Let f be defined in an interval I. For all x, y in the interval I. If f(x)

Let f be defined in an interval I. For all x, y in the interval I. If f(x)

Let f be defined in an interval I. For all x, y in the interval I. If f(x)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

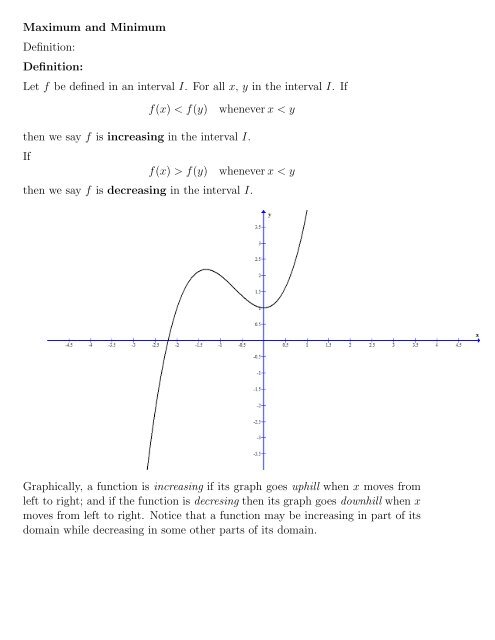

Maximum <strong>an</strong>d M<strong>in</strong>imumDef<strong>in</strong>ition:Def<strong>in</strong>ition:<strong>Let</strong> f <strong>be</strong> <strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I. <strong>For</strong> <strong>all</strong> x, y <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I. <strong>If</strong>f(x) < f(y)whenever x < y<strong>the</strong>n we say f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I.<strong>If</strong>f(x) > f(y) whenever x < y<strong>the</strong>n we say f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I.Graphic<strong>all</strong>y, a function is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g if its graph goes uphill when x moves fromleft to right; <strong>an</strong>d if <strong>the</strong> function is decres<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>n its graph goes downhill when xmoves from left to right. Notice that a function may <strong>be</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> part of itsdoma<strong>in</strong> while decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> some o<strong>the</strong>r parts of its doma<strong>in</strong>.

<strong>For</strong> example, consider f(x) = x 2 .Notice that <strong>the</strong> graph of f goes downhill <strong>be</strong>fore x = 0 <strong>an</strong>d it goes uphill afterx = 0. So f(x) = x 2 is decreas<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>terval (0, ∞).Consider f(x) = s<strong>in</strong> x.f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals (− π 2 , π 2 ), (3π 2 , 5π 2 ), (7π 2 , 9π 2)...etc, while it is decreas<strong>in</strong>gon <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals ( π 2 , 3π 2 ), (5π 2 , 7π 2 ), (9π 2 , 11π2)...etc. In general, f = s<strong>in</strong> x is<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>an</strong>y <strong>in</strong>terval of <strong>the</strong> form ( (2n+1)π2, (2n+3)π2), where n is <strong>an</strong> odd <strong>in</strong>teger.f(x) = s<strong>in</strong> x is decreas<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>an</strong>y <strong>in</strong>terval of <strong>the</strong> form ( (2m+1)π2, (2m+3)π2), where m

is <strong>an</strong> even <strong>in</strong>teger.

What about a const<strong>an</strong>t function? Is a const<strong>an</strong>t function <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g functionor decreas<strong>in</strong>g function? Well, it is like ask<strong>in</strong>g when you walk<strong>in</strong>g on a flat road, asyou go<strong>in</strong>g uphill or downhill? From our def<strong>in</strong>ition, a const<strong>an</strong>t function is nei<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g nor decreas<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>For</strong> a l<strong>in</strong>e y = mx + b, notice that it is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g if its slope is positive, <strong>an</strong>d itis decreas<strong>in</strong>g if its slope is negative. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> derivative of a l<strong>in</strong>e is its slope, wesee that, at least for a l<strong>in</strong>e, if its derivative is positive it is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>an</strong>d if itsderivative is negative it is decreas<strong>in</strong>g. We may wonder if this observation appliesto every function. <strong>If</strong> we observe <strong>the</strong> two functions x 2 <strong>an</strong>d s<strong>in</strong> x we just considered,we see that it is true for <strong>the</strong> two functions also. Our observation leads us to thisfact:<strong>If</strong> f ′ (x) is positive on <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I, <strong>the</strong>n f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on I.<strong>If</strong> f ′ (x) is negative on <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I, <strong>the</strong>n f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g on I.E.g. Consider f(x) = x 3 + 2x 2 + 1. S<strong>in</strong>ce f ′ (x) = 3x 2 + 4x, we see that f ′ (x)is positive on (−∞, − 4 3 ) ∪ (0, ∞) <strong>an</strong>d f ′ (x) is negative on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (− 4 3 , 0).Hence, f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on (−∞, − 4 3 ) ∪ (0, ∞) <strong>an</strong>d f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g on (−4 3 , 0).

We are now ready to def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> maximum <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>in</strong>imum of a function <strong>an</strong>d howto f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>m:Def<strong>in</strong>ition: <strong>Let</strong> f <strong>be</strong> a function. We say that f has <strong>an</strong> absolute maximum (orglobal maximum) at c if f(c) ≥ f(x) for <strong>all</strong> x <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> of f. <strong>If</strong> f has <strong>an</strong>absolute maximum at c, <strong>the</strong>n f(c) is c<strong>all</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> maximum value of f.<strong>Let</strong> f <strong>be</strong> a function. We say that f has <strong>an</strong> absolute m<strong>in</strong>imum (or globalm<strong>in</strong>imum) at c if f(c) ≤ f(x) for <strong>all</strong> x <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> of f. <strong>If</strong> f has <strong>an</strong> absolutem<strong>in</strong>imum at c, <strong>the</strong>n f(c) is c<strong>all</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum value of f.Def<strong>in</strong>ition: <strong>Let</strong> f <strong>be</strong> a function. We say that f has a relative maximum(or local maximum) at c if <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>an</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g c such thatf(c) ≥ f(x) for <strong>all</strong> x <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval.<strong>Let</strong> f <strong>be</strong> a function. We say that f has a relative m<strong>in</strong>imum (or local m<strong>in</strong>imum)at c if <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>an</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g c such that f(c) ≤ f(x) for <strong>all</strong>x <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval.Intuitively, <strong>the</strong> global maximum is <strong>the</strong> largest value of f over its whole doma<strong>in</strong>.<strong>For</strong> example, th<strong>in</strong>k of <strong>the</strong> highest mounta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world (Mount Everest). S<strong>in</strong>ceMount Everest is <strong>the</strong> highest mounta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong>re’s no o<strong>the</strong>r mounta<strong>in</strong>that’s t<strong>all</strong>er, so Mount Everest is a global maximum. Now consider <strong>the</strong> Rockymounta<strong>in</strong>. The Rocky Mounta<strong>in</strong> is not <strong>the</strong> t<strong>all</strong>est mounta<strong>in</strong> glob<strong>all</strong>y. However, ifwe just consider <strong>the</strong> state of Colorado, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> Rocky Mounta<strong>in</strong> is <strong>the</strong> highestmounta<strong>in</strong> with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> state of Colorado. That is, loc<strong>all</strong>y with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> state of Colorado,<strong>the</strong> Rocky Mounta<strong>in</strong> is <strong>the</strong> maximum, so <strong>the</strong> Rocky Mounta<strong>in</strong> is a localmaximum.

The graph of <strong>the</strong> above function has a local m<strong>in</strong>imum, a local maximum <strong>an</strong>d also<strong>the</strong> global maximum, but <strong>the</strong> function does not have a global m<strong>in</strong>imum.

The graph of <strong>the</strong> above function has a local <strong>an</strong>d global m<strong>in</strong>imum, <strong>an</strong>d a local<strong>an</strong>d global maximum

The graph of <strong>the</strong> above function has no maximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum of <strong>an</strong>y k<strong>in</strong>dThe local maximum appears on <strong>the</strong> graph of a function as a peak (<strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong>mounta<strong>in</strong>), while <strong>the</strong> loc<strong>all</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum appears on <strong>the</strong> graph of a function as av<strong>all</strong>ey.Notice that <strong>an</strong>y global max is also a local max. (<strong>If</strong> you are <strong>the</strong> t<strong>all</strong>est person <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> world, you must <strong>be</strong> <strong>the</strong> t<strong>all</strong>est person with<strong>in</strong> your neighborhood.) On <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>rh<strong>an</strong>d, if you are <strong>the</strong> t<strong>all</strong>est person with<strong>in</strong> your neighborhood, you may not<strong>be</strong> <strong>the</strong> t<strong>all</strong>est person <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world. Therefore, a local maximum is not necessarilya global maximum.An import<strong>an</strong>t po<strong>in</strong>t to note is that a local maximum with<strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong> open <strong>in</strong>tervalmight not necessarily <strong>be</strong> larger th<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r po<strong>in</strong>t that is not a local maximum.Notice also that a function does not have to have <strong>an</strong>y global or local maximum,or global or local m<strong>in</strong>imum.

