The Fur Trade - Western Michigan University

The Fur Trade - Western Michigan University

The Fur Trade - Western Michigan University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

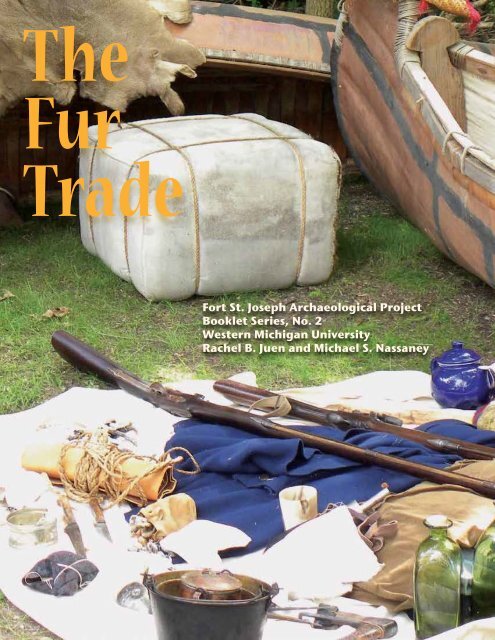

2Fort St. Joseph Archaeological ProjectIn 1998 <strong>Western</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>University</strong> archaeologists were invited to Niles,<strong>Michigan</strong> to help locate the site of Fort St. Joseph, a seventeenth and eighteenthcenturymission, garrison, and trading post complex established by the Frenchalong the St. Joseph River. With the help of documentary sources and the localcommunity, a survey team dug shovel test pits and located material evidence ofactivities associated with the fort, including gunflints, imported ceramics, glassbeads, hand-wrought nails, and iron knife blades stamped with the names ofFrench cutlers. Subsequent work identified trash deposits, fireplaces, and buildingruins, indicating that much of the fort remains undisturbed. After more than acentury in search of the site, Fort St. Joseph had been found!<strong>The</strong> site has become the focus of a community-based research project aimedat examining colonialism and the fur trade in southwest <strong>Michigan</strong>. Aninterdisciplinary team of historians, archaeologists, geographers, and geophysicists,in partnership with the City of Niles and community groups like Support theFort, Inc., are investigating the site to examine colonialism along the frontierof New France in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This is the secondissue in the Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project Booklet Series, intended tosummarize our findings and explore topics that appeal to a wider audience in aneffort to understand Fort St. Joseph in the larger historical and cultural context ofearly North America. Its focus is on telling the story of the fur trade and its role inthe relationships among the French and Native peoples.Fig. 1 Field school students discussexcavations at Fort St. Joseph.

4New France and the <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong><strong>The</strong> French encountered many different Native peoples anda landscape rich in fur-bearing animals in their explorationsof North America beginning in the sixteenth century. <strong>The</strong>first French settlements were fishing villages in coastalareas, but soon fur became a central part of New France’seconomy as the French entered into a Native trade networkwhich had operated in North America long before thearrival of Europeans. <strong>The</strong> core of French settlement grewalong the banks of the St. Lawrence River, concentratedin the towns of Montreal and Quebec. <strong>Fur</strong>ther west, NewFrance encompassed the Great Lakes region (known asthe pays d’en haut or “upper country”) and the area of theMississippi River Valley stretching down to the Gulf Coastand Louisiana.In an effort to secure the interior, establish Native alliances,and thwart British and Iroquois efforts to expand west of theAppalachians, the French established a network of tradingposts, forts, and missions in the North American interior.<strong>The</strong>se “islands” of French settlement in Native-controlledlands became the principal places of Native and Europeaninteraction and exchange in the fur trade.Some of the most important posts in the western Great Lakesregion included Fort Michilimackinac, Fort Pontchartrain atDetroit, and Fort St. Joseph.<strong>The</strong> Place of Fort St. JosephInitially established in 1691 on the St. Joseph River, near astrategic portage that linked the river and the Great Lakesbasin to the Mississippi drainage, Fort St. Joseph became thekeystone of French control of the southern Lake <strong>Michigan</strong>region. For nearly a century, Fort St. Joseph served as a hubof commercial, military, and religious activity for local NativeAmerican populations and European colonial powers insouthwest <strong>Michigan</strong>.This mission-garrison-trading post complex, which the Frenchnamed “St. Joseph” in honor of the patron saint of NewFrance, included a palisade, a commandant’s house, and afew other structures when it was first constructed. GovernorGeneral Frontenac of New France established the post in anFig. 2 Carte de la Nouvelle France by Nicolas de Fer (circa 1719)showing French claims in pink and yellow.attempt to solidify French relations with the local MiamiIndians and other Native groups to the west and north ofthe area. Frontenac hoped that the post, garrisoned by theFrench, would stimulate the fur trade in the region, and alsocheck the expansion and power of the Five Nations IroquoisConfederacy and their British allies. <strong>The</strong> fort soon supporteda commandant, 8 to 10 soldiers, a priest, an interpreter, ablacksmith, and about 15 fur traders, many of whom weremarried to Native womenwho occupied the post andwere fully integrated into thelife of the community.Fort St. Joseph was avital link in the colony’scommunications network,and played a majorrole in the exchange ofmanufactured commoditiesfor furs obtained by theNatives. By the mideighteenthcentury, itranked fourth among all ofNew France’s posts in termsof volume of furs traded.

5Fig. 3 Beaver felt hat.Fig. 6 Beaver was not the only fur-bearing animal that wasexploited in the fur trade.Fig. 4 American beaver.Fig. 5 Artist’s recreation of voyageurs with canoesloaded with trade goods or furs.Beaver and Other<strong>Fur</strong>s of the <strong>Trade</strong>Broad-brimmed beaver felt hats becamefashionable in Europe in the sixteenth century,and marked people’s social status. Beaver hadbecome extinct in western Europe due tooverhunting, and European hat makers had torely on Russian and Scandinavian beaver furuntil North American furs eventually becameavailable. Hatters wanted beaver fur as a materialfor felt making because the tiny barbs onthe soft underfur ensured that it would remainmatted when felted; thus beaver hats heldtheir shape better and wore longer than hatsmade of other materials.Beaver pelts were the mainstay of the fur tradein much of North America, but other peltrieswere also deemed desirable for variouspurposes. <strong>The</strong>se included the furs of muskrat,mink, marten, otter, fisher, wolverine, raccoon,lynx, bobcat, panther, fox, squirrel, ermine, andbuffalo, and the hides of deer, moose, elk, andcaribou. Buffalo “robes” were used to make avariety of goods including blankets, coats, andboots. Sea otter was valued for its very denseand luxurious fur used to trim expensive robesand capes, and to make hats and winter coats.Deer hides were processed into leather forbook covers, gloves, and other accessories.Whatever the animal, European traders reliedon Native peoples to capture and processthem into hides and furs. <strong>The</strong> exchange ofEuropean manufactured and imported goodsfor Native-produced furs and hides served tocement relationships that were much morethan economic in nature.

6North American Rivalries<strong>The</strong> fur trade was a multi-faceted,global phenomenon that had aformative influence on the history andcultures of peoples throughout NorthAmerica. Beginning in the sixteenthcentury, European markets stimulatedunprecedented demands for NorthAmerican furs, which arguably fueledexploration and later western expansion,leading to profound transformationsamong Natives and newcomers thatwere seminal in the North Americanexperience.Early in the sixteenth century,Basque and French fishermen inthe Newfoundland region began toexchange iron and brass items forfurs along the Eastern Seaboard. In1534, French explorer Jacques Cartierencountered Micmac Indians on theGaspé Peninsula who wanted to tradefurs for European goods. Failing to findgold or the fabled Northwest Passage,the British, Dutch, and French soonrealized that they could exploit NorthAmerica for other resources suchas timber and fur. All three nationseventually established settlements nearbodies of water that provided accessto the rich resources of the continent’sinterior: the French along the St.Lawrence River, the British along theshores of Hudson Bay, and the Dutchalong the Hudson River.<strong>The</strong> Russians followed later, as theBering expedition led to the discoveryof Alaska’s fur-bearing sea otterpopulations. Competition to obtainfurs from Native producers drovepolitical and economic relations inNorth America well into the nineteenthcentury.More than Profitsat StakeWhile the fur trade was at times aprofitable enterprise, other factorsmotivated the exchange and itsexpansion. <strong>Fur</strong>s were lightweight andeasy to transport in birchbark canoes.Beaver pelts, the trade’s mainstay,fetched high prices in Europe wherebeaver felt hats were in high demand.However, by the late 1690s the supplyof beaver began to outweigh demand.Because the French Crown guaranteedthe price of furs, the oversupply meantthat the fur trade sometimes actuallylost money. If the trade lost money, whydid the French keep it up? <strong>The</strong> traderepresented more than just the value offurs. <strong>The</strong> fur trade became an economic,military, social, and cultural partnershipbetween European and Native groups.It was the glue that bound the French totheir Native allies.Native groups engaged in trade as asocial relationship that had importantimplications. <strong>The</strong>y viewed exchanges interms of gifts, and not just as economicinteractions. Gifts created special bondsbetween societies, and reinforced socialalliances. Those who gave gifts gainedprestige, honor, and influence, and thosewho received them had an obligationto the giver. Even clearly commercialexchanges began with an exchange ofgifts which served to mark the socialbond required before one could tradeneeded commodities. After all, oneshould greet a friend with a token offriendship and one does not trade withenemies. Many French traders marriedNative women to create kinship bondsand access to trading partners.To a considerable extent, the structureof the early fur trade in northeasternNorth America arose as a product ofEuropean-Native American alliancesand the geography of tribal territories.<strong>The</strong> French allied themselves with theHurons, and with Algonquin groupsliving along the Ottawa River. This gavethe French access to the upper GreatLakes region via the Ottawa Riverroute from the St. Lawrence River toGeorgian Bay. After 1673, the Britishallied with Iroquois groups living southand east of Lake Ontario. This createdthe possibility that the British couldalso gain access to the upper GreatLakes region by traveling throughFig. 7 An engraving of the fur trade in North America.

7Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, and intoLake Huron. <strong>The</strong> alliances with NativeAmericans that the French nurtured andmaintained were crucial to French desiresto prevent the British from expandingtheir trade network into the upper GreatLakes region.Although the fur trade was not alwaysprofitable to the French, they did notwant their British rivals to control thetrade. <strong>The</strong> French, who had far fewercolonists than the British, strove to createand maintain amicable relationships withNative Americans. <strong>The</strong>se alliances gavethem an important advantage over theBritish and touched many aspects of lifein New France, from personal mattersto trade and politics. As trade networksgrew in size and importance to bothNative and European groups, it becamein the best interest of the French to aidthose with whom they traded againstenemies and competitors.<strong>The</strong> French went to great lengths tocontinue the fur trade in order tomaintain their relationships withNative allies. After the British tookcontrol of New France in 1760, theydiscontinued the policy of gift-giving,leading to resentment and hostilities thatprecipitated Native unrest in 1763.French, British, Russian, andAmerican <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong>s<strong>The</strong> North American fur trade was reallya series of various fur trades. SeveralEuropean nations exploited different furresources across the continent, interactedwith various Native groups in differentways, and competed with one another.Relations between Europeans and theNative primary harvesters ranged frombenign to brutally exploitative.<strong>The</strong> fur trade was an essential socialrelationship that bound the interestsof the French and their Native alliestogether against their enemies—the British and the Iroquois. Forthe French, who never attractedas large a settler population as theBritish, Native relations in the furtrade were vital for their survival inthe New World.Although the majority of theBritish population was confinedto the Atlantic Coast until theBritish victory in the Seven Years’War, they managed to siphon manyfurs from the interior at Albany.<strong>The</strong>y also competed directlywith the French by channelingpeltries northward to HudsonBay. <strong>The</strong> 1713 Treaty of Utrechtsuppressed French competition inthe north and left the Hudson’sBay Company in control of all ofthe posts on the Bay. However,the French then intensified theirefforts in the pays d’en haut,expanding their activities towardthe northwest.While the French controlledmuch of the trade in the St.Lawrence and Great Lakesriverine system and furtherwest, the English charteredthe Hudson’s Bay Company(HBC) in 1670, and establishedseveral posts along the shoreof the Bay where Nativegroups would travel to trade.<strong>The</strong> presence of independenttraders who traveled into theinterior eventually forced theHBC to construct inlandposts, beginning in 1774;this eventually led to westernexpansion into what wouldbecome British Columbia andWashington State. <strong>The</strong> potentialwealth of this vast inland areaspurred the establishment of therival Montreal-based North WestCompany, during the 1780s.continued on p. 8Fig. 9 Reenactors depicting British soldiers.Fig. 8 Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, a Mohawk leader,during a diplomatic visit to Europe. He stands proudlywith this fusil fin held closely by his side.

8North American RivalriesThis triggered a period of intensecompetition that ended with its mergerwith the HBC in 1821.<strong>The</strong> Russians took advantage of theeconomic value of sea otter pelts inthe Pacific. <strong>The</strong>y found a lucrativemarket in China, and by 1742 theyhad crossed the Bering Strait intoNorth America in search of furs. In1799 Tsar Paul I granted the Russian-American Company (RAC) a chartergiving it a monopoly over all Russianeconomic activities in North America.Employing Hawaiians, various NativeAlaskans, Native Californians, andCreoles (individuals of mixed Europeanand Native ancestry), the Russiansinstituted a system that involved Nativehunters directly acquiring furs for theRAC from Alaskan waters and as farsouth as California, which could besold at a considerable profit to Chinesemerchants. This expansion becamepossible when the Company contractedwith American ship captains for jointventures, and later built its own shipsthat brought Native Alaskan hunters toCalifornia waters.Americans came to realize the bountyof furs in the American West with theacquisition of the Louisiana Purchase(1803) and subsequent exploration byLewis and Clark. John Jacob Astorestablished the American <strong>Fur</strong> Companyin 1808 with the hopes of gaining amonopoly on the trade from St. Louisto the Pacific, and his company played asignificant role in westward Americanexpansion. Astor created a subsidiaryof the American <strong>Fur</strong> Company, thePacific <strong>Fur</strong> Company, which aimed tocapitalize on furs from the area west ofthe Rockies by both sea and by land.His efforts led to the establishmentof Fort Astoria at the mouth of theColumbia River, which eventuallyfailed due to uneasy relations withlocal Indian groups. Meanwhile, thedangerously successful American tradein buffalo robes, which accelerated after1812 (especially along the MissouriRiver and in the Southwest), helpeddrive the American bison toward nearextinction.A View from the PacificFort VancouverIn an effort to anchor Britain’s claims tothe Oregon Country, the HBC establishedthe headquarters of its ColumbiaDepartment at Fort Vancouver in 1825.Over the next two decades, the fortbecame the fur trade capital of thePacific Coast, with warehouses, locallyproducedgoods, and agricultural surplusesto supply fur brigades, Natives,settlers, and over 20 other Companyposts in the Department in present-dayBritish Columbia, Washington, Oregon,and Idaho.Fig. 10 This unsigned sketch of Fort Vancouver (c. 1851) depicts the north end of the village area.A rigid social hierarchy was composedof clerks and officers who occupiedbuildings within the fort’s palisade andengagés who lived in a multiethnic village of over 600 people. While some were from Europe, namely England and Scotland,many were French-Canadian, Hawaiian, Portuguese, métis, or from one of more than 30 Native American groups includingthe Iroquois, Delaware, and Cree.In 1860, soon after the site was declared to be on American soil, the Company abandoned the fort. Fires and decay haddestroyed all the structures by 1866. <strong>The</strong> National Park Service currently administers this site, where ongoing archaeologycontributes to the interpretations of the fur trade and the multiethnic population that supported it.

9Various countries sponsored the fur trade in North America at different historical moments. <strong>The</strong> French, British, Russians, andAmericans were dominant in the regions shown in Figs. 11 and 12 at the peak of their involvement.Fig. 11 North American French and British fur trades, 1750s.Fig. 12 North American British, American, and Russian furtrades, 1820s-30s.Fort RossRussian exploration along the California coast led to theestablishment of Ross Colony in 1812, near the mouth of theRussian River just north of San Francisco Bay. This settlement,which has been investigated archaeologically, was intendedto grow wheat and other crops to sustain Russian outpostsin Alaska, hunt marine mammals, and trade with SpanishCalifornia.<strong>The</strong> Russians built redwood structures and a wooden palisadewith two blockhouses on the northwest and southeastcorners. Buildings included the manager’s house, the clerks’quarters, artisans’ workshops, Russian officials’ barracks, and achapel. A number of these buildings have been reconstructedand are maintained and interpreted as part of the Fort RossState Historic Park.Many of the Company’s Russian, Creole (people of mixed Russianand indigenous ancestry), and Native Alaskan men mar-for the first manager.Fig. 13 <strong>The</strong> reconstructed Kuskov House at Fort Ross served as headquartersried or formed relationships with Native Californian womenand established interethnic households located immediatelyoutside of the stockade. <strong>The</strong>se unions, although informal and often transitory,led to unique cultural exchanges. Various neighborhoods reflect these populations’negotiation and maintenance of ethnic identity. Native Alaskans formedtheir settlements on bluffs overlooking the ocean, following their tradition. FortRoss functioned as a successful multicultural settlement for nearly 30 years.By the late 1830s, sea otters had been overhunted, and the HBC at Fort Vancouverbegan supplying the Russians with agricultural provisions for their northPacific settlements.Fig. 14 Native Alaskans hunting sea otters withspears in baidarkas.

