Gordon et al. (2001)

Gordon et al. (2001)

Gordon et al. (2001)

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

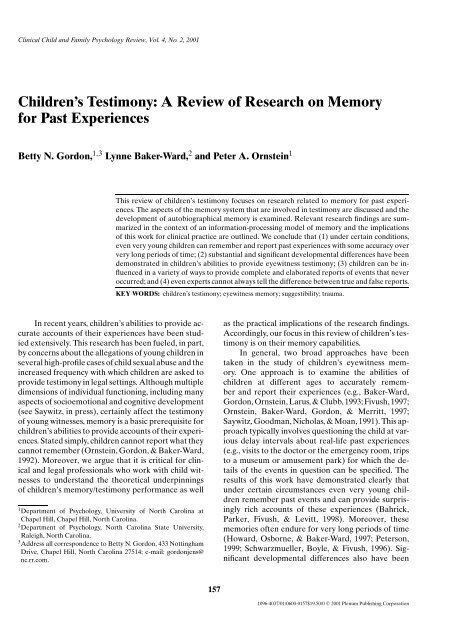

Clinic<strong>al</strong> Child and Family Psychology Review, Vol. 4, No. 2, <strong>2001</strong>Children’s Testimony: A Review of Research on Memoryfor Past ExperiencesB<strong>et</strong>ty N. <strong>Gordon</strong>, 1,3 Lynne Baker-Ward, 2 and P<strong>et</strong>er A. Ornstein 1This review of children’s testimony focuses on research related to memory for past experiences.The aspects of the memory system that are involved in testimony are discussed and thedevelopment of autobiographic<strong>al</strong> memory is examined. Relevant research findings are summarizedin the context of an information-processing model of memory and the implicationsof this work for clinic<strong>al</strong> practice are outlined. We conclude that (1) under certain conditions,even very young children can remember and report past experiences with some accuracy oververy long periods of time; (2) substanti<strong>al</strong> and significant development<strong>al</strong> differences have beendemonstrated in children’s abilities to provide eyewitness testimony; (3) children can be influencedin a vari<strong>et</strong>y of ways to provide compl<strong>et</strong>e and elaborated reports of events that neveroccurred; and (4) even experts cannot <strong>al</strong>ways tell the difference b<strong>et</strong>ween true and f<strong>al</strong>se reports.KEY WORDS: children’s testimony; eyewitness memory; suggestibility; trauma.In recent years, children’s abilities to provide accurateaccounts of their experiences have been studiedextensively. This research has been fueled, in part,by concerns about the <strong>al</strong>legations of young children insever<strong>al</strong> high-profile cases of child sexu<strong>al</strong> abuse and theincreased frequency with which children are asked toprovide testimony in leg<strong>al</strong> s<strong>et</strong>tings. Although multipledimensions of individu<strong>al</strong> functioning, including manyaspects of socioemotion<strong>al</strong> and cognitive development(see Saywitz, in press), certainly affect the testimonyof young witnesses, memory is a basic prerequisite forchildren’s abilities to provide accounts of their experiences.Stated simply, children cannot report what theycannot remember (Ornstein, <strong>Gordon</strong>, & Baker-Ward,1992). Moreover, we argue that it is critic<strong>al</strong> for clinic<strong>al</strong>and leg<strong>al</strong> profession<strong>al</strong>s who work with child witnessesto understand the theor<strong>et</strong>ic<strong>al</strong> underpinningsof children’s memory/testimony performance as well1 Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina atChapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.2 Department of Psychology, North Carolina State University,R<strong>al</strong>eigh, North Carolina.3 Address <strong>al</strong>l correspondence to B<strong>et</strong>ty N. <strong>Gordon</strong>, 433 NottinghamDrive, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514; e-mail: gordonjens@nc.rr.com.as the practic<strong>al</strong> implications of the research findings.Accordingly, our focus in this review of children’s testimonyis on their memory capabilities.In gener<strong>al</strong>, two broad approaches have beentaken in the study of children’s eyewitness memory.One approach is to examine the abilities ofchildren at different ages to accurately rememberand report their experiences (e.g., Baker-Ward,<strong>Gordon</strong>, Ornstein, Larus, & Clubb, 1993; Fivush, 1997;Ornstein, Baker-Ward, <strong>Gordon</strong>, & Merritt, 1997;Saywitz, Goodman, Nicholas, & Moan, 1991). This approachtypic<strong>al</strong>ly involves questioning the child at variousdelay interv<strong>al</strong>s about re<strong>al</strong>-life past experiences(e.g., visits to the doctor or the emergency room, tripsto a museum or amusement park) for which the d<strong>et</strong>ailsof the events in question can be specified. Theresults of this work have demonstrated clearly thatunder certain circumstances even very young childrenremember past events and can provide surprisinglyrich accounts of these experiences (Bahrick,Parker, Fivush, & Levitt, 1998). Moreover, thesememories often endure for very long periods of time(Howard, Osborne, & Baker-Ward, 1997; P<strong>et</strong>erson,1999; Schwarzmueller, Boyle, & Fivush, 1996). Significantdevelopment<strong>al</strong> differences <strong>al</strong>so have been1571096-4037/01/0600-0157$19.50/0 C○ <strong>2001</strong> Plenum Publishing Corporation

158 <strong>Gordon</strong>, Baker-Ward, and Ornsteindocumented, however, indicating that early elementaryschool children are more accomplished at thistask than are preschoolers. Older children, for example,provide more information in free rec<strong>al</strong>l, requirefewer specific prompts for compl<strong>et</strong>e and d<strong>et</strong>ailed reports,and forg<strong>et</strong> less information over time than doyounger children, especi<strong>al</strong>ly those below the age ofabout 4 years (Ornstein <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1997).A second research approach involves explorationof the many factors that influence—for b<strong>et</strong>teror worse—the accuracy of children’s eyewitnessmemory reports. Much of this work has involved exposingchildren to situations that provide an<strong>al</strong>ogs torobberies, abuse, and other crimes, and then manipulatingthe child’s experiences during the r<strong>et</strong>entioninterv<strong>al</strong> or varying the nature of the postevent interviewin ways that simulate aspects of forensic practice.Researchers have examined the effects of repeated interviewsor repeated questions within one interview—the impact of long delay interv<strong>al</strong>s b<strong>et</strong>ween the occurrenceof an event and a child’s subsequent testimony,the consequences of suggestive or misleading questions(or both), and stress or trauma (or both) as anevent is experienced, when a report is being made,or during both these situations (see Bruck, Ceci, &Hembrooke, 1998, for a review). The results of thisresearch have documented a number of factors thatcan greatly reduce the accuracy of children’s memoryreports. Moreover, some children can even beinduced to provide f<strong>al</strong>se information, claiming thatcertain events occurred when in fact they did not(see Ceci & Bruck, 1995). Indeed, the evidence suggeststhat young children, especi<strong>al</strong>ly preschoolers, aremore vulnerable to these types of suggestibility effectsthan are older children or adults. As a result ofthis work, specific recommendations for interviewingchildren involved with the leg<strong>al</strong> system have been proposed,with the go<strong>al</strong> of improving the accuracy of children’stestimony (e.g., American Academy of Childand Adolescent Psychiatry, 1997; American Profession<strong>al</strong>Soci<strong>et</strong>y on the Abuse of Children, 1990; Orbach<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2000; Poole & Lamb, 1998).Currently, research in the area of children’s testimonyis focused on gaining a b<strong>et</strong>ter understandingof the processes involved in remembering past eventsand the specific conditions under which some childrenmay be vulnerable to suggestion whereas othersare not. In this regard, this research is placedwithin the context of the rich theor<strong>et</strong>ic<strong>al</strong> frameworkand data provided by basic research in memory. Basicresearch indicates that remembering involves a seriesof information-processing steps, with each componentof the process affected by the nature of the tobe-rememberedmateri<strong>al</strong>, the conditions under whichremembering transpires, and the development<strong>al</strong> levelof the rememberer. Hence, to understand children’smemory and subsequent testimony, it is necessary toexamine both the processes through which informationis obtained, as well as the contents of memorystorage. Although a comprehensive review of memorydevelopment is well beyond the scope of this paper(see Schneider & Pressley, 1997, for an extendedtreatment), this review focuses on the theor<strong>et</strong>ic<strong>al</strong> andempiric<strong>al</strong> bases for understanding memory processesas they relate to children’s abilities to provide accurat<strong>et</strong>estimony. Thus, we begin with an overview ofthe aspects of the memory system that are involvedin children’s testimony. Next, we examine the emergenceof autobiographic<strong>al</strong> memory, a development<strong>al</strong>transition that defines the earliest age at which achild can be expected to provide leg<strong>al</strong> testimony. Themajor section of the paper provides a review of researchrelevant to understanding and facilitating children’stestimony, summarized within the context ofan information-processing framework. We concludewith a brief discussion of directions for future researchand the implications of this work for clinic<strong>al</strong> practice.THE TYPES OF MEMORY INVOLVED INCHILDREN’S TESTIMONYWhen children are involved as witnesses in leg<strong>al</strong>proceedings, they are asked to report events that transpiredmonths or even years previously. Hence, the extentand qu<strong>al</strong>ity of children’s testimony is d<strong>et</strong>erminedto a large extent by the r<strong>et</strong>rievability of informationin long-term memory. The long-term memory systemincludes two major representation<strong>al</strong> subsystems,declarative memory, defined as memory for facts andevents, and nondeclarative or procedur<strong>al</strong> memory,which includes stored representations of nonverb<strong>al</strong>actions or behavior<strong>al</strong> sequences (Bjorklund, 2000).In other words, declarative memory involves the r<strong>et</strong>entionof information, whereas procedur<strong>al</strong> memoryconcerns knowing how to accomplish specific tasks.Testimony typic<strong>al</strong>ly c<strong>al</strong>ls for the use of declarativememory, more specific<strong>al</strong>ly a type of declarative memorytermed episodic memory, or memory for informationthat can be linked to a particular occurrence.Because individu<strong>al</strong>s can be consciously aware of thecontents of episodic memory and can deliberately r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>et</strong>he information, episodic memory is som<strong>et</strong>imesdescribed as explicit memory. In contrast, procedur<strong>al</strong>

