Greek Bronzes: In The Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Metropolitan ...

Greek Bronzes: In The Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Metropolitan ...

Greek Bronzes: In The Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Metropolitan ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

5tAC?; ~

BY JOAN R. M\ERTENS

Bulletin~,:- ,i,IE')~~~~~~~~~,_~~~~~a1985FallE'~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~i<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Bulletin ®www.jstor.org

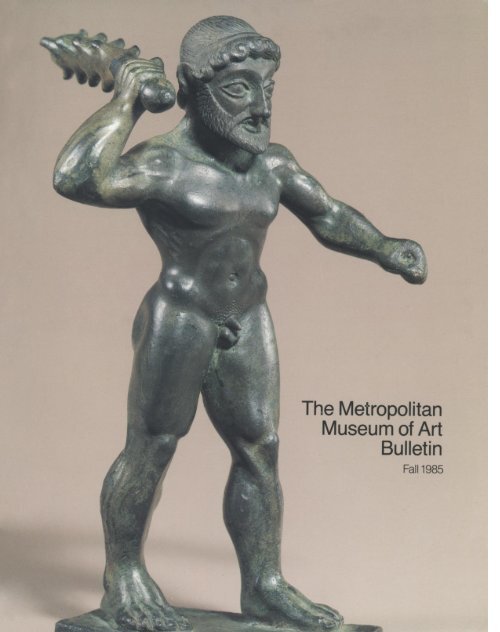

FRONT covE: Herakles (no. 14), last quarter <strong>of</strong> the sixth century B.C.INSIDE FRONT COVER: Head <strong>of</strong> a griffin (no. 9), third quarter <strong>of</strong> the seventh century B.C.BACK COVER: Hermes (no. 43), first century B.C. to first century A.D.<strong>The</strong> translations are based upon those <strong>of</strong> the Loeb Classical Library.Reprinted from <strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Bulletin (Fall 1985). ? 1985 by <strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong><strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>. Photography by Walter J. F. Yee, <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Photograph Studio.Design: Peter Oldenburg<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Bulletin ®www.jstor.org

S ince antiquity the Age <strong>of</strong> Bronze has been customarily characterized as a rude sequel to theglorious ages <strong>of</strong> gold and silver. This third generation <strong>of</strong> mortals created by the gods on MountOlympos was, according to Hesiod, "a brazen race, sprung from ash-trees; ... in no way equal to [thepreceding] silver age, but was terrible and strong." Lovers <strong>of</strong> violence, they developed unconquerablestrength. <strong>The</strong>ir armor was <strong>of</strong> bronze, their houses <strong>of</strong> bronze, and they used bronze implements. <strong>The</strong>irbrutality was such that they destroyed themselves. Given Hesiod's description, one might expect thatfrom this early time <strong>Greek</strong> bronze workers devoted themselves to the production <strong>of</strong> weapons andarmor. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>'s collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> bronzes provides striking evidence to the contrary. Out <strong>of</strong>the durable medium <strong>of</strong> bronze skilled <strong>Greek</strong> craftsmen created some <strong>of</strong>the most beautiful and memorableworks in the history <strong>of</strong> Western art. Graceful figures, charming animals, luxurious utensils, andhandsomely decorated armor were all fashioned with great sensitivity from bronze.While ancient literary sources tell us that many bronzes were melted down-as were objects <strong>of</strong> goldand silver-a far greater number <strong>of</strong> works survive than those made <strong>of</strong> more precious metals. It takes asharp eye, perseverance, an innate sense <strong>of</strong> quality, and careful scholarship to form a first-rank collection<strong>of</strong> bronzes. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> has been fortunate to have had the support <strong>of</strong> knowledgeabledonors as well as an inspired curatorial staff in assembling a group <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> bronzes that is one <strong>of</strong>the finest and richest anywhere.<strong>The</strong>re was no question <strong>of</strong> presenting the collection here in its entirety; indeed, in order to allow forplentiful illustrations, only forty-four pieces were selected for inclusion in this Bulletin. Chosen for theirexceptional quality and their historic or iconographic interest, these bronzes span the history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong>art from the eighth century B.C. to Roman times. Most <strong>of</strong> them are small objects, and here, reproducedin several views, they can be fully appreciated as impressive sculptures. For example, the little centaur(no. 26) hurls his rock with all the force <strong>of</strong> his larger counterparts, despite the fact that he is only oneand three-quarters inches high.As distinguished as the works themselves are many <strong>of</strong> the collectors who at one time or anotherowned these objects. Foremost among them is the late Walter C. Baker, whose bequest in 1971brought a bounty <strong>of</strong> masterpieces, the best known being the veiled dancer (no. 32); ten worksfrom his collection are included in this publication. Other distinguished connoisseurs <strong>of</strong> bronzesrepresented by works reproduced on these pages are Count Michael Tyszkiewicz and VladimirSimkhovitch. An accomplished museum curator ranks with these discerning private collectors. UnderDietrich von Bothmer, Chairman <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> and Roman <strong>Art</strong>, significant objects havebeen added to our holdings, including the majestic rams (no. 17) and the poignant artisan (no. 41).Norbert Schimmel has been a true friend <strong>of</strong>the department-in this area as in many others-allowingus to exhibit his grand Dionysiac mask (no. 40) alongside the <strong>Museum</strong>'s two masks (nos. 38,39) inthe galleries.I wish to express my gratitude to the anonymous donor <strong>of</strong> the Classical Fund and to GeorgeOrtiz for enabling the <strong>Museum</strong> to publish this Bulletinas full and generously illustrated fashion asit is. Written by Joan R. Mertens, Curator and Administrator <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> and Roman<strong>Art</strong>, this issue is intended as an introduction to <strong>Greek</strong> bronzes-revealing their variety, their quality<strong>of</strong> execution, and the pleasure <strong>of</strong> viewing them. I hope that it will encourage readers to make a leisurelyvisit to the galleries-or several visits-and to take the time to thoroughly study and enjoythese masterpieces. It is also my hope that in the near future their present installation in the <strong>Metropolitan</strong>,which has been provisional for all too long, will be changed to one that is worthy <strong>of</strong> thesesplendid bronzes.Philippe de MontebelloDirector<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Bulletin ®www.jstor.org

INTRODUCTION"And your own images in Greece, how are they fashioned?... Your artists, then,like Phidias and like Praxiteles went up, I suppose, to heaven and made a model<strong>of</strong> the forms <strong>of</strong> the gods and then reproduced them by their art, or was theresomething else that attended upon them as they did their molding?""<strong>The</strong>re was," said Apollonius, "something else, full <strong>of</strong> wisdom [sophia].""What was that," said the other, "for surely you would not say that it was somethingother than imitation [mimesis]?""Imagination[phantasia],"he said, "wrought these works, a wiser craftsman thanimitation; for imitation crafts what it has seen, while imagination crafts what ithas not seen; for it conceives according to the standard <strong>of</strong> what exists. Shock<strong>of</strong>ten deadens imitation, but nothing affects phantasy, which marches undauntedtoward the goal that it has set itself"Flavius Philostratus, <strong>The</strong> Life <strong>of</strong> Apollonius <strong>of</strong> Tyana (6.19)<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Bulletin ®www.jstor.org

