Monographs on teacher.. 9808 v5 - Umeå universitet

Monographs on teacher.. 9808 v5 - Umeå universitet

Monographs on teacher.. 9808 v5 - Umeå universitet

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

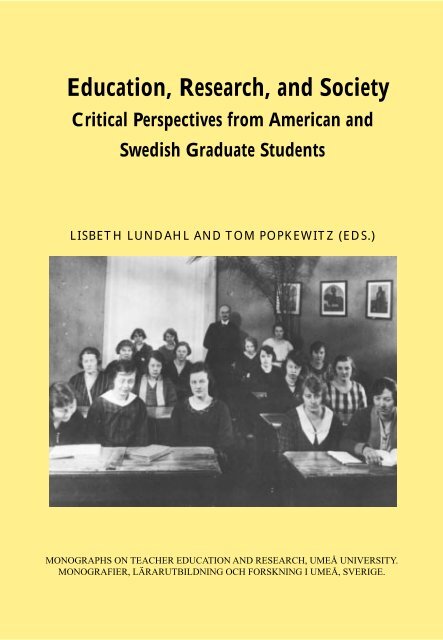

LISBETH LUNDAHLTOM POPKEWITZIntroducti<strong>on</strong>Since 1993, a Swedish governmental grant made possible a collaborativearrangement between <strong>Umeå</strong> University and The University of Wisc<strong>on</strong>sin-Madis<strong>on</strong>.The arrangement was to provide scholarly exchangesbetween the two faculty and graduate students. One aspect of theexchange was to have faculty visit the campus of the other instituti<strong>on</strong>and give seminars related to their <strong>on</strong>going students. Almost thirty facultyfrom the two universities have given such seminars at the otherinstituti<strong>on</strong>s campus and spent at least a week to work with faculty andgraduate students. The exchange has also involved joint symposia at theAmerican Educati<strong>on</strong>al Research Associati<strong>on</strong>´s annual meetings andparticipati<strong>on</strong> in the Thematic Network <strong>on</strong> Teacher Educati<strong>on</strong> in Europe(TNTEE).In 1996-97, the collaborative agreement extended its intellectualinterchange to a seminar for graduate students of the two instituti<strong>on</strong>s.Two seminars were organized to bring together graduate students fromeach of the instituti<strong>on</strong>s. One was held in <strong>Umeå</strong> in December, 1996 andthe sec<strong>on</strong>d <strong>on</strong>e in Madis<strong>on</strong> during April, 1997. The two of us wereresp<strong>on</strong>sible for coordinating the meetings.The purpose of the two seminars was simple. It was to put studentsin a resp<strong>on</strong>sible intellectual positi<strong>on</strong> in which they would have toarticulate the ideas of their research, to make the theoretical positi<strong>on</strong>savailable and understandable, and to maintain a high level of c<strong>on</strong>ceptualand methodological discussi<strong>on</strong>. Our purpose was also to engage in across nati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong> to examine our collective norms of educatingand reading to c<strong>on</strong>sider similarities and differences.The graduate students prepared papers that represented their <strong>on</strong>goingresearch projects. The papers would be written in a manner that wouldallow serious discussi<strong>on</strong> of the ideas and approaches taken in their dissertati<strong>on</strong>program. But the seminar papers were to reflect a differentkind of writing than that of writing a paper for a class. Students weretold that the intent was to prepare a paper that would be eventually7

publishable. The writing needed to be analytically clear but at the sametime, theoretically informed. Further, the paper was to be viewed as <strong>on</strong>eintellectual signative, identifying the problematic from which the studentunderstood the problems of the world of scholarship. In back of allof this, we wanted to make the stakes of the seminar as similar to the stakesthat are c<strong>on</strong>fr<strong>on</strong>ted when writing and engaging in intellectual life.The seminar was to provide a forum in which the graduate studentsresearch could be engaged in a small, intellectual circle of peers wherethere was the possibility of an intense discussi<strong>on</strong> about ideas. For thefirst seminar in <strong>Umeå</strong>, five papers were prepared from each of the twoinstituti<strong>on</strong>s that related to the graduate students dissertati<strong>on</strong>s. The paperswere written in English and distributed prior to the seminar.The seminar was scheduled for two and half days, with a relativelysimple organizati<strong>on</strong>. Rather than start with a paper presentati<strong>on</strong>, twostudents were asked to prepare comments and questi<strong>on</strong>s about the paper.These comments began the discussi<strong>on</strong>, followed by the paper writersresp<strong>on</strong>se, and then a general discussi<strong>on</strong> of the problem, methods, resultsand, in some instances, the problematic. The sec<strong>on</strong>d seminar in Madis<strong>on</strong>had the same format. In most instances, the students revised theirfirst papers in ways that were substantive and furthered the dialogueinitiated in the first,<strong>Umeå</strong> seminar.We saw the seminar, from its preparati<strong>on</strong> to the current publicati<strong>on</strong>of the papers, as a potentially important part of intellectual educati<strong>on</strong>of students interested in the scholarship of educati<strong>on</strong> and social science.It is rare that graduate students have the resources available to them toparticipate in a small research seminar such as the <strong>on</strong>e that was held.Further, it is even rarer that such a seminar can be cross-nati<strong>on</strong>al incharacter. We can immediately compare this seminar to the professi<strong>on</strong>almeeting that most of us go to in order to talk about our research. TheAmerican Educati<strong>on</strong>al Research Associati<strong>on</strong>´s annual meeting or theEuropean Educati<strong>on</strong>al Research Associati<strong>on</strong> meetings come to mind.Typically, papers are presented, sometimes with a reactor to frame thepositive and negative of the paper, but with little serious discussi<strong>on</strong>because of the time schedule. One advantage of such meeting for facultyis its invisible colleges, informal meetings with colleagues from otherinstituti<strong>on</strong>s to talk about <strong>on</strong>going work and to (re)establish c<strong>on</strong>tacts.8

For most graduate students, they do not have the c<strong>on</strong>tacts for suchinvisible colleges and the intellectual and communal discussi<strong>on</strong>s that itentails. This seminar provided the time and the organizati<strong>on</strong> to enablethe students to have a sustained and disciplined discussi<strong>on</strong> about theirresearch as well the paradigmatic assumpti<strong>on</strong>s that were made. Thec<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong>s began prior to the meetings as the two groups of studentspaired off to meet and discuss the ideas and organizati<strong>on</strong> of the seminarwith fellow students from another nati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>text.The substantive discussi<strong>on</strong> of the papers at the two symposia produceda reflective process at multiple levels. At a first level was a thinkingabout the different intellectual approaches of the two graduate studentgroups. The Madis<strong>on</strong> group was very much into post-modern socialand historical theories and wrote their papers in ways that reflected thisintellectual traditi<strong>on</strong>.From this first seminar, The University of Wisc<strong>on</strong>sin-Madis<strong>on</strong>students were part of a weekly seminar called the Wednesday Group. Inadditi<strong>on</strong> to their course work (individual units of study within the Ph.D.program), the students meet each week to read across the disciplinesthat range from political theory, to history and literary theory. It is fromthese readings and c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong>s that the dissertati<strong>on</strong> topics andmethodologies of the enclosed studies emerged. This emphasis <strong>on</strong> theoryand history is atypical of graduate students within the US but in thisc<strong>on</strong>text provided a way in which the two groups could talk in substantiveways as Swedish literature draw <strong>on</strong> multiple disciplines as well. Wesay this because this particular seminar is not typical of graduate studentsboth in its intellectual closeness and theoretical readings.This intellectual organizati<strong>on</strong> of studies posed a particular gloss tothe c<strong>on</strong>duct of the seminar. The empirical problem of the Madis<strong>on</strong>papers tended to be to relate historical text with theoretical questi<strong>on</strong>s,particularly that of the relati<strong>on</strong> of power and knowledge that is drawnfrom Michel Foucault and feminist theories. The <strong>Umeå</strong> papers, in c<strong>on</strong>trast,tended to move from the empirical problems under investigati<strong>on</strong>and also involved multiple intellectual traditi<strong>on</strong>s. The focus of the initialset of papers from <strong>Umeå</strong> tended to be more c<strong>on</strong>cerned with themoving from the ground up, that is from identifying the ways of handlingand interpreting data than from a discussi<strong>on</strong> of the theoretical9

