Paper Tobago Wastewater Study (2).pdf - Caribbean Environment ...

Paper Tobago Wastewater Study (2).pdf - Caribbean Environment ...

Paper Tobago Wastewater Study (2).pdf - Caribbean Environment ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

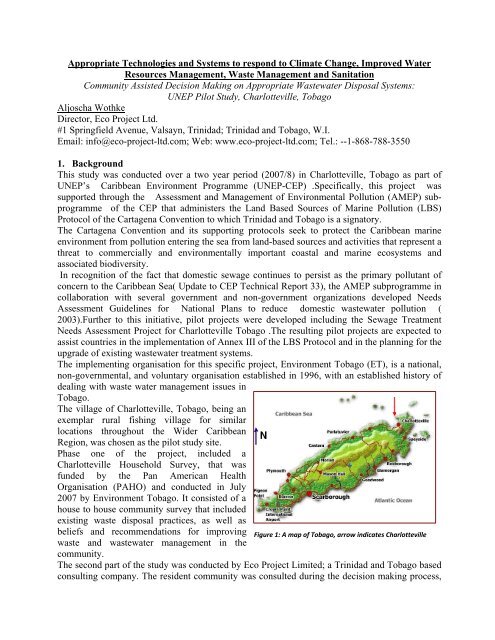

Appropriate Technologies and Systems to respond to Climate Change, Improved WaterResources Management, Waste Management and SanitationCommunity Assisted Decision Making on Appropriate <strong>Wastewater</strong> Disposal Systems:UNEP Pilot <strong>Study</strong>, Charlotteville, <strong>Tobago</strong>Aljoscha WothkeDirector, Eco Project Ltd.#1 Springfield Avenue, Valsayn, Trinidad; Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong>, W.I.Email: info@eco-project-ltd.com; Web: www.eco-project-ltd.com; Tel.: --1-868-788-35501. BackgroundThis study was conducted over a two year period (2007/8) in Charlotteville, <strong>Tobago</strong> as part ofUNEP’s <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>Environment</strong> Programme (UNEP-CEP) .Specifically, this project wassupported through the Assessment and Management of <strong>Environment</strong>al Pollution (AMEP) subprogrammeof the CEP that administers the Land Based Sources of Marine Pollution (LBS)Protocol of the Cartagena Convention to which Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong> is a signatory.The Cartagena Convention and its supporting protocols seek to protect the <strong>Caribbean</strong> marineenvironment from pollution entering the sea from land-based sources and activities that represent athreat to commercially and environmentally important coastal and marine ecosystems andassociated biodiversity.In recognition of the fact that domestic sewage continues to persist as the primary pollutant ofconcern to the <strong>Caribbean</strong> Sea( Update to CEP Technical Report 33), the AMEP subprogramme incollaboration with several government and non-government organizations developed NeedsAssessment Guidelines for National Plans to reduce domestic wastewater pollution (2003).Further to this initiative, pilot projects were developed including the Sewage TreatmentNeeds Assessment Project for Charlotteville <strong>Tobago</strong> .The resulting pilot projects are expected toassist countries in the implementation of Annex III of the LBS Protocol and in the planning for theupgrade of existing wastewater treatment systems.The implementing organisation for this specific project, <strong>Environment</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong> (ET), is a national,non-governmental, and voluntary organisation established in 1996, with an established history ofdealing with waste water management issues in<strong>Tobago</strong>.The village of Charlotteville, <strong>Tobago</strong>, being anexemplar rural fishing village for similarlocations throughout the Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong>Region, was chosen as the pilot study site.Phase one of the project, included aCharlotteville Household Survey, that wasfunded by the Pan American HealthOrganisation (PAHO) and conducted in July2007 by <strong>Environment</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>. It consisted of ahouse to house community survey that includedexisting waste disposal practices, as well asbeliefs and recommendations for improvingwaste and wastewater management in thecommunity.Figure 1: A map of <strong>Tobago</strong>, arrow indicates CharlottevilleThe second part of the study was conducted by Eco Project Limited; a Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong> basedconsulting company. The resident community was consulted during the decision making process,

