76th Inaugural Lecture - 2011 by Prof. C. O. C. Onyeaso

76th Inaugural Lecture - 2011 by Prof. C. O. C. Onyeaso

76th Inaugural Lecture - 2011 by Prof. C. O. C. Onyeaso

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

IT’S A MATTER OF ARRANGEMENT:BEAUTY AND WELLNESSAN INAUGURAL LECTUREBYPROFESSOR CHUKWUDI OCHI ONYEASOBDS (Ibadan), FWACS, FWFO, MSIL, MICS<strong>Prof</strong>essor of OrthodonticsINAUGURAL LECTURE SERIESNO. 76JUNE 30, <strong>2011</strong>

DEDICATIONFirst, it is dedicated to my Lord and Saviour Jesus Christwho has made this lecture possible. Second, I dedicate itto my Late Dad and Uncle – Pa Matthias Nkemakolam<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Pa Samuel Nduche <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, as they wouldhave been glad to witness this occasion.ii

APPRECIATIONThe Apha and Omega, the Beginning and the End, theOne who decided to love me even from my mother’swomb; I bow before you and will continue to bow. Youalone have made today a reality. I remain indebted to you.May I specially thank my T., my Love, my beautiful wifeand best friend for all you have been to me over the years.Your confidence in me, love, understanding, support andprayers have made all the difference. You are my darling.To the wonderful gifts of God to us – Onyedikachi,Chinyerem, Chibuotam, Chikamaram, Favour andUgochi, I say you have indeed been blessings from God.Thank you for all the support and love. You make mehappy.Papa, Late Matthias Nkemakolam <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, I cherish yourmemories. Mama, Madam Grace <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, I thank you forall the love. I appreciate all your prayers over the years.My Uncle, Late Pa Samuel Nduche <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, I stillremember some of your kind words to me showing howmuch you cherished little me then. You were a gooduncle.iii

Dede (Mr John <strong>Onyeaso</strong>), your role in my educationalpursuit will not be forgotten. You called me a ‘good seed’and I still feel humbled <strong>by</strong> that. Thank you. Mrs CatherineMgbeokwere (Dada), I still remember how you used tohold my hands on the way to my primary school yearsago. I appreciate you. Brother, Dr Godwin <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, youcontributed significantly in my academic quest. Thankyou for being proud of me as your younger brother and allthe support and encouragement. Engr. Richard <strong>Onyeaso</strong>and Mr Merije <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (Merchandise), I appreciate yourcontributions in my life. Thank you so much. Mrs NkechiMgbeokwere, Mrs Mary Ukaigwe, Mrs Faith Nnanna andMrs Ebere Azubuike, I thank you all for your consistentlove over the years.Late Pa and Mrs S O Osho, I wish you were still alivetoday. Thank you. Rev and Mrs Abiodun Aladekomo youhave over the years shown so much love to my family.May the good Lord reward you richly. The rest of myvery dear family members from the Osho family, thankyou for all the love and support you have given us.Araka 1 of Ngodo, Chief Emeka Ogwuru, I appreciateyou. Your ‘prophecy’ about me years ago has become areality. Ogbuehi Murphy Madubuike, you have been agood elder brother and friend. Your house was alwaysavailable to me en route to Ibadan as an undergraduatestudent. Thank you.<strong>Prof</strong>essor Don Baridam (our highly respected former VC)you have left behind a wonderful impression. The loveiv

you gave made Uniport too attractive to be ignoreddespite other attractions. Thanks a lot. <strong>Prof</strong>essor NimiBriggs (a former Vice-Chancellor of Uniport) is alsoappreciated for the interest he showed when I was onadmission in hospital. <strong>Prof</strong>essor E O Ayalogu and<strong>Prof</strong>essor B J O Efiuvwevwere, you have been suchfriendly elders. Thank you. Our current articulate andfriendly Vice Chancellor, thank you for today and all youdid for me before now. May I use this opportunity tothank the entire University of Port HarcourtAdministration for her general good disposition towardsme. In fact, I appreciate all members of this Universitycommunity for their love. The Academic Staff Union ofUniversities (ASUU), Uniport Branch is speciallyappreciated.My heart is full of gratitude to my teachers whocontributed in making me what I am today. My specialappreciation goes to <strong>Prof</strong>essor M C Isiekwe for being sonice. May God bless you all richly in Jesus name. Iappreciate my Alma Mater (University of Ibadan) for theopportunities it had offered me from my undergraduatedays as a student until my position as a <strong>Lecture</strong>r.My former Provost, <strong>Prof</strong>essor B C Dibia, my Dean,<strong>Prof</strong>essor A E Obiechina, thank you for believing in me. Iappreciate you. The Senate, all my senior colleagues andcolleagues in the College of Health Sciences and otherFaculties in the University of Port Harcourt, you areappreciated.v

I want to say a big thank you to all the Hospital staff forthe exceptional love and care I received from you in 2008when I was admitted into the Hospital, especially Dr U SEtawo (former CMD), <strong>Prof</strong>essor A C Ojule (the currentCMD) and Mrs Boma Amaomu-Jumbo (DA). AssistantDirector of Nursing Services (Mrs. Weke) and theNursing staff in the intensive care unit of UPTH deservemy appreciation. May I use this opportunity to appreciate<strong>Prof</strong>essor Richard King, the Chairman of the Universityof Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH) ManagementBoard and my distinguished colleagues in the Board forthe wonderful time we have shared together.My dear colleagues and non-academic members of staffin the Faculty of Dentistry, you have been wonderful. MrsGladys Amadi deserves special mention for her variouspositive roles in the Faculty of Dentistry since itsinception. You have all meant a lot to me and we lookforward to better days ahead of us in Jesus name, Amen.To all my colleagues and friends at Ibadan and otherUniversities and hospitals in Nigeria and in diaspora, Icherish you all.My Pastors and brethren in the LORD, I thank you foryour love and prayers especially those in the UCHChristian Fellowship Ibadan, Assemblies of God ChurchFamily (Assemblies of God Church 1, Choba, PortHarcourt and Assemblies of God Church, Mokola,Ibadan), “Isuochi for Christ" family, GideonsInternational and Full Gospel Business Men’s FellowshipInternational (FGBMFI).vi

I give my special appreciation to all my friends fromIbadan, Lagos, Jos and other places outside thisUniversity who have travelled down to attend thisinaugural lecture. You shall be celebrated soon. God willgrant you journey mercies back to your differentdestinations.I love you all.vii

TABLE OF CONTENTDedication ……………………………………………… iiiAppreciation …………………………………………… iv1.0 Introduction……………………………………. 11.1 Preamble………………………………………… 11.2 Why the Title of this <strong>Lecture</strong>?.............................. 22.0 History of Orthodontics………………………. 53.0 Dental / Orthodontic Education inNigeria – The Past……………………………… 83.1 Orthodontics in Nigeria – The Present………….. 114.0 Few Definitions ………………………………… 135.0 Aetiology of Malocclusion……………………… 186.0 The Epidemiology / Pattern of Malocclusionin Nigeria………………………………………… 217.0 The Primary (Deciduous) Dentition……………. 238.0 Awareness / Perception of Malocclusionin Nigeria…………………………………………. 259.0 Quality of Life and Malocclusion amongNigerian Adolescents…………………………….. 3010.0 Quality Control in Clinical Orthodontics(Orthodontic Indices) ……………………..…… 3411.0 Potential (Epidemiology) / Real (DemandPopulation) Orthodontic Patients In Nigeria …... 4012.0 The Special Population-The ChallengedIndividuals………………………………………… 4413.0 Attitude to Orthodontic Appliances…………….. 4714.0 Preventive / Interceptive Orthodontics…………. 4914.1 The Right Time to Visit the Orthodontist………….. 5615.0 Malocclusion in Port Harcourt …………………. 5816.0 Conclusions and Recommendations……………. 59References………………………………………... 63viii

PROTOCOLThe Vice ChancellorMembers of the Governing CouncilThe Previous Vice ChancellorsDeputy Vice ChancellorsRegistrar and other Principal Officers of theUniversityProvost, College of Health SciencesDean, School of Graduate StudiesDean, Faculty of DentistryDeans of other FacultiesDistinguished <strong>Prof</strong>essorsDirectors of Institutes and UnitsHeads of DepartmentsOther distinguished Scholars and Administrative StaffMy distinguished Friends and GuestsUnique Students of Unique UniportMembers of the PressLadies and Gentlemenix

