Prevalence of Clostridium sPP. in diarrhoeic and healthy dogs ...

Prevalence of Clostridium sPP. in diarrhoeic and healthy dogs ...

Prevalence of Clostridium sPP. in diarrhoeic and healthy dogs ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156<strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. <strong>in</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>healthy</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>Prevalenza di <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. <strong>in</strong> canidiarroici e saniPAROLE CHIAVE:<strong>Clostridium</strong> spp., cane, diarrea, feciKEY WORDS:<strong>Clostridium</strong> spp., diarrhoea, dog, fecesRiassuntoZerb<strong>in</strong>i Laura, Ossipr<strong>and</strong>i Maria Crist<strong>in</strong>aE’ stata effettuata una <strong>in</strong>dag<strong>in</strong>e epidemiologica allo scopo di verificare laprevalenza di <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. nelle feci di cani diarroici e sani. Particolare attenzioneè stata rivolta all’isolamento di ceppi di C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens e C. difficile, dal momentoche questi microrganismi sono stati associati nel cane a s<strong>in</strong>drome diarroica cronica eacuta di tipo emorragico.Il campione oggetto dello studio era composto da cani provenienti dalcanile municipale della città di Parma, da cani appartenenti a studenti e a personaledella Facoltà di Veter<strong>in</strong>aria di Parma, oltre che da cani di proprietà ricoverati pressol’Ospedale Didattico Veter<strong>in</strong>ario.Globalmente, sono stati analizzati mediante esame colturale 95 campionifecali, raccolti nel periodo luglio 2006 - marzo 2007, di cui 36 appartenenti a canidiarroici e 59 a cani non diarroici. Sessantadue dei 95 campioni (65,3%) sono risultatipositivi per la presenza di 1 o più specie di <strong>Clostridium</strong>. Sono stati identificati 89differenti ceppi di <strong>Clostridium</strong>. In particolare, C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens (15,7%) è risultatoessere la specie isolata più frequentemente, seguito da C. bifermentans (13,5%),C. clostridiiforme (13,5%), C. fallax (12,4%), C. beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum (11,2%),C. difficile (11,2%) e C. septicum (9,0%). Altre specie di <strong>Clostridium</strong> sono stateisolate <strong>in</strong> percentuali variabili dal 2,3% all’1,0%.Relativamente all’isolamento di ceppi di C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens, 6 dei 14 campionidi feci risultati positivi appartenevano a cani diarroici (42,9%), mentre nel caso diC. difficile, l’80% dei campioni analizzati e risultati positivi all’esame colturale (8 di10) apparteneva a cani affetti da enterite.Ulteriori <strong>in</strong>dag<strong>in</strong>i, quale la rivelazione della produzione di toss<strong>in</strong>e medianteSezione di Microbiologia ed Immunologia Veter<strong>in</strong>ariaDipartimento di Salute Animale, Facoltà di Medic<strong>in</strong>a Veter<strong>in</strong>aria - Università degli Studi di ParmaVia del Taglio n° 8 - 43100 Parma - Tel. 0521/032718mariacrist<strong>in</strong>a.ossipr<strong>and</strong>i@unipr.it143

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156saggi ELISA e/o la ricerca delle relative sequenze geniche mediante reazioni diamplificazione genica, dovranno essere eseguite sui ceppi di C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens e diC. difficile per poter valutare correttamente le implicazioni e il significatoepidemiologico di questi ritrovamenti nei campioni di feci di cani diarroici e non.AbstractThe purpose <strong>of</strong> this epidemiological study was to evaluate the prevalence<strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. among <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>healthy</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>. Particular attention wasaddressed to C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>and</strong> C. difficile isolation, s<strong>in</strong>ce these microrganisms havebeen associated with acute <strong>and</strong> chronic large <strong>and</strong> small bowel diarrhoea, <strong>and</strong> acutehemorrhagic diarrhoeal syndrome <strong>in</strong> the dog.Some <strong>dogs</strong> were kennelled <strong>dogs</strong>, others belonged to students <strong>and</strong> staff <strong>of</strong>the Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Faculty <strong>of</strong> Parma, <strong>and</strong> others were <strong>dogs</strong> admitted to the DidacticVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Hospital.A total <strong>of</strong> 95 can<strong>in</strong>e fecal samples (36 <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> 59 non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>),collected from July 2006 to March 2007, were analysed by culture assay. Sixty-two <strong>of</strong>the 95 fecal specimens (65.3%) were positive for one or more <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. A total<strong>of</strong> 89 different <strong>Clostridium</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>s were identified. The most common <strong>Clostridium</strong>detected was C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens (15.7%), followed by C. bifermentans (13.5%),C. clostridiiforme (13.5%), C. fallax (12.4%), C. beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum (11.2%),C. difficile (11.2%), <strong>and</strong> C. septicum (9.0%). Other <strong>Clostridium</strong> species were isolated<strong>in</strong> lower percentage, rang<strong>in</strong>g from 2.3% to 1.0%.Relatively to C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens isolation, 6 <strong>of</strong> the 14 positive fecal samples(42.9%) belonged to <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>. In the case <strong>of</strong> C. difficile, the 80.0% (8 <strong>of</strong> 10) <strong>of</strong>can<strong>in</strong>e fecal samples positive by culture assay belonged to <strong>dogs</strong> with enteritis.Further <strong>in</strong>vestigations (concern<strong>in</strong>g, for example, the detection <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong>production by ELISA assays <strong>and</strong>/or the gene revelation by polymerase cha<strong>in</strong> reactions)should be applied on C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>and</strong> C. difficile stra<strong>in</strong>s to assess properly the fullimplications <strong>and</strong> the epidemiological mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> these f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> fecal samples <strong>of</strong><strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>.IntroductionThe development <strong>of</strong> microbiota <strong>of</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>s at birth when the sterile foetusis colonized <strong>in</strong> the birth canal <strong>and</strong> by the immediate environment. The succession <strong>of</strong>events <strong>in</strong> bacterial colonization is similar <strong>in</strong> the human <strong>and</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e, with thevery first colonizers orig<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g from the mother, followed by microbes benefit<strong>in</strong>gfrom breast-feeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> then drastically chang<strong>in</strong>g towards obligate anaerobes <strong>and</strong>heterogeneous flora as solid foods are <strong>in</strong>troduced [10].The gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract <strong>of</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> is colonized by a variety <strong>of</strong> microrganisms.The number <strong>of</strong> microrganisms <strong>in</strong>creases from approximately 10 2 -10 5 colony form<strong>in</strong>gunits (CFU)/g <strong>in</strong> the proximal small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e to 10 5 -10 9 CFU/g <strong>in</strong> the distal small<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>and</strong> then dramatically rises <strong>in</strong> the large <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e to approximately 10 10 -10 11 <strong>in</strong> the colon [1]. This quantitative proximal-distal gradient is accompanied144