low income households. Many of the septic tanks are in areas that are not accessible for sewagetrucks.• The general population is neither willing nor has the means to install and consistently maintainhousehold based septic systems.• The total length of the required sewage systems was calculated at approximately 6000 m.• Water samples taken during the study and analysed by the Water and Sewage Authority showedfaecal coliform concentrations 65 times above permissible levels at the river mouth and 43 timesat the near shore area (Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong> <strong>Environment</strong>al Management Act).• The existing sewage treatment and waste water disposal systems are totally inadequate, pose anoverall environmental threat and health risks to the residents and visitors.3. Centralised VS Decentralised Sewage Treatment SolutionThe consultants were of the principal opinion that well designed, well maintained, decentralised,household based systems can fulfil most requirements of Annex III of the LBS Protocol and aswell meet EcoSan principles, especially in rural areas of developing countries, and as such are avery viable alternative solution for many SIDS in the WCR.Domestic pre- composting systems, for example the “rottebehaelter” offer excellent alternatives,are easy to install, relatively affordable, recycle nutrients, have low or no energy consumption andcan be installed in conjunction with water saving toilet flush systems (some of them are describedin “A Directory of <strong>Environment</strong>ally Sound Technologies for the Integrated Management of Solid,Liquid and Hazardous Waste for SIDS in the <strong>Caribbean</strong> Region, a UNEP/ CEHI publication).It is highly recommended that the decision between centralised versus decentralised wastewatertreatment system must be taken separately for each specific site, taking cultural, economic andphysical conditions very seriously into account.Therefore the advantages and disadvantages of a small – scale, centralised and a household based,decentralised approach specifically for the Collette River Basin were compared.This comparison was evaluated under the specific socio – economic and cultural conditions of thestudy area, the most important ones are:• Cultural acceptance• The healthy economical status of Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong>• The general low household income• Effluent quality• Applicableness for community based tourismParameter Decentralised, HouseholdBased System ~ 1000 PEOverall Implementation Cost ~ USD 600,000 to 1,450.000depending on technologyVillage Based CentralisedSystem ~ 1000 PE~ USD 2,800,000 to3,200,000 depending ontechnologyImplementation Cost / ~ USD 2,500 to 6,000 ~ USD 11,700 - 13,350HouseholdCost per Household Ratio Stagnant Decreases when number ofconnected householdsincreasesCost to the Public Sector Minimal Government bears all costsAffordable for the Public n/a yes

SectorCost to the Home Owner Home owner bears all costs MinimalAffordable for the Majority of Non/aHome OwnersInstallation of Sewer System Not required RequiredPlanning and Installation Time Short, only where actually Long, must be able providerequiredfor the entire communityEnergy Consumption Very low medium to highCorruption Issue Does not invite corruption Has a potential to invitecorrupt practicesCommunity / Cultural Very limitedHighAcceptanceCultural Acceptance to Very lown/aMaintainNeed for Awareness Building, Very highMediumTrainingEffluent Quality Low HighEffluent Quality Monitoring Not practical Very viableApplicable to Guesthouses / NoYesRestaurants / YachtsReuse of Effluent for LimitedVery viableIrrigationCreates Employment Yes NoNutrient RecyclingDepending on maintenance by Very goodControlled Composting andSale of Fertiliser, CostRecoverySpace Requirementhome ownerNoMostly needs additionaltreatment in wetlandsTable 1: Summary on evaluation parameters to compare decentralised, household ‐ based wastewater treatment systems witha small, village – based, centralised wastewater treatment system. Critical, decision making parameters are marked in yellow(Cost valid for Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong>)Based on the above evaluation, the consultants suggested a centralised, small scale seweragetreatment system in the specific case of the Collette River Basin, for the following reasons:i. The stakeholders and community agreed on such a system.ii. Upgraded, nutrient recycling, decentralised systems would not be culturally accepted inCharlotteville.iii. Homeowners would not bear the costs for the installation and maintenance of decentralisedsystems; furthermore they would not be willing to monitor and service such systems themselves.iv. The Government of Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong> should be able to afford a small scale centralisedsystem.v. A centralised system is able to provide wastewater treatment services to the tourism industry.vi. A centralised system can be controlled and the quality of effluent and sludge treatmentmonitored.YesLow

