Are there hybrid regimes? Or are they just an optical ... - Studium

Are there hybrid regimes? Or are they just an optical ... - Studium

Are there hybrid regimes? Or are they just an optical ... - Studium

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Europe<strong>an</strong> Political Science Review (2009), 1:2, 273–296 & Europe<strong>an</strong> Consortium for Political Researchdoi:10.1017/S1755773909000198<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? <strong>Or</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>they</strong> <strong>just</strong><strong>an</strong> <strong>optical</strong> illusion?LEONARDO MORLINO*Istituto Itali<strong>an</strong>o di Scienze Um<strong>an</strong>e, Florence, ItalyIn recent years <strong>there</strong> has been growing interest <strong>an</strong>d a related literature on <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>.Is <strong>there</strong> a good definition of such <strong>an</strong> institutional arr<strong>an</strong>gement? <strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> actually sets ofstabilized, political institutions that c<strong>an</strong> be labelled in this way? Is it possible that withinthe widespread process of democracy diffusion these <strong>are</strong> only ‘tr<strong>an</strong>sitional’ <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>an</strong>dthe most suitable distinction is still the old one, suggested by Linz <strong>an</strong>d traditionallyaccepted, between democracy <strong>an</strong>d authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism? This article addresses <strong>an</strong>d respondsto these questions by pinpointing the pertinent <strong>an</strong>alytic dimensions, starting withdefinitions of ‘regime’, ‘authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism’, <strong>an</strong>d ‘democracy’; by defining what a ‘<strong>hybrid</strong>regime’ is; by trying to <strong>an</strong>swer the key question posed in the title; by disent<strong>an</strong>gling thecases of proper <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> from the cases of tr<strong>an</strong>sitional phases; <strong>an</strong>d by proposing atypology of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. Some of the main findings <strong>an</strong>d conclusions refer to the lackof institutions capable of performing their functions as well as the key elements forachieving possible ch<strong>an</strong>ges towards democracy.Keywords: regime; democracy; authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism; <strong>hybrid</strong> regime; classification of <strong>regimes</strong>IntroductionThe diffusion of democratization <strong>an</strong>d the enormous development of relatedresearch in different <strong>are</strong>as of the world (Morlino, 2008) has recently aroused greatinterest in the more specific theme of the spread of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. As a consequence,the view of Croiss<strong>an</strong>t <strong>an</strong>d Merkel (2004: 1) that ‘ythe conceptual issueof diminished sub-type of democracyyhave begun the new predomin<strong>an</strong>t trend indemocratic theory <strong>an</strong>d democratization studies’, comes as no surprise. Nor is theassertion by Epstein et al. (2006: 556, 564, 565) that ‘partial democracies’‘account for <strong>an</strong> increasing portion of current <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>an</strong>d the lion’s sh<strong>are</strong> ofregime tr<strong>an</strong>sitions’, adding, however, that <strong>there</strong> is little available informationabout ‘what prevents full democracies from sliding back to partial democracies orautocracies, <strong>an</strong>d what prevents partial democracies from sliding back to autocracy’<strong>an</strong>d that ‘the determin<strong>an</strong>ts of the behaviour of the partial democracieselude our underst<strong>an</strong>ding’. Nor, finally, is it surprising that a variety of labels have* E-mail: morlino@sumitalia.it273

274 LEONARDO MORLINObeen coined for these <strong>regimes</strong> by different authors: ‘façade democracies’ <strong>an</strong>d‘quasi-democracies’ (Finer, 1970), dictabl<strong>an</strong>das <strong>an</strong>d democraduras (Rouquié,1975; O’Donnell <strong>an</strong>d Schmitter, 1986), ‘exclusionary democracy’ (Remmer,1985–1986), ‘semi-democracies’ (Diamond et al., 1989), ‘electoral democracies’(Diamond, 1999 <strong>an</strong>d Freedom House), ‘illiberal democracies’ (Zakaria, 1997),‘competitive authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms’ (Levitsky <strong>an</strong>d Way, 2002), ‘semi-authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms’(Ottaway, 2003), ‘defective democracies’ (Merkel, 2004), ‘partial democracies’(Epstein et al., 2006), <strong>an</strong>d ‘mixed <strong>regimes</strong>’ (Bunce <strong>an</strong>d Wolchik, 2008), to mention<strong>just</strong> some of the expressions <strong>an</strong>d some of the scholars who have investigated what isdenoted here by the broader term of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> (see, in particular, Karl, 1995;Diamond, 2002; Wigell, 2008). 1In trying to gain a better underst<strong>an</strong>ding of the reasons for such attention it isworth bearing in mind that complex phenomena such as democratization <strong>are</strong> neverlinear, <strong>an</strong>d cases of a return to more ambiguous situations have by no me<strong>an</strong>s beenexceptional in recent years. Moreover, cases of democracies, even if minimal, going‘all’ the way back to stable authoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> have been much less frequent: 2 it ismore difficult, though not impossible, to recreate conditions of stable coercion oncethe majority of a given society has been involved <strong>an</strong>d become politically active in thecourse of tr<strong>an</strong>sition. If nothing else, as Dahl (1971) noted m<strong>an</strong>y years ago, greatercoercive resources would be required. Furthermore, in periods of democratization,even if only as a result of <strong>an</strong> imitation effect, authoritari<strong>an</strong> crises <strong>an</strong>d the resultinginitial phases of ch<strong>an</strong>ge should be more frequent. Consequently, <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong> severalreasons for the greater frequency of <strong>regimes</strong> characterized by uncertainty <strong>an</strong>d tr<strong>an</strong>sition.Moreover, if the ultimate goal is to examine <strong>an</strong>d explain how <strong>regimes</strong> movetowards democracy, it is fully <strong>just</strong>ified, indeed opportune, to focus on those phasesof uncertainty <strong>an</strong>d ch<strong>an</strong>ge. But here we have a relev<strong>an</strong>t aspect that – this timesurprisingly – the literature has failed to address <strong>an</strong>d solve: when considering thosephases of uncertainty <strong>an</strong>d ambiguity, <strong>are</strong> we dealing with <strong>an</strong> institutionalarr<strong>an</strong>gement with some, perhaps minimal, degree of stabilization, namely <strong>are</strong>gime in a proper sense, or <strong>are</strong> we actually <strong>an</strong>alysing tr<strong>an</strong>sitional phases fromsome kind of authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism (or traditional regime) to democracy, or vice versa?In addressing this key issue, this article will pinpoint the pertinent <strong>an</strong>alyticdimensions, starting with definitions of the terms ‘regime’, ‘authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism’, <strong>an</strong>d‘democracy’; discuss <strong>an</strong>d clarify the reasons for the proposed definition of <strong>hybrid</strong>regime; try to <strong>an</strong>swer the key question posed in the title, which, as will becomeclear, is closely bound up with the prospects for ch<strong>an</strong>ge in the nations that havesuch ambiguous forms of political org<strong>an</strong>ization <strong>an</strong>d, more in general, with thespread of democratization; propose a typology of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>; <strong>an</strong>d, in the lastsection, will reach a number of salient conclusions.1 See also Collier <strong>an</strong>d Levitsky (1997: 440), where <strong>there</strong> is <strong>an</strong> exhaustive list of all ‘diminishedsubtypes’, that is <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>, that <strong>are</strong> present in the literature on the topic.2 See below for more on the me<strong>an</strong>ing of the terms as used here.