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156by complex qualitative changes from a predom<strong>in</strong>antly aerobic flora <strong>in</strong> the small<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e to a predom<strong>in</strong>antly anaerobic flora <strong>in</strong> the large <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e. There is a widevariation <strong>in</strong> the bacterial flora between normal <strong>in</strong>dividuals, <strong>and</strong> concentrations maybe affected by a variety <strong>of</strong> circumstances or behaviours, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g environment, diet,scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> coprophagia. Increased numbers <strong>of</strong> bacteria <strong>in</strong> the small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>ecarry an <strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> a harmful outcome. Whether this is manifest cl<strong>in</strong>ically willdepend on <strong>in</strong>dividual circumstances, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the composition <strong>of</strong> the diet whichbacteria can convert to potentially harmful metabolites. The nature <strong>of</strong> a host responseto the <strong>in</strong>creased load could also be important, <strong>and</strong> this may <strong>in</strong>volve stimulation <strong>of</strong>immunoglobul<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> mucus production, suppression <strong>of</strong> potentially damag<strong>in</strong>g cellmediated immune responses, a compensatory production <strong>of</strong> structural <strong>and</strong> functionalepithelial cell prote<strong>in</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased epithelial cell turnover. The threshold betweenapparent normality <strong>and</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical disease may therefore differ between <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong>be <strong>in</strong>fluenced by a delicate balance between the micr<strong>of</strong>lora <strong>and</strong> the host. Cl<strong>in</strong>icaldisease associated with bacterial overgrowth is a very common problem <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong>occurs when this balance is tipped aga<strong>in</strong>st the host [1].Primary enteric bacterial pathogens can also cause acute cl<strong>in</strong>ical diseases<strong>in</strong>ce they possess virulence factors with adverse effect on the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e. Adherenceto the surface or <strong>in</strong>vasion <strong>of</strong> the mucosa facilitate long-term colonization by certa<strong>in</strong>enteropathogens, predispos<strong>in</strong>g to a carrier status or chronic disease, the outcomeprobably depend<strong>in</strong>g on expression <strong>of</strong> virulence determ<strong>in</strong>ants <strong>and</strong> the host response[1].S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>dogs</strong> are carnivorous, the total length <strong>of</strong> their <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> relation to thebody length is somewhat shorter <strong>and</strong> the motility slower than <strong>in</strong> humans. As a wholethe digestive tract <strong>of</strong> dog, however, resembles that <strong>of</strong> humans <strong>and</strong> the physiologyis similar <strong>in</strong> many ways. Like humans, <strong>dogs</strong> utilize <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al microbiota <strong>in</strong> theirphysiology <strong>and</strong> both are homothermic mammals. The pH values <strong>in</strong> the differentcompartments <strong>of</strong> the digestive tract are also comparable to those <strong>of</strong> human, be<strong>in</strong>g thepH <strong>in</strong> the dog stomach 3, <strong>in</strong> duodenum <strong>and</strong> jejunum 6, <strong>in</strong> ileum 7.5, <strong>in</strong> colon 6.5 <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong> feces 6.2 [10].The ma<strong>in</strong> cultivable bacterial groups <strong>and</strong> most common f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> humans<strong>and</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> are similar, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g clostridia, bacteroides, streptococci, coliforms,enterococci, lactobacilli <strong>and</strong> veillonellae with <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g counts towards the large<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e [10]. Most <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al pathogens cause similar cl<strong>in</strong>ical symptoms <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> as<strong>in</strong> humans (C. difficile, multiresistant Gram-negatives, enterococci, staphylococci).The most common <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al dysfunction <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> is diarrhoea. Another commondisturbance, small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al bacterial overgrowth, compos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Escherichia coli,enterococci <strong>and</strong> clostridia is associated with raised serum folate, reduced serumvitam<strong>in</strong> B12 concentrations <strong>and</strong> altered mucosal permeability <strong>and</strong> function [10].In the most cases <strong>of</strong> bacterial overgrowth, the cause cannot be identified, buthost factors known to predispose to bacterial overgrowth <strong>in</strong>clude defective gastric acidsecretion, <strong>in</strong>terference with normal motility or stasis, <strong>and</strong> defective local immunity[1]. Other factors, as a potentially stressful or contam<strong>in</strong>ed environment, diet <strong>and</strong>coprophagia, may also play a role <strong>and</strong> could contribute to the relatively high numbers<strong>of</strong> bacteria reported <strong>in</strong> kennelled <strong>dogs</strong> [1]. The damag<strong>in</strong>g consequences <strong>of</strong> overgrowth145