1.0 INTRODUCTION1.1 PreambleThe Vice Chancellor, Sir, it gives me great pleasure tostand before you today to deliver the 76 th inaugurallecture of this University. Today is special to me forthree reasons. First, as it goes down in history as thefirst inaugural lecture from the young Faculty ofDentistry of this University. Second, the month ofJune has become another special month in the life ofmy family, beside my birth day, when my wife andchildren remember with deep-seated gratitude to Godmy miraculous deliverance from the clutches of deathon the 3 rd of June 2008 when I survived the bulletsfrom AK 47 gun(s) at the Delta Park gate of thisUniversity. Therefore, my choice of the month ofJune for this inaugural lecture is deliberate.Unfortunately, some other precious lives were lost inthat incident. The sounds of the gun shots thatmorning could be compared to such in a warfront.May be, there would have been more shooting in thatscene that morning but suddenly I heard one of theyoung men say that the bullets had finished as I lay onthe ground in the pool of my blood. I, therefore,1

celebrate God’s deliverance and faithfulness over mylife with you today. With the permission of the ViceChancellor, may I request that the audience rise for aminute silence for those souls. May their souls rest inperfect peace. Amen. Third, today is a special day tome because I have been given the honour of givingthis once in a life time lecture as a <strong>Prof</strong>essor <strong>by</strong> theVice Chancellor to share with you briefly on myresearch activities so far as an academic.1.2 Why the Title of this <strong>Lecture</strong>?You will agree with me that every one appreciatesreceiving a complimentary remark from someone elsesuch as “You are looking nice” or “You are lookingbeautiful or handsome”. Such a remark can contributein giving a good sense of social wellbeing or wellnessto the one receiving it. The corollary is also the casein most instances. Health, as defined <strong>by</strong> the WorldHealth Organization, is a complete state of physical,mental, and social wellbeing, not merely the absenceof disease or infirmity. That means health is a qualityof life that includes your physical, mental and socialwellbeing. While physical health is the condition ofthe body, mental health is the condition of the mind2

and emotions and social health is the way you relatewith others. Wellness is another way to describequality of life. The wellness approach to good healthincludes all areas of your life and their relationship toand effect on one another. It is written: “The spirit ofthe Lord GOD is upon Me, because the LORD hasanointed Me, to -------- - - - - --, to give them beautyfor ashes, the oil of joy for mourning, - - - (Isaiah61:1-3). “An important factor in social interaction is physicalappearance. Major elements in the evaluation ofphysical appearance are the mouth and teeth (Eli etal., 2001). Dental aesthetics has great impact on thefacial attractiveness. Of a truth the teeth and the facecontribute so much to beauty, especially facial beautyand ultimately to the state of wellness of anindividual. Facial attractiveness influences matingsuccess, personality evaluations and performance andemployment prospects. In fact, attractive adults andchildren are judged more favourably and treated morepositively than unattractive adults and children interms of friendship, marriage, etc (Geld et al., 2006).Even God the creator of man in underscoring the3

importance of the tooth and its impact on man’s lifegave the law through Moses which says - - - “And ifhe knocks out the tooth of his male or female servant,he shall let him go free for the sake of his tooth(Exodus 21:27)”The Vice Chancellor, Sir, as a ConsultantOrthodontist, I have repeatedly heard the complaintsconcerning unacceptable teeth arrangement involvingmany children, adolescents and adults. This hascaused many to be worried and depressed, affectedacademic performances in schools and attractedteasing. On the other hand, I have also assessedpotential and real orthodontic patients professionallyand categorized them into different orthodontictreatment need levels besides their perceived ordesired needs. In addition, I have researched into thereactions of individuals in relation to their teetharrangements (occlusions / malocclusions) vis-a-vistheir perceptions of beauty (aesthetics) and theiroverall well-being. Therefore, these factors haveinformed the title of this lecture.4

2.0 HISTORY OF ORTHODONTICSOrthodontics is the branch of dentistry concernedwith the study of the growth of the face, thedevelopment of the occlusion, and the prevention andtreatment of dentofacial abnormalities (from theGreek Ortho-straight; odontos – tooth). That meansthe study of orthodontics includes factors such asvariations in facial development and growth andorofacial function that may influence occlusaldevelopment; it also includes the effects of occlusalvariations on facial appearance and on the health andfunction of the masticatory system.History of man’s attempts to straighten poorlyarranged or aligned teeth to improve his smile goesback thousands of years. Crude appliances thatseemingly were designed to regulate the teeth havebeen found as archaelogic artifacts in tombs ofancient Egypt, Greece, and the Mayans of Mexico(Moyers, 1988). For example, use of gold wires toalign and stabilize mandibular incisors in an adultwhose malocclusion had been complicated <strong>by</strong>periodontal disease was seen (Figure 1). Back in 400BC, Hippocrates wrote: “among those individuals5

with long shaped heads, some have thick necks,strong parts and bones. Others have strongly archedpalates, their teeth are irregularly arrayed, crowdingone another, and they are bothered <strong>by</strong> headaches andotorrhea.” Adamandios wrote that “those personswhose lips are pushed out because of cuspiddisplacement are ill-tempered, abusive shouters anddefamers.”Figure 1: Ancient Greek skull (circa 300 B.C.) shows use ofgold wires to align and stabilize mandibular incisors in anadult whose malocclusion has been complicated <strong>by</strong>periodontal disease. (Excerpt from the Handbook ofOrthodontics <strong>by</strong> R. E. Moyers)Pierre Fauchard, a famous dentist from France, madea significant contribution in the 18 th century throughan orthodontic appliance he described. In 1850 AD,6

the first texts which systematically describedorthodontics appeared and Dr. Norman Kingsley wasamong the first to use extraoral force to correctprotruding teeth. Forty (40) years later, Dr. EdwardAngle who is generally described as the “Father ofModern Orthodontics” was one of the first toemphasize occlusion in natural dentition. His interestin creating proper occlusion in natural teeth resultedin what is known as the specialty of orthodonticstoday. He started a school for training of dentists asorthodontic specialists. He also originated aclassification of malocclusion into Class I, Class II(divisions 1 and 2) and Class III, which is still in useinternationally till date. With Edward Angle’sdominate role in the development of orthodontics, in1900, along with other colleagues, the organizationknown as the American Association of Orthodontists(AAO) was established. Orthodontics became the firstspecialty in dentistry with Ophthalmology being theonly specialty in medicine in existence then.In 1940’s AD cephalometric radiographs weredeveloped to help orthodontists assess how the bonesof the face contributed to malocclusion while7

elatively recently (1970’s AD) surgical techniqueswere developed allowing oral and maxillofacialsurgeons to perform surgery on selected patientswhen growth is completed.3.0 DENTAL / ORTHODONTIC EDUCATIONIN NIGERIA – the pastNigeria is the most populous black nation in the worldwith a population of 140,431,790 million and themajority of the population being children and youngadults and relatively few over the age of 65 years(National Census, 2006).There were four (4) Dental Schools in NigerianUniversities – University of Lagos, ObafemiAwolowo University (OAU), Ile-Ife, University ofIbadan, and University of Benin.The first dental school in Nigeria (Dental School,College of Medicine, University of Lagos wasestablished in September1966. Her first set of dentalstudents 8 in number) graduated in June 1971. In1970, when the Dental School of University of Lagoswas preparing to graduate her first set of students, and8

with the help of the British Council, arrangementswere made for <strong>Prof</strong>essor Andrew Richardson ofQueen’s University, Belfast, to come and give onemonthcourse of lectures in Orthodontics (Isiekwe,1987). Andrew Richardson was subsequently invitedannually to give what was termed “Famous February”lectures in Orthodontics to the final year dentalstudents in Lagos. However, between the annual visitsof Richardson, Dr Wayne Logan, an AmericanBaptist Missionary Orthodontist to Nigeria gavecourses of lectures, concentrating on delivery oforthodontic services (Isiekwe, 1987). Richardson,understanding the need for trained Orthodontists inNigeria agreed to train an Orthodontist for thecountry.Dr Michael Isiekwe was the lucky young dentist whowas chosen to be trained and was sent to the RoyalVictoria Hospital, Belfast, UK under the tutelege of<strong>Prof</strong>essors Andrew Richardson and Philip Adams.After his training, Dr Isiekwe returned to the DentalSchool, College of Medicine of the University ofLagos, Nigeria in 1979. Dr Isiekwe (who eventuallybecame the first <strong>Prof</strong>essor of Orthodontics in Nigeria)9

took over the teaching of Orthodontics in Universityof Lagos. He played a significant role in the trainingof dental students in all the four initial Dental Schoolsin Nigeria (Lagos, Ile-Ife, Ibadan and Benin).In 1981, <strong>Prof</strong>essor Andrew Richardson was invited togive some courses of orthodontic lectures to the finalyear dental students at the University of Ibadan.Following this, Dr Michael Isiekwe initiated a twoweekconcentrated course of lectures anddemonstrations at the beginning of each final year,with further instructions in the last term before thequalifying examinations. These arrangements stillcontinued and were supplemented <strong>by</strong> two-monthlectures and clinical demonstrations in 1984 <strong>by</strong> JamesGardiner, formerly of University of Sheffield(Isiekwe, 1987).In 1983, some graduating students of OAU, Ile-Ifewere sent to Lagos for 6 months to have someexposure in all aspects of Dentistry especially inorthodontics. <strong>Prof</strong>essor Isiekwe was obviously toobusy to attend to all the Dental Schools and couldonly visit Benin Dental School once for their10

