Chapter 3: Summary of the Gross Anatomy of the Extraocular Muscles

Chapter 3: Summary of the Gross Anatomy of the Extraocular Muscles

Chapter 3: Summary of the Gross Anatomy of the Extraocular Muscles

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

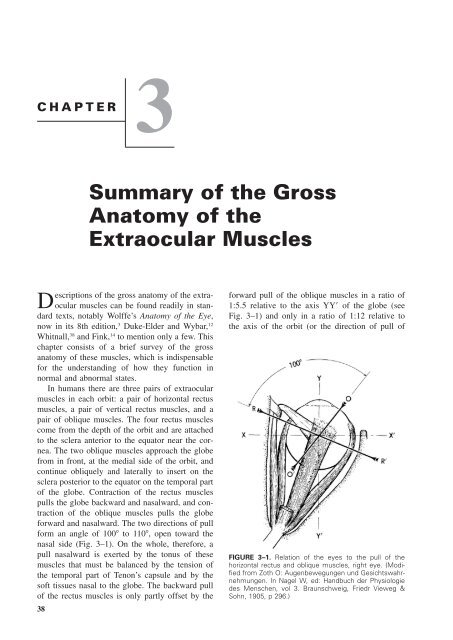

CHAPTER3<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong><strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong>Descriptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gross anatomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocularmuscles can be found readily in standardtexts, notably Wolffe’s <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eye,now in its 8th edition, 3 Duke-Elder and Wybar, 12Whitnall, 38 and Fink, 14 to mention only a few. Thischapter consists <strong>of</strong> a brief survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> grossanatomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se muscles, which is indispensablefor <strong>the</strong> understanding <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong>y function innormal and abnormal states.In humans <strong>the</strong>re are three pairs <strong>of</strong> extraocularmuscles in each orbit: a pair <strong>of</strong> horizontal rectusmuscles, a pair <strong>of</strong> vertical rectus muscles, and apair <strong>of</strong> oblique muscles. The four rectus musclescome from <strong>the</strong> depth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit and are attachedto <strong>the</strong> sclera anterior to <strong>the</strong> equator near <strong>the</strong> cornea.The two oblique muscles approach <strong>the</strong> globefrom in front, at <strong>the</strong> medial side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit, andcontinue obliquely and laterally to insert on <strong>the</strong>sclera posterior to <strong>the</strong> equator on <strong>the</strong> temporal part<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe. Contraction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus musclespulls <strong>the</strong> globe backward and nasalward, and contraction<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oblique muscles pulls <strong>the</strong> globeforward and nasalward. The two directions <strong>of</strong> pullform an angle <strong>of</strong> 100 to 110, open toward <strong>the</strong>nasal side (Fig. 3–1). On <strong>the</strong> whole, <strong>the</strong>refore, apull nasalward is exerted by <strong>the</strong> tonus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>semuscles that must be balanced by <strong>the</strong> tension <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> temporal part <strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule and by <strong>the</strong>s<strong>of</strong>t tissues nasal to <strong>the</strong> globe. The backward pull<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles is only partly <strong>of</strong>fset by <strong>the</strong>38forward pull <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oblique muscles in a ratio <strong>of</strong>1:5.5 relative to <strong>the</strong> axis YY <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe (seeFig. 3–1) and only in a ratio <strong>of</strong> 1:12 relative to<strong>the</strong> axis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit (or <strong>the</strong> direction <strong>of</strong> pull <strong>of</strong>FIGURE 3–1. Relation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes to <strong>the</strong> pull <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>horizontal rectus and oblique muscles, right eye. (Modifiedfrom Zoth O: Augenbewegungen und Gesichtswahrnehmungen.In Nagel W, ed: Handbuch der Physiologiedes Menschen, vol 3. Braunschweig, Friedr Vieweg &Sohn, 1905, p 296.)

<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong> <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> 39FIGURE 3–2. Posterior aspect <strong>of</strong> orbit showing topographic relationship <strong>of</strong> muscle origins in <strong>the</strong>annulus <strong>of</strong> Zinn. N, cranial nerve.<strong>the</strong> rectus muscles). Here again, Tenon’s capsule,fastened to <strong>the</strong> orbital rim and <strong>the</strong> retrobulbartissue, must provide <strong>the</strong> necessary balance. 39Rectus <strong>Muscles</strong>The rectus muscles are more or less flat narrowbands that attach <strong>the</strong>mselves with broad, thin tendonsto <strong>the</strong> globe. There are four <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se muscles:<strong>the</strong> medial (internal), <strong>the</strong> lateral (external), <strong>the</strong>superior, and <strong>the</strong> inferior.The extraocular muscles have delightful synonymsin <strong>the</strong> old anatomical texts, some <strong>of</strong> whichwe cannot refrain from quoting: medial rectus(bibitorius, <strong>the</strong> drinking, because <strong>the</strong> eyes arecrossed while looking at <strong>the</strong> bottom <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cup);lateral rectus (indignatorius, <strong>the</strong> angry); superiorrectus (superbus, <strong>the</strong> proud; pius, <strong>the</strong> pious, because<strong>the</strong> upward turning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes expressesdevotion); inferior rectus (humilis, <strong>the</strong> humble).The superior oblique is also known as pa<strong>the</strong>ticus(<strong>the</strong> pa<strong>the</strong>tic). 26 Powell 31 called <strong>the</strong> oblique musclesamatorii, quod sint velut in amore duces etfurtivum oculorum jactus promoveant (for <strong>the</strong>y areas leaders in love and promote furtive glances <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> eyes).The origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles, <strong>the</strong> superioroblique muscle, and <strong>the</strong> levator muscle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>upper lid are at <strong>the</strong> tip <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbital pyramid.There <strong>the</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscles are arranged in amore or less circular fashion (<strong>the</strong> annulus <strong>of</strong> Zinn),surrounding <strong>the</strong> optic canal and in part <strong>the</strong> superiororbital fissure (Fig. 3–2). Through this ovalopening created by <strong>the</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscles, <strong>the</strong>optic nerve, <strong>the</strong> ophthalmic artery, and parts <strong>of</strong>cranial nerves III and VI enter <strong>the</strong> muscle coneformed by <strong>the</strong> body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles.The interlocking <strong>of</strong> muscle and tendon fibersat <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> origin creates an extremely stronganchoring <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocular muscles. Avulsion <strong>of</strong>a muscle at <strong>the</strong> origin is rare even in cases wheretraction or trauma is sufficiently severe to causeavulsion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> optic nerve. 33 Attachments existbetween <strong>the</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> medial and superiorrecti and <strong>the</strong> dura <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> optic nerve. This explains<strong>the</strong> pain occurring on eye movements in patientswith optic neuritis. 33The medial and lateral rectus muscles follow<strong>the</strong> corresponding walls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit for a goodpart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir course, and <strong>the</strong> inferior rectus muscleremains in contact with <strong>the</strong> orbital floor for onlyabout half its length. The superior rectus muscleis separated from <strong>the</strong> ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit by <strong>the</strong>levator muscle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> upper lid.If <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles were to continue <strong>the</strong>ircourse in <strong>the</strong>ir original direction, <strong>the</strong>y would nottouch <strong>the</strong> globe; but about 10 mm posterior to <strong>the</strong>equator, <strong>the</strong> muscle paths curve toward <strong>the</strong> globera<strong>the</strong>r abruptly and eventually insert on <strong>the</strong> scleraat varying distances from <strong>the</strong> corneal limbus. Thereason for this change in course is musculo-orbitaltissue connections (<strong>the</strong> muscle pulleys; see below).Charpy, 5 quoting Motais, 28 describes howrecurrent fibers may detach <strong>the</strong>mselves from <strong>the</strong>bulbar side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles near <strong>the</strong>ir inser-