K( een observation combined with seemingly inexhaustible creativity is ahallmark <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> art in all <strong>of</strong> its forms. Nowhere does it impress us more immediately,however, than in the statuettes and utensils <strong>of</strong> bronze that were an integralpart <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> life. <strong>The</strong>y survive from the ninth century B.C. through the period <strong>of</strong>assimilation to Roman styles that began during the second century B.C. Althoughthe paintings on <strong>Greek</strong> vases <strong>of</strong>fer pictures <strong>of</strong> contemporary men, women, andchildren-what they did and how they visualized their gods and heroes-bronzestatuettes have the property <strong>of</strong> being three-dimensional, <strong>of</strong> being palpably real.While large-scale sculpture survives, much <strong>of</strong> it consists <strong>of</strong> copies after originalsthat no longer exist. <strong>The</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> bronze statuettes, by contrast, have the distinction<strong>of</strong> being the original works that the ancient artists made.When these artists dealt with things that they saw around them-humanbeings, animals, utensils-our admiration is directed particularly to the way inwhich they captured and depicted the distinctive qualities <strong>of</strong> the subject. Whatwe may not sufficiently consider today is the tangible form that the craftsmengave to a wide range <strong>of</strong> subjects upon which no one had ever set eyes: the heroHerakles, the goddess Athena, Eros, the personification <strong>of</strong> love, griffins, centaurs,and satyrs, to mention only examples that occur here. While these inhabitants <strong>of</strong>the imagination acquired attributes by which to be recognized-the club andlion skin <strong>of</strong> Herakles, for instance-every artist contributed his own interpretation.<strong>The</strong> resulting statuettes are <strong>of</strong>ten memorable because the form perfectlysuits the subject and the articulation is so precise that, thanks to our eyes and fingertips,we have a real presence before us.<strong>The</strong> bronzes represent one <strong>of</strong> two kinds <strong>of</strong> object: either they were made to befreestanding, in which case they normally stand on their own base, or they werethe decorative adjuncts to a utensil. <strong>The</strong>ir beauty might suggest that in antiquity,as in modem times, they were collected and enjoyed for their own sake. <strong>In</strong> fact,they were intended to serve a purpose, their aesthetic qualities being secondary.Through the fifth century B.C., at least, freestanding figural bronzes were producedas dedications, <strong>of</strong>ferings to a god frequently placed in a sanctuary andinscribed with a text to that effect; the lyre player (no. 15), for instance, hasinscribed on the back, "Dolichos dedicated me." <strong>The</strong> hydria, or water jar (no.23), shows engraved around the top <strong>of</strong> the mouth, "one <strong>of</strong> the prizes from ArgiveHera." Such utilitarian objects, actually made to be used, might ultimately also bededicated as <strong>of</strong>ferings.<strong>The</strong>se two considerations-that the objects had a function to perform and thata figure <strong>of</strong> a human or an animal could be integrated naturally into a utensil-areabsolutely basic to an understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> bronzes. <strong>The</strong> artist's hand in theservice <strong>of</strong> his eye fashioned the upper body <strong>of</strong> a woman (opposite) that isimmediately recognizable and remarkable for the articulation <strong>of</strong> her face, garment,and hair. His hand working in the service <strong>of</strong> his imagination leaves us withno sense <strong>of</strong> discomfort or incongruity that she forms the transition between themouth and handle <strong>of</strong> a water jar. <strong>The</strong> figure embellishes the utensil; the utensilgives purpose to the figure. Moreover, as the object is used, the mutually reinforcingthree-dimensionality <strong>of</strong> vase and figure comes to the fore.By the eighth century B.C., the date <strong>of</strong> the earliest object in this Bulletin, bronzeworking had already enjoyed a long history in the <strong>Greek</strong> world. <strong>In</strong>deed, theAbove: Detail <strong>of</strong> the hydria (no. 23)showing the inscriptionOpposite: Woman at the handle <strong>of</strong>the hydria5

Bronze Age is the name conventionally applied to the latest period <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> prehistory,about 3200 to 1200 B.C. Preserved objects and ancient literary sources testifyto the use <strong>of</strong> other metals at that time: gold, silver, lead, tin, electrum, and,rarely, iron. Bronze, the alloy composed <strong>of</strong> approximately 90 percent copper and10 percent tin, by far predominated, however, for weapons, tools, and vessels, aswell as for statuettes. Among the available metals, it was the hardest and strongest;at the same time, it could be formed into complex shapes, like fishhooks.<strong>The</strong> technology <strong>of</strong> preparing the alloys, <strong>of</strong> casting or hammering the object, and<strong>of</strong> finishing it had been fully mastered so that, in this respect, there were noobstacles to production. (A description <strong>of</strong> how bronzes were made appears atthe end <strong>of</strong> this essay.) <strong>The</strong> most common material for containers, loom weights,dedicatory objects, and other necessities <strong>of</strong> daily life was fired clay. Wheredurability and/or the distinction <strong>of</strong> a rarer material came into play, bronzewas used.Archaeological investigation makes it possible to follow the evidence forbronze working back into the fourth millennium B.C. Yet, it is really only in thepoems <strong>of</strong> Homer, who is generally believed to have lived during the eighth centuryB.C., that we are given a social and human context within which to relate thesurviving material. <strong>The</strong> poet, for instance, vividly describes a forge in the course<strong>of</strong> recounting how <strong>The</strong>tis went to the divine smith Hephaistos to obtain a secondset <strong>of</strong> armor for her son Achilles.So saying he left her there and went to his bellows, and he turned these towardthe fire and bade them work. And the bellows, twenty in all, blew upon the meltingvats, sending forth a ready blast <strong>of</strong> every force, now to further him as helabored hard, and again in whatsoever way Hephaistos might wish and his workgo on. And on the fire he put stubborn copper and tin and precious gold and silver;and thereafter he set on the anvil-block a great anvil, and took in one hand amassive hammer, and in the other he took the tongs (Iliad 18.468-477).Homer lived about five hundred years later than the Trojan War and its aftermathtreated in his poems. While perhaps not so barren as once thought, theintervening centuries produced virtually no great art in any form. During thetenth century, however, artistic creativity reawakened and, by 750 B.C., the prevailingstyle, called "Geometric" in modem scholarship, was reaching its apogee.<strong>The</strong> name derives from such simple geometric shapes as triangles, circles, andrectangles that were used as filling ornament as well as elaborated into the subjects<strong>of</strong> figural scenes. Vase painting and bronze working were the primarymedia.<strong>The</strong> Geometric period (about 1000-700 B.C.) is <strong>of</strong> considerable importance forbronze working. First, it introduces many figure types that remained in the repertoirefor centuries. <strong>The</strong> male occurs in various guises-nude, as a warrior, or as avotary. <strong>The</strong>re are animals, notably horses and birds, as well as mythical creaturessuch as centaurs and griffins. Most remarkable is the style, which presents anygiven subject in its most elemental form, practically devoid <strong>of</strong> detail. Thus, statuettes<strong>of</strong> horses (nos. 3,4) show us little more than essentials: the head, archingneck, body, four legs, and tail that anyone would enumerate in describing thecreature. Similarly, an armorer (no. 8) consists fundamentally <strong>of</strong> the torso andlimbs <strong>of</strong> a human figure disposed so that his legs indicate that he is sitting on theground and his upper body and arms are directed toward the helmet before him.<strong>The</strong> manner <strong>of</strong> representation is perfectly clear and immediate, <strong>of</strong>ten also consummatelyelegant. <strong>The</strong> basic <strong>Greek</strong> iconographical types were born, so to speak,in the simplest, most expressive forms possible.A second significant feature <strong>of</strong> Geometric bronze work is that it documents the6

asic ways <strong>of</strong> using the material: in three dimensions, for statuettes and utensils;in relief to decorate objects such as tripod cauldrons, which were popular at thistime; and as the surface for incised decoration, best illustrated by a class <strong>of</strong> fibula,or safety pin. Thus, in the revival that took place during the early first millenniumB.C., the various possibilities for artistic expression developed hand in hand withsubject and style.A third significant aspect <strong>of</strong> Geometric bronzes concerns the geographical centerswhere, on the one hand, works were produced and where, on the other,they were particularly favored as dedications. Although scholars may disagree onthe localization <strong>of</strong> a specific object, there is little doubt that major centers <strong>of</strong> productionexisted in Laconia, the Argolid, Corinth, Attica, Boeotia, and <strong>The</strong>ssaly, aswell as on Crete and other islands. <strong>The</strong> single most important sanctuary at whichGeometric bronzes were dedicated is Olympia, but major concentrations <strong>of</strong>material have also come to light in Athens, Sparta, Delphi, the Argive Heraion,and on Samos. (See map on p. 14.)However one approaches these early works-technically, iconographically,geographically-they are very much at the head <strong>of</strong> a long tradition. <strong>The</strong>y enjoythe additional distinction <strong>of</strong> representing probably the most progressive area <strong>of</strong>sculptural creativity in their day. Apart from primitive images <strong>of</strong> wood describedin literary sources, there was no large-scale sculpture, and contemporary terracottascannot match the effect <strong>of</strong> volume and vitality in a work like the man andcentaur (no. 7). It is quite fair to say that for roughly a hundred years, until theend <strong>of</strong> the eighth century B.C., bronzes were at the forefront <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> sculpturaldevelopment.<strong>The</strong> Archaic period, which is conventionally dated from about 700 B.C. to thePersian sack <strong>of</strong> the Athenian Akropolis in 480 B.C., saw the first flowering <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong>sculpture in stone, terracotta, and bronze. Our knowledge <strong>of</strong> artistic developmentsis enhanced by ancient literary evidence, <strong>of</strong> which two passages are particularlypertinent to bronzes: they are from the history <strong>of</strong> the Persian Wars writtenby Herodotos, who lived in the fifth century B.C., and they give us a point <strong>of</strong>chronological reference through the mention <strong>of</strong> Croesus, king <strong>of</strong> Lydia, whoreigned from about 561 to 546 B.C. <strong>The</strong> objects described in the quotations; theglimpse into relations between Sparta, Lydia, and Samos, three important statesthat were also centers <strong>of</strong> metalworking; the colorful exaggeration <strong>of</strong> theaccounts-all <strong>of</strong> these features provide a fitting introduction to this time <strong>of</strong> spectacular,perhaps even unparalleled, achievement in <strong>Greek</strong> bronze working. (<strong>In</strong>the quotation, the Lacedaemonians are the people <strong>of</strong> Lacedaemon, the regionwith its center at Sparta; "Laconia" is a short variant <strong>of</strong> Lacedaemon.)<strong>The</strong> Lacedaemonians declared themselves ready to serve Croesus, king <strong>of</strong> Lydia,when he should require, and moreover they made a bowl <strong>of</strong> bronze, with figuresin relief outside round the rim, and large enough to hold twenty-seven hundredgallons.... <strong>The</strong> bowl never came to Sardis, and for this two reasons are given: theLacedaemonians say that when the bowl was near Samos on its way to Sardis, theSamians descended upon them in warships and carried it <strong>of</strong>f; but the Samiansthemselves say that the Lacedaemonians who were bringing the bowl, being toolate, and learning that Sardis and Croesus were taken, sold it in Samos to certainprivate men, who set it up in the temple <strong>of</strong> Hera. And it may be that the sellers <strong>of</strong>the bowl, when they returned to Sparta, said that they had been robbed <strong>of</strong> it bythe Samians (<strong>The</strong> Persian Wars 1. 70).<strong>In</strong> another passage, Herodotos tells <strong>of</strong> a dedication made by a group <strong>of</strong>Samians with a tithe <strong>of</strong> their pr<strong>of</strong>its reaped from a trading voyage to southernSpain, probably for ores: "<strong>The</strong> Samians took six talents... and made therewith a7