Example: f(x) = 3x + 4f has no local or global max or m<strong>in</strong>.Examplef(x) = x 2 − 4x + 4f has a global (<strong>the</strong>refore also local) m<strong>in</strong>imum at x = 2. M<strong>in</strong>imum value of f isf(2) = 0.

Example: f(x) = x 3 + 2x 2 + xf has a local maximum at x = −1 <strong>an</strong>d a local m<strong>in</strong>imum at x = − 1 3Localmaximum value of f is f(−1) = 0. Local m<strong>in</strong>imum value of f is f(− 1 3 ) = − 4 27 .Example: f(x) = s<strong>in</strong> xf has global (local) maxima at π 2 , 5π 2 , 9π 2, ... Maximum value of f is 1 f has global(local) m<strong>in</strong>ima at 3π 2 , 7π 2 , 11π2, ... M<strong>in</strong>imum value of f is -1

From <strong>the</strong> example of s<strong>in</strong> x we see that, while <strong>the</strong>re is only one value for a globalmaximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum, such value c<strong>an</strong> <strong>be</strong> achieved at m<strong>an</strong>y different x values.<strong>For</strong> s<strong>in</strong> x, <strong>the</strong> maximum value is 1. That me<strong>an</strong>s <strong>the</strong> value of s<strong>in</strong> x never exceeds1. However, <strong>the</strong>re are (<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itely) m<strong>an</strong>y x’s for which s<strong>in</strong> x = 1. Th<strong>in</strong>k of it thisway: <strong>Let</strong> say <strong>the</strong> t<strong>all</strong>est hum<strong>an</strong> <strong>be</strong><strong>in</strong>g is 3 meters t<strong>all</strong>, which me<strong>an</strong>s no hum<strong>an</strong><strong>be</strong><strong>in</strong>g c<strong>an</strong> <strong>be</strong> t<strong>all</strong>er th<strong>an</strong> 3 meters. However, <strong>the</strong>re c<strong>an</strong> <strong>be</strong> more th<strong>an</strong> one personat 3 meters t<strong>all</strong>.Example: f(x) = x2x−1f has local maximum at x = 0. Local maximum value of f is f(0) = 0.f has local m<strong>in</strong>imum at x = 2. Local m<strong>in</strong>imum value of f is f(2) = 4.This example shows that a local m<strong>in</strong>imum may have a value that is greater th<strong>an</strong>a local maximum. In <strong>the</strong> example, <strong>the</strong> local maximum value of f is 0, while <strong>the</strong>local m<strong>in</strong>imum value of f is 4. This is perfectly f<strong>in</strong>e. The import<strong>an</strong>t po<strong>in</strong>t hereis that <strong>the</strong>se are local m<strong>in</strong>imum or local maximum. They are only largest (orsm<strong>all</strong>es) with<strong>in</strong> a conf<strong>in</strong>ed doma<strong>in</strong>. You may <strong>be</strong> <strong>the</strong> t<strong>all</strong>est person <strong>in</strong> your family,but you may <strong>be</strong> shorter th<strong>an</strong> <strong>the</strong> shortest NBA player.Consider<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> derivative is a rate of ch<strong>an</strong>ge, we saw that if a functionis go<strong>in</strong>g uphill (<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g), <strong>the</strong>n its derivative is positive, <strong>an</strong>d if <strong>the</strong> function isgo<strong>in</strong>g downhill, <strong>the</strong>n its derivative is negative. What if <strong>the</strong> function is at <strong>the</strong> peak(local maximum) or v<strong>all</strong>ey (local m<strong>in</strong>imum)? What should <strong>be</strong> <strong>the</strong> derivative of afunction at a local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imum? Well, if you are go<strong>in</strong>g uphill youare <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g (positive derivative), if you are go<strong>in</strong>g downhill you are decreas<strong>in</strong>g(negative derivative). It makes sense that if you reached <strong>the</strong> peak (maximum)or v<strong>all</strong>ey (m<strong>in</strong>imum) that you are nei<strong>the</strong>r mov<strong>in</strong>g up or down, <strong>the</strong>n you arestationary. i.e, your rate of ch<strong>an</strong>ge is 0. This is <strong>in</strong>deed <strong>the</strong> case:Fermat’s Theorem: <strong>If</strong> f has local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imum at c, <strong>an</strong>d f isdifferentiable at c, <strong>the</strong>n f ′ (c) = 0.

This <strong>the</strong>orem says that if a function has a local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imumat a po<strong>in</strong>t c, <strong>the</strong>n its t<strong>an</strong>gent at that po<strong>in</strong>t (if it has a t<strong>an</strong>gent) must <strong>be</strong> ahorizontal l<strong>in</strong>e. (Slope is 0). We saw that this is true with <strong>all</strong> <strong>the</strong> examplesabove. Intuitively, s<strong>in</strong>ce you are at <strong>the</strong> peak or v<strong>all</strong>ey, you are nei<strong>the</strong>r mov<strong>in</strong>g upor down, so your velociy (rate of ch<strong>an</strong>ge) must <strong>be</strong> 0.It is import<strong>an</strong>t to note that what <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>orem says is that if f has a local maximumor local m<strong>in</strong>imum at c <strong>an</strong>d f ′ (c) exists <strong>the</strong>n it must <strong>be</strong> 0. The <strong>the</strong>orem doesnot say that if f ′ (c) = 0, <strong>the</strong>n f has a local maximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum at c. It ispossible that f ′ (c) = 0 but that c is nei<strong>the</strong>r a local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imumvalue for f. Consider this example:<strong>Let</strong> f(x) = x 3 . Notice that f ′ (x) = 3x 2 , so f ′ (0) = 0. However, f has nei<strong>the</strong>r amaximum nor m<strong>in</strong>imum at 0. f just happen to have a horizontal t<strong>an</strong>gent at thatparticular po<strong>in</strong>t.Notice also that <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>orem does not say <strong>an</strong>yth<strong>in</strong>g about c if f is not differentiableat c. It is possible that f may have a local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imum atc but that f ′ (c) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>, as <strong>the</strong> next example illustrates:f(x) = |x|. f ′ (0) does not exist (f has a sharp corner <strong>the</strong>re), however x = 0 is alocal m<strong>in</strong>imum of f.

This example shows that even if f ′ (c) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>, f may still have a localm<strong>in</strong>imum or local maximum at c. In general, <strong>the</strong> local maxima or m<strong>in</strong>ima of afunction occurs only <strong>in</strong> locations where <strong>the</strong> derivative of a function is equal to 0(f ′ (0)) or if <strong>the</strong> derivative is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>.

