Authoritarian Nostalgia in Asia - Academia Sinica

Authoritarian Nostalgia in Asia - Academia Sinica

Authoritarian Nostalgia in Asia - Academia Sinica

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

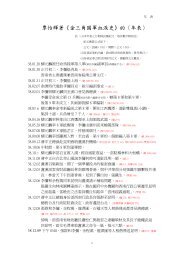

120Institute of Political Science<strong>Authoritarian</strong> <strong>Nostalgia</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>AbstractData from the first and second<strong>Asia</strong>n Barometer Surveys (ABS) canhelp us systematically to assess theextent of normative commitmentto democracy that citizens feel<strong>in</strong> Japan, South Korea, Taiwan,Mongolia, the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, andThailand. The ABS confirms that East<strong>Asia</strong>n citizens feel ambivalent aboutdemocracy, and that the region’s new democracies have seen theirpopular legitimacy stay flat or evendrop slightly. Thailand, Mongolia,and the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es each have alarge number of equivocal andconfused citizens whose <strong>in</strong>consistentpolitical orientations burden theirdemocracies with a fragile foundationof legitimacy. In Taiwan and SouthKorea, authoritarianism has graduallylost its appeal, but democracy hasnot yet lived up to their citizens’ highexpectation.Yu-Tzung Chang 1 , Yun-Han Chu* 2and Chong-M<strong>in</strong> Park 31 National Taiwan University, Taipei,Taiwan2 Institute of Political Science,<strong>Academia</strong> S<strong>in</strong>ica, Taipei, Taiwan3 Korea University, Seoul, KoreaAlthough many forces can affect a democracy’s survival chances, nodemocratic regime can stand long without legitimacy <strong>in</strong> the eyes of itsown people. What elites th<strong>in</strong>k matters, but for democracy to becomestable and effective, the bulk of the citizenry must develop a deepand resilient commitment to it. Data from the first and second <strong>Asia</strong>nBarometer Surveys (ABS) can help us systematically to assess the extentof normative commitment to democracy that citizens feel <strong>in</strong> Japan, SouthKorea, Taiwan, Mongolia, the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, and Thailand. The assessment<strong>in</strong>volves seek<strong>in</strong>g answers to the follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terrelated questions: Has thegrowth of democratic legitimacy <strong>in</strong> East <strong>Asia</strong> stagnated or even eroded?How detached are East <strong>Asia</strong>ns from authoritarian alternatives? Is popularsupport for democracy deeply rooted <strong>in</strong> a liberal-democratic politicalculture?When we began our analysis we did not expect to f<strong>in</strong>d a strong and resilientpopular base for democratic legitimacy <strong>in</strong> East <strong>Asia</strong>’s new democracies,let alone any enhancement of it over time. We knew that many East <strong>Asia</strong>ndemocracies display socioeconomic features that <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple should befriendly to the growth of democratic legitimacy (sizeable middle classes,well-educated people, and many ties to the global economy). Yet at thesame time we feared that the region’s overall geopolitical configuration,political history, and predom<strong>in</strong>ant cultural legacies would act as strongdrags on the development of robust democratic political cultures. Mostof the region’s people rema<strong>in</strong> under one form or other of authoritarianor at best semidemocratic rule. Few of the region’s former authoritarianregimes have been thoroughly discredited. Indeed, all too many peopleare wont to credit them with hav<strong>in</strong>g fostered social stability and stunn<strong>in</strong>geconomic growth. F<strong>in</strong>ally, there is the argument—proffered by such<strong>in</strong>fluential Western scholars as Lucian Pye and Samuel P. Hunt<strong>in</strong>gton—thatdom<strong>in</strong>ant East <strong>Asia</strong>n cultural traditions pose an obstacle to the acquisitionof democratic values. The ABS confirms that East <strong>Asia</strong>n citizens feel ambivalent about democracy,and that the region’s new democracies have seen their popular legitimacystay flat or even drop slightly. To measure the overall level of attachmentto democracy, we constructed a 6-po<strong>in</strong>t (0 to 5) <strong>in</strong>dex of the number ofprodemocratic responses to the five questions designed to measure “thepreferability of democracy”, “desirability of democracy” “the suitability ofdemocracy, “the efficacy of democracy”, and “ the priority of democracy”respectively. Apparently, crises of governance have taken a toll on popularcommitment to democracy, push<strong>in</strong>g down the region’s average score from3.3 around 2002 to 3.0 around 2006. Now, East <strong>Asia</strong>ns on average acceptonly three out of five possible reasons to embrace democracy. In the threeless-developed countries among our group (Mongolia, the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, andThailand), pockets of support for authoritarianism are grow<strong>in</strong>g rather thandim<strong>in</strong>ish<strong>in</strong>g. This suggests that Thailand, Mongolia, and the Philipp<strong>in</strong>eseach have a large number of equivocal and confused citizens whose<strong>in</strong>consistent political orientations burden their democracies with a fragilefoundation of legitimacy. In Taiwan and South Korea, authoritarianismhas gradually lost its appeal, but democracy has not yet lived up to theircitizens’ high expectation.

Significant Research Achievements of <strong>Academia</strong> S<strong>in</strong>icaHumanities and Social Sciences121Across East <strong>Asia</strong> the acquisition of liberal-democraticvalues has been slow and uneven. The richercountries <strong>in</strong> our group offer a sharp contrast to theirless-developed neighbors. In Japan, South Korea, andTaiwan, a great majority of citizens embrace politicalliberty, separation of powers, and rule of law. Theirmean scores were way above the region’s average. Bycontrast, Filip<strong>in</strong>os, Mongolians, and Thais gave muchmore illiberal responses, and the gap between themand Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan is widen<strong>in</strong>g.From the viewpo<strong>in</strong>t of regime legitimacy, these threeyoung democracies appear vulnerable to any wellorchestratedhostile <strong>in</strong>tervention by a strategicallypositioned antidemocratic elite.ReferencesYu-tzung Chang is associate professor of politicalscience at National Taiwan University. Yun-han Chuis Dist<strong>in</strong>guished Research Fellow of the Institute ofPolitical Science at <strong>Academia</strong> S<strong>in</strong>ica . Chong-M<strong>in</strong>Park is professor of public adm<strong>in</strong>istration at KoreaUniversity.See Larry Diamond, Develop<strong>in</strong>g Democracy: TowardConsolidation (Baltimore: Johns Hopk<strong>in</strong>s UniversityPress, 1999), 65.Lucian W. Pye, <strong>Asia</strong>n Power and Politics (Cambridge:Belknap, 1985); Samuel P. Hunt<strong>in</strong>gton, The Clash ofCivilizations and the Remak<strong>in</strong>g of World Order (NewYork: Simon and Schuster, 1996).The orig<strong>in</strong>al paper was published <strong>in</strong> “<strong>Authoritarian</strong> <strong>Nostalgia</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>”Journal of Democracy 18. 3 (2007): 66-80.