguous - dispatches from Stark's officeand other official sources, Too much was left to the local commander'sinterpretation, a2 If this host of troubles had not con-60 PHA 16: 2224-25; 6: 2520-21.61 See Gordon W. Prange [wlth Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon],Dec. 7, 1941: •e Day the Japanese Attacked pearl Harbor •,ew York, 1988];Walter Lord, Day of Infamy •ew York, 1957).62 Wohlstetter, p•ad Harbo¢: Warn•g and DeeLs/or4 viii. 106, 115-16.130-31. 139-52, 167,354; Betts. •urprlseAttae• 43, 134; Spector, EagleAga•st•he Sun, 99-100; Morlson. R/s•tg Sun /n the Pac•c, 127; Steve Chan, "<strong>The</strong>

410 <strong>The</strong> -•lson Club History Quarterly [Julyverged in 1941, would Kimmers perceptions have been so fuzzy?<strong>The</strong>se and numerous other contingencies over whichKimmel had little or no control informed hls year as CinCPAC.Yet, as the officer in charge of the fleet, he faced the commander'sgreatest peril. Between the bounds of heritage and contingency,amid ambiguity and confusion, Klmmel had to choose. Unfortunately,he chose the conventions ofnavy heritage, and he adheredto them with remarkable constancy. Mispereeptions and fatalchoices followed accordingly.He did not, as some critics charge, neglect his duty. Adedicated professional officer, Kimmel would follow the dictatesof duty whatever the cost. <strong>The</strong> fundamental problem lay elsewhere.In reality, he did not even hold a definition of duty relevantto the complexities of late 1941. In July of that year, he hadresponded to a false alarm by taking the "calculated" risk oflong-range, narrow-sector aerial reconnaissance for a brief period.e3 In December he saw no imminent threat, and he took nosuch gamble. Indeed. throughout his career, Kimmel hadadopted none of the more innovative, risk-taking aspects of thenavy's bold heritage. Thus, he did not accept the remarkableprogress made by 1941 in transforming aircraft and aircraftcarriers into offensive weapons. In general, Kimmel chose toembrace the comforts of orthodoxy. Like his predecessors, hejousted with peers over strategy. Stark's ineptly framed communicationswere perceived as tentative and debatable. (And Stark'straditional laissez-faire style allowed vast miscalculations at allcommand levels.) In a similarly conventional way, Kimmel devaluedthe unorthodox and the ambiguous. Air and torpedo threatswere, therefore, perceived as improbable and dismissable fromserious consideration. And, like his forebears, Kimmel judgedinternational affairs and national policy as somewhat remotefrom the navy's routine, No immediate cause for alarm was seen.<strong>The</strong> choices and assumptions in Hawaii and WashingtonIntelligence of Stupidity: Understanding Failures in St•ategte Warning,"A•n Polttkul Science Review 73 (March 1979): 171-80.63 PHA 36: 409.

1994] Admiral Kimmel 411reflected, of course, American cultural values. And Japaneseskill, luck, and resolution cannot be entirely excluded from thestory. But because of their hold on Kimmel and the U.S. Navy,and because of a willing acquiescence to their demands, in a veryreal sense orthodoxy of thought and orthodoxy of deed lost theday at Pearl Harbor.APPENDIXKentucky's Senior Naval Commanders In World War IIIn Order of Initial Commission as OfficersBLOCH, CLAUDE C.Admiral, after retirement; Rear Admiral, permanent, 1July 1931; Admiral, temporary, 2 January 1937 - 16 January1940; Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, 1938-1940; Commandant,Navy Yard, Pearl Harbor, 1940-1942; b. 12 July 1878,Woodbury, Ky.; United States Naval Academy (USNA), 1899,passed midshipman, 1899; comm. ensign, 1901; Naval WarCollege (NWC), 1930; d. 6 October 1967; bur., Arlington NationalCemetery.BLAKELY, CHARLES A.Vice Admiral, 24 June 1939; Commander, Aircraft, BattleForce and Carrier Division TWO (concurrent). 1939-1940 [CarriersYorktown and Enterpr/se]; Commandant, Eleventh NavalDistrict, San Diego, 1940-1941; b., 1 October 1879. Williamsburg,Ky.; USNA, 1903, pmd, 1903; comm. ensign, 1905;NWC, 1935; d., 12 September 1950; bur. Fort Rosecrans NationalCemetery, San Diego, Calif.<strong>KIMMEL</strong>, HUSB<strong>AND</strong> E.Rear Admiral, November 1937; Admiral, temporary, 1February - 17 December 1941; Commander, Cruisers, BattleForce and Commander, Cruiser Division NINE (concurrent),1939-1941; Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Commanderin Chief, U.S. Fleet (concurrent), 1941; Retired, i May 1942; b.

412 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Filson</strong> Club History Quarterly [July26 February 1882, Henderson. Ky.; USNA, 1904, pmd, 1904;comm. ensign, 1906; NWC, 1926; d. 14 May 1968; bur.. U.S.Naval Cemetery. Annapolis, Maryland.LEE, WILLIS A., JRRear Admiral, January 1942; Vice Admiral, 21 March1944; Director, Division of Fleet Training, 1941-1942 (fifth tourof duty in Fleet Training); Assistant C/S to Commander in Chief,U.S. Fleet, 1942; Commander. Battleship Division SIX (Wash/ngton,South Dakota) - (Guadaleanal, 14-15 November 19421; Commander,Battleships, Pacific Fleet and Commander, BattleshipDivision SIX (concurrent), 1943-1944 (Fast Battleships, FastCarrier Task Force - Gflberts, Marshalls, Marianas, PhilippineSea, Leyte Gulf): Commander, Battleship Squadron TWO, 1944-1945 (lwo Jima, Okinawal; b. 11 May 1888, Natlee, Owen County,Ky.; USNA, 1908, pmd, 1908; comm. ensign, 1910; NWC. 1929;d. 25 August 1945; bur., Arlington National Cemetery.GUNTHER, ERNEST L.Rear Admiral, 11 August 1943; CO, Carrier Wasp, 1938-1939; Flying duty, Carrier Yorktown, 1939-1941; CO, Naval AirStation, San Diego, 1941-1943; Fleet Air Command, South Pacific,1944; Flying duty and attached to Commander, Aircraft,South Pacific, 1944; Subordinate Command, Air Force, PacificFleet, 1945; b., 7 September 1887, Louisville, Ky.; USNA, 1909,pmd, 29 June 1909; comm. ensign, 1911; d., 27 March 1948.BARRETT, CHARLES D.USMC: Brigadier General, 1942; Major General, September1943; War Plans Section, Office of Chief of Naval Operations,1939-1940; Director, Plans and Policies, Headquarters. USMC,1940-1941; Assistant to Commandant. USMC. 1941-1942; CO,Third Marine Brigade, Third Marine Division (sequential), 1942-1943; commanding General, First Marine Amphibious Corps,1943; b.. 16August 1885, Henderson, Ky.; Commissioned Marinesecond lieutenant, 11 August 1909; Ecole Superier de Guerre,