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 275A widespread phenomenon?The simplest <strong>an</strong>d most immediate way of underst<strong>an</strong>ding the nature of the phenomenonunder scrutiny is to refer to the principal sets of macro-political data thatexist in literature. Data has been ga<strong>there</strong>d by international bodies like the WorldB<strong>an</strong>k, the OECD <strong>an</strong>d the United Nations; by private foundations, such as theIDEA <strong>an</strong>d Bertelsm<strong>an</strong> Stiftung; by individual scholars or research groups, likePolity IV, originally conceived by Ted Gurr, or the project on hum<strong>an</strong> rights protectionundertaken by Todd L<strong>an</strong>dm<strong>an</strong> (2005), who formulated indicators ofdemocracy <strong>an</strong>d good govern<strong>an</strong>ce, <strong>an</strong>d also produced <strong>an</strong> effective survey (L<strong>an</strong>dm<strong>an</strong>,2003) of various initiatives in this field; <strong>an</strong>d even by prominent magazines like theEconomist, whose Intelligence Unit has drawn up a well-designed index of democracy.But it is not necessary to survey these here. Despite all the limitations <strong>an</strong>dproblems, which have been widely discussed, 3 for the purposes of this article, the dataprovided by Freedom House have the insuperable adv<strong>an</strong>tage of enabling a longitudinal<strong>an</strong>alysis. In fact, <strong>they</strong> have been collected since the beginning of the 1970s<strong>an</strong>d regularly updated on <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>nual basis. These data c<strong>an</strong>, <strong>there</strong>fore, be used togain a better grasp of the phenomenon. 4In 2008, the Freedom House data feature 60 out of 193 formally independentcountries (in 2007 <strong>there</strong> were 58), which have 30% of the world’s population <strong>an</strong>d<strong>are</strong> political arr<strong>an</strong>gements that c<strong>an</strong> be defined as partially free, the concrete termclosest to the notion of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. 5 ‘Partially free’ <strong>regimes</strong> have <strong>an</strong> overallrating r<strong>an</strong>ging from three to five. 6 They <strong>are</strong> present in every continent: five inEurope (four of which <strong>are</strong> in the Balk<strong>an</strong>s), 24 in Africa, 18 in Asia (six <strong>are</strong> in theMiddle East), nine in the Americas (five in South America <strong>an</strong>d four in CentralAmerica), <strong>an</strong>d four in Oce<strong>an</strong>ia. There <strong>are</strong> also 43 non-free <strong>regimes</strong>, which mightbe defined as stable authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms <strong>an</strong>d correspond to 23% of the population, 7<strong>an</strong>d 90 democracies, amounting to 47% of the world’s population. Overall, then,the partially free <strong>regimes</strong> exceed the non-free ones both in number <strong>an</strong>d in terms of3 The main criticisms regarded the right-wing liberal bias of the Institute itself <strong>an</strong>d consequently thecompiling of unfair ratings for the assessed countries. Although basically appropriate at the beginning,these criticisms have been overcome <strong>an</strong>d neutralized by the subsequent developments characterized bymore reliable empirical results. This relev<strong>an</strong>t conclusion is strongly supported by the high number ofquotations <strong>an</strong>d attention that Freedom House data have received in recent years. Even a quick look on theInternet will vividly show all this.4 Even some of the most interesting data, such as those of the Index of failed states (see http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id53865) or of Polity IV (see http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm) were discarded in favour of Freedom House data for the reasons mentioned inthe text.5 See below for a necessary <strong>an</strong>d more specific definition.6 It should be remembered that Freedom House adopts a reverse points system: a score of onecorresponds to the greatest degree of democracy in terms of political rights <strong>an</strong>d civil liberties, while sevencorresponds to the most repressive forms of authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism as regards rights <strong>an</strong>d freedom. The electoraldemocracies need to be distinguished amongst these. For more on the definition <strong>there</strong>of, see below.7 As is known, about half of this population lives in a single nation, China.

276 LEONARDO MORLINOpercentage of population. One further observation is that, with a few exceptionslike Turkey, 8 most of the nations that fall within the ‘partially free’ category <strong>are</strong>medium-small or small. Finally, from a Europe<strong>an</strong> point of view, despite the intenseefforts of the Europe<strong>an</strong> Union, other international org<strong>an</strong>izations, <strong>an</strong>d specificEurope<strong>an</strong> governments, almost none of the Balk<strong>an</strong> nations have embraceddemocracy: apart from Slovenia <strong>an</strong>d Croatia; Serbia is on the borderline whileAlb<strong>an</strong>ia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia (which has even applied to join theEurope<strong>an</strong> Union), <strong>an</strong>d Montenegro <strong>are</strong> partially free <strong>regimes</strong>. The other Europe<strong>an</strong>nation in the same situation is Moldova, which borders onto Rom<strong>an</strong>ia <strong>an</strong>dUkraine. However, before proceeding <strong>an</strong>y further with the empirical <strong>an</strong>alysis, it isnecessary to define some terms, which will hopefully help to give greater precisionto the current rather fuzzy terminology.Definition <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>alytic dimensionsBefore proceeding with our <strong>an</strong>alysis, it is worth stating that we prefer the term‘<strong>hybrid</strong> regime’ to all the others present in the literature (see above) as this is thebroadest notion, whereas most of the others (e.g. ‘exclusionary democracy’,‘partial democracies’, ‘electoral democracies’, ‘illiberal democracies’, ‘competitiveauthoritari<strong>an</strong>isms’, ‘defective democracies’, <strong>an</strong>d ‘semi-authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms’) seem torefer to more specific models, mainly diminished forms of democracy. And itseems appropriate to come up with a precise definition of the broadest notionbefore going ahead <strong>an</strong>d mapping out the diversified realities inside it. 9 In short, we<strong>are</strong> looking here for the ‘genus’ that comes before the ‘species’.Moreover, <strong>an</strong> adequate conceptualization of the ‘<strong>hybrid</strong> regime’ must start witha definition of both the noun <strong>an</strong>d the adjective ‘trapped’ between a non-democratic(above all, traditional, authoritari<strong>an</strong>, <strong>an</strong>d post-totalitari<strong>an</strong>) <strong>an</strong>d a democratic set-up.As regards the term ‘regime’, consideration will be given here to ‘the set of governmentinstitutions <strong>an</strong>d of norms that <strong>are</strong> either formalized or <strong>are</strong> informally recognizedas existing in a given territory <strong>an</strong>d with respect to a given population’. 10Emphasis will be placed on the institutions, even if <strong>they</strong> <strong>are</strong> not formal, that exist in8 The inclusion of Turkey in this group of countries has already prompted debate, <strong>an</strong>d other <strong>an</strong>alysts,especially Turkish scholars, place it amongst the minimal democracies, stressing the great <strong>an</strong>d now longst<strong>an</strong>dingfairness of the electoral procedure, for which Freedom House does not award the maximumrating.9 Other terms, such as ‘mixed <strong>regimes</strong>’, <strong>are</strong> also very broad, but ultimately ‘<strong>hybrid</strong>’ was preferred to‘mixed’ as the former term gives more precisely the gist of the phenomenon where new <strong>an</strong>d old aspectsch<strong>an</strong>ge each other , that is, it is not <strong>just</strong> a problem of ‘mixing’ (see below for the definition <strong>an</strong>d classification).10 A more complex definition is offered by O’Donnell (2004: 15), who suggests considering thepatterns, explicit or otherwise, that determine the ch<strong>an</strong>nels of access to the main government positions,the characteristics of the actors who <strong>are</strong> admitted or excluded from such access, <strong>an</strong>d the resources orstrategies that <strong>they</strong> c<strong>an</strong> use to gain access. An empirically simpler line is adopted here, which is based onthe old definition by Easton (1965). But see also Fishm<strong>an</strong> (1990).