Copper ingot, twelfth century B.c. RogersFund, 1911 (11.140.7)bronze vessel, like an Argolic krater, with griffins' heads projecting from the rimall around; this they set up in their temple <strong>of</strong> Hera, supporting it with threecolossal kneeling figures <strong>of</strong> bronze, each seven cubits high" (4.152).An important fact brought out by these passages is how Archaic bronzes, fromtheir production to their distribution, effectively linked one end <strong>of</strong> the Mediterraneanworld to the other. To begin with the metal ores required for the bronzeindustry, copper was mined at Chalkis on Euboea, in Macedonia, in <strong>The</strong>ssaly, onvarious islands (most conspicuously Cyprus), as well as in southwestern Spainand northern Italy; a copper ingot in the <strong>Museum</strong>'s collections, probably <strong>of</strong> thetwelfth century B.C., shows one <strong>of</strong> the forms in which ores were transportedthroughout antiquity. Tin had to be imported from Britain and Spain. Dangerousas these expeditions must have been, the rewards were handsome, as indicatedby Herodotos's account <strong>of</strong> the tithe in the form <strong>of</strong> a griffin cauldron dedicated bythe Samians.While Herodotos particularly highlights Laconia and Samos in the selectionscited, the number <strong>of</strong> places where the raw materials were made into objects continuedto proliferate, throughout the <strong>Greek</strong> mainland and islands as well as fartherafield. <strong>In</strong> the west there were workshops in the <strong>Greek</strong> colonies <strong>of</strong> southernItaly, notably Locri and Tarentum. By stylistic comparison with stone sculptureand terracottas, bronzes have also been attributed to eastern Greece, the coastalcities <strong>of</strong> Asia Minor, although the major centers have not so far been adequatelyidentified and characterized.<strong>The</strong> subsequent movement <strong>of</strong> finished pieces destined for dedications, forgifts, or for trade, which were occasionally carried <strong>of</strong>f as plunder, is vividlydescribed by Herodotos as well. Within the present selection, the mirror (no. 11)is a good example; it was probably made in the northeastern Peloponnesos andcame to light in Cyprus. Whatever the original purpose <strong>of</strong> these objects may havebeen, they <strong>of</strong>ten ultimately became <strong>of</strong>ferings. <strong>In</strong>deed, thanks to such sanctuarysites as Olympia, Samos, Delphi, Dodona, and Perachora, the archaeologicalrecord for the Archaic period is extremely rich, providing evidence for theexpanded range <strong>of</strong>figural subjects and types <strong>of</strong> object. <strong>The</strong> female figure, forinstance, which had been rare in Geometric art, now comes into its own, <strong>of</strong>ten inconnection with utensils, such as mirrors, that one assumes were favored bywomen. Similarly, armor and weapons have come down to us in quantity and inexamples <strong>of</strong> superlative workmanship. Body armor-helmets, cuirasses, thighguards, shin guards, and ankle guards-deserves close attention, being shapedand articulated in accordance with the part <strong>of</strong> the body that it covered. <strong>In</strong> theabsence <strong>of</strong> life-size bronze sculpture, the cuirasses particularly illustrate the evolution<strong>of</strong> anatomical rendering from stylization to greater naturalism.If, indeed, the major accomplishment <strong>of</strong> Archaic bronze statuettes were to becharacterized, it might legitimately be said that the essential forms developed byGeometric artists now acquired flesh and blood. <strong>The</strong> warrior (no. 1) impresses usby the clarity and economy with which he conveys the ideas <strong>of</strong> being a man andwielding a weapon. <strong>The</strong> youth (no. 13) invites us to admire the modeling <strong>of</strong> hisbody, the detail <strong>of</strong> his long hair, his lifelikeness. This development is as evident insubjects <strong>of</strong> the imagination, like griffins (no. 9) and gorgon heads (no. 19), as inthose that the artists saw around them. When Herodotos was writing, bronzeobjects <strong>of</strong> the Geometric period were still visible. Thus, in his descriptions <strong>of</strong> theenormous Laconian bowl with decoration around the rim, or <strong>of</strong> the Samiankrater with griffins and kneeling figures, his sense <strong>of</strong> wonder may have beendirected not only at the size <strong>of</strong> the respective dedications but also at the vividness<strong>of</strong> the subjects represented.8

<strong>The</strong> ramifications <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Greek</strong> victory over Persia and the resulting preeminence<strong>of</strong> Athens extended to art, leaving their mark even in the domain <strong>of</strong> utensilsand statuettes. During the Classic period, which spans the fifth and fourthcenturies up to the death <strong>of</strong> Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., the major achievementslay in architecture, monumental sculpture in stone, bronze, ivory andgold, as well as in wall painting. Literary texts, in the form <strong>of</strong> descriptions,accounts, decrees, and so on, give the names <strong>of</strong> masters, major and minor,together with the works attributed to them, or they pertain to specific monuments.<strong>In</strong>dividuals such as the architect Iktinos, the sculptor Pheidias, and thepainter Polygnotos <strong>of</strong>Thasos set the standards for and introduced the innovationsinto their respective arts; therefore, considerations <strong>of</strong> models and influencesnow enter into the study <strong>of</strong> a work in a way that they had not previously.Bronze sculpture on a scale <strong>of</strong> halflife-size or greater can be traced back to agroup <strong>of</strong> figures <strong>of</strong> the mid-seventh century B.c. from Dreros on Crete, or to awinged figure <strong>of</strong> the first half <strong>of</strong> the sixth century from Olympia. <strong>The</strong>se workswere hammered rather than cast, and they must have been exceptionalglorifiedexperiments, so to speak-even allowing for a very poor rate <strong>of</strong> survival.At the end <strong>of</strong> the sixth century B.C., production <strong>of</strong> monumental cast-bronze statuarybegan to gain momentum. Our knowledge <strong>of</strong> it derives mainly from ancientliterary evidence, which, together with Roman marble copies, is also our chiefsource for that <strong>of</strong> subsequent centuries. To suggest the amount <strong>of</strong> materialost toDetail <strong>of</strong> an Attic red-figured cup depictinga foundry, about 490 to 480 B.C.Attributed to the Foundry Painter.Antikenmuseum, Berlin, 22949

