Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: What's in a Name? - Thblack.com

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: What's in a Name? - Thblack.com

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: What's in a Name? - Thblack.com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>, Vol 12, No 1 (January), 2011: pp 2-12Available onl<strong>in</strong>e at www.sciencedirect.<strong>com</strong>Focus Article<strong>Complex</strong> <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>Syndrome</strong>: What’s <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Name</strong>?Terence J. CoderreDepartment of Anesthesia and Alan Edward Centre for Research on <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>, McGill University, and McGill UniversityHealth Centre Research Institute, Montreal, Quebec.Abstract: With<strong>in</strong> a 2-year period <strong>in</strong> the 1940s, 2 Boston physicians published dramatically oppos<strong>in</strong>gviews on the underly<strong>in</strong>g nature of a syndrome now known as <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome(CRPS). Evans suggested, <strong>in</strong> several papers <strong>in</strong> 1946–1947, that sympathetic reflexes ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> pa<strong>in</strong>and dystrophy <strong>in</strong> affected limbs. Foisie, <strong>in</strong> 1947, suggested arterial vasospasms were key <strong>in</strong> the etiologyof this pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome. Evans’ hypothesis established the nomenclature for this syndrome for 60years, and his term, ‘‘reflex sympathetic dystrophy,’’ guided cl<strong>in</strong>ical treatment and research activitiesover the same period. Foisie’s proposed nomenclature was unrecognized, and had virtually no impacton the field. Recent evidence suggests that Evans’ contribution to the field may have <strong>in</strong> fact ledcl<strong>in</strong>icians and researchers astray all those years. This focus article on CRPS <strong>com</strong>pares recent observationswith these 2 earlier theories and asks the question—what if we had adopted Foisie’s nomenclaturefrom the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g?Perspective: This article discusses 2 oppos<strong>in</strong>g historical views on the etiology of what is nowknown as CRPS, and how they affected nomenclature, research, and cl<strong>in</strong>ical therapy <strong>in</strong> subsequentdecades. This focus article may help researchers and cl<strong>in</strong>icians realize the importance of syndromenames, and how they may <strong>in</strong>advertently misdirect research and treatment.ª 2011 by the American <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> SocietyKey words: <strong>Complex</strong> regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome, CRPS, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, arterial vasospasm,nomenclature, etiology, pathophysiology, ischemia.<strong>Complex</strong> regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome (CRPS; see Table 1for characteristics and diagnostic criteria) 35,61 isthe current name for a syndrome that has beenknown over the years by many names, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gcauslagia, m<strong>in</strong>or causalgia, algodystrophy, shoulderhandsyndrome, and Sudeck’s atrophy. However, themost <strong>com</strong>mon and recently used name for CRPS was reflexsympathetic dystrophy. 83,86 Although mechanisticdifferences may not exist, the term CRPS-I has beenused to replace reflex sympathetic dystrophy and CRPS-II to replace causalgia, with the former diagnosis <strong>in</strong> caseswhere no nerve <strong>in</strong>jury is detected, and the latter whennerve <strong>in</strong>jury is confirmed. 61 Recent discouragementwith the sympathetic nervous system as a therapeutic target,13,25,53 and an underly<strong>in</strong>g pathology, 3,66,84,90 had noSupported by grants from CIHR, NSERC, and the Louise and Alan EdwardsFoundation.Address repr<strong>in</strong>t requests to Dr Terence J. Coderre, Anesthesia ResearchUnit, 1203-3655 Promenade Sir William Osler, Montreal, QC, H3G 1Y6,Canada. E-mail: terence.coderre@mcgill.ca1526-5900/$36.00ª 2011 by the American <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Societydoi:10.1016/j.jpa<strong>in</strong>.2010.06.001doubt encouraged the taxonomic change to CRPS, 83,86and it has been argued that the former syndromename may have misguided research and treatments<strong>in</strong>ce its <strong>in</strong>ception. 8 In a treatise on the concept that <strong>in</strong>spiredWilliam Shakespeare to pen the phrase ‘‘Thatwhich we call a rose by any other name would smell assweet,’’ the question should be asked—‘‘What’s <strong>in</strong>a (syndrome) name?’’ (Romeo and Juliet 2.2,43-44). 81That is, would history have been different if anothername than reflex sympathetic dystrophy had been adoptedfor the predom<strong>in</strong>ant nomenclature of CRPS? Toaddress this question, it would be <strong>in</strong>structive to reviewthe th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g of the time, back <strong>in</strong> the mid-1940s, whenthe term reflex sympathetic dystrophy (and an alternativename) was co<strong>in</strong>ed.In 1946–47, James A. Evans, a physician at the LaheyCl<strong>in</strong>ic <strong>in</strong> Burl<strong>in</strong>gton, Massachusetts, reported onpatients’ <strong>in</strong>tense suffer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>com</strong>b<strong>in</strong>ed with featurescharacteristic of what he called ‘‘stimulation of the sympathetic,. . . namely rubor, pallor, or a mixture of both,sweat<strong>in</strong>g and atrophy. . . .’’ 20 In a series of 4 papers thatdescribed at first 32, 19,20 then a total of 57 patients, 21,22he observed these symptoms <strong>in</strong> association with2

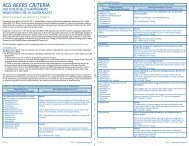

Coderre The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 3Table 1. International Association for the Studyof <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> (IASP) Diagnostic Criteria for CRPS-Iand CRPS-II 61CPRS-I(REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY)1. The presence of an <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>gnoxious event, or a cause ofimmobilization.2. Cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g pa<strong>in</strong>, allodynia, orhyperalgesia with which thepa<strong>in</strong> is disproportionate toany <strong>in</strong>cit<strong>in</strong>g event.3. Evidence at some time ofedema, changes <strong>in</strong> sk<strong>in</strong> bloodflow, or abnormal sudomotoractivity <strong>in</strong> the region of thepa<strong>in</strong>.4. This diagnosis is excluded bythe existence of conditionsthat would otherwiseaccount for the degree ofpa<strong>in</strong> and dysfunction.Note: Criteria 2 to 4 must besatisfied.CRPS-II (CAUSALGIA)1. The presence of cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>gpa<strong>in</strong>, allodynia, orhyperalgesia after a nerve<strong>in</strong>jury, not necessarily limitedto the distribution of the<strong>in</strong>jured nerve.2. Evidence at some time ofedema, changes <strong>in</strong> sk<strong>in</strong> bloodflow, or abnormal sudomotoractivity <strong>in</strong> the region of thepa<strong>in</strong>.3. This diagnosis is excluded bythe existence of conditionsthat would otherwiseaccount for the degree ofpa<strong>in</strong> and dysfunction.Note: All 3 criteria must besatisfied.fractures (21%), spra<strong>in</strong>s (21%), vascular <strong>com</strong>plications(19%), amputations (9%), jo<strong>in</strong>t/bone <strong>in</strong>flammation(5%), and lacerations (2%), or more m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong>juries/conditions <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g bruises (9%) and static defects ofthe foot (7%). <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> was described as deep, bor<strong>in</strong>g,diffuse, but with trigger po<strong>in</strong>ts, and manipulation oruse aggravated patient suffer<strong>in</strong>g. Importantly, Evansreported that often pa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> these patients was relievedby sympathetic blocks, as the limb warmed. Evansattributed the pa<strong>in</strong> to abnormality <strong>in</strong> the sympatheticnervous system, and first used the term reflexsympathetic dystrophy. 