10How the <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> WorkedHistorians have documented the diversity of ways in whichthe fur trade worked. <strong>The</strong> motivations for participating in thetrade, the goods exchanged, and the organization of labor tocollect and process furs differed among the participants overtime and space.Government RegulationIn New France, the French Crown tried to use fur trademonopolies to limit competition and stabilize prices. <strong>Trade</strong>rscould legally sell their furs only to the monopoly, but themonopoly had to buy furs at a fixed price regardless of marketvalue. Even so, supply and demand still affected the prices forgoods. Over time, the monopoly changed hands. Sometimesthe Crown controlled it, while at other times companies ofFrench merchants paid the Crown for the right to the trade. Atyet other times post commanders were given the right to tradeat a particular post as part of their pay, and they could lease itout to others for a fee.French officials also created a licensing system in 1681 toregulate the number of men leaving the colony to work in thefur trade and to restrict the supply of furs. <strong>The</strong> Crown issued alimited number of congés (permits) each year. <strong>The</strong> sale of congéshelped support the poor, but the system failed to prevent menfrom trading furs illegally. Independent fur traders, or coureursde bois (literally “runners of the woods”), traded directly withNatives without a license. Threats of fines or prison had littleeffect. Coureurs de bois continued to operate illegally, smugglingfurs into Montreal or supplying the British with furs at Albany.From Montreal to the West:<strong>The</strong> Flow of <strong>Trade</strong>At the beginnings of the fur trade in North America, Nativesbrought their furs and hides to trade with Europeans along thecoast within sight of European ships. As the French expandedinto the St. Lawrence River Valley, the sites of exchange movedwith them. <strong>The</strong>y sent men out to Native villages to learn theirlanguage and customs, and to persuade them to bring their fursto French settlements. Montreal became the central locationof exchange. Montreal’s trade fairs peaked each summer in the1650s and 1660s when hundreds of Natives came in birchbarkcanoes loaded with furs, ready to trade for European goods andto renew alliances with the French. <strong>The</strong>y often traveled in largeconvoys to defend against the danger of Iroquois attacks.After peace with the Iroquois in 1666, the main sites ofexchange shifted westward to forts, trading posts, Nativevillages, and hunting camps. Throughout the 1670s and1680s, Montreal’s trade fairs dwindled as voyageurs (hired furtraders) and illegal coureurs de bois increased their range fartherFig. 15 Commitment made by Pierre Papillon called Périgny,of Batiscan, to De Croisil and Jean-Baptiste Lecouste,to go to Michilimakinac.inland. However, Montreal remained the fur trade’s base formerchants, supplies, and labor.Merchants in Montreal who held a license obtained Europeantrade goods and hired voyageurs, who contracted to take thesegoods west to exchange them with Native groups for furs.When the voyageurs returned to Montreal, the merchants soldthe furs to the monopoly, which then shipped them to France.As furs were depleted in the Great Lakes region, French,British, and later American fur traders expanded their rangeever westward. <strong>The</strong> grand rendezvous of mountain men of the1840s and 1850s American West have left a vivid impressionon the modern imagination of the fur trade era. <strong>The</strong>se massiveget-togethers were the social event of the year for fur traderswho ranged in search of furs, living relatively isolated livesduring the rest of the year. <strong>The</strong>y brought their furs in tosell, bought provisions, and renewed their supplies of tradegoods for the upcoming year. A carnival-like sense of festivitypervaded the affair, and often traders were accused of drinking,gambling, and spending to excess, to compensate for theirrugged and often isolated life during the rest of the year.

11“<strong>The</strong> Indians who live at a greater distance, never come to Canada at all; and,lest they should bring their goods to the English as the English go to them, theFrench are obliged to undertake journies and purchase the Indian goods inthe country of the Indians. This trade is chiefly carried on at Montreal, and agreat number of young and old men every year, undertake long and troublesomevoyages for that purpose, carrying with them such goods as they knowthe Indians like, and are in want of. It is not necessary to take money on sucha journey, as the Indians do not value it; and indeed I think the French, who goon these journies, scarce ever take a sol or penny with them.”— Peter Kalm, 1749 (Forster 1771:269-271)Fig. 16 A mouth harp[left] and bone gamingpieces recovered fromFort St. Joseph.Fig. 18 A nineteenth-century Hudson BayCompany trading post.Fig. 16 Reenactor depicting a voyageur on the St. Joseph River.Fig. 17 Reenactor depicting a voyageur on the St. Joseph River.

12<strong>Trade</strong> Routes and Transportationmaps intended for navigation. Instead, theyrelied on experienced travelers, or hired Nativeguides to pass along knowledge of routes. In time,routes, portages, and camp sites became commonknowledge.Birchbark CanoesWater transportation was essential in the fur tradethroughout North America. In New France, themost commonly used vessel was the birchbarkcanoe.Fig. 19 <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> Routes, 1755.Getting <strong>The</strong>reNative Americans and fur traders traveled over both waterand land in search of furs and hides, but they much preferredwater transportation to land routes. Lakes and rivers were thefur trade’s highways. Canoes hauled far more weight fasterand easier than a man or horse could carry.Two main water routes connected Montreal with the paysd’en haut. <strong>The</strong> first ran up the Ottawa River, west along theMattawa River, across Lake Nipissing, and down the FrenchRiver to Georgian Bay and Lake Huron, and up to the Straitsof Mackinac between Lake Huron and Lake <strong>Michigan</strong>. Earlyin the French era, Algonquin nations controlled the OttawaRiver and sometimes charged tolls for the use of the river.<strong>The</strong> second route ascended the St. Lawrence River throughLake Ontario and Lake Erie, passing by York (Toronto),Niagara, Detroit, and through the Straits of Mackinac.Native Americans used birchbark canoes forcenturies before the arrival of Europeans. NativeAmericans had discovered that birchbark was light,waterproof, and strong. It did not shrink, so sheetsof it could be sewn together. Unlike the bark ofother trees, the grain of birch runs around the treerather than parallel to the trunk. This allowed it tobe formed into the sophisticated and subtle formsthat became the birchbark canoe.French voyageurs quickly adopted the birchbarkcanoe while Natives in turn adapted Europeantools to aid them in canoe construction. Made of readilyavailable materials, capable of carrying heavy loads, and lightenough to be carried around river obstacles such as rapidsby only one or two men, the birchbark canoe helped makepossible the unprecedented growth of the fur trade in theseventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Fort St. Joseph stood near the intersection of both land andwater routes. It was near the overland Sauk Trail, and only ashort canoe trip from Lake <strong>Michigan</strong> and its water routes tonorthern posts like Michilimackinac. <strong>The</strong> Kankakee-Illinois-Mississippi water route to Illinois and Louisiana posts layonly a few miles away to the south.Inexperienced travelers had difficulty finding their waythrough new lands and waters. <strong>The</strong>y did not have accurateFig. 20 Cartographers never intended their maps of New France to guidetravelers in the way modern road maps do today. Instead, the maps helpedclaim lands for France by showing the limits of what the French professed tohave discovered and occupied.