orthodontic lectures. However, Allen Bradbury of theUniversity of Leeds Dental School was able to givethe Benin students a one-month course of lectures andsome clinical demonstrations (Isiekwe, 1987).3.1 Orthodontics in Nigeria – the presentThere are now seven (7) Dental Schools in Nigeriawith the inclusion of Dental School, College ofMedicine, University of Nigeria (Enugu Campus),Dental School, College of Health Sciences,University of Port Harcourt and Dental School,University of Maiduguri. Each of the Dental Schoolshas at least one Consultant Orthodontist exceptUniversity of Maiduguri.The training of an Orthodontist takes another six (6)years in Nigeria after the first six (6) years ofundergraduate education. For any dentist to qualify asan orthodontic specialist, he/she must pass the finalprofessional examination in orthodontics in theFaculty of Dental Surgery of either the West AfricanCollege of Surgeons or the National PostgraduateMedical College of Nigeria. This process is tough andusually not all who start the race get to the finishing11

line. Some effort was made to assess the effectivenessof this programme <strong>by</strong> <strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al (2004) and theoutcome was encouraging. Although not yet perfectfor obvious environmental limitations, thisprogramme has received some favourable attention <strong>by</strong>the international professional community (Evans and<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004).With three <strong>Prof</strong>essors of Orthodontics in Nigeria –Isiekwe of University of Lagos, Otuyemi of OAU,Ile-Ife and <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (your <strong>Lecture</strong>r today) ofUniversity of Port Harcourt and other ConsultantOrthodontists, Nigeria has moved far from where westarted years ago. Indeed, the internationalorthodontic community has come to appreciateNigerian contribution to knowledge in this firstspecialty in Dentistry. As at 2004, there were twoAfricans in the Editorial Review Board of AmericanJournal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics(the leading orthodontic title in the world) – <strong>Prof</strong>essorAbbas Zaher of Egypt and <strong>Prof</strong>essor Chukwudi O<strong>Onyeaso</strong> of Nigeria. Recently, additional scholarsfrom Egypt were included in the Board.12

4.0 Few DefinitionsOcclusion of Teeth: This can briefly be defined asthe alignment and spacing of your upper and lowerteeth when you bite down or the normal relations ofthe ooclusal inclined planes of the teeth when thejaws are closed.Articulation of Teeth: Is the functional movement ofthe lower dentition in contact with the upperdentition. So while occlusion refers to a static positionwith the teeth in contact, articluation refers to adynamic continuous range of contact of the upper andlower teeth.Normal Adult Occlusion: This may be defined asthat structural composite consisting fundamentally ofthe teeth and jaws, and characterized <strong>by</strong> a normalrelationship of the so-called ooclusal, inclined planesof the teeth that are individually and collectivelylocated in architectural harmony with their basalbones and with cranial anatomy, exhibit correctproximal contacting and axial positioning and haveassociated with them normal growth, development,13

location and correlation of all environmental tissueand parts (Hitchcock, 1974).Figure 2: Clinical Pictures of Normal OcclusionIdeal Permanent Occlusion: This is an imaginaryconcept of the perfect example of occlusion of theteeth and the jaws.14

a. Lower Jawb. Upper Jaw15

c. The upper and lower jaws in occlusionFigure 3: Artificial Models showing the ideals of Occlusion inthe Permanent Dentition (Produced <strong>by</strong> db Orthodontics)Malocclusion: This can also be briefly defined as theperversion of the normal relations (Angle, 1907). It isthe degree of deviation that determines amalocclusion, and no human mouth is ever totallyfree of occlusal deviations. In view of this fact, amalocclusion of the teeth may be defined at theorthodontic clinical level as a variation in theocclusion of the teeth, sufficient to justify the hazardsof orthodontic correction (Fischer, 1957).16

The World Health Organization (WHO, 1962)included malocclusion in the group of handicappingdentofacial anomalies. These are anomalies whichcause disfigurement or impede function and for whichtreatment is required when the disfigurement orfunctional defect is likely to be an obstacle to thepatient’s physical and emotional wellbeing.Orthodontic therapy is directed to malocclusion,abnormal growth of the complex of craniofacialbones, and malfunction of the orofacialneuromusculature, which alone or in combinationmay cause any of the following: Impaired mastication. Unfortunate facial aesthetics. Dysfunction of the temporomandibulararticulation. Susceptibility to periodontal disease. Susceptibility to dental caries. Impaired speech due to malposition of theteeth.By means of suitable appliances, muscle function isimproved and teeth are positioned more favourably to17

provide better aesthetics, occlusal function, oralhealth, and speech. Correction of the craniofacialskeleton, however, is a different matter, since it ismore difficult to alter the craniofacial skeleton than itis to position teeth. It is possible, however, to directand alter favourably the growth of the craniofacialskeleton in young children. In older patients, whosefacial growth is mostly completed, the teeth arepositioned to camouflage disharmonies of the facialskeletal pattern. In most extreme cases, orthognathicsurgery is utilised in conjunction with orthodontics(Moyers, 1988).5.0 AETIOLOGY OF MALOCCLUSIONThe aetiology of malocclusion is multifactorial. Thereare several possible approaches in discussing this butfor the purpose of this lecture, Figures 4a and 4b willbe adequate.18

Figure 4a: Factors Implicated in MalocclusionSkeletal Pattern↓Space Deficiencyand → Malocclusion← LocalExcess↑Soft TissueFactorsFigure 4b: Local Factors in the Aetiology of MalocclusionMissing teeth Teeth of Supernumerary teeth↘ abnormal form ↙↓← TranspositionLabial fraenum →Habits → MALOCCLUSION ← ImpactionPathology→← Ectopic positionof Tooth germ↗ ↑ ↖Premature loss Prolonged retention Loss ofof of permanent teethdeciduous teeth deciduous teeth19

Figure 4c: Clinical Photographs showing someMalocclusionsA. B. C.D. E.F.20

A. Anterior Open biteB. Displaced eruption of the upper right centralincisorC. Crowding of the lower anterior teeth with theleft lateral incisor displaced lingually out ofthe archD. Protrusion of the upper anterior segmentE. Anterior crossbite of the upper right centralincisor which also is pushing the lower rightincisor out of the archF. Cleft Lip and Palate: The teeth are out ofalignment due to the absence of themodelling effect of the soft tissue (thiscongenital condition is due to geneenvironmentalinteractions).6.0 THE EPIDEMIOLOGY / PATTERN OFMALOCCLUSION IN NIGERIAIsiekwe (1983) showed that Angle’s class Imalocclusion was found in 76.8% schoolchildrenexamined, 14.7% had class II while class IIIaccounted for 8.4%. <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2004a) reportednormal occlusion in 24% of secondary school21

students examined, 50% had Angle class Imalocclusion, class II was found in 14% of thepopulation while class III was seen in 12%. <strong>Onyeaso</strong>(2004a) also found that 20% of the adolescents hadcrowding of their teeth with 16% having increasedoverjet which could predispose the children to dentaltrauma. Midline diastema was reported in 37% of thestudy sample.Even the clinical materials reported <strong>by</strong> <strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al.(2002a) which supported the epidemiological studiesrevealed the following: Angle’s class I – 76.5%, classII – 15.5% and class III – 8.0%. These studiesrevealed some interesting differences betweenNigerians and the Caucasians – Nigerians have betterocclusion than the Caucasians (meaning more ofnormal occlusions and less of classes II and III, aswell as less crowding of teeth). Another importantfinding from our studies is the different pattern ofmolar relationship between the Nigerians from thenorth (the Hausas) and the Yorubas in the westernpart of the country (daCosta, 1999; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004a).Nigerians in the southwest were reported to havemore class II than class III while the northern22

