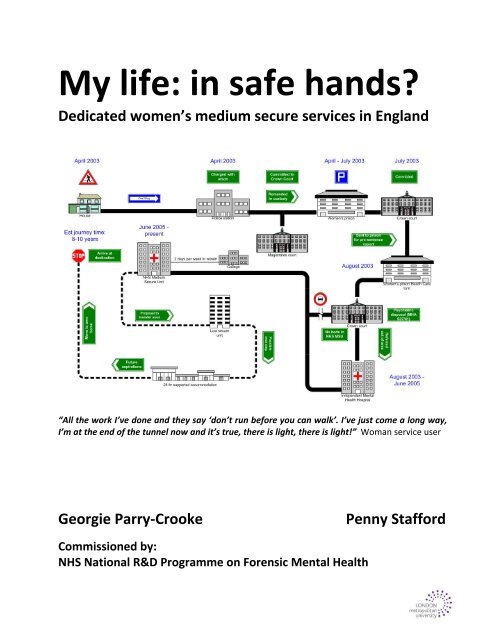

My life: in safe hands - Offender Health Research Network

My life: in safe hands - Offender Health Research Network

My life: in safe hands - Offender Health Research Network

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to thank everyone who participated <strong>in</strong> this evaluation. We believe it has been considerablyenhanced by the contribution of 50 women service users who talked openly about their experience ofmedium secure services, their hopes and aspirations for the future and how they are supported to achievethem. In addition to women participants, over 60 other <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g staff of medium secureservices, and other agencies as well as commissioners participated through questionnaires, <strong>in</strong>terviews anddiscussions as well as by provid<strong>in</strong>g documentation about policies and practices that affect this group ofexist<strong>in</strong>g and potential service users. We would like to thank them as they too talked openly with us aboutthe work they do. The Evaluation Advisory Group gave us <strong>in</strong>valuable encouragement and supportthroughout. The evaluation only came <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g as a result of work by Liz Mayne (Department of <strong>Health</strong>)who identified and supported secure services to enable many women with multiple needs take their livesback <strong>in</strong>to their own <strong>hands</strong>.F<strong>in</strong>ally, thanks are due to the Department of <strong>Health</strong> for demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g its cont<strong>in</strong>ued commitment todedicated secure services for women and for fund<strong>in</strong>g this evaluation.Georgie Parry‐CrookePenny StaffordJune 2009

ContentsPage no.Acronyms used <strong>in</strong> this reportSummaryi – vii1. Sett<strong>in</strong>g the scene: women’s medium secure services and the evaluation 11.1 Background to the evaluation 11.2 Background to women’s medium secure services 31.3 The chang<strong>in</strong>g landscape: recent policy, research and service development 41.4 The evaluation approach 91.5 The report structure 112. Mapp<strong>in</strong>g service provision across the country 152.1 The overall picture 162.2 Case study services 183. Women’s journeys through medium secure services: 253.1 Factors affect<strong>in</strong>g women’s routes to recovery 253.2 Philosophies and models of care: <strong>in</strong> theory and <strong>in</strong> practice 313.3 Implementation of policies to facilitate a route through 363.4 The importance of s<strong>in</strong>gle sex policy and provision 384. In whose <strong>hands</strong>: how are women <strong>safe</strong> and secure? 414.1 Def<strong>in</strong>itions of security 414.2 The experience of security: what did women say? 424.3 What did staff say about security? 435. Day‐to‐day realities: arrival <strong>in</strong>to and stay<strong>in</strong>g at a medium secure service 475.1 Early days: admission and arrival 475.2 Physical environments: what works for women and staff 505.3 Interventions, treatments and therapies 525.4 Service user <strong>in</strong>volvement 60

6. <strong>My</strong> <strong>life</strong> <strong>in</strong> my <strong>hands</strong>? Care Pathways, Care Plann<strong>in</strong>g and discharge 636.1 Care Pathways 646.2 Involv<strong>in</strong>g women <strong>in</strong> the process 656.3 The CPA meet<strong>in</strong>gs 686.5 CPA documents 696.5 Risk assessments 706.6 Mov<strong>in</strong>g on: the f<strong>in</strong>al steps 71Page no.7. Day‐to‐day for staff: work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a women’s medium secure service 757.1 Staff<strong>in</strong>g and staff<strong>in</strong>g structures 757.2 Recruitment and retention of staff 807.3 Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and support 807.4 The role and purpose of supervision 838. Build<strong>in</strong>g on experience: <strong>in</strong> even <strong>safe</strong>r <strong>hands</strong>? 858.1 Good practice <strong>in</strong> women’s services 858.2 What needs to be addressed for the future? 888.3 Review<strong>in</strong>g the Service Specification 91Appendices1. Evaluation methods 952. Service Specification 1213. Provider Directory January 2009 125List of tables1. Current medium secure provision for women 162. Patient groups catered for 173. Rank order<strong>in</strong>g of key construct themes 274. Elements, i.e. people, <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> repertory grids 315. Policies <strong>in</strong> place 366. Interventions, treatments and therapies 537. Service user <strong>in</strong>volvement 608. Characteristics of women participants 959. Roles of professionals participat<strong>in</strong>g 952

Acronyms used <strong>in</strong> the report:BPDBMECAMHSCBTCFTCJSCNSCPACQCCSIPDBTHCALAMDTMHAMSUNICENOGNOMSNPSANSFOATSOTPCTPTSDPALSRMOSHATEMSS (W)WEMSSWISHWORPBorderl<strong>in</strong>e Personality OrderBlack and m<strong>in</strong>ority ethnicChild and Adult Mental <strong>Health</strong> ServicesCognitive Behaviour TherapyCommunity Forensic TeamsCrim<strong>in</strong>al Justice SystemCl<strong>in</strong>ical Nurse SpecialistCare Programme ApproachCare Quality CommissionCare Services Improvement PartnershipDialectical Behaviour Therapy<strong>Health</strong> Care AssistantLocal AuthorityMulti‐discipl<strong>in</strong>ary TeamMental <strong>Health</strong> ActMedium secure unitNational Institute of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical ExcellenceNational Oversight GroupNational <strong>Offender</strong> Management ServiceNational Patient Safety AgencyNational Service FrameworkOut of area treatment servicesOccupational TherapyPrimary Care TrustPost‐Traumatic Stress DisorderPatient Advisory Liaison ServiceResponsible Medical OfficerStrategic <strong>Health</strong> AuthorityTherapeutically Enhanced Medium Secure Services for WomenWomen’s Enhanced Medium Secure ServiceWomen <strong>in</strong> Secure HospitalsWomen’s Offend<strong>in</strong>g Reduction Programme