19-22 Evans suggested thatexcessive afferent nerve <strong>in</strong>puts associated with <strong>in</strong>jury<strong>in</strong>itiated central nervous system activity that spreadthrough an ‘‘<strong>in</strong>ternuncial pool’’ of hyperactive sp<strong>in</strong>alneurons that stimulated sympathetic neurons. Activitygenerated <strong>in</strong> postganglionic sympathetic efferents wasthen proposed to <strong>in</strong>duce arterial spasms and ischemiathat <strong>in</strong>creased capillary filtration pressure withresultant edema and swell<strong>in</strong>g. Evans’ conclusions wereclearly <strong>in</strong>fluenced by Lorento de No, 51 who discussedhow ‘‘prolonged bombardment of pa<strong>in</strong> impulses’’ triggers‘‘pools of constant circl<strong>in</strong>g of activity across (sp<strong>in</strong>al)synapses’’ and ‘‘a vicious circle’’ which causes sympatheticneurons to trigger vascular spasms that raise filtrationpressure caus<strong>in</strong>g oedema. He was also <strong>in</strong>spired by Liv<strong>in</strong>gston,50 who had applied Lorento de No’s above ideas andMacKenzie’s 52 theory of an ‘‘irritable focus’’ <strong>in</strong> sp<strong>in</strong>alcord (<strong>in</strong> relation to referred pa<strong>in</strong>) to the condition of causalgia,and who had adopted the techniques of Leriche 49by perform<strong>in</strong>g sympathectomies to break the viciouscircle.One year after Evans co<strong>in</strong>ed the term reflex sympatheticdystrophy, Philip S. Foisie, a surgeon at BostonCity Hospital, concluded that a persist<strong>in</strong>g low-grade arterialspasm after soft-tissue <strong>in</strong>jury can lead to a syndromewith severe pa<strong>in</strong>, extreme tenderness or allodynia, tissueswell<strong>in</strong>g, muscle atrophy, bone osteoporosis, jo<strong>in</strong>tstiffness, and limited motion. Basically, the constellationof symptoms that Evans would diagnose as reflexsympathetic dystrophy, Foisie termed ‘‘traumatic arterialvasospasm.’’ 23 Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Foisie, subacute, undetectedarterial vasospasms led to decreases <strong>in</strong> nutritional bloodsupply that resulted <strong>in</strong> degenerative changes primarily <strong>in</strong>the musculoskeletal system. Foisie was careful to po<strong>in</strong>tout that these vasospasms were not <strong>in</strong> large vesselsthat produce tissue-threaten<strong>in</strong>g ischemia, but rather <strong>in</strong>small arterioles. As causalities of war, some of the <strong>in</strong>juriesto Foisie’s patients were severe and may have <strong>in</strong>cludednerve as well as soft-tissue <strong>in</strong>jury, but others were less severeand the pa<strong>in</strong> was disproportionate to the <strong>in</strong>jury. Hedescribed these symptoms <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle paper on woundedsoldiers with fractures, soft-tissue <strong>in</strong>juries, m<strong>in</strong>or gunshotand shell-fragment wounds, but not <strong>in</strong> extensive‘‘wide-open’’ wounds. 23 Importantly, he observed thatthe syndrome was even more likely <strong>in</strong> patients with <strong>com</strong>pression<strong>in</strong>juries that resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased tissue tension(ie, where microvascular pressure is reduced because of<strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressure). He also notedthat swell<strong>in</strong>g was often present early on, particularly follow<strong>in</strong>gcast<strong>in</strong>g and immobilization, and concluded thatedema should be expected as ischemia causes microvascular<strong>in</strong>jury that <strong>in</strong>creases plasma extravasation with<strong>in</strong>creased permeability of capillary walls. Additionally,these patients would sometimes respond to a <strong>com</strong>b<strong>in</strong>ationof sympathetic blocks, massage, and physical therapyto encourage the restoration of nutritional bloodsupply back to deep tissues. Foisie described 2 cases <strong>in</strong>which pa<strong>in</strong> relief was obta<strong>in</strong>ed follow<strong>in</strong>g upper dorsal(sympathetic) ganglionectomy or lumbar (sympathetic)ganglionectomy. Foisie was probably <strong>in</strong>fluenced by thework of Leriche, 49 who had shown the sympathectomieswere useful <strong>in</strong> the treatment of posttraumatic contracturesand causalgia. He was likely also <strong>in</strong>fluenced byHomans 39 (also from Boston), who discussed the possibilitythat ‘‘gross arterial spasm’’ and ‘‘diffuse peripheralspasm’’ contributed to m<strong>in</strong>or causalgia.The most <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t to note is that althoughEvans and Foisie were both suggest<strong>in</strong>g that sympatheticblocks could be useful to relieve pa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> their patients,they came to different conclusions as to what pathologyproduced the pa<strong>in</strong>. Although, like Foisie, Evans identifiedarterial vasospasms and capillary permeability askey factors, it was their emphasis on sympathetic nervoussystem activity that differed dramatically. For Evans, <strong>in</strong>creasedactivity <strong>in</strong> sympathetic efferents was crucial tothe ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of the vicious circle, and sp<strong>in</strong>alhyperactivity ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed the reflex sympathetic drive.For Foisie, it was the nature of <strong>in</strong>jury itself that <strong>in</strong>itiatedthe vasospasm (particularly <strong>in</strong> cases where <strong>in</strong>juries <strong>in</strong>creased<strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressure), and sympathetic

4 The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Historical Reflection on <strong>Syndrome</strong> <strong>Name</strong>s for CRPSblocks were seen as a way to over<strong>com</strong>e the vasospasm.And as history has shown through the citation and keyword record searches (see Fig 1), Evans’ conclusionswere almost universally adopted, whereas Foisie’s werealmost <strong>com</strong>pletely ignored. Indeed, the volume of referencesto the term reflex sympathetic dystrophy clearlyshow that this name dom<strong>in</strong>ated medical th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gthroughout the latter half of the 20 th century. In fact,the emphasis of the sympathetic contribution to reflexsympathetic dystrophy has been a large driver <strong>in</strong> boththe predom<strong>in</strong>ant therapeutic practice and mechanisticresearch activity for the past 6 decades.403530252015105EvansFoisieIf Not Sympathetically Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>,Then What?Now that the pendulum has swung away from theview that sympathetic nervous system is causal for thepa<strong>in</strong> of CRPS, the question is whether it is about timeto seriously consider Foisie’s hypothesis. From