Nigerians had more of class III than class II molarrelationships. This suggests need for moreinvestigation and we shall do so.7.0 THE PRIMARY (DECIDUOUS) DENTITIONThe status of the primary dentition affects thedevelopment of the permanent dentition to the extentthat certain traits and anomalies of the primaryocclusion are often reflected in the permanent (Fosterand Hamilton, 1969; Infante, 1975; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> andIsiekwe, 2008a, 2008b). Therefore, the primarydentition provides the basis for studying occlusionand for predicting the occlusion of the permanentdentition (Foster and Hamilton, 1969; Tschill et al.,1997; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Isiekwe, 2008a, 2008b). As abasis for understanding the occlusion of Nigerians,<strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2006a, 2006b) analysed the occlusion of 3-5 year-olds and found some statistically significantocclusal differences among the three major ethnictribes in Nigeria. For example, generalized spacing ofthe primary dentition (a desirable occlusal feature inthis age bracket for future development of thepermanent dentition) was found more in the Iboethnic group and least in the Hausa ethnic group. This23

finding seems to support the findings in the adultdentition (daCosta, 1999; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2003a, 2004a)It was reported that ideal occlusion in the primarydentition was not real but a figment of theimagination among the Caucasians (Foster andHamilton, 1969). The features of ideal occlusioninclude the following: Generalized spacing in the anterior segment Flush terminal relationship of the seconddeciduous molars Anthropoid spaces Normal, shallow or deep overbiteInterestingly, however, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Sote (2001)discovered the presence of ideal occlusion in theprimary dentition in 2.7% of the Nigerian pre-primaryschool children examined. This important findingsuggests the basis for the better adult occlusion inNigerians than the Caucasians.24

Figure 5: Clinical Photographs showing the Ideals of Occlusionin the Primary Dentition (The anterior teeth are spaced, thereis a positive incisal overbite and overjet, the anthropoid spacesare present and the distal surfaces of the second molar teethare in the same vertical plane)8.0 AWARENESS / PERCEPTION OFMALOCCLUSION IN NIGERIAOrthodontic care is relatively new in Nigeria whencompared with the developed countries, and thecultural setting is quite different from the western25

world. The possession of obvious malocclusion is <strong>by</strong>no means the only factor which determines whetheror not an individual will seek orthodontic treatment(Prahl-Anderson et al., 1979, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> andArowojolu, 2003). <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2004b) revealed thatalthough many patients came for orthodontic carebecause they (children and their parents) felt theyneeded the treatment, some the patients came as aresult of referrals. In the western world, societalforces define the norms for acceptable, normal, andattractive physical appearance (Strauss, 1980).Identification <strong>by</strong> children and their parents ofabnormal, unacceptable, and disfiguring dentofacialcharacteristics is influenced as much <strong>by</strong> social contextand cultural milieu as <strong>by</strong> objective criteria (Mechanic,1974; Jenny, 1975; Shaw et al., 1980; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>,2003b; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Utomi, 2004; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2005a).The public equates good dental appearance withsuccess in many pursuits (Samuel, 1973; Langlois,2000).Studies have shown discrepancy between lay andprofessional judgement of dental aesthetics and needfor treatment (Prahl-Anderson et al., 1979; Shaw et26

al., 1980; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Arowojolu, 2003; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>,2003c; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Sanu, 2005a). Attractive childrenand adults are judged and treated more positively thanunattractive children and adults (Langlois, 2000).In Nigeria, although there were adolescents whoneeded treatment and agreed and wanted to have theirteeth arrangement corrected, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Arowojolu(2003) found that some adolescents who neededorthodontic treatment did not want it while some whodid not need treatment felt they needed it. <strong>Onyeaso</strong>(2003c) showed that some Nigerian parents did notexpress need for orthodontic care for their childrenwho objectively needed treatment. The parentalconcern varied significantly across socio-economicclass with parents from higher socio-economic classdesiring treatment for their children than the rest.Majority of parents (87.1%) perceived dentalaesthetics to be equally important for both girls andboys (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2003c).However, according to <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Arowojolu(2003), most of the adolescents perceived the need fororthodontic treatment than those who felt otherwise.27

Meanwhile, there was no significant associationfound between their perceived needs and theirnormative needs. It was the same finding for theirdesire for orthodontic care and their normative needs.These findings were found consistent with somerelated studies in other parts of the globe (Ingervalland Hedergard, 1974; Prahl-Anderson et al., 1979;Espeland and Stenvik, 1991).<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Sanu (2005b) looked at the relationshipamong Nigerian adolescents’ awareness ofmalocclusion, their satisfaction with personal dentalappearance, and the severity of their occlusalirregularities normatively determined. It revealedstatistically significant negative, weak correlationsbetween awareness of malocclusion and satisfactionwith dental appearance at the various levels ofmalocclusion. Age did not show any significant effecton this. Also, the association between socio-economicstatus and these variables was not significant.However, one major socio-cultural difference is thatNigerians and other Africans regard midline diastemaas a sign of natural beauty and never as a malocclusal28

trait unlike the Caucasians. Even among theCaucasians, some clinical experiences of the author inthe USA seem to indicate that some of their patientswant to retain their midline diastemata like that ofNigerians. In fact, a Dental Conference in Lagos in1999 revealed that many Nigerians especially ladieshad been to different Orthodontists and GeneralDental Practitioners requesting for creation of midlinediastema for beauty enhancement. The onlyunfortunate aspect of this development is that manyof such clients become victims of quackery with theresultant consequencies such as undue pain,dentoalveolar abscesses and sometimes unnecessaryloss of tooth or teeth.29

FIGURE 6: Clinical picture showing upper Midline Diastema9.0 QUALITY OF LIFE AND MALOCCLUSIONAMONG NIGERIAN ADOLESCENTSContemporary concepts of health suggest that dentalhealth should be defined in physical, psychological,and social well-being terms in relation to dentalstatus. Therefore, disruptions in normal physical,psychological, and social functioning are importantconsiderations in assessing oral health (WHO, 1962;Engel, 1980; Cohen and Jago, 1976). The inadequacyof the normative approach in measuring oral healthhas been recognised and led to the development ofmeasures of oral health-related quality of life(OHRQoL) (Allen, 2003). <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2009) found that42% of the secondary school children studied had30

objectively determined orthodontic treatment needwhile 62.4% suffered one oral health-related impactor the other. The relationship between the oral healthrelatedimpacts and orthodontic treatment need wasstatistically significant showing that the adolescentswho suffered some impacts were mainly those whohad teeth arrangements that needed orthodontictreatment. The study revealed that outside the highestoral health-related impact which came from physicalpain, impacts from psychological discomfort andpsychological disability due to unsatisfactory dentalappearance followed in that order. The study alsorevealed that the boys significantly had more complexmalocclusions and suffered more impacts than thegirls.Adolescence is a period of rapid physical, social, andcognitive growth as well as changes in self esteem.Self-esteem, also called self-worth, is a majorpredictor of outcomes during adolescence andadulthood. Higher levels are associated with severalpositive outcomes, such as occupational success,social relationships, well-being, positive perceptions31

y peers, academic achievement, and improvedcoping skills (Trzesniewski, 2003; Biro et al., 2006).Significant correlations were found between selfesteemand orthodontic concerns among Nigerianadolescents as well as between self-esteem and theirnormative orthodontic treatment needs (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>,2003). Research efforts concerning children haveshown that physical appearance is important inbiasing judgements of social acceptability, personalability and whether the judges are adults or children(Aloia, 1975; Clifford, 1975; Rich, 1975). Childrenthemselves see peers who are physically attractive asmore socially attractive and unattractive children aremore likely to be the victims of bullying (Cavior,1973; Kleck et al., 1974; Dion, 1977; Lowenstein,1977). <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Sanu (2005) examined thepsychosocial implications of malocclusion amongNigerian children and found that interestingly theteeth relative to other body features attracted asignificant attention from both boys and girls. In fact,teasing about perceived poor dental arrangement wasas high as that reported in the western world such asDenmark (Helm et al., 1985). The observedschoolmates’ teasing occurred significantly more32

often in the presence of malocclusion (<strong>Onyeaso</strong> andSanu, 2005).<strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al. (2005) further assessed the emotionaleffects of malocclusion in Nigerian orthodonticpatients and the findings were very informative. Dueto their malocclusions which brought them to thehospital for treatment, 44.3% of them were lessconfident, the choice of food was affected in 16.3%,15.4% found it difficult to eat in the public, 5.4%found it difficult to go out in the public, 47. 1% wasfinding it difficult to laugh in the public, 13.1% hadproblems forming close relationship, and 13.1% couldnot enjoy food. These findings attracted the attentionof professional colleagues in the internationalcommunity resulting in many desiring to duplicate thestudy.Considering the possible impacts of malocclusion onthe health status of periodontal tissues and the impactof periodontal health on the quality of life oforthodontic patients, as well as the relatedcontroversies in the literature, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al. (2003a,33

