A Synthesis of Research on Effective Interventions for Building ...

A Synthesis of Research on Effective Interventions for Building ...

A Synthesis of Research on Effective Interventions for Building ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

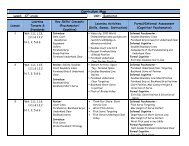

394(Table 2 c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Author/participantTreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/sampleage/design size/treatment durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures Results/effect sizes (d)Rose, 19849.5–13.1 yearsAlternating treatment designRose & Beattie, 19868.7–11.6 yearsAlternating treatment designSmith, 1979 (Study 1);8 yearsMultiple baseline,multi-element designSmith, 1979 (Study 2)12 yearsMulti-element singlesubjectdesignN = 6 Baseline: Oral reading <strong>on</strong>ly, no previewing. Silent previewing: Student read passagesilently be<strong>for</strong>e reading it aloud tothe teacher. Listening previewing: Teacher readpassage aloud while student followedal<strong>on</strong>g. Then student read passagealoud to teacher.Length and durati<strong>on</strong>: Approximately25 days <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interventi<strong>on</strong>. Length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dailyinterventi<strong>on</strong> not specified.N = 4 Baseline: Daily individual oral reading,introducti<strong>on</strong> to new words, practice <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>new words via flash cards, sentencec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> using new words, andworksheet practice. Listening previewing: Teacher readsassigned passage orally at relativelyslow c<strong>on</strong>versati<strong>on</strong>al rate (approximately130–160 wpm) as students followal<strong>on</strong>g. All other instructi<strong>on</strong>al proceduressame as baseline. Taped previewing: Identical to listening,except teacher had prerecorded thetaped passage and students followedal<strong>on</strong>g with the tape.Length and durati<strong>on</strong>: 3–4-min. sessi<strong>on</strong>sdaily. Approximately 30 days <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interventi<strong>on</strong>alternating between 3 c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s.N = 2 Baseline: Children read a passage atinstructi<strong>on</strong>al level without support. Modeling: Teacher read child’s passage<strong>for</strong> 1 minute at 100 wpm. Childc<strong>on</strong>tinued reading from where teacherstopped. Follow-up: Students read passage additi<strong>on</strong>altime.Length and durati<strong>on</strong>: Not specified, allc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s administered <strong>on</strong>ce.N = 1 Baseline: Child read a passage at instructi<strong>on</strong>allevel without support. Modeling: Teacher read passage <strong>for</strong>1 minute at 100 wpm. Child c<strong>on</strong>tinuedreading from where teacher stopped. Modeling with correcti<strong>on</strong>: Same asmodeling, plus correcti<strong>on</strong>s providedduring student reading.Words read correctly per minute Listening previewingled to faster readingrates. Both silent and listeningpreviewing appearedto be morebeneficial thanbaseline.Oral reading fluency Listening and tapedReading accuracypreviewing resultedin increased oralreading rates relativeto baseline. Listening previewingprocedure was morebeneficial than tapedpreviewing <strong>for</strong> 3 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 4participants. Error rates were noteffected by the previewingprocedures.Words read correctly per minute Interventi<strong>on</strong> resultedErrors per minutein increased speedand accuracy <strong>for</strong>both students.Words read correctly per minute Speed and accuracyErrors per minuteincreased with eachadditi<strong>on</strong>al interventi<strong>on</strong>comp<strong>on</strong>ent. Maximum speed andaccuracy achievedunder the modelingwith correcti<strong>on</strong> andpreviewing c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>.(Table c<strong>on</strong>tinues)

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2002 395(Table 2 c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Author/participantTreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/sampleage/design size/treatment durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures Results/effect sizes (d )Smith (c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Vaughn et al., 20008.5–8.8 yearsQuasi-experimentalpretest–posttestcomparis<strong>on</strong> design Modeling with correcti<strong>on</strong> and previewing:After modeling, student reread themodeled porti<strong>on</strong> and c<strong>on</strong>tinued to read<strong>for</strong> 5 minutes. Follow-up: Student read passage additi<strong>on</strong>altime.Length and durati<strong>on</strong>: Not specified, allc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s administered <strong>on</strong>ce.Partner Reading (PR; n = 7): Partnerstook turns reading (3 minutes each)with the more pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>icient reader readingfirst. 1-minute, timed reading followed.Collaborative Strategic Reading (CSR;n = 9): Partners used four-strategy approachto reading textLength and durati<strong>on</strong>: 2–3 sessi<strong>on</strong>sweekly <strong>for</strong> 12 weeks; approximately 25miuntes per sessi<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong> PR and 45minutes per sessi<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong> CSR.Gray Oral Reading Test, rate b PR vs. CSR: d = .69Gray Oral Reading Test, accuracy b PR vs. CSR: d = .65Gray Oral Reading Test, PR vs. CSR: d = .30comprehensi<strong>on</strong> bTest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reading Fluency, words PR vs. CSR: d = .16correct per minute baNegative d reflects positive outcome favoring treatment listed first. b Statistical comparis<strong>on</strong>s were not possible because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the small sample size in each group.ency than the c<strong>on</strong>trol sample (d = .17),but there were no significant differencesbetween the repeated readingc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> and the c<strong>on</strong>trol c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency (d = .10) or comprehensi<strong>on</strong>(d = .01). Moreover, <strong>on</strong> amaze task, effect sizes were small butsignificant when the repeated readingwith partners c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> was comparedwith the c<strong>on</strong>trol c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> (d = .24) andslightly higher, though still moderate,when the sustained reading c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>was compared with the c<strong>on</strong>trol c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>(d = .38).Modeling by audiotape or computer.Results from four samples (N = 12) addressedthe questi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> whether an audiotapedor computer model or preview<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the text to be read by thestudents in the sample improved thereading fluency <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> students with LD.Of the four samples, <strong>on</strong>e used a casestudy design (Moseley, 1993) and threeused a single-subject design (Daly &Martens, 1994; Gilbert, Williams, & Mc-Laughlin, 1986; Rose & Beattie, 1986).In the case study sample, the modelwas provided through a speech synthesizer,with the pace c<strong>on</strong>trolled bythe student. In this case, the student’sreading fluency decreased from 76words correct per minute at pretest to63 words correct per minute during theinterventi<strong>on</strong>. However, at the followuptest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency, the student read at112 words correct per minute, suggestingthat the overall impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the interventi<strong>on</strong>may have been positive. In <strong>on</strong>e<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the single-subject designs, Rose andBeattie (1986) compared listening previewing,in which the teacher modeledreading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the text, with a taped preview,in which the student c<strong>on</strong>trolledthe tape and followed al<strong>on</strong>g readingwith the tape. For three <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the four students,the teacher-modeled reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the text was more effective than thetaped model.Daly and Martens (1994) compared ataped model <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> passage reading withrepeated reading without a model andwith audiotaped reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a relatedword list. On measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> passagereading accuracy and fluency, thetaped reading model resulted in c<strong>on</strong>sistentlybetter per<strong>for</strong>mance than repeatedreading without a model andtaped words. The taped words c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>resulted in better per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>on</strong>a measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> word reading accuracy<strong>for</strong> three <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the four participants in thestudy.Gilbert et al. (1986) compared ataped model <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluent reading followedby three repeated readings to abaseline c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> in which the teacherintroduced vocabulary and importantph<strong>on</strong>ics elements and the studentsilently read the passage <strong>on</strong>ce. Fluencyand accuracy improved <strong>for</strong> all threestudents in both c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s.Repeated Reading Interventi<strong>on</strong>swith Multiple Features. Three groupsamples and four single-case samples(N = 52) involved interventi<strong>on</strong>s that includedrepeated reading as <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> severalinstructi<strong>on</strong>al features. The meaneffect size across interventi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> measures<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency was d = .71 and rangedfrom d = .20 to d = 1.17. These studiesare listed in Table 3.Simm<strong>on</strong>s, Fuchs, Fuchs, Mathes, andHodge (1995) compared an interventi<strong>on</strong>that combined an effective teachingcomp<strong>on</strong>ent and peer-mediated repeatedreading to traditi<strong>on</strong>al readinginstructi<strong>on</strong>. On a measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oral readingfluency, the students who receivedthe combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> effective teaching

396TABLE 3Studies Examining Repeated Reading with Multiple FeaturesAuthor/participantTreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/sampleage/design size/treatment durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures Results/effect sizes (d)Simm<strong>on</strong>s, Fuchs, Fuchs,Mathes, & Hodge, 19959.47–9.91 yearsTreatment–Comparis<strong>on</strong>D. Fuchs, Fuchs, Mathes, &Simm<strong>on</strong>s, 1996Mean age = 9.87 years(PALs group); 10.09years (No PALs group)Treatment–Comparis<strong>on</strong>Sutt<strong>on</strong>, 1991Ages not providedPre–Posttest design <strong>Effective</strong> teaching plus peer tutoring(ET+PT; n = 11): <strong>Effective</strong> instructi<strong>on</strong>alprinciples and peer tutoring using repeatedreading (3 readings/passage<strong>for</strong> first 4 weeks, 2 readings/passage<strong>for</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>d 4 weeks), story retells, andparagraph summarizati<strong>on</strong>. Comparis<strong>on</strong> (C; n = 29): Traditi<strong>on</strong>alreading instructi<strong>on</strong>.Durati<strong>on</strong>: 800 minutes Peer Assisted Learning (PALs; n = 20):Partner reading with retell (<strong>on</strong>e repeatedreading), paragraph summary,and predicti<strong>on</strong> relay. No PALs (n = 20): Traditi<strong>on</strong>al readinginstructi<strong>on</strong>.Durati<strong>on</strong>: 1,350 minutesN = 17Four-element c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>:1. Teacher modeled reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> story.2. Target students read to tutor partners.3. Partner reading.4. Target student read story to teacher.No. <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> words read in 3 min. ET + PT > C;ET + PT vs. C: d = .73No. <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> words read in 3 min. No significant differences(delayed)between groups;ET + PT vs. C: d = .53No. comprehensi<strong>on</strong> questi<strong>on</strong>s ET + PT > C;correct ET + PT vs. C: d = .82No. comprehensi<strong>on</strong> questi<strong>on</strong>s No significant differencescorrect (delayed)between groups;ET + PT vs. C: d = .36No. maze items correct in 2 min. ET + PT > C;ET + PT vs. C: d = 1.00Matched words in recall summaries No significant differencesbetween groups;ET + PT vs. C: d = 1.05Total words in recall summaries No significant differencesbetween groups;ET + PT vs. C: d = .78SAT Comprehensi<strong>on</strong>No significant differencesbetween groups;ET + PT vs. C: d = .56;Mean effect size (ET +PT vs. C): d = .73Average number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> words read PALs vs. No PALs:orally in 3 min. d = .20Average number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> correct PALs vs. No PALs:resp<strong>on</strong>ses to 10 comprehensi<strong>on</strong> d = .63questi<strong>on</strong>sNumber <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> maze items correct PALs vs. No PALs:d = .49Mean effect size (PALsv. No PALs): d = .44Brigance Test <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Oral Reading Posttest vs. Pretest:(words per minute) d = 1.17Brigance Test <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Oral Reading Posttest vs. Pretest:(errors per minute) a d = .91;Mean effect size(Posttest vs. Pretest):d = 1.04Weinstein & Cooke, 19928 years 1 m<strong>on</strong>th–10 years2 m<strong>on</strong>thsMulti-treatment, singlesubjectdesign (ABACA)N = 4Baseline: Each student read first set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>3 passages <strong>for</strong> first baseline phaseand the interventi<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. Sameprocedure was used <strong>for</strong> the sec<strong>on</strong>d set<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> passages. Third set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 passageswas used <strong>for</strong> final baseline.Interventi<strong>on</strong> (10 min./day):1. Students listened to taped model at100 wpm.2. Students asked to read passagequickly and accurately.Oral reading fluency All students madeprogress over baseline;mean gains rangingfrom 16.1 to 39.4words correct perminute. Mean gain <strong>for</strong> thefixed-rate phase = 62% Mean gain <strong>for</strong> the improvementphase= 58%(Table c<strong>on</strong>tinues)

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2002 397(Table 3 c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Author/participantTreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/sampleage/design size/treatment durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures Results/effect sizes (d )Weinstein (c<strong>on</strong>tinued)3. For fixed criteri<strong>on</strong> phase, each studentreread the passage twice daily until heor she met the specified criteri<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>90 wcpm.4. For improvement phase, studentsreread a passage until they achieved3 successive improvements.5. Results were plotted and shared withstudent immediately. Generalizati<strong>on</strong> improvedafter improvementphase from 5%to 89% but was mixed<strong>for</strong> fixed-rate phase,ranging from –25% to56%.a These effect sizes were changed to positive numbers to reflect a growth in student accuracy rather than a decrease in errors.and repeated reading per<strong>for</strong>med significantlybetter than the comparis<strong>on</strong>sample. Similar significant differenceswere found <strong>for</strong> a measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comprehensi<strong>on</strong>and <strong>for</strong> a maze measure. Althoughno other significant differenceswere noted, the mean effect size <strong>for</strong> thecombinati<strong>on</strong> interventi<strong>on</strong> versus thec<strong>on</strong>trol sample was moderate to largeat d = 73. D. Fuchs et al. (1997) compareda partner reading interventi<strong>on</strong>that included repeated readings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> textand comprehensi<strong>on</strong> activities (paragraphsummarizati<strong>on</strong> and predicti<strong>on</strong>activities) to a traditi<strong>on</strong>al reading program,yielding a low to moderatemean effect size <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> d = .44.A four-element interventi<strong>on</strong> implementedby Sutt<strong>on</strong> (1991), which includeda combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teachermodeledreading, target students’rereading to a tutor, peer-paired reading,and target students’ rereading tothe teacher, resulted in a c<strong>on</strong>siderableincrease in reading rate and a decreasein reading errors, with a large mean effectsize <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> d = 1.04. Weinstein andCooke (1992) used a similar interventi<strong>on</strong>in a single-subject design in whichstudents listened to a taped model be<strong>for</strong>erereading the passage to a particularcriteri<strong>on</strong> and then examining theirprogress as it was plotted <strong>on</strong> a graph.The four participating students all experiencedincreased fluency as a result<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this interventi<strong>on</strong>.Other Elements That Influence FluencyPer<strong>for</strong>mance in Repeated ReadingInterventi<strong>on</strong>s. Various other elements<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interventi<strong>on</strong>s may affect readingfluency. Studies that addressedthese elements are listed in Table 4.Amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text. A. L. Cohen (1988)compared the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text presentedto students as they repeatedlyread passages from a computer screen.One sample (N = 16) was presented apassage at a rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> three to five wordsat a time, whereas a sec<strong>on</strong>d sample(N = 16) had c<strong>on</strong>trol over the amount<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text that was presented. Both sampleswere compared to a c<strong>on</strong>trol sample.No significant differences werenoted between the repeated readingsamples. The sample that received<strong>on</strong>ly three to five words per screenscored significantly higher <strong>on</strong> measures<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> single- and multisyllabic wordreading accuracy. Both repeated readingsamples dem<strong>on</strong>strated improvedfluency over the c<strong>on</strong>trol c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>, witha large mean effect size <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> d = 1.98. Effectsize comparis<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the two repeatedreading groups were small,with the excepti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading accuracy(ranging from d = .56 to d = .89), favoringthe c<strong>on</strong>trolled presentati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> threeto five words per screen.Text difficulty. Three samples (N =37) were studied to better understandthe influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text difficulty in repeatedreading interventi<strong>on</strong>s. Sindelar,M<strong>on</strong>da, and O’Shea (1990) comparedrepeated reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> instructi<strong>on</strong>al-leveltexts (defined as text that could be readat 50–100 words per minute with twoor fewer errors) to repeated reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>mastery-level texts (defined as text thatcould be read at more than 100 wordsper minute). Statistically significantdifferences <strong>on</strong> a measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oral readingfluency favored the mastery-leveltext sample (d = 1.57). However, theinstructi<strong>on</strong>al-level sample significantlyoutper<strong>for</strong>med the mastery-level sample<strong>on</strong> accuracy (d = .61). No significantdifferences were identified <strong>on</strong> the measure<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comprehensi<strong>on</strong>.In a related study, Rashotte and Torgesen(1985) compared repeated reading<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text that included a high proporti<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> overlapping words withrepeated reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text in which therewas a low degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> overlap. Therewere no significant differences betweengroups. However, the c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> inwhich there were few overlappingwords per<strong>for</strong>med better than the c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>with a high degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> overlap <strong>on</strong>all measures.Number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> repetiti<strong>on</strong>s. To determinethe number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> times that studentsshould repeatedly read text <strong>for</strong> themost fluency benefit, the findings fromtwo samples (N = 54) are relevant.O’Shea et al. (1987) used a factorial designto study the relative influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> repetiti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> fluency.They used three interventi<strong>on</strong> levels: asingle reading, three repeated readings,and seven repeated readings. Ona measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oral reading fluency,main effects were identified with significantdifferences between all groups.Seven readings resulted in higher per<strong>for</strong>mancethan three readings, whichwas significantly better than a singlereading. On a measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> story retelling,there were no differences between

398TABLE 4Studies That Examined Other Elements <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Repeated Reading Interventi<strong>on</strong>sAuthor/participantTreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/sampleage/design size/treatment durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures Results/effect sizes (d)A. L. Cohen, 19888 years 7 m<strong>on</strong>ths–13 years2 m<strong>on</strong>thsMultiple-group comparis<strong>on</strong> Processing Power (PP; n = 16): Repeatedreading (4 times) with text presented3–5 words at a time. Repetitive Reading (RR; n = 16): Repeatedreading (4 times) with studentc<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text amount. No-treatment comparis<strong>on</strong> (C; n = 15).Durati<strong>on</strong>: 195–202 minutesParagraph reading speed RR vs. PP: d = .19(practiced)Paragraph reading accuracy PP vs. RR: d = .56(practiced)Paragraph reading speed PP vs. RR: d = .26(unpracticed)Paragraph reading accuracy PP vs. RR: d = .19(unpracticed)Reading fluency, final text PP vs. RR: d = .30;PP vs. C: d = 1.58;RR vs. C: d = 1.25Reading accuracy, final text PP vs. RR: d = .89;PP vs. C: d = 3.02;RR vs. C: d = 2.09Word reading speed (single PP > C; insufficient insyllable,practiced)<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong> dWord reading speed (multisyllable, PP > C; insufficient inpracticed)<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong> dWord reading speed (unpracticed) No significant differencesbetweengroups; insufficientin<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong> dPassage comprehensi<strong>on</strong>No significant differencesbetweengroups; insufficientin<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong> d;Mean effect size <strong>for</strong> repeatedreading interventi<strong>on</strong>s:d = 1.98Lovitt, T. W., & Hansen, C. L.,19768–12 yearsOne-group pretest–posttest Baseline (B) (N = 7): Students readaloud to the teacher. Teacher suppliesmissed or mispr<strong>on</strong>ounced words.Teacher records resp<strong>on</strong>ses and studentsresp<strong>on</strong>d to written comprehensi<strong>on</strong>questi<strong>on</strong>s after reading. Treatment (T): Students reread or skiplevelled passages c<strong>on</strong>tingent <strong>on</strong> theircorrect word rate and comprehensi<strong>on</strong>scores. Drill was provided <strong>on</strong> porti<strong>on</strong>s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading that were problematic.Durati<strong>on</strong>: 800 minutesCorrect word rate (cwpm)Orral error rate (epm)Percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comprehensi<strong>on</strong>questi<strong>on</strong>s correctAll students improvedin correct rate. Meangain <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9.3 cwpm. Increasesranged from2.4 cwpm to 15.3cwpm.Four <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the seven participantsdecreasedtheir error rates. Themean error rate improvedfrom 31 epmto 2.9 epm. Decreasesranged from.5 to –.9 epm.All students improved intheir comprehensi<strong>on</strong>resp<strong>on</strong>ses, with amean increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>11.9% and a range<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5.7% to 16.1%.Sindelar, M<strong>on</strong>da, & O’Shea, 1990Age not reportedTreatment–Comparis<strong>on</strong>Repeated reading–Instructi<strong>on</strong>al level(I; n = 17): Reread text 3 times at50–100 wpm.Repeated reading–Mastery level (M;n = 8): Reread text 3 times at 100 wpmor faster.Oral reading fluencyM > I; M vs. I(1 reading): d = 2.31;M vs. I (3 readings):d = 1.57(Table c<strong>on</strong>tinues)