the obviouslack of attention that Foisie’s theory received, couldit be said that while be<strong>in</strong>g preoccupied by the notions ofreflex sympathetic dystrophy and vicious circles, andlater by theories of sympathetically ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed pa<strong>in</strong>and sympathetically <strong>in</strong>dependent pa<strong>in</strong> (see below),Foisie’s hypothesis was the one that got away? What ifrather than reflex sympathetic dystrophy and sympatheticallyma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed pa<strong>in</strong>, traumatic arterial vasospasms,and ischemia-ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed pa<strong>in</strong> were the catch phrasesfor this syndrome? Would a diagnosis of traumatic arterialvasospasm have changed the way the patient wouldhave been treated, or would a syndrome so named havechanged the course of research history? Given the lack ofprogress <strong>in</strong> the field dur<strong>in</strong>g the reflex sympathetic dystrophyfixation, and recent research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs that supportFoisie’s conclusion, it is likely that the answer is yes!So what has been learned over the 60-odd years s<strong>in</strong>ceEvans’ and Foisie’s respectively renowned and ignoredhypotheses? First, it is be<strong>com</strong><strong>in</strong>g clear that sympatheticblocks do not always relieve pa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> CRPS patients. 13,25,53Clearly, some patients have remarkable but often shortlivedresponses to sympathetic blocks. Other patientsdo not respond at all, and still others respond, as notedby both Evans and Foisie, only follow<strong>in</strong>g multiple blocks.However, s<strong>in</strong>ce many of these trials lack control subjects,gradual improvement over time may reflect the naturalhistory of the syndrome, rather than the use of sympatheticnerve blocks. These f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs lead to 2 possible conclusions:1) that the pa<strong>in</strong> of CRPS depends on thesympathetic nervous system <strong>in</strong> some patients but notothers; or 2) that the sympathetic nervous system is notcritical to pa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> CRPS, but may <strong>in</strong>fluence pa<strong>in</strong> by affect<strong>in</strong>gother crucial factors. The first conclusion was adoptedby proponents of the once-popular notions ofsympathetically ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed 70 and sympathetically <strong>in</strong>dependent24 pa<strong>in</strong> (where the pa<strong>in</strong> is proposed to be dependenton, or <strong>in</strong>dependent of, activity <strong>in</strong> sympatheticefferent fibers, respectively), whereas the latter conclusionhas not, until recently, received much attention.012001000800600400200040's 50's 60's 70's 80's 90's 00'sReflex sympatheticdystrophyTraumatic arterialvasospasm50's 60's 70's 80's 90's 00'sFigure 1. Impact of Evans’ and Foisie’s papers on the field. (A)Histogram of the numbers of Science Citation Index citationsfound for the papers of Evans 19-22 and Foisie, 23 respectively bydecade between 1940 and 2009. (B) Histogram of the numbersof Medl<strong>in</strong>e citations found for the terms ‘‘reflex sympatheticdystrophy’’ and ‘‘traumatic arterial vasospasm’’ by decadebetween 1950 and 2009.A second important f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g is that numerous <strong>in</strong>vestigatorshave now reported that sympathetic activity isactually blunted, rather than enhanced, particularly <strong>in</strong>early-stage CRPS (when the limb is often hot andswollen). 45,77,95 This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs leads to the importantconclusion that CRPS cannot depend on enhancedactivity <strong>in</strong> sympathetic efferent fibers, at least not atstages dur<strong>in</strong>g which the activity is blunted. It alsosupports the theory that late-phase CRPS (when the limbis often cold and cyanotic) may depend on denervationhypersensitivity of sympathetic vasoconstrictors, 27,53,89a phenomenon that would be expected if sympatheticactivity is blunted for prolonged periods.Role of Ischemia-Reperfusion InjuryA third critical f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g is that many CRPS patients havesubtle but conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g evidence of persistent tissue ischemia<strong>in</strong> sk<strong>in</strong> and particularly deep tissue. Thus, muscle tissuefrom an amputated CRPS limb was found to exhibit

Coderre The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 5lipofusc<strong>in</strong> pigment, atrophic fibers, and severely thickenedbasal membrane layers of the capillaries. 90 Althoughamputated tissue may represent extreme casesof CRPS, this conclusion is also supported by functionalobservations of <strong>in</strong>creased density of perfused vessels,lower capillary filtration capacity, arteriovenous shunt<strong>in</strong>g,and ischemia of peripheral subcutaneous tissue <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>tact CRPS limbs. 57,78 It has also been reported thatCRPS limbs have high arterial flow, but low oxygenconsumption, as well as high lactate flux—<strong>in</strong>dicative oftissue ischemia, despite <strong>in</strong>creased flow <strong>in</strong> largevessels. 29 There is also an impairment of high-energyphosphate metabolism <strong>in</strong> muscle tissue of CRPS limbs, 30,37suggestive of mitochondrial oxygen deficiency. All ofthese observations suggest that ischemia <strong>in</strong> deep tissuescontributes to CRPS. Others have also found evidence ofmicrovascular <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong> sk<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g hypertrophicmultilayered, and sometimes collapsed, endothelial cellwalls around the arteries and arterials from the sk<strong>in</strong> ofamputated CRPS limbs, 3 and reduced sk<strong>in</strong> nutritive flowand capillary hemoglob<strong>in</strong> oxygenation <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tact CRPSlimbs. 44,45,71So it seems that Evans may have been wrong aboutsympathetic hyperactivity. However, if sympathetic hyperactivitydoes not cause the arterial vasospasms thatboth Foisie and Evans described, what does? Foisie provideda h<strong>in</strong>t about a possible mechanism. The h<strong>in</strong>t wasthat arterial vasospasms and pa<strong>in</strong>ful symptoms weremore likely (and more severe) after <strong>com</strong>pression <strong>in</strong>juriesthat <strong>in</strong>creased tissue tension (that is, lowered microvascularpressure because of <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmentalpressure). Foisie suggested that traumatic arterial vasospasmtakes place when <strong>in</strong>creased tissue tension occursafter <strong>in</strong>creased vascular permeability and accumulationof <strong>in</strong>terstitial fluid. He further suggested that arterialvasospasm caused a ‘‘prolonged arterial <strong>in</strong>adequately’’or an oxidative ‘‘malnutrition’’ which ‘‘. . . results <strong>in</strong>degenerative changes of the musculoskeletal systemprimarily.’’ 