4. Sewerage Treatment Design PremisesThe following wastewater treatment plant design premises were set:• Minimal space requirement• Minimal or no odour emissions.• The effluent from the plant must meet and / or exceed the Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong> Bureau ofStandard specifications, the guidelines of Annex III of the LBS Protocol and the permissible levelsof the <strong>Environment</strong>al Management Act (Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong>), 2000, The Water Pollution Rules,2001, Arrangement of Rules.• The plant should allow nutrient recovery; trucking of liquid waste and / or sludge must beavoided.• The plant should use an aerobic process• Low energy and water consumption• Cost effective O&M, to be performed by trained, communitybased personnel.• Plant should be upgradeable from 60m³ to 250m³Based on these premises the Advanced Sequential BatchReactor (SBR) technology was chosen as the mostappropriate technology.5. LocationDuring the several site visits the consultants discussed variousoptions for the location of a plant with residents and otherstakeholders.The crucial factors were:i. The housing density in the Collette River Basin is Figure 4: Ledge on Pirates Bay Road thathigh, especially at the bottom of the valley, close to could be cut, to provide space for the futurethe river mouth; this would normally be a preferred sewage treatment plantlocation for a mostly gravity fed collection andtreatment plantii. Any location in the higher parts of thevalley would require consistent pumping,using high amounts of energy andrequiring frequent pump maintenance andreplacement.iii. The acquisition of private property shouldbe avoided.iv. The nearest distance to the next dwellingshould exceed 50m.A ledge at the Pirates Bay Road, between BelleAir Street andPirates Bay, approximately 75m away from thenearest dwelling, was pre – chosen by the consultants and later on confirmed by the communitycouncil.Figure 5: Elevation of sewage treatment building afterSince the road sides are government property constructionthe issue of land ownership was addressed aswell.

6. Selection of Technology ProvidersVarious providers were contacted and three of those were short listed, one Trinidad and twointernationally based suppliers.The Trinidad supplier was able to propose a key ready, 2 - tank, conventional SBR, includingconstruction costs for approximately USD 800,000.00One international (Dutch) supplier also proposed a 2 – tank conventional SBR (USD 400,000.00),the other international (Austrian) supplier proposed a 10 – tank, advanced SBR (USD 808,000.00)both excluding construction costs.Additionally to the international proposals contractors from <strong>Tobago</strong> were asked to quote for thecivil construction part. Depending on the size of the plant, construction costs varied between USD450,000.00 to USD 500,000.00.The three suppliers were evaluated and despite the higher implementation cost, but at the sametime looking at the economic prosperity of Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong>, the approach of the Austriabased supplier was considered the most appropriate technology mainly because:• The only supplier that has experience in and offered nutrient recovery and fertiliser production• Completely enclosed system and odour free operations• Income generation through sales of fertiliser• Low operational costs• Modular system• Lowest energy consumption• Best effluent water quality• Modular system, is expandable from 60m³/d to 250m³/d• Easy maintenance, light parts, separated tanks can be maintained in sequence• Meets 7 out of 9 effluent standards• The only supplier that seemed to have perused the tender documents thoroughlyThe recommended system was presented to and approved by the Charlotteville CommunityCouncil.7. Stakeholder ParticipationThroughout the project community leaders, the community council, other community members,and stakeholders were actively involved in data gathering and the decision making process; threecommunity meetings were held and the final decision approved by the members of the communitycouncil which, in the same letter requested and expansion of the project to include the entirevillage of Charlotteville and urging the implementing agencies to take further action.During the first meeting in early December 2007, the project was formally introduced to thecommunity, its objectives explained and preliminary designs and locations were suggested.The results of the previous Charlotteville Household Survey, and the recent water tests werepresented and the audience was deeply concerned about the sanitary status of their waters.Despite initial reservations and mistrust in the usual procedures, the residents expressed theirsatisfaction with the proposed designs. The pivoting factor to gain the community’s buy – in wasthat the consultants assured that they would recommend to the funding agency and / orimplementing governmental body that three community leaders should visit a similar STP beforethe Community Council would be asked for its final approval.

