The Advising Counseling Continuum: Triggers for Referral - NACADA

The Advising Counseling Continuum: Triggers for Referral - NACADA

The Advising Counseling Continuum: Triggers for Referral - NACADA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

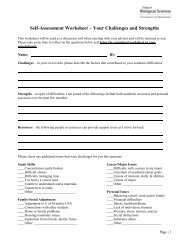

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Advising</strong> and <strong>Counseling</strong> <strong>Continuum</strong>: <strong>Triggers</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Referral</strong>Terry Kuhn, Kent State UniversityVirginia N. Gordon, <strong>The</strong> Ohio State UniversityJane Webber, Monmouth UniversityIn this article, we describe a continuum ofresponsibilities shared by faculty and nonfacultyacademic advisors as well as personal counselorsat 4-year colleges and universities. After addressingterminology, we describe a continuum of issuesthat advisors and counselors routinely address andidentify some triggers that might suggest that areferral from an advisor to a trained counselor iswarranted.KEY WORDS: advisor role, counselor, developmentaladvising, mentoring, student problemsRelative emphasis:* practice, theory, research<strong>The</strong> myriad of academic, social, and personalconcerns and problems that students may bring totheir advisors can be bewildering to new faculty orfull-time academic advisors. Experienced advisorscan attest to the “complicated and extensive personal,real-life agendas that many students bringwith them to college that often militate againststudy and learning” (Butler, 1995, p. 107).Counselors are also familiar with students who areconfronting difficult personal and transitional issues.Many students need in<strong>for</strong>mation, goals, confidence,and support to pursue rigorous academic programssuccessfully (Hobfoll, 2002; McWhirter,1997). Advisors are the institutionalized front lineof such support and assistance.In this article, we describe a continuum ofresponsibilities from the most basic in<strong>for</strong>mationoffered to students by an advisor to the more personalservices provided by counselors. Advisorsare not trained counselors, and counselors usuallydo not have extensive knowledge about curricula oracademic policies. <strong>The</strong> line where these two areascross is not always clearly defined. We suggesttriggers that will initiate referrals of troubled studentsfrom advisors to counselors.Ambiguity of Terms<strong>The</strong> terms advising and counseling are sometimesused interchangeably. <strong>The</strong> <strong>NACADA</strong> search engine(www.nacada.ksu.edu/Journal/journal_help.htm),powered by Google to find references to the words“advising and counseling,” produced articles onadult learners, academic advising and career counseling,advising and counseling of minority students,programs <strong>for</strong> counseling and advising, andcounseling and career advising among other topics.This mixture of advising and counseling termsfound on the <strong>NACADA</strong> Web site suggests a blurringof definitions. Various definitions of academicadvising can be found through Google searches <strong>for</strong>“academic advising definition,” “academic counselingdefinition,” and “counseling definition.” A listof relevant Web sites <strong>for</strong> defining academic advisingis provided at the end of this article.At one end of the advising-counseling continuum,academic advising is conceived as a collaborativeprocess in which advisors help students todevelop and realize their educational, career, andpersonal goals. At its most fundamental level, advisingis in<strong>for</strong>mational and explanatory and progressesthrough developmental and mentoring phases. Atthe other end of the continuum, counseling helpsstudents overcome personal problems from the pastand present that interfere with their academic success.Typically, students discuss with counselors theconcerns or difficulties they are experiencing, andthe counselor helps the student mobilize his or herown resources to resolve the problems. In additionto current views that counseling deals withwellness, personal growth, and career development,counseling also produces connotations ofrehabilitation, therapy, disability, or pathology—conditions that may be related to emotional, mental,or physical problems (America <strong>Counseling</strong>Association, 2002).At different institutions the terms advising,counseling, advisor, and counselor are used <strong>for</strong>different functions and persons. For instance, theresponsibilities assigned to a person with the titleof advisor at a research university might be thesame as those assigned to a person with the title ofcounselor at a community college. Even withinresearch universities, those giving academic adviceto students may have the title of academic advisorin one college while their colleagues in a differentcollege may have the title of counselor or academiccounselor.* See note on page 4.24 <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006

