Turkish-Armenian Intermarriages in Bulgaria Svetlina Denova, Ph.D ...

Turkish-Armenian Intermarriages in Bulgaria Svetlina Denova, Ph.D ...

Turkish-Armenian Intermarriages in Bulgaria Svetlina Denova, Ph.D ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Turkish</strong>-<strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Intermarriages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bulgaria</strong>Svetl<strong>in</strong>a <strong>Denova</strong>, <strong>Ph</strong>.D. student, Institute of folklore, <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n Academy of SciencesThe follow<strong>in</strong>g text focuses on a specific sphere of <strong>Turkish</strong>-<strong>Armenian</strong> relations, thatconcern<strong>in</strong>g marriage. <strong>Intermarriages</strong> are reality <strong>in</strong> almost every ethnic group. And no matterof the traditional antagonistic feel<strong>in</strong>gs between Turks and <strong>Armenian</strong>s there is enoughevidence for the researcher that such marriages presented both <strong>in</strong> the past and the present. Ofcourse there is not a tendency, neither <strong>in</strong> <strong>Turkish</strong>, nor <strong>in</strong> <strong>Armenian</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bulgaria</strong> thesemarriages to be many. They are just a few, scattered through the years. But their existence isimportant for the researcher, because marriage is one of the social spheres where the ethnicdifferences are simultaneously visible and <strong>in</strong>visible. “As a culture communication laboratory,the <strong>in</strong>terethnic household can be a privileged place where tolerance is daily tested, but also amagnify<strong>in</strong>g mirror reflect<strong>in</strong>g misunderstand<strong>in</strong>gs and <strong>in</strong>terethnic conflicts. In any case it bestreveals the relations between the groups to which the spouses belong”. (Streiff-Fenard 1989)Do<strong>in</strong>g my research of <strong>in</strong>termarriages <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bulgaria</strong> <strong>in</strong> general, I encountered a couple ofcases of <strong>Turkish</strong>-<strong>Armenian</strong> marriages. But statistics is one th<strong>in</strong>g, while do<strong>in</strong>g a research <strong>in</strong>both <strong>Turkish</strong> and <strong>Armenian</strong> community <strong>in</strong> attempt to study these cases is another. Dur<strong>in</strong>g ayear-and-a-half field research <strong>in</strong> Plovdiv, the second city <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bulgaria</strong>, I tried to make<strong>in</strong>terviews, as many as I can, with people engaged <strong>in</strong> such marriages. I succeeded however <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>g just two couples present<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Turkish</strong>-<strong>Armenian</strong> marriages <strong>in</strong> the city.The text here can be viewed as consist<strong>in</strong>g of two case studies - a perspective that can be seen<strong>in</strong> a larger quantitative context. Us<strong>in</strong>g thee two approaches – the qualitative and thequantitative one – the study of the <strong>Turkish</strong>-<strong>Armenian</strong> marriages <strong>in</strong> Plovdiv can be moreefficient.