2003b) contributions have been considered as verysignificant in the orthodontic literature.10.0 QUALITY CONTROL IN CLINICALORTHODONTICS (ORTHODONTIC INDICES)The Vice Chancellor, Sir, my distinguished audience,it is my pleasure to inform you that outside mycontributions to knowledge mentioned before now,my contributions in this aspect of orthodontics havebeen acknowledged internationally with numerousrequests of my works being made till date. While stillacknowledging the contribution of Dr Edward Anglein the classification of malocclusion, it must bementioned that some limitations of his classificationhave been noted. Modern orthodontics demandsmore. Orthodontic indices are useful for purposes ofaudit, practice management and quality assurance. Itis known globally that orthodontic treatment isexpensive and in publicly funded programmes theresources are usually limited. Internationally, there isan increased demand on health care professionals todemonstrate that health services including orthodonticcare are appropriately delivered (Richmond et al.,2001a, 2001b). This applies much more to the34

developing nations like Nigeria where the economicclimate is not too favourable. Also, orthodontists musthave an acceptable means of objectively gradingseverity levels of malocclusion for decision making,proper planning and counselling of intending patientsand their parents, as well as assessment of treatmentoutcomes. Therefore, the international orthodonticcommunity had for so long looked for orthodonticindices acceptable across nations for objectiveassessment of orthodontic treatment need, as well ascomplexity of the cases. The Dental Aesthetic Index(DAI) was finally accepted <strong>by</strong> the World HealthOrganization (WHO) as a cross-cultural index forobjective (normative) assessment of orthodontictreatment need. The challenge of having an index thatcan measure treatment complexity of orthodonticcases was only recently met.The products of my research efforts have not onlygiven the baseline data for both potential and realpatients, but orthodontic patients can now beclassified according to their objective treatment needsas well as ascertaining the level of their treatmentcomplexities (anticipated difficulty) before embarking35

on such treatments. Indeed quality control in clinicalorthodontics has been enhanced (<strong>Onyeaso</strong> andAderinokun, 2003; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004b, 2004d; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>and BeGole, 2006a, 2006b, 2006c; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> andIdaboh, 2006; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and BeGole, 2007; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>,2007, 2008; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and BeGole, 2008).Beyond giving room for international comparison ofdata and standardization of different facets oforthodontic care, our work (<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and BeGole,2006c, 2007; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2007) have shownconvincingly the cost-effectiveness of using Index ofComplexity, Outcome and Need (ICON) not only inNigeria but also in the western world instead of usingdifferent indices for different facets of clinicalorthodontics.36

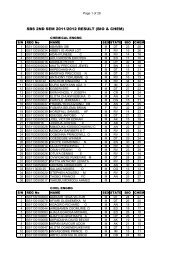

Table 1: Distribution of objective treatment need of Nigerianadolescents according to the Dental Aesthetic Index (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>and Arowojolu, 2003)Normative Severity levels Gender TotalNeed of Male FemaleDAI score Malocclusion n % n % n (%)≤ 25 Normal or minor 164 (29.9) 162 (28.6) 326 (57.5)Malocclusions withno or slight treatmentneed26-30 Definite Malocclusionwith treatment elective 59 (10.4) 49 (8.6) 108 (19.0)31-35 Severe Malocclusionwith treatment highlydesirable 30 (5.3) 25 (4.4) 55 (9.7)≥ 36Very severe or handicappingMalocclusion with treatmentconsidered mandatory 39 (6.9) 39 (6.9) 78 (13.8)37

Table 2: Complexity grades of orthodontic patients (demandpopulation) in Nigeria and North AmericaScore Range Complexity grade Nigeria* USA**% %29 Easy 1.8 529-50 Mild 23.2 1351-63 Moderate 14.3 2264-77 Difficult 21.4 2077 Very Difficult 39.3 40Nigeria*: <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Idaboh, 2006USA**: <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and BeGole, 2006c38

Table 3: Distribution of orthodontic treatment need andoutcome according to four (4) different Orthodontic indices(<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and BeGole, 2007)Index Treatment Need Treatment OutcomePresent Absent Acceptable UnacceptableICON 86 14 94 6DAI 85 15 - -PAR - - 97 3ABO-OGS - - 86 14ICON: Index of Complexity, Outcome and NeedDAI: Dental Aesthetic IndexPAR: Peer Assessment Rating IndexABO-OGS: American Board of Orthodontics ObjectiveGrading System39

11.0 POTENTIAL (EPIDEMIOLOGY) / REAL(DEMAND POPULATION) ORTHODONTICPATIENTS IN NIGERIAIt is interesting to note that while no significantdifferences have been found in the orthodontictreatment need and complexity with respect to genderin epidemiological studies, demand populations haveshown that significantly more females seekorthodontic care than males (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004a;<strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al., 2005). In addition, very severe andhandicapping malocclusions were seen significantlymore in male than female patients (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004b).In fact, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2009) found higher oral healthrelatedimpacts in the males than females in anepidemiological study. Meanwhile, most of thepatients who came for orthodontic treatment <strong>by</strong>themselves without referral were females (2004c).This trend could be attributed to a reflection of the socalled‘sex role stereotyping,’ wherein the societyplaces greater emphasis on the possession of highphysical attractiveness in the female (Shaw et al.,1991).40

<strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2004b) showed that almost 3% of thechildren and young adults (6-18- year-olds) had no /little need for orthodontic treatment, 20% hadtreatment need for which treatment was considered‘elective,’ 15% had a ‘desirable’ need for treatmentand 35% had mandatory need for treatment. Inanother report (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004d) on adult orthodonticpatients aged 20-55 years, 32.6% had very severe orhandicapping malocclusions with treatmentconsidered mandatory with the same percentage ofthe patients having little or no need for treatment.Those with severe malocclusion where treatment wasconsidered as desirable accounted for 20.4%. Electivetreatment need was found in 14.3%.No significant association has been found betweensocio-economic class and prevalence of malocclusionin epidemiological studies (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2003a;<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004a), but <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2004b) in the demandpopulation found a statistically significant associationbetween the orthodontic treatment needs and thesocio-economic class of the patients with morehandicapping treatment needs found among thechildren and adolescents from the lower socio-41

economic class (semi-skilled and unskilledoccupations) than those in the higher socio-economicclass. Also, well over two-third of the adultorthodontic patients reported to have soughtorthodontic care were from the higher socioeconomicclass. It was concluded thatsignificantly more adults from higher socio-economicclass came for treatment partly as a reflection of theirbetter economic power because orthodontic treatmentis usually expensive and partly due to their betterawareness and attitude to aesthetics than those adultsfrom the lower socio-economic group.It was concluded that not all who came or werereferred for orthodontic treatment needed suchtreatment based on professional assessment but theirperceptions of the dental appearance needed to beconsidered in order to satisfy the patients / parents.Meanwhile, most of the patients from the lower socioeconomicclass presented for treatment because ofhandicapping malocclusions with severely affectedaesthetics (beauty).42

<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Idaboh (2006) found that 60.7% of theclinical cases had malocclusions that belonged to thedifficulty / very difficult complexity groups while<strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2008) in an epidemiological study revealedthat 2.6% belonged to the difficulty and verydifficulty complexity groups.43

Figure 7: Clinical photographs showing pre-treatment, duringtreatment and post-treatment stages of a 30-year-oldNigerian12.0 THE SPECIAL POPULATION (THECHALLENGED INDIVIDUALS)The United Nations General Assembly in itsdeclaration of the rights of the child affirmed the rightof children who are physically, mentally or socially44

handicapped to special treatment, education and carerequired <strong>by</strong> their particular condition. Children withdisabilities need functional and aestheticconsideration comparable to that of ‘normal’childrenor persons. This is even more so due to the increasingtrend toward normalization of such children in homeenvironments (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2002a). Malocclusions withsevere aesthetic implications can compromise alreadydifficult social relationships and potentialemployment opportunities.The Vice Chancellor, Sir, and my esteemed audience,<strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2003d) produced the first work on theobjective treatment need of mentally handicappedchildren in orthodontics which has since then been themajor literature on the subject globally. This was firstacknowledged <strong>by</strong> the then Editor-in-Chief of theJournal of Dentistry for Children in Chicago, USA,while congratulating him on the work. The studyrevealed that 32% of the studied population hadsevere or handicapping malocclusions qualifying forpublicly funded orthodontic care. A related study(<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Arowojolu, 2003) gave 13.8% withsuch needs in the ‘normal’ children. <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2004e)45

further analysed this facet of orthodontic treatmentamong different groups of challenged children inNigeria and found that their needs doubled that of the‘normal’children. Earlier, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2002a) showedthat such children could be susceptible to fracture oftheir anterior teeth there<strong>by</strong> worsening the alreadyunfavourable dental aesthetics resulting from poorarrangement or positioning of the teeth. Now, thequestion is this: Can these percentages of our childrenwith such handicapping malocclusions with theassociated psychosocial implications be able to accessorthodontic care in Nigeria today withoutGovernment or publicly-funded programme? Yourguess is as good as mine.<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and daCosta (2009) further investigated intothe orthodontic treatment need and complexity ofsickle cell anaemia subjects and found that 50% ofthem had poor dental aesthetics and this correlatedstrongly with their severe and handicappingorthodontic treatment needs and the difficult and verydifficult complexity grades. This was concluded to bea reflection of the degree of craniofacial abnormalityfound in these special subjects. Realizing that this46

disease is peculiar to the black race and the high levelof inconveniences they go through along with theirparents in their overall medical care; it would seemreasonable to have such patients under publiclyfundedprogramme(s). Meanwhile, the campaign forthe prevention of this deadly disease (sickle cellanaemia) must continue while the victims should behelped to receive free or highly subsidized treatment.13.0 ATTITUDE TO ORTHODONTICAPPLIANCESAlthough orthodontic treatment has its associatedinconveniences such as regular visits to theorthodontists (usually at 4-6 week intervals), somediscomfort, restrictions on food habits, and others,orthodontic appliances (braces) are still regarded as a‘symbol or badge of social class’ globally. Childrenundergoing orthodontic treatment usually show offtheir braces as they derive some sense of fulfilment orsatisfaction from the wear of orthodontic braces. Thereason is obvious because it is often the children fromthe relatively comfortable homes that can afford thecost of an orthodontic appliance. This trend is alreadyemerging in Nigeria.47

