paper in English - Departamentul de Geografie

paper in English - Departamentul de Geografie

paper in English - Departamentul de Geografie

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesTHE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: NEW SETTLEMENTFRONTIERSThis period registers an element of <strong>in</strong>tegration given the grow<strong>in</strong>g strength of theHabsburg Empire, along with Prussia and Russia, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with the Partitions of Polandand the first stage <strong>in</strong> the roll<strong>in</strong>g back of the Ottoman ti<strong>de</strong>. The Habsburgs expan<strong>de</strong>d fromtheir bridgehead <strong>in</strong> northwestern Hungary to ga<strong>in</strong> control of Pannonia and Transylvania andultimately extend beyond the Carpathian crestl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>to Galicia (Figure 3). Limit<strong>in</strong>g theHabsburg monopoly was cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g Ottoman suzera<strong>in</strong>ty over Moldavia and Wallachia,<strong>de</strong>spite a brief Habsburg occupation of Oltenia - western Wallachia - dur<strong>in</strong>g 1718-39. Amilitary <strong>de</strong>fence strategy based on roads and fortresses nee<strong>de</strong>d the resources supplied byeconomic <strong>de</strong>velopment and the result was a mercantilist era of growth which eventuallygave way to private enterprise. This period therefore registers a further <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> humanpressure with some pastures converted to arable by the plough<strong>in</strong>g of high surfaces andgentle slopes, though typically along the contour. There was also excessive graz<strong>in</strong>g ofcommunal lands and some forest <strong>de</strong>terioration, accentuated by the <strong>in</strong>vasion of beechwoodby fast-grow<strong>in</strong>g species (p<strong>in</strong>e and larch) “neglect<strong>in</strong>g the natural conditions of the foresthabitats” (Pietrzak 1998, p.34).Figure 3: Political organisation: 19th century.35

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesVsetín) while <strong>in</strong> Hukvald the forestry <strong>in</strong>terest predom<strong>in</strong>ated and seasonal sheep farms wereelim<strong>in</strong>ated by the middle of the 19th century.The Habsburgs also presi<strong>de</strong>d over the growth of the iron <strong>in</strong>dustry <strong>in</strong> Galicia.Ustron - first mentioned 1305 as an episcopal estate - acquired a foundry <strong>in</strong> the 18thcentury to work up low-gra<strong>de</strong> iron ore. Meanwhile Kuznica <strong>in</strong> the Zakopane area of theTatra was engaged <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and foundry work. But s<strong>in</strong>ce virtually the entire mounta<strong>in</strong>system was now un<strong>de</strong>r the control of Vienna, the greater rhythm of commercial activity andsystematic resource exploitation can be seen more wi<strong>de</strong>ly. The greatest transformationoccurred <strong>in</strong> the Banat Mounta<strong>in</strong>s, at the southwestern extremity of the Carpathian system,where a major settlement programme followed the recovery of territory from the Turks <strong>in</strong>1699. Because of the Turkish <strong>in</strong>vasions most villages lay <strong>in</strong> narrow valleys or along spr<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>es. And as the Habsburgs ma<strong>de</strong> Banat a place of multi-ethnic Catholic colonisation,German, Hungarian and Slovak colonists (also some Bulgarians) were established on theedge of Romanian or Serb villages, with assimilation or displacement of natives to otherparts of Banat. Agricultural <strong>de</strong>velopment was largely conf<strong>in</strong>ed to the lowlands, while them<strong>in</strong>erals of the Carpathians were exploited by the ‘Banater Bergwerk-E<strong>in</strong>richtungs-Kommission’ set up <strong>in</strong> 1717. As skilled m<strong>in</strong>ers were brought from Bohemia, Styria, Tyroland Zips, a copper smelter was opened at Oraviţa <strong>in</strong> 1718 and an iron furnace Bocşafollowed <strong>in</strong> 1719; the latter expan<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong>to a large metallurgical complex on the edge of theAn<strong>in</strong>a, Dognecea and Semenic Mounta<strong>in</strong>s with the Reşiţa furnace of 1771 as the ma<strong>in</strong>element (Hill<strong>in</strong>ger & Turnock 2001) (Figure 4). Nearby <strong>in</strong> the Poiana Rusca there were<strong>in</strong>stallations at Bistra (now Oţelu Roşu) <strong>in</strong> 1795. Reference should also be ma<strong>de</strong> to the coalfirst discovered with<strong>in</strong> the woodcutt<strong>in</strong>g community of Steierdorf-An<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> 1790 and them<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustry which <strong>de</strong>veloped with the help of skilled workers from Bohemia andSlovakia.Settlement adjustments <strong>in</strong> the Romanian CarpathiansTowns like Haţeg, Sebeş and Sighetul Marmaţiei were play<strong>in</strong>g an importantcommercial role; to say noth<strong>in</strong>g of the transit traffic organised <strong>in</strong> Curtea <strong>de</strong> Argeş,Câmpulung and Râmnicu Vâlcea (Giurcăneanu 1988 p.132). However, population pressureforced people to f<strong>in</strong>d subsistence wherever it might be available and to survive with onlytenuous market l<strong>in</strong>ks. There was cont<strong>in</strong>ued movement by Romanians (known as ‘Ungureni’because there were from territory un<strong>de</strong>r Hungarian adm<strong>in</strong>istration) from Transylvania toMoldavia and Wallachia, with only spasmodic migrations <strong>in</strong> the opposite direction. Tufescu(writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 1986 <strong>in</strong> response to Hungarian claims that Romanians were mov<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>toTransylvania) tells how Habsburg appeals for Ottoman cooperation to restrict the flow outof the prov<strong>in</strong>ce produced a compromise that nevertheless enabled some 32,000 Romanians(ma<strong>in</strong>ly from the Bistriţa area) to settle <strong>in</strong> the Suceava-Solca-Câmpulung Moldovenesc-Valea Moldovei quadrilateral of Bucov<strong>in</strong>a dur<strong>in</strong>g 1747-76. But equally important wasdispersed settlement on the higher ground (Metes 1977; Popp 1942). In this way a conflicthas <strong>de</strong>veloped <strong>in</strong> rural study between a functional approach work<strong>in</strong>g through urban systemsand an ecological slant l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g rural communities to their local territorial circumstances.The latter emphasis, adopted by R.Vuia who specialised <strong>in</strong> remote rural communities of theearly 20th century (Turnock 1991b), was no doubt encouraged by the psychological aff<strong>in</strong>ityof the Romanians to pastoralism <strong>in</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>al areas through dispersed communities on thehigh surfaces committed to transhumance. Thus while some communities were able to37

David TURNOCK<strong>de</strong>velop non-agricultural activities <strong>in</strong> the market centres, an alternative strategy at a time ofpopulation growth and capitalist control of low-ground agricultural resources was tomaximise use of the higher surfaces for subsistence by establish<strong>in</strong>g permanent hamletsettlements: each represent<strong>in</strong>g a gradually-expand<strong>in</strong>g k<strong>in</strong>ship group of <strong>in</strong>dividualfarmsteads which often <strong>in</strong>volved an enclosed courtyard appropriate for sheep rear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>exposed areas subject to the <strong>de</strong>predations of wild animals, especially <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>tertime (Idu1972).Figure 4: The An<strong>in</strong>a-Reşiţa <strong>in</strong>dustrial area.38