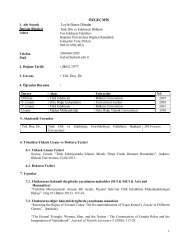

<strong>Turkish</strong> and <strong>Armenian</strong> Communities <strong>in</strong> the CityPlovdiv has been a traditionally multiethnic and multi-religious city. For centuriesGreeks, Jews, <strong>Armenian</strong>s and Gypsies have been some of its ever-present m<strong>in</strong>orities.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to some authors (Генчев 1981; Колева 1965; Пеев 1941; Шишков 1926; Гяуров1899) <strong>Armenian</strong>s had lived <strong>in</strong> the city long before com<strong>in</strong>g of the Turks. Plovdiv was capturedby Lala Shah<strong>in</strong> Pasha <strong>in</strong> 1363/1364. In XVI century there appeared radical changes <strong>in</strong> thedemography of the city. From <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n (with dom<strong>in</strong>ant Christian population) it turned <strong>in</strong>to a<strong>Turkish</strong> city (with dom<strong>in</strong>ant Muslim population). Evliya Chelebi (1651-1654) found the citywith 23 Muslim neighbourhoods (mahalle) and 7 others. More precise data about <strong>Turkish</strong> and<strong>Armenian</strong> population <strong>in</strong> Plovdiv can be obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the official censuses after 1878.Year of the censusTotal population ofTurks<strong>Armenian</strong>sPlovdiv1882 - 4 146 8871883 24 053 5 558 8061884 33 442 7 144 1 0611888 33 032 5 615 9031892 36 033 6 381 1 0241900 43 033 4 706 1 9421905 45 707 4 852 2 0971910 47 981 2 946 1 8471920 63 115 5 605 2 4561926 84 655 4 748 6 0881934 99 883 6 102 6 200

1939 101 984 6 462 6 5911946 126 563 7 466 5 5581956 161 836 6 305 5 6431965 229 043 4 380 5 5061975 299 638 No ethnic affiliation No ethnic affiliation1985 342 050 No ethnic affiliation No ethnic affiliation1992 341 058 17 041 3 9032001 338 224 22 501 3 083<strong>Turkish</strong>-<strong>Armenian</strong> Relations <strong>in</strong> the Past and Present“History has been history of the past. It does not mean that if there was hate betweenpeople <strong>in</strong> the past, we should still live <strong>in</strong> this” – said and old <strong>Armenian</strong> woman when I askedher about the relations between Turks and <strong>Armenian</strong>s <strong>in</strong> general.The case of <strong>in</strong>termarriage is a way this heavy past to be overcome. “The most horribleth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> my family was when one of my husband’s cous<strong>in</strong>s married a <strong>Turkish</strong> <strong>in</strong> the 50’s. Herfather was a colonel dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n war aga<strong>in</strong>st Turkey and just several decades latershe married her teacher <strong>in</strong> history, who was <strong>Turkish</strong>. Then my family said – the <strong>in</strong>formercont<strong>in</strong>ues – ‘We had seen many th<strong>in</strong>gs, but never had a <strong>Turkish</strong> <strong>in</strong> our k<strong>in</strong>’. This marriagewas very pa<strong>in</strong>ful for them. But I remember that this man was handsome and very charm<strong>in</strong>gand for a couple of years the problem had been solved and for everyone he became thefavorite son-<strong>in</strong>-law.A <strong>Turkish</strong> <strong>in</strong>former tells another story: “When I was <strong>in</strong> the high-school I had agirlfriend who was an <strong>Armenian</strong>. She always wanted to speak with me. You know,<strong>Armenian</strong>s usually speak <strong>Turkish</strong>. And I don’t know, there was not any difference betweenus, and I can even say that there was some attraction between Turks and <strong>Armenian</strong>s”. An