students seemed to find this less important as they worked together.If we examine the initial discussi<strong>on</strong>, the framing of the seminar inEnglish posed a momentary problem for both groups. For the nativespeakers, it meant that the normal speed of talk and c<strong>on</strong>ceptual andlinguistic nuances related to nati<strong>on</strong>al cultures had to be c<strong>on</strong>sciouslythought about until a flow of communicati<strong>on</strong> could be established. Forthe <strong>Umeå</strong> students, it meant speaking in theoretical languages andcomplexities that were not a first language. At points, frustrati<strong>on</strong> wasexpressed. This frustrati<strong>on</strong> was that when the words came out in English,its seemed so simplistic and c<strong>on</strong>densed the thoughts in a way thatthe Swedish students did not always feel comfortable with. This frustrati<strong>on</strong>,by the end of the first seminar, seemed less of a problem as theflow of ideas and discussi<strong>on</strong> were intense.The differences, we need to stress, were seen by the students as not asgreat as they initially thought. But it required the students to understandthe differences in ways in which students cross-examine, ask questi<strong>on</strong>s,and engage in criticism. Above all the cultural and theoreticaldifferences and the resulting discussi<strong>on</strong>s were seen as highly stimulatingand creative in the subsequent research work of the students.The intellectual dialogue was also helped by the social c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong>sthat occurred in <strong>Umeå</strong> and Madis<strong>on</strong>. In both seminars, students arrivedearlier than the actual day of the seminar and spent time for sightseeingand meetings in social c<strong>on</strong>texts. While visits to bars and the listeningto music tend not to count in the rec<strong>on</strong>structed logic of science,the social was a part of the intellectual.Then there was the seemingly mundane that was not mundane. Intalking about publishing, for example, we discussed what makes a bookworthwhile to published. How does <strong>on</strong>e go about talking to publishersor sending articles to journals? How do you succeed working towardsdeadlines when there are so many other things to do? These questi<strong>on</strong>swere not <strong>on</strong>ly procedural but also about how ideas come to circulatewithin intellectual communities and the seminar provided a c<strong>on</strong>cretesite to c<strong>on</strong>sider these broader issues of career.11

DAWNENE D HAMMERBERGDisrupted Assumpti<strong>on</strong>s:Social and Historical C<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>s of Literacy,Illiteracy, and E-literacyThis paper is meant to disrupt presumptive truths of the present byunsettling c<strong>on</strong>trolling factors of the past which have been understoodas essential to the unfolding of history. As an example, various forms of”technology” have been seen as fundamental to history’s ”development.”However, this paper seeks to disrupt understandings of history whichchr<strong>on</strong>ologically narrate time as a natural progressi<strong>on</strong> through technologicaldevelopments. In additi<strong>on</strong>, the acti<strong>on</strong>s and movements of particularpeople in particular historical moments have also been seen as the basesfor historical change. Yet, this paper disrupts the noti<strong>on</strong> of history as asuccessi<strong>on</strong> of events enacted by human beings who are independentagents outside of time and temporal rati<strong>on</strong>alities. More specifically, thispaper is meant to disrupt present noti<strong>on</strong>s of literacy, illiteracy, andelectr<strong>on</strong>ic literacy (e-literacy) through a history that tells of theassumpti<strong>on</strong>s that have separated and elevated writing and print fromother forms of communicati<strong>on</strong>.In many ways, the realm of c<strong>on</strong>ceivability for disrupting assumpti<strong>on</strong>sof the present comes from a particular reading of the past. Foucault’sgenealogy is a method of reading history which problematizes theassumpti<strong>on</strong>s and generalities that appear as natural or self-evident inthe discourses of the day. While this paper does not attempt to write agenealogy of ”literacy,” it does take as its starting point the facets of agenealogical history which are disruptive to assumpti<strong>on</strong>s of the present1 . Genealogy, as a history of the present, has very real implicati<strong>on</strong>swhen the grounds up<strong>on</strong> which present-day assumpti<strong>on</strong>s are built canbe investigated and appraised for their inclusi<strong>on</strong>ary and exclusi<strong>on</strong>aryprescripti<strong>on</strong>s, their real and imagined promises, their limited and limitingprospects 2 .Through historical examples, this paper problematizes some presentassumpti<strong>on</strong>s about ”literacy.” These assumpti<strong>on</strong>s are grouped together13

which come with an underlying assumpti<strong>on</strong> of cultural and societal”democratizati<strong>on</strong>.”However, this understanding of ”literacy” as necessary and powerfulhas its history, and the ”power” associated with literacy is not anautomatic given. For example, in primary oral cultures, which Ong(1982) defines as ”cultures with no knowledge at all of writing” (p. 1),”literacy” has no power, since there is no knowledge whatsoever of ”it,”or of what it can do. Instead, value and power are attached in thesecultures to accustomed oral traditi<strong>on</strong>s, just as value and power areattached in the dominant cultures of our time to accustomed literatetraditi<strong>on</strong>s. Cultural producti<strong>on</strong> and knowledge circulati<strong>on</strong> can happenboth with and without writing, and in fact, ”literacy” can <strong>on</strong>ly be culturallyproductive when the culture places a value <strong>on</strong> the written word and itsuses. It may be difficult to understand, from a literate standpoint in thepresent, how the ”inventi<strong>on</strong>” of the alphabet had little to no c<strong>on</strong>sequenceto the cultures of the time. And yet, as Whitaker (1996) points out:It is an obvious but sometimes neglected point that, in the eighthcentury, when the alphabet was invented and used for the first time towrite Greek, it had neither a l<strong>on</strong>g traditi<strong>on</strong> of written literature nor anyof the associati<strong>on</strong>s of a dominant culture attaching to it - as it almostalways did when it was used in later periods of history to write otherlanguages. To put it crudely: the first Greek who learned the alphabethad nothing to read. On the c<strong>on</strong>trary, in archaic Greece the culture towhich all the power and prestige bel<strong>on</strong>ged, was the oral <strong>on</strong>e; throughoutmost of this period there was no traditi<strong>on</strong> other than the oral to whichpoets could turn for inspirati<strong>on</strong> and material, nor any audience otherthan listeners to whom they could address themselves. (p. 216)Literacy, in other words, has not always been a necessary form ofcommunicati<strong>on</strong>, and in fact, has been seen as a hindrance to trulycommunicative communicati<strong>on</strong>. Plato’s Socrates, for example, criticizedwriting because it interfered with established habits of communicati<strong>on</strong>,destroying memory rather than enhancing it, and fragmenting socialrelati<strong>on</strong>ships (see Langham, 1994) 4 . Struggles against the technologiesof reading and writing manifested themselves at various points in history,as tensi<strong>on</strong>s between ”literate” ways of being and ”oral” ways ofbeing, as if the two can be separated, divided countries and groups of15

people. For example, Myers (1996) explains that Medieval France”became split between Southern France (le Pays du Droit Écruit), whichacknowledged the written laws of Roman law, and Northern France (lePays du Droit Coutumier), which acknowledged oral societies and localuses” (p. 30). In additi<strong>on</strong>, Myers goes <strong>on</strong> to say that similar tensi<strong>on</strong>sexisted during the Norman invasi<strong>on</strong> (1066-1307) when the ”Normanswanted to eliminate the use of local, oral authenticati<strong>on</strong> of ownershipof property in the England of the Middle Ages because those methodsallowed the local, native Anglo-Sax<strong>on</strong>s of England to c<strong>on</strong>trol their ownproperty through pers<strong>on</strong>al relati<strong>on</strong>s (oaths of witness) and other methodsof local authenticati<strong>on</strong>” (p. 30; see also Street, 1984; Clanchy, 1979).Even later, writing was often viewed as sec<strong>on</strong>dary to oralcommunicati<strong>on</strong>s. For example, during the late 1200s in Europe, writingwas not c<strong>on</strong>sidered ”trustworthy” when compared to face-to-face oralcommunicati<strong>on</strong>s in courts and in daily business interacti<strong>on</strong>s 5 . Even aslate as the Reformati<strong>on</strong> (1600s), in Europe and in the col<strong>on</strong>ies of NorthAmerica, oral c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s linked people and businesses moreso than”literacy” (see Myers, 1996; Street, 1984; Clanchy, 1979).These tensi<strong>on</strong>s, however, did not occur because of some ”natural”divide between ”literacy” and ”orality.” In fact, how ”literacy” was usedand valued depended up<strong>on</strong> the already established rules of oral traditi<strong>on</strong>s.In other words, understandings of appropriate oral communicati<strong>on</strong>methods and topics were already invested with enough relevance thatthese practices were able to shape understandings of the ”appropriate”methods and topics for reading and writing. For example, when writtenrecords slowly became more customary during the late 1700s in theUnited States, it was due to ”an increasing amount of travel [which]helped to shift social practices from face-to-face interacti<strong>on</strong>s withacquaintances to interacti<strong>on</strong>s with strangers” (Myers, 1996, p. 32), butthese written interacti<strong>on</strong>s were based <strong>on</strong> the preservati<strong>on</strong> of oralagreements. Tensi<strong>on</strong>s between accepted communicati<strong>on</strong>s techniquesoccur when the rules governing how <strong>on</strong>e ”should” communicate in <strong>on</strong>elocal space come in c<strong>on</strong>flict with how <strong>on</strong>e ”should” communicate inanother local space. As writing and print gained leverage in the 1700s,the tensi<strong>on</strong>s between various communicati<strong>on</strong> techniques were lessapparent as print penetrated people’s lives indirectly through an under-16