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesforce dur<strong>in</strong>g the best part of a century: 1762-1851. Popa 1999 (p.216) has expla<strong>in</strong>ed how‘Regimentul Românesc 1 Orlat’ had a company <strong>in</strong> Haţeg which offered advantages foreducation and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g - through privileges <strong>in</strong> the relevant villages - which helped tocounter the marg<strong>in</strong>alisation of this mounta<strong>in</strong> <strong>de</strong>pression through the <strong>de</strong>parture of nobleRomanian families. However it is the northeastern Rodna Military District - later NăsăudFrontier District - that has been most extensively researched (Sotropa 1975). A total of 12Companies were formed dur<strong>in</strong>g 1762-83 with each recruited from a group of villages andthe special regime lasted until a civil adm<strong>in</strong>istration was provi<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong> 1851. Năsăud was thengranted autonomy <strong>in</strong> 1861 but this was cancelled when Hungary became responsible foradm<strong>in</strong>istration un<strong>de</strong>r the compromise (‘Ausgleich’) of 1867 between the Habsburg emperorand the Hungarians and the county (‘comitat’) of Bistriţa-Năsăud was created.Un<strong>de</strong>r military plann<strong>in</strong>g there was a consolidation of the Greek-Catholic parochialstructure and provision of a state education system through elementary ‘Trivialschulen’from 1770 and a high school (‘Şcoala Normală Superioară’) <strong>in</strong> Năsăud <strong>in</strong> 1771 (Albu1971). Medical and sanitary programmes provi<strong>de</strong>d effective barriers aga<strong>in</strong>st the spread ofplague from Moldavia <strong>in</strong> 1815 and cholera from Wallachia <strong>in</strong> 1830 (Buta & Pupeza 1994).Commerce expan<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong> a network of central places with their fairs and road systems, whilethe promotion of agriculture <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d attention to cereals, vegetables, potatoes, textileplants and fruit trees, along with stock rear<strong>in</strong>g and allocation of graz<strong>in</strong>gs (Mureşianu 2000pp.182-6). In<strong>de</strong>ed this is the basis of landhold<strong>in</strong>g today apart from some abusive transfersto non-frontier communes <strong>in</strong> the communist period. Regulation exten<strong>de</strong>d to hunt<strong>in</strong>g andfish<strong>in</strong>g as well as forestry, m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and manufactur<strong>in</strong>g; with the latter facilitated through<strong>in</strong>struction <strong>in</strong> sp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g, weav<strong>in</strong>g and full<strong>in</strong>g, and a growth of water-powered cereal mills aswell as the first ‘joagare’ <strong>in</strong> Maieru and Parva <strong>in</strong> 1766. Beer and spirits were produced <strong>in</strong>Năsăud from 1765, <strong>paper</strong> at Prundul Bârgăului from 1768 while a great lime furnace('varniţa') was built at Parva <strong>in</strong> 1777. It is also notable that settlement was consolidated sothat Nepos was transformed between 1775 and 1783 from a scattered settlement north ofthe river Someş to a compact l<strong>in</strong>ear belt along the ma<strong>in</strong> valley. In the same way Budacu <strong>de</strong>Sus emerged as an expand<strong>in</strong>g nucleated settlement complement<strong>in</strong>g the exist<strong>in</strong>g Germannucleation of Budacul Săsesc (or Budacu <strong>de</strong> Jos). New settlement occurred <strong>in</strong> the heavilyforested Ilva valley as colonists moved from Maieru and Rodna to establish dispersedcommunities at Arşiţa, Recele and Secături before consolidat<strong>in</strong>g un<strong>de</strong>r the frontier régimeas Poiana Ilvei, Magura Ilvei and Ilva Mare. From the ‘m<strong>in</strong>i-bas<strong>in</strong>s’ along this secondarymorpho-hydrographic axis the meadows and forests on the high surfaces could be morefully utilised (Mureşianu 1996).THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE RAILWAY AGEDur<strong>in</strong>g this period territorial stability, rest<strong>in</strong>g on Habsburg dom<strong>in</strong>ance, wasconsolidated through a secret treaty with Romania, although the ‘Ausgleich’ (mentionedabove) created tension through the re-emergence (albeit with<strong>in</strong> the empire) of a Hungariannation state with<strong>in</strong> a large multi-ethnic territory. The potential for growth was <strong>in</strong>creased bythe end of feudalism <strong>in</strong> the empire <strong>in</strong> 1848 (and Romania <strong>in</strong> 1864) which opened the wayfor a more unrestra<strong>in</strong>ed capitalism as the peasants now found themselves un<strong>de</strong>r a more<strong>de</strong>mand<strong>in</strong>g fiscal pressure without the same customary access to forest and graz<strong>in</strong>g land. Atthe same time, given the capitalistic rivalries of sovereign states, it can be seen that while41

David TURNOCKthe Habsburg Empire-Romanian frontier <strong>in</strong> the southeast succumbed to the technology ofthe railway age it also ga<strong>in</strong>ed an enhanced fiscal significance embarrass<strong>in</strong>g to people whohad previously crossed with m<strong>in</strong>imal formality. This review will <strong>de</strong>al with the <strong>de</strong>velop<strong>in</strong>grailway network and the consequences for <strong>in</strong>dustry and tourism. It will also argue for anorth-south contrast <strong>in</strong> <strong>de</strong>mographic pressure on land with urbanisation and emigration <strong>in</strong>the north contrast<strong>in</strong>g with some renewed rural colonisation <strong>in</strong> the south.The railway networkThe period is dom<strong>in</strong>ated by the network’s selective growth ten<strong>de</strong>ncies <strong>in</strong> thecontext of <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternational and <strong>in</strong>ter-regional exchanges. Figure 5 shows that therailway arrived late <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians. By 1880 there was a cont<strong>in</strong>uous system along theouter arc, endors<strong>in</strong>g the Medieval tra<strong>de</strong> route from Vienna to Brno, Ostrava, Kraków,Tarnów, Černivci, Roman and Galaţi; but cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to Bucharest and Turnu Sever<strong>in</strong>. Thismay be dated as follows: Vienna to Deutsch Wagram (1837); Ganserndorf (1838); Brečlav(1839); Přerov (1841); Lipník (1842); Bohum<strong>in</strong> (1847); Czechowice (1855); Dąbica(1856); Rzeszów (1858); Przeworsk (1859); Przemyśl (1860); L’viv (1861); Černivci(1866); Roman (1869); Mărăşeşti (1872) and Buzău (1881) - meet<strong>in</strong>g construction mov<strong>in</strong>gnorth from the chief towns of southern Romania. There was also a ‘cut-off’ runn<strong>in</strong>g closerto the mounta<strong>in</strong>s which was complete between Hulín (south of Preşov) and IvanoFrankivs’k, runn<strong>in</strong>g by way of Bielsko-Biała, Sanok and Stryj, by 1888. On the <strong>in</strong>ner si<strong>de</strong>of the arc Vienna was connected with Bratislava, Budapest, Miskolc, Kosice and SatuMare. But <strong>in</strong> 1880 the only l<strong>in</strong>es cross<strong>in</strong>g the mounta<strong>in</strong>s were <strong>in</strong> the north from Tarnów toKošice and L’viv to Miskolc and also from Ostrava to Košice and Miskolc and <strong>in</strong> the southfrom Ora<strong>de</strong>a, Arad and Timişoara to Cluj, Alba Iulia and Turnu Sever<strong>in</strong> respectively; alsofrom Sighişoara to Braşov to Ploieşti. The next forty years transformed the situationespecially <strong>in</strong> the Eastern Carpathians although there rema<strong>in</strong>ed a wi<strong>de</strong> gap between the l<strong>in</strong>esrunn<strong>in</strong>g south from L’viv to the Tisza at Sighetul Marmaţiei and cross<strong>in</strong>g the Romanianfrontier at Ghimeş west of Bacău. This was a weakness <strong>in</strong> the First World War whenAustro-Hungarian forces were trapped <strong>in</strong> Bucov<strong>in</strong>a by the Brussilow Offensive because itwas only through makeshift arrangements <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g a roadsi<strong>de</strong> tramway cross<strong>in</strong>g theCarpathians at 1,145m and completed <strong>in</strong> 1915 - us<strong>in</strong>g electric locomotives with petroleng<strong>in</strong>es to work the generators - that equipment could be evacuated through Suceava andBistriţa along a route close to the one that was eventually negotiated by a standard gaugerailway only <strong>in</strong> 1938 (Bellu 2000).The promotion and eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g of the Carpathian railways, which gave rise to<strong>in</strong>vestment on an unprece<strong>de</strong>nted scale, merits a whole study <strong>in</strong> itself to collate thefragments which have appeared <strong>in</strong> the epic histories of the pre-World War One period(Turnock 2001). Although the valleys provi<strong>de</strong>d obvious routeways their narrowness and<strong>in</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ation was challeng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the context of severe flood hazards. Even with morepowerful locomotives available <strong>in</strong> the later years of the century, curvature and axle loadimposed limitations and average speeds were relatively low. The caption for Figure 1summarises progress with reference to the major trans-Carpathian projects although itbeg<strong>in</strong>s with relatively local Banat scheme of 1863 (already referred to) which achieved analtitu<strong>de</strong> of 559m at Gârlişte and <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d a remarkable series of viaducts, tunnels andcutt<strong>in</strong>gs as well as a shelf on the unstable slopes of the Lişava valley (Perianu 2000). It wasa project groun<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the pressures of the Crimean War when the Habsburg authorities42