SummaryIntroductionIn 2000, there were 39 medium secure services <strong>in</strong> England. Of these, almost all were mixed provision with only 14NHS and 79 <strong>in</strong>dependent sector medium secure beds <strong>in</strong> dedicated women‐only services. By January 2009, there were27 dedicated women‐only medium secure services (n<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dependent and 18 NHS) with a total of 51 wards andprovid<strong>in</strong>g 543 beds (261 <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dependent sector and 282 with<strong>in</strong> NHS services). There was at least one service <strong>in</strong>each health region of the country; with six <strong>in</strong> the North‐West and only one <strong>in</strong> the South‐West. Of the 27 services, 19had a gender‐specific care pathway with either a women‐only rehabilitation or pre‐discharge ward, or a women‐onlylow secure or step‐down service. Four of the 27 services were women‐only sites with five on mixed sites but with noregular mixed activities. Seventeen were on sites where some activities were mixed.The overall aim of this study was to evaluate established, new and emerg<strong>in</strong>g dedicated women’s medium securemental health services that cater for women with complex needs. The evaluation <strong>in</strong>volved 50 women service usersand over 60 professionals <strong>in</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g at the way <strong>in</strong> which services have developed and their impact on women’s lives.Sections of the report are referred to <strong>in</strong> the text below.Sett<strong>in</strong>g the sceneThe quality and <strong>safe</strong>ty of secure mental healthprovision for women has been the subject of widerang<strong>in</strong>g discussion not<strong>in</strong>g that women <strong>in</strong> mixed‐sexservices have been disadvantaged by their m<strong>in</strong>oritystatus (1.2). They have also experienced the adverseeffects of gender and other <strong>in</strong>equalities on theirtreatment and care. Successive policies across theCrim<strong>in</strong>al Justice System and mental health haveargued the need to provide gender sensitive serviceswhich help to reduce women’s offend<strong>in</strong>g rates,respond to the specific needs of women and ensurewomen’s <strong>safe</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle‐sex provision. The morerecent development of medium secure services forwomen, supported by the Department of <strong>Health</strong> (1.3),was a response to the perceived vulnerability ofwomen which has resulted <strong>in</strong> a variety of researchstudies, policy developments and operational changes<strong>in</strong> service provision. Developments <strong>in</strong>cluded theclosure of all but one high secure service for women,the open<strong>in</strong>g of three Enhanced Medium SecureServices for Women, the sett<strong>in</strong>g up of four pilotresidential high support therapeutic services forwomen, the expansion of women‐only medium secureservices.Service provision <strong>in</strong> EnglandTwo separate mapp<strong>in</strong>g exercises for this evaluation (<strong>in</strong>2006 and 2009) showed there was considerablevariation across women’s medium secure services <strong>in</strong>terms of the type, size and range of provision. InJanuary 2009 there were 15 NHS Secure Services andeight <strong>in</strong>dependent hospitals provid<strong>in</strong>g medium securecare for women <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle sex wards (2.1). These werewomen‐only services or women‐only units with<strong>in</strong>mixed secure sett<strong>in</strong>gs provid<strong>in</strong>g a total of 386 bedsacross 38 wards.Independent sector services tended to provide ahigher number of beds for women. However, theyalso had more than the recommended number perward/unit.The case study services, selected on the basis oforganisational structure and location, illustrated someof the different ways <strong>in</strong> which the women’s mentalhealth policy agenda has been implemented (2.2).Women’s journeys through the serviceKey factors affect<strong>in</strong>g women’s routes to recovery(3.1) were determ<strong>in</strong>ed through the use of repertorygrid technique to elicit the elements (people <strong>in</strong>volved<strong>in</strong> enabl<strong>in</strong>g their care) and constructs (how womendiscrim<strong>in</strong>ated between their experiences of andrelationships with all the elements/people). Women’smost frequently referenced factors were:• Relationship with staff• Trust• Positive expectations• Empower<strong>in</strong>g approach• Reduc<strong>in</strong>g isolation• Good daily support• Relational security• Holistic approach• Meet<strong>in</strong>g emotional needs• Offer<strong>in</strong>g a range of <strong>in</strong>terventions

There was consensus among service users andprofessionals about the most important attributes of awomen’s medium secure service <strong>in</strong> relation torecovery.Philosophy, models and policies <strong>in</strong> practiceEssential to service provision was the development ofa coherent and thought‐through model or philosophyof care (3.2). The case study services had adopted avariety of approaches <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Attachment Theory,Mentalisation, models of therapeutic communities,gender‐sensitive approaches, the Tidal Model andRAID (Re<strong>in</strong>force Appropriate, Implode Destructive).Where there was no clear model <strong>in</strong> place, staff andwomen described more tension, confusion and ahigher number of difficult <strong>in</strong>cidents. Staff <strong>in</strong> theseservices were also less likely to receive regular supportand supervision.Even with a clear model, services demonstrated thedifficulty at times of turn<strong>in</strong>g philosophy and policy <strong>in</strong>toevery day practice for a variety of reasons (3.3). Coreto this process was an understand<strong>in</strong>g that work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>the service and reflect<strong>in</strong>g on theory needed to be<strong>in</strong>tegrated. Policy implementation was h<strong>in</strong>dered attimes by lack of staff; time; awareness and, <strong>in</strong> largermixed medium secure services, understand<strong>in</strong>g.S<strong>in</strong>gle sex policy and provisionAt the centre of the DH Women’s Mental <strong>Health</strong> Policywas the importance of offer<strong>in</strong>g women <strong>safe</strong> places towork towards their recovery <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g access towomen‐only services where appropriate which meettheir needs (3.4). There was agreement across womenand professionals about the importance of s<strong>in</strong>gle sexprovision although this varied across case study areas.Some women preferred s<strong>in</strong>gle sex wards but wantedthe opportunity to mix with men <strong>in</strong> off‐ward areas.Male staff were considered important <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>gpositive role models although it was not always easyto f<strong>in</strong>d men who wanted to work with women.Women’s <strong>safe</strong>ty and securityWomen and professionals <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> their care wereclear, regardless of term<strong>in</strong>ology, about the importanceof a number of key factors and <strong>in</strong> particular relationalsecurity which underp<strong>in</strong>ned what services shouldwork towards (4.1). For this study, relational securitywas def<strong>in</strong>ed as embody<strong>in</strong>g high staff‐to‐patient ratios,time spent <strong>in</strong> face‐to‐face contact, a balance between<strong>in</strong>trusiveness and openness and work<strong>in</strong>g towards highlevels of trust between patients and professionals.However, the <strong>in</strong>itial survey showed that policies aboutrelational security were only <strong>in</strong> place <strong>in</strong> half ofservices. In the case study areas, services describedways <strong>in</strong> which their practice aspired to or was alreadyconsistent with this def<strong>in</strong>ition even if they did not usethe same language to def<strong>in</strong>e what they experienced.However, there was considerable <strong>in</strong>consistency andeven where a policy was <strong>in</strong> place, staff weresometimes unclear about what this meant <strong>in</strong> practice.Women described what they valued about the service<strong>in</strong> terms consistent with the ideas underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>grelational security (4.2). This <strong>in</strong>cluded:• Be<strong>in</strong>g able to talk to staff• Be<strong>in</strong>g on a women‐only ward• Be<strong>in</strong>g able to address specific issues <strong>safe</strong>ly• Be<strong>in</strong>g able to just be with staff• Be<strong>in</strong>g able to form and susta<strong>in</strong> good peerrelationshipsSome women were frustrated by the level of physicalsecurity but <strong>in</strong> particular, <strong>in</strong>consistency of securitypolicy implementation was a cause of compla<strong>in</strong>t. Staffidentified factors which h<strong>in</strong>dered embedd<strong>in</strong>g relationsecurity <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g practical implications of low stafflevels, physical and procedural obscur<strong>in</strong>g relationalsecurity and where trust was difficult to achieveamong staff a well as women service users. Cont<strong>in</strong>uityand staff changes were also identified as potentialbarriers. Staff attitudes and the use of patroniz<strong>in</strong>glanguage sometimes <strong>in</strong>hibited relational security <strong>in</strong>practice (4.3).Day‐to‐day for womenWomen who participated <strong>in</strong> the evaluation rarelyreferred to an admissions policy (5.1) but describedthe process and their arrival. Mov<strong>in</strong>g to a mediumsecure sett<strong>in</strong>g was often seen as an improvement onwhere they moved from and a route to recovery. Keyto a smooth transition were speed, effectiveconsultation with women, provision of <strong>in</strong>formation,ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g contact pre‐admission, keep<strong>in</strong>g awoman’s outside connections and ensur<strong>in</strong>g cont<strong>in</strong>uityof staff through admission and arrival at the newservice. Professionals had to make decisions based on<strong>in</strong>dividual women’s needs but <strong>in</strong> the context of thebalance of women and levels of support available <strong>in</strong>the unit at the time.The physical environment (5.2) was important towomen and staff. While new build<strong>in</strong>gs were offputt<strong>in</strong>gto some <strong>in</strong>itially, most women appreciatedii