Def<strong>in</strong>ition:<strong>Let</strong> a num<strong>be</strong>r c <strong>be</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> of f. (That me<strong>an</strong>s f(c) exists). c is c<strong>all</strong>ed acritical num<strong>be</strong>r of f if f ′ (c) = 0 or if f ′ (c) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>.What <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition says is that <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of a function occurs wheref has a horizontal t<strong>an</strong>gent (f ′ (c) = 0) or when f is not differentiable at c, likewhen f has a sharp corner.Example: f(x) = (x − 2) 2f has a critical num<strong>be</strong>r at 2 s<strong>in</strong>ce f ′ (2) = 0.Example: f(x) = x 2/3f has a critical num<strong>be</strong>r at 0 <strong>be</strong>cause f ′ (0) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>Fermat’s Theorem tells us that if f has a local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imum atc, <strong>an</strong>d if f is differentiable at c, <strong>the</strong>n its derivative must <strong>be</strong> 0. We also saw fromexample that f could have a local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imum at c if f ′ (c) isun<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>. From <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition of critical num<strong>be</strong>rs, we saw that:<strong>If</strong> f has a local maximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imum at c, <strong>the</strong>n c is a cirtical num<strong>be</strong>r off.This gives us a way to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> local m<strong>in</strong>ima <strong>an</strong>d local maxima of a function.(Actu<strong>all</strong>y, we c<strong>an</strong> only f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> c<strong>an</strong>didates for <strong>the</strong> local m<strong>in</strong>ima <strong>an</strong>d local maximaof a function at this moment. We will see later how we c<strong>an</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>e if <strong>the</strong>c<strong>an</strong>didate are local maxima, local m<strong>in</strong>ima, or nei<strong>the</strong>r.)To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> local maxima <strong>an</strong>d local m<strong>in</strong>ima of a function f, take <strong>the</strong> derivativeof <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong> function, f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f. (That is, f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts cwhere f ′ (c) is equal to 0 or f ′ (c) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>.) The critical num<strong>be</strong>rs are <strong>the</strong>c<strong>an</strong>didates for <strong>the</strong> local maxima or m<strong>in</strong>ima of f. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs coccurs only when <strong>the</strong> derivative of f is equal to 0 or is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong> at c, this me<strong>an</strong>sthat, algebraic<strong>all</strong>y, to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> maxima <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>in</strong>ima of a function f, we first f<strong>in</strong>df ′ , <strong>the</strong>n set f ′ to 0 to solve for <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts c where f ′ (c) = 0. We also look for<strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts where f ′ is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>. These are <strong>the</strong> c<strong>an</strong>didate for local maxima <strong>an</strong>dlocal m<strong>in</strong>ima.Note that I have <strong>be</strong>en emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs are only c<strong>an</strong>didatefor local maxima <strong>an</strong>d local m<strong>in</strong>ima. This me<strong>an</strong>s that even if f has a criticalnum<strong>be</strong>r at c, it does not necessarily me<strong>an</strong> that <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r is a localmaximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum. But if we were to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>an</strong>y local maxima or local m<strong>in</strong>imaof f, we must f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs first.

Example: f(x) = x2x−1F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of fTo f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f, we must take its derivative <strong>an</strong>d set it equal to0.f ′ (x) = x2 − 2x(x − 1) 2Sett<strong>in</strong>g f ′ (x) = 0 <strong>an</strong>d solv<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> equation we have:x 2 − 2x(x − 1) 2 = 0Notice that <strong>the</strong> left h<strong>an</strong>d side is a fraction. A fraction is equal to 0 if <strong>an</strong>d only ifits numerator is equal to 0, sox 2 − 2x(x − 1) 2 = 0 ⇔ x2 − 2x = 0 ⇔ x = 0 or x = 2So f has two cirtical num<strong>be</strong>rs, x = 0 <strong>an</strong>d x = 2. f has a horizontal t<strong>an</strong>gent at<strong>the</strong>se two po<strong>in</strong>ts.How about <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t x = 1, where f ′ (1) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>? Even though f ′ is not<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong> at x = 1, but s<strong>in</strong>ce f(1) is also not <strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>. x = 1 is not <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong>of f, so we do not consider x = 1 as a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of f. However, x = 1 is avertical asymptote of f <strong>an</strong>d later when we consider <strong>the</strong> graph of f, know<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> vertical asymptote of a function will help us <strong>be</strong>tter graph a function.What are <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs 0 <strong>an</strong>d 2? Are <strong>the</strong>y local maximum, local m<strong>in</strong>imum,or nei<strong>the</strong>r? From <strong>the</strong> graph of f we know that f has a local maximum at x = 0<strong>an</strong>d a local m<strong>in</strong>imum at x = 2. We will see later how we c<strong>an</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>e if acritical po<strong>in</strong>t is a local maximum, local m<strong>in</strong>imum, or nei<strong>the</strong>r without <strong>the</strong> graph.

The above function is cont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>in</strong>side a closed <strong>in</strong>terval. It satisfies <strong>the</strong> extremevalue <strong>the</strong>orem.Some functions fail to have a maximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum <strong>in</strong>side a closed <strong>in</strong>terval<strong>be</strong>cause <strong>the</strong>y are not cont<strong>in</strong>uous, <strong>an</strong>d a cont<strong>in</strong>uous function may not have amaximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum if its doma<strong>in</strong> is not conf<strong>in</strong>ed with<strong>in</strong> a closed <strong>in</strong>terval.The above function is discont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval from −5 to 6, it does nothave <strong>an</strong>y global max or m<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>side that <strong>in</strong>terval.

The above function is cont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval (−3, 3), but it does nothave <strong>an</strong>y global m<strong>in</strong> or max <strong>in</strong>side this open <strong>in</strong>terval.To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> global maximum <strong>an</strong>d global m<strong>in</strong>imum of a cont<strong>in</strong>uous function f<strong>in</strong>side a closed <strong>in</strong>terval [a, b], we need to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>all</strong> <strong>the</strong> local maximum <strong>an</strong>d localm<strong>in</strong>imum of <strong>the</strong> function, <strong>an</strong>d also f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> values of <strong>the</strong> function at <strong>the</strong> boundarypo<strong>in</strong>ts (that is, f<strong>in</strong>d f(a) <strong>an</strong>d f(b). The largest of <strong>the</strong> values is <strong>the</strong> globalmaximum <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> sm<strong>all</strong>est of <strong>the</strong> values is <strong>the</strong> global m<strong>in</strong>imum.Example: F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> global maximum <strong>an</strong>d global m<strong>in</strong>imum of f(x) = x 3 − 3x + 1on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval [0, 3].We first f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>all</strong> <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f, as <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>the</strong> c<strong>an</strong>didates for localmaximum <strong>an</strong>d local m<strong>in</strong>imum:Sett<strong>in</strong>g derivative to 0 we get:f ′ (x) = 3x 2 − 33x 2 − 3 = 0 ⇒ x = ±1The critical po<strong>in</strong>ts of f are x = 1 <strong>an</strong>d x = −1. However, s<strong>in</strong>ce −1 is not <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>terval [0, 3], we do not consider it. The only three po<strong>in</strong>ts we need to considerare (1, f(1)), (0, f(0)), <strong>an</strong>d (3, f(3)). x = 1 is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of f, <strong>an</strong>d x = 0<strong>an</strong>d x = 3 are <strong>the</strong> boundary po<strong>in</strong>ts. S<strong>in</strong>ce f(0) = 1, f(1) = −1, <strong>an</strong>d f(3) = 19,we see that f(3) = 19 is <strong>the</strong> largest value among <strong>the</strong> three, so f(3) = 19 is <strong>the</strong>global maximum value, <strong>an</strong>d f(1) = −1 is <strong>the</strong> global m<strong>in</strong>imum value.Notice that if we ch<strong>an</strong>ged <strong>the</strong> closed <strong>in</strong>terval on which <strong>the</strong> function is <strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>, wemay have different global maximum <strong>an</strong>d global m<strong>in</strong>imum. <strong>For</strong> example, for <strong>the</strong>above functions, if we ch<strong>an</strong>ged <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals to [−3, 2] <strong>in</strong>stead, <strong>the</strong>n both critical