<strong>Advising</strong> <strong>Referral</strong> <strong>Triggers</strong>Some of the confusion in terminology may stemfrom the widespread use of the term counseling insecondary schools; it covers the gamut of responsibilitiesfrom dispensing in<strong>for</strong>mation to dealing withstudents’ emotional and behavioral problems. Bytheir very nature, advisors and counselors experienceconsiderable overlap between their responsibilities,attesting to an institutional lack of agreement aboutthe responsibilities associated with either position.For the sake of clarity, we use the terms advising andadvisor to refer to academic advising and academicadvisor. <strong>The</strong> terms counseling and counselor refer tothose who are trained in a graduate-level program toprovide personal counseling and the services theyprovide; counselors may be housed in a college or ina counseling center. <strong>The</strong> roles of advisor and counselorare more robust than the characterizations in thisarticle; nevertheless, the distinctions between advisingand counseling are made intentionally stark toemphasize their differences. This article is most pertinentto colleges and universities in which the rolesof advisor and counselor are distinct, unlike the situationsat many community colleges where bothroles may be invested in the same person with atitle of either advisor or counselor.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Advising</strong>-<strong>Counseling</strong> <strong>Continuum</strong>Having noted the widespread ambiguity, overlap,and lack of agreement in the current use of the termsadvising and counseling, we conceived a continuumof responsibilities addressed by both advisorsand counselors in varying degrees. This continuumof responsibilities is represented in Table 1 andincludes five different levels of involvement: in<strong>for</strong>mational,explanatory, developmental, mentoring,and counseling. While the table columns that illustratethe five levels of involvement may be mistakenlyperceived as silos, we realize that in manycircumstances involvement may not be characterizedneatly in categories. In practice, the levels of involvementmay overlap, and each column represents adevelopmental component that empowers adviseesto discuss themselves, their feelings, and their goals.Shane (1981) compared advising, counseling,and psychotherapy and outlined the service providersand program categories <strong>for</strong> each. Butler (1995)identified the missions and purposes of organizationalstructures and services <strong>for</strong> advising and counseling.<strong>The</strong> first version of the content in Table 1 wasdeveloped by Virginia Gordon <strong>for</strong> workshops inthe 1970s and has been revised to reflect the contentof this article. Table 1 may be considered afurther development of those earlier ef<strong>for</strong>ts.<strong>The</strong> purpose, content, and focus of academicadvising contacts range from students’simple questionsto more complex academic, social, or personalproblems. All advisors tend to be involved in thein<strong>for</strong>mational, explanatory, and developmental-advisingresponsibilities (Table 1), but faculty advisors aremore likely to assume the role of mentor with graduatestudents or undergraduates in liberal arts institutions.<strong>The</strong> questions or concerns that studentspresent in the advising contact determine the involvementof the advisor, and some contacts may engagethe advisor at multiple levels: <strong>The</strong> student may needbasic in<strong>for</strong>mation, a clarification of some aspect ofthat in<strong>for</strong>mation, and help in applying and integratingit into her or his personal situation.In<strong>for</strong>mational <strong>Advising</strong><strong>The</strong> least complex level of advising involvesthe simple act of providing in<strong>for</strong>mation. It includes,<strong>for</strong> example, the advisor answering basic questionspertaining to directions and assignments, or whenno complicating factors exist, it may include advisor-initiatedreferrals of students to campus locationsor individuals. An advisor may respond to astudent who is requesting basic in<strong>for</strong>mation by E-Table 