August 2012 - Journal of Threatened Taxa

August 2012 - Journal of Threatened Taxa

August 2012 - Journal of Threatened Taxa

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

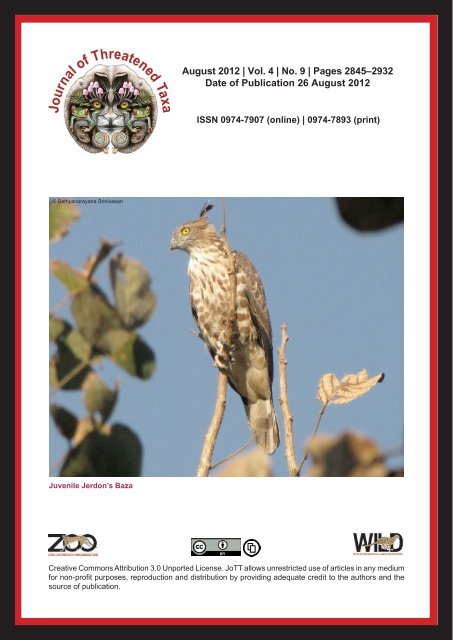

<strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | Vol. 4 | No. 9 | Pages 2845–2932Date <strong>of</strong> Publication 26 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print)© Sathyanarayana SrinivasanJuvenile Jerdon’s BazaCreative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. JoTT allows unrestricted use <strong>of</strong> articles in any mediumfor non-pr<strong>of</strong>it purposes, reproduction and distribution by providing adequate credit to the authors and thesource <strong>of</strong> publication.

Jo u r n a l o f Th r e a t e n e d Ta x aPublished byWildlife Information Liaison Development SocietyTypeset and printed atZoo Outreach Organisation96, Kumudham Nagar, Vilankurichi Road, Coimbatore 641035, Tamil Nadu, IndiaPh: +91422 2665298, 2665101, 2665450; Fax: +91422 2665472Email: threatenedtaxa@gmail.com, articlesubmission@threatenedtaxa.orgWebsite: www.threatenedtaxa.orgEDITORSFo u n d e r & Ch i e f Ed i t o rDr. Sanjay Molur, Coimbatore, IndiaMa n a g in g Ed i t o rMr. B. Ravichandran, Coimbatore, IndiaAs s o c ia t e Ed i t o r sDr. B.A. Daniel, Coimbatore, IndiaDr. Manju Siliwal, Dehra Dun, IndiaDr. Meena Venkataraman, Mumbai, IndiaMs. Priyanka Iyer, Coimbatore, IndiaEd i t o r ia l Ad v i s o r sMs. Sally Walker, Coimbatore, IndiaDr. Robert C. Lacy, Minnesota, USADr. Russel Mittermeier, Virginia, USADr. Thomas Husband, Rhode Island, USADr. Jacob V. Cheeran, Thrissur, IndiaPr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Mewa Singh, Mysuru, IndiaDr. Ulrich Streicher, Oudomsouk, LaosMr. Stephen D. Nash, Stony Brook, USADr. Fred Pluthero, Toronto, CanadaDr. Martin Fisher, Cambridge, UKDr. Ulf Gärdenfors, Uppsala, SwedenDr. John Fellowes, Hong KongDr. Philip S. Miller, Minnesota, USAPr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Mirco Solé, BrazilEd i t o r ia l Bo a r d / Su b j e c t Ed i t o r sDr. M. Zornitza Aguilar, EcuadorPr<strong>of</strong>. Wasim Ahmad, Aligarh, IndiaDr. Sanit Aksornkoae, Bangkok, Thailand.Dr. Giovanni Amori, Rome, ItalyDr. István Andrássy, Budapest, HungaryDr. Deepak Apte, Mumbai, IndiaDr. M. Arunachalam, Alwarkurichi, IndiaDr. Aziz Aslan, Antalya, TurkeyDr. A.K. Asthana, Lucknow, IndiaPr<strong>of</strong>. R.K. Avasthi, Rohtak, IndiaDr. N.P. Balakrishnan, Coimbatore, IndiaDr. Hari Balasubramanian, Arlington, USADr. Maan Barua, Oxford OX , UKDr. Aaron M. Bauer, Villanova, USADr. Gopalakrishna K. Bhat, Udupi, IndiaDr. S. Bhupathy, Coimbatore, IndiaDr. Anwar L. Bilgrami, New Jersey, USADr. Renee M. Borges, Bengaluru, IndiaDr. Gill Braulik, Fife, UKDr. Prem B. Budha, Kathmandu, NepalMr. Ashok Captain, Pune, IndiaDr. Cle<strong>of</strong>as R. Cervancia, Laguna , PhilippinesDr. Apurba Chakraborty, Guwahati, IndiaDr. Kailash Chandra, Jabalpur, IndiaDr. Anwaruddin Choudhury, Guwahati, IndiaDr. Richard Thomas Corlett, SingaporeDr. Gabor Csorba, Budapest, HungaryDr. Paula E. Cushing, Denver, USADr. Neelesh Naresh Dahanukar, Pune, IndiaDr. R.J. Ranjit Daniels, Chennai, IndiaDr. A.K. Das, Kolkata, IndiaDr. Indraneil Das, Sarawak, MalaysiaDr. Rema Devi, Chennai, IndiaDr. Nishith Dharaiya, Patan, IndiaDr. Ansie Dippenaar-Schoeman, Queenswood, SouthAfricaDr. William Dundon, Legnaro, ItalyDr. Gregory D. Edgecombe, London, UKDr. J.L. Ellis, Bengaluru, IndiaDr. Susie Ellis, Florida, USADr. Zdenek Faltynek Fric, Czech RepublicDr. Carl Ferraris, NE Couch St., PortlandDr. R. Ganesan, Bengaluru, IndiaDr. Hemant Ghate, Pune, IndiaDr. Dipankar Ghose, New Delhi, IndiaDr. Gary A.P. Gibson, Ontario, USADr. M. Gobi, Madurai, IndiaDr. Stephan Gollasch, Hamburg, GermanyDr. Michael J.B. Green, Norwich, UKDr. K. Gunathilagaraj, Coimbatore, IndiaDr. K.V. Gururaja, Bengaluru, IndiaDr. Mark S. Harvey,Welshpool, AustraliaDr. Magdi S. A. El Hawagry, Giza, EgyptDr. Mohammad Hayat, Aligarh, IndiaPr<strong>of</strong>. Harold F. Heatwole, Raleigh, USADr. V.B. Hosagoudar, Thiruvananthapuram, IndiaPr<strong>of</strong>. Fritz Huchermeyer, Onderstepoort, South AfricaDr. V. Irudayaraj, Tirunelveli, IndiaDr. Rajah Jayapal, Bengaluru, IndiaDr. Weihong Ji, Auckland, New ZealandPr<strong>of</strong>. R. Jindal, Chandigarh, IndiaDr. Pierre Jolivet, Bd Soult, FranceDr. Rajiv S. Kalsi, Haryana, IndiaDr. Rahul Kaul, Noida,IndiaDr. Werner Kaumanns, Eschenweg, GermanyDr. Paul Pearce-Kelly, Regent’s Park, UKDr. P.B. Khare, Lucknow, IndiaDr. Vinod Khanna, Dehra Dun, IndiaDr. Cecilia Kierulff, São Paulo, BrazilDr. Ignacy Kitowski, Lublin, Polandcontinued on the back inside cover

JoTT Ed i t o r i a l 4(9): 2845–2848Scientific conduct and misconduct: honesty is still thebest policyNeelesh Dahanukar 1,2 & Sanjay Molur 2,31Indian Institute <strong>of</strong> Science Education and Research (IISER), First floor, Central Tower, Sai Trinity Building, Garware Circle,Sutarwadi, Pashan, Pune, Maharashtra 411021, India2Zoo Outreach Organization, 3 Founder & Chief Editor, <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong>, 96 Kumudham Nagar, Villankurichi Road,Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, IndiaEmail: 1 n.dahanukar@iiserpune.ac.in, 2 herpinvert@gmail.comPublication <strong>of</strong> scientific research is a cooperativesystem where manuscripts are received by journalsin good faith that scientific integrity is maintained byauthors while performing research and writing articles.This faith is also bi-directional as authors expect thatthe editorial and reviewing processes are confidential,that the ideas expressed by authors are not misused andthat the judgment is fair. Since the dawn <strong>of</strong> scientificcommunications, both publishers and authors haveabided by this unwritten agreement to further scientificprogress. However, like any other cooperative system,even scientific publication is vulnerable to defection byeither parties leading to scientific misconducts, whichnot only leads to controversies, but also shakes thefoundation <strong>of</strong> this cooperative institution.Scientific misconduct has become a serious concernin recent years with exposure <strong>of</strong> several high pr<strong>of</strong>ilecases (for details see Montgomerie & Birkhead 2005;Triggle & Triggle 2007; Errami & Garner 2008; Redman& Merz 2008; Rathod 2010). As a result <strong>of</strong> theseexposures and in the interest <strong>of</strong> maintaining scientificintegrity many journals have now formalized theirpolicies against scientific misconduct (for example seeAronson 2007; Mukunda & Joshi 2008; Handa 2008;Editorial 2011), while European Science Foundationand ALLEA (All European Academies) have publisheda code <strong>of</strong> conduct for research integrity (Anonymous2011). With recent research on the nature <strong>of</strong> scientificmisconduct, its social effects and the journal’s standagainst the same (Martinson et al. 2005; Errami et al.Date <strong>of</strong> publication (online): 26 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>Date <strong>of</strong> publication (print): 26 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print)Citation: Dahanukar, N. & S. Molur (<strong>2012</strong>). Scientific conduct andmisconduct: honesty is still the best policy . <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong>4(9): 2845–2848.OPEN ACCESS | FREE DOWNLOAD2008; Fanelli 2009; Long et al. 2009; Resnik et al.2009) it is now becoming clear that journal policiesregarding scientific misconduct, which hitherto wereonly implied, should be put more explicitly in the form<strong>of</strong> a formal document.In a recent issue <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong>(JoTT) (Vol. 4, No. 7) an article authored by VirendraMathur, Yuvana Satya Priya, Harendra Kumar, MukeshKumar and Vadamalai Elangovan was found to be acase <strong>of</strong> duplication as a similar article was publishedby the authors elsewhere. The moment this case wasbrought to our attention, the article was withdrawnfrom JoTT online issue and appropriate disciplinaryactions were taken. This incident made us realize thata formal statement and description <strong>of</strong> the protocol fordefining JoTT policies against misconduct are essential.This editorial, therefore, tries to explain the concept<strong>of</strong> scientific misconduct and set the grounds for JoTTpolicies against scientific misconduct.Understanding what is scientific misconductBefore setting JoTT policies against scientificmisconduct, it is essential to define the idea <strong>of</strong> scientificmisconduct more objectively. Building upon thedifferent types <strong>of</strong> scientific misconducts identified byThe European Code <strong>of</strong> Conduct for Research Integrity(Anonymous 2011) and giving a special recognitionto duplicate publishing, we identify four types <strong>of</strong>scientifically unethical behaviors: (i) fabrication(creating a false data), (ii) falsification (manipulation<strong>of</strong> data), (iii) plagiarism (copying ideas, statements,results, etc. from other author/s without acknowledgingthe author/s and/or the source), and (iv) self-plagiarism(multiple identical publications with major overlap inideas, data, inferences, etc.).Based on different forms <strong>of</strong> scientifically unethicalbehaviors, for all practical purposes, we will follow<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2845–2848 2845