Detail <strong>of</strong> a mirror (no. 22)us, it has been calculated that in the second century A.D. over one thousandbronze statues <strong>of</strong> victorious athletes were still standing in Olympia alone. <strong>The</strong>celebrated charioteer <strong>of</strong> Delphi, probably set up in 477 B.c., exemplifies how veryfine examples <strong>of</strong> victor dedications looked. <strong>The</strong> equally familiar statue <strong>of</strong> Zeus,found in the sea <strong>of</strong>f Cape <strong>Art</strong>emision and now in Athens, was made closer to themid-fifth century and conveys the impressiveness <strong>of</strong> large-scale images <strong>of</strong> godsthat stood in temples and sanctuaries.It is against such developments that small-scale bronzes from the fifth centuryB.C. on must be considered. If we look at the Archaic woman (no. 10) or theHerakles (no. 14) and question whether anything in them requires a large-scaleprototype, the answer is likely to be negative, primarily because <strong>of</strong> the perfectcorrespondence between the intention <strong>of</strong> the piece and its realization. By con-trast, the early Classic diskos thrower (no. 21) presents an understanding <strong>of</strong> thewhole human figure, <strong>of</strong> the interrelation between mind and body, that is morelikely to have been achieved on a scale approaching life-size than in that <strong>of</strong> a statuette.Ancient sources tell, for instance, <strong>of</strong> Pythagoras, a sculptor <strong>of</strong> bronze whowas active during the second quarter <strong>of</strong> the fifth century and specialized in athletes.Works such as his would have inspired others in a variety <strong>of</strong> sizes, materials,degrees <strong>of</strong> similarity, and levels <strong>of</strong> quality. Bronze statuettes from the Classicperiod are in no respect inferior to their predecessors. Many are simply some-what different, in that the questions <strong>of</strong> to what degree and in what way a piece isderivative play a more important part in evaluating style and iconography.Expressed in different terms, one may say that in the evolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> sculpturesmall bronzes became reflections rather than milestones <strong>of</strong> innovation.<strong>The</strong> corollary <strong>of</strong> this situation, however, is that a great many works <strong>of</strong>fer a distillate<strong>of</strong> the finest qualities <strong>of</strong> Classic art in the compact, intimate form <strong>of</strong> a statuette.Supporting the reflecting surface <strong>of</strong> the mirror (no. 22) is a woman whostands quietly but has the potential <strong>of</strong> immediate action, as indicated by the position<strong>of</strong> her head, arms, and feet. Perfectly balanced also is the articulation <strong>of</strong> herbody and <strong>of</strong> the drapery, each distinct yet both integrated to convey the grace <strong>of</strong>the figure. One could imagine that she represented an aesthetic ideal to whichusers <strong>of</strong> the mirror might well aspire.<strong>The</strong> fusion <strong>of</strong> form, function, and execution into a whole in which no oneaspect predominates is an achievement <strong>of</strong> the Classic period that, indeed, is basicto the meaning <strong>of</strong> the word "classical." During the last phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> art, knownas Hellenistic, new elements entered into the vocabulary <strong>of</strong> artistic expressionthat were <strong>of</strong>ten at considerable odds with the standard <strong>of</strong> Classic equilibrium butthat significantly widened the existing range <strong>of</strong> styles and subject matter.A consideration <strong>of</strong> the major historical and artistic developments <strong>of</strong> this timeshows that Greece lost her traditional center, not to say centers. For centuries, theheartland had existed in an area that might be circumscribed by a circle includingDodona in the north and Sparta in the south. <strong>The</strong> first major change took placeduring the fourth century B.C. when Philip II and Alexander the Great subjugatedthe rest <strong>of</strong> Greece to Macedonian rule. After Alexander's death, during theHellenistic period proper, although the old cities and sanctuaries remained inexistence, the shift continued eastward and southward to the three powerful newkingdoms, those <strong>of</strong> the Attalids in Pergamon, the Seleucids in Syria, and thePtolemies in Egypt. <strong>The</strong> traditional heartland gave way to an ever-wideningperiphery, much like the circles that spread from a pebble thrown into still water.<strong>The</strong> ramifications <strong>of</strong> these developments also altered a world that had previouslyconsisted <strong>of</strong> many states, with Athens <strong>of</strong>ten predominant but not in control. <strong>The</strong>establishment <strong>of</strong> Macedonian supremacy brought unprecedented political sub-10

ordination and centralization, not only throughout Greece as a whole but alsowithin the individual states.<strong>In</strong> art, where the Classic period had attained a balance <strong>of</strong> every constituent element<strong>of</strong> a work-whether building, statue, or water jar-the Hellenistic ageintroduced the tendency to select and develop a specific feature or detail beyondall others; observation was now pushed toward acute realism, even as far as caricature.This development gained further impetus from the new subjects thatentered the iconographical repertoire as a result <strong>of</strong> the displacement <strong>of</strong> artisticcenters to the east, notably to Pergamon and other cities <strong>of</strong> Asia Minor, Alexandria,Rhodes, and Kos. Africans (see no. 35) and orientals occurred more frequentlythan they had previously. Subjects drawn from daily life, which beforewere exceptional, became common: men and women with all the marks <strong>of</strong> age,young children, artisans, actors, dwarfs, cripples. <strong>The</strong> changes in <strong>Greek</strong> art at thistime were fundamental, yet the old traditions did not die out. <strong>The</strong> interplaybetween the classical, on the one hand, and contemporary innovation, on theother, represents an ever-present factor in the consideration <strong>of</strong> works <strong>of</strong> theHellenistic period.<strong>The</strong> range <strong>of</strong>iconographic and stylistic possibilities is suggested by a com-parison <strong>of</strong> the dancing youth (no. 31) with the artisan (no. 41). <strong>The</strong> former givesthe sense <strong>of</strong> a Classic creation infused with energy rather than serene repose. <strong>The</strong>manifest beauty <strong>of</strong> the figure and <strong>of</strong> the articulation <strong>of</strong> his body depends uponthe past. <strong>The</strong> complexity <strong>of</strong> his movement, which is the real subject <strong>of</strong> the work,makes this a product <strong>of</strong> a new age. Where the youth might have stepped out <strong>of</strong> apoem by Keats, one could have met the artisan in any industrial quarter in anycity <strong>of</strong> the ancient <strong>Greek</strong> world. <strong>The</strong>re is no attempt at idealizing the compact,work-hardened body, its muscles and skin now grown less taut. At the same time,every sensitivity remains in the weary, pensive, dignified face.As significant as the differences between these two works may be, the figuresshare a quality <strong>of</strong> overriding importance, a vigor that imparts life as much to themundane man as to the arcadian youth. <strong>The</strong> same quality is perceptible in theDionysiac masks (nos. 38-40), which are datable to the first century A.D. andwhich, for our purposes, may demonstrate the continuity <strong>of</strong> the most time-honored<strong>Greek</strong> subjects into Roman art.<strong>The</strong>se works, however, represent only part <strong>of</strong> a complex and varied artistic situation.<strong>The</strong> Hermes (no. 43) shows something quite different, an image <strong>of</strong> thefinest craftsmanship utterly devoid <strong>of</strong> inner conviction. <strong>The</strong> standard <strong>of</strong> executionand the heritage <strong>of</strong> which it is a product are immediately recognizable, yetequally apparent is an emptiness conveyed by more than just the disproportionatelysmall head, the unfocused glance, and the s<strong>of</strong>t body in a passive pose.<strong>The</strong> intention <strong>of</strong> the representation here is no longer clear or definite; onlythe form remains. <strong>The</strong> horse (no. 42) <strong>of</strong>fers another example <strong>of</strong> the samephenomenon.<strong>Greek</strong> mythology provides a noteworthy parallel to these two small sculpturesin the figure <strong>of</strong> Talos, the giant <strong>of</strong> bronze. He is best described by ApolloniusRhodius, a <strong>Greek</strong> writer <strong>of</strong> the third century B.c.He was <strong>of</strong> the stock <strong>of</strong> bronze, <strong>of</strong> the men sprung from ash trees, the last leftamong the sons <strong>of</strong> the gods; and the son <strong>of</strong> Kronos gave him to Europa to be thewarder <strong>of</strong> Crete and to stride round the island thrice a day with his feet <strong>of</strong> bronze.Now in all the rest <strong>of</strong> his body and limbs he was fashioned <strong>of</strong> bronze and invulnerable;but beneath the sinew <strong>of</strong> his ankle was a blood-red vein; and this, withits issues <strong>of</strong> life and death, was covered by a thin skin (Argonautica 4. 1639-1648).Young African, detail <strong>of</strong>no. 35His death was brought about by the sorceress Medea. According to the prin-11

cipal version <strong>of</strong> the legend, Talos's one vein, that ran from his neck to his ankle,was plugged at the ankle by a bronze nail. Medea drew out the nail, causing hislife-blood (ichor) to pour forth and his body to collapse. <strong>The</strong> episode is depictedon a vase made in Athens about 400 B.C., showing the giant keeling backward intothe arms <strong>of</strong>Kastor and Polydeukes while Medea looks on at the left. <strong>The</strong> quality<strong>of</strong> the statuette <strong>of</strong> Hermes, <strong>of</strong>ten characterized as "academic," is that <strong>of</strong> a figurewho has lost his ichor.Within this brief conspectus <strong>of</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> bronze working, themyth <strong>of</strong> Talos proves instructive in several respects. Beside contributing to ourunderstanding <strong>of</strong> certain objects that mark the transition from Hellenistic toRoman art, it is a forceful reminder <strong>of</strong> the readiness <strong>of</strong> the ancient <strong>Greek</strong>s toendow works <strong>of</strong> art with the qualities <strong>of</strong> animate beings. <strong>The</strong> concept recurs inDetail <strong>of</strong> an Attic red-figured volute-kratershowing the death <strong>of</strong> Talos, about 400 B.C.Attributed to the Talos Painter. Ruvo, JattaCollection, 1501many stories-those <strong>of</strong> Pandora, <strong>of</strong> Pygmalion, and <strong>of</strong> the bull made by Daidalosfor Pasiphae, to name a very few. <strong>In</strong> the hands <strong>of</strong> an inspired craftsman, theproper combination <strong>of</strong> imitation and imagination could result in a creation <strong>of</strong>extraordinary potential. <strong>The</strong> Talos myth reminds us also that these creations werealways made to serve a purpose-in the case <strong>of</strong>the giant, to guard the island <strong>of</strong>Crete. <strong>The</strong> myth also relates in an interesting way to the production <strong>of</strong> bronzeobjects. One's attention is drawn to the mention <strong>of</strong> a single vein running throughTalos's body and plugged at the ankle, a detail that may possibly have been takenfrom the molds for casting by the lost-wax technique.<strong>The</strong> objects in this Bulletin were produced by casting, hammering, or a combination<strong>of</strong> both. Casting was used for all <strong>of</strong> the freestanding statuettes, for thehandles <strong>of</strong> the vessels, the disks <strong>of</strong> the mirrors, and adjuncts like those decoratingthe periphery <strong>of</strong> the disk on no. 22. While a number <strong>of</strong> refinements existed,the basic process was a simple one.12