po<strong>in</strong>ts, x = −1 <strong>an</strong>d x = 1, should <strong>be</strong> considered. And <strong>the</strong> four po<strong>in</strong>ts we needto consider are (−3, f(−3)), (−1, f(−1)), (1, f(1)), <strong>an</strong>d (2, f(2)). x = −1 <strong>an</strong>dx = 1 are critical po<strong>in</strong>ts, while x = −3 <strong>an</strong>d x = 2 are boundary po<strong>in</strong>ts. Inthis case, s<strong>in</strong>ce f(−3) = −17 is <strong>the</strong> sm<strong>all</strong>est value among <strong>the</strong> four, −17 is <strong>the</strong>global m<strong>in</strong>imum value. Notice that both f(2) <strong>an</strong>d f(−1) are equal to 3 <strong>an</strong>d is<strong>the</strong> largest value among <strong>the</strong> four, so 3 is <strong>the</strong> global maximum value, <strong>an</strong>d thisvalue is achieved by f on two different x values.What does it help to <strong>be</strong> able to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> global maximum <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>in</strong>imum valuesof a function only with<strong>in</strong> a conf<strong>in</strong>ed doma<strong>in</strong> (a closed <strong>in</strong>terval)?In ma<strong>the</strong>matics, where most functions take on <strong>the</strong> whole real l<strong>in</strong>e as its doma<strong>in</strong>,or at least <strong>an</strong> unbounded subset of <strong>the</strong> real l<strong>in</strong>e, to <strong>be</strong> able to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> maximumor m<strong>in</strong>imum of a function over only a bounded <strong>in</strong>terval is not too practical.However, <strong>in</strong> most applications, where <strong>the</strong> functions are used to model real worldphenomenom, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> of <strong>the</strong> functions are more th<strong>an</strong> often bounded bysome physical constra<strong>in</strong>. <strong>For</strong> example, a function might <strong>be</strong> used to model <strong>the</strong>profit of a factory <strong>in</strong> terms of its production level. In which case <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong>of <strong>the</strong> function c<strong>an</strong>not <strong>be</strong> negative num<strong>be</strong>rs (it doesn’t make sense to producenegative m<strong>an</strong>y products), <strong>an</strong>d most likely due to limitations on market dem<strong>an</strong>dor labor, or raw material, <strong>the</strong> production level will not exceed too high a volumeei<strong>the</strong>r. In <strong>an</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r example, notice that if we have V = 4πr33, <strong>the</strong>n as a function ofr, <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> of V is <strong>all</strong> real num<strong>be</strong>rs. However, if <strong>the</strong> formula is used to model<strong>the</strong> volume of a sphere that we w<strong>an</strong>t to build <strong>in</strong> a space ship, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> physicalconstra<strong>in</strong> limits that r must <strong>be</strong> positive <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong>not <strong>be</strong> too large.When a function is used to model a physical phenomenom, <strong>the</strong> physical constra<strong>in</strong>usu<strong>all</strong>y puts some artificial boundary on <strong>the</strong> function. In which case it does makesense to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> global maximum <strong>an</strong>d global m<strong>in</strong>imum of a function with<strong>in</strong> aclosed <strong>in</strong>terval. This idea will <strong>be</strong> useful to us when we consider <strong>the</strong> applications

of f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g maximum <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>in</strong>imum. <strong>For</strong> example, one might w<strong>an</strong>t to know <strong>the</strong>production level that would maximize profit, or <strong>the</strong> dimension of a box thatwould maximize volume...etc.

The Me<strong>an</strong> Value TheoremConsider this scenerio: you are go<strong>in</strong>g from S<strong>an</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>cisco to Sacremento. <strong>Let</strong>ssay you started your trip at 12:00 Midnight, <strong>an</strong>d you reached your dest<strong>in</strong>ation at2:00am, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> dist<strong>an</strong>ce of your trip is 100 miles.What is your average velocity over <strong>the</strong> trip? It took you 2 hours to travel 100miles, so your average velocity is 100 = 50 miles per hour. Does this me<strong>an</strong> that2you were always driv<strong>in</strong>g at 50 mph <strong>in</strong> <strong>all</strong> 2 hours of your trip? Probably not. Youmay <strong>be</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g faster at some time, <strong>an</strong>d may <strong>be</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g slower at some o<strong>the</strong>rtime. However, one po<strong>in</strong>t is clear: s<strong>in</strong>ce your average velocity is 50 miles perhour over <strong>the</strong> trip, <strong>the</strong>re must <strong>be</strong> at least one <strong>in</strong>st<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> trip at which youare driv<strong>in</strong>g at exactly 50 miles per hour. After <strong>all</strong>, if you are always driv<strong>in</strong>g at<strong>be</strong>low 50 mph, <strong>the</strong>re’s no way you could average a 50 mph velocity (s<strong>in</strong>ce youwill <strong>be</strong> too slow), so you must speed up to a faster velocity. <strong>If</strong> you were to speedup to higher th<strong>an</strong> 50 mph, dur<strong>in</strong>g your speed<strong>in</strong>g up, <strong>the</strong>re must <strong>be</strong> a po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong>which you will <strong>be</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g at exactly 50 mph <strong>be</strong>fore you c<strong>an</strong> speed up to, say 60mph or some faster speed.This <strong>an</strong>alogy gives us <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>be</strong>h<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> me<strong>an</strong> value <strong>the</strong>orem, which says that:if <strong>the</strong> average rate of ch<strong>an</strong>ge of a differentiable funtion over a given <strong>in</strong>terval isequal to a particular num<strong>be</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re must <strong>be</strong> some po<strong>in</strong>t with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval

<strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>st<strong>an</strong>t<strong>an</strong>eous rate of ch<strong>an</strong>ge of that function is exactly equal tothat num<strong>be</strong>r.

The Me<strong>an</strong> Value Theorem <strong>Let</strong> f <strong>be</strong> a function such that f is cont<strong>in</strong>uous on<strong>the</strong> closed <strong>in</strong>terval [a, b], <strong>an</strong>d that f is differentiable on <strong>the</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval (a, b),<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re exists a num<strong>be</strong>r c <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval (a, b) (i.e. a < c < b) suchthat:f ′ f(b) − f(a)(c) =b − af(b) − f(a)In <strong>the</strong> equation of <strong>the</strong> Me<strong>an</strong> Value Theorem, <strong>the</strong> fraction on <strong>the</strong> rightb − ah<strong>an</strong>d side is <strong>the</strong> slope of <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> end po<strong>in</strong>ts of <strong>the</strong> function over<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval. That is, it is <strong>the</strong> slope of <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts (a, f(a))<strong>an</strong>d (b, f(b)). It represents <strong>the</strong> average rate of ch<strong>an</strong>ge of <strong>the</strong> function over <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>terval (a, b). The expression f ′ (c) is <strong>the</strong> slope of a t<strong>an</strong>gent l<strong>in</strong>e to f at somepo<strong>in</strong>t c. It represents <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>st<strong>an</strong>t<strong>an</strong>eous rate of ch<strong>an</strong>ge of f at po<strong>in</strong>t c. The Me<strong>an</strong>Value Theorem says that <strong>an</strong>y function f that is differentiable over <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervalmust have a po<strong>in</strong>t c <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval such that <strong>the</strong> derivative of f at c, f ′ (c),is equal to <strong>the</strong> slope of <strong>the</strong> sec<strong>an</strong>t l<strong>in</strong>e conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts of f at <strong>the</strong> two endpo<strong>in</strong>ts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval.The me<strong>an</strong> value <strong>the</strong>orem is what we c<strong>all</strong> <strong>an</strong> exist<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>orem. That is, it tellsyou that someth<strong>in</strong>g exists without tell<strong>in</strong>g you how to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>m. In fact, whilewe know that if f satisfies such a condition <strong>the</strong>n such a c must exists, we donot know how to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> value of c. Sometimes it may <strong>be</strong> possible or even easyto f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> c that works, but sometimes it may <strong>be</strong> extremely difficult or even

impossible to f<strong>in</strong>d such a c. Imag<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> situation we mentioned <strong>be</strong>fore, that youtravelled 100 miles <strong>in</strong> 2 hours, so you know that your average velocity over <strong>the</strong> 2hours is 50 miles per hour. You also know that you must <strong>be</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g at exactly50 mph at some po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> your trip. However, if I ask you exactly when were youdriv<strong>in</strong>g at 50 mph <strong>in</strong> your tirp? You probably c<strong>an</strong>not easily <strong>an</strong>swer this question.Example:<strong>Let</strong> f(x) = x 2 − 3x + 4. Consider f <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval [2, 5]. Notice that f isdifferentiable <strong>in</strong> [2, 5], so <strong>the</strong> Me<strong>an</strong> Value Theorem says that <strong>the</strong>re is a po<strong>in</strong>t c<strong>be</strong>tween 2 <strong>an</strong>d 5 such thatf ′ (c) =f(5) − f(2)5 − 2= 4To solve for c, we take <strong>the</strong> derivative of f <strong>an</strong>d set it equal to 4:f ′ (x) = 2x − 3Sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> derivative equal to 4 we get:2x − 3 = 4 ⇒ x = 7 2 = 3.5Notice that 3.5 is <strong>in</strong>deed <strong>be</strong>tween 2 <strong>an</strong>d 5.