399(Table 4 c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Author/participantTreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/sampleage/design size/treatment durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures Results/effect sizes (d)Sindelar (c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Durati<strong>on</strong>: Each c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> administered<strong>on</strong>ce.Errors per minute aNumber <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> propositi<strong>on</strong>s retoldI > M; M vs. I (1 reading):d = .88;M vs. I (3 readings):d = .61No significant differencesbetweengroups; M vs. I(1 reading): d = .78;M vs. I (3 readings):d = .34Rashotte & Torgesen, 1985(based <strong>on</strong> dissertati<strong>on</strong> byRashotte, 1984)8.6–12 yearsMultiple treatment designN = 12 Repeated reading, no overlappingwords (NO): Read stories 4 times withabout 20 words in comm<strong>on</strong> acrossstories. Repeated reading with high overlap(HO): Same as NO but with about 60words in comm<strong>on</strong>. Sustained Reading (SR): Read 4 differentstories each day.Durati<strong>on</strong>: 7 daysReading rate (slope <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> progress) Both interventi<strong>on</strong>s withrepeated readingper<strong>for</strong>med significantlybetter thansustained reading <strong>on</strong>reading rate.NO vs. HO: d = .18;NO vs. SR: d = .65;HO vs. SR: d = .35;HO slope, SRslope > 0Reading accuracy (slope <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> NO vs. HO: d = .26;progress) a NO vs. SR: d = .52;HO vs. SR: d = .24;HO slope, SRslope > 0Passage comprehensi<strong>on</strong> (slope No significant differ<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>progress)ences betweengroups; NO vs. HO:d = .10;NO vs. SR: d = .08;HO vs. SR: d = .17;Mean effect size, repeatedreading vs.sustained reading:d = .34O’Shea, Sindelar, & O’Shea,198711.3–13.6 years2 (Focus) ´ 3 (No. <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> readings)factorial designN = 29 Repeated Reading 7 (R7): Read text 7times. Repeated Reading 3 (R3): Read text 3times. Reading (R): Read text <strong>on</strong>ce.Durati<strong>on</strong>: Each treatment administered<strong>on</strong>ce.Oral reading fluencyStory retellR7 > R3 > RInsufficient in<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong>to calculate ES.R7, R3 > RInsufficient in<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong>to calculate ES.Sindelar, M<strong>on</strong>da, & O’Shea,1990Age not reported2 (Reading level) ´ 2 (No.<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> readings) factorialdesignSmith, 1979 (Study 2)12 yearsN = 25 Reading text <strong>on</strong>ce (R1). Repeated reading (R3): Reread text 3times.Durati<strong>on</strong>: Each c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> administered<strong>on</strong>ce.N = 1 Baseline: Child read a passage at instructi<strong>on</strong>allevel without support.Oral reading fluency R3 > R1, R3 vs. R1:d = 2.70Oral reading accuracy R1 > R3, R3 vs. R1:d = –.62Number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> propositi<strong>on</strong>s retold R3 > R1, R3 vs. R1:d = 1.67;Mean effect size (R3 vs.R1): d = 1.25Words read correctly per minute Fluency and accu-Errors per minuteracy increased with(Table c<strong>on</strong>tinues)

400JOURNAL OF LEARNING DISABILITIES(Table 4 c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Author/participantTreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/sampleage/design size/treatment durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures Results/effect sizes (d)Smith (c<strong>on</strong>tinued)Multi-element singlesubjectdesign. Modeling: Teacher read passage <strong>for</strong>1 minute at 100 wpm. Child c<strong>on</strong>tinuedreading from where teacher stopped. Modeling with correcti<strong>on</strong>: Same asmodeling, plus correcti<strong>on</strong>s providedduring student reading. Modeling with correcti<strong>on</strong> and previewing:After modeling, student reread themodeled porti<strong>on</strong> and c<strong>on</strong>tinued to read<strong>for</strong> 5 minutes. Follow-up: Student read passage additi<strong>on</strong>altime.Length and durati<strong>on</strong>: Not specified, allc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s administered <strong>on</strong>ce.each additi<strong>on</strong>al interventi<strong>on</strong>comp<strong>on</strong>ent.Maximum fluencyand accuracyachieved under themodeling with correcti<strong>on</strong>and previewingc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>.Weinstein & Cooke, 19928 years 1 m<strong>on</strong>th–10 years2 m<strong>on</strong>thsMulti-treatment, singlesubjectdesign (ABACA)N = 4Baseline: Each student read first set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>3 passages <strong>for</strong> first baseline phase.The same passages were used in theinterventi<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. Same procedurewas used <strong>for</strong> the sec<strong>on</strong>d set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>passages. Third set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 passageswere used <strong>for</strong> final baseline.Interventi<strong>on</strong> (10 min./day):1. Students listened to taped model at100 wpm.2. Students asked to read passagequickly and accurately.3. For fixed criteri<strong>on</strong> phase, each studentreread the passage twice daily until heor she met the specified criteri<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 90wcpm.4. For improvement phase, studentsreread a passage until they achieved3 successive improvements.5. Results were plotted and shared withstudent immediately.Oral reading fluency All students madeprogress over baseline;mean gainsranging from 16.1 to39.4 words correctper minute. Mean gain <strong>for</strong> thefixed-rate phase =62% Mean gain <strong>for</strong> the improvementphase =58% Generalizati<strong>on</strong> improvedafter improvementphase from 5%to 89% but wasmixed <strong>for</strong> fixed-ratephase, ranging from–25% to 56%.aNegative d reflects positive outcome favoring treatment listed first.the repeated reading c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, butboth repeated reading c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s resultedin significantly higher scoresthan the single reading c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>.Similarly, Sindelar et al. (1990) foundthat rereading text three times resultedin significantly better per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>on</strong>a measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oral reading fluency thanreading the text <strong>on</strong>ce. Similar differenceswere noted <strong>on</strong> a comprehensi<strong>on</strong>measure.Types <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> feedback. Findings from <strong>on</strong>esingle-subject sample relate to the influence<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> feedback during repeatedreading. Smith (1979) found that followingteacher modeling <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluentreading, providing the correct wordswhen the student read words incorrectlyduring oral reading resulted inan increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> more than 20 words correctper minute over baseline, and errorsdecreased from 13.6 to 9.4 errorsper minute.Criteria <strong>for</strong> repeated reading. Elevensingle-subject samples studied the influence<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> establishing particular criteria<strong>for</strong> repeated-reading interventi<strong>on</strong>s.Using an alternative treatment design,Weinstein and Cooke (1992) comparedrepeated reading using a criteri<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>90 words per minute (fixed rate) witha criteri<strong>on</strong> based <strong>on</strong> individual improvementas a basis <strong>for</strong> increasing thedifficulty <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the text. They found thefixed-rate criteri<strong>on</strong> more effective thanthe individual improvement criteri<strong>on</strong>,although the individual improvementseemed to facilitate generalizati<strong>on</strong> tounpracticed text.Similar to the fixed criteri<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>studied by Weinstein and Cooke(1992), Lovitt and Hansen (1976) designedan interventi<strong>on</strong> that requiredstudents to meet a particular set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> criteria(> 75 words read correctly perminute, < 4.5 errors per minute, and87% comprehensi<strong>on</strong> questi<strong>on</strong>s correct)in order to skip a difficulty level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text.