1 <strong>The</strong> advising-counseling responsibility continuum<strong>The</strong> <strong>Continuum</strong>Session In<strong>for</strong>mational Explanatory Developmental Mentoring <strong>Counseling</strong>Purpose In<strong>for</strong>mational Clarification Insights Growth Pinpoint problemContent In<strong>for</strong>mation Procedures Options and Values Devise resolutionvaluesFocus <strong>The</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>The</strong> student <strong>The</strong> person Modification ofin<strong>for</strong>mation institution student’s behaviorLength of each 5–15 15–30 30–60 Varies; many Determined bycontact (minutes) contacts are severity ofmade problem<strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006 25

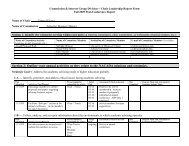

Kuhn et al.mail or as they meet walking across campus. Forexample, a student may approach an advisor andsay: “A couple of weeks ago you told me about astudy skills course, and I have <strong>for</strong>gotten the number.Would you please give it to me again?” Basicin<strong>for</strong>mation is often provided in handouts or onadvising Web sites.Explanatory <strong>Advising</strong>Through explanatory advising, one attempts toclarify in<strong>for</strong>mation that a student must use to takeaction. Explanatory advising might involve a discussionof certain campus policies or procedures. Itmay also involve explaining curricular or majorrequirements, such as the number and level of mathcourses that are required in a certain curriculum. Forexample, a student may present the following situationto the advisor: “This summer I want to take acourse at the community college near my home. Canyou tell me how I can transfer the credit back here?”Developmental <strong>Advising</strong>Developmental advising entails an advisoradviseerelationship that is more personal in naturethan are the in<strong>for</strong>mational or explanatory types.Advisors support students in <strong>for</strong>ming and clarifyingmeaningful educational plans that are compatiblewith their personal goals (Chickering, 1994;Creamer & Creamer, 1994; Crookston, 1972).Rather than just in<strong>for</strong>ming or explaining curricularor campus procedures to students, advisors offerthe in<strong>for</strong>mation in the context of students’ needs,values, goals, and personal situations. Studentsmay approach the advisor with the followingdilemma: “I’m no longer sure I want to major in premed,but I don’t know what to do about it.”Mentoring<strong>The</strong> most personal advising relationship is mentoring,which is an ongoing, caring relationship inwhich an advisor gives time, support, and encouragementto the mentee. <strong>The</strong> advisor is a role modeland friend who takes a caring interest in students’academic progress and helps them achieve theirpotential.Personal <strong>Counseling</strong>When advisors determine that students’ problemsare beyond their expertise, referrals to a counselorare indicated. <strong>The</strong> issues that involve personalor adjustment concerns are often more complicatedthan those related solely to academics. Aroommate problem, <strong>for</strong> example, may have reacheda point where it is not only disturbing a student’sstudy time but is creating a disruptive personalrelationship as well. Counselors may also fulfill therole of therapist when a student’s problems aresevere or debilitating.<strong>Advising</strong> and <strong>Counseling</strong> ComparedButler (1995, p. 108) gave an apt description ofadvising and counseling in the following quotation:Although counselors and academic advisorsmay employ the same processes with students,academic advisors are more concerned withhelping students learn in<strong>for</strong>mation-seeking,analytical, and developmental skills so theycan meet the institutional expectations <strong>for</strong> successfulacademic achievement, graduation,and employment. Emphasis is placed on thestudents’ adaptation to the institution’s standards.Counselors assist students to learn selfexploration,analytical, decision-making, andbehavioral skills to enhance their abilities tomake effective personal choices. Emphasis isplaced on students becoming unique individualswith awareness of their values and goals.