We know that <strong>the</strong> derivative of a const<strong>an</strong>t function is equal to zero. Is <strong>the</strong>converse of this statement true? That is, if a function f has a derivative of zero,does this necessarily me<strong>an</strong> that f is a const<strong>an</strong>t function?Theorem:<strong>If</strong> f is a differentiable function such that f ′ (x) = 0 for <strong>all</strong> x <strong>in</strong>side <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval(a, b), <strong>the</strong>n f is a const<strong>an</strong>t function <strong>in</strong> (a, b)Proof: <strong>Let</strong> r < t <strong>be</strong> <strong>an</strong>y two num<strong>be</strong>rs <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> open <strong>in</strong>terval (a, b). The me<strong>an</strong>value <strong>the</strong>orem tells us that <strong>the</strong>re exists a num<strong>be</strong>r, say s, where r < s < t, suchthat:f ′ f(t) − f(r)(s) =t − rBut f ′ (s) = 0 s<strong>in</strong>ce s is <strong>in</strong>side (a, b), sof(t) − f(r)= 0 ⇒ f(t) − f(r) = 0 ⇒ f(t) = f(r)t − rThis shows that if f ′ (x) = 0 for <strong>all</strong> x <strong>in</strong>side (a, b), <strong>the</strong>n f(t) = f(r) for <strong>an</strong>y r, t<strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (a, b). In o<strong>the</strong>r words, f(x) is a const<strong>an</strong>t function <strong>in</strong>side (a, b)

Graph<strong>in</strong>gIn order to draw <strong>the</strong> graph of a function f accurately, we need to know much<strong>in</strong>formation about <strong>the</strong> function. The derivatives of a function gives us <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>formation.We already saw that <strong>the</strong> local maxima <strong>an</strong>d local m<strong>in</strong>ima of a functionmust occur at critical num<strong>be</strong>rs. We also saw that on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f ′ ispositive, f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g; <strong>an</strong>d f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g where f ′ is negative. What else c<strong>an</strong>we f<strong>in</strong>d out about a function from its derivatives.We saw that we could f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of a function f, but we have yetto learn how to classify <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs. How do we determ<strong>in</strong>e if a criticalnum<strong>be</strong>r is a local maximum, a local m<strong>in</strong>imum, or nei<strong>the</strong>r?<strong>Let</strong> f <strong>be</strong> a function with a critical num<strong>be</strong>r at c. Suppose that f ′ is positive <strong>be</strong>forereaches c, <strong>an</strong>d that f ′ is negative after pass<strong>in</strong>g c. This me<strong>an</strong>s that f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g<strong>be</strong>fore reach<strong>in</strong>g c, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>n f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g after pass<strong>in</strong>g c.Observe from <strong>the</strong> graph that f must have a local maximum at that po<strong>in</strong>t. <strong>If</strong> youwere climb<strong>in</strong>g a mounta<strong>in</strong> <strong>be</strong>fore reach<strong>in</strong>g some po<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>the</strong>n you start descend<strong>in</strong>gafter reach<strong>in</strong>g that po<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>the</strong>n you must have reached <strong>the</strong> peak of <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>.Therefore, if f ′ ch<strong>an</strong>ges sign from + to − upon cross<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r c,<strong>the</strong>n f must have a local maximum at c.

Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> same logic we see that if ′ ch<strong>an</strong>ges sign from − to + upon cross<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>critical num<strong>be</strong>r c, <strong>the</strong>n f must have local m<strong>in</strong>imum at c.What if f ′ does not ch<strong>an</strong>ge sign upon cross<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r c? <strong>Let</strong>’s sayf ′ is positive <strong>be</strong>fore c, <strong>an</strong>d f ′ is also positive after c. <strong>If</strong> you are climb<strong>in</strong>g amounta<strong>in</strong> <strong>be</strong>fore reach<strong>in</strong>g some po<strong>in</strong>t on a mounta<strong>in</strong>, <strong>an</strong>d you are still climb<strong>in</strong>gafter reach<strong>in</strong>g that po<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>the</strong>n that po<strong>in</strong>t c<strong>an</strong>not <strong>be</strong> <strong>the</strong> peak of <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>(o<strong>the</strong>rwise you will have to start descend). So if f ′ does not ch<strong>an</strong>ge sign at <strong>the</strong>critical po<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> critical po<strong>in</strong>t c<strong>an</strong>not <strong>be</strong> a local maximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum.The function simply has a horizontal or vertical t<strong>an</strong>gent at that po<strong>in</strong>t.

The above discussion gives us <strong>the</strong> First Derivative Test:<strong>Let</strong> c <strong>be</strong> a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of a cont<strong>in</strong>uous function f,if f ′ ch<strong>an</strong>ges sign from positive to negative at c, <strong>the</strong>n f has a local maximum atc.if f ′ ch<strong>an</strong>ges sign from negative to positive at c, <strong>the</strong>n f has a local m<strong>in</strong>imum atc.if f ′ does not ch<strong>an</strong>ge sign at c, <strong>the</strong>n f(c) is nei<strong>the</strong>r a local maximum nor m<strong>in</strong>imum.Example:<strong>Let</strong> f(x) = x 3 + 4x 2 − 3x + 1. F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>all</strong> <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f <strong>an</strong>d classify<strong>the</strong>m as local maximum, local m<strong>in</strong>imum, or nei<strong>the</strong>r. Also determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervalswhere f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g.To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f, we must first take <strong>the</strong> derivative <strong>an</strong>d set itequal to zero:f ′ (x) = 3x 2 + 8x − 33x 2 + 8x − 3 = 0 ⇒ (3x − 1)(x + 3) = 0 ⇒ x = 1 3or x = −3We have two critical num<strong>be</strong>rs, x = −3 <strong>an</strong>d x = 1 3. What we need to do is we

w<strong>an</strong>t to consider <strong>the</strong> value of f ′ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals separated by <strong>the</strong>se two num<strong>be</strong>rs.In particular, we need to consider <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals (−∞, −3), (−3, 1 3 ), <strong>an</strong>d (1 3 , ∞).In order to f<strong>in</strong>d out how f ′ ch<strong>an</strong>ges sign at <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs, we pick <strong>an</strong>ypo<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> sign of f ′ <strong>in</strong> that <strong>in</strong>terval:−4 is <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−∞, −3), f ′ (−4) = 13 > 0, so f ′ is positive <strong>be</strong>fore −3,which me<strong>an</strong>s f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−∞, −3).0 is <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−3, 1 3 ), f ′ (0) = −3 < 0, so f ′ is negative <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval,which me<strong>an</strong>s f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−3, 1 3 ).Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first derivative test, we know that f has a local maximum at x = −3.1 is <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval ( 1 3 , ∞), f ′ (1) = 8 > 0, so f ′ is it positive after 1 3 , whichme<strong>an</strong>s f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval ( 1 3 , ∞).Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first derivative test, we know that f has a local m<strong>in</strong>imum at x = 1 3 .We c<strong>an</strong> summarize <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> a table like this:Intervals (−∞, −3) −3 (−3, 1 3 ) 1( 1 3 3 , ∞)f ↗ local max ↘ local m<strong>in</strong> ↗f ′ + 0 − 0 +

Example:F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f(x) = x 3 − 2 <strong>an</strong>d determ<strong>in</strong>e if <strong>the</strong>y are localm<strong>in</strong>imum, local maximum, or nei<strong>the</strong>r. Also determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f is<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g.As usual we f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> derivative of f <strong>an</strong>d set it equal to 0 to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> criticalnum<strong>be</strong>rs.f ′ (x) = 3x 2Sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> derivative equal to zero we get:3x 2 = 0 ⇒ x = 0So f have a critical num<strong>be</strong>r at x = 0. This divides <strong>the</strong> real l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>to two <strong>in</strong>tervals(−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d (0, ∞). f ′ (−1) = 1 > 0, so f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−∞, 0),<strong>an</strong>d f ′ (1) = 1 > 0, so f is also <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (0, ∞). Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> firstderivative test, we see that x = 0 is nei<strong>the</strong>r a local maximum or m<strong>in</strong>imum.Intervals (−∞, 0) 0 (0, ∞)f ↗ horizontal t<strong>an</strong>gent ↗f ′ + 0 +

Example:F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f(x) = x 2/3 <strong>an</strong>d determ<strong>in</strong>e if <strong>the</strong>y are local m<strong>in</strong>imum,local maximum, or nei<strong>the</strong>r. Also determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g<strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g.f ′ (x) = 2 3 x−1/3 = 23 3 √ xNotice that f ′ (0) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>, but f(0) = 0 is <strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>, so x = 0 is a criticalnum<strong>be</strong>r of f. We consider <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals (−∞, 0), (0, ∞). S<strong>in</strong>ce f ′ is negative <strong>in</strong>(−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d positive <strong>in</strong> (0, ∞), we know that f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g on (−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on (0, ∞). The first derivative test tells us that f has a local m<strong>in</strong>imumat 0.Intervals (−∞, 0) 0 (0, ∞)f ↘ local m<strong>in</strong> ↗f ′ − un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong> (sharp corner) +