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centurieswere <strong>de</strong>sperate to get An<strong>in</strong>a coal to the Danube at Baziaş and contemplated a tunnel (‘Tunellui Stefan’) from Colovrat colliery to Lişava as the first stage (Figure 6); although this waseventually completed <strong>in</strong> 1863 by the private company Staatseisenbahngesellschaft (STEG)that took over the entire state doma<strong>in</strong> of Reşiţa <strong>in</strong> 1855 through privatisation precipitated bythe Crimean War (Graf 1997). Although the coal was subsequently redirected from theDanube to the Reşiţa furnaces, production cont<strong>in</strong>ued to be taken out over this mounta<strong>in</strong>railway which constitutes the most remarkable part of a susta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>dustrial en<strong>de</strong>avourcentral to the mo<strong>de</strong>rnisation of the Caraş-Sever<strong>in</strong> district. A cluster of shaft m<strong>in</strong>es<strong>de</strong>veloped with connections by narrow-gauge railways and un<strong>de</strong>rground tunnels to thecentral complex by the standard-gauge railway <strong>in</strong> An<strong>in</strong>a (Feneşan et al. 1991) .It was 1872 before the railway reached a higher level <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians. Summittunnels were by no means uncommon given the steepness of the approaches to mostCarpathian passes which horse-shoe bends <strong>in</strong> si<strong>de</strong> valleys could not a<strong>de</strong>quately address.The Abt rack system was used for a m<strong>in</strong>or m<strong>in</strong>eral l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the Iron Gate Pass <strong>in</strong> 1908 butwas not feasible for pr<strong>in</strong>cipal routes. A remarkable feature of the Carpathian railway systemis the steady <strong>de</strong>velopment which cont<strong>in</strong>ued to the 1960s for the table lists eight projects <strong>in</strong>the 1860s and 1870s, five each dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1880-1899, 1900-1919 and 1920-1939 periodsand another three s<strong>in</strong>ce. This po<strong>in</strong>ts to the cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g need for cohesion and security with<strong>in</strong>the successor states <strong>in</strong> the context of numerous ‘gap clos<strong>in</strong>g’ possibilities comb<strong>in</strong>ed withhigh construction costs which required careful prioritisation until railways lost theirprivileged status <strong>in</strong> 1989. However, some of the l<strong>in</strong>es built <strong>in</strong> the Habsburg era were littleused after the First World War. While the two l<strong>in</strong>es runn<strong>in</strong>g southwest from L’viv reta<strong>in</strong>eda mo<strong>de</strong>st service, the l<strong>in</strong>e to Sighet via Rakhiv lost the through services provi<strong>de</strong>d forRomanians until the Năsăud-Ilva Mică-Vatra Dornei l<strong>in</strong>e was f<strong>in</strong>ished <strong>in</strong> 1938 (Ronai 1993,p.361).Industrial <strong>de</strong>velopmentThe railways attracted <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>de</strong>velopment, but <strong>in</strong> a context of specialisationwith<strong>in</strong> the imperial economy as a whole. The authorities were happy to see efficiencyenhanced through complementary economic regions whereby the Czech Lands comprisedthe pr<strong>in</strong>cipal workshop. The ‘Ausgleich’ gave rise to an enlarged Hungarian <strong>in</strong>dustrialestablishment but this was concentrated heavily <strong>in</strong> Budapest. Be<strong>in</strong>g peripheral <strong>in</strong> relation tomost of the great cities of the empire, the Carpathians were somewhat disadvantaged. Somelight manufactures <strong>de</strong>veloped - like the brewery based on the Brzesko estate near Bochniawhich has produced Okocim beer s<strong>in</strong>ce 1845 - but others succumbed to compete withfactory production from the major <strong>in</strong>dustrial regions. The elites <strong>in</strong> these backward areasbenefited from cheap agricultural labour while ord<strong>in</strong>ary people had the options of migrationto the <strong>in</strong>dustrial cores or emigration to the United States. But there is an ethnic argumentthat could be advanced <strong>in</strong> terms of the disproportionate <strong>in</strong>fluence of the Germans and Jews<strong>in</strong> commerce and manufactur<strong>in</strong>g - and consequently <strong>in</strong> urban <strong>de</strong>velopment. The Jews wereprom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong> the larger towns on the outer si<strong>de</strong> of the Carpathian arc between Bielsko-Białaand Focşani. Their communities often excee<strong>de</strong>d 10,000 <strong>in</strong> the late 19th century (22,000 atČernivci) and accounted for 30-50% of the total population (Magocsi 1993). On the <strong>in</strong>nersi<strong>de</strong> the belt of Jewish settlement was more restricted and covered only Preşov, Koşice,Užhorod, Mukačeve and Sighetul Marmaţiei. The Jews were very active <strong>in</strong> commerce, theyalso played a key role <strong>in</strong> the <strong>de</strong>velopment of <strong>in</strong>dustry <strong>in</strong> Bukov<strong>in</strong>a, especially <strong>in</strong> food43

David TURNOCKprocess<strong>in</strong>g (Moskovich 2001). While the ethnic factor merits further research it is clear thatsome groups were constra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> their cultural, economic and political advancement and,for example, Romanian entrepreneurs <strong>in</strong> the empire had limited access to capital until the<strong>de</strong>velopment of local banks to serve specific ethnic communities.There were a number of specialised resource-based activities (us<strong>in</strong>g coal, oil, ironand other ores - as well as timber). The oil <strong>in</strong>dustry imp<strong>in</strong>ged on the Romanian Carpathians<strong>in</strong> areas such as Berca, Câmp<strong>in</strong>a and Mo<strong>in</strong>eşti; but there were also Galician oilfields aroundGorlice, Jasło and Krosno - where exploitation began <strong>in</strong> 1851 and I.Lukasiewicz distilledoil for the first time, at a laboratory scale (recalled by the petroleum <strong>in</strong>dustry open airmuseum at Bobrka). Progress was facilitated by the ‘Inner Carpathian Railway’ of 1884(Żywiec-Nowy Sącz-Jasło-Krosno-Zagórz) mentioned above (Kortus & Adamus 1989).Along with light <strong>in</strong>dustry, wood process<strong>in</strong>g and tourism (mentioned below) Galicia foundsome relief from its post-partition <strong>de</strong>pression. Asi<strong>de</strong> from the Upper Silesian coalfield andits extension to the Ostrava area of Moravia (not covered <strong>in</strong> <strong>de</strong>tail, although many migrantswere attracted from adjacent areas of the Carpathians) metallurgical <strong>in</strong>dustries cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong>Banat and northern Hungary with the availability of mo<strong>de</strong>st coal reserves to effect atransition from charcoal to coke smelt<strong>in</strong>g. In<strong>de</strong>ed an entirely new coalfield was opened up<strong>in</strong> the upper Jiu valley at Petroşani, expand<strong>in</strong>g rapidly after the railway arrived 1867.Figure 5: Railway build<strong>in</strong>g: 19th and 20th centuries.44

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesKey for the Trans-Carpathian l<strong>in</strong>es a-z (* <strong>de</strong>notes that the railway negotiates a tunnel at the summit):a. 1863: Baziaş-An<strong>in</strong>a reach<strong>in</strong>g 559m* on the Oraviţa-Gârlişte watershed: a coal-carry<strong>in</strong>g railway to supplyDanube steamers conceived dur<strong>in</strong>g the Crimean War, partially opened <strong>in</strong> 1856 and connected withTimişoara and Budapest <strong>in</strong> 1858. When the l<strong>in</strong>e was cut by the Yugoslav frontier after 1918 there wereproposals for l<strong>in</strong>ks from Oraviţa to both Moldova Nouâ and Orşova; neither of which has beenimplemented. b. 1868: Arad-Alba Iulia via the Mureş valley (c.200m).c. 1870: Ora<strong>de</strong>a-Cluj Napoca via theCriş-Someş watershed (c.500m between Hued<strong>in</strong> and Aghireşu).d. 1871: Bohum<strong>in</strong> to Košice/Miskolc via theO<strong>de</strong>r (Olse)-Kysuca watershed (553m* at Jablunkov Pass). Also 700m at Poprad at the Váh-Hornádwatershed on the Košice l<strong>in</strong>e (1872); and 600m <strong>in</strong> Štubňa-Kremnica area on the Turiec-Kremnicawatershed and c.400m at the Slat<strong>in</strong>a-Kriváň watershed east of Zvolen on the Miskolc l<strong>in</strong>e (1872).e. 1872:L’viv-Košice via the Osława-Laborec watershed (640m* at Łupków Pass).f. 1876: Tarnów to Košice viathe Poprad valley (c.500m at Muszyna-Plaveč).g. 1878: Caransebeş-Orşova via the Timiş-Cerna Corridor(515m at Domaşnea).h. 1879: Sighişoara-Ploieşti via Braşov at the Râul Negru-Prahova watershed (1040mat Pre<strong>de</strong>al). Also c.500m* at Beia on the Târnave-Olt watershed between Sighişoara and Braşov (1873).i.1884: Čadca-Żywiec via the Skaličanka-Sola watershed (680m at Skalité-Zwardoń).j. 1887: L’viv-Nyíregyháza via Stryj and the Opor-Vica watershed (1,014m* at Beskid).k. 1888: Brno-Trenč<strong>in</strong> viaUherské Hradiště(c.300m <strong>in</strong> the Vlára valley).l. 1895: Ivano Frankivs’k-Sighetul Marmaţiei via Rachiv(c.900m at Voronenko-Jas<strong>in</strong>a Pass and c.900m* at the Prut-Black Tisza watershed).m. 1899: Adjud-Ciceuvia the Trotuş-Olt watershed (1,025m* at Ghimeş Pass).There was also a plan for Ciceu-Odorhei viaVoşlăbeni and the Mureş-Târnave watershed (1,007m* at Sicaş Pass). n. 1901: Sibiu-Râmnicu Vâlcea viaOlt Valley (400m at Red Tower Pass).o. 1904: Nowy Targ-Kral’ovany via Podczerwone-Trstená (theDunajec-Orava watershed: 768m at Sucha Hora).p. 1905: L’viv-Nyíregyháza via Sambir, Turka n.Stryjemand Vel.Bereznyj: (859m at Użocka Pass on the San-Už watershed).q. 1908: Subcetate-Caransebeş viaHaţeg and the Râul Mare-Bistra watershed (892m at the Iron Gate Pass): ‘l<strong>in</strong>ia cu cremaliera’ us<strong>in</strong>g the Abtrack system for 1 <strong>in</strong> 20 gradient. This east-west connection was exten<strong>de</strong>d beyond Caransebeş to reachReşiţa <strong>in</strong> 1938 from where a railway (<strong>de</strong>veloped between 1858 and 1892) exten<strong>de</strong>d to Timişoara.r. 1915:Vatra Dornei-Tiha Bârgăului at the watershed between the Moldavian Bistriţa and Transylvanian Bistriţa(c.1100m south of Tihuţa Pass). This was a wartime project us<strong>in</strong>g petrol-electric locomotives, repaired <strong>in</strong>1922 for peacetime use <strong>in</strong> Romania. Connected eastwards by the Bukow<strong>in</strong>er Lokalbahn from Dărmăneşti:reach<strong>in</strong>g 528m at Strigoaia on the section to Vama (1888); then 1,099m at Mestecăniş Pass on the extensionto Vatra Dornei (1902). The Vatra Dornei-Dornişoara section was reta<strong>in</strong>ed when the rest of the l<strong>in</strong>ereplaced by project 'u' <strong>in</strong> 1938.s. 1929: Veselí nad Moravou-Nové Mesto nad Váhom via Velká nadVeličkou on the Teplica-Myjava watershed (400m* at Myjava).t. 1931: Braşov-Întorsura Buzăului reach<strong>in</strong>g700m* at Teliu Tunnel breach<strong>in</strong>g the Tărlung-Buzău watershed. This was meant to the be the start of a l<strong>in</strong>ebetween Braşov and Buzău which was discont<strong>in</strong>ued due to the unstable terra<strong>in</strong> of the Buzău valley. It wasone of several projects to overcome the limited capacity of the Prahova valley l<strong>in</strong>e. Other options wereS<strong>in</strong>aia-Pietrosiţa - listed <strong>in</strong> 1913 but not procee<strong>de</strong>d with (Turnock 2001 p.139) - and Curtea <strong>de</strong> Argeş-Râmnicu Vâlcea, virtually complete <strong>in</strong> 1989 but subsequently abandoned due to lack of f<strong>in</strong>ance and reducedrailway traffic, though <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong> projects for EU ISPA accession fund<strong>in</strong>g as part of the TINAprogramme.u. 1937: Ostrava-Púchov via Vsetín (528m <strong>in</strong> the Lysky valley).v. 1938: Năsăud-Vatra Dorneivia Ilva Mică (on the Ilva-Bistriţa watershed: 874m at Grăd<strong>in</strong>iţă Pass).w. 1939: Prievidza-Košice viaBanská Bystrica (c.600m* on the Štubňa-Harmanec section on the Handlová-Teplica watershed). Thewhole project <strong>in</strong>volved Prievidza to Handlová (1913); Štubňa at 600m* (1931); Harmanec at c.600m(1939); Banská Bystrica (1913); Podbrezová (1884); Brezno nad Hronom (1895), Červ<strong>in</strong>a Skála (1903);Mníšek n.Hnilcom, reach<strong>in</strong>g 900m* at the Hron/Hnilec watershed (1936); Margecany (1884); Kysak(1872); and Košice (1870).x. 1948: Simeria-Târgu Jiu via the Jiu <strong>de</strong>file (c.700m at Băniţa), though thishighest level was actually reached <strong>in</strong> 1870 on the Strei-Olt watershed when the Petroşani branch wascompleted.y. 1948: Salva-Vişeu via the Iza-Sălăuţa watershed (682m* below Şetref Pass); part of a throughl<strong>in</strong>e from Braşov to Sighetul Marmaţiei which reached 882m at Izvorul Mureşului, south of Gheorgheni(1907) and c.600m* on the Deda-Sărăţel section (1942).z. 1979: Arad-Brad-Deva (c.350m* at Vălişoara onthe Criş Alb-Mureş watershed); part of a plan for a railway l<strong>in</strong>k between Ora<strong>de</strong>a and Deva that would havereached 500m between Vaşcău and Brad on the Criş Negru-Criş Alb watershed.45