13Birchbark canoes held heavy loads and kept passengers andtheir goods dry. <strong>The</strong>y gave the Natives and French who usedthem an advantage over those who could not obtain thecanoes or the birchbark to build them. <strong>The</strong> British and theIroquois often had to make do with canoes made of elm bark,or with heavy dugouts, which were not nearly as serviceable.Farther north, British Hudson’s Bay Company employeeswere handicapped by lack of canoes and skilled canoe menuntil well into the nineteenth century when they developedthe wooden York boat.By 1640, large groups of Natives, mostly Algonquians, hadsettled along the St. Lawrence River at Quebec and ThreeRivers. <strong>The</strong>y began trading into the interior of the continent,and supplied voyaging and military canoes to the French andother Natives. Some Native Americans lived permanentlyat Michilimackinac, and made their living gathering andtrading supplies that the European fur traders needed,including birchbark for canoes and shelters. <strong>The</strong> Huron,Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi who eventually settled atDetroit supplied canoes to the French at Detroit and farthersouth. <strong>The</strong>y either gathered the raw materials farther northor traded for them, and made a profitable business in canoeconstruction.By 1730, heightened competition between the French andBritish—along with the Native Americans’ growing demandfor cloth garments, woven fabrics, and other merchandise—resulted in a large increase in the amount of trade goodsmoving west, necessitating larger canoes. <strong>The</strong> earlier canoes,with a maximum length of 16 feet and a carrying capacity ofabout 1,750 lbs., were replaced by the canot du maître, a canoeoften as long as 36 feet which carried about 6,000 lbs. <strong>The</strong>selarger craft were best suited for Great Lakes travel, whilevarious smaller versions remained the preferred river canoes.All of these craft were propelled by paddles, setting poles,towing lines, and square sails.Fig. 21 Canoe repair materials,as replicated by Timothy Kent.<strong>The</strong> birchbark container holdsa small piece of patching bark,a length of peeled and splitblack spruce root, a birchbarkroll containing pieces of gum(pitch and fat mixture, withpulverized charcoal added), apiece of gum in a split saplingholder, and a small meltingtorch of folded birchbark in asplit sapling handle.Fig. 22 Great Lakes woman sewing birchbark panels onto a canoe.“All these nations make a great many bark canoes, which Are very profitable for <strong>The</strong>m. <strong>The</strong>y do this Sort of work in the summer,<strong>The</strong> women sew these canoes with Roots; the men cut and shape the bark and make the gunwales, thwarts, and ribs; the womengum <strong>The</strong>m. It is no small labor to make a canoe, in which there is much symmetry and measurement; and it is a curious sight.”—Jacques Sabrevois de Bleury, commandant at Fort Pontchartrain, Detroit, 1717

14<strong>Trade</strong> Routes and TransportationFig. 23 This Ojibwe canoe is 15 ft. 9.5 in. in length.Alexander Henry On CanoesAlexander Henry was a British fur trader at Fort Michilimackinac who survived the 1763 attack on the fort because hehad been adopted into an Ojibwe family. His Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories between theYears 1760 and 1776 is a valuable account of the fur trade. In the following passage, Henry wrote about the construction,characteristics, and handling of birchbark canoes.“<strong>The</strong> canoes which I provided for my undertaking were, as is usual, five fathoms and a half [33-36 feet] in length andfour feet and a half in their extreme breadth, and formed of birch-tree bark a quarter of an inch in thickness. <strong>The</strong> bark islined with small splints of cedar-wood; and the vessel is further strengthened with ribs of the same wood, of which thetwo ends are fastened to the gunwales; several bars, rather than seats, are also laid across the canoe, from gunwale togunwale. <strong>The</strong> small roots of the spruce tree afford the wattap, with which the bark is sewed; and the gum of the pine treesupplies the place of tar and oakum. Bark, some spare wattap, and gum are always carried in each canoe for the repairswhich frequently become necessary.<strong>The</strong> canoes are worked, not with oars but with paddles, and occasionally with a sail. To each canoe there are eight men;and to every three or four canoes, which constitute a brigade, there is a guide, or conductor. Skilful men, at double thewages of the rest, are placed in the head and stern. <strong>The</strong>y engage to go from Montreal to Michilimackinac and back toMontreal again, the middle-men at one hundred and fifty livres and the end men at three hundred livres each. <strong>The</strong> guidehas the command of his brigade, and is answerable for all pillage and loss, and in return every man’s wages is answerableto him. This regulation was established under the French government.<strong>The</strong> freight of a canoe of the substance and dimensions which I have detailed consists in sixty pieces, or packages ofmerchandise, of the weight of from ninety to a hundred pounds each, and provisions to the amount of one thousandweight. To this is to be added the weight of eight men and of eight bags weighing forty pounds each, one of which everyman is privileged to put on board. <strong>The</strong> whole weight must therefore exceed eight thousand pounds, or may perhaps beaveraged at four tons.”—Alexander Henry, 1809, reminiscing about his travels (Henry 1971: 8-9)

15Making a Hat<strong>The</strong> first step in turning a beaver pelt intoa hat was the plucking of the coarse guardhairs from the beaver pelt with a large knifeor tweezers; hatmakers then brushed thepelt with a solution of nitrate of mercury tomake the scales on the small hairs stand upand become more firmly locked together ina process called carroting. If carried out in apoorly ventilated room, the mercury fumescould damage the brain, hence the expression“mad as a hatter.”After the mercury dried, the wool was shavedoff using a circular knife, and the wool wasplaced on a bench in a workroom known asthe hurdle, which had rows and columns ofslots in which the fluff could get caught andmatt. A hatter’s bow hung suspended over thebench, very much like an oversized violin bow.<strong>The</strong> vibrations of the bow helped separateand evenly distribute the hairs, until they hadformed into a thick but loosely structured matof material known as the batt.Fig. 25 A hatter uses a bow to form the fur into a batt.Several batts would then be shaped into acone and reduced in size by boiling, and thenrolled to create a firm dense felt. This wouldthen be formed into an oval to be sent on tothe hatter, who would mold it to the requiredshape, add a lining, and finish it.Fig. 26 <strong>The</strong>re were many different styles of beaver hats,though they generally went out of fashion with thedecline of the fur trade.Fig. 24 This famous nineteenth-century painting, Shooting the Rapids by FrancesAnne Hopkins, depicts fur traders running rapids in a Montreal canoe.

16A Two Way <strong>Trade</strong>: <strong>The</strong> Movement of GoodFort Michilimackinac was a major distribution center formuch of the interior region during the French era. Here voyageursstopped to stock up on supplies, canoes, and merchandise,or to spend the winter, before setting out to destinationsfurther west or back east to Montreal. Its strategic location atthe Straits of Mackinac was vital to its importance. It allowedtraders to collect furs from drainages that flowed into thewestern Great Lakes region, while it also served as a centralentrepôt for foodstuffs, canoes, canoe repair materials, andbirchbark rolls to cover travelling shelters, as well as inboundmerchandise and supplies and outbound furs and hides. Michilimackinacwas also the center for diplomacy in the westernGreat Lakes. Most major alliances were made and reaffirmedhere during the French era.Fig. 27 Reconstructed Fort Michilimackinac.In the St. Lawrence communities, large numbers of French residents worked in a wide variety of occupationsrelated to fur trade commerce. <strong>The</strong>se men and women supplied merchandise, equipment,transport vehicles, and provisions, as well as manpower and many diverse talents. For instance, as TimothyKent (2004) explains, seamstresses created shirts and hooded coats, as well as a few other garmentsand hundreds of shipping bags; finger weavers fashioned sashes and garters; pewterers cast buttons;coopers turned out kegs of various sizes; carpenters and joiners assembled rough packing crates, finerchests, and trunks; carvers made stone bowls for calumet pipes as well as canoe paddles; basket weaversfashioned durable hampers for transporting nested kettles; blacksmiths forged axes, hatchets, harpoonheads, and ice chisels; warehouse laborers unpacked, packed, and hauled cargoes; canoe buildersfashioned and repaired watercraft; forest workers gathered birchbark, lashing roots, and sealant pitch forthese crafts; and farmers raised pigs, peas, corn, wheat, and tobacco for provisions.In the territory surrounding Native villages, Native hunters harvestedpeltries. Native women then processed the pelts. <strong>The</strong> Nativesthen brought the furs to trading posts or forts, where traders baledthe pelts they collected in trade into packs for transport to Montreal.Many of the goods produced in Europe and in the St. Lawrence Valleyfor the trade and destined for Native hands have been recoveredfrom Native sites, where they were lost, disposed of, or intentionallydeposited as mortuary offerings. This is seen at Rock Island (Wisconsin),the Fletcher site (Saginaw, <strong>Michigan</strong>), and at sites associated withNatives who lived nearby and frequented Fort St. Joseph.Fort St. Joseph was one of the many permanent outposts thatthe French maintained. It stood near the Great Lakes and MississippiRiver basins as well as the Sauk Trail. <strong>Trade</strong>rs there exchangedEuropean goods like cloth, metal tools, firearms, andkettles for furs and hides that the local Native peoples (like thePotawatomi and Miami) brought to the post. While some documentarysources exist from the fort, its recent discovery andongoing archaeological study are providing new evidence aboutthe daily activities that took place at this trading post in the NorthAmerican interior.Fig. 28 Native women prepared hides. A woman smokes a skin [left],another cleans the flesh off the back [center], and another sews.