Scientific conduct and misconductand build up on the definition <strong>of</strong> scientific misconductprovided by Resnik (2003) who defines scientificmisconduct as follows:(1) Misconduct is a serious and intentional violation<strong>of</strong> accepted scientific practices, common sense ethicalnorms, or research regulations in proposing, designing,conducting, reviewing, or reporting research.(2) Punishable misconduct includes fabrication <strong>of</strong>data or experiments, falsification <strong>of</strong> data, plagiarism,or interference with a misconduct investigation orinquiry.(3) A person who commits a form <strong>of</strong> punishablemisconduct may receive a sanction proportional to theseriousness <strong>of</strong> the misconduct.(4) Misconduct does not include honest errors,differences <strong>of</strong> opinion, or ethically questionableresearch practices.JoTT policies against scientific misconductJoTT will not tolerate any form <strong>of</strong> scientificmisconduct and all allegations <strong>of</strong> such nature willbe evaluated objectively. JoTT will also not take thedecision hastily and all allegations will be reviewedthoroughly before making the final verdict. In any kind<strong>of</strong> allegation JoTT will follow the protocol provided inBox 1.Fabrication (false data) and falsification(manipulation <strong>of</strong> data) are severe crimes and JoTT’srigorous peer-review and editorial process will detectsuch a fraud. Even if some erroneous data may escapeN. Dahanukar & S. Molurthe reviewing process and get published, we believe thatfuture research will expose such faulty data and undersuch cases JoTT can request authors <strong>of</strong> the accusedpublication to provide raw data used for analysis, andwill take appropriate disciplinary actions against theaccused publication (Box 1). However, another majorconcern is plagiarism, which, fortunately, has becomerelatively easy to detect with the advent <strong>of</strong> internet andonline databases. It is essential that authors understandthe concept <strong>of</strong> plagiarism properly and understand itsseverity to avoid any allegations based on the same.Plagiarism is copying <strong>of</strong> ideas, statements, results,data, figures, etc. from other author(s) withoutacknowledging the original source, either publishedor unpublished, which may at times include copyrightinfringement (Amstrong 1993). Plagiarism is ethicallywrong because authors try to take credit <strong>of</strong> ideasstolen from other sources. Self-plagiarism is a form<strong>of</strong> plagiarism where authors express same ideas, data,representations, etc. in multiple publications withoutacknowledging the original publication. While, at aglance, self-plagiarism does not appear as unethicalstealing <strong>of</strong> credits, it is still an inappropriate behavioras it leads to multiple duplicate publications and mayalso contribute to copyright infringement. Copyrightinfringement is a severe crime especially if the authorshave transferred the copyright <strong>of</strong> their article to thepublisher. This issue does not always arise, especiallywhen the publication is licensed under “CreativeCommons Attribution 3.0 Unported License”, likeBox 1: JoTT policies against scientific misconductAny form <strong>of</strong> scientific misconduct is unacceptable and JoTT reserves the right to expose such work with appropriate level <strong>of</strong> penaltysuitable for the situation.A. In the case <strong>of</strong> suspected scientific misconduct, JoTT will follow the protocol given below:1. The submitted manuscript will be investigated objectively by the chief editor, associate editors and subject editors <strong>of</strong> JoTTand JoTT will take appropriate actions suitable for the crime.2. If scientific misconduct is detected during the reviewing or editing process, JoTT will (i) reject the manuscript, (ii) inform therespective heads <strong>of</strong> institutions <strong>of</strong> all the authors, and (iii) inform the funding agency(s) about the misconduct.3. If in doubt <strong>of</strong> fabrication or falsification, JoTT can ask for raw data, analysis, photographs, genomic sequences, gel pictures,etc. used by the authors.B. In case scientific misconduct is reported/detected in a published paper, JoTT will take appropriate actions in the followingorder:1. The subject editor and/or reviewers <strong>of</strong> the paper will be asked to comment on any evidence <strong>of</strong> scientific misconduct.2. If the investigation suspects misconduct a response will be asked from the authors along with raw data, analysis, photographs,genomic sequences, gel pictures, etc., if applicable.3. If the response from authors is satisfactory revealing a mistake or misunderstanding, the matter will be resolved.4. If not, JoTT will withdraw the paper from online version and appropriate announcements will be placed in upcoming issue <strong>of</strong>JoTT.5. JoTT will also inform the respective head <strong>of</strong> the institutions <strong>of</strong> all the authors and the funding agency(s) about themisconduct.2846<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2845–2848

Scientific conduct and misconductAddendums will be peer reviewed before publication.It should be noted that addendums must not challengethe major findings <strong>of</strong> the main paper.A shared responsibilityOur fight against scientific misconduct is a sharedresponsibility (Aronson 2007; Cross 2007; Titus et al.2008; Rathod 2010). While JoTT requests the authorsto follow the norms <strong>of</strong> scientific conduct faithfullyand honestly, JoTT also assures the authors that thereviewing and editing process will be fair. JoTT requeststhe reviewers, subject editors as well as the readers tobe vigilant against any form <strong>of</strong> scientific misconduct.JoTT also assures that none <strong>of</strong> the decisions will betaken hastily and all accusations will be evaluatedobjectively before taking any disciplinary actions.REFERENCESAlberts, B., B. Hanson & K.L. Kelner (2008). Reviewing peerreview. Science 321: 15.Amstrong, J.D. II (1993). Plagiarism: what is it, whom does it<strong>of</strong>fend, and how does one deal with it? American <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong>Roentgenology 161: 479–484.Anonymous (2011). The European Code <strong>of</strong> Conduct for ResearchIntegrity. Published by European Science Foundation andALLEA (All European Academies), 24pp. Aronson, J.K. (2007). Plagiarism-please don’t copy. British<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Clinical Pharmacology 64(4): 403–405.Benos, D.J., E. Bashari, J.M. Chaves, A. Gaggar, N. Kapoor,M. LaFrance, R. Mans, D. Mayhew, S. McGowan, A.Polter, Y. Qadri, S. Sarfare, K. Schultz, R. Splittgerber,J. Stephenson, C. Tower, R.G. Walton & A. Zotov (2007).The ups and downs <strong>of</strong> peer review. Advances in PhysiologyEducation 31: 145–152.Berkenkotter, C. (1995). The power and the perils <strong>of</strong> peerreview. Rhetoric Review 13(2): 245–248.Cross, M. (2007). Policing plagiarism. British Madical <strong>Journal</strong>335: 963–964.Editorial (2011). Combating scientific misconduct. Nature CellBiology 13(1): 1.Errami, M. & H. Garner (2008). A tale <strong>of</strong> two citations. Nature451: 397–399.Errami, M., J.M. Hicks, W. Fisher, D. Trusty, J.D. Wren, T.C.Long & H.R. Garner (2008). Deja vu–a study <strong>of</strong> duplicatecitations in Medline. Bioinformatics 24: 243–249.Fanelli, D. (2009). How many scientists fabricate and falsifyresearch? A systematic review and meta-analysis <strong>of</strong> surveydata. PLoS ONE 4: e5738.Handa, S. (2008). Plagiarism and publication ethics: Dos andN. Dahanukar & S. Molurdon’ts. Indian <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Dermatology, Venereology andLeprology 74: 301–303Kassirer, J.P. & E.W. Campion (1994). Peer review: crude andunderstudied, but indispensable. JAMA: The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> theAmerican Medical Association 272: 96–97.Laband, D.N. & M.J. Piette (1994). A citation analysis <strong>of</strong> theimpact <strong>of</strong> blinded peer review. JAMA: The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> theAmerican Medical Association 272: 147–149.Long, T.C., M. Errami, A.C. George, Z. Sun & H.R. Garner(2009). Responding to possible plagiarism. Science 323:1293–1294.Martinson, B.C., M.S. Anderson & R. de Vries (2005).Scientists behaving badly. Nature 435: 737–738.McNutt, R.A, A.T. Evans, R.H. Fletcher & S.W. Fletcher(1990). The effects <strong>of</strong> blinding on the quality <strong>of</strong> peer review.JAMA: The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> the American Medical Association263: 1371–1376.Montgomerie, B. & T. Birkhead (2005). A beginner’s guide toscientific misconduct. International Society for BehavioralEcology 17(1): 16–24.Mukunda, N. & A. Joshi (2008). Note on plagiarism. <strong>Journal</strong><strong>of</strong> Genetics 87: 99.Rathod, S.D. (2010). Combating plagiarism: a sharedresponsibility. Indian <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Ethics 7: 173–175.Redman, B.K. & J.F. Merz (2008). Scientific misconduct: dothe punishments fit the crime? Science 321: 775.Relman, A.S. (1990). Peer review in scientific journals - whatgood is it? The Western <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medicine 153: 520–522.Resnik, D.B. (2003). From Baltimore to Bell Labs: reflectionson two decades <strong>of</strong> debate about scientific misconduct.Accountability in Research: Policies and Quality Assurance10(2): 123–135.Resnik, D.B. & C.N. Stewart Jr. (<strong>2012</strong>). Misconduct versushonest error and scientific disagreement. Accountability inResearch: Policies and Quality Assurance 19(1): 56–63.Resnik, D.B., S. Peddada & W. Brunson Jr. (2009). Researchmisconduct policies <strong>of</strong> scientific journals. Accountability inResearch: Policies and Quality Assurance 16(5): 254–267.Smith, R. (2006). Peer review: a flawed process at the heart<strong>of</strong> science and journals. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Royal Society <strong>of</strong>Medicine 99: 178–182.Spier, R. (2002). The history <strong>of</strong> the peer-review process. Trendsin Biotechnology 20(8): 357–358.Titus, S.L., J.A. Wells & L.J. Rhoades (2008). Repairingresearch integrity. Nature 453: 980–982.Triggle, C.R. & D. J. Triggle (2007). What is the future <strong>of</strong> peerreview? Why is there fraud in science? Is plagiarism out <strong>of</strong>control? Why do scientists do bad things? Is it all a case <strong>of</strong>:“all that is necessary for the triumph <strong>of</strong> evil is that good mendo nothing”? Vascular Health and Risk Management 3(1):39–53.van Rooyen, S., F. Godlee, S. Evans, R. Smith & N. Black(1998). Effect <strong>of</strong> blinding and unmasking on the quality <strong>of</strong>peer review: a randomized trial. JAMA: The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> theAmerican Medical Association 280: 234–237.2848<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2845–2848