David TURNOCKPopulation rose from 10.1 thousands <strong>in</strong> 1857 to 16.0 <strong>in</strong> 1880 (2.63% annually)and then 47.2 <strong>in</strong> 1910 (6.52%). While the coal was not of good metallurgical quality itcontributed to the expansion of ironwork<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Poiana Rusca Mounta<strong>in</strong>s with charcoalfurnaces at Ruschiţa (1828) and Rusca Montană (1830) followed by coke smelt<strong>in</strong>g at Călan<strong>in</strong> 1863 and more particularly at Hunedoara where five furnaces were built dur<strong>in</strong>g 1882-1903. Both Reşiţa and Hunedoara attracted labour from the immediate mounta<strong>in</strong> areas andfrom <strong>de</strong>pressions such as the Timiş-Cerna Corridor and Haţeg. The whole area from Haţegthrough Hunedoara and Călan to Deva and Simeria witnessed growth from 26.5 thousands<strong>in</strong> 1857 to 30.4 <strong>in</strong> 1880 and 43.7 <strong>in</strong> 1910.Figure 6: The An<strong>in</strong>a CoalfieldWhile Hunedoara’s pig went to Budapest, the Reşiţa area acquired its ownsteelmak<strong>in</strong>g capacity from 1868 (Manolescu et al. 1996), with eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustries <strong>in</strong>Reşiţa itself and also <strong>in</strong> outly<strong>in</strong>g settlements like Bocşa (Perianu 1996). The whole of the46

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesformer state doma<strong>in</strong>, now managed by STEG, had a population of 76.1 thousand <strong>in</strong> 1880ris<strong>in</strong>g to 88.5 <strong>in</strong> 1910: probably the largest <strong>in</strong>dustrial complex <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians an<strong>de</strong>quivalent to Hunedoara and Petroşani together. Meanwhile progress <strong>in</strong> northern Hungaryarose when coal m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and metallurgical <strong>in</strong>terests were comb<strong>in</strong>ed through theRimamurány-Salgótarján company <strong>in</strong> 1881 and the <strong>in</strong>herited foundries at Borsodnadasd,Ózd and Salgótarján were supplemented by steelmak<strong>in</strong>g at Ózd and f<strong>in</strong>ish<strong>in</strong>g atSalgótarján. Non-ferrous metals were also of much <strong>in</strong>terest especially the gold and silverm<strong>in</strong>es served by smelters <strong>in</strong> Baia Mare and Zlatna. While there was much <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> theformer dur<strong>in</strong>g the era of ‘Direcţia M<strong>in</strong>elor Baia Mare’ (1864-1918) <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g factories forchemicals, electrolytic copper and lead <strong>in</strong> the Baia Mare-Cavnic area (Bălănescu et al.2002), the Roşia Montană area was remarkable for its opencast work<strong>in</strong>g based on peasantfamily units; each work<strong>in</strong>g a small concession of a few square yards. The processes ofblast<strong>in</strong>g, extraction, crush<strong>in</strong>g and transport (to Abrud) “are carried out <strong>in</strong> the ru<strong>de</strong>st possiblemanner [with] no less than 500 crush<strong>in</strong>g mills and wash<strong>in</strong>g floors with<strong>in</strong> the space of acouple of <strong>English</strong> miles” (Paget 1850, p.299). Some peasants collected ore ly<strong>in</strong>g on thepathways where it was found “glitter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the sun” after some natural sort<strong>in</strong>g of materialon the stony surface by ra<strong>in</strong>; show<strong>in</strong>g that the dream of “streets paved with gold” was noidle romance but “a serious reality” (Ibid, p.300). Some mo<strong>de</strong>rn mach<strong>in</strong>ery was <strong>in</strong>troduced<strong>in</strong>to un<strong>de</strong>rground m<strong>in</strong>es by the end of the period but the peasant <strong>in</strong>terest persisted <strong>in</strong>to the<strong>in</strong>terwar era.Reference should also be ma<strong>de</strong> to mo<strong>de</strong>rn water management ma<strong>de</strong> an impactthrough reservoirs and the first generation of hydropower projects. At Sibiu a new ‘CanalulŞcoala <strong>de</strong> Innot’ served the military school and hospital and further rationalisation of canals<strong>in</strong> 1879 gave rise to a park where there had previously been a lake and sawmill. The arrivalof the first long distance water conduit of 1894 meant that all the local streams lost much oftheir importance for water supply and more former lakes could now be used for open space(though lakes were reta<strong>in</strong>ed for fish <strong>in</strong> the upper part of the Cişnădie stream <strong>in</strong> Dumbrava)(Haţieganu 1942). Several hydropower projects were un<strong>de</strong>rtaken because, althoughtechnology and capital resources restricted <strong>de</strong>velopment to small projects to meet <strong>in</strong>dustrialneeds, a rhythm was ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed from the Caransebeş project of 1889 (70Kw) , by a localmill owner; to Băile Herculane (1892, 130Kw) for the local spa; Topleţ (1893, 80Kw) forlocal mills: Petresti (1894, 110Kw) for the <strong>paper</strong> mill; and Baia Sprie (1895, 140Kw) andCavnic (1900, 80Kw) for the Baia Mare m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g area. Sadu (1896, 185Kw) provi<strong>de</strong>d for theItalian Fet<strong>in</strong>elli company’s Talmaciu sawmill; while three units concerned with theHunedoara iron <strong>in</strong>dustry - Govăjdia (1896, 200Kw), Căţănaş (350Kw, 1897) andHunedoara (1897, 420Kw) - and the Oţelu Roşu ironworks secured 320Kw of capacity <strong>in</strong>1898 followed by Meanwhile <strong>in</strong> Romanian territory Câmp<strong>in</strong>a (1897, 200Kw) served the oil<strong>in</strong>dustry; S<strong>in</strong>aia (1898, 250Kw) was nee<strong>de</strong>d by the local resort. The <strong>paper</strong> mills of Leteaand Buşteni were endowed <strong>in</strong> 1898 (100Kw) and 1899 (24Kw) respectively (Pop 1996,pp.12-30). Among the projects un<strong>de</strong>rtaken after 1900 Reşiţa provi<strong>de</strong>s perhaps the most<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g example s<strong>in</strong>ce canalisation of the Bârzava valley gave rise to an efficient systemof canalised timber transport as well as a 1.8MW power station at Grebla on the edge of thetown (Hill<strong>in</strong>ger et al. 2001).The Logg<strong>in</strong>g Industry was greatly facilitated by the ma<strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e railways and also bylight, narrow-gauge forest railways - usually built by the logg<strong>in</strong>g companies - which arealso shown on Figure 5. The distribution is very uneven on account of an overrid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong> res<strong>in</strong>ous timber like fir and spruce, rather than beechwood. Hence northeastern Hungary47