With the assistance of the president of the community council, all churches and schools wereinformed about the follow up meetings on the 8 th and 23 rd of January 2008. Posters were placed atmini – markets, bus stations and rum – shops. The local radio station, was announcing the meetingfor two days prior.The project, its rationale, goal and proposed approach were again and in more depth presented tothe Charlotteville Community Council and other interested villagers.8. Lessons Learnti. A phased approach towards the design and planning of wastewater treatment systems is deemedcrucial for successful implementation. The assistance of community leaders in this process isparamount.ii. Most communities are not aware of their water sanitary situation; water testing is not carried outat all or results are not published for fear of political consequences. Water borne diseases areoften not recognised as such, but blamed on other causes for example food poisoning etc.iii. Communities often do not trust the traditional approach of governmental agencies towardswastewater treatment solutions, everybody can tell a story of treatment plants that areconstructed without or little community consultation, most of them malfunctioning and being anuisance for residents.iv. Once the communities have bought in on a specific project, they can be the driving force for aspeedy implementation of the selected solution.v. Communication on and detailed assessment of suppliers’ proposals is very critical, the majorityof proposals or presentations made are hastily done and inappropriate.vi. The financial sums involved in the implementation of centralised sewage treatment systems mayattract corrupt practices.vii. There is no general wastewater management solution; even in seemingly similar rural areas theenvironmental, socio – cultural, economical and other surrounding conditions may varysignificantly and will require different approaches. Therefore each site should be individuallyassessed. These assessments allow at the same time to gain community trust and buy in.viii. Expectations towards implementing agencies as well as cultural acceptance of specificwastewater treatment technologies may vary widely, even within a country.9. RecommendationsThe fist step should be to replicate this study and include the entire village of Charlotteville, asrequested by the Charlotteville Community Council; this approach will lower the per capita initialinvestment and offers the possibility to identify a location with lower construction costs.This study has shown that the benefits of pilot studies more than offset the initial effort and costsrelated to them, especially for high investment and long term projects such as wastewatermanagement systems for a specific area.This is mainly the case because the surrounding conditions in each location may very widely andneed detailed assessment and stakeholder buy – in.Furthermore the study has shown that a pre - selection of technology providers can tremendouslylower the risk of negligent planning and design leading to purchasing inappropriate applications.Based on our experience there might only be a few, centralised and decentralised systems that willfulfil the requirements of the LBS Protocol and overall sustainability goals, as well as countryspecific effluent water quality thresholds. Therefore appropriate technology providers can be pre -selected on a national level for a variety of possible solutions.

Keeping the financial dimensions in mind, it is strongly suggested that the pre – selection ofpotential suppliers is rigorously and independently monitored to minimise the risk of corruption.Furthermore guidelines for feasibility studies on wastewater management for rural areas on anational level and / or for the WCR should be developed, especially because sustainability trendsdirect more and more towards small scale decentralised sewerage treatment plants.It is highly recommended that such guidelines strongly emphasise a community based,participatory approach in the decision making process.10. AcknowledgementsWe would like to thank the following persons for their kind and valuable assistance with thepreparation of this assessment:The people of Charlotteville, for their inputs and participation; Mr. Kerron Eastman, President ofthe Charlotteville Community Council, for his support and practical assistance; Mrs. PatriciaTurpin, President <strong>Environment</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>, for her initiative and passion for the environment; Mr.Christopher Corbin, AMEP Programme Officer, and the United Nations <strong>Environment</strong>alProgramme, CAR/RCU, for financing the project and report review; The Pan American HealthOrganisation, for financing the previous Charlotteville Household Survey; Mr. Edmond, CEO,Water and Sewage Authority, <strong>Tobago</strong>, for his technical advise; The Ministry of the <strong>Environment</strong>and Public Utilities, for providing supporting documents.11. Bibliography1. Charlotteville Household Survey Report, <strong>Environment</strong> <strong>Tobago</strong>, Hema Singh, July 20072. Needs Assessment Guidance To Develop National Plans For Domestic <strong>Wastewater</strong> PollutionProduction, Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong> Region, United Nations <strong>Environment</strong> Programme, June 20033. The <strong>Environment</strong>al Management Act, 2000, The Water Pollution Rules, 2001, Government ofTrinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong>4. Recommendations for Decision – Making on Basic Sanitation and Municipal <strong>Wastewater</strong>Services in Latin America and the <strong>Caribbean</strong>, Version 1.1., June 2003, Sarar TransformacionS.C. , UNEP5. Pollution Control & Waste Management in Developing Countries, The CommonwealthSecretariat, 2000, SFI Publishing, ISBN; 0-85092-557-66. Managing <strong>Wastewater</strong> in Coastal Urban Areas, National Research Council, National AcademyPress, 1993, ISBN: 0-309-04826-57. Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong> Standard, Specification for the Liquid Effluent From Domestic<strong>Wastewater</strong> Treatment Plants into the <strong>Environment</strong>, TTBS 417:19938. Water and Sewage Authority: Guidelines for Design and Construction of Water and<strong>Wastewater</strong> Systems in Trinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong>, by Committee of the Board of Engineering ofTrinidad and <strong>Tobago</strong> and the Water and Sewage Authority, June 19959. Gajurel, D.R. Pre-treatment of Domestic <strong>Wastewater</strong> with Pre – Composting Tanks:Evaluation of Existing Systems, Technical University Hamburg – Harburg, Germany10. Crites, R. and Tchobanoglous, G. (1998) Small and Decentralised <strong>Wastewater</strong> ManagementSystems. McGraw – Hill Comp., Boston, USA11. Loetscher, T., Keller, J. and Greenfield, O. (1997) Appropriate Sanitation in DevelopningCountries, World Water 20 (9), 16 – 2012. Otterpohl, R., Innovative Technologien zur Abwasserbehandlung in Urbanen Gebieten,Korrespondenz Abwasser 49Jhrg./Nr.10, Okt. 2002