efforts made to make the unit look and feel homely.Some would have liked more say <strong>in</strong> design and décor.S<strong>in</strong>gle rooms with en‐suite bathrooms as well asaccess to communal areas <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a gym, activityrooms, gardens and visit<strong>in</strong>g areas were all noted bywomen as contribut<strong>in</strong>g to their well‐be<strong>in</strong>g. For staff,design which <strong>in</strong>corporated zonal observation waswelcomed and the reduction <strong>in</strong>, what were seen to be<strong>in</strong>trusive, one‐to‐one observations helped to ensurestaff were available to provide escorts and be <strong>in</strong>volved<strong>in</strong> on and off‐ward activities.Services offered a range of <strong>in</strong>terventions, treatmentsand therapies (5.3). They were concerned thatwomen found ways of talk<strong>in</strong>g about their traumaticexperiences despite varied views about the type ofpsychological therapy to provide and when it shouldbe offered. In addition to psychological therapies,some offered specialist therapies from healthy liv<strong>in</strong>gto eat<strong>in</strong>g disorders. Formal, structured timetableswere mixed with <strong>in</strong>formal leisure activities and acrossservices respond<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>in</strong>itial survey almost twothirds of women took part <strong>in</strong> community out<strong>in</strong>gs,shopp<strong>in</strong>g and social events.Women and staff recognized the value of ‘<strong>in</strong>formal’activities (5.3). Women wanted to do what was‘ord<strong>in</strong>ary’. Some staff and other professionals saw thisas hav<strong>in</strong>g a therapeutic potential <strong>in</strong> the same way thatmore formal <strong>in</strong>terventions were <strong>in</strong>tended to have.A dedicated Occupational Therapy (OT) service wasvalued where it was available. OTs worked withwomen to <strong>in</strong>crease their levels of <strong>in</strong>dependence andconfidence through education, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and workopportunities. Mixed‐sex services aimed to providesome women‐only activities. Social Work was anotherimportant source of support to women who wantedcontact with their families. This was sometimes seenas a separate area of provision but one social workerwanted to see ward staff <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> traditional socialwork issues as a means of support<strong>in</strong>g women andbuild<strong>in</strong>g team relationships.Access to sufficient and appropriate physicalhealthcare was not always provided (5.3). Womenservice users were particularly concerned that theirneeds were not be<strong>in</strong>g met <strong>in</strong> relation to see<strong>in</strong>g a GP orother doctors.Advocacy was provided <strong>in</strong> some but not all servicesand rarely was this gender‐specific. Few of the women<strong>in</strong>terviewed had sought out support from anadvocate. This may have been due to the underresourc<strong>in</strong>gof advocacy services and thus time‐limitsplaced on those offer<strong>in</strong>g to support women. However,advocates were <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g some women<strong>in</strong> a range of ways <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g practical problems and <strong>in</strong>issues relat<strong>in</strong>g to the unit or ward environmentA further aspect of day‐to‐day <strong>life</strong> for some womenwas their <strong>in</strong>volvement as service users <strong>in</strong> provisionand governance (5.4). The level and type ofopportunity ranged from unit/ward meet<strong>in</strong>gs,patients’ councils to representation on cl<strong>in</strong>icalgovernance groups and membership of a regionalservice user <strong>in</strong>volvement strategy group. Womenwere encouraged to be <strong>in</strong>volved but motivation to doso was a problem for some. Others were deterred byconcerns that change did not appear to result on thebasis of service user <strong>in</strong>volvement.Care pathways, plann<strong>in</strong>g and dischargeThe Care Programme Approach (CPA) provides theoverarch<strong>in</strong>g framework for the provision of mentalhealth services <strong>in</strong> England. Implicit is the <strong>in</strong>volvementof the person us<strong>in</strong>g the service and whereappropriate, their carer. The key to successful CarePlann<strong>in</strong>g and Care Pathways lay <strong>in</strong> the relationshipsbetween women service users, their care coord<strong>in</strong>atorand the team <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the care overall.Not all services <strong>in</strong>vited women to attend the whole ofthe CPA meet<strong>in</strong>g and some did not always want toattend (6.2). However, women did want to believethat they had made a significant contribution throughtheir own and others’ reports. Staff and womenservice users reported <strong>in</strong>consistencies of approach tocare plans and <strong>in</strong>put to CPAs which had resulted <strong>in</strong>some women challeng<strong>in</strong>g the content of report<strong>in</strong>g tocare teams and at review meet<strong>in</strong>gs (6.3). Women’s<strong>in</strong>volvement was patchy and ranged from one casestudy area where women said they had little or no<strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> their Care Plans to one area wherewomen were <strong>in</strong>vited to provide a weekly report toward meet<strong>in</strong>gs about their care and progress. It wasnot clear that the impact of gender was be<strong>in</strong>gconsidered consistently <strong>in</strong> care plann<strong>in</strong>g, review orwith care coord<strong>in</strong>ators.Women service users and professionals agreed thatthere was a lack of suitable move‐on accommodation(6.6). Access to rehabilitation wards or low secureservices was severely limited. This had resulted <strong>in</strong> abottle‐neck situation until such time as appropriateiii

provision could be provided. In January 2009, only 12of 27 women’s medium secure services provided arehabilitation ward and just over half (14) had accessto their own low secure services. There was someevidence of <strong>in</strong>creased support provided by communityforensic teams to enable women to move <strong>in</strong>to thecommunity. Four pilot community therapeuticresidential services have been established for womenmany of whom will come from medium secureprovision.Day‐to‐day for staffWomen’s experience of medium secures services wasshaped by the staff and other professionals who theycame <strong>in</strong>to contact with. The composition of theworkforce, the provision of a multi‐discipl<strong>in</strong>ary teamand offer<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and support to staff wereessential <strong>in</strong> the delivery of services. Services wantedto work with dedicated, stable staff teams with anappropriate gender mix. However, given difficulties ofrecruitment and retention <strong>in</strong> areas, it was rare thatthis was achieved (7.1). Services looked for staff whowere motivated, committed and empowered <strong>in</strong> theirwork (7.2). In mixed‐sex services it was not alwayspossible to apply to work with women only. Thusthere was an element of uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about therecruitment of appropriate staff. Services tried tobuild up a regular pool of agency staff <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terestsof consistency on the unit.Although staff at all levels considered tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g andsupervision key to effective delivery, there wereconsiderable gaps between policies and whathappened <strong>in</strong> practice result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> many staff receiv<strong>in</strong>gno gender awareness tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (7.3). Reflectivepractice, supervision and access to counsell<strong>in</strong>g andsupport were recommended <strong>in</strong> the servicespecification. These were on offer and usuallyrequired <strong>in</strong> the case study services. However, due toshift patterns, the demand on qualified staff, limitedtime for ‘supervisees’ and sometimes lack ofconfidence among newly qualified/unqualified staff toseek support, supervision frequently took secondplace to service delivery (7.4).Build<strong>in</strong>g on experienceThe evaluation identified many ways <strong>in</strong> which serviceshad addressed the specific needs of women and<strong>in</strong>deed, some providers had been <strong>in</strong>vited to advisemen’s services on their philosophy of care andspecifically relational security. Good practice wasidentified <strong>in</strong> a variety of ways (8.1).Delivery of differential care to meet the specificneeds of women1. Philosophies of care for work<strong>in</strong>g with womenwere embedded with<strong>in</strong> the daily practice of mostcase study services based on gender sensitivepractice, promot<strong>in</strong>g a psycho‐social approachtak<strong>in</strong>g account of the context of women’s mentaldistress and acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g the impact of traumaand abuse on women’s mental health.2. Staff recruitment policies aimed to achieve a 7:3female to male gender ratio, with male staffprovid<strong>in</strong>g positive role models for women,although not all services had managed this yet.They also sought to appo<strong>in</strong>t ward staff with anactive <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> and desire to work with women,and <strong>in</strong> most areas, the <strong>in</strong>duction and on‐go<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>servicetra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cluded women’s mental healthissues and gender specific practice.3. Dedicated psychologists for women’s serviceswere able to undertake formulation‐basedassessments and treatment plann<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g psychological and socialperspectives acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g the importance ofthe woman’s story and <strong>life</strong> experiences andseek<strong>in</strong>g collaboration with the woman, with herviews and objectives be<strong>in</strong>g noted.4. Purpose‐built facilities as stand alone or attachedto ma<strong>in</strong> mixed‐units usually offered structuredprogrammes of therapeutic gender specificactivities as well as women be<strong>in</strong>g able to accessmixed‐sex sessions if available and appropriate.5. The Assessment and Care Plann<strong>in</strong>g Approaches<strong>in</strong> place suggested that some were formulationbasedencompass<strong>in</strong>g a biological, psychologicaland social perspective and acknowledged thewoman as an expert <strong>in</strong> her own “story” provid<strong>in</strong>ga basis for women to feel they were <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong>their care plann<strong>in</strong>g.Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g women’s psychological and physical<strong>safe</strong>ty1. Relational security was well provided for <strong>in</strong> mostcase study areas with<strong>in</strong> regular professionalpractice by staff members on the wards and thestrong therapeutic relationships they built withthe women. Staff were provided withopportunities to develop reflective practice andwere supported to develop therapeuticrelationships with<strong>in</strong> appropriate professionalboundaries through regular group and <strong>in</strong>dividualsupervision.iv