standing that oral serm<strong>on</strong>s and speeches were written down, and througha general acceptance that writing and print were effective ways to c<strong>on</strong>ductbusiness (see Myers, 1996, p. 33, 39). In other words, the circumstancesof cultures which accept ”literate” techniques are such that various socialneeds are obviously fulfilled through writing and print, not that thetechnologies of writing and print enter the culture <strong>on</strong> vacant grounds 6 .Particular acts of reading and writing, therefore, become viewed as”necessary” in particular social circumstances and discourses of what isworthwhile.The necessity of writing and print for the development of such fieldsas science and history may seem m<strong>on</strong>umental because in many wayswritten records enable a form of thought that allows for a different typeof knowledge formati<strong>on</strong> and organizati<strong>on</strong> (see, for example, MacNevin,1993; Ong, 1982; Clanchy, 1979; Graff, 1979; Diringer, 1948).However, it is not the written records ”themselves,” nor literacy ”itself,”that enable an altered form of thinking. The fact that reading and writinglend themselves well to scientific inquiry or particular tellings of historyhas less to do with ”literacy” than to the social and historical milieuwhich allows certain forms of thought to flourish over others. Sincedefiniti<strong>on</strong>s of ”literacy” are determined by cultural understandings ofwhat is worthwhile, the matters that are recorded in writing, as well asthe c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al understandings of how written records are to beperceived and read and used and by whom, are also determined bycultural understandings of what is worthwhile. Therefore, it is not”literacy” that is necessary for science or modernity or emancipati<strong>on</strong>.Instead, social and historical circumstances enable shifts in particularversi<strong>on</strong>s of knowledge creati<strong>on</strong> and producti<strong>on</strong>; social and historicalc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s promote (or repress) changes in patterns and organizati<strong>on</strong>sof thought.For example, a versi<strong>on</strong> of general understanding that enables modernscience involves the distincti<strong>on</strong> between the ”given” world and the”inferences” or ”hypotheses” that are c<strong>on</strong>ceived by human beings. Inpart, this divisi<strong>on</strong> has its roots in the Reformati<strong>on</strong>, when a differentway to think about religious texts emerged (see Ols<strong>on</strong>, 1991). Beforethe Reformati<strong>on</strong>, there was no distincti<strong>on</strong> between what was said in thetext and what was interpreted by the reader. A text’s interpreted meaning17

was seen as exactly the same thing as what the text really said, as in theactual intent of God being taken from scriptural readings. Although Stock(1983) has shown that the ”heretics” of the Middle Ages based their theology<strong>on</strong> a different type of interpretati<strong>on</strong>, Ols<strong>on</strong> (1991) also points out that:...while heretics recognized the interpretati<strong>on</strong>s of the Church asinterpretati<strong>on</strong>s - as man-made - they did not recognize their owninterpretati<strong>on</strong>s as interpretati<strong>on</strong>s. They, like the medieval church, tooktheir interpretati<strong>on</strong>s to be the <strong>on</strong>es intended by God, and hence, theydied, apparently happily, at the stake for them. (p. 153-154)Since ”interpretati<strong>on</strong>” was not viewed as the issue at hand, religiousstruggles were based <strong>on</strong> what God actually meant, as understood intraditi<strong>on</strong>al dogma, as trusted in a larger understanding of text than thegiven/interpreted dichotomy can allow. Even when the Scripture accordingto Aquinas had several layers of meaning in the late 1200s, all meaningswere thought to reside in the given text (see Ols<strong>on</strong>, 1991, p. 154).C<strong>on</strong>victi<strong>on</strong>s and beliefs that may not have been explicitly stated in the textwere nevertheless seen as part of the text and its meaning. It was allintertwined. However, in the first half of the sixteenth century during theReformati<strong>on</strong>, an interpretive break was being made. Ols<strong>on</strong> (1991) writes:The interpretive principle of the Reformati<strong>on</strong>, as expressed forexample in Luther’s attitude to the Scripture, was that Scripture is”aut<strong>on</strong>omous,” it does not need interpretati<strong>on</strong>, it needs reading; it meanswhat it says. All the rest is made up, a product of fancy or traditi<strong>on</strong>. Itwas this distincti<strong>on</strong> between the given and the interpreted that launchedthe Reformati<strong>on</strong> and, a century later, opened ”the book of nature” tomodern scientists.... (p. 154)Ols<strong>on</strong> goes <strong>on</strong> to explain that the metaphor of nature as ”God’s book”that was customary in the Middle Ages took <strong>on</strong> a literal meaning in the1600s when modern scientists such as Galileo, Isaac Newt<strong>on</strong>, and FrancisBac<strong>on</strong> made the distincti<strong>on</strong>s between what was ”given” in the text ofnature (observed facts) and what was theoretically interpreted or inferred.Therefore, according to Ols<strong>on</strong>, ”it may be argued that modern sciencewas the product of applying the distincti<strong>on</strong>s evolved for understandingthe book of Scripture, namely that between the given and the interpreted,to the book of nature” (pp. 154-155). However, the point here is thatthe distincti<strong>on</strong>s between observed facts and imagined hypotheses are18

The rati<strong>on</strong>alizati<strong>on</strong>s for assumpti<strong>on</strong>s such as the <strong>on</strong>es grouped in thisfield are based entirely up<strong>on</strong> the dominant status of cultures which viewthemselves as superior due to the fact that they are ”scientific” or ”modern”or ”democratic.” However, an analysis of the historical and intimaterelati<strong>on</strong>ships between ”orality” and ”literacy” helps to explain thathumankind’s ”development” from ”oral cultures” to ”literate cultures”is not a progressi<strong>on</strong> toward a better way to transmit language, nor a”natural” outgrowth of oral ways of being, but instead an unfolding ofvarious rule-governed c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>s for the circulati<strong>on</strong> of language. Oralcommunicati<strong>on</strong>s never went away or came back; instead, the ways peoplehave been able to communicate orally (and about what, and throughwhat medium), just like the ways people have been able to communicateliterately (and about what and through what medium), have shiftedover time with the discursive practices which name the ”appropriate”means and modes of thought circulati<strong>on</strong>. Once again, genealogy viewsthe history of the ”literate subject” not <strong>on</strong>ly in relati<strong>on</strong> to the technologiesof writing and print, but also in relati<strong>on</strong> to social practices outside ofthe realm of the printed word. Shifts in the definiti<strong>on</strong>s of ”literacy,” inother words, are viewed for their complicity with social and historicalbeliefs and c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>s, not as changes that were ”meant” to happen,nor as changes that will eventually culminate in a final and best way of”being literate.””Orality” is a relatively recent term devised and used by anthropologists,sociologists, and psychologists over the past thirty years as aparallel to ”literacy” (see Ong, 1982, p. 5; Thomas, 1992, p. 6). It ismeant for purposes of analysis and comparis<strong>on</strong> in light of theoverwhelming influence of writing and print 9 . ”Oral” means ”utteredby the mouth” or ”spoken” 10 , and ”orality” is a way of describing, inThomas’ (1992) terms, ”the habit of relying entirely <strong>on</strong> oral communicati<strong>on</strong>rather than written” (p. 6). The term has been useful and positivein the work of Ong and others who mean to dispel the misc<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>that strictly oral cultures are severely limited in cultural growth andrefinement. It is also meant as a way to describe ”thought and its verbalexpressi<strong>on</strong> in oral culture” as compared to ”thought and expressi<strong>on</strong> inliterature, philosophy and science, and even in oral discourse am<strong>on</strong>gliterates, [which] are not directly native to human existence as such but20

