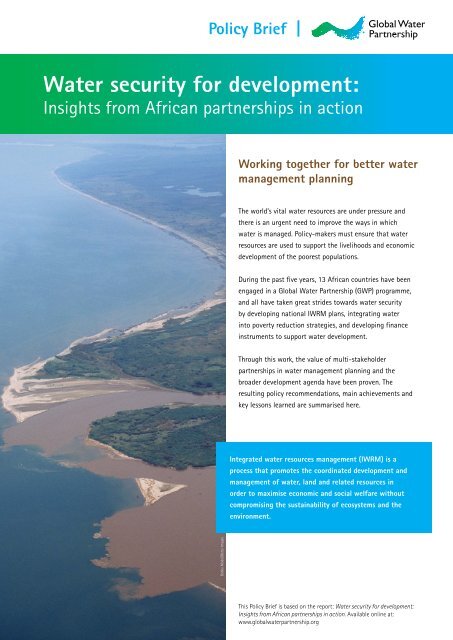

Policy Brief - Global Water Partnership

Policy Brief - Global Water Partnership

Policy Brief - Global Water Partnership

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2 | <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Brief</strong>The Programme for IWRMPlanning in AfricaThis involved 13 countries in four regions: CentralAfrica (Cameroon), East Africa (Burundi, Eritrea,Ethiopia and Kenya), Southern Africa (Malawi,Mozambique, Swaziland and Zambia) and West Africa(Benin, Cape Verde, Mali and Senegal).Its goal was to contribute to sustainable developmentand poverty reduction through using an IWRMapproach and offering support in four main areas:• Achievement of the target set at the 2002 WorldSummit on Sustainable Development for thepreparation of national IWRM plans• Development of existing, new and emergingpartnerships• Integration of water into poverty reductionstrategies• Increasing understanding of, and potential accessto, a broader range of financing instruments.A summary of the mainachievements<strong>Policy</strong> RecommendationsIntegrated approaches to water managementand other development interventions should:1. Be undertaken as part of the broadernational development planning process.Cross-sectoral coordination andresponsibility for integration should beanchored in a government institutionwith capacity to influence and mobiliseother sectors. Higher-level governmentbodies such as ministries of finance andeconomic planning, the cabinet andthe prime minister’s or vice president’soffice are good locations for facilitatingintegration.2. Be aligned with high-priority nationaldevelopment processes with broad crosssectoraland stakeholder support, even ifthese are outside the water sector.3. Be flexible, realistic and structured as acontinuous process rather than individualprojects.The IWRM planning programme helped provide a voicefor a wide range of stakeholders to define actionsfor improving water management for development.Each participating country now has a considerablyenhanced enabling environment for water security.National IWRM plans have been finalised and adoptedby governments in seven countries and, at the timeof writing, a further five plans are in the process ofapproval or at advanced stage. Evidence suggests thatimplementation of IWRM plans in some of the countriesis already underway.CAPEVERDESENEGALMALIBENINERITREAETHIOPIACAMEROONIWRM has been integrated into national developmentplans and poverty reduction strategies in Benin,Malawi, Mali and Zambia; while Benin, Eritrea,Swaziland and Zambia have drafted and updated theirwater policies. In addition, Benin has drafted improvedwater legislation, Cape Verde has developed a new legalframework for the administration of water resources,and Eritrea has introduced water quality guidelines andwater-use regulations.BURUNDIZAMBIAMOZAMBIQUESWAZILANDKENYAMALAWI

<strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Brief</strong> | 34. Take into account country differencesand accommodate variations of scopeand budget, based on the country’sdevelopment context.5. Embed water-related climate changeadaptation into water resourcesmanagement plans and not treat itas a separate issue, in order to avoidduplication and fragmentation. Thecapacity of local institutions must be builtto address climate change adaptationas part of the water security agenda indevelopment planning and decisionmakingprocesses, in line with nationaldevelopment priorities.6. Develop economic arguments forfinancing water resources management.Opportunities for accessing adaptationfunds for financing water resourcesmanagement must be explored.Most countries have defined improved institutionalroles and coordination arrangements; they have alsoenhanced water management capacity leading to betterunderstanding of the water resource situation andconstraints to national development.<strong>Water</strong> financing has been improved, with financial resourcesmobilised from local and international sources. For example,Benin has secured €1.6 million from the Netherlandsand nearly €20 million was pledged (by various donors)for Mali’s IWRM plan. National water sector fundingwas increased by an estimated 64 percent by Malawi’streasury in the 2005/06 financial year. The World Bank’sJoint Assistance Strategy for water in Zambia has beendeveloped to provide support to the implementation of theprogrammes in the IWRM plan. The Zambian Governmentis using the IWRM plan as a basis for preparation anddisbursements of annual budgets for water programmes.“While it is significant that so manynational plans were developed andimmediate impacts realised, the realachievement of the IWRM programmelies in the way in which this happened.”Ian Cumming/Axiom/Getty ImagesFranck Guiziou/Getty ImagesThe programme also contributed to improvements inpeople’s livelihoods by enhancing water security at a locallevel. <strong>Water</strong> was secured for the 200,000 inhabitants ofBenin’s third largest city and, in Swaziland, 9,600 peoplegained access to clean water. Furthermore, water-relatedconflicts have been addressed and access to waterenhanced in Ethiopia’s Berki River Basin.While it is significant that so many national plans weredeveloped and immediate impacts realised, the realachievement of the IWRM programme lies in the way inwhich this happened. Local participants engaged deeplywith the planning process, while external consultancydrivenpressures were minimised. Very different approacheswere taken to drafting the plans in different countriesbecause an attempt was made to integrate watermanagement planning with other development activities.Hence, the approach in each country reflected its broaderinstitutional environment and had stronger nationalownership than previous, externally driven plans.

4 | <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Brief</strong>Learning from watermanagement planning:Lessons for developmentBrendan Ryan/Getty ImagesThe IWRM programme offers considerable insights into thefactors that helped the planning processes succeed. Theseinsights drawn from the water sector are equally applicableto development processes in other sectors. Nine elements(grouped into four clusters) were identified as essential:1. Development context• Entry point: a suitable entry point within the existingnational development context adds value and minimisesduplication.• Champions: committed and respected individuals candrive the process forward and speed up bureaucracy.2. Strategic road map• Integration with development priorities: all interventionsshould address national priorities and align withgovernment frameworks.• Institutional arrangements for coordination andfinancing: management processes should build onexisting institutional arrangements.• Roles and responsibilities: key players’ roles andresponsibilities should be agreed at the outset.3. Ensuring sustainability• Institutional memory: specific steps are needed to avoidthe loss of institutional memory over time as key peoplemove on.• Stakeholder platforms: an inclusive and neutralstakeholder platform facilitates dialogue on contentiousissues.4. Strengthening functions• Capacity development and knowledge management:developing the capacity of all stakeholders, especiallygovernment institutions, helps strengthen interventionsand enhances sustainability.• Communication and advocacy: the goals, progress,challenges and achievements need to be continuouslycommunicated to stakeholders.Despite the remarkable progress made towards the goalof water security, there is considerable work still to do.These policy recommendations and lessons, if applied,will help support future efforts for better water resourcesmanagement planning as well as broader developmentinterventions. GWP would like to use the IWRM programmeexperience to advance the agenda on water security bysupporting national governments to incorporate climatechange adaptation into development processes.Produced by Green Ink Ltd (www.greenink.co.uk)The <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Partnership</strong> is an intergovernmental organisation with a worldwide network of 13 Regional <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Partnership</strong>s, 74 Country<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Partnership</strong>s and more than 2,000 Partner organisations in 153 countries. The GWP network is committed to building a water secure worldand is supported financially by Canada, Denmark, the European Commission, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Spain,Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. For the work described here, additional support was provided by the Netherlands Directorate-General of Development Cooperation (DGIS) and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) under the <strong>Partnership</strong> for Africa’s <strong>Water</strong>Development programme. GWP is grateful to its many stakeholders, Partners and Country and Regional <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Partnership</strong>s who contributed to theoutcomes and knowledge generated by this multi-year process of IWRM planning and implementation.<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Partnership</strong><strong>Global</strong> SecretariatDrottninggatan 33, SE-111 51 Stockholm, Swedenwww.globalwaterpartnership.org, www.gwptoolbox.orgMarch 2010