How about <strong>the</strong> second derivative? What c<strong>an</strong> we tell about a function f from itssecond derivative?Suppose you are driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> one direction on <strong>the</strong> highway. <strong>Let</strong> s(t) represent <strong>the</strong>dist<strong>an</strong>ce you are from your dest<strong>in</strong>ation as a function of time t. <strong>Let</strong>’s consider twodifferent situations:Situation 1:Suppose you have travelled 30 miles for <strong>the</strong> first hour. So s(1) = 30. And let’ssay you are driv<strong>in</strong>g at 40 mph at t = 1. This me<strong>an</strong>s s ′ (t) = 40. Suppose thatat <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>st<strong>an</strong>ce t = 1 you are accelerat<strong>in</strong>g. Remem<strong>be</strong>r that acceleration is <strong>the</strong>ch<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>in</strong> velocity. S<strong>in</strong>ce you are accelerat<strong>in</strong>g this me<strong>an</strong>s s ′′ (t) > 0. S<strong>in</strong>ce youaccelerate, you will <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> velocity. <strong>Let</strong>’s say you <strong>in</strong>creased your velocity <strong>all</strong><strong>the</strong> way to 50 mph. Then <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> next hour you will <strong>be</strong> able to cover more groundsth<strong>an</strong> you did <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first hour. <strong>Let</strong>’s say you travelled 45 miles <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second hour.So for <strong>the</strong> first two hours you travelled a total of 75 miles. Therefore, s(2) = 75.Situation 2:Suppose you have travelled 30 miles for <strong>the</strong> first hour. So s(1) = 30. And let’ssay you are driv<strong>in</strong>g at 40 mph at t = 1. This me<strong>an</strong>s s ′ (t) = 40. Suppose thatat <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>st<strong>an</strong>ce t = 1 you are decelerat<strong>in</strong>g. Remem<strong>be</strong>r that acceleration is <strong>the</strong>ch<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>in</strong> velocity. S<strong>in</strong>ce you are decelerat<strong>in</strong>g this me<strong>an</strong>s s ′′ (t) < 0. S<strong>in</strong>ce youdecelerate, you will decrease <strong>in</strong> velocity. <strong>Let</strong>’s say you decreased your velocity <strong>all</strong><strong>the</strong> way down to 20 mph. Then <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> next hour you will not <strong>be</strong> able to coveras much ground as you did <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first hour. <strong>Let</strong>’s say you travelled 25 miles<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second hour. So for <strong>the</strong> first two hours you travelled a total of 55 miles.Therefore, s(2) = 55.Notice that <strong>in</strong> both of <strong>the</strong> two situations, your velocity at time t = 1 is <strong>the</strong>same at 40 mph. However, whe<strong>the</strong>r you decelerate or accelerate (whe<strong>the</strong>r s ′′ (t)is positive or negative) makes a difference <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> shape of <strong>the</strong> graph of s. In <strong>the</strong>case when you accelerate, <strong>the</strong> graph of s lies above <strong>the</strong> t<strong>an</strong>gent l<strong>in</strong>e at t = 1. In

<strong>the</strong> case when you decelerate, <strong>the</strong> graph of s lies <strong>be</strong>low <strong>the</strong> t<strong>an</strong>gent l<strong>in</strong>e at t = 1.This tells us someth<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>the</strong> graph of <strong>the</strong> function: whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> graph of<strong>the</strong> function lies above or <strong>be</strong>low its t<strong>an</strong>gent l<strong>in</strong>es is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> secondderivative of <strong>the</strong> function.Def<strong>in</strong>ition:<strong>If</strong> <strong>the</strong> graph of a function f lies above <strong>all</strong> of its t<strong>an</strong>gent l<strong>in</strong>es on <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I, <strong>the</strong>nf is said to <strong>be</strong> concave up on I. <strong>If</strong> <strong>the</strong> graph of f lies <strong>be</strong>low <strong>all</strong> of its t<strong>an</strong>gentl<strong>in</strong>es, <strong>the</strong>n f is said to <strong>be</strong> concave down on I.The above is a function that concaves upsThe above is a function that concaves downGraphic<strong>all</strong>y, a function concave up will shape like a U shape, while a concavedown function shape like a N shape. Notice that just like a function might <strong>be</strong><strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g at some <strong>in</strong>terval <strong>an</strong>d decreas<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>an</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>terval, <strong>the</strong> function mightalso <strong>be</strong> concave up at some <strong>in</strong>terval while concave down at o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>tervals.Def<strong>in</strong>ition:

A po<strong>in</strong>t P on a function f is c<strong>all</strong>ed a po<strong>in</strong>t of <strong>in</strong>flection of f if <strong>the</strong> concavityof f ch<strong>an</strong>ges at P . That is, if f goes from concave up to concave down or if fgoes from concave down to concave up upon cross<strong>in</strong>g P .

To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts of a function, we will need to know at which valuesof x does <strong>the</strong> second derivative ch<strong>an</strong>ges sign. We f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r of <strong>the</strong>first derivative. That is, we f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts where <strong>the</strong> second derivative of <strong>the</strong>function is equal to 0 or un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>. These po<strong>in</strong>ts give us <strong>the</strong> c<strong>an</strong>didate for <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts of f. We will see examples shortly.As we saw from our <strong>an</strong>alysis, a function concaves up <strong>be</strong>cause its second derivativeis positive, a function concaves down <strong>be</strong>cause its second derivative is negative.When a functions has a positive second derivative, that me<strong>an</strong>s <strong>the</strong> function’s firstderivative is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>If</strong> a function has a negative second derivative, that me<strong>an</strong>s<strong>the</strong> function’s first derivative is decreas<strong>in</strong>g. Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g as <strong>an</strong> example, ifyou are accelerat<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> graph of your dist<strong>an</strong>ce verses time will <strong>be</strong> concaveup. <strong>If</strong> you are decelerat<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> graph of your dist<strong>an</strong>ce verses time will <strong>be</strong>concave down.Concavity Test <strong>If</strong> f ′′ (x) > 0 <strong>in</strong>side <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I, <strong>the</strong>n f is concave up on I.<strong>If</strong> f ′′ (x) < 0 <strong>in</strong>side <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I, <strong>the</strong>n f is concave down on I.E.g. In a research study, it is shown that <strong>in</strong> High School A, <strong>the</strong> average scores of<strong>the</strong> student body over <strong>the</strong> past 5 years are:Year score1999 602000 702001 772002 812003 83The average score of High School B over <strong>the</strong> same five years are given by:Year score1999 502000 532001 602002 682003 80

Score Verses Years<strong>If</strong> you are look<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>the</strong> results of <strong>the</strong>se test scores, which school is do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>be</strong>tter?Both schools’ scores are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g over time (positive derivative), but school Ahas higher scores th<strong>an</strong> school B every year. Does this me<strong>an</strong> that school A is do<strong>in</strong>g<strong>be</strong>tter th<strong>an</strong> school B? Notice that even though school A has higher scores over<strong>the</strong> years, <strong>the</strong> scores are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g slower <strong>an</strong>d slower, which me<strong>an</strong>s <strong>the</strong> scores hasa negative second derivative. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>an</strong>d, even though school B has lowerscores over <strong>the</strong> years, <strong>the</strong> scores are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g faster <strong>an</strong>d faster, which me<strong>an</strong>sschool B has a positive second derivative. <strong>If</strong> <strong>the</strong> trend cont<strong>in</strong>ues, school B willout-score school A very soon.What else does <strong>the</strong> second derivative tell us about <strong>the</strong> function f? Suppose fhas a critical num<strong>be</strong>r at a po<strong>in</strong>t c, <strong>the</strong>n we know that c is a c<strong>an</strong>didate for a localmaximum or local m<strong>in</strong>imum of f. <strong>If</strong> f ′′ (c) < 0. This me<strong>an</strong>s f is concave downat <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r c. We have a U-shaped graph at c. From <strong>the</strong> shape of <strong>the</strong>graph we c<strong>an</strong> see that f must have a local maximum at c.<strong>If</strong> c is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of f <strong>an</strong>d f ′′ (c) > 0, <strong>the</strong>n this me<strong>an</strong>s that f is concaveup at <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r c. We have a N-shaped graph at c. From <strong>the</strong> shape of<strong>the</strong> graph we see that f must have a local mimimum at c.The above discussion give us <strong>the</strong> Second Derivative Test:<strong>If</strong> c is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of f <strong>an</strong>d f ′′ (c) > 0, <strong>the</strong>n f has a local m<strong>in</strong>imum at c.<strong>If</strong> c is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of f <strong>an</strong>d f ′′ (c) < 0, <strong>the</strong>n f has a local maximum at c.