have come into being because of the resources which the technology ofwriting makes available to human c<strong>on</strong>sciousness” (Ong, 1982, p. 1).Yet the term ”orality” can also serve to separate two forms of culturalproducti<strong>on</strong> which are deeply interwoven.When it is presumed that there has been a natural and progressivedevelopment in communicati<strong>on</strong> techniques from the oral to the writtento the printed to the electr<strong>on</strong>ic, the ”differences” between ”orality” and”literacy” that appear in the ”electr<strong>on</strong>ic age” manifest themselves in termsdefined <strong>on</strong> ”literate” grounds which are already presumed to be superior.On this terrain, where writing and print are viewed as necessary forfields of thought such as science, philosophy, and history 11 , where”literacy” is equated with ”civilizati<strong>on</strong>” and ”progress,” it is easy to(mis)understand writing, print, and electr<strong>on</strong>ic communicati<strong>on</strong>s as thetools which have brought about levels of knowledge that are ”higher” or”better” than the wisdom (often viewed as folky 12 ) available in primaryoral cultures 13 . However, it should be remembered that the separati<strong>on</strong>of ”literacy” from ”orality” <strong>on</strong>ly occurs <strong>on</strong> a terrain where ”literacy” isalready overwhelmingly dominant. On this terrain, ”literacy” can beoutlined <strong>on</strong> the rooftops and garden penthouses of a civilized skyline,or electrified in the gated communities of technological advancements,or perpetuated in the ivory towers of scholarship and intellectual racism 14 ,while the c<strong>on</strong>tours of ”primary orality” can barely be glimpsed from a”literate” perspective and most often must be imagined, which makesthem look identical to the c<strong>on</strong>tours of ”illiteracy” 15 .Pattanayak (1991) depicts the c<strong>on</strong>tours represented in particular discoursessurrounding ”literacy” and its ”opposite” by writing: ”Illiteracyis grouped with poverty, malnutriti<strong>on</strong>, lack of educati<strong>on</strong>, and healthcare, while literacy is often equated with growth of productivity, childcare, and the advance of civilizati<strong>on</strong>” (p. 105). However, this c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>of literacy/illiteracy is not without its history, and is completely tiedwith relati<strong>on</strong>s of power. If we were to imagine the terrains of ”primaryorality,” we would have to imagine a land where ”illiteracy” is not aproblem, not an issue by any means. ”Orality,” when it is truly ”primary,”has no visi<strong>on</strong>s of ”literacy” or ”illiteracy,” since the centuries of intellectual”growth” associated with the techniques of writing are not at allsignificant to cultures with no knowledge whatsoever of writing. ”The21

introducti<strong>on</strong> of writing,” writes Hoyles (1977), ”made illiteratesinevitable” (p. 23). However, in our imaginati<strong>on</strong>s, we have to w<strong>on</strong>derhow ”inevitable” the ”illiterates” could have possibly been in cultureswho had been operating for centuries without writing. These cultureslived in what we would term ”illiterate” envir<strong>on</strong>ments, but they didn’tknow these were faulty and inferior envir<strong>on</strong>ments, because they weren’t.There was nothing to be inferior to.When writing was ”invented” around 3100 B. C., probably by theSumerians, with the development of systems for writing occurring sometimebetween 3100-1599 B.C. (MacNevin, 1993; Schmandt-Besserat,1988; Graff, 1987; Diringer, 1948), it was tied directly to spoken ideas,but was not meant to represent all spoken ideas. Writing began withpictures and direct representati<strong>on</strong>, often ic<strong>on</strong>ographic, and then movedto more mnem<strong>on</strong>ic mechanisms which carried the meanings of wholeideas behind the symbol. The representati<strong>on</strong> of ideas then shifted intorepresentati<strong>on</strong>s of syllables am<strong>on</strong>g the Sumerians, Babyl<strong>on</strong>ians, Assyrians,Persians, Aztecs, Mayans, Chinese, Hittites, Egyptians, as well the Indiansystems of writing which greatly influenced South East Asian forms(MacNevin, 1993; Kaestle, 1988; Harris, 1986; Rahi, 1977; Carpenter,1973; Gelb, 1952; Diringer, 1948). Yet early in this history of literacy 16 ,knowledge of hieroglyphics or ic<strong>on</strong>ographs was something available <strong>on</strong>lyto scribal priests and the elite few with whom they shared this tool(MacNevin, 1993, pp. 12-15). As an example, the word ”hieroglyphics”refers in Greek to ”sacred or priestly carvings”, and it was believed thatthe <strong>on</strong>ly way to read the symbols was to have access to the mysticalknowledge of the priests. In spite of this seemingly limited access, it shouldnot be interpreted as a scribal scheme, as Lucas (1972) points out:The m<strong>on</strong>opolistic character of early schooling was not the c<strong>on</strong>sciousresult of a scribal c<strong>on</strong>spiracy to enlist educati<strong>on</strong> for the preservati<strong>on</strong> ofclass privilege. Rather, it was a natural outgrowth of many forces shapingSumerian, Babyl<strong>on</strong>ian, Assyrian and Egyptian life. Because these cultureswere extremely c<strong>on</strong>servative, absolutist, and sancti<strong>on</strong>ed by a highlyauthoritarian ideology, schools also assumed such characteristics. (p. 45)The fact that written knowledge was the property of a few andc<strong>on</strong>veyed to others through oral communicati<strong>on</strong>s is not indicative ofthe ”power” of writing in its technological ”growth,” but instead,22

indicative of the accepted power structures and the dominant modes ofcommunicati<strong>on</strong> in place at the time.The representati<strong>on</strong> of sound/syllables ultimately led to the ”inventi<strong>on</strong>”of alphabetic systems to represent more discrete sounds. The Greek alphabet,”invented” sometime around 650-550 B.C. (MacNevin, 1993;Kaestle, 1988; Graff, 1987; Havelock, 1971), added vowels to 17 andborrowed 19 letters from the (often forgotten) Phoenician alphabet,which was probably the first ”c<strong>on</strong>s<strong>on</strong>antal” alphabet (Rahi, 1977, p. 14& 16). However, as great as the Greek alphabet may have been as the”foundati<strong>on</strong>” to all European alphabets in use today (Diringer, 1948),its ”development” and spread had little to do with technological determinismor a ”natural” development in communicati<strong>on</strong> technologies,since ”[t]he script and the very principles of the alphabet were adoptedfrom the Ph<strong>on</strong>ecians of the Levantine coast, with whom Greeks werenow increasingly in c<strong>on</strong>tact” (Thomas, 1992, p. 53). In fact, the alphabetwas not viewed as an essential tool for the general Greek publicright away, as its uses were for commercial services in line with thePh<strong>on</strong>ecians (Thomas, 1992, p. 56), or for poetic purposes (Thomas,1992, p. 57), or ”restricted to a small elite and limited to a few functi<strong>on</strong>s,chiefly religi<strong>on</strong>” (Kaestle, 1988, p. 98). Yet even during this time ofGreek alphabetic expansi<strong>on</strong>, Thomas (1992) points out that ”most Greekliterature was meant to be heard or even sung - thus transmitted orally- and there was a str<strong>on</strong>g current of distaste for the written word evenam<strong>on</strong>g the highly literate: written documents were not c<strong>on</strong>sideredadequate proof by themselves in legal c<strong>on</strong>texts till the sec<strong>on</strong>d half of thefourth century BC” (p. 3).When the first schools in Greece were being formed between 500and 400 B.C., students learned to ”read” (or recite) by heart (Thomas,1992, p. 92) because the ability to memorize and orally recite oral poetryand great philosophical works was of greatest value at the time. As thetools of reading and writing became more wide-spread with the adventof Greek city-states, members of the society were taught to be literatefor specific political and civic functi<strong>on</strong>s such as ”moral c<strong>on</strong>duct, respectfor social order, and participant citizenship” (Graff, 1987, p. 28).Meanwhile, the Greek alphabet was being transferred to the Romansthrough an Etruscan influence (Diringer, 1948, p. 535), and the Latin23