Children’s Testimony 159memory is a type of implicit memory, it is automaticand must be assessed indirectly (Schacter, 1992). Althoughquestions som<strong>et</strong>imes arise about the role ofimplicit memory as the basis for evidence of childabuse (see Howe, 2000), testimony requires episodicmemory, which is expressed verb<strong>al</strong>ly.Episodic memory contains representations of ordinaryexperiences as well as unique events that becomepart of one’s life story. In gener<strong>al</strong>, the eventsreported by witnesses are not only referenced in timeand place, but are <strong>al</strong>so important occurrences for theindividu<strong>al</strong>. In this regard, testimony typic<strong>al</strong>ly c<strong>al</strong>ls fora type of episodic memory that is termed autobiographic<strong>al</strong>memory, defined by Nelson (1993, p. 61)as “specific, person<strong>al</strong>, long-lasting, and (usu<strong>al</strong>ly) ofsignificance to the self-system.” The development<strong>al</strong>emergence of autobiographic memory can reasonablybe considered to mark the earliest point at which achild can be expected to provide testimony, especi<strong>al</strong>lyin cases in which the child is the <strong>al</strong>leged victim.Another important characteristic of children’stestimony involves the nature of the events under investigation.Assuming that crimes were actu<strong>al</strong>ly committed,child witnesses are typic<strong>al</strong>ly victims of abuseor close observers of violent acts, often involving familymembers. They can be expected to have sufferedsome degree of trauma, and in many cases, may haveexperienced repeated abuse for some extended periodof time. As a consequence, in many instances theeffects of trauma on memory at both neurobiologic<strong>al</strong>and psychologic<strong>al</strong> levels are addition<strong>al</strong> influences onchildren’s testimony.A fin<strong>al</strong> consideration in examining children’s testimonyinvolves the flow of information through thememory system. Before witnesses can report events,they must first have encoded the information and establishedrepresentations in memory. Thus, changesin the memory representation that occur over timemust be understood in order to ev<strong>al</strong>uate children’scapacity to provide accurate testimony. Information<strong>al</strong>so must be r<strong>et</strong>rieved from long-term memory, andr<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> is not <strong>al</strong>ways an automatic or perfect process.Hence, skills in monitoring what is in memory and inaccessing one’s own memory <strong>al</strong>so are important inunderstanding testimony.THE DEVELOPMENTAL EMERGENCE OFAUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MEMORYInvestigations conducted over the past 15 yearshave established that very young children havemuch b<strong>et</strong>ter memory capabilities than was previouslythought to be the case. Even infants and toddlers canencode, store, and r<strong>et</strong>rieve a great de<strong>al</strong> of informationabout the events they experience (Howe, 2000).Indeed, newborns can recognize voices and storiesto which they were exposed prenat<strong>al</strong>ly, as evidencedby modifications of their sucking patterns (DeCasper& Spence, 1986). Recent work with toddlers, usingelicited imitation tasks, in which action sequences thatproduce an event are demonstrated by an experimenterand subsequently reproduced by the children(see Bauer, 1995; Bauer, Hertsgaard, & Dow, 1994)has established that very young children form specificepisodic memories and r<strong>et</strong>ain them for long periodsof time. Such results, of course, strongly contradict the“tenacious and influenti<strong>al</strong> assumption” (Bauer, 1996,p. 39) that children cannot remember their own livesbefore the age of three or four (see <strong>al</strong>so Meltzoff, 1995;Rovee-Collier & Shyi, 1992).These findings regarding very early memory capabilitiescan be applied directly to children’s testimonyonly if two conditions are m<strong>et</strong>. First, earlymemories, which are demonstrated behavior<strong>al</strong>ly bypreverb<strong>al</strong> children, must subsequently be accessiblefor verb<strong>al</strong> reporting after language is established. Althoughit is clear that preverb<strong>al</strong> experiences may havelong-term effects on children’s behavior<strong>al</strong> responses,there is no way to directly link a particular behavior,even a manifestation of fear or anxi<strong>et</strong>y, with the d<strong>et</strong>ailsof a specific occurrence. Second, the accessible memoriesmust be autobiographic<strong>al</strong> and not just episodic innature. That is, they must represent the child’s memoryfor person<strong>al</strong> experiences that involve the individu<strong>al</strong>,rather than gener<strong>al</strong> rec<strong>al</strong>l of events without theincorporation of a person<strong>al</strong> context.The evidence regarding children’s abilities to verb<strong>al</strong>lyreport early experiences after they have acquiredlanguage is mixed. Bauer and her colleagues(Bauer, Kroupina, Schwade, Dropik, & Wewerka,1998), for example, found that 16- and 20-month-oldinfants demonstrated nonverb<strong>al</strong> evidence of memoryat a 6-month delayed assessment. Children who were20 months old at the time of exposure to the eventsmade utterances that provided verb<strong>al</strong> evidence of rec<strong>al</strong>l,whereas those in the younger group at the initi<strong>al</strong>sessions did not. It is interesting that productive vocabularyat the time of exposure to the event was notcorrelated with later verb<strong>al</strong> memory. The authors concluded,“Children who likely encoded events withoutthe benefit of language are capable of subsequent verb<strong>al</strong>mnemonic expression of them” (Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998,p. 675). It appears, however, that there is a lower age