David TURNOCK(north of Satu Mare) has very few such railways <strong>in</strong> contrast to the well-<strong>de</strong>veloped systemacross the watershed (based on sawmills south of Stryj and around Suceava <strong>in</strong> Bucov<strong>in</strong>a).Generally the forest railways penetrated tributary valleys to heights of 1,000m. Systemsmight branch to serve several m<strong>in</strong>or valleys <strong>in</strong> the upper reaches of a particular bas<strong>in</strong> orthey might w<strong>in</strong>d across low watersheds as <strong>in</strong> the Topol’čany area of western Slovakia.Where the res<strong>in</strong>ous timber was high above the beechwoods it could be feasible to reachover the ma<strong>in</strong> watershed especially when the <strong>in</strong>frastructure was better <strong>de</strong>veloped on onesi<strong>de</strong> of the mounta<strong>in</strong>s than the other: funiculars were often <strong>in</strong>stalled where watersheds hadto be crossed (or <strong>in</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ed planes <strong>in</strong> the case of the Comandău system <strong>in</strong> Covasna) (Turnock2006, pp.107-11). Gradients would normally be <strong>in</strong> favour of the loa<strong>de</strong>d wagons, typicallymov<strong>in</strong>g down-valley, and there is a tradition of gravity work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> some areas. The forestrailways around An<strong>in</strong>a were complicated by w<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g trajectory to cross the watershedbetween the Gârliste and M<strong>in</strong>iş valleys but the sawmill <strong>in</strong> the M<strong>in</strong>iş valley (at Carşa) wasrationally located at a po<strong>in</strong>t where timber from all directions would <strong>de</strong>scend by gravity andonly sawn timber would then have to taken out aga<strong>in</strong>st the gradient to An<strong>in</strong>a.But valleys with steep profiles might pose <strong>in</strong>superable operational problems andfavour retention (<strong>de</strong>spite consi<strong>de</strong>rable raw material losses) of timber float<strong>in</strong>g systemsorganised with the help of woo<strong>de</strong>n barrages to store water to <strong>de</strong>al with sections of limited<strong>de</strong>pth. When Germans from Ba<strong>de</strong>n foun<strong>de</strong>d Colonia Bistra <strong>in</strong> 1870 to supply the Petreşti<strong>paper</strong> factory from the virg<strong>in</strong> forests of the Sebeş valley, a ‘stavilar’ was <strong>in</strong>stalled toimprove the float<strong>in</strong>g downriver while a further dam (‘zagaz’) at Oaşa Mare accelerated the<strong>de</strong>forestation of the upper valley. Alternatively, funiculars might extend from neighbour<strong>in</strong>gvalleys e.g. from the upper Lotru to the Sadu valley and Tălmaciu. Where the valleys wereextremely circuitous such as the route down the Walosatky and San valleys <strong>in</strong> theBieszczady area (Galicia) to jo<strong>in</strong> the ma<strong>in</strong> L’viv-Užhorod raikway south of Turka it waspossible with some simple earthworks to shorten the distance consi<strong>de</strong>rably by us<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>orvalleys while ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a level or gradual downhill gradient for loa<strong>de</strong>d wagons. Thedraw<strong>in</strong>g of the Polish-Soviet boundary after 1945 so as to leave the ma<strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the-thenUSSR effectively cut this l<strong>in</strong>e of communication. Meanwhile the Wetl<strong>in</strong>a area rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>touch with the Sanok-Humenné l<strong>in</strong>e at Łupków although the section between the Sol<strong>in</strong>kaand Oslawa valleys <strong>in</strong>volved a m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>de</strong>viation <strong>in</strong>to Czechoslovak territory.The local impact of the logg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustry can be gauged from Nixon (1998, pp.276-7) who mentions a sawmill at Regh<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> northern Transylvania <strong>in</strong> 1879 produc<strong>in</strong>g170,000cu.m/yr by 1905 when a narrow-gauge forest railway was opened to br<strong>in</strong>g timberfrom the Lapuşna area of the Giurghiu valley (though the traditional raft<strong>in</strong>g and float<strong>in</strong>gsystems cont<strong>in</strong>ued on a small scale <strong>de</strong>spite damage to river banks). The railway was a forcefor mo<strong>de</strong>rnisation s<strong>in</strong>ce it was used for passengers as well as freight and tourists began topenetrate the valley, especially with hunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d. The tourism function can also be seenon the forest railways from Curtea <strong>de</strong> Argeş, Mâneciu, Zărneşti and Zăvoi to Cumpana,Cheia, Plaiul Foii and Poiana Mărului respectively. As the forests were opened toexploitation, permanent settlements and services (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g tourism) appeared over much ofwhat was previously a pioneer fr<strong>in</strong>ge (Turnock 1991a, p.57). Giurcăneanu (1988) hasrelated local settlement hierarchies to the forest railway morphology: not<strong>in</strong>g the pr<strong>in</strong>cipalno<strong>de</strong>s where the sawmills and transfer po<strong>in</strong>ts are situated; the hamlets at ma<strong>in</strong> junctions andcollect<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts; and outly<strong>in</strong>g cottages, forestry cab<strong>in</strong>s and hunt<strong>in</strong>g lodges on theperiphery. As an example Velcea (1964) mentions the branch railway to Bixad-Oaş whichencouraged expansion of the m<strong>in</strong>eral water <strong>in</strong>dustry by the Radak and Szentivany families48

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesfrom 1902, followed by sawmill<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Bixad <strong>in</strong> 1910 thanks to a web of forest railways toValea Lech<strong>in</strong>cioarei, Valea Talnei Mici (Băile Puturoasa) and Valea Tribşorului.The enhanced value of woodland meant further limitations on shepherd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>Moravia and elsewhere. Although the abolition of serfdom <strong>in</strong> 1848 gave shepherdsownership of land, they received only a small proportion of what they had previously used,while the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>de</strong>r passed to the former landlords who established woodlandmonocultures at a time when the economics of sheep farm<strong>in</strong>g were un<strong>de</strong>rm<strong>in</strong>ed bycompetition from Australian wool. Traditional shepherd<strong>in</strong>g went <strong>in</strong>to retreat anddisappeared from Moravia before the onset of communism. Meanwhile, the value of timbergave an <strong>in</strong>centive to plant unproductive land as was the case around Sibiu <strong>in</strong> the late 19thcentury when p<strong>in</strong>e forests were established at Gura Râului, Orlat, Răş<strong>in</strong>ari and Tilişca. Butat the same time, the ol<strong>de</strong>r forests were substantially restructured. Large clearcuts weregenerally restocked with spruce to the extent of 95% (with some larch and Douglas fir), atthe expense of beech and oak, while the average age of the woodlands <strong>de</strong>creased sharply.There was also a ten<strong>de</strong>ncy <strong>in</strong> the 19th century to use seed of foreign provenance (ma<strong>in</strong>lyAustrian) to restock bare lands after w<strong>in</strong>d and <strong>in</strong>sect calamities (Voloscuk 1998). The sameten<strong>de</strong>ncies to monoculture have been reported from Ukra<strong>in</strong>e s<strong>in</strong>ce c.1750 with the <strong>de</strong>creaseof beech from 54.9 to 33.0% (and oak and related woods from 13.3 to 10.1%) and the<strong>in</strong>crease of fir-spruce from 31.8 to 55.9%. With heavy logg<strong>in</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>ce the late 19th century,perpetuated <strong>in</strong> the communist period, 40.9% of the forests now comprise sapl<strong>in</strong>gs and30.9% are middle-aged, while only 28.2% are mature or are approach<strong>in</strong>g this condition.These trends contributed to pressure for nature conservation. Slovakia’s first nature reserve(Ponicka Huta) dates to 1895 and provi<strong>de</strong>d an <strong>in</strong>spiration for the ‘zapovedniki’ which areareas strictly protected for scientific and educational purposes, with recreation prohibited.TourismThe historic over-<strong>de</strong>velopment of Carpathian valleys cont<strong>in</strong>ued, especially whenthe railway imposed heavier land use pressures and contributed to the dissem<strong>in</strong>ation ofalien species l<strong>in</strong>ked with mo<strong>de</strong>rn transport. The end of feudalism bought greater fiscalpressure with excessive stock<strong>in</strong>g of common graz<strong>in</strong>gs. Pressure was relieved by emigrationand significant urban <strong>de</strong>velopment - albeit mo<strong>de</strong>st by lowland standards - especially <strong>in</strong> thefoothills and along the ma<strong>in</strong> tra<strong>de</strong> routes where local servic<strong>in</strong>g was boosted not only bylocal manufactures but also by tourism, for <strong>in</strong>dustrial pollution was quite localised and didnot seriously constra<strong>in</strong> the growth of spa tourism (or lesser <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> hunt<strong>in</strong>g, rambl<strong>in</strong>gand w<strong>in</strong>ter sports). In Galicia, greater adm<strong>in</strong>istrative autonomy at the end of the 19thcentury was reflected by ‘art nouveau’ most evi<strong>de</strong>nt <strong>in</strong> fashionable spas like Krynica (aborough <strong>in</strong> 1889) and Szczawnica <strong>in</strong> the Pien<strong>in</strong>y, which drew great benefit from belated railaccess <strong>in</strong> 1911 after the Hungarian Szalay family had first bought the estate <strong>in</strong> 1834 and<strong>de</strong>veloped the landscape park and local hous<strong>in</strong>g;. In the Low Beskids, Iwonicz was foun<strong>de</strong>d<strong>in</strong> 1839 and ga<strong>in</strong>ed a reputation for the treatment of rheumatic, digestive and respiratorydisor<strong>de</strong>rs. Other examples <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d Rymanów and Wysowa; the latter <strong>de</strong>velop<strong>in</strong>g out of a15th century Wallachian village and a centre of the w<strong>in</strong>e tra<strong>de</strong> with Hungary. Rabka <strong>in</strong> theBeskid Wyspowy also <strong>de</strong>veloped as a spa <strong>in</strong> the late 19th century with access to watersconta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sodium and chlor<strong>in</strong>e. And when Ustron’s iron <strong>in</strong>dustry was eclipsed by Tř<strong>in</strong>ec(Ostrava) the water<strong>in</strong>g function came to dom<strong>in</strong>ate with official recognition of the spa <strong>in</strong>1882.49