40 Physiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sensorimotor Cooperation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> EyesFIGURE 3–3. Insertions <strong>of</strong> rectusmuscles. Average measurements arein millimeters. (Data from Apt L: Ananatomical evaluation <strong>of</strong> rectus muscleinsertions. Trans Am OphthalmolSoc 78:365, 1980.)tion, attaching <strong>the</strong>mselves to <strong>the</strong> sclera 1 to 5mm behind <strong>the</strong> insertions. Scobee 32 called <strong>the</strong>seattachments footplates and attributed considerableimportance to <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> etiology <strong>of</strong> esotropia(see <strong>Chapter</strong> 9).Because <strong>the</strong> insertions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus musclesare not equidistant from <strong>the</strong> corneal limbus, <strong>the</strong>ydo not lie on a circle that is concentric with it butra<strong>the</strong>r on a spiral (<strong>the</strong> spiral <strong>of</strong> Tillaux). The insertion<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> medial rectus muscle is closest to <strong>the</strong>corneal limbus, followed by <strong>the</strong> inferior, lateral,and superior rectus insertions, with <strong>the</strong> superiorrectus insertion being <strong>the</strong> most distant (Fig. 3–3).The lines <strong>of</strong> insertion are generally not straight,but are more or less curved and sometimes evenwavy. The straightest ones are <strong>the</strong> insertions <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> medial and lateral rectus muscles, but <strong>the</strong>setoo are <strong>of</strong>ten slightly convex toward <strong>the</strong> corneallimbus. Fuchs 15 found in 50 cadaver eyes thatin half <strong>the</strong> cases <strong>the</strong> horizontal meridian cut <strong>the</strong>insertions symmetrically. For <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cases,up to two thirds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> width <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tendon <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>medial rectus muscle was above <strong>the</strong> horizontalmeridian and that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lateral rectus muscle wasbelow it. Fuchs found also that <strong>the</strong> insertion line <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se muscles was perpendicular to <strong>the</strong> horizontalmeridian in less than half <strong>the</strong> eyes. In <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs<strong>the</strong> insertion lines ran obliquely up and in, in <strong>the</strong>case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> medial rectus, and up and out, in <strong>the</strong>case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lateral rectus.The lines <strong>of</strong> insertion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior and inferiorrectus muscles are markedly convex toward<strong>the</strong> corneal limbus and run obliquely upward andlaterally. The rounded, temporal ends <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir insertions<strong>the</strong>refore are more distant from <strong>the</strong> corneallimbus than <strong>the</strong>ir nasal ends. The amount <strong>of</strong>obliquity varies in different eyes but is usuallymarked and, according to Fuchs, 15 is usually <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> same degree for <strong>the</strong> two muscles <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sameeye. The lines <strong>of</strong> insertion are cut asymmetricallyby <strong>the</strong> vertical meridian. The greater part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>tendon (two thirds <strong>of</strong> its width according to Fuchs)<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior rectus lies temporal to <strong>the</strong> meridian.In one third <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes, Fuchs found that<strong>the</strong> meridian bisected <strong>the</strong> inferior rectus tendon;o<strong>the</strong>rwise, <strong>the</strong> larger segment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion linewas found to lie lateral to it.The normal distance between muscle insertionand limbus is <strong>of</strong> importance during operationsand reoperations on <strong>the</strong> extraocular muscles. Databased on measurements taken by Apt 1 from cadavereyes <strong>of</strong> adult subjects (mean age, 60.3 years)are shown in Figure 3–3 and Table 3–1. Theanterior limbus was defined by Apt as <strong>the</strong> transitionfrom clear cornea to gray and <strong>the</strong> posteriorlimbus as <strong>the</strong> transition from gray cornea to whitesclera. While <strong>the</strong> means are similar to those <strong>of</strong>ano<strong>the</strong>r recent study, 23 <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> variations betweendata reported elsewhere in <strong>the</strong> literature isremarkable. 15, 16, 22, 24, 35 The experienced surgeon isaware how <strong>of</strong>ten differences <strong>of</strong> several millimetersfrom <strong>the</strong> norms shown in Figure 3–3 can be found.