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2002 401If the three criteria were not met in7 days, the reader received drill andpractice <strong>on</strong> the difficult words andphrases in the text. The researchers reportedthat all participating studentsimproved in reading fluency duringthe per<strong>for</strong>mance-based advancementc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> by 10 words correct perminute and answered almost 12%more comprehensi<strong>on</strong> questi<strong>on</strong>s accurately.These results were maintainedat follow-up.Word Practice Interventi<strong>on</strong>sNine single-subject samples were studiedto examine the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decodinginterventi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> improvingreading fluency (see Table 5). O’Shea,Muns<strong>on</strong>, and O’Shea (1984) applied analternating treatment design to comparethe relative effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> aword drill procedure and a phrase drillprocedure. Each procedure was based<strong>on</strong> words missed during an initial oralreading baseline phase. Words missedafter oral reading were placed <strong>on</strong> flashcards, and students were given the opportunityto practice <strong>on</strong> half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thewords in isolati<strong>on</strong> (word drill). Alternatively,in the phrase drill c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>,the error words were practiced in c<strong>on</strong>textualphrases. There were negligibledifferences between alternating treatmentc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong> isolated wordreading and reading fluency. Significantdifferences between c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>swere dem<strong>on</strong>strated <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong> a measure<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> passage reading accuracy, favoringthe phrase drill c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>.Employing a multi-element design,Daly and Martens (1994) comparedtaped previewing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> words read in alist to participating students to repeatedreading c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. Studentsdem<strong>on</strong>strated greater word readingaccuracy in this taped words c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>than in the baseline or repeated readingc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. However, <strong>on</strong> measures<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> passage reading fluency and accuracy,the repeated reading c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>was c<strong>on</strong>sistently more effective.Discussi<strong>on</strong>Fluency has been identified as an essentiallink between word analysis andcomprehensi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text and is c<strong>on</strong>sidereda necessary tool <strong>for</strong> learning fromTABLE 5Studies Examining Fluency Practice at the Word LevelNumber <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> students/Author/participanttreatment descripti<strong>on</strong>/age/design length and durati<strong>on</strong> Dependent measures ResultsDaly & Martens, 19948 years 10 m<strong>on</strong>ths–11 years11 m<strong>on</strong>thsMulti-element designN = 4* All c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s followed a model, drill,and train to criteri<strong>on</strong> less<strong>on</strong> structure.* Subject Passage Preview (SP): Readpassage silently and reread <strong>for</strong> assessment.* Listening Passage Preview (LP): Listenedto audiotaped (130 wpm) passage,read list <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> unknown words, andreread passage <strong>for</strong> assessment.* Taped Words (TW): Read aloud al<strong>on</strong>gwith audiotaped word list (80 wpm).Reread list and read passage <strong>for</strong> assessment.Length and durati<strong>on</strong>: Sessi<strong>on</strong> length notspecified. Treatments lasted 21 days.Passage reading accuracy * LP > SP > TW <strong>on</strong>Passage reading fluencyaccuracy and fluencyWord reading accuracy<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> passage reading.Word reading fluency * TW c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> outper<strong>for</strong>medSP and LP<strong>on</strong> measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> wordreading accuracyand fluency.O’Shea, Muns<strong>on</strong>, & O’Shea,19847–11 yearsAlternating treatmentdesignN = 5* Baseline (Word supply): When an errorwas made during oral reading, theteacher supplied the word.* Word drill: Words were supplied byteacher during oral reading. After reading,students were drilled <strong>on</strong> half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>error words using 5" ´ 8" flash cards.* Phrase drill: Same procedure as c<strong>on</strong>trol.After reading, words were drilledusing phrases in which they occurredin text.Length and durati<strong>on</strong>: 30 min. sessi<strong>on</strong>s/day <strong>for</strong> 10 days; 300 min.No significant differ-ences between drillc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s andc<strong>on</strong>trol.Significant effects favor-ing phrase drill.Negligible differencesbetween c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s.Error words read correctlyin isolati<strong>on</strong>Error words read correctlyin passage c<strong>on</strong>textWords read correctly per minutein daily reading passage

402JOURNAL OF LEARNING DISABILITIESreading (Chall, 1983). The relati<strong>on</strong>ship<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluent oral reading and overall readingability is supported by both empiricaland clinical evidence (Meyer &Felt<strong>on</strong>, 1999; Rasinski, Padak, Linek, &Sturtevant, 1994; Reutzel & Hollingsworth,1993). Despite the importance<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency, its essential role in buildingoverall reading ability has <strong>on</strong>ly recentlybeen highlighted (NRP, 2000).Fluency appears to be particularlyimportant <strong>for</strong> students with significantreading problems, because they <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tenhave labored reading with manypauses, which results in slow and disc<strong>on</strong>nectedoral reading. This ef<strong>for</strong>tfulreading is problematic because it focusesreading at the decoding andword level, which makes comprehensi<strong>on</strong>virtually impossible. Chall (1979)described these readers as “glued toprint” (p. 41) and unable to delight inthe reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text. The students withLD who were the target group <strong>for</strong> thissynthesis represent a large subgroup <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>dysfluent readers.The Nati<strong>on</strong>al Reading Panel (2000)summarized findings about guided repeatedoral reading as a means to improvefluency and indicated that theoverall weighted effect size produced amoderate effect <strong>for</strong> repeated oral reading.The NRP presented the case thatinstructi<strong>on</strong> in guided oral reading is animportant part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a reading programand is associated with gains in fluencyand comprehensi<strong>on</strong>. Oral reading interventi<strong>on</strong>swere found to be superiorto instructi<strong>on</strong> encouraging students toread silently. Furthermore, the NRPreported that good and poor readersboth benefited from the repeatedguided reading, although they maybenefit differentially from different aspects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the treatment (Faulkner &Levy, 1999). However, the NRP readingfluency synthesis did not address theextent to which individuals with LDmight benefit from fluency interventi<strong>on</strong>sor the extent to which other types<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency interventi<strong>on</strong>s (other thanoral repeated reading) might be associatedwith improvements in fluencyand other aspects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading.The purpose <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study was toprovide a synthesis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research <strong>on</strong>fluency interventi<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>ducted withstudents with LD. Our goal was to locateall interventi<strong>on</strong> studies publishedand all dissertati<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>ducted withinthe past 25 years that evaluated the effects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency training <strong>on</strong> elementarystudents with LD. The comprehensivesearch yielded 24 studies: 8 multiplegroup, 5 single group, and 11 casestudies or single-subject design studies.Two <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the single-group studieswere part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> factorial designs that alsoincluded other samples.Be<strong>for</strong>e interpreting the findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the present synthesis, it is important t<strong>on</strong>ote that effect sizes can be c<strong>on</strong>sidered<strong>on</strong>ly within the c<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the comparis<strong>on</strong>swith which treatment groupswere c<strong>on</strong>trasted. Because effect sizesare largely dependent <strong>on</strong> the nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the comparis<strong>on</strong> groups, it is criticalthat a synthesis include detailed in<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong>regarding the comparis<strong>on</strong>s. Forthis reas<strong>on</strong>, Tables 1 through 5 includedetails <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both treatment and comparis<strong>on</strong>c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. However, comparis<strong>on</strong>groups differ c<strong>on</strong>siderably across samples,complicating the interpretati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the