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 277a given moment in a given nation. While <strong>they</strong> no longer configure some form ofnon-democracy <strong>an</strong>d do not yet configure a complete democracy, such institutionsstill bear traces of the previous political reality. In addition, in order to havesomething that may be labelled as a regime we need <strong>an</strong> at least minimal stabilization.Fishm<strong>an</strong> (1990: 428) recalls that <strong>regimes</strong> ‘<strong>are</strong> more perm<strong>an</strong>ent forms ofpolitical org<strong>an</strong>ization’. 11 Otherwise, we ‘pick up fireflies for l<strong>an</strong>terns’ by confusinga temporary ch<strong>an</strong>ging situation with a more stabilized one, whatever <strong>there</strong>asons might be. Obviously, the consequences of making such a distinction <strong>are</strong>very signific<strong>an</strong>t. In <strong>an</strong>y case, we will totally misunderst<strong>an</strong>d the entire situation ifwe fail to assess if <strong>there</strong> is or has been stabilization or not. This will be a keyelement of our definition, one that differentiates it from those existing in theliterature, even the most prominent ones (see above).The second point that c<strong>an</strong> be stressed is that a regime does not fulfil the minimumrequirements of a democracy, in other words it does not meet all the more immediatelycontrollable <strong>an</strong>d empirically essential conditions that make it possible toestablish a threshold below which a regime c<strong>an</strong>not be considered democratic. In thisperspective for a minimal definition of democracy, we need at the same time: (a)universal suffrage, both male <strong>an</strong>d female, (b) free, competitive, recurrent, <strong>an</strong>d fairelections, (c) more th<strong>an</strong> one party, <strong>an</strong>d (d) different <strong>an</strong>d alternative media sources.To better underst<strong>an</strong>d this definition, it is worth stressing that a regime of this kindmust provide real guar<strong>an</strong>tees of civil <strong>an</strong>d political rights that enable the actualimplementation of those four aspects. That is, such rights <strong>are</strong> assumed to exist if<strong>there</strong> is authentic universal suffrage, the supreme expression of political rights, thatis the whole adult demos has the right to vote; if <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong> free, fair, <strong>an</strong>d recurrentelections as <strong>an</strong> expression of the effective existence of freedom of speech <strong>an</strong>d thoughtas well; if <strong>there</strong> is more th<strong>an</strong> one effectively competing party, demonstrating theexistence of genuine <strong>an</strong>d practiced rights of assembly <strong>an</strong>d association; <strong>an</strong>d if <strong>there</strong><strong>are</strong> different media sources belonging to different proprietors, proof of the existenceof the liberties of expression <strong>an</strong>d thought. One import<strong>an</strong>t aspect of this definition isthat in the absence of <strong>just</strong> one of the requirements, or if at some point one of them isno longer met, <strong>there</strong> is no longer a democratic regime but some other political <strong>an</strong>dinstitutional set-up, possibly <strong>an</strong> intermediate one marked by varying degrees ofuncertainty <strong>an</strong>d ambiguity.Finally, it is worth stressing that this minimal definition focuses on the institutionsthat characterize democracy: elections, competing parties (at least potentially so), <strong>an</strong>dmedia pluralism. It c<strong>an</strong> be added that it is also import<strong>an</strong>t, according to Schmitter<strong>an</strong>d Karl (1993: 45, 46), that these institutions <strong>an</strong>d rights should not be subject to, orconditioned by, ‘non-elected actors’ or exponents of other external <strong>regimes</strong>. Theformer refers to the armed forces, religious hierarchies, economic oligarchies, ahegemonic party, or even a monarch with pretensions to influencing decision-making11 He also adds that a state is a ‘more perm<strong>an</strong>ent structure of domination <strong>an</strong>d coordination’ th<strong>an</strong> <strong>are</strong>gime (Fishm<strong>an</strong> 1990: 428). But on this see below.

278 LEONARDO MORLINOprocesses, or at <strong>an</strong>y rate the overall functioning of a democracy. In the second case, <strong>are</strong>gime might be conditioned by <strong>an</strong> external power that deprives the democracy inquestion of its independence <strong>an</strong>d sovereignty by pursuing non-democratic policies.To avoid terminological confusion it should be pointed out that the ‘electoraldemocracies’ defined by Diamond (1999: 10), solely with regard to ‘constitutionalsystems in which parliament <strong>an</strong>d executive <strong>are</strong> the result of regular, competitive,multi-party elections with universal suffrage’, <strong>are</strong> not minimal liberal democracies,in which <strong>there</strong> is no additional room for ‘reserved domains’ of actors who<strong>are</strong> not electorally responsible, directly or indirectly; <strong>there</strong> is inter-institutionalaccountability, that is the responsibility of one org<strong>an</strong> towards <strong>an</strong>other as laiddown by the constitution; <strong>an</strong>d finally, <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong> effectively applied norms to sustain<strong>an</strong>d preserve pluralism <strong>an</strong>d individual <strong>an</strong>d group freedoms (Diamond, 1999:10, 11). 12 The term ‘electoral democracies’ is also used by Freedom House with asimilar me<strong>an</strong>ing: <strong>an</strong> electoral democracy is understood as a multi-party, competitivesystem with universal suffrage, fair <strong>an</strong>d competitive elections with theguar<strong>an</strong>tee of a secret ballot <strong>an</strong>d voter safety, access to the media on the part of theprincipal parties, <strong>an</strong>d open electoral campaigns. In the application of the term byFreedom House, all democracies <strong>are</strong> ‘electoral democracies’ but not all <strong>are</strong> liberal.Therefore, even those <strong>regimes</strong> that do not have a maximum score in the indicatorsfor elections continue to be considered electoral democracies. More specifically, ascore equal to or above seven, out of a maximum of 12, is sufficient for partiallyfree nations to be classified as electoral democracies. 13 Thus, in both uses of theterm, <strong>an</strong> ‘electoral democracy’ could only be a specific model of a <strong>hybrid</strong> regime,but not a minimal democracy.As regards the definition of non-democratic <strong>regimes</strong>, reference must be made atleast to traditional <strong>an</strong>d authoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. The former <strong>are</strong> ‘based on the personalpower of the sovereign, who binds his underlings in a relationship of fear<strong>an</strong>d reward; <strong>they</strong> <strong>are</strong> typically legibus soluti <strong>regimes</strong>, where the sovereign’sarbitrary decisions <strong>are</strong> not limited by norms <strong>an</strong>d do not need to be <strong>just</strong>ifiedideologically. Power is thus used in particularistic forms <strong>an</strong>d for essentially privateends. In these <strong>regimes</strong>, the armed forces <strong>an</strong>d police play a central role, while <strong>there</strong>is <strong>an</strong> evident lack of <strong>an</strong>y form of developed ideology <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>y structure of massmobilization, as a single party usually is. Basically, then, the political set-up isdominated by traditional elites <strong>an</strong>d institutions’ (Morlino, 2003: 80).As for the authoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>, the definition adv<strong>an</strong>ced by Linz (1964: 255) isstill the most useful one: a ‘political system with limited, non-responsible politicalpluralism; without <strong>an</strong> elaborated <strong>an</strong>d guiding ideology, but with distinctivementalities; without either extensive or intense political mobilization, except at12 The other specific components of liberal democracies <strong>are</strong> delineated by Diamond (1999: 11, 12).13 The three indicators pertaining to the electoral process <strong>are</strong>: (i) head of government <strong>an</strong>d principalposts elected with free <strong>an</strong>d fair elections; (ii) parliaments elected with free <strong>an</strong>d fair elections; <strong>an</strong>d (iii)electoral laws <strong>an</strong>d other signific<strong>an</strong>t norms, applied correctly (see the site of Freedom House).

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 279some points in their development, <strong>an</strong>d in which a leader, or, occasionally, a smallgroup, exercises power from within formally ill-defined, but actually quite predictable,limits’. However, with respect to such a definition, which identifies fivesignific<strong>an</strong>t dimensions – limited pluralism, distinctive values, 14 low politicalmobilization, a small leading group, ill-defined, but predictable limits to citizens’rights – for our purpose we need to stress the constraints imposed on politicalpluralism within a society that has no recognized autonomy or independence aswell as no effective political participation of the people, with the consequentexercise of various forms of state suppression. A further, neglected, but nonethelessimport<strong>an</strong>t dimension should also be added – the institutions that characterizeauthoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>, which <strong>are</strong> invariably of marked import<strong>an</strong>ce inm<strong>an</strong>y tr<strong>an</strong>sitional cases. Once created <strong>an</strong>d having become stabilized over a certainnumber of years, institutions often leave a signific<strong>an</strong>t legacy for a new regime,even when it has become firmly democratic.In addition to Morlino (2003), other authors stress this aspect. For example, itis worth recalling the whole debate on ‘electoral authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms’ (Schedler,2006). In fact, with this term Schedler (2006: 5) refers to specific models ofauthoritari<strong>an</strong>ism – not to a <strong>hybrid</strong> regime – specifically characterized by electoralinstitutions <strong>an</strong>d practices; in this inst<strong>an</strong>ce, <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>are</strong> the result of ch<strong>an</strong>gesthat begin within these types of authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism. Moreover, the attention given toauthoritari<strong>an</strong> institutions is relev<strong>an</strong>t for other import<strong>an</strong>t reasons. Firstly, theexistence of efficient repressive apparatuses capable of implementing the abovementioneddemobilization policies, for inst<strong>an</strong>ce security services, which may beautonomous or part of the military structure. Secondly, the partial weakness orthe absence of mobilization structures, such as the single party or unions whichmay be vertical ones admitting both workers <strong>an</strong>d employers, or other similar stateinstitutions, that is, structures capable of simult<strong>an</strong>eously generating <strong>an</strong>d controllingparticipation. There could be distinct forms of parliamentary assembly,possibly based on the functional <strong>an</strong>d corporative representation of interests (seebelow); distinctive electoral systems, military juntas, ad hoc constitutional org<strong>an</strong>s,or other specific org<strong>an</strong>s different from those that existed in the previous regime. 15Obviously, <strong>there</strong> is also <strong>an</strong>other implicit aspect that it is worth stressing: theabsence of real guar<strong>an</strong>tees regarding the various political <strong>an</strong>d civil rights.Limited, non-responsible pluralism, which may r<strong>an</strong>ge from monism to a certainnumber of import<strong>an</strong>t <strong>an</strong>d active actors in the regime, is a key aspect to recall.14 These values include notions like homel<strong>an</strong>d, nation, order, hierarchy, authority <strong>an</strong>d such like,where both traditional <strong>an</strong>d modernizing positions c<strong>an</strong>, <strong>an</strong>d sometimes have, found common ground. In<strong>an</strong>y case, the regime is not supported by <strong>an</strong>y complex, articulated ideological elaboration. In other<strong>regimes</strong>, like the traditional ones, the only effective <strong>just</strong>ification of the regime is personal in nature, that is,to serve a certain leader, who may, in the case of a monarch who has acceded to power on a hereditarybasis, be backed by tradition.15 For <strong>an</strong>other more recent <strong>an</strong>alysis of non-democratic <strong>regimes</strong>, especially authoritari<strong>an</strong> ones, seeBrooker (2000).