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156can <strong>in</strong>volve competition by bacteria for calories <strong>and</strong> essential nutrients, production<strong>of</strong> harmful metabolites, <strong>and</strong> direct damage to the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al mucosa <strong>in</strong>terfer<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al function. Histological changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al biopsies <strong>of</strong> partial villus atrophy<strong>and</strong> lymphocyte/plasma cell <strong>in</strong>filtrate are only present <strong>in</strong> 30% <strong>of</strong> cases, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten themucosal damage cannot be seen by conventional light microscopy [1].Dogs with <strong>and</strong> without signs <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al disease can harbour most <strong>of</strong> theenteric <strong>in</strong>fectious agents [5]. In the case <strong>of</strong> clostridial pathogens, particularly importantare C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>and</strong> C. difficile. The cl<strong>in</strong>ical documentation <strong>of</strong> C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens<strong>and</strong> C. difficile as causes <strong>of</strong> diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> is clouded by the presence <strong>of</strong> thesemicrorganims as a normal component <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>digenous <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al micr<strong>of</strong>lora [6].<strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens<strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens is a Gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-form<strong>in</strong>gbacillus. This microrganism may be one <strong>of</strong> the most widespread pathogen, <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>gthe gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract <strong>of</strong> human be<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> animals as well as terrestrial <strong>and</strong>mar<strong>in</strong>e environments [7]. It has been associated with outbreaks <strong>of</strong> acute, <strong>of</strong>ten severediarrhoea <strong>in</strong> humans, horses, <strong>dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> cats. The elaboration <strong>of</strong> four major tox<strong>in</strong>s,alpha (α), beta (β), iota (ι), <strong>and</strong> epsilon (ε), is the basis for typ<strong>in</strong>g the microrganism<strong>in</strong>to five toxigenic phenotypes (A, B, C, D <strong>and</strong> E).Each type may also express a subset <strong>of</strong> at least 10 other established tox<strong>in</strong>s,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens enterotox<strong>in</strong> (CPE), a well-characterized virulence factorwhose production is co-regulated with sporulation [6]. Although all five types canharbour the enterotox<strong>in</strong> gene (cpe), studies have shown that the overall frequency <strong>of</strong>enterotoxigenic stra<strong>in</strong>s is relatively low (∼5%), with most stra<strong>in</strong>s belong<strong>in</strong>g to typeA. Virtually all stra<strong>in</strong>s isolated from <strong>dogs</strong> are type A, with only one published reportdocument<strong>in</strong>g a type C <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>in</strong> five cases <strong>of</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e peracute lethal hemorrhagicenteritis [7]. Although several studies have shown an association between theimmunodetection <strong>of</strong> CPE <strong>in</strong> fecal specimens <strong>and</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e diarrhoea, the pathogenesis<strong>of</strong> C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> the dog is not fully understood, because CPEis also detected <strong>in</strong> up to 14% <strong>of</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>. Isolation <strong>of</strong> nonenterotoxigenictype A stra<strong>in</strong>s from a <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> specimen does not preclude <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> disease,because there is a plethora <strong>of</strong> other virulence factors that have not been evaluated. One<strong>of</strong> these virulence factors is the recently characterized C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens β2 tox<strong>in</strong>, whichhas been associated with both necrotic enteritis <strong>in</strong> piglets <strong>and</strong> equ<strong>in</strong>e typhlocolitis.<strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens is a part <strong>of</strong> the normal can<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al flora <strong>and</strong>is readily cultured from more than 80% <strong>of</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>.Diarrhoeal diseases associated with C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>in</strong> the dog have primarily beenattributed to CPE, which has been shown to <strong>in</strong>duce fluid accumulation <strong>and</strong> diarrhoea<strong>in</strong> a can<strong>in</strong>e model when adm<strong>in</strong>istered orally or directly <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al lumen[7]. Dogs with C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea frequently exhibit large-boweldiarrhoea characterized by <strong>in</strong>creased frequency <strong>of</strong> bowel movements with tenesmus,fecal mucus <strong>and</strong> hematochezia; however, cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs <strong>of</strong> enteritis or enterocolitisare also commonly seen [6]. Despite the fact that CPE is detected <strong>in</strong> up to 34% <strong>of</strong><strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>, the fact that it is also detected <strong>in</strong> 5% to 14% <strong>of</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>146

