Lesson Template 12-13

Lesson Template 12-13

Lesson Template 12-13

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

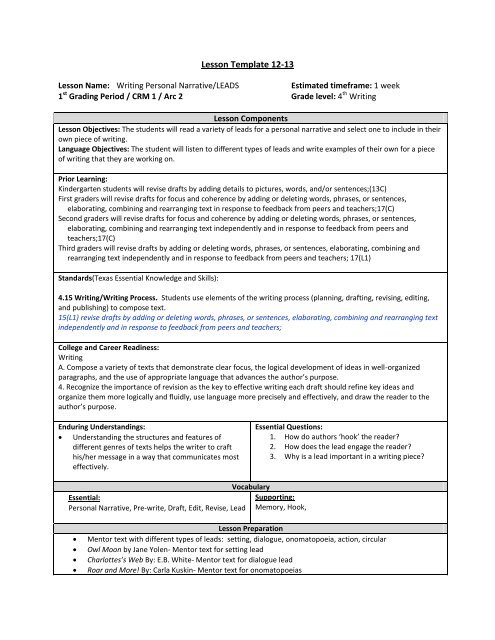

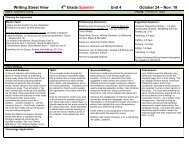

<strong>Lesson</strong> <strong>Template</strong> <strong>12</strong>-<strong>13</strong><strong>Lesson</strong> Name: Writing Personal Narrative/LEADSEstimated timeframe: 1 week1 st Grading Period / CRM 1 / Arc 2 Grade level: 4 th Writing<strong>Lesson</strong> Components<strong>Lesson</strong> Objectives: The students will read a variety of leads for a personal narrative and select one to include in theirown piece of writing.Language Objectives: The student will listen to different types of leads and write examples of their own for a pieceof writing that they are working on.Prior Learning:Kindergarten students will revise drafts by adding details to pictures, words, and/or sentences;(<strong>13</strong>C)First graders will revise drafts for focus and coherence by adding or deleting words, phrases, or sentences,elaborating, combining and rearranging text in response to feedback from peers and teachers;17(C)Second graders will revise drafts for focus and coherence by adding or deleting words, phrases, or sentences,elaborating, combining and rearranging text independently and in response to feedback from peers andteachers;17(C)Third graders will revise drafts by adding or deleting words, phrases, or sentences, elaborating, combining andrearranging text independently and in response to feedback from peers and teachers; 17(L1)Standards(Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills):4.15 Writing/Writing Process. Students use elements of the writing process (planning, drafting, revising, editing,and publishing) to compose text.15(L1) revise drafts by adding or deleting words, phrases, or sentences, elaborating, combining and rearranging textindependently and in response to feedback from peers and teachers;College and Career Readiness:WritingA. Compose a variety of texts that demonstrate clear focus, the logical development of ideas in well-organizedparagraphs, and the use of appropriate language that advances the author’s purpose.4. Recognize the importance of revision as the key to effective writing each draft should refine key ideas andorganize them more logically and fluidly, use language more precisely and effectively, and draw the reader to theauthor’s purpose.Enduring Understandings: Understanding the structures and features ofdifferent genres of texts helps the writer to crafthis/her message in a way that communicates mosteffectively.Essential Questions:1. How do authors ‘hook’ the reader?2. How does the lead engage the reader?3. Why is a lead important in a writing piece?VocabularyEssential:Supporting:Personal Narrative, Pre-write, Draft, Edit, Revise, Lead Memory, Hook,<strong>Lesson</strong> PreparationMentor text with different types of leads: setting, dialogue, onomatopoeia, action, circularOwl Moon by Jane Yolen- Mentor text for setting leadCharlottes’s Web By: E.B. White- Mentor text for dialogue leadRoar and More! By: Carla Kuskin- Mentor text for onomatopoeias