findings. The interpretati<strong>on</strong>s thatfollow were developed with this limitati<strong>on</strong>in mind.In general, the findings from thissynthesis suggested that repeatedreading interventi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong> studentswith LD are associated with improvementsin reading rate, accuracy, andcomprehensi<strong>on</strong>. This would providesupport <strong>for</strong> the theory <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> automaticityproposed by LaBerge and Samuels(1974) and extended as a verbal efficiencymodel by Perfetti (1977, 1985).These studies, and the theory supportingthem, provide evidence that thefocus <strong>on</strong> developing students’ rapidprocessing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> print by reading targetpassages more than <strong>on</strong>ce is <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten effectiveas a means to improve accuracyand speed, and ultimately leads to betterunderstanding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text.One procedure <strong>for</strong> enhancing fluencyis <strong>for</strong> teachers to model reading<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text by reading aloud to students(Dowhower, 1987; H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fman, 1987;Smith, 1979). Repeated reading with amodel seems to be more effective thanrepeated reading with no model, particularly<strong>for</strong> students with low fluency(e.g., Rose & Beattie, 1986; Smith, 1979).Tape- or computer-modeled readingseems more effective than having nomodel but may not be as effective asteacher modeling (Daly & Martens,1994; Rose & Beattie, 1986). Furthermore,having text read initially by amodel promoted comprehensi<strong>on</strong>, perhapsbecause it allowed students t<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ocus initially <strong>on</strong> the c<strong>on</strong>tent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the passagebe<strong>for</strong>e they read it themselves(M<strong>on</strong>da, 1989; Rose & Beattie, 1986).Asking peers, who are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten betterreaders, to serve as the model <strong>for</strong> studentswith LD was investigated in severalstudies reported here and reviewedin separate syntheses (Elbaum,Vaughn, Hughes, & Moody, 1999;Mathes & Fuchs, 1994). Repeated readingwith a partner as a means to improvingfluency has yielded somewhatequivocal results (e.g., Marst<strong>on</strong>, Deno,D<strong>on</strong>gil, Diment, & Rogers, 1995), althoughthere are few studies documentingits effectiveness al<strong>on</strong>e (Marst<strong>on</strong>et al., 1995; Mathes & Fuchs, 1994).In a separate analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>peer tutoring <strong>on</strong> broad reading outcomes,cross-age tutoring was associatedwith higher mean weighted effectsizes (.50) than cooperative partners(.00), and with peer tutoring, the role <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the student within the pair had a significanteffect <strong>on</strong> outcomes, with reciprocaltutor–tutee roles dem<strong>on</strong>stratinglow mean weighted effect sizes (.09; Elbaum,Vaughn, Hughes, & Moody,2000).Speed and accuracy have traditi<strong>on</strong>allybeen c<strong>on</strong>sidered the hallmarks ormost essential features <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency(LaBerge & Samuels, 1974; Samuels,1997). Most researchers agree that accuracyin itself is insufficient and thatstudents need to read rapidly if theyare going to understand the c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>sthat need to be made betweenideas in print (Nathan & Stanovich,1991). Variables associated with effects

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2002 403<strong>for</strong> fluency include c<strong>on</strong>trolling the difficulty<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text and providing feedback<strong>for</strong> words missed. Advancing studentsthrough progressively more difficulttext based <strong>on</strong> their per<strong>for</strong>mance seemsto enhance their overall fluency (Lovitt& Hansen, 1976; Weinstein & Cooke,1992), as does correcti<strong>on</strong> and feedback<strong>for</strong> words read incorrectly (Smith,1979). Rereading text many times andto many different people and providingprogressively more difficult textwith feedback and correcti<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong>missed words may be the comp<strong>on</strong>entsessential to improving fluency.Another approach to fluency buildingis to provide struggling readerswith text chunked in words or phrasesas a means <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> improving fluency andcomprehensi<strong>on</strong> (Young & Bowers, 1995).The research in this review reveals thatvarying the amounts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text presentedin repeated reading does not seem tochange the outcome. However, c<strong>on</strong>trollingthe amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text presentedmay be beneficial <strong>for</strong> students who areexperiencing difficulty with readingaccuracy, as it may <strong>for</strong>ce them to focus<strong>on</strong> the words <strong>for</strong> a l<strong>on</strong>ger period <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>time (A. L. Cohen, 1988).Several researchers have argued thatfluency is enhanced when reading addressesthe meaning <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the text (Anders<strong>on</strong>,Wilkins<strong>on</strong>, & Mas<strong>on</strong>, 1991). Atleast <strong>for</strong> struggling readers and studentswith dyslexia in the third grade,a fluency interventi<strong>on</strong> (repeated reading)and a comprehensi<strong>on</strong> interventi<strong>on</strong>(collaborative strategic reading) wereboth associated with gains in fluencyand comprehensi<strong>on</strong> (Vaughn et al.,2000). In this synthesis we found thatalthough comprehensi<strong>on</strong> was not typicallythe focus <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the interventi<strong>on</strong>, inmany cases fluency growth was associatedwith growth in comprehensi<strong>on</strong>(e.g., Simm<strong>on</strong>s et al., 1995; Sindelaret al., 1990). In the l<strong>on</strong>e study wherecomprehensi<strong>on</strong> instructi<strong>on</strong> was combinedwith repeated reading (D. Fuchset al., 1997), the effect sizes <strong>for</strong> growthin comprehensi<strong>on</strong> were moderate andexceeded the effect sizes <strong>for</strong> fluency.Additi<strong>on</strong>al research focusing <strong>on</strong> the relati<strong>on</strong>shipbetween fluency and comprehensi<strong>on</strong><strong>for</strong> students with LD iswarranted.Rereading text or repeated oral readingis perhaps the best documented approachto improving fluency (NPR,2000; Rashotte & Torgesen, 1985) andhas been associated with improvedoutcomes <strong>for</strong> young students (e.g.,O’Shea et al., 1987) and <strong>for</strong> college students(Carver & H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fman, 1981). Generally,interventi<strong>on</strong> research <strong>on</strong> fluencydevelopment <strong>for</strong> students with LD hasbeen dominated by research <strong>on</strong> repeatedreading. This likely reflects theapplicati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the theory that fluentreading is promoted by frequent opportunitiesto practice with familiartext and to increase exposure to words.It may also be influenced by the findingthat repeated readings do improvefluency <strong>for</strong> students with LD. Furthermore,rereading the same text moretimes is better than fewer.Future <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g>Like most research syntheses, thisstudy both answers questi<strong>on</strong>s andraises new <strong>on</strong>es. Questi<strong>on</strong>s that wouldbe valuable to address in future researchinclude,1. What aspects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> guided oral readingare associated with positiveoutcomes in fluency? To what extentdo these aspects differ based<strong>on</strong> the reading level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the student?What about the decoding ability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the student?2. When students are reading, atwhat level is repeated reading associatedwith the greatest gains influency? What about comprehensi<strong>on</strong>?3. Most research questi<strong>on</strong>s haveasked about the extent to whichfluency interventi<strong>on</strong>, particularlyrepeated reading, influences comprehensi<strong>on</strong>.What about the extentto which comprehensi<strong>on</strong> instructi<strong>on</strong>influences outcomes in fluency?This questi<strong>on</strong> is promptedby the str<strong>on</strong>g correlati<strong>on</strong> betweenfluent reading and comprehensi<strong>on</strong>(Dowhower, 1987; Shinn, Good,Knuts<strong>on</strong>, Tilly, & Collins, 1992).4. How much text needs to be includedin the repeated reading interventi<strong>on</strong>to most effectively influencefluency? Does this vary byage and reading level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> students?Should reading material bechunked and repeated at thephrase level, sentence level, ormultiple sentence level? Some researchhas suggested that wordlevelreading (repeated), such aswith flash cards, is associated withimproved outcomes in comprehensi<strong>on</strong>(Tan & Nichols<strong>on</strong>, 1997).5. Is there a small number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> students<strong>for</strong> whom automaticity is not possible(e.g., due to neurological difficulties),in which case fluencybuilding may be exceedingly difficult?What is the best way to buildcomprehensi<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong> these students?6. Are the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency-buildingactivities sustainable? Only <strong>on</strong>estudy in the present corpus (Simm<strong>on</strong>set al., 1995) included afollow-up measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency.Although Simm<strong>on</strong>s et al. (1995)reported no significant differences<strong>on</strong> this measure, further researchshould focus <strong>on</strong> this issue.Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong> PracticeFor many struggling readers, particularlystudents with LD, becoming a fluentreader is a challenge that must beovercome in order to progress from decodingto understanding what is read.Despite the integral role <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency inreading development, fluency has notplayed a prominent role in reading instructi<strong>on</strong>(Allingt<strong>on</strong>, 1983). Because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>this apparent lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> attenti<strong>on</strong> to fluencydevelopment, recent syntheses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>research <strong>on</strong> reading have highlightedthe importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> including fluencybuilding as part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> daily instructi<strong>on</strong>(Chard, Simm<strong>on</strong>s, & Kameénui, 1998;NRP, 2000; Snow, Burns, & Griffin,1998). The importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> becoming afluent reader warrants careful atten-