<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Utomi (2007a) found that 69% of thepatients were happy to look at the mirror with theirappliances on and admiring them while 63.1% wereglad to let their friends see their appliances.Concerning some worries over their appliances, the‘cumulative orthodontic appliance worry score’revealed that 80.3% belonged to moderate worrygroup while 17.9% and 1.8% belonged to low andhigh worry groups, respectively. The worries had todo with some of the restrictions on food and someunavoidable discomforts associated with teethmovement.Realizing the importance of communication inachieving the desired orthodontic treatment outcomeand in an attempt to contribute to quality assurance inorthodontics, especially in Nigeria, we investigatedinto informed consent among orthodontic patients(<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Utomi, 2007b) The findings showedthat 76.7% claimed they asked their Orthodontistsquestions during the decision-making process and87.3% described the communication between themand their Orthodontists as very satisfactory.14.0 PREVENTIVE / INTERCEPTIVE48

ORTHODONTICSThe Vice Chancellor, Sir, and my distinguishedaudience, I have intentionally left this part of mylecture last so as to draw your special attention to it.Preventive orthodontics, as the name implies, isaction taken to preserve the integrity of what appearsto be the normal occlusion at a specific time (Graber,1966). Interceptive orthodontics, which is similar inpurpose and virtually synonymous with the termpreventive orthodontics, may be defined as that phaseof the science and art of orthodontics employed torecognize and eliminate potential irregularities andmalpositions in the developing dentofacial complexor the art and science of fostering developmentalchanges which are favourable, and halting orminimizing those which are not (Richardson, 1995).Richardson (1995) further said that there is no doubtthat for individual children, skilful, timely andknowledgeable interceptive treatment alone canproduce a satisfactory result and for others earlyinterception will simplify appliance therapy at a laterstage. This philosophy of orthodontic care requiresthe services of well-trained general dental49

practitioners, especially in a developing economy likeNigeria (<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and daCosta, 2000).Internationally, despite earlier debates on the idealtiming for early orthodontic treatment, there is now agrowing interest in this treatment philosophy. TheAmerican Board of Orthodontists (Bishara et al.,1998) came out so strongly in support of thistreatment philosophy, which also has the blessings ofEurope and others.Although the work of interceptive orthodonticsdemands being ever vigilant, there are particulartimes when developing malocclusions can mostreadily be identified in growing children: first, shortlyafter completion of the primary dentition (ba<strong>by</strong> teeth)at about 3 years, the second is about 7-9 years whenthe first permanent molars will normally have eruptedand the permanent incisors should be erupting and thethird is about 11-12 years when the premolars, secondmolars and canines should be coming into the oralcavity. According to Richardson (1995), the fact thatthese ages of special vigilance do exist has led to theproposal that the child population should be screened50

at these ages and interceptive measures applied whereappropriate.While the main challenge to the introduction of thismeasure on a large community basis in Nigeria isfinance, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Sote (2002) reported that 40.5%pre-primary Nigerian school children (aged 3-5 years)had one form of malocclusion or the other and somebenefitted from the survey. Earlier, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> andSote (2001) showed that 13.1% (6.7% males and6.4% females) in a sample of 3-5-year-olds wereinvolved in oral habits with resultant malocclusaltraits already present. Digit sucking was the mostprevalent oral habit reported in the study. <strong>Onyeaso</strong> etal. (2002) and <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2003a) also reported on someof the observed needs for preventive / interceptiveorthodontics in epidemiological studies.In addition, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al. (2003) and <strong>Onyeaso</strong>(2005b) reported significant proportions of patientswho sought orthodontic care at the UCH, Ibadan thatbenefitted from interceptive orthodontics. About 77%of the patients needed extractions of retained primaryteeth obviously causing poor alignment or51

arrangement of the permanent set, 9.1% hadproclination of the maxillary anterior teeth withmoderate crowding. Over 7.4% were involved in oralhabits, 5.8% had anterior crossbite and 0.8% hadsupernumerary teeth.<strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2004f, 2004g) reported some serious effectsof oral habits among Nigerian children aged 7-10years, among other interceptive needs in the agegroup. Some of the children could not concentrate ontheir school works because of the intensity andfrequency of some of the habits. <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and<strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2006) reported high interceptive needs(51.8%) among 11-12-year-old Nigerian childrenwith increased proclination of the upper anterior teeththat could predispose them to accidental trauma,among other malocclusal traits including othermarked deleterious effects of oral habits.It should be mentioned here that research efforts inNigeria (<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Sote, 2001; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al.,2002; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004c, 2004f, 2004g; <strong>Onyeaso</strong> and<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2006) have shown that a reasonablepercentage of our pre-primary, primary and even52

some secondary school children are involved in somedeleterious oral habits such as thumb or fingersucking, tongue thrusting, etc, which if seen on timein the clinic could be helped before their bad occlusalconsequences. Moreover, <strong>Onyeaso</strong> (2004a) reportedthat 76% of studied adolescents had somemalocclusions suggesting an increase in theprevalence of malocclusions with increasing age.Our preventive work and campaign againstmalocclusion was also extended to the field of sports(<strong>Onyeaso</strong> and Adegbesan, 2003a, 2003b; <strong>Onyeaso</strong>,2003e, 2004h, 2004i; Adegbesan and <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2004;<strong>Onyeaso</strong> et al., 2004), which actually createdincreased awareness and was considered as a majorcontribution with the subsequent commendations andrecognition <strong>by</strong> the international community(www.SportsDDS.com/Nigeria). The ViceChancellor, Sir, besides the numerous reprint requestsfrom researchers across the globe and before theinclusion of my profile in the website, I wasparticularly thrilled when I received a letter from theInformation Centre of the British Dental Association,53

UK asking for a copy of one of the papers for theirarchives.Figure 8: Clinical pictures below are examples of the casesthat could be prevented and would benefit from interception:A. B.C. D.54

E. F.G.A and B: Showing retention of deciduous teeth while the permanentsuccessors are erupting inside in the wrong places that result in poorteeth arrangement. C and D: Showing the same problem occurringin the upper teeth. This problem is common in our environment butcan be prevented <strong>by</strong> early visit to the Orthodontist. E: This is calledanterior crossbite involving one upper tooth and one lower tooth.Note that the lower tooth involved is being pushed out its support inthe ridge. This could cause future problems with the joints(Temporomandibular Joints) joining the upper and lower jawstogether. Such associated problems would be prevented <strong>by</strong> earlyvisit to the Orthodontist. F: Protruding upper anterior teeth. Note55

that child can not close the mouth at rest and such a child is usuallyprone to trauma to the teeth, especially while playing with otherchildren. Again, this can be prevented <strong>by</strong> orthodontic interception.G: An 8-year-old girl who was sucking her left forearm and theresultant severe (10mm) open bite.14.1 The Right Time to Visit the OrthodontistAccording to the American Board of Orthodontists(ABO), the right time for an orthodontic check upshould not be later than age 7. The reasons are asfollows: Orthodontists can spot subtle problems withjaw growth and emerging teeth while someprimary (ba<strong>by</strong>) teeth are still present. While your child’s teeth may appear to bestraight, there could be a problem that only anOrthodontist can detect. The check up may reveal that your child’s biteis fine. Often, the Orthodontist will identify apotential problem but recommend monitoringthe child’s growth and development, and then,if indicated, begin treatment at the right timefor the child. In other cases, the Orthodontistmight find a problem that can benefit fromearly treatment.56