<strong>Armenian</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ues <strong>in</strong> other story the same problem: “We differ <strong>in</strong> our normative values. It issometh<strong>in</strong>g that comes from our different civilizations – the Christian and the Muslim one –but at the same time there are common virtues, I can call them common Asian virtues. One ofthem is the virtue of family”. The same <strong>Armenian</strong> told me a funny story. “I’m work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> amarket with Turks and Gypsies and because I know <strong>Turkish</strong> well some of them often come tospeak with me. On educational level we differ but on the level of human relations we do nothave any problems. At one of their Bayrams some of the little boys came to me and wanted tokiss my hand. I didn’t know at that time that it is usual for the Muslims to kiss the hand of anelder man dur<strong>in</strong>g the Bayram. I asked them: ‘What are you do<strong>in</strong>g?’ and they answered me –‘You’re our millet, aren’t you?’ They decided that I was <strong>Turkish</strong> just because I was speak<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Turkish</strong>”.But not all <strong>in</strong>formers’ stories are so optimistic. I’ve heard many stories about themassacres of <strong>Armenian</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the end of XIX and the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of XX century. Some of themsound really om<strong>in</strong>ous. “My grandfather <strong>in</strong> Turkey... they slaughtered his mother and hisfather before him, because he didn’t want to go soldier and fight aga<strong>in</strong>st his brothers andsisters. Hav<strong>in</strong>g seen all this my grandfather became a member of a revolutionary detachmentand afterwards chief of one of them. The deaths of 72 Turks and 1 <strong>Armenian</strong>, who could notbe an <strong>Armenian</strong> any more, are weigh<strong>in</strong>g on his conscience”. Another statement puts the<strong>Armenian</strong>s and <strong>Bulgaria</strong>ns side by side aga<strong>in</strong>st Turkey: “<strong>Armenian</strong> people has always beengrateful to the <strong>Bulgaria</strong>ns, because we never differ <strong>in</strong> our faiths. What united us <strong>in</strong> the pastwas our common enemy – Turkey”.I heard also stories of good friendships between Turks and <strong>Armenian</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the past andalso <strong>in</strong> the years of the massacres. A <strong>Turkish</strong> friend of an <strong>Armenian</strong> understood that his fatheris def<strong>in</strong>ed to kill the <strong>Armenian</strong>s <strong>in</strong> their neighbourhood. He told his friend the news <strong>in</strong>advance and thus saved the life of his friend and his family. Another story is about an

adoption of an <strong>Armenian</strong> boy by a rich childless governor of a village. This happened dur<strong>in</strong>gthe hard time for the <strong>Armenian</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the Ottoman Empire. There are also stories of neighboursTurks who saved <strong>Armenian</strong> lives.The study of two casesThe first case is a marriage between an <strong>Armenian</strong> man and a <strong>Turkish</strong> woman. Theman was born <strong>in</strong> the city of Plovdiv, while the woman’s birthplace is a village <strong>in</strong> the districtof Kircali (a <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n region with great number of <strong>Turkish</strong> population). They married <strong>in</strong>1981. The family lives <strong>in</strong> their own flat only with their daughter. The husband’s relatives livealso <strong>in</strong> the city and the relative l<strong>in</strong>ks between them and the family has never been stopped.But now they are not so <strong>in</strong>tensive as they were <strong>in</strong> the first years of the marriage when thefamily lived together with the parents of the husband and the daughter was little. The wife’srelatives live <strong>in</strong> their native village.The second case is a marriage between a <strong>Turkish</strong>, born <strong>in</strong> a village <strong>in</strong> the region ofPlovdiv, and an <strong>Armenian</strong> woman, born <strong>in</strong> Plovdiv. The couple married <strong>in</strong> 1996. The familylives <strong>in</strong> Plovdiv <strong>in</strong> their own flat together with their little daughter and two of wife’s relatives– her mother and her sister. Husband’s relatives live <strong>in</strong> their native village.I shall start with the similarities between the two cases. But because it is not alwayspossible to stick to them, I shall show the differences as well.How did the parents of both sides accept the decision of their children to marry? Inthe first case aga<strong>in</strong>st the marriage were just the wife’s parents. The wedd<strong>in</strong>g was <strong>in</strong> Plovdivand no one of wife’s parents or relatives came for the celebration. The wife’s brother andsister were more opposed to it than their parents. The wife usually goes to visit her parents,while the relations with her brother and sister were re-established three or four years after thewedd<strong>in</strong>g. The warm<strong>in</strong>g of the relative l<strong>in</strong>ks happened with the birth of the child. In the