404JOURNAL OF LEARNING DISABILITIESti<strong>on</strong> to the evidence documentingwhich interventi<strong>on</strong>s are most effectiveat promoting reading fluency. To date,research <strong>on</strong> fluency interventi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong>students with LD has focused almostexclusively <strong>on</strong> repeated reading interventi<strong>on</strong>s.The results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the presentsynthesis have provided a more detailedlook at which features <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interventi<strong>on</strong>smake them more effective orless effective.Generally, the findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this synthesissuggest that students with LDwho are experiencing difficulties withfluent reading would benefit from interventi<strong>on</strong>sthat have multiple comp<strong>on</strong>entsfocusing attenti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> increasingthe rate and accuracy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading. Thefindings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the present synthesis supportearlier findings suggesting thatopportunities to practice reading andrereading familiar text is <strong>on</strong>e way <strong>for</strong>students with LD to enhance theirreading fluency. Although silent readinghas become a popular feature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>reading instructi<strong>on</strong> nati<strong>on</strong>wide, thereis little evidence to suggest that it is aneffective way to build students’ fluency.Equal attenti<strong>on</strong> should be paid torepeated reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> text <strong>for</strong> studentswho c<strong>on</strong>tinue to struggle with readingfluency.Another salient finding that has implicati<strong>on</strong>s<strong>for</strong> classroom instructi<strong>on</strong> isthat students benefit from having amodel <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluent reading. As repeatedreading is implemented, it will be important<strong>for</strong> teachers to c<strong>on</strong>sider thebest way to model fluency be<strong>for</strong>e studentsengage in repeated reading.Seemingly, the most effective way todo this is by having an adult providethat model. Realistically, however, resourcesare not always available <strong>for</strong> anadult to model fluent reading. In thesecases, an audiotaped or computergeneratedmodel is an effective substitute.Moreover, the findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thissynthesis support earlier findings (Elbaumet al., 1999) suggesting that usinggrouping practices that allow morepr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>icient readers to guide less ablereaders is also an effective way to buildfluency.Several other interventi<strong>on</strong> featuresshould be c<strong>on</strong>sidered as teachers developinstructi<strong>on</strong>al activities <strong>for</strong> fluencydevelopment. In instances wherecorrective feedback was combinedwith repeated reading, students weremore successful at boosting their fluency,primarily by decreasing theirreading errors. Moreover, fluency appearsto develop more quickly if deliberateattenti<strong>on</strong> is given to setting criteriaand adjusting the difficulty level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>text as students progress.Although more research is needed tobetter understand how reading fluencyand comprehensi<strong>on</strong> are related,the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this synthesis support thecombinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> instructi<strong>on</strong>al comp<strong>on</strong>entsthat focus students’ attenti<strong>on</strong>both <strong>on</strong> increasing their fluency and <strong>on</strong>improving their understanding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>what they read. It is important to notethat modeling <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluent reading alsoseems to boost students’ comprehensi<strong>on</strong>,as they not <strong>on</strong>ly hear how askilled reader reads but are able to understandthe text rather than focusingall their attenti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> decoding. Moreover,repeated reading interventi<strong>on</strong>sthat were combined with comprehensi<strong>on</strong>activities enhanced both fluencyand comprehensi<strong>on</strong>. Thus, it wouldseem to c<strong>on</strong>firm the importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> includingboth these elements in dailyinstructi<strong>on</strong>.The findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the present reviewprovide str<strong>on</strong>g support <strong>for</strong> the implementati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency-building activities<strong>for</strong> students with learning disabilities.Given the narrowly definedpopulati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> students c<strong>on</strong>sidered inthis review, further research is neededto understand the extent to which repeatedreading and other fluencybuildingactivities can enhance academicoutcomes <strong>for</strong> all readers.ABOUT THE AUTHORSDavid J. Chard, PhD, is an assistant pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> special educati<strong>on</strong> at the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Oreg<strong>on</strong>.His current interests include teacher developmentand effective instructi<strong>on</strong> in early literacyand numeracy. Shar<strong>on</strong> Vaughn, PhD, is theMollie Villeret Davis Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reading andLearning Disabilities and director <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the TexasCenter <strong>for</strong> Reading and Language Arts in theCollege <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong> at The University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Texasat Austin. Brenda-Jean Tyler, MEd, is a doctoralcandidate in the Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Special Educati<strong>on</strong>at The University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Texas at Austin.Her areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interest include sound reading instructi<strong>on</strong><strong>for</strong> English language learners withlearning disabilities and teacher preparati<strong>on</strong> <strong>for</strong>diverse students with learning disabilities. Address:David J. Chard, 5261 University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Oreg<strong>on</strong>,Special Educati<strong>on</strong> Area, Eugene, OR97403; e-mail: dchard@oreg<strong>on</strong>.uoreg<strong>on</strong>.eduREFERENCESNote. Asterisks denote articles that were includedin the synthesis.Allingt<strong>on</strong>, R. E. (1983). The reading instructi<strong>on</strong>provided readers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> differing ability.Elementary School Journal, 83, 548–559.Anders<strong>on</strong>, R. C., Wilkins<strong>on</strong>, I. A. G., &Mas<strong>on</strong>, J. A. (1991). A microanalysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>small-group, guided reading less<strong>on</strong>s: Effects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an emphasis <strong>on</strong> global storymeaning. Reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g> Quarterly, 26,417–441.Arreaga-Mayer, C., Terry, B. J., & Greenwood,C. R. (1998). Classwide peer tutoring.In K. Topping & S. Ehly (Eds.), Peerassistedlearning (pp. 105–120). Mahwah,NJ: Erlbaum.Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1966). Experimentaland quasi-experimental designs<strong>for</strong> research. Chicago: Rand McNally.Carver, R. P., & H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fman, J. V. (1981). Theeffect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> practice through repeated reading<strong>on</strong> gain in reading ability using acomputer-based instructi<strong>on</strong>al system.Reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g> Quarterly, 16, 374–390.Chall, J. S. (1979). The great debate: Tenyears later, with a modest proposal <strong>for</strong>reading stages. In L. B. Resnick & P. A.Weaver (Eds.), Theory and practice <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> earlyreading (Vol. 1, pp. 29–55). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.Chall, J. S. (1983). Stages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading development.New York: McGraw-Hill.Chard, D. J., Simm<strong>on</strong>s, D. C., & Kameénui,E. J. (1998). Word recogniti<strong>on</strong>: Instructi<strong>on</strong>aland curricular basics and implicati<strong>on</strong>s.In D. C. Simm<strong>on</strong>s & E. J. Kameénui(Eds.), What reading research tells us aboutchildren with diverse learning needs: Thebases and the basics (pp. 169–182). Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2002 405*Cohen, A. L. (1988). An evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the effectiveness<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> two methods <strong>for</strong> providing computer-assistedrepeated reading training toreading disabled students. Unpublisheddoctoral dissertati<strong>on</strong>, Florida State University,Tallahassee.Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis <strong>for</strong>the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.*Daly, E. J., & Martens, B. K. (1994). A comparis<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> three interventi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong> increasingoral reading per<strong>for</strong>mance: Applicati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the instructi<strong>on</strong>al hierarchy. Journal<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 459–469.Dowhower, S. L. (1987). Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> repeatedreadings <strong>on</strong> selected sec<strong>on</strong>d grade transiti<strong>on</strong>alreaders’ fluency and comprehensi<strong>on</strong>.Reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g> Quarterly, 22, 389–406.Ehri, L. C., & Wilce, L. S. (1983). Development<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> word identificati<strong>on</strong> speed inskilled and less skilled beginning readers.Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong>al Psychology, 75, 3–18.Elbaum, B., Vaughn, S., Hughes, M., &Moody, S. W. (1999). Grouping practicesand reading outcomes <strong>for</strong> students withdisabilities. Excepti<strong>on</strong>al Children, 65, 399–415.Elbaum, B. E., Vaughn, S., Hughes, M. T., &Moody, S. W. (2000). How effective are<strong>on</strong>e-to-<strong>on</strong>e tutoring programs in reading<strong>for</strong> elementary students at risk <strong>for</strong> readingfailure? Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong>al Psychology,92, 605–619.Faulkner, H. J., & Levy, B. A. (1999). Fluentand n<strong>on</strong>fluent <strong>for</strong>ms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> transfer in reading:Words and their message. Psych<strong>on</strong>omicBulletin and Review, 6, 111–116.*Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., Mathes, P. G., &Simm<strong>on</strong>s, D. C. (1997). Peer-assistedlearning strategies: Making classroomsmore resp<strong>on</strong>sive to diversity. AmericanEducati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g> Journal, 34, 174–206.Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins,J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency asan indicator <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading competence: Atheoretical, empirical, and historical analysis.Scientific Studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reading, 5, 239–256.*Gilbert, L. M., Williams, R. L., & McLaughlin,T. F. (1986). Use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> assisted reading toincrease correct reading rates and decreaseerror rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> students with learningdisabilities. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Applied BehaviorAnalysis, 29, 255–257.Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statisticalmethods <strong>for</strong> meta-analysis. Orlando, FL:Academic Press.H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fman, J. V. (1987). Rethinking the role <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>oral reading in basal instructi<strong>on</strong>. ElementarySchool Journal, 87, 367–374.Huey, E. B. (1908). The psychology and pedagogy<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Kameénui, E. J., & Simm<strong>on</strong>s, D. C. (2001).Introducti<strong>on</strong> to this special issue: TheDNA <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading fluency. Scientific Studies<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reading, 5, 203–210.Kuhn, M. R., & Stahl, S. A. (2000). Fluency:A review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> developmental and remedial practices(Technical Report No. 2-008). AnnArbor: University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Michigan, Center<strong>for</strong> the Improvement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Early ReadingAchievement.LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Towarda theory <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> automatic in<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong> processingin reading. Cognitive Psychology,6, 293–323.*Lovitt, T. W., & Hansen, C. L. (1976). Theuse <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tingent skipping and drillingto improve oral reading and comprehensi<strong>on</strong>.Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Learning Disabilities, 9,20–26.*Marst<strong>on</strong>, D., Deno, S. L., D<strong>on</strong>gil, K., Diment,K., & Rogers, D. (1995). Comparis<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading interventi<strong>on</strong> approaches<strong>for</strong> students with mild disabilities. Excepti<strong>on</strong>alChildren, 62, 20–37.*Mathes, P. G., & Fuchs, L. S. (1993). Peermediatedreading instructi<strong>on</strong> in specialeducati<strong>on</strong> resource rooms. Learning Disabilities<str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g> & Practice, 8, 233–243.Mathes, P. G., & Fuchs, L. S. (1994). Theefficacy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> peer tutoring in reading <strong>for</strong>students with mild disabilities: A bestevidencesynthesis. School Psychology Review,23, 59–80.Meyer, M. S., & Felt<strong>on</strong>, R. H. (1999). Repeatedreading to enhance fluency: Oldapproaches and new directi<strong>on</strong>. Annals <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Dyslexia, 49, 283–306.*M<strong>on</strong>da, L. E. (1989). The effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oral, silent,and listening repetitive reading <strong>on</strong> the fluencyand comprehensi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> learning disabledstudents. Unpublished doctoral dissertati<strong>on</strong>,Florida State University, Tallahassee.*Moseley, D. (1993). Visual and linguisticdeterminants <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reading fluency indyslexics: A classroom study with talkingcomputers. In S. F. Wright & R. Gr<strong>on</strong>er(Eds.), Facets <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dyslexia and its remediati<strong>on</strong>(pp. 567–584). L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>: Elsevier.Nathan, R. G., & Stanovich, K. E. (1991).The causes and c<strong>on</strong>sequences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> differencesin reading fluency. Theory Into Practice,30(3), 176–184.Nati<strong>on</strong>al Reading Panel. (2000). Teachingchildren to read. Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC: Nati<strong>on</strong>alInstitutes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Health.*O’Shea, L. J., Muns<strong>on</strong>, S. M., & O’Shea,D. J. (1984). Error correcti<strong>on</strong> in oral reading:Evaluating the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> threeprocedures. Educati<strong>on</strong> and Treatment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Children, 7, 203–214.*O’Shea, L. J., Sindelar, P. T., & O’Shea, D. J.(1987). The effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> repeated readingsand attenti<strong>on</strong>al cues <strong>on</strong> the reading fluencyand comprehensi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> learning disabledreaders. Learning Disabilities <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g>,2, 103–109.Perfetti, C. A. (1977). Language comprehensi<strong>on</strong>and fast decoding: Some psycholinguisticprerequisites <strong>for</strong> skilled readingcomprehensi<strong>on</strong>. In J. T. Guthrie (Ed.),Cogniti<strong>on</strong>, curriculum, and comprehensi<strong>on</strong>(pp. 20–41). Newark, DE: Internati<strong>on</strong>alReading Associati<strong>on</strong>.Perfetti, C. A. (1985). Reading ability. NewYork: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press.Rashotte, C. A. (1984). Reported reading andreading fluency in learning disabled children.Unpublished doctoral dissertati<strong>on</strong>, FloridaState University.*Rashotte, C. A., & Torgesen, J. K. (1985).Repeated reading and reading fluency inlearning disabled children. Reading <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g>Quarterly, 20, 180–188.Rasinski, T. V., Padak, N., Linek, W., &Sturtevant, E. (1994). Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluencydevelopment <strong>on</strong> urban sec<strong>on</strong>d-gradereaders. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g>, 87,158–165.Reutzel, D. R., & Hollingsworth, P. M.(1993). Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fluency training <strong>on</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>dgraders’ reading comprehensi<strong>on</strong>.Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Research</str<strong>on</strong>g>, 86, 325–331.*Rose, T. L. (1984). The effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> twoprepractice procedures <strong>on</strong> oral reading.Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Learning Disabilities, 17, 544–548.*Rose, T. L., & Beattie, J. R. (1986). Relativeeffects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> teacher-directed and taped previewing<strong>on</strong> oral reading. Learning DisabilityQuarterly, 9, 193–199.Samuels, S. J. (1997). The method <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> repeatedreadings. The Reading Teacher, 50,376–381.Shinn, M. R., Good, R. H., Knuts<strong>on</strong>, N.,Tilly, W. D., & Collins, V. (1992).Curriculum-based measurement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oralreading fluency: A c<strong>on</strong>firmatory analysis<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its relati<strong>on</strong> to reading. School PsychologyReview, 21, 459–479.