23Importantly, <strong>in</strong>juries that produce enough edema to<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressure can result <strong>in</strong> microvascularchanges and <strong>in</strong>jury that depend both onthe degree and length of time of the <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmentalpressure. M<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong>flammatory <strong>in</strong>juries causemicrovascular disturbances that <strong>in</strong>crease capillaryfiltration pressure and vascular permeability due to theformation of gaps <strong>in</strong> the endothelial cell l<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of microvessels.58 However, as <strong>in</strong>terstitial fluid <strong>in</strong>creases, there isa <strong>com</strong>pensatory <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> lymphatic flow, which prevents<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressure. 62 Moresignificant <strong>in</strong>flammation, after moderate soft tissue <strong>in</strong>juryor fracture, produces plasma extravasation ata rate that cannot be <strong>com</strong>pensated for by lymphaticflow, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressure.64,82 Intramuscular <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressuresthat approach diastolic blood pressure (typicallyaround 70 mmHg) for at least several hours producea phenomenon known as acute <strong>com</strong>partmentsyndrome (although prolonged <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmentalpressures above 40 to 45 mmHg are typically a warn<strong>in</strong>gthat an acute <strong>com</strong>partment syndrome may occur, and<strong>in</strong>dicate that aggressive treatment is warranted). 32,97Acute <strong>com</strong>partment syndrome results when thepressure from excessive <strong>in</strong>terstitial fluid with<strong>in</strong> a closedanatomical <strong>com</strong>partment <strong>com</strong>presses small bloodvessels and blocks oxygen supply to the tissue forseveral hours or more. 32The consequences of a very prolonged acute <strong>com</strong>partmentsyndrome can be catastrophic or even fatal, as theischemic muscle eventually degenerates, produc<strong>in</strong>g toxicmetabolites that lead to systemic <strong>in</strong>flammatory responsesyndrome and multiple organ dysfunction, characteristicof crush syndrome or tourniquet shock. 32,79 However,a critical study by Vollmar et al 92 has shown that <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmentalpressures much lower than those neededto produce acute <strong>com</strong>partment syndrome also have significanteffects on microvascular function. Thus, <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmentalpressures between 25 and 35 mmHgblock arterial flow <strong>in</strong> smaller arterioles and venules. Furthermore,an even lower <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressureof 12 mmHg produces a 50% reduction <strong>in</strong> the numberof perfused capillaries, reduc<strong>in</strong>g nutritive blood flow tothe <strong>in</strong>volved tissue. 92 Importantly, it was also foundthat subsequent reduction of <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressureby as little as 4 mmHg restores capillary flow. 92Therefore, for a significant number of capillaries, capillaryflow can be blocked (caus<strong>in</strong>g ischemia) and reestablished(caus<strong>in</strong>g reperfusion) with very small changes <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressures, at levels that are muchlower than required to cause acute <strong>com</strong>partment syndrome.If the ischemia associated with the capillaryblockade occurs for a few hours, the tissue with<strong>in</strong> thecapillary bed will be subjected to an ischemiareperfusion(IR) <strong>in</strong>jury, once the pressure is reduced andthe tissue is reperfused.Importantly, it has been shown that after closed softtissue<strong>in</strong>jury of the rat h<strong>in</strong>d limb, <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmentalpressures are elevated between 13.6 and 25.4 mmHg <strong>in</strong>the anterior <strong>com</strong>partment and 7.9 and 16.1 mmHg <strong>in</strong>the posterior <strong>com</strong>partment for up to 72 hours post<strong>in</strong>jury.Similar to tourniquet-<strong>in</strong>duced IR <strong>in</strong>jury, these <strong>in</strong>creaseslead to significant vascular permeability, edema formation,leukocyte roll<strong>in</strong>g and adherence, and decreases <strong>in</strong>functional capillary density, but not acute <strong>com</strong>partmentsyndrome. 75,88 More severe soft-tissue <strong>in</strong>jury also producesarterial constriction and capillary perfusion failurelast<strong>in</strong>g 5 days, 6 and the microvasculature dysfunction associatedwith severe soft-tissue <strong>in</strong>jury is alleviated withthe free radical scavenger N-acetylcyste<strong>in</strong>e. 74 Soft-tissue<strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong> the tibial <strong>com</strong>partment has also been shownto produce similar microvascular dysfunction <strong>in</strong> the rattibial periosteum, 76 whereas closed fracture of the rattibia produces microvascular dysfunction <strong>in</strong> adjacentskeletal muscle. 101 Indeed, patients often exhibit highmuscle <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressures (over 40 mmHgfor 24 hours) after tibial fractures. The <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmentalpressures produce simultaneous reductions<strong>in</strong> perfusion pressure (reflect<strong>in</strong>g low capillaryflow), which correlates highly with later muscle deficits.64 Thus, it seems the mechanism on which Foisiewas not able to elaborate <strong>in</strong> his patients may havebeen microvascular dysfunction follow<strong>in</strong>g IR <strong>in</strong>jury. IR

6 The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Historical Reflection on <strong>Syndrome</strong> <strong>Name</strong>s for CRPS<strong>in</strong>juries are so named because of the recognition thatmost of the damage that occurs follow<strong>in</strong>g prolonged ischemiaoccurs after the tissue is reperfused, a discoverymade 3 decades after Foisie’s paper.Importantly, recent evidence <strong>in</strong>dicates that IR <strong>in</strong>juriesmay cause some of the bewilder<strong>in</strong>g symptoms observed<strong>in</strong> CRPS patients. IR <strong>in</strong>juries <strong>in</strong>itially produce <strong>in</strong>creasedcapillary and postcapillary venule permeability lead<strong>in</strong>gto extensive plasma extravasation and edema, 58 a verysignificant feature of early-stage CRPS. 48,96 IR <strong>in</strong>juriesare produced by the generation of oxygen free radicalsand pro<strong>in</strong>flammatory cytok<strong>in</strong>es, 41,87,100 which produceboth microvascular dysfunction and additional IR <strong>in</strong>jury<strong>in</strong> neighbor<strong>in</strong>g tissues, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g muscle, bone, andsk<strong>in</strong>. 10 Recent evidence suggests that both oxygen-freeradicals and pro<strong>in</strong>flammatory cytok<strong>in</strong>es are elevated<strong>in</strong> CRPS, 18,38 and CRPS is alleviated by treatments aimedat reduc<strong>in</strong>g these mediators. 40,67 CRPS often spreadsbeyond dermatomal borders, and affects both sk<strong>in</strong> andvarious deep tissues. 54 This parallels what happens withIR <strong>in</strong>juries, where all tissues (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g muscle, bone,and sk<strong>in</strong>) with<strong>in</strong> the occluded area suffer the same consequences(although bone and sk<strong>in</strong> are more resistant thanmuscle). 