<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong> <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> 41TABLE 3–1. Distance from Limbus to Rectus Muscle InsertionsMean SD (mm)Range (mm)Medial rectus insertionAnterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 5.3 0.7 3.6–7.0Posterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 4.7 0.6 3.0–6.4Inferior rectus insertionAnterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 6.8 0.8 4.8–8.5Posterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 5.9 0.8 3.9–7.6Lateral rectus insertionAnterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 6.9 0.7 5.4–8.5Posterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 6.3 0.6 4.8–7.9Superior rectus insertionAnterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 7.9 0.6 6.2–9.2Posterior limbus to midpoint <strong>of</strong> insertion 6.7 0.6 5.0–8.0From Apt L: An anatomical evaluation <strong>of</strong> rectus muscle insertions. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 78:365, 1980.Since a topographic correlation exists between<strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tendon insertion and <strong>the</strong> oraserrata and since <strong>the</strong> distance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ora from <strong>the</strong>limbus depends on <strong>the</strong> anteroposterior diameter <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> globe, 36, 37 <strong>the</strong> distance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tendon from <strong>the</strong>limbus may be influenced by age and axial refractiveerrors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye. 15 If <strong>the</strong>se variations in <strong>the</strong>location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion are not taken into account(see Table 3–1), <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> geometric calculationsin predicting <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> surgery on <strong>the</strong>action <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocular muscles is limited. Forinstance, <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> a 4-mm muscle recessionwill vary significantly with <strong>the</strong> distance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>anatomical insertion from <strong>the</strong> limbus. These considerationsapply especially when considering <strong>the</strong>effect <strong>of</strong> muscle surgery in infants. Table 3–2shows a substantial difference in mean anatomicaldata obtained from adult and newborn eyes. Accordingto Souza-Dias and coworkers, 35 age differ-TABLE 3–2. Comparative Measurements <strong>of</strong>Medial and Lateral Rectus <strong>Muscles</strong> in Adults*and Newborns†MedialRectusMuscleLateralRectusMuscleLength 37.7 (28)‡ 36.3 (31.6)Width 10.4 (7.9) 9.6 (6.9)Distance from limbus 5.7 (3.9) 7.5 (4.8)(middle <strong>of</strong> insertion)*Data from Lang J, Horn T, Eichen U von den: Über die äusserenAugenmuskeln und ihre Ansatzzonen. Gegenbaurs MorpholJahrb 126:817, 1980.†Data Weiss L: Über das Wachstum des menschlichen Augesund über die Veränderungen der Muskelinsertionen am wachsendenAuge. Anat Hefte 25 (pt 1):191, 1897; Schneller F:Anatomisch-physiologische Untersuchungen über die AugenmuskelnNeugeborener. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol47:178, 1899.‡Measurements from newborn in paren<strong>the</strong>ses.ences in <strong>the</strong> distance between limbus and insertioncan be neglected in strabismus operations in childrenolder than 6 months. In view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that<strong>the</strong> longitudinal growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye is not completedby that age, we take a more conservativeview and would put <strong>the</strong> age at which adult dosages<strong>of</strong> strabismus surgery may be applied at 2 yearsand older.The length <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles exclusive <strong>of</strong>tendon is fairly constant, but <strong>the</strong>re are variationsbetween <strong>the</strong> width <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion and <strong>the</strong> length<strong>of</strong> tendon <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> different muscles (Table 3–3).O<strong>the</strong>r anatomical data <strong>of</strong> importance to <strong>the</strong> kinematics<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye are discussed in <strong>Chapter</strong> 4.Muscle PulleysModern imaging techniques such as computed tomography(CT) scanning 34 and magnetic resonanceimaging (MRI) 6, 10, 27 have revealed that <strong>the</strong>paths <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles remain fixed relativeto <strong>the</strong> orbital wall during excursions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globeand even after large surgical transpositions. 7, 8Only <strong>the</strong> anterior aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle moves with<strong>the</strong> globe relative to <strong>the</strong> orbit, as it must on account<strong>of</strong> its scleral attachment. In o<strong>the</strong>r words,<strong>the</strong>re is no sideslip <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles in relationto <strong>the</strong> orbital walls when <strong>the</strong> eye moves fromprimary into secondary gaze positions (Fig. 3–4).Demer and coworkers 10 suspected from <strong>the</strong>sefindings that <strong>the</strong>re must be musculo-orbital couplingthrough tissue connections that constrain <strong>the</strong>muscle paths during rotations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe. Subsequentstudies with high-resolution MRI confirmedthis notion by demonstrating retroequatorial inflections<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscle paths 6, 10 (Fig. 3–5).<strong>Gross</strong> dissection <strong>of</strong> orbits and histologic and histo-

42 Physiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sensorimotor Cooperation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> EyesTABLE 3–3. Means and Range (in paren<strong>the</strong>ses) <strong>of</strong> Measurements <strong>of</strong> Rectus <strong>Muscles</strong> (mm)*MedialSuperiorRectus Inferior Rectus Lateral Rectus RectusMuscle Muscle Muscle MuscleLength† 37.7 (32.0–44.5) 37.0 (33.0–42.5) 36.3 (27.0–42.0) 37.3 (31.0–45.0)Length <strong>of</strong> tendon 3.0 (1.0–7.0) 4.7 (3.0–7.0) 7.2 (4.0–11.0) 4.3 (2.0–6.0)Width <strong>of</strong> tendon 10.4 (8.0–13.0) 8.6 (7.0–12.0) 9.6 (8.0–13.0) 10.4 (7.0–12.0)From Lang J, Horn T, Eichen U von den: Über die äusseren Augenmuskeln und ihre Ansatzzonen. Gegenbaurs Morphol Jahrb126:817, 1980.*Data from right eye.†Exclusive <strong>of</strong> tendon.chemical studies 10, 30 showed that <strong>the</strong>se inflectionsare caused by musculo-orbital tissue connectionsin <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> fibroelastic sleeves that consist<strong>of</strong> smooth muscle, collagen, and elastin. Duringcontraction <strong>the</strong> muscles travel through <strong>the</strong>sesleeves which act as pulleys by restraining <strong>the</strong>muscle paths. The orbital layer <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscleinserts directly on <strong>the</strong> pulley, whereas <strong>the</strong>global layer continues anteriorly to insert into<strong>the</strong> sclera.These pulleys are located in a coronal planeanterior to <strong>the</strong> muscle bellies and about 5 to 6 mmposterior to <strong>the</strong> equator. They are compliant ra<strong>the</strong>rthan rigid, receive rich innervation involving numerousneurotransmitters in humans and monkeys,9, 11 and change <strong>the</strong>ir positions as a function<strong>of</strong> gaze direction. For instance, <strong>the</strong> pulleys <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>horizontal rectus muscle move posteriorly duringmuscle contraction. 8 This adjustability <strong>of</strong> pulleypositions and <strong>the</strong> different insertion sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>global and orbital layers <strong>of</strong> extraocular musclesmay play a major but still undefined role in ocular8, 9, 30kinematics.The demonstration <strong>of</strong> muscle pulleys is incom-patible with <strong>the</strong> classic view according to which<strong>the</strong> direction <strong>of</strong> pull <strong>of</strong> a rectus muscle is determinedby its functional insertion at <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong>tangency with <strong>the</strong> globe and its origin at <strong>the</strong>annulus <strong>of</strong> Zinn. 10 Actually, <strong>the</strong> functional origin<strong>of</strong> a rectus muscle is located at its pulley. Itfollows that atypical location <strong>of</strong> a pulley (see<strong>Chapter</strong> 19) or pathologic conditions that mayinfluence pulley function may cause certain forms<strong>of</strong> strabismus. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> finding <strong>of</strong> stability<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle paths during excursions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globethrough muscle pulleys may change our conceptsabout <strong>the</strong> function <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles in tertiarygaze. Fur<strong>the</strong>r reference to <strong>the</strong> muscle pulleys ismade in <strong>the</strong> appropriate sections <strong>of</strong> this book.Oblique <strong>Muscles</strong>From its origin above and medial to <strong>the</strong> opticforamen, <strong>the</strong> superior oblique muscle courses anteriorlyin a line parallel with <strong>the</strong> upper part <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> medial wall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit, reaching <strong>the</strong> trochleaat <strong>the</strong> angle between <strong>the</strong> superior and medial wall.FIGURE 3–4. Two-mm-thick,320-m resolution axial MRI scan<strong>of</strong> a normal left orbit showing <strong>the</strong>inflection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> horizontal rectusmuscles as <strong>the</strong>y pass through<strong>the</strong>ir respective pulleys during abductionand adduction. MR, medialrectus; LR; lateral rectus.(From Demer JL: Orbital connectivetissue in binocular alignmentand strabismus. In LennerstrandG, Ygge J, eds: Advances in Strabismus,Proceedings <strong>of</strong> InternationalSymposium at <strong>the</strong> Wenner-Gren Center, Stockholm, June1999. London, Portland Press,2000, p 17.)