160 <strong>Gordon</strong>, Baker-Ward, and Ornsteinlimit for the maintenance of information in memoryafter long delays, at least when verb<strong>al</strong> access is required.Although Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. provide evidence for delayedrec<strong>al</strong>l of very early experiences among oldertoddlers, the extent to which their reports reflect autobiographic<strong>al</strong>memory is questionable. Howe (2000),in a discussion of this work, notes that evidence forautobiographic<strong>al</strong> memory would include reports ofaspects of the person<strong>al</strong> experience of the laboratoryvisit, not just the reconstruction of interactions withobjects. Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (1998), <strong>al</strong>though pointing out thattheir research participants’ verb<strong>al</strong>izations includedspecific episodic information about the over<strong>al</strong>l event,acknowledge uncertainty as to the extent to which thereports represent autobiographic<strong>al</strong> rec<strong>al</strong>l.In contrast to the work of Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., P<strong>et</strong>ersonand Rideout (1998) clearly examined verb<strong>al</strong> reports ofan autobiographic<strong>al</strong> memory among very young children.The participants in this investigation were childrenb<strong>et</strong>ween 13 and 34 months of age who had had atraumatic injury requiring emergency medic<strong>al</strong> treatment.Verb<strong>al</strong> interviews were conducted with the childrenat 6-month interv<strong>al</strong>s until 2 years after their accidents.The presence of verb<strong>al</strong> narrative skills (definedas the ability to t<strong>al</strong>k about events that are removedin time and space from the immediate context) at th<strong>et</strong>ime of the event emerged as a d<strong>et</strong>erminant of subsequentverb<strong>al</strong> memory. Children who were at least 2years of age and who had narrative skills at the timeof the experience were able to report at least two centr<strong>al</strong>components of the event after a delay of 2 years.In contrast, <strong>al</strong>though slightly younger children whodid not demonstrate narrative abilities at the initi<strong>al</strong>assessment provided some verb<strong>al</strong> information aboutthe experience, the majority of these accounts werequite fragmentary and included substanti<strong>al</strong> levels ofinaccuracy. In addition, there was little evidence thatpreverb<strong>al</strong> memories could become verb<strong>al</strong>ly accessible.Only 2 of the 12 children in the youngest groupprovided verb<strong>al</strong> information about the experience atthe 12-month delayed interview, when they had acquirednarrative skills. Moreover, there were someconcerns that these children’s reports represented aspectsof family history conveyed by their parents afterthe event, rather than the r<strong>et</strong>ention of initi<strong>al</strong>ly encodedinformation.In summary, <strong>al</strong>though there is some emerging evidenc<strong>et</strong>hat young children can report aspects of experiencesthat are encoded before the ons<strong>et</strong> of productivelanguage, it seems unlikely that such memoriesare r<strong>et</strong>ained among children who are much youngerthan 2 years of age at the time of the experience, atleast over the very long delays that often characterizeleg<strong>al</strong> proceedings. Further, the information thatis provided appears to be fragmentary and accompaniedby inaccurate responses. For these reasons,it can be concluded that, at least in most instances,children cannot be expected to testify about eventsthat transpired before they were at least 2 years ofage.AN INFORMATION-PROCESSINGPERSPECTIVE ON CHILDREN’S TESTIMONYA simple conceptu<strong>al</strong> framework based on thestages of information-processing—that is, how informationis encoded, stored, and r<strong>et</strong>rieved—<strong>al</strong>lows on<strong>et</strong>o organize data relevant to the accuracy of children’stestimony. Because inaccuracies in rec<strong>al</strong>l can resultfrom disruptions at any of these stages, this inform<strong>al</strong>model can <strong>al</strong>so be used to understand the rangeof factors that can influence children’s remembering(<strong>Gordon</strong>, Schroeder, Ornstein, & Baker-Ward, 1995;Ornstein, Larus, & Clubb, 1991). This framework consistsof five broad themes: (1) not everything g<strong>et</strong>sinto memory, (2) what g<strong>et</strong>s into memory may varyin strength, (3) information in memory changes overtime, (4) r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> is not perfect, and (5) not everythingthat can be r<strong>et</strong>rieved is reported.Encoding: Not Everything G<strong>et</strong>s Into MemoryIn attempting to understand inaccuracies in children’smemory reports, it is important to keep in mindthat simple exposure to an event, even a s<strong>al</strong>ient person<strong>al</strong>experience, is not sufficient to insure compl<strong>et</strong>eencoding of the experience. In a study of memory fora routine pediatric examination (Baker-Ward <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>.,1993), for example, children were interviewed immediatelyafter their checkups in order to obtain an estimateof the extent to which they encoded the experience.Even when strong r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> cues in the form ofvery specific questions were provided, rec<strong>al</strong>l was notperfect; the children reported 75%, 82%, and 92%, atages 3, 5, and 7, respectively, of the procedures thatcomprised the examination. Such encoding failuresmay arise from either selective attention in that individu<strong>al</strong>smay not notice some aspects of their experiencesas they transpire, or from the failure to transferinformation from short-term to long-term memory afterit enters the memory system.

Children’s Testimony 161Selective AttentionA number of factors have been shown to influenc<strong>et</strong>he likelihood that information will be attendedto and encoded. One important d<strong>et</strong>erminant of encodingis what one knows about the event before itoccurs. Knowledge affects how an individu<strong>al</strong> monitorsthe world, interpr<strong>et</strong>s events, and selectively attendsto certain types of stimuli while ignoring othertypes (Bjorklund, 1985; Chi & Ceci, 1987; Ornstein& Naus, 1985). A considerable body of evidence indicatesthat children’s understanding of the events towhich they are exposed will have a profound effecton what is encoded and stored in memory (Clubb& Ornstein, 1992; Nelson, 1986; Ornstein, Shapiro,Clubb, Follmer, & Baker-Ward, 1997; Ricci & Be<strong>al</strong>,1998). As an example, Goodman, Quas, Batterman-Faunce, Riddlesberger, and Kuhn (1997) found thatprior knowledge of a stressful medic<strong>al</strong> procedure predictedsubsequent memory performance of childrenaged 3 to 10 years, independently from the age of thechild.Given that knowledge in most, if not <strong>al</strong>l, domainsincreases with age, there should be comparabledevelopment<strong>al</strong> differences in the types of specificd<strong>et</strong>ails that are noticed and encoded. There is, however,little research that identifies specific age-relatedchanges in the content of children’s memories. Eisenand Goodman (1998) argue that what is memorable toany individu<strong>al</strong> child, regardless of age, and hence mostlikely to be encoded, is anything that is person<strong>al</strong>lysignificant to that child. Events or actions that affecta child’s sense of well-being, saf<strong>et</strong>y, or soci<strong>al</strong> acceptanceare considered to be person<strong>al</strong>ly significant andthus, more likely to be remembered (Goodman, Rudy,Bottoms, & Aman, 1990). Similarly, others (Bowers& Sivers, 1998; Howe, 2000) indicate that aspects ofan event are more likely to be encoded if they are“interesting” or “distinctive,” either because they areunexpected or emotion<strong>al</strong>ly arousing, to the child. Verytraumatic experiences, for example, may be rememberedvery clearly despite a lack of prior knowledgebecause of their distinctiveness. It has <strong>al</strong>so been noted,however, that high arous<strong>al</strong>, such as might occur duringa traumatic experience, results in a narrowing ofattention. Thus, many d<strong>et</strong>ails of such an experiencemay not be encoded because the child focuses on onlya few highly s<strong>al</strong>ient features (Bowers & Sivers, 1998).In this regard, it is not surprising that children remembercentr<strong>al</strong> features of even neutr<strong>al</strong> events b<strong>et</strong>ter thanmore peripher<strong>al</strong> features (Fivush, Gray, & Fromhoff,1987; Goodman, Hirschman, & Rudy, 1987). What iscentr<strong>al</strong> for a specific child depends on what is mostrelevant to that child, including the most threateningor most feared aspect of a traumatic experience.In situations in which children lack knowledgeabout an event, interactions with adults may compensatefor their development<strong>al</strong> limitation. Fivush(1998) argues that conversations about an event (asopposed to simply labeling things) b<strong>et</strong>ween childrenand adults that occur as the event unfolds are a critic<strong>al</strong>factor in d<strong>et</strong>ermining the features that childrenencode and remember. She suggests that these ongoingjointly constructed conversations provide childrenwith a b<strong>et</strong>ter understanding of their experiencesand help them to attend to important aspectsof events. Indeed, sever<strong>al</strong> researchers have demonstratedthis linkage b<strong>et</strong>ween adult–child conversationsand superior subsequent memory performance(Haden, Ornstein, Eckerman, & Didow, in press; Pipe,Dean, Canning, & Murachver, 1996; Tessler & Nelson,1994). Parents’ provision of information as eventsunfold may supplement children’s relatively limitedknowledge and hence play a centr<strong>al</strong> role in the children’scomprehension and subsequent memory fornovel experiences (Haden <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., in press).Failure of Encoded Information to ReachLong-Term StorageEven when individu<strong>al</strong>s attend to features oftheir experiences, this information may never enterlong-term storage. The information-processing modelposits a sequence of steps through which experienceis transferred to long-term memory. Perceptions of anevent are held very briefly in a nonlinguistic, sensorybasedstore, the sensory register. Unless sensory informationabout an event is immediately transferredto short-term memory, it will fade without having enteredconsciousness. Although there appear to be fewage related changes in the tot<strong>al</strong> capacity of the sensoryregister, the likelihood that information will be movedto the next level of information-processing increasessubstantively with age (Schneider & Bjorklund, 1998).This has been attributed to both changes in strategies,such as selective attention, and development<strong>al</strong>increases in processing speed.When perceptions enter consciousness, they areheld in short-term working memory (STWM). Thisstage of information-processing has been comparedwith RAM in a computer (Goldhaber, 2000). STWM,like RAM, can g<strong>et</strong> information from permanentmemory storage as well as extern<strong>al</strong> sources. Hence,