second case aga<strong>in</strong> the wife’s parents were aga<strong>in</strong>st the marriage. The connections between thewife and her family broke off and they were re-established <strong>in</strong> two or three months, when thenews of her pregnancy was told to the parents. After this critical period of disconnection withparents and relatives, <strong>in</strong> the first case for years, <strong>in</strong> the second for months, the connections arere-established. The appearance of the child <strong>in</strong> both cases is the strongest motive for this.It is typical for the two families to celebrate the festivals of the two communities.Easter, Christmas and Kurban Bayram and Ramadan Bayram are always celebrated. I wassurprised to see the unique balance between the Christian and Muslim celebrations. Commonfestival for the two families is New Year’s Eve. For the <strong>Turkish</strong> celebrations – the twoBayrams, the family usually goes to its <strong>Turkish</strong> relatives <strong>in</strong> the village.What happens with the name of the child? In the first case the daughter is named afterthe name of the mother-<strong>in</strong>-law (the husband’s mother). It is a tradition for both <strong>Armenian</strong>sand Turks to name the child after the husband’s parents. Such is also the case here. In thesecond case the daughter is named after the father-<strong>in</strong>-law (the wife’s father). This can beexpla<strong>in</strong>ed with the fact that for the period of the pregnancy the family had lived together withwife’s parents.The language of the two families is <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n. But <strong>in</strong> the two cases it is mentionedthat the older relatives of the <strong>Armenian</strong> husband or wife can speak <strong>Turkish</strong>. The child <strong>in</strong> thefirst case doesn’t know <strong>Turkish</strong> but she goes to <strong>Armenian</strong> school and can “read, write andtranslate <strong>Armenian</strong>”. It is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g however that although the daughter has certa<strong>in</strong>knowledge of <strong>Armenian</strong>, she actually cannot speak it. The language of the family is<strong>Bulgaria</strong>n. That’s the language of the husband’s parents, too. <strong>Turkish</strong> and <strong>Armenian</strong> speakonly the great-grandparents of the child. In the second case the child goes to a k<strong>in</strong>dergartenwhere there are special hours once a week <strong>in</strong> <strong>Armenian</strong>. But the child knows just a few words<strong>in</strong> <strong>Armenian</strong>. The language of the family is aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n. The old husband’s relatives

however cannot speak <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n, their only language is <strong>Turkish</strong>, so the <strong>Armenian</strong> wifestarted speak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Turkish</strong>, because once a month for a week her daughter stays with the greatgrandmothersof the husband <strong>in</strong> the village. The child already speaks <strong>Turkish</strong> but it isashamed if speak<strong>in</strong>g the language with his father. <strong>Turkish</strong> is the language for communicationwith the grannies <strong>in</strong> the village and for watch<strong>in</strong>g cartoons from the <strong>Turkish</strong> TV channels.What is the religion of the child? In the first case the child is baptised <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Armenian</strong>Apostolic Church <strong>in</strong> Plovdiv. It is surpris<strong>in</strong>g however that mother forbids her daughter tomake a cross when she is watch<strong>in</strong>g her. The mother says that she is a Muslim, but goes tochurches, lights candles and prays there, she just doesn’t make cross. In the second case theparents decided to leave the child to make her own choice when she grows up. No baptismwas made.ConclusionThese two cases of <strong>Turkish</strong>-<strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>in</strong>termarriages are examples how prejudicescan be overcome and a new family life can be established <strong>in</strong> a sphere where the connectionbetween Turks and <strong>Armenian</strong>s was absolutely impossible.

BibliographyGenchev, N. 1981. Plovdiv <strong>in</strong> the Renaissance. (In <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n)Gyaurov, A. 1899. Short Notes about the Past and Present of Plovdiv. (In <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n)Koleva, E. 1965. Changes <strong>in</strong> the Ethnic Population of Plovdiv. –In: Annual ofPlovdiv’s museums, 4, 63-77. (In <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n)Peev, V. 1941. Plovdiv – Past and Present. (In <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n)Shishkov, St. 1926. Plovdiv <strong>in</strong> the Past and Present. (<strong>in</strong> <strong>Bulgaria</strong>n)Streiff-Fenard, J. 1989. Les couples franco-maghreb<strong>in</strong>s en France, Paris:L’Harmattan.