potent: to be ”illiterate” is not to be n<strong>on</strong>human, n<strong>on</strong>intelligent oruncivilized 18 . If, throughout time, illiteracy has been variously equatedwith a savagery or a deficiency or a disease which stands in the way ofprogress, it has not been because these are ”natural” characteristics ofwhat it means to be ”illiterate.” Rather, the ever-shifting noti<strong>on</strong>s of”literacy” or ”illiteracy” are created and defined through mechanisms ofpower that do not exist outside of social and historical relati<strong>on</strong>s.Technological advancements are never merely introduced into a culture,whether or not that culture is primarily ”oral” or already highly ”literate.”Instead, there are specific cultural c<strong>on</strong>texts which always shapehow the technologies of ”literacy” are perceived and how (if at all) theywill fit into the established customs related to the producti<strong>on</strong> andcirculati<strong>on</strong> of thought. Just as the ”electr<strong>on</strong>ic age” (as we know it) dependsup<strong>on</strong> writing and print, the historically c<strong>on</strong>tingent technologies of the”literate” are dependent up<strong>on</strong> tremendously complex interrelati<strong>on</strong>sinvolving oral communicati<strong>on</strong>s.Seemingly ”progressive” shifts in the technologies of ”literacy” appearat moments when whole new technologies are ”invented,” like systemsof writing, or the alphabet, or the printing press, or e-mail. Some of theways in which people have been able to organize thought and knowledgemay not have been thinkable without writing or print or electr<strong>on</strong>icnote passing, and yet, the ways in which people have organized thoughtand knowledge have varied greatly over time even when the sametechnology (writing) was being used. For example, during a time whencultural dialects were seen as a threat to nati<strong>on</strong>al cohesi<strong>on</strong> (the end ofthe eighteenth century in the United States), instructi<strong>on</strong> in ”literacy”involved having students place their toes <strong>on</strong> straight lines (where thesaying, ”toe the line,” came from) while they stuck out and wiggledtheir t<strong>on</strong>gues (see Myers, 1996, pp. 64-65) 19 . This type of ”literacy” wasvalued because it included the appropriate pr<strong>on</strong>unciati<strong>on</strong> of writtenwords and phrases, whereas the kind of ”literacy” valued in another era(say right now) means that students work together in small groups tocompose daily news stories, during a time when businesses areencouraging ”cooperative teaming.” In additi<strong>on</strong>, the type of ”literate”knowledge involved in the development of electr<strong>on</strong>ic technologies wasvalued for its possibilities of better communicati<strong>on</strong> during the first World25

War. These variati<strong>on</strong>s in the values and uses of ”literacy” are notdependent up<strong>on</strong> what literacy ”is,” but instead <strong>on</strong> the demands of socialand historical circumstances. Changes in the meanings and uses of”literacy” shift according to transformati<strong>on</strong>s in the discursive practiceswhich delineate how knowledge is ”best” circulated, valorized, attributed,and appropriated 20 .Therefore, communicati<strong>on</strong> techniques do not merely develop in aprogressive successi<strong>on</strong> from worse to better, but instead, the ways inwhich human beings communicate vary over time due to struggles overpurpose/pedagogies/procedures. This is not a matter of right and wr<strong>on</strong>g,but a matter of history and power. While it is bey<strong>on</strong>d the scope of thispaper to debate whether or not ”advancements” in communicati<strong>on</strong>techniques could have happened (or been ”discovered”) without readingand writing, it is clear that ”literacy,” by itself, did not progressively”develop” <strong>on</strong> its own in a technologically determined dance. This isbecause ”literacy” can not exist ”by itself” outside of cultural and historicalrelati<strong>on</strong>s of power. The ”necessity” of reading and writing fortechnological ”progress” is <strong>on</strong>ly as ”necessary” as cultural and historicalcircumstances will allow.Assumpti<strong>on</strong> Number Three: Literacyand Educati<strong>on</strong>al Understandings of Text, Author, ReaderThe definiti<strong>on</strong> of ”text” entails the printed word. ”Texts” aresomething from which to extract the author’s meaning, and while areader’s interpretati<strong>on</strong> is certainly an interest of educati<strong>on</strong>, there is adivisi<strong>on</strong> between what is actually said, or ”given,” in the text, andthe possible interpretati<strong>on</strong>s a reader can make of it. Educati<strong>on</strong>ally,therefore, we have the resp<strong>on</strong>sibility to teach children how to getmeaning from a text by reading, and how to put meaning into atext by writing. There are particular educati<strong>on</strong>al devices andmaterials regarding the instructi<strong>on</strong> of reading and writing that areessential for <strong>teacher</strong>s to teach and students to learn. Electr<strong>on</strong>ictechnologies would not have come about without literacy; however,many forms of electr<strong>on</strong>ic technologies have nothing to do with26

literacy per se. In fact, ”e-literacies” which deal with n<strong>on</strong>-print(televisi<strong>on</strong>, mass media, hypermedia, virtual reality) may be posinga serious threat to the future of literate cultures and literacy itself.”Text” is <strong>on</strong>e of those c<strong>on</strong>cepts that didn’t exist before writing and print.However, like any c<strong>on</strong>cept, its definiti<strong>on</strong> is subject to change over timeand within particular c<strong>on</strong>texts of thinkability. For example, in certainc<strong>on</strong>texts ”text” has been expanded to include more than the printedword. When ”literates” began to analyze ”oral” cultures, both past andpresent, a re-defined ”text” which has nothing to do with the printedword became usable and thinkable as a way to validate oral culturaltraditi<strong>on</strong>s and producti<strong>on</strong>s. While ”oral text” may seem (to some) likean oxymor<strong>on</strong>, to others, it has stood as a useful way to compare andanalyze language structures and patterns of thought circulati<strong>on</strong>. In additi<strong>on</strong>,and quite recently, the meaning of ”text” is beginning to undergoa wider change in educati<strong>on</strong>al fields, as dem<strong>on</strong>strated by the newlyreleased Standards for the English Language Arts (NCTE & IRA, 1996).In it, text ”refer[s] not <strong>on</strong>ly to printed texts, but also to spoken language,graphics, and technological communicati<strong>on</strong>s”; language ”encompassesvisual communicati<strong>on</strong> in additi<strong>on</strong> to spoken and written forms ofexpressi<strong>on</strong>”; and reading ”refers to listening and viewing in additi<strong>on</strong> toprint-oriented reading.” However, U.S. Nati<strong>on</strong>al Standards or not, thisnew meaning of ”text” is not comm<strong>on</strong>place in U.S. classrooms.Educati<strong>on</strong>ally, ”text” still refers to, for the most part, that which isprinted: text where the author is still in c<strong>on</strong>trol of meaning, text that isnecessarily linear in its flow from beginning to end, text where the reader’srole is to decipher (and possibly use) the meaning. Assessment of astudent’s reading ability revolves around the general comprehensi<strong>on</strong> ofthe author’s meaning, or the particular knowledge of word recogniti<strong>on</strong>and decoding skills used to ”get” meaning from the text.Meanwhile, wider meanings of ”text” which have been talked aboutby thinkers such as Bakhtin 21 , Barthes 22 , Derrida 23 , and Foucault 24 , andwhich are gaining momentum in scholarly circles and technologicalcircuits, have not yet made it to public school classrooms either. Theremay be a reas<strong>on</strong> why: the prospects might look just plain silly in theclassrooms we know and aloofly like. This is, after all, the here-and-27

now, completely equipped with the inertias of the that-which-isthinkable-just-now.It doesn’t fit into the standard curriculum to requirethat students analyze their own interpretati<strong>on</strong>s in terms of a network ofc<strong>on</strong>tingencies, as the theorists menti<strong>on</strong>ed above might advise. The<strong>teacher</strong>-as-lecturer-using-the-English-of-yesteryear doesn’t lend herselfwell to a c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> of the plurality of texts formed at the intersecti<strong>on</strong>of several c<strong>on</strong>sciousnesses. The materials available - the things that wecall ”texts” - do not come embedded in auditory and visual communicati<strong>on</strong>experiences, at least not in class sizes of thirty.The comm<strong>on</strong> understandings of text, author, and reader are based inpart <strong>on</strong> the structures of language in print. There is a given (or fixed)meaning to be discovered in the text, someplace between the beginningand the end; there is the need for the antecedents of c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s to lineup in a coherent order determined by the established customs of”appropriate” reas<strong>on</strong>ing. What is said and the way it is said still need toc<strong>on</strong>form to the c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>s of language in print, which is to say languagec<strong>on</strong>tained within a definitive piece, the word <strong>on</strong> the page, the author incharge. When the author is in charge, the author’s meaning is central tointerpretati<strong>on</strong>. A reader’s interpretati<strong>on</strong> is in jeopardy of being ”wr<strong>on</strong>g”when it departs the ”grounded” text because many of the words <strong>on</strong> thepage still have particular references which do not permit completely freeinterpretati<strong>on</strong>. It is a chicken that crossed the road, for example, not a cowor a goat. Text is understood as a fairly aut<strong>on</strong>omous entity in this viewbecause it holds a distinct meaning (the author’s) for the reader to ”get.”Yet ”text” has not always been so independent, as evidenced in ancientGreek documents which left a lot unsaid, relying instead <strong>on</strong> the rememberedand presupposed knowledge of the reader (Thomas, 1992, p. 76). And”text” may not always be thought of in its linear, self-c<strong>on</strong>tained, and printedsense, with the types of ”texts” available through electr<strong>on</strong>ic communicati<strong>on</strong>s,such as hypertext or virtual reality 25 . The point is that fluctuati<strong>on</strong>s in thecomm<strong>on</strong>ly understood definiti<strong>on</strong>s of text, author, or reader are related tofluctuati<strong>on</strong>s in discursive practices, transformati<strong>on</strong>s which are linked tolarger shifts in understandings that extend bey<strong>on</strong>d any new definiti<strong>on</strong>s of”text” or any new definiti<strong>on</strong>s of what literacy ”is.” Myers (1996) asks:Why does a society decide to change its mind about its literacypractices? Societies do not develop something called intelligence or28