<strong>The</strong> first step was to prepare a core in a malleable matenal, like a mixture <strong>of</strong>soil and clay, that would serve as a support over which the figure would be modeledin wax. Around this wax figure was applied very fine clay, into which thedetails <strong>of</strong> the figure became impressed. <strong>The</strong> layer <strong>of</strong> fine clay, backed with coarserclay, constituted the actual mold; its relation to the figure was like a tight glove toa hand. It surrounded the figure entirely except at two points on the underside <strong>of</strong>the feet or base, where the wax was left exposed. This initial operation resultedin a three-layer construction, with the core in the center, the wax representationaround it, and the clay mold over the wax. Metal pins called chaplets, driven atintervals through the three layers, kept them aligned. When the outer clay moldhad dried, it was fired, which also caused the wax to melt and run out throughthe two openings. Molten bronze was then poured into the void left by the wax.After the bronze had cooled, the clay was removed to reveal a figure <strong>of</strong> bronzewhere originally there had been one <strong>of</strong> wax. With respect to Talos, it must be saidthat, in reality, such a large statue would have been assembled out <strong>of</strong> separatelycast pieces. Nonetheless, the idea <strong>of</strong> one vein within the otherwise solid bodymay have been suggested by the channel through which the bronze was pouredinto the mold.<strong>The</strong> figure emerging from the mold would have had a rough surface, and perhapsalso imperfections where the liquid metal had not filled the mold completely.Such casting flaws were repaired and the surface smoothed and polished.Details like locks <strong>of</strong> hair, eyelids, or borders <strong>of</strong> a garment that did not appearcrisp were reworked. Other embellishments-like the triple dots on the garment<strong>of</strong> no. 15, the scales on the griffin head (no. 9), the silver inlays on the foreheads<strong>of</strong> nos. 38 and 39, or the inscriptions on nos. 15 and 23-were added at this stageas well. <strong>The</strong> natural appearance <strong>of</strong> the bronze would have been copper coloredand rather shiny, with inlays or other additions prominent; as ancient textsindicate, the surface could be treated to modify the color or sheen. Ancientbronzes that have survived untouched show a patina consisting <strong>of</strong> layers <strong>of</strong>mineral corrosion products formed by the interaction <strong>of</strong> the metal with theenvironment in which it was buried. <strong>The</strong> tonality <strong>of</strong> this mineral accretion <strong>of</strong>tencontributes significantly to our perception <strong>of</strong> the beauty <strong>of</strong> an object, although itis foreign to the bronze's original state.Objects that were not made by casting were hammered, or raised, from a disk<strong>of</strong> sheet bronze. This process was standard for the bodies <strong>of</strong> vessels and forarmor. As metal tends to lose its resilience in the course <strong>of</strong> being worked, it mustbe repeatedly annealed, or heated to a red-hot temperature, in order to regain itsmalleability. Annealing results in relatively thin metal that, in the course <strong>of</strong> time,tends to survive less well than the more solid cast pieces. Thus the cast handles <strong>of</strong>water jars, jugs, lavers, and other utensils exist in greater number than the hammeredparts to which they were soldered or riveted.Although every technique had its refinements-casting could be done in openmolds, with the lost-wax or sand-core process-and although innovations, suchas the lathe, were introduced, the fundamental technology <strong>of</strong> bronze workingwas already known to Geometric artists and was fully mastered by their Archaicsuccessors. <strong>The</strong> continuity afforded by these consistent, long-lived methods addssignificantly to the picture <strong>of</strong> cohesiveness and progressive evolution presentedby the almost thousand-year history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> bronzes. <strong>The</strong> forms, subjects, purposes,and techniques were quite limited, but the ever-new creations <strong>of</strong> the artistsseem very nearly infinite, thanks to their gifts <strong>of</strong> observation and imagination.13

1. Nude warrior, second half <strong>of</strong> theeighth century B.C.<strong>The</strong> nude male figure stands on a smallrectangular base, with which it hasbeen cast. While his legs are set slightlyaskew, his wide, flat chest is parallelto the viewer. His massive but subtlyarticulated neck ends in a small head,which is tilted back. Protuberancesindicate the ears and nose; twoscarcely visible forms in relief mark theeyes. <strong>In</strong> his raised right hand he wouldundoubtedly have held a spear; theobject originally in his left hand cannotbe determined. Two dowels fasten thewarrior to a thinner sheet <strong>of</strong> bronze,indicating that he originally decorateda vessel. It was almost certainly a tripodcauldron, a deep bowl, in this casemade <strong>of</strong> hammered sheet bronze, supportedon three legs and providedwith two large ring handles that rosevertically above the mouth. <strong>The</strong> warriorwould have stood beside one <strong>of</strong>the handles.Although it is difficult to localize theworkshop where the figure was made,one possibility is that it was in Elis, theregion in which Olympia is located.<strong>The</strong> statuette is wonderfully direct inconveying the essential features <strong>of</strong> theman's body and <strong>of</strong> his action. <strong>The</strong>small dislocations in the pose contributeto his lack <strong>of</strong> rigidity. <strong>In</strong>deed, hisproportions, with long legs and a compacthead and neck, his stance, and theposition <strong>of</strong> his arms make the warriora lineal ancestor <strong>of</strong> the diskos thrower(no. 21).Said to come from Olympia or Crete.H. 713/16 in. (19.6 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1936(36.11.8)

2. Man seated on a ball, last quarter<strong>of</strong> the eighth century B.C.This object consists <strong>of</strong> a bearded manseated atop a hollow ball. <strong>The</strong> latter,pierced with eight vertical slashes, surmountsa short cylindrical stem endingin a flat, round foot. Attached to thetop <strong>of</strong> the ball is another cylinder thatsupports a "bench'" which has a holeat either end. A thong presumablypassed through the holes. <strong>The</strong> man sitssquarely on the "bench," resting hishands on his knees and his feet on theshoulder <strong>of</strong> the ball. <strong>In</strong>cised on theman's back is a circle made with thesame tool used for the eyes, an "X" thatruns to each shoulder and, below that,a series <strong>of</strong> horizontals; since the front<strong>of</strong> the body is entirely plain, the incisionsmay be purely decorative or theymay represent equipment, such as abelt, two crossed baldrics, and a shield.Given its assemblage <strong>of</strong> elementsand its style, this work could only haveGreece.come from <strong>The</strong>ssaly, in northernOnly six examples <strong>of</strong> the specifictype are known, yet pendantscomposed <strong>of</strong> spheres elaborated in agreat variety <strong>of</strong> ways are characteristically<strong>The</strong>ssalian; so also is the use <strong>of</strong> aseated figure as a finial and the wirybuild. Our principal evidence forestablishing the purpose <strong>of</strong> the piececonsists <strong>of</strong> the holes for suspensionand the fact that many such pendantswere ultimately <strong>of</strong>fered as dedications.Here, as in the bird (no. 6), provision ismade for both standing and hanging. Adefinitive solution to the question <strong>of</strong>function must await more information.What the work itself shows, however, isan extraordinary sense <strong>of</strong>three-dimensionality,expressed not only by thetreatment <strong>of</strong> the forms but also by thejuxtaposition <strong>of</strong> mass and void.H. 33/4 in. (9.5 cm). Ex colls. Tyszkiewicz,Pozzi, Simkhovitch. Edith Perry ChapmanFund, 1947 (47.11.7)