<strong>The</strong> responsibilities <strong>for</strong> advising and counselingare compatible and overlapping. Students areseeking to be successful in their academic pursuitsas well as to be fulfilled individuals whose valuesand beliefs are reflected in their academic,social, and personal goals. Students’ issues canbe complex and intertwined with personal andacademic elements, which make defining preciseresponsibilities <strong>for</strong> advisors and counselors difficult(Shane, 1981). Both advisors and counselorshelp students set goals so they can improve their personalfunctioning, identify barriers that may impactsuccessful accomplishment of their goals, developstrategies to accomplish these goals, and assesswhether or not the strategies are successful.Student Issues and Concerns<strong>The</strong> issues and problems that students bring toadvisors are varied and at times complex. Table 2displays a wide variety of problems that undergraduatesmay bring to an advising appointment.Conceding possible exceptions, we shaded thecolumns to suggest with whom the responsibility<strong>for</strong> each issue rests. Table 2 lists many issues, someof which may require that the student receive indepth,long-term counseling assistance. <strong>The</strong> severityof the issue (problem) and the student’s copingabilities should be factors in deciding whether theproblem is best handled by the advisor or if the studentshould be referred to a counselor.26 <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006

<strong>Advising</strong> <strong>Referral</strong> <strong>Triggers</strong>Table 2 Typical issues students bring to academic advisorsSuggested Primary Responsibility asIssue Advisor Either/Or CounselorCourse selectionRegister <strong>for</strong> classesAdvanced placementDrop a classExit institutionDegree requirementsAcademic probationUnfair grade from professorDeath in familyTime managementUnderachievementMid-life career changeDecision makingAcademic goalsPersonal goalsCareer goalsInterpersonal relationshipFamily relationshipsAD/HDSubstance abuseEating disorderPhysical/emotional abuseSexual orientationSexual harassmentRacial discriminationSuicide<strong>The</strong> Line between <strong>Advising</strong> and <strong>Counseling</strong>When examining the list of student concerns inTable 2, some advisors may feel com<strong>for</strong>table discussingany of the problems, while others may feelthey cannot adequately deal with some of theseconcerns. For instance a simple question <strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mationabout any topic can be handled by the advisor(e.g., “Is there a chess club at this campus?”);however, a statement like “I’m very depressed andthinking of committing suicide” would call <strong>for</strong> animmediate referral to a counselor.Any of the issues in Table 2 could create a need<strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation, explanation, clarification, mentoring,or counseling. For instance, course selection<strong>for</strong> a new freshman could be straight<strong>for</strong>ward andmerely require that the advisor provide some in<strong>for</strong>mationfrom the catalog or some explanation of theimplications of this in<strong>for</strong>mation with regard to studentexpectations. On one hand, if the student is ina major such as nursing, where the requirements arefairly inflexible over a 4-year projection, then thestudent’s only choices may be limited to the generaleducation requirement <strong>for</strong> that semester. On theother hand, course selection <strong>for</strong> a junior exploratorymajor who has already completed 60 semesterhours of general education requirements mayinvolve hard choices about establishing academicand career goals, deciding upon a major, and dealingwith conflicting parental expectations. If thatexploratory major has a grade-point average of2.00, then an exploration of the implications ofpoor time management, underachievement, and<strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006 27

Kuhn et al.academic probation may be needed. If a student evidencessigns of substance abuse or reeks of alcohol,then the advisor should be alert and broach thetopic. As these examples illustrate, no rule-boundapproach can be utilized rigidly or automatically.Advisors must be alert to all input, <strong>for</strong>mal andin<strong>for</strong>mal, verbal and nonverbal, to provide the bestpossible advice.Communication BarriersTwo potential communication barriers <strong>for</strong> bothadvisors and counselors are first, the FamilyEducational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) of1974, which restricts the in<strong>for</strong>mation that can bereleased from a student’s educational record, andsecond, the confidentiality policy of advising andcounseling centers. FERPA requires schools to havewritten permission from eligible adult students or parentsof minor students to release any