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156makes it unclear as to whether or not CPE plays a primary or secondary role <strong>in</strong> thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> diarrhoea. There is currently no gold st<strong>and</strong>ard for the diagnosis <strong>of</strong>can<strong>in</strong>e C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea. It has been well documented that cultureisolation <strong>of</strong> C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens cannot be considered <strong>of</strong> diagnostic value for can<strong>in</strong>eC. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea. Culture may be useful <strong>in</strong> procur<strong>in</strong>g isolates forthe application <strong>of</strong> molecular techniques like PCR for detection <strong>of</strong> specific tox<strong>in</strong> genesor molecular typ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> isolated stra<strong>in</strong>s to establish clonality <strong>in</strong> suspected outbreaks.Two commercially available immunoassays are currently used <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>arydiagnostic laboratories: a reverse passive latex agglut<strong>in</strong>ation assay (PET-RPLA,Oxoid, Bas<strong>in</strong>gstoke, Hampshire, Engl<strong>and</strong>) <strong>and</strong> an enzyme-l<strong>in</strong>ked immunoassay(C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens Enterotox<strong>in</strong> Test, TechLab, Inc., Blacksburg, VA). It is important tonote that the performance characteristics for these assays have not been analyzed <strong>in</strong>the dog, <strong>and</strong> there are concerns about their sensitivities <strong>and</strong> specificities. There havebeen no studies <strong>in</strong> the dog to date to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associateddiarrhoea is a result <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>gestion <strong>of</strong> enterotoxigenic isolates or whether diarrhoea issecondary to disruption <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al microenvironment, enabl<strong>in</strong>g proliferation orsporulation <strong>of</strong> commensal enterotoxigenic C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens. Based on what is currentlyknown, however, it seems more likely that C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea<strong>in</strong>volves commensal isolates [7].<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile is a Gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-form<strong>in</strong>g bacilluswhich is the major cause <strong>of</strong> antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis <strong>in</strong>human patients. It has also been associated with diarrhoea <strong>and</strong> enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> foals<strong>and</strong> adults horses, as well as diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> [6].Three tox<strong>in</strong>s produced by C. difficile have been described: tox<strong>in</strong> A (anenterotox<strong>in</strong>), tox<strong>in</strong> B (a cytotox<strong>in</strong>), <strong>and</strong> C. difficile adenos<strong>in</strong>e diphosphate (ADP)-ribosyltransferase (CDT). Diseases associated with C. difficile have primarily beenattributed to the activity <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong>s A <strong>and</strong> B, <strong>and</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>s have historically been thoughtto produce both tox<strong>in</strong>s (toxigenic isolates) or neither (nontoxigenic). There are<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g reports <strong>of</strong> variant stra<strong>in</strong>s isolated from human cl<strong>in</strong>ical cases <strong>of</strong> C. difficileassociateddisease (CDAD) that produce only tox<strong>in</strong> A or tox<strong>in</strong> B, however [7].Current diagnosis <strong>of</strong> C. difficile-associated diarrhoea is primarilybased upon detection <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> A <strong>and</strong>/or tox<strong>in</strong> B <strong>in</strong> fecal specimensby ELISA. Isolation <strong>of</strong> the microrganism alone is not sufficient fordiagnosis, due to the presence <strong>of</strong> nontoxigenic stra<strong>in</strong>s. In addition,previous studies have reported no significant difference <strong>in</strong> the isolation <strong>of</strong>C. difficile from <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> [6]. Toxigenic C. difficile has beenisolated from <strong>dogs</strong> with chronic diarrhoea, <strong>and</strong> reports have documented a variablecarriage rate <strong>of</strong> C. difficile rang<strong>in</strong>g from 0-40% <strong>in</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>[3]. Despite the lack <strong>of</strong> a significant difference <strong>in</strong> the isolation rates <strong>of</strong> C. difficile <strong>in</strong><strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>, an association has been documented betweenthe presence <strong>of</strong> diarrhoea <strong>and</strong> detection <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> A or tox<strong>in</strong> B, or both, <strong>in</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e fecalspecimens [3].147