3-6. Two horses, a ram, and a bird,second half <strong>of</strong> the eighth centuryB.C.<strong>In</strong> Geometric art animals far outnumberhuman figures, with birds,horses, sheep, bulls, and other quadrupedsbeing particularly common.<strong>The</strong> ring with a ram illustrates an animalserving as a decorative adjunct.<strong>The</strong> exact function <strong>of</strong> the object isunclear, but the possibilities include itshaving been the ring handle <strong>of</strong> a smalltripod, part <strong>of</strong> a harness, or a pendant,like no. 2, that could either be hung or,in this case, be let into a base. <strong>The</strong> ram,decorated with circles, is remarkablefor its flatness, which is mitigated onlyby the curved horns. <strong>The</strong> three otheranimals introduce a feature that ismore important in Geometric art thanat any later time. <strong>The</strong>y have bases withelaborate patternwork whose purpose,beyond that <strong>of</strong> decoration, is not clear;the theory that these objects couldbe used as stamp seals to identifyownership is appealing. Aesthetically,the bases significantly influence thethree-dimensional effect <strong>of</strong> the pieces;although both horses are comparablylean and sparse in their articulation,the rectangle below one accentuates itslength and angularity, while the diskunder the other defines a circularspace and emphasizes volume. <strong>The</strong>bird is especially successful, with thefullness <strong>of</strong> its body enhanced by theround base and the thin subdivisionswithin the base repeated in the crestand tail. <strong>The</strong> centers <strong>of</strong> productionrepresented by these four works covermuch <strong>of</strong> Greece. <strong>The</strong> bird was probablymade in the Argolid and the horseon the rectangular base in Corinth.Despite the presence <strong>of</strong> Corinthian fea-tures, the horse on the disk has beenattributed to Locris in central Greece,while the ram may well come fromthe north.Horse (left): H. 33/8 in. (8.4 cm). Gift <strong>of</strong>H.L. Bache Foundation, 1969 (69.61.4).Horse (center): H. 37/16 in. (8.8 cm).Bequest <strong>of</strong> Walter C. Baker, 1971(1972.118.49). Ram on ring: H. 33/4 in.(9.5 cm). Gift <strong>of</strong> Mr. and Mrs. HenriSeyrig, 1954 (54.137.2). Bird: Said to befrom the Argive Heraion. H. 315/6 in.(9.9 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1935 (35.11.14)17

f_1 &ll iI -_FWgrounds, it can be assigned to a Lacoa_!i ,'^ ^*,j 'nian workshop. <strong>The</strong> group is made up:l'& ~' -'i.. . .<strong>of</strong> a man, wearing a belt and a conical_BI_, .L iB~ i.; i i ,- *icap, .standing before a centaur, who is a-r ' 'L_Jsmaller version <strong>of</strong> his counterpart--_'H^^^^ - r . , : , even to the cap-with the addition <strong>of</strong>*,I-^^^; '. I the body and hindquarters <strong>of</strong> a horse.-_:H * i \ H * 1 ; ; * <strong>The</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> their relation to eachother is indicated by the spearhead_l _; ,,? | !projecting from the centaur's left side,- H ~_; i, 1 q,, his firm grasp <strong>of</strong> the man's right fore-' 1 ;....cE iJ,^t a_ _ !?taur'srih right arm, which w is now missingL^'l _j~.!!.~I S' *";i~ *~ ,1,,^*abovethe elbow but which probably.. . L i'~, would have brandished a branch.<strong>The</strong> base contributes significantly tothe composition <strong>of</strong> the'h ' piece by joinen"I'"~ing the figures on a common ground1 _ and dition: emphasizing te the centaur through~itsI 111 irregular 1 shape; it even suggestsI;II I I ~11 _Srough terrain through the cutouts. <strong>The</strong>effect and complexity <strong>of</strong> the impliedspace would have been still greaterwhen the work was in its original condition:the spear in the man's right-4~:~. i:::;i,i:; :..7. Man and centaur, mid-eighthcentury B.C.Figural groups, occasionally with animplied narrative context, are rareamong Geometric statuettes and ~. .become even rarer after the Geometricperiod. Of these groups, which include ...a lion hunt, a ring dance, and menwith animals, this one is unrivaled inits clarity and intensity. On stylistic18

hand and a weapon <strong>of</strong> some kindabove the centaur's head would haveadded width and height. Within thecomposition that even now is verytight and closed, there is virtually noincidental detail to divert us from theconfrontation <strong>of</strong> the two antagonists.<strong>The</strong> spearhead in the centaur's flankinforms us <strong>of</strong> the outcome, yet one isinclined to attribute his opponent'ssuperiority not only to the spear butalso to the glance <strong>of</strong> the man's deeplyhollowed eyes. Scholars have proposeda variety <strong>of</strong> specific identifica-tions, such as Zeus and one <strong>of</strong> theTitans or Herakles and one <strong>of</strong> the centaurs,perhaps Pholos. Beyond speculation,however, are the timelessness anduniversality <strong>of</strong> the motionless confrontationbetween the warrior and hissemihuman adversary.Said to be from Olympia. H. 45A6 in.(11.1 cm). Gift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 191717.190.2072)8. Armorer working on a helmet,end <strong>of</strong> eighth to early seventhcentury B.C.<strong>The</strong> statuette <strong>of</strong> an armorer is quintessentiallyGeometric in its sparsenessand in the generally rectangular formatwithin which it is composed; at thesame time, it shows an unprecedentedlimberness. <strong>The</strong> craftsman is beardedbut otherwise nude, unless the caplikeform on his head represents not hairbut a skullcap <strong>of</strong>ten worn by ancientartisans. He sits on the ground with hisright foot against the base <strong>of</strong> a shaft,probably a stake, supporting thehelmet. With his left hand he holds thehelmet by a cheekpiece; in his righthand he held a tool, perhaps a mallet,<strong>of</strong> which only the handle remains. <strong>The</strong>helmet is Corinthian in type, like no.18, with a nose guard and a tall crest, <strong>of</strong>which the crest holder is preserved.Because the helmet appears fullyformed and the craftsman has no toolin his left hand, he is probably hammeringit into its final shape. A fewcontemporary statuettes <strong>of</strong> genresubjects survive; among them are acharioteer and an archer both found atOlympia. While all three figures arerendered with a keen sense <strong>of</strong> observation,the armorer is significantly different:he sits directly on the ground,without a base. A freestanding work,such as this one, must rely on its compositionand execution to ensure balance.<strong>In</strong>deed, during the whole history<strong>of</strong> <strong>Greek</strong> bronze statuettes, freestand-ing examples without a base <strong>of</strong> theirown or provision for being let into asupport are exceptional.H. 2 in. (5.1 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1942(42.11.42)19

-v. . k,L V:l 5 Cr-cIr2?,pCra r ea rl%i-Y? .c: I,- '1. ??..?'hr??.?? Et;.,cP PN I-'?jLLB `1\'JI?;?mYR?'Cjll ?il-*??rJYlc'-'I lurr r I -pT 'C-CSl(m .`. -?Tl??.\i- it;..,.J--%t: c; ..':'?i :1 ?? :Y ..:hrLi, i?c.-. p.r Cki c r=,? ?? c?4-I?u?rt. Irc Y ? rii??I? \. rd.- I. n ??II.?i?. ". 4 c;r 21 I ? :? rr.r?'`h;'rC:?l .'^ r ??`L?,!`, .LFPr? 4'???:: I?- C Y r '1 ??. r.. ?:. ?' ??,.,.? 4i3Vl`iI'1.rr I.*? ,?IC*)