David TURNOCKThe outstand<strong>in</strong>g case is Zakopane where promotion for tourism arose <strong>in</strong> the 1870sthrough the comb<strong>in</strong>ed efforts of local personalities associated with the society named‘Towarzystwo Tatrzańskie’ 1873: T.Chałubiński (physician), M.Karlowicz (composer andmounta<strong>in</strong>eer), J.G.Pawlikowski (writer and theatre director), W.E.Radzikowski (artist),J.Stolarczyk (Catholic priest), K.P.Tetmajer (poet) and S.Witkiewicz: the architect whocreated the ‘Zakopane style’: blend<strong>in</strong>g with the 19th century church and traditional woo<strong>de</strong>nbuild<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> contrast to the architecture of the other lead<strong>in</strong>g resorts of Galicia. Initially ahealth spa <strong>in</strong> 1886, Zakopane became an important centre fot mounta<strong>in</strong> expeditions(Turnock 2006, p.136) and it was also the birthplace of Polish ski<strong>in</strong>g with the formation ofthe ski<strong>in</strong>g association <strong>in</strong> 1907 (‘Sekcja Narciarstwa’) and provision of a voluntary mounta<strong>in</strong>rescue service <strong>in</strong> 1909. It was also seen as a cultural centre and symbol of Polish nationalunity pre-1914. Moreover <strong>in</strong> 1889 the entire estate became the property of Count Zamoyskiwho eventually (1924) established a national foundation lead<strong>in</strong>g to the present TatraNational Park. Meanwhile, the spa system exten<strong>de</strong>d through the Eastern Carpathians(Cianga 1994). There was Truskavec <strong>in</strong> Ukra<strong>in</strong>e where therapeutic spr<strong>in</strong>g waters were firstrecognised <strong>in</strong> the 16th century. The first hydropathic <strong>in</strong>stitution (compris<strong>in</strong>g eight cab<strong>in</strong>s)was started <strong>in</strong> 1827 by T.Torosiewicz, a L’viv doctor-chemist-pharmacist from anArmenian family, who analyzed the spr<strong>in</strong>g waters. Interest <strong>in</strong>creased with oil boom nearbyat Boryslav. The overhaul <strong>in</strong> 1911 - with provision of new lodg<strong>in</strong>gs and pavilions by a localcompany hea<strong>de</strong>d by an entrepreneur from nearby Drohobyč who became council chairman- anticipated the open<strong>in</strong>g of a branch railway from Drohobyč on the Sanok-Stryj section ofthe Inner Carpathian Railway (1872) which served nearby Boryslav <strong>in</strong> the same year.Rail transport of course was all-important for <strong>de</strong>velopment on a fairly large scale,with a surge <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess typically correlat<strong>in</strong>g with the arrival of the railway at places likeCălimăneşti and Slănic-Moldova <strong>in</strong> Romania, although Băile Herculane <strong>in</strong> Banat had theadvantage of proximity to Danube steamers at Orşova. However such might be thereputation of the ‘cure’ at a particular spa that quite difficult journeys might be un<strong>de</strong>rtaken.At Borsec <strong>in</strong> eastern Transylvania where carbonaceous waters were first discovered by ahunter <strong>in</strong> the 15th century - and their curative properties were validated <strong>in</strong> Vienna <strong>in</strong> 1777soon after a military presence was established <strong>in</strong> 1762 - a lease was obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> 1805 andm<strong>in</strong>eral water was distributed <strong>in</strong> bottles manufactured from local silica. But there wasmo<strong>de</strong>st patronage by visitors even before the railway age, lead<strong>in</strong>g to a proper balnearyestablishment <strong>in</strong> 1873 when local peat and lignite were used to heat water for baths taken <strong>in</strong>woo<strong>de</strong>n tubs. But even when the railway reached Regh<strong>in</strong> from Târgu Mureş <strong>in</strong> 1886patients still faced a journey of some 85kms by coach (‘diligenţa’) - the same distance fromMiercurea Ciuc where the railway arrived <strong>in</strong> 1897 - with the alternative of a slightly shorter66km haul from Piatra Neamţ <strong>in</strong> Romania which ga<strong>in</strong>ed a rail service <strong>in</strong> 1885. The roadjourney was reduced to 20kms after a railway reached Topliţa <strong>in</strong> 1909, with the optioncircuitous onward journey of 40kms the follow<strong>in</strong>g year by narrow gauge forest railwaywhich went most of the way (and was later exten<strong>de</strong>d to the spa itself). A specially <strong>de</strong>signedrailcar was provi<strong>de</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the communist period until a local bus service took over.Meanwhile hunt<strong>in</strong>g was attract<strong>in</strong>g a select, wealthy clientele and was exert<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>fluenceon land use <strong>in</strong> some remote areas: for example <strong>in</strong> the Retezat where pastoralism wasreduced (Bucura ‘stâna’ was abandoned <strong>in</strong> 1906) when Hungarian landowners refused torent pastures so as to keep the land <strong>in</strong>tact for hunt<strong>in</strong>g bear and chamois (De Martonne 1922,p.133).50