English teaching and then invent new standards of literacy from thepossibilities of that intelligence or English teaching. Instead, a standardof literacy - or what we call a skill - is the result of an interacti<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>gsuch variables as urbanizati<strong>on</strong> (Lerner 1958), the political interacti<strong>on</strong>sof Protestantism and capitalism (Tyack 1974), the religious beliefs ofCalvinism (Lockridge 1974), secularism (Clanchy 1979), technologylike the printing press (Eisenstein 1979), mass media (Schramm andRuggels 1967), fertility rates (Vinovskis 1981), and a failing and/orgrowing ec<strong>on</strong>omy (Reich 1992). (Myers, 1996, p. 5)However, all of these ”variables” that help to define a standard ofliteracy can also be described as manifestati<strong>on</strong>s of the discursive practicesof the time. If a society thinks it has ”decide[d] to change its mindabout its literacy practices,” it is not without relati<strong>on</strong>s of power alreadyestablished in discursive practices which c<strong>on</strong>stitute taken-for-granteddiscourses of truth 26 . Any changes in the definiti<strong>on</strong> of ”literacy” andany corresp<strong>on</strong>ding instituti<strong>on</strong>al changes in pedagogy do not occur assimply as a ”change in the mind” might imply.The comp<strong>on</strong>ents that help to define a standard of ”literacy” need tobe invested with relevance before whole systems of thought can be shifted,while the noti<strong>on</strong> of ”relevance” is tied not to fertility rates, nor to thepolitical interacti<strong>on</strong>s between Protestantism and capitalism, but rather,and more c<strong>on</strong>sistently, to the discursive practices of the time. This isnot to say that factors such as fertility rates, politics, religious beliefs, orthe printing press have nothing to do with changes in the definiti<strong>on</strong> of”literacy,” but rather, it is to say that factors which are seen as importantin the transformati<strong>on</strong> of ”literacy” are <strong>on</strong>ly valued as c<strong>on</strong>sequentialthrough discursive practices that validate particular perspectives anddisregard others.If the comm<strong>on</strong>ly understood meaning of ”text” expands to includesuch ideas as ”intertextuality,” ”multivocality,” or the ”de-centering” ofa singular author (see, for example, Landow, 1992, pp. 10-13), thisshift will not occur without transformati<strong>on</strong>s in the discursive practicesthat set forth appropriate modes of thought circulati<strong>on</strong>, valorizati<strong>on</strong>,attributi<strong>on</strong>, and appropriati<strong>on</strong>. If the definiti<strong>on</strong> of ”literacy” is currentlyin a state of transiti<strong>on</strong> to include the negotiati<strong>on</strong> of multiple perspectivesand the interpretati<strong>on</strong> of various texts, the factors of importance may29

e a growth in informati<strong>on</strong>al services coupled with wider internati<strong>on</strong>alrelati<strong>on</strong>s 27 . The discursive practices surrounding the tools of ”literacy”(electr<strong>on</strong>ic or otherwise) establish understandings of what text ”is,” whichtexts are more valuable, who has the authority to decide, and what we’resupposed to do with the text in order to be called ”literate,” if we’recalled ”literate” at all. In other words, what it could mean to be ”literate”within the framework of a broadened definiti<strong>on</strong> of ”text” will bedependent up<strong>on</strong> the ”accepted” and valued producti<strong>on</strong>s of a culture,what those producti<strong>on</strong>s require of the ”literate,” and whether thoseproducti<strong>on</strong>s incorporate the wide-spread use of the materials whichenlarge the meaning of text.In the ”electr<strong>on</strong>ic age,” with teleph<strong>on</strong>es, televisi<strong>on</strong>s, movies, filmstrips,hypermedia, and virtual reality (for example), we are living in anage of ”sec<strong>on</strong>dary orality” which depends up<strong>on</strong> writing and print for itsexistence (see Ong, 1982, p. 3). This can mean anything from the factthat oral televisi<strong>on</strong> scripts are written down to the fact that writing wasnecessary for the inventi<strong>on</strong> of the teleph<strong>on</strong>e, <strong>on</strong> which we communicateorally. The use of many of these electr<strong>on</strong>ic communicati<strong>on</strong> devices (televisi<strong>on</strong>,teleph<strong>on</strong>e, radio) is indeed wide-spread. However, the”sec<strong>on</strong>dary” porti<strong>on</strong> of televisi<strong>on</strong>s and teleph<strong>on</strong>es and hypermedia andvirtual reality can also mean that the acts of using these technologieshave little to do with ”literacy” as we understand it today, if we understandit to mean reading or writing a printed text. If writing and print arenot always immediately apparent in the stylistic communicati<strong>on</strong> ofthoughts through sound, the comm<strong>on</strong> understandings of the day maynot be apt to place these acti<strong>on</strong>s within the realm of ”literate”communicati<strong>on</strong>. When n<strong>on</strong>-print electr<strong>on</strong>ic technologies are viewed asn<strong>on</strong>-literate, they are put in a positi<strong>on</strong> outside of ”true” educati<strong>on</strong>alvalue. They are seen as dem<strong>on</strong>strati<strong>on</strong>al extras, appreciated for theirentertainment value, but it’s time to get back to work, boys and girls.Because the factors which change definiti<strong>on</strong>s and tools of ”literacy”do not exist outside of temporarily static definiti<strong>on</strong>s of what counts asimportant, what counts as truth, what counts as valuable knowledge,we are not in the positi<strong>on</strong> to know whether or not communicatingthrough electr<strong>on</strong>ic (including n<strong>on</strong>-print) means will be a focus of”literacy” educati<strong>on</strong>. We are not in the positi<strong>on</strong> to know where things30

may go or what will be the end, since we are not in the positi<strong>on</strong> to maketruth and knowledge ”up.” However, through the active disrupti<strong>on</strong> ofcomm<strong>on</strong> assumpti<strong>on</strong>s surrounding ”literacy,” we could potentially bein a positi<strong>on</strong> to see that there are alternate possibilities.Alternate PossibilitiesIf you are reading this with the technologies of a late twentieth centuryWestern ”literate” 28 , your percepti<strong>on</strong>s of this paper are driven in part byan attempt to tweeze out some kind of knowledge from a text you maynever have seen before; you are silently analyzing its parts, its selfc<strong>on</strong>tainedstructure, its syntax, its semantics, as your unvoiced innervoicegoes about decoding its meaning; you have objectified it in such away that the intelligent producti<strong>on</strong>s transpiring in your mind areoccurring <strong>on</strong> a completely individualized level; you may even have somewell-tuned academic skills for recording or storing any informati<strong>on</strong> thatyour thoughts have brought about.Yet, this has not always been the way that people have ”read” a text.What it means to read, and to read well, as history has shown, iscompletely dependent <strong>on</strong> a culture and a time, if it’s even an issue ofimportance at all. People and cultures, in other words, do not devise ameaning for ”literacy” and then simply ”do” it. The discursive practicesof the time determine what <strong>on</strong>e is to ”do” when <strong>on</strong>e is ”being literate,”and this in turn determines the range of possible interpretati<strong>on</strong>s andpercepti<strong>on</strong>s of whatever is being ”read.”This having been said, the discursive practices of our time may bechanging in such a way that we can imagine a form of ”literacy” whichincludes more than accepting the ”text” as a fixed or given word, morethan accepting writing and print as the superior mode of knowledgecirculati<strong>on</strong>, more than accepting the authority of the author. For example,with electr<strong>on</strong>ic communicati<strong>on</strong>s, we can begin to imagine howpercepti<strong>on</strong>s of ”text” and ”authorship” and ”readership” may be different.When we are able to think of ”text” differently, of ”readership” and”authorship” differently, then the possibilities for the types of knowledgeswhich are valued begin to look different too. Landow (1993) exploresthis line of thinking in relati<strong>on</strong> to an altered understanding of ”text”:31