Room One By Andrew Clements or A Taste of Blackberries, By Doris Buchanan Smith- Mentor text for actionleadThe Grouchy Ladybug by Eric Carle or The Paperboy By Dav Pilkey- Mentor text for circular leadssticky notesWriter’s JournalsAnchor Chart “Good Leads”Anchor Chart “Our Class Leads”Anchors of SupportGood Leads-Setting- It was a cold, winter’s night inthe middle of the snowy field…-Dialogue- “Where’s papa going with thatax?” said Fern to her mother as theywere setting the table for breakfast.-Onomatopoeia--Action-Differentiation StrategiesSpecial Education: Using the students story board, or (graphic organizer), the teacher conferences individually or insmall group to determine which lead is more appropriate for their personal narrative.English Language Learners: Students work together in a small group with the teacher to orally practice the sound ofa lead before writing it. Students offer suggestions to each other to make the lead ‘sound better’.Extension for Learning: Students search for other types of leads (beyond those taught in this lesson.) They can teachthe new leads to the class, after this introductory lesson.21 st Century SkillsCreativity and InnovationThink Creatively Elaborate, refine, analyze and evaluate their own ideas in order to improve and maximize creative efforts.English Language Proficiency Standards:http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/rules/tac/chapter074/ch074a.html#74.4<strong>Lesson</strong> CycleEngageBegin the lesson by introducing the students to leads with the Teaching Leads Powerpoint on the AISD curriculumwebsite.<strong>Lesson</strong> stagesDay 1:1. Explain to students that the lead (beginning or introduction) establishes the direction your writing will take.A good lead grabs your reader's attention and refuses to let go. In other words, it hooks the reader. Notevery type of lead will work for every writer or for every piece of writing. You'll have to experiment withthem. Tell students this week they will learn and practice writing different types of leads. At the end of theweek they will select the one they will choose to use in their personal narratives.2. Tell students we will be thinking about the setting lead today. Read aloud Owl Moon by Jane Yolen anddiscuss with students how the author uses details about the setting to begin her story. Ask students, “What

Day 2:setting words did the author use?” Allow for students to turn and talk about which words the author usedto describe the setting. Call on students to share. Record their examples on the anchor chart next to thewords ‘Setting Lead’.3. The teacher models using the setting lead in his/her piece of writing as the basis for modeling. Think aloudfor the students: The setting of my story is (time and place). If I were to write a setting lead I might write,“It was a hot, sunny, afternoon in the old west Texas town of El Paso.” A discussion takes place at thistime. Ask the students, “How did the setting lead make the story better?” Point out to students that thesetting they describe in the lead should be directly connected to the beginning of their story.4. The students will then refer back to their draft and write a possible setting lead on a sticky note. Studentswill collect their leads in their Writer’s Workshop Notebooks.5. Ask students who have written a strong setting lead to share their lead with the class, to provide additionalexamples for struggling writers.6. At the end of the lesson ask students, “Why is it important to begin a piece of writing with a lead? Howdoes the setting lead improve the piece of writing?” Allow students to turn and talk before sharing.1. Tell students that today we will be focusing on dialogue leads. Begin by asking students, “What areleads/hooks and why do authors use them?” Allow for students to turn and talk before sharing.2. Read aloud, the first page of Charlotte’s Web and discuss with students why this was an effective lead. Askstudents, “Why do you think the author chose to start with dialogue?” Allow students to turn and talk witheach other before sharing. Record ‘Dialogue Lead’ on the anchor chart and the example used in Charlotte’sWeb.3. Show students how authors revise their leads several times before selecting the most effective lead. Thismay be especially helpful for students who claim they already wrote their lead yesterday. Show studentshow E.B. White revised her lead several times before selecting the dialogue lead that was published inCharlotte’s Web. (This link shows a few of her ideas for leads.)4. The teacher will model writing a dialogue lead for his/her personal narrative draft and share it with theclass. An example of a dialogue lead might be: “Why are you eating a tarantula?” my little sister asked.Explain to students that an author always puts the words that the person is saying in quotation marks. Alsoexplain how the author separates the talking and the writing with a comma. Show students how the talkingalways begins with a capital letter, just like when you start a new sentence. (A separate mini lesson forteaching the conventions of dialogue will be necessary.)5. Have students talk to a partner about ideas for dialogue that might make a good lead. Remind them thatthe dialogue should connect to the main part of the story. For example, if the story is about getting a newpuppy, the dialogue might be something like, “Mom, remember that lost puppy we saw yesterday? He wasso sad. It made me want a puppy for a pet. Can we get one?” Does the dialogue have to be the exactwords the characters spoke at the time? No! This is the fun part about writing—we can make up some ofthe details, as long as they sound like they could be real.6. The students will then practice writing a dialogue lead for their personal narrative they are currentlyworking on, on a sticky note.7. The teacher should evaluate the progress students are making by circulating the room and having studentsread their lead. Additionally, it is recommended that some students share their attempts at using thestrategy. You may want to project their statements for others to see how they used quotation marks,commas, and capital letters. This will serve as added examples, particularly for struggling writers. Call