JoTT Co m m u n ic a t i o n 4(9): 2849–2856Western GhatsSpecial SeriesStreamside amphibian communities in plantations and arainforest fragment in the Anamalai hills, IndiaRanjini Murali 1 & T.R. Shankar Raman 21,2Nature Conservation Foundation, 3076/5, 4 th Cross, Gokulam Park, Mysore, Karnataka 570002, IndiaEmail: 1 ranjini@ncf-india.org (corresponding author), 2 trsr@ncf-india.orgDate <strong>of</strong> publication (online): 26 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>Date <strong>of</strong> publication (print): 26 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print)Editor: Sanjay MolurManuscript details:Ms # o2829Received 09 June 2011Final received 27 February <strong>2012</strong>Finally accepted 07 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>Citation: Murali, R. & T.R.S. Raman (<strong>2012</strong>).Streamside amphibian communities in plantationsand a rainforest fragment in the Anamalaihills, India. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> 4(9):2849–2856.Copyright: © Ranjini Murali & T.R. ShankarRaman <strong>2012</strong>. Creative Commons Attribution3.0 Unported License. JoTT allows unrestricteduse <strong>of</strong> this article in any medium for non-pr<strong>of</strong>itpurposes, reproduction and distribution byproviding adequate credit to the authors and thesource <strong>of</strong> publication.Author Details: See end <strong>of</strong> this article.Author Contribution: The first authorparticipated in study design, carried out the fieldwork, analysis, and writing. The second authorhelped design the study, analyse data, and writethe manuscript.Acknowledgements: This study formed part<strong>of</strong> the rainforest restoration and sustainableagriculture project, financially supported bythe Ecosystems Grant Programme <strong>of</strong> theNetherlands Committee for the IUCN, and theCritical Ecosystems Partnership Fund (CEPF).We are grateful to Tata C<strong>of</strong>fee Ltd. and ParryAgro Industries Ltd. for permission to work intheir estates, and to Dinesh and Kannan forfield assistance. We are very grateful to Dr. K.V. Gururaja, Saloni Bhatia, and Sachin Rai fortheir help with the identification <strong>of</strong> amphibiansand to the reviewers for helpful suggestionsthat improved the manuscript. We thank ourcolleagues, Divya Mudappa, M. Ananda Kumar,and P. Jeganathan, for discussions and help.Abstract: Stream amphibian communities, occupying a sensitive environment, are<strong>of</strong>ten useful indicators <strong>of</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> adjoining land uses. We compared abundance andcommunity composition <strong>of</strong> anuran amphibians along streams in tea monoculture, shadec<strong>of</strong>fee plantation, and a rainforest fragment in Old Valparai area <strong>of</strong> the Anamalai hills.Overall species density and rarefaction species richness was the highest in rainforestfragment and did not vary between the c<strong>of</strong>fee and tea land uses. Densities <strong>of</strong> certaintaxa, and consequently community composition, varied significantly among the landuses, being greater between rainforest fragment and tea monoculture with shade c<strong>of</strong>feebeing intermediate. Observed changes are probably related to streamside alterationdue to land use, suggesting the need to retain shade tree cover and remnant riparianrainforest vegetation as buffers along streams.Keywords: Herpet<strong>of</strong>auna, shade c<strong>of</strong>fee, species richness, tea plantation, WesternGhats.IntroductionHabitat alteration, fragmentation, and destruction are the greatestthreats to biodiversity worldwide (Vitousek et al. 1997), especially intropical zones where diversity is high and forests are being transformedat a rapid rate (Pineda & Halffter 2004). The negative effects <strong>of</strong> thesethreats include decreased species richness and abundance, changes inspecies composition, and loss <strong>of</strong> genetic diversity (Saunders et al. 1991;Turner 1996; Laurance et al. 2002; Bell & Donnelly 2006). There isalso increasing concern over the impacts <strong>of</strong> such threats on freshwaterecosystems (Strayer & Dudgeon 2010), particularly streams and rivers(Collier 2011). Streams and stream-dependent organisms are particularlysensitive and most likely to be affected by such changes in land use (Welsh& Ollivier 1998; Sreekantha et al. 2007; Gururaja et al. 2008), especiallyin plantations where they are susceptible to agro-chemical drift, erosionand run-<strong>of</strong>f (Logan 1993).In the tropics, amphibians are good biological indicators <strong>of</strong> streamquality for several reasons. They usually have a bi-phasic life cycle withOPEN ACCESS | FREE DOWNLOADThis article forms part <strong>of</strong> a special series on the Western Ghats <strong>of</strong> India, disseminating theresults <strong>of</strong> work supported by the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF), a joint initiative<strong>of</strong> l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global EnvironmentFacility, the Government <strong>of</strong> Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamentalgoal <strong>of</strong> CEPF is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Implementation <strong>of</strong>the CEPF investment program in the Western Ghats is led and coordinated by the Ashoka Trustfor Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE).<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2849–2856 2849

Streamside amphibian communitiesan aquatic larval stage and a terrestrial adult stage, theirhighly permeable skin makes them extremely sensitiveto physical and chemical changes in their environment,and they occur at high densities in the tropicalenvironments as important primary, mid-level, and topconsumers (Wyman 1990; Wake 1991; Blaustein et al.1994; Bell & Donnelly 2006). During their aquaticstage, many amphibian larvae are susceptible to evenminor changes in the stream environment because <strong>of</strong>their specialised use <strong>of</strong> the stream microhabitats (Welsh& Ollivier 1998). Depending on the availability <strong>of</strong>breeding habitats and the dispersal ability <strong>of</strong> species,streams in a region can vary considerably in amphibiandiversity and this variation can greatly influence localand regional amphibian species diversity (Krishna etal. 2005; Vasudevan et al. 2006).The Western Ghats mountains, a biodiversityhotspot, extend for nearly 1600km (from 8 0 N to 21 0 N)along the west coast <strong>of</strong> India. Considerable tractsin the wetter and higher reaches, once covered bytropical rainforests are now dominated by plantations<strong>of</strong> tea, c<strong>of</strong>fee, rubber, and cardamom with isolatedfragments <strong>of</strong> forests and other areas <strong>of</strong> conservationvalue (Kumar et al. 2004; Das et al. 2006; Bali etal. 2007; Dolia et al. 2008). The region has a highdiversity and endemism <strong>of</strong> amphibian species with181 known species, (including new species describedin recent years) <strong>of</strong> which 159 (88%) are endemic to theWestern Ghats (Aravind & Gururaja 2011; Bhatta et al.2011; Biju et al. 2011; Dinesh & Radhakrishna 2011;Zachariah et al. 2011a,b). There is need for betterdocumentation <strong>of</strong> the animal communities <strong>of</strong> tropicalstreams in the Western Ghats and the relationshipbetween community structure and terrestrial landscapeelements or land-uses (Krishna et al. 2005; Sreekanthaet al. 2007; Gururaja et al. 2008; Karthick et al. 2011;Prakash et al. <strong>2012</strong>).Here, we evaluate the influence <strong>of</strong> land use onstream anuran diversity and density in the WesternGhats <strong>of</strong> southern India during the monsoon season.Earlier research from other parts <strong>of</strong> the Western Ghatshas shown that amphibians can be sensitive indicators<strong>of</strong> change in habitat and land-use (Daniels 2003;Krishna et al. 2005; Gururaja et al. 2008). We extendthis work to a fragmented landscape in the Anamalaihills where we compare the occurrence, abundance,and species composition <strong>of</strong> anurans along streamsin three land uses: monoculture tea plantation, shadeR. Murali & T.R.S. Ramanc<strong>of</strong>fee plantation, and rainforest fragment. This studyaimed to understand stream amphibian communityresponse to alterations in land use in order to helpin formulating strategies for species conservation inhuman-dominated landscapes.Materials and MethodsThis study was conducted during July and <strong>August</strong>2010 (southwest monsoon season) in the Valparaiplateau in the Tamil Nadu part <strong>of</strong> the Anamalai hillsin the southern Western Ghats. The Valparai plateauspans an area <strong>of</strong> 220km² with plantations <strong>of</strong> tea(Camellia sinensis), c<strong>of</strong>fee (Arabica: C<strong>of</strong>fea arabica,Robusta: C. canephora), Eucalyptus, and cardamom(Elettaria cardamomum) plantations with around 40rainforest fragments embedded in the landscape matrix(Mudappa & Raman 2007). The Valparai plateau lieswithin a larger landscape adjoining the AnamalaiTiger Reserve (958km², 10 0 12’–10 0 35’N and 76 0 49’–77 0 24’E) to the north and east in Tamil Nadu, andreserved forests and the Parambikulam Tiger Reserveto the south and west in Kerala.The selected sites included tea and c<strong>of</strong>feeplantation in Velonie Estate, and Tata Finlay (OldValparai) rainforest fragment, all <strong>of</strong> which were withina 2km radius and at an altitude <strong>of</strong> c. 1000m (Image 1).Sampling was carried out along a first order and fourthorder stream in both c<strong>of</strong>fee and tea plantations, whileonly first order stream was available within the 32harainforest fragment for sampling. The same fourthorder stream flowed through the tea and c<strong>of</strong>fee. Thefirst order streams in the c<strong>of</strong>fee and the tea estate wereboth around 100m long.Visual encounter surveys (Heyer et al. 1994) werecarried out in quadrats 50m long and 4m wide. Sevenseparate quadrats were sampled in each habitat, foursampled once and three sampled on two occasionsyielding a total <strong>of</strong> 10 samples in each land-use type. Asthe sampling in the repeat quadrats was carried out atleast six weeks apart, they are considered independentsamples for the purpose <strong>of</strong> the present analysis. Fivequadrats were along the fourth order stream in thec<strong>of</strong>fee and tea estate and two quadrats were along thefirst order streams.All quadrat surveys were carried out at nightbetween 1900 and 2000 hr. Two observers surveyed2850<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2849–2856