Early treatment may prevent more seriousproblems from developing and may maketreatment at a later age shorter and lesscomplicated. In some cases, the Orthodontist will be able toachieve what would not be possible once theface and jaws have finished growing. Early treatment may give your Orthodontist thechance to:1. guide jaw growth2. lower the risk of trauma to protruded front teeth3. correct oral harmful habits4. improve appearance5. guide permanent teeth into a more favourableposition6. improve the way the lips meet Through early orthodontic screening, you willbe giving your child the best opportunity for ahealthy, beautiful smile that is good for life.Other advantages of interceptive orthodonticsinclude: being relative less expensive no decalcification no root resorption57

no soft tissue problems reduced chances of relapse no iatrogenic cariesHowever, you can still visit your Orthodontist at anyage instead of not showing up at all. It is true thatorthodontic treatment is expensive but it is notexpensive in comparison with the cost of dealing withuntreated problems. Orthodontic treatment may bringlong-term health benefits and may contribute to theavoidance of costly, serious problems later in life.15.0 MALOCCLUSION IN PORT HARCOURTSome of our clinical materials about to be publishedshow that the pattern of malocclusion here in PortHarcourt is not different from those reported from thesouth west and south east parts of Nigeria (<strong>Onyeaso</strong> etal., Eigbobo et al., in press). A recent work <strong>by</strong> mypostgraduate student (Aikins, 2010) has revealed thatthe objective treatment need and complexity of thepotential orthodontic cases from Port Harcourt areconsistent with earlier reports (<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, 2008, 2009).Although my experience so far in Port Harcourtshows that many children including adults needorthodontic treatment, the dental awareness here58

when compared to the south west Nigeria isunderstandably poor and needs to improve. Ourrecent work (Eigbobo et al., in press) shows that only4.1% of the children who have received treatment inour clinic at the University of Port Harcourt teachingHospital came for routine check while the restshowed up due to one problem or the other. We shallwork more to change this situation and also providethe necessary data through more research activitiesboth for academic purposes, as well as for anorganized and systematic planning of orthodontic carein this environment. With availability of fund, wehope to look into some other aspects of modernorthodontics that have not been studied in Nigeria.16.0 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS The art and science of orthodontics will assistyou in improving your smile at any age butearly presentation toy our orthodontist willfacilitate early diagnosis and best possibleoutcome for enhanced beauty and wellness. The prevalence of malocclusion and desire fororthodontic treatment are expected to be on theincrease with civilization or modernization and59

this is the expectation in the Nigeria oftomorrow. Although many Nigerian adultshave been able to cope with theirmalocclusions without receiving orthodontictreatment, more of our younger population andthe future generations will certainly demandorthodontic care. Our Governments (Local, State and Federal),Oil companies in the Niger Delta Region,banks, other organizations and wealthyNigerians should as a matter of urgency assistin the crusade for increased awareness andprevention / interception of malocclusion inNigerian children due to the obviousadvantages such as cost-effectiveness andbetter treatment outcome. Generally, Nigerian Government should reallygive more attention to medical /dental researchas no amount of money can be too much for thehealth of our people. This will eventuallyimpact on the quality of healthcare services inour country. Nigerians can get in Nigeria whatthey are looking for abroad once the localatmosphere is encouraging.60

The introduction of some publicly fundedfacilities for the management of the very severe/ handicapping malocclusions so as to enablethose involved (whether special or the‘normal’populations) access treatment morereadily in order to reduce the negativepsychosocial effects and improve wellness orthe quality of life of our people deserves thesupport of all. One way individuals, organizations orgovernments can be more involved is <strong>by</strong> settingup an “Orthodontic Research Foundation” inthe Faculty of Dentistry, College of HealthSciences, University of Port Harcourt.University of Port Harcourt will be glad toname the Foundation after the name of thedonor whether an individual, organization orgovernment. You can also donate towards theprogramme “Subsidy for Orthodontic Care”which will be strictly for those who qualify forit based on professional assessment of theirorthodontic treatment needs. The latter will bebased in the University of Port HarcourtTeaching Hospital (UPTH).61

The Vice Chancellor, Sir, my distinguishedaudience, permit me to end this lecture herebelieving that <strong>by</strong> the grace of God we shall seeagain in some years to come when I hope togive my valedictory lecture. Let us prayerfullyimbibe the attitude of hard work as we attemptto arrange things better generally in thiscountry because therein also lies the beautyand wellness of our nation.Thank you for your kind attention.62

REFERENCESAdegbesan, O.A., <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004): Perception ofNigerian athletes on the use of mouth guard as an antidoteto stresses of sports injury. British Journal of SportsMedicine 38: 685-689.Aikins, E.A. (2010): Perception of Dental Aesthetics andOrthodontic Treatment Need and Complexity ofAdolescents in Rivers State, Nigeria. A DissertationSubmitted to the Faculty of Dental Surgery, NationalPostgraduate Medical College of Nigeria.Allen, P.F. (2003): Review: Assessment of oral healthrelated quality of life. Health and Quality of LifeOutcome 1: 40.Angle, E. (1907): Malocclusion of the Teeth. 7 thPhiladelphia, S.S. White, p.7.ed.Biro, F.M., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Franko, D. L., Padgett,J., Bean, J. A. (2006): Self-esteem in adolescent females.Journal of Adolescent Health 39: 501-507.Bishara, S.E., Justus, R., Graber, T.M. (1998):Proceedings of the workshop discussions on earlytreatment. American Journal of Orthodontics andDentofacial Orthopedics 113(1): 5-6.63

Clifford, M., Walster, E. (1975): The Effects of Physicalattractiveness on Teachers Expectations. Sociology ofEducation 46: 248-258.Cohen, K., Jago, J.D. (1976): Toward the formulation ofsocio-dental indicators. International Journal of HealthServices 6: 681-687.daCosta, O.O. (1999): Prevalence of malocclusion amongpopulation of northern Nigerian school children. WestAfrican Journal of Medicine 18(2): 91-96.Dion, K.K. (1977): The incentive value of physicalattractiveness for young children. Personality and SocialPsychology Bulletin 3: 67-70.Eigbobo, J.O., <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Okolo, N. (2010): Patternof presentation of oral health conditions among childrenat the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital.Brazilian Research in Pediatric Dentistry and IntegratedClinic (In Press).Eigbobo, J.O., Gbujie, D.C., <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (<strong>2011</strong>):Causes and pattern of tooth extractions in children treatedat the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital.Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale (In Press).64

Eli, L., Bar-Tat, Y., Kostovetzki, I. (2001): At FirstGlance: Social Meaning of Dental appearance. Journal ofPublic Health Dentistry 6(3): 150-154.Engel, G.L. (1980): The clinical application ofbiopsychosocial model. American Journal Psychiatry 137:535-544.Espeland, L.V., Stenvik, A. (1991): Orthodonticallytreated young adults: awareness of their own dentalarrangement. European Journal of Orthodontics 13: 7-14.Evans, C.A., <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004): OrthodonticOpportunities in Nigeria. World Journal of Orthodontics5(4): 368-369.Fischer, B. (1957): Clinical Orthodontics. Philadelphia,W.B. Saunders, p.51-61.Foster, T.D., Hamilton, M.C. (1969): Occlusion in theprimary dentition. British Dental Journal 126: 76-79.Geld, V. P., Ooster, P., Heck, V.G., Kuijpers - Jagtman,A.M. (2006): Smile attractiveness. Self-perception andinfluence on personality. Angle Orthodontist 77(5): 759-765.65

Graber, T. (1966): Orthodontics, Principles and Practice,2 nd ed. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders, p.11.Hitchcock, H. P. (1974): Orthodontics forUndergraduates, Philadelphia, Lea and Febiger, p.5-6.Infante, P.F. (1975): Malocclusion in the deciduousdentition in white, black and Apache Indian children.Angle Orthodontist 45: 213-218.Ingervall, B., Hedegard, B. (1974): Awareness ofmalocclusion and desire for orthodontic treatment in 18-year-old Swedish men. Acta Odontologia Scandinavia 32:93-101.Isiekwe, M.C. (1987): The teaching of undergraduateorthodontics in Nigeria. British Journal of Orthodontics14: 269-271.Jenny, J. (1975): Social perspective on need and demandfor orthodontic treatment. International Dental Journal 25:248-56.Langlois, J.H. (2000): Maxims or myths of beauty?Ameta-analysis and theoretical review. PsychologicalBulletin 126: 390-423.66

Mechanic, D. (1974): Ideology and medical technologyand health care organizations in modern nations.American Journal of Public Health 65: 241-7.Moyers, R.E. (1988): Development of the Dentition andOcclusion. In: Handbook of Orthodontics, 4 th ed. St.Louis Mos<strong>by</strong> Year book Ltd. Pg 99-146.National Population Commission of Nigeria: NationalCensus, 2006.New King James Version of the Holy Bible.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2000): Orthodontic services provided <strong>by</strong>General Dental Practitioners (GDPs) in two major citiesin Nigeria. Nigerian Quarterly Journal of HospitalMedicine 10(4): 255-259.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2001): Prevalence of oral habits in 563Nigerian pre-school children aged 3-5 years. NigerianPostgraduate Medical Journal, 8(4): 193-195. Erratum in:Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal, (2002); 9(3): 178-179.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Sote, E.O. (2001): Prevalence of ‘IdealOcclusion’ in Nigerian pre-school children. Journal ofMedicine and Medical Sciences 3(1): 28-31.67