Day 3:Day 4:students to a small group if necessary.8. Allow for students to share their dialogue leads, and place their sticky note on the same page as the settinglead from the day before.9. At the end of the lesson, ask students, “What are some interesting ways that authors begin their writing?How do they improve the piece of writing?” Allow for students to turn and talk before sharing.1. Tell students that today we will be learning about onomatopoeia as a strategy for beginning a piece ofwriting. Explain to students that onomatopoeia is a word that makes the sound the word is describing. Askstudents, “What are some examples of sounds or onomatopoeias that you could use in your writing?”You may want to create an anchor chart to post these words for students to use later. Students can workwith table groups brainstorming some onomatopoeia they already know. They can also look in their librarybooks for examples of onomatopoeia. Give them two minutes to record as many as they can think of on awhite board. After two minutes, students will share, and record on a chart paper. (Examples include: Bam,boink, buzz, moo, snap, crackle, pop, crash, sizzle, ring, achoo, screech, hiss, purr, click, clack)2. Begin by asking, “What are some types of leads you have already learned about, and why do authors usethem in their writing?” Allow for students to turn and talk before sharing.3. Read aloud Roar and More! By Carla Kuskin. Discuss with students and ask, “How does usingonomatopoeia in writing make the writing more interesting?” Allow for students to turn and talk beforesharing. Record ‘Onomatopoeia Lead’ on the anchor chart and some examples from the mentor text.4. The teacher will write a lead using onomatopoeia for the story he/she is writing.5. Have students orally share with a partner a few different ideas for using onomatopoeia in a lead for theirown story. Then they will write the lead they have decided upon on a sticky note to add to their otherpossible leads for this story.6. The teacher should evaluate the progress students are making by circulating the room and asking studentsto read their lead aloud. If students are struggling, call them to a small group.7. Allow time for students to share their leads with their table groups. Each group will decide which one leadthey want to share with the class.1. Begin by asking students, “Which type of lead have you enjoyed most and why?” Allow students to turnand talk. Invite students to share which lead their partner chose and why.2. Tell students that today we will be looking closely at starting with an action lead. Ask students, “What doesthe word action mean? What are some examples of action?” Allow for students to turn and talk beforesharing. This is the perfect time to address the idea that action in writing does not always mean running,jumping and screaming (as in ‘action movies’. ) In writing, action might be sitting at a lake, watching the fishswim slowly in the water near the dock.3. The teacher will read aloud the beginning of the book, Room One, by Andrew Clements. Ask the students,“How is this lead effective or interesting?” Allow students time to turn and talk. Record ‘Action Lead’ onthe lead anchor chart and record the example used in the mentor text.4. The teacher will then model writing an action lead for the same story he/she has been using for the last fewdays.5. At this time students will need to find a buddy. Play music and have students walk around the classroom,

Day 5:when the music stops the person closest to them will be their buddy. Students will take turns reading eachother their drafts and orally practicing what an action lead might sound like for their story. Once everyonehas an idea for their action lead, they will return to their seats and write the action lead for their drafts.6. Monitor the progress of students. The teacher may want to confer with individuals or small groups in orderto assist students with more tailored teacher support with their writing.7. When students have completed writing their action leads, have students place their sticky notes on theirtables and allow students a few minutes to do a gallery walk to read each other’s writing.1. Tell students that today we will be learning how to write a circular lead. Ask students, “What is the rootword you see inside the larger word of ‘circular’?” (circle) “How do you think a lead can create a circle inthe way a story is told?” Accept all ideas from students at this point, explaining that it will make moresense once they hear an example.2. Read aloud Eric Carle’s book, The Grouchy Ladybug. Ask the students, “How did Eric Carle create a circle inhis story?” Allow students to discuss in a turn and talk before sharing. Answer: Eric Carl starts and endswith the two ladybugs arguing, bringing his story all the way around in a full circle. Add ‘Circular Leads’ tothe anchor chart and record the example from the mentor text.3. The teacher will then model how he/she incorporates the full circle lead into his/her story. Start by readingaloud the end of the story and think aloud how you would use this part of the story to start as well. Recordyour new lead on a sticky note and add it to the writing journal with the others.4. This lead may be more difficult than the others for your struggling writers. Use a few struggling writers’stories as examples for the class to brainstorm a circular lead together. This will give the struggling writersan idea of how to write this kind of lead for their story, and it will give extra practice to the other students inthe class.5. Students will then read their own drafts and practice applying this technique to their writing. Students willalso record their lead on a sticky note and add it to the others in their writing journal. Monitor the progressof students and call students who are struggling to a small group if necessary.6. Allow students to share with the class.Closure ActivityStudents will analyze the five different leads they wrote this week. They will select the one that they think is bestand add it to their drafts. They will conference with the teacher and justify why they selected this lead.Check for Understanding (evaluation)Formative: Turn and talks, class discussions and questions, daily post it notes with example of lead taught that daySummative: Students will take turns reading the lead they selected to use in their draft and read it aloud to theclass one at a time. The rest of the class will listen to each lead and decide which type of lead it is, and place it underthe correct column on the chart below. This will be a good anchor of student work examples to post in the class forstudents to refer to in the future.

Our Class LeadsSetting Dialogue Onomatopoeia Action Circular