Streamside amphibian communitiesR. Murali & T.R.S. RamanImage 1. Map showing locations <strong>of</strong> start and end points along stream transects (yellow lines) in the Valparai plateau,Anamalai hills (Courtesy: Google Earth).each quadrat using torches to look for amphibianswhile walking very slowly to complete each quadratin 60 min. No stones or logs were overturned alongthe site so as to cause minimum disturbance to thehabitat and shrubs (c<strong>of</strong>fee and tea, in the case <strong>of</strong>plantations) were also scanned during the sampling.Most amphibians were identified in the field. We madeno specimen collections and minimised handling toavoid harm or disturbance to amphibians. Photographswere taken <strong>of</strong> amphibians that could not be identifiedon field for later identification using field guides(Daniel 2002), taxonomic literature (Kuramoto et al.2007; Biju & Bossuyt 2009), and consultation withexperts (K.V. Gururaja, Sachin Rai, Saloni Bhatia).All species belonging to the genus Fejervarya andRaorchestes were identified only to the genus level asproper identification would require closer taxonomicand genetic analysis. Further, all young ones wereexcluded from this study.Species diversity <strong>of</strong> amphibians was analysed bothas species density (number <strong>of</strong> species per quadrat)as well as species richness (number <strong>of</strong> species for astandardised sample <strong>of</strong> 100 individuals) followingGotelli & Colwell (2001). Estimates <strong>of</strong> species richness(and corresponding 95% confidence intervals) throughrarefaction analysis were made using the programEcoSim (Gotelli & Entsminger 2009). Amphibiandensity was measured as the number <strong>of</strong> amphibians perquadrat (density <strong>of</strong> individuals) for both total individuals(total density) as well as for individual taxa. We usedone-way analysis <strong>of</strong> variance (ANOVA) followed byTukey’s HSD tests to examine statistical significance<strong>of</strong> differences among land uses in species densityand amphibian densities (total density and individualtaxa). For individual taxa, ANOVA was performedonly for those taxa where more than 10 individualswere observed (i.e., Duttaphrynus sp. and Indirana sp.were excluded). ANOVA and Tukey HSD tests wereperformed using the R statistical and programmingenvironment (version 2.10, R Development Core Team2009). Amphibian species composition across siteswas analysed by non-metric multi-dimensional scaling(MDS) ordination <strong>of</strong> the Bray-Curtis dissimilaritymatrix <strong>of</strong> quadrats, using the s<strong>of</strong>tware PRIMER(Clarke & Warwick 1994; Clarke & Gorley 2001).Significance <strong>of</strong> variation in community compositionwas assessed using analysis <strong>of</strong> similarities (ANOSIM)using PRIMER (Clarke & Warwick 1994).<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2849–28562851

Streamside amphibian communitiesR. Murali & T.R.S. RamanTable 1. Amphibian density along streams in the three land-use types in the Anamalai hills. Tabled values represent densityas individuals / 200 m² ± SE, total number <strong>of</strong> individuals recorded (in parantheses), and statistics from 1-way analysis <strong>of</strong>variance (ANOVA).Taxon Tea* C<strong>of</strong>fee* Rainforest* ANOVA F (2,27)PAll 12.2±1.47 (122) 14.9±2.09 (149) 14.2±1.45 (142) 0.68 0.514Duttaphrynus melanostictus 0.6±0.31 (6) 0.4±0.22 (4) 0.1±0.10 (1) 1.25 0.303Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis 0.6±0.27 ab (6) 2.4±0.86 b (24) 0 a (0) 5.79 0.008Fejervarya sp. 10±1.57 b (100) 6.3±0.98 ab (63) 2.4±1.24 a (24) 8.73 0.001Hylarana aurantiaca (Image 2) 0.2±0.13 (2) 1.8±1.06 (18) 2.5±0.87 (25) 2.19 0.132Hylarana temporalis (Image 3) 0 (0) 1.1±0.72 (11) 1.4±0.31 (14) 2.65 0.089Nyctibatrachus sp. 0 b (0) 0 b (0) 1±0.30 a (10) ** **Micrixalus sp. (Image 4) 0 b (0) 0 b (0) 5.9±1.80 a (59) ** **Raorchestes sp. 0.7±0.26 a (7) 2.9±0.94 b (29) 0.7±0.21 a (7) 4.89 0.015Duttaphrynus sp. 0 (0) 0 (0) 0.1 (1) - -Indirana sp. 0.1 (1) 0 (0) 0.1 (1) - -*Different superscripted alphabets indicate statistically significant difference from each other as per Tukey HSD multiple comparisons test.** Although ANOVA outputs indicated significantly higher density in rainforest, the statistical test results were superfluous because these two taxa werecompletely absent in the samples from plantations.Figure 2. Variation in amphibian species composition in quadrat samples along streams in three land-use types in theAnamalai hills using non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) ordination.Quadrat labels: F - Rainforest fragment, C - C<strong>of</strong>fee plantation, and T - Tea plantation.atmospheric humidity (Saunders et al. 1991; Pineda &Halffter 2004) could account for the decreased speciesrichness in c<strong>of</strong>fee and tea plantations. Similarly,Krishna et al. (2005) reported a decrease in richnessbetween forest and c<strong>of</strong>fee and cardamom land uses inthe central Western Ghats.Studies on conservation value <strong>of</strong> plantations inthe Western Ghats for other taxonomic groups haveshown that a diversity <strong>of</strong> species use these plantations,including many species typical to forests <strong>of</strong> the regionas well as more widely distributed species <strong>of</strong> more openhabitats (Raman 2006; Bali et al. 2007; Dolia et al.2008; Anand et al. 2008). Daniels (2003) also opinedthat tea plantations were capable <strong>of</strong> supporting manyamphibian species. Similarly, our study indicates thata number <strong>of</strong> anurans use the c<strong>of</strong>fee and tea plantations,<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2849–28562853

Streamside amphibian communities© Kalyan VarmaImage 2. Hylarana aurantiacaImage 3. Hylarana temporalisImage 4. Micrixalus sp.© Kalyan Varma© Kalyan VarmaR. Murali & T.R.S. Ramanalthough the diversity is lower than in the rainforestfragment.Species composition <strong>of</strong>ten varies among land usetypes, and species with specific ecological requirementsthat are not available in modified land uses may bemore affected than others (Waltert et al. 2004). In thepresent study, Micrixalus sp. and Nyctibatrachus sp.(genera <strong>of</strong> mainly forest-dependent species endemicto the Western Ghats; Aravind & Gururaja 2011) werethe most affected by land use, being absent from c<strong>of</strong>feeand tea plantations. Krishna et al. (2005) also reportedthe absence <strong>of</strong> Micrixalus sp. from c<strong>of</strong>fee plantations.The highest number <strong>of</strong> Fejervarya sp. was found inthe tea estate. Fejervarya are generalists known tooccur near still and stagnant water where they areknown to breed (Kuramoto et al. 2007), such habitatswere available in the streams through tea estate wheredue to open canopy and dense growth <strong>of</strong> grassesand sedges, the streams were partly swampy alongthe valley. Daniels (2003) also noted the commonoccurrence <strong>of</strong> generalist anurans such as Fejervaryasp. and Duttaphrynus melanostictus in his survey in teaplantations. Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis was completelyabsent in the forest fragment and was sighted mainlyin c<strong>of</strong>fee with very few individuals recorded in tea.This species is aquatic or semi-aquatic and usuallylive half submerged in water or at the water’s edgein ponds, wetlands, paddy fields and ditches (Joshy etal. 2009). Andrews et al. (2005) and Krishna et al.(2005) also reported an absence <strong>of</strong> Euphlyctis sp. fromrainforest. Our results showing more generalist speciesin plantations and more forest-dependent endemicspecies in fragments are consistent with Gururaja etal.’s (2008) observation that human induced changesin land-uses, canopy cover, and hydrological regimesmay support generalist amphibian species whereas lessdisturbed forest areas with higher canopy cover, treedensity and rainfall support more endemic species.The differences in species composition may be dueto variation in streamside vegetation and environment,including decreased riparian vegetation and decreasedclear-flowing water in the plantations, especiallythe highly modified tea monocultures (as noticedin a parallel study in the same landscape; Prakashet al. <strong>2012</strong>). It is unlikely that variation in speciescomposition is due to variation in stream order as thefirst and fourth order streams in the c<strong>of</strong>fee and the teaplantations did not differ noticeably from each other,2854<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2849–2856