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156Antibiotic adm<strong>in</strong>istration, especially <strong>in</strong> hospital environments, is the mostcommonly reported as predispos<strong>in</strong>g factor for the development <strong>of</strong> CDAD <strong>in</strong> people<strong>and</strong> horses, although there have been reports <strong>of</strong> CDAD <strong>in</strong> the absence <strong>of</strong> antibioticadm<strong>in</strong>istration. In contrast, adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> antibiotics does not seem to predispose<strong>dogs</strong> to CDAD [7].Toxigenic C. difficile can be isolated from up to 94% <strong>of</strong> neonate <strong>dogs</strong> <strong>in</strong> theabsence <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs <strong>of</strong> disease. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs that have been associated withcan<strong>in</strong>e C. difficile <strong>in</strong>fection range from asymptomatic carriage to a potentially fatalacute hemorrhagic diarrhoeal syndrome. As with C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens, there does not seemto be a specific anatomic localization <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs, <strong>and</strong> recent studies have shownthat <strong>dogs</strong> with suspected C. difficile-associated diarrhoea commonly have signs<strong>of</strong> small <strong>and</strong> large <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al diarrhoea as well as diffuse disease characterized byconcurrent <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>of</strong> both the small <strong>and</strong> large <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e [7].As with C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens, isolation <strong>of</strong> C. difficile from <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> specimensis <strong>of</strong> little diagnostic value, except for procur<strong>in</strong>g stra<strong>in</strong>s for detection <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> genes<strong>and</strong> typ<strong>in</strong>g. Limitations <strong>in</strong> the isolation <strong>of</strong> C. difficile <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> are underscored by thef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> several studies demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g no significant difference <strong>in</strong> isolation rates(0-40%) between non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>, as above mentioned.Diagnosis <strong>of</strong> C. difficile-associated diarrhoea traditionally has been basedon positive fecal assays for tox<strong>in</strong> A or tox<strong>in</strong> B. The current gold st<strong>and</strong>ard assay isthe cell culture cytotoxicity assay, which detects tox<strong>in</strong> B activity; however, thisassay is expensive <strong>and</strong> requires up to 48 hours for conformation <strong>of</strong> a negative result.There are currently several commercially available immunoassays for detection <strong>of</strong>C. difficile tox<strong>in</strong> A or for detection <strong>of</strong> both tox<strong>in</strong>s A <strong>and</strong> B <strong>in</strong> fecal samples (for example,Premier Tox<strong>in</strong>s A & B, Meridian Bioscience, Inc, C<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>nati, OH; C. difficile TOXA/B II, TechLab, Inc., Blacksburg, VA; ProSpecT <strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile Tox<strong>in</strong> A/B,Remel, USA). Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g reports <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> A-negative <strong>and</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> B-positivestra<strong>in</strong>s isolated from cl<strong>in</strong>ical cases, the use <strong>of</strong> ELISA kits that detect both tox<strong>in</strong>s isga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g preference. None <strong>of</strong> the commercial ELISA kits currently available havebeen validated <strong>in</strong> the dog, however, <strong>and</strong> there is no st<strong>and</strong>ard assay used by veter<strong>in</strong>arydiagnostic laboratories. This fact is concern<strong>in</strong>g, given the wide range <strong>of</strong> specificities(66-100%) <strong>and</strong> sensitivities (33-95%) that have been reported for many <strong>of</strong> the kitswhen analyzed for human fecal tox<strong>in</strong> detection.Detection <strong>of</strong> toxigenic C. difficile stra<strong>in</strong>s after culture has been shown to be <strong>of</strong>little diagnostic value <strong>in</strong> the dog. First, there is no significant difference <strong>in</strong> detection <strong>of</strong>toxigenic stra<strong>in</strong>s between <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>, <strong>and</strong>, second, isolation<strong>of</strong> the microrganism is difficult, costly, <strong>and</strong> time-consum<strong>in</strong>g. Nevertheless, studies <strong>in</strong>human be<strong>in</strong>gs have begun bypass<strong>in</strong>g culture <strong>of</strong> the microrganism <strong>and</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g for thepresence <strong>of</strong> specific tox<strong>in</strong> genes <strong>in</strong> DNA obta<strong>in</strong>ed from fecal specimens. Sensitivities<strong>of</strong> PCR detection methods have been reported to be between 96% <strong>and</strong> 100% whencompared with the cytotoxicity assay [7].The aim <strong>of</strong> this study was to def<strong>in</strong>e the prevalence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. <strong>in</strong>95 fecal samples (36 <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> 59 non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong>) collected from <strong>dogs</strong> at theVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Faculty <strong>of</strong> Parma. Especially, we payed attention to C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>and</strong>C. difficile isolation.148

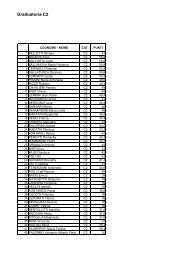

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156Materials <strong>and</strong> methodsFecal samples were collected from 95 <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>,41 female <strong>and</strong> 54 male, over an 8-mo period (20 th July 2006 - 20 th March 2007). Age<strong>of</strong> the <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (n= 36) ranged between 6 months <strong>and</strong> 12 years (mean, 4.2 yr;median, 3 yr), <strong>and</strong> that <strong>of</strong> the non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (n= 59) ranged between 3 months<strong>and</strong> 12 years (mean, 3.8 yr; median, 3 yr).Some <strong>dogs</strong> (n= 38) were kennelled <strong>dogs</strong>; others belonged to veter<strong>in</strong>arystudents <strong>and</strong> staff <strong>of</strong> the Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Faculty <strong>of</strong> Parma (n= 47). Ten <strong>dogs</strong> were admittedto the Didactic Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Hospital.All fecal specimens were naturally voided. Assays were performed on fecescollected with<strong>in</strong> 3 hours. After analysis, samples were immediately stored at -20°C.All fecal samples were cultured onto prereduced blood agar plates,conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g vitam<strong>in</strong>e K, sheep blood <strong>and</strong> haem<strong>in</strong> (Schaedler agar, Oxoid, Bas<strong>in</strong>gstoke,Hampshire, Engl<strong>and</strong>), <strong>and</strong> at the same time <strong>in</strong>oculated <strong>in</strong> Cooked Meat Broth (Oxoid,Engl<strong>and</strong>). Samples were also streaked onto prereduced selective medium conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gcycloser<strong>in</strong>e-cefoxit<strong>in</strong>-fructose agar (CCFA) for the isolation <strong>of</strong> C. difficile. Plateswere <strong>in</strong>cubated anaerobically at 37°C for 48-72 hours. After 72 hours <strong>of</strong> anaerobic<strong>in</strong>cubation <strong>in</strong> Cooked Meat Broth, the samples were subjected to heat shock forspore selection <strong>and</strong> then cultured onto Schaedler agar <strong>and</strong>/or CCFA to enhance sporegerm<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease culture yield.For C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens identification, colonies show<strong>in</strong>g characteristic dualhaemolytic zones (Figure 1) were picked up <strong>and</strong> identified by Gram’s sta<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong>biochemical tests utiliz<strong>in</strong>g Rapid ID 32A (bioMérieux SA, Marcy-l’Etoile, France).Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary identification <strong>of</strong> C. difficile was based on colonial appearance (Figure2), odor (horse manure), lack <strong>of</strong> aerotolerance, cell morphology after Gram sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> typical chartreuse fluorescence under ultraviolet light. F<strong>in</strong>al identification wasperformed by us<strong>in</strong>g a rapid latex slide agglut<strong>in</strong>ation test (C. difficile, Oxoid, Engl<strong>and</strong>)<strong>and</strong> Rapid ID 32A biochemical pr<strong>of</strong>iles (bioMérieux SA, France). The other clostridiawere identified only biochemically (Rapid ID 32A, bioMérieux).All isolates were stored on cryopreservation beads (MAST Diagnostics,D.I.D, Diagnostic International Distribution S.p.A., Italy) at -70°C.Figure 1: Typical colonies <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens onto Schaedler agar show<strong>in</strong>gcharacteristic dual haemolytic zones149