9. Head <strong>of</strong> a griffin, third quarter <strong>of</strong>the seventh century B.C.During the second half <strong>of</strong>the eighthcentury, protomes <strong>of</strong> griffins, or morerarely lions, began to appear attachedaround the shoulder <strong>of</strong> a new type <strong>of</strong>tripod cauldron that was replacingthose with figures at the handles (seeno. 1). <strong>The</strong> function <strong>of</strong> the protomeswas decorative and symbolic ins<strong>of</strong>ar asthese creatures inspired respect inthose who saw them. <strong>The</strong>y did notserve any purpose related to the carrying<strong>of</strong> the cauldrons; for that, someexamples had small ring handlesfastened to the shoulder. Griffincauldrons achieved great favor in theseventh century, as has been documentedby over six hundred survivingprotomes as well as by Herodotos'smention <strong>of</strong> the Samian dedication(p. 7). Significantly, most <strong>of</strong> the preservedpieces were discovered inSamos and Olympia. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>'sgriffin head can be connected with thelatter site and a Peloponnesian, possiblyCorinthian, workshop. While thehead is cast, a neck hammered fromsheet bronze once formed the transitionto the cauldron; considering theweight <strong>of</strong> the head, it is not surprisingthat the neck no longer exists in thiscase, nor in virtually all <strong>of</strong> the otherscombining cast and hammeredelements.<strong>The</strong> griffin, a winged lion with thehead <strong>of</strong> a bird <strong>of</strong> prey and ears <strong>of</strong> ahorse, was introduced to Greece duringthe eighth century along with agreat number <strong>of</strong> other iconographicaland technical innovations from theEast. <strong>The</strong> griffin protome, however,was a purely <strong>Greek</strong> creation, and the<strong>Museum</strong>'s example is one <strong>of</strong> the veryfinest. <strong>The</strong> integration <strong>of</strong> compositionand execution is here complete. <strong>The</strong>play <strong>of</strong> curves between tongue andbeak is tangibly emphasized by theslight relief line around the mouth.Similarly, the shape <strong>of</strong> the great archingeye, which was probably once inlaid,reechoes in the three folds <strong>of</strong> the "eyelid."One can well understand whyHerodotos was impressed by a hugebowl ringed with heads such as these.From Olympia. H. 10Y in. (25.8 cm).Bequest <strong>of</strong> Walter C. Baker, 1971(1972.118.54)10. Standing woman wearing apeplos, second quarter <strong>of</strong> the sixthcentury B.C.This bronze brings us into the Archaicperiod; it carries over from Geometricart a clear sense <strong>of</strong> structure whileintroducing a new concern for renderingthe volumes <strong>of</strong> the body and differentiating them through garments.<strong>The</strong> figure wears a peplos, a longstraight tunic; a belt at the waist; and anepiblema, a kind <strong>of</strong> bolero that was fastenedat each shoulder. Her hair isbound with a fillet, or band, and restingon top <strong>of</strong> her head is a flat diskwith traces <strong>of</strong> an iron pin in the center,which indicates that the woman supportedsome kind <strong>of</strong> utensil, perhapsan incense burner. <strong>The</strong> figure standsstiffly, but her large eyes, full cheeks,the mass <strong>of</strong> hair-differentiated bothabove and below the fillet-and thecontrast <strong>of</strong> the volume <strong>of</strong> her chest toher narrow waist contribute considerables<strong>of</strong>tness and grace. <strong>The</strong> skirt,feet, and hands appear less preciselyworked than the face and upper body;in fact, technical examination revealsthat the two parts are the products <strong>of</strong>two different castings. <strong>The</strong> figure mayhave been damaged during the originalcasting, making the replacement nec-essary at the outset, or it may have brokenlater and a replacement was caston to salvage it. <strong>The</strong> workshop thatproduced the piece has been identifiedas Peloponnesian, possibly Laconian.While evidence drawn fromdifferent media and regions must beused with care, parallels for the dress<strong>of</strong> the figure, the pinning <strong>of</strong> the epiblemaon the shoulders, and the character <strong>of</strong>the articulation occur in Attic vasepainting and sculpture <strong>of</strong> about 570 to560 B.C.; thus a date in the secondquarter <strong>of</strong> the century seems justified.H. 71616 in. (19.5 cm). Ex coll. Simkhovitch.Bequest <strong>of</strong>Walter C. Baker, 1971(1972.118.57)

! r ," 4kL'5.^ ** >* i?.'' ^ "* -?..'* * * "-'. Y ,.. *^ :

11, 12. Nude girl and a mirror with asupport in the form <strong>of</strong> anude girl, second half <strong>of</strong> thesixth century B.C.<strong>In</strong> Archaic art the utensil that most<strong>of</strong>ten included a female figure as a supportwas the so-called caryatid mirror.<strong>The</strong> two examples presented herewere made in Laconia ten to twentyyears apart; no. 11 can be dated about540 to 530 B.C. and no. 12 about 520 B.C.<strong>In</strong> each case the girl is nude except fora necklace with a pendant in the centerand a band, from which hang acrescent-shaped amulet and a ring.<strong>The</strong> earlier figure (no. 11) has twomore amulets hanging on the left side<strong>of</strong> her back. She also wears a netlikesnood that leaves only the edge <strong>of</strong> herhair exposed, while her counterpart(no. 12) has a flower on either side <strong>of</strong>her head just above her ears. <strong>The</strong> earlierfigure holds cymbals, and theother grasps a pomegranate by thestalk with her left hand; the objectoriginally in her right hand can nolonger be identified. <strong>The</strong> stance <strong>of</strong> thegirls differs significantly, as does whatthey stand on. <strong>The</strong> support <strong>of</strong> the earlierone consists <strong>of</strong> a folding stool withequine legs, on which crouches a largefrog that appears to grip the front andsides with its feet. <strong>The</strong> girl stands onthe frog's back, with her left footadvanced slightly before her right. Herupper body turns toward her right,creating the same effect <strong>of</strong> ease shownto a more limited degree by the warrior(no. 1). <strong>The</strong> feline feet attached toher elbows and shoulders are remains<strong>of</strong> creatures-perhaps griffins-thatsupported the disk, as they do on themirror at the right. Here, the figure

Istands on a lion, which is curled upand rests its head between its paws.<strong>The</strong> disk, steadied by the well-preservedgriffins, is let into an openingon the top <strong>of</strong> the figure's head.Although the pose <strong>of</strong> this slightly latergirl lacks the torsion <strong>of</strong> her counterpartand may seem stiffer, the parts <strong>of</strong>her body are better integrated and proportioned;in every respect she seemsmore composed.<strong>The</strong> function <strong>of</strong> a mirror evokesAphrodite, the goddess <strong>of</strong> beauty andlove, whose origins are ultimately NearEastern. Because they are nude andcarry amulets and cymbals, these figuresare closer to Aphrodite's orientalaspect, in which she is connected withfertility, than to her Archaic <strong>Greek</strong>form, in which, <strong>of</strong>ten elaboratelyclothed, she appears in mythologicalscenes, such as the Judgment <strong>of</strong> Paris,or in depictions <strong>of</strong> the life <strong>of</strong>women.<strong>The</strong> frog and pomegranate are attributesassociated with procreation,while the lion accompanies other easterngoddesses, like Cybele. It is impossibleto identify the caryatid figuresexactly; they may be attendants <strong>of</strong>Aphrodite or women embodying cer-tain <strong>of</strong> her qualities.Girl: Said to be from Kourion. H. 85/8 in.(21.9 cm). <strong>The</strong> Cesnola Collection,Purchased by subscription, 1874-76(74.51.5680). Mirror: Said to be fromsouthern Italy. H. 135/8 in. (33.8 cm).Fletcher Fund, 1938 (38.11.3)

13. Nude youth, third quarter <strong>of</strong> thesixth century B.C.<strong>The</strong> Archaic male figure par excellenceis the nude youth standing at rest, oneleg before the other, his arms usually athis sides, without attribute or gestureto introduce any specific or episodicfeature. <strong>The</strong> sculptural form, bestexemplified in marble, is <strong>of</strong>ten calleda "kouros," the <strong>Greek</strong> word for a"youth." This statuette, despite theposition <strong>of</strong> his arms and the objectin his right hand, is as direct a representation<strong>of</strong> a beautiful youth as anykouros. His body is long and slim, withdeveloped musculature in the chestand shoulders. <strong>The</strong> even modeling isboth complemented and emphasizedby the mass <strong>of</strong> hair, articulated intoshort tight locks on the top <strong>of</strong> his headand falling in longer, looser tressesalmost to the small <strong>of</strong> his back. Whilethe figure seems to direct his attentiontoward something in front <strong>of</strong> him, thesituation is impossible to determine;so is the object he holds, which looksmost like the stalk <strong>of</strong> a plant, perhaps apoppy. <strong>The</strong> rendering <strong>of</strong> the body suggestsa date almost contemporary withthat <strong>of</strong> the caryatid supporting the mirror(no. 12). <strong>The</strong> style has been comparedwith both Peloponnesian piecesand others from eastern Greece, spe-cifically Samos. <strong>The</strong> combination isnot problematic in view <strong>of</strong> the communicationbetween Laconia andthe eastern Aegean during the Archaicperiod: ancient literary sources tell <strong>of</strong>Bathykles <strong>of</strong> Magnesia who madean elaborately decorated throne atAmyklai near Sparta; <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong>odoros <strong>of</strong>Samos who constructed a buildingnear Sparta; and <strong>of</strong> the great bronzebowl intended as a gift from Sparta toCroesus, king <strong>of</strong> Lydia (p. 7). Suchinterchange can account for the presence<strong>of</strong> a s<strong>of</strong>tness usually associatedwith East <strong>Greek</strong> sculptural styles in afigure that retains the structure andfirmness <strong>of</strong> Peloponnesian works.H. 6 in. (15.2 cm). Bequest <strong>of</strong>Walter C.Baker, 1971 (1972.118.101)I _ _25