13. Widerer, P.A. (2000) Decentralised vs. Centralised <strong>Wastewater</strong> Management, Lecture inWanningen, Germany14. A Directory of <strong>Environment</strong>ally Sound Technologies for the Integrated Management of Solid,Liquid and Hazardous Waste for SIDS in the <strong>Caribbean</strong> Region, a UNEP/ CEHI publication,March 2004, ISBN 968-7913-31-215. N.V. Anh, et al, 2002, Decentralised <strong>Wastewater</strong> Treatment – New Concept and Technologiesfor Vietnamese Conditions.16. Code of Conduct for the Prevention of Pollution From Small Ships in Marinas and Anchoragesin the <strong>Caribbean</strong> Region, 1997, Marine <strong>Environment</strong> Division, International MaritimeOrganisation, London.17. www.cwwa.net, <strong>Caribbean</strong> Water and <strong>Wastewater</strong> Association18. www.pvs.au, PVS Müllsysteme, Austria19. www.napier-reid.com, Napier – Reid, <strong>Wastewater</strong> Treatment Systems, Toronto, Canada20. www.sbr-wastewatertreatment.eu, SBR <strong>Wastewater</strong> Treatment Systems, Netherlands21. www.watertech-ltd.com, WaterTech Limited, Trinidad, W.I.22. www.water-technology.net, A water technology network23. www.watershedmarkets.org24. www.unep.org/regionalseas/Programmes/UNEP_Administered_Programmes/<strong>Caribbean</strong>_Region/default2.asp25. www.cep.unep.org/cartagena-convention/plonearticlemultipage.2005-11-30.9771186485/plonearticle.2005-11-30.033495041326. www.cep.unep.org/cartagena-convention/plonearticlemultipage.2005-11-30.9771186485/plonearticle.2005-11-30.027055899727. www.unep.org/gc/gc23/documents/Germany.docEndnotesiThe SPAW Protocol is a protocol to the Cartagena Convention. The Convention and its Protocols constitute a legal commitmentby the participating governments to protect, develop and manage their common waters individually or jointly. Adopted inKingston, Jamaica by the member governments of the <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>Environment</strong> Programme on 18 January 1990, the SPAWProtocol preceded other international environmental agreements in utilising an ecosystem approach to conservation. The Protocolacts as a vehicle to assist with regional implementation of the broader and more demanding global Convention on BiologicalDiversity (CBD).The objective of the Protocol is to protect rare and fragile ecosystems and habitats, thereby protecting the endangered andthreatened species residing therein. The <strong>Caribbean</strong> Regional Co-ordinating Unit pursues this objective by assisting with theestablishment and proper management of protected areas, by promoting sustainable management (and use) of species to preventtheir endangerment and by providing assistance to the governments of the region in conserving their coastal ecosystems. Trinidadand <strong>Tobago</strong> signed the SPAW Protocol on the 18.01.1990 and ratified it on the 10.08.1999.ii Class 1 Waters: waters in the LBS Protocol Convention area those, due to inherent or unique environmental characteristics orfragile biological or ecological characteristics or human use, are particularly sensitive to the impacts of domestic wastewater.Class 1 Waters include, but are not limited to: coral reefs, sea - grass beds or mangroves; critical breeding, nursery or forageareas for aquatic and terrestrial life; habitats for species protected under the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas andWildlife to the Convention (SPAW Protocol); protected areas listed in the SPAW Protocol, and waters used for recreation.