nondirectoryin<strong>for</strong>mation from a student’s education record, but itallows student in<strong>for</strong>mation to be shared with “schoolofficials with legitimate educational interest” (U. S.Department of Education, n.d.). While FERPA makesprovision <strong>for</strong> advisors and counselors to share in<strong>for</strong>mationabout a student, the policies of counseling andadvising offices are often more restrictive than thefederal mandate; some adhere to strict confidentiality.While remaining the designated advisor, academicadvisors routinely refer students with personalproblems to a counselor. <strong>The</strong>se policies can createcommunication barriers between advisors and counselorswho are both working with the same student.Advisors, counselors, and professors employed atinstitutions with strict confidentiality rules mustobtain the student’s explicit permission <strong>for</strong> consultationto take place. If such permission is notrequested, or is not granted by the student, thenin<strong>for</strong>mation about the student cannot be exchanged.For these reasons, advisors must indicate to newadvisees that unlimited confidentiality cannot bepromised because all future circumstances cannotbe predicted.Should the student share in<strong>for</strong>mation that suggeststhe student may injure self or others,then the principles of beneficence (to do good),nonmalfeasance (do no harm) and the legaldirectives of a duty to protect and a duty towarn would take precedence over maintainingconfidentiality and require that the advisor orcounselor consult with another appropriate,responsible person. (Butler, 1995, p. 114)<strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, advisors and counselors must establishthe boundaries <strong>for</strong> confidentiality with each adviseein the beginning so that uncom<strong>for</strong>table situations donot evolve later.<strong>Triggers</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Referral</strong>When considering whether to refer a student toa counselor, advisors should be alert to changes intheir advisees’ behaviors, emotions, or thinking.At the extreme, threats to get even, commit suicide,harm others, or to cease taking prescribed medicationswould call <strong>for</strong> referral. Likewise, students’speculation that they have attention deficit/hyperactivitydisorder (AD/HD) because their mathematicsclass is difficult <strong>for</strong> them would call <strong>for</strong> areferral to the Students with Disabilities Office <strong>for</strong>subsequent evaluation and diagnosis by a licensedprofessional. Stressful times, around the beginningand end of the semester, can be full of triggering situations<strong>for</strong> freshmen.Ability to cope can be significantly influencedby the interaction of personal problems such as a)depression or other emotional or physical disorders;b) interpersonal and family issues such as divorce,relationship breakups, pregnancy, or death; and c)community, national, and global tragedies such as9-11 and devastating, large-scale natural disasters.Advisors need to be alert to all three sources ofstress, especially around traditionally stressfultimes. <strong>The</strong> inability to cope with the day-to-day routineand functions of attending class, reading, studying,sleeping, eating, and working can also beserious behavioral triggers.When an advisee’s affect is anxious, flat, grieving,angry, withdrawn, paranoid, or frightened, theadvisor should be alert to the need <strong>for</strong> referral.Other interview behaviors such as wringing ofhands, rapid tapping of hands or feet, uncontrollablecrying, disheveled appearance, sweating, or rapidor slurred speech should invite careful scrutiny.<strong>The</strong> effects of physically destructive behaviors(self-medicating, overmedicating or undermedicating,and alcohol or drug use) are frequently triggers<strong>for</strong> referral to counselors or other professionals,especially <strong>for</strong> students with disabilities who may relyon medication to help their level of functioning.During stressful periods, affective or behavioralsymptoms that are usually controlled may suddenlymanifest themselves in tics, agitated behavior,stuttering, hyperactivity, or hypoactivity.Advisors need to know their advisees and developa sense of their typical behavior, because studentsin distress may not readily have the words todescribe adequately their problems.Harper and Peterson (2005) listed some othersignals of distress that advisors should recognize.28 <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006