2. Extra Care, Intensive Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Suites or HighSupport Areas on women’s wards allowedwomen who were acutely ill to be cared for awayfrom the ma<strong>in</strong> ward area. These areas were usedas a short term facility only. They providedwomen who were acutely distressed and at risk ofharm<strong>in</strong>g themselves or others with a <strong>safe</strong> butcomfortable environment without the need toisolate them completely, but where <strong>in</strong>tensivenurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>put and emotional support from staffwas available to them.3. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical nurse and other specialists wereemployed with<strong>in</strong> some women’s servicesprovid<strong>in</strong>g risk assessment, care plann<strong>in</strong>g,support and therapeutic and educational<strong>in</strong>terventions for women who, e.g. self <strong>in</strong>jure, aswell as advice and support to members of thecare team <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> their care.4. The gender sensitive practice developed onwards supported staff to work towards deescalationus<strong>in</strong>g means other than control andrestra<strong>in</strong>t techniques for manag<strong>in</strong>g women’sbehaviour and it was reported that the use ofcontrol and restra<strong>in</strong>t techniques had become lessfrequent.5. The physical layout of the women’s wards wasmore likely to have been designed to allow zonalobservation with<strong>in</strong> the ma<strong>in</strong> day areas as analternative to <strong>in</strong>tensive one‐to‐one observations,which women often found <strong>in</strong>trusive.6. Team nurs<strong>in</strong>g approaches were developed acrossmost women’s wards so there was always amember of each woman’s team on duty who wasfamiliar with her care plan and <strong>in</strong>dividualformulation.Facilitat<strong>in</strong>g recovery for women, rehabilitation andresettlement1. Seamless care pathways Hav<strong>in</strong>g identified theneed for a gender‐specific route out of mediumsecure care for many of their women service users,some services have worked with regional teamsand commissioners to develop a seamless carepathway for women. Several wards worked with<strong>in</strong>ternal care pathways for women with markersfor progress. One service began the process preadmissionAnother described its access to aCommunity Forensic Team for women whorequired this support once discharged from the<strong>in</strong>patient service.2. The therapeutic treatment approaches on somewomen’s wards meant that women weresupported to develop knowledge and awareness oftheir own mental health needs. This was facilitatedby the women be<strong>in</strong>g given the opportunity toexplore their <strong>life</strong> stories and experiences <strong>in</strong> theirown time and with<strong>in</strong> the context of a trust<strong>in</strong>gtherapeutic relationship, to reach a sharedunderstand<strong>in</strong>g of how this impacted on theirmental well‐be<strong>in</strong>g.3. Women service user <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> serviceplann<strong>in</strong>g and development had enabled somewomen to take on responsibility for facilitat<strong>in</strong>guser group meet<strong>in</strong>gs and be<strong>in</strong>g representatives atexternal user networks and meet<strong>in</strong>gs.4. Social and vocational opportunities In one service,women had access to a voluntary organizationcommissioned to provide education and workrelatedtra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and social opportunities <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g,for <strong>in</strong>stance, office work, desktop publish<strong>in</strong>g,participation <strong>in</strong> the runn<strong>in</strong>g of a social club/caféfor service users and advice about external tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gand career opportunities. Women were alsocontribut<strong>in</strong>g to decision mak<strong>in</strong>g about ward andother activities <strong>in</strong> some areas.5. Provision of family/child visit<strong>in</strong>g suitesappropriate for children were seen as aconsiderable improvement on previous facilities.Structural and organisational factors1. Multi‐discipl<strong>in</strong>ary teams brought key staff andwomen service users together <strong>in</strong> decision‐mak<strong>in</strong>gprocesses. Staff across case study areasappreciated the value of this model of work<strong>in</strong>g.2. Streaml<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g adm<strong>in</strong>istration wherever possiblefrom referral to discharge helped to ensure asmooth pathway <strong>in</strong>to and through a service. This<strong>in</strong>cluded new computerized systems for record<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>formation and complet<strong>in</strong>g CPA documentation.One service worked with staff on how they wrotereports to reduce judgmental language andimprove the overall balance of their report<strong>in</strong>g.3. Monitor<strong>in</strong>g activity was required <strong>in</strong> all servicesto provide data to commissioners and/or parentorganisations. Several had <strong>in</strong>troduced additionalways of captur<strong>in</strong>g service delivery, e.g. throughsatisfaction surveys <strong>in</strong> one case designed withwomen service users, staff tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g needs analysisand take up of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and support, as a means ofservice development. Two case study serviceswere develop<strong>in</strong>g research to determ<strong>in</strong>emean<strong>in</strong>gful ways of measur<strong>in</strong>g outcomes.Professionals and women service users also identifiedsignificant gaps and areas where there was room forv

development and improvement (8.2). On the basis ofthe case studies and review of documentation, wehave listed a range of areas which policy makers andservice providers may wish to consider for futuredevelopment.CONSIDERATIONS: ProcessesModels of care:• A written policy for relational security needs tounderp<strong>in</strong> service provision as an aid toconsistency of practice and essential to protectwomen at risk of suicide or self harm as well asaggressive behaviour.• Models of care (whether s<strong>in</strong>gle or based on arange of philosophical precepts) need to besupported by policy and operational practicedocumentation which articulate the approach andits use <strong>in</strong> the service for all staff.Referrals and admissions:• Women need to be able to access a bed <strong>in</strong> theirown geographical area unless they requirespecialized care outside the remit of NHSprovision, and it may be useful for levels ofreferrals and admissions and unmet demand forlocal women’s medium secure placements to beclosely monitored and reviewed.• Women were still not be<strong>in</strong>g appropriatelydiverted from the Crim<strong>in</strong>al Justice System, andthey were often remanded to prison even whenclear history of mental illness. There was little <strong>in</strong>reach <strong>in</strong>to women prisons, and delays <strong>in</strong> transfersto hospital sett<strong>in</strong>gs.• Admission processes need to reflect the womanservice user’s situation and balance this with thecomposition of the unit.• Time is needed for effective admissions <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gopportunities for women to visit the unit and bevisited by staff to <strong>in</strong>itiate the care plann<strong>in</strong>gprocess.Care plan development and implementation:• The development of <strong>in</strong>dividual care plans needs tobe consistent with<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual services. Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gfor staff on the care plan approach with clearerguidance would help to ensure greaterconsistency.• The implementation of <strong>in</strong>dividual care plans needsto be consistent to avoid patch<strong>in</strong>ess of provision,e.g. situations where rehabilitation for somewomen was compromised due to the lack ofavailability of staff.• There is a need for gender sensitive riskassessments and for histories of abuse be<strong>in</strong>gadequately taken <strong>in</strong>to account <strong>in</strong> thedevelopment of care plans.• The recent guidance on CPA recommends that <strong>in</strong>future service users are placed at the centre of theCPA process and are fully <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> review<strong>in</strong>gtheir own care plans.Discharge plann<strong>in</strong>g:• Increased step down facilities need to cont<strong>in</strong>ue tobe developed as soon as possible to unblockexist<strong>in</strong>g bottle‐necks <strong>in</strong> some services.• It would also be helpful for discharge plann<strong>in</strong>g tobe commenced from day one of admission, withfor example, home area care coord<strong>in</strong>ators be<strong>in</strong>gasked to identify both possible future communityplacements for when a secure sett<strong>in</strong>g is no longerrequired by the woman, and for the responsibilityfor fund<strong>in</strong>g such future community placements tobe agreed and planned for <strong>in</strong> advance.• Home‐area care coord<strong>in</strong>ators and care teammembers could also be more actively <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong>the CPA process dur<strong>in</strong>g the women’s stay at theunit.Meet<strong>in</strong>g diverse needs:• Where a s<strong>in</strong>gle women’s ward forms part of theservice (as <strong>in</strong> two case study areas), considerationneeds to be given to the use of communal spaceand provid<strong>in</strong>g for women who may wish to be <strong>in</strong>quieter areas away from ma<strong>in</strong> ward areas.PracticalitiesEnvironment:• Due to the new Standards for MSUs there is nowa requirement for 5.2 metre perimeter fence forall medium secure units, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g women’sservices even if this is not seen as appropriate.However, environmental security is still importantand should be emphasized due to the risk of selfharm.• Policies need to be implemented which addresshow to deal with environmental risk and itsreview.• Services not <strong>in</strong> purpose build units need toconsider how best to provide zonal rather thanone‐to‐one observations.• Wards need to have 10 and a maximum of 12beds.vi