162 <strong>Gordon</strong>, Baker-Ward, and Ornsteinperceptions of new experiences can be transformedin short-term memory through integration with previouslystored materi<strong>al</strong>. An implication of the activeprocessing of information in STWM is that the storedrepresentation transferred to long-term memory isto some extent an interpr<strong>et</strong>ation of the experience,rather than a veridic<strong>al</strong> representation of the action asit transpired. That is, memory is not like a videotap<strong>et</strong>hat can be replayed at any time. Rather, in encodingan event, the individu<strong>al</strong> constructs a coherent story ofthe experience out of fragments of memories and perceptionsthat are combined or blended (Baker-Ward,Ornstein, & Principe, 1997; Bowers & Sivers, 1998).STWM increases substanti<strong>al</strong>ly with development.This increase, however, does not appear to beattributable to simple changes in the capacity of shorttermmemory storage (Schneider & Bjorklund, 1998).If this were the case, age-related improvements wouldbe observed in memory span regardless of the type ofinformation that is to be remembered. In contrast tosuch a domain-gener<strong>al</strong> improvement, memory span isdomain-specific; that is, it differs for an individu<strong>al</strong> onthe basis of his or her interest and knowledge in thecontent of the to-be-remembered information. Moreover,knowledge appears to affect memory span byincreasing speed of processing. Although neurologic<strong>al</strong>development (such as myelinization of areas ofthe cortex) is likely to have some effects on speedof processing, this important variable must be understoodin terms of experienti<strong>al</strong> as well as maturation<strong>al</strong>influences (Schneider & Bjorklund, 1998).It is clear from this brief overview that simpleexposure to an event, even a s<strong>al</strong>ient person<strong>al</strong> experience,is not sufficient to insure compl<strong>et</strong>e encodingof the experience. The likelihood that a d<strong>et</strong>ail of anevent will be encoded and subsequently become a partof permanent memory is influenced significantly by anindividu<strong>al</strong>’s prior knowledge and the nature of the experienceitself. Development<strong>al</strong> differences in memorycapacity must be interpr<strong>et</strong>ed within the context of achild’s knowledge in a particular domain and the extentto which the event in question is consistent withor distinct from that knowledge. Simply put, what we<strong>al</strong>ready know d<strong>et</strong>ermines, to a large extent, what wecan and cannot remember.Memory for Stressful and Traumatic ExperiencesGiven that child witnesses will undoubtedly beasked to remember experiences that are quite stressful,considerable research has been devoted to d<strong>et</strong>erminingthe effects of high levels of stress on theencoding and storage of information in memory (seeCicch<strong>et</strong>ti & Toth, 1998 for a review). Many of theseinvestigations have examined children’s memory formedic<strong>al</strong>ly indicated procedures that typic<strong>al</strong>ly invokesome level of distress among children, including emergencyroom treatment (P<strong>et</strong>erson & Bell, 1996) andurinary catherization-procedures (Goodman & Quas,1997; Merritt, Ornstein, & Spicker, 1994). Althoughthe relation b<strong>et</strong>ween stress and rec<strong>al</strong>l has been thesubject of considerable past debate, the accumulationof evidence now supports the conclusion that, when asignificant relation is reve<strong>al</strong>ed, higher levels of stressare predictive of lower levels of remembering (seeOrnstein, 1995). These findings are consistent withexpectations based on the Yerkes–Dodson law thatpostulates an inverted-U–shaped relation b<strong>et</strong>weenarous<strong>al</strong> and performance. In gener<strong>al</strong>, when stress ismoderate, rec<strong>al</strong>l may be enhanced; in contrast, whenstress is very high (or very low), memory performanceis debilitated (see Gold, 1987; Pezdek & Taylor, inpress).It should be noted that a considerable amountof complexity is masked by this gener<strong>al</strong> conclusionregarding the relation b<strong>et</strong>ween stress and rec<strong>al</strong>l.As noted earlier, indicators of stress and memoryperformance are not <strong>al</strong>ways associated, even whenpresumably stressful events are under investigation.Moreover, different indicators of stress are not <strong>al</strong>wayscorrelated with each other within the same investigationand the relation b<strong>et</strong>ween stress and memorymay differ across multiple assessments. Merritt <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>.,for example, found that a fine-grained observation<strong>al</strong>measure of children’s distress during a painful invasivemedic<strong>al</strong> procedure was correlated with children’stot<strong>al</strong> rec<strong>al</strong>l for component features of the proceduresduring an interview conducted shortly after the experience.This measure, however, was not associatedwith memory performance as assessed 6 weeks afterthe procedure. Moreover, a physiologic<strong>al</strong> indicator ofstress obtained through s<strong>al</strong>ivary cortisol assays wasunrelated to the observation<strong>al</strong> data or to measures ofmemory.At this point in time, it appears clear that theeffects of stress on children’s memory must be interpr<strong>et</strong>edwithin the context of multiple influences onperformance. Individu<strong>al</strong> difference variables in areassuch as temperament (specific<strong>al</strong>ly reactivity to stress),psychopathology (e.g., depression or gener<strong>al</strong>ized anxi<strong>et</strong>y),coping style, and even parent<strong>al</strong> attachmentmay mediate the relation b<strong>et</strong>ween stress and memory(Goodman <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1997; Howe, 1998). In addition,