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156Figure 2: Typical colonies <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile that could be greyish or whitishcolour, opaque or lucid, flat, circular or occasionally rhizoid <strong>and</strong> non-haemolyticResultsSixty-two fecal samples were positive for <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. presence(62/95 samples, 65.3%). The other 33 samples were negative for <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp.Eigthy-n<strong>in</strong>e <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. were isolated <strong>and</strong> identified from the 62 positive fecalspecimens. The most common <strong>Clostridium</strong> detected was <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens(14/89 stra<strong>in</strong>s, 15.7%), followed by C. bifermentans (12/89, 13.5%), C. clostridiiforme(12/89, 13.5%), C. fallax (11/89, 12.4%), C. beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum (10/89, 11.2%),C. difficile (10/89, 11.2%), <strong>and</strong> C. septicum (8/89, 9.0%). Other clostridia isolatedwere: 2 stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> C. paraputrificum, 2 <strong>of</strong> C. glycolicum <strong>and</strong> 2 <strong>of</strong> C. tyrobutyricum(2/89, 2.3%), 1 stra<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> C. tetani, 1 <strong>of</strong> C. botul<strong>in</strong>um, 1 <strong>of</strong> C. <strong>in</strong>nocuum, 1 <strong>of</strong> C. tertium, 1<strong>of</strong> C. sporogenes <strong>and</strong> 1 <strong>of</strong> C. histolyticum (1/89, 1.1%). Different species <strong>of</strong> clostridiawere isolated <strong>in</strong> the same fecal sample. In Table 1, the prevalence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp.<strong>in</strong> fecal samples <strong>of</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> is summarized.Concern<strong>in</strong>g C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens, 6 <strong>of</strong> the 14 positive fecal samples (42.9%)belonged to <strong>dogs</strong> with enteritis. In one case, the dog, affected by megaesophagus,was subjected to antibiotic therapy for enteritis <strong>and</strong> C. difficile together withC. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens were also isolated. The other 8 samples (57.1%) belonged to <strong>healthy</strong><strong>dogs</strong> (Table 2).In the case <strong>of</strong> C. difficile isolation, 8 <strong>of</strong> the 10 can<strong>in</strong>e fecal samples (80.0%)belonged to <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>, <strong>of</strong> whom 4 were subjected to antibiotic treatment <strong>and</strong> theenteritis followed the therapy. From one dog (megaesophagus) treated for enteritis,C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens together with C. difficile were isolated. Three <strong>dogs</strong> were not treated.Another dog, admitted to the Didactic Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Hospital, was subjected to antibiotictreatment but was non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong>. One dog was an <strong>healthy</strong> dog (Table 3).150

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156Table 1: <strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp. <strong>in</strong> 95 fecal samples <strong>of</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>healthy</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> <strong>in</strong> the period 20 th July 2006 - 20 th March 2007No. fecal %samplespositive<strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens 10 16.1<strong>Clostridium</strong> bifermentans 6 9.7<strong>Clostridium</strong> fallax 6 9.7<strong>Clostridium</strong> septicum 4 6.44<strong>Clostridium</strong> clostridiiforme 3 4.83<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile 2 3.22<strong>Clostridium</strong> beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> paraputrificum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> glycolicum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> tyrobutyricum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> tetani 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> botul<strong>in</strong>um 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> histolyticum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum <strong>Clostridium</strong> clostridiiforme 3 4.83<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>Clostridium</strong> bifermentans 3 4.83<strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>Clostridium</strong> beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum 2 3.22<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> tertium <strong>Clostridium</strong> septicum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> septicum <strong>Clostridium</strong> beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> tyrobutyricum <strong>Clostridium</strong> <strong>in</strong>nocuum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> clostridiiforme <strong>Clostridium</strong> fallax 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> glycolicum <strong>Clostridium</strong> septicum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> fallax <strong>Clostridium</strong> bifermentans 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> clostridiiforme <strong>Clostridium</strong> paraputrificum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>Clostridium</strong> beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> fallax <strong>Clostridium</strong> septicum 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>Clostridium</strong> bifermentans <strong>Clostridium</strong> 1 1.61clostridiiforme<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>Clostridium</strong> sporogenes 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> bifermentans <strong>Clostridium</strong> fallax <strong>Clostridium</strong> 1 1.61beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum<strong>Clostridium</strong> beijer<strong>in</strong>ckii/butyricum <strong>Clostridium</strong> clostridiiforme 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> fallax<strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>Clostridium</strong> clostridiiforme 1 1.61<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>Clostridium</strong> clostridiiforme 1 1.61Total 62151