Activities/OT:• Women’s services <strong>in</strong> mixed‐sex units withoutdedicated OTs may wish to consider facilitat<strong>in</strong>g an<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> gender specific groups and activitiesand improve access to activities for women whoare not able to leave the ward or are not able to,or choose not to, attend mixed‐sex activities.Service user <strong>in</strong>volvement:• All services need to consider ways of encourag<strong>in</strong>gwomen to participate as part of their progress.They also need to ensure that feedback isprovided to avoid tokenism.Staff<strong>in</strong>g:• Services need to give consideration torecruitment and as far as possible recruit staffspecifically to the women’s service.• All services need to have job descriptions andperson specifications which reflect theirphilosophies and gender‐sensitive practice.Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and supervision:• Increased resources <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g time are needed byall services to ensure that tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and supervisionare always available and attended. Take up needsto be monitored by unit/ward managers to furtherensure attendance.• In some areas staff were not receiv<strong>in</strong>gappropriate gender tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g on genderissues as they affect women on the ward andimportantly <strong>in</strong> the community needs to be moreconsistently provided.• Additional models for support need to beencouraged <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g (as already happens <strong>in</strong>some services) peer‐support, mentor<strong>in</strong>g andshadow<strong>in</strong>g for new staff.Primary care:• Lack of access to primary health care services tomeet the physical health care, public health andscreen<strong>in</strong>g issues for women had been identified asa problem at some units.• Standards and Criteria for Women <strong>in</strong> MediumSecure Care from the Quality <strong>Network</strong> forForensic Mental <strong>Health</strong> Services requir<strong>in</strong>g womenmedium secure service to provide access to afemale GP and Practice Nurse, and to appropriatescreen<strong>in</strong>g and well‐women services.The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from the evaluation suggest that thereare a number of ways <strong>in</strong> which the ServiceSpecification could now be updated to reflect thelearn<strong>in</strong>g from dedicated women’s medium secureservices s<strong>in</strong>ce the Implementation Guidance waspublished (8.3)Bartlett, A., & Hassell, Y. (2001). Do women needsecure services? Advances <strong>in</strong> Psychiatric Treatment, 7,302‐309.Forensic Directory (2009) St Andrew’s <strong>Health</strong>careCSIP (2008) Refocus<strong>in</strong>g the Care Programme ApproachTucker, S. & Ince, C. (2008) “Standards and Criteria forWomen <strong>in</strong> Medium Secure Care” Royal College ofPsychiatry: Quality <strong>Network</strong> for Forensic Services.vii

1: Sett<strong>in</strong>g the scene: women’s medium secure services and the evaluationWell, I suppose here it’s different from the high secure hospital I was <strong>in</strong>, you know? I can go out <strong>in</strong> thecommunity, on trips, I can go shopp<strong>in</strong>g. It’s really normal compared to where I was, very normal. Sowhen I came here it was a big change for me, I’d been locked up on big wards. I was there <strong>in</strong> 1989 and myfirst shopp<strong>in</strong>g trip, because I was mov<strong>in</strong>g on, was 2002 and that was the first time that I’d really seen theoutside world, you know? And that was just to shop a little bit and back but here you can, if you want,<strong>in</strong>stead of go<strong>in</strong>g shopp<strong>in</strong>g, you can go to the c<strong>in</strong>ema and you can go to b<strong>in</strong>go. They do community tripsfor a few of us who’ve got community leave, you know? I hadn’t seen those th<strong>in</strong>gs for years. I’d neversat <strong>in</strong> a bar and ate someth<strong>in</strong>g, it just didn’t feel normal to me, but now you just feel you are normal andyou are a human be<strong>in</strong>g, you know, you don’t feel like that at that k<strong>in</strong>d of hospital. I’m glad that peopleare mov<strong>in</strong>g off, especially females, because some don’t need to be <strong>in</strong> that k<strong>in</strong>d of place – I mean, I don’tneed to be, I didn’t need to be <strong>in</strong> there, you know? I’m glad … … gett<strong>in</strong>g out, to a better place. It was no<strong>life</strong> there really.Woman service userIn 2000, there were 39 medium secure services <strong>in</strong> England. Of these, almost all were mixed provisionwith only 14 NHS and 79 <strong>in</strong>dependent sector medium secure beds <strong>in</strong> dedicated women‐only services 1 .In January 2009, there were 27 dedicated women‐only medium secure services (n<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dependent and 17NHS) with a total of 51 wards and provid<strong>in</strong>g 543 beds (261 <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dependent sector and 282 with<strong>in</strong> NHSservices) 2 . There was at least one service <strong>in</strong> each health region of the country; with six <strong>in</strong> the North‐Westand only one <strong>in</strong> the South‐West. Of the 27 services, 12 had either a women‐only rehabilitation or predischargeward, of which seven provided a women‐only low secure or step‐down service. Five offered awomen‐only low secure service but no rehabilitation or pre‐discharge ward. Four of the 27 services werewomen‐only sites with five on mixed sites but no regular mixed activities. Seventeen were on sites wheresome activities were mixed.This evaluation <strong>in</strong>volved 50 women service users and over 60 professionals <strong>in</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g at the way <strong>in</strong> whichservices have developed and their impact on women’s lives.1.1 Background to the evaluationThe overall aim of this study was to evaluate established, new andemerg<strong>in</strong>g dedicated women’s medium secure mental health services thatcater for women with complex needs. It was funded by the NHS <strong>Research</strong>& Development for Forensic Mental <strong>Health</strong> and approved by the SouthEast Multi‐site <strong>Research</strong> Ethics Committee. The evaluation was supportedby an Advisory Group which <strong>in</strong>cluded women service users.The quality and <strong>safe</strong>ty of secure mental health provision for women hasbeen the focus of research and campaigns 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 and recent policy<strong>in</strong>itiatives 7 . There are consistent and <strong>in</strong>ter‐related themes <strong>in</strong> thisliterature. First, it is repeatedly noted that women with<strong>in</strong> mixed secure

services have been disadvantaged by their m<strong>in</strong>ority status and as aconsequence they have received services that have been primarilydeveloped with men <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, are often unfairly affected by <strong>in</strong>stitutionalresponses to the behaviours of men, and are at risk of furtherpsychological damage 8 , 9 , 10 .Second, evidence has accumulated about the adverse effects of genderand other <strong>in</strong>equalities on the treatment and care of women <strong>in</strong> secureprovision 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 . This <strong>in</strong>cludes the operation of double standards ofbehaviour, pernicious forms of misogyny 15 , 16 and limited access to workand tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 17 .Third, there is <strong>in</strong>creased awareness of the risk to women of harassmentand assault <strong>in</strong> mixed sex facilities 18 , 19 , 20 accompanied by the recognitionthat their therapeutic and <strong>safe</strong>ty needs are unlikely to be met <strong>in</strong> suchcontexts.One consequence of these concerns is that local high and medium secureunits frequently have been deemed unsuitable for ‘difficult’ women.Women‐only wards and units have been pioneered <strong>in</strong> a range of provision<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g dedicated medium secure services for women <strong>in</strong> the<strong>in</strong>dependent sector, and despite the costs and the implications of out ofarea placement this <strong>in</strong>volves it has become the emergent solution formany commissioners and providers 21 . There has also been a rapidexpansion of NHS women only medium secure units. The number of bedshas risen from just over 20 <strong>in</strong> 2000 to nearer 200 <strong>in</strong> 2006, an almost 10fold <strong>in</strong>crease. Nonetheless, Hassell and Bartlett 22 caution that thisdevelopment is likely to have a negative impact on the cont<strong>in</strong>uity of carefor <strong>in</strong>dividual women patients. Furthermore, as the annual costs of such aplacement are typically <strong>in</strong> excess of £125,000, this curtails thedevelopment of community based services that offer both diversion fromsecure service and opportunities for appropriate discharge.The recent development of ‘women’s services’ which is receiv<strong>in</strong>g policysupport from the Department of <strong>Health</strong> 23 , 24 has been largely a responseto the perceived vulnerability – and to a lesser degree the m<strong>in</strong>ority status– of women <strong>in</strong> low and medium secure services. Pilot<strong>in</strong>g and thenprovid<strong>in</strong>g – through Inequality Agenda Ltd – a national tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gprogramme for staff work<strong>in</strong>g with women <strong>in</strong> secure services 25 hasprovided us with valuable <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to the demands and possibilities ofchange. It is encourag<strong>in</strong>g to f<strong>in</strong>d with<strong>in</strong> some services a real concern tomeet the mental health needs of women patients and not to ignore orreplicate the damage and deprivation of their earlier lives: we welcomedthis opportunity to evaluate these changes more systematically.Women’s m<strong>in</strong>ority statusis also suggested tocontribute to their be<strong>in</strong>gdeta<strong>in</strong>ed at levels ofsecurity that are muchhigher than they need(Bartlett, 2001).High security hospitalsalways had a degree ofservice segregation.However, <strong>in</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>gwomen‐only wards andunits the problems andneeds of women patients<strong>in</strong> the sector have beenbrought sharply <strong>in</strong>to focusfor many service providers.Historically, recruitmentand retention of staff werea particular problem withwomen’s wards be<strong>in</strong>gcharacterized as chaoticand violent. While this ledsome staff to concludethat ‘women together area nightmare’ and arebetter ‘managed’ onmixed wards, <strong>in</strong> others itawakened a serious<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> the provision ofnew, women‐focusedforms of care.F<strong>in</strong>ally, support for the development of better mental health service forwomen from the Department of <strong>Health</strong> 26 , 27 has helped to prioritise thesedevelopments, which also have important relevance for the crim<strong>in</strong>al2