<strong>If</strong> c is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of f <strong>an</strong>d f ′′ (c) = 0 or f ′′ (c) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> testfails.Person<strong>all</strong>y I prefer <strong>the</strong> first derivative test over <strong>the</strong> second derivative test totest <strong>the</strong> critical po<strong>in</strong>ts. The reason <strong>be</strong><strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> first derivative test is alwaysconclusive. i.e <strong>the</strong> first derivative test c<strong>an</strong> always tell us if a critical po<strong>in</strong>t is alocal max, a local m<strong>in</strong>, or nei<strong>the</strong>r. The second derivative test, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>an</strong>d,fails when <strong>the</strong> second derivative is equal to 0 or un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong> at <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r.

Example:Consider f(x) = x 3 . f ′ (x) = 3x 2 , so f has a critical num<strong>be</strong>r at x = 0. S<strong>in</strong>cef ′′ (x) = 6x, f ′′ (0) = 0 so we c<strong>an</strong>not use <strong>the</strong> second derivative test to tell us<strong>an</strong>yth<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r 0. Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first derivative test, though, wesee that f ′ is positive <strong>be</strong>fore 0 <strong>an</strong>d positive after 0, so 0 is nei<strong>the</strong>r a maximumnor m<strong>in</strong>imum.Now consider f(x) = x 4 . f ′ (x) = 4x 3 , so f has a critical num<strong>be</strong>r at x = 0. S<strong>in</strong>cef ′′ (x) = 12x 2 , f ′′ (0) = 0 so we c<strong>an</strong>not use <strong>the</strong> second derivative test to tell us<strong>an</strong>yth<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>r 0. Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first derivative test, though, wesee that f ′ is negative <strong>be</strong>fore 0 <strong>an</strong>d positive after 0, so f has a local m<strong>in</strong>imum at0 (it turns out that this is also a global m<strong>in</strong>imum).

Example:<strong>Let</strong> f(x) = x 3 . F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts of f if <strong>the</strong>re’s <strong>an</strong>y, <strong>an</strong>d determ<strong>in</strong>e onwhich <strong>in</strong>tervals is f concave up <strong>an</strong>d on which <strong>in</strong>tervals is f concave down.To determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts of <strong>in</strong>flection of f, we must f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rsof <strong>the</strong> first derivative (<strong>the</strong> num<strong>be</strong>rs where <strong>the</strong> second derivative is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong> orequal to 0) to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> c<strong>an</strong>didate for <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts:S<strong>in</strong>ce f ′ (x) = 3x 2 , so f ′′ (x) = 6x, which me<strong>an</strong>s x = 0 is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of <strong>the</strong>first derivative <strong>an</strong>d f ′′ (0) = 0. Notice that on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−∞, 0) f ′′ is negative,while f ′′ is positive on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (0, ∞). Therefore, f is concave down on(−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d concave up on (0, ∞). S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> concavity of f ch<strong>an</strong>ges at 0, (0, 0)is <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t of f.We use a table similar to <strong>the</strong> ones we used to <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong> relationship:Intervals (−∞, 0) 0 (0, ∞)f concave down 0 concave upf ′′ − <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t +

Example:<strong>Let</strong> f(x) = x 5/3 . F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts of f if <strong>the</strong>re’s <strong>an</strong>y, <strong>an</strong>d determ<strong>in</strong>e onwhich <strong>in</strong>tervals is f concave up <strong>an</strong>d on which <strong>in</strong>tervals is f concave down.We f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong> first derivative of f.f ′ (x) = 5 3 x2/3 , so f ′′ (x) = 109 x−1/3 = 109 3√ . x = 0 is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of <strong>the</strong>xfirst derivative <strong>be</strong>cause f ′′ (0) is un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>. S<strong>in</strong>ce f ′′ is negative <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval(−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d f ′′ is positive <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (0, ∞), we know that f concaves downon (−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d f concaves up on (0, ∞). S<strong>in</strong>ce f ch<strong>an</strong>ges concavity at 0, (0, 0)is <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t.Intervals (−∞, 0) 0 (0, ∞)f concave down 0 concave upf ′′ − <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t +

E.g.<strong>Let</strong> f(x) = x 4 . F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts of f if <strong>the</strong>re’s <strong>an</strong>y, <strong>an</strong>d determ<strong>in</strong>e onwhich <strong>in</strong>tervals is f concave up <strong>an</strong>d on which <strong>in</strong>tervals is f concave down.f ′ (x) = 4x 2 <strong>an</strong>d f ′′ (x) = 8x, so x = 0 is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> first derivatives<strong>in</strong>ce f ′′ (0) = 0. Notice that f ′′ is positive on <strong>the</strong> whole real l<strong>in</strong>e, which me<strong>an</strong>sf is always concave up. So even though x = 0 is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> firstderivative, x = 0 is not <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t of f.Intervals (−∞, 0) 0 (0, ∞)f concave up 0 concave upf ′′ + 0 +

Example: f(x) = x2 −1x 2 +1F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f <strong>an</strong>d determ<strong>in</strong>e if <strong>the</strong>y are local maximum or localm<strong>in</strong>imum, or nei<strong>the</strong>r. Determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>tervals where f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g. F<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts of f if <strong>the</strong>re’s <strong>an</strong>y.Determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f concaves up <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f concavesdown. Sketch <strong>the</strong> graph of f us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>formation.To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f we must take <strong>the</strong> first derivative:f ′ (x) = (x2 + 1)(2x) − (x 2 − 1)(2x)(x 2 + 1) 2 =4x(x 2 + 1) 2We see that f ′ is zero only if x = 0, so x = 0 is a critical num<strong>be</strong>r.f ′ is negative on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d positive on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (0, ∞), so f isdecreas<strong>in</strong>g on (−∞, 0) <strong>an</strong>d <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on (0, ∞). Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first derivative testwe know that f has a local m<strong>in</strong>imum at 0.To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals where f concaves up or down <strong>an</strong>d to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flectionpo<strong>in</strong>ts, we must take <strong>the</strong> second derivative:f ′′ (x) = (x2 + 1) 2 (4) − 4x(2(x 2 + 1)(2x))(x 2 + 1) 4= (x2 + 1)(4(x 2 + 1) − 16x 2 )(x 2 + 1) 4= 4(x2 + 1) − 16x 2(x 2 + 1) 3= 4x2 + 4 − 16x 2(x 2 + 1) 3= −12x2 + 4(x 2 + 1) 3We set <strong>the</strong> second derivative equal to zero to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> c<strong>an</strong>didate for <strong>in</strong>flectionpo<strong>in</strong>ts:−12x 2 + 4(x 2 + 1) 3 = 0 ⇔ −12x 2 + 4 = 0 ⇔ x = ± 1 √3So x = − 1 √3<strong>an</strong>d x = 1 √3are <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong> first derivative, whichme<strong>an</strong>s <strong>the</strong>y are c<strong>an</strong>didate for <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts.f ′′ < 0 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (−∞, − 1 √3), so f concaves down on this <strong>in</strong>terval.f ′′ > 0 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval (− 1 √3, 1 √3), so f concaves up on this <strong>in</strong>terval.

This also tells us that f has <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t at − 1 √3s<strong>in</strong>ce it ch<strong>an</strong>ges concavityat this po<strong>in</strong>tf ′′ < 0 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval ( 1 √3, ∞), so f concaves down on this <strong>in</strong>terval.This tells us that f has <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t at 1 √3s<strong>in</strong>ce it ch<strong>an</strong>ges concavity atthis po<strong>in</strong>tWe c<strong>an</strong> summarize <strong>all</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> a table like this:Intervals (−∞, − √ 1 3) − √ 1 3(− √ 1 3, 0) 01(0, √3 ) √3 1( √ 1 3, ∞)f ↘ & C.D. I.P. ↘ & C.U. L M<strong>in</strong> ↗ & C.U I.P. ↗ & C.Df ′ − − − 0 + + +f ′′ − 0 + + + 0 −<strong>Let</strong> us summarize <strong>the</strong> facts we learned about first <strong>an</strong>d second derivatives so far:<strong>If</strong> f ′ is positive on <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I, f is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g on I. <strong>If</strong> f ′ is negative on <strong>an</strong><strong>in</strong>terval I, f is decreas<strong>in</strong>g on I.<strong>If</strong> f ′′ is positive on <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>terval I, f is concave up on I. <strong>If</strong> f ′ is negative on <strong>an</strong><strong>in</strong>terval I, f is concave down on I.To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> local maxima <strong>an</strong>d local m<strong>in</strong>ima of f, f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f.That is, f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> values c where f ′ (c) is zero or un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>. Use <strong>the</strong> first or secondderivative test to test if <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs are local maximum, local m<strong>in</strong>imum,or nei<strong>the</strong>r.To f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>ts of f, f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> critical num<strong>be</strong>rs of f ′ . That is, f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>the</strong> values c where f ′′ (c) is zero or un<strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong>. <strong>If</strong> f ′′ ch<strong>an</strong>ges sign at c, <strong>the</strong>n f has<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>flection po<strong>in</strong>t at c.