Streamside amphibian communitieswhile clearly differing from the first order streamthrough the rainforest fragment. As amphibians<strong>of</strong>ten display a patchy distribution linked to microclimateconditions or spawning places (Zimmerman& Bierregaard 1986), such factors may be moreinfluential on variation in species composition due toland use change.Despite some clear patterns, the present study hadseveral limitations. Being carried out during Julyand <strong>August</strong>, it is representative only <strong>of</strong> the southwestmonsoon season. Besides canopy species beingcompletely omitted, other species may have beenmissed as well as the observers tried to be as nonintrusiveas possible. Visibility also varied acrossthe three land uses, being highest in tea, followedby c<strong>of</strong>fee, and then rainforest fragment, suggestingthat the higher richness in the latter may only be aconservative estimate. However, the species richnessin the c<strong>of</strong>fee land use may be higher as Raorchestessp., identified only to genus, may represent severalspecies. We conclude that a longer-term study <strong>of</strong>amphibian species in c<strong>of</strong>fee and tea plantations canprovide a more comprehensive view <strong>of</strong> the effects <strong>of</strong>land use change, <strong>of</strong> which the present study forms auseful baseline. Such research can also help pinpointbetter agricultural land-use practices that minimiseor avoid negative environmental impacts on streams(Logan 1993), and may be linked to opportunitiesfor sustainable agriculture certification for plantationbusinesses that adopt such better land-use practices(Aerts et al. 2010).ReferencesAerts, J., D. Mudappa & T.R.S. Raman (2010). C<strong>of</strong>fee,conservation, and Rainforest Alliance certification:opportunities for Indian c<strong>of</strong>fee. Planters’ Chronicle 106(12):15–26.Anand, M.O., J. Krishnaswamy & A. Das (2008). Proximityto forests drives bird conservation value <strong>of</strong> shade-c<strong>of</strong>feeplantations: Implications for certification. EcologicalApplications 18: 1754–1763.Andrews, M.I., S. George & J. Joseph (2005). Amphibians inprotected areas <strong>of</strong> Kerala. Zoos’ Print <strong>Journal</strong> 20(4): 1823–1831.Aravind, N.A. & K.V. Gururaja (2011). Amphibians <strong>of</strong> theWestern Ghats. Theme paper, Western Ghats Ecology ExpertPanel, Ministry <strong>of</strong> Environment and Forests, India.Bali, A., A. Kumar & J. Krishnaswamy (2007). The mammalianR. Murali & T.R.S. Ramancommunities in c<strong>of</strong>fee plantations around a protected areain the Western Ghats, India. Biological Conservation 139:93–102.Bell, K.E. & M.A. Donnelly (2006). Influence <strong>of</strong> forestfragmentation on community structure <strong>of</strong> frogs and lizardsin Northeastern Costa Rica. Conservation Biology 20: 1750–1760.Bhatta, G., K.P. Dinesh, P. Prashanth, N. Kulkarni & C.Radhakrishnan (2011). A new caecilian Ichthyophis davidisp. nov. (Gymnophiona: Ichthyophiidae): the largest stripedcaecilian from the Western Ghats. Current Science 101:1015–1018.Biju, S.D. & F. Bossuyt (2009). Systematics and phenology <strong>of</strong>Philautus Gistel, 1848 (Anura Rhacophoridae) in the WesternGhats <strong>of</strong> India with description <strong>of</strong> 12 new species. Zoological<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Linnean Society 155: 374–444.Biju, S.D., I.V. Bocxlaer, S. Mahony, K.P. Dinesh, C.Radhakrishnan, A. Zachariah, V. Giri & F. Bossuyt(2011). A taxonomic review <strong>of</strong> the Night Frog genusNyctibatrachus Boulenger, 1882 in the Western Ghats, India(Anura: Nyctibatrachidae) with description <strong>of</strong> twelve newspecies. Zootaxa 3029: 1–96.Blaustein, A.R., D.B. Wake & W.P. Sousa (1994). Amphibiandeclines: judging stability, persistence, and susceptibility <strong>of</strong>populations to local and global extinctions. ConservationBiology 8: 60–71.Clarke, K.R. & R.N. Gorley (2001). Primer v5: User manual/tutorial. PRIMER-E, Plymouth.Clarke, K.R. & R.M. Warwick (1994). Change in marinecommunities: An approach to statistical analysis andinterpretation. Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Plymouth.Collier, K.J. (2011). The rapid rise <strong>of</strong> streams and rivers inconservation assessment. Aquatic Conservation: Marine andFreshwater Ecosystems 21: 397–400.Daniel, J.C. (2002). The Book <strong>of</strong> Indian Reptiles and Amphibians.Bombay Natural History Society. Oxford University Press,238pp.Daniels, R.J.R. (2003). Impact <strong>of</strong> tea cultivation on anurans inthe Western Ghats. Current Science 85: 1415–1421.Das, A., J. Krishnaswamy, K.S. Bawa, M.C. Kiran, V. Srinivas,N.S. Kumar & K.U. Karanth (2006). Prioritisation <strong>of</strong>conservation areas in the Western Ghats, India. BiologicalConservation 133: 16–31.Dinesh, K.P. & C. Radhakrishnan (2011). Checklist <strong>of</strong>amphibians <strong>of</strong> Western Ghats. Frogleg 16: 15–21.Dolia, J., M.S. Devy, N.A. Aravind & A. Kumar (2008). Adultbutterfly communities in c<strong>of</strong>fee plantations around a protectedarea in the Western Ghats, India. Animal Conservation 11:26–34.Gotelli, N.J. & R.K. Colwell (2001). Quantifying biodiversity:procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison<strong>of</strong> species richness. Ecology Letters 4: 379–391.Gotelli, N.J. & G.L. Entsminger (2009). EcoSim: Null modelss<strong>of</strong>tware for ecology. Version 7. Acquired Intelligence Inc.& Kesey-Bear. Jericho, VT 05465 < http://garyentsminger.com/ecosim/index.htm><strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2849–28562855

Streamside amphibian communitiesGururaja, K.V., A. Sameer & T.V. Ramachandra (2008).Influence <strong>of</strong> land-use changes in river basins on diversity anddistribution <strong>of</strong> amphibians, pp. 33–42. In: Ramachandra, T.V.(ed.). Environment Education for Ecosystem Conservation.Capital Publishing Company, New Delhi.Heyer, W.R., M.A. Donnelley, R.W. McDiarmid, L.C. Hayek,& M.S. Foster (eds.) (1994). Measuring and MonitoringBiological Diversity: Standard Methods for Amphibians.Smithsonian Institution Press, 384pp.Joshy, S.H., M.S. Alam, A. Kurabayashi, M. Sumida & M.Kuramoto (2009). Two new species <strong>of</strong> genus Euphlyctis(Anura, Ranidae) from southwestern India, revealed bymolecular and morphological comparisons. Alytes 26: 97–116.Karthick, B., M.K. Mahesh & T.V. Ramachandra (2011).Nestedness pattern in stream diatom assemblages <strong>of</strong> centralWestern Ghats. Current Science 100(4): 552–558.Krishna, S.N., S.B. Krishna & K.K. Vijayalaxmi (2005).Variation in anuran abundance along the streams <strong>of</strong> theWestern Ghats, India. Herpetological <strong>Journal</strong> 15: 167–172.Kumar, A., R. Pethiyagoda & D. Mudappa (2004). WesternGhats and Sri Lanka, pp.152–157. In: Mittermeier, R.A., P.R.Gil, M. H<strong>of</strong>fmann, J. Pilgrim, T. Brooks, C.G. Mittermeier,J. Lamoureux & G.A.B. da Fonseca (eds.)Hotspots Revisited- Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most EndangeredEcoregions. CEMEX, Mexico.Kuramoto, M., S.H. Joshy, A. Kurabayashi & M. Sumida(2007). The genus Fejervarya (Anura: Ranidae) in centralWestern Ghats, India, with descriptions <strong>of</strong> four new crypticspecies. Current Herpetology 26: 81–105.Laurance, W.F., T.E. Lovejoy, H.L. Vasconcelos, E.M. Bruna,R.K. Didham, P.C. Stouffer, C. Gascon, R.O. Bierregaard,S.G. Laurance & E. Sampaio (2002). Ecosystem decay<strong>of</strong> Amazonian forest fragments: a 22-year investigation.Conservation Biology 16: 605–618.Logan, J.T. (1993). Agricultural best management practicesfor water pollution control: current issues. Agriculture,Ecosystems and Environment 46: 223–231.Mudappa, D. & T.R.S. Raman (2007). Rainforest restorationand wildlife conservation on private lands in the Valparaiplateau, Western Ghats, India, pp. 210–240. In: Shahabuddin,G. & M. Rangarajan (eds.). Making Conservation Work.Permanent Black, Ranikhet.Pineda, E. & G. Halffter (2004). Species diversity and habitatfragmentation: frogs in a tropical montane landscape inMexico. Biological Conservation 117: 499–508.Prakash, N., D. Mudappa, T.R.S. Raman & A. Kumar (<strong>2012</strong>).Conservation <strong>of</strong> the Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyxcinereus) in human-modified landscapes, Western Ghats,India. Tropical Conservation Science 5: 67–78.R Development Core Team (2009). R: A language andenvironment for statistical computing. R Foundation forStatistical Computing,Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL Raman, T.R.S. (2006). Effects <strong>of</strong> habitat structure and adjacenthabitats on birds in tropical rainforest fragments and shadedR. Murali & T.R.S. Ramanplantations in the Western Ghats, India. Biodiversity andConservation 15: 1577–1607.Saunders, D.A., R.J. Hobbs & C.R. Margules (1991).Biological consequences <strong>of</strong> ecosystem fragmentation: areview. Conservation Biology 5: 18–30.Sreekantha, M.D., S. Chandran, D.K. Mesta, G.R. Rao, K.V.Gururaja & T.V. Ramachandra (2007). Fish diversityin relation to landscape and vegetation in central WesternGhats, India. Current Science 92(11): 1592–1603.Strayer, D.L. & D. Dudgeon (2010). Freshwater biodiversityconservation: recent progress and future challenges. <strong>Journal</strong><strong>of</strong> the North American Benthological Society 29: 344–358.Turner, I.M. (1996). Species loss in fragments <strong>of</strong> tropical rainforest: a review <strong>of</strong> the evidence. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Applied Ecology33: 200–209.Vasudevan, K., A. Kumar & R. Chellam (2006). Speciesturnover: the case <strong>of</strong> stream amphibians <strong>of</strong> rainforests in theWestern Ghats, southern India. Biodiversity and Conservation34: 3515–3525.Vitousek, P.M., H.A. Mooney, J. Lubchenco & J.M. Melillo(1997). Human domination <strong>of</strong> Earth’s ecosystems. Science277: 494–499.Waltert, M., A. Mardiastuti & M. Muhlenberg (2004). Effects<strong>of</strong> land use on bird species richness in Sulawesi, Indonesia.Conservation Biology 18: 1339–1346.Wake, D.B. (1991). Declining amphibian populations. Science253: 860.Welsh, H.H. & M.L. Ollivier (1998). Stream amphibians asindicators <strong>of</strong> ecosystem stress: A case study from California’sRedwoods. Ecological Applications 8: 1118–1132.Wyman, R.L. (1990). What’s happening to the amphibians?Conservation Biology 4: 350–352.Zachariah, A., K.P. Dinesh, E. Kunhikrishnan, S. Das,D.V. Raju, C. Radhakrishnan, M.J. Palot & S. Kalesh(2011a). Nine new species <strong>of</strong> frogs <strong>of</strong> the genus Raorchestes(Amphibia: Anura: Rhacophoridae) from southern WesternGhats, India. Biosystematica 5: 25–48.Zachariah, A., K.P. Dinesh, C. Radhakrishnan, E.Kunhikrishnan, M.J. Palot & C.K. Vishnudas (2011b).A new species <strong>of</strong> Polypedates Tschudi (Amphibia: Anura:Rhacophoridae) from southern Western Ghats, Kerala, India.Biosystematica 5: 49–53.Zimmerman, B.L. & R.O. Bierregaard (1986). Relevance <strong>of</strong>the equilibrium theory <strong>of</strong> island biogeography and speciesarearelations to conservation with a case from Amazonia.<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Biogeography 13: 133–143.Author Details: Ra n j i n i Mu r a l i worked as a Research Affiliate on thisproject and currently works as the Conservation Coordinator in the HighAltitude Programme <strong>of</strong> the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF).T.R. Sh a n k a r Ra m a n is a Senior Scientist with NCF working on rainforestrestoration and conservation in the Western Ghats.2856<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2849–2856