<strong>Advising</strong> <strong>Referral</strong> <strong>Triggers</strong><strong>The</strong>se include excessive procrastination; listlessness;sleeping in class; marked changes in personalhygiene; too frequent advisor visits (dependency);or impaired speech or disjointed thoughts.Obviously, students who report self-abuse or abuseby others (self-mutilation, cutting, physical abuse,sexual abuse, date rape, anorexia, or bulimia)require immediate referral <strong>for</strong> assessment and treatment.Recognizing active and passive symptoms ofsuicide ideation requires special professional orgraduate training, and there<strong>for</strong>e, an advisor concernedabout a student’s safety should make a referralto a counselor.Table 3 presents some samples of behaviors thatan advisor might observe that may prompt referralto another office or student service area. In somecases, advisors should be on the alert <strong>for</strong> multipletriggers that in combination may culminate in aneed <strong>for</strong> referral. For instance, a nontraditional studentwho is working full-time, recently divorced, raisingtwo children alone, and taking classes may looktired because he or she is exhausted and not becausethe individual is having psychological issues. Whilethis student may evidence the same symptoms as atraditional 18-to-22-year-old, his or her challengeswill likely be best addressed by different resourcesthan those to which traditional undergraduates arereferred. Similar symptoms can have multiple causesand depend on the intellectual, emotional, financial,or other factors that a student is experiencing.SummaryAdvisors are often the first persons on campusto whom a student may express a problem orTable 3 Sample referral observations (triggers)Advisor Observations1 Depressed junior has no commitment to any major.2 Pre-med major is failing math and chemistry.3 Freshman’s grades drop after death of father.4 Student does not accept responsibility <strong>for</strong> poor grades.5 Sophomore is in denial about precarious academic situation.6 Student’s transfer hours will not apply to desired major.7 Freshman has no approach to making decisions.8 Freshman male cannot study because roommate keeps late hours.9 Freshman female is having relationship problem with boyfriend.10 Female refuses professional counseling because of mother’s advice.11 Nontraditional student’s spouse resents her pursuing higher education.12 Recently divorced parents refuse to pay <strong>for</strong> sophomore’s college expenses.13 Freshman cannot communicate with domineering parent.14 Normally nicely dressed student shows up looking disheveled.15 Student reports not attending one or more classes.16 Bright honors student quits participating in cocurricular activities.17 Student reports being tired all the time.18 Senior says she is depressed.19 Student cries uncontrollably over inability to cope.20 Student smells of alcohol.21 Struggling freshman is unwilling to request accommodations <strong>for</strong> diagnosed AD/HD disorder.22 Student has prolonged incapacitation due to auto accident.23 Student reports not taking prescribed medications because they are too expensive.24 Student is unable to generate solutions <strong>for</strong> stressors in his or her life.25 Female student claims to have been sexually harassed by another student.26 Student asks to be withdrawn from school because of financial concerns.27 Nontraditional student is under pressure from multiple demands of school, job, and family.Note. Numbers are nominal and imply no particular ordering.<strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006 29

Kuhn et al.dilemma that is beyond an academic concern.Advisors’ primary responsibility is to help studentsobtain in<strong>for</strong>mation and develop skills to achievetheir academic aspirations, and sometimes theirexpertise cannot be used to address problems;instead the student requires personal counseling.Unlike advisors, counselors assist students withpersonal and social problems and help them copewith difficult personal and social transitions andevents so that they are better equipped to managetheir lives. <strong>The</strong> intent of both advisors and counselorsis to facilitate students’ self-exploration anddevelopment of effective analytical decision-makingskills so that their college experience is positiveand productive. As their advisees move through acomplex maze of academic, social, and personal situations,advisors need to recognize the triggersthat indicate a referral to a counselor. When advisorsand counselors work cooperatively and in tandem,students are the beneficiaries.Suggestions <strong>for</strong> Future ResearchFuture research might include a study in whichcounselors and advisors are interviewed about theirperceptions of each other’s roles. Another studycould be conducted to determine whether or notcounselors or advisors agree with the issues listedin Table 2. Whether a clear distinction can be madeabout the appropriate triggers <strong>for</strong> any given referralcould drive a third research project in which studentscould be interviewed about their receptivityto getting help from official offices and personnel(both advisors and counselors). Also, researcherscould describe an advising-counseling continuum<strong>for</strong> community colleges.ReferencesAmerican <strong>Counseling</strong> Association. (2002). Professionalcounselors helping people. RetrievedJuly 19, 2005, from www.counseling.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=PROFESSIONAL_COUNSELORS_HELPING_PEOPLEButler, E. R. (1995). <strong>Counseling</strong> and advising: Acontinuum of services. In R. E. Glennen & F. N.Vowell (Eds.), Academic advising as a comprehensivecampus process (Monograph No. 2, pp.107–14). Manhattan, KS: National Academic<strong>Advising</strong> Association.Chickering, A. W. (1994). Empowering lifelongself-development. <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal, 14(2),50–53.Creamer, D. G., & Creamer, E. G. (1994). Practicingdevelopmental advising: <strong>The</strong>oretical contextsand functional applications. <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal,14(2), 17–24.Crookston, B. B. (1972). A developmental viewof academic advising as teaching. Journal ofCollege Student Personnel, 13(1), 12–17.Harper, R., & Peterson, M. (2005). Mental healthissues and college students. <strong>NACADA</strong> clearinghouseof academic advising resources. RetrievedJune 27, 2005, from www.nacada.ksu.edu/Clearinghouse/<strong>Advising</strong>Issues/Mental-Health.htmHobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychologicalresources and adaptation. Review of GeneralPsychology, 6(4), 307–24.McWhirter, B. T. (1997). Loneliness, learnedresourcefulness, and self-esteem in college students.Journal of <strong>Counseling</strong> and Development,75(6), 460–69.Shane, D. (1981). Academic advising in highereducation: A developmental approach <strong>for</strong> collegestudents of all ages. <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal, 1(2),12–23.U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). FamilyEducational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).Retrieved February 28, 2005, from www.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.htmlAdditional ResourcesRelevant Web Sites <strong>for</strong> <strong>Advising</strong> Definitions(All were retrieved on June 25, 2005)www.nacada.ksu.edu/Journal/journal_help.htmwww.nacada.ksu.edu/Clearinghouse/Research_Related/definitions.htmwww.ferrum.edu/arc/advg/pref.htmwww.valenciacc.edu/lifemap/pbs/damodeldescription.htmwww.students.uidaho.edu/default.aspx?pid=34434www.casa.colostate.edu/advising/facman/chapter1/definition.cfmwww.tcnj.edu/~advising/define.htmlwww.uta.edu/advisorhandbook/intro.htmwww.psu.edu/dus/mentor/020816va.htmAuthors’ Note<strong>The</strong> authors acknowledge the contributions to thedevelopment of this manuscript that were made byTerri Rothman, Monmouth University; MarkRehfuss, Regent University; Melinda McDonald,<strong>The</strong> Ohio State University; and Melissa Mentzer,Kent State University.Terry Kuhn is professor of Music and Vice Provost<strong>for</strong> Undergraduate Studies Emeritus at Kent StateUniversity. He has published articles and books inthe field of music education. Readers may contactDr. Kuhn at tkuhn@kent.edu.30 <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006

<strong>Advising</strong> <strong>Referral</strong> <strong>Triggers</strong>Virginia N. Gordon is Assistant Dean Emeritus at<strong>The</strong> Ohio State University and has published manybooks and journal articles in the areas of academicand career advising. Readers may contact Dr.Gordon at Gordon.9@osu.edu.Jane Webber is assistant professor of counseling inthe Educational Leadership and Special EducationDepartment at Monmouth University. She haspublished books and articles in the area of schoolcounseling, trauma counseling, and disasterresponse. She is also a part-time counselor atthe McClintock Center <strong>for</strong> <strong>Counseling</strong> andPsychological Services at Drew University. Readersmay contact Dr. Webber at jwebber@monmouth.edu.<strong>NACADA</strong> Journal Volume 26 (1) Spring 2006 31