s and <strong>Fur</strong>s17Kettles made of sheet metal were among the most popular trade items becausethey provided distinct advantages to Natives who acquired them. Kettles didnot break easily and they were more portable than ceramic pots; they could berepaired with metal patches, and could be repurposed for other uses when thekettle was no longer repairable. <strong>Trade</strong> good lists often recorded kettles by valueof pound weight (or nest weight) and whether they were made of brass, copper,or tinplate. In terms of value by weight, tinplate kettles (made of sheet or platedwith tin) were the most expensive, followed by copper and then brass.Fig. 29 Eighteenth-century brass kettle fromthe vicinity of Fort St. Joseph.When copper or brass kettles had out served their intended function and wereno longer usable, Native people cut them into pieces and reworked them toserve new purposes. <strong>The</strong>y turned some of these scraps into decorative tinklingcones, which they attached to bags, moccasins, or other items of clothing.<strong>The</strong> cones made a light jingling sound as the wearer moved. Evidence for theirproduction has been recovered from excavations at Fort St. Joseph.Fig. 30 Pieces of scrap metal from worn-out tradekettles have been recovered from Fort St. Joseph.<strong>The</strong>y were often recycled to serve new purposes asrivets, arrow points, and tinkling cones.Montreal was the site of large trade fairs during the earlyyears of the fur trade. As the sites of exchange movedwestward, Montreal remained the central location ofthe French merchants, outfitters of supplies, and labor.Merchants ordered goods from Europe and had themshipped to Quebec and then Montreal. <strong>The</strong>n they hired(or sold goods on credit to) fur traders and voyageurs, whotransported these goods to trading posts and brought backpeltries, which were then sent to Quebec and loaded aboardships for transport to Europe.La Rochelle, France was the destination for themajority of peltries from New France, and wasa major shipping port for manufactured goodsto the New World. Here, certain of the furs, especiallybeaver and otters, would be processedinto felt, sold to hat makers, and transformedinto fashionable felt hats, while most of theother furs and hides would be used to createor decorate other items of clothing.Albany was the site of colonial rivalries in the fur trade.Originally established by the Dutch as Fort Orange, the siteprovided access to the furs and hides collected by theirIroquois and Mahican allies via the Hudson River. Later, theBritish took control of the area. Many illegal French traders(and some Native groups) brought furs to the British atAlbany instead of their fellow Frenchmen at Montreal, hopingto make a better deal or avoid being caught without a licenseto trade.Small industrial workshops in France and England beganproducing goods for the fur trade in the seventeenth century.By the eighteenth century textiles, axes, kettles, and othermerchandise for the trade were being mass produced inmost large, western European cities and smaller manufacturingcenters throughout the countryside.Fig. 31 An eighteenth-century French kettle workshop.

18People of the <strong>Trade</strong> in New FranceDifferent people had various roles in the fur trade. In mostcases Natives were the primary harvesters of furs and hides.European or métis traders gathered these peltries fromNative hunters in exchange for European manufacturedgoods. Merchants, missionaries, and the military also playedimportant roles in the trade.Native Hunters and Hide PreparersMost Native men hunted beaver for its meat and fur. Capturetechniques varied from season to season and from place toplace, but favored hunting over trapping.In winter, when the fur was thickest, Native men cut holesin the ice near a beaver lodge and lowered nets through theholes. <strong>The</strong> hunters broke apart the lodge with an axe andcaught the animals in the nets as they tried to escape. <strong>The</strong>ythen struck the beaver on the head to kill them. In warmermonths, hunters broke down dams to drain the surroundingpond. <strong>The</strong> beaver, unable to escape to the water when theirlodge was broken open, were caught by the hunter’s dogs.Beaver were also shot with guns or bows and arrows. Deadfalltraps, yet another technique, crushed the animal with heavylogs: their trigger mechanisms were baited with fresh aspenor poplar twigs. Other types of traps and snares could be setalong beaver paths, or near water entry points to force beaverinto deeper water where they eventually drowned.Native women prepared the pelts. <strong>The</strong>y first skinned the beaver,and washed the skin to remove blood and dirt. <strong>The</strong>n they usedbone or stone tools to scrape off excess flesh and fat from theskin, before lacing it onto a stretching frame to dry. Once dried,these furs were hard and stiff like a board, and were known ascastor sec (dry beaver).<strong>The</strong> women sewed the smoked furs together; they were wornwith the fur side against the skin. Beaver pelts prepared thisway were known as castor gras (greasy beaver). <strong>The</strong>y were morevaluable because friction from wear and the bear grease thatNatives used to protect their skin had already loosened andremoved the outer guard hairs – thus eliminating the first stepin the felting process of hat-making.Fig. 32 A Native American woman smokes a deer hide.FictionSteel trapsFact<strong>The</strong> steel trap became widespreadonly in the nineteenth century.Other furs and hides were made into blankets or robes,garments or moccasins for use before trading. This involvedextra steps of tanning including soaking, removing hair,scraping, oiling with brains, stretching, breaking the grain,and smoking. Some archaeologists believe that smudge pits,like those found at Fort St. Joseph, were used to smoke hides,particularly those from deer, elk, and moose. After Nativewomen scraped the hides clean of flesh, fat, and hair, theyworked them with a mixture that included the cooked brainsof animals. <strong>The</strong>n they laced them onto a stretching rack,worked them with a pole, and finally sewed them into a bag-likeshape and placed them on a small frame over the smudge pits.Pinecones, green corncobs, or decayed wood were burned inthe pit to produce substantial smoke. After smudging, the hideshad a slightly golden color and remained flexible, making themreadily useable and desirable for trade.Fig. 33 <strong>The</strong> first Newhousemetal traps, like this one,were made around 1823by the Oneida Communityin Oneida, NY. Thisbeaver trap was designed tosnap shut on the animal’sleg and the teeth were toprevent the animal frompulling its foot out.Fig. 34 Natives hunted beaver usingmany different methods as shown in thiseighteenth-century illustration.

19Montreal Merchants, the Military,and the ChurchFrench traders traveling into the Great Lakes region in theseventeenth and eighteenth centuries relied upon theirmerchant partners in Montreal for trade goods and supplies. By1680, approximately 35 merchants operated in Montreal. Someof them were men of modest means who emigrated from Franceto engage in the fur trade. Others were voyageurs and traderswho worked their way into the merchant business.Although the citizens of Montreal did frequent the merchants’stores, the fur trade was a major part of the merchants’ business.<strong>The</strong>y imported trade goods from Europe, hired local craftsmenand women to manufacture some types of trade goods, outfittedthe traders with supplies, handled shipping arrangements, andevaluated and stored furs received from their trading partners inthe interior.Small garrisons of Troupes de la Marine were also sent to westernposts. Officers often accepted an assignment as a commandantat a western post as a way to make money and earn promotions.Part of a post commander’s benefits was permission to trade infurs. Commanders granted permission to traders to come in anddo business at their fort, and they supervised the trade.Native groups at peace with one another and loyal to the French.As to the men he commanded, by the standards of the day, thetroops received plenty of food and clothing and were well paid.When they retired from service, many of them established theirown farms, receiving aid from the government for the first fewyears. Voyageurs reinforced troops and provided provisions andservices, while troops provided markets and protection.<strong>The</strong> Church also provided a market for goods, and attempted topacify Natives. Missionaries had early hopes that the fur tradewould help finance and facilitate evangelization. However, theydeveloped concerns for keeping French and Natives separate toavoid “bad influences” on each other.<strong>The</strong> intemperate or un-Christian-like behavior of some furtraders undermined the priests’ efforts at conversion of Nativepeoples. Church officials also feared that traders wouldassimilate into Native society, and abandon their Christianbeliefs to adopt non-Christian Native practices.Besides being presented with an opportunity to make money,they had the difficult task of maintaining alliances and helpingavoid conflict. Post commanders were charged with keepingFig. 36 A French marine button like thisone found at Fort St. Joseph attests to amilitary presence at the fort.Figs. 37 Reproduction of a Christianreligious medallion recovered fromFort St. Joseph.Fig. 35 Castor sec on a hide stretcher.“<strong>The</strong> Jesuits undergo all these hardships for the sake of converting theIndians, and likewise for political reasons. <strong>The</strong> Jesuits are of great use to theirking; for they are frequently able to persuade the Indians to break their treatywith the English, to make war upon them, to bring their furs to the French,and not to permit the English to come amongst them.”— Peter Kalm, 1749 (Forster 1771:142)