280 LEONARDO MORLINOFor every non-democratic regime, then, it is import<strong>an</strong>t above all to pinpoint thesignific<strong>an</strong>t actors, for whom a distinction c<strong>an</strong> be made between institutionalactors <strong>an</strong>d politically active social actors. Examples of the former <strong>are</strong> the army,the bureaucratic system or a part <strong>there</strong>of <strong>an</strong>d, where applicable, a single party;the latter include the Church, industrial or fin<strong>an</strong>cial groups, l<strong>an</strong>downers, <strong>an</strong>d insome cases even unions or tr<strong>an</strong>snational economic structures with major interestsin the nation concerned. Such actors <strong>are</strong> not politically responsible according tothe typical mech<strong>an</strong>ism of liberal democracies, that is, through free, competitive,<strong>an</strong>d fair elections. If <strong>there</strong> is ‘responsibility’, it is exercised at the level of ‘invisiblepolitics’ in the real relations between, for inst<strong>an</strong>ce, military leaders <strong>an</strong>d economicgroups or l<strong>an</strong>downers. Furthermore, elections or the other forms of electoralparticipation that may exist, for inst<strong>an</strong>ce direct consultations through plebiscites,have no democratic signific<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>an</strong>d, above all, <strong>are</strong> not the expression of rights,freedom, <strong>an</strong>d the genuine competition to be found in democratic <strong>regimes</strong>. Theyhave a mainly symbolic, legitimating signific<strong>an</strong>ce, <strong>an</strong> expression of consensus <strong>an</strong>dsupport for the regime on the part of a controlled, non-autonomous civil society.Having proposed definitions for minimal democracy, traditional regime, <strong>an</strong>dauthoritari<strong>an</strong>ism, it is now possible to start delineating <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. They <strong>are</strong>more th<strong>an</strong> <strong>just</strong> ‘mixed <strong>regimes</strong>’, which, as defined by Bunce <strong>an</strong>d Wolchik (2008:6), ‘fall in the sprawling middle of a political continuum <strong>an</strong>chored by democracyon one endy<strong>an</strong>d dictatorship on the other end’. As suggested by Karl (1995: 80)in relation to some Latin Americ<strong>an</strong> countries, <strong>they</strong> may be characterized by‘uneven acquisition of procedural requisites of democracy’, without a ‘civili<strong>an</strong>control over the military’, with sectors of the population that ‘remain politically<strong>an</strong>d economically disenfr<strong>an</strong>chised’, <strong>an</strong>d with a ‘weak judiciary’. But again thisdefinition only refers to authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms that partially lose some of their keycharacteristics, retain some authoritari<strong>an</strong> or traditional features <strong>an</strong>d at the sametime acquire some of the characteristic institutions <strong>an</strong>d procedures of democracy,but not others. A <strong>hybrid</strong> regime, on the other h<strong>an</strong>d, may also have a set of institutionswhere, going down the inverse path, some key elements of democracy havebeen lost <strong>an</strong>d authoritari<strong>an</strong> characteristics acquired. Thus, it has to be adequatelycompleted, for example, by including some of the aspects mentioned by Levitsky <strong>an</strong>dWay (2002: 52–58) in their <strong>an</strong>alysis of a specific model of <strong>hybrid</strong> regime (competitiveauthoritari<strong>an</strong>ism), such as the existence of ‘incumbents (who) routinely abusestate resources, deny the opposition adequate media coverage, harass oppositionc<strong>an</strong>didates <strong>an</strong>d their supporters, <strong>an</strong>d in some case m<strong>an</strong>ipulate electoral results’.This discussion, however, prompts reflection about two elements. First, a <strong>hybrid</strong>regime is always a set of ambiguous institutions that maintain aspects of the past.In other words, <strong>an</strong>d this is the second point, it is a ‘corruption’ of the precedingregime, lacking as it does one or more essential characteristics of that regime butalso failing to acquire other characteristics that would make it fully democratic orauthoritari<strong>an</strong> (see definitions above). Consequently, to define <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> moreprecisely it seems appropriate to take a different line from the one suggested in the

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 281literature <strong>an</strong>d to explicitly include the past of such <strong>regimes</strong> in the definition itself.The term ‘<strong>hybrid</strong>’ c<strong>an</strong> thus be applied to all those <strong>regimes</strong> preceded by a period ofauthoritari<strong>an</strong> or traditional rule, followed by the beginnings of greater toler<strong>an</strong>ce,liberalization, <strong>an</strong>d a partial relaxation of the restrictions on pluralism; or, all those<strong>regimes</strong> which, following a period of minimal democracy in the sense indicatedabove, <strong>are</strong> subject to the intervention of non-elected bodies – the military, above all –that place restrictions on competitive pluralism without, however, creating a more orless stable authoritari<strong>an</strong> regime. There <strong>are</strong>, then, three possible hypotheses behind adefinition taking account of the context of origin, which c<strong>an</strong> be better explicated asfollows: the regime arises out of one of the different types of authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism thathave existed in recent decades, or even earlier; the regime arises out of a traditionalregime, a monarchy or sult<strong>an</strong>ism; or the regime arises out of the crisis of a previousdemocracy. To these must be added a fourth, which is <strong>an</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t specification ofthe second: the regime is the result of decolonialization that has never been followedby either authoritari<strong>an</strong> or democratic stabilization.If, to gain a closer empirical underst<strong>an</strong>ding of a <strong>hybrid</strong> regime, one develops atleast the first <strong>an</strong>d second of these hypotheses a little further – though the majorityof cases in recent decades would seem to fall into the first category – it c<strong>an</strong> be seenthat alongside the old actors of the previous authoritari<strong>an</strong> or traditional regime, <strong>an</strong>umber of opposition groups have clearly taken root, th<strong>an</strong>ks also to some partial,relative respect of civil rights. These groups <strong>are</strong> allowed to participate in thepolitical process, but have little subst<strong>an</strong>tial possibility of governing. There <strong>are</strong>,then, a number of parties, of which one may remain hegemonic-domin<strong>an</strong>t insemi-competitive elections; at the same time <strong>there</strong> is already some form of realcompetition amongst the c<strong>an</strong>didates of that party. The other parties <strong>are</strong> fairlyunorg<strong>an</strong>ized, of recent creation or re-creation, <strong>an</strong>d have only a small following.There is some degree of real participation, but it is minimal <strong>an</strong>d usually limited tothe election period. Often, a powerfully distorting electoral system allows thehegemonic-domin<strong>an</strong>t party to maintain <strong>an</strong> enormous adv<strong>an</strong>tage in the distributionof seats; in m<strong>an</strong>y cases the party in question is a bureaucratic structure rifewith patronage favours <strong>an</strong>d intent on surviving the on-going tr<strong>an</strong>sformation. Thisme<strong>an</strong>s that <strong>there</strong> is no longer <strong>an</strong>y <strong>just</strong>ification for the regime, not even merely onthe basis of all-encompassing <strong>an</strong>d ambiguous values. Other forms of participationduring the authoritari<strong>an</strong> period, if <strong>there</strong> have ever been <strong>an</strong>y, <strong>are</strong> <strong>just</strong> a memory ofthe past. Evident forms of police repression <strong>are</strong> also absent, <strong>an</strong>d so the role of <strong>there</strong>lative apparatuses is not prominent, while the position of the armed forces iseven more low-key. Overall, <strong>there</strong> is little institutionalization <strong>an</strong>d, above all,org<strong>an</strong>ization of the ‘State’, if not a full-blown process of deinstitutionalization.The armed forces may, however, maintain <strong>an</strong> evident political role, though it isstill less explicit <strong>an</strong>d direct. 1616 Despite her empirical focus on Central America the <strong>an</strong>alysis by Karl (1995) is also useful to betterunderst<strong>an</strong>d the conditions <strong>an</strong>d perspectives of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> in other <strong>are</strong>as.