One tends to think of text from within the positi<strong>on</strong> of the lexia underc<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>. Accustomed to reading pages of print <strong>on</strong> paper, <strong>on</strong>e tendsto c<strong>on</strong>ceive of text from the vantage point of the reader experiencingthat page or passage, and that porti<strong>on</strong> of text assumes a centrality.Hypertext, however, makes such assumpti<strong>on</strong>s of centrality fundamentallyproblematic. . . . Hypertext similarly emphasizes that the marginal hasas much to offer as does the central, in part because hypertext does not<strong>on</strong>ly redefine the central by refusing to grant centrality to anything, toany lexia, for more than the time a gaze rests up<strong>on</strong> it. In hypertext,centrality, like beauty and relevance, resides in the mind of the beholder.(pp. 69-70)In additi<strong>on</strong>, the roles of ”author” and ”reader” in many forms ofelectr<strong>on</strong>ic communicati<strong>on</strong>s are fundamentally rec<strong>on</strong>figured. Withhypertextual c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong>s, ”authorial” c<strong>on</strong>trol is shifted a degree ortwo to the reader, who gets ”to choose his or her way through themetatext, to annotate text written by others, and to create links betweendocuments written by others” (Landow, 1993, p. 71). In <strong>on</strong>-line multimediaexperiences, readers are not c<strong>on</strong>fined to a limited realm of informati<strong>on</strong>such as found in books or <strong>on</strong> hypertextual CD-ROMS, butinstead, the reader can move in an array of visual images and sound,text and n<strong>on</strong>-text, choosing between generalities and specifics presentedby numerous authors and artists. As another example, the c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong>swhich take place through written <strong>on</strong>-line c<strong>on</strong>ferencing, such as experiencedthrough Multiple-User Dimensi<strong>on</strong>s (MUDs) or MOOs (MUD ObjectOriented), occur in real time and <strong>on</strong> the highly present terrain of thecomputer screen, a place that seems ”real” as the c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong> is occurring.The lines between author and reader are transparent here since <strong>on</strong>e cantake <strong>on</strong> both identities as the c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong>, or ”text,” transpires accordingto group interacti<strong>on</strong>, not a singular authority. In additi<strong>on</strong>, digitaltechnologies allow for audiences of <strong>on</strong>e, where the ”reader” can order upextremely pers<strong>on</strong>alized informati<strong>on</strong> (see, for example, Negrop<strong>on</strong>te, 1995);and virtual reality programs make the distincti<strong>on</strong> between author and readerinvisible as the ”reader” (who may not have a written text anywherenearby) ”writes” the acti<strong>on</strong>s and progressi<strong>on</strong>s of the experienced ”text.”When the minds of the literates are informed by discursive practicesthat allow for rec<strong>on</strong>figured versi<strong>on</strong>s of text, author, and reader, there are32

a variety of possible ways to perceive the act of ”being literate.” A relatedset of assumpti<strong>on</strong>s emerges. For example, to negotiate within this understandingof text could require a kind of c<strong>on</strong>fidence and a sense of self,coupled with an ability to take risks (see Myers, 1996, chapter 8). Sincethe uses of ”literacy” in the electr<strong>on</strong>ic circulati<strong>on</strong> and producti<strong>on</strong> ofknowledge are perceived (at this point in time) to be self-m<strong>on</strong>itoredand self-determined, it is possible that the ”literate subject” may beassumed to be an aut<strong>on</strong>omous agent of knowledge producti<strong>on</strong>. This”literate subject” would be <strong>on</strong>e who lives in the intertextuality of languageand interpretati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>on</strong>e who is c<strong>on</strong>fr<strong>on</strong>ted by various paths or ”choices”in the producti<strong>on</strong> of knowledge (see, for example, Landow, 1992; Bolter,1991).In line with the assumpti<strong>on</strong> that ”literacy” is a form of ”power,” this”e-literate” subject might be imagined to have a type of individual”power” in choosing ”self-determined” paths of learning and textualexplorati<strong>on</strong> 33 . When the educati<strong>on</strong>al possibilities of a ”literacy” definedin electr<strong>on</strong>ic circumstances include the c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> of a subject who isassumed to be ”aut<strong>on</strong>omous” with electr<strong>on</strong>ic media, the ”e-literate”subject may also take the form of an ”individual” who is not <strong>on</strong>ly ”selfdetermined,”but also ”self-aware” of his or her own role in the creati<strong>on</strong>of meaning. This subject could possibly be skillful at interrogatingreceived representati<strong>on</strong>s, able to read symptomatically 34 in an increasinglyglobal field, and capable of analyzing positi<strong>on</strong>s and interpretati<strong>on</strong>sthrough the critique of accepted histories.Lest this seems too speculative in the inertias and c<strong>on</strong>straints of thepresent time, these possibilities for ”e-literacies” are not too far off fromwhat the Standards for the English Language Arts (1996) are proposing.Although the use of electr<strong>on</strong>ic communicati<strong>on</strong>s is not necessary for thisversi<strong>on</strong> of ”literacy,” which Myers (1996) calls ”translati<strong>on</strong> literacy,” itstill involves the ”[i]nterpretati<strong>on</strong> of many texts, producing multipletranslati<strong>on</strong>s of many different kinds of texts in many sign systems” (p.57). In numerous classrooms all over the United States 35 , <strong>teacher</strong>s arealready preparing students to find their ways <strong>on</strong> their own, to be risktakersand metacognitive thinkers, to questi<strong>on</strong> themselves at every point,by asking students to keep (for example) journals of the problems andhighlights they encounter while reading, or by encouraging students to33

guess and struggle and try various reading strategies when coming acrossunknown words, or by having students negotiate mathematics textsthrough trial and error. The perceived power of a self-sufficient thinkerand the perceived necessity for comfort in ambiguity and uncertainty asa way of learning to take risks are already an everyday part of manystudents’ schooling. Perhaps we are not thinking about it in terms of ”eliteracy,”which just goes to show that the technology is not determiningwhat we do with it, but if and when ”e-literacies” are perceived to benecessary in comm<strong>on</strong> educati<strong>on</strong>al understanding, then the ”e-literate”subject will already be waiting. This is because ways of thinking aboutand defining the ”literate subject” (”e” or otherwise) do not ”enter”society <strong>on</strong> vacant grounds.Where previously unthinkable, it is now possible (because of the historicalc<strong>on</strong>texts of thinkability, not because of some progressive history)to c<strong>on</strong>sider and play with the idea that spoken and visual expressi<strong>on</strong>scan be within the realm of ”text.” Moreover, it is possible to think of”text” as a c<strong>on</strong>glomerati<strong>on</strong> of ideas, a c<strong>on</strong>glomerati<strong>on</strong> of beginningsand middles and ends, which are interwoven in a web of historicallyc<strong>on</strong>structed thought. It is possible to think of numerous entrances toand exits from this text, where c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s to a myriad of possibledirecti<strong>on</strong>s open up assorted lines of argumentati<strong>on</strong> and investigativestudy. It is possible to think of ”readings” as filtered through numerousand disparate historically c<strong>on</strong>textualized moments of interpretati<strong>on</strong>,where no reader is a deserted recluse <strong>on</strong> an isolated author’s island.Indeed, the words and/or ideas may unfold <strong>on</strong> the page or the screen orthe Virtual Boy strapped to your head in a pattern that resembles resoluti<strong>on</strong>,but it is now possible to understand their meaning as dependentup<strong>on</strong> various, perhaps unforeseen, social and historical c<strong>on</strong>texts.Irresolute. There is no beginning, middle, and end to a ”text” that isrec<strong>on</strong>figured to include a plurality that goes bey<strong>on</strong>d the writer’s ”exact”meaning, as the illusi<strong>on</strong>s of narrative structure, grammar, and logic arereplaced by the infinity of language and its infinite c<strong>on</strong>notati<strong>on</strong>s.Less reverence for print; no beginning, no middle, no end; lessauthority for the author; no natural evoluti<strong>on</strong>s. Yet let’s not forget thatliteracies will always be embedded in discursive practices and presumedassumpti<strong>on</strong>s. These alternate possibilities are <strong>on</strong>ly as alternative as34

imaginati<strong>on</strong> will allow. ”Possibilities” do not reveal themselves indereistic 32 vacuums someplace outside of time. It must be rememberedthat the ”literate subject” is always a social and historical c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>defined by social and historical c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>s. This is because whateverwe ”do” (or d<strong>on</strong>’t do or can’t do or w<strong>on</strong>’t do) is based up<strong>on</strong> the discursivepractices embedded in our everyday understandings of the world inwhich we live: our understandings of the ordinary operati<strong>on</strong>s of thatworld, our percepti<strong>on</strong>s of the chances and opportunities we see forchanging that world, the daily possibilities of what we think we aresupposed to do in that world, how we see that very world itself. Anytheories or hopes for possibilities (in educati<strong>on</strong>, in life) are interwovenwith the ”reality” of local and social experiences, which in turn areinterwoven with larger historical movements in the history of thoughtitself: what is thinkable in a given time and place, and for what historicallyc<strong>on</strong>tingent purposes.It is important to remember that the possibilities of significance forthe future have not yet been outlined. But there may be allusive forms:the possibilities involved in multi-level interpretati<strong>on</strong>, or the possibilitiesinvolved in displacing the center by clicking <strong>on</strong> the margins, or thepossibilities of creating new centralities through explorati<strong>on</strong>s inintertextuality, or the possibilities of interrogating representati<strong>on</strong>s fromthe standpoint of unheard voices. Each historical c<strong>on</strong>text yields roomfor <strong>on</strong>ly certain possibilities to flourish and expand, as each representati<strong>on</strong>of ”literate behavior” survives for particular social and historicalreas<strong>on</strong>s. Infused with power, possible meanings of ”literacy” take shape,and these meanings have a life and a future, a basis for furtherinterpretati<strong>on</strong>s and additi<strong>on</strong>al possibilities, <strong>on</strong>ly when the accepted rulesof understanding, <strong>on</strong>ce again tied to the moment, are fulfilled. Limitedand limiting, the accepted rules of understanding are the assumpti<strong>on</strong>sof the time, which regulate the possibilities of significance. These arethe assumpti<strong>on</strong>s to be disrupted.35