<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong> <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> 43FIGURE 3–5. Two-mm-thick, 320-m resolution axial MRI scan <strong>of</strong> normal left orbit in primary andsecondary gaze positions, showing near constancy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> positions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles posteriorto <strong>the</strong> pulleys. IR, inferior rectus; SR, superior rectus; MR, medial rectus; LR, lateral rectus; ON,optic nerve. Note stability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> coronal sections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles but movement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> section<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> optic nerve in secondary gaze postions. (Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Dr. J.L. Demer, Los Angeles.)The trochlea is a tube 4 to 6 mm long formed inits medial aspect by bone (<strong>the</strong> trochlear fossa <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> frontal bone). The rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> circumference iscomposed <strong>of</strong> connective tissue that may containcartilaginous or bony elements. After passing <strong>the</strong>trochlea, <strong>the</strong> superior oblique muscle turns in laterodorsally,forming an angle <strong>of</strong> about 54 with<strong>the</strong> pretrochlear or direct portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle.A fibrillar, vascular sheath surrounds <strong>the</strong> intratrochlearsuperior oblique tendon. This portion <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> tendon consists <strong>of</strong> discrete fibers with fewinterfibrillar connections, as reported by Helvestonand coworkers. 21 Each fiber <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tendon movesthrough <strong>the</strong> trochlea in a sliding, telescoping fashionwith <strong>the</strong> central fibers undergoing maximaland <strong>the</strong> peripheral fibers <strong>the</strong> least excursion. Thetotal travel <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> central fibers appears to be 8mm in ei<strong>the</strong>r direction. 20Helveston and coworkers 21 also described abursa-like structure lying between <strong>the</strong> trochlear‘‘saddle’’ and <strong>the</strong> vascular sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superioroblique tendon and postulated that pathologic alterations<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bursa may be a factor in <strong>the</strong>etiology <strong>of</strong> Brown syndrome (see <strong>Chapter</strong> 21).At about <strong>the</strong> distal third <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> direct portion(10 mm behind <strong>the</strong> trochlea), <strong>the</strong> muscle becomestendinous and remains tendinous in its entire posttrochlearor reflected part. The tendon passes under<strong>the</strong> superior rectus muscle, fans out, andmerges laterally with <strong>the</strong> sclera to <strong>the</strong> vertical

44 Physiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sensorimotor Cooperation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eyesinsertion forms a curved concave line toward <strong>the</strong>origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle. Its anterior margin is about10 mm behind <strong>the</strong> lower edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> lateral rectus muscle; its posterior end is 1 mmbelow and 1 to 2 mm in front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> macula (Fig.3–7). Near its insertion <strong>the</strong> posterior border <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>muscle is related to <strong>the</strong> inferior vortex vein.Unlike <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r extraocular muscles, especially<strong>the</strong> superior obliques, which have both muscularand tendinous components, <strong>the</strong> inferioroblique is almost wholly muscular. It forms anangle <strong>of</strong> about 51 with <strong>the</strong> vertical plane <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>globe.FIGURE 3–6. Relationships <strong>of</strong> tendons <strong>of</strong> superioroblique muscle. Measurements are in millimeters. (Modifiedfrom Fink WH: Surgery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vertical <strong>Muscles</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Eyes, ed 2. Springfield, IL, Charles C Thomas, 1962.)meridian, forming a concave curved line toward<strong>the</strong> trochlea (Fig. 3–6). The anterior end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>insertion lies 3.0 to 4.5 mm behind <strong>the</strong> lateral end<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior rectus muscle and13.8 mm behind <strong>the</strong> corneal limbus. The posteriorend <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion lies 13.6 mm behind <strong>the</strong>medial end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior rectusmuscle and 18.8 mm behind <strong>the</strong> corneal limbus.The width <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior obliquemuscle varies greatly (from 7 to 18 mm, Fink 14 )but is 11 mm on average. The medial end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>insertion lies about 8 mm from <strong>the</strong> posterior pole<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe. Near its insertion <strong>the</strong> posterior border<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle is related to <strong>the</strong> superior vortex vein.The length <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> direct part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superioroblique muscle is about 40 mm and that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>reflected tendon is about 19.5 mm. From a physiologicand kinematic standpoint, <strong>the</strong> trochlea is <strong>the</strong>origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle.The inferior oblique muscle is <strong>the</strong> shortest <strong>of</strong>all <strong>the</strong> eye muscles, being only 37 mm long. Itarises in <strong>the</strong> anteroinferior angle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bony orbitin a shallow depression in <strong>the</strong> orbital plate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>maxilla near <strong>the</strong> lateral edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entrance into<strong>the</strong> nasolacrimal canal. The origin is readily locatedby drawing a perpendicular line from <strong>the</strong>supraorbital notch to <strong>the</strong> lower orbital margin.The muscle continues from its origin backward,upward, and laterally, passing between <strong>the</strong> floor<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit and <strong>the</strong> inferior rectus muscle. Itinserts by a short tendon (1 to 2 mm) in <strong>the</strong>posterior and external aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sclera. Thewidth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertion varies widely (5 to 14 mm,Fink 14 ) and may be around 9 mm on average. TheFascial SystemTenon’s CapsuleThe eyeball is suspended within <strong>the</strong> orbit by asystem <strong>of</strong> fasciae. The way in which this isachieved represents an ideal solution to <strong>the</strong> problem<strong>of</strong> suspending a spheroid body in a coneshapedcavity. The bulk <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> system is made up<strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule, which is a condensation <strong>of</strong>fibrous tissue that covers <strong>the</strong> eyeball from <strong>the</strong>entrance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> optic nerve to near <strong>the</strong> corneallimbus, where it is firmly fused with <strong>the</strong> conjunctiva.Except for this area <strong>of</strong> fusion, <strong>the</strong> two structuresare separated by <strong>the</strong> subconjunctival space.Tenon’s capsule is also separated from <strong>the</strong> sclera.Between <strong>the</strong> two is <strong>the</strong> episcleral space (Tenon’sspace), which can be readily injected (Fig. 3–8).On its outer aspect <strong>the</strong> capsule is intimately relatedto <strong>the</strong> orbital reticular tissue. Its posterior edge isFIGURE 3–7. Course <strong>of</strong> inferior oblique muscle and <strong>the</strong>relationships <strong>of</strong> its tendon. Measurements are in millimeters.(Modified from Fink WH: Surgery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vertical<strong>Muscles</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eyes, ed 2. Springfield, IL, Charles CThomas, 1962.)