JoTT Co m m u n ic a t i o n 4(9): 2857–2874Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea and Hesperoidea)and other protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones Estate, a dyingwatershed in the Kumaon Himalaya, Uttarakhand, IndiaPeter SmetacekButterfly Research Centre, The Retreat, Jones Estate, Bhimtal, Uttarakhand 263136, IndiaEmail: petersmetacek@rediffmail.comDate <strong>of</strong> publication (online): 26 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>Date <strong>of</strong> publication (print): 26 <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong>ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print)Editor: Rudi MattoniManuscript details:Ms # o3020Received 25 November 2011Final received 02 February <strong>2012</strong>Finally accepted 15 July <strong>2012</strong>Citation: Smetacek, P. (<strong>2012</strong>). Butterflies(Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea and Hesperoidea)and other protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones Estate,a dying watershed in the Kumaon Himalaya,Uttarakhand, India. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong>4(9): 2857–2874.Copyright: © Peter Smetacek <strong>2012</strong>. CreativeCommons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.JoTT allows unrestricted use <strong>of</strong> this article in anymedium for non-pr<strong>of</strong>it purposes, reproductionand distribution by providing adequate credit tothe authors and the source <strong>of</strong> publication.Author Details: Pe t e r Sm e t a c e k is an authorityon Indian Lepidoptera and has pioneered theuse <strong>of</strong> insect communities as bio-indicators <strong>of</strong>climatic change and ground water.Acknowledgements: I am grateful to my latefather, Fred Smetacek Sr.; to the Times FellowshipCouncil, New Delhi, for a Fellowship to studyIndian rivers in 1992 and to the Rufford SmallGrant Foundation, U.K., for funding the work onLepidoptera and Himalayan forest ecosystemsbetween 2006 and the present study via aseries <strong>of</strong> grants. I am indebted to Rudi Mattoni,Argentina for encouragement to write this andvaluable suggestions on an earlier draft anddrawing my attention to the format developed byhim and used in Table 1 and to Zdenek FaltynekFric, Ceske Budejovice in the Czech Republic, forvaluable taxonomic comments on Table 1. Also, Iam indebted to the anonymous referees whoserecommendations considerably improved thepaper and to my children, Kanika and Pius, whospent many hours sorting through note books,loose leaf lists, books and specimens to compilethe enormous amount <strong>of</strong> data that went into themaking <strong>of</strong> Table 1.OPEN ACCESS | FREE DOWNLOADAbstract: Two hundred and forty three species <strong>of</strong> butterflies recorded from Jones Estate,Uttarakhand between 1951 and 2010 are reported. The ongoing rapid urbanization <strong>of</strong>Jones Estate micro-watershed will destroy the habitat <strong>of</strong> 49 species <strong>of</strong> wildlife protectedunder Indian law, as well as several species <strong>of</strong> narrow endemic moths and butterflies.The only known Indian habitat for the butterfly Lister’s Hairstreak Pamela dudgeoniwill be destroyed. The effect on the water flow <strong>of</strong> both the Bhimtal and Sattal lakesystems will clearly be adverse, as is evident from the drying up <strong>of</strong> Kua Tal and thereduced flow <strong>of</strong> perennial water springs during the dry season on the Estate. Theundoubtedly negative effect <strong>of</strong> urbanization on these valuable fresh water resources willbe irreversible in the long term. The trend can be reversed by extending protection toJones Estate by re-declaring it a Green Belt <strong>of</strong> Bhimtal and by banning construction inthe catchment area <strong>of</strong> Bhimtal lake, as has been done in Nainital and Mussoorie, bothin Uttarakhand.Keywords: Bhimtal, drinking water, drying lakes, freshwater resources, Green Belt,Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972, Pamela dudgeoni.Hindi Abstract: lu~ 1951 vkSj 2010 ds chp tkSal LVsV mRrjk[k.M esa ladfyr 243 iztkfr dh frrfy;ksa dk o.kZufn;k x;k gSA orZeku esa tkSl LVsV lw{e tykxe esa rsth l spy jgh ‘kgjhdj.k dh izfØ;k ls Hkkjrh; dkuwu ds vUrxZrlajf{kr 49A ou tho dh iztkfr;ka rFkk dbZ fo’ks”k iraxs vkSj frrfy;ksa dh iztkfr ¼tks dsoy tkSal LVsV esa ikbZ tkrhgSa½ ds vkokl u”V gks tk;saxsA blesa fyLV~lZ gS;j LVªhd frryh dk Hkkjr esa ,d ek= fuokl u”V gks tk;sxkA HkherkyrFkk lkrrky >hyksa dk ikuh ds ty lzksr ij bldk dqizHkko iM+sxkA bldk orZeku esa daqvkrky ty lzksr ds lw[kusrFkk bykds ds lnkcgkj ty lzksr ds xehZ ds ekSle esa yxHkx lw[k tkus ls Li”V gSA yacs le;k<strong>of</strong>/k esa bu vewY; ehBsikuh ds la’kk/kuksa ij ‘kgjhdj.k ds udjkRed vlj dk dksbZ lq/kkj rHkh laHko gS tc tkSal LVsV dks gfjr iV~Vh ?kksf”krdh tk;s rFkk Hkherky >hy d sty laxzg.k {ks= esa fuekZ.k dk;Z ij ikcanh yxs tSls fd mRrjk[k.M ea uSuhrky rFkkelwjh esa fd;k x;k gSAINTRODUCTIONJones Estate (“June State” on Revenue Department records) is aforested microwatershed in Nainital district, Uttarakhand (29 0 21’17”N &79 0 32’34.27”E), separating the Bhimtal and Sattal lake systems (Image1). In the Himalaya, it is a unique geographical feature, being the onlyforested watershed separating two lake systems comprising a total <strong>of</strong>eight perennial and seasonal lakes. Bhimtal (tal = lake in Hindi) lies atthe southeastern end while the Sattal lies along the northern half <strong>of</strong> thewestern face <strong>of</strong> the Estate. Comprising roughly 4.8 sq.km (1200 acres) <strong>of</strong>private forest in 1951, the forest area <strong>of</strong> Jones Estate has been reduced byroughly 30% due to cultivation and habitation over the years.The lowest point is 1200m at the conjoined Ram and Sita lakes<strong>of</strong> the Sattal (seven lakes) system, while the highest point is Thalaat 1731m. The range runs northwest to southeast for a distance <strong>of</strong>roughly 3km from Dhupchaura pass on the northwest to Tallitalmarket and Bohrakun Village on its southeastern and southern facesrespectively (Image 1). To the east lies the Bhimtal lake system comprising<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2857–2874 2857

Protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones EstateP. SmetacekImage 1. Google map showing Jones Estate watershed outlined in white and adjoining lake systems. Source: GooglemapsImage 2. Garurtal with the western face <strong>of</strong> Jones Estate inthe background.<strong>of</strong> three lakes—Nal-Damayantital, Kuatal and Bhimtal.To the west lies the Sattal lake system comprising <strong>of</strong>Pannatal (=Garurtal) (Image 2); Ramtal and Sitatal,Lakshmantal, Sukhatal, Sariyatal and Lokhamtal.Jones Estate lies in the outermost range <strong>of</strong> theHimalayan foothills and receives heavy rainfall.Although Osmaston (1927) gives a range <strong>of</strong> 2000–3000 mm <strong>of</strong> rainfall for this area, actual precipitation israther less nowadays, averaging 1443mm for the fiveyearperiod from 2005 to 2009 (Anonymous 2010).The forest consists <strong>of</strong> three plant associations,namely sub-tropical broadleaf with HimalayanOak Quercus leucotrichophora as a nodal species;Chir Pine Pinus roxburghii forest and elements <strong>of</strong>miscellaneous deciduous forest. In addition, there is2858<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2857–2874

Protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones Estatea patch <strong>of</strong> naturalized Himalayan Cypress Cupressustorulosa several acres in extent.HISTORYThe Bhimtal Valley has been inhabited and cultivatedfor over a millennium and Atkinson (1882) noted thatit was one <strong>of</strong> the largest single sheets <strong>of</strong> cultivation inthe Kumaon Himalaya.Jones Estate watershed and the Sattal Valley werenot inhabited during past centuries, although some smallpatches <strong>of</strong> cultivation were attempted by share-croppersand itinerant families until 1952. The major part <strong>of</strong> theEstate has always been forested. It came into existencein 1867 as a fee-simple estate, with the main aim<strong>of</strong> developing it for the production <strong>of</strong> green tea for theTibetan market. Since then, it has remained in privatehands.On 17 January 2001 the then Minister forEnvironment and Forests, Mr. Kandari, stated inthe Uttarakhand State Assembly that all concernedgovernment departments, including the Public WorksDepartment, Forest Department, Pollution ControlDepartment, etc. in their reports on the possibility<strong>of</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> buildings on the Jones Estatewatershed, had stressed that any such move wouldresult in disastrous consequences for Bhimtal and forthe water storage capability <strong>of</strong> the Sattal lakes (SpecialCorrespondent 2001).In 1954, a Forest Working Plan was passed forJones Estate by the Forest Department. In the LandRecord Settlement known as the Bandobast in 1957,land use <strong>of</strong> the greater part <strong>of</strong> Jones Estate wasrecorded as “forest”. Under the provisions <strong>of</strong> theForest Conservation Act 1980, no land use change ispermitted on such land without the permission <strong>of</strong> theCentral Government.Despite this, numerous houses and resortsare being constructed and there is no doubt thatthe eventual urbanization <strong>of</strong> the Estate is well underway, to the detriment <strong>of</strong> the Bhimtal and Sattal lakesystems and the wildlife inhabiting the Estate atpresent. Therefore, the present paper documents thebutterflies recorded on the Estate (Table 1) so as toget a better idea <strong>of</strong> what is being lost and the eventualconsequences <strong>of</strong> urbanization <strong>of</strong> the Jones Estatewatershed.P. SmetacekThe present paper also documentsthe butterflies and vertebrates affordedprotection under the Schedules <strong>of</strong> the Indian Wildlife(Protection) Act 1972 (Anonymous 2006) that havebeen recorded on the Estate (Table 2). In total, theseconstitute 49 species, 11 on Schedule 1 and 39 onSchedule 2 (Hypolimnas misippus Linnaeus figures onboth Schedules and is counted only once).MATERIAL AND METHODSThe butterflies <strong>of</strong> the Estate have been studiedsince 1951. Some original specimens still exist, butthe major resource from this era is in the form <strong>of</strong> notesmaintained by my father, the late Fred Smetacek Sr. Inthe course <strong>of</strong> studying local butterflies, two butterflysubspecies new to science were discovered on theEstate, namely Neptis miah varshneyi Smetacek andNeptis clinia praedicta Smetacek (both Nymphalidae)(Smetacek 2002; 2011b). Besides, several butterfliespreviously unrecorded from the Western Himalayahave been reported (Smetacek 2010). Moths have beenstudied since 1972. Several species new to sciencehave been described from the Estate (Smetacek 2002;2005; 2010a). Besides, the population <strong>of</strong> hawkmoths(Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) on the Estate providedmaterial for pioneering work in using members <strong>of</strong>an insect community as bio-indicators to predict andtrack climate change (Smetacek 1994; 2004).The sightings <strong>of</strong> mammals and birds included inAnnexure 2 were compiled mostly during the 1980s,when much time was spent patrolling the forest. Theyare all based on actual sightings by the author. Themost recent sighting <strong>of</strong> a mammal protected under theprovisions <strong>of</strong> the Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972 andlisted as Near <strong>Threatened</strong> on the IUCN Red Data Listis <strong>of</strong> a Himalayan Serow (Capricornis sumatraensisthar) which was sighted and photographed outside theButterfly Research Centre, Jones Estate at 10am on 07November 2011.The use <strong>of</strong> a lepidopteran community as an indicator<strong>of</strong> forest health and consequently the health <strong>of</strong> theecosystem including sub-surface water resources hasbeen explored on the Estate by the author for thepast 30 years (Smetacek 1993–2010). The format <strong>of</strong>Image 1, which enables a great deal <strong>of</strong> informationto be presented concisely, has been taken with kind<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2857–28742859

Protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones EstateP. SmetacekTable 1. Butterflies recorded in Jones Estate, Bhimtal, Between 1951 and 2011.1 - Name2 - Geographic distribution <strong>of</strong> the species.3 - General distribution G - garden species, found everywhere; NA - widespread but only in undisturbed areas; LO - localized incolonies; RM - not resident, but regular migrants; SM - sporadic,rare migrants;4 - Usual Habitat: U - universal across all habitats; SE - subtropical evergreen forest above 1200m; TD - tropical deciduous forestbetween 400 and 1400 m; SR - Shorea robusta forest below 1000m; S - scrubland; G - grassland.5 - Relative abundance, sightings per day during seasonal optimum: V - very rare, none or one: R - rare (2–4); O - occasional (5–9);A - abundant (10–49); C - common (>50).6 - Index <strong>of</strong> relative movement <strong>of</strong> an average individual during adult lifespan. The values are existential estimates and subject toerror. 0 - moves less than 100m; 1 - moves 100–1000 m; 2 - moves 1–5 km; 3 - strongly migratory/dispersive.7 - Voltinism, Number <strong>of</strong> complete life cycles per year. S - Univoltine, single generation; B - Bivoltine, two discrete generations;M - Multivoltine, multiple, usually overlapping generations. Months during which adults have been recorded are in parentheses eg(iii–vii).8 - Stage <strong>of</strong> life cycle that diapauses: O - none; E - egg; L - larva; P pupa; A - adult.9 - Span <strong>of</strong> larval food plant (FP) preferences: M - Monophagous, feeds on plant species within one genus; O - Oligophagous, feedson plant genera within one family; P - Polyphagous, feeds on plants in two or more families.10 - Larval food plant families; in cases where the spectrum <strong>of</strong> families is very wide, only two <strong>of</strong> the most important families in thearea are included. For others, reference may be made to Robinson et al. (2001).Throughout the paper, the symbol ? indicates the lack <strong>of</strong> dependable data.PAPILIONIDAE1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101. Troides aeacusFelder & Felder2. Atrophaneuraaidoneus Doubleday03. Byasa dasaradaravana Moore04. Byasa polyeuctesletincius Fruhstorfer05. Byasa latreilleiDonovan06. PachlioptaaristolochiaearistolochiaeFabricius07. Papilio agestorgovindra Moore08. Papilio clytia clytiaLinnaeus09. Papilio protenorprotenor Cramer10. Papilio bianorpolyctor Boisduval11. Papilio parisLinnaeus12. Papilio polytesromulus Cramer13. Papilio demoleusLinnaeus14. Papilio machaonLinnaeus15. Graphium(Pazala)eurous cashmirensisRothschildHimalaya fromGarhwal east toChina and TaiwanHimalaya fromGarhwal east toVietnamHimalaya fromAfghanistan to Indo-ChinaHimalaya fromAfghanistan toVietnamAfghanistan to Chinaand Vietnam.Afghanistan throughIndia to Japan andIndonesia.West Himalaya toIndo-China.India to Malaysia.SM SE R 1 or 2 B: v-vii. ? P O AristolochiaceaeLO SE R 1 or 2?RM/ LO SE O 1 or 2?RM/ LO SE R 1 or 2B: iv-v;vii-viiiB:iv-vi;vii-ix.B: iv-vi;viii-ix? P O Aristolochiaceae?P O Aristolochiaceae?P O AristolochiaceaeSM SE V ? ?B: v; viii. ?P ?O Aristolochiaceae?RM/ NA SR, S O 2/ 3M: i; iii-v;x-xii.? PAristolochiaceae;Dioscoreaceae.NA SE R 0 to 2 S: iii-v. P O LauraceaeNATD,SRO 0 to 2M: iii- viii;x.?P PPakistan to Japan NA SE, S O 1 to 2 M: ii-x. P PPakistan to Indo-China.India to China andS.E. AsiaPakistan throughoutIndia to Indonesia..Iran to China andAustralia.NA SE, S O 1 to 2NA SE, S R 2M: ii-vii;viii-x.M: iii-v;vii; x.Lauraceae,SapotaceaeLauraceae;Rutaceae;Polygalaceae.P O Rutaceae?P O RutaceaeG, NA U A/C 2 M: iii-x. P O RutaceaeG, NA U O 2, 3 M: iii-x. ?P O RutaceaePalaearctic Region G, LO S, G O 0 - 2 M: ii-vii. P O UmbelliferaeWest Himalaya toIndo-China.SM SE V 1 to 2 S: iv-v. P O Lauraceae2860<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2857–2874

Protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones EstateP. Smetacek16. Graphium(Pathysa) nomiusEsper1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1017. Graphium(Graphium) cloanthusWestwood18. Graphium(Graphium) sarpedonLinnaeus19. Graphium(Graphium)agamemnonLinnaeusPIERIDAE20. Leptosia ninaFabricius21. Pontia daplidicemoorei Röber22. Pieris canidiaindica Evans23. Pieris brassicaenipalensis Gray24. Aporia agathonGray25. Delias eucharisDrury26. Delias belladonnahorsfieldii Gray27. Delias acalisGodart28. Anaphaeis aurotaFabricius29. Cepora nerissaphryne Fabricius30. Appias lalagelalage Doubleday31. Catopsiliapomona Fabricius32. Catopsiliapyranthe minnaHerbst33. Gonepteryxrhamni nepalensisDoubleday34. Eurema brigittarubella Wallace35. Eurema laetaBoisduval36. Eurema hecabefimbriata Wallace37. Colias fieldiiMenétries38. Colias erateEsper39. Ixias pyreneLinnaeus40. Ixias marianneCramer41. Pareronia valeriaCramerNYMPHALIDAE42. Parantica agleamelanoides MooreIndia to Thailand.SMTD,SRHimalaya to China NA SE O 1, 2India to Japan andAustralia.India to China andAustralia.India to thePhilippines.V 1, 2 B: iv-v; vii. ? O AnnonaceaeM: iii-vi;viii-x.NA SE O 1, 2 M: ii-x. P PRM SR V 3LOTD,SRPalaearctic. G, NA S, G O 2, 3India to China. G, NA U A 2VOB or M: iiiiv;viii.M: ii-v;ix-xii.M: iii-vii;ix-x; xii.M: i-v; vii;ix-xii.P O Lauraceae? PPalaearctic. G, NA U C 3 M: iii-xi. ?P PLauraceae;AnnonaceaeAnnonaceae;Magnoliaceae; etc? O Capparaceae?P O Cruciferae?P O CruciferaeCruciferae;Resedaceae; etc.Himalaya to China NA SE A 0 to 2 S: iv-vi. ? O BerberidaceaeThroughout IndiaWest Himalaya toChina.Himalaya to Indo-ChinaThroughout India toS.E. AsiaThroughout India toS.E. Asia.Himalaya to Indo-China.Indo-AustralianRegion.Throughout India toS.E. AsiaRMTD,SRO 2 - 3LO SE O 1 to 2M: i-v;x-xii,M: ii-v;viii-x.? PLoranthaceae;Malvaceae; etc.? O LoranthaceaeSM TD V 2 to 3 B: iii-iv; ix. ? ? ?RM SR, S A 3RM SR, S A 3RM ? O 3M: iv-v; viiix;xii.M: iii-iv;vi-xii.M: ii-v; viii;xii.? PCapparaceae;Oleaceae? O Capparaceae? ? LeguminosaeRM U C 3 M: i-xii. ? O LeguminosaeRM U C 3 M: ii-x. ? O LeguminosaePalaearctic Region. NA SE, S O 1 to 2 M: i-xii. A ?PAfrica through Indiato Malaysia.India to Japan andAustralia.African and Indo-Australian RegionsEastern PalaearcticRegionG, NA U A 0 to3 M: i-xii. ? PG, NA U A 0 to ?2M: i; iii-iv;vi-xii.G, NA U C 0 to ?2 M: i-xii. ? PRhamnaceae;EricaceaeLeguminosae;Guttiferae; etc.? O LeguminosaeG, NA SE, G A 3 M: i-xii. ? ? ?Leguminosae;Euphorbiaceae;etc.Palaearctic Region NA SE, G O 3 M: i-xi. ? O LeguminosaeIndia to China. SM S V 3B: ix-x;xii-i.? O CapparaceaeIndia SM S V 3 B: i-iv; xii. ? O CapparaceaeIndia to thePhilippines.Himalaya to S.E.Asia.RMG, NATD,SRSE,TDR 3O 0 to 2M: iii-v;x-xii.M: ii-v;vii-x; xii.? O Capparaceae? O Asclepiadaceae<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2857–28742861

Protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones EstateP. Smetacek1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1072. Melanitis phedimagalkissa Fruhstorfer73. Melanitis ziteniusHerbstIndia to Malaysia.NASE,TD,SRR 0 to 2 M: v-x. ? O GraminaeOriental Region LO TD R 0 to 2 S: viii. ? O Graminae.74. Elymniashypermnestraundularis DruryIndia to Malaysia. LO. SR. R. 0 to 2 M: iv-xi. ? O Palmae75. Elymnias malelasnilamba FruhstorferHimalaya toMalaysia.LO TD R 0 to 2M: iv-v;viii-xi.? ?M Musaceae76. Polyura athamasDruryOriental RegionNASE,TDO 0 to 2 M: iv; vi-x. ? PLeguminosae;Tiliaceae.77. Polyura agrariaSwinhoeOriental RegionNATD,SRR ? B: iv; ix-x. ? ? ?78. Polyura dolonWestwoodHimalayan to S.E.AsiaSM SE V 0 to 2 B: v; ix. ? ? ?79. Dilipa morgianaWestwood80. Apatura(Mimathyma) ambicaambica Kollar81. Sephisa dichroaKollarHimalaya ?SM/LO SE V ?M: iii; v;viii.? ? ?Himalaya ?SM/LO SE V ? M: iv-x. ? M UlmaceaeWest HimalayanendemicLO SE A 0 to 1 M: v-x. ?P M Fagaceae82. Euripus consimilisWestwoodHimalaya to S.E.Asia, S. IndiaLOTD,SRR 0 to 1B: iii-v;vii-ix.? O Ulmaceae83. Hestina persimiliszella ButlerHimalaya LO SE R 1 to 2 M: iii-x. ? O Ulmaceae84. Hestinalis namaDoubleday85. DichorragianesimachusBoisduval86. Stibochiona niceanicea GrayHimalaya toMalaysiaHimalaya to Japanand PhilippinesHimalaya toMalaysia.NASE,TDR 1 to 2M: ii-vi;ix-x.? ? Urticaceae?SM/LO SE V ?1 B: iii-iv; viii. ? O MeliosmaceaeLOSE/TDR 1 to 2M: iv-vii;ix-x.? PMoraceae;Urticaceae.87. Tanaecia juliiappiades MenétriesHimalaya to Indo-ChinaSMTD/SRV ? ?: v. ? ?O Sapotaceae88. Euthalia acontheaHewitsonOriental RegionGTD,SRO 0 to 2M: iii-iv; vivii;x-xi.?P PAnacardiaceae;Moraceae; etc.89. Euthalia lubentinaindica FruhstorferIndia to Malaysia.NATD,SRR 0 to 2M: iii; v;viii, x-xi.? O Loranthaceae90. Euthalia patalapatala KollarWest Himalaya toChinaLO SE O 0 to 2 S: v-viii. P O Fagaceae91. Symphaedra naisForst92. Auzakia danavaMoore93. Moduza procrisprocris Cramer94. Athyma camaMoore95. Athymaselenophoraselenophora Kollar96. Athyma opalinaopalina KollarIndian Subcontinent. SM SR V 0 to 2 ?B: iv; ix. ? PHimalaya toMyanmarIndia to Philippinesand Indonesia.NA SE R 0 to 2M: iv-v;viii; x.? ? ?SM SR V 1 to 2 ?M: iv; x-i. ? PDipteracarpaceae;Ebenaceae.Rubiaceae;Capparaceae.Himalaya NA SE O 0 to 2 M: iv-x. ? ? EuphorbiaceaeIndia to ChinaNATD,SRR 0 to 2 M: ii-vi; xi. ? ? RubiaceaeHimalaya NA SE O 0 to 2 M: iii-xii. P O Berberidaceae97. Athyma periusLinnaeusIndia to China andMalaysia.NA TD O 0 to 2 M: iv-xii. ? O Euphorbiaceae98. Athyma asuraMooreHimalaya. SM SE V ? ?B: vi; viii. ? ? Rubiaceae99. Phaedymacolumella ophianaMooreHimalaya.SMTD,SRV 0 to 2M: iv; vi-vii;xii-i.? PGuttiferae;Leguminosae; etc.100. Neptis natayerburii ButlerIndia to Borneo.LOSE,TD,SRO 0 to 2M: iii- vi;ix-x.? ?P?Ulmaceae;?Combretaceae.<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2857–28742863

Protected fauna <strong>of</strong> Jones EstateP. Smetacek1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10101. Neptis cliniapraedicta Smetacek102. Neptis hylaskamarupa Moore103. Neptis sapphoastola Moore104. Neptis somabutleri Eliot105. Neptis sankarasankara Kollar106. Neptis carticacartica Moore107. Neptis miahvarshneyi Smetacek108. Neptis zaidazaida Westwood109. Neptis anantaMoore110. Pantoporiahordonia hordoniaStoll111. Pantoporiasandaka Moore112. Cyrestisthyodamas ganeschaKollar113. Pseudergoliswedah Kollar114. Hypolimnasbolina Linnaeus115. Hypolimnasmisippus Linnaeus116. Kallima inachushuegeli Kollar117. Junonia hiertahierta Fabricius118. Junonia orithyaLinnaeus119. Junonialemonias persicariaFruhstorfer120. Junonia almanaLinnaeus121. Junonia atlitesLinnaeus122. Junonia iphitasiccata Stichel123. Vanessa carduiLinnaeus124. Vanessa indicaindica Herbst125. Kaniska canacehimalaya EvansIndia to Indo-China.HimalayaPalaearctic Region.LONANATD,SRTD,SRSE,TD,SR, SO 0 to 2O 1 to 2A 0 to 2M: iii-vi;x-xi.M: iii-vi;ix-xi.M: ii-vi;ix-xi.? ?P? P?Bombacaceae;Ulmaceae; etc.Leguminosae;Bombacaceae;etc.? O LeguminosaeIndia to China. LO SE A 0 to 2 M: iii; v-x. ? O UlmaceaeHimalaya to China. LO SE O 0 to 2 B: iv-viii; x. ? ? ?Himalaya.West Himalaya toChina.West Himalaya toChina.Himalaya toMalaysia.Oriental RegionOriental RegionIndia to Japan.LO?SE/?TDLO TD O 0 to 2LOLORMRMNA?SE/?TDSE/TDTD,SRTD,SRSE,TDV ?0 to ?2 S: iv- vi. ? ? ?B: iv-vi;x-xi.? ? ?V 0 to 1 S: v-vii. ? ? ?R 1 to 2O 0 to 2O 0 to 2B: v-vi;viii-x.B: iv-vi;x-xi.B: iv-vi;x-xi.O 0 to 2 M: ii-x. ? ?P? O Lauraceae? O Leguminosae.? ?O Leguminosae.Moraceae;?Dilleniaceae;Himalaya to China. NA SE O 0 to 2 M: iii-ix. ? O Urticaceae.Indo-AustralianRegionAfrican, southernPalaearctic, Oriental,Australian, southernNearctic andnorthern NeotropicalRegionsIndia to ChinaOriental RegionAfrican, Palaearctic,Indo-AustralianRegionsIndia to China andMalaysiaIndia to thePhilippinesRMTD,SRR 2 to 3SM SR V 2 to 3NANANAG, NANASE,TDTD,SR, STD,SR, STD,SR, STD,SR, SM: iii; viixiii.?M: iv;viii-xii.? P? PO 0 to 2 M: iv-x. ? PAcanthaceae;Convolvulaceae;etc.Acanthaceae;Convolvulaceae;etcUrticaceae,Acanthaceae; etc.A 1 to 3 M: iii-viii; x. ? O AcanthaceaeA 1 to 3M: iii-vi; ixx;xii-i.? PA 0 to 2 M: i-xi. ? PO 0 to 2India to Sulawesi NA TD O 0 to 2India to China andMalaysiaNearctic, African,Oriental, Australian,Palaearctic RegionsNASE,TDM: i-vi;ix-x.M: iv-vi;x-xii.? P? PAcanthaceae;Convolvulaceae;etc.Acanthaceae;CannabaceaeAcanthaceae;Graminae; etc.Acanthaceae;Amaranthaceae;etc.A 0 to 2 M: i-x. P O AcanthaceaeNA U A 3 M: i- xi. ? PIndia to S.E. Asia. NA SE A 0 to 3 M: iii-i. ?P PIndia to Malaysia. NA SE O 0 to 2M: I; v-vii;ix-xi;? PUrticaceae,Asteraceae, etc.Urticaceae;Tiliaceae;Ulmaceae.Liliaceae,Smilacaceae,Dioscoreaceae2864<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>August</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(9): 2857–2874