14. Herakles, last quarter <strong>of</strong> the sixthcentury B.C.<strong>In</strong> this forceful representationHerakles is the virtual personification<strong>of</strong> controlled strength. <strong>The</strong> compactbody shows a thorough integration <strong>of</strong>bony structure and musculature. <strong>The</strong>outstretched arm with its clenched fist,the formidable right arm with the clubthat is almost half as tall as the figure,the right foot modeled to suggest greatpower behind the forward stride -such details establish his physicalprowess. At the same time, his finebeard and particularly the impeccableprecision <strong>of</strong> his hair, bound with afillet, mark the man as civilized.Herakles can be placed among theforemost <strong>Greek</strong> heroes for the laborsand adventures that linked him with allparts <strong>of</strong> Greece, and for the fact that,ultimately, he was accepted among theimmortals on Mount Olympos. Hewas depicted with great frequency andin all media during the Archaic period.<strong>The</strong> present statuette is particularlyremarkable for the economy withwhich it expresses both strength andcivility. Its reputed find spot supplementsstylistic criteria for associating itwith bronze figures from the centralPeloponnesos, which are commonlycalled "Arcadian" when they are peasanttypes, <strong>of</strong>ten bearing animals, or"Argive" when their physical build ismuscular and compact but the level <strong>of</strong>execution superior. Although the baseupon which Herakles stands is piercedin two corers, he is not likely to havedecorated a vessel; the shape <strong>of</strong> thebase and the pronounced threedimensionality<strong>of</strong> the figure indicatethat it was probably a dedication.Said to be from Mantinea in Arkadia. H.5Y16 in. (12.8 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1928(28.77)

15. Man playing the lyre, late sixth toearly fifth century B.C.<strong>The</strong> statuette represents a beardedman wearing a long chiton, belted atthe waist and ornamented with tripledots and a guilloche pattern on itslower border. His hair is bound with afillet, which may well retain the originalgilding. <strong>The</strong> long belted garment isa special form <strong>of</strong> dress usually seen onflute and lyre players and on charioteers.<strong>The</strong> instrument, held in themusician's left arm, shows careful articulation<strong>of</strong> the strings, arms, and tortoiseshellsound box. <strong>The</strong> musicianholds the plektron in his right hand.Like the armorer (no. 8) and the"Arcadian" peasants mentioned onpage 27, the musician belongs to thetradition <strong>of</strong> subjects <strong>of</strong> daily life, whichare represented less frequently inbronzes than in vase painting. <strong>The</strong>iconographical interest <strong>of</strong>the pieceis heightened by the inscriptionengraved in Attic letters over the back<strong>of</strong> the legs and buttocks: "Dolichosdedicated me." <strong>The</strong> formula is typicalfor such <strong>of</strong>ferings <strong>of</strong> the Archaicperiod, as is the placement <strong>of</strong> the textover part <strong>of</strong> the figure's body. We donot know why this statuette was madeor dedicated. It should be noted, however,that lyre players were not onlymusicians in the restricted sense butalso poets and preservers <strong>of</strong> orallytransmitted historical knowledge.Dolichos may have made this <strong>of</strong>feringafter a victory in a contest <strong>of</strong> musical ormnemonic skills, or simply out <strong>of</strong> gratitudeto a benevolent muse.H. 3/8 in. (7.9 cm). Rogers Fund, 1908(08.28.5)28

16. Horse, second quarter <strong>of</strong> the sixthcentury B.C.Because <strong>of</strong> the greater expressive possibilitiesthat the human form <strong>of</strong>feredto Archaic artists, there are fewer animalbronzes than in the Geometricperiod; horses and lions, however,continued to be popular. This statuetteevokes its antecedents through thelong narrow base, to which even thetail is attached. <strong>The</strong> cylindrical bodyand large, generally triangular hindquartersperpetuate the earlier emphasison strong, clear forms as well. Whatis new, however, is the subtly modeledneck and chest, the elegant legs, andthe luxuriant mane, which is given asmuch attention as the hair <strong>of</strong> the youth(no. 13). It is evident that the horsewas made by an artist who had lookedat living models, even if he has left acertain awkwardness in the proportionsand composed the legs not asthey move in nature but to stressthe strength <strong>of</strong> the hindquarters. <strong>The</strong>piece was reputedly found in southernItaly, in Locri Epizephyrii ("Toward theWestern Winds"), founded by mainland<strong>Greek</strong>s from the region <strong>of</strong> Locris.It is one <strong>of</strong> the earliest bronzes associatedwith a center that later was wellknown for the production <strong>of</strong> caryatidmirrors. Chronological evidence forthe piece exists in Corinthian and Atticvases <strong>of</strong> the very end <strong>of</strong> the seventhcentury and <strong>of</strong> the first half <strong>of</strong> the sixththat show horses with the same horizontallystriated manes. Comparisonwith other bronzes from southernItaly, notably a group <strong>of</strong> a horse andrider in the British <strong>Museum</strong>, suggests adate about 570 to 560 B.C.Said to be from Locri. H. 65/8 in. (16.8 cm).Ex coll. Junius S. Morgan. Lent in 1907 byJunius Spencer Morgan (1867-1932) andgiven by his heirs in 1958-1959 (58.180.1)29

17. Two rams, third quarter <strong>of</strong> thesixth century B.C.<strong>The</strong> tradition <strong>of</strong> utilitarian objectsembellished with sculptural adjuncts,last encountered on these pages in thegriffin cauldrons (see no. 9), continuedto flourish during the sixth century B.C.<strong>The</strong>se rams were attached with bronzedowels, still preserved, to a utensil thatis difficult to identify. <strong>The</strong> underside<strong>of</strong> the animals is both hollowed andcurved, indicating that they fitted ontoa rolled or tubular surface that wasabout 2 cm in diameter. Because <strong>of</strong>their considerable weight, roughlythree pounds apiece, and because theobject may well have had more thanthe two attachments, a sturdy supportwould have been required. It may havebeen the rim <strong>of</strong> some kind <strong>of</strong> basin orstand rather than the shoulder <strong>of</strong> acauldron. <strong>The</strong> animals introduce anew stylistic mixture. <strong>The</strong>y show1976.11.21976.11.3

ather broad smooth planes, with virtuallyno detail or indication <strong>of</strong> underlyingstructure. <strong>The</strong> salient features,like the limbs, horns, eyes, andmuzzles are boldly modeled and articulatedwith highly stylized markings.<strong>The</strong> rams do not give the impressionthat they could stand up and move, oreven that this is a potential that the artistparticularly wished to convey. <strong>The</strong>approach differs perceptibly from thatin the horse (no. 16) and in the humanfigures just considered, and it points toinfluence from the Near East. Recumbentanimals with heads at right anglesto their bodies and legs folded symmetricallyunder them occur in smallobjects <strong>of</strong> gold, electrum, ivory, andlimestone found at Ephesos, Sardis,and other sites where <strong>Greek</strong>s <strong>of</strong> thesixth century came in contact withLydian, Achaemenian, and perhapseven Scythian craftsmen or theirworks. Pieces as finely executed asthese rams make clear how significantlyEastern admixtures modified<strong>Greek</strong> artistic expression.Front: L. 59/16 in. (14 cm). Back: L. 5/8 in.(14.2 cm). Purchase, Rogers Fund andNorbert Schimmel Gift, 1976 (1976.11.2,3)18. Helmet, first third <strong>of</strong> the sixth centuryB.C.Body armor occupied a special place thanamong the various categories <strong>of</strong> metalwork,for the craftsman devoted all <strong>of</strong>his technical and aesthetic talents tothe protection and appearance <strong>of</strong> aperson. <strong>The</strong> helmet illustrated here is<strong>of</strong> the "Corinthian" type, which ischaracterized by a bell-like form, longnosepiece, and cheekpieces that leavelittle but the eyes exposed. While theshape is, <strong>of</strong> course, determined by that<strong>of</strong> the human head, the graceful curveoutward at the nape <strong>of</strong> the neck andaround the lower part <strong>of</strong> the face suggeststhat the armorer exploited themalleability <strong>of</strong> the bronze for morepractical purposes. Every edge isfinished with incised lines and theupper curve <strong>of</strong> the eye is slightly thick-ened, a device seen previously on thegriffin protome (no. 9). Rising in lowrelief from the bridge <strong>of</strong> the nose aretwo snakes whose bodies double aseyebrows until they curve back intometiculously articulated heads withlarge eyes, razor-sharp teeth, and flickingtongues. <strong>In</strong>cised on the forehead<strong>of</strong> the helmet is a lotos flower with asmall palmette to either side; similarpalmettes occur above the ogee cutinto each side <strong>of</strong> the helmet. Over andabove the technical skills needed tosatisfy the protective requirements, ahelmet like this one challenged acraftsman's artistic sensitivity, producingsuch fine effects as the juxtaposition<strong>of</strong> the lotos with the nosepiece orthe snakes with the line <strong>of</strong> the eyelid.<strong>The</strong> date <strong>of</strong> the work is furnished notonly by comparison with other Corinthianhelmets but also by details likethe palmettes and lotos; the latter suggestsa date about 600 to 570 B.C.Said to be from Olympia. H. 87/8 in.(22.6 cm). Dodge Fund, 1955 (55.11.10)31

.r.~/-?tZ~ ~i~~~~~-~!~ ~,~. ...J~~~~ ~/v~~o ~....?1~"k~~~.cm~~r~Ll~//r~,i~,~ ~. f~!~ !!~ll. ~.~!!,i!!!'~~l~-~',-