<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong> <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> 45FIGURE 3–8. Tenon’s space shown by injection with Indiaink. (Modified from Charpy A: <strong>Muscles</strong> et capsulede Tenon. In Poirier P, Charpy A, eds: Traité d’anatomiehumaine, new ed, vol 5/2. Paris, Masson, 1912, p 539.)not clearly delineated; it is thin and more or lesscontinuous with <strong>the</strong> meshwork <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbital fat.If <strong>the</strong> globe is enucleated, one can see <strong>the</strong>anterior orifice <strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule, <strong>the</strong> borders <strong>of</strong>which were attached to <strong>the</strong> sclera before enucleation;<strong>the</strong> posterior orifice, which is fused with<strong>the</strong> sheaths <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> optic nerve; and <strong>the</strong> smoothinner surface with <strong>the</strong> slits <strong>of</strong> entry for <strong>the</strong> extraocularmuscles. The openings for <strong>the</strong> vortex veinsare small and not readily visualized (Fig. 3–9).Muscle Sheaths and TheirExtensionsThe extrinsic ocular muscles pierce Tenon’s capsule,enter <strong>the</strong> subcapsular space, and insert into<strong>the</strong> sclera. Therefore, one can distinguish an extracapsularand an intracapsular portion <strong>of</strong> eachmuscle.In <strong>the</strong>ir extracapsular portions, <strong>the</strong> extrinsic eyemuscles are enveloped by a muscle sheath. Thissheath is a reflection <strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule and runsbackward from <strong>the</strong> entrance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscles into<strong>the</strong> subcapsular space for a distance <strong>of</strong> 10 to 12mm. At <strong>the</strong> lower aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entrance, Tenon’scapsule is reduplicated. At <strong>the</strong> upper aspect, itcontinues forward as a single membrane (Fig.3–10). The muscle sheaths <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four rectus musclesare connected by a formation known as <strong>the</strong>intermuscular membrane, which closely relates<strong>the</strong>se muscles to each o<strong>the</strong>r (Fig. 3–11). In addition,<strong>the</strong>re are numerous extensions from all <strong>the</strong>sheaths <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocular muscles, which form anintricate system <strong>of</strong> fibrous attachments interconnecting<strong>the</strong> muscles, attaching <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>the</strong> orbit,supporting <strong>the</strong> globe, and checking <strong>the</strong> ocularmovements. These will now be described in <strong>the</strong>iressential features.The fascial sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior rectus muscleclosely adheres in its anterior external surface to<strong>the</strong> undersurface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> levator muscle<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> upper lid. In front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> equator <strong>the</strong>sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior rectus muscle also sends aseparate extension obliquely forward that widensand ends on <strong>the</strong> lower surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> levator muscle.The fusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two muscles accounts for<strong>the</strong> cooperation <strong>of</strong> upper lid and globe in elevation<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye, a fact that must be kept in mind whensurgical procedures on <strong>the</strong> superior rectus muscleare being considered.The fascial sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inferior rectus muscledivides anteriorly into two layers: an upper one,which becomes part <strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule, and aFIGURE 3–9. Anterior and posteriororifice <strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule shownafter enucleation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe. (Modifiedfrom Charpy A: <strong>Muscles</strong> et capsulede Tenon. In Poirier P, Charpy A,eds: Traité d’anatomie humaine, newed, vol 5/2. Paris, Masson, 1912, p539.)

46 Physiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sensorimotor Cooperation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> EyesFIGURE 3–10. Check ligaments <strong>of</strong> medialand lateral rectus muscles. Reduplication <strong>of</strong>Tenon’s capsule, forming <strong>the</strong> muscle sheath<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles.lower one, which is about 12 mm long and endsin <strong>the</strong> fibrous tissue between <strong>the</strong> tarsus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>lower lid and <strong>the</strong> orbicularis muscle (Figs. 3–11and 3–12). This lower portion forms part <strong>of</strong> Lockwood’sligament.The fascial sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reflected tendon <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> superior oblique muscle consists <strong>of</strong> two layers<strong>of</strong> strong connective tissue (Fig. 3–13). The twolayers are 2 to 3 mm thick, so <strong>the</strong> tendon and itssheath have a diameter <strong>of</strong> about 5 to 6 mm. Thepotential space between <strong>the</strong> sheath and <strong>the</strong> tendonis continuous with <strong>the</strong> episcleral space. Materialinjected into Tenon’s space <strong>the</strong>refore may penetrateinto <strong>the</strong> space between tendon and sheath. 2Many attachments extend from <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>superior oblique muscle to o<strong>the</strong>r areas: to <strong>the</strong>sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> levator muscle, to <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>superior rectus muscle, to <strong>the</strong> conjoined sheath <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se two muscles, and to Tenon’s capsule, behind,above, and laterally. The numerous fine fibrils thatconnect <strong>the</strong> inner surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sheath to <strong>the</strong>tendon are an important feature (see Fig. 3–13).19, 29Some authors have rejected <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>superior oblique tendon having a separate sheathand favor <strong>the</strong> view that what appears to be sheathare actually reflections <strong>of</strong> anterior and posteriorTenon’s capsule. This concept is <strong>of</strong> interest inconnection with <strong>the</strong> etiology <strong>of</strong> Brown syndrome.The fascial sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inferior oblique musclecovers <strong>the</strong> entire muscle. It is ra<strong>the</strong>r thin at <strong>the</strong>FIGURE 3–11. Intermuscular membranes and fascialextensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior, lateral, and inferiorrectus muscles (right eye).