10 While IR <strong>in</strong>juries clearly cannot account formotor abnormalities or altered sympathetic or sudomotoractivity often seen <strong>in</strong> CRPS limbs, or the occasionalspread of symptoms to the contralateral limb, it is possiblethat afferent <strong>in</strong>put from <strong>in</strong>jured muscle may be<strong>in</strong>strumental <strong>in</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g central sensitization 93 thatcould contribute to these phenomena.It could be argued that many CRPS patients do nothave the type of tissue damage that leads to IR <strong>in</strong>jury.However, CRPS <strong>com</strong>monly follows factures, spra<strong>in</strong>s, contusionsand crush <strong>in</strong>juries, athroscopic surgery, overlytight cast<strong>in</strong>g, and other edematous soft-tissue <strong>in</strong>juries.4,26,73 A <strong>com</strong>mon feature of all these conditions isan early <strong>in</strong>flammatory response <strong>in</strong> soft tissue that hasthe potential to produce microvascular and ischemicchanges <strong>in</strong> various tissues. While others have notedthat CRPS depends on an exaggerated <strong>in</strong>flammatoryresponse, 30,37 most CRPS patients are seen by pa<strong>in</strong>specialists many weeks, months, or years after theirorig<strong>in</strong>al <strong>in</strong>juries, and <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>in</strong>flammatory symptomsmay be long forgotten. If the soft-tissue <strong>in</strong>jury and<strong>in</strong>flammation is severe enough to cause a temporary(hours long) <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>com</strong>partmental pressurethat occludes capillary blood flow, a microvascular IR <strong>in</strong>jurywill occur. These microvascular <strong>in</strong>juries would thenbe expected to produce susta<strong>in</strong>ed hypoperfusion and reducednutritive blood flow. Importantly, s<strong>in</strong>ce this is mostlikely to occur <strong>in</strong> deep tissues, the ensu<strong>in</strong>g ischemicchanges may go undetected.Role of Microvascular DysfunctionIR <strong>in</strong>juries produce significant arterial vasospasms orenhanced vasoconstriction due to microvascular dysfunctionassociated with <strong>in</strong>creased responsiveness of smoothmuscleadrenoceptors to the sympathetic transmitternorep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e, 72 and a reduced production of the endogenousvasodilator nitric oxide. 47,94 Both Foisie andEvans described arterial vasospasms, and recentevidence <strong>in</strong>dicates that CRPS limbs exhibit bothreduced nitric-oxide 33 and enhanced vasoconstrictor responsivenessto norep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e. 2,7,16,89 Importantly, thema<strong>in</strong> cause of arterial vasospasm or enhancedvasoconstriction follow<strong>in</strong>g IR <strong>in</strong>jury is the dramatic lossof nitric oxide (much of which is scavenged by<strong>in</strong>creased oxygen-free radicals to produce nitrogen-freeradicals). 10,94 Thus, arterial vasospasms can bema<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed after IR <strong>in</strong>jury, even if sympathetic activityis blunted <strong>in</strong> CRPS patients, which itself would bea natural homeostatic response to the vasospasm.A very significant later consequence of IR <strong>in</strong>jury is damageto capillaries. Free radicals and cytok<strong>in</strong>es generatedby IR <strong>in</strong>jury trigger neutrophil recruitment and adhesion,capillary plugg<strong>in</strong>g, endothelial cell swell<strong>in</strong>g, and theeventual collapse of the capillary lumen, lead<strong>in</strong>g toa phenomenon called capillary no-reflow. 36,60 Capillaryno-reflow results <strong>in</strong> arterial venous shunt<strong>in</strong>g, 42 and a significantreduction of nutritive blood flow with<strong>in</strong> theaffected capillary. Importantly, arterial venous shunt<strong>in</strong>gand collapsed capillaries have been observed <strong>in</strong> the limbsof patients with CRPS. 57,90 Furthermore, IR <strong>in</strong>juries<strong>in</strong>itially produce enhanced vascular permeability thatcontributes to the damage caus<strong>in</strong>g vasospasms, but asvasospasms progress to no-reflow, plasma extravasationis dim<strong>in</strong>ished, as there is reduced blood flow with<strong>in</strong> themicrovasculature. 59 This shift from <strong>in</strong>itial high plasma extravasationto later capillary no-reflow, could expla<strong>in</strong>why many CRPS patients start out with significantedema, but then progress to a state with less edemaand more ischemia. 9,11,45 Later capillary no-reflow mayalso expla<strong>in</strong> why CRPS is less likely to respond to antisympathetictreatment with greater time follow<strong>in</strong>g syndromeonset, 1 as antisympathetic treatment likelyrelieves vasospasms, but not capillary no-reflow.Recent evidence further l<strong>in</strong>ks the fields of CRPS and IR<strong>in</strong>jury by show<strong>in</strong>g that after a h<strong>in</strong>d paw IR <strong>in</strong>jury, rodentsdevelop vascular and pa<strong>in</strong>ful symptoms similar to that exhibitedby CRPS patients. 14,46 Allodynia that developsfollow<strong>in</strong>g rat h<strong>in</strong>d paw IR <strong>in</strong>jury also depends on thegeneration of oxygen-free radicals and pro<strong>in</strong>flammatorycytok<strong>in</strong>es. 46 Importantly, after h<strong>in</strong>d paw IR <strong>in</strong>jury, ratswith vasoconstrictive hypersensitivity to norep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e(vasospasms) are more likely to develop allodynia, as wellas pa<strong>in</strong>ful responses to <strong>in</strong>traplantar norep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e. 98Similar to CRPS patients, 17 sympathetic blockade us<strong>in</strong>gguanethid<strong>in</strong>e is more effective at reliev<strong>in</strong>g allodynia <strong>in</strong>rats when performed early after h<strong>in</strong>d paw IR <strong>in</strong>jury. 99 Aswell as vasospasms, rats with h<strong>in</strong>d paw IR <strong>in</strong>juries developno-reflow over a time course that parallels allodynia, andexhibit muscle ischemia and <strong>in</strong>creased muscle lactate (asdo CRPS patients 29 ) that is directly correlated with the allodynia.46 Like CRPS patients, 91 rats with h<strong>in</strong>d paw IR <strong>in</strong>juriesalso display pa<strong>in</strong>ful responses to exercise, and parallel<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> muscle lactate and allodynia after exercise. 46Novel Therapeutics and ConclusionsThere is grow<strong>in</strong>g evidence that target<strong>in</strong>g pathologiesassociated with microvascular dysfunction and ischemia

Coderre The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 7Figure 2. Consensus views of therapy for CRPS at the end of the 20 th century. Therapeutic algorithm (‘‘Diagnosis CRPS CareCont<strong>in</strong>uum’’) with emphasis on therapeutic options <strong>in</strong> response to patient’s cl<strong>in</strong>ical progress <strong>in</strong> the rehabilitation pathway. Basedon the Interdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Pathway for CRPS prepared by an Expert Panel <strong>in</strong> Cardiff, Wales <strong>in</strong> 2001 (repr<strong>in</strong>ted with permissionfrom Stanton-Hicks et al, An updated <strong>in</strong>terdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary cl<strong>in</strong>ical pathway for CRPS: Report of an expert panel, <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Practice, John Wileyand Sons 85 ).are effective aga<strong>in</strong>st CRPS. Thus, CRPS is alleviated withfree radical scavengers, 31,67,104 and antitumor necrosisfactor-a antibodies, 40,56,80 which would mitigate the<strong>in</strong>flammatory and damag<strong>in</strong>g effects of oxygen-free radicalsand pro<strong>in</strong>flammatory cytok<strong>in</strong>es. CRPS has also beenshown to be alleviated by nitric-oxide donors and othervaosodilators, 34,55,63 or a-adrenergic antagonists, 63,68and topical or regional clonid<strong>in</strong>e, 15,28,43,69 which act by<strong>in</strong>hibition of the effects of sympathetic vasoconstrictorson vasculature smooth-muscle cells. Antioxidant vitam<strong>in</strong>C adm<strong>in</strong>istration has also recently been shown to reducethe <strong>in</strong>cidence of CRPS when adm<strong>in</strong>istrated as a prophylactictreatment after fracture. 