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156Table 2: <strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens stra<strong>in</strong>s isolated <strong>in</strong> fecal samples <strong>of</strong><strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>healthy</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>Table 3: <strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile stra<strong>in</strong>s isolated <strong>in</strong> fecal samples <strong>of</strong><strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>healthy</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>DiscussionIn this epidemiological study we assessed the prevalence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp.<strong>in</strong> 95 can<strong>in</strong>e <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> fecal samples. Except for C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens<strong>and</strong> C. difficile, there are not important data <strong>in</strong> literature for the other <strong>Clostridium</strong> spp.On the contrary, C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>and</strong> C. difficile are common causes <strong>of</strong> enteritis <strong>and</strong>enterotoxemias <strong>in</strong> both domestic animals <strong>and</strong> humans. These microrganisms havebeen associated with acute <strong>and</strong> chronic large <strong>and</strong> small bowel diarrhoea, <strong>and</strong> acutehemorrhagic diarrhoeal syndrome <strong>in</strong> the dog [8].In our study, <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens was commonly cultured from feces<strong>of</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (15.7%). Percentages <strong>of</strong> positive cultures were enough similar <strong>in</strong> <strong>healthy</strong><strong>dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (8 <strong>of</strong> 14, 57.1%, versus 6 <strong>of</strong> 14, 42.9%, respectively).This difference is not significant (P= 0.571, Chi-square test). S<strong>in</strong>ce we didn’t assessthe enterotox<strong>in</strong> (CPE) production from C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens isolates, we cannot correlatethe C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens isolation with cl<strong>in</strong>ical disease <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>, also consider<strong>in</strong>g that thismicrorganism may be part <strong>of</strong> the normal flora [6]. Actually, current diagnosis <strong>of</strong>C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> cats is made on detection <strong>of</strong> CPE <strong>in</strong>fecal samples <strong>in</strong> conjunction with cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs <strong>of</strong> disease [6].Relatively to C. difficile, the isolation rates <strong>of</strong> this microrganism from<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (8/10, 80.0%) <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (2/10, 20.0%) were statistically152

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156different (P= 0.023, Fisher’s test). This is <strong>in</strong> disagreement with previous reports <strong>in</strong>which significant differences were not found <strong>in</strong> the isolation rates <strong>of</strong> C. difficilebetween the 2 groups [3]. Four <strong>of</strong> ten C. difficile-positive <strong>dogs</strong> expressed enteritisafter antibiotic therapy. Probably, antibiotic adm<strong>in</strong>istration caused the overgrowth<strong>of</strong> C. difficile <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> the <strong>dogs</strong>, predispos<strong>in</strong>g the animals to enteritis. Infact, a previous study has reported that the carriage rate <strong>of</strong> C. difficile <strong>and</strong> tox<strong>in</strong>s<strong>in</strong> animals <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>dogs</strong> that had recently received antibiotics was higher than<strong>in</strong> the nonantibiotic-treated group, although these differences were not statisticallysignificant [3]. Another study has <strong>in</strong>dicated that the presence <strong>of</strong> C. difficile <strong>in</strong> can<strong>in</strong>efeces was evident only after adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> antibiotic [9]. However, results <strong>of</strong>several studies have supported the notion that antimicrobial treatment is not requiredfor C. difficile-associated disease (CDAD) development <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> [3].S<strong>in</strong>ce we did not research the tox<strong>in</strong>s A <strong>and</strong> B (neither <strong>in</strong> vivo directly <strong>in</strong> fecesnor <strong>in</strong> vitro from the C. difficile isolates), which seem the primary virulence factors<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> CDAD, we cannot correlate the C. difficile isolationwith dog illness. However, we performed on the 10 C. difficile isolates a duplexPCR for the revelation <strong>of</strong> tcdA <strong>and</strong> tcdB genes, encod<strong>in</strong>g for tox<strong>in</strong> A <strong>and</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> B,respectively [11]. The majority <strong>of</strong> C. difficile stra<strong>in</strong>s (6/10, 60.0%) were toxigenic(tcdA+/tcdB+) on the basis <strong>of</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> PCR assay (data not shown). The carriagerates <strong>of</strong> toxigenic isolates <strong>in</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (5/6, 83.3%) were higher than those<strong>in</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> (1/6, 16.7%). However, this difference was not statisticallysignificant (P= 0.08, Fisher’s test).It could be <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to verify if tcdA/tcdB-positive stra<strong>in</strong>s by PCR willbe able to produce the two tox<strong>in</strong>s also <strong>in</strong> vitro, because the presence <strong>of</strong> genes is notalways correlated with their expression.ConclusionsIt is particularly important to seek C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>and</strong> C. difficile presence<strong>in</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e fecal samples. However, C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> the <strong>dogs</strong>eems to be a complex disease, the pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> which is still poorly understood.Furthermore, despite various reports that have documented an association betweenthe detection <strong>of</strong> CPE <strong>and</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> diarrhoea, it is still unclear whether or notC. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens is a primary cause <strong>of</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e diarrhoea or a secondary determ<strong>in</strong>ant.Much work still needs to be done to clarify the exact role <strong>of</strong> C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens <strong>in</strong>can<strong>in</strong>e diarrhoea. Based on the results <strong>of</strong> several studies, the optimum diagnosticapproach for can<strong>in</strong>e C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens-associated diarrhoea is the use <strong>of</strong> a CPE ELISA<strong>in</strong> conjunction with PCR for detection <strong>of</strong> enterotoxigenic stra<strong>in</strong>s procured aftera heat shock or alcohol shock treatment [7]. To date, different PCRs (duplex <strong>and</strong>multiplex) were evaluated for the revelation <strong>of</strong> genes encod<strong>in</strong>g for C. perfr<strong>in</strong>genstox<strong>in</strong>s (CPE, tox<strong>in</strong> α, tox<strong>in</strong> β, tox<strong>in</strong> β2, tox<strong>in</strong> ι <strong>and</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> ε) only for research purposes[2, 4]. It will be useful to evaluate these methods on our isolates for the presence <strong>of</strong>C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens tox<strong>in</strong> genes, especially <strong>of</strong> the CPE gene. The production <strong>in</strong> vivo <strong>and</strong>/or<strong>in</strong> vitro <strong>of</strong> CPE should be also <strong>in</strong>vestigated to correlate the C. perfr<strong>in</strong>gens isolationwith diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>.153