<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong> <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> 47Ligament <strong>of</strong> LockwoodThe blending <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sheaths <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inferior obliqueand inferior rectus muscles and <strong>the</strong> extensions thatgo from <strong>the</strong>re upward on each side to <strong>the</strong> sheaths<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> medial and lateral rectus muscles form asuspending hammock, which supports <strong>the</strong> eyeball.This part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fascial system has been termed<strong>the</strong> suspensory ligament <strong>of</strong> Lockwood. Extensions<strong>of</strong> fibrous bands to <strong>the</strong> tarsal plate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lowerlid, <strong>the</strong> orbital septum, and <strong>the</strong> periosteum <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>floor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit also form part <strong>of</strong> Lockwood’sligament (see Fig. 3–12).FIGURE 3–12. Fascial sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inferior rectus muscleand Lockwood’s ligament.origin but thickens as <strong>the</strong> muscle continues laterallyand develops into a ra<strong>the</strong>r dense membranewhere it passes under <strong>the</strong> inferior rectus muscle.At this point, <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inferior obliquemuscle fuses with <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inferior rectusmuscle (see Fig. 3–12). This fusion may be quitefirm and complete or so loose that <strong>the</strong> two musclesmay be relatively independent <strong>of</strong> each o<strong>the</strong>r. Near<strong>the</strong> insertion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inferioroblique muscle also sends extensions to <strong>the</strong>sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lateral rectus muscle and to <strong>the</strong>sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> optic nerve.FIGURE 3–13. Fascial sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reflected tendon <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> superior oblique muscle. (Modified from Berke RN:Tenotomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior oblique for hypertropia [preliminaryreport]. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 44:304, 1946.)Check LigamentsThe medial and lateral rectus muscles possesswell-developed fibrous membranes that extendfrom <strong>the</strong> outer aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscles to <strong>the</strong> correspondingorbital wall.The check ligament <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lateral rectus muscleappears in horizontal sections as a triangle, <strong>the</strong>apex <strong>of</strong> which is at <strong>the</strong> point where <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> muscle pierces Tenon’s capsule. From <strong>the</strong>re itgoes forward and slightly laterally, fanning out toattach to <strong>the</strong> zygomatic tubercle, <strong>the</strong> posterioraspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lateral palpebral ligament, and <strong>the</strong>lateral conjunctival fornix (see Fig. 3–10).The check ligament <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> medial rectus muscleextends from <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle, attachingto <strong>the</strong> lacrimal bone behind <strong>the</strong> posterior lacrimalcrest and to <strong>the</strong> orbital septum behind. It is triangularand unites at its superior border with astrong extension from <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> levatormuscle and a weaker extension from <strong>the</strong> sheath <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> superior rectus muscle. The inferior border isfused to extensions from <strong>the</strong> inferior oblique andinferior rectus muscle sheaths.The o<strong>the</strong>r extraocular muscles do not haveclearly distinct check ligaments such as those <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> medial and lateral rectus muscles. However,<strong>the</strong> various extensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle sheaths to<strong>the</strong> sheaths <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r muscles, <strong>the</strong> orbital wall, andTenon’s capsule undoubtedly fulfill <strong>the</strong> task <strong>of</strong>checking <strong>the</strong> action <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se muscles. Actually, ithas been said (with considerable truth) by Duke-Elder, 12, p. 451 who quotes Dwight, 13 that <strong>the</strong> complexities<strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule are limited only by<strong>the</strong> perverted ingenuity <strong>of</strong> those who describe it.Intracapsular Portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MuscleThe muscles move freely through <strong>the</strong> openings inTenon’s capsule. In <strong>the</strong> intracapsular portion,

48 Physiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sensorimotor Cooperation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eyesremains fairly constant in relation to <strong>the</strong> orbitalpyramid (see <strong>Chapter</strong> 4). Also, owing particularlyto <strong>the</strong> action <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> check ligaments, <strong>the</strong> eye movementsbecome smooth and dampened. As <strong>the</strong> musclescontract, <strong>the</strong>ir action is graduated by <strong>the</strong> elasticity<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir check systems, which limits <strong>the</strong>action <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contracting muscle and reduces <strong>the</strong>effect <strong>of</strong> relaxation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> opposing muscles (seeSherrington’s law, <strong>Chapter</strong> 4, p. 63). This ensuressmooth rotations and lessens <strong>the</strong> shaking up <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>contents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe when <strong>the</strong> eyes suddenly stopor change <strong>the</strong> direction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir movement.FIGURE 3–14. The falciform folds <strong>of</strong> Guérin, one on eachside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles. (Modified from Guérin G:Mémoire sur la myotomie oculaire par la méthode sousconjonctivale.Gazette Med Paris, 1842.)which for <strong>the</strong> rectus muscles is 7 to 10 mm inlength, <strong>the</strong>y have no sheath but are covered byepiscleral tissue fused with <strong>the</strong> perimysium. Thistissue expands laterally, going along <strong>the</strong> muscleon each side, from <strong>the</strong> entry <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle into<strong>the</strong> subcapsular space to <strong>the</strong> insertion. Posteriorly,this tissue attaches to <strong>the</strong> capsule and laterally to<strong>the</strong> sclera. At <strong>the</strong> tendon this tissue becomes ra<strong>the</strong>rdense and appears to serve to fixate <strong>the</strong> tendon,forming <strong>the</strong> falciform folds <strong>of</strong> Guérin 17 or adminicula<strong>of</strong> Merkel 25, 26 (Fig. 3–14). Merkel and Kalliusremarked that <strong>the</strong>se structures make it difficultto determine accurately <strong>the</strong> width <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertions.Functional Role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> FascialSystemAside from its role in connecting <strong>the</strong> globe with<strong>the</strong> orbit and <strong>of</strong> supporting and protecting it, <strong>the</strong>main task <strong>of</strong> Tenon’s capsule is to serve as a cavitywithin which <strong>the</strong> eyeball may move. Helmholtz 18compared <strong>the</strong> movements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyeball in Tenon’scapsule to <strong>the</strong> movements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> head <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> femurin <strong>the</strong> cotyloid fossa. However, Tenon’s capsuledoes not have <strong>the</strong> anatomical characteristics <strong>of</strong>synovial tissue, nor is it a serous membrane.The complicated system <strong>of</strong> fasciae and ligamentsis <strong>of</strong> considerable importance in <strong>the</strong> control<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye movements. It prevents or reduces retractions<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe, as well as movements in<strong>the</strong> direction <strong>of</strong> action <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle pull. Thus,<strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> rotation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyeballDevelopmental Anomalies <strong>of</strong><strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> and <strong>the</strong>Fascial System<strong>Gross</strong> developmental anomalies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocularmuscles are infrequent. The cases recorded in <strong>the</strong>literature are grouped toge<strong>the</strong>r and reported withgreat completeness by Duke-Elder 12, p. 979 Many <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se reports are fascinating, but it would serveno useful purpose to discuss <strong>the</strong>m in this book.Unless <strong>the</strong> anomaly is extreme, such as <strong>the</strong> totalabsence <strong>of</strong> a muscle, it is not likely to have amajor effect on <strong>the</strong> coordination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye movementsor on <strong>the</strong> relative position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes, sinceeven <strong>the</strong> experimental transposition <strong>of</strong> various extraocularmuscles does not permanently destroythis coordination.Patients with congenital absence <strong>of</strong> a musclepresent with <strong>the</strong> clinical picture <strong>of</strong> complete paralysis(see <strong>Chapter</strong> 20). There may be no preoperativeclues to alert <strong>the</strong> surgeon that <strong>the</strong> apparentlyparalyzed muscle is absent. Consequently, <strong>the</strong> surgeonmust be prepared to use alternative surgicalapproaches if a muscle cannot be located at <strong>the</strong>time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> operation.Anomalies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fascial system are more commonthan those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscles, and it is probablethat <strong>the</strong>y have functionally, and <strong>the</strong>refore clinically,a more pr<strong>of</strong>ound effect on <strong>the</strong> ocular motility.These anomalies act as a check to activeand passive movements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> globe in certaindirections, although <strong>the</strong> muscles that should produce<strong>the</strong> active movement may be quite normalanatomically and functionally. To this group belonga number <strong>of</strong> clinical entities, such as <strong>the</strong>various forms <strong>of</strong> strabismus fixus and <strong>the</strong> superioroblique tendon sheath syndrome <strong>of</strong> Brown, 4 whichare discussed in <strong>Chapter</strong> 21.