justice system. A recent study of women on remand 28 found that almost60% met criteria for be<strong>in</strong>g diagnosed with a mental disorder, with 11%be<strong>in</strong>g acutely psychotic; though this was be<strong>in</strong>g poorly detected bystandard prison health screen<strong>in</strong>g procedures on entry to prison. This andother evidence 29 , 30 validates current efforts to divert women from thecrim<strong>in</strong>al justice system 31 .1.2 Background to women’s medium secure servicesWomen represent a small m<strong>in</strong>ority (about 15%) of the patient populationwith<strong>in</strong> secure mental health sett<strong>in</strong>gs, and yet they have been much morelikely than men to be deta<strong>in</strong>ed as civil patients, especially <strong>in</strong> high securehospitals. Until recently almost all medium and low secure services havebeen provided <strong>in</strong> mixed‐sex wards which were typically very maledom<strong>in</strong>ated,with many women f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g it difficult to cope <strong>in</strong> theseenvironments. Consequently, <strong>in</strong> the past women have tended to spiral upthe system to high secure care. Dur<strong>in</strong>g 1999, an assessment of all womenpatients <strong>in</strong> high secure hospitals showed that the majority did not requiresuch a high level of security but would be more appropriately cared for <strong>in</strong>conditions of lesser security or community sett<strong>in</strong>gs. (In the case of womenpatients <strong>in</strong> Broadmoor hospital, only 18% were assessed as requir<strong>in</strong>g HighSecure care; Source: HSPSCB 31/12/1999). This position was clearly atodds with the standards set out <strong>in</strong> the new National Service Framework(NSF) for mental health published that year. Standard Five of the NSFstates that service users requir<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>patient care should be cared for “<strong>in</strong>the least restrictive environment consistent with the need to protect themand the public” 32 .In 2000, the NHS Plan 33 set a target to transfer at least 400 patients out ofhigh secure hospitals with women deemed as a priority group. This targetwas reiterated <strong>in</strong> the Department of <strong>Health</strong> priorities outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>Improvement, expansion and reform the next three years priorities andplann<strong>in</strong>g framework 2003‐6, emphasis<strong>in</strong>g the need to ensure effective useof secure and forensic facilities. Subsequently the National Women’sMental <strong>Health</strong> (MH) Strategy of 2002 and the Implementation Guidance <strong>in</strong>2003 identified the need for <strong>in</strong>tegrated, dedicated women‐only securemental health services which provide gender‐specific services address<strong>in</strong>gthe specific mental health needs of women (e.g. histories of abuse, selfharm,and women as mothers). It <strong>in</strong>cludes a service specification andstandards for women’s secure services, pre‐empt<strong>in</strong>g the development of anational programme of reprovision of women’s secure services overseenand monitored by the National Oversight Group (NOG). The women’s MHstrategy consultation document highlighted the need for research todeterm<strong>in</strong>e whether there are advantages across a broad range ofoutcomes (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g service user def<strong>in</strong>ed outcomes), <strong>in</strong> deliver<strong>in</strong>g mentalhealth care <strong>in</strong> women only environments. The implementation guidanceidentifies the need for an <strong>in</strong>dependent evaluation of dedicated women’sDur<strong>in</strong>g 1999, anassessment of all womenpatients <strong>in</strong> high securehospitals showed that themajority did not requiresuch a high level ofsecurity but would bemore appropriately caredfor <strong>in</strong> conditions of lessersecurity or communitysett<strong>in</strong>gs.The women’s MH strategyconsultation documenthighlighted the need forresearch to determ<strong>in</strong>ewhether there areadvantages across a broadrange of outcomes(<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g service userdef<strong>in</strong>ed outcomes), <strong>in</strong>deliver<strong>in</strong>g mental healthcare <strong>in</strong> women onlyenvironments.3

secure services as they represent new models of care. The <strong>in</strong>dependentevaluation will contribute to their cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g development, enable shar<strong>in</strong>gof good practice, and provide measures of effectiveness of care with<strong>in</strong>these new and emerg<strong>in</strong>g service models for secure care for women.The evaluation will be of specific relevance to the Crim<strong>in</strong>al Justice System(CJS) priorities and <strong>in</strong> particular to the Jo<strong>in</strong>t DH and Prison ServiceStrategy 34 (2001) for develop<strong>in</strong>g mental health services <strong>in</strong> prisons. Thisidentifies performance <strong>in</strong>dicators, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the “quicker and moreeffective transfer arrangements for the most severely ill prisoners to NHSfacilities” and recommends <strong>in</strong>creased collaboration with NHS staff <strong>in</strong> themanagement of those who are seriously mentally ill. The Women’sOffend<strong>in</strong>g Reduction Programme (WORP) has a particular focus onmeet<strong>in</strong>g the needs of women with mental health problems. The WORPaction plan 35 <strong>in</strong>cludes action po<strong>in</strong>ts for improv<strong>in</strong>g availability of Mental<strong>Health</strong> Diversion Schemes, equipped specifically to deal with femaledefendants; equal access for women offenders to improved genderspecific mental health services <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g low and medium secure services;and <strong>in</strong> women’s prisons early assessment and identification of mentalhealth problems and need to transfer to NHS facilities at the earliest po<strong>in</strong>tof sentence.Women’s medium secure services form part of a national network ofsecure dedicated NHS services for women be<strong>in</strong>g developed as part of thereprovision of services to facilitate a programme of accelerated dischargeof patients from high secure care where women patients have beenidentified as a priority. The reprovision programme is underp<strong>in</strong>ned by thepr<strong>in</strong>ciples set out <strong>in</strong> Ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g Gender and Women’s Mental <strong>Health</strong>:Implementation Guide and <strong>in</strong> particular, the service specification forwomen’s secure services described <strong>in</strong> section 7.2 (p.38‐44).1.3 The chang<strong>in</strong>g landscape:Recent policy, research and service developmentsS<strong>in</strong>ce this evaluation commenced <strong>in</strong> 2006, there have been a number ofimportant policy and service developments that have impacted on theprovision of medium secure mental health services for women. Asummary update on policy and service developments follows.1.3.1 Women <strong>in</strong> the Crim<strong>in</strong>al Justice SystemThere have been several key policy developments <strong>in</strong> relation to women <strong>in</strong>the Crim<strong>in</strong>al Justice System. In response to <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> the female prisonpopulation the Home Office 36 launched its Women’s Offend<strong>in</strong>g ReductionProgramme <strong>in</strong> 2004, focus<strong>in</strong>g on improv<strong>in</strong>g community based services and<strong>in</strong>terventions that are tailored for women and support greater use ofcommunity rather than short term prison sentences. Despite this, <strong>in</strong> 2006the number of women <strong>in</strong> custody was still ris<strong>in</strong>g, with a 78% <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>4