20People of the <strong>Trade</strong> in New FranceVoyageurs and Coureurs de BoisFrom 1653 on, when French traders first ventured into theinterior, the term coureurs de bois (“runners of the woods”)generally referred to anyone who went out to trade for furs; after1681 it meant an outlaw who traded without a license. Voyageurswere legal, wage-earning canoe men who transported trade goodsand supplies to the western posts, traded this merchandise, andbrought back peltries. <strong>The</strong> majority of voyageurs came fromparishes around Montreal and Three Rivers. Many only workedtemporarily in the fur trade in return for food, clothing, andwages, and then went home to farms and families.Voyageurs were hardy men who paddled heavily-laden canoes formany miles a day. In the summer they had to travel long distancesquickly. Often they sang to set the pace of paddling, and to buoythemselves in times of exhaustion or fear. When they came toobstructions such as rapids or stretches of land between bodiesof water, they had to portage—i.e., pick up and carry their canoesover land, along with the heavy packs of supplies and goods. Notonly did the job require physical prowess, but it was dangerous.Many voyageurs lost their lives to the forces of nature or attacksfrom hostile Natives.Most were illiterate, so it is hard to know the details of their dailylives because they left few written records. Researchers have torely on what others said about them, thecontracts they signed, and archaeologicalevidence of their activities.<strong>The</strong> inbound voyages from Montreal to theStraits of Mackinac usually took from fiveto eight weeks. Outbound trips typicallytook less time, due to the assistance of theprevailing westerly wind and the currenton the long downstream run of the OttawaRiver. During these voyages, the men toiledin the canoes ten to fifteen hours a day;at their evening campsites, they repairedthe canoes, and ate meals of pea or cornsoup with salted pork, along with biscuitsor grease fried flour cakes, and brandy towash it down. <strong>The</strong> men slept with a blanketbeneath the overturned canoes, or inshelters made of a pole frame covered withlong panels of birchbark.Voyageurs maintained some of their French-Canadian identity butalso entered the social domain of Native peoples. <strong>The</strong>y adaptedto a Native way of life by adopting new clothing styles, huntingtechnologies, and some of their customs and beliefs.FictionFrench fur trappersFact<strong>The</strong> French traded for fursand hides, but seldom if everdid any significant amount ofharvesting themselves.“It is the Paddle That Brings Us”Riding along the road from Rochelle city,I met three girls and all of them were pretty.It is the paddle that brings us, that brings us,It is the paddle that brings us there.–Translation of a traditional voyageur song.(Podruchny 2006:86)Figs. 38 Voyageurs, merchants, French marines, and Jesuits all played rolesin the fur trade.

21“It is inconceivable what hardships the people in Canada mustundergo on their journies. Sometimes they must carry their goodsa great way by land; frequently they are abused by the Indians, andsometimes they are killed by them. <strong>The</strong>y often suffer hunger, thirst,heat, and cold, and are bit by gnats, and exposed to the bites ofpoisonous snakes, and other dangerous animals and insects. <strong>The</strong>sedestroy a great part of the youth in Canada, and prevent the peoplefrom growing old. By this means, however, they become such bravesoldiers, and so inured to fatigue, that none of them fear danger orhardships. Many of them settle among the Indians far from Canada,marry Indian women, and never come back again.”–Peter Kalm, 1749 (Forster 1771:275)Fig. 39 Voyageur reenactors unload their canoe.“I have been unable to ascertain the exact number[of coureurs de bois] because everyone associated withthem covers up for them.”–Jacques Duchesneau, 1680 (Eccles 1983:110)Fig. 41 Early nineteenth-century voyageurs breaking camp. Detail of FrancisAnne Hopkins, Voyageurs at Dawn, 1871.Fig. 42 A modern reenactor attaches a hide to a frame.Fig. 40 Mouth harps, like thisone found at Fort St. Joseph,were used to make music.

23Métis and Country WivesMany French voyageurs married into Native groupsand took “country wives.” Often these Native womenwere members of nations with whom voyageurstraded or wanted to build trading relationships.Establishing kinship ties with Native groups helpedto create good trade relations between Frenchmenand Natives, and bound them together bothpolitically and socially. Marriage into a clan pavedthe way for traders because much of Native socioeconomicactivity was conditioned by kinshiprelationships and reciprocal obligations.Native women sought men who could meet theireconomic needs. Marrying fur traders gave themaccess to European trade goods, and offered thempotential influence in their tribe. Some Nativewomen became traders themselves. However, whilethe bonds that formed between voyageurs and Nativewomen were important to trading alliances, they weresometimes impermanent, because both voyageurs and Nativewomen traveled extensively. Voyageurs often were relocatedfrom one year to the next, while Native women oftenscheduled activities and moved in accordance withthe seasonal availability of resources and group customs.Many such marriages, however, endured the lifetimesof the partners.<strong>The</strong> children of Native women and French men were calledmétis, meaning that they were half French and half Native.<strong>The</strong>y shared ties to both cultures, and some grew up to bediplomats who could operate in both Native and Frenchworlds. Some métis children, especially daughters, were sentto Montreal to be educated. Many métis participated inthe fur trade. A mixed heritage did not have negative socialconnotations; if anything, it allowed individuals to operatefully in the worlds of both their French fathers and Nativemothers.Fig. 46 Tinkling cones, like this one found at Fort St. Joseph, adorned bothNative and voyageur garments.like Fort Ross, many of the Russian-American Company’sRussian, Creole (people of mixed Russian and indigenousancestry), and Native Alaskan men married or formedrelationships with local Native Californian women andestablished interethnic households. At the Hudson’s BayCompany’s Fort Vancouver, although clerks and officersoccupied buildings within the fort’s palisade, engagéslived in a multiethnic village of over 600 people. By thenineteenth century, most of the interior of North Americahad witnessed some form of fur trade society, providingtestimony to the trade’s pervasive influence on the Americanexperience.<strong>The</strong>se kinds of interethnic relationships were not uniqueto New France. European women were in short supply,and officials of various European nations often encouragedrelations with Native peoples because it established alliancesand ensured close social and political cooperation. At sitesFig. 47 Glass inset [left] and sleeve buttonsfrom Fort St. Joseph excavations.Fig. 48 Earrings ornose bobs found atFort St. Joseph.

24Native Peoples and the <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong>Fig. 49 Maurie, a nineteenth-centurymétis woman of the Potawatomi,holds a parasol and neckerchief whiledressed in typical Potawatomi attire ofthe day. Native and métis readiness touse European cloth and clothing didnot indicate rejection of their Nativeculture, but rather appropriation ofgenerally desired innovations.Fig. 50 Wampum belts, made from shellbeads strung together, were often given asgifts to reinforce alliances.Archaeologists have greatly altered their view of the material record of the fur trade. <strong>The</strong>y onceviewed it merely as evidence of the acculturation or assimilation of Native peoples as theyadopted European trade goods and abandoned their own technologies and traditional ways oflife. <strong>The</strong>y saw Europeans as the source of change and agency, and cast Native peoples in the rolesof minor players at best or passive victims at worst.However, more recent histories have laid to rest perspectives that commemorated fur tradehistory as a testimony to the triumph of the civilized over the savage, the Christian over theheathen, or viewed the fur trade as the precursor to inevitable settlement. Despite the factthat Natives played a vital role in the development of the trade, and scholars have documentedthe trade’s severe consequences for Native groups, their centrality in the institution was longignored. <strong>The</strong> field of ethnohistory, developed in the 1950s, constituted early efforts to employwritten (and other) sources of evidence to examine the muted voices of Native peoples and recastfur trade history as an aspect of Native history. Likewise, archaeology recovers the remains ofmaterial goods in cultural context, often allowing investigators to ascertain how Natives used,modified, or discarded them in daily practice.Fig. 52 Some Natives converted; thosewho did often still retained traditionalbeliefs alongside their Christian faith.Shifting Political Alliancesand PowerPolitical and military alliances createdthrough the fur trade could entangle Nativegroups in wars with other Natives andbetween rival European groups. AlthoughAlgonquian peoples mostly allied themselveswith the French, and Iroquois groups with theBritish, this was not always the case. Nativegroups sometimes remained independent andpolitically savvy; they could switch alliancesto serve their best economic and diplomaticinterests. However, they often becameinvolved in European-related warfare andsuffered the death and destruction of thoseconflicts.Fig. 51 A shell bead found atFort St. Joseph.Fiction<strong>Trade</strong>rs cheated the NativesFactCertainly some tried, but Natives had beentrading among themselves for thousands ofyears. <strong>The</strong>y knew quality and price, and how toget a good deal.“Mi I pi bnowi ga dawadwat Neshnabek mine Wemtegozhik, ga nadkendmwat ma shna Neshnabek odi shke-nadzwen zam cagegego ga anjsemget bgeji mteno zam shke-madshkewezwen. E-wi geget nsostmyag ga zhwebek, ta nadkendmned ga ezh-nendmwat.Mteno odi ta zhwebet geshpen nadkendmned wi-ji Neshnabemyag.”“So in that time when the Neshnabe and the French traded together, the Neshnabek sought to understand this new way,because everything had changed just a bit partly because of new technology. For us to truly understand what happened,we should seek to know how they thought. This can only happen if we learn how to speak the Neshnabe language.”–Michael Zimmerman, Jr., Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, Pokagon Band of Potawatomi