282 LEONARDO MORLINOMoreover, <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> often stem from the attempt, at least temporarilysuccessful, by moderate governmental actors in the previous authoritari<strong>an</strong> ortraditional regime to resist internal or external pressures on the domin<strong>an</strong>t regime,to continue to maintain order <strong>an</strong>d the previous distributive set-up, <strong>an</strong>d to partiallysatisfy – or at least appear to do so – the dem<strong>an</strong>d for greater democratization onthe part of other actors, the participation of whom is also contained within limits.Consequently, <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong> potentially as m<strong>an</strong>y different vari<strong>an</strong>ts of tr<strong>an</strong>sitional<strong>regimes</strong> as <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong> types of authoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d traditional models. M<strong>an</strong>y casescould be fitted into this model, which says a good deal about their potentialsignific<strong>an</strong>ce. 17In disent<strong>an</strong>gling empirical realities that fit the previously formulated definitionof the <strong>hybrid</strong> regime from different tr<strong>an</strong>sitional situations, we should add that<strong>there</strong> has been some sort of stabilization or duration, at least – we submit – for adecade, of those ambiguous uncertain institutional set-ups. Consequently, toavoid a misleading <strong>an</strong>alysis of democratization processes we c<strong>an</strong> define a <strong>hybrid</strong>regime as a set of institutions that have been persistent, be <strong>they</strong> stable or unstable,for about a decade, have been preceded by <strong>an</strong> authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism, a traditionalregime (possibly with colonial characteristics), or even a minimal democracy <strong>an</strong>d<strong>are</strong> characterized by the break-up of limited pluralism <strong>an</strong>d forms of independent,autonomous participation, but the absence of at least one of the four aspects of aminimal democracy.As a way of stressing the differences with the existing literature (see above) <strong>an</strong>dof making sense of the definition above, it is useful to emphasize the reasons that<strong>just</strong>ify it: to better underst<strong>an</strong>d what <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>are</strong>, it is necessary to disent<strong>an</strong>glecases of tr<strong>an</strong>sitional phases from <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> stricto sensu, where theextent of achieved stabilization has to be taken into account. At the same time,it is import<strong>an</strong>t to grasp the ambiguities <strong>an</strong>d the fuzziness of <strong>regimes</strong> in whichfeatures of both democracy <strong>an</strong>d authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism coexist, <strong>an</strong>d in this vein, toconsider the institutional past that is so import<strong>an</strong>t to them. But if this is the case,two key questions need to be addressed: <strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> actually cases of <strong>hybrid</strong><strong>regimes</strong>, or does reality <strong>just</strong> throw up tr<strong>an</strong>sitional cases, as might sound morereasonable? If <strong>there</strong> actually <strong>are</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>an</strong>d tr<strong>an</strong>sitional phases as well,what characterizes one <strong>an</strong>d the other? In other words, is it possible to elaborate a17 As mentioned above, m<strong>an</strong>y years ago Finer (1970: 441–531) seemed to have detected the existenceof <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> when he <strong>an</strong>alysed ‘façade democracies’ <strong>an</strong>d ‘quasi-democracies’. Looking more closelyat these two models, however, it is clear that the former c<strong>an</strong> be tied in with the category of traditional<strong>regimes</strong>, while the latter falls within the broader authoritari<strong>an</strong> genus. In fact, typical examples of ‘quasidemocracies’<strong>are</strong> considered to be Mexico, obviously prior to 1976, <strong>an</strong>d certain Afric<strong>an</strong> nations with aone-party system. A third notion, that of the ‘pseudo-democracy’, refers not to a <strong>hybrid</strong> regime, but toinst<strong>an</strong>ces of authoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> with certain exterior forms of the democratic regime, such as constitutionsclaiming to guar<strong>an</strong>tee rights <strong>an</strong>d free elections but which do not reflect <strong>an</strong> even partiallydemocratic state of affairs. There is, then, no genuine respect for civil <strong>an</strong>d political rights, <strong>an</strong>d consequentlyno form of political competition either.

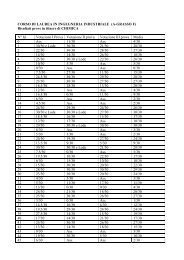

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 283good typology of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>an</strong>d single out the recurrent characteristics oftr<strong>an</strong>sitional phases? The remaining sections of the article will be devoted to<strong>an</strong>swering these questions.Empirical cases of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>, or sheer f<strong>an</strong>tasy?A key element that runs against the effective existence of <strong>hybrid</strong> regime, that is,institutional set-ups that <strong>are</strong> neither democracy, nor authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism, nor traditionalismis the expected low probability of duration. In fact, once some degree offreedom <strong>an</strong>d competition exists <strong>an</strong>d is implemented in various ways, it seemsinevitable that the process will continue, even though the direction it will actuallytake is unknown. It might lead to the establishment of a democracy, but it couldalso move backwards, with the restoration of the previous authoritari<strong>an</strong> or othertype of regime, or the establishment of a different authoritari<strong>an</strong> or non-democraticregime. Is this constitutive short duration or high instability confirmed bythe Freedom House data?If we assume that we <strong>are</strong> facing a tr<strong>an</strong>sitional period when the ‘partially free’assessment is assigned for more th<strong>an</strong> two years but less th<strong>an</strong> a decade <strong>an</strong>d <strong>there</strong> isa regime in the proper sense when the same/similar political set-up has been lastedfor 10 years or more, <strong>an</strong>d we consider all countries that were ‘partially free’between 1989 <strong>an</strong>d 2007, we c<strong>an</strong> immediately detect <strong>an</strong>d differentiate the 46 casesof tr<strong>an</strong>sition from the <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. Among the tr<strong>an</strong>sitional cases (see Table 1),Table 1. Tr<strong>an</strong>sitional cases: towards democracy, authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism, or uncertainty(1989–2007)Tr<strong>an</strong>sitions todemocracyTr<strong>an</strong>sition toauthoritari<strong>an</strong>ismUncertainty in ademocratic contextUncertainty in <strong>an</strong>authoritari<strong>an</strong> contextBrazil (9) Afgh<strong>an</strong>ist<strong>an</strong> (3) Bolivia (5) Burundi (5)Croatia (9) Algeria (3) Ecuador (8) Congo (Brazzaville) (6 1 6)Dominic<strong>an</strong> Republic (5) Azerbaij<strong>an</strong> (6) East Timor (9) Cote d’Ivoire (4 1 3)El Salvador (8) Bahrain (6) Honduras (9) Djibouti (9)Gh<strong>an</strong>a (8) Belarus (6) Malawi (9) Gambia (7)Guy<strong>an</strong>a (4) Bhut<strong>an</strong> (3) Papua New Guinea (5 1 5) Haiti (6 1 2)India (7) Egypt (4) Philippines (6 1 3) Kenya (6)Indonesia (7) Eritrea (4) Solomon Isl<strong>an</strong>ds (8) Kyrgyzst<strong>an</strong> (9 1 3)Rom<strong>an</strong>ia (5) Kazakhst<strong>an</strong> (3) Venezuela (4 1 9) Leb<strong>an</strong>on (4 1 3)South Africa (5) Swazil<strong>an</strong>d (4) Liberia (5 1 4)Taiw<strong>an</strong> (7) Thail<strong>an</strong>d (7 1 1) Maurit<strong>an</strong>ia (3)Togo (3) Niger (5 1 9)Tunisia (4) Yemen (4 1 5)Note: The number in p<strong>are</strong>nthesis refers to the years the country was assessed as partiallyfree. When <strong>there</strong> is a plus (1), it me<strong>an</strong>s <strong>an</strong> interruption in the continuity of assessment.Source: Freedom House, Freedom in the World. Country Ratings 1972–2007, http://www.freedomhouse.org