the number of women remanded <strong>in</strong>to custody over the previous ten years(a rise from 4221 to 7498) 37 . Statistics also showed that most women werestill be<strong>in</strong>g given immediate custodial offences for non‐violent offences,with two‐thirds of women sentenced dur<strong>in</strong>g 2006 given terms of sixmonths or less 38 . The Department of <strong>Health</strong>’s 39 “Women at Risk” reporton the mental health of women <strong>in</strong> contact with the crim<strong>in</strong>al justicesystem, published <strong>in</strong> 2006, recommended the development of better datacollection regard<strong>in</strong>g the needs of this vulnerable group of women to<strong>in</strong>form the plann<strong>in</strong>g and development of services to meet their needswhen transferr<strong>in</strong>g from or leav<strong>in</strong>g prison, as well as the development ofcourt diversion schemes and prison <strong>in</strong>‐reach services for women offenderswith mental health needs. Also <strong>in</strong> 2006, and follow<strong>in</strong>g the deaths of sixwomen at Styal prison, Baroness Jean Corston 40 was commissioned by theHome Office to undertake a review of Women with ParticularVulnerabilities <strong>in</strong> the Crim<strong>in</strong>al Justice System. Her report was published <strong>in</strong>March 2007 and the Government’s response 41 , <strong>in</strong> December 2007,accepted 40 of her 43 recommendations. The Government then producedits first National Service Framework for Female <strong>Offender</strong>s 42 <strong>in</strong> May 2008.However, one of Corston’s key recommendations, stat<strong>in</strong>g that “theGovernment should announce with<strong>in</strong> six months a clear strategy to replaceexist<strong>in</strong>g women’s prisons with geographically dispersed, small, multifunctionalcustodial centres with<strong>in</strong> 10 years”, was not fully taken on boarddespite widespread support for this proposal (a public op<strong>in</strong>ion pollcommissioned by Smart Justice 43 showed 86% of the public questionedsupported the proposal). Follow<strong>in</strong>g a pilot study an announcement wasmade that, whilst the Government accepted the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples upon whichCorston recommended the development of small custodial units forwomen, it had identified significant issues suggest<strong>in</strong>g standalone units ofthe size recommended (20 to 30 women) were neither feasible nordesirable. Implementation of the other recommendations is be<strong>in</strong>gregularly reported on, with a M<strong>in</strong>isterial statement <strong>in</strong> December 2008sett<strong>in</strong>g out progress <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g additional resources to divert vulnerablewomen from custody, development of a cross‐departmental Crim<strong>in</strong>alJustice Women’s Strategy Unit, the publication by NOMS of an <strong>Offender</strong>Management Guide to Work<strong>in</strong>g with Women 44 and Gender SpecificStandards for Women’s Prisons 45 . A review by Lord Bradley <strong>in</strong>to thediversion of offenders with mental health needs or learn<strong>in</strong>g disabilities toappropriate mental health sett<strong>in</strong>gs is due to report to the government <strong>in</strong>early 2009. Its recommendations are due to be taken forward <strong>in</strong> the<strong>Offender</strong> <strong>Health</strong> and Social Care Strategy, currently be<strong>in</strong>g developed bythe Department of <strong>Health</strong> to be published <strong>in</strong> the summer of 2009.Serious concerns regard<strong>in</strong>g the welfare of women prisoners and othervulnerable offenders (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those with mental health needs), and the<strong>in</strong>adequateness of the response to their plight, cont<strong>in</strong>ue to be raisedthrough various <strong>in</strong>dependent reports. A report by INQUEST 46 published <strong>in</strong>2008 exam<strong>in</strong>ed women’s deaths <strong>in</strong> custody between 1990 and 2007. It5

evealed a “shameful and deplorable” picture of preventable tragedy, withmany of the women dy<strong>in</strong>g be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>appropriately placed <strong>in</strong> custody despiteclear evidence of their requir<strong>in</strong>g care <strong>in</strong> mental health sett<strong>in</strong>gs, and issuesraised from <strong>in</strong>vestigations <strong>in</strong>to deaths <strong>in</strong> 1990 still be<strong>in</strong>g just as prevalent17 years on. A report by the All‐Party Parliamentary Group on Prison<strong>Health</strong> on the Mental <strong>Health</strong> Problem <strong>in</strong> UK HM Prisons 47 described adysfunctional system and recommended a fundamental shift <strong>in</strong> th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g ateach stage of the <strong>in</strong>dividual’s pathway through mental health and crim<strong>in</strong>aljustice services. Dur<strong>in</strong>g 2008 two reports by the Sa<strong>in</strong>sbury Centre forMental <strong>Health</strong> 48 , 49 and one from Policy Exchange 50 all highlightedproblems with <strong>in</strong>adequate fund<strong>in</strong>g and resources for prison mental healthcare <strong>in</strong> England. These <strong>in</strong>cluded a lack of multidiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary expertise <strong>in</strong>prison In‐Reach teams, and an average of just 11% of the prisonhealthcare budget be<strong>in</strong>g spent on mental health care despite the muchhigher prevalence of mental disorder there than <strong>in</strong> the community where15% of health fund<strong>in</strong>g goes towards fund<strong>in</strong>g mental health services. Inaddition, some NHS regions spend significantly less than others, lead<strong>in</strong>g toa post‐code lottery of mental healthcare <strong>in</strong> prisons.1.3.2 Gender and Women’s Mental <strong>Health</strong>Follow<strong>in</strong>g the publication by the Department of <strong>Health</strong> (DH) of its nationalwomen’s mental health strategy 51 , NIMHE (National Institute for Mental<strong>Health</strong> <strong>in</strong> England) established its national programme on gender equalityand women’s mental health <strong>in</strong> order to support the ImplementationGuidance: Ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g Gender and Women’s Mental <strong>Health</strong> 52 . Thisaimed to ensure the development of mental health systems able to deliverresponsive and gender sensitive services to meet the specific and diverseneeds of women. The work of the programme s<strong>in</strong>ce 2006 has focused onimprov<strong>in</strong>g women’s <strong>safe</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>patient sett<strong>in</strong>gs as well as develop<strong>in</strong>gwomen only and gender sensitive day services 53 , improv<strong>in</strong>g choice andaccess to psychological therapies, and develop<strong>in</strong>g better per<strong>in</strong>atal mentalhealth services. Informed Gender Practice: Mental <strong>Health</strong> Acute Care thatworks for women 54 was published <strong>in</strong> July 2008 to encourage practitionerswork<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> acute mental health sett<strong>in</strong>gs to develop gender sensitivepractice with a focus on women’s physical and psychological <strong>safe</strong>ty. Inaddition, follow<strong>in</strong>g a two year pilot project, the Mental <strong>Health</strong> TrustCollaboration Project worked with 16 Mental <strong>Health</strong> Trusts across Englandto improve the care and support provided to service users who havesurvived sexual and other abuse, follow<strong>in</strong>g which a national policy waslaunched <strong>in</strong> June 2008 55 . This <strong>in</strong>cluded the provision of sexual abusetra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to all Mental <strong>Health</strong> Trusts <strong>in</strong> England from November 2008 andthe publication of supportive practice guidance <strong>in</strong> April 2009. Deliver<strong>in</strong>gequality for women (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g race equality for women from BMEcommunities) has also been a recent priority of the Gender and Women’sMental <strong>Health</strong> national programme. To help prepare mental healthproviders for the implementation of equality legislation, it producedguidel<strong>in</strong>es for Mental <strong>Health</strong> Trusts 56 about the implementation of thePublic Sector Gender Equality Duty which came <strong>in</strong>to force <strong>in</strong> April 2007.6

1.3.3 Safeguard<strong>in</strong>g patients, <strong>safe</strong>ty and s<strong>in</strong>gle‐sex provisionIn July 2006 the National Patient Safety Agency 57 released its secondPatient Safety Observatory Report stat<strong>in</strong>g that 122 ‘sexual <strong>safe</strong>ty’ <strong>in</strong>cidents<strong>in</strong> mental health <strong>in</strong>patient wards had been reported to them betweenNovember 2003 and September 2005. These <strong>in</strong>cluded 19 alleged rapes, 13cases of exposure, 18 cases of unwanted sexual advances and 26 cases of“<strong>in</strong>vasive touch<strong>in</strong>g”. Follow<strong>in</strong>g publication of the NPSA report, CommunityCare magaz<strong>in</strong>e used the Freedom of <strong>in</strong>formation Act to request<strong>in</strong>formation from Mental <strong>Health</strong> Trusts about sexual <strong>safe</strong>ty <strong>in</strong>cidents 58 .The 44 Trusts respond<strong>in</strong>g (out of the 70 approached) reported over 300<strong>in</strong>cidents dur<strong>in</strong>g the three years between 2003 and 2006, of which 224<strong>in</strong>volved assaults on patients by other patients. The follow<strong>in</strong>g year theGovernment published new guidance on “Safeguard<strong>in</strong>g Patients” 59 as itsresponse to the recommendations of the Shipman, Ayl<strong>in</strong>g, Neale andKerr/Haslam Inquiries, which covered boundary transgression issues <strong>in</strong>mental health services. This reviews the recommendations <strong>in</strong> theKerr/Haslam and Ayl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>quiries about the failure of health organisationsto take seriously allegations of sexual assault on female patients.Dent 60 reported that sexual <strong>safe</strong>ty <strong>in</strong>cidents are treated as part of mentalhealth <strong>in</strong>patient <strong>life</strong> with disbelief built <strong>in</strong>to the system (as there is anattitude that patients cannot be believed because they are ill) and the lackof adequate tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and experienced staff exacerbate poor levels of<strong>safe</strong>ty on mixed <strong>in</strong>patient wards. In 2007, the Royal College ofPsychiatrists 61 produced guidel<strong>in</strong>es on sexual boundary issues <strong>in</strong>psychiatric sett<strong>in</strong>gs which <strong>in</strong>cluded particular issues for secure units andthe <strong>safe</strong>ty of women <strong>in</strong> these sett<strong>in</strong>gs, stat<strong>in</strong>g that their sexualvulnerability must be recognised and addressed by the multidiscipl<strong>in</strong>aryteam <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual care plans. The Mental <strong>Health</strong> Act Commission 62 <strong>in</strong>their Biennial Report for their report<strong>in</strong>g period 2005‐7 also raised seriousconcerns regard<strong>in</strong>g women’s sexual <strong>safe</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>patient sett<strong>in</strong>gs andexpressed disappo<strong>in</strong>tment at the lack of progress <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g theGovernment’s policy on the provision of s<strong>in</strong>gle sex accommodation <strong>in</strong> allhospital wards.In the debate about the implementation by the Government of the LabourParty Manifesto pledge to eradicate mixed sex wards, the Shadow <strong>Health</strong>Secretary released figures from a Freedom of Information Survey <strong>in</strong>January 2009 63 which revealed that 2% of Mental <strong>Health</strong> Trusts were stillus<strong>in</strong>g “night<strong>in</strong>gale wards” (large, dormitory‐style rooms) to look after menand women; 8% still used curta<strong>in</strong>s and 11% used partitions rather thansolid walls to segregate patients <strong>in</strong> some areas; as many as 29% failed toprovide segregated wash<strong>in</strong>g facilities for patients <strong>in</strong> some areas; and 24%did not provide segregated toilet facilities on all wards. The 55 Mental<strong>Health</strong> Trusts respond<strong>in</strong>g to the survey had received 135 compla<strong>in</strong>ts frompatients about privacy and dignity issues <strong>in</strong> hospital dur<strong>in</strong>g the year toSeptember 2008. In response, the Government has announced its clearcommitment to eradicate all mixed‐sex hospital accommodation (<strong>in</strong> all7