25Religion and WorldviewRoman Catholic missionaries attempted to persuade Nativepeoples to abandon their traditional beliefs and convert toChristianity. Some converted and others did not. Nativeswho converted often still retained traditional beliefs alongsidetheir Christian faith. <strong>The</strong> introduction of Christianity causedmany Natives to rethink their worldviews—especially in theface of widespread disease which their curing rituals could notcontrol and which seemed to have little impact on ChristianEuropeans.Likewise, contact with Indians, whom Europeans had notknown of only a few decades before, challenged Europeanperspectives. Europeans had to rethink their view of the Bible(the central text of European worldview) which appearednot to have accounted for the existence of Native Americans.At the same time, close contact with a culture so differentfrom their own, yet obviously complex, led Europeansto contemplate the notion that there were multiple waysto organize society. This sort of cultural relativism wasparticularly pronounced among Jesuit missionaries who wroteabout these ideas in books that were read by the intellectualelite in Europe.“Native people sought to shape the fur trade according to theirown cultural values, and to use the trade to serve their best interests…<strong>The</strong>trade arose though a process of cultural compromise.”Cultural Change and ContinuityContact with Europeans changed many aspects of Nativeculture, although many traditional practices endured.—Dean Anderson, 1994European diseases, spread through contact via trade andmissionary activity, killed vast numbers of Natives. Oldermembers of societies who held cultural memories and politicalpower were among the most affected. This undermined Nativecultural practices and the ability of some groups to protecttheir interests effectively. <strong>The</strong> young were also heavily impactedby epidemic disease and this compromised a groups’ ability tomaintain itself biologically. In a weakened state, many groupscould not resist encroachment onto their lands by Europeansand Native intruders.Alcohol, always a controversial trade item, also had devastatingeffects. Natives had no cultural mechanisms for alcoholuse—they drank mostly to become intoxicated and reach adream state which alcohol seemed to facilitate. Drunkennessled to violence and poor trades, while prolonged alcohol useeventually led to the usual gamut of physical ailments.Fig. 53 Natives farming in the St. Lawrence Valley.<strong>The</strong>n those peltries were used to purchase commercially-madecommodities, rather than the Native people producing thosearticles themselves.Natives readily incorporated European and American goodsinto their society, and used them to enhance prestige withinthe community and material prosperity. However, Nativepeoples selectively adopted and reinterpreted these goods to fitinto their established cultures.Native gender roles shifted as patterns of life changed. SomeEuropeans deliberately tried to get Natives to farm in aEuropean manner, even among those groups that alreadypracticed horticulture. For example, among Iroquoian groupsmissionaries attempted to get males to farm, when in fact itwas traditionally women’s work.<strong>The</strong> fur trade encouraged hunting for purposes of trade andnot just for subsistence. In fact, over time, the emphasis ofNative life changed toward the harvesting of furs and hides.Fig. 54 Crucifix found at Fort St. Joseph.

26<strong>Trade</strong> Goods and the Material Culture of tInteraction brought both Europeans and Native Americansinto contact with new forms of material culture, which theyselectively adopted or rejected.Natives participated in the fur trade in part because theydesired European trade goods that made their lives easier.Native groups selectively adopted trade goods to serve theirown needs. Often they chose goods that were replacementsfor traditional objects with which they were already familiar,such as cutting tools (knives, axes), cooking vessels (brasskettles), and clothing. <strong>The</strong>se goods did not necessarilycreate dependency. <strong>The</strong> archaeological record shows us thattraditional technologies and tools continued to exist alongsidenew European ones for remarkably long periods of time.Natives carefully considered what trade goods they sought out.<strong>The</strong>y adopted the most useful goods and used them in waysthat blended into existing Native culture.For their part, Europeans also selectively adopted manyNative technologies, such as birchbark canoes, snowshoes,FictionBlankets came in “Points”: 2-point,3-point, 4-point blankets. <strong>The</strong> pointsreferred to the number of beaver peltsrequired to obtain one.“Though many nations imitate the French customs; yet I observed on the contrary, that the French in Canada in manyrespects follow the customs of the Indians, with whom they converse every day. <strong>The</strong>y make use of the tobacco-pipes,shoes, garters, and girdles, of the Indians. <strong>The</strong>y follow the Indian way of making war with exactness; they mix thesame things with tobacco; they make use of the Indian bark-boats (canoes) and row them in the Indian way; theywrap square pieces of cloth round their feet, instead of stockings, and have adopted many other Indian fashions.”—Peter Kalm, 1749 (Forster 1771: 254)FactIn reality, points denoted the size andquality of the blanket, not its price.and toboggans. <strong>The</strong>y also adopted Native clothing styles andfoodways, as attested to by many sources on the fur trade. Someof these foods included maple sugar, wild rice, and many wildgreens and roots.Cloth and ClothingCloth, sewing supplies, and clothing were among the mostcommon trade goods in the western Great Lakes, by both valueand volume. Cloth itself rarely preserves in the archaeologicalrecord, but historical documentation indicates that fabrics,completed garments, and sewing supplies accounted for morethan 60% of trader expenditures for goods. <strong>Trade</strong> inventoriesrecorded many ready-made items. Shirts, hooded coats,stockings, and neckerchiefs were the most numerous, withlesser numbers of breeches, waistcoats, caps, and jackets. <strong>The</strong>lists also included fabrics (woolens, linens, cottons, and silks),thread, ribbon, tape, lace, buttons, needles, straight pins,thimbles, and scissors. Archaeologists have recovered some ofthe latter objects at Fort St. Joseph.Both Natives and Europeans greatly desiredEuropean clothing since garments neededconstant replacement due to wear. For Nativewomen, the use of European textiles instead oftanned hides reduced the amount of time andlabor they had to invest in making clothing,leaving more time for other domestic activities aswell as activities related to the fur trade. Nativewomen also liked the greater comfort of cloth,compared to hides, and the increased variety ofstyles possible with fabric’s flexibility and rangeof bright colors and textures.Fig. 55 Native groups adopted European goods like guns, kettles, axes, and cloth andblended them into their cultures.Cloth had to be brought from Europe becauseboth French and British laws banned itscommercial production in the colonies. Lengthswere carefully inspected and marked with leadseals that showed that no one had tamperedwith the fabric. Seals sometimes recorded otherinformation about the cloth, such as its place ofmanufacture, the company that imported it, andits quality. After being removed, lead seals couldserve other purposes. <strong>The</strong>y could be melted downinto musketballs or shot, or molded into objectsfor personal adornment.

he <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong>27William Burnett’s <strong>Trade</strong> List<strong>The</strong> British abandoned Fort St. Joseph in 1781. When thearea came under American control, American trader WilliamBurnett carried on fur trade activity near the mouthof the St. Joseph River. On September 26, 1797 (16 yearsafter the British abandoned Fort St. Joseph), he wrote aletter to ask to buy the following items from Mr. RobertInnes and Company in Detroit. Many of the articles arerelated to fabric and clothing:Fig. 56 Straight pins recovered fromFort St. Joseph.Fig. 57 Europeansadopted tobacco fromNative Americans.<strong>The</strong>se stone pipe bowlsare evidence of tobaccouse at Fort St. Joseph.4 pieces of Blue Stroud Small Cord16 pieces of 2-1/2 point Blankets15 pieces of Calico4 pieces of Indian ribband1 piece of Green Cloth 6 & 7/ p yard3 Gross white Mettal Buttons500 large Silver Brooches2 pieces Striped Cotton1000 Small broaches15 pounds rice1 Bushel Salt2 pounds Hyson Tea2 pounds of Green Tea1 pound Salt Petre2 € Large Nails— William Burnett, 1797 (Burnett 1967:81-82)Fig. 58 Lead seals once attached to cloth can provide details of how thefur trade worked. <strong>The</strong> writing on this seal, found during the 2011 fieldseason at Fort St. Joseph, has been interpreted as “Bureau Foraine deLille,” which was a taxing authority in eighteenth-century France froma region well known for cloth production.Clothing-related artifacts such as buttons, thimbles, straight pins, scissors, and an awl from Fort St. Joseph abound in thearchaeological record, pointing to the importance of fabrics and clothing in everyday life.Fig. 59 Metal and bone buttons. Fig. 60 Thimbles and baling needles. Fig. 61 Straight pins, scissors, and an awl.