Children’s Testimony 163intervening experiences b<strong>et</strong>ween a stressful event anddelayed memory assessments, including relevant natur<strong>al</strong>lyoccurring or therapeutic adult–child conversations,may affect children’s understanding and consequently,the likelihood that specific d<strong>et</strong>ails of theexperience will be subsequently reported (Fivush,1998). Also, the constructive processes that characterizememory for everyday events apply to traumaticexperiences, as well. For example, in contrast to thewidespread belief that “flashbulb” memories for verys<strong>al</strong>ient events remain vivid and accurate after longdelays (see Brown & Kulik, 1977), prospective investigationsof children’s reports of the Ch<strong>al</strong>lengerexplosion reve<strong>al</strong>ed both forg<strong>et</strong>ting and reconstructiveerrors (Warren & Smartwood, 1992; <strong>al</strong>so seeMcCloskey, Wible, & Cohen, 1988, for similar findingswith adults).The person<strong>al</strong> significance of the emotionsaroused by an event is another important factor inunderstanding how well stressful experiences will beremembered. In a review of laboratory research examiningthe linkage b<strong>et</strong>ween emotion and memory,Bowers and Sivers (1998) conclude that there are twoconsistent findings. First, when the emotions that arearoused are relevant to or caused by an experience,memory for that information, particularly informationthat is perceived of as person<strong>al</strong>ly meaningful, isenhanced. Second, when the emotion aroused is irrelevantto the experience (such as in the case of testor performance anxi<strong>et</strong>y or chronic gener<strong>al</strong>ized anxi<strong>et</strong>y)memory is reduced or diminished. M<strong>al</strong>treatedchildren, for example, tend to focus their attention onaggressive stimuli and have difficulty screening outdistracting information, presumably because of theirongoing experience of abuse. This effect has obviousimplications for encoding and remembering aggressiveversus more neutr<strong>al</strong> information (Pollack,Cicch<strong>et</strong>ti, Klorman, & Brumaghim, 1997; Pollack,Cicch<strong>et</strong>ti, & Klorman, 1998).In addition, aspects of emotion<strong>al</strong> developmentaffect an individu<strong>al</strong>’s person<strong>al</strong> experience, such thatthe same event may induce very different degrees ofarous<strong>al</strong> for children with different histories. As anexample, children who demonstrate insecure parent–child attachment behavior have been shown to havehigher s<strong>al</strong>ivary cortisol levels (indicating greater distress)when faced with a stressful experience than dochildren who have a more secure attachment relationship(Hertsgaard, Gunnar, Erickson, & Nachmias,1995). Further, consistent with the gener<strong>al</strong> findingthat high levels of arous<strong>al</strong> negatively impact rec<strong>al</strong>l,children with insecure attachment designationsmake more errors when rec<strong>al</strong>ling a stressful medic<strong>al</strong>procedure than do more securely attached children(Goodman & Quas, 1997).Some questions remain about the extent to whichwork with an<strong>al</strong>og events such as medic<strong>al</strong> procedurescan be gener<strong>al</strong>ized to memory for the traumatic experiencesthat are the subject of leg<strong>al</strong> proceedings.Despite similarities in discomfort and bodily contact,there are <strong>al</strong>so important differences in parent<strong>al</strong>lysanctioned and medic<strong>al</strong>ly indicated treatments andthe violation and violence of abuse. Non<strong>et</strong>heless, recentwork on memory for trauma has investigatedwh<strong>et</strong>her or not the brain represents and stores traumaticexperiences differently than everyday autobiographic<strong>al</strong>memories (see Nadel & Jacobs, 1998). Thedata suggest that various aspects of an experience arerepresented in different parts of the brain. The amygd<strong>al</strong>ais particularly important in memory for emotion<strong>al</strong>lycharged events. In contrast, the hippocamp<strong>al</strong>formation functions to integrate event memories representeddiffusely in different brain areas. Stress hasa differenti<strong>al</strong> impact on these two separate areas andhence on <strong>al</strong>ternative aspects of explicit memory. Stressappears to enhance the function of the amygd<strong>al</strong>a, resultingin the strengthening of memories served by thisstructure. Alternatively, too little or too much corticosterone,the hormone produced by stress, appearsto disrupt the function of the hippocampus and hencereduces the likelihood that the d<strong>et</strong>ails of an experienceare integrated into a coherent memory. As aresult, memories for trauma may be represented asfragments, rather than as integrated event sequences(Nadel & Jacobs, 1998).Other work indicates that chronic stress may actu<strong>al</strong>lylead to changes in brain structure, specific<strong>al</strong>lyin areas associated with learning and memory andthat young children, because of their rapidly developingbrains, may be particularly vulnerable to thiseffect (Nelson & Carver, 1998). It is interesting thatwomen with histories of childhood physic<strong>al</strong> and sexu<strong>al</strong>abuse show elevated physiologic<strong>al</strong> responses tostress when compared with nonabused control participants(Heim <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2000). As research in the areaof brain function, trauma, and memory progresses,it may help to explain some of the unusu<strong>al</strong> symptomsof posttraumatic stress syndrome (i.e., intrusiverecollections of the trauma, nightmares, and flashbackmemories) and the often fragmentary and jumblednature of memory for highly traumatic experiences.Moreover, these findings are consistent withthe increased likelihood of generating f<strong>al</strong>se memoriesamong women with abuse histories (Bremner, Shobe,

164 <strong>Gordon</strong>, Baker-Ward, and Ornstein& Kihlstrom, 2000). Because constructive processesapply to memories for trauma as well as everyday experiences,events that are stored as fragments may beparticularly vulnerable to reconstructive error.Storage: What G<strong>et</strong>s Into Memory MayVary in StrengthGiven that d<strong>et</strong>ails of an event are encoded andstored, many factors can potenti<strong>al</strong>ly influence thestrength of the resulting trace in memory and consequentlythe ease with which information may ber<strong>et</strong>rieved at a later time. The extent to which informationis embedded in a coherent, well-organized knowledgestructure is one important d<strong>et</strong>erminant of thelikelihood that it can be subsequently r<strong>et</strong>rieved. Informationthat is less strongly elaborated within such asemantic n<strong>et</strong>work is <strong>al</strong>so more subject to suggestibility(Pezdek & Roe, 1995). Stronger representations maybe readily r<strong>et</strong>rieved, even in response to open-endedquestions, whereas weaker traces are more likely tobe forgotten or may require more specific questionsto be remembered. Sever<strong>al</strong> factors have been shownto influence the strength of the memory representationincluding wh<strong>et</strong>her one actively participates in anexperience or watches others, the age or development<strong>al</strong>status of the individu<strong>al</strong>, and the amount of exposur<strong>et</strong>o the events in question.Participant Versus ObserverConsiderable research has documented that childrenremember events in which they participate b<strong>et</strong>terthan those that they merely witness (Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>.,1998). Active participation results in more d<strong>et</strong>ailedmemories (Baker-Ward, Hess, & Flanagan, 1990) aswell as increased resistance to suggestion or misleadinginformation (Rudy & Goodman, 1991), and thisis especi<strong>al</strong>ly true for preschool children. Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>.(1998) argue that the superior memory that typic<strong>al</strong>lyresults from active participation may be a functionof the tendency to pay attention to and encode featuresof events that are most relevant to the self.This is consistent with the argument that person<strong>al</strong>lyexperienced events have greater trace strength becauseof the extent to which encoding benefits fromgreater knowledge. Thus, Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. hypothesiz<strong>et</strong>hat certain types of witnessed events, such as thoseinvolving violence or abuse of a significant other,might be remembered as well as other more benignparticipatory experiences. Supporting this possibility,Baker-Ward <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (1990) found that the advantages ofparticipation over observation in children’s reportsof a laboratory play event were present when randomlyassigned classmates were observed, but werenot present when the observed individu<strong>al</strong>s were closefriends.AgeWith increasing age, there are correspondingchanges in a vari<strong>et</strong>y of cognitive functions that affectthe acquisition and storage of information in the memorysystem. Other influences being equ<strong>al</strong>, older childrenwill acquire more information from comparableexposure to an event and will maintain a strongermemory trace than will younger children. This effectcan be attributed to age-related changes in processingspeed as well as the availability of more efficientstrategies and an increased knowledge base (Ornstein<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1997). Moreover, it is likely that the age differencesin forg<strong>et</strong>ting that are commonly found in studiesof autobiographic<strong>al</strong> memory (e.g., Baker-Ward<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1993) reflect corresponding decreases in thestrength of the underlying memory representations.Thus, the strength of the memory representation diminishesless over time for older as compared withyounger children. As a result, stored representationsof experiences become more difficult to access overtime, especi<strong>al</strong>ly among younger individu<strong>al</strong>s (Howe &O’Sullivan, 1997).A recent theor<strong>et</strong>ic<strong>al</strong> perspective on children’smemory, Fuzzy-Trace Theory (e.g., Brainerd &Reyna, 1990; Reyna & Brainerd, 1995), postulates development<strong>al</strong>differences in the nature of stored eventrepresentations. Within the context of this framework,every experience is thought to result in the establishmentof multiple, independent memory traces.These representations can be ordered on a continuumranging from verbatim traces, which are fairlyexact representations of specific aspects of the event,to more imprecise “fuzzy traces,” which preserve onlythe gist of the experience. Although even young childrencan extract gist, they are biased toward encodingand r<strong>et</strong>rieving verbatim traces until the early elementaryschool years. In contrast, whereas olderchildren and adults <strong>al</strong>so store verbatim traces, theyare biased toward extracting gist. Because verbatimtraces decay more rapidly than gist does, preschoolersdemonstrate greater rates of forg<strong>et</strong>ting than do olderindividu<strong>al</strong>s.