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesAs Ford (2002) has expla<strong>in</strong>ed there was a grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians astravellers from the more <strong>in</strong>dustrialised parts of Europe took advantage of the comforts ofrail travel to reach a distant mounta<strong>in</strong> region and escape from mo<strong>de</strong>rn civilisation <strong>in</strong> an areawhere the ‘glamour of the Middle Ages’ still l<strong>in</strong>gered. The Carpathians also provi<strong>de</strong>d anantidote to the all-too-familiar Alp<strong>in</strong>e landscapes, with “the <strong>de</strong>ficiency <strong>in</strong> heightcompensated by the character of the scenery” (Ibid, p.56). Some thought the Carpathians‘too melancholy’, but the rural fantasy offered by the ‘surrogate Alps’ was wi<strong>de</strong>lyappreciated for the relative lack of sophistication and while Kraków was a common po<strong>in</strong>t ofentry to the mounta<strong>in</strong>s, the Transylvanian sett<strong>in</strong>g for Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ novel drewattention to the Hungarian railway system s<strong>in</strong>ce the story seems to have been cast at thefurthest outpost (at the time) of the network extend<strong>in</strong>g east of Budapest to the Bistriţa area.Tourism contributed to a better un<strong>de</strong>rstand<strong>in</strong>g of the ethnic characteristics of the region thatwere all too easily overlooked by the cultural manifestations of the lead<strong>in</strong>g national groups.Franz Jozsef’s tour <strong>in</strong> 1880 <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d a visit to the Kolomyja ethnographic exhibition on ‘theHutsul region’; organised by the Tatra Society which expan<strong>de</strong>d from its Zakopane basethrough branches <strong>in</strong> both Kolomija and Ivano-Frankivs’k provid<strong>in</strong>g chalets and trails <strong>in</strong> themounta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g an 'Alp<strong>in</strong>e base camp' <strong>in</strong> the Hutsul village of Żabie (Verkhovyna).Subsequent <strong>de</strong>velopment of tourism boosted <strong>de</strong>mand for Hutsul handicrafts and helped tosusta<strong>in</strong> a group <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nt on Jewish moneylen<strong>de</strong>rs and Armenian cattle<strong>de</strong>alers follow<strong>in</strong>g the end of feudalism. At the same time there was evi<strong>de</strong>nce of a hid<strong>de</strong>nagenda as Polish nationalists ‘claimed’ the Carpathian groups emerg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the ethnicbor<strong>de</strong>rlands; first evi<strong>de</strong>nt when the Warsaw Poles embraced the Gorale Highlan<strong>de</strong>rs anddiffused the ‘Zakopane style’ diffused as their own (Dobrowski 2005).The rural impactAlthough direct railway access conferred clear economic advantages, the forces ofmo<strong>de</strong>rnisation were exten<strong>de</strong>d by fee<strong>de</strong>r roads with postal and telegraph servicesun<strong>de</strong>rp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g each local adm<strong>in</strong>istrative centre. These centres attracted a range of servicesand private bus<strong>in</strong>esses As Nixon (1998, p.219) po<strong>in</strong>ts out <strong>in</strong> the case of the Giurghiu valleynear Regh<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> northern Transylvania, Giurghiu village emerged as a central place, s<strong>in</strong>ce itwas historically the key village of the estate, although a military road exten<strong>de</strong>d formal localgovernment a little further up the valley to Ibăneşti. Such villages would often act assurrogate towns with their markets, handicrafts and small professional communities; noted<strong>in</strong> monographs <strong>de</strong>al<strong>in</strong>g with Baia <strong>de</strong> Fier <strong>in</strong> Oltenia and similar places that showed somedynamism from the turn of the 19th century. And s<strong>in</strong>ce the towns were becom<strong>in</strong>g moreimportant <strong>in</strong> the economic and cultural senses, the 18th century phenomenon of ‘roireascen<strong>de</strong>nte’ may have lost much of its momentum by the end of the century as pressure togrow crops on the high ground was relaxed and terrac<strong>in</strong>g systems lost some of theirimportance (Opreanu 1942; Pacurar 1997). As pressure on the land was relaxed and erosionwas reduced, there was a transition back to woodland via juniper bushes evi<strong>de</strong>nt <strong>in</strong> theJasiołka, Osława and Wisłoka catchments of the Polish Carpathians and it is evi<strong>de</strong>nt from amap of 1851 how forest replaced the former open fields of Lipowiec (Lac 2000).Partial re-afforestation from the late 19th century also occurred <strong>in</strong> areas of‘kopanitse’ settlement <strong>in</strong> Moravia and Slovakia (Huba 1989), recall<strong>in</strong>g the stake of theWallachian shepherds <strong>in</strong> the northern Hungarian bor<strong>de</strong>rland <strong>in</strong> general and the ‘Valassko’country of the White Carpathians <strong>in</strong> particular. Distance from timber markets had51

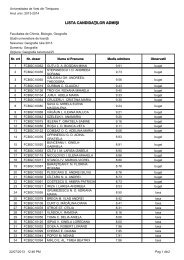

David TURNOCKpreviously <strong>de</strong>layed <strong>in</strong>tensive forestry and given the pastoralists a greater stake <strong>in</strong> the land sothat landlords allowed the high surfaces to be taken over by shepherd<strong>in</strong>g so as to supportpermanent settlement - with organic manure to support crops on consi<strong>de</strong>rable areas and notsimply symbolic patches of vegetables and cereals <strong>in</strong> a well-fertilised ‘kosar’ where sheepwere stocka<strong>de</strong>d and shepherds built their shelters. However the land had becomeexcessively gullied and subdivi<strong>de</strong>d by three centuries of colonisation (Stankoviansky 2000).Further erosion of the old system was to occur <strong>in</strong> communist times when cooperative farmslevelled the steps of terraced fields and elim<strong>in</strong>ated many l<strong>in</strong>ear landscape elements. But astudy of hill land at Myjava <strong>in</strong> the Jablonka catchment has reconstructed much of the oldcultural landscape and correlated the gullies with headlands, tracks and lynchets while theWallachian ethos can also be recalled through the open air museum at Rožnov podRadhoštĕm <strong>in</strong> Moravia.However, the freedom from the necessity of grow<strong>in</strong>g subsistence crops was only abless<strong>in</strong>g where labour could be re<strong>de</strong>ployed through commut<strong>in</strong>g to work <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry andservices. The contemporary problem of the Carpathians, which started to be felt <strong>in</strong> the 19thcentury, lay <strong>in</strong> the lack of sufficient non-agricultural employment for agriculture to switchmore comprehensively from subsistence to specialised livestock rear<strong>in</strong>g farms (Kurek1984). Pressure on land resources rema<strong>in</strong>ed strong <strong>in</strong> the south, for <strong>in</strong> 1905 96.8% of allpeople ow<strong>in</strong>g land <strong>in</strong> the mounta<strong>in</strong>s of Romania (pre-1918 frontiers) had hold<strong>in</strong>gsaverag<strong>in</strong>g only 2.8ha, with additional problems of fragmentation <strong>in</strong>to units of 0.6ha. Therewas cont<strong>in</strong>ued subdivision and fragmentation of farms <strong>in</strong> some areas with subsistencefarm<strong>in</strong>g for wheat and rye, supported by heavy manur<strong>in</strong>g. Romanian smallhol<strong>de</strong>rs soughtgraz<strong>in</strong>g for livestock and sold wood whenever possible to obta<strong>in</strong> additional <strong>in</strong>come and, <strong>in</strong>contrast to Moravia, traditional shepherd<strong>in</strong>g cont<strong>in</strong>ued as before <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians ofRomania and Transylvania. In the Subcarpathian hill country of Romania where steeplydipp<strong>in</strong>g sandstones and clays gave rise to landsli<strong>de</strong>s and mudflows peasants appreciated thepotentials of relatively immature, humid soils for maize, potatoes and plum trees whichprovi<strong>de</strong>d subsistence crops and a source of brandy that could be marketed along withsurplus animals. Oral evi<strong>de</strong>nce suggests that <strong>in</strong> the Pătârlagele area the microlandscapes ofpeasant farm<strong>in</strong>g accentuated the ten<strong>de</strong>ncies towards dispersal as the colonisation of themore stable landsli<strong>de</strong>s reached its peak <strong>in</strong> the 19th century <strong>in</strong> response to a grow<strong>in</strong>gpopulation and an expansion of capitalist farm<strong>in</strong>g on the lower terraces. Figure 7 shows aremarkable number of settlements that orig<strong>in</strong>ated at this time: many of them quite small buttak<strong>in</strong>g advantage of sites that were problematic for housebuild<strong>in</strong>g but attractive <strong>in</strong> offered arange of potentials (for cropp<strong>in</strong>g, graz<strong>in</strong>g, haymak<strong>in</strong>g and fruit grow<strong>in</strong>g) appropriate forsubsistence farm<strong>in</strong>g and pluriactivity (N.Muică et al. 2000). Some peasants emigrated whileothers found work <strong>in</strong> the lowlands on a permanent or temporary basis. Thus people fromPalt<strong>in</strong> and Tulnici <strong>in</strong> Vrancea went to Dobrogea after 1878 when this Black Sea prov<strong>in</strong>cecame un<strong>de</strong>r Romanian adm<strong>in</strong>istration.Census <strong>in</strong>formation is difficult to collect for the Carpathians as a whole butfortunately the Hungarian census of 1910 was reorganised on the basis of the presentcommunes and counties <strong>in</strong> preparation for the Romanian national atlas (though the raw datahas not been published) while the earlier data for 1857 and 1880 was subsequently <strong>de</strong>altwith along similar l<strong>in</strong>es (Rotariu et al. 1997a, 1997b) although the former does not coverBanat, Crişana and Maramureş. The results are presented <strong>in</strong> Table 1. For the whole area thepopulation was 2.25mln <strong>in</strong> 1880 and grew by 0.72mln (1.07 percent annually) to 1910 andalthough the rate <strong>in</strong> the towns (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cipient towns i.e. those <strong>de</strong>clared over the period52

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuries1910-1995) was relatively rapid (1.71%) the rural areas still witnessed a substantial growthof 398.8 thousands: 0.82 percent annually). Bear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d the east-west gradient <strong>in</strong>natural <strong>in</strong>crease evi<strong>de</strong>nt <strong>in</strong> the communist period it is remarkable to see the picture reverseddur<strong>in</strong>g 1880-1910 when the annual growth of 1.12%overall (1.86 for the towns and 1.02 forrural areas) for Banat etc. compared with 1.13 (1.99 and 0.73) for West Transylvania and0.76 (1.10 and 0.65) for the East. Pla<strong>in</strong>ly the towns were not absorb<strong>in</strong>g the surplus – <strong>in</strong><strong>de</strong>edthey saw less growth <strong>in</strong> absolute terms (322.8 thousands) than the rural areas - and althoughsome of the highest rural growth rates fell to heavily forested districts that were be<strong>in</strong>gopened up for commercial exploitation like Gura Râului (Sibiu) and Lunca Bradului(Mureş) there was still a growth of subsistence pressure. Dur<strong>in</strong>g 1857-1880 the growth wasmore mo<strong>de</strong>rate: 0.37% annually across Transylvania – aga<strong>in</strong> higher <strong>in</strong> the towns (0.74) thanthe rural areas (0.24); aga<strong>in</strong> with higher rates <strong>in</strong> the west – 0.42 (0.89 and 0.23) – than theeast: 0.32 (0.53 and 0.25). The rural areas ga<strong>in</strong>ed 50.3 thousands - slightly less than thetowns with 58.4 – and aga<strong>in</strong> west Transylvania registered a faster growth (0.42% annually)than the east (0.32).Figure 7: Settlement history of the Pătârlagele area of Romania’s CurvatureCarpathians53