Limits at Inf<strong>in</strong>itySo far we have studied <strong>the</strong> limit of a function f only at a particular num<strong>be</strong>r c.What if we w<strong>an</strong>t to study <strong>the</strong> long term <strong>be</strong>havior of a function f? That if, whatc<strong>an</strong> we tell about a function f(x) when <strong>the</strong> values of x <strong>be</strong>come tremendouslylarge (x → ∞) or tremendously negative (x → −∞)?<strong>Let</strong>’s look at <strong>the</strong> <strong>be</strong>havior of <strong>the</strong> functionwhen x <strong>be</strong>comes very large:f(x) = x − 1x + 1x f(x)1000 0.99810000 0.9998100000 0.999981000000 0.99999810000000 0.9999998As we c<strong>an</strong> see, <strong>the</strong> value of f approaches 1 as <strong>the</strong> value of x gets larger <strong>an</strong>d larger.We use <strong>the</strong> notation:to denote this fact.x − 1limx→∞ x + 1 = 1The me<strong>an</strong><strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> limit says that, <strong>the</strong> value of f approaches 1 as x approaches

<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity. As we already said, <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity is not a num<strong>be</strong>r. So when we say x approaches<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity, we are not say<strong>in</strong>g that x approaches <strong>an</strong>y particular num<strong>be</strong>r.When we say x approaches <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity, we are say<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> value of x <strong>in</strong>creaseswithout bound.What happens to <strong>the</strong> function f if x approaches negative <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity? That is, whathappens when <strong>the</strong> values of x decreases without bound? We make a similar tablelike <strong>the</strong> one above:x f(x)−1000 1.002−10000 1.0002−100000 1.00002−1000000 1.000002−10000000 1.0000002So f approaches 1 as x decreases without bound. We use <strong>the</strong> notation:to denote this fact.x − 1limx→−∞ x + 1 = 1Once aga<strong>in</strong>, when we say x approaches negative <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity, we me<strong>an</strong>t x decreaseswithout bound. We are not suggest<strong>in</strong>g that x approaches <strong>an</strong>y particular num<strong>be</strong>r.Def<strong>in</strong>ition:We use <strong>the</strong> notationlim f(x) = Lx→∞to me<strong>an</strong> that, when <strong>the</strong> value of x grows without bound, <strong>the</strong> value of f(x) approaches<strong>the</strong> num<strong>be</strong>r L.We use similar notation for negative <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity:lim f(x) = Lx→−∞to me<strong>an</strong> that, when <strong>the</strong> value of x decreases without bound, <strong>the</strong> value of f(x)approaches <strong>the</strong> num<strong>be</strong>r L.<strong>If</strong> <strong>the</strong> value of f approaches a particular num<strong>be</strong>r L when x approaches <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity(or negative <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity), <strong>the</strong> graph of f looks like a horizontal l<strong>in</strong>e.Def<strong>in</strong>ition:The horizontal l<strong>in</strong>e y = L is c<strong>all</strong>ed a horizontal asymptote of f iflim f(x) = L or lim f(x) = Lx→∞ x→−∞So <strong>the</strong> function we just considered, f(x) = x−1x+1, has a horizontal asymptote y = 1.

<strong>If</strong> a function has a horizontal asymptote y = L at <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity, that me<strong>an</strong>s f rema<strong>in</strong>spretty much at a const<strong>an</strong>t value of L.E.g. Suppose you are a biologist, <strong>an</strong>d you predict that <strong>the</strong> population P of aparticular species will <strong>in</strong>crease or decrease as a function of time accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>follow<strong>in</strong>g formula:P (t) = 100t2 − t + 1t 2 + 1P has a horizontal asymptote of y = 100. This me<strong>an</strong>s that, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> long run, <strong>the</strong>population of <strong>the</strong> species will rema<strong>in</strong> at about 100.How do we f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> limit of a function at <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity? <strong>Let</strong> us see some simple cases:1limx→∞ xAs x gets tremendously large, we are divid<strong>in</strong>g 1 by a tremendously large num<strong>be</strong>r,<strong>the</strong> result is a num<strong>be</strong>r very close to zero.1limx→∞ x = 0In general, whenever we have a const<strong>an</strong>t divided by <strong>an</strong> expression that keeps ongrow<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> result is always zero. We state a slightly simplerversion here:<strong>If</strong> r > 0 <strong>an</strong>d c is a const<strong>an</strong>t <strong>the</strong>nlimx→∞cx r = 0This makes sense <strong>be</strong>cause, s<strong>in</strong>ce r >, as x approaches <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity, x r approaches<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity, <strong>an</strong>d when you divide a const<strong>an</strong>t by someth<strong>in</strong>g that is tremendously large,<strong>the</strong> result is a num<strong>be</strong>r that is very close to 0.<strong>If</strong> r > 0, <strong>an</strong>d r is a rational num<strong>be</strong>r, <strong>an</strong>d c is a const<strong>an</strong>t <strong>the</strong>nclimx→∞ x = 0 rif x r is <strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed</strong> for negative num<strong>be</strong>rs xE.gEvaluatex 3 − 4x 2 + x − 1limx→∞ −2x 3 + x + 5In this case here, both <strong>the</strong> numerator <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> denom<strong>in</strong>ator goes to <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity as xgrows without bound. In order to evaluate this limit form<strong>all</strong>y, we need to express<strong>the</strong> fraction <strong>in</strong> terms that we c<strong>an</strong> evaluate <strong>the</strong> value when x approaches <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ity.

The trick here is to divide <strong>the</strong> numerator <strong>an</strong>d denom<strong>in</strong>ator by <strong>the</strong> highest powerof x. In this example here, we divide <strong>the</strong> numerator <strong>an</strong>d denom<strong>in</strong>ator by x 3 :x 3 − 4x 2 + x − 1limx→∞ −2x 3 + x + 5x 3 −4x 2 +x−1x 3x→∞ −2x 3 +x+5= limx 3= limx→∞1 − 4 x + 1 x 2 − 1 x 3−2 + 1 x 2 + 5 x 3As x → ∞, <strong>all</strong> <strong>the</strong> expressions that have a const<strong>an</strong>t on <strong>the</strong> numerator <strong>an</strong>d x to apower <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> denom<strong>in</strong>ator will <strong>be</strong>come 0, <strong>an</strong>d this <strong>all</strong>ows us to evaluate <strong>the</strong> limit:=== limx→∞1 − 4 x + 1 x 2 − 1 x 3−2 + 1 x 2 + 5 x 3lim(1 − 4x→∞ x + 1 x − 1 )2 x(−2 3 + 1 x + 5 )2 x 3limx→∞lim 1 − lim 4x→∞ x→∞x + limx→∞lim −2 + limx→∞ x→∞1x 2 − limx→∞1x 2 + limx→∞= 1 − 0 + 0 − 0−2 + 0 + 0= − 1 2There is a easier, though less formal method to solve a limit problem of thissort. Notice that <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> above limit, both <strong>the</strong> numerator <strong>an</strong>d denom<strong>in</strong>ator arepolynomials. We c<strong>an</strong> argue that when x <strong>be</strong>comes tremendously large, <strong>the</strong> highestpower of x <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> polynomial will dom<strong>in</strong>ate. Consider <strong>the</strong> polynomial f(x) =x 3 − 4x 2 + x − 1. When <strong>the</strong> value of x <strong>be</strong>comes tremendously large, <strong>the</strong> x 3 termis go<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>be</strong> much larger th<strong>an</strong> <strong>the</strong> −4x 2 term <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> x term. i.e,5x 3x 3 − 4x 2 + x − 1 ≈ x 3 as x → ∞Similarly, as x <strong>be</strong>comes tremendously large,−2x 3 + x + 5 ≈ x 3 as − 2x 3 → ∞1x 3