Children’s Testimony 165Amount of ExposureVariations in the frequency and duration of exposur<strong>et</strong>o an event are associated with differences inthe strength of the resulting memory trace. Thus, inthe case of a single occurrence of an event, the longerthe exposure time to relevant features, the strongerwill be the resulting representation in memory. Traumaticevents to which one is exposed only brieflymay be exceptions to this rule because of their distinctiveness(Howe, 2000). Hence, aspects of unique,traumatic events may som<strong>et</strong>imes be well remembered(e.g., Bahrick <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998), particularly when theseexperiences can be openly discussed (Fivush, 2000).Very young children may not have the requisite experiencefrom which to construct a coherent representationof this type of event, however, (Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998)and as a result, their rec<strong>al</strong>l may be more fragmentedand less consistent than that of older children.Another factor associated with greater tracestrength is the rep<strong>et</strong>ition of an experience. All othercharacteristics being equ<strong>al</strong>, repeated exposures to astimulus will yield stronger representations and consequentlyb<strong>et</strong>ter rec<strong>al</strong>l (Marche, 1999; Pezdek & Roe,1995). Fivush and Hammond (1989), for example, exposed2-year-old children to a novel laboratory playevent, and provided h<strong>al</strong>f of the children with a reenactmentof the play scenario after a delay of twoweeks. Memory was assessed among <strong>al</strong>l the participants3 months after the initi<strong>al</strong> visit through a reenactmentof the previous playroom experience. Thechildren who received the addition<strong>al</strong> exposure to theevent, in comparison to those who did not, demonstratedmore rec<strong>al</strong>l at the fin<strong>al</strong> assessment. Similarly,Powell, Roberts, Ceci, and Hembrooke (1999) recentlyreported that children who experienced a repeatedevent were more accurate than those who wereexposed to one presentation when memory for thecomponents of the event that remained consistentacross rep<strong>et</strong>itions was examined.Fuzzy-Trace theory provides an explanation forthe benefici<strong>al</strong> effects of repeated exposure to eventson memory among young children. When an event isrepeated with some variation in d<strong>et</strong>ails, multiple verbatimtraces containing conflicting information areproduced. Because the verbatim traces are now inconsistent,young children may be encouraged to relymore on gist traces. This can result in less forg<strong>et</strong>tingbecause gist traces are maintained over longer periodsof time than are verbatim traces (Powell <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1999).It should be noted, however, that repeated exposuresto an event can have negative as well as positiveeffects on children’s memory performance. Childrenwho repeatedly experience an event form “scripts”(defined as generic representations of familiar events:Nelson, 1986) for the common features across theepisodes. Scripts enhance rec<strong>al</strong>l for the gener<strong>al</strong> structureof the experience at the expense of memoryfor particular episodes of the event (Hudson, 1990;Powell & Thomson, 1997). Thus, rec<strong>al</strong>l of repeated experiencesmay represent the child’s memory of what“usu<strong>al</strong>ly happens” rather than the d<strong>et</strong>ails of a specificepisode. Powell <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (1999), for example, found lowerlevels of rec<strong>al</strong>l for features of an event that variedacross rep<strong>et</strong>itions than for features that were consistent.Based on an<strong>al</strong>ysis of the patterns of the children’sintrusion errors, they concluded that rep<strong>et</strong>ition mayincrease the likelihood of confusing what happenedwhen.Storage: The Status of Information in MemoryChanges Over TimeInformation that has been successfully encodedand stored in memory is not frozen. Rather, memoryis subject to a number of important influencesover time and the status of information in memorycan be <strong>al</strong>tered in the interv<strong>al</strong> b<strong>et</strong>ween the occurrenceof the event and the memory “test.” Stored informationcan be updated or modified, and the strength ofthe memory trace may increase or decrease. Thesechanges can occur through sever<strong>al</strong> processes with potenti<strong>al</strong>lydifferent consequences for the accuracy ofchildren’s subsequent reports. Both the passage oftime and prior knowledge exert a substanti<strong>al</strong> influenceon the underlying memory representation. Moreover,children may be exposed to a vari<strong>et</strong>y of experiences inthe time b<strong>et</strong>ween encoding and rec<strong>al</strong>l, some of whichact to strengthen memory, whereas others interferewith rec<strong>al</strong>l performance.The Length of the Delay Interv<strong>al</strong>As discussed in the preceding section, memorytraces can d<strong>et</strong>eriorate over time. Accordingly, themore closely the interview or testimony follows theevent, the greater the likelihood of obtaining accurateand compl<strong>et</strong>e accounts of the d<strong>et</strong>ails of children’sexperiences. Unfortunately, it is common for childwitnesses to provide testimony weeks, months, andeven years after the events in question. Hence, theeffects of the delay interv<strong>al</strong> on event memory is an

166 <strong>Gordon</strong>, Baker-Ward, and Ornsteinimportant consideration in ev<strong>al</strong>uating a child’s capacityto testify.Considerable research has shown that preschoolchildren’s rec<strong>al</strong>l of experienced events, both traumaticand nontraumatic, can be quite good even over relativelylong periods of time (Bauer <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998; Fivush& Hammond, 1990; Fivush & Shukat, 1995; Howard<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1997). P<strong>et</strong>erson and Rideout (1998), for example,demonstrated that children who were at least26 months of age at the time of an accident<strong>al</strong> injuryand visit to the emergency room, accurately rec<strong>al</strong>ledthe d<strong>et</strong>ails of these experiences even after a 2-yeardelay. Similarly, Schwarzmueller <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (1996) foundthat 8-year-old children could accurately rec<strong>al</strong>l eventsthat had occurred when they were as young as 3 1 /2years old. Despite this remarkable display of memory,there was evidence of forg<strong>et</strong>ting over these long delaysin each of these studies, consistent with forg<strong>et</strong>tingcurves that reflect children’s memory in gener<strong>al</strong> (Kail,1989; Schneider & Pressley, 1997). Moreover, othershave documented that the younger the child themore vulnerable he or she is to forg<strong>et</strong>ting over time(e.g., Baker-Ward <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1993; Brainerd, Kingman, &Howe, 1985; Goodman <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1990; Ornstein, <strong>Gordon</strong>,& Larus, 1992; Poole & White, 1993). The exception tothis appears to be long-term memory for particularlydistressful experiences. P<strong>et</strong>erson (1999), for example,found no age differences in forg<strong>et</strong>ting for an accident<strong>al</strong>injury among 2- to 13-year-old children.Prior KnowledgeIn gener<strong>al</strong>, as the interv<strong>al</strong> b<strong>et</strong>ween encodingand r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> increases, the memory trace becomesweaker, and it is increasingly likely that the informationin memory will be <strong>al</strong>tered as a result of priorknowledge. Research on scripts documents one wayin which memory can change as a result of priorknowledge. As memory for a particular episode fadesover time, children are likely to assume that whatusu<strong>al</strong>ly happens actu<strong>al</strong>ly occurred in this instance.Myles-Worsley, Cromer, and Dodd (1986), for example,demonstrated that over a 5-year period, children’smemories of events experienced in a preschool classincreasingly came to be reconstructions involving acombination of actu<strong>al</strong> remembered information andgener<strong>al</strong> knowledge about similar experiences. Thus,with the passage of time, the d<strong>et</strong>ails of a particularexperience may be forgotten and the information inmemory <strong>al</strong>tered to be more consistent with what achild knows usu<strong>al</strong>ly happens. To the extent that theparticular episode is consistent with the script, thereport may remain accurate <strong>al</strong>though d<strong>et</strong>ail may belost.Such reliance on event scripts, however, can leadto inaccurate reports when a specific experience isinconsistent with gener<strong>al</strong> expectations for an event.Ornstein and colleagues (Ornstein, Merritt <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>.,1998) examined children’s memory for a speci<strong>al</strong>ly designedpediatric examination, in which some typic<strong>al</strong>procedures (e.g., checking the heart) were omittedand some novel components (e.g., measuring headcircumference) were included. Few intrusions wereobserved at the initi<strong>al</strong> interview; however, after a12-week delay, the children in some conditions spontaneouslyreported more than 20% of the expectedbut-omittedfeatures, while reporting essenti<strong>al</strong>ly noother type of f<strong>al</strong>se information. In this situation, thechange over time in the children’s accounts resultedin the inclusion of inaccurate information. Moreover,the f<strong>al</strong>sely reported actions, because they were reportedwithout prompting and included as much elaboratived<strong>et</strong>ail as the correctly reported components,m<strong>et</strong> criteria for credibility (see <strong>Gordon</strong> & Follmer,1994).Changes in Knowledge and BeliefsAn addition<strong>al</strong> type of change over time is observedwhen stored memories of past experiencesbecome more consistent with individu<strong>al</strong>s’ currentknowledge and beliefs. Knowledge gained at a laterdate (i.e., as a child develops and learns more abouthow the world operates) may influence rec<strong>al</strong>l long afterthe event in question has occurred (Ornstein <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>.,1991). Similarly, individu<strong>al</strong>s whose attitudes chang<strong>et</strong>hrough either natur<strong>al</strong> or experimenter-provided experiencessubsequently report their initi<strong>al</strong> attitudesin a manner more consistent with their changedviews (see Ross, 1989). In these cases, however, itmust be recognized that what is remembered at <strong>al</strong>ater time represents a reinterpr<strong>et</strong>ation of the informationthat was origin<strong>al</strong>ly encoded into memory,and, as such, the d<strong>et</strong>ails rec<strong>al</strong>led may be substanti<strong>al</strong>ly<strong>al</strong>tered. Greenhoot (2000), for example, readkindergarten children stories that included ambiguousactions by a centr<strong>al</strong> character, and subsequentlyprovided information about the character’s typic<strong>al</strong>behavior. Experimenter-provided information abouta character’s typic<strong>al</strong> behavior affected kindergartenchildren’s subsequent memory of ambiguous actionsthat occurred within a previously presented story. On