<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Sote, E.O. (2002): A study ofmalocclusion in the primary dentition in a population ofNigerian children. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice5(1): 52-56.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Aderinokun, G.A., Arowojolu, M.O.(2002): The pattern of malocclusion among orthodonticpatients seen in Dental Centre, University CollegeHospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Medicineand Medical Sciences 31: 207-211.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2002a): Occlusal anomalies inhandicapped school children in Ibadan, Nigeria: anepidemiological survey. Nigerian Dental Journal 17(1):14-18.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2002b): Malocclusion pattern among thehandicapped school children in Ibadan, Nigeria. NigerianJournal of Clinical Practice 5(1): 57-60.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Sote, E.O., Arowojolu, M.O. (2002):Need for preventive and interceptive orthodontictreatment in 3-5 year-old Nigerian children in two majorcities. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences31: 115-118.68

<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Denloye, O.O., Taiwo, J.O. (2003):Preventive and interceptive orthodontic demand formalocclusion. African Journal of Medicine and MedicalSciences 32(1): 1-5.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2003a): An epidemiological survey ofocclusal anomalies among secondary school children inIbadan, Nigeria.Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 26(102):25-29.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2003b): An assessment of relationshipbetween self-esteem, orthodontic concern, and DAI scoresamong secondary school students in Ibadan, Nigeria.International Dental Journal 53(2): 79-84.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2003c): Orthodontic concern of parentscompared with orthodontic treatment need assessed <strong>by</strong> theDental aesthetic Index (DAI) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 26(101): 13-20.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2003d): Orthodontic treatment need ofmentally handicapped children in Ibadan, Nigeria,according to the Dental Aesthetic Index. Journal ofDentistry for Children 70(2): 159-163.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2003e): Oro-facial injuries andmouthguard use in sports: Knowledge and Attitudes of69

Coaches in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Health andBiomedical Sciencess 2(2): 68-72.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Adegbesan, O.A. (2003): Oro-facialinjury and mouthguard usage <strong>by</strong> athletes in Nigeria.International Dental Journal 53:231-236.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Adegbesan, O.A. (2003): Knowledge andattitudes of coaches of secondary school athletes inIbadan, Nigeria regarding oro-facial injuries andmouthguard use <strong>by</strong> the athletes. Dental Traumatology19(4): 5-9.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Arowojolu, M.O. (2003): Perceived,desired and normatively determined orthodontic treatmentneeds among orthodontically untreated Nigerianadolescents. West African Journal of Medicine 22(1): 5-9.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Arowojolu, M.O., Taiwo, J.O. (2003a):Periodontal status of orthodontic patients and therelationship between Dental Aesthetic Index andCommunity Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs(CPITN). American Journal of Orthodontics andDentofacial Orthopedics 124(6): 714-720.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Arowojolu, M.O., Taiwo, J.O. (2003b):Oral Hygiene status and occlusal characteristics oforthodontic patients at University College Hospital,70

Ibadan, Nigeria. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 26(103):24-28.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Aderinokun, G.A. (2003): Therelationship between the Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI)and perceptions for aesthetics, function and speechamongst secondary school children in Ibadan, Nigeria.International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 13(5): 336-341.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004a): Prevalence of malocclusionamong adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. American Journalof Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 126(5): 604-607.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004b): Orthodontic treatment need ofNigerian outpatients assessed with the Dental aestheticIndex. Australian Orthodontic Journal 20(1): 19-23.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004c): Demand and referral pattern fororthodontic care at the University College Hospital(UCH), Ibadan, Nigeria. International Dental Journal 54:250-254.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004d): Orthodontic treatment need anddemand in a group of Nigerian adults: a teaching hospital-71

ased study. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 27(107): 32-36.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004e): Comparison of malocclusionsand orthodontic treatment needs of hanicapped andnormal children in Ibadan using the Dental AestheticIndex (DAI). Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal11(1): 40-44.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004f): Need for preventive /interceptive orthodontic treatment among 7-10 year-oldchildren in Ibadan, Nigeria: an epidemiological survey.Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 27(107): 15-19.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004g): Oral habits among 7-10 year-oldschool children in Ibadan, Nigeria: an epidemiologicalsurvey. East African Medical Journal 81(1): 16-23.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004h): Oro-facial trauma in amateursecondary school footballers in Ibadan, Nigeria: a study ofmouthguards. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 27(105):32-36.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004i): Secondary school athletes: astudy of mouthguards. Journal of National MedicalAssociation 96(2): 240-245.72

<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. Arowojolu, M.O., Okoje, V.N. (2004):Nigerian dentists’ knowledge and attitudes towardsmouthguard protection. Dental Traumatology 20(4): 187-191.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Utomi, I.L. (2004): Expectations oftreatment and satisfaction with facial appearance inNigerian orthodontic patients. Odonto-StomatologieTropicale 27(108): 37-41.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2004j): Permanent double teeth andhypodontia in a pair of monozygotic twins: case report.Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 27(108): 33-36.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Utomi, I.L., Ibekwe, T.S. (2005):Emotional effects of malocclusion in Nigerian orthodonticpatients. The Journal Contemporary Dental Practice 6(1):64-73.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Sanu, O.O. (2005a): Perception ofpersonal dental appearance in Nigerian adolescents.American Journal of Orthodontics and DentofacialOrthopedics 127(6): 700-706.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Sanu, O.O. (2005): Psychosocialimplications of malocclusion among 12-18-year-old73

secondary school children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 28(109): 39-48.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2005a): Expectations of orthodontictreatment and satisfaction with dental appearance amongNigeria parents. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 28(110):36-40.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2005b): Incidence of retained deciduousteeth in a Nigerian population: an indication of poordental awareness / attitude. Odonto-StomatologieTropicale 28(111): 5-9.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., BeGole, E.A. (2006a): Orthodontictreatment need in an accredited graduate orthodonticcenter in North America: a pilot study. The Journal ofContemporary Dental Practice 7(2): 87-94.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., BeGole, E.A. (2006b): Orthodontictreatment – improvement and standards using the PeerAssessment Rating (PAR) Index. The Angle Orthodontist76(2): 260-264.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., BeGole, E.A. (2006c): Orthodontictreatment standard in an accredited graduate orthodonticclinic in North America assessed using the Index of74

Complexity, Outcome and Need (ICON). HellenicOrthodontic Review 9: 23-34.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2006a): Occlusion in the primarydentition. Part 1: A preliminary report on comparison ofantero-posterior relationships and spacing among childrenof the major Nigerian ethnic groups. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 29(114): 9-14.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2006b): Occlusion in the primarydentition. Part 2: A comparison of some occlusal traitsamong pre-school children of the 3 major ethnic groups inNigeria. Odonto-Stomatologie Tropicale 29(115): 23-29.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., <strong>Onyeaso</strong>, A.O. (2006): Occlusal / Dentalanomalies found in a random sample of Nigerian schoolchildren. Oral Health and Preventive Dentistry 4(3): 181-186.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Idaboh, G. (2006): Orthodontic treatmentcomplexity and need at the University College Hospital,Ibadan, Nigeria, according to the Index of Complexity,Outcome and Need (ICON): A pilot study. PediatricDental Journal 16(2): 128-131.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., BeGole, E.A. (2007): Relationshipbetween Index of Complexity, Outcome and Need, Dental75

Aesthetic Index, Peer Assessment Rating Index andAmerican Board of Orthodontics objective gradingsystem. American Journal of Orthodontics andDentofacial Orthopedics 13(2): 248-252.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2007): Orthodontic treatmentcomplexity and need in a group of Nigerian patients: Therelationship between the Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI)and the Index of Complexity, Outcome and Need (ICON).The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice 8(3): 37-44.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Utomi, I.L. (2007a): Attitudes ofNigerian patients to the use of orthodontic appliances.Hellenic Orthodontic Review 9: 73-86.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Utomi, I.L. (2007b): Informed Consent inOrthodontics: Experiences of Nigerian patients. HellenicOrthodontic Review 10: 29-39.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O., Isiekwe, M.C. (2008a): Occlusal changesfrom primary to mixed dentitons in Nigerian children. TheAngle Orthodontist 78(1): 64-69.<strong>Onyeaso</strong>, C.O. (2008): Relationship between Index ofComplexity, Outcome and Need and Dental AestheticIndex in the assessment of orthodontic treatmentcomplexity and need of Nigerian adolescents. Brazilian76