Notes1. As a method of reading history, genealogies situate the discursive practices which areendemic to historically standard assumpti<strong>on</strong>s, analyzing how those assumpti<strong>on</strong>s regulateacti<strong>on</strong>s and opti<strong>on</strong>s. Foucault (1977a) defines discursive practices in this way:Discursive practices are characterized by the delimitati<strong>on</strong> of a field of objects, the definiti<strong>on</strong>of a legitimate perspective for the agent of knowledge, and the fixing of norms forthe elaborati<strong>on</strong> of c<strong>on</strong>cepts and theories. Thus, each discursive practice implies a play ofprescripti<strong>on</strong>s that designate its exclusi<strong>on</strong>s and choices. (p. 199)For example, and in relati<strong>on</strong> to historical meanings of ”literacy,” the technical processesrequired to be viewed as ”literate” are analyzed in terms of how they are defined andinstituti<strong>on</strong>alized in ordinary discourses regarding the perceived norms and appropriateways to ”be literate.” For my purposes, genealogy serves to dem<strong>on</strong>strate that the exclusi<strong>on</strong>sand choices made over time regarding the meanings of ”literacy” are not a part of ”progress,”but rather, historically situated indicati<strong>on</strong>s of power at work. This in turnproblematizes the educati<strong>on</strong>al discourses surrounding ”literacy” that we take as given,thereby exposing the power and limitati<strong>on</strong>s embedded in the discourses of our day.Foucault (1977a) distinguishes ”discourses” from ”discursive practices” by writing:Discursive practices are not purely and simply ways of producing discourse. They areembodied in technical processes, in instituti<strong>on</strong>s, in patterns for general behavior, in formsfor transmissi<strong>on</strong> and diffusi<strong>on</strong>, and in pedagogical forms which, at <strong>on</strong>ce, impose andmaintain them. (p. 200)With this in mind, I am tying historically specific ways of ”being literate” to theinstituti<strong>on</strong>alized patterns for general behavior, as knowledge about ”literacy” is transmittedthrough the pedagogy which informs the technical processes of what it means to ”beliterate”, or the technical aspects of what <strong>on</strong>e is supposed to ”do” when <strong>on</strong>e is ”beingliterate.” The variati<strong>on</strong>s throughout time in what it means to ”be literate” are dependentup<strong>on</strong> particular discursive practices that define the norms of ”legitimate” literate behavior.While these norms and legitimate ways of being are understood to change over time,Foucault (1977a) also writes that discursive practices ”possess specific modes of transformati<strong>on</strong>”(p. 200). He goes <strong>on</strong> to say:These transformati<strong>on</strong>s cannot be reduced to precise and individual discoveries; and yetwe cannot characterize them as a general change of mentality, collective attitudes, or astate of mind. The transformati<strong>on</strong> of a discursive practice is linked to a whole range ofusually complex modificati<strong>on</strong>s that can occur outside of its domain (in the forms ofproducti<strong>on</strong>, in social relati<strong>on</strong>ships, in political instituti<strong>on</strong>s), inside it (in its techniquesfor determining its object, in the adjustment and refinement of its c<strong>on</strong>cepts, in itsaccumulati<strong>on</strong> of facts), or to the side of it (in other discursive practices). (p. 200)Modificati<strong>on</strong>s and variati<strong>on</strong>s in discursive practices are dependent up<strong>on</strong>, am<strong>on</strong>g otherthings, shifts in the way that knowledge is circulated or produced, changes in the techniqueswhich allocate more or less value to certain forms of knowledge, alterati<strong>on</strong>s in the view ofwho or what may act as an authority or agent of knowledge, and transformati<strong>on</strong>s in thepurposes or uses of knowledge.36

2. Foucault’s noti<strong>on</strong> of genealogy is a method of reading history. It is nothing more nornothing less. It is different from a progressivist reading of history in that it neverassumes that history has c<strong>on</strong>tinually brought forth greater social stability, moreproductive development, or superior means of ec<strong>on</strong>omic growth. It resists the noti<strong>on</strong>that technological developments are, in and of themselves, the driving forces behindrec<strong>on</strong>stituted human thought. It is also different from ”critical” readings of history,which problematize modernist noti<strong>on</strong>s of progress by viewing history from a ”pers<strong>on</strong>al”or ”emancipatory” perspective, without necessarily tying the ”pers<strong>on</strong>al” and the”emancipatory” to historical moments of thinkability. In the ”critical” view, it is as ifthe individual is the instrument of social change, able to overcome the c<strong>on</strong>straints ofhistory, the restraints of a dominant culture, by employing a technique defined bythat very culture, by being ”literate,” for example.Genealogies, <strong>on</strong> the other hand, inform us that there is more to history than arecord of the milest<strong>on</strong>es of productive development, and more also to history than aseries of incidents performed by human beings who float unc<strong>on</strong>strained through historicalmoments. Genealogies, as explained by Foucault (1988a) are ”a form of historywhich can account for the c<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong> of knowledges, discourses, domains ofobjects etc., without having to make reference to a subject which is either transcendentalin relati<strong>on</strong> to the field of events or runs in its empty sameness throughout thecourse of history” (p. 117). Genealogy, then, is a method to critique the ”nature” ofwhat we have become with the hope of exposing that which appears ”natural” and”self-evident” as social and historical c<strong>on</strong>structs.Dean (1994), borrowing from Foucault and Nietzsche, sketches out these threeforms of intellectual approaches to history which I have briefly touched up<strong>on</strong> here.He calls the first a ”progressivist theory” which ”proposes a model of social progressthrough the teleology of reas<strong>on</strong>, technology, producti<strong>on</strong>, and so <strong>on</strong>” (p. 3). This theory”might be called ’high modernism’, and is exemplified by the narratives of theEnlightenment” (p. 3). The sec<strong>on</strong>d form is a ”critical theory” which ”offers a critiqueof modernist narratives in terms of the <strong>on</strong>e-sided, pathological, advance of technocraticor instrumental reas<strong>on</strong> they celebrate, in order to offer an alternative, higher versi<strong>on</strong>of rati<strong>on</strong>ality” (p. 3). This critical reading of history ”promise[s] emancipati<strong>on</strong> andsecular salvati<strong>on</strong>” (p. 3). In this paper, I am associating Dean’s third type of intellectualpractice with Foucault’s noti<strong>on</strong> of genealogy, in that this practice is a ”problematizing”<strong>on</strong>e. Dean writes that ”[t]his form of practice has the effect of the disturbance ofnarratives of both progress and rec<strong>on</strong>ciliati<strong>on</strong>, finding questi<strong>on</strong>s where others hadlocated answers” (p. 4). In additi<strong>on</strong> to associating this approach with Foucault’s (1977b)”effective history”, Dean also points out that ”if the widely used term ’postmodernism’is defined as the restive problematisati<strong>on</strong> of the given, I would be happy toregard this type of history as an exercise of postmodernity” (p. 4). I would be happy tofollow.3. For any<strong>on</strong>e interested in the work d<strong>on</strong>e by UNESCO over the past ten to fifteen yearsin the fields of literacy educati<strong>on</strong>, culture, and communicati<strong>on</strong>s, I have assembled anannotated bibliography that I would be happy to share. Feel free to drop me an e-lineany time: ddhammer@students.wisc.edu4. ”In the Phaedrus,” writes Langham, ”Plato has Socrates deliver what may be the earliest37