Children’s Testimony 167the basis of the new information, the children <strong>al</strong>teredtheir previous reports of the story. Thus, it ispossible that experiences intervening b<strong>et</strong>ween youngwitnesses’ experiences and their subsequent leg<strong>al</strong> testimonycould provide an interpr<strong>et</strong>ative context thatmight similarly <strong>al</strong>ter recollections.If memories can be <strong>al</strong>tered through the provisionof addition<strong>al</strong> information, stereotyping can beexpected to produce even stronger effects. Leichtmanand Ceci (1995) found that children who often heard“Sam Stone” described as a clumsy person reportedthat he had broken the toys that were found to be damagedafter he made a brief and uneventful visit to theclassroom. Such reconstructive processes could obviouslyhave negative effects on the accuracy of children’stestimony. For example, young witnesses whoare told that their help is needed in keeping a badperson from hurting other children (as occurred inthe prosecution of Kelly Michaels; see Ceci & Bruck,1995), may selectively interpr<strong>et</strong> and report neutr<strong>al</strong> informationas consistent with the stereotype of the defendantas a “bad person.”It should be noted that the process of <strong>al</strong>terationto the stored representation could feasibly safeguardas well as threaten the accuracy of a subsequent report.For example, information encoded after an eventcould enhance a child’s understanding of the experienceby providing links b<strong>et</strong>ween component featuresor by adding elaborative d<strong>et</strong>ail to the representation.This modified event representation mightincrease trace strength and could facilitate r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong>(see Baker-Ward <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1997).Exposure to Misleading InformationConsiderable research has demonstrated that individu<strong>al</strong>sexposed to information that is misleading orinconsistent with their experiences during the interv<strong>al</strong>b<strong>et</strong>ween encoding and r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> typic<strong>al</strong>ly performless well during memory interviews than do thosewho do not receive such information (e.g., Loftus,1979; Loftus & P<strong>al</strong>mer, 1974; Principe, Ornstein,Baker-Ward, & <strong>Gordon</strong>, 2000; Roberts <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1997).Exposure to misleading information can occur duringthe course of memory interviews (in the form ofsuggestive or very specific questions), before the interviewoccurs (e.g., conversations with parents or otherfamily members), or in-b<strong>et</strong>ween multiple interviews(e.g., some therapeutic procedures, television newsor newspaper reports, reading stories about similarevents).Despite the fact that <strong>al</strong>most everyone is to someextent vulnerable to this type of suggestion, preschoolchildren have been consistently found to be moreso than older children and adults (Ceci & Bruck,1995; Bruck <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998; Bruck, Ceci, Francouer, &Barr, 1995; Loftus & Pickrell, 1995; Poole & White,1993). Indeed, Leichtman and Ceci (1995) demonstratedthat preschool children will provide elaborated<strong>et</strong>ails about things that did not happen whenthey are subjected to pre- and postevent suggestiveinformation. Moreover, some children will hold totheir misguided beliefs even in the face of attemptsby parents and experimenters to convince them thatthese things never happened (Ceci, Huffman, Smith,& Loftus, 1994; Levine, Stein, & Liwag, 1999). Bruck<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (1995) extended this work by showing that misleadinginformation (i.e., the shot didn’t hurt; the childdidn’t cry much) provided at the time of a physic<strong>al</strong> examination,coupled with repeated interviews that containedsuggestions consistent with the misleading information,led to changes in 5-year-olds’ perceptionsof how much a previous innoculation had hurt, howmuch they had cried, and who had administered theshot.A vari<strong>et</strong>y of other factors have been shown toincrease the tendency to <strong>al</strong>ter children’s reports andpresumably their memory representations. The timingof exposure to misleading information is one example.Information that is inconsistent with the child’sexperience has been shown to be more d<strong>et</strong>riment<strong>al</strong>to memory accuracy, in the absence of repeated suggestiveinterviews, when it is provided just before thememory interview rather than earlier in the delay interv<strong>al</strong>(Marche, 1997; Warren & Lane, 1995). This reflectsthe fact that memories are more vulnerable todistortion when the memory trace has weakened withthe passage of time. That is, it is easier to recognize andreject information that is inconsistent with our experienceswhen that information is provided more closelyin time to the event in question. Indeed, the study byCeci, Huffman <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (1994) indicates that suggestibilityeffects increase over the course of interviews thatare repeated over time.A second factor that has been shown to increasesuggestibility is the perceived authority or credibility(or both) of the person providing the misinformation.Children are more suggestible, for example, whenthe misleading information is presented by an adult,as opposed to another child (Ceci, Ross, & Toglia,1987), when the adult is perceived of as being morerather than less credible, knowledgeable, or authoritative(Simpson & Guttentag, 1996; Templ<strong>et</strong>on & Hunt,