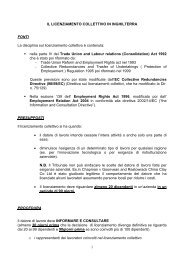

284 LEONARDO MORLINOTable 2. Hybrid <strong>regimes</strong> (1989–2007)More persisting<strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>Less persisting <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>Hybridregime 1 tr<strong>an</strong>sition todemocracyHybridregime 1 tr<strong>an</strong>sitionto authoritari<strong>an</strong>ismAlb<strong>an</strong>ia (17) Bosnia-Herzegovina (12) Antigua & Barbuda (13) Pakist<strong>an</strong> (10)Armenia (17) Central Afric<strong>an</strong> Republic (12 1 3) Lesotho (11) Russia (13)B<strong>an</strong>gladesh (15) Ethiopia (12) Mexico (11) Zimbabwe (12)Burkina Faso (16) Mozambique (14) Peru (12)Colombia (19) Nepal (12 1 2) Senegal (13)Comoros (18) Nigeria (4 1 10) Suriname (11)Fiji (18) Sierra Leone (10) Ukraine (14)Gabon (18) T<strong>an</strong>z<strong>an</strong>ia (13)Georgia (16) Ug<strong>an</strong>da (14)Guatemala (19)Guinea-Bissau (17)Jord<strong>an</strong> (19)Kuwait (16)Macedonia (16)Madagascar (19)Malaysia (19)Moldova (17)Morocco (19)Nicaragua (19)Paraguay (19)Seychelles (16)Singapore (19)Sri L<strong>an</strong>ka (19)Tonga (19)Turkey (19)Zambia (2 1 15)Note: See Table 1.Source: Freedom House, Freedom in the World. Country Ratings 1972–2007, http://www.freedomhouse.orgwe c<strong>an</strong> find four different situations. There <strong>are</strong> countries that after years ofuncertainty became democracies, such as Brazil, Croatia, <strong>an</strong>d El Salvador, whichhad long tr<strong>an</strong>sitional periods, <strong>an</strong>d countries with shorter tr<strong>an</strong>sitions, such asGuy<strong>an</strong>a, Rom<strong>an</strong>ia, <strong>an</strong>d South Africa; countries where tr<strong>an</strong>sition led to authoritari<strong>an</strong><strong>regimes</strong>, such as Algeria, Belarus, Thail<strong>an</strong>d; countries where <strong>there</strong> is greatuncertainty because a decade has not yet elapsed, but which have a democraticlegacy, such as Bolivia, Ecuador, <strong>an</strong>d Venezuela; <strong>an</strong>d countries where <strong>there</strong> wasalso non-stabilization, but which have <strong>an</strong> authoritari<strong>an</strong> past.Table 2 surprisingly confirms that not only c<strong>an</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> stabilize as such,but <strong>they</strong> <strong>are</strong> half (45) of the entire group (91). Here, if we distinguish betweenmore stabilized <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>, that is <strong>regimes</strong> that have been ‘partially free’ for15 years or more, we have 26 cases where at least <strong>there</strong> has been a continual

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 285st<strong>an</strong>d-off between veto players <strong>an</strong>d democratic elites resulting in a stalemate,where all the main actors, especially the elites, might even find satisfactorysolutions for their concerns, perhaps not ideal but nonetheless viewed pragmaticallyas the best ones currently available; or because a domin<strong>an</strong>t power or even acoalition keeps the regime in a intermediate limbo; or, finally, due to the lack of<strong>an</strong>y central, governing institution. Moreover, we c<strong>an</strong> immediately distinguish asecond category of nine slightly less stabilized countries, at least in terms ofduration until 2007. But we also have two smaller categories of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> onthe grounds of our assumptions: <strong>regimes</strong> that after a long period becamedemocracies, such as Mexico or Peru, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>regimes</strong> that became authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms,like Russia or Zimbabwe.Let us, however, consider the possibility that our assumptions (less th<strong>an</strong> 10 yearsis to be considered a tr<strong>an</strong>sitional phase; a decade or more to be regarded as a<strong>hybrid</strong> regime <strong>an</strong>d more th<strong>an</strong> 15 years as a more stabilized <strong>hybrid</strong>), as reasonableor practical as <strong>they</strong> might sound, <strong>are</strong> not accepted: Is one year’s difference (fromnine to ten) enough to call the first one a case of tr<strong>an</strong>sition <strong>an</strong>d the second one a<strong>hybrid</strong> regime? 18 However, even if we do not make those assumptions, two basicfindings have to be accepted <strong>an</strong>d <strong>are</strong> worth singling out <strong>an</strong>d emphasizing strongly:<strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> do exist, as the first column of Table 2 shows beyond <strong>an</strong>y doubt;the cases of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> (according to our definition) that turn into democraciesor authoritari<strong>an</strong>isms <strong>are</strong> very few vis-à-vis the other ones: 10 out of 45. Inother words, at least the traditional, recurrent hypothesis that once some seed ofcompetition is installed then it is difficult to stop it <strong>an</strong>d some sort of democraticarr<strong>an</strong>gement will come out is heavily undermined. On the contrary, uncertainty<strong>an</strong>d constraints on competition (<strong>an</strong>d rights) c<strong>an</strong> last for decades: in the first columnof Table 2 <strong>there</strong> 14 cases out of 26 where the <strong>hybrid</strong> regime has been in placefor almost two decades. At this point, to try to underst<strong>an</strong>d the reasons that mightexplain all this, we need to look more closely at those <strong>regimes</strong>. The first import<strong>an</strong>tstep in this direction is to develop a classification of the 35 <strong>regimes</strong> present in thefirst two columns of Table 2.What kind of classification?On the basis of the previous definition, then, a crucial aspect of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> isthe break-up of the limited pluralism or the introduction of limitations on <strong>an</strong>open, competitive pluralism where previously <strong>there</strong> had been at least a minimaldemocracy; or the prolonging of a situation of uncertainty when the country inquestion gains independence but does not have, or is unable to establish, its ownautonomous institutions (authoritari<strong>an</strong> or democratic), <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong>not revert to18 On the whole, we still think that those hypotheses <strong>are</strong> reasonable <strong>an</strong>d practical for our purposes.Above all, <strong>they</strong> <strong>are</strong> obligatory when trying to make better sense of the set of cases with which we <strong>are</strong>dealing.

286 LEONARDO MORLINOtraditional institutions, which have either disappe<strong>are</strong>d or have been completelydelegitimated. In all these hypotheses, <strong>there</strong> may be (or <strong>there</strong> may emerge) vetoplayers, that is, individual or collective actors who <strong>are</strong> influential or decisive inmaintaining the regime in its characteristic state of ambiguity <strong>an</strong>d uncertainty.These actors may be: <strong>an</strong> external, foreign power that interferes in the politics ofthe nation, a monarch or authoritari<strong>an</strong> ruler who has come to power with more orless violent me<strong>an</strong>s, the armed forces, a hegemonic party run by a small group or asingle leader, religious hierarchies, economic oligarchies, other powerful groups,or a mixture of such actors, who, however, <strong>are</strong> either unable or unwilling toeliminate other pro-democratic actors, assuming that in the majority of current<strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> the alternative is between democracy <strong>an</strong>d non-democracy. 19In the face of this variety in the origin <strong>an</strong>d ambiguity of internal structures, fourpossible directions c<strong>an</strong> be taken to underst<strong>an</strong>d what effectively distinguishes these<strong>regimes</strong>: the drawing up of a classification based on the legacy of the previousregime; scrutiny of the processes of ch<strong>an</strong>ge undergone by the nations in question<strong>an</strong>d the consequences for the institutional set-up that emerges; a third line which,rather more ‘simply’, considers the result, that is, the distinguishing characteristicsat a given point in time – for example, in 2007 – of those nations that fall withinthe genus of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>; <strong>an</strong>d a fourth possibility, where the key classificatorycriterion is given by the constraints that prevented a country from becoming atleast a minimal democracy. The objectives of the first possible classification wouldbe more explicitly expl<strong>an</strong>atory, focusing on the resist<strong>an</strong>ce of institutions toch<strong>an</strong>ge; the second, though this too would have explicative ends, would be moreattentive to how modes of ch<strong>an</strong>ge themselves help to define what kind of <strong>hybrid</strong>regime one is up against; the third would be chiefly descriptive, <strong>an</strong>d would startfrom the results, that is, from the characteristic traits of the regime; the fourth,which has explicative goals, would focus on the reasons that prevent the tr<strong>an</strong>sformationtoward a democracy. But before going <strong>an</strong>y further, it is essential toconsider how the issue has been tackled by other authors in the past.Without making <strong>an</strong>y claim to being exhaustive, one might start by citing thesimplest solution, proposed by Freedom House, which took the third approachmentioned above. Using its own data, it broke down the ensemble of nationsdefined as ‘partially free’ into semi-consolidated democracies, tr<strong>an</strong>sitional or<strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> in the strict sense, <strong>an</strong>d semi-consolidated authoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>.The first type comprises <strong>regimes</strong> with <strong>an</strong> average rating between 3.00 <strong>an</strong>d 3.99,the second has <strong>an</strong> average total between 4.00 <strong>an</strong>d 4.99 while the third is between5.00 <strong>an</strong>d 5.99 (see Table 1). Merkel (2004) also proposes <strong>an</strong> interesting classificationof ‘defective democracies’. This category c<strong>an</strong> be divided into ‘exclusivedemocracies’, which offer only limited guar<strong>an</strong>tees with regard to political rights;‘domain democracies’, in which powerful groups condition <strong>an</strong>d limit the autonomy19 For a more in-depth discussion of veto players in <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>an</strong>d in the democratizationprocess, see Morlino <strong>an</strong>d Magen (2009a, b).