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156C. difficile is a significant enteropathogen <strong>in</strong> human be<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> horses, where<strong>in</strong>fection is most commonly associated with disruption <strong>of</strong> the normal micr<strong>of</strong>lora,followed by colonization by toxigenic stra<strong>in</strong>s. The role that this microrganism plays<strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> is not well def<strong>in</strong>ed, <strong>and</strong> only a few studies evaluat<strong>in</strong>g the presence <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong>s<strong>in</strong> <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-<strong>diarrhoeic</strong> animals have been done [7].There is no consensus between veter<strong>in</strong>ary diagnostic laboratories regard<strong>in</strong>gdiagnosis <strong>of</strong> C. difficile-associated diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> the dog. The apparently highprevalence <strong>of</strong> ELISA-positive, culture-negative can<strong>in</strong>e specimens obta<strong>in</strong>ed withsome assays is questionable, consider<strong>in</strong>g that these commercial assays have neverbeen validated <strong>in</strong> the dog; therefore, such data may represent the consequence <strong>of</strong>false-positive results [7].Ideally, the application <strong>of</strong> PCR assays directly on <strong>diarrhoeic</strong> fecal specimens<strong>and</strong>/or on C. difficile isolated stra<strong>in</strong>s for the detection <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> A <strong>and</strong> B genes comb<strong>in</strong>edwith ELISA tests for the demonstration <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> production (<strong>in</strong> vivo <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> vitro)should be implemented for diagnos<strong>in</strong>g can<strong>in</strong>e CDAD.AcknowledgementsThe authors wish to thank Mrs C<strong>in</strong>zia Reverberi <strong>and</strong> Mr. Roberto Lurisi for theirtechnical support.R<strong>in</strong>graziamentiSi r<strong>in</strong>grazia la sig.ra C<strong>in</strong>zia Reverberi ed il sig. Roberto Lurisi per l’assistenza tecnicaprestata.References1. Batt R.M., Rutgers C. (1997) Bacteria <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al disease <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>. GDBATechnical Review no 11. UK.2. Baums C.G., Shotte U., Amtsberg G., Goethe R. (2004) Diagnostic multiplexPCR for tox<strong>in</strong> genotyp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens isolates. Vet. Microbiol.,100: 11-16.3. Chouicha N., Marks S.L. (2006) Evaluation <strong>of</strong> five enzyme immunoassayscompared with the cytotoxicity assay for diagnosis <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> difficileassociateddiarrhea <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest., 18: 182-188.4. Fach P., Pop<strong>of</strong>f M.R. (1997) Detection <strong>of</strong> enterotoxigenic <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens<strong>in</strong> food <strong>and</strong> fecal samples with a duplex PCR <strong>and</strong> the slide latex agglut<strong>in</strong>ationtest. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 63: 4232-4236.5. Hackett T., Lapp<strong>in</strong> M.R. (2003) <strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong> enteric pathogens <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> <strong>of</strong>North-Central Colorado. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc., 39: 52-56.6. Marks S.L. (2003) Bacterial gastroenteritis <strong>in</strong> <strong>dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> cats. In Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs<strong>of</strong> 28 th World Congress <strong>of</strong> the World Small Animal Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Association.Bangkok, Thail<strong>and</strong>, October 24-27, 2003.7. Marks S.L., Kather E.J. (2003) Bacterial-associated diarrhea <strong>in</strong> the dog: a criticalappraisal. Vet. Cl<strong>in</strong>. Small Anim., 33: 1029-1060.8. Marks S.L., Kather E.J. (2003) Antimicrobial susceptibilities <strong>of</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e154

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156<strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>and</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> perfr<strong>in</strong>gens isolates to commonly utilizedantimicrobial drugs. Vet. Microbiol., 94: 39-45.9. Martirossian G., Sokol-Leszczynska B., Mierzejewski J., Meisel-Mikolajczyk F.(1992) Occurence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile <strong>in</strong> the digestive system <strong>of</strong> <strong>dogs</strong>. Med.Dosw. Mikrobiol., 44: 49-54.10. Mentula S. (2005) Analysis <strong>of</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al <strong>and</strong> fecal microbiota.Prevention <strong>of</strong> ampicill<strong>in</strong>-<strong>in</strong>duced changes with oral β-lactamase. AcademicDissertation. Publication <strong>of</strong> the National Public Health Institute, KTL A8, June2005, 1-85.11. Spigaglia P., Mastrantonio P. (2002) Molecular analysis <strong>of</strong> the pathogenicitylocus <strong>and</strong> polymorphism <strong>in</strong> the putative negative regulator <strong>of</strong> tox<strong>in</strong> production(TcdC) among <strong>Clostridium</strong> difficile cl<strong>in</strong>ical isolates. J. Cl<strong>in</strong>. Microbiol., 40:3470-3475.155

Ann. Fac. Medic. Vet. di Parma (Vol. XXVII, 2007) pag. 143 - pag. 156156