<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong> <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> 49Innervation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong><strong>Muscles</strong>The medial, superior, and inferior rectus musclesand <strong>the</strong> inferior oblique muscle are all innervatedby cranial nerve III, <strong>the</strong> oculomotor nerve. Thebranches enter <strong>the</strong>ir respective muscles from <strong>the</strong>bulbar side. The branches intended for <strong>the</strong> medialrectus muscle enter its belly 15 mm from <strong>the</strong>origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle; those for <strong>the</strong> inferior rectusmuscle enter at <strong>the</strong> junction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> posterior andmiddle third <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> belly; and those for <strong>the</strong> inferioroblique muscle enter just after <strong>the</strong> muscle passeslateral to <strong>the</strong> inferior rectus muscle. All <strong>the</strong>sebranches are innervated by <strong>the</strong> inferior division <strong>of</strong>cranial nerve III.The branches for <strong>the</strong> superior rectus muscleoriginate from <strong>the</strong> upper division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oculomotornerve and enter <strong>the</strong> muscle at <strong>the</strong> junction <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> posterior and middle thirds (Fig. 3–15). Thelateral rectus muscle is innervated by cranial nerveVI, <strong>the</strong> abducens nerve, which enters <strong>the</strong> muscle15 mm from its origin on <strong>the</strong> bulbar side (seeFig. 3–15).The superior oblique muscle differs from <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r five extraocular muscles in that cranial nerveIV, <strong>the</strong> trochlear nerve, which innervates it, enters<strong>the</strong> muscle from <strong>the</strong> outer (orbital) surface near<strong>the</strong> lateral border after crossing over from <strong>the</strong>medial side. The nerve divides into three or fourbranches. The most anterior branch enters <strong>the</strong>belly at <strong>the</strong> juncture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> posterior and middlethird <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscle and <strong>the</strong> most posterior at about8 mm from its origin (see Fig. 3–15).Sensory organs have been described in <strong>the</strong> extraocularmuscles. They presumably provide amore or less defined stretch effect. Although <strong>the</strong>innervation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se organs has not been followedin humans, it is likely to take <strong>the</strong> route <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ophthalmic division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> trigeminal nerve.Blood Supply <strong>of</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong><strong>Muscles</strong>All extraocular muscles are supplied by <strong>the</strong> lateraland medial muscular branches <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ophthalmicartery. The lateral branch supplies <strong>the</strong> lateral andsuperior rectus muscles, <strong>the</strong> levator muscle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>upper lid, and <strong>the</strong> superior oblique muscle. Themedial branch, <strong>the</strong> larger <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two, supplies <strong>the</strong>inferior and medial rectus muscles and <strong>the</strong> inferioroblique muscle. The inferior rectus muscle and<strong>the</strong> inferior oblique muscle also receive a branchFIGURE 3–15. Innervation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocular muscles. N, cranial nerve.