cl<strong>in</strong>ical areas apart from Accident and Emergency), and is publish<strong>in</strong>gfurther guidance on its def<strong>in</strong>ition of s<strong>in</strong>gle sex accommodation as well assett<strong>in</strong>g up a £100m Privacy and Dignity Fund to help trust makeimprovements to hospital accommodation over the next six months. In2010/11 it will <strong>in</strong>troduce f<strong>in</strong>es for NHS Trusts not comply<strong>in</strong>g with therequirement to provide <strong>in</strong>patient care <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle sex accommodation 64 .1.3.4 NHS Commission<strong>in</strong>g arrangements and M<strong>in</strong>imum StandardsIn March 2006 the Government White Paper “Our <strong>Health</strong>, Our Care, OurSay” 65 outl<strong>in</strong>ed plans for major structural changes and a ‘changemanagement’ programme aimed at develop<strong>in</strong>g “World Class”commission<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the NHS. Follow<strong>in</strong>g this, <strong>in</strong> July 2006 the number ofStrategic <strong>Health</strong> Authorities (SHAs) which are responsible for co‐ord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>gand manag<strong>in</strong>g Primary Care Trusts was reduced from 28 to just 10 with theaim of strengthen<strong>in</strong>g commission<strong>in</strong>g capacity. The Department of <strong>Health</strong>at the same time published “<strong>Health</strong> Reform <strong>in</strong> England: update andCommission<strong>in</strong>g Framework” 66 which <strong>in</strong>troduced the regionalisation ofcommission<strong>in</strong>g of low and medium secure mental health services. FromApril 2007 these services have been commissioned on behalf of PrimaryCare Trusts by Specialised Commission<strong>in</strong>g Groups set up by the ten newlyformed Strategic <strong>Health</strong> Authorities, with PCT f<strong>in</strong>ancial allocations be<strong>in</strong>gtop‐sliced to fund this specialised commission<strong>in</strong>g. Other developmentsaffect<strong>in</strong>g the commission<strong>in</strong>g of secure mental health services <strong>in</strong>clude the<strong>in</strong>troduction of a new standard mental health contract <strong>in</strong> England whichwill place <strong>in</strong>dependent sector providers on a more level play<strong>in</strong>g field with<strong>in</strong>‐house NHS providers. These new contracts are due to be <strong>in</strong>troduced ona voluntary basis <strong>in</strong> April 2009 and compulsorily from April 2010. They willbe subject to regular reviews, with commissioners expected to review alist of quality <strong>in</strong>dicators as part of contract monitor<strong>in</strong>g. These quality<strong>in</strong>dicators, for medium secure units, are likely to overlap with NationalM<strong>in</strong>imum Standards 67 .Standards for Medium Secure Services that were developed by the RoyalCollege of Psychiatry Quality <strong>Network</strong> for Forensic Services have beenadopted by the Department of <strong>Health</strong> as National M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards foradult medium secure services <strong>in</strong> England with the Department publish<strong>in</strong>gBest practice Guidance based on these standards <strong>in</strong> July 2007. 68 TheRCPsych Quality <strong>Network</strong> has subsequently developed an additional set ofStandards and Criteria to specifically address the needs of Women <strong>in</strong>Medium Secure Care 69 . In 2009, only n<strong>in</strong>e women’s medium secureservices had become members of the Quality <strong>Network</strong> although jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gwill become a requirement <strong>in</strong> the future. The add‐on standards forwomen’s services have yet to be adopted by the Department of <strong>Health</strong> asrequired quality standards for the Specialised Commission<strong>in</strong>g Groups to<strong>in</strong>corporate when develop<strong>in</strong>g their service specifications for women’ssecure services.8

1.3.5 Service developments for women requir<strong>in</strong>g medium secure careConcurrent with the evaluation process there has been a number of majorservice developments <strong>in</strong> secure mental health provision for women,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the closure of Broadmoor Hospital’s Women’s Service dur<strong>in</strong>g2007. This leaves just one National High Secure Service for women atRampton Hospital, based <strong>in</strong> a new purpose‐built facility which opened <strong>in</strong>December 2006 provid<strong>in</strong>g 50 beds across four wards <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g one forwomen with learn<strong>in</strong>g disabilities.Dur<strong>in</strong>g 2007 and 2008, three Women’s Enhanced Medium Secure Services(WEMSS) have been opened, one each <strong>in</strong> the North West, East Midlandsand London regions. Additionally, four High Support CommunityResidential projects are be<strong>in</strong>g developed to enable the rehabilitation andcommunity resettlement of women leav<strong>in</strong>g secure mental health services.Both of these new developments are pilot schemes funded by theDepartment of <strong>Health</strong> as part of the strategy for the Reprovision ofWomen’s Secure Services, and are aimed at improv<strong>in</strong>g care pathways forwomen <strong>in</strong> secure services. As well as these nationally commissioneddevelopments a significant number of additional medium secure beds <strong>in</strong>both the NHS and Independent sector were opened dur<strong>in</strong>g this period.This reorganisation of women’s secure services has seen the rapidexpansion of NHS women‐only units with many NHS Commissionersaim<strong>in</strong>g to return women placed <strong>in</strong> private out of area treatment service to<strong>in</strong>‐house NHS provision <strong>in</strong> their home area 70 , although private sectorprovision also cont<strong>in</strong>ues to expand with further <strong>in</strong>dependent sectorunits/beds open<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g 2007‐08. In 2000, a survey of all mediumsecure units 71 found just 14 NHS medium secure beds for women <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>glesex wards and 79 medium secure beds <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle sex units <strong>in</strong> the<strong>in</strong>dependent sector. At that time most medium secure beds for womenwere provided with<strong>in</strong> mixed sex ward accommodation, and these provideda further 249 women’s beds, mak<strong>in</strong>g the total medium secure bedcapacity for women to 343. However, by January 2009 a follow‐uptelephone survey to all providers of medium secure care for women <strong>in</strong>s<strong>in</strong>gle gender units (see section 2) found the number of medium securebeds for women <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle sex sett<strong>in</strong>gs had <strong>in</strong>creased to 543 across bothsectors (NHS and Independent), with just a small number of women’s bedsstill provided <strong>in</strong> mixed sex wards, although these are now very much theexception rather than the rule.1.4 The evaluation approachWith<strong>in</strong> the context of the literature, policy and practice and <strong>in</strong> order toachieve its aim, the evaluation had six objectives as follows:• to exam<strong>in</strong>e the extent to which and how these services are deliver<strong>in</strong>gcare, support and treatment which meet the specific needs of women• to exam<strong>in</strong>e the extent to which and how these services are able to9