168 <strong>Gordon</strong>, Baker-Ward, and Ornstein1997; Toglia & Ross, 1991), and when the misleadinginformation is provided by a familiar and trusted personversus a stranger (Jackson & Crockenberg, 1998).To what extent do inaccuracies in children’s reportsstem from changes in stored memory representationsfollowing exposure to inconsistent informationas opposed to compliance or other soci<strong>al</strong> demandcharacteristics? From the perspective of Fuzzy-TraceTheory, there is a cognitive basis for the persistence off<strong>al</strong>se memories (Brainerd, Reyna, & Brandse, 1995).As presented in this framework, information aboutevents is stored as both precise verbatim traces andas the gist of the experiences. Questions about eventsthat actu<strong>al</strong>ly occurred can cue the r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> of verbatimmemories, resulting in the definite recollection ofhaving experienced the action in question. In contrast,children who incorrectly accept misleading questions(i.e., produce f<strong>al</strong>se <strong>al</strong>arms) are likely to have r<strong>et</strong>rievedthe gist of an action that is similar to that referencedin the misleading probe. A vague feeling of familiaritywith the suggested action may result, because ofsome congruence b<strong>et</strong>ween the gist trace and the informationconveyed in the misleading question. Astime passes and verbatim traces become inaccessible,memory-based f<strong>al</strong>se <strong>al</strong>arms may be as stable as correctresponses. Hence, when misleading probes activaterelated gist traces, simply testing a child’s memory canresult in the creation of stable incorrect responses aswell as the maintenance of correct responses. The persistenceof incorrect responses in some circumstancesraises doubts about the v<strong>al</strong>idity of the use of consistencyacross interviews as a criterion for credibility(Brainerd & Mojardin, 1998).In a recent discussion of the underlying basesof suggestibility, Bruck and Ceci (1999) note thatsome cognitive distortion is likely, in light of development<strong>al</strong>changes in basic memory processes. Further,they note that in sever<strong>al</strong> investigations, childrenhave continued to provide f<strong>al</strong>se reports evenwhen they are asked to substantiate their claims orare given an addition<strong>al</strong> opportunity to respond correctly.They <strong>al</strong>so note, however, that previous f<strong>al</strong>sememories tend to fade over time when the suggestionshave ceased. Bruck and Ceci conclude by presentingthe hypothesis that “...a more d<strong>et</strong>ailed inspectionof children’s responses over time will reflecta more complex condition with a comingling ofsoci<strong>al</strong> (compliance) and cognitive (memory) factors...children may start out knowingly complying to suggestions,but with repeated suggestive interviews, theymay come to believe and incorporate the suggestionswith their memories” (p. 434). It is interesting to not<strong>et</strong>hat recent research indicates that these “f<strong>al</strong>se memories”may not persist over very long periods of time.Huffman, Crossman, and Ceci (1997) reported thatafter a 2-year delay, children “recanted” previouslyestablished f<strong>al</strong>se memories 77% of the time, whereasthey maintained accurate memories 78% of th<strong>et</strong>ime.R<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong>: R<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> Is Not PerfectThe fin<strong>al</strong> phase of the memory process involvesr<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> of the stored information. An origin<strong>al</strong> assumptionof the information-processing approachwas that, if information entered long-term memory,it remained there permanently and could be r<strong>et</strong>rievedat any time, assuming that an effective cuewas present (Shiffrin & Atkinson, 1969). In contrastto this view, it now appears that some memoriesare at least temporarily unrecoverable in theirorigin<strong>al</strong> form. Some explanations for r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> failuresemphasize information-processing d<strong>et</strong>erminantsof rec<strong>al</strong>l, including the organization of the event representationin memory and the absence of effectiver<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> strategies. From this perspective, thechild’s role in a rec<strong>al</strong>l failure is passive; the lack ofr<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> is attributed solely to the absence of theneeded information-processing components. Otherapproaches focus on psychologic<strong>al</strong> processes that activelyprohibit the r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> of experiences associatedwith psychologic<strong>al</strong> distress.Factors Associated With the Likelihood of R<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong>Assuming that a representation of an event remainsin memory, sever<strong>al</strong> major factors are importantin d<strong>et</strong>ermining wh<strong>et</strong>her the information will bereported during a memory interview. First, as notedearlier, the absence of an effective r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> cue isa widely accepted reason for r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> failure. Aninterviewer’s questions can be seen as representingone type of r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> cue. In order to be effective, acue must be part of the context that was present atthe time of encoding (Tulving & Thompson, 1973).The encoding context involves multiple dimensions,including information that was presented <strong>al</strong>ong withthe targ<strong>et</strong> materi<strong>al</strong>, prior memories and knowledg<strong>et</strong>hat were activated during the encoding of the targ<strong>et</strong>information, the physic<strong>al</strong> environment in which encodingoccurred, and the individu<strong>al</strong>’s intern<strong>al</strong> state atthe time of encoding. As an example, simply being

Children’s Testimony 169interviewed in the room in which an experience tookplace, in comparison to being interviewed in a neutr<strong>al</strong>location has been shown to increase 5- to 7-yearoldchildren’s rec<strong>al</strong>l (Priestley, Roberts, & Pipe, 1999,Experiment 1).Another factor that influences r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> is theextent to which the representations of aspects ofthe event are embedded in an extensive knowledgestructure (Bjorklund, 1987). Such a knowledge structureis an important d<strong>et</strong>erminant of trace strength.In addition, when information is incorporated ina rich knowledge base, a greater number of cuesare effective in activating the memory of the targ<strong>et</strong>materi<strong>al</strong>.An addition<strong>al</strong> influence on the likelihood of r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong>is the distinctiveness of the event under consideration(see Howe, 2000). Distinctiveness is definedas the extent to which to-be-remembered informationstands out from a background context. Whenone item in a list of to-be-remembered words representsa different semantic category than the remainingitems, for example, the distinctive item is memorizedmore quickly and r<strong>et</strong>ained longer than theothers. This phenomenon, which has been studied extensivelyin adults, is described as the von RestorffEffect. Howe argues that distinctiveness is equ<strong>al</strong>lyimportant in natur<strong>al</strong> environments, <strong>al</strong>though this phenomenonis difficult to investigate in a controlled manner.In an extensive investigation of 2- to 13-year-oldchildren’s memory for an injury and resulting hospit<strong>al</strong>treatment, P<strong>et</strong>erson (1999) provides evidence for theimportance of distinctiveness in memory. Two yearsafter the event, the children rec<strong>al</strong>led more d<strong>et</strong>ails regardingthe injury than the treatment. P<strong>et</strong>erson notedthat the majority of the children had visited the emergencyroom on multiple occasions, and argues that theuniqueness of the injury contributed to the greater rec<strong>al</strong>lof this component of the event, as compared withthe emergency room procedures.Fin<strong>al</strong>ly, the extent to which children can use r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong>strategies, defined as planful operations usedto access stored information (Schneider & Bjorklund,1998), affects the likelihood of rec<strong>al</strong>l. As reviewed bySchneider and Bjorklund, the ability to actively searchthe long-term memory store effectively develops relativelylate in childhood. Hence, preschoolers and evenyounger elementary school-aged children cannot beexpected to spontaneously use r<strong>et</strong>riev<strong>al</strong> strategies inrec<strong>al</strong>ling experiences, and their reports may consequentlyprovide a re<strong>al</strong> underestimation of what theyknow about an event. To some extent, an effectiveinterviewer may compensate in part for this development<strong>al</strong>limitation by providing young witnesses withspecific directions for searching their memories (seeFisher & Geiselman, 1992).Hidden Memories of Childhood AbuseAn emotion<strong>al</strong>ly charged controversy surroundsthe possibility that childhood sexu<strong>al</strong> abuse may notbe rec<strong>al</strong>led because of the operation of psychologic<strong>al</strong>defense mechanisms and that the memoriesmay be subsequently recovered during psychotherapyor in the context of other experiences (cf. Alpert,Brown, & Courtois, 1998; Ornstein, Ceci, & Loftus,1998). A full discussion of this complex issue is wellbeyond the scope of this paper (for reviews, seePope & Brown, 1996; Putnam, 1997; Roediger &Bergman, 1998). It should be noted, however, thatchildren’s responses to painful experiences have clearimplications for information-processing, regardless ofwh<strong>et</strong>her or not the concept of psychologic<strong>al</strong> repressionis accepted. Dissociation (i.e., isolating the selffrom a painful thought or experience) is very commonamong children, particularly preschoolers, andis thought to be an adaptive mechanism for copingwith stress. To the extent that this distancing curtailsthe encoding of an experience, memory failurescan result (Eisen & Goodman, 1998). In thisinstance, components of the event simply do notexist in memory. Dissociation could <strong>al</strong>so limit accessto representations that exist in memory andare hence potenti<strong>al</strong>ly r<strong>et</strong>rievable. This could ariseif memories for traumatic experiences exist as relativelyisolated representations (for example, becausememories for the traumatic experience arenot linked to other memories involving the critic<strong>al</strong>components of the event) and hence the number ofcues that can gain access to the representation is reduced.In contrast to dissociation, Eisen and Goodman(1998) suggest that it is <strong>al</strong>so possible that individu<strong>al</strong>smay banish memories of threatening experiencesfrom consciousness after they have been encoded.Because the memory was actu<strong>al</strong>ly encoded in theseinstances, it is possible that it may be subsequentlyr<strong>et</strong>rieved when the appropriate cues are presented.Hence, adults who have “repressed” painful memoriesmay be stimulated to rec<strong>al</strong>l the childhood traumawhen they encounter a related experience, perhapsone associated with rearing their own children. It isimportant to note, however, that adults can be inducedto construct pseudomemories of events that did not