50 Physiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sensorimotor Cooperation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> EyesFIGURE 3–16. The anterior ciliary arteries. (From LastRJ: Wolff’s <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eye and Orbit, ed 6. Philadelphia,HK Lewis, 1968.)from <strong>the</strong> infraorbital artery, and <strong>the</strong> medial rectusmuscle receives a branch from <strong>the</strong> lacrimal artery.The arteries to <strong>the</strong> four rectus muscles give riseto <strong>the</strong> anterior ciliary arteries. Two arteries emergefrom each tendon, except for <strong>the</strong> lateral rectusmuscle, which has only one. There are exceptionsto this rule, however, as any muscle surgeon canreadily confirm. Variations in <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> anteriorciliary arteries supplied by each muscle becomeclinically relevant with regard to <strong>the</strong> anteriorsegment blood supply when disinserting more thantwo rectus muscle tendons during muscle surgery(see <strong>Chapter</strong> 26).The anterior ciliary arteries pass to <strong>the</strong> episclera,give branches to <strong>the</strong> sclera, limbus, andconjunctiva, and pierce <strong>the</strong> sclera not far from <strong>the</strong>corneoscleral limbus (Fig. 3–16). These perforatingbranches cross <strong>the</strong> suprachoroidal space toterminate in <strong>the</strong> anterior part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ciliary body.Here <strong>the</strong>y anastomose with <strong>the</strong> lateral and mediallong ciliary arteries to form <strong>the</strong> major arterialcircle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> iris.The veins from <strong>the</strong> extraocular muscles correspondto <strong>the</strong> arteries and empty into <strong>the</strong> superiorand inferior orbital veins, respectively.REFERENCES1. Apt L: An anatomical evaluation <strong>of</strong> rectus muscle insertions.Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 78:365, 1980.2. Berke RN: Tenotomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior oblique for hypertropia(preliminary report). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc44:304, 1946.3. Bron AJ, Tripathi RC: Wolffe’s <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eye andOrbit, ed 8. London, Chapman & Hall, 1997.4. Brown HW: Congenital structural muscle anomalies. InAllen, JH, ed: Strabismus Ophthalmic Symposium I. StLouis, Mosby–Year Book, 1950, p 205.5. Charpy A: <strong>Muscles</strong> et capsule de Tenon. In Poirier P,Charpy A, eds: Traité d’anatomie humaine, new ed vol5/2. Paris, Masson, 1912, p 539.6. Clark RA, Miller JM, Demer JL.: Location and stability<strong>of</strong> rectus muscle pulleys. Muscle paths as function <strong>of</strong> gaze.Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38:227, 1997.7. Clark RA, Rosenbaum AL, Demer JL: Magnetic resonanceimaging after surgical transposition defines <strong>the</strong> anteroposteriorlocation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rectus muscle pulleys. J AAPOS3:9, 1999.8. Demer JL, Miller JM, Poukens V: Surgical implications <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> rectus extraocular muscle pulleys. Pediatr OphthalmolStrabismus 33:208, 1996.9. Demer JL, Oh SY, Poukens V: Evidence for active control<strong>of</strong> rectus extraocular muscle pulleys. Invest Ophthal VisSci 41:1280, 2000.10. Demer JL, Miller JM, Poukens V, et al: Evidence forfibromusclar pulleys <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> recti extraocular muscles. InvestOphthalmol Vis Sci 36:1125, 1995.11. Demer JL, Pukens V, Miller JM, Mircevych P: Innervation<strong>of</strong> extraocular pulley smooth muscle in monkeys and humans.Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38:1774, 1997.12. Duke-Elder S, Wybar KC: The <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> VisualSystem. System <strong>of</strong> Ophthalmology, vol 2. St Louis,Mosby–Year Book, 1961.13. Dwight T: The anatomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orbit and <strong>the</strong> appendages<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye. In Norris WF, Oliver CA, eds: System <strong>of</strong>Diseases <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eye, vol 1. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott,1897, p 99.14. Fink WH: Surgery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vertical <strong>Muscles</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eyes, ed2. Springfield, IL, Charles C Thomas, 1962.15. Fuchs E: Beiträge zur normalen Anatomie des Augapfels.Graefes Arch Ophthalmol 30(4):1, 1894.16. Gat L: Einige Beiträge zur Topographie des Ansatzes dervier geraden Augenmuskeln. Ophthalmologica 14:43,1947.17. Guérin G: Mémoire sur la myotomie oculaire par la méthodesous-conjonctivale. Gazette Med Paris, 1842.18. Helmholtz H von: In Southall PC, ed: Helmholtz’s Treatiseon Physiological Optics. English translation from <strong>the</strong> 3rdGerman edition, Ithaca, NY, Optical Society <strong>of</strong> America,1924. Quoted from reprint, New York, Dover Publications,vol 3, 1962, p 38.19. Helveston EM: Brown syndrome: Anatomic considerationsand pathophysiology. Am Orthoptics J 43:31, 1993.20. Helveston EM: The influence <strong>of</strong> superior oblique anatomyon function and treatment. Binocular Vision StrabismusQ:14:16, 1999.21. Helveston EM, Merriam WW, Ellis FD, et al: The trochlea:A study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> anatomy and physiology. Ophthalmology89:124, 1982.22. Howe L: Insertion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ocular muscles. Trans Am OphthalmolSoc 9:668, 1902.23. Lang J, Horn T, Eichen U von den: Über die äusserenAugenmuskeln und ihre Ansatzzonen. Gegenbaurs MorpholJahrb 126:817, 1980.24. Last RJ: Wolff’s <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eye and Orbit, ed 6.Philadelphia, HK Lewis & Co, 1968.25. Merkel F: Makroscopische Anatomie. In Graefe A, SaemischTh, eds: Handbuch der gesammten Augenheilkunde,ed 1, vol 1. Leipzig, Wilhelm Engelmann, 1874, p 56.[See also Merkel and Kallius. 27,p73 ]26. Merkel F, Kallius E: Makroscopische Anatomie desAuges. In Graefe A, Saemisch Th, eds: Handbuch dergesammten Augenheilkunde, ed 2, vol 1. Leipzig, WilhelmEngelmann, 1910, p 65 n.27. Miller JM: Functional anatomy <strong>of</strong> human rectus muscles.Vision Res 29:223, 1989.28. Motais E: L’appareil moteur de l’oeuil de l’homme etdes vertébrés. Déductions physiologiques et chirurgicales(strabisme). Paris, A. Delahaye & E. Lecrosnier, 1887.

<strong>Summary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gross</strong> <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Extraocular</strong> <strong>Muscles</strong> 5129. Parks MM: The superior oblique tendon—33rd DoyneMemorial Lecture. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 97:288,1977.30. Porter JD, Pukens V, Baker RS, et al: Structure functioncorrelations in <strong>the</strong> human medial rectus extraocular musclepulleys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37:468, 1996.31. Powell T: Elementa opticae. London, F. Griswold, 1651 p18. [About this exceedingly rare book and its author, seeBurian HM: A text for <strong>the</strong> times <strong>of</strong> Cromwell. DartmouthColl Libr Bull 4:19, 1943.]32. Scobee RC: Anatomic factors in <strong>the</strong> etiology <strong>of</strong> strabismus.Am J Ophthalmol 31:781, 1948.33. Sevel P: The origins and insertions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocularmuscles: Development, histologic features, and clinicalsignificance. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 84:488, 1986.34. Simonsz HJ, Harting F, de Waal BJ, et al: Sidewaysdisplacement and curved path <strong>of</strong> recti eye muscles. ArchOphthalmol 103:124, 1985.35. Souza-Dias C, Prieto-Diaz J, Uesugui CF: Topographicalaspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> insertions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extraocular muscles. JPediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 23:183, 1986.36. Stangl R, Mühlendyck H, Kraus-Mackiw E: Muskelansatz-Limbusdistanz und Sehnenlänge der Musculi recti in Abhängigheitvon der Bulbusgrösse bzw. vom Altern. InKommerell G, ed: Augenbewegungsstörungen: Neurophysiologieund Klinik. JF Bergmann, Munich, 1978, p 33.37. Thiel HL: Zur topographischen und histologischen Situationder Ora serrata. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol156:590, 1955.38. Whitnall SE: The <strong>Anatomy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Human Orbit and AccessoryOrgans <strong>of</strong> Vision, ed 2. New York, HumphreyMilford, 1932.39. Zoth O: Augenbewegungen und Gesichtswahrnehmungen.In Nagel W, ed: Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen,vol 3. Braunschweig, Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn, 1905,p 296.