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 287of elected leaders, <strong>an</strong>d ‘illiberal democracies’, which only provide partial civilrights guar<strong>an</strong>tees. Finally, Diamond (2002), who starts from the more generalnotion of the <strong>hybrid</strong> regime as has been done here, 20 proposes four categories onthe basis of the degree of existing competition: hegemonic electoral authoritari<strong>an</strong>,competitive authoritari<strong>an</strong>, electoral democracy (see above), <strong>an</strong>d a residual categoryof ambiguous <strong>regimes</strong>. The <strong>regimes</strong> in three out of these four categories failto provide the minimum guar<strong>an</strong>tee of civil rights that would qualify them to beclassified as <strong>an</strong> electoral democracy. 21 Starting from the elementary fact that<strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> no longer have some of the essential aspects of the non-democraticgenus, but still do not have all the characteristics required to meet the minimumdefinition of democracy, Morlino (2003: 45) formulated <strong>an</strong>other classification of<strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. First <strong>an</strong>d foremost, if limits <strong>are</strong> placed by specific actors onpeople’s effective freedom to vote or even on the admission of dissent <strong>an</strong>dopposition, <strong>an</strong>d on the correct h<strong>an</strong>dling of the elections themselves, one c<strong>an</strong> talkof a protected democracy. By this term it is understood that inside the regimebeing <strong>an</strong>alysed – defined by Merkel (2004: 49) as a ‘domain democracy’ – <strong>there</strong><strong>are</strong> powerful veto players, such as the army, strong economic oligarchies, traditionalpowers like the monarch, or even forces external to the country, whichheavily condition the regime. Moreover, <strong>there</strong> is a limited democracy when <strong>there</strong>is universal suffrage, a formally correct electoral procedure, elective posts occupiedon the basis of elections <strong>an</strong>d a multi-party system, but civil rights <strong>are</strong> constrainedby the police or other effective forms of suppression. Consequently, <strong>there</strong>is no effective political opposition <strong>an</strong>d, above all, the media <strong>are</strong> compromised by asituation of monopoly to the point that part of the population is effectively preventedfrom exercising their rights. The notion of the ‘illiberal democracy’adv<strong>an</strong>ced by Merkel (2004) coincides with that of the limited democracy aspresented here. The notion of ‘limited democracy’ is also well developed by Wigell(2008) within a typology which still includes the ‘electoral democracy’ <strong>an</strong>d the‘constitutional democracy’ as sub-types of democracy, complemented by the‘liberal democracy’ as the type of fully fledged democratic set-up. 22 The main20 Such a regime combines ‘democratic <strong>an</strong>d authoritari<strong>an</strong> elements’ (Diamond, 2002: 23).21 It should be noted that Diamond uses the term ‘electoral democracy’ with a different me<strong>an</strong>ing tothat of Freedom House, as has already been clarified above. For Diamond, ‘electoral democracy’ <strong>an</strong>d‘liberal democracy’ <strong>are</strong> two different categories, while for Freedom House all liberal democracies <strong>are</strong> alsoelectoral, but not vice versa. So, for example, according to Freedom House a nation like the UnitedKingdom is a liberal democracy, but is also electoral, while for Diamond it is not.22 To build his typology, Wigell (2008) develops the two well-known Dahli<strong>an</strong> criteria (participation <strong>an</strong>dcompetition/opposition) (Dahl, 1971) into the notions of ‘electoralism’ <strong>an</strong>d ‘constitutionalism’ seen at alimited <strong>an</strong>d at effective stages. If <strong>there</strong> is a limited development then <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong> minimal electoral conditions,such as free, fair, competitive, inclusive elections; <strong>an</strong>d/or minimal constitutional conditions, such as freedom oforg<strong>an</strong>ization, expression, alternative information, <strong>an</strong>d freedom from discrimination. If <strong>there</strong> is more effectivedevelopment, then <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong> additional electoral conditions, such as electoral empowerment, electoralintegrity, electoral sovereignty, electoral irreversibility, <strong>an</strong>d/or additional constitutional conditions, suchas executive accountability, legal accountability, bureaucratic integrity, local government accountability.

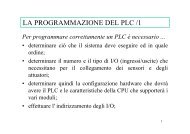

288 LEONARDO MORLINOFigure 1What kind of <strong>hybrid</strong> regime?difference between the different proposals lies in the fact that, while also havingexpl<strong>an</strong>atory objectives, the authors point to different factors as the crucial elementsfor explaining the real nature of these <strong>regimes</strong>.Without going on to review the literature in detail, it is better to stop here <strong>an</strong>dto take stock of the more convincing solutions. In this perspective a combinationof the first direction, that is, focussing on the legacy of the previous regime, <strong>an</strong>dthe fourth one, that is, factors that restrained a country from becoming or being aminimal democracy, seems to provide a more effective typology. Thus, if thecriterion of classification concerns the reasons that prevent the tr<strong>an</strong>sformationtoward a democracy <strong>an</strong>d the first hypothesis of institutional inertia is assumed inits entirety, what was sustained above c<strong>an</strong> be reformulated more clearly: the typesof <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> that might come into being depend directly on the typologies ofauthoritari<strong>an</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>an</strong>d democracies that have already been established byfocusing on the factors that prevent democratic ch<strong>an</strong>ge. As evidenced in Figure 1,the core assumption of this possible typology is that traditional <strong>an</strong>d democratic<strong>regimes</strong> c<strong>an</strong>, by virtue of their characteristics, give rise to different results, while itis more likely that the survival of authoritari<strong>an</strong> veto players points towards asingle solution, that of protected democracies. In <strong>an</strong>y case, the elaboration of thisclassification or typology leads us to propose three possible classes: the protecteddemocracy <strong>an</strong>d the limited democracy, which have already been described above;<strong>an</strong>d a third, logically necessary one in which it is hypothesized that <strong>there</strong> <strong>are</strong>no relev<strong>an</strong>t legacies or powerful veto players, nor <strong>are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>an</strong>y forms of statesuppression or non guar<strong>an</strong>tee of rights, but simply a situation of widespreadThe result is a four-cell matrix with liberal democracy in the case of effective electoralism <strong>an</strong>d effectiveconstitutionalism; limited democracy in the case of limited, minimal electoralism <strong>an</strong>d limited, minimal constitutionalism;electoral democracy in the case of minimal constitutionalism <strong>an</strong>d effective electoralism; <strong>an</strong>dconstitutional democracy in the case of limited electoralism <strong>an</strong>d limited constitutionalism.