David TURNOCKTable 1: Population Trends <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians of Banat-Crişana-Maramureş andTransylvania: 1857-1880 (One) and 1880-1910 (Two)Period Initial Population Absolute Growth Annual Rate PercentUrban Rural Total Urban Rural Total Urban Rural TotalBANAT-CRIŞANA-MARAMUREŞArad CountyTwo 25936 146766 172702 6791 40877 47668 +0.87 +0.93 +0.92Bihor CountyTwo 55134 130909 186043 40036 68398 108434 +2.42 +1.74 +1.94Caraş-Sever<strong>in</strong> CountyTwo 60324 192290 252614 14890 32754 47644 +1.07 +0.57 +0.63Maramureş CountyTwo 70130 107913 178043 54758 34308 89066 +2.60 +1.06 +1.67Satu Mare CountyTwo 2771 24585 27356 1446 8535 9981 +1.74 +1.16 +1.22Timiş CountyTwo 12389 52302 64691 8573 14888 23461 +2.31 +0.95 +1.21TotalTwo 226684 654765 881449 126494 199760 326254 +1.86 +1.02 +1.12TRANSYLVANIA-EASTBistriţa-Năsăud CountyOne 14563 59946 74509 3190 9996 13186 +0.95 +0.72 +0.77Two 17753 69942 87695 7178 23274 30452 +1.35 +1.12 +1.16Braşov CountyOne 65091 122610 187701 4780 -3116 1664 +0.32 -0.11 +0.04Two 69871 119494 189365 12116 18175 30291 +0.58 +0.51 +0.53Covasna CountyOne 24764 100461 125225 2974 -196 2778 +0.52 -0.05 +0.10Two 27738 100265 128003 14584 4060 18644 +1.75 +0.13 +0.49Harghita CountyOne 28908 114214 143122 5219 14385 19604 +0.78 +0.55 +0.60Two 34127 128599 162726 16855 28238 45093 +1.65 +0.73 +0.92Mureş CountyOne 10049 36606 46655 1501 3917 5418 +0.65 +0.47 +0.50Two 11550 40523 52073 2402 15188 17590 +0.69 +1.25 +1.13TotalOne 143375 433837 577212 17664 24986 42650 +0.54 +0.25 +0.32Two 161039 458823 619862 53135 88935 142070 +1.10 +0.65 +0.76TRANSYLVANIA-WESTAlba CountyOne 56778 133994 190772 5526 8764 14290 +0.42 +0.28 +0.33Two 62304 142758 205062 24077 22921 46998 +1.29 +0.54 +1.06Cluj CountyOne 37418 74841 112259 15654 8659 24313 +1.82 +0.50 +0.94Two 53072 83500 136572 36374 31240 67614 +2.28 +1.25 +1.66Hunedoara CountyOne 47247 171234 218481 10916 5963 16879 +1.00 +0.15 +0.34Two 58163 177197 235360 51653 27556 79209 +2.96 +0.52 +1.12Sălaj CountyOne 10258 45104 55362 2138 5263 7401 +0.91 +0.51 +0.58Two 12396 50367 62763 4366 16680 21046 +1.17 +1.10 +1.12Sibiu CountyOne 47943 53934 101877 6524 -3375 3149 +0.59 -0.27 +0.13Two 54467 50559 105026 26742 11728 38470 +1.21 +0.77 +1.00TotalOne 199644 479107 678751 40758 25274 66032 +0.89 +0.23 +0.42Two 240402 504381 744783 143212 110125 253337 +1.99 +0.73 +1.13TRANSYLVANIA-TOTALOne 343019 912944 1255963 58422 50260 108682 +0.74 +0.24 +0.37Two 401441 963204 1364645 196347 199060 395407 +1.63 +0.69 +0.97CARPATHIAN REGION-TOTALTwo 628125 1617969 2246094 322841 398820 721661 +1.71 +0.82 +1.07Sources: Rotariu et al. 1997a (1857 census), 1997b (1880 census) and files held by the Romanian Aca<strong>de</strong>my (1910census)54

Settlement history and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> the Carpathians <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth and n<strong>in</strong>eteenth centuriesThe 1857 census <strong>in</strong>clu<strong>de</strong>d data on the number of people absent from home at the timeof the census and the picture shows a higher rate for the towns (45.3 persons per thousand) thanthe rural areas (27.3): 32.2 overall. There is also a higher rate for the east (55.8) than the west(37.7) which applies to both urban areas (35.4 aga<strong>in</strong>st 20.1) and rural areas (40.5 aga<strong>in</strong>st 25.3).However <strong>in</strong> some localities the rates were extremely high - 191.5 for the Bran district ofBraşov, 117.0 for the Sălişte district of Sibiu and 90.1 for the town of Braşov – while <strong>in</strong> manyother areas the rates were <strong>in</strong>significant. We therefore have a picture of local ‘highs’ <strong>in</strong> terms ofabsence <strong>in</strong> connection with tra<strong>de</strong> or transhumance pastoralism compared with near-total<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce on local subsistence elsewhere. Low growth dur<strong>in</strong>g 1857-1880 could then havearisen <strong>in</strong> part from the breakdown of long-wave transhumance and the migration of ‘Ungureni’across the Carpathians to Wallachia: a migration cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g from the 18th century but alwaysdifficult to quantify (Popp 1942). However whereas 1857-1880 saw 28 of the 99 rural districtslose population (13 <strong>in</strong> the east of which 12 were <strong>in</strong> Braşov and Covasna counties; and 15 <strong>in</strong> thewest – mostly from Hunedoara and Sibiu counties) there were only six cases for 1880-1910;while conversely there were 34 grow<strong>in</strong>g annually by 1.0 percent or more <strong>in</strong> the later periodcompared with only 12 <strong>in</strong> the first period. There is no space to discuss the census results furtherbut they provi<strong>de</strong> a context for the follow<strong>in</strong>g case study.The Romanian Carpathians: Mărg<strong>in</strong>enii Sibiului. The scale of adjustment ma<strong>de</strong> bypeasant communities is well exemplified by this district when long-wave transhumanceencountered restrictions <strong>in</strong> Dobrogea <strong>in</strong> 1865, followed by some severe w<strong>in</strong>ters <strong>in</strong> the1870s, particularly <strong>in</strong> 1875. Tighter bor<strong>de</strong>r controls prevented entry to Bulgaria <strong>in</strong> 1879 andthe customs wars between Romania and the Habsburg Empire broke out dur<strong>in</strong>g 1885-91when Romania’s <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> protect<strong>in</strong>g domestic <strong>in</strong>dustry affected her agricultural exportsand resulted <strong>in</strong> less favourable bor<strong>de</strong>r regulations. Some shepherds moved on <strong>in</strong> the 1870sand 1880s to work seasonally <strong>in</strong> Bessarabia with the flocks of large landowners - travell<strong>in</strong>gvia Bistriţa and Bucov<strong>in</strong>a, while return<strong>in</strong>g with payment <strong>in</strong> wool (for use <strong>in</strong> the textile<strong>in</strong>dustry at home) via a more circuitous route via L’viv, Debrecen, Ora<strong>de</strong>a and Cluj to avoidRomanian customs duties by pass<strong>in</strong>g directly from Russian to Habsburg territory. But woolroads ('drumul lânii') such as the one through the Trotuş valley and Braşov provi<strong>de</strong>d theopportunity of pick<strong>in</strong>g up salt on the way. Some pastoralists pushed on to the open spacesof Crimea and Caucasus (head<strong>in</strong>g eastwards from Sul<strong>in</strong>a) for a more congenialenvironment avoid<strong>in</strong>g the hard w<strong>in</strong>ters and dry summers <strong>in</strong> Bessarabia and reap<strong>in</strong>g goodprofits for a ten year absence from home.Another late 19th century strategy was to give up sheep rear<strong>in</strong>g and turn toit<strong>in</strong>erant peddl<strong>in</strong>g ('comerţ ambulant') sell<strong>in</strong>g locally-produced goods - and others too -along the familiar routes: northeastwards through Transylvania to Târgu Mureş, Bistriţa,Suceava and Černivci and Bolgrad; eastwards through Braşov and the Oituz Pass to Tecuciand thence towards the Black Sea coast via Galaţi and Ismail or else to Chiş<strong>in</strong>ău andTigh<strong>in</strong>a; southwards to the Danube at Turnu Sever<strong>in</strong>, Calafat or Turnu Măgurele (follow<strong>in</strong>gthe river downstream to Cernavodă <strong>in</strong> the latter case); or southeastwards through Piteşti toBucharest. They also set up as craftsmen and tra<strong>de</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> the towns of southern Transylvaniaor northern Wallachia and <strong>in</strong> several rural areas around Bistriţa and Târgu Mureş <strong>in</strong>Transylvania, Slat<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> Oltenia and further east around Brăila, Galaţi, Huşi and Tulcea(Dragomir 1925; 1938). While the women did not normally go beyond the limits ofTransylvania, the men would travel down the Olt valley to the Danube, perhaps with 60-70carts sett<strong>in</strong>g off at the same time. Meanwhile at home there was more <strong>in</strong>tensive pastoralism55