28<strong>Trade</strong> Goods and the Material Culture of thFirearmsFirearms were a highly prized item in the furtrade. At first the French were wary of givingor trading guns to Natives. However, in the1640s, the French reversed their policy aftertheir enemies, the Iroquois, had acquiredflintlocks from the Dutch. While Nativesobtained the majority of guns through trade,a significant number were given as gifts tosolidify alliances.<strong>The</strong>re were different types of flintlocks usedin New France. Fusils ordinaires were themost common type of gun used in the furtrade. <strong>The</strong>y did not possess tested barrels,and their decorations were etched intothe gun’s iron or brass furniture, not cast.Military muskets of various sizes were issuedto soldiers stationed at forts, and consistedof simple yet durable locks and metalfurniture. <strong>The</strong>se guns were manufacturedwith proved (tested) barrels to increaseaccuracy and to guard against bursting whenfired. Ornately adorned fusils fins were highquality muskets with proved barrels. <strong>The</strong>ywere carried by officers, prominent explorers,and traders, or presented to high-rankingNatives as gifts. Fusils fins were worth abouttwice as much as fusils ordinaires. JeanBoudriot estimated that about 1 fusil finwas shipped to America for every 20 fusilsordinaires.Natives demanded muskets, but did notabandon their traditional weapons due tothe sometimes unreliable nature of firearms.<strong>The</strong> early flintlock could be a remarkablyineffective weapon, and its initial militaryadvantage is hotly debated. This was trueof most early firearms. Guns could benotoriously erratic weapons, needing constantmaintenance and cleaning; they easily brokedown, were frequently in need of repair, andrequired a continual supply of gunpowderand shot. In contrast, bows and arrows wereeasier to acquire, faster to use, and often moreeffective. With technological improvements,firearms provided a major military advantage.Despite their drawbacks, firearms of all sortswere highly sought after, and granted theNative bearer a level of prestige.Gifts of guns helped reinforce alliancesbecause Native groups needed the servicesof French gunsmiths to keep the guns inworking order, as they often did not haveexperience in repairs themselves. Nativesoften asked the Crown to provide gunsmithsto repair guns. Oftentimes gunsmithswere sent out with voyageurs, or they werevoyageurs themselves. Sometimes theyworked for the Church. A cache of gunparts recovered from Fort St. Joseph hasbeen interpreted as associated with AntoineDeshêtres, the resident blacksmith/gunsmithat the post during the 1730s-40s.FictionMuskets were so long because thetraders made the Natives offer astack of beaver pelts as high asthe musket was long.Fig. 63 Honey-colored, spalltypegunflints, like this onerecovered from Fort St. Joseph,struck a steel frizzen to createthe spark which ignited the gunpowder.“Let us trade light guns small in hand and wellshap’d, with locks that will not freese in the winter.”—Native trader quoted by Edward Umfreville,“Present State of Hudson’s Bay,” London, 1790Fig. 62 Flintlock hardware and ammunition from FortSt. Joseph: 1. gun cock, 2. honey-colored French gunflint,3. vise screw, 4. lock plate with frizzen, 5. breech plug,6. main spring, 7. serpentine sideplate fragment,8. trigger guard, 9. musketballs, and 10. lead shot.

e <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong>29FactWeapon barrels were madelong in an attempt toimprove accuracy.Figs. 64 and 65 Top and side views of an axehead found at Fort St. Joseph in 2011.Metal GoodsMetal artifacts were among the goods thatNative peoples chose to acquire in exchangefor furs. At Fort St. Joseph and othersimilar sites, archaeologists have found ironaxe heads, iron knife blades, gun parts, andbrass kettle pieces, as well as myriad othermetal objects.Scholars long believed that Nativesadopted European metal tools wholesale,and totally replaced all previously existingNative American technologies. This isnot true, as Native American groupswere selective in which metal items theyadopted. <strong>The</strong>y chose to adopt some,continued to use stone and bone toolsalongside metal ones, and also foundentirely new uses for some of the metalgoods that the French had to offer.<strong>The</strong> metal goods that Native peoplesadopted most frequently includeknives, axes, and kettles. <strong>The</strong>se durableand efficient tools offered substantialadvantages over traditional chipped andground stone implements, and containersmade of wood, bark, or clay. <strong>The</strong>y did notadopt other European goods so quickly.Archaeologists have noted that NativeAmericans continued to use stone and bonetools at a number of sites long after Frenchtraders introduced metal tools. Europeanmetal fishhooks are found along thewestern shore of Lake <strong>Michigan</strong> on RockIsland, Wisconsin, but bone fishing toolsoutnumber them. This suggests that Nativesfound these bone tools just as effective asmetal ones, and did not entirely replacethem. Stone scrapers were also as effectiveas similar metal tools, and were easier toobtain and maintain. Stone arrowheads areoften found in the same context as metalimplements and in some ways the bow andarrow was a more effective and flexibletechnology than the flintlock musket forsome purposes.While Native Americans used manyEuropean trade goods as they wereintended, they modified many other goodsand materials. Archaeologists often findmetal tools that show evidence of havingbeen used in unique ways or modified fornew purposes. Examples include axe headsused as hammers, anvils and wedges; gunbarrels flattened for use as digging tools andscrapers; gun buttplates modified into hidescrapers; and pieces of brass and copperkettles that were reshaped into tinklingcones, arrowheads, or scrapers.Brass and copper kettles were one of themost commonly repurposed Europeanmetal goods. Natives recycled worn outkettles into new goods such as arrowpoints, scrapers, and awls, and ornamentssuch as tubular beads, pendants, andtinkling cones.Evidence of how Natives modified metals for new purposes is shown in Figs. 66-68.Fig. 66 An artifact that appears to be amusket barrel modified into a hide scraper.Fig. 67 Decorative earring ornosebob.Fig. 68 Brass tinkling cones.

30<strong>Trade</strong> Goods and the Material Culture of thAlcoholAlcohol was a controversial trade item. French officials, religious leaders, andNative leaders attempted to limit its use in the fur trade.Drinking alcohol was a common part of everyday life for many Europeans in furtrade society. Many viewed moderate consumption of it as an aid to health anddigestion. Voyageurs were often allowed to bring their own personal ration ofbrandy along with them in their travels, and sometimes their employers providedit. This practice often made the use of alcohol in the fur trade hard to regulate,because it was difficult to tell how much was intended for personal use by thevoyageurs and how much was intended for trade with Native Americans.Some scholars have argued that Natives wanted alcohol because intoxication wasthought to be a semi-spiritual experience. For them, alcohol was a new way toachieve an old traditional goal of reaching the spirit world. Most Natives werenot immediately aware of the social problems alcohol could cause, because theirculture had not had prior exposure to it. Later, some Native leaders attempted toprohibit or limit the use of alcohol by their people.French missionaries and clergymen opposed the sale of alcohol to Native peoples,whom they sought to convert to Christianity. Drunkenness, alcoholism, andrelated violence became a troubling problem. <strong>The</strong> clergy also worried that traderswould try to swindle Natives out of their hard-earned furs by getting them drunkbefore trading transactions. At one point, Bishop François de Laval threatened toexcommunicate anyone known to have traded liquor to the Natives.Alcohol in <strong>Fur</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> ListsAlcohol does appear in fur trade ledgers,but during periods when it was illegalto trade, exact records were likely notkept in order to avoid penalties, makingit difficult for historians to estimate howprevalent alcohol really was as a tradeitem. <strong>The</strong> following “account of DavidMcCrae & Co. Dr to Goods for one Canoefor Msr. Landoise” was a fur trade recordkept at Michilimacinac and includes thefollowing alcohol-related items:2 Barrells Port WineBarrells & filling1 do [ditto] Spiritts 8 GallonsBarrell1 do Brandy8 Gallons for the Men1 do do do for Landoise—(Armour and Widder 1978:205)When the clergy demanded that French officials ban the sale of alcohol toNatives, some fur traders objected strongly. Alcohol, especially brandy, was ahighly profitable trade item that Natives wanted to buy. Natives would constantlyneed to renew their supplies of this high-demand consumable item. <strong>The</strong> clergyand French officials sometimes bickered over the issue.Fig. 70 Spigots, like this one fromMichilimackinac, were used to tap kegs.Fig. 69 Church officials and missionaries wereoften outspoken about prohibiting alcohol as atrade item.