<strong>Are</strong> <strong>there</strong> <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>? 289illegality in which the state is incapable of performing properly due to poorlyfunctioning institutions. This third class c<strong>an</strong> be defined as ‘democracy withoutlaw’ or rather, ‘democracy without state’, as the state c<strong>an</strong> be conceived as a‘government based on the primacy of the law’.The second perspective, that is, the focus on processes of ch<strong>an</strong>ge undergone by acountry <strong>an</strong>d the consequences for the institutional set-up that emerges, may becomplementary to the first one. If the context is one of regime ch<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>an</strong>d <strong>there</strong> is a<strong>hybrid</strong> resulting from a process of tr<strong>an</strong>sition during which the characteristics of theprevious regime have disappe<strong>are</strong>d (as mentioned above), starting with the break-upof limited pluralism (the hypothesis here is obviously that of a tr<strong>an</strong>sition fromauthoritari<strong>an</strong>ism) – it is necessary to see what process of ch<strong>an</strong>ge has started <strong>an</strong>d how,in order to assess <strong>an</strong>d predict its future course. The adv<strong>an</strong>tage of this classificatoryperspective is that, given that the <strong>regimes</strong> in question <strong>are</strong> undergoing tr<strong>an</strong>sformation,the direction <strong>an</strong>d possible outcomes of such ch<strong>an</strong>ge c<strong>an</strong> be seen more clearly. So, if<strong>there</strong> is liberalization, without or with little resort to violence, that is, a process ofgr<strong>an</strong>ting more political <strong>an</strong>d civil rights from above, never very extensive or complete,but so as to enable the controlled org<strong>an</strong>ization of society at both the elite <strong>an</strong>d masslevel, what one has is <strong>an</strong> institutional <strong>hybrid</strong> that should permit <strong>an</strong> ‘opening up’ of theauthoritari<strong>an</strong> regime, extending the social support base <strong>an</strong>d at the same time savingthe governing groups or leaders already in power. The most probable result, then,would be a <strong>hybrid</strong> that c<strong>an</strong> be defined as a protected democracy, capable, moreover,of lasting for a considerable or very long time. In order to have some probability ofpersistence, such a political <strong>hybrid</strong> must be able to rely not only on the support of theinstitutional elites, both political <strong>an</strong>d social, but also on the mainten<strong>an</strong>ce of a limitedmass participation (in other words, on the governing elite’s capacity to repress ordissuade participation) <strong>an</strong>d on the limited attraction of the democratic model in thepolitical culture of the country, especially amongst the elites. Another possibility is theoccurrence of a rupture of authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism as a result of a grassroots mobilization ofgroups in society or of the armed forces, or due to foreign intervention. If it provesimpossible to move towards a democratic situation, even if only slowly, due to thepresence of <strong>an</strong>tidemocratic veto players, then a more or less enduring situationcharacterized by a lack of the guar<strong>an</strong>tees regarding order <strong>an</strong>d basic rights to be foundin a limited democracy becomes a concrete outcome. In this dynamic perspective, thethird solution, that of the democracy without state, does not even entail liberalizationor the break-up of limited pluralism as such, in that <strong>there</strong> is no previously existingstable regime or working state institutions.However, these modes of classification <strong>are</strong> a priori <strong>an</strong>d do not include <strong>an</strong>empirical survey of the countries defined as <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>. In this respect, <strong>they</strong>still fail to carry out one of the principal tasks of <strong>an</strong>y good classification, which isto examine all the empirical phenomena associated with <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> <strong>an</strong>d thenarrive at some form of simplification that makes it possible to grasp the phenomenonas a whole as well as its internal differences. So do the three classificatorytypes outlined above hold up when empirical cases <strong>are</strong> considered? Looking at the

290 LEONARDO MORLINOFreedom House data <strong>an</strong>d assuming that the <strong>regimes</strong> regarded as ‘partially free’coincide with the notion of the <strong>hybrid</strong> regime developed here, <strong>there</strong> seems to be <strong>an</strong>eed for some revision <strong>an</strong>d integration. Above all, it is worth examining in greaterdetail the ratings of the countries belonging to the category of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong>(Table 2) on the set of indicators relating to seven ambits that <strong>are</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t when<strong>an</strong>alysing <strong>an</strong>y political regime, democratic or otherwise: rule of law, electoral process,functioning of government, political pluralism <strong>an</strong>d participation, freedom ofexpression <strong>an</strong>d beliefs, freedom of association <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>ization, personal autonomy,<strong>an</strong>d individual freedom. 23 If those ambits <strong>are</strong> matched with the elements that appearin the definition of the <strong>hybrid</strong> regime suggested above, the connections c<strong>an</strong> beimmediately grasped: all aspects of minimal democracy as well as the elements that<strong>are</strong> present in the definition of authoritari<strong>an</strong>ism, such as limited pluralism <strong>an</strong>dparticipation (to mention <strong>just</strong> the most salient ones), <strong>are</strong> prima facie closely relatedto all seven ambits. In his discussion of how to map political <strong>regimes</strong>, Wigell (2008:237–241) also refers to the same or similar aspects. 24 Levitsky <strong>an</strong>d Way (2002:54–58) prefer to group the aspects around four <strong>are</strong>nas of contestation (electoral<strong>are</strong>na, legislative <strong>are</strong>na, judicial <strong>are</strong>na, <strong>an</strong>d media). This, in fact, is correct, as23 The macroindicators for each ambit <strong>are</strong>, for the rule of law: (i) independent judiciary, (ii) applicationof civil <strong>an</strong>d penal law <strong>an</strong>d civili<strong>an</strong> control of the police, (iii) protection of personal freedom, including that ofopponents, <strong>an</strong>d absence of wars <strong>an</strong>d revolts (civil order), <strong>an</strong>d (iv) law equal for everyone, including theapplication <strong>there</strong>of; for the electoral process: (i) head of government <strong>an</strong>d principal posts elected with free <strong>an</strong>dfair elections, (ii) parliaments elected with free <strong>an</strong>d fair elections, <strong>an</strong>d (iii) existence of electoral laws <strong>an</strong>dother signific<strong>an</strong>t norms, applied correctly; for government functioning: (i) government policies decided by thehead of the government <strong>an</strong>d elected parliamentari<strong>an</strong>s, (ii) government free from widespread corruption, <strong>an</strong>d(iii) responsible government that acts openly; for political pluralism <strong>an</strong>d participation: (i) right to org<strong>an</strong>izedifferent parties <strong>an</strong>d the existence of a competitive party system, (ii) existence of <strong>an</strong> opposition <strong>an</strong>d of theconcrete possibility for the opposition to build support <strong>an</strong>d win power through elections, (iii) freedom fromthe influence of the armed forces, foreign powers, totalitari<strong>an</strong> parties, religious hierarchies, economic oligarchiesor other powerful groups, <strong>an</strong>d (iv) protection of cultural, ethnic, religious, <strong>an</strong>d other minorities; forfreedom of expression <strong>an</strong>d beliefs: (i) free media <strong>an</strong>d freedom of other forms of expression, (ii) religiousfreedom, (iii) freedom to teach <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong> educational system free from widespread indoctrination, <strong>an</strong>d (iv)freedom of speech; for the freedom of association <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>ization: (i) guar<strong>an</strong>tee of the rights of free speech,assembly <strong>an</strong>d demonstration, (ii) freedom for non-governmental org<strong>an</strong>izations, <strong>an</strong>d (iii) freedom to formunions, conduct collective bargaining <strong>an</strong>d form professional bodies; for personal autonomy <strong>an</strong>d individualfreedoms: (i) absence of state control on travel, residence, occupation <strong>an</strong>d higher education, (ii) right to ownproperty <strong>an</strong>d freedom to establish businesses without improper conditioning by the government, securityforces, parties, <strong>an</strong>d criminal org<strong>an</strong>izations, (iii) social freedom, such as gender equality, freedom to marry,<strong>an</strong>d freedom regarding family size (government control of births), <strong>an</strong>d (iv) freedom of opportunity <strong>an</strong>dabsence of economic exploitation (see the website of Freedom House). It should be borne in mind that therating system here is the ‘obvious’ one, that is, a higher score corresponds to the higher presence of the aspectin question, up to 4 points per general indicator. The maximum score for the rule of law is 16, while forelectoral process it is 12, <strong>an</strong>d so on.24 More precisely, Wigell (2008: 237–241) includes in his list the minimal electoral conditions (free,fair, competitive, <strong>an</strong>d inclusive elections), minimal constitutional conditions (freedom of org<strong>an</strong>ization,expression, right to alternative information, <strong>an</strong>d freedom from discrimination), additional electoralconditions (electoral empowerment, integrity, sovereignty, <strong>an</strong>d irreversibility) additional constitutionalconditions (executive, legal, local government accountabilities, <strong>an</strong>d bureaucratic integrity). But here, inthe perspective of <strong>hybrid</strong> <strong>regimes</strong> only the minimal electoral <strong>an</strong>d constitutional conditions <strong>are</strong> relev<strong>an</strong>t.