5,102,103The very recent shift <strong>in</strong> th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about the treatmentof CRPS is reflected <strong>in</strong> the differences between a therapeuticalgorithm for CRPS outl<strong>in</strong>ed by an expert panelthat met <strong>in</strong> Cardiff <strong>in</strong> 2001 85 (Fig 2) versus theevidence-based guidel<strong>in</strong>es for CRPS published by theNetherlands Society of Rehabilitation Specialists andthe Netherlands Society of Anaesthesiologists <strong>in</strong> 2007 65(Fig 3). The 2001 algorithm lists sympathetic nerve blocksas a first <strong>in</strong>terventional pa<strong>in</strong>-management procedure

8 The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Historical Reflection on <strong>Syndrome</strong> <strong>Name</strong>s for CRPSFigure 3. Very recent views on therapy for CRPS. Summary chart of the 2007 evidence-based guidel<strong>in</strong>es for <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong>syndrome reported by the Netherlands Society of Rehabilitation Specialists and the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists. 65Repr<strong>in</strong>ted with permission of the Dutch Institute for Health Care Improvement, Evidence-Based Guidel<strong>in</strong>es Development programme(EBGD) of the Order of Medical Specialists.and lists surgical sympathectomy as a more <strong>in</strong>vasive procedureto be performed <strong>in</strong> case of <strong>in</strong>adequate or partialresponse. The 2007 Dutch evidence-based guidel<strong>in</strong>es listfree radical scavengers, 50% DMSO, and n-acetylcyste<strong>in</strong>eunder drug treatments, as well as vasodilators for ‘‘coldCRPS’’ and vitam<strong>in</strong> C as primary prevention for wrist

Coderre The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 9fractures. Importantly, these later guidel<strong>in</strong>es do not listsympathetic blockade as a first-l<strong>in</strong>e treatment, and re<strong>com</strong>mend‘‘extreme caution’’ when consider<strong>in</strong>g surgicalsympathectomy. Importantly, sympathetic blocks maystill be useful <strong>in</strong> alleviat<strong>in</strong>g CRPS pa<strong>in</strong> associated with microvasculardysfunction and deep tissue ischemia, butthey should not imply that sympathetic abnormalitiesare causative.While recent evidence po<strong>in</strong>ts to the strong possibilitythat follow<strong>in</strong>g IR <strong>in</strong>jury, arterial vasospasms, no-reflow,and deep-tissue ischemia may be key underly<strong>in</strong>g mechanismsof CRPS, one may ask the question: Why were thesemechanisms overlooked for so long? Both Evans andFoisie described arterial vasospasms and ischemia as keyfeatures present <strong>in</strong> their patients. Perhaps the sympatheticreflex hypothesis derived by Evans was just too<strong>com</strong>pell<strong>in</strong>g to allow us to enterta<strong>in</strong> other possibilities.And by concentrat<strong>in</strong>g on the sympathetic nervous system,everyone lost sight of the key role of vasospasmsand ischemia. Evans’ hypothesis was based on the earliertheories of Liv<strong>in</strong>gston, 50 a cl<strong>in</strong>ician-scientist who hada large <strong>in</strong>fluence on his contemporaries and futurepa<strong>in</strong> researchers. The ideas of Evans and Liv<strong>in</strong>gstonclearly had an impression on John Bonica, key founderand second president of the International Associationfor the Study of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>. Bonica 11,12 was a strongproponent of the idea that reflex sympatheticdystrophy depended on a vicious circle and sympatheticefferent hyperactivity, and he was <strong>in</strong>strumental <strong>in</strong> theadoption of the nomenclature proposed by Evans. Butmore than people, it is ideas that shape researchtrends, and it seems that, at the time, Evans’ idea wasmore attractive than Foisie’s. This may have stemmedfrom a neuron-centric view of pa<strong>in</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g, with anoveremphasis of the importance of nerve cells to thegeneration, as well as transmission, of pa<strong>in</strong> signals.Hopefully, recent research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs outl<strong>in</strong>ed here will <strong>in</strong>spirepa<strong>in</strong> researchers and cl<strong>in</strong>icians to consider endothelialcells and the microvasculature as important potentialgenerators of the noxious <strong>in</strong>puts critical for CRPS, andput to rest not only the name, reflex sympathetic dystrophy,but the misguided theories, research, and limitedtreatment it spawned. Perhaps more than 6 decadeslater, Foisie and his little-known paper will f<strong>in</strong>ally receivetheir due recognition, and patients with CRPS will benefitfrom the multitude of additional potential therapiesnew th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g will generate.AcknowledgmentsThe author wishes to thank Dr. Gary J. Bennett for<strong>com</strong>ments on the manuscript.References1. AbuRahma AF, Rob<strong>in</strong>son PA, Powell M, Bastug D,Boland JP: Sympathectomy for reflex sympathetic dystrophy:Factors affect<strong>in</strong>g out<strong>com</strong>e. Ann Vasc Surg 8:372-379,19942. Ackerman WE, Munir MA, Zhang J-M: Assessment of laserDoppler imag<strong>in</strong>g for the diagnosis of <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong>syndrome I. J Neuropathic <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Symp Pal 1:13-20, 20053. Albrecht PJ, H<strong>in</strong>es S, Eisenberg E, Pud D, F<strong>in</strong>lay DR,Connolly MK, Paré M, Davar G, Rice FL: Pathologic alterationsof cutaneous <strong>in</strong>nervations and vasculature <strong>in</strong> affectedlimbs from patients with <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome.<strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 120:244-266, 20064. Allen G, Galer BS, Schwartz L: Epidemiology of <strong>com</strong>plexregional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome: A retrospective chart review of134 patients. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 80:539-544, 19995. Amadio PC: Vitam<strong>in</strong> C reduced the <strong>in</strong>cidence of reflexsympathetic dystrophy after wrist fracture. J Bone Jo<strong>in</strong>tSurg Am 82:873, 20006. Amon M, Laschke MW, Harder Y, Vollmar B, Menger MD:Impact of severity of local soft-tissue trauma on long-termmanifestation of microcirculatory and microlymphaticdysfunctions. J Trauma 61:924-932, 20067. Arnold JMO, Teasell RW, Macleod AP, Brown JE,Carruthers SG: Increased venous alpha-adrenoceptors responsiveness<strong>in</strong> patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy.Ann Intern Med 83:185-192, 19938. Bennett GJ: Epilogue, <strong>in</strong> Harden RN, Baron R, Janig W(eds): <strong>Complex</strong> <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>Syndrome</strong>, Progress <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Researchand Management, Vol 22. Seattle, WA, IASP Press,2001, pp 323-3259. Birkle<strong>in</strong> F, Riedl B, Claus D, Neundorfer B: Pattern of autonomicdysfunction <strong>in</strong> time course of <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong>syndrome. Cl<strong>in</strong> Auton Res 8:79-85, 199810. Blaisdell FW: The pathophysiology of skeletal muscle ischemiaand the reperfusion syndrome: A review. CardiovascSurg 10:620-630, 200211. Bonica JJ: Causalgia and other reflex sympatheticdystrophies, <strong>in</strong> Bonica JJ (ed): The Management of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>,2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA, Lea & Febiger, 1990, pp 220-24312. Bonica JJ: The Management of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>, 1st ed. Philadelphia,PA, Lea & Febiger, 195313. Cepeda MS, Lau J, Carr DB: Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the therapeutic roleof local anesthetic sympathetic blockade <strong>in</strong> <strong>com</strong>plex regionalpa<strong>in</strong> syndrome: A narrative and systematic review.Cl<strong>in</strong> J <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 18:216-233, 200214. Coderre TJ, Xanthos DN, Francis L, Bennett GJ: Chronicpost-ischemia pa<strong>in</strong> (CPIP): A novel animal model of <strong>com</strong>plexregional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome-type I (CRPS-I;reflex sympatheticdystrophy) produced by prolonged h<strong>in</strong>dpaw ischemia andreperfusion <strong>in</strong> the rat. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 112:94-105, 200415. Davis KD, Treede RD, Raja SN, Meyer RA, Cambell JN: Topicalapplication of clonid<strong>in</strong>e relieves hyperalgesia <strong>in</strong> patientswith sympathetically ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed pa<strong>in</strong>. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 47:309-317, 199116. Dayan L, Salman S, Norman D, Vat<strong>in</strong>e JJ, Calif E, Jacob G:Exaggerated vasoconstriction <strong>in</strong> <strong>Complex</strong> <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong><strong>Syndrome</strong>-1 is associated with impaired resistance artery endothelialfunction and local vascular reflexes. J Rheumatol35:1339-1345, 200817. Driessen JJ, van der Werken C, Nicolai JP, Crul JF: Cl<strong>in</strong>icaleffects of regional <strong>in</strong>travenous guanethid<strong>in</strong>e (Ismel<strong>in</strong>) <strong>in</strong>reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 27:505-509, 1983

10 The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Historical Reflection on <strong>Syndrome</strong> <strong>Name</strong>s for CRPS18. Eisenberg E, Shtahl S, Geller R, Reznick AZ, Sharf O,Ravb<strong>in</strong>ovich M, Erenreich A, Nagler RM: Serum and salivaryoxidative analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>Complex</strong> <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>Syndrome</strong>. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>138:226-232, 200819. Evans JA: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Surg Cl<strong>in</strong> NorthAmerica 26:780-790, 194620. Evans JA: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Surg GynecolObstet 82:36-44, 194621. Evans JA: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: report of 57cases. Ann Intern Med 26:417-426, 194722. Evans JA: Sympathectomy for reflex sympathetic dystrophy:A case report of twenty-n<strong>in</strong>e cases. JAMA 132:620-623,194623. Foisie PS: Traumatic arterial vasospasm. N Engl J Med237:295-302, 194724. Frost SA, Raja SN, Campbell JN, Meyer RA, Khan AA:Does hyperalgesia to cool<strong>in</strong>g stimuli characterize patientswith sympathetically ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed pa<strong>in</strong> (reflex sympatheticdystrophy)? In Dubner R, Gebhart GF, Bond MR (eds):Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of the 5th World Congress on <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>, <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong>Research and Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Management, Vol. 3. Amsterdam,The Netherlands, Elsevier, 1988, pp 151-15625. Furlan AD, Lui PW, Mailis A: Chemical sympathectomyfor neuropathic pa<strong>in</strong>: Does it work? Case report and systematicliterature review. Cl<strong>in</strong> J <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 17:327-336, 200126. Galer BS, Henderson J, Perander J, Jensen MP: Course ofsymptoms and quality of life measurement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Complex</strong><strong>Regional</strong> <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>Syndrome</strong>: A pilot survey. J <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> SymptomManage 20:286-292, 200027. Gibbs GF, Drummond PD, F<strong>in</strong>ch PM, Phillips JK: Unravell<strong>in</strong>gthe pathophysiology of <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong>syndrome: Focus on sympathetically ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed pa<strong>in</strong>. Cl<strong>in</strong>Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35:717-724, 200828. G<strong>in</strong>tautas J, Housny W, Kraynack BJ: Successful treatmentof reflex sympathetic dystrophy by bier block with lidoca<strong>in</strong>eand clonid<strong>in</strong>e. Proc West Pharmacol Soc 42:101, 199929. Goris RJ: Conditions associated with impaired oxygenextraction, 1st ed, <strong>in</strong> Guitierrez G, V<strong>in</strong>cent JL (eds): Tissue OxygenUtilization. Berl<strong>in</strong>, DE, Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, 1991, pp 350-36930. Goris RJ: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: Model of a severeregional <strong>in</strong>flammatory response syndrome. World J Surg 22:197-202, 199831. Goris RJ, Dongen LM, W<strong>in</strong>ters HA: Are toxic oxygenradicals <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis of reflex sympatheticdystrophy? Free Radic Res Commun 3:13-18, 198732. Gourgiotis S, Villias C, Germanos S, Foukas A,Ridolf<strong>in</strong>i MP: Acute limb <strong>com</strong>partment syndrome: A review.J Surg Educ 64:178-186, 200733. Groeneweg JG, Huygen FJ, Heijmans-Antonissen C,Niehof S, Zijlstra FJ: Increased endothel<strong>in</strong>-1 and dim<strong>in</strong>ishednitric oxide levels <strong>in</strong> blister fluids of patients with <strong>in</strong>termediatecold type <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome type 1. BMCMusculoskelet Disord 7:91, 200634. Groeneweg JG, Niehof S, Wesseldijk F, Huygen FJ,Zijlstra FJ: Vasodilative effect of isosorbide d<strong>in</strong>itrate o<strong>in</strong>tment<strong>in</strong> <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome type 1. Cl<strong>in</strong> J<strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 24:89-92, 200835. Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, Wilson PR:Proposed new diagnostic criteria for <strong>com</strong>plex regionalpa<strong>in</strong> syndrome. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Med 8:326-331, 200736. Harris AG, Ste<strong>in</strong>bauer M, Leiderer R, Messmer K: Role ofleukocyte plugg<strong>in</strong>g and edema <strong>in</strong> skeletal muscle ischemiareperfusion<strong>in</strong>jury. Am J Physiol 273:H989-H996, 199737. Heerschap A, den Hollander JA, Reynen H, Goris RJA:Metabolic changes <strong>in</strong> reflex sympathetic dystrophy: A31P NMR spectroscopy study. Muscle Nerve 16:367-373,199338. Heijmans-Antonissen C, Wesseldijk F, Munnikes RJ,Huygen FJ, van der Meijden P, Hop WC, Hooijkaas H,Zijlstra FJ: Multiplex bead array assay for detection of 25 solublecytok<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> blister fluid of patients with <strong>com</strong>plex regionalpa<strong>in</strong> syndrome type 1. Mediators Inflamm 1:28398, 200639. Homans J: M<strong>in</strong>or causalgia follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>juries andwounds. Ann Surg 113:932-941, 194140. Huygen FJ, Niehof S, Zijlstra FJ, van Hagen PM, vanDaele PL: Successful treatment of CRPS 1 with anti-TNF.J <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Sympt Manage 27:101-103, 200441. Inauen W, Suzuki M, Granger DN: Mechanisms of cellular<strong>in</strong>jury: Potential sources of oxygen free radicals <strong>in</strong> ischemia/reperfusion.Microcirc Endothelium Lymphatics 5:143-155, 198942. Kennedy TJ, Miller SH, Nellis SH, Buck D, Flaim SF,Graham WP 3rd, Davis TS: Effects of transient ischemia onnutrient flow and arteriovenous shunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e h<strong>in</strong>dlimb.Ann Surg 193:255-263, 198143. Kirkpatrick AF, Derasari M: Transdermal clonid<strong>in</strong>e: Treat<strong>in</strong>greflex sympathetic dystrophy. Reg Anesth 18:140-141, 199344. Koban M, Leis S, Schultze-Mosgau S, Birkle<strong>in</strong> F: Tissuehypoxia <strong>in</strong> <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 104:149-157, 200345. Kurvers HA, Jacobs MJ, Beuk RJ, Van den Wildenberg FA,Kitslaar PJ, Slaaf DW, Reneman RS: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy:Evolution of microcirculatory disturbances <strong>in</strong> time.<strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 60:333-340, 199546. Laferrière A, Millecamps M, Xanthos DN, Xiao WH, Siau C,de Mos M, Sachot C, Ragavendran JV, Huygen FJ, Bennett GJ,Coderre TJ: Cutaneous tactile allodynia associated with microvasculardysfunction <strong>in</strong> muscle. Mol <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 4:49, 200847. Lefer AM, Tsao PS, Lefer DJ, Ma XL: Role of endothelialdysfunction <strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis of reperfusion <strong>in</strong>jury aftermyocardial ischemia. FASEB J 5:2029-2034, 199148. Leis S, Weber M, Isselmann A, Schmelz M, Birkle<strong>in</strong> F:Substance-P-<strong>in</strong>duced prote<strong>in</strong> extravasation is bilaterally<strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome. Exp Neurol183:197-204, 200349. Leriche R: La chirurgie de la douleur, 1st ed. Paris, FR,Masson et Cie, 193750. Liv<strong>in</strong>gston WK: <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Mechanisms, 1st ed. New York, NY,Macmillan, 194351. Lorento de Nó R: Analysis of the activity of cha<strong>in</strong>s of<strong>in</strong>ternuncial neurons. J Neurophysiol 1:207-244, 193852. MacKenzie J: Some po<strong>in</strong>ts bear<strong>in</strong>g on the associationof sensory disorders and visceral disease. Bra<strong>in</strong>16;321-354,189353. Mailis A, Furlan A: Sympathectomy for neuropathicpa<strong>in</strong>. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD002918, 200354. Maleki J, LeBel AA, Bennett GJ, Schwartzman RJ: Patternsof spread <strong>in</strong> <strong>Complex</strong> <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>Syndrome</strong>, Type I(Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy). <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 88:259-266, 2000

12 The Journal of <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Historical Reflection on <strong>Syndrome</strong> <strong>Name</strong>s for CRPSdirect mechanical trauma applied to leg: In vivo study <strong>in</strong> ananimal model. J Trauma 51:508-517, 200189. Teasell RW, Arnold JM: Alpha-1 adrenoceptor hyperresponsiveness<strong>in</strong> three neuropathic pa<strong>in</strong> states: <strong>Complex</strong> regionalpa<strong>in</strong> syndrome 1, diabetic peripheral neuropathicpa<strong>in</strong> and central pa<strong>in</strong> states follow<strong>in</strong>g sp<strong>in</strong>al cord <strong>in</strong>jury.<strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> Res Manage 9:89-97, 200497. Whitesides TE, Haney TC, Morimoto K, Harada H: Tissuepressure measurements as a determ<strong>in</strong>ant for the need of fasciotomy.Cl<strong>in</strong> Orthop Relat Res 113:43-51, 197598. Xanthos DN, Bennett GJ, Coderre TJ: Norep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong>ducednociception and vasoconstrictor hypersensitivity<strong>in</strong> rats with chronic post-ischemia pa<strong>in</strong>. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 137:640-651,200890. van der Laan L, ter Laak HJ, Gabreels-Festen A,Gabreels F, Goris RJA: <strong>Complex</strong> regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrometype I (RSD): Pathology of skeletal muscle and peripheralnerve. Neurology 51:20-25, 199891. Veldman PH, Reyen HM, Arnt IE, Goris RJ: Signs andsymptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: Prospectivestudy of 829 patients. Lancet 342:1012-1016, 199392. Vollmar B, Westermann S, Menger MD: Microvascularresponse to <strong>com</strong>partment syndrome-like external pressureelevation: An <strong>in</strong> vivo fluorescence microscopic study <strong>in</strong> thehamster striated muscle. J Trauma 46:91-96, 199993. Wall PD, Woolf CJ: Muscle but not cutaneous C-afferent<strong>in</strong>put produces prolonged <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> the excitability of theflexion reflex <strong>in</strong> the rat. J Physiol (Lond) 356:443-458, 198494. Wang WZ, Anderson G, Flem<strong>in</strong>g JT, Peter FW,Franken RJ, Acland RD, Barker J: Lack of nitric oxide contributesto vasospasm dur<strong>in</strong>g ischemia/reperfusion <strong>in</strong>jury. PlastReconstr Surg 99:1099-1108, 199795. Wasner G, Heckmann K, Maier C, Baron R: Vascular abnormalities<strong>in</strong> acute reflex sympathetic dystrophy (CRPS I):Complete <strong>in</strong>hibition of sympathetic nerve activity withrecovery. Arch Neurol 56:613-620, 199996. Weber M, Birkle<strong>in</strong> F, Neundorfer B, Schmelz M: Facilitatedneurogenic <strong>in</strong>flammation <strong>in</strong> <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong>syndrome. <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 91:251-257, 200199. Xanthos DN, Coderre TJ: Sympathetic vasoconstrictorantagonism and vasodilatation relieve mechanical allodynia<strong>in</strong> rats with chronic postischemia pa<strong>in</strong>. J <strong>Pa<strong>in</strong></strong> 9:423-433, 2008100. Yan SF, Tritto I, P<strong>in</strong>sky D, Liao H, Huang J, Fuller G,Brett J, May L, Stern D: Induction of <strong>in</strong>terleuk<strong>in</strong> 6 (IL-6)by hypoxia <strong>in</strong> vascular cells. Central role of the b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsite for nuclear factor-IL-6. J Biol Chem 270:11463-11471, 1995101. Zhang L, Bail H, Mittlmeier T, Haas NP, Schaser KD: Immediatemicrocirculatory derangements <strong>in</strong> skeletal muscleand periosteum after closed tibial fracture. J Trauma 54:979-985, 2003102. Zoll<strong>in</strong>ger PE, Tu<strong>in</strong>ebreijer WE, Breederveld RS,Kreis RW: Can vitam<strong>in</strong> C prevent <strong>com</strong>plex regional pa<strong>in</strong> syndrome<strong>in</strong> patients with wrist fractures? A randomized, controlled,multicenter dose-response study. J Bone Jo<strong>in</strong>t SurgAm 89:1424-1431, 2007103. Zoll<strong>in</strong>ger PE, Tu<strong>in</strong>ebreijer WE, Kreis RW,Breederveld RS: Effect of vitam<strong>in</strong> C on frequency of reflexsympathetic dystrophy <strong>in</strong> wrist fractures: A randomised trial.Lancet 354:2025-2028, 1999104. Zuurmond WW, Langendijk PN, Bezemer PD, Br<strong>in</strong>k HE,de Lange JJ, van Loenen AC: Treatment of acute reflex sympatheticdystrophy with DMSO 50% <strong>in</strong> a fatty cream. ActaAnaesthesiol Scand 40:364-367, 1996